User login

Scleromyxedema in a Patient With Thyroid Disease: An Atypical Case or a Case for Revised Criteria?

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

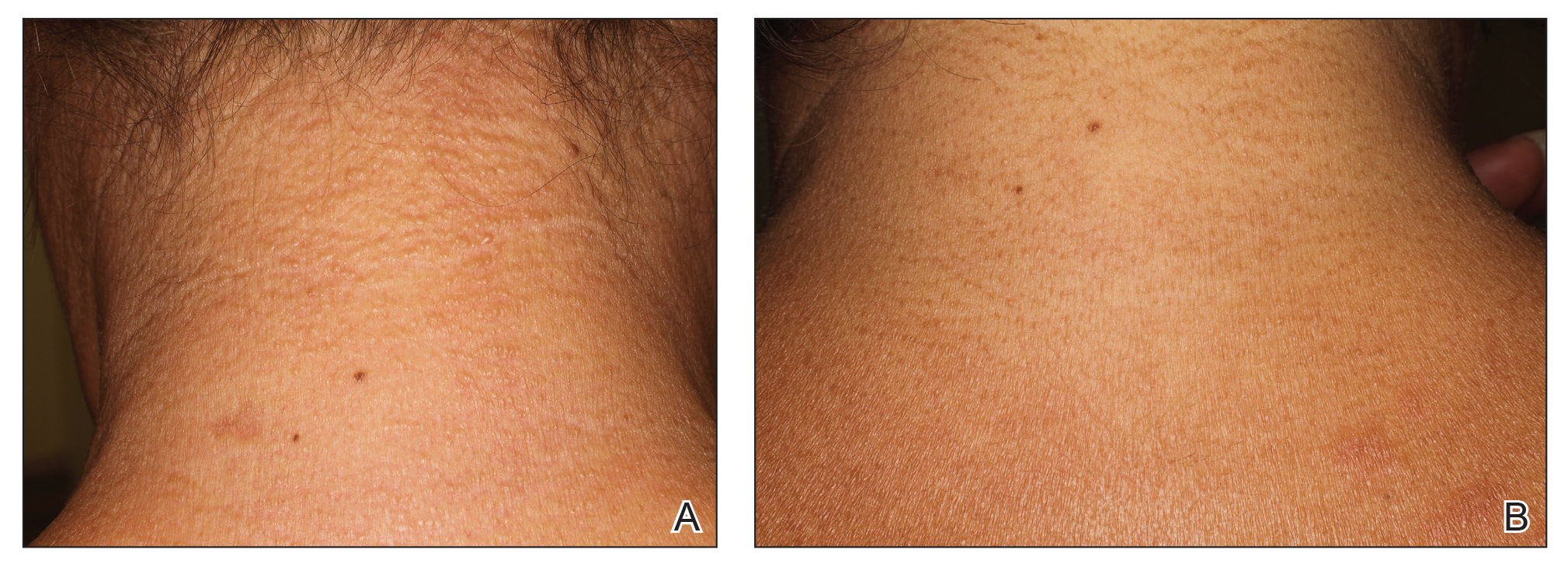

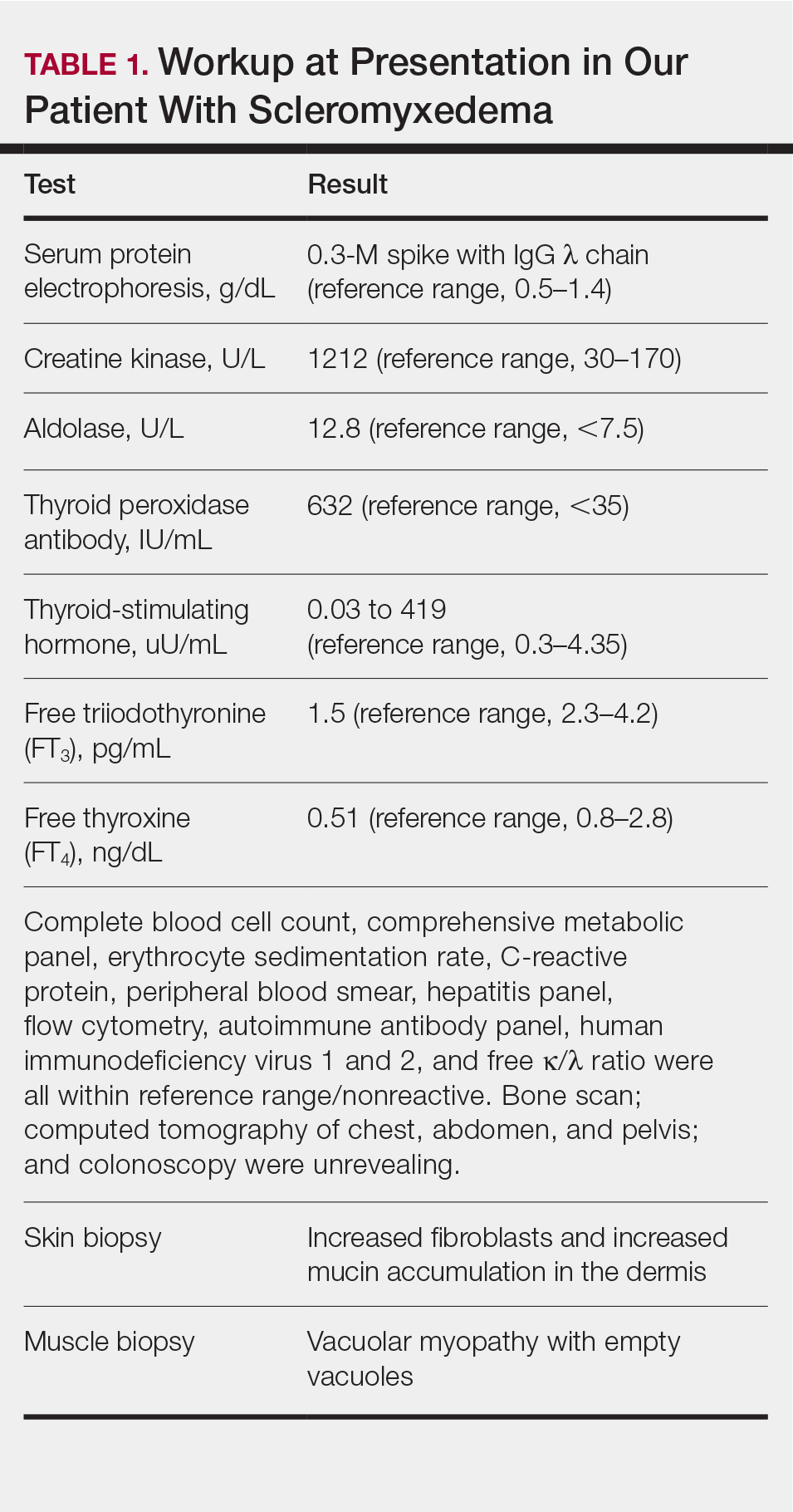

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a generalized papular and sclerodermoid form of lichen myxedematosus (LM), commonly referred to as papular mucinosis. It is a rare progressive disease of unknown etiology with systemic manifestations that cause serious morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic criteria were initially created by Montgomery and Underwood1 in 1953 and revised by Rongioletti and Rebora2 in 2001 as follows: (1) generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption; (2) histologic triad of mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; (3) monoclonal gammopathy; and (4) absence of thyroid disease. There are several reports of LM in association with hypothyroidism, most of which can be characterized as atypical.3-8 We present a case of SM in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis and propose that the presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman presented with a progressive eruption of thickened skin and papules spanning many months. The papules ranged from flesh colored to erythematous and covered more than 80% of the body surface area, most notably involving the face, neck, ears, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs (Figures 1A and 2A). Review of systems was notable for pruritus, muscle pain but no weakness, dysphagia, and constipation. Her medical history included childhood atopic dermatitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis. Hypothyroidism was diagnosed with support of a thyroid ultrasound and thyroid peroxidase antibodies. It was treated with oral levothyroxine for 2 years prior to the skin eruption. Thyroid biopsy was not performed. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels notably fluctuated in the year prior to presentation despite close clinical and laboratory monitoring by an endocrinologist. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Both skin and muscle9 biopsies were consistent with SM (Figure 3) and are summarized in Table 1.

Shortly after presentation to our clinic the patient developed acute concerns of confusion and muscle weakness. She was admitted for further inpatient management due to concern for dermato-neuro syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal decline in neurological status that can progress to coma and death, rather than myxedema coma. On admission, a thyroid function test showed subclinical hypothyroidism with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.35 uU/mL (reference range, 0.3–4.35 uU/mL) and free thyroxine (FT4) level of 1.5 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8–2.8 ng/dL). While hospitalized she was started on intravenous levothyroxine, systemic steroids, and a course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment consisting of 2 g/kg divided over 5 days. On this regimen, her mental status quickly returned to baseline and other symptoms improved, including the skin eruption (Figures 1B and 2B). She has been maintained on lenalidomide 25 mg/d for the first 3 weeks of each month as well as monthly IVIg infusions. Her thyroid levels have persistently fluctuated despite intramuscular levothyroxine dosing, but her skin has remained clear with continued SM-directed therapy.

Comment

Classification

Lichen myxedematosus is differentiated into localized and generalized forms. The former is limited to the skin and lacks monoclonal gammopathy. The latter, also known as SM, is associated with monoclonal gammopathy and systemic symptoms. Atypical LM is an umbrella term for intermediate cases.

Clinical Presentation

Skin manifestations of SM are described as 1- to 3-mm, firm, waxy, dome-shaped papules that commonly affect the hands, forearms, face, neck, trunk, and thighs. The surrounding skin may be reddish brown and edematous with evidence of skin thickening. Extracutaneous manifestations in SM are numerous and unpredictable. Any organ system can be involved, but gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular complications are most common.10 A comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation is necessary based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings.

Management

Many treatments have been proposed for SM in case reports and case series. Prior treatments have had little success. Most recently, in one of the largest case series on SM, Rongioletti et al10 demonstrated IVIg to be a safe and effective treatment modality.

Differential Diagnosis

An important differential diagnosis is generalized myxedema, which is seen in long-standing hypothyroidism and may present with cutaneous mucinosis and systemic symptoms that resemble SM. Hypothyroid myxedema is associated with a widespread slowing of the body’s metabolic processes and deposition of mucin in various organs, including the skin, creating a generalized nonpitting edema. Classic clinical signs include macroglossia, periorbital puffiness, thick lips, and acral swelling. The skin tends to be cold, dry, and pale. Hair is characterized as being coarse, dry, and brittle with diffuse partial alopecia. Histologically, there is hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging and diffuse mucin and edema splaying between collagen fibers spanning the entire dermis.11 In contradistinction with SM, there is no fibroblast proliferation. The treatment is thyroid replacement therapy. Hyperthyroidism has distinct clinical and histologic changes. Clinically, there is moist and smooth skin with soft, fine, and sometimes alopecic hair. Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is further characterized by Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxedema, or pink to brown, raised, firm, indurated, asymmetric plaques most commonly affecting the shins. Histologically there is increased mucin in the lower to mid dermis without fibroblast proliferation. The epidermis can be hyperkeratotic, which will clinically correlate with verrucous lesions.12

Hypothyroid encephalopathy is a rare disorder that can cause a change in mental status. It is a steroid-responsive autoimmune process characterized by encephalopathy that is associated with cognitive impairment and psychiatric features. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in women with a history of autoimmune disease, especially antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, a negative infectious workup, and encephalitis with behavioral changes. Although typically highly responsive to systemic steroids, IVIg also has shown efficacy.13

Presence of Thyroid Disease

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scleromyxedema and lichen myxedematosus, there are 7 cases in the literature that potentially describe LM associated with hypothyroidism (Table 2).3-8 The majority of these cases lack monoclonal gammopathy; improved with thyroid replacement therapy; or had severely atypical clinical presentations, rendering them cases of atypical LM or atypical thyroid dermopathy.3-6 Macnab and Kenny7 presented a case of subclinical hypothyroidism with a generalized papular eruption, monoclonal gammopathy, and consistent histologic changes that responded to IVIg therapy. These findings are suggestive of SM, but limited to the current diagnostic criteria, the patient was diagnosed with atypical LM.7 Shenoy et al8 described 2 cases of LM with hypothyroidism. One patient had biopsy-proven SM that was responsive to IVIg as well as Hashimoto thyroiditis with delayed onset of monoclonal gammopathy. The second patient had a medical history of hypothyroidism and Hodgkin lymphoma with active rheumatoid arthritis and biopsy-proven LM that was responsive to systemic steroids.8

Current literature states that thyroid disorder precludes the diagnosis of SM. However, historic literature would suggest otherwise. Because of inconsistent reports and theories regarding the pathogenesis of various sclerodermoid and mucin deposition diseases, in 1953 Montgomery and Underwood1 sought to differentiate LM from scleroderma and generalized myxedema. They stressed clinical appearance and proposed diagnostic criteria for LM as generalized papular mucinosis in which “[n]o relation to disturbance of the thyroid or other endocrine glands is apparent,” whereas generalized myxedema was defined as a “[t]rue cutaneous myxedema, with diffuse edema and the usual commonly recognized changes” in patients with endocrine abnormalities.1 With this classification, the authors made a clear distinction between mucinosis caused by thyroid abnormalities and LM, which is not caused by a thyroid disorder. Since this original description was published, associations with monoclonal gammopathy and fibroblast proliferation have been made, ultimately culminating into the current 2001 criteria that incorporate the absence of thyroid disease.2

Conclusion

We believe our case is consistent with the classification initially proposed by Montgomery and Underwood1 and is strengthened with the more recent associations with monoclonal gammopathy and specific histopathologic findings. Although there is no definitive way to rule out myxedema coma or Hashimoto encephalopathy to describe our patient’s transient neurologic decline, her clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, and biopsy results all supported the diagnosis of SM. Furthermore, her response to SM-directed therapy, despite fluctuating thyroid function test results, also supported the diagnosis. In the setting of cutaneous mucinosis with conflicting findings for hypothyroid myxedema, LM should be ruled out. Given the features presented in this report and others, diagnostic criteria should allow for SM and thyroid dysfunction to be concurrent diagnoses. Most importantly, we believe it is essential to identify and diagnose SM in a timely manner to facilitate SM-directed therapy, namely IVIg, to potentially minimize the disease’s notable morbidity and mortality.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

- Montgomery H, Underwood LJ. Lichen myxedematosus; differentiation from cutaneous myxedemas or mucoid states. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:213-236.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Archibald GC, Calvert HT. Hypothyroidsm and lichen myxedematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:684.

- Schaeffer D, Bruce S, Rosen T. Cutaneous mucinosis associated with thyroid dysfunction. Cutis. 1983;11:449-456.

- Martin-Ezquerra G, Sanchez-Regaña M, Massana-Gil J, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with subclinical hypothyroidism: improvement with thyroxine therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1340-1341.

- Volpato MB, Jaime TJ, Proença MP, et al. Papular mucinosis associated with hypothyroidism. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:89-92.

- Macnab M, Kenny P. Successful intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of atypical lichen myxedematosus associated with hypothyroidism and central nervous system. involvement: case report and discussion of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:69-73.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Helfrich DJ, Walker ER, Martinez AJ, et al. Scleromyxedema myopathy: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1437-1441.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Jackson EM, English JC 3rd. Diffuse cutaneous mucinoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:493-501.

- Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Thyroid disease and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:473-481.

- Zhou JY, Xu B, Lopes J, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy: literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135:285-290.

Practice Points

- Scleromyxedema (SM) is progressive disease of unknown etiology with unpredictable behavior.

- Systemic manifestations associated with SM can cause serious morbidity and mortality.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin is the most effective treatment modality in SM.

- The presence of thyroid disease should not preclude the diagnosis of SM.

Atrophodermalike Guttate Morphea

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

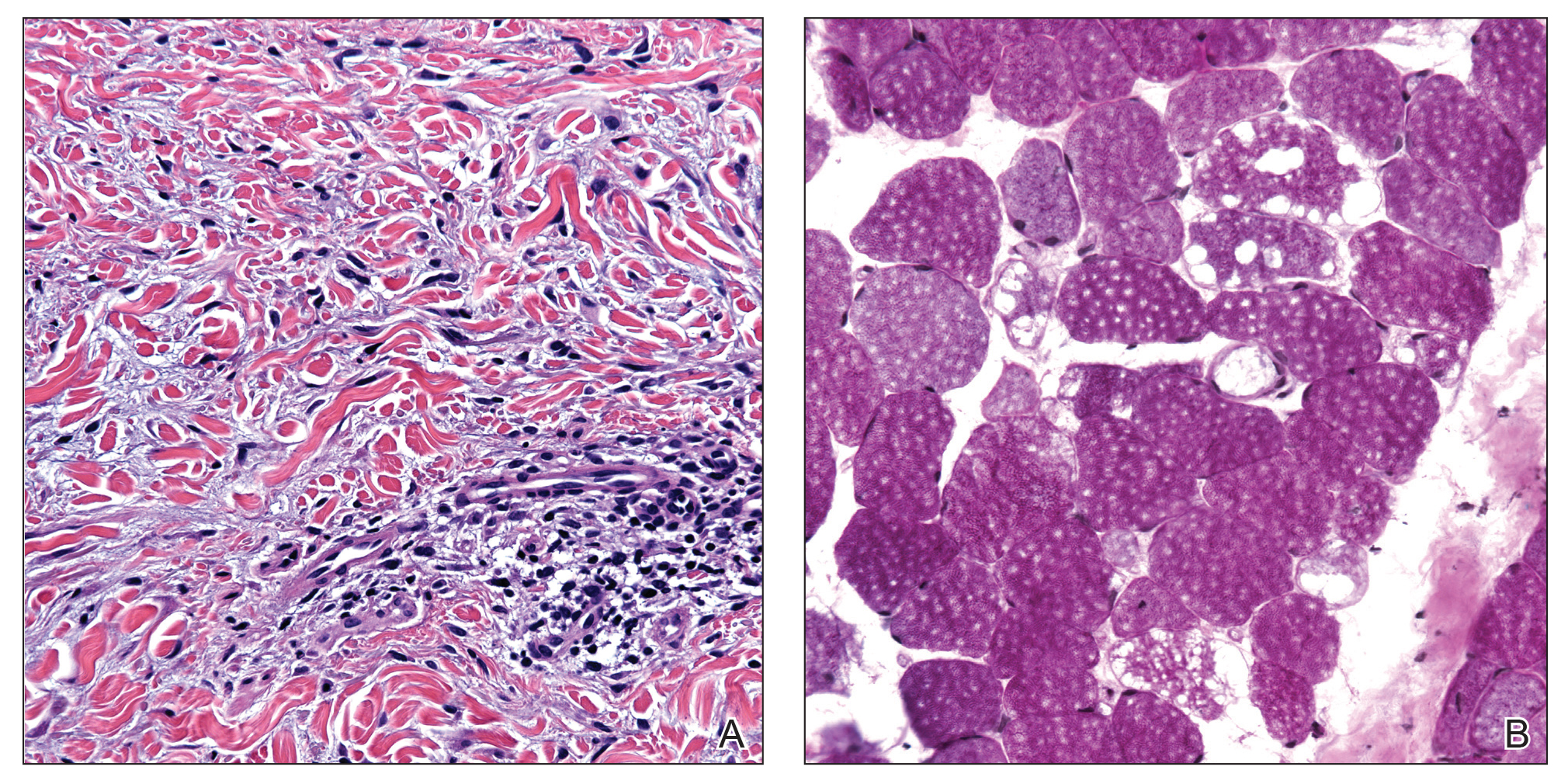

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

Practice Points

- Atrophodermalike guttate morphea is a potentially underreported or undescribed entity consisting of a combination of clinicopathologic features.

- Widespread hypopigmented macules on the trunk and extremities marked by thinned collagen, fibroplasia, and altered fragmented elastin in the papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis are the key features.

- Atrophoderma, morphea, and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus should be ruled out during clinical workup.