User login

The Use of Immuno-Oncology Treatments in the VA (FULL)

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference discussion recorded in April 2018.

Suman Kambhampati, MD. Immuno-oncology is a paradigm-shifting treatment approach. It is an easy-to-understand term for both providers and for patients. The underlying principle is that the body’s own immune system is used or stimulated to fight cancer, and there are drugs that clearly have shown huge promise for this, not only in oncology, but also for other diseases. Time will tell whether that really pans out or not, but to begin with, the emphasis has been inoncology, and therefore, the term immunooncology is fitting.

Dr. Kaster. It was encouraging at first, especially when ipilimumab came out, to see the effects on patients with melanoma. Then the KEYNOTE-024 trial came out, and we were able to jump in anduse monoclonal antibodies directed against programmed death 1 (PD-1) in the first line, which is when things got exciting.1 We have a smaller populationin Boise, so PD-1s in lung cancer have had the biggest impact on our patients so far.

Ellen Nason, RN, MSN. Patients are open to immunotherapies.They’re excited about it. And as the other panelists have said, you can start broadly, as the body fights the cancer on its own, to providing more specific details as a patient wants more information. Immuno-oncology is definitely accepted by patients, and they’re very excited about it, especially with all the news about new therapies.

Dr. Kambhampati. For the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) population, lung cancer has seen significant impact, and now it’s translating into other diseases through more research, trials, and better understanding about how these drugs are used and work.

The paradigm is shifting toward offering these drugs not only in metastatic cancers, but also in the surgically resectable tumors. The 2018 American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting, just concluded. At the meeting several abstracts reported instances where immunooncology drugs are being introduced in the early phases of lung cancer and showing outstanding results. It’s very much possible that we’re going to see less use of traditional chemotherapy in the near future.

Ms. Nason. I primarily work with solid tumors,and the majority of the population I work with have lung cancer. So we’re excited about some of the results that we’ve seen and the lower toxicity involved. Recently, we’ve begun using durvalumab with patients with stage III disease. We have about 5 people now that are using it as a maintenance or consolidative treatment vs just using it for patients with stage IV disease. Hopefully, we’ll see some of the same results describedin the paper published on it.2

Dr. Kaster. Yes, we are incorporating these new changes into care as they're coming out. As Ms. Nason mentioned, we're already using immunotherapies in earlier settings, and we are seeing as much research that could be translated into care soon, like combining immunotherapies

in first-line settings, as we see in the Checkmate-227 study with nivolumab and ipilimumab.3,4 The landscape is going to change dramatically in the next couple of years.

Accessing Testing For First-Line Treatments

Dr. Lynch. There has been an ongoing discussionin the literature on accessing appropriate testing—delays in testing can result in patients who are not able to access the best targeted drugs on a first-line basis. The drug companiesand the VA have become highly sensitized to ensuring that veterans are accessing the appropriate testing. We are expanding the capability of VA labs to do that testing.

Ms. Nason. I want to put in a plug for the VA Precision Oncology Program (POP). It’s about 2 years into its existence, and Neil Spector, MD, is the director. The POP pays for sequencing the tumor samples.

A new sequencing contract will go into effect October 2018 and will include sequencing for hematologic malignancies in addition to the current testing of solid tumors. Patients from New York who have been unable to receive testing through the current vendors used by POP, will be included in the new contract. It is important to note that POP is working closely with the National Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM) to develop a policy for approving off-label use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies based on sequenced data collected on patients tested through POP.

In addition, the leadership of POP is working to leverage the molecular testing results conducted through POP to improve veterans' access to clinical trials, both inside and outside the VA. Within the VA people can access information at tinyurl.com/precisiononcology. There is no reason why any eligible patient with cancer in the VA health care system should not have their tumor tissue sequenced through POP, particularly once the new contract goes into effect.

Dr. Lynch. Fortunately, the cost of next-generation sequencing has come down so much that most VA contracted reference laboratories offer next-generation sequencing, including LabCorp (Burlington,NC), Quest Diagnostics (Secaucus, NJ), Fulgent (Temple City, CA), and academic partners such as Oregon Health Sciences University and University of Washington.

Ms. Nason. At the Durham VAMC, sometimes a lack of tissue has been a barrier, but we now have the ability to send blood (liquid biopsy) for next-generation sequencing. Hopefully that will open up options for veterans with inadequate tissue. Importantly, all VA facilities can request liquid biopsiesthrough POP.

Dr. Lynch. That’s an important point. There have been huge advances in liquid biopsy testing.The VA Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS) was in talks with Genomic Health (Redwood City, CA) to do a study as part of clinical operations to look at the concordance between the liquid biopsy testing and the precision oncology data. But Genomic Health eventually abandoned its liquid biopsy testing. Currently, the VA is only reimbursing or encouraging liquid biopsy if the tissue is not available or if the veteran has too high a level of comorbidities to undergo tissue biopsy. The main point for the discussion today is that access to testing is a key component of access to all of these advanced drugs.

Dr. Kambhampati. The precision medicine piece will be a game changer—no question about that. Liquid biopsy is very timely. Many patients have difficulty getting rebiopsied, so liquid biopsy is definitely a big, big step forward.

Still, there has not been consistency across the VA as there should be. Perhaps there are a few select centers, including our site in Kansas City, where access to precision medicine is readily available and liquid biopsies are available. We use the PlasmaSELECT test from Personal Genome Diagnostics (Baltimore, MD). We have just added Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA) also in hematology. Access to mutational profilingis absolutely a must for precision medicine.

All that being said, the unique issue with immuno-oncology is that it pretty much transcends the mutational profile and perhaps has leveled the playing field, irrespective of the tumor mutation profile or burden. In some solid tumors these immuno-oncology drugs have been shown to work across tumor types and across different mutation types. And there is a hint now in the recent data presented at AACR and in the New England Journalof Medicine showing that the tumor mutational burden is a predictor of pathologic response to at least PD-1 blockade in the resectable stages of lung cancer.1,3 To me, that’s a very important piece of data because that’s something that can be tested and can have a prognostic impact in immuno-oncology, particularly in the early stages of lung cancer and is further proof of the broad value of immunotherapics in targeting tumors irrespective of the precise tumor targets.

Dr. Kaster. Yes, it’s nice to see other options like tumor mutational burden and Lung Immune Prognostic Index being studied.5 It would be nice if we could rely a little more on these, and not PD-L1, which as we all know is a variable and an unreliable target.

Dr. Kambhampati. I agree.

Rural Challenges In A Veterans Population

Dr. Lynch. Providing high-quality cancer care to rural veterans care can be a challenge but it is a VA priority. The VA National Genomic Medicine Services offers better access for rural veterans to germline genetic testing than any other healthcare system in the country. In terms of access to somatic testing and next-generation sequencing, we are working toward providing the same level of cancer care as patients would receive at National Cancer Institute (NCI) cancer centers. The VA oncology leadership has done teleconsults and virtual tumor boards, but for some rural VAMCs, fellowsare leading the clinical care. As we expand use of oral agents for oncology treatment, it will be easier to ensure that rural veterans receive the same standard of care for POP that veterans being cared for at VASLCHCS, Kansas City VAMC, or Durham VAMC get.

Dr. Kambhampati. The Kansas City VAMC in its catchment area includes underserved areas, such as Topeka and Leavenworth, Kansas. What we’ve been able to do here is something that’s unique—Kansas City VAMC is the only standalone VA in the country to be recognized as a primary SWOG (Southwestern Oncology Group) institution, which provides access to many trials, such as the Lung-MAP trial and others. And that has allowed us to use the full expanse of precision medicine without financial barriers. The research has helped us improve the standard of

care for patients across VISN 15.

Dr. Lynch. In precision oncology, the chief of pathology is an important figure in access to advanced care. I’ve worked with Sharad Mathur,MD, of the Kansas City VAMC on many clinical trials. He’s on the Kansas City VAMC Institutional Review Board and the cancer committee and is tuned in to veterans’ access to precision oncology. Kansas City was ordering Foundation One for select patients that met the criteria probably sooner than any other VA and participated in NCI Cooperative Group clinical trials. It is a great example of how veterans are getting access to

the same level of care as are patients who gettreated at NCI partners.

Comorbidities

Dr. Kambhampati. I don’t treat a lot of patients with lung cancer, but I find it easier to use these immuno-oncology drugs than platinums and etoposide. I consider them absolutely nasty chemotherapy drugs now in this era of immuno-oncology and targeted therapy.

Dr. Lynch. The VA is very important in translational lung cancer research and clinical care. It used to be thought that African American patients don’t get epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. And that’s because not enough African American patients with lung cancer were included in the NCI-based clinical trial.There are7,000 veterans who get lung cancer each year, and 20% to 25% of those are African Americans. Prevalence of various mutations and the pharmacogenetics of some of these drugs differ by patient ancestry. Including veterans with lung

cancer in precision oncology clinical trials and clinical care is not just a priority for the VA but a priority for NCI and internationally. I can’t emphasize this enough—veterans with lung cancer should be included in these studies and should be getting the same level of care that our partners are getting at NCI cancer centers. In the VA we’re positioned to do this because of our nationalelectronic health record (EHR) and becauseof our ability to identify patients with specific variants and enroll them in clinical trials.

Ms. Nason. One of the barriers that I find withsome of the patients that I have treated is getting them to a trial. If the trial isn’t available locally, specifically there are socioeconomic and distance issues that are hard to overcome.

Dr. Kaster. For smaller medical centers, getting patients to clinical trials can be difficult. The Boise VAMC is putting together a proposal now to justify hiring a research pharmacist in order to get trials atour site. The goal is to offer trial participation to our patients who otherwise might not be able to participate while offsetting some of the costs of immunotherapy. We are trying to make what could be a negative into a positive.

Measuring Success

Dr. Kambhampati. Unfortunately, we do not have any calculators to incorporate the quality of lives saved to the society. I know there are clearmetrics in transplant and in hematology, but unfortunately, there are no established metrics in solid tumor treatment that allow us to predict the cost savings to the health care system or to society or the benefit to the society. I don’t use any such predictive models or metrics in my decision making. These decisions are made based on existing evidence, and the existing evidence overwhelmingly supports use of immuno-oncology in certain types of solid tumors and in a select group of hematologic malignancies.

Dr. Kaster. This is where you can get more bang for your buck with an oncology pharmacist these days. A pharmacist can make a minor dosing change that will allow the same benefit for the patient, but could equal tens of thousands of dollars in cost-benefit for the VA. They can also be the second set of eyes when adjudicating a nonformulary request to ensure that a patient will benefit.

Dr. Lynch. Inappropriate prescribing is far more expensive than appropriate treatment. And the care for veterans whose long-term health outcomes could be improved by the new immunotherapies. It’s cheaper for veterans to be healthy and live longer than it is to take care of them in

their last 6 weeks of life. Unfortunately, there are not a lot of studies that have demonstrated that empirically, but I think it’s important to do those studies.

Role of Pharmacists

Dr. Lynch. I was at a meeting recently talking about how to improve veteran access to clinical trials. Francesca Cunningham, PharmD, director of the VA Center for Medication Safety of the VA Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM) described the commitment that pharmacy has in taking a leadership role in the integration of precision medicine. Linking veterans’ tumor mutation status and pharmacogenetic variants to pharmacy databases is the best way to ensure treatment is informed by genetics. We have to be realistic about what we’re asking community oncologists to do. With the onset of precision oncology, 10 cancers have become really 100 cancers. In the prior model of care, it was the oncologist, maybe in collaboration with a pathologist, but it was mostly oncologists who determined care.

And in the evolution of precision oncology, Ithink that it’s become an interdisciplinary adventure. Pharmacy is going to play an increasinglyimportant role in precision medicine around all of the molecular alterations, even immuno-oncology regardless of molecular status in which the VA has an advantage. We’re not talking about some community pharmacist. We’re talking about a national health care system where there’s a national EHR, where there’s national PBM systems. So my thoughts on this aspect is that it’s an intricate multidisciplinary team who can ensure that veteran sget the best care possible: the best most cost-effective care possible.

Dr. Kaster. As an oncology pharmacist, I have to second that.

Ms. Nason. As Dr. Kaster said earlier, having a dedicated oncology pharmacist is tremendouslybeneficial. The oncology/hematology pharmacists are following the patients closely and notice when dose adjustments need to be made, optimizing the drug benefit and providing additional safety. Not to mention the cost benefit that can be realized with appropriate adjustment and the expertise they bring to managing possible interactionsand pharmacodynamics.

Dr. Kambhampati. To brag about the Kansas City VAMC program, we have published in Federal Practitioner our best practices showing the collaboration between a pharmacist and providers.6 And we have used several examples of cost savings, which have basically helped us build the research program, and several examples of dual monitoring oral chemotherapy monitoring. And we have created these templates within the EHR that allow everyone to get a quick snapshot of where things are, what needs to be done, and what needs to be monitored.

Now, we are taking it a step further to determine when to stop chemotherapy or when to stop treatments. For example, for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), there are good data onstopping tyrosine kinase inhibitors.7 And that alone, if implemented across the VA, could bring

in huge cost savings, which perhaps could be put into investments in immuno-oncology or other efforts. We have several examples here that we have published, and we continue to increaseand strengthen our collaboration withour oncology pharmacist. We are very lucky and privileged to have a dedicated oncology pharmacistfor clinics and for research.

Dr. Lynch. The example of CML is perfect, because precision oncology has increased the complexity of care substantially. The VA is wellpositioned to be a leader in this area when care becomes this complex because of its ability to measure access to testing, to translate the results

of testing to pharmacy, to have pharmacists take the lead on prescribing, to have pathologists take the lead on molecular alterations, and to have oncologists take the lead on delivering the cancer care to the patients.

With hematologic malignancies, adherence in the early stages can result in patients getting offcare sooner, which is cost savings. But that requires access to testing, monitoring that testing, and working in partnership with pharmacy. This is a great story about how the VA is positioned to lead in this area of care.

Dr. Kaster. I would like to put a plug in for advanced practice providers and the use of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).The VA is well positioned because it often has established interdisciplinary teams with these providers, pharmacy, nursing, and often social work, to coordinate the care and manage symptoms outside of oncologist visits.

Dr. Lynch. In the NCI cancer center model, once the patient has become stable, the ongoing careis designated to the NP or PA. Then as soon as there’s a change and it requires reevaluation, the oncologist becomes involved again. That pointabout the oncology treatment team is totally in line

with some of the previous comments.

Areas For Further Investigation

Dr. Kaster. There are so many nuances that we’re finding out all of the time about immunotherapies. A recent study brought up the role of antibiotics in the 30 or possibly 60 days prior to immunotherapy.3 How does that change treatment? Which patients are more likely to benefit from immunotherapies, and which are susceptible to “hyperprogression”? How do we integrate palliative care discussions into the carenow that patients are feeling better on treatment and may be less likely to want to discuss palliative care?

Ms. Nason. I absolutely agree with that, especially keeping palliative care integrated within our services. Our focus is now a little different, in thatwe have more optimistic outcomes in mind, butthere still are symptoms and issues where our colleaguesin palliative care are invaluable.

Dr. Lynch. I third that motion. What I would really like to see come out of this discussion is how veterans are getting access to leading oncology care. We just published an analysis of Medicare data and access to EGFR testing. The result of that analysis showed that testing in the VA was consistent with testing in Medicare.

For palliative care, I think the VA does a better job. And it’s just so discouraging as VA employees and as clinicians treating veterans to see publicationsthat suggest that veterans are getting a lower quality of care and that they would be better if care was privatized or outsourced. It’s just fundamentally not the case.

In CML, we see it. We’ve analyzed the data, in that there’s a far lower number of patients with CML who are included in the registry because patients who are diagnosed outside the VA are incorporated in other cancer registries.8 But as soon as their copays increase for access to targeted drugs, they immediately activate their VA benefits so that theycan get their drugs at the VA. For hematologic malignancies that are diagnosed outside the VA and are captured in other cancer registries, as soon as the drugs become expensive, they start getting their care in the VA. I don’t think there’s beena lot of empirical research that’s shown this, but we have the data to illustrate this trend. I hope thatthere are more publications that show that veterans with cancer are getting really good care inside the VA in the existing VA health care system.

Ms. Nason. It is disheartening to see negativepublicity, knowing that I work with colleagues who are strongly committed to providing up-to-date and relevant oncology care.

Dr. Lynch. As we record this conversation, I am in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in a meeting about genomewide testing. In hematologic malignancies, prostate cancer, and breast cancer, it’s a huge issue. And that is the other area that MVP (Million Veteran Program) is leading the way with the MVP biorepository data. Frankly, there’s no other biorepository that has this many patients, that has so many African Americans, and that has such rich EHR data. So inthat other area, the VA is doing really well.

1. Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al; KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823-1833.

2. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al; PACIFIC Investigators. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–smallcell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919-1929.

3. Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu T-E, Pluzansk A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018 April 16. [Epub ahead of print.]

4. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al; CheckMate214 Investigators. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinibin advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1277-1290.

5. Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small cell

lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018 March 30. [Epub ahead of print.]

6. Heinrichs A, Dessars B, El Housni H, et al. Identification of chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib who are potentially eligible for treatment discontinuation by assessingreal-life molecular responses on the international scale in a EUTOS-certified lab. Leuk Res. 2018;67:27-31.

7. Keefe S, Kambhampati S, Powers B. An electronic chemotherapy ordering process and template. Fed Pract. 2015;32(suppl 1):21S-25S.

8. Lynch JA, Berse B, Rabb M, et al. Underutilization and disparities in access to EGFR testing among Medicare patients with lung cancer from 2010 - 2013. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):306.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference discussion recorded in April 2018.

Suman Kambhampati, MD. Immuno-oncology is a paradigm-shifting treatment approach. It is an easy-to-understand term for both providers and for patients. The underlying principle is that the body’s own immune system is used or stimulated to fight cancer, and there are drugs that clearly have shown huge promise for this, not only in oncology, but also for other diseases. Time will tell whether that really pans out or not, but to begin with, the emphasis has been inoncology, and therefore, the term immunooncology is fitting.

Dr. Kaster. It was encouraging at first, especially when ipilimumab came out, to see the effects on patients with melanoma. Then the KEYNOTE-024 trial came out, and we were able to jump in anduse monoclonal antibodies directed against programmed death 1 (PD-1) in the first line, which is when things got exciting.1 We have a smaller populationin Boise, so PD-1s in lung cancer have had the biggest impact on our patients so far.

Ellen Nason, RN, MSN. Patients are open to immunotherapies.They’re excited about it. And as the other panelists have said, you can start broadly, as the body fights the cancer on its own, to providing more specific details as a patient wants more information. Immuno-oncology is definitely accepted by patients, and they’re very excited about it, especially with all the news about new therapies.

Dr. Kambhampati. For the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) population, lung cancer has seen significant impact, and now it’s translating into other diseases through more research, trials, and better understanding about how these drugs are used and work.

The paradigm is shifting toward offering these drugs not only in metastatic cancers, but also in the surgically resectable tumors. The 2018 American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting, just concluded. At the meeting several abstracts reported instances where immunooncology drugs are being introduced in the early phases of lung cancer and showing outstanding results. It’s very much possible that we’re going to see less use of traditional chemotherapy in the near future.

Ms. Nason. I primarily work with solid tumors,and the majority of the population I work with have lung cancer. So we’re excited about some of the results that we’ve seen and the lower toxicity involved. Recently, we’ve begun using durvalumab with patients with stage III disease. We have about 5 people now that are using it as a maintenance or consolidative treatment vs just using it for patients with stage IV disease. Hopefully, we’ll see some of the same results describedin the paper published on it.2

Dr. Kaster. Yes, we are incorporating these new changes into care as they're coming out. As Ms. Nason mentioned, we're already using immunotherapies in earlier settings, and we are seeing as much research that could be translated into care soon, like combining immunotherapies

in first-line settings, as we see in the Checkmate-227 study with nivolumab and ipilimumab.3,4 The landscape is going to change dramatically in the next couple of years.

Accessing Testing For First-Line Treatments

Dr. Lynch. There has been an ongoing discussionin the literature on accessing appropriate testing—delays in testing can result in patients who are not able to access the best targeted drugs on a first-line basis. The drug companiesand the VA have become highly sensitized to ensuring that veterans are accessing the appropriate testing. We are expanding the capability of VA labs to do that testing.

Ms. Nason. I want to put in a plug for the VA Precision Oncology Program (POP). It’s about 2 years into its existence, and Neil Spector, MD, is the director. The POP pays for sequencing the tumor samples.

A new sequencing contract will go into effect October 2018 and will include sequencing for hematologic malignancies in addition to the current testing of solid tumors. Patients from New York who have been unable to receive testing through the current vendors used by POP, will be included in the new contract. It is important to note that POP is working closely with the National Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM) to develop a policy for approving off-label use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies based on sequenced data collected on patients tested through POP.

In addition, the leadership of POP is working to leverage the molecular testing results conducted through POP to improve veterans' access to clinical trials, both inside and outside the VA. Within the VA people can access information at tinyurl.com/precisiononcology. There is no reason why any eligible patient with cancer in the VA health care system should not have their tumor tissue sequenced through POP, particularly once the new contract goes into effect.

Dr. Lynch. Fortunately, the cost of next-generation sequencing has come down so much that most VA contracted reference laboratories offer next-generation sequencing, including LabCorp (Burlington,NC), Quest Diagnostics (Secaucus, NJ), Fulgent (Temple City, CA), and academic partners such as Oregon Health Sciences University and University of Washington.

Ms. Nason. At the Durham VAMC, sometimes a lack of tissue has been a barrier, but we now have the ability to send blood (liquid biopsy) for next-generation sequencing. Hopefully that will open up options for veterans with inadequate tissue. Importantly, all VA facilities can request liquid biopsiesthrough POP.

Dr. Lynch. That’s an important point. There have been huge advances in liquid biopsy testing.The VA Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS) was in talks with Genomic Health (Redwood City, CA) to do a study as part of clinical operations to look at the concordance between the liquid biopsy testing and the precision oncology data. But Genomic Health eventually abandoned its liquid biopsy testing. Currently, the VA is only reimbursing or encouraging liquid biopsy if the tissue is not available or if the veteran has too high a level of comorbidities to undergo tissue biopsy. The main point for the discussion today is that access to testing is a key component of access to all of these advanced drugs.

Dr. Kambhampati. The precision medicine piece will be a game changer—no question about that. Liquid biopsy is very timely. Many patients have difficulty getting rebiopsied, so liquid biopsy is definitely a big, big step forward.

Still, there has not been consistency across the VA as there should be. Perhaps there are a few select centers, including our site in Kansas City, where access to precision medicine is readily available and liquid biopsies are available. We use the PlasmaSELECT test from Personal Genome Diagnostics (Baltimore, MD). We have just added Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA) also in hematology. Access to mutational profilingis absolutely a must for precision medicine.

All that being said, the unique issue with immuno-oncology is that it pretty much transcends the mutational profile and perhaps has leveled the playing field, irrespective of the tumor mutation profile or burden. In some solid tumors these immuno-oncology drugs have been shown to work across tumor types and across different mutation types. And there is a hint now in the recent data presented at AACR and in the New England Journalof Medicine showing that the tumor mutational burden is a predictor of pathologic response to at least PD-1 blockade in the resectable stages of lung cancer.1,3 To me, that’s a very important piece of data because that’s something that can be tested and can have a prognostic impact in immuno-oncology, particularly in the early stages of lung cancer and is further proof of the broad value of immunotherapics in targeting tumors irrespective of the precise tumor targets.

Dr. Kaster. Yes, it’s nice to see other options like tumor mutational burden and Lung Immune Prognostic Index being studied.5 It would be nice if we could rely a little more on these, and not PD-L1, which as we all know is a variable and an unreliable target.

Dr. Kambhampati. I agree.

Rural Challenges In A Veterans Population

Dr. Lynch. Providing high-quality cancer care to rural veterans care can be a challenge but it is a VA priority. The VA National Genomic Medicine Services offers better access for rural veterans to germline genetic testing than any other healthcare system in the country. In terms of access to somatic testing and next-generation sequencing, we are working toward providing the same level of cancer care as patients would receive at National Cancer Institute (NCI) cancer centers. The VA oncology leadership has done teleconsults and virtual tumor boards, but for some rural VAMCs, fellowsare leading the clinical care. As we expand use of oral agents for oncology treatment, it will be easier to ensure that rural veterans receive the same standard of care for POP that veterans being cared for at VASLCHCS, Kansas City VAMC, or Durham VAMC get.

Dr. Kambhampati. The Kansas City VAMC in its catchment area includes underserved areas, such as Topeka and Leavenworth, Kansas. What we’ve been able to do here is something that’s unique—Kansas City VAMC is the only standalone VA in the country to be recognized as a primary SWOG (Southwestern Oncology Group) institution, which provides access to many trials, such as the Lung-MAP trial and others. And that has allowed us to use the full expanse of precision medicine without financial barriers. The research has helped us improve the standard of

care for patients across VISN 15.

Dr. Lynch. In precision oncology, the chief of pathology is an important figure in access to advanced care. I’ve worked with Sharad Mathur,MD, of the Kansas City VAMC on many clinical trials. He’s on the Kansas City VAMC Institutional Review Board and the cancer committee and is tuned in to veterans’ access to precision oncology. Kansas City was ordering Foundation One for select patients that met the criteria probably sooner than any other VA and participated in NCI Cooperative Group clinical trials. It is a great example of how veterans are getting access to

the same level of care as are patients who gettreated at NCI partners.

Comorbidities

Dr. Kambhampati. I don’t treat a lot of patients with lung cancer, but I find it easier to use these immuno-oncology drugs than platinums and etoposide. I consider them absolutely nasty chemotherapy drugs now in this era of immuno-oncology and targeted therapy.

Dr. Lynch. The VA is very important in translational lung cancer research and clinical care. It used to be thought that African American patients don’t get epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. And that’s because not enough African American patients with lung cancer were included in the NCI-based clinical trial.There are7,000 veterans who get lung cancer each year, and 20% to 25% of those are African Americans. Prevalence of various mutations and the pharmacogenetics of some of these drugs differ by patient ancestry. Including veterans with lung

cancer in precision oncology clinical trials and clinical care is not just a priority for the VA but a priority for NCI and internationally. I can’t emphasize this enough—veterans with lung cancer should be included in these studies and should be getting the same level of care that our partners are getting at NCI cancer centers. In the VA we’re positioned to do this because of our nationalelectronic health record (EHR) and becauseof our ability to identify patients with specific variants and enroll them in clinical trials.

Ms. Nason. One of the barriers that I find withsome of the patients that I have treated is getting them to a trial. If the trial isn’t available locally, specifically there are socioeconomic and distance issues that are hard to overcome.

Dr. Kaster. For smaller medical centers, getting patients to clinical trials can be difficult. The Boise VAMC is putting together a proposal now to justify hiring a research pharmacist in order to get trials atour site. The goal is to offer trial participation to our patients who otherwise might not be able to participate while offsetting some of the costs of immunotherapy. We are trying to make what could be a negative into a positive.

Measuring Success

Dr. Kambhampati. Unfortunately, we do not have any calculators to incorporate the quality of lives saved to the society. I know there are clearmetrics in transplant and in hematology, but unfortunately, there are no established metrics in solid tumor treatment that allow us to predict the cost savings to the health care system or to society or the benefit to the society. I don’t use any such predictive models or metrics in my decision making. These decisions are made based on existing evidence, and the existing evidence overwhelmingly supports use of immuno-oncology in certain types of solid tumors and in a select group of hematologic malignancies.

Dr. Kaster. This is where you can get more bang for your buck with an oncology pharmacist these days. A pharmacist can make a minor dosing change that will allow the same benefit for the patient, but could equal tens of thousands of dollars in cost-benefit for the VA. They can also be the second set of eyes when adjudicating a nonformulary request to ensure that a patient will benefit.

Dr. Lynch. Inappropriate prescribing is far more expensive than appropriate treatment. And the care for veterans whose long-term health outcomes could be improved by the new immunotherapies. It’s cheaper for veterans to be healthy and live longer than it is to take care of them in

their last 6 weeks of life. Unfortunately, there are not a lot of studies that have demonstrated that empirically, but I think it’s important to do those studies.

Role of Pharmacists

Dr. Lynch. I was at a meeting recently talking about how to improve veteran access to clinical trials. Francesca Cunningham, PharmD, director of the VA Center for Medication Safety of the VA Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM) described the commitment that pharmacy has in taking a leadership role in the integration of precision medicine. Linking veterans’ tumor mutation status and pharmacogenetic variants to pharmacy databases is the best way to ensure treatment is informed by genetics. We have to be realistic about what we’re asking community oncologists to do. With the onset of precision oncology, 10 cancers have become really 100 cancers. In the prior model of care, it was the oncologist, maybe in collaboration with a pathologist, but it was mostly oncologists who determined care.

And in the evolution of precision oncology, Ithink that it’s become an interdisciplinary adventure. Pharmacy is going to play an increasinglyimportant role in precision medicine around all of the molecular alterations, even immuno-oncology regardless of molecular status in which the VA has an advantage. We’re not talking about some community pharmacist. We’re talking about a national health care system where there’s a national EHR, where there’s national PBM systems. So my thoughts on this aspect is that it’s an intricate multidisciplinary team who can ensure that veteran sget the best care possible: the best most cost-effective care possible.

Dr. Kaster. As an oncology pharmacist, I have to second that.

Ms. Nason. As Dr. Kaster said earlier, having a dedicated oncology pharmacist is tremendouslybeneficial. The oncology/hematology pharmacists are following the patients closely and notice when dose adjustments need to be made, optimizing the drug benefit and providing additional safety. Not to mention the cost benefit that can be realized with appropriate adjustment and the expertise they bring to managing possible interactionsand pharmacodynamics.

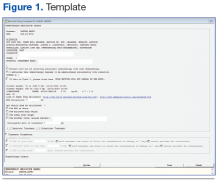

Dr. Kambhampati. To brag about the Kansas City VAMC program, we have published in Federal Practitioner our best practices showing the collaboration between a pharmacist and providers.6 And we have used several examples of cost savings, which have basically helped us build the research program, and several examples of dual monitoring oral chemotherapy monitoring. And we have created these templates within the EHR that allow everyone to get a quick snapshot of where things are, what needs to be done, and what needs to be monitored.

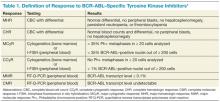

Now, we are taking it a step further to determine when to stop chemotherapy or when to stop treatments. For example, for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), there are good data onstopping tyrosine kinase inhibitors.7 And that alone, if implemented across the VA, could bring

in huge cost savings, which perhaps could be put into investments in immuno-oncology or other efforts. We have several examples here that we have published, and we continue to increaseand strengthen our collaboration withour oncology pharmacist. We are very lucky and privileged to have a dedicated oncology pharmacistfor clinics and for research.

Dr. Lynch. The example of CML is perfect, because precision oncology has increased the complexity of care substantially. The VA is wellpositioned to be a leader in this area when care becomes this complex because of its ability to measure access to testing, to translate the results

of testing to pharmacy, to have pharmacists take the lead on prescribing, to have pathologists take the lead on molecular alterations, and to have oncologists take the lead on delivering the cancer care to the patients.

With hematologic malignancies, adherence in the early stages can result in patients getting offcare sooner, which is cost savings. But that requires access to testing, monitoring that testing, and working in partnership with pharmacy. This is a great story about how the VA is positioned to lead in this area of care.

Dr. Kaster. I would like to put a plug in for advanced practice providers and the use of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).The VA is well positioned because it often has established interdisciplinary teams with these providers, pharmacy, nursing, and often social work, to coordinate the care and manage symptoms outside of oncologist visits.

Dr. Lynch. In the NCI cancer center model, once the patient has become stable, the ongoing careis designated to the NP or PA. Then as soon as there’s a change and it requires reevaluation, the oncologist becomes involved again. That pointabout the oncology treatment team is totally in line

with some of the previous comments.

Areas For Further Investigation

Dr. Kaster. There are so many nuances that we’re finding out all of the time about immunotherapies. A recent study brought up the role of antibiotics in the 30 or possibly 60 days prior to immunotherapy.3 How does that change treatment? Which patients are more likely to benefit from immunotherapies, and which are susceptible to “hyperprogression”? How do we integrate palliative care discussions into the carenow that patients are feeling better on treatment and may be less likely to want to discuss palliative care?

Ms. Nason. I absolutely agree with that, especially keeping palliative care integrated within our services. Our focus is now a little different, in thatwe have more optimistic outcomes in mind, butthere still are symptoms and issues where our colleaguesin palliative care are invaluable.

Dr. Lynch. I third that motion. What I would really like to see come out of this discussion is how veterans are getting access to leading oncology care. We just published an analysis of Medicare data and access to EGFR testing. The result of that analysis showed that testing in the VA was consistent with testing in Medicare.

For palliative care, I think the VA does a better job. And it’s just so discouraging as VA employees and as clinicians treating veterans to see publicationsthat suggest that veterans are getting a lower quality of care and that they would be better if care was privatized or outsourced. It’s just fundamentally not the case.

In CML, we see it. We’ve analyzed the data, in that there’s a far lower number of patients with CML who are included in the registry because patients who are diagnosed outside the VA are incorporated in other cancer registries.8 But as soon as their copays increase for access to targeted drugs, they immediately activate their VA benefits so that theycan get their drugs at the VA. For hematologic malignancies that are diagnosed outside the VA and are captured in other cancer registries, as soon as the drugs become expensive, they start getting their care in the VA. I don’t think there’s beena lot of empirical research that’s shown this, but we have the data to illustrate this trend. I hope thatthere are more publications that show that veterans with cancer are getting really good care inside the VA in the existing VA health care system.

Ms. Nason. It is disheartening to see negativepublicity, knowing that I work with colleagues who are strongly committed to providing up-to-date and relevant oncology care.

Dr. Lynch. As we record this conversation, I am in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in a meeting about genomewide testing. In hematologic malignancies, prostate cancer, and breast cancer, it’s a huge issue. And that is the other area that MVP (Million Veteran Program) is leading the way with the MVP biorepository data. Frankly, there’s no other biorepository that has this many patients, that has so many African Americans, and that has such rich EHR data. So inthat other area, the VA is doing really well.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference discussion recorded in April 2018.

Suman Kambhampati, MD. Immuno-oncology is a paradigm-shifting treatment approach. It is an easy-to-understand term for both providers and for patients. The underlying principle is that the body’s own immune system is used or stimulated to fight cancer, and there are drugs that clearly have shown huge promise for this, not only in oncology, but also for other diseases. Time will tell whether that really pans out or not, but to begin with, the emphasis has been inoncology, and therefore, the term immunooncology is fitting.

Dr. Kaster. It was encouraging at first, especially when ipilimumab came out, to see the effects on patients with melanoma. Then the KEYNOTE-024 trial came out, and we were able to jump in anduse monoclonal antibodies directed against programmed death 1 (PD-1) in the first line, which is when things got exciting.1 We have a smaller populationin Boise, so PD-1s in lung cancer have had the biggest impact on our patients so far.

Ellen Nason, RN, MSN. Patients are open to immunotherapies.They’re excited about it. And as the other panelists have said, you can start broadly, as the body fights the cancer on its own, to providing more specific details as a patient wants more information. Immuno-oncology is definitely accepted by patients, and they’re very excited about it, especially with all the news about new therapies.

Dr. Kambhampati. For the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) population, lung cancer has seen significant impact, and now it’s translating into other diseases through more research, trials, and better understanding about how these drugs are used and work.

The paradigm is shifting toward offering these drugs not only in metastatic cancers, but also in the surgically resectable tumors. The 2018 American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) meeting, just concluded. At the meeting several abstracts reported instances where immunooncology drugs are being introduced in the early phases of lung cancer and showing outstanding results. It’s very much possible that we’re going to see less use of traditional chemotherapy in the near future.

Ms. Nason. I primarily work with solid tumors,and the majority of the population I work with have lung cancer. So we’re excited about some of the results that we’ve seen and the lower toxicity involved. Recently, we’ve begun using durvalumab with patients with stage III disease. We have about 5 people now that are using it as a maintenance or consolidative treatment vs just using it for patients with stage IV disease. Hopefully, we’ll see some of the same results describedin the paper published on it.2

Dr. Kaster. Yes, we are incorporating these new changes into care as they're coming out. As Ms. Nason mentioned, we're already using immunotherapies in earlier settings, and we are seeing as much research that could be translated into care soon, like combining immunotherapies

in first-line settings, as we see in the Checkmate-227 study with nivolumab and ipilimumab.3,4 The landscape is going to change dramatically in the next couple of years.

Accessing Testing For First-Line Treatments

Dr. Lynch. There has been an ongoing discussionin the literature on accessing appropriate testing—delays in testing can result in patients who are not able to access the best targeted drugs on a first-line basis. The drug companiesand the VA have become highly sensitized to ensuring that veterans are accessing the appropriate testing. We are expanding the capability of VA labs to do that testing.

Ms. Nason. I want to put in a plug for the VA Precision Oncology Program (POP). It’s about 2 years into its existence, and Neil Spector, MD, is the director. The POP pays for sequencing the tumor samples.

A new sequencing contract will go into effect October 2018 and will include sequencing for hematologic malignancies in addition to the current testing of solid tumors. Patients from New York who have been unable to receive testing through the current vendors used by POP, will be included in the new contract. It is important to note that POP is working closely with the National Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM) to develop a policy for approving off-label use of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapies based on sequenced data collected on patients tested through POP.

In addition, the leadership of POP is working to leverage the molecular testing results conducted through POP to improve veterans' access to clinical trials, both inside and outside the VA. Within the VA people can access information at tinyurl.com/precisiononcology. There is no reason why any eligible patient with cancer in the VA health care system should not have their tumor tissue sequenced through POP, particularly once the new contract goes into effect.

Dr. Lynch. Fortunately, the cost of next-generation sequencing has come down so much that most VA contracted reference laboratories offer next-generation sequencing, including LabCorp (Burlington,NC), Quest Diagnostics (Secaucus, NJ), Fulgent (Temple City, CA), and academic partners such as Oregon Health Sciences University and University of Washington.

Ms. Nason. At the Durham VAMC, sometimes a lack of tissue has been a barrier, but we now have the ability to send blood (liquid biopsy) for next-generation sequencing. Hopefully that will open up options for veterans with inadequate tissue. Importantly, all VA facilities can request liquid biopsiesthrough POP.

Dr. Lynch. That’s an important point. There have been huge advances in liquid biopsy testing.The VA Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS) was in talks with Genomic Health (Redwood City, CA) to do a study as part of clinical operations to look at the concordance between the liquid biopsy testing and the precision oncology data. But Genomic Health eventually abandoned its liquid biopsy testing. Currently, the VA is only reimbursing or encouraging liquid biopsy if the tissue is not available or if the veteran has too high a level of comorbidities to undergo tissue biopsy. The main point for the discussion today is that access to testing is a key component of access to all of these advanced drugs.

Dr. Kambhampati. The precision medicine piece will be a game changer—no question about that. Liquid biopsy is very timely. Many patients have difficulty getting rebiopsied, so liquid biopsy is definitely a big, big step forward.

Still, there has not been consistency across the VA as there should be. Perhaps there are a few select centers, including our site in Kansas City, where access to precision medicine is readily available and liquid biopsies are available. We use the PlasmaSELECT test from Personal Genome Diagnostics (Baltimore, MD). We have just added Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA) also in hematology. Access to mutational profilingis absolutely a must for precision medicine.

All that being said, the unique issue with immuno-oncology is that it pretty much transcends the mutational profile and perhaps has leveled the playing field, irrespective of the tumor mutation profile or burden. In some solid tumors these immuno-oncology drugs have been shown to work across tumor types and across different mutation types. And there is a hint now in the recent data presented at AACR and in the New England Journalof Medicine showing that the tumor mutational burden is a predictor of pathologic response to at least PD-1 blockade in the resectable stages of lung cancer.1,3 To me, that’s a very important piece of data because that’s something that can be tested and can have a prognostic impact in immuno-oncology, particularly in the early stages of lung cancer and is further proof of the broad value of immunotherapics in targeting tumors irrespective of the precise tumor targets.

Dr. Kaster. Yes, it’s nice to see other options like tumor mutational burden and Lung Immune Prognostic Index being studied.5 It would be nice if we could rely a little more on these, and not PD-L1, which as we all know is a variable and an unreliable target.

Dr. Kambhampati. I agree.

Rural Challenges In A Veterans Population

Dr. Lynch. Providing high-quality cancer care to rural veterans care can be a challenge but it is a VA priority. The VA National Genomic Medicine Services offers better access for rural veterans to germline genetic testing than any other healthcare system in the country. In terms of access to somatic testing and next-generation sequencing, we are working toward providing the same level of cancer care as patients would receive at National Cancer Institute (NCI) cancer centers. The VA oncology leadership has done teleconsults and virtual tumor boards, but for some rural VAMCs, fellowsare leading the clinical care. As we expand use of oral agents for oncology treatment, it will be easier to ensure that rural veterans receive the same standard of care for POP that veterans being cared for at VASLCHCS, Kansas City VAMC, or Durham VAMC get.

Dr. Kambhampati. The Kansas City VAMC in its catchment area includes underserved areas, such as Topeka and Leavenworth, Kansas. What we’ve been able to do here is something that’s unique—Kansas City VAMC is the only standalone VA in the country to be recognized as a primary SWOG (Southwestern Oncology Group) institution, which provides access to many trials, such as the Lung-MAP trial and others. And that has allowed us to use the full expanse of precision medicine without financial barriers. The research has helped us improve the standard of

care for patients across VISN 15.

Dr. Lynch. In precision oncology, the chief of pathology is an important figure in access to advanced care. I’ve worked with Sharad Mathur,MD, of the Kansas City VAMC on many clinical trials. He’s on the Kansas City VAMC Institutional Review Board and the cancer committee and is tuned in to veterans’ access to precision oncology. Kansas City was ordering Foundation One for select patients that met the criteria probably sooner than any other VA and participated in NCI Cooperative Group clinical trials. It is a great example of how veterans are getting access to

the same level of care as are patients who gettreated at NCI partners.

Comorbidities

Dr. Kambhampati. I don’t treat a lot of patients with lung cancer, but I find it easier to use these immuno-oncology drugs than platinums and etoposide. I consider them absolutely nasty chemotherapy drugs now in this era of immuno-oncology and targeted therapy.

Dr. Lynch. The VA is very important in translational lung cancer research and clinical care. It used to be thought that African American patients don’t get epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. And that’s because not enough African American patients with lung cancer were included in the NCI-based clinical trial.There are7,000 veterans who get lung cancer each year, and 20% to 25% of those are African Americans. Prevalence of various mutations and the pharmacogenetics of some of these drugs differ by patient ancestry. Including veterans with lung

cancer in precision oncology clinical trials and clinical care is not just a priority for the VA but a priority for NCI and internationally. I can’t emphasize this enough—veterans with lung cancer should be included in these studies and should be getting the same level of care that our partners are getting at NCI cancer centers. In the VA we’re positioned to do this because of our nationalelectronic health record (EHR) and becauseof our ability to identify patients with specific variants and enroll them in clinical trials.

Ms. Nason. One of the barriers that I find withsome of the patients that I have treated is getting them to a trial. If the trial isn’t available locally, specifically there are socioeconomic and distance issues that are hard to overcome.

Dr. Kaster. For smaller medical centers, getting patients to clinical trials can be difficult. The Boise VAMC is putting together a proposal now to justify hiring a research pharmacist in order to get trials atour site. The goal is to offer trial participation to our patients who otherwise might not be able to participate while offsetting some of the costs of immunotherapy. We are trying to make what could be a negative into a positive.

Measuring Success

Dr. Kambhampati. Unfortunately, we do not have any calculators to incorporate the quality of lives saved to the society. I know there are clearmetrics in transplant and in hematology, but unfortunately, there are no established metrics in solid tumor treatment that allow us to predict the cost savings to the health care system or to society or the benefit to the society. I don’t use any such predictive models or metrics in my decision making. These decisions are made based on existing evidence, and the existing evidence overwhelmingly supports use of immuno-oncology in certain types of solid tumors and in a select group of hematologic malignancies.

Dr. Kaster. This is where you can get more bang for your buck with an oncology pharmacist these days. A pharmacist can make a minor dosing change that will allow the same benefit for the patient, but could equal tens of thousands of dollars in cost-benefit for the VA. They can also be the second set of eyes when adjudicating a nonformulary request to ensure that a patient will benefit.

Dr. Lynch. Inappropriate prescribing is far more expensive than appropriate treatment. And the care for veterans whose long-term health outcomes could be improved by the new immunotherapies. It’s cheaper for veterans to be healthy and live longer than it is to take care of them in

their last 6 weeks of life. Unfortunately, there are not a lot of studies that have demonstrated that empirically, but I think it’s important to do those studies.

Role of Pharmacists

Dr. Lynch. I was at a meeting recently talking about how to improve veteran access to clinical trials. Francesca Cunningham, PharmD, director of the VA Center for Medication Safety of the VA Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM) described the commitment that pharmacy has in taking a leadership role in the integration of precision medicine. Linking veterans’ tumor mutation status and pharmacogenetic variants to pharmacy databases is the best way to ensure treatment is informed by genetics. We have to be realistic about what we’re asking community oncologists to do. With the onset of precision oncology, 10 cancers have become really 100 cancers. In the prior model of care, it was the oncologist, maybe in collaboration with a pathologist, but it was mostly oncologists who determined care.

And in the evolution of precision oncology, Ithink that it’s become an interdisciplinary adventure. Pharmacy is going to play an increasinglyimportant role in precision medicine around all of the molecular alterations, even immuno-oncology regardless of molecular status in which the VA has an advantage. We’re not talking about some community pharmacist. We’re talking about a national health care system where there’s a national EHR, where there’s national PBM systems. So my thoughts on this aspect is that it’s an intricate multidisciplinary team who can ensure that veteran sget the best care possible: the best most cost-effective care possible.

Dr. Kaster. As an oncology pharmacist, I have to second that.

Ms. Nason. As Dr. Kaster said earlier, having a dedicated oncology pharmacist is tremendouslybeneficial. The oncology/hematology pharmacists are following the patients closely and notice when dose adjustments need to be made, optimizing the drug benefit and providing additional safety. Not to mention the cost benefit that can be realized with appropriate adjustment and the expertise they bring to managing possible interactionsand pharmacodynamics.

Dr. Kambhampati. To brag about the Kansas City VAMC program, we have published in Federal Practitioner our best practices showing the collaboration between a pharmacist and providers.6 And we have used several examples of cost savings, which have basically helped us build the research program, and several examples of dual monitoring oral chemotherapy monitoring. And we have created these templates within the EHR that allow everyone to get a quick snapshot of where things are, what needs to be done, and what needs to be monitored.

Now, we are taking it a step further to determine when to stop chemotherapy or when to stop treatments. For example, for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), there are good data onstopping tyrosine kinase inhibitors.7 And that alone, if implemented across the VA, could bring

in huge cost savings, which perhaps could be put into investments in immuno-oncology or other efforts. We have several examples here that we have published, and we continue to increaseand strengthen our collaboration withour oncology pharmacist. We are very lucky and privileged to have a dedicated oncology pharmacistfor clinics and for research.

Dr. Lynch. The example of CML is perfect, because precision oncology has increased the complexity of care substantially. The VA is wellpositioned to be a leader in this area when care becomes this complex because of its ability to measure access to testing, to translate the results

of testing to pharmacy, to have pharmacists take the lead on prescribing, to have pathologists take the lead on molecular alterations, and to have oncologists take the lead on delivering the cancer care to the patients.

With hematologic malignancies, adherence in the early stages can result in patients getting offcare sooner, which is cost savings. But that requires access to testing, monitoring that testing, and working in partnership with pharmacy. This is a great story about how the VA is positioned to lead in this area of care.

Dr. Kaster. I would like to put a plug in for advanced practice providers and the use of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).The VA is well positioned because it often has established interdisciplinary teams with these providers, pharmacy, nursing, and often social work, to coordinate the care and manage symptoms outside of oncologist visits.

Dr. Lynch. In the NCI cancer center model, once the patient has become stable, the ongoing careis designated to the NP or PA. Then as soon as there’s a change and it requires reevaluation, the oncologist becomes involved again. That pointabout the oncology treatment team is totally in line

with some of the previous comments.

Areas For Further Investigation

Dr. Kaster. There are so many nuances that we’re finding out all of the time about immunotherapies. A recent study brought up the role of antibiotics in the 30 or possibly 60 days prior to immunotherapy.3 How does that change treatment? Which patients are more likely to benefit from immunotherapies, and which are susceptible to “hyperprogression”? How do we integrate palliative care discussions into the carenow that patients are feeling better on treatment and may be less likely to want to discuss palliative care?

Ms. Nason. I absolutely agree with that, especially keeping palliative care integrated within our services. Our focus is now a little different, in thatwe have more optimistic outcomes in mind, butthere still are symptoms and issues where our colleaguesin palliative care are invaluable.

Dr. Lynch. I third that motion. What I would really like to see come out of this discussion is how veterans are getting access to leading oncology care. We just published an analysis of Medicare data and access to EGFR testing. The result of that analysis showed that testing in the VA was consistent with testing in Medicare.

For palliative care, I think the VA does a better job. And it’s just so discouraging as VA employees and as clinicians treating veterans to see publicationsthat suggest that veterans are getting a lower quality of care and that they would be better if care was privatized or outsourced. It’s just fundamentally not the case.

In CML, we see it. We’ve analyzed the data, in that there’s a far lower number of patients with CML who are included in the registry because patients who are diagnosed outside the VA are incorporated in other cancer registries.8 But as soon as their copays increase for access to targeted drugs, they immediately activate their VA benefits so that theycan get their drugs at the VA. For hematologic malignancies that are diagnosed outside the VA and are captured in other cancer registries, as soon as the drugs become expensive, they start getting their care in the VA. I don’t think there’s beena lot of empirical research that’s shown this, but we have the data to illustrate this trend. I hope thatthere are more publications that show that veterans with cancer are getting really good care inside the VA in the existing VA health care system.

Ms. Nason. It is disheartening to see negativepublicity, knowing that I work with colleagues who are strongly committed to providing up-to-date and relevant oncology care.

Dr. Lynch. As we record this conversation, I am in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in a meeting about genomewide testing. In hematologic malignancies, prostate cancer, and breast cancer, it’s a huge issue. And that is the other area that MVP (Million Veteran Program) is leading the way with the MVP biorepository data. Frankly, there’s no other biorepository that has this many patients, that has so many African Americans, and that has such rich EHR data. So inthat other area, the VA is doing really well.

1. Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al; KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823-1833.

2. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al; PACIFIC Investigators. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–smallcell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919-1929.

3. Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu T-E, Pluzansk A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018 April 16. [Epub ahead of print.]

4. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al; CheckMate214 Investigators. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinibin advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1277-1290.

5. Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small cell

lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018 March 30. [Epub ahead of print.]

6. Heinrichs A, Dessars B, El Housni H, et al. Identification of chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib who are potentially eligible for treatment discontinuation by assessingreal-life molecular responses on the international scale in a EUTOS-certified lab. Leuk Res. 2018;67:27-31.

7. Keefe S, Kambhampati S, Powers B. An electronic chemotherapy ordering process and template. Fed Pract. 2015;32(suppl 1):21S-25S.

8. Lynch JA, Berse B, Rabb M, et al. Underutilization and disparities in access to EGFR testing among Medicare patients with lung cancer from 2010 - 2013. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):306.

1. Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al; KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823-1833.

2. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al; PACIFIC Investigators. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–smallcell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919-1929.

3. Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu T-E, Pluzansk A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018 April 16. [Epub ahead of print.]

4. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al; CheckMate214 Investigators. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinibin advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1277-1290.

5. Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small cell

lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018 March 30. [Epub ahead of print.]

6. Heinrichs A, Dessars B, El Housni H, et al. Identification of chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib who are potentially eligible for treatment discontinuation by assessingreal-life molecular responses on the international scale in a EUTOS-certified lab. Leuk Res. 2018;67:27-31.

7. Keefe S, Kambhampati S, Powers B. An electronic chemotherapy ordering process and template. Fed Pract. 2015;32(suppl 1):21S-25S.

8. Lynch JA, Berse B, Rabb M, et al. Underutilization and disparities in access to EGFR testing among Medicare patients with lung cancer from 2010 - 2013. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):306.

Positivity Rates in Oropharyngeal and Nonoropharyngeal Head and Neck Cancer in the VA

Head and neck cancer (HNC) continues to be a major health issue with an estimated 51,540 cases in the US in 2018, making it the eighth most common cancer among men with an estimated 4% of all new cancer diagnoses.1 Over the past decade, human papillomavirus (HPV) has emerged as a major prognostic factor for survival in squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx. Patients who are HPV-positive (HPV+) have a much higher survival rate than patients who have HPV-negative (HPV-) cancers of the oropharynx. The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual has 2 distinct stagings for HPV+ and HPV- oropharyngeal tumors using p16-positivity (p16+) as a surrogate marker.2

Squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx that are HPV+ have about half the risk of death of HPV- tumors, are highly responsive to treatment, and are more often seen in younger and healthier patients with little to no tobacco use.2,3 As such, there also is a movement to de-escalate HPV+ oropharyngeal cancers with multiple trials by either replacing cytotoxic chemotherapy with a targeted agent (cisplatin vs cetuximab in RTOG 1016) or reducing the radiation dose (ECOG 1308, NRG HN002, Quarterback, and OPTIMA trials).3

The focus of many epidemiologic studies has been in the HNC general population. A recent epidemiologic analysis of the HNC general population found a p16 positivity rate of 60% in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) and 10% in nonoropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (NOPSCC).4 There has been a lack of studies focusing on the US Department of Veterans Administration (VA) population. The VA HNC population consists mostly of older white male smokers; whereas the rise of OPSCC in the general population consists primarily of males aged < 60 years often with little or no tobacco use.5 Furthermore, the importance of p16 positivity in NOPSCC also may be prognostic.6 Population data on this subset in the VA are lacking as well.This study’s purpose is to analyze the p16 positivity rate in both the OPSCC and NOPSCC in the VA population. Elucidation of epidemiologic factors that are associated with these groups may bring to light important differences between the VA and general HNC populations.

Methods

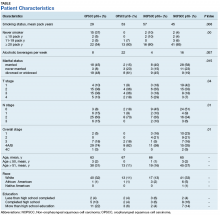

A review of the Kansas City VA Medical Center database for patients with HNC was performed from 2011 to 2017. The review consisted of 183 patient records (second primaries were scored separately), and 123 were deemed eligible for the study. Epidemiologic data were collected, including site, OPSCC vs NOPSCC, age, race, education level, tobacco use, alcohol use, TNM stage, and marital status (Table).

Results

The NOPSCC p16+ group had the greatest mean pack-year use (57). The lowest was in the OPSCC p16+ group (29). The OPSCC p16+ group had 37% never smokers compared with ≤ 10% for the other groups. Both the OPSCC and NOPSCC p16- groups had much more alcohol use per week than that of the p16+ groups. The differences in marital status included a lower rate of never married individuals in the p16+ group and a higher rate of marriage in the NOPSCC p16- group. The T stage distribution within the OPSCC groups was similar, but NOPSCC groups saw more T1 lesions in the NOPSCC p16- group (42% p16- vs 18% p16+). Conversely, more T4 lesions were found in the NOPSCC p16+ patients (7% p16- vs 29% p16+).

Discussion

The overall HPV positivity rate in the general population of patients with HNC has been reported as between 57% and 72% for OPSCC and between 1.3% and 7% for NOPSCC.6 One study, however, examined the p16 positivity rate in NOPSCC patients enrolled in major trials (RTOG 0129, 0234, and 0522 studies) and found that up to 19.3% of NOPSCC patients had p16 positivity.6 Even with the near 20% rate in those aforementioned trials that are above the reported norm, the current study found that nearly 30% of its VA population had p16+ NOPSCC. It has been shown that regardless of site, HPV-driven head and neck tumors share a similar gene expression and DNA methylation profiles (nonkeratinizing, basaloid histopathologic features, and lack of TP53 or CDKN2A alterations).5 p16+ NOPSCC has a different immune microenvironment with less lymphocyte infiltration, and there is some debate in the literature about the effects on tumor outcomes for NOPSCC cancer.5

In the aforementioned RTOG trials, p16- NOPSCC had worse outcomes compared with those of p16+ NOPSCC.6 This result is in contrast to the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) and the combined Johns Hopkins University (JHU) and University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) data that found no difference between p16+ NOPSCC or p16- NOPSCC.7,8 In regards to race, this study did not find any differences. Another UCSF and JHU study showed lower p16+ rates in African American patients with OPSCC, but no distinction between race in the NOPSCC group. This result is consistent with the data in the current study as the distribution of race was no different among the 4 groups; however, this study's cohort was 90% white, 10% African American, and only < 1% Native American.4 This study's cohort population also was consistent with HPV-positive tumors presenting with earlier T, but higher N staging.9

Smoking is known to decrease survival in HPV-positive HNC, with the RTOG 0129 study separating head and neck tumors into low, medium, and high risk, based on HPV status, smoking, and stage.10 Although the average smoking pack-years in the current study’s OPC p16+ group was high at 29 pack-years, there was still a significant number of nonsmokers in that same group (37%). The University of Michigan conducted a study that had a similar profile of patients with an average age of 56.5 and 32.4% never smokers in their p16+ OPSCC cohort; thus, the VA p16+ OPSCC group in this study may be similar to the general population's p16+ OPSCC group.11 Nonmonogamous relationships also have been shown to be a risk factor for HPV positivity, and there was a difference in marital status (assuming it was a surrogate for monogamy) between the 4 groups; however, in contrast, the p16+ group in the current study had a high number of married patients, 45% in OPC p16+ group, and may not have been a good surrogate for monogamy in this VA population.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include all the caveats that come with a retrospective study, such as confounding variables, unbalanced groups, and selection bias. A detailed sexual history was not included, although it is well known that sexual activity is linked with oral HPV positivity.12 Human papillomavirus positivity based on p16 immunohistochemical analysis also was used as a surrogate marker for HPV instead of DNA in situ hybridization. The data also may be skewed due to the study patient’s being predominantly white and male: Both groups have a higher predilection for HPV-driven HNCs.13

Conclusion

The proportion of p16+ VA OPSCC cases was similar to that of the general population at 75% with 37% never smokers, but the percentage in NOPSCC was higher at 29% with only 10% never smokers. The p16+ NOPSCC also presented with more T4 lesions and a higher overall stage compared with p16- NOPSCC. Further studies are needed to compare these subgroups in the VA and in the general HNC populations.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

2. Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. Head and neck cancers major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):122-137.

3. Mirghani H, Blanchard P. Treatment de-escalation for HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer: where do we stand? Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2017;8:4-11.

4. D’Souza G, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. Differences in the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck squamous cell cancers by sex, race, anatomic tumor site, and HPV detection method. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):169-177.

5. Chakravarthy A, Henderson S, Thirdborough SM, et al. Human papillomavirus drives tumor development throughout the head and neck: improved prognosis is associated with an immune response largely restricted to the oropharynx. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(34):4132-4141.

6. Chung CH, Zhang Q, Kong CS, et al. p16 protein expression and human papillomavirus status as prognostic biomarkers of nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(35):3930-3938.

7. Lassen P, Primdahl H, Johansen J, et al; Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA). Impact of HPV-associated p16-expression on radiotherapy outcome in advanced oropharynx and non-oropharynx cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;113(3):310-316.

8. Fakhry C, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. The prognostic role of sex, race, and human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1566-1575.

9. Elrefaey S, Massaro MA, Chiocca S, Chiesa F, Ansarin M. HPV in oropharyngeal cancer: the basics to know in clinical practice. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34(5):299-309.

10. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35.