User login

Bilateral Burning Palmoplantar Lesions

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

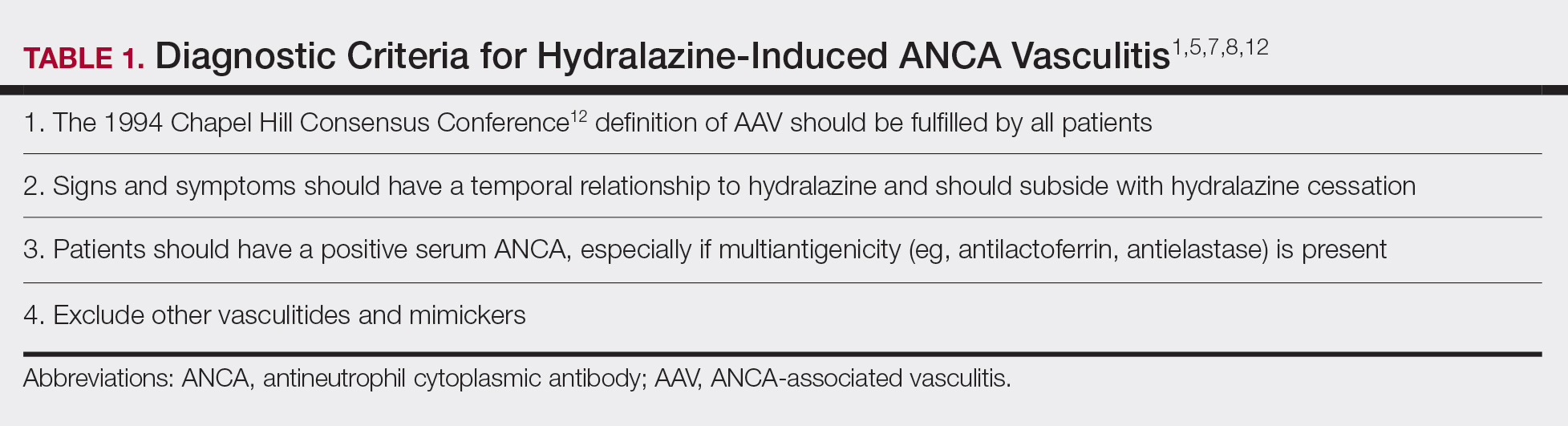

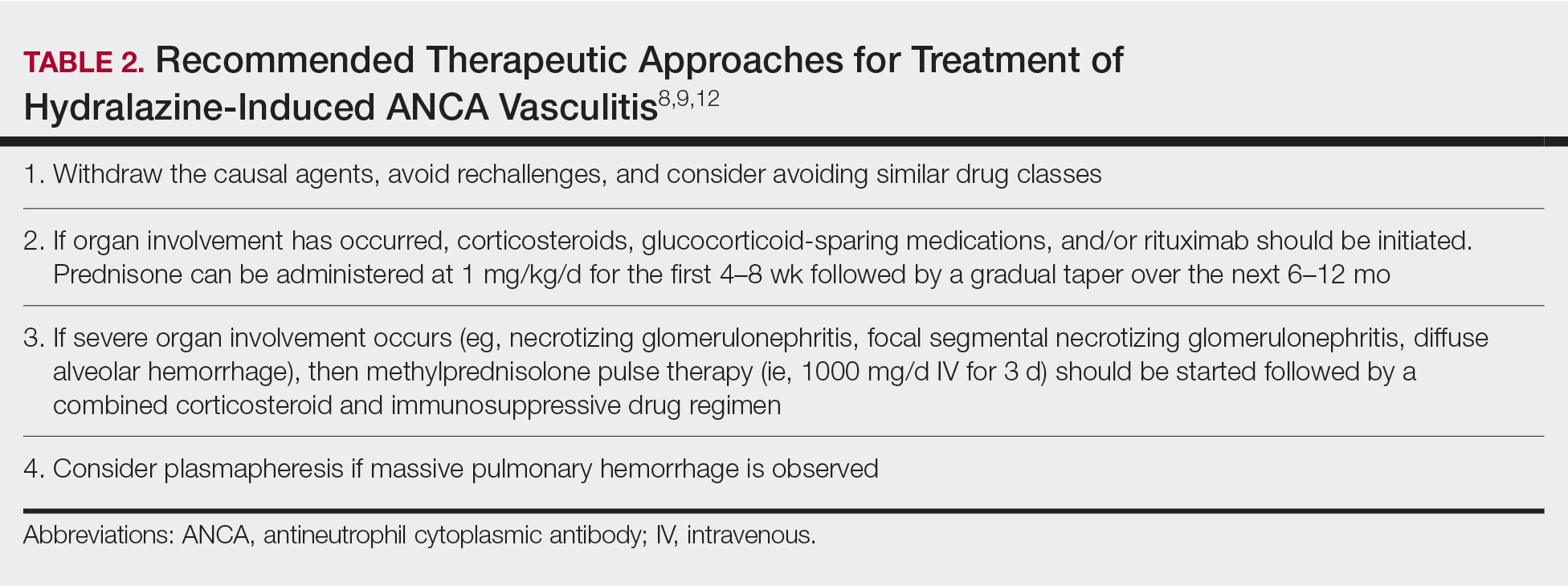

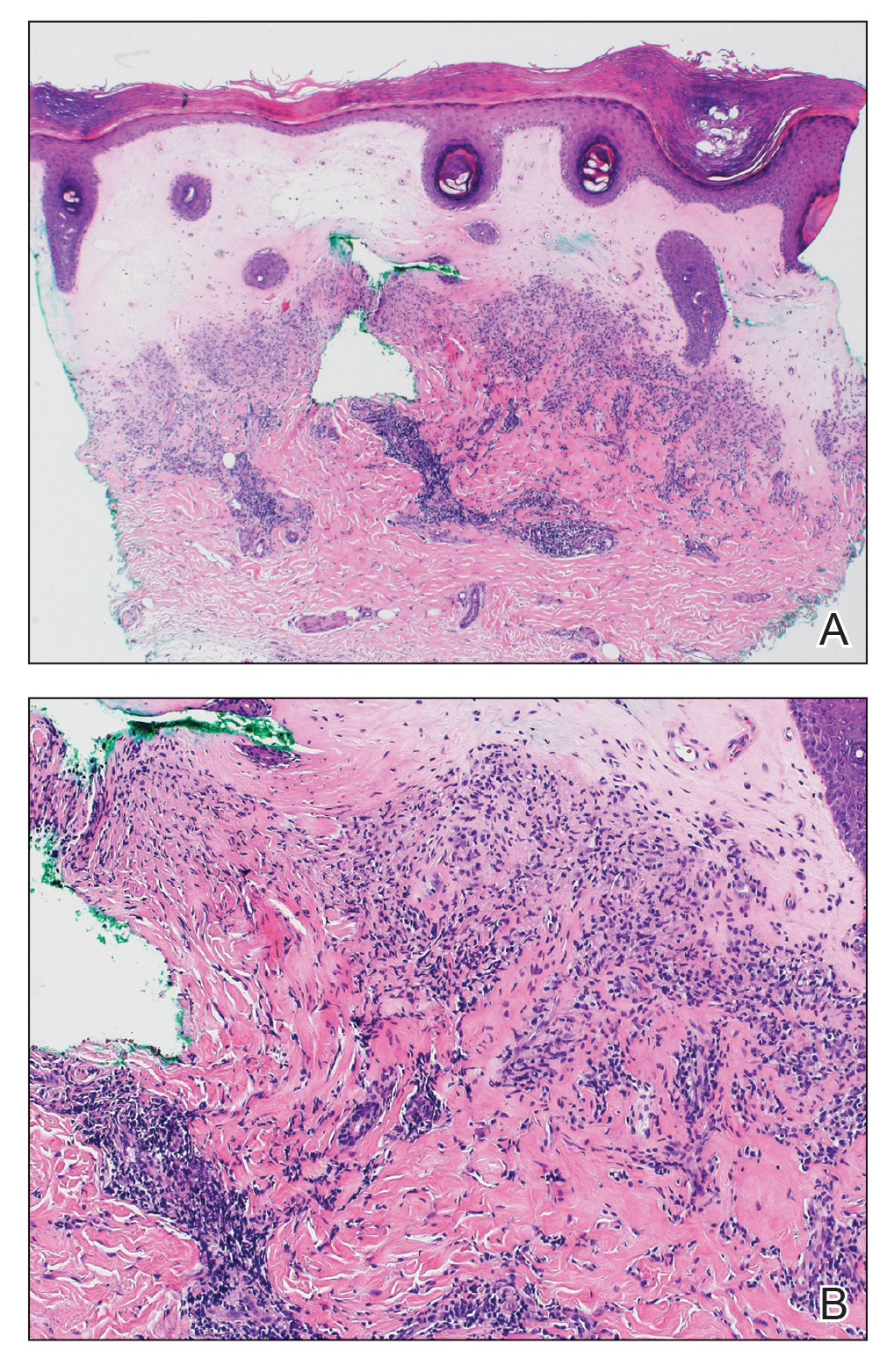

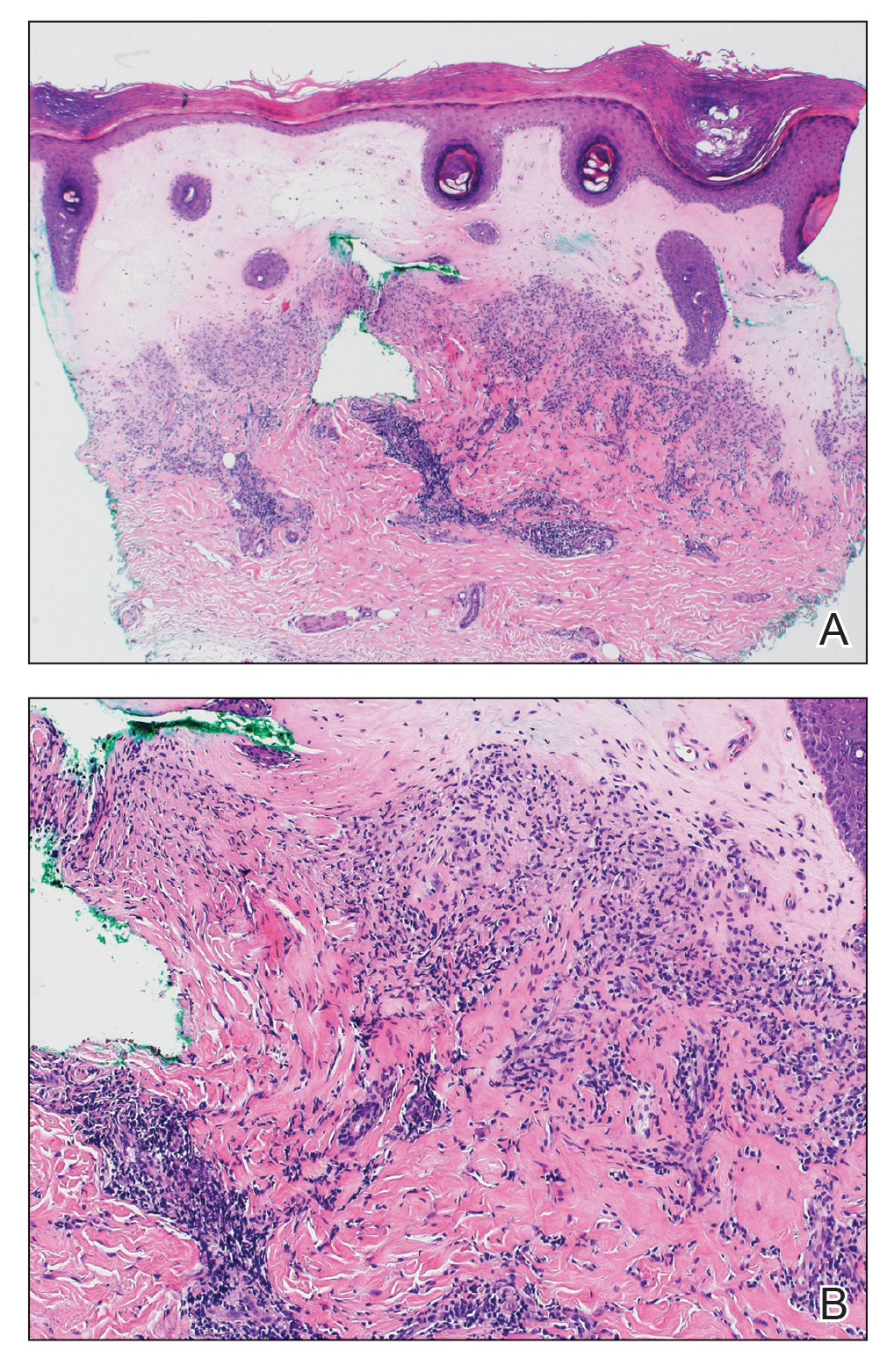

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

A 59-year-old woman presented with atrophic, hypopigmented, ivory papules and plaques localized to the central palms and soles of 3 years’ duration. The lesions were associated with burning that was most notable after extended periods of ambulation. The lesions initially were diagnosed as plaque psoriasis by an external dermatology clinic. At the time of presentation to our clinic, treatment with several highpotency topical steroids and biologics approved for plaque psoriasis had failed. Her medical history and concurrent medical workup were notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver dysfunction, thyroid nodules overseen by an endocrinologist, vitamin B12 and vitamin D deficiencies managed with supplementation, and diffuse androgenic alopecia with suspected telogen effluvium. Physical examination revealed no plaque fissuring, pruritus, or scaling. She had no history of radiation therapy or organ transplantation. A punch biopsy of the left palm was performed.

Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody Vasculitis Induced by Hydralazine

To the Editor:

Hydralazine-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis (HIAV) is a rare side effect that may develop in patients treated with hydralazine. Without early recognition and hydralazine cessation, patients often develop acute renal failure and pulmonary hemorrhage that may result in death. We present a case of HIAV.

A 67-year-old woman presented with progressive, tense, hemorrhagic, and necrotic bullae on both sides of the face and neck as well as the extremities of 2 weeks’ duration. She had a history of hypertension and a thyroid nodule after unilateral thyroid lobectomy. A review of symptoms was positive for worsening dyspnea and progressive generalized weakness. Noteworthy medications included amlodipine, metoprolol, levothyroxine, and oral hydralazine 75 mg 3 times daily for 13 months.

Bullae first appeared on the patient’s scalp and quickly progressed with a cephalocaudal pattern with a propensity for the eyes, nostrils, and labial mucosa (Figure 1). The tongue was covered by an eschar, and she had diffuse periorbital edema. Additionally, concentric purpuric patches were noted on the thighs and lower legs (Figure 2).

Pertinent laboratory findings included a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) titer of 1:160, along with an elevated serum creatinine level (2.31 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Bilateral perihilar infiltrates with bilateral pleural effusions were noted on a chest radiograph.

While hospitalized, she developed pulmonary hemorrhages and a progressive decline in respiratory status. She subsequently was admitted to the medical intensive care unit. Aggressive support was administered, and several skin biopsy specimens were obtained along with an endobronchial biopsy of the right middle lobe.

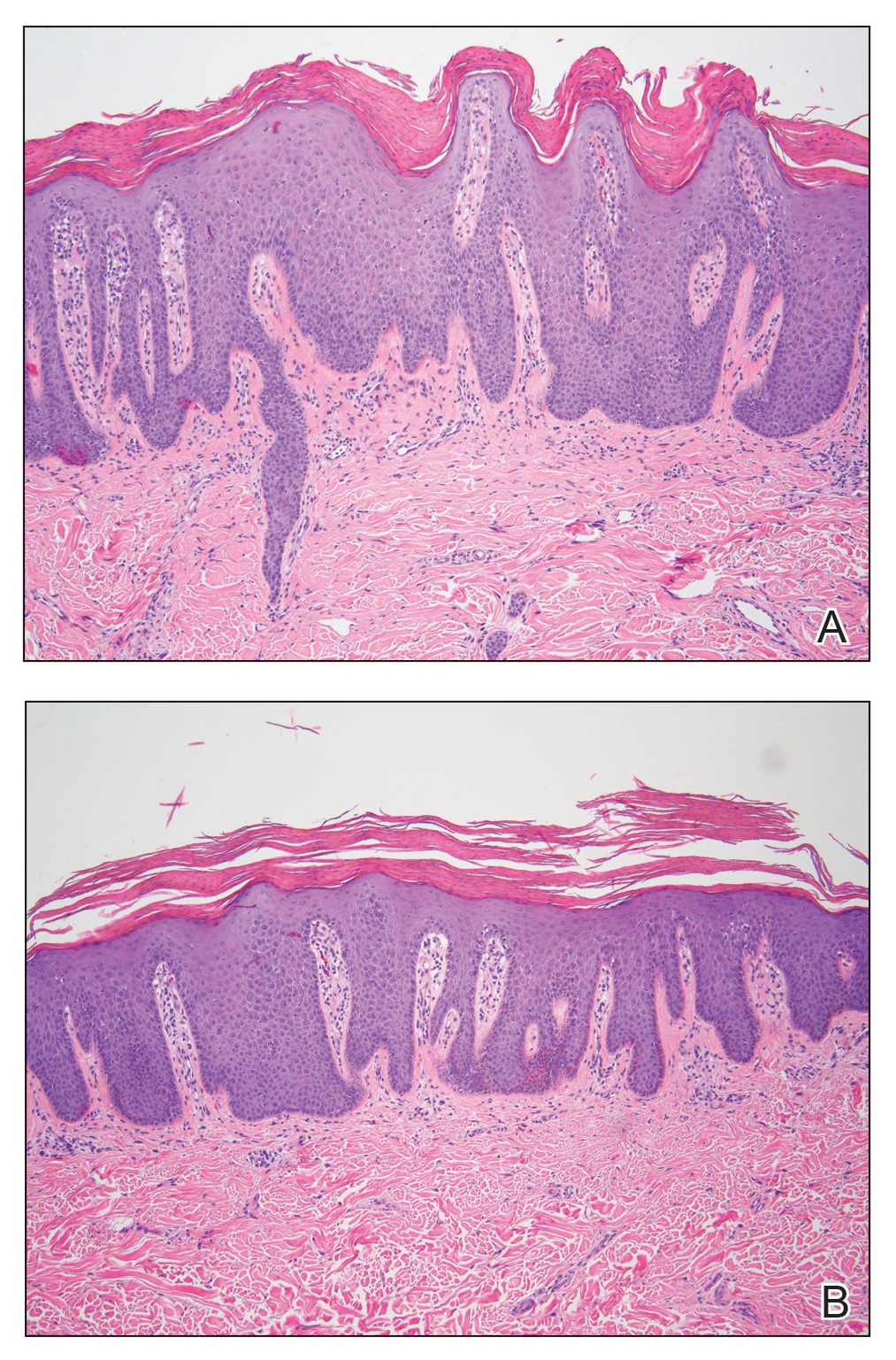

Skin histopathology revealed a necrotic vasculitis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was not performed. Lung histopathology showed fragments of bronchial tissue with acute and chronic inflammation, focal necrosis, granulation tissue formation, edema, and squamous metaplasia. Together with the clinical history, these findings were consistent with HIAV.

Hydralazine was immediately discontinued, and the patient was started on 65 mg daily of intravenous methylprednisolone; methylprednisolone was later changed to oral prednisone 30 mg daily. Due to multiple organ involvement—lung and kidney—intravenous rituximab 375 mg/m2 every week for 4 weeks, per lymphoma protocol, was started. Within 2 weeks of beginning therapy, her renal function and respiratory status improved, and by week 4, the skin lesions had completely resolved. Although initially she did well on immunosuppressive therapy with resolution of all symptoms, the patient contracted Clostridium difficile–induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome after 5 weeks of therapy and died.

Hydralazine was first introduced in 1951 for adjunctive hypertension therapy due to its vasodilation effects.1-3 Since its introduction, it has been implicated in 2 important disease processes: HIAV and hydralazine-induced lupus.

Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis was first documented in 1980; by 2011, multiple cases had been reported.1-7 Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis has occurred in patients aged 11 to 79 years taking 50 to 300 mg daily. Symptom onset varies from 6 months to 14 years, with a mean exposure duration of 4.7 years and mean daily dose of 142 mg.1-7

Clinical manifestations range from less specific, such as fever, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss, to single tissue or organ involvement that may be fatal. The most frequent clinical features include kidney involvement (81%), cutaneous vasculitis (25%), arthralgia (24%), and pleuropulmonary involvement (19%). Cutaneous manifestations include but are not limited to palpable lower extremity purpura; morbilliform eruptions; and hemorrhagic blisters on the lower legs, arms, trunk, nasal septum, and uvula.1-4,8

The most commonly affected organ is the kidney, which commonly presents as hematuria, proteinuria, and elevated serum creatinine level. Histopathologically, patients most likely will have necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis that is pauci-immune by immunofluorescence.7,9 The lungs are the next most commonly affected organ, with a classic presentation of cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis in the setting of intra-alveolar hemorrhage.6,8 When both the kidneys and lungs are involved, the patient is said to have pulmonary-renal syndrome that is characterized by lung infiltrates or nodules with or without hemorrhage, hemoptysis, and pleuritis in the setting of glomerulonephritis.1,6

Clear data on incidence and prevalence of HIAV does not exist due to the rarity of the disease and the lack of prospective studies. To identify a clear incidence and prevalence, prospective longitudinal studies with larger cohorts along with better recognition and diagnosis are needed.2,8,10 A few predisposing risk factors have been identified, including older age, a cumulative dose of 100 g at the time of presentation, female sex, a history of thyroid disease, HLA-DR4 genotypes, slow hepatic acetylation, and the null gene for C4.1,3,5,9-11 Our patient was an older woman with a history of thyroid disease who had been taking oral hydralazine 75 mg 3 times daily for 13 months. During this 13-month duration, she had no dose adjustments.

Currently, the pathomechanism for HIAV is unclear and may be multifactorial. There are 4 main theories2,8-10,12,13:

1. Hydralazine and its metabolites accumulate inside neutrophils, then subsequently bind and alter the configuration of myeloperoxidase (MPO). This alteration leads to spreading of the autoimmune response to other autoantigens, making neutrophil proteins (eg, elastase, lactoferrin, nuclear antigens) immunogenic.

2. Hydralazine binds MPO in neutrophils, creating cytotoxic products that induce neutrophil apoptosis. Neutrophil apoptosis without priming then results in ANCA antigen presence on the neutrophil cell membrane and the formation of MPO-ANCA. Myeloperoxidase-ANCA then binds to these membrane-bound antigens that cause self-perpetuating, constitutive activation through cross-linking with proteinase 3 or MPO and Fcγ receptors.

3. Activated neutrophils in the presence of hydrogen peroxidase release MPO that converts hydralazine into a cytotoxic product that is immunogenic for T cells that activate ANCA-producing B cells.

4. Histone H3 trimethyl Lys27 (H3K27me3) levels are perturbed in HIAV, which leads to aberrant gene silencing of proteinase 3 and MPO.In contrast, the demethylase Jumonji domain-containing protein 3 for the H3K27me3 histone is increased in patients without HIAV. Based on this data and the data showing a role for hydralazine in reversing epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes in cancer cells,13 it has been proposed that hydralazine may reverse epigenetic silencing of proteinase 3 and MPO.

Diagnosing HIAV is still difficult because physicians do not recognize the drug as the etiologic agent, there is extensive variability in duration between starting the drug and onset of symptoms, and there often is a failure to order the appropriate laboratory and invasive tests needed for evaluation and diagnosis.3,5,8,10,12 Despite these difficulties, a set of criteria and practices for diagnosis are delineated in Table 1, with the key diagnostic feature being resolution with hydralazine cessation.1,5,7,8,12

A comprehensive drug history from at least 6 months prior to presentation is essential. Biopsies also are strongly encouraged to confirm the presence of vasculitis and to determine its severity.8,12 If renal biopsies are performed, they typically show scant IgG, IgM, and C3 deposition that is characteristic of ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Compared to hydralazine-induced lupus, renal involvement in the setting of HIAV has a relative lack of immunoglobulin and complement deposition with histopathology and immunostaining.14

Laboratory test results including serum MPO-ANCA (perinuclear ANCA) with coexisting elastase and/or lactoferrin autoantibodies is characteristic of HIAV. Antinuclear antibody, antihistone, anti–double-stranded DNA, and antiphospholipid antibodies along with low complement levels also may be present.2,4,9,10,13,15 It is recommended that ANCA assays combine indirect immunofluorescence with antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8 With respect to its idiopathic counterpart, patients may only present with MPO-ANCA, while other aforementioned antibodies (eg, antihistone, anti–double-stranded DNA) are rarely found or are entirely absent.2,9 Patients with HIAV often have higher titers of MPO-ANCA.9,15 In hydralazine-induced lupus, patients rarely have MPO-ANCA.

When a diagnosis of HIAV is made, it cannot be confirmed until hydralazine is discontinued and the patient’s symptoms resolve. Therefore, it is both diagnostic and therapeutic to discontinue hydralazine when HIAV is suspected. If recognized when the patient is only presenting with nonspecific symptoms, simple hydralazine cessation may be all that is needed; however, because recognition and diagnosis of HIAV is difficult, most patients present when the disease is severe and has progressed to organ involvement.8-10

Treatment recommendations are highlighted in Table 2.8,9,12 Glucocorticoid therapy is believed to work by preventing T-cell and B-cell maturation needed to produce MPO-ANCA. Rituximab, on the other hand, is suspected to act by clearing the peripheral blood of MPO-ANCA B cells.12,16 Of note, patients with HIAV are different from their idiopathic counterparts because they usually need shorter courses of immunosuppressive therapy, long-term maintenance usually is unnecessary, and their prognosis generally is good if the offending agent is withdrawn.7-9,12 Once the appropriate therapy is instituted, vasculitic manifestations are expected to resolve 10 days to 8 months after hydralazine cessation; however, a response often is seen within 1 to 4 weeks after initiation of systemic treatment.4,8 Serum ANCA should be monitored, and there should be surveillance for the emergence of a chronic underlying vasculitis.8,12

Our patient highlights the importance of identifying individuals at risk for HIAV. We seek to increase recognition of this entity, as it is not commonly seen in a dermatologic setting and is associated with high morbidity and mortality, as seen in our patient.

- Yokogawa N, Vivino FB. Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:338-347.

- Agarwal G, Sultan G, Werner SL, et al. Hydralazine induces myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis and leads to pulmonary renal syndrome. Case Rep Nephrol. 2014;2014:868590.

- Keasberry J, Frazier J, Isbel NM, et al. Hydralazine-induced anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody-positive renal vasculitis presenting with a vasculitic syndrome, acute nephritis and a puzzling skin rash: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:20.

- ten Holder SM, Joy MS, Falk RJ. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of drug-induced vasculitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:130-147.

- Namas R, Rubin B, Adwar W, et al. A challenging twist in pulmonary renal syndrome. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:516362.

- Dobre M, Wish J, Negrea L. Hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Ren Fail. 2009;31:745-748.

- Hogan JJ, Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J. Drug-induced glomerular disease: immune-mediated injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1300-1310.

- Radic M, Martinovic Kaliterna D, Radic J. Drug-induced vasculitis: a clinical and pathological review. Neth J Med. 2012;70:12-17.

- Babar F, Posner JN, Obah EA. Hydralazine-induced pauci-immune glomerulonephritis: intriguing case series misleading diagnoses. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6:30632.

- Marina VP, Malhotra D, Kaw D. Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis with pulmonary renal syndrome: a rare clinical presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:1907-1909.

- Magro CM. Associated ANCA positive vasculitis. The Dermatologist. 2015;23(7). http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/associated-anca-positive-vasculitis. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Gao Y, Zhao MH. Review article: Drug-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2009;14:33-41.

- Grau RG. Drug-induced vasculitis: new insights and a changing lineup of suspects. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:71.

- Sangala N, Lee RW, Horsfield C, et al. Combined ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus syndrome following prolonged use of hydralazine: a timely reminder of an old foe. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:503-506.

- Choi HK, Merkel PA, Walker AM, et al. Drug-associated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis: prevalence among patients with high titers of antimyeloperoxidase antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:405-413.

- Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335:2-13.

To the Editor:

Hydralazine-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis (HIAV) is a rare side effect that may develop in patients treated with hydralazine. Without early recognition and hydralazine cessation, patients often develop acute renal failure and pulmonary hemorrhage that may result in death. We present a case of HIAV.

A 67-year-old woman presented with progressive, tense, hemorrhagic, and necrotic bullae on both sides of the face and neck as well as the extremities of 2 weeks’ duration. She had a history of hypertension and a thyroid nodule after unilateral thyroid lobectomy. A review of symptoms was positive for worsening dyspnea and progressive generalized weakness. Noteworthy medications included amlodipine, metoprolol, levothyroxine, and oral hydralazine 75 mg 3 times daily for 13 months.

Bullae first appeared on the patient’s scalp and quickly progressed with a cephalocaudal pattern with a propensity for the eyes, nostrils, and labial mucosa (Figure 1). The tongue was covered by an eschar, and she had diffuse periorbital edema. Additionally, concentric purpuric patches were noted on the thighs and lower legs (Figure 2).

Pertinent laboratory findings included a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) titer of 1:160, along with an elevated serum creatinine level (2.31 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Bilateral perihilar infiltrates with bilateral pleural effusions were noted on a chest radiograph.

While hospitalized, she developed pulmonary hemorrhages and a progressive decline in respiratory status. She subsequently was admitted to the medical intensive care unit. Aggressive support was administered, and several skin biopsy specimens were obtained along with an endobronchial biopsy of the right middle lobe.

Skin histopathology revealed a necrotic vasculitis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was not performed. Lung histopathology showed fragments of bronchial tissue with acute and chronic inflammation, focal necrosis, granulation tissue formation, edema, and squamous metaplasia. Together with the clinical history, these findings were consistent with HIAV.

Hydralazine was immediately discontinued, and the patient was started on 65 mg daily of intravenous methylprednisolone; methylprednisolone was later changed to oral prednisone 30 mg daily. Due to multiple organ involvement—lung and kidney—intravenous rituximab 375 mg/m2 every week for 4 weeks, per lymphoma protocol, was started. Within 2 weeks of beginning therapy, her renal function and respiratory status improved, and by week 4, the skin lesions had completely resolved. Although initially she did well on immunosuppressive therapy with resolution of all symptoms, the patient contracted Clostridium difficile–induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome after 5 weeks of therapy and died.

Hydralazine was first introduced in 1951 for adjunctive hypertension therapy due to its vasodilation effects.1-3 Since its introduction, it has been implicated in 2 important disease processes: HIAV and hydralazine-induced lupus.

Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis was first documented in 1980; by 2011, multiple cases had been reported.1-7 Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis has occurred in patients aged 11 to 79 years taking 50 to 300 mg daily. Symptom onset varies from 6 months to 14 years, with a mean exposure duration of 4.7 years and mean daily dose of 142 mg.1-7

Clinical manifestations range from less specific, such as fever, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss, to single tissue or organ involvement that may be fatal. The most frequent clinical features include kidney involvement (81%), cutaneous vasculitis (25%), arthralgia (24%), and pleuropulmonary involvement (19%). Cutaneous manifestations include but are not limited to palpable lower extremity purpura; morbilliform eruptions; and hemorrhagic blisters on the lower legs, arms, trunk, nasal septum, and uvula.1-4,8

The most commonly affected organ is the kidney, which commonly presents as hematuria, proteinuria, and elevated serum creatinine level. Histopathologically, patients most likely will have necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis that is pauci-immune by immunofluorescence.7,9 The lungs are the next most commonly affected organ, with a classic presentation of cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis in the setting of intra-alveolar hemorrhage.6,8 When both the kidneys and lungs are involved, the patient is said to have pulmonary-renal syndrome that is characterized by lung infiltrates or nodules with or without hemorrhage, hemoptysis, and pleuritis in the setting of glomerulonephritis.1,6

Clear data on incidence and prevalence of HIAV does not exist due to the rarity of the disease and the lack of prospective studies. To identify a clear incidence and prevalence, prospective longitudinal studies with larger cohorts along with better recognition and diagnosis are needed.2,8,10 A few predisposing risk factors have been identified, including older age, a cumulative dose of 100 g at the time of presentation, female sex, a history of thyroid disease, HLA-DR4 genotypes, slow hepatic acetylation, and the null gene for C4.1,3,5,9-11 Our patient was an older woman with a history of thyroid disease who had been taking oral hydralazine 75 mg 3 times daily for 13 months. During this 13-month duration, she had no dose adjustments.

Currently, the pathomechanism for HIAV is unclear and may be multifactorial. There are 4 main theories2,8-10,12,13:

1. Hydralazine and its metabolites accumulate inside neutrophils, then subsequently bind and alter the configuration of myeloperoxidase (MPO). This alteration leads to spreading of the autoimmune response to other autoantigens, making neutrophil proteins (eg, elastase, lactoferrin, nuclear antigens) immunogenic.

2. Hydralazine binds MPO in neutrophils, creating cytotoxic products that induce neutrophil apoptosis. Neutrophil apoptosis without priming then results in ANCA antigen presence on the neutrophil cell membrane and the formation of MPO-ANCA. Myeloperoxidase-ANCA then binds to these membrane-bound antigens that cause self-perpetuating, constitutive activation through cross-linking with proteinase 3 or MPO and Fcγ receptors.

3. Activated neutrophils in the presence of hydrogen peroxidase release MPO that converts hydralazine into a cytotoxic product that is immunogenic for T cells that activate ANCA-producing B cells.

4. Histone H3 trimethyl Lys27 (H3K27me3) levels are perturbed in HIAV, which leads to aberrant gene silencing of proteinase 3 and MPO.In contrast, the demethylase Jumonji domain-containing protein 3 for the H3K27me3 histone is increased in patients without HIAV. Based on this data and the data showing a role for hydralazine in reversing epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes in cancer cells,13 it has been proposed that hydralazine may reverse epigenetic silencing of proteinase 3 and MPO.

Diagnosing HIAV is still difficult because physicians do not recognize the drug as the etiologic agent, there is extensive variability in duration between starting the drug and onset of symptoms, and there often is a failure to order the appropriate laboratory and invasive tests needed for evaluation and diagnosis.3,5,8,10,12 Despite these difficulties, a set of criteria and practices for diagnosis are delineated in Table 1, with the key diagnostic feature being resolution with hydralazine cessation.1,5,7,8,12

A comprehensive drug history from at least 6 months prior to presentation is essential. Biopsies also are strongly encouraged to confirm the presence of vasculitis and to determine its severity.8,12 If renal biopsies are performed, they typically show scant IgG, IgM, and C3 deposition that is characteristic of ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Compared to hydralazine-induced lupus, renal involvement in the setting of HIAV has a relative lack of immunoglobulin and complement deposition with histopathology and immunostaining.14

Laboratory test results including serum MPO-ANCA (perinuclear ANCA) with coexisting elastase and/or lactoferrin autoantibodies is characteristic of HIAV. Antinuclear antibody, antihistone, anti–double-stranded DNA, and antiphospholipid antibodies along with low complement levels also may be present.2,4,9,10,13,15 It is recommended that ANCA assays combine indirect immunofluorescence with antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8 With respect to its idiopathic counterpart, patients may only present with MPO-ANCA, while other aforementioned antibodies (eg, antihistone, anti–double-stranded DNA) are rarely found or are entirely absent.2,9 Patients with HIAV often have higher titers of MPO-ANCA.9,15 In hydralazine-induced lupus, patients rarely have MPO-ANCA.

When a diagnosis of HIAV is made, it cannot be confirmed until hydralazine is discontinued and the patient’s symptoms resolve. Therefore, it is both diagnostic and therapeutic to discontinue hydralazine when HIAV is suspected. If recognized when the patient is only presenting with nonspecific symptoms, simple hydralazine cessation may be all that is needed; however, because recognition and diagnosis of HIAV is difficult, most patients present when the disease is severe and has progressed to organ involvement.8-10

Treatment recommendations are highlighted in Table 2.8,9,12 Glucocorticoid therapy is believed to work by preventing T-cell and B-cell maturation needed to produce MPO-ANCA. Rituximab, on the other hand, is suspected to act by clearing the peripheral blood of MPO-ANCA B cells.12,16 Of note, patients with HIAV are different from their idiopathic counterparts because they usually need shorter courses of immunosuppressive therapy, long-term maintenance usually is unnecessary, and their prognosis generally is good if the offending agent is withdrawn.7-9,12 Once the appropriate therapy is instituted, vasculitic manifestations are expected to resolve 10 days to 8 months after hydralazine cessation; however, a response often is seen within 1 to 4 weeks after initiation of systemic treatment.4,8 Serum ANCA should be monitored, and there should be surveillance for the emergence of a chronic underlying vasculitis.8,12

Our patient highlights the importance of identifying individuals at risk for HIAV. We seek to increase recognition of this entity, as it is not commonly seen in a dermatologic setting and is associated with high morbidity and mortality, as seen in our patient.

To the Editor:

Hydralazine-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis (HIAV) is a rare side effect that may develop in patients treated with hydralazine. Without early recognition and hydralazine cessation, patients often develop acute renal failure and pulmonary hemorrhage that may result in death. We present a case of HIAV.

A 67-year-old woman presented with progressive, tense, hemorrhagic, and necrotic bullae on both sides of the face and neck as well as the extremities of 2 weeks’ duration. She had a history of hypertension and a thyroid nodule after unilateral thyroid lobectomy. A review of symptoms was positive for worsening dyspnea and progressive generalized weakness. Noteworthy medications included amlodipine, metoprolol, levothyroxine, and oral hydralazine 75 mg 3 times daily for 13 months.

Bullae first appeared on the patient’s scalp and quickly progressed with a cephalocaudal pattern with a propensity for the eyes, nostrils, and labial mucosa (Figure 1). The tongue was covered by an eschar, and she had diffuse periorbital edema. Additionally, concentric purpuric patches were noted on the thighs and lower legs (Figure 2).

Pertinent laboratory findings included a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) titer of 1:160, along with an elevated serum creatinine level (2.31 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Bilateral perihilar infiltrates with bilateral pleural effusions were noted on a chest radiograph.

While hospitalized, she developed pulmonary hemorrhages and a progressive decline in respiratory status. She subsequently was admitted to the medical intensive care unit. Aggressive support was administered, and several skin biopsy specimens were obtained along with an endobronchial biopsy of the right middle lobe.

Skin histopathology revealed a necrotic vasculitis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence was not performed. Lung histopathology showed fragments of bronchial tissue with acute and chronic inflammation, focal necrosis, granulation tissue formation, edema, and squamous metaplasia. Together with the clinical history, these findings were consistent with HIAV.

Hydralazine was immediately discontinued, and the patient was started on 65 mg daily of intravenous methylprednisolone; methylprednisolone was later changed to oral prednisone 30 mg daily. Due to multiple organ involvement—lung and kidney—intravenous rituximab 375 mg/m2 every week for 4 weeks, per lymphoma protocol, was started. Within 2 weeks of beginning therapy, her renal function and respiratory status improved, and by week 4, the skin lesions had completely resolved. Although initially she did well on immunosuppressive therapy with resolution of all symptoms, the patient contracted Clostridium difficile–induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome after 5 weeks of therapy and died.

Hydralazine was first introduced in 1951 for adjunctive hypertension therapy due to its vasodilation effects.1-3 Since its introduction, it has been implicated in 2 important disease processes: HIAV and hydralazine-induced lupus.

Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis was first documented in 1980; by 2011, multiple cases had been reported.1-7 Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis has occurred in patients aged 11 to 79 years taking 50 to 300 mg daily. Symptom onset varies from 6 months to 14 years, with a mean exposure duration of 4.7 years and mean daily dose of 142 mg.1-7

Clinical manifestations range from less specific, such as fever, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss, to single tissue or organ involvement that may be fatal. The most frequent clinical features include kidney involvement (81%), cutaneous vasculitis (25%), arthralgia (24%), and pleuropulmonary involvement (19%). Cutaneous manifestations include but are not limited to palpable lower extremity purpura; morbilliform eruptions; and hemorrhagic blisters on the lower legs, arms, trunk, nasal septum, and uvula.1-4,8

The most commonly affected organ is the kidney, which commonly presents as hematuria, proteinuria, and elevated serum creatinine level. Histopathologically, patients most likely will have necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis that is pauci-immune by immunofluorescence.7,9 The lungs are the next most commonly affected organ, with a classic presentation of cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis in the setting of intra-alveolar hemorrhage.6,8 When both the kidneys and lungs are involved, the patient is said to have pulmonary-renal syndrome that is characterized by lung infiltrates or nodules with or without hemorrhage, hemoptysis, and pleuritis in the setting of glomerulonephritis.1,6

Clear data on incidence and prevalence of HIAV does not exist due to the rarity of the disease and the lack of prospective studies. To identify a clear incidence and prevalence, prospective longitudinal studies with larger cohorts along with better recognition and diagnosis are needed.2,8,10 A few predisposing risk factors have been identified, including older age, a cumulative dose of 100 g at the time of presentation, female sex, a history of thyroid disease, HLA-DR4 genotypes, slow hepatic acetylation, and the null gene for C4.1,3,5,9-11 Our patient was an older woman with a history of thyroid disease who had been taking oral hydralazine 75 mg 3 times daily for 13 months. During this 13-month duration, she had no dose adjustments.

Currently, the pathomechanism for HIAV is unclear and may be multifactorial. There are 4 main theories2,8-10,12,13:

1. Hydralazine and its metabolites accumulate inside neutrophils, then subsequently bind and alter the configuration of myeloperoxidase (MPO). This alteration leads to spreading of the autoimmune response to other autoantigens, making neutrophil proteins (eg, elastase, lactoferrin, nuclear antigens) immunogenic.

2. Hydralazine binds MPO in neutrophils, creating cytotoxic products that induce neutrophil apoptosis. Neutrophil apoptosis without priming then results in ANCA antigen presence on the neutrophil cell membrane and the formation of MPO-ANCA. Myeloperoxidase-ANCA then binds to these membrane-bound antigens that cause self-perpetuating, constitutive activation through cross-linking with proteinase 3 or MPO and Fcγ receptors.

3. Activated neutrophils in the presence of hydrogen peroxidase release MPO that converts hydralazine into a cytotoxic product that is immunogenic for T cells that activate ANCA-producing B cells.

4. Histone H3 trimethyl Lys27 (H3K27me3) levels are perturbed in HIAV, which leads to aberrant gene silencing of proteinase 3 and MPO.In contrast, the demethylase Jumonji domain-containing protein 3 for the H3K27me3 histone is increased in patients without HIAV. Based on this data and the data showing a role for hydralazine in reversing epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes in cancer cells,13 it has been proposed that hydralazine may reverse epigenetic silencing of proteinase 3 and MPO.

Diagnosing HIAV is still difficult because physicians do not recognize the drug as the etiologic agent, there is extensive variability in duration between starting the drug and onset of symptoms, and there often is a failure to order the appropriate laboratory and invasive tests needed for evaluation and diagnosis.3,5,8,10,12 Despite these difficulties, a set of criteria and practices for diagnosis are delineated in Table 1, with the key diagnostic feature being resolution with hydralazine cessation.1,5,7,8,12

A comprehensive drug history from at least 6 months prior to presentation is essential. Biopsies also are strongly encouraged to confirm the presence of vasculitis and to determine its severity.8,12 If renal biopsies are performed, they typically show scant IgG, IgM, and C3 deposition that is characteristic of ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Compared to hydralazine-induced lupus, renal involvement in the setting of HIAV has a relative lack of immunoglobulin and complement deposition with histopathology and immunostaining.14

Laboratory test results including serum MPO-ANCA (perinuclear ANCA) with coexisting elastase and/or lactoferrin autoantibodies is characteristic of HIAV. Antinuclear antibody, antihistone, anti–double-stranded DNA, and antiphospholipid antibodies along with low complement levels also may be present.2,4,9,10,13,15 It is recommended that ANCA assays combine indirect immunofluorescence with antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8 With respect to its idiopathic counterpart, patients may only present with MPO-ANCA, while other aforementioned antibodies (eg, antihistone, anti–double-stranded DNA) are rarely found or are entirely absent.2,9 Patients with HIAV often have higher titers of MPO-ANCA.9,15 In hydralazine-induced lupus, patients rarely have MPO-ANCA.

When a diagnosis of HIAV is made, it cannot be confirmed until hydralazine is discontinued and the patient’s symptoms resolve. Therefore, it is both diagnostic and therapeutic to discontinue hydralazine when HIAV is suspected. If recognized when the patient is only presenting with nonspecific symptoms, simple hydralazine cessation may be all that is needed; however, because recognition and diagnosis of HIAV is difficult, most patients present when the disease is severe and has progressed to organ involvement.8-10

Treatment recommendations are highlighted in Table 2.8,9,12 Glucocorticoid therapy is believed to work by preventing T-cell and B-cell maturation needed to produce MPO-ANCA. Rituximab, on the other hand, is suspected to act by clearing the peripheral blood of MPO-ANCA B cells.12,16 Of note, patients with HIAV are different from their idiopathic counterparts because they usually need shorter courses of immunosuppressive therapy, long-term maintenance usually is unnecessary, and their prognosis generally is good if the offending agent is withdrawn.7-9,12 Once the appropriate therapy is instituted, vasculitic manifestations are expected to resolve 10 days to 8 months after hydralazine cessation; however, a response often is seen within 1 to 4 weeks after initiation of systemic treatment.4,8 Serum ANCA should be monitored, and there should be surveillance for the emergence of a chronic underlying vasculitis.8,12

Our patient highlights the importance of identifying individuals at risk for HIAV. We seek to increase recognition of this entity, as it is not commonly seen in a dermatologic setting and is associated with high morbidity and mortality, as seen in our patient.

- Yokogawa N, Vivino FB. Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:338-347.

- Agarwal G, Sultan G, Werner SL, et al. Hydralazine induces myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis and leads to pulmonary renal syndrome. Case Rep Nephrol. 2014;2014:868590.

- Keasberry J, Frazier J, Isbel NM, et al. Hydralazine-induced anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody-positive renal vasculitis presenting with a vasculitic syndrome, acute nephritis and a puzzling skin rash: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:20.

- ten Holder SM, Joy MS, Falk RJ. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of drug-induced vasculitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:130-147.

- Namas R, Rubin B, Adwar W, et al. A challenging twist in pulmonary renal syndrome. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:516362.

- Dobre M, Wish J, Negrea L. Hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Ren Fail. 2009;31:745-748.

- Hogan JJ, Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J. Drug-induced glomerular disease: immune-mediated injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1300-1310.

- Radic M, Martinovic Kaliterna D, Radic J. Drug-induced vasculitis: a clinical and pathological review. Neth J Med. 2012;70:12-17.

- Babar F, Posner JN, Obah EA. Hydralazine-induced pauci-immune glomerulonephritis: intriguing case series misleading diagnoses. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6:30632.

- Marina VP, Malhotra D, Kaw D. Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis with pulmonary renal syndrome: a rare clinical presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:1907-1909.

- Magro CM. Associated ANCA positive vasculitis. The Dermatologist. 2015;23(7). http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/associated-anca-positive-vasculitis. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Gao Y, Zhao MH. Review article: Drug-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2009;14:33-41.

- Grau RG. Drug-induced vasculitis: new insights and a changing lineup of suspects. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:71.

- Sangala N, Lee RW, Horsfield C, et al. Combined ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus syndrome following prolonged use of hydralazine: a timely reminder of an old foe. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:503-506.

- Choi HK, Merkel PA, Walker AM, et al. Drug-associated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis: prevalence among patients with high titers of antimyeloperoxidase antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:405-413.

- Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335:2-13.

- Yokogawa N, Vivino FB. Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:338-347.

- Agarwal G, Sultan G, Werner SL, et al. Hydralazine induces myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis and leads to pulmonary renal syndrome. Case Rep Nephrol. 2014;2014:868590.

- Keasberry J, Frazier J, Isbel NM, et al. Hydralazine-induced anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody-positive renal vasculitis presenting with a vasculitic syndrome, acute nephritis and a puzzling skin rash: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:20.

- ten Holder SM, Joy MS, Falk RJ. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of drug-induced vasculitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:130-147.

- Namas R, Rubin B, Adwar W, et al. A challenging twist in pulmonary renal syndrome. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:516362.

- Dobre M, Wish J, Negrea L. Hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Ren Fail. 2009;31:745-748.

- Hogan JJ, Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J. Drug-induced glomerular disease: immune-mediated injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1300-1310.

- Radic M, Martinovic Kaliterna D, Radic J. Drug-induced vasculitis: a clinical and pathological review. Neth J Med. 2012;70:12-17.

- Babar F, Posner JN, Obah EA. Hydralazine-induced pauci-immune glomerulonephritis: intriguing case series misleading diagnoses. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6:30632.

- Marina VP, Malhotra D, Kaw D. Hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis with pulmonary renal syndrome: a rare clinical presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:1907-1909.

- Magro CM. Associated ANCA positive vasculitis. The Dermatologist. 2015;23(7). http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/associated-anca-positive-vasculitis. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Gao Y, Zhao MH. Review article: Drug-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2009;14:33-41.

- Grau RG. Drug-induced vasculitis: new insights and a changing lineup of suspects. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:71.

- Sangala N, Lee RW, Horsfield C, et al. Combined ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus syndrome following prolonged use of hydralazine: a timely reminder of an old foe. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:503-506.

- Choi HK, Merkel PA, Walker AM, et al. Drug-associated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis: prevalence among patients with high titers of antimyeloperoxidase antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:405-413.

- Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335:2-13.

Practice Points

- Hydralazine-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis (HIAV) is a rare side effect of hydralazine treatment and can have notable morbidity and mortality.

- Incidence and prevalence of HIAV is unclear due to its rarity, but risk factors that have been identified are older age, a cumulative dose of 100 g of hydralazine at the time of presentation, female sex, thyroid disease, HLA-DR4 genotypes, slow hepatic acetylation, and the null gene for C4.

- Symptoms of HIAV can include fever, malaise, arthralgia, weight loss, or even involvement of organs such as the kidneys and lungs.

- If recognized early, cessation of hydralazine and supportive therapy generally are sufficient; however, severe cases may need management with high-dose corticosteroids, rituximab, and even plasmapheresis.

Verrucous Psoriasis Treated With Methotrexate and Acitretin Combination Therapy

To the Editor:

A 76-year-old woman with venous insufficiency presented with numerous thick, hyperkeratotic, confluent papules and plaques involving both legs and thighs as well as the lower back. She initially developed lesions on the distal legs, which progressed to involve the thighs and lower back, slowly enlarging over 7 years (Figure 1). The eruption was associated with pruritus and was profoundly malodorous. The patient had been unsuccessfully treated with triamcinolone ointment, bleach baths, and several courses of oral antibiotics. Her history was remarkable for marked venous insufficiency and mild anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). She had no other abnormalities on a comprehensive blood test, basic metabolic panel, or liver function test.

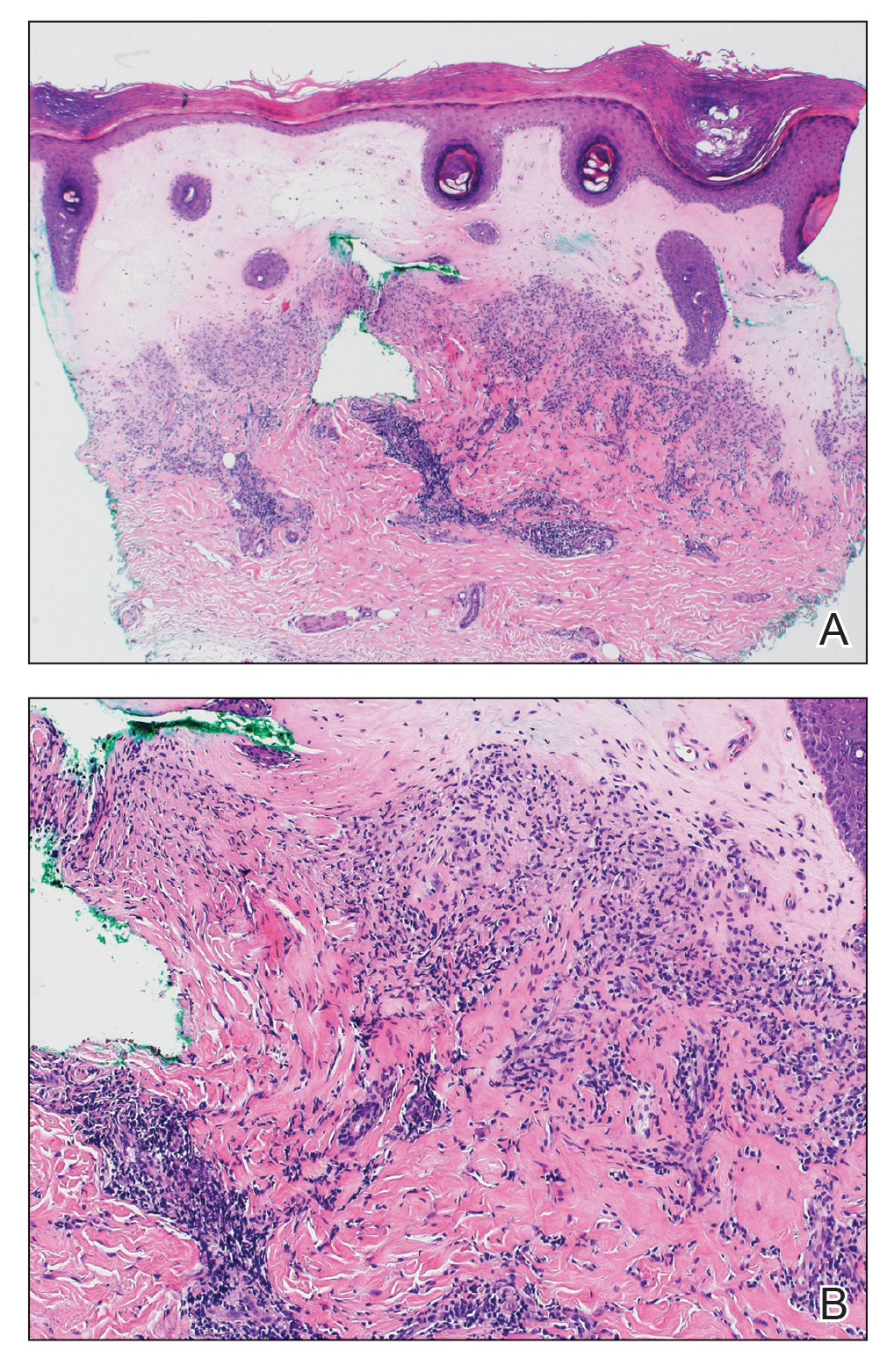

A punch biopsy specimen from the left lower back was obtained and demonstrated papillomatous psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with broad parakeratosis, few intracorneal neutrophils, hypogranulosis, and suprapapillary thinning (Figure 2). She was initially treated with oral methotrexate (20 mg weekly), resulting in partial improvement of plaques and complete resolution of pruritus and malodor. After 15 months of treatment with methotrexate, low-dose methotrexate (10 mg weekly) in combination with acitretin 25 mg daily was started, resulting in further improvement of hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). The patient also was given a compounded corticosteroid ointment containing liquor carbonis detergens, salicylic acid, and fluocinonide ointment, achieving minor additional benefit. Comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and liver function tests were obtained quarterly. Hemoglobin levels remained low, similar to baseline (11.3–12.5 g/dL), while all other values were within reference range. The patient tolerated treatment well, reporting mild dryness of lips on review of systems, which was attributed to acitretin and was treated with emollients.

Verrucous psoriasis is an uncommon variant of psoriasis that presents as localized annular, erythrodermic, or drug-induced disease, as reported in a patient with preexisting psoriasis after interferon treatment of hepatitis C.1,2 It is characterized by symmetric hypertrophic verrucous plaques that may have an erythematous base and involve the legs, arms, trunk, and dorsal aspect of the hands3; malodor is frequent.1 Histopathologically, overlapping features of verruca vulgaris and psoriasis have been described. Specifically, lesions display typical psoriasiform changes, including parakeratosis, epidermal acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges, suprapapillary thinning, epidermal hypogranulosis, dilated or tortuous capillaries, and neutrophil collections in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or stratum spinosum (spongiform pustules of Kogoj).3 Additional findings of papillomatosis and epithelial buttressing are highly suggestive of verrucous psoriasis,3 though epithelial buttressing is not universally present.4-6 Similarly, although eosinophils and plasma cells have been described in some patients with verrucous psoriasis, this finding has not been consistently reported.4-6 Our biopsy specimen (Figure 2) lacks the epithelial buttressing but does exhibit subtle papillomatous hyperplasia consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis.

The etiology of this entity is unknown. An association with diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, lymphatic circulation disorders, and immunosuppression has been proposed. Others have reported repeated trauma as contributing to the pathogenesis.1 For our patient, trauma secondary to scratching, long-standing venous insufficiency, and neglect likely contributed to the development of verrucous plaques.

The diagnosis of verrucous psoriasis can be challenging because of its similarity to several other entities, including verruca vulgaris; epidermal nevus; and squamous cell carcinoma, particularly verrucous carcinoma.4,6,7 The diagnosis has been less challenging in areas where prior typical psoriatic lesions evolved into a verrucous morphology. Our patient presented a diagnostic challenge and draws attention to this unique variant of psoriasis that could easily be misdiagnosed and lead to inappropriate treatment.

Verrucous psoriasis can be recalcitrant to therapy. Although studies addressing treatment modalities are lacking, several recommendations can be derived from case reports and our patient. The use of topical therapies, including topical corticosteroids (eg, fluocinonide, clobetasol, halobetasol), keratolytic agents (eg, urea, salicylic acid), and calcipotriene, provide only minimal improvement when used as monotherapy.1 Better success has been reported with systemic therapies, mainly methotrexate and acitretin, with anecdotal reports favoring the use of oral retinoids.1,6 Conversely, biologic medications such as etanercept, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and infliximab have only provided a partial response.1 Combination therapies including intralesional triamcinolone plus methotrexate4 or methotrexate plus acitretin, as in our patient, seem to provide additional benefit. Methotrexate and acitretin combination therapy has traditionally been avoided because of the risk for hepatotoxicity. However, a case series has demonstrated a moderate safety profile with concurrent use of these drugs in treatment-resistant psoriasis.8 In our case, clinical response was most pronounced with combination therapy of methotrexate 10 mg weekly and acitretin 25 mg daily. Thus, strong consideration should be given for combination methotrexate-acitretin therapy in patients with recalcitrant verrucous psoriasis who lack comorbid conditions.

We present a case of verrucous psoriasis, a variant of psoriasis characterized by hypertrophic plaques. We propose that venous insufficiency and long-standing untreated disease was instrumental to the development of these lesions. Furthermore, retinoids, particularly in combination with methotrexate, provided the most benefit for our patient.

Acknowledgment

We thank Stephen Somach, MD (Cleveland, Ohio), for his help interpreting the microscopic findings in our biopsy specimen. He received no compensation.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Scavo S, Gurrera A, Mazzaglia C, et al. Verrucous psoriasis in a patient with chronic C hepatitis treated with interferon. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:427-429.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(suppl 1):AB218.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Larsen F, Susa JS, Cockerell CJ, et al. Case of multiple verrucous carcinomas responding to treatment with acetretin more likely to have been a case of verrucous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:534-535.

- Kuan YZ, Hsu HC, Kuo TT, et al. Multiple verrucous carcinomas treated with acitretin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S29-S32.

- Lowenthal KE, Horn PJ, Kalb RE. Concurrent use of methotrexate and acitretin revisited. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:22-26.

To the Editor:

A 76-year-old woman with venous insufficiency presented with numerous thick, hyperkeratotic, confluent papules and plaques involving both legs and thighs as well as the lower back. She initially developed lesions on the distal legs, which progressed to involve the thighs and lower back, slowly enlarging over 7 years (Figure 1). The eruption was associated with pruritus and was profoundly malodorous. The patient had been unsuccessfully treated with triamcinolone ointment, bleach baths, and several courses of oral antibiotics. Her history was remarkable for marked venous insufficiency and mild anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). She had no other abnormalities on a comprehensive blood test, basic metabolic panel, or liver function test.

A punch biopsy specimen from the left lower back was obtained and demonstrated papillomatous psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with broad parakeratosis, few intracorneal neutrophils, hypogranulosis, and suprapapillary thinning (Figure 2). She was initially treated with oral methotrexate (20 mg weekly), resulting in partial improvement of plaques and complete resolution of pruritus and malodor. After 15 months of treatment with methotrexate, low-dose methotrexate (10 mg weekly) in combination with acitretin 25 mg daily was started, resulting in further improvement of hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). The patient also was given a compounded corticosteroid ointment containing liquor carbonis detergens, salicylic acid, and fluocinonide ointment, achieving minor additional benefit. Comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and liver function tests were obtained quarterly. Hemoglobin levels remained low, similar to baseline (11.3–12.5 g/dL), while all other values were within reference range. The patient tolerated treatment well, reporting mild dryness of lips on review of systems, which was attributed to acitretin and was treated with emollients.

Verrucous psoriasis is an uncommon variant of psoriasis that presents as localized annular, erythrodermic, or drug-induced disease, as reported in a patient with preexisting psoriasis after interferon treatment of hepatitis C.1,2 It is characterized by symmetric hypertrophic verrucous plaques that may have an erythematous base and involve the legs, arms, trunk, and dorsal aspect of the hands3; malodor is frequent.1 Histopathologically, overlapping features of verruca vulgaris and psoriasis have been described. Specifically, lesions display typical psoriasiform changes, including parakeratosis, epidermal acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges, suprapapillary thinning, epidermal hypogranulosis, dilated or tortuous capillaries, and neutrophil collections in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or stratum spinosum (spongiform pustules of Kogoj).3 Additional findings of papillomatosis and epithelial buttressing are highly suggestive of verrucous psoriasis,3 though epithelial buttressing is not universally present.4-6 Similarly, although eosinophils and plasma cells have been described in some patients with verrucous psoriasis, this finding has not been consistently reported.4-6 Our biopsy specimen (Figure 2) lacks the epithelial buttressing but does exhibit subtle papillomatous hyperplasia consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis.

The etiology of this entity is unknown. An association with diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, lymphatic circulation disorders, and immunosuppression has been proposed. Others have reported repeated trauma as contributing to the pathogenesis.1 For our patient, trauma secondary to scratching, long-standing venous insufficiency, and neglect likely contributed to the development of verrucous plaques.

The diagnosis of verrucous psoriasis can be challenging because of its similarity to several other entities, including verruca vulgaris; epidermal nevus; and squamous cell carcinoma, particularly verrucous carcinoma.4,6,7 The diagnosis has been less challenging in areas where prior typical psoriatic lesions evolved into a verrucous morphology. Our patient presented a diagnostic challenge and draws attention to this unique variant of psoriasis that could easily be misdiagnosed and lead to inappropriate treatment.

Verrucous psoriasis can be recalcitrant to therapy. Although studies addressing treatment modalities are lacking, several recommendations can be derived from case reports and our patient. The use of topical therapies, including topical corticosteroids (eg, fluocinonide, clobetasol, halobetasol), keratolytic agents (eg, urea, salicylic acid), and calcipotriene, provide only minimal improvement when used as monotherapy.1 Better success has been reported with systemic therapies, mainly methotrexate and acitretin, with anecdotal reports favoring the use of oral retinoids.1,6 Conversely, biologic medications such as etanercept, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and infliximab have only provided a partial response.1 Combination therapies including intralesional triamcinolone plus methotrexate4 or methotrexate plus acitretin, as in our patient, seem to provide additional benefit. Methotrexate and acitretin combination therapy has traditionally been avoided because of the risk for hepatotoxicity. However, a case series has demonstrated a moderate safety profile with concurrent use of these drugs in treatment-resistant psoriasis.8 In our case, clinical response was most pronounced with combination therapy of methotrexate 10 mg weekly and acitretin 25 mg daily. Thus, strong consideration should be given for combination methotrexate-acitretin therapy in patients with recalcitrant verrucous psoriasis who lack comorbid conditions.

We present a case of verrucous psoriasis, a variant of psoriasis characterized by hypertrophic plaques. We propose that venous insufficiency and long-standing untreated disease was instrumental to the development of these lesions. Furthermore, retinoids, particularly in combination with methotrexate, provided the most benefit for our patient.

Acknowledgment

We thank Stephen Somach, MD (Cleveland, Ohio), for his help interpreting the microscopic findings in our biopsy specimen. He received no compensation.

To the Editor:

A 76-year-old woman with venous insufficiency presented with numerous thick, hyperkeratotic, confluent papules and plaques involving both legs and thighs as well as the lower back. She initially developed lesions on the distal legs, which progressed to involve the thighs and lower back, slowly enlarging over 7 years (Figure 1). The eruption was associated with pruritus and was profoundly malodorous. The patient had been unsuccessfully treated with triamcinolone ointment, bleach baths, and several courses of oral antibiotics. Her history was remarkable for marked venous insufficiency and mild anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). She had no other abnormalities on a comprehensive blood test, basic metabolic panel, or liver function test.

A punch biopsy specimen from the left lower back was obtained and demonstrated papillomatous psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with broad parakeratosis, few intracorneal neutrophils, hypogranulosis, and suprapapillary thinning (Figure 2). She was initially treated with oral methotrexate (20 mg weekly), resulting in partial improvement of plaques and complete resolution of pruritus and malodor. After 15 months of treatment with methotrexate, low-dose methotrexate (10 mg weekly) in combination with acitretin 25 mg daily was started, resulting in further improvement of hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). The patient also was given a compounded corticosteroid ointment containing liquor carbonis detergens, salicylic acid, and fluocinonide ointment, achieving minor additional benefit. Comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and liver function tests were obtained quarterly. Hemoglobin levels remained low, similar to baseline (11.3–12.5 g/dL), while all other values were within reference range. The patient tolerated treatment well, reporting mild dryness of lips on review of systems, which was attributed to acitretin and was treated with emollients.

Verrucous psoriasis is an uncommon variant of psoriasis that presents as localized annular, erythrodermic, or drug-induced disease, as reported in a patient with preexisting psoriasis after interferon treatment of hepatitis C.1,2 It is characterized by symmetric hypertrophic verrucous plaques that may have an erythematous base and involve the legs, arms, trunk, and dorsal aspect of the hands3; malodor is frequent.1 Histopathologically, overlapping features of verruca vulgaris and psoriasis have been described. Specifically, lesions display typical psoriasiform changes, including parakeratosis, epidermal acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges, suprapapillary thinning, epidermal hypogranulosis, dilated or tortuous capillaries, and neutrophil collections in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or stratum spinosum (spongiform pustules of Kogoj).3 Additional findings of papillomatosis and epithelial buttressing are highly suggestive of verrucous psoriasis,3 though epithelial buttressing is not universally present.4-6 Similarly, although eosinophils and plasma cells have been described in some patients with verrucous psoriasis, this finding has not been consistently reported.4-6 Our biopsy specimen (Figure 2) lacks the epithelial buttressing but does exhibit subtle papillomatous hyperplasia consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis.