User login

Photolichenoid Dermatitis: A Presenting Sign of Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Photolichenoid dermatitis is an uncommon eruptive dermatitis of variable clinical presentation. It has a histopathologic pattern of lichenoid inflammation and is best characterized as a photoallergic reaction.1 Photolichenoid dermatitis was first described in 1954 in association with the use of quinidine in the treatment of malaria.2 Subsequently, it has been associated with various medications, including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.1,2 Photolichenoid dermatitis has been documented in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with variable clinical presentations. Photolichenoid dermatitis in patients with HIV has been described both with and without an associated photosensitizing systemic agent, suggesting that HIV infection is an independent risk factor for the development of this eruption in patients with HIV.3-6

Case Report

A 62-year-old African man presented for evaluation of asymptomatic hypopigmented and depigmented patches in a photodistributed pattern. The eruption began the preceding summer when he noted a pink patch on the right side of the forehead. It progressed over 2 months to involve the face, ears, neck, and arms. His medical history was negative. The only medication he was taking was hydroxychloroquine, which was prescribed by another dermatologist when the patient first developed the eruption. The patient was unsure of the indication for the medication and admitted to poor compliance. A review of systems was negative. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune disease. A detailed sexual history and illicit drug history were not obtained. Physical examination revealed hypopigmented and depigmented patches, some with overlying erythema and collarettes of fine scale. The patches were photodistributed on the face, conchal bowls, neck, dorsal aspect of the hands, and extensor forearms (Figures 1 and 2). Macules of repigmentation were noted within some of the patches. There also were large hyperpigmented patches with peripheral hypopigmentation on the legs.

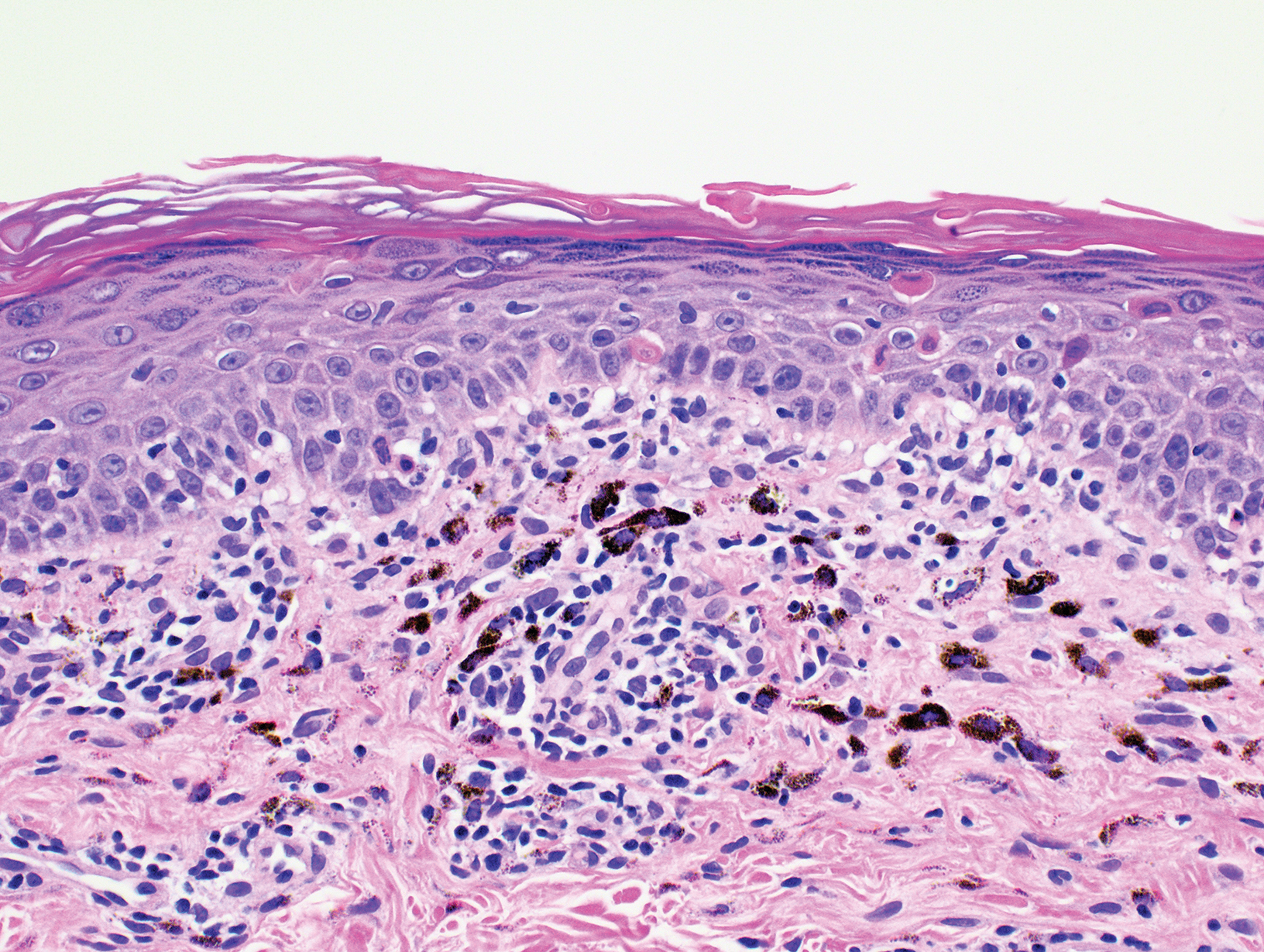

A punch biopsy taken from the left posterior neck revealed a patchy bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with lymphocytes present at the dermoepidermal junction and scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes extending into the mid spinous layer (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with photolichenoid dermatitis.

Laboratory workup revealed a normal complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel. Other negative results included antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro antibody, anti-La antibody, QuantiFERON-TB Gold, syphilis IgG antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody. Positive results included hepatitis B antibody, hepatitis C antibody, and HIV-2 antibody. The patient denied overt symptoms suggestive of an immunocompromised status, including fever, chills, weight loss, or diarrhea. Initial treatment included mid-potency topical steroids with continued progression of the eruption. Following histopathologic and laboratory results indicating photolichenoid eruption, treatment with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was resumed. The patient was counseled on the importance of sun protection and was referred to an infectious disease clinic for treatment of HIV. He was ultimately lost to follow-up before further laboratory workup was obtained. Therefore, his CD4+ T-cell count and viral load were not obtained.

Comment

Prevalence of Photosensitive Eruptions

Photodermatitis is an uncommon clinical manifestation of HIV occurring in approximately 5% of patients who are HIV positive.3 Photosensitive eruptions previously described in association with HIV include porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, chronic actinic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, photodistributed dyspigmentation, and lichenoid photodermatitis.7 These HIV-associated photosensitive eruptions have been found to disproportionally affect patients of African and Native American descent.5,7,8 Therefore, a new photodistributed eruption in a patient of African or Native American descent should prompt evaluation of possible underlying HIV infection.

Presenting Sign of HIV Infection

We report a case of photolichenoid dermatitis presenting with loss of pigmentation as a presenting sign of HIV. The patient had no known history of HIV or prior opportunistic infections and was not taking any medications at the time of onset or presentation to clinic. Similar cases of photodistributed depigmentation with lichenoid inflammation on histopathology occurring in patients with HIV have been previously described.4-6,9 In these cases, most patients were of African descent with previously diagnosed advanced HIV and CD4 counts of less than 50 cells/mL3. The additional clinical findings of lichenoid papules and plaques were noted in several of these cases.5,6

Exposure to Photosensitizing Drugs

Photodermatitis in patients with HIV often is attributed to exposure to a photosensitizing drug. Many reported cases are retrospective and identify a temporal association between the onset of photodermatitis following the initiation of a photosensitizing drug. The most commonly implicated drugs have included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin. Other potential offenders may include saquinavir, dapsone, ketoconazole, and efavirenz.3,5 In cases in which temporal association with a new medication could not be identified, the photodermatitis often has been presumed to be due to polypharmacy and the potential synergistic effect of multiple photosensitizing drugs.3,5-8

Advanced HIV

There are several reported cases of photodermatitis occurring in patients who were not exposed to systemic photosensitizers. These patients had advanced HIV, meeting criteria for AIDS with a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mL3. The majority of patients had an even lower CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mL3. Clinical presentations have included photodistributed lichenoid papules and plaques as well as depigmented patches.4,5,8,10

Evaluating HIV as a Risk Factor for Photodermatitis

Discerning the validity of the correlation between photodermatitis and HIV is difficult, as all previously reported cases are case reports and small retrospective case series.

Conclusion

This case represents an uncommon presentation of photolichenoid dermatitis as the presenting sign of HIV infection.10 Although most reported cases of photodermatitis in HIV are attributed to photosensitizing drugs, we propose that HIV may be an independent risk factor for the development of photodermatitis. We recommend consideration of HIV testing in patients who present with photodistributed depigmenting eruptions, even in the absence of a photosensitizing drug, particularly in patients of African and Native American descent.

- Collazo MH, Sanchez JL, Figueroa LD. Defining lichenoid photodermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:239-242.

- Wechsler HL. Dermatitis medicamentosa; a lichen-planus-like eruption due to quinidine. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:741-744.

- Bilu D, Mamelak AJ, Nguyen RH, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characterization of photosensitivity in HIV-positive individuals. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20:175-183.

- Philips RC, Motaparthi K, Krishnan B, et al. HIV photodermatitis presenting with widespread vitiligo-like depigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:6.

- Berger TG, Dhar A. Lichenoid photoeruptions in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:609-613.

- Tran K, Hartman R, Tzu J, et al. Photolichenoid plaques with associated vitiliginous pigmentary changes. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13.

- Gregory N, DeLeo VA. Clinical manifestations of photosensitivity in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:630-633.

- Vin-Christian K, Epstein JH, Maurer TA, et al. Photosensitivity in HIV-infected individuals. J Dermatol. 2000;27:361-369.

- Kigonya C, Lutwama F, Colebunders R. Extensive hypopigmentation after starting antiretroviral treatment in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive African woman. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:102-103.

- Pardo RJ, Kerdel FA. Hypertrophic lichen planus and light sensitivity in an HIV-positive patient. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:642-644.

Photolichenoid dermatitis is an uncommon eruptive dermatitis of variable clinical presentation. It has a histopathologic pattern of lichenoid inflammation and is best characterized as a photoallergic reaction.1 Photolichenoid dermatitis was first described in 1954 in association with the use of quinidine in the treatment of malaria.2 Subsequently, it has been associated with various medications, including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.1,2 Photolichenoid dermatitis has been documented in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with variable clinical presentations. Photolichenoid dermatitis in patients with HIV has been described both with and without an associated photosensitizing systemic agent, suggesting that HIV infection is an independent risk factor for the development of this eruption in patients with HIV.3-6

Case Report

A 62-year-old African man presented for evaluation of asymptomatic hypopigmented and depigmented patches in a photodistributed pattern. The eruption began the preceding summer when he noted a pink patch on the right side of the forehead. It progressed over 2 months to involve the face, ears, neck, and arms. His medical history was negative. The only medication he was taking was hydroxychloroquine, which was prescribed by another dermatologist when the patient first developed the eruption. The patient was unsure of the indication for the medication and admitted to poor compliance. A review of systems was negative. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune disease. A detailed sexual history and illicit drug history were not obtained. Physical examination revealed hypopigmented and depigmented patches, some with overlying erythema and collarettes of fine scale. The patches were photodistributed on the face, conchal bowls, neck, dorsal aspect of the hands, and extensor forearms (Figures 1 and 2). Macules of repigmentation were noted within some of the patches. There also were large hyperpigmented patches with peripheral hypopigmentation on the legs.

A punch biopsy taken from the left posterior neck revealed a patchy bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with lymphocytes present at the dermoepidermal junction and scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes extending into the mid spinous layer (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with photolichenoid dermatitis.

Laboratory workup revealed a normal complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel. Other negative results included antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro antibody, anti-La antibody, QuantiFERON-TB Gold, syphilis IgG antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody. Positive results included hepatitis B antibody, hepatitis C antibody, and HIV-2 antibody. The patient denied overt symptoms suggestive of an immunocompromised status, including fever, chills, weight loss, or diarrhea. Initial treatment included mid-potency topical steroids with continued progression of the eruption. Following histopathologic and laboratory results indicating photolichenoid eruption, treatment with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was resumed. The patient was counseled on the importance of sun protection and was referred to an infectious disease clinic for treatment of HIV. He was ultimately lost to follow-up before further laboratory workup was obtained. Therefore, his CD4+ T-cell count and viral load were not obtained.

Comment

Prevalence of Photosensitive Eruptions

Photodermatitis is an uncommon clinical manifestation of HIV occurring in approximately 5% of patients who are HIV positive.3 Photosensitive eruptions previously described in association with HIV include porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, chronic actinic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, photodistributed dyspigmentation, and lichenoid photodermatitis.7 These HIV-associated photosensitive eruptions have been found to disproportionally affect patients of African and Native American descent.5,7,8 Therefore, a new photodistributed eruption in a patient of African or Native American descent should prompt evaluation of possible underlying HIV infection.

Presenting Sign of HIV Infection

We report a case of photolichenoid dermatitis presenting with loss of pigmentation as a presenting sign of HIV. The patient had no known history of HIV or prior opportunistic infections and was not taking any medications at the time of onset or presentation to clinic. Similar cases of photodistributed depigmentation with lichenoid inflammation on histopathology occurring in patients with HIV have been previously described.4-6,9 In these cases, most patients were of African descent with previously diagnosed advanced HIV and CD4 counts of less than 50 cells/mL3. The additional clinical findings of lichenoid papules and plaques were noted in several of these cases.5,6

Exposure to Photosensitizing Drugs

Photodermatitis in patients with HIV often is attributed to exposure to a photosensitizing drug. Many reported cases are retrospective and identify a temporal association between the onset of photodermatitis following the initiation of a photosensitizing drug. The most commonly implicated drugs have included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin. Other potential offenders may include saquinavir, dapsone, ketoconazole, and efavirenz.3,5 In cases in which temporal association with a new medication could not be identified, the photodermatitis often has been presumed to be due to polypharmacy and the potential synergistic effect of multiple photosensitizing drugs.3,5-8

Advanced HIV

There are several reported cases of photodermatitis occurring in patients who were not exposed to systemic photosensitizers. These patients had advanced HIV, meeting criteria for AIDS with a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mL3. The majority of patients had an even lower CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mL3. Clinical presentations have included photodistributed lichenoid papules and plaques as well as depigmented patches.4,5,8,10

Evaluating HIV as a Risk Factor for Photodermatitis

Discerning the validity of the correlation between photodermatitis and HIV is difficult, as all previously reported cases are case reports and small retrospective case series.

Conclusion

This case represents an uncommon presentation of photolichenoid dermatitis as the presenting sign of HIV infection.10 Although most reported cases of photodermatitis in HIV are attributed to photosensitizing drugs, we propose that HIV may be an independent risk factor for the development of photodermatitis. We recommend consideration of HIV testing in patients who present with photodistributed depigmenting eruptions, even in the absence of a photosensitizing drug, particularly in patients of African and Native American descent.

Photolichenoid dermatitis is an uncommon eruptive dermatitis of variable clinical presentation. It has a histopathologic pattern of lichenoid inflammation and is best characterized as a photoallergic reaction.1 Photolichenoid dermatitis was first described in 1954 in association with the use of quinidine in the treatment of malaria.2 Subsequently, it has been associated with various medications, including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.1,2 Photolichenoid dermatitis has been documented in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with variable clinical presentations. Photolichenoid dermatitis in patients with HIV has been described both with and without an associated photosensitizing systemic agent, suggesting that HIV infection is an independent risk factor for the development of this eruption in patients with HIV.3-6

Case Report

A 62-year-old African man presented for evaluation of asymptomatic hypopigmented and depigmented patches in a photodistributed pattern. The eruption began the preceding summer when he noted a pink patch on the right side of the forehead. It progressed over 2 months to involve the face, ears, neck, and arms. His medical history was negative. The only medication he was taking was hydroxychloroquine, which was prescribed by another dermatologist when the patient first developed the eruption. The patient was unsure of the indication for the medication and admitted to poor compliance. A review of systems was negative. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune disease. A detailed sexual history and illicit drug history were not obtained. Physical examination revealed hypopigmented and depigmented patches, some with overlying erythema and collarettes of fine scale. The patches were photodistributed on the face, conchal bowls, neck, dorsal aspect of the hands, and extensor forearms (Figures 1 and 2). Macules of repigmentation were noted within some of the patches. There also were large hyperpigmented patches with peripheral hypopigmentation on the legs.

A punch biopsy taken from the left posterior neck revealed a patchy bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with lymphocytes present at the dermoepidermal junction and scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes extending into the mid spinous layer (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with photolichenoid dermatitis.

Laboratory workup revealed a normal complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel. Other negative results included antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro antibody, anti-La antibody, QuantiFERON-TB Gold, syphilis IgG antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody. Positive results included hepatitis B antibody, hepatitis C antibody, and HIV-2 antibody. The patient denied overt symptoms suggestive of an immunocompromised status, including fever, chills, weight loss, or diarrhea. Initial treatment included mid-potency topical steroids with continued progression of the eruption. Following histopathologic and laboratory results indicating photolichenoid eruption, treatment with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was resumed. The patient was counseled on the importance of sun protection and was referred to an infectious disease clinic for treatment of HIV. He was ultimately lost to follow-up before further laboratory workup was obtained. Therefore, his CD4+ T-cell count and viral load were not obtained.

Comment

Prevalence of Photosensitive Eruptions

Photodermatitis is an uncommon clinical manifestation of HIV occurring in approximately 5% of patients who are HIV positive.3 Photosensitive eruptions previously described in association with HIV include porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, chronic actinic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, photodistributed dyspigmentation, and lichenoid photodermatitis.7 These HIV-associated photosensitive eruptions have been found to disproportionally affect patients of African and Native American descent.5,7,8 Therefore, a new photodistributed eruption in a patient of African or Native American descent should prompt evaluation of possible underlying HIV infection.

Presenting Sign of HIV Infection

We report a case of photolichenoid dermatitis presenting with loss of pigmentation as a presenting sign of HIV. The patient had no known history of HIV or prior opportunistic infections and was not taking any medications at the time of onset or presentation to clinic. Similar cases of photodistributed depigmentation with lichenoid inflammation on histopathology occurring in patients with HIV have been previously described.4-6,9 In these cases, most patients were of African descent with previously diagnosed advanced HIV and CD4 counts of less than 50 cells/mL3. The additional clinical findings of lichenoid papules and plaques were noted in several of these cases.5,6

Exposure to Photosensitizing Drugs

Photodermatitis in patients with HIV often is attributed to exposure to a photosensitizing drug. Many reported cases are retrospective and identify a temporal association between the onset of photodermatitis following the initiation of a photosensitizing drug. The most commonly implicated drugs have included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin. Other potential offenders may include saquinavir, dapsone, ketoconazole, and efavirenz.3,5 In cases in which temporal association with a new medication could not be identified, the photodermatitis often has been presumed to be due to polypharmacy and the potential synergistic effect of multiple photosensitizing drugs.3,5-8

Advanced HIV

There are several reported cases of photodermatitis occurring in patients who were not exposed to systemic photosensitizers. These patients had advanced HIV, meeting criteria for AIDS with a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mL3. The majority of patients had an even lower CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mL3. Clinical presentations have included photodistributed lichenoid papules and plaques as well as depigmented patches.4,5,8,10

Evaluating HIV as a Risk Factor for Photodermatitis

Discerning the validity of the correlation between photodermatitis and HIV is difficult, as all previously reported cases are case reports and small retrospective case series.

Conclusion

This case represents an uncommon presentation of photolichenoid dermatitis as the presenting sign of HIV infection.10 Although most reported cases of photodermatitis in HIV are attributed to photosensitizing drugs, we propose that HIV may be an independent risk factor for the development of photodermatitis. We recommend consideration of HIV testing in patients who present with photodistributed depigmenting eruptions, even in the absence of a photosensitizing drug, particularly in patients of African and Native American descent.

- Collazo MH, Sanchez JL, Figueroa LD. Defining lichenoid photodermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:239-242.

- Wechsler HL. Dermatitis medicamentosa; a lichen-planus-like eruption due to quinidine. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:741-744.

- Bilu D, Mamelak AJ, Nguyen RH, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characterization of photosensitivity in HIV-positive individuals. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20:175-183.

- Philips RC, Motaparthi K, Krishnan B, et al. HIV photodermatitis presenting with widespread vitiligo-like depigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:6.

- Berger TG, Dhar A. Lichenoid photoeruptions in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:609-613.

- Tran K, Hartman R, Tzu J, et al. Photolichenoid plaques with associated vitiliginous pigmentary changes. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13.

- Gregory N, DeLeo VA. Clinical manifestations of photosensitivity in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:630-633.

- Vin-Christian K, Epstein JH, Maurer TA, et al. Photosensitivity in HIV-infected individuals. J Dermatol. 2000;27:361-369.

- Kigonya C, Lutwama F, Colebunders R. Extensive hypopigmentation after starting antiretroviral treatment in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive African woman. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:102-103.

- Pardo RJ, Kerdel FA. Hypertrophic lichen planus and light sensitivity in an HIV-positive patient. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:642-644.

- Collazo MH, Sanchez JL, Figueroa LD. Defining lichenoid photodermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:239-242.

- Wechsler HL. Dermatitis medicamentosa; a lichen-planus-like eruption due to quinidine. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:741-744.

- Bilu D, Mamelak AJ, Nguyen RH, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characterization of photosensitivity in HIV-positive individuals. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20:175-183.

- Philips RC, Motaparthi K, Krishnan B, et al. HIV photodermatitis presenting with widespread vitiligo-like depigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:6.

- Berger TG, Dhar A. Lichenoid photoeruptions in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:609-613.

- Tran K, Hartman R, Tzu J, et al. Photolichenoid plaques with associated vitiliginous pigmentary changes. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13.

- Gregory N, DeLeo VA. Clinical manifestations of photosensitivity in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:630-633.

- Vin-Christian K, Epstein JH, Maurer TA, et al. Photosensitivity in HIV-infected individuals. J Dermatol. 2000;27:361-369.

- Kigonya C, Lutwama F, Colebunders R. Extensive hypopigmentation after starting antiretroviral treatment in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive African woman. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:102-103.

- Pardo RJ, Kerdel FA. Hypertrophic lichen planus and light sensitivity in an HIV-positive patient. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:642-644.

Practice Points

- There are few reports in the literature of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) presenting as a photolichenoid eruption.

- We report the case of a 62-year-old African man who presented with a new-onset photodistributed eruption and was subsequently diagnosed with HIV.

- This case supports testing for HIV in patients with a similar clinical presentation.

Id Reaction Associated With Red Tattoo Ink

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

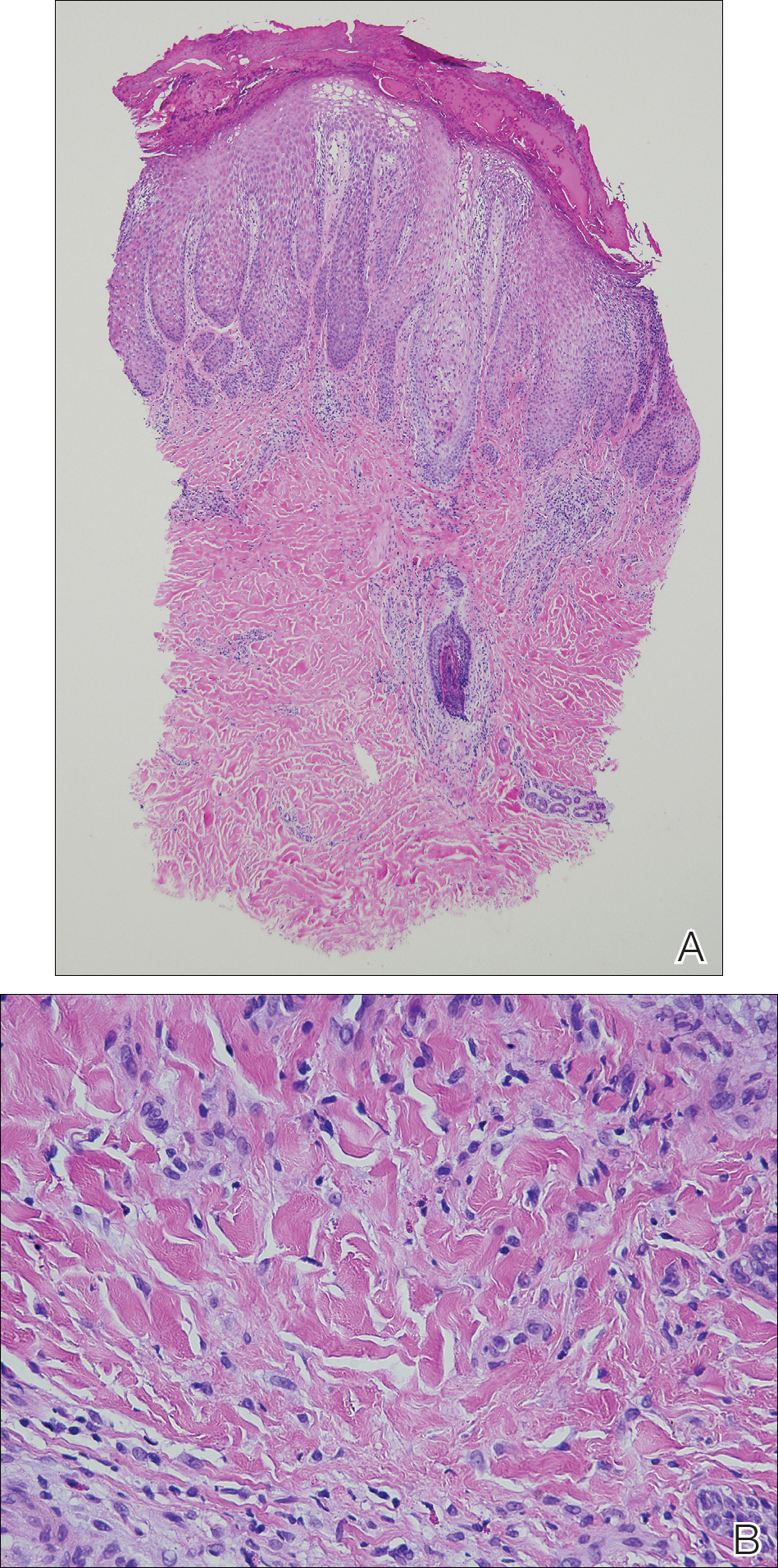

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

Practice Points

- Hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos. Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity.

- Id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization.

- Further investigation of color additives in tattoo pigments is warranted to better elucidate the components responsible for cutaneous allergic reactions associated with tattoo ink.