User login

Current Controversies in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been met with controversy since its inception in the 1930s. Current debate centers on the types of tumors treated with MMS, increasing utilization, third-party payer reimbursement, the Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC), and subspecialty certification.

Controversies in Applications

Controversy surrounding treatment with MMS for certain tumor types is abundant, in large part due to a lack of well-designed studies. Perhaps most notably, the surgical management of melanoma has been hotly contested for decades.1 An increasing number of Mohs surgeons advocate the use of MMS for treatment of melanoma. Advocates reason that tumor margins may be ill-defined, necessitating histologic examination of the margin for tumor clearance. In a study by Zitelli et al,2 5-year survival and metastatic rates for 535 patients with melanomas treated by MMS with frozen sections were the same or better when compared to historical controls treated with conventional wide local excision. Melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1) immunostaining may offer improved diagnostic accuracy.3 Others believe that staged excision with permanent sections processed vertically, en face, or horizontally (“slow Mohs”) is more accurate and efficacious for the treatment of melanoma.1 Advocates of this approach maintain that when compared to MMS with frozen sections, staged excision with permanent sections enables more accurate interpretation of residual melanoma and atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia as well as circumvents difficulty in interpreting freeze artifact.4

Although Merkel cell carcinoma has traditionally been treated with wide local excision, MMS with or without adjuvant radiotherapy has gained traction as a treatment option. Advocates for treatment by MMS hold that Merkel cell carcinoma is a contiguous tumor with a high rate of residual tumor persistence, making histologic margin control an ideal characteristic of treatment. However, in the absence of large randomized controlled studies comparing MMS to wide local excision, controversy surrounds the most appropriate surgical approach.1 In a retrospective study of 86 patients by O’Connor et al,5 MMS was demonstrated to compare favorably to standard surgical excision. Standard surgical excision was associated with a 31.7% (13/41) local persistence rate and 48.8% (20/41) regional metastasis rate compared to 8.3% (1/12) and 33.3% (4/12) for MMS, respectively.5

Controversies in Increasing Utilization

The incidence of skin cancers has increased in recent years. As a result, it is reasonable to expect the rates of MMS to increase. Nonetheless, there is escalating concern among groups of third-party payers, the public, and physicians that MMS is being overused.6 Growth of the body of evidence supporting the appropriateness of MMS remains essential. Such studies continue to support reasons for increased MMS usage, demonstrating the stability of the percentage of skin cancers treated with MMS in the setting of increasing skin cancer incidence, the procedure’s superior efficacy for appropriately chosen cases, its expanding application to melanoma and other tumors, and an emphasis of MMS in residency training programs.6-9

A current hot topic of controversy focuses on the wide variation among Mohs surgeons in the mean number of stages used to resect a tumor. Overuse among outliers has been proposed to stem from lack of technical expertise or from abuse of the current fee-for-service payment model, which bases compensation on the number of stages performed. A study by Krishnan et al10 determined that the mean number of stages per tumor in the studied population (all physicians [N=2305] receiving Medicare payments for MMS from January 2012 to December 2014) was 1.74, with a range of 1.09 to 4.11. Persistently high outliers were more likely to perform MMS in a solo practice, with an odds ratio of 2.35.10 In response to the wide variation in mean stages used to resect a skin cancer and its implications on increased financial burden and surgery to individual patients, intervention has been proposed. Notably, it has been demonstrated that mailing out individual reports of practice patterns to high-outlier physicians resulted in a reduction in mean stages per tumor as well as an associated cost savings when compared to outlier physicians who did not receive these reports.11

Controversies in Reimbursement

Mohs micrographic surgery also has been in the spotlight for debate regarding reimbursement. The procedure has been targeted partly in response to its substantial contribution to total Medicare reimbursements paid out. In 2013, primary MMS billing codes constituted nearly 19% of total reimbursements to dermatologists and approximately 0.5% of total reimbursements to all physicians participating in Medicare.12 Mohs micrographic surgery codes have correspondingly received frequent review by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee and remained on a list of potentially misvalued services according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for years.13 Due to continued scrutiny and review, especially by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, reimbursement to perform MMS and reconstructive surgery has gone down by more than 20% in the last 15 years.14 Public perception mirrors third-party payer concerns for overcompensation. An article title in the New York Times theatrically postures “Patients’ Costs Skyrocket, Specialists’ Incomes Soar.” The article recounts an MMS patient’s “outrage at charges” associated with treatment of her “minor medical problem” and the simultaneous “sharp climb” in dermatologist income over the last 2 decades.15

However, studies continue to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of MMS. A study by Ravitskiy et al16 demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of MMS, regardless of place of service or type of tumor. Of 406 tumors studied, MMS was the least expensive surgical procedure evaluated ($805 per tumor) when compared to standard surgical excision with permanent margins ($1026 per tumor), standard surgical excision with frozen margins ($1200 per tumor), and ambulatory surgery center standard surgical excision ($2507 per tumor). Furthermore, adjusted for inflation, the cost of MMS was lower in 2009 vs 1998.16 Similar results have been consistently demonstrated.17

Controversies in the AUC

To provide clinicians, policy makers, and insurers guidance for utilization of MMS in the setting of concerns for overutilization, overcompensation, and inappropriate application, the MMS AUC were established in 2012. The guidelines were developed by a process integrating evidence-based medicine, clinical experience, and expert opinion and is applicable to 270 clinical scenarios.18

A unique set of debate accompanies the guidelines. Namely, controversy has surrounded the classification of most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for treatment by MMS. These tumors have comparable cure rates when treated by MMS or curettage and cryosurgery, are often multifocal and require more Mohs stages than other basal cell carcinoma subtypes, and largely lack data on recurrence and invasion.19 The guidelines also have been scrutinized for including only studies from the United States.20 Furthermore, the report is largely based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

Some Mohs surgeons have concerns that the guidelines will minimize clinical judgment. Nonetheless, deviations from the AUC practiced by Mohs surgeons have been reported where clinical judgment supplants guideline criteria. The most commonly cited reasons for performing MMS on tumors classified as uncertain or inappropriate, according to one study by Ruiz et al,21 included performing multiple MMSs on the same day, tumor location on the lower legs, and incorporation into an adjacent wound. Reported discrepancies in the AUC further emphasize the importance of clinical judgment and call into question the need for future revision of the criteria.22 For example, a primary squamous cell carcinoma in situ greater than or equal to 2 cm located on the trunk and extremities (excluding pretibial surfaces, hands, feet, nail units, and ankles) in a healthy patient is categorized as appropriate, while a recurrent but otherwise identical squamous cell carcinoma in situ is categorized as uncertain. These counterintuitive criteria are unsupported by existing studies.

Controversies in Subspecialty Certification

Recently, debate also has surfaced regarding subspecialty certification. Over the last decade, proponents of subspecialty certification have argued that board certification would bring consistency and decrease divisiveness among dermatologists; help to prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks and teaching opportunities at the Veterans Administration; and demonstrate competence to patients, the media, and payers. Those in opposition contest that practices may be restricted by insurers using lack of certification to eliminate dermatologists from their networks, economic credentialing may be applied to dermatologists such that those without the subspecialty certification may not be deemed qualified to manage skin cancer, major limitations may be set determining which dermatologists can sit for the certification examination, and subspecialty certification could create disenfranchisement of many dermatologists. A 2017 American Academy of Dermatology member survey demonstrated ambivalence regarding subcertification, with 51% of respondents pro-subcertification and 48% anti-subcertification.23

Nonetheless, after years of debate the American Board of Dermatology proposed subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery, which was approved by the American Board of Medical Specialties on October 26, 2018. The first certification examination will likely take place in 2 years, and a maintenance of certification examination will be required every 10 years.24

Final Thoughts

Further investigation is needed to elucidate and optimize solutions to many of the current controversies associated with MMS.

- Levy RM, Hanke CW. Mohs micrographic surgery: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:269-274.

- Zitelli JA, Brown C, Hanusa BH. Surgical margins for excision of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:422-429.

- Albertini JG, Elston DM, Libow LF, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a case series, a comparative study of immunostains, an informative case report, and a unique mapping technique. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:656-665.

- Walling HW, Scupham RK, Bean AK, et al. Staged excision versus Mohs micrographic surgery for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:659-664.

- O’Connor WJ, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Merkel cell carcinoma. comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision in eighty-six patients. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:929-933.

- Reeder VJ, Gustafson CJ, Mireku K, et al. Trends in Mohs surgery from 1995 to 2010: an analysis of nationally representative data. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:397-403.

- Mosterd K, Krekels GA, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

- Viola KV, Rezzadeh KS, Gonsalves L, et al. National utilization patterns of Mohs micrographic surgery for invasive melanoma and melanoma in situ. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1060-1065.

- Todd MM, Miller JJ, Ammirati CT. Dermatologic surgery training in residency. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:547-549.

- Krishnan A, Xu T, Hutfless S, et al; American College of Mohs Surgery Improving Wisely Study Group. Outlier practice patterns in Mohs micrographic surgery: defining the problem and a proposed solution. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:565-570.

- Albertini JG, Wang P, Fahim C, et al. Evaluation of a peer-to-peer data transparency intervention for Mohs micrographic surgery overuse [published online May 5, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1259.

- Johnstone C, Joiner KA, Pierce J, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery volume and payment patterns among dermatologists in the Medicare population, 2013. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41:1199-1203.

- Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. Mohs micrographic surgery utilization in the Medicare population, 2009. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1427-1434.

- Bath C. Dermatologists defend Mohs surgery as effective and cost-efficient with low rate of recurrence. ASCO Post. March 15, 2014. https://www.ascopost.com/issues/march-15-2014/dermatologists-defend-mohs-surgery-as-effective-and-cost-efficient-with-low-rate-of-recurrence. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Rosenthal E. Patients’ costs skyrocket; specialists’ incomes soar. New York Times. January 18, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/19/health/patients-costs-skyrocket-specialists-incomes-soar.html. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Ravitskiy L, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Cost analysis: Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:585-594.

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:914-922.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs surgery appropriate use criteria for primary superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:755-756.

- Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:317-318.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria [published online December 23, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064.

- Weinstein A. The ABD’s push for subspecialty certification in Mohs surgery will fracture dermatology. Pract Dermatol. April 2018:37-39. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2018-apr/perspective-the-abds-push-for-subspecialty-certification-in-mohs-surgery-will-fracture-dermatology. Accessed Oc

tober 30, 2019. - ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) Subspecialty Certification Questions & Answers. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed October 23, 2019.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been met with controversy since its inception in the 1930s. Current debate centers on the types of tumors treated with MMS, increasing utilization, third-party payer reimbursement, the Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC), and subspecialty certification.

Controversies in Applications

Controversy surrounding treatment with MMS for certain tumor types is abundant, in large part due to a lack of well-designed studies. Perhaps most notably, the surgical management of melanoma has been hotly contested for decades.1 An increasing number of Mohs surgeons advocate the use of MMS for treatment of melanoma. Advocates reason that tumor margins may be ill-defined, necessitating histologic examination of the margin for tumor clearance. In a study by Zitelli et al,2 5-year survival and metastatic rates for 535 patients with melanomas treated by MMS with frozen sections were the same or better when compared to historical controls treated with conventional wide local excision. Melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1) immunostaining may offer improved diagnostic accuracy.3 Others believe that staged excision with permanent sections processed vertically, en face, or horizontally (“slow Mohs”) is more accurate and efficacious for the treatment of melanoma.1 Advocates of this approach maintain that when compared to MMS with frozen sections, staged excision with permanent sections enables more accurate interpretation of residual melanoma and atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia as well as circumvents difficulty in interpreting freeze artifact.4

Although Merkel cell carcinoma has traditionally been treated with wide local excision, MMS with or without adjuvant radiotherapy has gained traction as a treatment option. Advocates for treatment by MMS hold that Merkel cell carcinoma is a contiguous tumor with a high rate of residual tumor persistence, making histologic margin control an ideal characteristic of treatment. However, in the absence of large randomized controlled studies comparing MMS to wide local excision, controversy surrounds the most appropriate surgical approach.1 In a retrospective study of 86 patients by O’Connor et al,5 MMS was demonstrated to compare favorably to standard surgical excision. Standard surgical excision was associated with a 31.7% (13/41) local persistence rate and 48.8% (20/41) regional metastasis rate compared to 8.3% (1/12) and 33.3% (4/12) for MMS, respectively.5

Controversies in Increasing Utilization

The incidence of skin cancers has increased in recent years. As a result, it is reasonable to expect the rates of MMS to increase. Nonetheless, there is escalating concern among groups of third-party payers, the public, and physicians that MMS is being overused.6 Growth of the body of evidence supporting the appropriateness of MMS remains essential. Such studies continue to support reasons for increased MMS usage, demonstrating the stability of the percentage of skin cancers treated with MMS in the setting of increasing skin cancer incidence, the procedure’s superior efficacy for appropriately chosen cases, its expanding application to melanoma and other tumors, and an emphasis of MMS in residency training programs.6-9

A current hot topic of controversy focuses on the wide variation among Mohs surgeons in the mean number of stages used to resect a tumor. Overuse among outliers has been proposed to stem from lack of technical expertise or from abuse of the current fee-for-service payment model, which bases compensation on the number of stages performed. A study by Krishnan et al10 determined that the mean number of stages per tumor in the studied population (all physicians [N=2305] receiving Medicare payments for MMS from January 2012 to December 2014) was 1.74, with a range of 1.09 to 4.11. Persistently high outliers were more likely to perform MMS in a solo practice, with an odds ratio of 2.35.10 In response to the wide variation in mean stages used to resect a skin cancer and its implications on increased financial burden and surgery to individual patients, intervention has been proposed. Notably, it has been demonstrated that mailing out individual reports of practice patterns to high-outlier physicians resulted in a reduction in mean stages per tumor as well as an associated cost savings when compared to outlier physicians who did not receive these reports.11

Controversies in Reimbursement

Mohs micrographic surgery also has been in the spotlight for debate regarding reimbursement. The procedure has been targeted partly in response to its substantial contribution to total Medicare reimbursements paid out. In 2013, primary MMS billing codes constituted nearly 19% of total reimbursements to dermatologists and approximately 0.5% of total reimbursements to all physicians participating in Medicare.12 Mohs micrographic surgery codes have correspondingly received frequent review by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee and remained on a list of potentially misvalued services according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for years.13 Due to continued scrutiny and review, especially by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, reimbursement to perform MMS and reconstructive surgery has gone down by more than 20% in the last 15 years.14 Public perception mirrors third-party payer concerns for overcompensation. An article title in the New York Times theatrically postures “Patients’ Costs Skyrocket, Specialists’ Incomes Soar.” The article recounts an MMS patient’s “outrage at charges” associated with treatment of her “minor medical problem” and the simultaneous “sharp climb” in dermatologist income over the last 2 decades.15

However, studies continue to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of MMS. A study by Ravitskiy et al16 demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of MMS, regardless of place of service or type of tumor. Of 406 tumors studied, MMS was the least expensive surgical procedure evaluated ($805 per tumor) when compared to standard surgical excision with permanent margins ($1026 per tumor), standard surgical excision with frozen margins ($1200 per tumor), and ambulatory surgery center standard surgical excision ($2507 per tumor). Furthermore, adjusted for inflation, the cost of MMS was lower in 2009 vs 1998.16 Similar results have been consistently demonstrated.17

Controversies in the AUC

To provide clinicians, policy makers, and insurers guidance for utilization of MMS in the setting of concerns for overutilization, overcompensation, and inappropriate application, the MMS AUC were established in 2012. The guidelines were developed by a process integrating evidence-based medicine, clinical experience, and expert opinion and is applicable to 270 clinical scenarios.18

A unique set of debate accompanies the guidelines. Namely, controversy has surrounded the classification of most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for treatment by MMS. These tumors have comparable cure rates when treated by MMS or curettage and cryosurgery, are often multifocal and require more Mohs stages than other basal cell carcinoma subtypes, and largely lack data on recurrence and invasion.19 The guidelines also have been scrutinized for including only studies from the United States.20 Furthermore, the report is largely based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

Some Mohs surgeons have concerns that the guidelines will minimize clinical judgment. Nonetheless, deviations from the AUC practiced by Mohs surgeons have been reported where clinical judgment supplants guideline criteria. The most commonly cited reasons for performing MMS on tumors classified as uncertain or inappropriate, according to one study by Ruiz et al,21 included performing multiple MMSs on the same day, tumor location on the lower legs, and incorporation into an adjacent wound. Reported discrepancies in the AUC further emphasize the importance of clinical judgment and call into question the need for future revision of the criteria.22 For example, a primary squamous cell carcinoma in situ greater than or equal to 2 cm located on the trunk and extremities (excluding pretibial surfaces, hands, feet, nail units, and ankles) in a healthy patient is categorized as appropriate, while a recurrent but otherwise identical squamous cell carcinoma in situ is categorized as uncertain. These counterintuitive criteria are unsupported by existing studies.

Controversies in Subspecialty Certification

Recently, debate also has surfaced regarding subspecialty certification. Over the last decade, proponents of subspecialty certification have argued that board certification would bring consistency and decrease divisiveness among dermatologists; help to prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks and teaching opportunities at the Veterans Administration; and demonstrate competence to patients, the media, and payers. Those in opposition contest that practices may be restricted by insurers using lack of certification to eliminate dermatologists from their networks, economic credentialing may be applied to dermatologists such that those without the subspecialty certification may not be deemed qualified to manage skin cancer, major limitations may be set determining which dermatologists can sit for the certification examination, and subspecialty certification could create disenfranchisement of many dermatologists. A 2017 American Academy of Dermatology member survey demonstrated ambivalence regarding subcertification, with 51% of respondents pro-subcertification and 48% anti-subcertification.23

Nonetheless, after years of debate the American Board of Dermatology proposed subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery, which was approved by the American Board of Medical Specialties on October 26, 2018. The first certification examination will likely take place in 2 years, and a maintenance of certification examination will be required every 10 years.24

Final Thoughts

Further investigation is needed to elucidate and optimize solutions to many of the current controversies associated with MMS.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been met with controversy since its inception in the 1930s. Current debate centers on the types of tumors treated with MMS, increasing utilization, third-party payer reimbursement, the Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC), and subspecialty certification.

Controversies in Applications

Controversy surrounding treatment with MMS for certain tumor types is abundant, in large part due to a lack of well-designed studies. Perhaps most notably, the surgical management of melanoma has been hotly contested for decades.1 An increasing number of Mohs surgeons advocate the use of MMS for treatment of melanoma. Advocates reason that tumor margins may be ill-defined, necessitating histologic examination of the margin for tumor clearance. In a study by Zitelli et al,2 5-year survival and metastatic rates for 535 patients with melanomas treated by MMS with frozen sections were the same or better when compared to historical controls treated with conventional wide local excision. Melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1) immunostaining may offer improved diagnostic accuracy.3 Others believe that staged excision with permanent sections processed vertically, en face, or horizontally (“slow Mohs”) is more accurate and efficacious for the treatment of melanoma.1 Advocates of this approach maintain that when compared to MMS with frozen sections, staged excision with permanent sections enables more accurate interpretation of residual melanoma and atypical junctional melanocytic hyperplasia as well as circumvents difficulty in interpreting freeze artifact.4

Although Merkel cell carcinoma has traditionally been treated with wide local excision, MMS with or without adjuvant radiotherapy has gained traction as a treatment option. Advocates for treatment by MMS hold that Merkel cell carcinoma is a contiguous tumor with a high rate of residual tumor persistence, making histologic margin control an ideal characteristic of treatment. However, in the absence of large randomized controlled studies comparing MMS to wide local excision, controversy surrounds the most appropriate surgical approach.1 In a retrospective study of 86 patients by O’Connor et al,5 MMS was demonstrated to compare favorably to standard surgical excision. Standard surgical excision was associated with a 31.7% (13/41) local persistence rate and 48.8% (20/41) regional metastasis rate compared to 8.3% (1/12) and 33.3% (4/12) for MMS, respectively.5

Controversies in Increasing Utilization

The incidence of skin cancers has increased in recent years. As a result, it is reasonable to expect the rates of MMS to increase. Nonetheless, there is escalating concern among groups of third-party payers, the public, and physicians that MMS is being overused.6 Growth of the body of evidence supporting the appropriateness of MMS remains essential. Such studies continue to support reasons for increased MMS usage, demonstrating the stability of the percentage of skin cancers treated with MMS in the setting of increasing skin cancer incidence, the procedure’s superior efficacy for appropriately chosen cases, its expanding application to melanoma and other tumors, and an emphasis of MMS in residency training programs.6-9

A current hot topic of controversy focuses on the wide variation among Mohs surgeons in the mean number of stages used to resect a tumor. Overuse among outliers has been proposed to stem from lack of technical expertise or from abuse of the current fee-for-service payment model, which bases compensation on the number of stages performed. A study by Krishnan et al10 determined that the mean number of stages per tumor in the studied population (all physicians [N=2305] receiving Medicare payments for MMS from January 2012 to December 2014) was 1.74, with a range of 1.09 to 4.11. Persistently high outliers were more likely to perform MMS in a solo practice, with an odds ratio of 2.35.10 In response to the wide variation in mean stages used to resect a skin cancer and its implications on increased financial burden and surgery to individual patients, intervention has been proposed. Notably, it has been demonstrated that mailing out individual reports of practice patterns to high-outlier physicians resulted in a reduction in mean stages per tumor as well as an associated cost savings when compared to outlier physicians who did not receive these reports.11

Controversies in Reimbursement

Mohs micrographic surgery also has been in the spotlight for debate regarding reimbursement. The procedure has been targeted partly in response to its substantial contribution to total Medicare reimbursements paid out. In 2013, primary MMS billing codes constituted nearly 19% of total reimbursements to dermatologists and approximately 0.5% of total reimbursements to all physicians participating in Medicare.12 Mohs micrographic surgery codes have correspondingly received frequent review by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee and remained on a list of potentially misvalued services according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for years.13 Due to continued scrutiny and review, especially by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, reimbursement to perform MMS and reconstructive surgery has gone down by more than 20% in the last 15 years.14 Public perception mirrors third-party payer concerns for overcompensation. An article title in the New York Times theatrically postures “Patients’ Costs Skyrocket, Specialists’ Incomes Soar.” The article recounts an MMS patient’s “outrage at charges” associated with treatment of her “minor medical problem” and the simultaneous “sharp climb” in dermatologist income over the last 2 decades.15

However, studies continue to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of MMS. A study by Ravitskiy et al16 demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of MMS, regardless of place of service or type of tumor. Of 406 tumors studied, MMS was the least expensive surgical procedure evaluated ($805 per tumor) when compared to standard surgical excision with permanent margins ($1026 per tumor), standard surgical excision with frozen margins ($1200 per tumor), and ambulatory surgery center standard surgical excision ($2507 per tumor). Furthermore, adjusted for inflation, the cost of MMS was lower in 2009 vs 1998.16 Similar results have been consistently demonstrated.17

Controversies in the AUC

To provide clinicians, policy makers, and insurers guidance for utilization of MMS in the setting of concerns for overutilization, overcompensation, and inappropriate application, the MMS AUC were established in 2012. The guidelines were developed by a process integrating evidence-based medicine, clinical experience, and expert opinion and is applicable to 270 clinical scenarios.18

A unique set of debate accompanies the guidelines. Namely, controversy has surrounded the classification of most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for treatment by MMS. These tumors have comparable cure rates when treated by MMS or curettage and cryosurgery, are often multifocal and require more Mohs stages than other basal cell carcinoma subtypes, and largely lack data on recurrence and invasion.19 The guidelines also have been scrutinized for including only studies from the United States.20 Furthermore, the report is largely based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

Some Mohs surgeons have concerns that the guidelines will minimize clinical judgment. Nonetheless, deviations from the AUC practiced by Mohs surgeons have been reported where clinical judgment supplants guideline criteria. The most commonly cited reasons for performing MMS on tumors classified as uncertain or inappropriate, according to one study by Ruiz et al,21 included performing multiple MMSs on the same day, tumor location on the lower legs, and incorporation into an adjacent wound. Reported discrepancies in the AUC further emphasize the importance of clinical judgment and call into question the need for future revision of the criteria.22 For example, a primary squamous cell carcinoma in situ greater than or equal to 2 cm located on the trunk and extremities (excluding pretibial surfaces, hands, feet, nail units, and ankles) in a healthy patient is categorized as appropriate, while a recurrent but otherwise identical squamous cell carcinoma in situ is categorized as uncertain. These counterintuitive criteria are unsupported by existing studies.

Controversies in Subspecialty Certification

Recently, debate also has surfaced regarding subspecialty certification. Over the last decade, proponents of subspecialty certification have argued that board certification would bring consistency and decrease divisiveness among dermatologists; help to prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks and teaching opportunities at the Veterans Administration; and demonstrate competence to patients, the media, and payers. Those in opposition contest that practices may be restricted by insurers using lack of certification to eliminate dermatologists from their networks, economic credentialing may be applied to dermatologists such that those without the subspecialty certification may not be deemed qualified to manage skin cancer, major limitations may be set determining which dermatologists can sit for the certification examination, and subspecialty certification could create disenfranchisement of many dermatologists. A 2017 American Academy of Dermatology member survey demonstrated ambivalence regarding subcertification, with 51% of respondents pro-subcertification and 48% anti-subcertification.23

Nonetheless, after years of debate the American Board of Dermatology proposed subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery, which was approved by the American Board of Medical Specialties on October 26, 2018. The first certification examination will likely take place in 2 years, and a maintenance of certification examination will be required every 10 years.24

Final Thoughts

Further investigation is needed to elucidate and optimize solutions to many of the current controversies associated with MMS.

- Levy RM, Hanke CW. Mohs micrographic surgery: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:269-274.

- Zitelli JA, Brown C, Hanusa BH. Surgical margins for excision of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:422-429.

- Albertini JG, Elston DM, Libow LF, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a case series, a comparative study of immunostains, an informative case report, and a unique mapping technique. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:656-665.

- Walling HW, Scupham RK, Bean AK, et al. Staged excision versus Mohs micrographic surgery for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:659-664.

- O’Connor WJ, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Merkel cell carcinoma. comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision in eighty-six patients. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:929-933.

- Reeder VJ, Gustafson CJ, Mireku K, et al. Trends in Mohs surgery from 1995 to 2010: an analysis of nationally representative data. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:397-403.

- Mosterd K, Krekels GA, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

- Viola KV, Rezzadeh KS, Gonsalves L, et al. National utilization patterns of Mohs micrographic surgery for invasive melanoma and melanoma in situ. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1060-1065.

- Todd MM, Miller JJ, Ammirati CT. Dermatologic surgery training in residency. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:547-549.

- Krishnan A, Xu T, Hutfless S, et al; American College of Mohs Surgery Improving Wisely Study Group. Outlier practice patterns in Mohs micrographic surgery: defining the problem and a proposed solution. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:565-570.

- Albertini JG, Wang P, Fahim C, et al. Evaluation of a peer-to-peer data transparency intervention for Mohs micrographic surgery overuse [published online May 5, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1259.

- Johnstone C, Joiner KA, Pierce J, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery volume and payment patterns among dermatologists in the Medicare population, 2013. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41:1199-1203.

- Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. Mohs micrographic surgery utilization in the Medicare population, 2009. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1427-1434.

- Bath C. Dermatologists defend Mohs surgery as effective and cost-efficient with low rate of recurrence. ASCO Post. March 15, 2014. https://www.ascopost.com/issues/march-15-2014/dermatologists-defend-mohs-surgery-as-effective-and-cost-efficient-with-low-rate-of-recurrence. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Rosenthal E. Patients’ costs skyrocket; specialists’ incomes soar. New York Times. January 18, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/19/health/patients-costs-skyrocket-specialists-incomes-soar.html. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Ravitskiy L, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Cost analysis: Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:585-594.

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:914-922.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs surgery appropriate use criteria for primary superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:755-756.

- Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:317-318.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria [published online December 23, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064.

- Weinstein A. The ABD’s push for subspecialty certification in Mohs surgery will fracture dermatology. Pract Dermatol. April 2018:37-39. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2018-apr/perspective-the-abds-push-for-subspecialty-certification-in-mohs-surgery-will-fracture-dermatology. Accessed Oc

tober 30, 2019. - ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) Subspecialty Certification Questions & Answers. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Levy RM, Hanke CW. Mohs micrographic surgery: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:269-274.

- Zitelli JA, Brown C, Hanusa BH. Surgical margins for excision of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:422-429.

- Albertini JG, Elston DM, Libow LF, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a case series, a comparative study of immunostains, an informative case report, and a unique mapping technique. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:656-665.

- Walling HW, Scupham RK, Bean AK, et al. Staged excision versus Mohs micrographic surgery for lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:659-664.

- O’Connor WJ, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Merkel cell carcinoma. comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision in eighty-six patients. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:929-933.

- Reeder VJ, Gustafson CJ, Mireku K, et al. Trends in Mohs surgery from 1995 to 2010: an analysis of nationally representative data. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:397-403.

- Mosterd K, Krekels GA, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

- Viola KV, Rezzadeh KS, Gonsalves L, et al. National utilization patterns of Mohs micrographic surgery for invasive melanoma and melanoma in situ. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1060-1065.

- Todd MM, Miller JJ, Ammirati CT. Dermatologic surgery training in residency. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:547-549.

- Krishnan A, Xu T, Hutfless S, et al; American College of Mohs Surgery Improving Wisely Study Group. Outlier practice patterns in Mohs micrographic surgery: defining the problem and a proposed solution. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:565-570.

- Albertini JG, Wang P, Fahim C, et al. Evaluation of a peer-to-peer data transparency intervention for Mohs micrographic surgery overuse [published online May 5, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1259.

- Johnstone C, Joiner KA, Pierce J, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery volume and payment patterns among dermatologists in the Medicare population, 2013. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41:1199-1203.

- Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. Mohs micrographic surgery utilization in the Medicare population, 2009. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1427-1434.

- Bath C. Dermatologists defend Mohs surgery as effective and cost-efficient with low rate of recurrence. ASCO Post. March 15, 2014. https://www.ascopost.com/issues/march-15-2014/dermatologists-defend-mohs-surgery-as-effective-and-cost-efficient-with-low-rate-of-recurrence. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Rosenthal E. Patients’ costs skyrocket; specialists’ incomes soar. New York Times. January 18, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/19/health/patients-costs-skyrocket-specialists-incomes-soar.html. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Ravitskiy L, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Cost analysis: Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:585-594.

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:914-922.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs surgery appropriate use criteria for primary superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:755-756.

- Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:317-318.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria [published online December 23, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064.

- Weinstein A. The ABD’s push for subspecialty certification in Mohs surgery will fracture dermatology. Pract Dermatol. April 2018:37-39. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2018-apr/perspective-the-abds-push-for-subspecialty-certification-in-mohs-surgery-will-fracture-dermatology. Accessed Oc

tober 30, 2019. - ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) Subspecialty Certification Questions & Answers. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed October 23, 2019.

Resident Pearl:

• Further investigation is needed to elucidate and optimize solutions to current controversies in Mohs micrographic surgery.

#Dermlife and the Burned-out Resident

Dermatologist Dr. Jeffrey Benabio quipped, “The phrase ‘dermatologist burnout’ may seem as oxymoronic as jumbo shrimp, yet both are real.”1 Indeed, dermatologists often self-report as among the happiest specialists both at work and home, according to the annual Medscape Physician Lifestyle and Happiness Report.2 Similarly, others in the medical field may perceive dermatologists as low-stress providers—well-groomed, well-rested rays of sunshine, getting out of work every day at 5:00

Burnout in Dermatology Residents

Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment that affects residents of all specialties3; however, there is a paucity of literature on burnout as it relates to dermatology. Although long work hours and schedule volatility have captured the focus of resident burnout conversations, a less discussed set of factors may contribute to dermatology resident burnout, such as increasing patient load, intensifying regulations, and an unrelenting pace of clinic. A recent survey study by Shoimer et al3 found that 61% of 116 participating Canadian dermatology residents cited examinations (including the board certifying examination) as their top stressor, followed by work (27%). Other stressors included family, relationships, finances, pressure from staff, research, and moving. More than 50% of dermatology residents surveyed experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while 40% demonstrated a low sense of personal accomplishment, all of which are determinants of the burnout syndrome.3

Comparison to Residents in Other Specialties

Although dermatology residents experience lower burnout rates than colleagues in other specialties, the absolute prevalence warrants attention. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association of 3588 second-year medical residents in the United States found that rates of burnout symptoms across clinical specialties ranged from 29.6% to 63.8%. The highest rates of burnout were found in urology (63.8%), neurology (61.6%), and ophthalmology (55.8%), but the lowest reported rate of burnout was demonstrated in dermatology (29.6%).4 Although dermatology ranked the lowest, that is still nearly a whopping 1 in 3 dermatology residents with burnout symptoms. The absolute prevalence should not be obscured by the ranking among other specialties.

Preventing Burnout

Several burnout prevention and coping strategies across specialties have been suggested.

Mindfulness and Self-awareness

A study by Chaukos et al5 found that mindfulness and self-awareness are resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Counseling is one strategy demonstrated to increase self-awareness. Mindfulness may be practiced through meditation or yoga. Regular meditation has been shown to improve mood and emotional stress.6 Similarly, yoga has been shown to yield physical, emotional, and psychological benefits to resdients.7

Work Factors

A supportive clinical faculty and receiving constructive monthly performance feedback have been negatively correlated with dermatology resident burnout.3 Other workplace interventions demonstrating utility in decreasing resident burnout include increasing staff awareness about burnout, increasing support for health professionals treating challenging populations, and ensuring a reasonable workload.6

Sleep

It has been demonstrated that sleeping less than 7 hours per night also is associated with resident burnout,7 yet it has been reported that 72% of dermatology residents fall into this category.3 Poor sleep quality has been shown to be a predictor of lower academic performance. It has been proposed that to minimize sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality, institutions should focus on programs that promote regular exercise, sleep hygiene, mindfulness, and time-out activities such as meditation.7

Social Support

Focusing on peers may foster the inner strength to endure suffering.1 Venting, laughing, and discussing care with colleagues has been demonstrated to decrease anxiety.6 Work-related social networks may be strengthened through attendance at conferences, lectures, and professional organizations.7 Additionally, social supports and spending quality time with family have been demonstrated as negative predictors of dermatology resident burnout.3

Physical Exercise

Exercise has been demonstrated to improve mood, anxiety, and depression, thereby decreasing resident burnout.6

Final Thoughts

Burnout among dermatology residents warrants awareness, as it does in other medical specialties. Awareness may facilitate identification and prevention, the latter of which is perhaps best summarized by the words of psychologist Dr. Christina Maslach: “If all of the knowledge and advice about how to beat burnout could be summed up in 1 word, that word would be balance—balance between giving and getting, balance between stress and calm, balance between work and home.”8

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Martin KL. Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-happiness-6011057. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Shoimer I, Patten S, Mydlarski P. Burnout in dermatology residents: a Canadian perspective. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:270-271.

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among us resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114-1130.

- Chaukos D, Chaed-Friedman E, Mehta D, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:189-194.

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;2:236-242.

- Tolentino J, Guo W, Ricca R, et al. What’s new in academic medicine: can we effectively address the burnout epidemic in healthcare? Int J Acad Med. 2017;3.

- Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis; 1993:19-32.

Dermatologist Dr. Jeffrey Benabio quipped, “The phrase ‘dermatologist burnout’ may seem as oxymoronic as jumbo shrimp, yet both are real.”1 Indeed, dermatologists often self-report as among the happiest specialists both at work and home, according to the annual Medscape Physician Lifestyle and Happiness Report.2 Similarly, others in the medical field may perceive dermatologists as low-stress providers—well-groomed, well-rested rays of sunshine, getting out of work every day at 5:00

Burnout in Dermatology Residents

Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment that affects residents of all specialties3; however, there is a paucity of literature on burnout as it relates to dermatology. Although long work hours and schedule volatility have captured the focus of resident burnout conversations, a less discussed set of factors may contribute to dermatology resident burnout, such as increasing patient load, intensifying regulations, and an unrelenting pace of clinic. A recent survey study by Shoimer et al3 found that 61% of 116 participating Canadian dermatology residents cited examinations (including the board certifying examination) as their top stressor, followed by work (27%). Other stressors included family, relationships, finances, pressure from staff, research, and moving. More than 50% of dermatology residents surveyed experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while 40% demonstrated a low sense of personal accomplishment, all of which are determinants of the burnout syndrome.3

Comparison to Residents in Other Specialties

Although dermatology residents experience lower burnout rates than colleagues in other specialties, the absolute prevalence warrants attention. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association of 3588 second-year medical residents in the United States found that rates of burnout symptoms across clinical specialties ranged from 29.6% to 63.8%. The highest rates of burnout were found in urology (63.8%), neurology (61.6%), and ophthalmology (55.8%), but the lowest reported rate of burnout was demonstrated in dermatology (29.6%).4 Although dermatology ranked the lowest, that is still nearly a whopping 1 in 3 dermatology residents with burnout symptoms. The absolute prevalence should not be obscured by the ranking among other specialties.

Preventing Burnout

Several burnout prevention and coping strategies across specialties have been suggested.

Mindfulness and Self-awareness

A study by Chaukos et al5 found that mindfulness and self-awareness are resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Counseling is one strategy demonstrated to increase self-awareness. Mindfulness may be practiced through meditation or yoga. Regular meditation has been shown to improve mood and emotional stress.6 Similarly, yoga has been shown to yield physical, emotional, and psychological benefits to resdients.7

Work Factors

A supportive clinical faculty and receiving constructive monthly performance feedback have been negatively correlated with dermatology resident burnout.3 Other workplace interventions demonstrating utility in decreasing resident burnout include increasing staff awareness about burnout, increasing support for health professionals treating challenging populations, and ensuring a reasonable workload.6

Sleep

It has been demonstrated that sleeping less than 7 hours per night also is associated with resident burnout,7 yet it has been reported that 72% of dermatology residents fall into this category.3 Poor sleep quality has been shown to be a predictor of lower academic performance. It has been proposed that to minimize sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality, institutions should focus on programs that promote regular exercise, sleep hygiene, mindfulness, and time-out activities such as meditation.7

Social Support

Focusing on peers may foster the inner strength to endure suffering.1 Venting, laughing, and discussing care with colleagues has been demonstrated to decrease anxiety.6 Work-related social networks may be strengthened through attendance at conferences, lectures, and professional organizations.7 Additionally, social supports and spending quality time with family have been demonstrated as negative predictors of dermatology resident burnout.3

Physical Exercise

Exercise has been demonstrated to improve mood, anxiety, and depression, thereby decreasing resident burnout.6

Final Thoughts

Burnout among dermatology residents warrants awareness, as it does in other medical specialties. Awareness may facilitate identification and prevention, the latter of which is perhaps best summarized by the words of psychologist Dr. Christina Maslach: “If all of the knowledge and advice about how to beat burnout could be summed up in 1 word, that word would be balance—balance between giving and getting, balance between stress and calm, balance between work and home.”8

Dermatologist Dr. Jeffrey Benabio quipped, “The phrase ‘dermatologist burnout’ may seem as oxymoronic as jumbo shrimp, yet both are real.”1 Indeed, dermatologists often self-report as among the happiest specialists both at work and home, according to the annual Medscape Physician Lifestyle and Happiness Report.2 Similarly, others in the medical field may perceive dermatologists as low-stress providers—well-groomed, well-rested rays of sunshine, getting out of work every day at 5:00

Burnout in Dermatology Residents

Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment that affects residents of all specialties3; however, there is a paucity of literature on burnout as it relates to dermatology. Although long work hours and schedule volatility have captured the focus of resident burnout conversations, a less discussed set of factors may contribute to dermatology resident burnout, such as increasing patient load, intensifying regulations, and an unrelenting pace of clinic. A recent survey study by Shoimer et al3 found that 61% of 116 participating Canadian dermatology residents cited examinations (including the board certifying examination) as their top stressor, followed by work (27%). Other stressors included family, relationships, finances, pressure from staff, research, and moving. More than 50% of dermatology residents surveyed experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while 40% demonstrated a low sense of personal accomplishment, all of which are determinants of the burnout syndrome.3

Comparison to Residents in Other Specialties

Although dermatology residents experience lower burnout rates than colleagues in other specialties, the absolute prevalence warrants attention. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association of 3588 second-year medical residents in the United States found that rates of burnout symptoms across clinical specialties ranged from 29.6% to 63.8%. The highest rates of burnout were found in urology (63.8%), neurology (61.6%), and ophthalmology (55.8%), but the lowest reported rate of burnout was demonstrated in dermatology (29.6%).4 Although dermatology ranked the lowest, that is still nearly a whopping 1 in 3 dermatology residents with burnout symptoms. The absolute prevalence should not be obscured by the ranking among other specialties.

Preventing Burnout

Several burnout prevention and coping strategies across specialties have been suggested.

Mindfulness and Self-awareness

A study by Chaukos et al5 found that mindfulness and self-awareness are resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Counseling is one strategy demonstrated to increase self-awareness. Mindfulness may be practiced through meditation or yoga. Regular meditation has been shown to improve mood and emotional stress.6 Similarly, yoga has been shown to yield physical, emotional, and psychological benefits to resdients.7

Work Factors

A supportive clinical faculty and receiving constructive monthly performance feedback have been negatively correlated with dermatology resident burnout.3 Other workplace interventions demonstrating utility in decreasing resident burnout include increasing staff awareness about burnout, increasing support for health professionals treating challenging populations, and ensuring a reasonable workload.6

Sleep

It has been demonstrated that sleeping less than 7 hours per night also is associated with resident burnout,7 yet it has been reported that 72% of dermatology residents fall into this category.3 Poor sleep quality has been shown to be a predictor of lower academic performance. It has been proposed that to minimize sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality, institutions should focus on programs that promote regular exercise, sleep hygiene, mindfulness, and time-out activities such as meditation.7

Social Support

Focusing on peers may foster the inner strength to endure suffering.1 Venting, laughing, and discussing care with colleagues has been demonstrated to decrease anxiety.6 Work-related social networks may be strengthened through attendance at conferences, lectures, and professional organizations.7 Additionally, social supports and spending quality time with family have been demonstrated as negative predictors of dermatology resident burnout.3

Physical Exercise

Exercise has been demonstrated to improve mood, anxiety, and depression, thereby decreasing resident burnout.6

Final Thoughts

Burnout among dermatology residents warrants awareness, as it does in other medical specialties. Awareness may facilitate identification and prevention, the latter of which is perhaps best summarized by the words of psychologist Dr. Christina Maslach: “If all of the knowledge and advice about how to beat burnout could be summed up in 1 word, that word would be balance—balance between giving and getting, balance between stress and calm, balance between work and home.”8

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Martin KL. Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-happiness-6011057. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Shoimer I, Patten S, Mydlarski P. Burnout in dermatology residents: a Canadian perspective. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:270-271.

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among us resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114-1130.

- Chaukos D, Chaed-Friedman E, Mehta D, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:189-194.

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;2:236-242.

- Tolentino J, Guo W, Ricca R, et al. What’s new in academic medicine: can we effectively address the burnout epidemic in healthcare? Int J Acad Med. 2017;3.

- Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis; 1993:19-32.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Martin KL. Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-happiness-6011057. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Shoimer I, Patten S, Mydlarski P. Burnout in dermatology residents: a Canadian perspective. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:270-271.

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among us resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114-1130.

- Chaukos D, Chaed-Friedman E, Mehta D, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:189-194.

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;2:236-242.

- Tolentino J, Guo W, Ricca R, et al. What’s new in academic medicine: can we effectively address the burnout epidemic in healthcare? Int J Acad Med. 2017;3.

- Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis; 1993:19-32.

Resident Pearl

- Reported techniques for preventing and coping with resident burnout include mindfulness and self-awareness, optimization of workplace factors, adequate sleep, social support, and physical exercise.

Clinical Pearl: Advantages of the Scalp as a Split-Thickness Skin Graft Donor Site

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

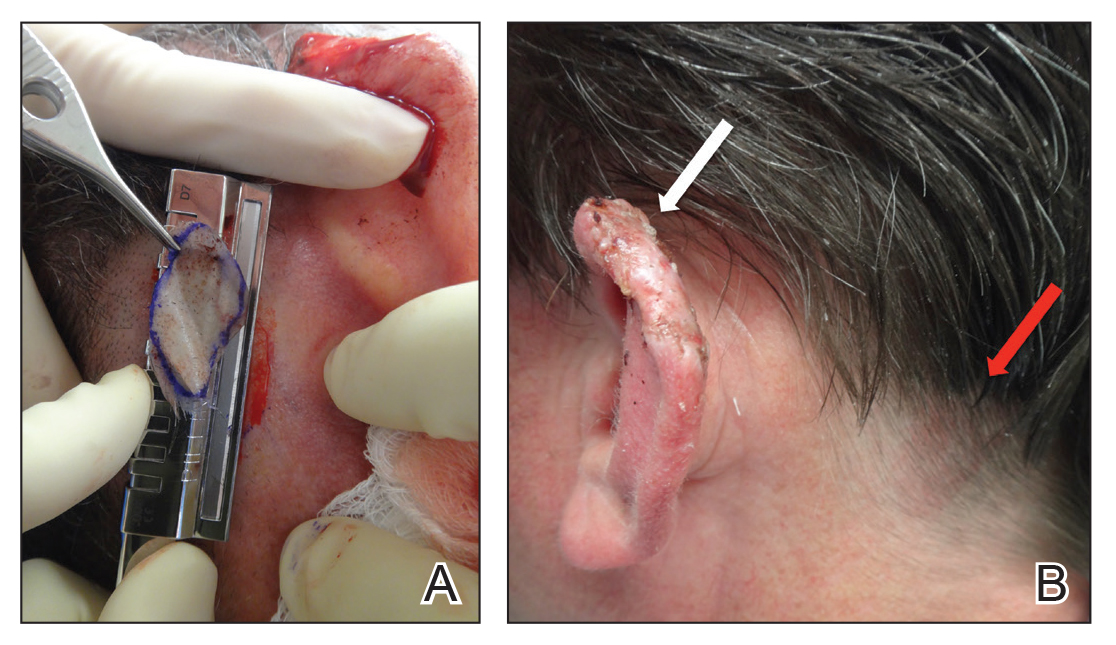

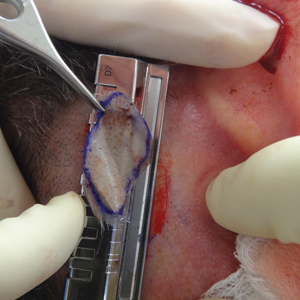

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

The Evolution of the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1