User login

Endocrine Mucin-Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma and Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma: A Case Series

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

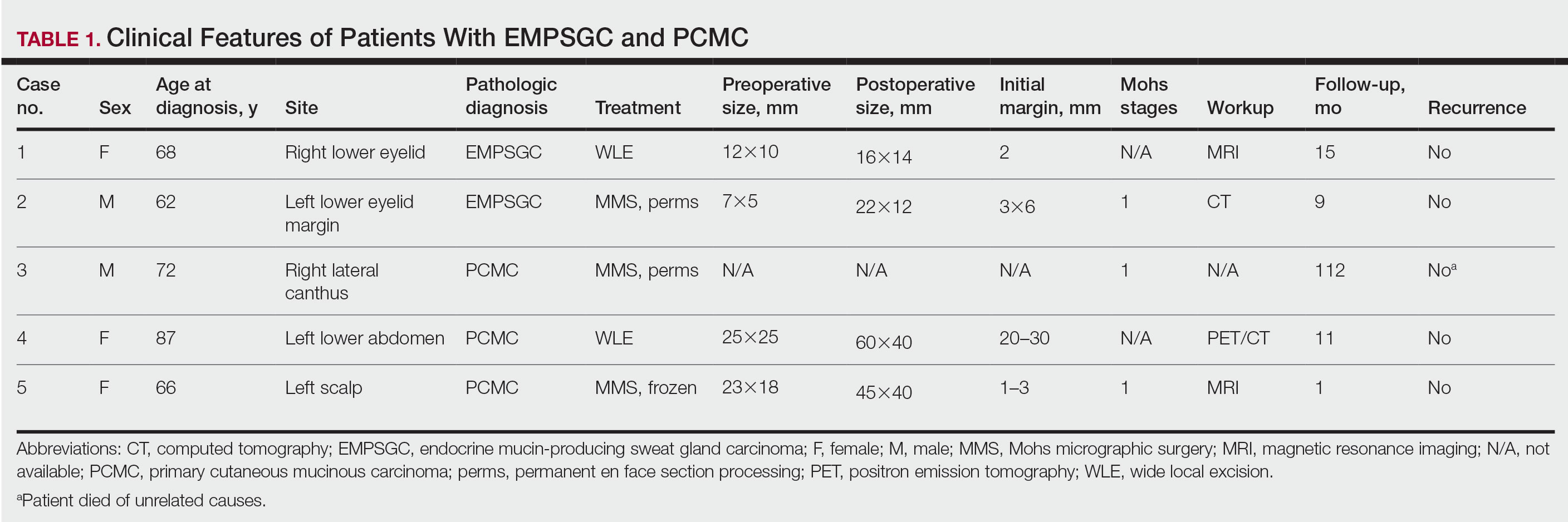

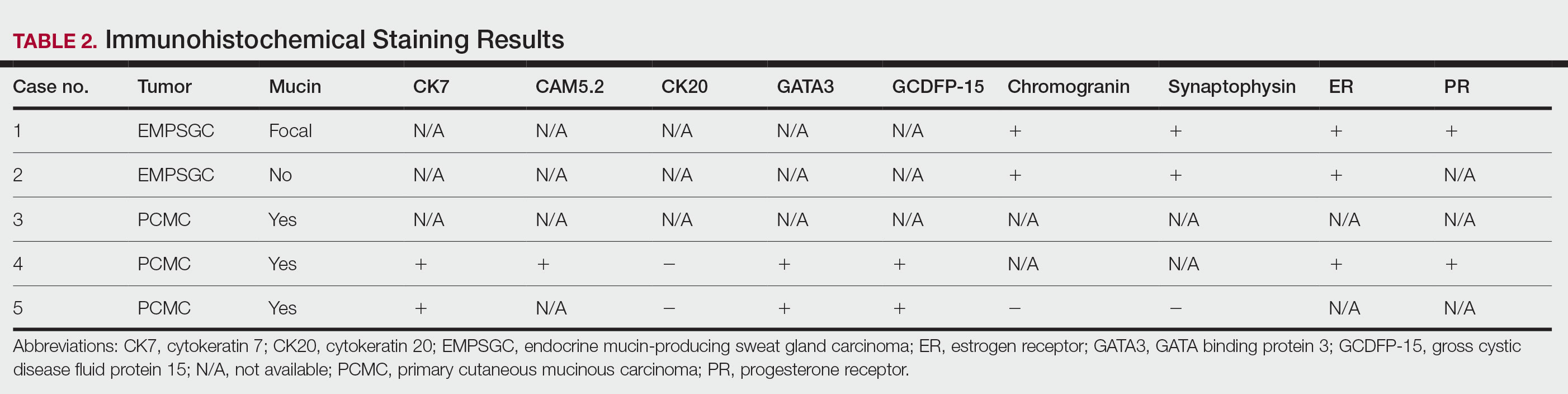

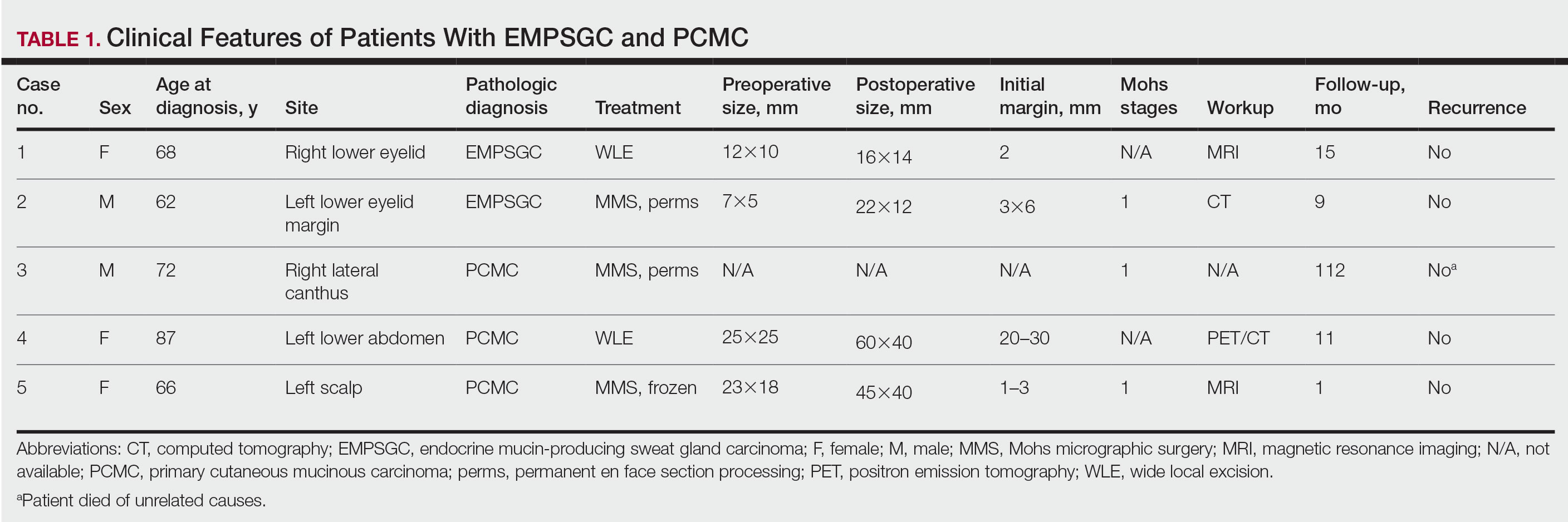

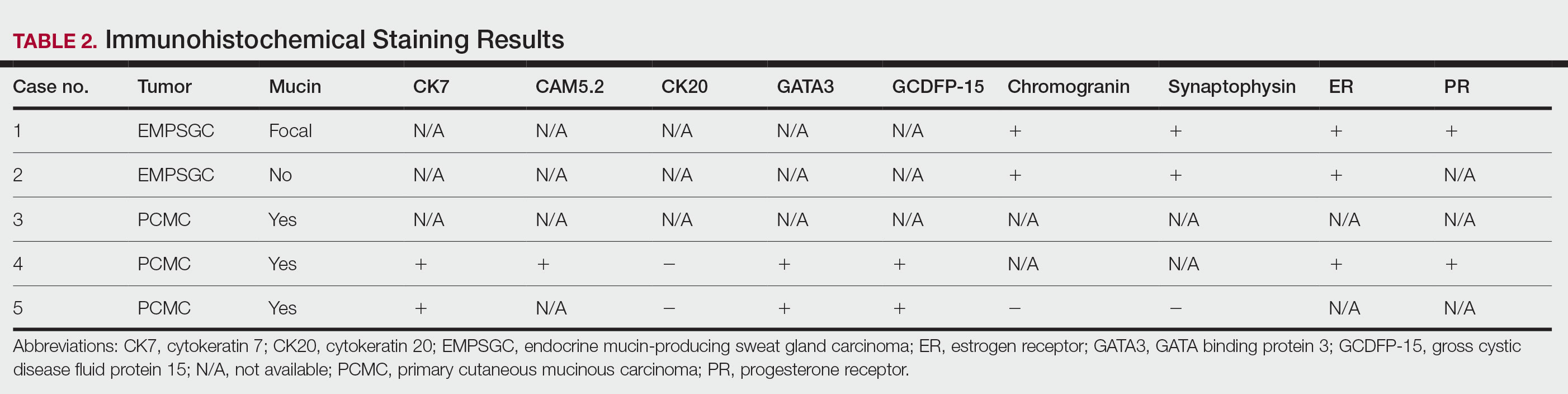

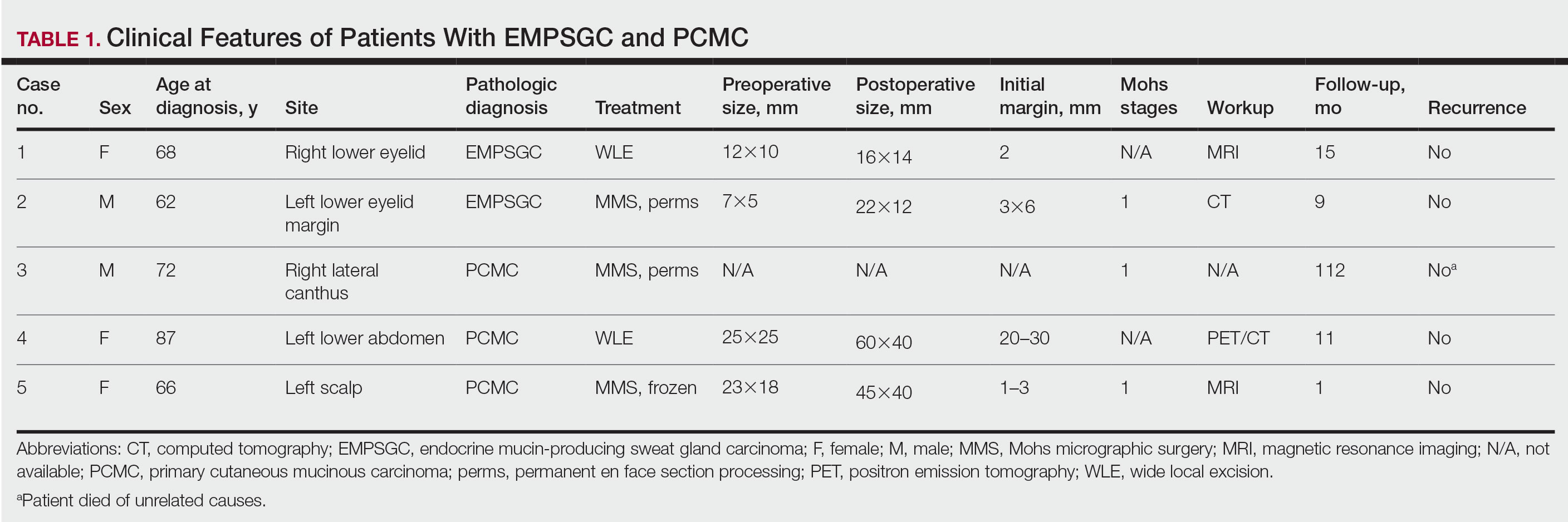

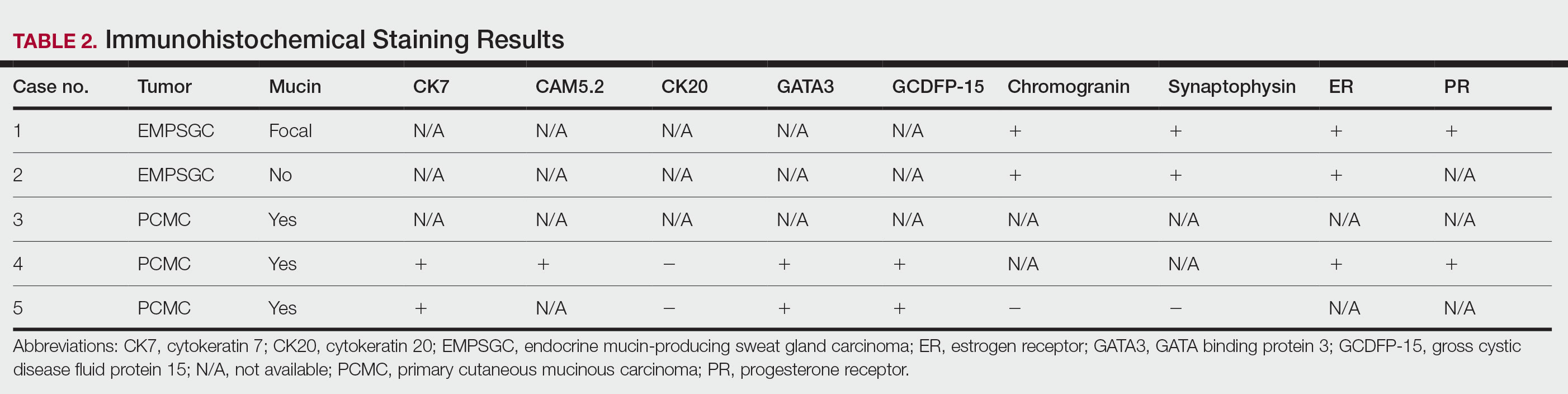

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

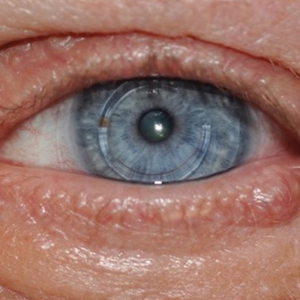

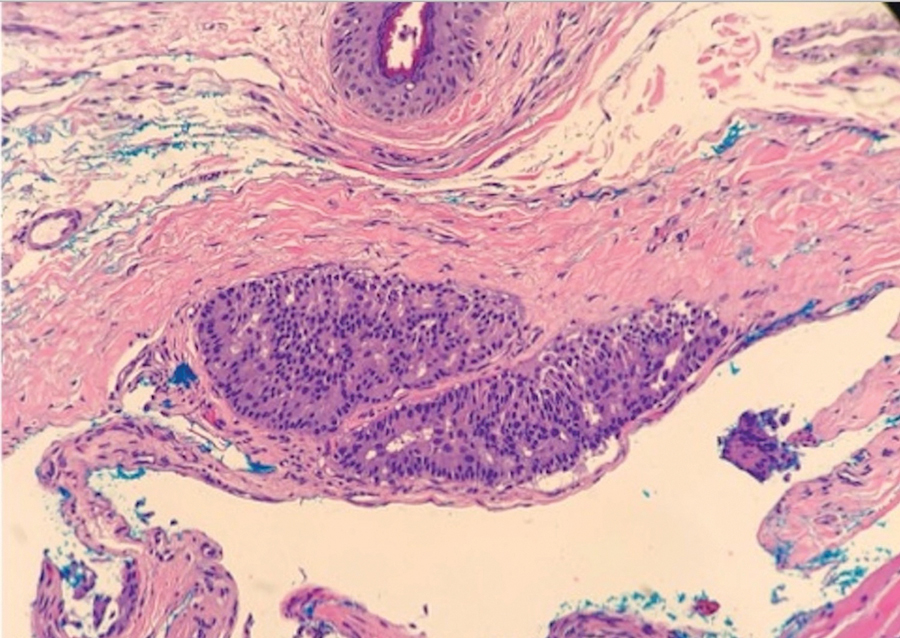

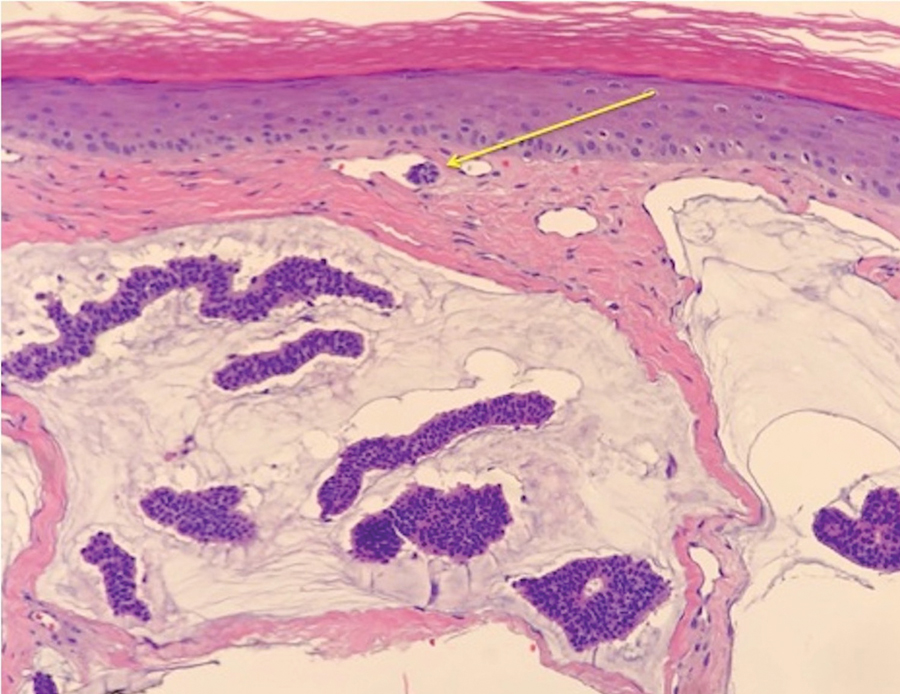

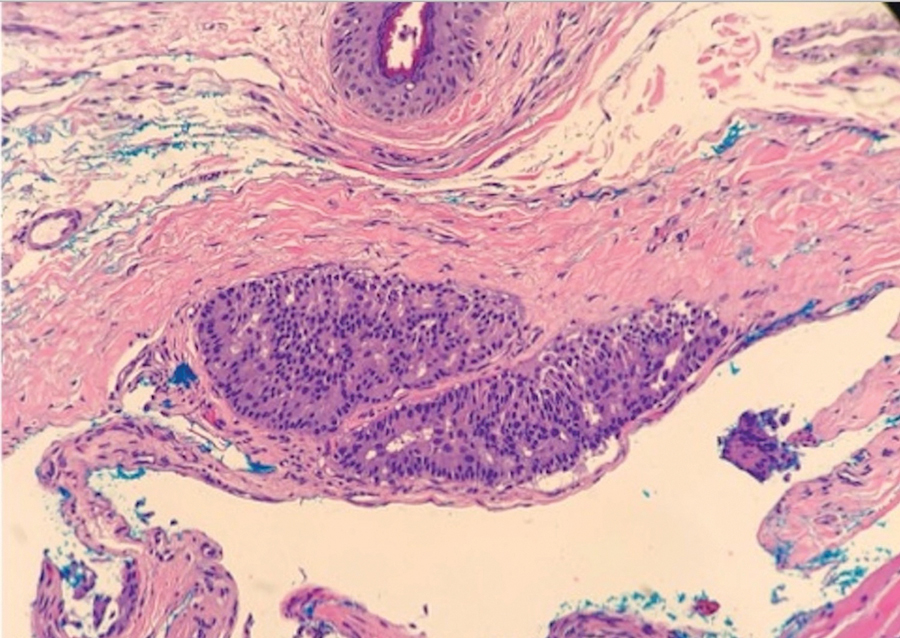

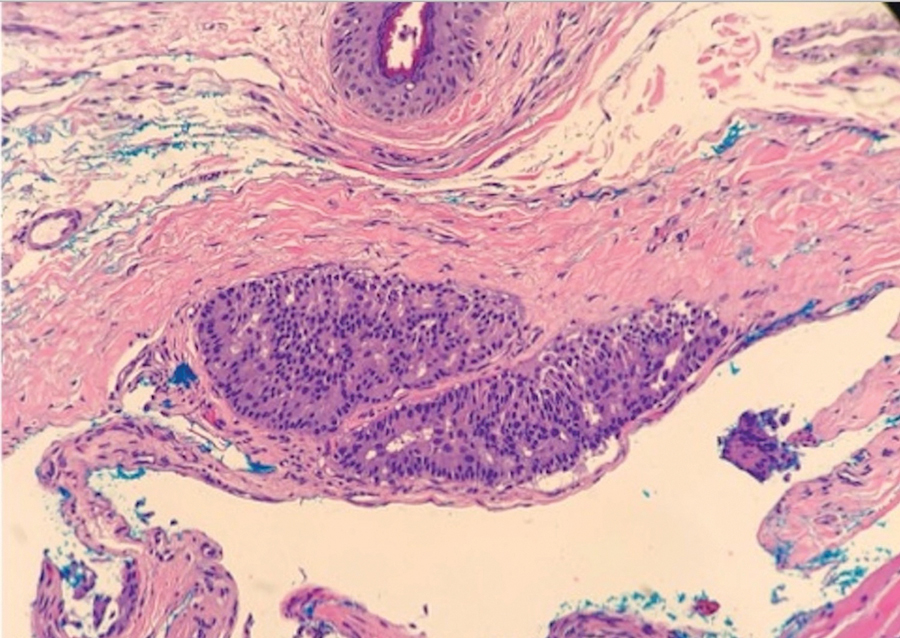

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

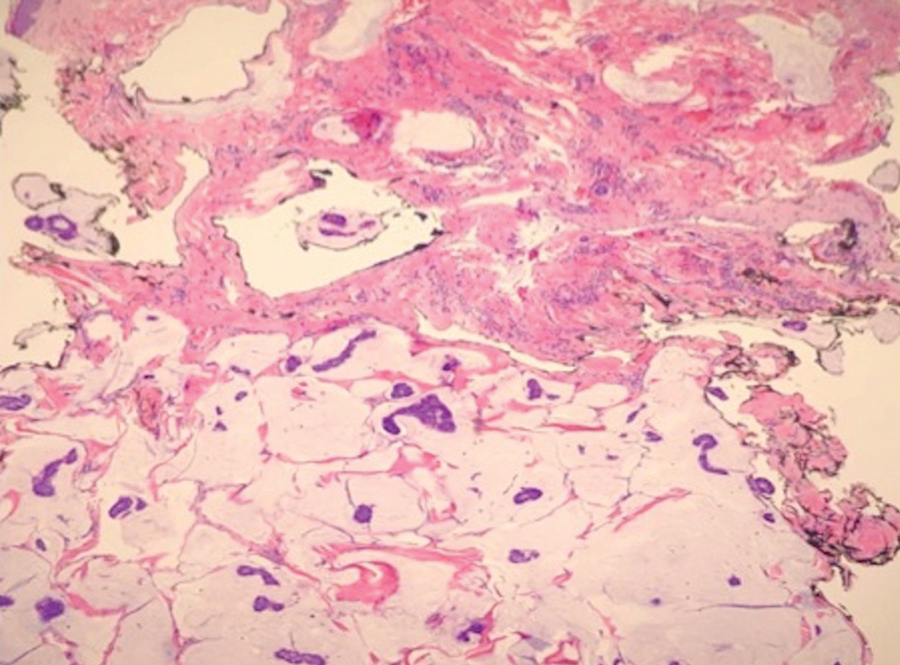

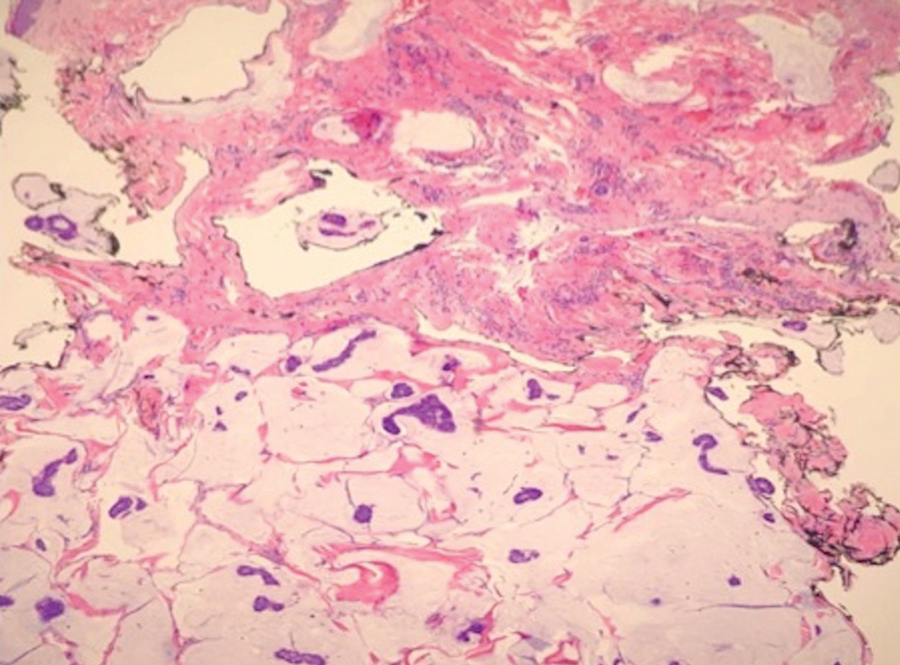

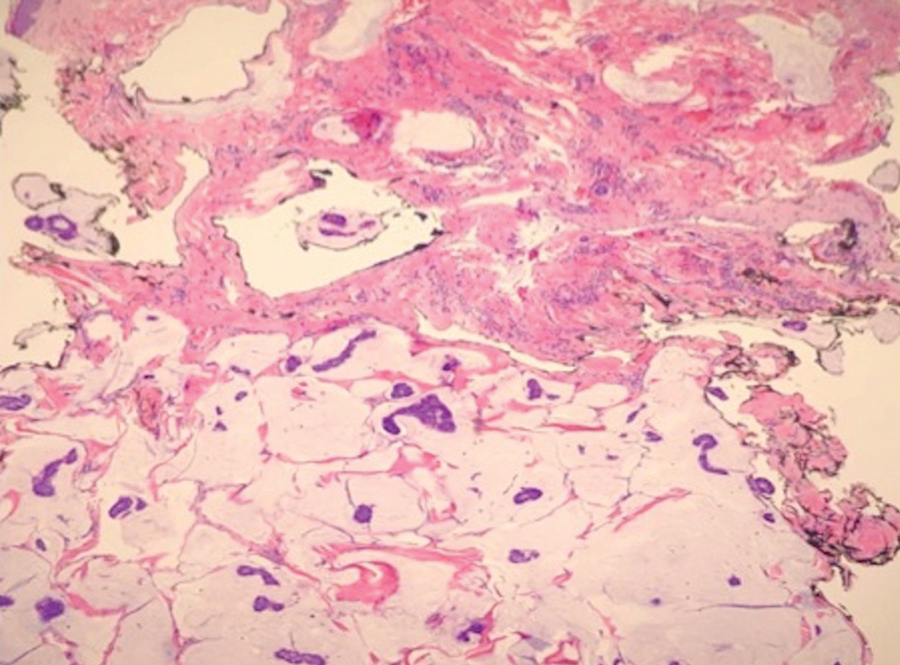

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

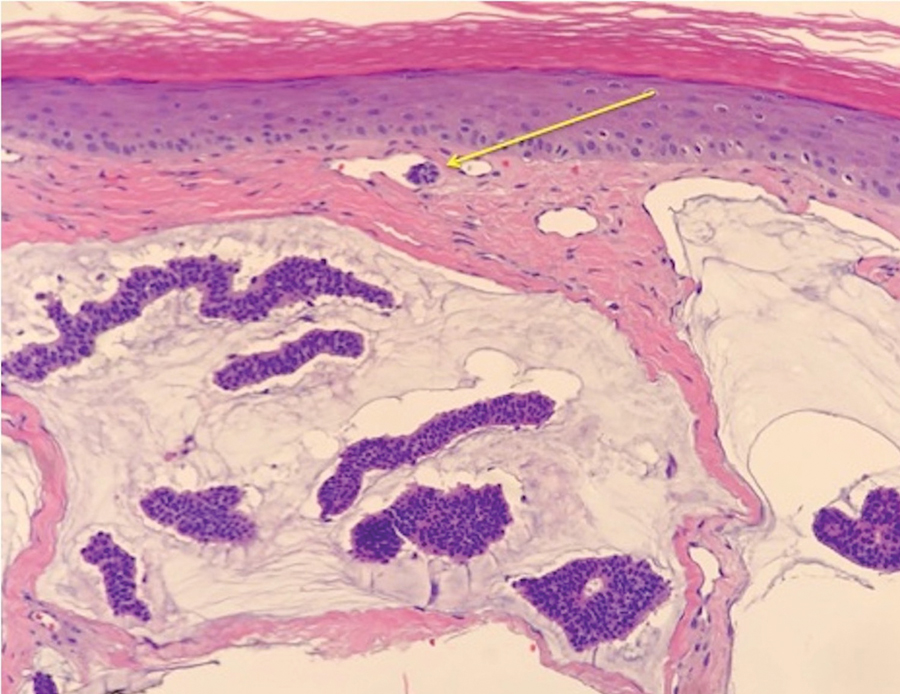

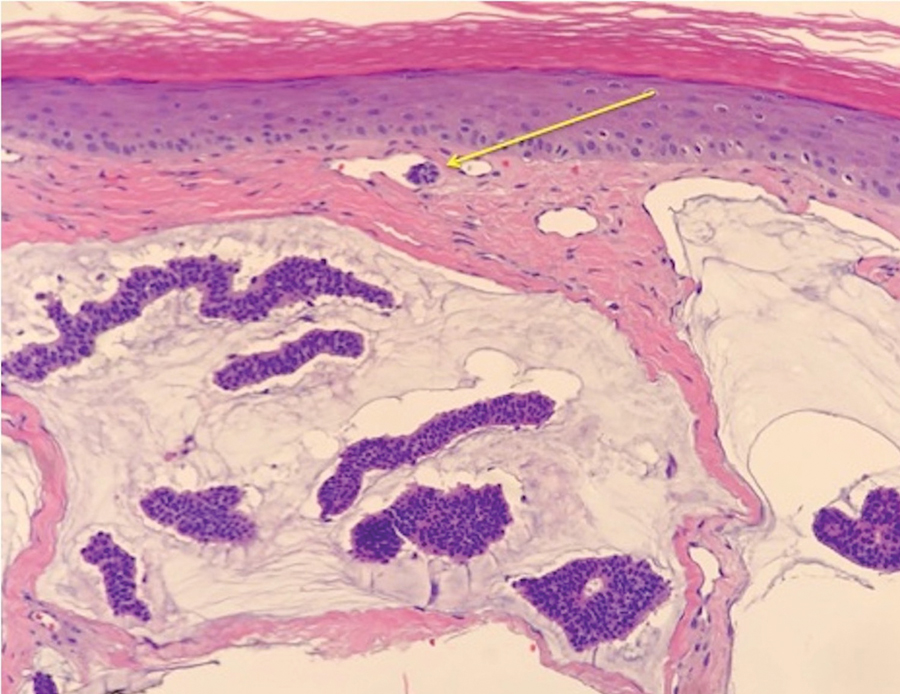

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

Practice Points

- Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma are rare low-grade neoplasms thought to arise from apocrine glands that are morphologically and immunohistochemically analogous to ductal carcinoma in situ and mucinous carcinoma of the breast, respectively.

- Management involves a metastatic workup and either wide local excision with margins greater than 5 mm or Mohs micrographic surgery in anatomically sensitive areas.

Pruritic rash on chest and back

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; daniel.l.croom.mil@mail.mil

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; daniel.l.croom.mil@mail.mil

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; daniel.l.croom.mil@mail.mil

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.