User login

Two Techniques to Avoid Cyst Spray During Excision

Practice Gap

Epidermoid cysts are asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile, subcutaneous masses that elevate the skin. Also known as epidermal, keratin, or infundibular cysts, epidermoid cysts are caused by proliferation of surface epidermoid cells within the dermis and can arise anywhere on the body, most commonly on the face, neck, and trunk.1 Cutaneous cysts often contain fluid or semifluid contents and can be aesthetically displeasing or cause mild pain, prompting patients to seek removal. Definitive treatment of epidermoid cysts is complete surgical removal,2 which can be performed in office in a sterile or clean manner by either dermatologists or primary care providers.

Prior to incision, a local anesthetic—commonly lidocaine with epinephrine—is injected in the region surrounding the cyst sac so as not to rupture the cyst wall. Maintaining the cyst wall throughout the procedure ensures total cyst removal and minimizes the risk for recurrence. However, it often is difficult to approximate the cyst border because it cannot be visualized prior to incision.

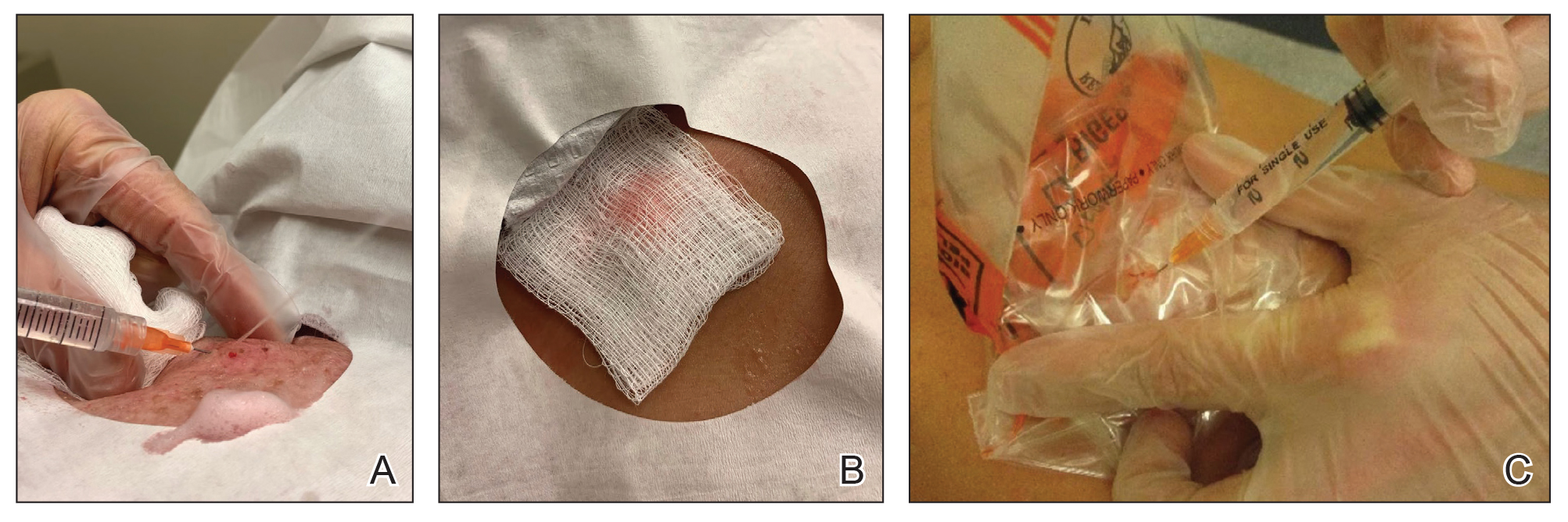

Throughout the duration of the procedure, cyst contents may suddenly spray out of the area and pose a risk to providers and their staff (Figure, A). Even with careful application around the periphery, either puncture or pericystic anesthesia between the cyst wall and the dermis can lead to splatter. Larger and wider peripheral anesthesia may not be possible given a shortage of lidocaine and a desire to minimize injection. Even with meticulous use of personal protective equipment in cutaneous surgery, infectious organisms found in ruptured cysts and abscesses may spray the surgical field.3 Therefore, it is in our best interest to minimize the trajectory of cyst spray contents.

The Tools

We have employed 2 simple techniques using equipment normally found on a standard surgical tray for easy safe injection of cysts. Supplies needed include 4×4-inch gauze pads, alcohol and chlorhexidine, a marker, all instruments necessary for cyst excision, and a small clear biohazard bag.

The Technique

Prior to covering the cyst, care is taken to locate the cyst opening. At times, a comedo or punctum can be seen overlying the cyst bulge. We mark the lumen and cyst opening with a surgical marker. If the pore is not easily identified, we draw an 8-mm circle around the mound of the cyst.

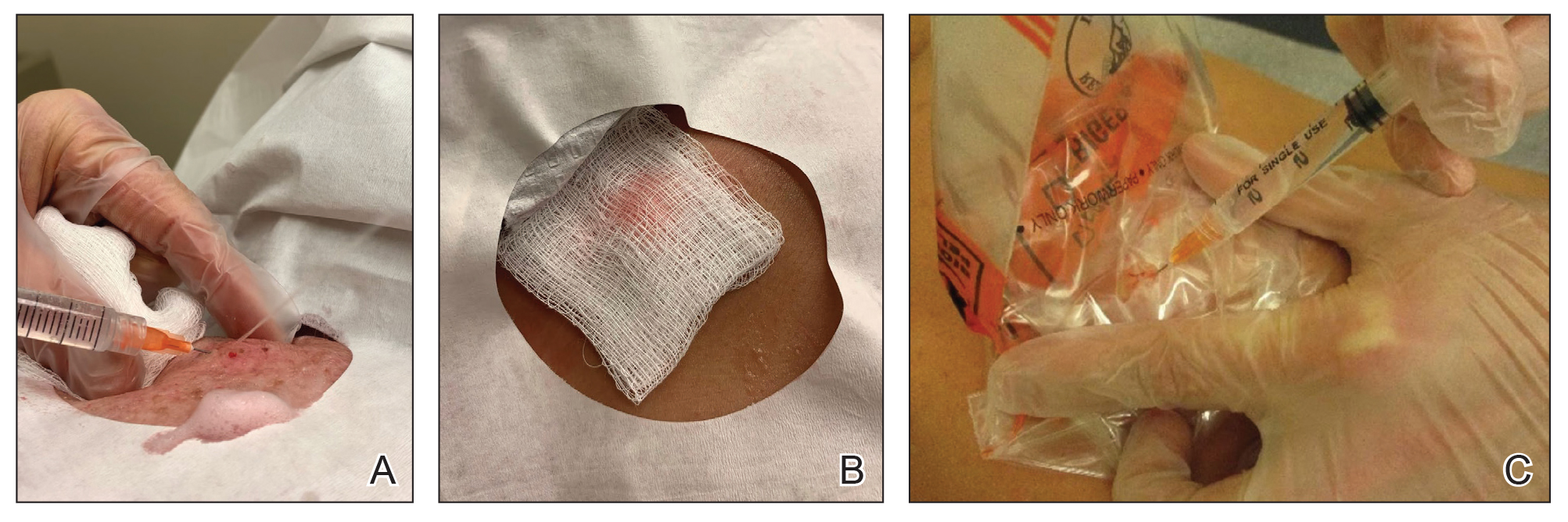

One option is to apply a gauze pad over the cyst to allow for stabilization of the surgical field and blanket the area from splatter (Figure, B). Then we cover the cyst using antiseptic-soaked gauze as a protective barrier to avoid potentially contaminated spray. This tool can be constructed from a 4×4-inch gauze pad with the addition of alcohol and chlorhexidine. When the cyst is covered, the surgeon can inject the lesion and surrounding tissue without biohazard splatter.

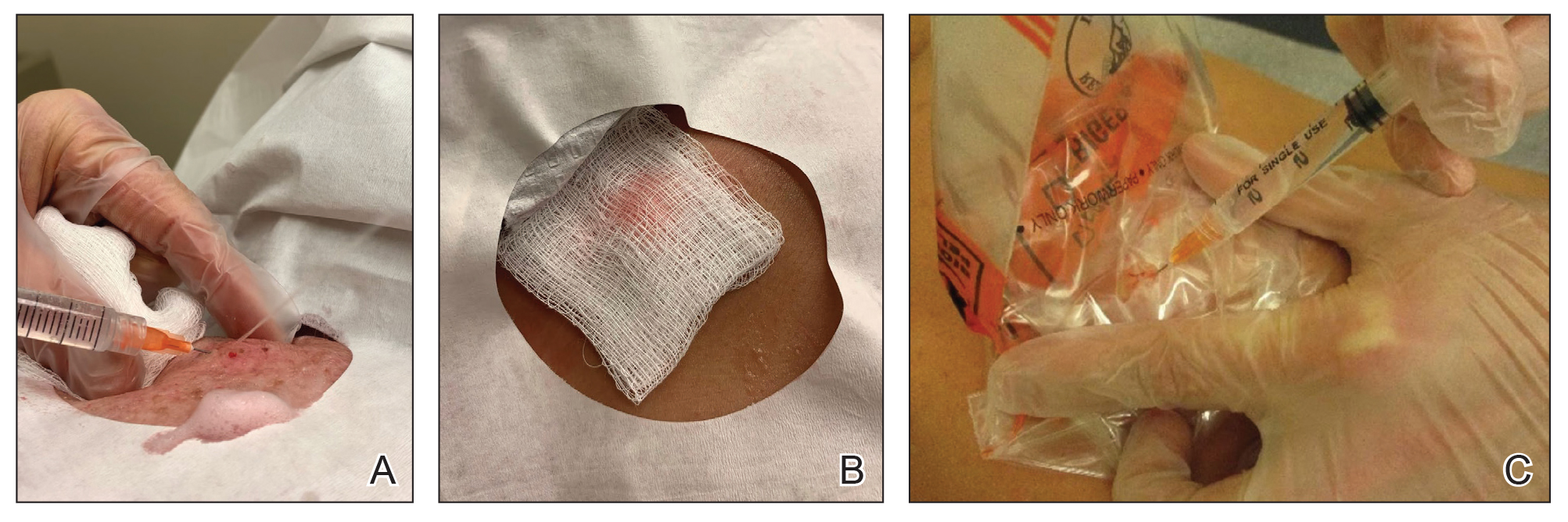

Another method is to cover the cyst with a small clear biohazard bag (Figure, C). When injecting anesthetic through the bag, the spray is captured by the bag and does not reach the surgeon or staff. This method is potentially more effective given that the cyst can still be visualized fully for more accurate injection.

Practice Implications

Outpatient surgical excision is a common effective procedure for epidermoid cysts. However, it is not uncommon for cyst contents to spray during the injection of anesthetic, posing a nuisance to the surgeon, health care staff, and patient. The technique of covering the lesion with antiseptic-soaked gauze or a small clear biohazard bag prevents cyst contents from spraying and reduces risk for contamination. In addition to these protective benefits, the use of readily available items replaces the need to order a splatter control shield.

Limitations—Although we seldom see spray using our technique, covering the cyst with gauze may disguise the region of interest and interfere with accurate incision. Marking the lesion prior to anesthesia administration or using a clear biohazard bag minimizes difficulty visualizing the cyst opening.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Epidermoid cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499974

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June3, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532310/

- Kuniyuki S, Yoshida Y, Maekawa N, et al. Bacteriological study of epidermal cysts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;88:23-25. doi:10.2340/00015555-0348

Practice Gap

Epidermoid cysts are asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile, subcutaneous masses that elevate the skin. Also known as epidermal, keratin, or infundibular cysts, epidermoid cysts are caused by proliferation of surface epidermoid cells within the dermis and can arise anywhere on the body, most commonly on the face, neck, and trunk.1 Cutaneous cysts often contain fluid or semifluid contents and can be aesthetically displeasing or cause mild pain, prompting patients to seek removal. Definitive treatment of epidermoid cysts is complete surgical removal,2 which can be performed in office in a sterile or clean manner by either dermatologists or primary care providers.

Prior to incision, a local anesthetic—commonly lidocaine with epinephrine—is injected in the region surrounding the cyst sac so as not to rupture the cyst wall. Maintaining the cyst wall throughout the procedure ensures total cyst removal and minimizes the risk for recurrence. However, it often is difficult to approximate the cyst border because it cannot be visualized prior to incision.

Throughout the duration of the procedure, cyst contents may suddenly spray out of the area and pose a risk to providers and their staff (Figure, A). Even with careful application around the periphery, either puncture or pericystic anesthesia between the cyst wall and the dermis can lead to splatter. Larger and wider peripheral anesthesia may not be possible given a shortage of lidocaine and a desire to minimize injection. Even with meticulous use of personal protective equipment in cutaneous surgery, infectious organisms found in ruptured cysts and abscesses may spray the surgical field.3 Therefore, it is in our best interest to minimize the trajectory of cyst spray contents.

The Tools

We have employed 2 simple techniques using equipment normally found on a standard surgical tray for easy safe injection of cysts. Supplies needed include 4×4-inch gauze pads, alcohol and chlorhexidine, a marker, all instruments necessary for cyst excision, and a small clear biohazard bag.

The Technique

Prior to covering the cyst, care is taken to locate the cyst opening. At times, a comedo or punctum can be seen overlying the cyst bulge. We mark the lumen and cyst opening with a surgical marker. If the pore is not easily identified, we draw an 8-mm circle around the mound of the cyst.

One option is to apply a gauze pad over the cyst to allow for stabilization of the surgical field and blanket the area from splatter (Figure, B). Then we cover the cyst using antiseptic-soaked gauze as a protective barrier to avoid potentially contaminated spray. This tool can be constructed from a 4×4-inch gauze pad with the addition of alcohol and chlorhexidine. When the cyst is covered, the surgeon can inject the lesion and surrounding tissue without biohazard splatter.

Another method is to cover the cyst with a small clear biohazard bag (Figure, C). When injecting anesthetic through the bag, the spray is captured by the bag and does not reach the surgeon or staff. This method is potentially more effective given that the cyst can still be visualized fully for more accurate injection.

Practice Implications

Outpatient surgical excision is a common effective procedure for epidermoid cysts. However, it is not uncommon for cyst contents to spray during the injection of anesthetic, posing a nuisance to the surgeon, health care staff, and patient. The technique of covering the lesion with antiseptic-soaked gauze or a small clear biohazard bag prevents cyst contents from spraying and reduces risk for contamination. In addition to these protective benefits, the use of readily available items replaces the need to order a splatter control shield.

Limitations—Although we seldom see spray using our technique, covering the cyst with gauze may disguise the region of interest and interfere with accurate incision. Marking the lesion prior to anesthesia administration or using a clear biohazard bag minimizes difficulty visualizing the cyst opening.

Practice Gap

Epidermoid cysts are asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile, subcutaneous masses that elevate the skin. Also known as epidermal, keratin, or infundibular cysts, epidermoid cysts are caused by proliferation of surface epidermoid cells within the dermis and can arise anywhere on the body, most commonly on the face, neck, and trunk.1 Cutaneous cysts often contain fluid or semifluid contents and can be aesthetically displeasing or cause mild pain, prompting patients to seek removal. Definitive treatment of epidermoid cysts is complete surgical removal,2 which can be performed in office in a sterile or clean manner by either dermatologists or primary care providers.

Prior to incision, a local anesthetic—commonly lidocaine with epinephrine—is injected in the region surrounding the cyst sac so as not to rupture the cyst wall. Maintaining the cyst wall throughout the procedure ensures total cyst removal and minimizes the risk for recurrence. However, it often is difficult to approximate the cyst border because it cannot be visualized prior to incision.

Throughout the duration of the procedure, cyst contents may suddenly spray out of the area and pose a risk to providers and their staff (Figure, A). Even with careful application around the periphery, either puncture or pericystic anesthesia between the cyst wall and the dermis can lead to splatter. Larger and wider peripheral anesthesia may not be possible given a shortage of lidocaine and a desire to minimize injection. Even with meticulous use of personal protective equipment in cutaneous surgery, infectious organisms found in ruptured cysts and abscesses may spray the surgical field.3 Therefore, it is in our best interest to minimize the trajectory of cyst spray contents.

The Tools

We have employed 2 simple techniques using equipment normally found on a standard surgical tray for easy safe injection of cysts. Supplies needed include 4×4-inch gauze pads, alcohol and chlorhexidine, a marker, all instruments necessary for cyst excision, and a small clear biohazard bag.

The Technique

Prior to covering the cyst, care is taken to locate the cyst opening. At times, a comedo or punctum can be seen overlying the cyst bulge. We mark the lumen and cyst opening with a surgical marker. If the pore is not easily identified, we draw an 8-mm circle around the mound of the cyst.

One option is to apply a gauze pad over the cyst to allow for stabilization of the surgical field and blanket the area from splatter (Figure, B). Then we cover the cyst using antiseptic-soaked gauze as a protective barrier to avoid potentially contaminated spray. This tool can be constructed from a 4×4-inch gauze pad with the addition of alcohol and chlorhexidine. When the cyst is covered, the surgeon can inject the lesion and surrounding tissue without biohazard splatter.

Another method is to cover the cyst with a small clear biohazard bag (Figure, C). When injecting anesthetic through the bag, the spray is captured by the bag and does not reach the surgeon or staff. This method is potentially more effective given that the cyst can still be visualized fully for more accurate injection.

Practice Implications

Outpatient surgical excision is a common effective procedure for epidermoid cysts. However, it is not uncommon for cyst contents to spray during the injection of anesthetic, posing a nuisance to the surgeon, health care staff, and patient. The technique of covering the lesion with antiseptic-soaked gauze or a small clear biohazard bag prevents cyst contents from spraying and reduces risk for contamination. In addition to these protective benefits, the use of readily available items replaces the need to order a splatter control shield.

Limitations—Although we seldom see spray using our technique, covering the cyst with gauze may disguise the region of interest and interfere with accurate incision. Marking the lesion prior to anesthesia administration or using a clear biohazard bag minimizes difficulty visualizing the cyst opening.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Epidermoid cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499974

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June3, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532310/

- Kuniyuki S, Yoshida Y, Maekawa N, et al. Bacteriological study of epidermal cysts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;88:23-25. doi:10.2340/00015555-0348

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Epidermoid cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499974

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June3, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532310/

- Kuniyuki S, Yoshida Y, Maekawa N, et al. Bacteriological study of epidermal cysts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;88:23-25. doi:10.2340/00015555-0348

Annular Plaques Overlying Hyperpigmented Telangiectatic Patches on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma

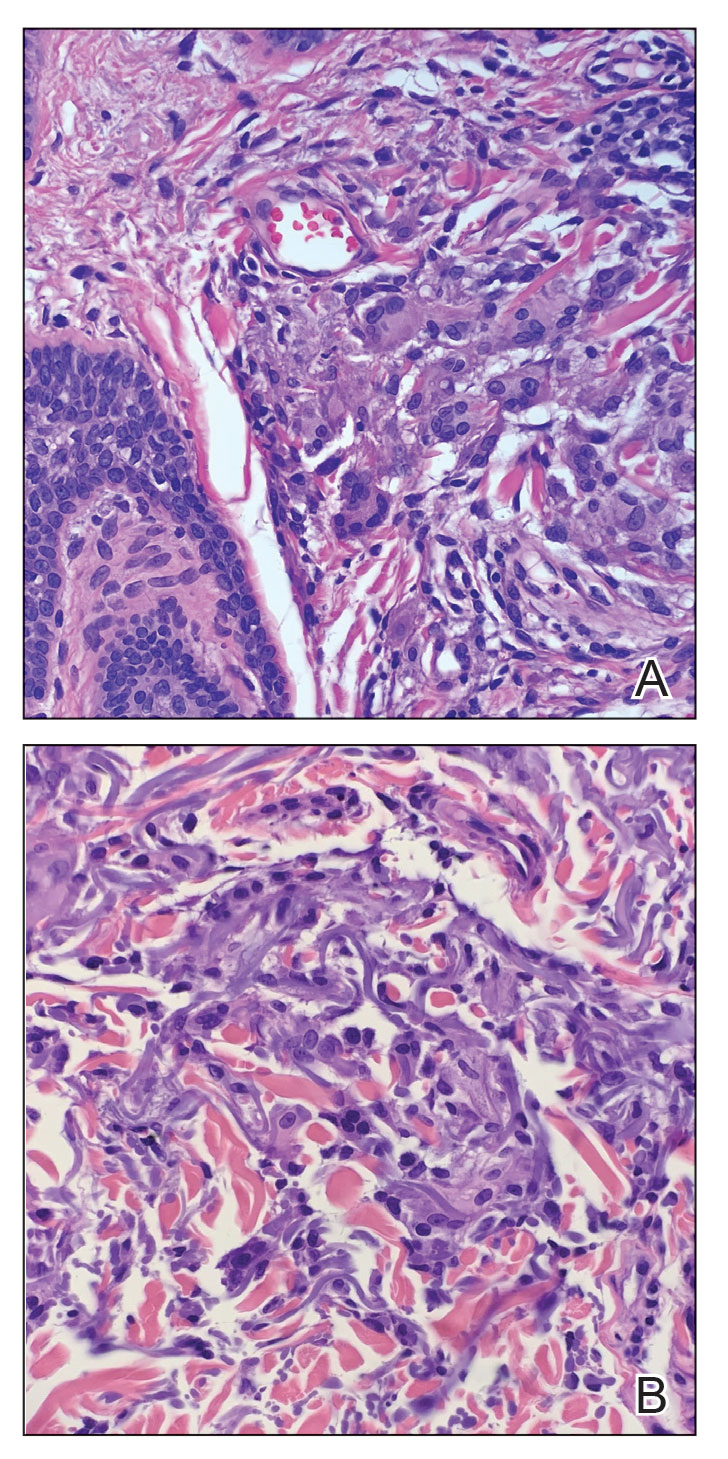

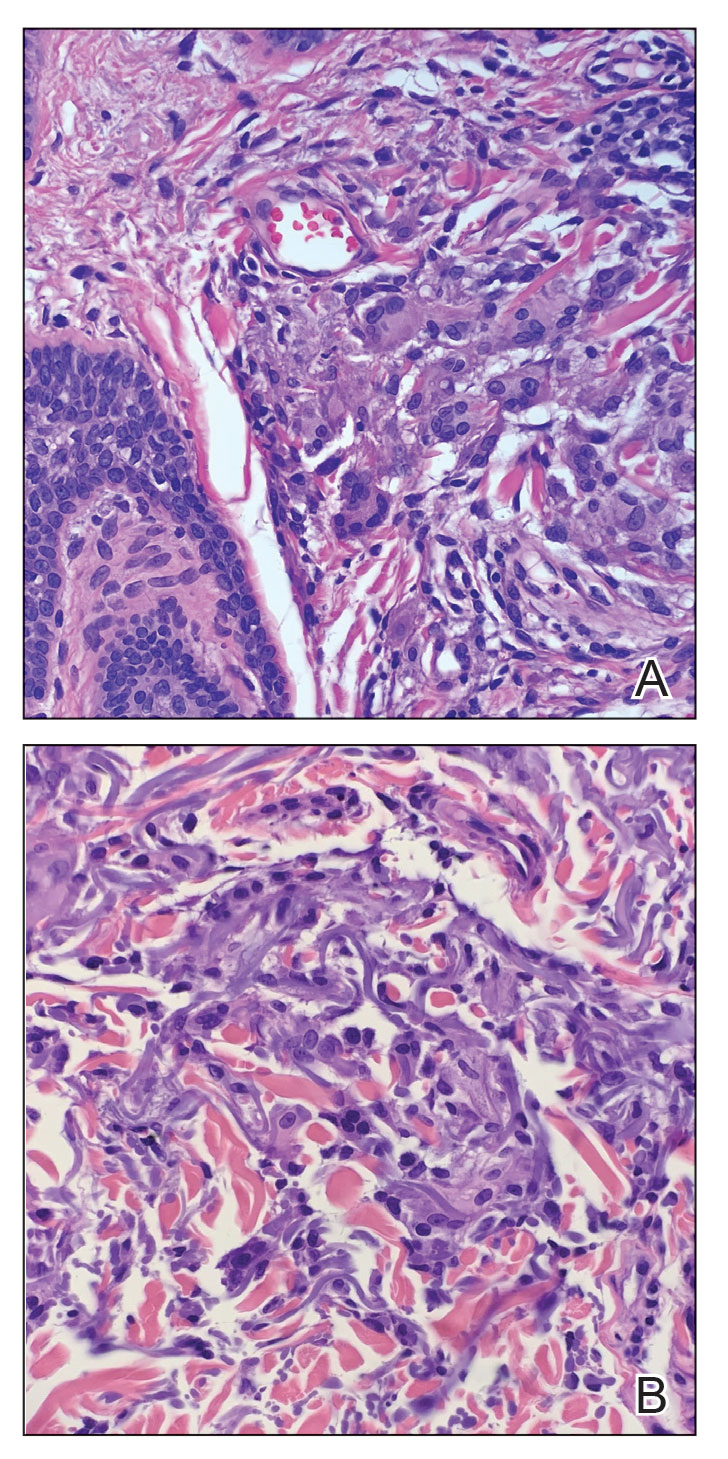

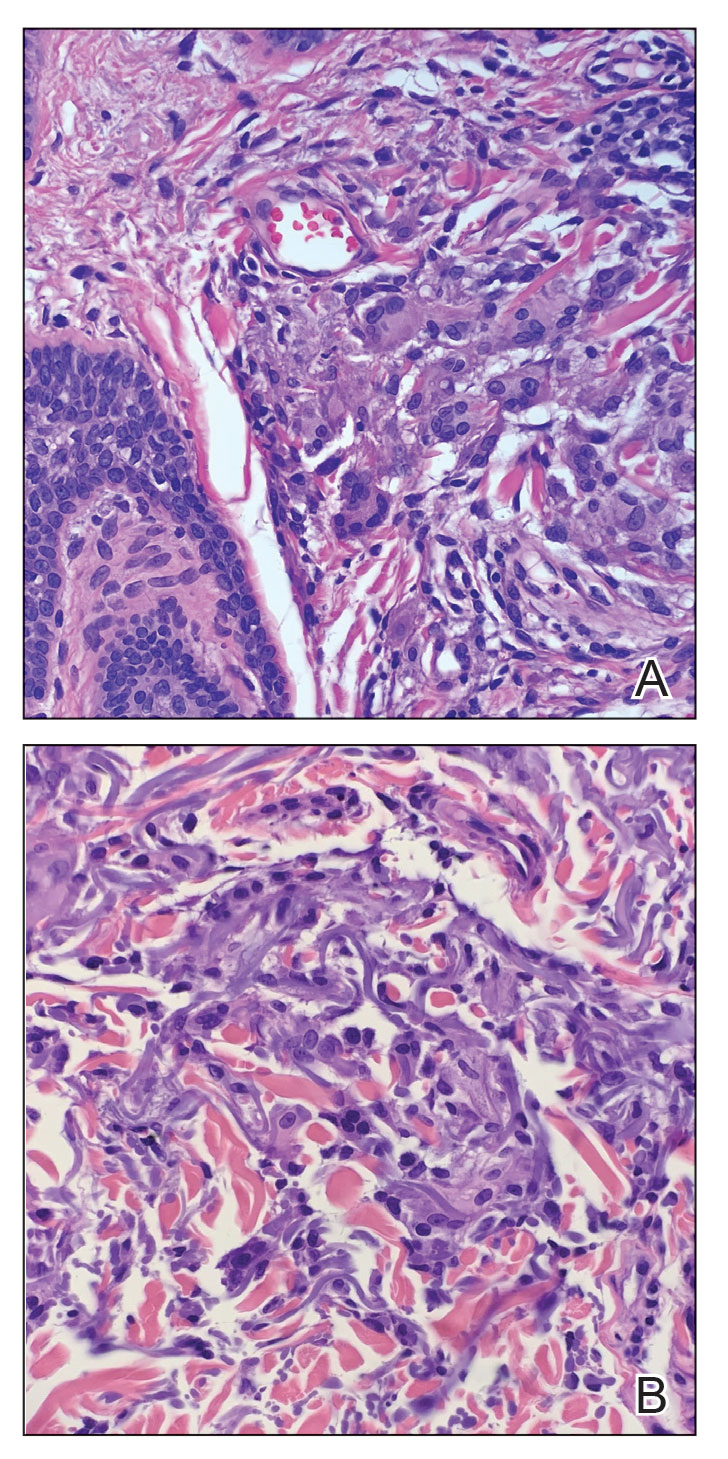

Histologic examination of the shave biopsies showed a granulomatous infiltrate of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, with several also containing fragments of basophilic elastic fibers (elastophagocytosis)(Figure). Additionally, the granulomas revealed no signs of necrosis, making an infectious source unlikely, and examination under polarized light was negative for foreign material. These clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic for annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG).

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder that classically presents on sun-exposed skin as annular plaques with elevated borders and atrophic centers.1-4 Histologically, AEGCG is characterized by diffuse granulomatous infiltrates composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes in the dermis, along with phagocytosis of elastic fibers by multinucleated giant cells.5 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of AEGCG remains unknown.6

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma commonly affects females aged 35 to 75 years; however, cases have been reported in the male and pediatric patient populations.1,2 Documented cases are known to last from 1 month to 10 years.7,8 Although the mechanisms underlying the development of AEGCG remain to be elucidated, studies have determined that the skin disorder is associated with sarcoidosis, molluscum contagiosum, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9 Diabetes mellitus is the most common comorbidity associated with AEGCG, and it is theorized that diabetes contributes to the increased incidence of AEGCG in this population by inducing damage to elastic fibers in the skin.10 One study that examined 50 cases of AEGCG found that 38 patients had serum glucose levels evaluated, with 8 cases being subsequently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 6 cases with apparent impaired glucose tolerance, indicating that 37% of the sample population with AEGCG who were evaluated for metabolic disease were found to have definitive or latent type 2 diabetes mellitus.11 Although AEGCG is a rare disorder, a substantial number of patients diagnosed with AEGCG also have diabetes mellitus, making it important to consider screening all patients with AEGCG for diabetes given the ease and widely available resources to check glucose levels.

Actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, atypical facial necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma multiforme, secondary syphilis, tinea corporis, and erythema annulare centrifugum most commonly are included in the differential diagnosis with AEGCG; histopathology is the key determinant in discerning between these conditions.12 Our patient presented with typical annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches. With known type 2 diabetes mellitus and the clinical findings, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, and AEGCG remained high on the differential.

No standard of care exists for AEGCG due to its rare nature and tendency to spontaneously resolve. The most common first-line treatment includes topical and intralesional steroids, topical pimecrolimus, and the use of sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. UV radiation, specifically UVA, has been determined to be a causal factor for AEGCG by changing the antigenicity of elastic fibers and producing an immune response in individuals with fair skin.13 Further, resistant cases of AEGCG successfully have been treated with cyclosporine, systemic steroids, antimalarials, dapsone, and oral retinoids.14,15 Some studies reported partial regression or full resolution with topical tretinoin; adalimumab; clobetasol ointment; or a combination of corticosteroids, antihistamines, and hydroxychloroquine.2 Only 1 case series using sulfasalazine reported worsening symptoms after treatment initiation.16 Our patient deferred systemic medications and was treated with 4 weeks of topical triamcinolone followed by 4 weeks of topical tacrolimus with minimal improvement. At the time of diagnosis, our patient also was encouraged to use sun-protective measures. At 6-month follow-up, the lesions remained stable, and the decision was made to continue with photoprotection.

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456. doi:10.7759/cureus.11456

- Chen WT, Hsiao PF, Wu YH. Spectrum and clinical variants of giant cell elastolytic granuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:738-745. doi:10.1111/ijd.13502

- Raposo I, Mota F, Lobo I, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a “visible” diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9rq3j927

- Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132

- Hassan R, Arunprasath P, Padmavathy L, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:107-110. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178087

- Kaya Erdog˘ an H, Arık D, Acer E, et al. Clinicopathological features of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma patients. Turkish J Dermatol. 2018;12:85-89.

- Can B, Kavala M, Türkog˘ lu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxychloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2011.04941.x

- Arora S, Malik A, Patil C, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a report of 10 cases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(suppl 1):S17-S20. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.171055

- Doulaveri G, Tsagroni E, Giannadaki M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in a 70-year-old woman. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:290-291. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01767.x

- Marmon S, O’Reilly KE, Fischer M, et al. Papular variant of annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:23.

- Aso Y, Izaki S, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2011.04094.x

- Liu X, Zhang W, Liu Y, et al. A case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with syphilis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018; 10:158-161. doi:10.1159/000489910

- Gutiérrez-González E, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Elastolytic actinic giant cell granuloma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:331-341. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.002

- de Oliveira FL, de Barros Silveira LK, Machado Ade M, et al. Hybrid clinical and histopathological pattern in annular lesions: an overlap between annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma and granuloma annulare? Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:102915. doi:10.1155/2012/102915

- Wagenseller A, Larocca C, Vashi NA. Treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with topical tretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:699-700.

- Yang YW, Lehrer MD, Mangold AR, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and related granulomatous diseases with sulphasalazine: a series of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:211-215. doi:10.1111/jdv.16356

The Diagnosis: Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma

Histologic examination of the shave biopsies showed a granulomatous infiltrate of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, with several also containing fragments of basophilic elastic fibers (elastophagocytosis)(Figure). Additionally, the granulomas revealed no signs of necrosis, making an infectious source unlikely, and examination under polarized light was negative for foreign material. These clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic for annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG).

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder that classically presents on sun-exposed skin as annular plaques with elevated borders and atrophic centers.1-4 Histologically, AEGCG is characterized by diffuse granulomatous infiltrates composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes in the dermis, along with phagocytosis of elastic fibers by multinucleated giant cells.5 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of AEGCG remains unknown.6

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma commonly affects females aged 35 to 75 years; however, cases have been reported in the male and pediatric patient populations.1,2 Documented cases are known to last from 1 month to 10 years.7,8 Although the mechanisms underlying the development of AEGCG remain to be elucidated, studies have determined that the skin disorder is associated with sarcoidosis, molluscum contagiosum, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9 Diabetes mellitus is the most common comorbidity associated with AEGCG, and it is theorized that diabetes contributes to the increased incidence of AEGCG in this population by inducing damage to elastic fibers in the skin.10 One study that examined 50 cases of AEGCG found that 38 patients had serum glucose levels evaluated, with 8 cases being subsequently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 6 cases with apparent impaired glucose tolerance, indicating that 37% of the sample population with AEGCG who were evaluated for metabolic disease were found to have definitive or latent type 2 diabetes mellitus.11 Although AEGCG is a rare disorder, a substantial number of patients diagnosed with AEGCG also have diabetes mellitus, making it important to consider screening all patients with AEGCG for diabetes given the ease and widely available resources to check glucose levels.

Actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, atypical facial necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma multiforme, secondary syphilis, tinea corporis, and erythema annulare centrifugum most commonly are included in the differential diagnosis with AEGCG; histopathology is the key determinant in discerning between these conditions.12 Our patient presented with typical annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches. With known type 2 diabetes mellitus and the clinical findings, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, and AEGCG remained high on the differential.

No standard of care exists for AEGCG due to its rare nature and tendency to spontaneously resolve. The most common first-line treatment includes topical and intralesional steroids, topical pimecrolimus, and the use of sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. UV radiation, specifically UVA, has been determined to be a causal factor for AEGCG by changing the antigenicity of elastic fibers and producing an immune response in individuals with fair skin.13 Further, resistant cases of AEGCG successfully have been treated with cyclosporine, systemic steroids, antimalarials, dapsone, and oral retinoids.14,15 Some studies reported partial regression or full resolution with topical tretinoin; adalimumab; clobetasol ointment; or a combination of corticosteroids, antihistamines, and hydroxychloroquine.2 Only 1 case series using sulfasalazine reported worsening symptoms after treatment initiation.16 Our patient deferred systemic medications and was treated with 4 weeks of topical triamcinolone followed by 4 weeks of topical tacrolimus with minimal improvement. At the time of diagnosis, our patient also was encouraged to use sun-protective measures. At 6-month follow-up, the lesions remained stable, and the decision was made to continue with photoprotection.

The Diagnosis: Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma

Histologic examination of the shave biopsies showed a granulomatous infiltrate of small lymphocytes, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, with several also containing fragments of basophilic elastic fibers (elastophagocytosis)(Figure). Additionally, the granulomas revealed no signs of necrosis, making an infectious source unlikely, and examination under polarized light was negative for foreign material. These clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic for annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG).

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder that classically presents on sun-exposed skin as annular plaques with elevated borders and atrophic centers.1-4 Histologically, AEGCG is characterized by diffuse granulomatous infiltrates composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes in the dermis, along with phagocytosis of elastic fibers by multinucleated giant cells.5 The underlying etiology and pathogenesis of AEGCG remains unknown.6

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma commonly affects females aged 35 to 75 years; however, cases have been reported in the male and pediatric patient populations.1,2 Documented cases are known to last from 1 month to 10 years.7,8 Although the mechanisms underlying the development of AEGCG remain to be elucidated, studies have determined that the skin disorder is associated with sarcoidosis, molluscum contagiosum, amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9 Diabetes mellitus is the most common comorbidity associated with AEGCG, and it is theorized that diabetes contributes to the increased incidence of AEGCG in this population by inducing damage to elastic fibers in the skin.10 One study that examined 50 cases of AEGCG found that 38 patients had serum glucose levels evaluated, with 8 cases being subsequently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 6 cases with apparent impaired glucose tolerance, indicating that 37% of the sample population with AEGCG who were evaluated for metabolic disease were found to have definitive or latent type 2 diabetes mellitus.11 Although AEGCG is a rare disorder, a substantial number of patients diagnosed with AEGCG also have diabetes mellitus, making it important to consider screening all patients with AEGCG for diabetes given the ease and widely available resources to check glucose levels.

Actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, atypical facial necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma multiforme, secondary syphilis, tinea corporis, and erythema annulare centrifugum most commonly are included in the differential diagnosis with AEGCG; histopathology is the key determinant in discerning between these conditions.12 Our patient presented with typical annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches. With known type 2 diabetes mellitus and the clinical findings, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, and AEGCG remained high on the differential.

No standard of care exists for AEGCG due to its rare nature and tendency to spontaneously resolve. The most common first-line treatment includes topical and intralesional steroids, topical pimecrolimus, and the use of sunscreen and other sun-protective measures. UV radiation, specifically UVA, has been determined to be a causal factor for AEGCG by changing the antigenicity of elastic fibers and producing an immune response in individuals with fair skin.13 Further, resistant cases of AEGCG successfully have been treated with cyclosporine, systemic steroids, antimalarials, dapsone, and oral retinoids.14,15 Some studies reported partial regression or full resolution with topical tretinoin; adalimumab; clobetasol ointment; or a combination of corticosteroids, antihistamines, and hydroxychloroquine.2 Only 1 case series using sulfasalazine reported worsening symptoms after treatment initiation.16 Our patient deferred systemic medications and was treated with 4 weeks of topical triamcinolone followed by 4 weeks of topical tacrolimus with minimal improvement. At the time of diagnosis, our patient also was encouraged to use sun-protective measures. At 6-month follow-up, the lesions remained stable, and the decision was made to continue with photoprotection.

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456. doi:10.7759/cureus.11456

- Chen WT, Hsiao PF, Wu YH. Spectrum and clinical variants of giant cell elastolytic granuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:738-745. doi:10.1111/ijd.13502

- Raposo I, Mota F, Lobo I, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a “visible” diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9rq3j927

- Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132

- Hassan R, Arunprasath P, Padmavathy L, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:107-110. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178087

- Kaya Erdog˘ an H, Arık D, Acer E, et al. Clinicopathological features of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma patients. Turkish J Dermatol. 2018;12:85-89.

- Can B, Kavala M, Türkog˘ lu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxychloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2011.04941.x

- Arora S, Malik A, Patil C, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a report of 10 cases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(suppl 1):S17-S20. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.171055

- Doulaveri G, Tsagroni E, Giannadaki M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in a 70-year-old woman. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:290-291. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01767.x

- Marmon S, O’Reilly KE, Fischer M, et al. Papular variant of annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:23.

- Aso Y, Izaki S, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2011.04094.x

- Liu X, Zhang W, Liu Y, et al. A case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with syphilis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018; 10:158-161. doi:10.1159/000489910

- Gutiérrez-González E, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Elastolytic actinic giant cell granuloma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:331-341. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.002

- de Oliveira FL, de Barros Silveira LK, Machado Ade M, et al. Hybrid clinical and histopathological pattern in annular lesions: an overlap between annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma and granuloma annulare? Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:102915. doi:10.1155/2012/102915

- Wagenseller A, Larocca C, Vashi NA. Treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with topical tretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:699-700.

- Yang YW, Lehrer MD, Mangold AR, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and related granulomatous diseases with sulphasalazine: a series of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:211-215. doi:10.1111/jdv.16356

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456. doi:10.7759/cureus.11456

- Chen WT, Hsiao PF, Wu YH. Spectrum and clinical variants of giant cell elastolytic granuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:738-745. doi:10.1111/ijd.13502

- Raposo I, Mota F, Lobo I, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a “visible” diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9rq3j927

- Klemke CD, Siebold D, Dippel E, et al. Generalised annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Dermatology. 2003;207:420-422. doi:10.1159/000074132

- Hassan R, Arunprasath P, Padmavathy L, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:107-110. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178087

- Kaya Erdog˘ an H, Arık D, Acer E, et al. Clinicopathological features of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma patients. Turkish J Dermatol. 2018;12:85-89.

- Can B, Kavala M, Türkog˘ lu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxychloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2011.04941.x

- Arora S, Malik A, Patil C, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma: a report of 10 cases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(suppl 1):S17-S20. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.171055

- Doulaveri G, Tsagroni E, Giannadaki M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma in a 70-year-old woman. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:290-291. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01767.x

- Marmon S, O’Reilly KE, Fischer M, et al. Papular variant of annular elastolytic giant-cell granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:23.

- Aso Y, Izaki S, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2011.04094.x

- Liu X, Zhang W, Liu Y, et al. A case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with syphilis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018; 10:158-161. doi:10.1159/000489910

- Gutiérrez-González E, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Elastolytic actinic giant cell granuloma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:331-341. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.002

- de Oliveira FL, de Barros Silveira LK, Machado Ade M, et al. Hybrid clinical and histopathological pattern in annular lesions: an overlap between annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma and granuloma annulare? Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:102915. doi:10.1155/2012/102915

- Wagenseller A, Larocca C, Vashi NA. Treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with topical tretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:699-700.

- Yang YW, Lehrer MD, Mangold AR, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and related granulomatous diseases with sulphasalazine: a series of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:211-215. doi:10.1111/jdv.16356

A 58-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, nephrolithiasis, hypovitaminosis D, and hypercholesterolemia presented to our dermatology clinic for a follow-up total-body skin examination after a prior diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma on the vertex of the scalp. Physical examination revealed extensive photodamage and annular plaques overlying hyperpigmented telangiectatic patches on the dorsal portion of the neck. The eruption persisted for 1 year and failed to improve with clotrimazole cream. His medications included simvastatin, metformin, chlorthalidone, vitamin D, and tamsulosin. Two shave biopsies from the posterior neck were performed.