User login

Perioperative cardiovascular medicine: 5 questions for 2018

A plethora of studies are under way in the field of perioperative medicine. As a result, evidence-based care of surgical patients is evolving at an exponential rate.

We performed a literature search and, using consensus, identified recent articles we believe will have a great impact on perioperative cardiovascular medicine. These articles report studies that were presented at national meetings in 2018, including the Perioperative Medicine Summit, Society of General Internal Medicine, and Society of Hospital Medicine. These articles are grouped under 5 questions that will help guide clinical practice in perioperative cardiovascular medicine.

SHOULD ASPIRIN BE CONTINUED PERIOPERATIVELY IN PATIENTS WITH A CORONARY STENT?

The Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2 (POISE-2) trial1 found that giving aspirin before surgery and throughout the early postoperative period had no significant effect on the rate of a composite of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction; moreover, aspirin increased the risk of major bleeding. However, many experts felt uncomfortable stopping aspirin preoperatively in patients taking it for secondary prophylaxis, particularly patients with a coronary stent.

[Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244.]

This post hoc subgroup analysis2 of POISE-2 evaluated the benefit and harm of perioperative aspirin in patients who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, more than 90% of whom had received a stent. Patients were age 45 or older with atherosclerotic heart disease or risk factors for it who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention and were now undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Patients who had received a bare-metal stent within the previous 6 weeks or a drug-eluting stent within 12 months before surgery were excluded because guidelines at that time said to continue dual antiplatelet therapy for that long. Recommendations have since changed; the optimal duration for dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents is now 6 months. Second-generation drug-eluting stents pose a lower risk of stent thrombosis and require a shorter duration of dual antiplatelet therapy than first-generation drug-eluting stents. Approximately 25% of the percutaneous coronary intervention subgroup had a drug-eluting stent, but the authors did not specify the type of drug-eluting stent.

The post hoc analysis2 included a subgroup of 234 of 4,998 patients receiving aspirin and 236 of 5,012 patients receiving placebo initiated within 4 hours before surgery and continued postoperatively. The primary outcome measured was the rate of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction within 30 days after surgery, and bleeding was a secondary outcome.

Findings. Although the overall POISE-2 study found no benefit from aspirin, in the subgroup who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, aspirin significantly reduced the risk of the primary outcome, which occurred in 6% vs 11.5% of the patients:

- Absolute risk reduction 5.5% (95% confidence interval 0.4%–10.5%)

- Hazard ratio 0.50 (0.26–0.95).

The reduction was primarily due to fewer myocardial infarctions:

- Absolute risk reduction 5.9% (1.0%–10.8%)

- Hazard ratio 0.44 (0.22–0.87).

The type of stent had no effect on the primary outcome, although this subgroup analysis had limited power. In the nonpercutaneous coronary intervention subgroup, there was no significant difference in outcomes between the aspirin and placebo groups. This subgroup analysis was underpowered to evaluate the effect of aspirin on the composite of major and life-threatening bleeding in patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention, which was reported as “uncertain” due to wide confidence intervals (absolute risk increase 1.3%, 95% confidence interval –2.6% to 5.2%), but the increased risk of major or life-threatening bleeding with aspirin demonstrated in the overall POISE-2 study population likely applies:

- Absolute risk increase 0.8% (0.1%–1.6%)

- Hazard ratio 1.22 (1.01–1.48).

Limitations. This was a nonspecified subgroup analysis that was underpowered and had a relatively small sample size with few events.

Conclusion. In the absence of a very high bleeding risk, continuing aspirin perioperatively in patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery is more likely to result in benefit than harm. This finding is in agreement with current recommendations from the American College Cardiology and American Heart Association (class I; level of evidence C).3

WHAT IS THE INCIDENCE OF MINS? IS MEASURING TROPONIN USEFUL?

Despite advances in anesthesia and surgical techniques, about 1% of patients over age 45 die within 30 days of noncardiac surgery.4 Studies have demonstrated a high mortality rate in patients who experience myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery (MINS), defined as elevations of troponin T with or without ischemic symptoms or electrocardiographic changes.5 Most of these studies used earlier, “non-high-sensitivity” troponin T assays. Fifth-generation, highly sensitive troponin T assays are now available that can detect troponin T at lower concentrations, but their utility in predicting postoperative outcomes remains uncertain. Two recent studies provide further insight into these issues.

[Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, et al. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2017; 317(16):1642–1651.]

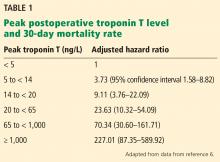

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study5 was an international, prospective cohort study that initially evaluated the association between MINS and the 30-day mortality rate using a non-high-sensitivity troponin T assay (Roche fourth-generation Elecsys TnT assay) in patients age 45 or older undergoing noncardiac surgery and requiring hospital admission for at least 1 night. After the first 15,000 patients, the study switched to the Roche fifth-generation assay, with measurements at 6 to 12 hours after surgery and on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

A 2017 analysis by Devereaux et al6 included only these later-enrolled patients and correlated their high-sensitivity troponin T levels with 30-day mortality rates. Patients with a level 14 ng/L or higher, the upper limit of normal in this study, were also assessed for ischemic symptoms and electrocardiographic changes. Although not required by the study, more than 7,800 patients had their troponin T levels measured before surgery, and the absolute change was also analyzed for an association with the 30-day mortality rate.

Findings. Of the 21,842 patients, about two-thirds underwent some form of major surgery; some of them had more than 1 type. A total of 1.2% of the patients died within 30 days of surgery.

Based on their analysis, the authors proposed that MINS be defined as:

- A postoperative troponin T level of 65 ng/L or higher, or

- A level in the range of 20 ng/L to less than 65 ng/L with an absolute increase from the preoperative level at least 5 ng/L, not attributable to a nonischemic cause.

Seventeen percent of the study patients met these criteria, and of these, 21.7% met the universal definition of myocardial infarction, although only 6.9% had symptoms of it.

Limitations. Only 40.4% of the patients had a preoperative high-sensitivity troponin T measurement for comparison, and in 13.8% of patients who had an elevated perioperative measurement, their preoperative value was the same or higher than their postoperative one. Thus, the incidence of MINS may have been overestimated if patients were otherwise not known to have troponin T elevations before surgery.

[Puelacher C, Lurati Buse G, Seeberger D, et al. Perioperative myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: incidence, mortality, and characterization. Circulation 2018; 137(12):1221–1232.]

Puelacher et al7 investigated the prevalence of MINS in 2,018 patients at increased cardiovascular risk (age ≥ 65, or age ≥ 45 with a history of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, or stroke) who underwent major noncardiac surgery (planned overnight stay ≥ 24 hours) at a university hospital in Switzerland. Patients had their troponin T measured with a high-sensitivity assay within 30 days before surgery and on postoperative days 1 and 2.

Instead of MINS, the investigators used the term “perioperative myocardial injury” (PMI), defined as an absolute increase in troponin T of at least 14 ng/L from before surgery to the peak postoperative reading. Similar to MINS, PMI did not require ischemic features, but in this study, noncardiac triggers (sepsis, stroke, or pulmonary embolus) were not excluded.

Findings. PMI occurred in 16% of surgeries, and of the patients with PMI, 6% had typical chest pain and 18% had any ischemic symptoms. Unlike in the POISE-2 study discussed above, PMI triggered an automatic referral to a cardiologist.

The unadjusted 30-day mortality rate was 8.9% among patients with PMI and 1.5% in those without. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed an adjusted hazard ratio for 30-day mortality of 2.7 (95% CI 1.5–4.8) for those with PMI vs without, and this difference persisted for at least 1 year.

In patients with PMI, the authors compared the 30-day mortality rate of those with no ischemic signs or symptoms (71% of the patients) with those who met the criteria for myocardial infarction and found no difference. Patients with PMI triggered by a noncardiac event had a worse prognosis than those with a presumed cardiac etiology.

Limitations. Despite the multivariate analysis that included adjustment for age, nonelective surgery, and Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), the increased risk associated with PMI could simply reflect higher risk at baseline. Although PMI resulted in automatic referral to a cardiologist, only 10% of patients eventually underwent coronary angiography; a similar percentage were discharged with additional medical therapy such as aspirin, a statin, or a beta-blocker. The effect of these interventions is not known.

Conclusions. MINS is common and has a strong association with mortality risk proportional to the degree of troponin T elevation using high-sensitivity assays, consistent with data from previous studies of earlier assays. Because the mechanism of MINS may differ from that of myocardial infarction, its prevention and treatment may differ, and it remains unclear how serial measurement in postoperative patients should change clinical practice.

The recently published Dabigatran in Patients With Myocardial Injury After Non-cardiac Surgery (MANAGE) trial8 suggests that dabigatran may reduce arterial and venous complications in patients with MINS, but the study had a number of limitations that may restrict the clinical applicability of this finding.

While awaiting further clinical outcomes data, pre- and postoperative troponin T measurement may be beneficial in higher-risk patients (such as those with cardiovascular disease or multiple RCRI risk factors) if the information will change perioperative management.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF HYPOTENSION OR BLOOD PRESSURE CONTROL?

Intraoperative hypotension is associated with organ ischemia, which may cause postoperative myocardial infarction, myocardial injury, and acute kidney injury.9 Traditional anesthesia practice is to maintain intraoperative blood pressure within 20% of the preoperative baseline, based on the notion that hypertensive patients require higher perfusion pressures.

[Futier E, Lefrant J-Y, Guinot P-G, et al. Effect of individualized vs standard blood pressure management strategies on postoperative organ dysfunction among high-risk patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318(14):1346–1357.]

Futier et al10 sought to address uncertainty in intraoperative and immediate postoperative management of systolic blood pressure. In this multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trial, 298 patients at increased risk of postoperative renal complications were randomized to blood pressure management that was either “individualized” (within 10% of resting systolic pressure) or “standard” (≥ 80 mm Hg or ≥ 40% of resting systolic pressure) from induction to 4 hours postoperatively.

Blood pressure was monitored using radial arterial lines and maintained using a combination of intravenous fluids, norepinephrine (the first-line agent for the individualized group), and ephedrine (in the standard treatment group only). The primary outcome was a composite of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and organ dysfunction affecting at least 1 organ system (cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, hematologic, or neurologic).

Findings. Data on the primary outcome were available for 292 of 298 patients enrolled. The mean age was 70 years, 15% were women, and 82% had previously diagnosed hypertension. Despite the requirement for an elevated risk of acute kidney injury, only 13% of the patients had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and the median was 88 mL/min/1.73 m2. Ninety-five percent of patients underwent abdominal surgery, and 50% of the surgeries were elective.

The mean systolic blood pressure was 123 mm Hg in the individualized treatment group compared with 116 mm Hg in the standard treatment group. Despite this small difference, 96% of individualized treatment patients received norepinephrine, compared with 26% in the standard treatment group.

The primary outcome of SIRS with organ dysfunction occurred in 38.1% of patients in the individualized treatment group and 51.7% of those in the standard treatment group. After adjusting for center, surgical urgency, surgical site, and acute kidney injury risk index, the relative risk of developing SIRS in those receiving individualized management was 0.73 (P = .02). Renal dysfunction (based on Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative criteria11) occurred in 32.7% of individualized treatment patients and 49% of standardized treatment patients.

Limitations of this study included differences in pharmacologic approach to maintain blood pressure in the 2 protocols (ephedrine and fluids vs norepinephrine) and a modest sample size.

Conclusions. Despite this, the difference in organ dysfunction was striking, with a number needed to treat of only 7 patients. This intervention extended 4 hours postoperatively, a time when many of these patients have left the postanesthesia care unit and have returned to hospitalist care on inpatient wards.

While optimal management of intraoperative and immediate postoperative blood pressure may not be settled, this study suggests that even mild relative hypotension may justify immediate action. Further studies may be useful to delineate high- and low-risk populations, the timing of greatest risk, and indications for intraarterial blood pressure monitoring.

[Salmasi V, Maheswari K, Yang D, et al. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology 2017; 126(1):47–65.]

This retrospective cohort study12 assessed the association between myocardial or kidney injury and absolute or relative thresholds of intraoperative mean arterial pressure. It included 57,315 adults who underwent inpatient noncardiac surgery, had a preoperative and at least 1 postoperative serum creatinine measurement within 7 days, and had blood pressure recorded in preoperative appointments within 6 months. Patients with chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and those on dialysis were excluded. The outcomes were MINS5 and acute kidney injury as defined by the Acute Kidney Injury Network.9

Findings. A mean arterial pressure below an absolute threshold of 65 mm Hg or a relative threshold of 20% lower than baseline value was associated with myocardial and kidney injury. At each threshold, prolonged periods of hypotension were associated with progressively increased risk.

An important conclusion of the study was that relative thresholds of mean arterial pressure were not any more predictive than absolute thresholds. Absolute thresholds are easier to use intraoperatively, especially when baseline values are not available. The authors did not find a clinically significant interaction between baseline blood pressure and the association of hypotension and myocardial and kidney injury.

Limitations included use of cardiac enzymes postoperatively to define MINS. Since these were not routinely collected, clinically silent myocardial injury may have been missed. Baseline blood pressure may have important implications in other forms of organ injury (ie, cerebral ischemia) that were not studied.

Summary. The lowest absolute mean arterial pressure is as predictive of postoperative myocardial and kidney injury as the relative pressure reduction, at least in patients with normal renal function. Limiting exposure to intraoperative hypotension is important. Baseline blood pressure values may have limited utility for intraoperative management.

In combination, these studies confirm that intraoperative hypotension is a predictor of postoperative organ dysfunction, but the definition and management remain unclear. While aggressive intraoperative management is likely beneficial, how to manage the antihypertensive therapy the patient has been taking as an outpatient when he or she comes into the hospital for surgery remains uncertain.

DOES PATENT FORAMEN OVALE INCREASE THE RISK OF STROKE?

Perioperative stroke is an uncommon, severe complication of noncardiac surgery. The pathophysiology has been better defined in cardiac than in noncardiac surgeries. In nonsurgical patients, patent foramen ovale (PFO) is associated with stroke, even in patients considered to be at low risk.13 Perioperative patients have additional risk for venous thromboembolism and may have periprocedural antithrombotic medications altered, increasing their risk of paradoxical embolism through the PFO.

[Ng PY, Ng AK, Subramaniam B, et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA 2018; 319(5):452–462.]

This retrospective cohort study of noncardiac surgery patients at 3 hospitals14 sought to determine the association of preoperatively diagnosed PFO with the risk of perioperative ischemic stroke identified by International Classification of Diseases diagnoses.

Of 150,198 patients, 1.0% had a preoperative diagnosis of PFO, and at baseline, those with PFO had significantly more comorbidities than those without PFO. Stroke occurred in 3.2% of patients with PFO vs 0.5% of those without. Patients known to have a PFO were much more likely to have cardiovascular and thromboembolic risk factors for stroke. In the adjusted analysis, the absolute risk difference between groups was 0.4% (95% CI 0.2–0.6%), with an estimated perioperative stroke risk of 5.9 per 1,000 in patients with known patent foramen ovale and 2.2 per 1,000 in those without. A diagnosis of PFO was also associated with increased risk of large-vessel-territory stroke and more severe neurologic deficit.

Further attempts to adjust for baseline risk factors and other potential bias, including a propensity score-matched cohort analysis and an analysis limited to patients who had echocardiography performed in the same healthcare system, still showed a higher risk of perioperative stroke among patients with preoperatively detected patent foramen ovale.

Limitations. The study was retrospective and observational, used administrative data, and had a low rate of PFO diagnosis (1%), compared with about 25% in population-based studies.15 Indications for preoperative echocardiography are unknown. In addition, the study specifically examined preoperatively diagnosed PFO, rather than including those diagnosed in the postoperative period.

Discussion. How does this study affect clinical practice? The absolute stroke risk was increased by 0.4% in patients with PFO compared with those without. Although this is a relatively small increase, millions of patients undergo noncardiac surgery annually. The risks of therapeutic anticoagulation or PFO closure are likely too high in this context; however, clinicians may approach the perioperative management of antiplatelet agents and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients with known PFO with additional caution.

HOW DOES TIMING OF EMERGENCY SURGERY AFTER PRIOR STROKE AFFECT OUTCOMES?

A history of stroke or transient ischemic attack is a known risk factor for perioperative vascular complications. A recent large cohort study demonstrated that a history of stroke within 9 months of elective surgery was associated with increased adverse outcomes.16 Little is known, however, of the perioperative risk in patients with a history of stroke who undergo emergency surgery.

[Christiansen MN, Andersson C, Gislason GH, et al. Risks of cardiovascular adverse events and death in patients with previous stroke undergoing emergency noncardiac, nonintracranial surgery: the importance of operative timing. Anesthesiology 2017; 127(1):9–19.]

In this study,17 all emergency noncardiac and nonintracranial surgeries from 2005 to 2011 were analyzed using multiple national patient registries in Denmark according to time elapsed between previous stroke and surgery. Primary outcomes were 30-day all-cause mortality and 30-day major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as nonfatal ischemic stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death. Statistical analysis to assess the risk of adverse outcomes included logistic regression models, spline analyses, and propensity-score matching.

Findings. The authors identified 146,694 emergency surgeries, with 7,861 patients (5.4%) having had a previous stroke (transient ischemic attacks and hemorrhagic strokes were not included). Rates of postoperative stroke were as follows:

- 9.9% in patents with a history of ischemic stroke within 3 months of surgery

- 2.8% in patients with a history of stroke 3 to 9 months before surgery

- 0.3% in patients with no previous stroke.

The risk plateaued when the time between stroke and surgery exceeded 4 to 5 months.15

Interestingly, in patients who underwent emergency surgery within 14 days of stroke, the risk of MACE was significantly lower immediately after surgery (1–3 days after stroke) compared with surgery that took place 4 to 14 days after stroke. The authors hypothesized that because cerebral autoregulation does not become compromised until approximately 5 days after a stroke, the risk was lower 1 to 3 days after surgery and increased thereafter.

Limitations of this study included the possibility of residual confounding, given its retrospective design using administrative data, not accounting for preoperative antithrombotic and anticoagulation therapy, and lack of information regarding the etiology of recurrent stroke (eg, thromboembolic, atherothrombotic, hypoperfusion).

Conclusions. Although it would be impractical to postpone emergency surgery in a patient who recently had a stroke, this study shows that the incidence rates of postoperative recurrent stroke and MACE are high. Therefore, it is important that the patient and perioperative team be aware of the risk. Further research is needed to confirm these estimates of postoperative adverse events in more diverse patient populations.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(16):1494–1503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401105

- Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244. doi:10.7326/M17-2341

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 130(24):2215–2245. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000105

- Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Ramakrishna H, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with noncardiac surgery. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2(2):181–187. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4792

- Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology 2014; 120(3):564–578. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113

- Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, et al. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2017; 317(16):1642–1651. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.4360

- Puelacher C, Lurati Buse G, Seeberger D, et al. Perioperative myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: incidence, mortality, and characterization. Circulation 2018; 137(12):1221–1232. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030114

- Devereaux PJ, Duceppe E, Guyatt G, et al. Dabigatran in patients with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MANAGE): an international, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 391(10137):2325–2334. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30832-8

- Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology 2013; 119(3):507–515. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10e26

- Futier E, Lefrant JY, Guinot PG, et al. Effect of individualized vs standard blood pressure management strategies on postoperative organ dysfunction among high-risk patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318(14):1346–1357. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.14172

- Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) group. Crit Care 2004; 8:R204. doi:10.1186/cc2872

- Salmasi V, Maheswari K, Yang D, et al. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology 2017; 126(1):47–65. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001432

- Lechat P, Mas JL, Lascault G, et al. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med 1988; 318(18):1148–1152. doi:10.1056/NEJM198805053181802

- Ng PY, Ng AK, Subramaniam B, et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA 2018; 319(5):452–462. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.21899

- Meissner I, Whisnant JP, Khandheria BK, et al. Prevalence of potential risk factors for stroke assessed by transesophageal echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography: the SPARC study. Stroke Prevention: Assessment of Risk in a Community. Mayo Clin Proc 1999; 74(9):862–869. pmid:10488786

- Jørgensen ME, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason GH, et al. Time elapsed after ischemic stroke and risk of adverse cardiovascular events and mortality following elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2014; 312:269–277. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.8165

- Christiansen MN, Andersson C, Gislason GH, et al. Risks of cardiovascular adverse events and death in patients with previous stroke undergoing emergency noncardiac, nonintracranial surgery: the importance of operative timing. Anesthesiology 2017; 127(1):9–19. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001685

A plethora of studies are under way in the field of perioperative medicine. As a result, evidence-based care of surgical patients is evolving at an exponential rate.

We performed a literature search and, using consensus, identified recent articles we believe will have a great impact on perioperative cardiovascular medicine. These articles report studies that were presented at national meetings in 2018, including the Perioperative Medicine Summit, Society of General Internal Medicine, and Society of Hospital Medicine. These articles are grouped under 5 questions that will help guide clinical practice in perioperative cardiovascular medicine.

SHOULD ASPIRIN BE CONTINUED PERIOPERATIVELY IN PATIENTS WITH A CORONARY STENT?

The Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2 (POISE-2) trial1 found that giving aspirin before surgery and throughout the early postoperative period had no significant effect on the rate of a composite of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction; moreover, aspirin increased the risk of major bleeding. However, many experts felt uncomfortable stopping aspirin preoperatively in patients taking it for secondary prophylaxis, particularly patients with a coronary stent.

[Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244.]

This post hoc subgroup analysis2 of POISE-2 evaluated the benefit and harm of perioperative aspirin in patients who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, more than 90% of whom had received a stent. Patients were age 45 or older with atherosclerotic heart disease or risk factors for it who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention and were now undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Patients who had received a bare-metal stent within the previous 6 weeks or a drug-eluting stent within 12 months before surgery were excluded because guidelines at that time said to continue dual antiplatelet therapy for that long. Recommendations have since changed; the optimal duration for dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents is now 6 months. Second-generation drug-eluting stents pose a lower risk of stent thrombosis and require a shorter duration of dual antiplatelet therapy than first-generation drug-eluting stents. Approximately 25% of the percutaneous coronary intervention subgroup had a drug-eluting stent, but the authors did not specify the type of drug-eluting stent.

The post hoc analysis2 included a subgroup of 234 of 4,998 patients receiving aspirin and 236 of 5,012 patients receiving placebo initiated within 4 hours before surgery and continued postoperatively. The primary outcome measured was the rate of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction within 30 days after surgery, and bleeding was a secondary outcome.

Findings. Although the overall POISE-2 study found no benefit from aspirin, in the subgroup who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, aspirin significantly reduced the risk of the primary outcome, which occurred in 6% vs 11.5% of the patients:

- Absolute risk reduction 5.5% (95% confidence interval 0.4%–10.5%)

- Hazard ratio 0.50 (0.26–0.95).

The reduction was primarily due to fewer myocardial infarctions:

- Absolute risk reduction 5.9% (1.0%–10.8%)

- Hazard ratio 0.44 (0.22–0.87).

The type of stent had no effect on the primary outcome, although this subgroup analysis had limited power. In the nonpercutaneous coronary intervention subgroup, there was no significant difference in outcomes between the aspirin and placebo groups. This subgroup analysis was underpowered to evaluate the effect of aspirin on the composite of major and life-threatening bleeding in patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention, which was reported as “uncertain” due to wide confidence intervals (absolute risk increase 1.3%, 95% confidence interval –2.6% to 5.2%), but the increased risk of major or life-threatening bleeding with aspirin demonstrated in the overall POISE-2 study population likely applies:

- Absolute risk increase 0.8% (0.1%–1.6%)

- Hazard ratio 1.22 (1.01–1.48).

Limitations. This was a nonspecified subgroup analysis that was underpowered and had a relatively small sample size with few events.

Conclusion. In the absence of a very high bleeding risk, continuing aspirin perioperatively in patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery is more likely to result in benefit than harm. This finding is in agreement with current recommendations from the American College Cardiology and American Heart Association (class I; level of evidence C).3

WHAT IS THE INCIDENCE OF MINS? IS MEASURING TROPONIN USEFUL?

Despite advances in anesthesia and surgical techniques, about 1% of patients over age 45 die within 30 days of noncardiac surgery.4 Studies have demonstrated a high mortality rate in patients who experience myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery (MINS), defined as elevations of troponin T with or without ischemic symptoms or electrocardiographic changes.5 Most of these studies used earlier, “non-high-sensitivity” troponin T assays. Fifth-generation, highly sensitive troponin T assays are now available that can detect troponin T at lower concentrations, but their utility in predicting postoperative outcomes remains uncertain. Two recent studies provide further insight into these issues.

[Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, et al. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2017; 317(16):1642–1651.]

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study5 was an international, prospective cohort study that initially evaluated the association between MINS and the 30-day mortality rate using a non-high-sensitivity troponin T assay (Roche fourth-generation Elecsys TnT assay) in patients age 45 or older undergoing noncardiac surgery and requiring hospital admission for at least 1 night. After the first 15,000 patients, the study switched to the Roche fifth-generation assay, with measurements at 6 to 12 hours after surgery and on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

A 2017 analysis by Devereaux et al6 included only these later-enrolled patients and correlated their high-sensitivity troponin T levels with 30-day mortality rates. Patients with a level 14 ng/L or higher, the upper limit of normal in this study, were also assessed for ischemic symptoms and electrocardiographic changes. Although not required by the study, more than 7,800 patients had their troponin T levels measured before surgery, and the absolute change was also analyzed for an association with the 30-day mortality rate.

Findings. Of the 21,842 patients, about two-thirds underwent some form of major surgery; some of them had more than 1 type. A total of 1.2% of the patients died within 30 days of surgery.

Based on their analysis, the authors proposed that MINS be defined as:

- A postoperative troponin T level of 65 ng/L or higher, or

- A level in the range of 20 ng/L to less than 65 ng/L with an absolute increase from the preoperative level at least 5 ng/L, not attributable to a nonischemic cause.

Seventeen percent of the study patients met these criteria, and of these, 21.7% met the universal definition of myocardial infarction, although only 6.9% had symptoms of it.

Limitations. Only 40.4% of the patients had a preoperative high-sensitivity troponin T measurement for comparison, and in 13.8% of patients who had an elevated perioperative measurement, their preoperative value was the same or higher than their postoperative one. Thus, the incidence of MINS may have been overestimated if patients were otherwise not known to have troponin T elevations before surgery.

[Puelacher C, Lurati Buse G, Seeberger D, et al. Perioperative myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: incidence, mortality, and characterization. Circulation 2018; 137(12):1221–1232.]

Puelacher et al7 investigated the prevalence of MINS in 2,018 patients at increased cardiovascular risk (age ≥ 65, or age ≥ 45 with a history of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, or stroke) who underwent major noncardiac surgery (planned overnight stay ≥ 24 hours) at a university hospital in Switzerland. Patients had their troponin T measured with a high-sensitivity assay within 30 days before surgery and on postoperative days 1 and 2.

Instead of MINS, the investigators used the term “perioperative myocardial injury” (PMI), defined as an absolute increase in troponin T of at least 14 ng/L from before surgery to the peak postoperative reading. Similar to MINS, PMI did not require ischemic features, but in this study, noncardiac triggers (sepsis, stroke, or pulmonary embolus) were not excluded.

Findings. PMI occurred in 16% of surgeries, and of the patients with PMI, 6% had typical chest pain and 18% had any ischemic symptoms. Unlike in the POISE-2 study discussed above, PMI triggered an automatic referral to a cardiologist.

The unadjusted 30-day mortality rate was 8.9% among patients with PMI and 1.5% in those without. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed an adjusted hazard ratio for 30-day mortality of 2.7 (95% CI 1.5–4.8) for those with PMI vs without, and this difference persisted for at least 1 year.

In patients with PMI, the authors compared the 30-day mortality rate of those with no ischemic signs or symptoms (71% of the patients) with those who met the criteria for myocardial infarction and found no difference. Patients with PMI triggered by a noncardiac event had a worse prognosis than those with a presumed cardiac etiology.

Limitations. Despite the multivariate analysis that included adjustment for age, nonelective surgery, and Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), the increased risk associated with PMI could simply reflect higher risk at baseline. Although PMI resulted in automatic referral to a cardiologist, only 10% of patients eventually underwent coronary angiography; a similar percentage were discharged with additional medical therapy such as aspirin, a statin, or a beta-blocker. The effect of these interventions is not known.

Conclusions. MINS is common and has a strong association with mortality risk proportional to the degree of troponin T elevation using high-sensitivity assays, consistent with data from previous studies of earlier assays. Because the mechanism of MINS may differ from that of myocardial infarction, its prevention and treatment may differ, and it remains unclear how serial measurement in postoperative patients should change clinical practice.

The recently published Dabigatran in Patients With Myocardial Injury After Non-cardiac Surgery (MANAGE) trial8 suggests that dabigatran may reduce arterial and venous complications in patients with MINS, but the study had a number of limitations that may restrict the clinical applicability of this finding.

While awaiting further clinical outcomes data, pre- and postoperative troponin T measurement may be beneficial in higher-risk patients (such as those with cardiovascular disease or multiple RCRI risk factors) if the information will change perioperative management.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF HYPOTENSION OR BLOOD PRESSURE CONTROL?

Intraoperative hypotension is associated with organ ischemia, which may cause postoperative myocardial infarction, myocardial injury, and acute kidney injury.9 Traditional anesthesia practice is to maintain intraoperative blood pressure within 20% of the preoperative baseline, based on the notion that hypertensive patients require higher perfusion pressures.

[Futier E, Lefrant J-Y, Guinot P-G, et al. Effect of individualized vs standard blood pressure management strategies on postoperative organ dysfunction among high-risk patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318(14):1346–1357.]

Futier et al10 sought to address uncertainty in intraoperative and immediate postoperative management of systolic blood pressure. In this multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trial, 298 patients at increased risk of postoperative renal complications were randomized to blood pressure management that was either “individualized” (within 10% of resting systolic pressure) or “standard” (≥ 80 mm Hg or ≥ 40% of resting systolic pressure) from induction to 4 hours postoperatively.

Blood pressure was monitored using radial arterial lines and maintained using a combination of intravenous fluids, norepinephrine (the first-line agent for the individualized group), and ephedrine (in the standard treatment group only). The primary outcome was a composite of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and organ dysfunction affecting at least 1 organ system (cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, hematologic, or neurologic).

Findings. Data on the primary outcome were available for 292 of 298 patients enrolled. The mean age was 70 years, 15% were women, and 82% had previously diagnosed hypertension. Despite the requirement for an elevated risk of acute kidney injury, only 13% of the patients had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and the median was 88 mL/min/1.73 m2. Ninety-five percent of patients underwent abdominal surgery, and 50% of the surgeries were elective.

The mean systolic blood pressure was 123 mm Hg in the individualized treatment group compared with 116 mm Hg in the standard treatment group. Despite this small difference, 96% of individualized treatment patients received norepinephrine, compared with 26% in the standard treatment group.

The primary outcome of SIRS with organ dysfunction occurred in 38.1% of patients in the individualized treatment group and 51.7% of those in the standard treatment group. After adjusting for center, surgical urgency, surgical site, and acute kidney injury risk index, the relative risk of developing SIRS in those receiving individualized management was 0.73 (P = .02). Renal dysfunction (based on Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative criteria11) occurred in 32.7% of individualized treatment patients and 49% of standardized treatment patients.

Limitations of this study included differences in pharmacologic approach to maintain blood pressure in the 2 protocols (ephedrine and fluids vs norepinephrine) and a modest sample size.

Conclusions. Despite this, the difference in organ dysfunction was striking, with a number needed to treat of only 7 patients. This intervention extended 4 hours postoperatively, a time when many of these patients have left the postanesthesia care unit and have returned to hospitalist care on inpatient wards.

While optimal management of intraoperative and immediate postoperative blood pressure may not be settled, this study suggests that even mild relative hypotension may justify immediate action. Further studies may be useful to delineate high- and low-risk populations, the timing of greatest risk, and indications for intraarterial blood pressure monitoring.

[Salmasi V, Maheswari K, Yang D, et al. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology 2017; 126(1):47–65.]

This retrospective cohort study12 assessed the association between myocardial or kidney injury and absolute or relative thresholds of intraoperative mean arterial pressure. It included 57,315 adults who underwent inpatient noncardiac surgery, had a preoperative and at least 1 postoperative serum creatinine measurement within 7 days, and had blood pressure recorded in preoperative appointments within 6 months. Patients with chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and those on dialysis were excluded. The outcomes were MINS5 and acute kidney injury as defined by the Acute Kidney Injury Network.9

Findings. A mean arterial pressure below an absolute threshold of 65 mm Hg or a relative threshold of 20% lower than baseline value was associated with myocardial and kidney injury. At each threshold, prolonged periods of hypotension were associated with progressively increased risk.

An important conclusion of the study was that relative thresholds of mean arterial pressure were not any more predictive than absolute thresholds. Absolute thresholds are easier to use intraoperatively, especially when baseline values are not available. The authors did not find a clinically significant interaction between baseline blood pressure and the association of hypotension and myocardial and kidney injury.

Limitations included use of cardiac enzymes postoperatively to define MINS. Since these were not routinely collected, clinically silent myocardial injury may have been missed. Baseline blood pressure may have important implications in other forms of organ injury (ie, cerebral ischemia) that were not studied.

Summary. The lowest absolute mean arterial pressure is as predictive of postoperative myocardial and kidney injury as the relative pressure reduction, at least in patients with normal renal function. Limiting exposure to intraoperative hypotension is important. Baseline blood pressure values may have limited utility for intraoperative management.

In combination, these studies confirm that intraoperative hypotension is a predictor of postoperative organ dysfunction, but the definition and management remain unclear. While aggressive intraoperative management is likely beneficial, how to manage the antihypertensive therapy the patient has been taking as an outpatient when he or she comes into the hospital for surgery remains uncertain.

DOES PATENT FORAMEN OVALE INCREASE THE RISK OF STROKE?

Perioperative stroke is an uncommon, severe complication of noncardiac surgery. The pathophysiology has been better defined in cardiac than in noncardiac surgeries. In nonsurgical patients, patent foramen ovale (PFO) is associated with stroke, even in patients considered to be at low risk.13 Perioperative patients have additional risk for venous thromboembolism and may have periprocedural antithrombotic medications altered, increasing their risk of paradoxical embolism through the PFO.

[Ng PY, Ng AK, Subramaniam B, et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA 2018; 319(5):452–462.]

This retrospective cohort study of noncardiac surgery patients at 3 hospitals14 sought to determine the association of preoperatively diagnosed PFO with the risk of perioperative ischemic stroke identified by International Classification of Diseases diagnoses.

Of 150,198 patients, 1.0% had a preoperative diagnosis of PFO, and at baseline, those with PFO had significantly more comorbidities than those without PFO. Stroke occurred in 3.2% of patients with PFO vs 0.5% of those without. Patients known to have a PFO were much more likely to have cardiovascular and thromboembolic risk factors for stroke. In the adjusted analysis, the absolute risk difference between groups was 0.4% (95% CI 0.2–0.6%), with an estimated perioperative stroke risk of 5.9 per 1,000 in patients with known patent foramen ovale and 2.2 per 1,000 in those without. A diagnosis of PFO was also associated with increased risk of large-vessel-territory stroke and more severe neurologic deficit.

Further attempts to adjust for baseline risk factors and other potential bias, including a propensity score-matched cohort analysis and an analysis limited to patients who had echocardiography performed in the same healthcare system, still showed a higher risk of perioperative stroke among patients with preoperatively detected patent foramen ovale.

Limitations. The study was retrospective and observational, used administrative data, and had a low rate of PFO diagnosis (1%), compared with about 25% in population-based studies.15 Indications for preoperative echocardiography are unknown. In addition, the study specifically examined preoperatively diagnosed PFO, rather than including those diagnosed in the postoperative period.

Discussion. How does this study affect clinical practice? The absolute stroke risk was increased by 0.4% in patients with PFO compared with those without. Although this is a relatively small increase, millions of patients undergo noncardiac surgery annually. The risks of therapeutic anticoagulation or PFO closure are likely too high in this context; however, clinicians may approach the perioperative management of antiplatelet agents and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients with known PFO with additional caution.

HOW DOES TIMING OF EMERGENCY SURGERY AFTER PRIOR STROKE AFFECT OUTCOMES?

A history of stroke or transient ischemic attack is a known risk factor for perioperative vascular complications. A recent large cohort study demonstrated that a history of stroke within 9 months of elective surgery was associated with increased adverse outcomes.16 Little is known, however, of the perioperative risk in patients with a history of stroke who undergo emergency surgery.

[Christiansen MN, Andersson C, Gislason GH, et al. Risks of cardiovascular adverse events and death in patients with previous stroke undergoing emergency noncardiac, nonintracranial surgery: the importance of operative timing. Anesthesiology 2017; 127(1):9–19.]

In this study,17 all emergency noncardiac and nonintracranial surgeries from 2005 to 2011 were analyzed using multiple national patient registries in Denmark according to time elapsed between previous stroke and surgery. Primary outcomes were 30-day all-cause mortality and 30-day major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as nonfatal ischemic stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death. Statistical analysis to assess the risk of adverse outcomes included logistic regression models, spline analyses, and propensity-score matching.

Findings. The authors identified 146,694 emergency surgeries, with 7,861 patients (5.4%) having had a previous stroke (transient ischemic attacks and hemorrhagic strokes were not included). Rates of postoperative stroke were as follows:

- 9.9% in patents with a history of ischemic stroke within 3 months of surgery

- 2.8% in patients with a history of stroke 3 to 9 months before surgery

- 0.3% in patients with no previous stroke.

The risk plateaued when the time between stroke and surgery exceeded 4 to 5 months.15

Interestingly, in patients who underwent emergency surgery within 14 days of stroke, the risk of MACE was significantly lower immediately after surgery (1–3 days after stroke) compared with surgery that took place 4 to 14 days after stroke. The authors hypothesized that because cerebral autoregulation does not become compromised until approximately 5 days after a stroke, the risk was lower 1 to 3 days after surgery and increased thereafter.

Limitations of this study included the possibility of residual confounding, given its retrospective design using administrative data, not accounting for preoperative antithrombotic and anticoagulation therapy, and lack of information regarding the etiology of recurrent stroke (eg, thromboembolic, atherothrombotic, hypoperfusion).

Conclusions. Although it would be impractical to postpone emergency surgery in a patient who recently had a stroke, this study shows that the incidence rates of postoperative recurrent stroke and MACE are high. Therefore, it is important that the patient and perioperative team be aware of the risk. Further research is needed to confirm these estimates of postoperative adverse events in more diverse patient populations.

A plethora of studies are under way in the field of perioperative medicine. As a result, evidence-based care of surgical patients is evolving at an exponential rate.

We performed a literature search and, using consensus, identified recent articles we believe will have a great impact on perioperative cardiovascular medicine. These articles report studies that were presented at national meetings in 2018, including the Perioperative Medicine Summit, Society of General Internal Medicine, and Society of Hospital Medicine. These articles are grouped under 5 questions that will help guide clinical practice in perioperative cardiovascular medicine.

SHOULD ASPIRIN BE CONTINUED PERIOPERATIVELY IN PATIENTS WITH A CORONARY STENT?

The Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2 (POISE-2) trial1 found that giving aspirin before surgery and throughout the early postoperative period had no significant effect on the rate of a composite of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction; moreover, aspirin increased the risk of major bleeding. However, many experts felt uncomfortable stopping aspirin preoperatively in patients taking it for secondary prophylaxis, particularly patients with a coronary stent.

[Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244.]

This post hoc subgroup analysis2 of POISE-2 evaluated the benefit and harm of perioperative aspirin in patients who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, more than 90% of whom had received a stent. Patients were age 45 or older with atherosclerotic heart disease or risk factors for it who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention and were now undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Patients who had received a bare-metal stent within the previous 6 weeks or a drug-eluting stent within 12 months before surgery were excluded because guidelines at that time said to continue dual antiplatelet therapy for that long. Recommendations have since changed; the optimal duration for dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents is now 6 months. Second-generation drug-eluting stents pose a lower risk of stent thrombosis and require a shorter duration of dual antiplatelet therapy than first-generation drug-eluting stents. Approximately 25% of the percutaneous coronary intervention subgroup had a drug-eluting stent, but the authors did not specify the type of drug-eluting stent.

The post hoc analysis2 included a subgroup of 234 of 4,998 patients receiving aspirin and 236 of 5,012 patients receiving placebo initiated within 4 hours before surgery and continued postoperatively. The primary outcome measured was the rate of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction within 30 days after surgery, and bleeding was a secondary outcome.

Findings. Although the overall POISE-2 study found no benefit from aspirin, in the subgroup who had previously undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, aspirin significantly reduced the risk of the primary outcome, which occurred in 6% vs 11.5% of the patients:

- Absolute risk reduction 5.5% (95% confidence interval 0.4%–10.5%)

- Hazard ratio 0.50 (0.26–0.95).

The reduction was primarily due to fewer myocardial infarctions:

- Absolute risk reduction 5.9% (1.0%–10.8%)

- Hazard ratio 0.44 (0.22–0.87).

The type of stent had no effect on the primary outcome, although this subgroup analysis had limited power. In the nonpercutaneous coronary intervention subgroup, there was no significant difference in outcomes between the aspirin and placebo groups. This subgroup analysis was underpowered to evaluate the effect of aspirin on the composite of major and life-threatening bleeding in patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention, which was reported as “uncertain” due to wide confidence intervals (absolute risk increase 1.3%, 95% confidence interval –2.6% to 5.2%), but the increased risk of major or life-threatening bleeding with aspirin demonstrated in the overall POISE-2 study population likely applies:

- Absolute risk increase 0.8% (0.1%–1.6%)

- Hazard ratio 1.22 (1.01–1.48).

Limitations. This was a nonspecified subgroup analysis that was underpowered and had a relatively small sample size with few events.

Conclusion. In the absence of a very high bleeding risk, continuing aspirin perioperatively in patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery is more likely to result in benefit than harm. This finding is in agreement with current recommendations from the American College Cardiology and American Heart Association (class I; level of evidence C).3

WHAT IS THE INCIDENCE OF MINS? IS MEASURING TROPONIN USEFUL?

Despite advances in anesthesia and surgical techniques, about 1% of patients over age 45 die within 30 days of noncardiac surgery.4 Studies have demonstrated a high mortality rate in patients who experience myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery (MINS), defined as elevations of troponin T with or without ischemic symptoms or electrocardiographic changes.5 Most of these studies used earlier, “non-high-sensitivity” troponin T assays. Fifth-generation, highly sensitive troponin T assays are now available that can detect troponin T at lower concentrations, but their utility in predicting postoperative outcomes remains uncertain. Two recent studies provide further insight into these issues.

[Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, et al. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2017; 317(16):1642–1651.]

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study5 was an international, prospective cohort study that initially evaluated the association between MINS and the 30-day mortality rate using a non-high-sensitivity troponin T assay (Roche fourth-generation Elecsys TnT assay) in patients age 45 or older undergoing noncardiac surgery and requiring hospital admission for at least 1 night. After the first 15,000 patients, the study switched to the Roche fifth-generation assay, with measurements at 6 to 12 hours after surgery and on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

A 2017 analysis by Devereaux et al6 included only these later-enrolled patients and correlated their high-sensitivity troponin T levels with 30-day mortality rates. Patients with a level 14 ng/L or higher, the upper limit of normal in this study, were also assessed for ischemic symptoms and electrocardiographic changes. Although not required by the study, more than 7,800 patients had their troponin T levels measured before surgery, and the absolute change was also analyzed for an association with the 30-day mortality rate.

Findings. Of the 21,842 patients, about two-thirds underwent some form of major surgery; some of them had more than 1 type. A total of 1.2% of the patients died within 30 days of surgery.

Based on their analysis, the authors proposed that MINS be defined as:

- A postoperative troponin T level of 65 ng/L or higher, or

- A level in the range of 20 ng/L to less than 65 ng/L with an absolute increase from the preoperative level at least 5 ng/L, not attributable to a nonischemic cause.

Seventeen percent of the study patients met these criteria, and of these, 21.7% met the universal definition of myocardial infarction, although only 6.9% had symptoms of it.

Limitations. Only 40.4% of the patients had a preoperative high-sensitivity troponin T measurement for comparison, and in 13.8% of patients who had an elevated perioperative measurement, their preoperative value was the same or higher than their postoperative one. Thus, the incidence of MINS may have been overestimated if patients were otherwise not known to have troponin T elevations before surgery.

[Puelacher C, Lurati Buse G, Seeberger D, et al. Perioperative myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: incidence, mortality, and characterization. Circulation 2018; 137(12):1221–1232.]

Puelacher et al7 investigated the prevalence of MINS in 2,018 patients at increased cardiovascular risk (age ≥ 65, or age ≥ 45 with a history of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, or stroke) who underwent major noncardiac surgery (planned overnight stay ≥ 24 hours) at a university hospital in Switzerland. Patients had their troponin T measured with a high-sensitivity assay within 30 days before surgery and on postoperative days 1 and 2.

Instead of MINS, the investigators used the term “perioperative myocardial injury” (PMI), defined as an absolute increase in troponin T of at least 14 ng/L from before surgery to the peak postoperative reading. Similar to MINS, PMI did not require ischemic features, but in this study, noncardiac triggers (sepsis, stroke, or pulmonary embolus) were not excluded.

Findings. PMI occurred in 16% of surgeries, and of the patients with PMI, 6% had typical chest pain and 18% had any ischemic symptoms. Unlike in the POISE-2 study discussed above, PMI triggered an automatic referral to a cardiologist.

The unadjusted 30-day mortality rate was 8.9% among patients with PMI and 1.5% in those without. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed an adjusted hazard ratio for 30-day mortality of 2.7 (95% CI 1.5–4.8) for those with PMI vs without, and this difference persisted for at least 1 year.

In patients with PMI, the authors compared the 30-day mortality rate of those with no ischemic signs or symptoms (71% of the patients) with those who met the criteria for myocardial infarction and found no difference. Patients with PMI triggered by a noncardiac event had a worse prognosis than those with a presumed cardiac etiology.

Limitations. Despite the multivariate analysis that included adjustment for age, nonelective surgery, and Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), the increased risk associated with PMI could simply reflect higher risk at baseline. Although PMI resulted in automatic referral to a cardiologist, only 10% of patients eventually underwent coronary angiography; a similar percentage were discharged with additional medical therapy such as aspirin, a statin, or a beta-blocker. The effect of these interventions is not known.

Conclusions. MINS is common and has a strong association with mortality risk proportional to the degree of troponin T elevation using high-sensitivity assays, consistent with data from previous studies of earlier assays. Because the mechanism of MINS may differ from that of myocardial infarction, its prevention and treatment may differ, and it remains unclear how serial measurement in postoperative patients should change clinical practice.

The recently published Dabigatran in Patients With Myocardial Injury After Non-cardiac Surgery (MANAGE) trial8 suggests that dabigatran may reduce arterial and venous complications in patients with MINS, but the study had a number of limitations that may restrict the clinical applicability of this finding.

While awaiting further clinical outcomes data, pre- and postoperative troponin T measurement may be beneficial in higher-risk patients (such as those with cardiovascular disease or multiple RCRI risk factors) if the information will change perioperative management.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF HYPOTENSION OR BLOOD PRESSURE CONTROL?

Intraoperative hypotension is associated with organ ischemia, which may cause postoperative myocardial infarction, myocardial injury, and acute kidney injury.9 Traditional anesthesia practice is to maintain intraoperative blood pressure within 20% of the preoperative baseline, based on the notion that hypertensive patients require higher perfusion pressures.

[Futier E, Lefrant J-Y, Guinot P-G, et al. Effect of individualized vs standard blood pressure management strategies on postoperative organ dysfunction among high-risk patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318(14):1346–1357.]

Futier et al10 sought to address uncertainty in intraoperative and immediate postoperative management of systolic blood pressure. In this multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trial, 298 patients at increased risk of postoperative renal complications were randomized to blood pressure management that was either “individualized” (within 10% of resting systolic pressure) or “standard” (≥ 80 mm Hg or ≥ 40% of resting systolic pressure) from induction to 4 hours postoperatively.

Blood pressure was monitored using radial arterial lines and maintained using a combination of intravenous fluids, norepinephrine (the first-line agent for the individualized group), and ephedrine (in the standard treatment group only). The primary outcome was a composite of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and organ dysfunction affecting at least 1 organ system (cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, hematologic, or neurologic).

Findings. Data on the primary outcome were available for 292 of 298 patients enrolled. The mean age was 70 years, 15% were women, and 82% had previously diagnosed hypertension. Despite the requirement for an elevated risk of acute kidney injury, only 13% of the patients had a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and the median was 88 mL/min/1.73 m2. Ninety-five percent of patients underwent abdominal surgery, and 50% of the surgeries were elective.

The mean systolic blood pressure was 123 mm Hg in the individualized treatment group compared with 116 mm Hg in the standard treatment group. Despite this small difference, 96% of individualized treatment patients received norepinephrine, compared with 26% in the standard treatment group.

The primary outcome of SIRS with organ dysfunction occurred in 38.1% of patients in the individualized treatment group and 51.7% of those in the standard treatment group. After adjusting for center, surgical urgency, surgical site, and acute kidney injury risk index, the relative risk of developing SIRS in those receiving individualized management was 0.73 (P = .02). Renal dysfunction (based on Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative criteria11) occurred in 32.7% of individualized treatment patients and 49% of standardized treatment patients.

Limitations of this study included differences in pharmacologic approach to maintain blood pressure in the 2 protocols (ephedrine and fluids vs norepinephrine) and a modest sample size.

Conclusions. Despite this, the difference in organ dysfunction was striking, with a number needed to treat of only 7 patients. This intervention extended 4 hours postoperatively, a time when many of these patients have left the postanesthesia care unit and have returned to hospitalist care on inpatient wards.

While optimal management of intraoperative and immediate postoperative blood pressure may not be settled, this study suggests that even mild relative hypotension may justify immediate action. Further studies may be useful to delineate high- and low-risk populations, the timing of greatest risk, and indications for intraarterial blood pressure monitoring.

[Salmasi V, Maheswari K, Yang D, et al. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology 2017; 126(1):47–65.]

This retrospective cohort study12 assessed the association between myocardial or kidney injury and absolute or relative thresholds of intraoperative mean arterial pressure. It included 57,315 adults who underwent inpatient noncardiac surgery, had a preoperative and at least 1 postoperative serum creatinine measurement within 7 days, and had blood pressure recorded in preoperative appointments within 6 months. Patients with chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and those on dialysis were excluded. The outcomes were MINS5 and acute kidney injury as defined by the Acute Kidney Injury Network.9

Findings. A mean arterial pressure below an absolute threshold of 65 mm Hg or a relative threshold of 20% lower than baseline value was associated with myocardial and kidney injury. At each threshold, prolonged periods of hypotension were associated with progressively increased risk.

An important conclusion of the study was that relative thresholds of mean arterial pressure were not any more predictive than absolute thresholds. Absolute thresholds are easier to use intraoperatively, especially when baseline values are not available. The authors did not find a clinically significant interaction between baseline blood pressure and the association of hypotension and myocardial and kidney injury.

Limitations included use of cardiac enzymes postoperatively to define MINS. Since these were not routinely collected, clinically silent myocardial injury may have been missed. Baseline blood pressure may have important implications in other forms of organ injury (ie, cerebral ischemia) that were not studied.

Summary. The lowest absolute mean arterial pressure is as predictive of postoperative myocardial and kidney injury as the relative pressure reduction, at least in patients with normal renal function. Limiting exposure to intraoperative hypotension is important. Baseline blood pressure values may have limited utility for intraoperative management.

In combination, these studies confirm that intraoperative hypotension is a predictor of postoperative organ dysfunction, but the definition and management remain unclear. While aggressive intraoperative management is likely beneficial, how to manage the antihypertensive therapy the patient has been taking as an outpatient when he or she comes into the hospital for surgery remains uncertain.

DOES PATENT FORAMEN OVALE INCREASE THE RISK OF STROKE?

Perioperative stroke is an uncommon, severe complication of noncardiac surgery. The pathophysiology has been better defined in cardiac than in noncardiac surgeries. In nonsurgical patients, patent foramen ovale (PFO) is associated with stroke, even in patients considered to be at low risk.13 Perioperative patients have additional risk for venous thromboembolism and may have periprocedural antithrombotic medications altered, increasing their risk of paradoxical embolism through the PFO.

[Ng PY, Ng AK, Subramaniam B, et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA 2018; 319(5):452–462.]

This retrospective cohort study of noncardiac surgery patients at 3 hospitals14 sought to determine the association of preoperatively diagnosed PFO with the risk of perioperative ischemic stroke identified by International Classification of Diseases diagnoses.

Of 150,198 patients, 1.0% had a preoperative diagnosis of PFO, and at baseline, those with PFO had significantly more comorbidities than those without PFO. Stroke occurred in 3.2% of patients with PFO vs 0.5% of those without. Patients known to have a PFO were much more likely to have cardiovascular and thromboembolic risk factors for stroke. In the adjusted analysis, the absolute risk difference between groups was 0.4% (95% CI 0.2–0.6%), with an estimated perioperative stroke risk of 5.9 per 1,000 in patients with known patent foramen ovale and 2.2 per 1,000 in those without. A diagnosis of PFO was also associated with increased risk of large-vessel-territory stroke and more severe neurologic deficit.

Further attempts to adjust for baseline risk factors and other potential bias, including a propensity score-matched cohort analysis and an analysis limited to patients who had echocardiography performed in the same healthcare system, still showed a higher risk of perioperative stroke among patients with preoperatively detected patent foramen ovale.

Limitations. The study was retrospective and observational, used administrative data, and had a low rate of PFO diagnosis (1%), compared with about 25% in population-based studies.15 Indications for preoperative echocardiography are unknown. In addition, the study specifically examined preoperatively diagnosed PFO, rather than including those diagnosed in the postoperative period.

Discussion. How does this study affect clinical practice? The absolute stroke risk was increased by 0.4% in patients with PFO compared with those without. Although this is a relatively small increase, millions of patients undergo noncardiac surgery annually. The risks of therapeutic anticoagulation or PFO closure are likely too high in this context; however, clinicians may approach the perioperative management of antiplatelet agents and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients with known PFO with additional caution.

HOW DOES TIMING OF EMERGENCY SURGERY AFTER PRIOR STROKE AFFECT OUTCOMES?

A history of stroke or transient ischemic attack is a known risk factor for perioperative vascular complications. A recent large cohort study demonstrated that a history of stroke within 9 months of elective surgery was associated with increased adverse outcomes.16 Little is known, however, of the perioperative risk in patients with a history of stroke who undergo emergency surgery.

[Christiansen MN, Andersson C, Gislason GH, et al. Risks of cardiovascular adverse events and death in patients with previous stroke undergoing emergency noncardiac, nonintracranial surgery: the importance of operative timing. Anesthesiology 2017; 127(1):9–19.]

In this study,17 all emergency noncardiac and nonintracranial surgeries from 2005 to 2011 were analyzed using multiple national patient registries in Denmark according to time elapsed between previous stroke and surgery. Primary outcomes were 30-day all-cause mortality and 30-day major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as nonfatal ischemic stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death. Statistical analysis to assess the risk of adverse outcomes included logistic regression models, spline analyses, and propensity-score matching.

Findings. The authors identified 146,694 emergency surgeries, with 7,861 patients (5.4%) having had a previous stroke (transient ischemic attacks and hemorrhagic strokes were not included). Rates of postoperative stroke were as follows:

- 9.9% in patents with a history of ischemic stroke within 3 months of surgery

- 2.8% in patients with a history of stroke 3 to 9 months before surgery

- 0.3% in patients with no previous stroke.

The risk plateaued when the time between stroke and surgery exceeded 4 to 5 months.15

Interestingly, in patients who underwent emergency surgery within 14 days of stroke, the risk of MACE was significantly lower immediately after surgery (1–3 days after stroke) compared with surgery that took place 4 to 14 days after stroke. The authors hypothesized that because cerebral autoregulation does not become compromised until approximately 5 days after a stroke, the risk was lower 1 to 3 days after surgery and increased thereafter.

Limitations of this study included the possibility of residual confounding, given its retrospective design using administrative data, not accounting for preoperative antithrombotic and anticoagulation therapy, and lack of information regarding the etiology of recurrent stroke (eg, thromboembolic, atherothrombotic, hypoperfusion).

Conclusions. Although it would be impractical to postpone emergency surgery in a patient who recently had a stroke, this study shows that the incidence rates of postoperative recurrent stroke and MACE are high. Therefore, it is important that the patient and perioperative team be aware of the risk. Further research is needed to confirm these estimates of postoperative adverse events in more diverse patient populations.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(16):1494–1503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401105

- Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244. doi:10.7326/M17-2341

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 130(24):2215–2245. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000105

- Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Ramakrishna H, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with noncardiac surgery. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2(2):181–187. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4792

- Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology 2014; 120(3):564–578. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113

- Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, et al. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2017; 317(16):1642–1651. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.4360

- Puelacher C, Lurati Buse G, Seeberger D, et al. Perioperative myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: incidence, mortality, and characterization. Circulation 2018; 137(12):1221–1232. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030114

- Devereaux PJ, Duceppe E, Guyatt G, et al. Dabigatran in patients with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MANAGE): an international, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 391(10137):2325–2334. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30832-8

- Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology 2013; 119(3):507–515. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10e26

- Futier E, Lefrant JY, Guinot PG, et al. Effect of individualized vs standard blood pressure management strategies on postoperative organ dysfunction among high-risk patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318(14):1346–1357. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.14172