User login

An erythematous facial rash

A 59-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a large asymptomatic facial rash that had developed several months earlier. The rash had been slowly growing but did not change day to day. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cutaneous lymphoma, which was localized to her arms. She denied the use of any new products, including hair or facial products, nail polish, or any new medications.

Initially, she was presumed (by an outside provider) to have rosacea, and she received treatment with doxycycline 100 mg/d for 2 months. However, the rash did not improve.

Physical examination revealed a large erythematous rash involving her cheeks, nose, and periocular area with no other significant findings (FIGURE).

A biopsy of her right cheek was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mycosis fungoides

Following the biopsy of her right cheek, a histopathologic analysis demonstrated an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate positive for CD3 and CD4. These histopathologic features led to a diagnosis of recurrent mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous lymphoma. (Our patient’s cutaneous lymphoma had been in remission for a year following local radiotherapy.)

MF is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, with an incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million people in the United States.1 There are also 2 rare subtypes of MF: the psoriasiform and palmoplantar forms. Psoriasiform MF presents with psoriasis-like plaques, while palmoplantar MF initially presents on the palms and soles.

Patients with classic MF typically present with patches and plaques—with the late evolution of tumors—on non–sun-exposed areas.1 Our patient’s clinical presentation was atypical because the rash manifested on a sun-exposed area of her body.

MF and other cutaneous lymphomas should always be part of the differential diagnosis for an unexplained persistent rash, especially in a patient with a history of MF. The development of lymphomas is thought to be a stepwise process through which chronic antigenic stimulation results in an accumulation of genetic mutations that then cause cells to undergo clonal expansion and, ultimately, malignant transformation. Genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors that contribute to the disease pathogenesis have been identified.2

Once clinical features point toward MF, the diagnosis can be further differentiated from other benign inflammatory mimics with a biopsy demonstrating cerebriform lymphocytes homing toward the epidermis, monoclonal expansion of T cells, and defective apoptosis.3

Continue to: Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

The diagnosis of MF can be difficult as it often imitates other benign inflammatory conditions.

Rosacea manifests as an erythematous facial rash but usually spares the nasolabial folds and eyelids. There are several forms, including ocular (featuring swollen and irritated conjunctiva), erythematotelangiectatic (with visible blood vessels), and papulopustular (with acneic lesions). Over time, the skin may develop a thickened, bumpy texture, referred to as phymatous rosacea.4 A history of acute worsening with exposure to certain hot or spicy foods, alcohol, or ultraviolet light suggests a diagnosis of rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis classically presents as yellow scaling on a mildly erythematous base and often involves nasolabial folds and eyebrows. Seborrheic dermatitis can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic medical conditions.

Allergic contact dermatitis can look identical to MF, but in our case, there was no new allergen in the history. A thorough history regarding new medications, creams, and household supplies is integral to differentiating this diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis can lead to advanced-stage disease

This case of persistent facial erythema, originally treated as rosacea, highlights the importance of having a low threshold of suspicion of MF, especially in a patient with a prior history of MF. A recent study by Kelati et al3 indicated that certain subtypes of MF are easily misdiagnosed and treated as psoriasis or eczema respectively for an average of 10.5 years.3 These years of misdiagnosis are significantly correlated with the development of advanced-stage MF, which is more difficult to treat.3

Continue to: Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

There are multiple treatment options for MF, depending on the stage, starting with topical therapies and advancing to systemic therapies in more advanced stages. Topical treatments include steroids, nitrogen mustard, and retinoids.5 Our patient was referred to a multidisciplinary lymphoma clinic, where topical treatment was initiated with desonide cream .05% and mechlorethamine gel .016%. Our patient experienced a 50% improvement in skin involvement at 3 months.

As MF progresses to more advanced stages, treatment often combines skin-directed therapies with systemic immunomodulators, biologics, radiation, and total skin electron beam therapy.6 TSEBT is a low-dose full-body radiation treatment that targets the skin surface and therefore effectively treats cutaneous lymphoma. Although TSEBT is usually well tolerated, there have been documented acute and chronic adverse effects, including dermatitis, alopecia, peripheral edema, cutaneous malignancies, and infertility in men.7

While the use of topical desonide and mechlorethamine was initially favored over radiation due to eyelid involvement, our patient developed new patches on her legs 11 months after her initial visit. When biopsies indicated MF with large cell transformation, she received 1 course of low-dose TSEBT (12 Gy), with complete response noted at the 2 month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Seminario-Vidal, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL 33612; luciasem@usf.edu

1. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome). Part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

2. Wohl Y, Tur E. Environmental risk factors for mycosis fungoides. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2007;35:52-64.

3. Kelati A, Gallouj S, Tahiri L, et al. Defining the mimics and clinico-histological diagnosis criteria for mycosis fungoides to minimize misdiagnosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:100-106.

4. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

5. Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, et al. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:25-32.

6. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Continuing medical education: Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-e17.

7. De Moraes FY, Carvalho Hde A, Hanna SA, et al. Literature review of clinical results of total skin electron irradiation (TSEBT) of mycosis fungoides in adults. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19:92-98.

A 59-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a large asymptomatic facial rash that had developed several months earlier. The rash had been slowly growing but did not change day to day. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cutaneous lymphoma, which was localized to her arms. She denied the use of any new products, including hair or facial products, nail polish, or any new medications.

Initially, she was presumed (by an outside provider) to have rosacea, and she received treatment with doxycycline 100 mg/d for 2 months. However, the rash did not improve.

Physical examination revealed a large erythematous rash involving her cheeks, nose, and periocular area with no other significant findings (FIGURE).

A biopsy of her right cheek was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mycosis fungoides

Following the biopsy of her right cheek, a histopathologic analysis demonstrated an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate positive for CD3 and CD4. These histopathologic features led to a diagnosis of recurrent mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous lymphoma. (Our patient’s cutaneous lymphoma had been in remission for a year following local radiotherapy.)

MF is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, with an incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million people in the United States.1 There are also 2 rare subtypes of MF: the psoriasiform and palmoplantar forms. Psoriasiform MF presents with psoriasis-like plaques, while palmoplantar MF initially presents on the palms and soles.

Patients with classic MF typically present with patches and plaques—with the late evolution of tumors—on non–sun-exposed areas.1 Our patient’s clinical presentation was atypical because the rash manifested on a sun-exposed area of her body.

MF and other cutaneous lymphomas should always be part of the differential diagnosis for an unexplained persistent rash, especially in a patient with a history of MF. The development of lymphomas is thought to be a stepwise process through which chronic antigenic stimulation results in an accumulation of genetic mutations that then cause cells to undergo clonal expansion and, ultimately, malignant transformation. Genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors that contribute to the disease pathogenesis have been identified.2

Once clinical features point toward MF, the diagnosis can be further differentiated from other benign inflammatory mimics with a biopsy demonstrating cerebriform lymphocytes homing toward the epidermis, monoclonal expansion of T cells, and defective apoptosis.3

Continue to: Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

The diagnosis of MF can be difficult as it often imitates other benign inflammatory conditions.

Rosacea manifests as an erythematous facial rash but usually spares the nasolabial folds and eyelids. There are several forms, including ocular (featuring swollen and irritated conjunctiva), erythematotelangiectatic (with visible blood vessels), and papulopustular (with acneic lesions). Over time, the skin may develop a thickened, bumpy texture, referred to as phymatous rosacea.4 A history of acute worsening with exposure to certain hot or spicy foods, alcohol, or ultraviolet light suggests a diagnosis of rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis classically presents as yellow scaling on a mildly erythematous base and often involves nasolabial folds and eyebrows. Seborrheic dermatitis can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic medical conditions.

Allergic contact dermatitis can look identical to MF, but in our case, there was no new allergen in the history. A thorough history regarding new medications, creams, and household supplies is integral to differentiating this diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis can lead to advanced-stage disease

This case of persistent facial erythema, originally treated as rosacea, highlights the importance of having a low threshold of suspicion of MF, especially in a patient with a prior history of MF. A recent study by Kelati et al3 indicated that certain subtypes of MF are easily misdiagnosed and treated as psoriasis or eczema respectively for an average of 10.5 years.3 These years of misdiagnosis are significantly correlated with the development of advanced-stage MF, which is more difficult to treat.3

Continue to: Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

There are multiple treatment options for MF, depending on the stage, starting with topical therapies and advancing to systemic therapies in more advanced stages. Topical treatments include steroids, nitrogen mustard, and retinoids.5 Our patient was referred to a multidisciplinary lymphoma clinic, where topical treatment was initiated with desonide cream .05% and mechlorethamine gel .016%. Our patient experienced a 50% improvement in skin involvement at 3 months.

As MF progresses to more advanced stages, treatment often combines skin-directed therapies with systemic immunomodulators, biologics, radiation, and total skin electron beam therapy.6 TSEBT is a low-dose full-body radiation treatment that targets the skin surface and therefore effectively treats cutaneous lymphoma. Although TSEBT is usually well tolerated, there have been documented acute and chronic adverse effects, including dermatitis, alopecia, peripheral edema, cutaneous malignancies, and infertility in men.7

While the use of topical desonide and mechlorethamine was initially favored over radiation due to eyelid involvement, our patient developed new patches on her legs 11 months after her initial visit. When biopsies indicated MF with large cell transformation, she received 1 course of low-dose TSEBT (12 Gy), with complete response noted at the 2 month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Seminario-Vidal, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL 33612; luciasem@usf.edu

A 59-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a large asymptomatic facial rash that had developed several months earlier. The rash had been slowly growing but did not change day to day. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cutaneous lymphoma, which was localized to her arms. She denied the use of any new products, including hair or facial products, nail polish, or any new medications.

Initially, she was presumed (by an outside provider) to have rosacea, and she received treatment with doxycycline 100 mg/d for 2 months. However, the rash did not improve.

Physical examination revealed a large erythematous rash involving her cheeks, nose, and periocular area with no other significant findings (FIGURE).

A biopsy of her right cheek was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mycosis fungoides

Following the biopsy of her right cheek, a histopathologic analysis demonstrated an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate positive for CD3 and CD4. These histopathologic features led to a diagnosis of recurrent mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous lymphoma. (Our patient’s cutaneous lymphoma had been in remission for a year following local radiotherapy.)

MF is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, with an incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million people in the United States.1 There are also 2 rare subtypes of MF: the psoriasiform and palmoplantar forms. Psoriasiform MF presents with psoriasis-like plaques, while palmoplantar MF initially presents on the palms and soles.

Patients with classic MF typically present with patches and plaques—with the late evolution of tumors—on non–sun-exposed areas.1 Our patient’s clinical presentation was atypical because the rash manifested on a sun-exposed area of her body.

MF and other cutaneous lymphomas should always be part of the differential diagnosis for an unexplained persistent rash, especially in a patient with a history of MF. The development of lymphomas is thought to be a stepwise process through which chronic antigenic stimulation results in an accumulation of genetic mutations that then cause cells to undergo clonal expansion and, ultimately, malignant transformation. Genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors that contribute to the disease pathogenesis have been identified.2

Once clinical features point toward MF, the diagnosis can be further differentiated from other benign inflammatory mimics with a biopsy demonstrating cerebriform lymphocytes homing toward the epidermis, monoclonal expansion of T cells, and defective apoptosis.3

Continue to: Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

The diagnosis of MF can be difficult as it often imitates other benign inflammatory conditions.

Rosacea manifests as an erythematous facial rash but usually spares the nasolabial folds and eyelids. There are several forms, including ocular (featuring swollen and irritated conjunctiva), erythematotelangiectatic (with visible blood vessels), and papulopustular (with acneic lesions). Over time, the skin may develop a thickened, bumpy texture, referred to as phymatous rosacea.4 A history of acute worsening with exposure to certain hot or spicy foods, alcohol, or ultraviolet light suggests a diagnosis of rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis classically presents as yellow scaling on a mildly erythematous base and often involves nasolabial folds and eyebrows. Seborrheic dermatitis can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic medical conditions.

Allergic contact dermatitis can look identical to MF, but in our case, there was no new allergen in the history. A thorough history regarding new medications, creams, and household supplies is integral to differentiating this diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis can lead to advanced-stage disease

This case of persistent facial erythema, originally treated as rosacea, highlights the importance of having a low threshold of suspicion of MF, especially in a patient with a prior history of MF. A recent study by Kelati et al3 indicated that certain subtypes of MF are easily misdiagnosed and treated as psoriasis or eczema respectively for an average of 10.5 years.3 These years of misdiagnosis are significantly correlated with the development of advanced-stage MF, which is more difficult to treat.3

Continue to: Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

There are multiple treatment options for MF, depending on the stage, starting with topical therapies and advancing to systemic therapies in more advanced stages. Topical treatments include steroids, nitrogen mustard, and retinoids.5 Our patient was referred to a multidisciplinary lymphoma clinic, where topical treatment was initiated with desonide cream .05% and mechlorethamine gel .016%. Our patient experienced a 50% improvement in skin involvement at 3 months.

As MF progresses to more advanced stages, treatment often combines skin-directed therapies with systemic immunomodulators, biologics, radiation, and total skin electron beam therapy.6 TSEBT is a low-dose full-body radiation treatment that targets the skin surface and therefore effectively treats cutaneous lymphoma. Although TSEBT is usually well tolerated, there have been documented acute and chronic adverse effects, including dermatitis, alopecia, peripheral edema, cutaneous malignancies, and infertility in men.7

While the use of topical desonide and mechlorethamine was initially favored over radiation due to eyelid involvement, our patient developed new patches on her legs 11 months after her initial visit. When biopsies indicated MF with large cell transformation, she received 1 course of low-dose TSEBT (12 Gy), with complete response noted at the 2 month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Seminario-Vidal, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL 33612; luciasem@usf.edu

1. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome). Part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

2. Wohl Y, Tur E. Environmental risk factors for mycosis fungoides. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2007;35:52-64.

3. Kelati A, Gallouj S, Tahiri L, et al. Defining the mimics and clinico-histological diagnosis criteria for mycosis fungoides to minimize misdiagnosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:100-106.

4. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

5. Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, et al. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:25-32.

6. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Continuing medical education: Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-e17.

7. De Moraes FY, Carvalho Hde A, Hanna SA, et al. Literature review of clinical results of total skin electron irradiation (TSEBT) of mycosis fungoides in adults. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19:92-98.

1. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome). Part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

2. Wohl Y, Tur E. Environmental risk factors for mycosis fungoides. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2007;35:52-64.

3. Kelati A, Gallouj S, Tahiri L, et al. Defining the mimics and clinico-histological diagnosis criteria for mycosis fungoides to minimize misdiagnosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:100-106.

4. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

5. Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, et al. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:25-32.

6. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Continuing medical education: Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-e17.

7. De Moraes FY, Carvalho Hde A, Hanna SA, et al. Literature review of clinical results of total skin electron irradiation (TSEBT) of mycosis fungoides in adults. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19:92-98.

Metastatic Melanoma and Prostatic Adenocarcinoma in the Same Sentinel Lymph Node

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

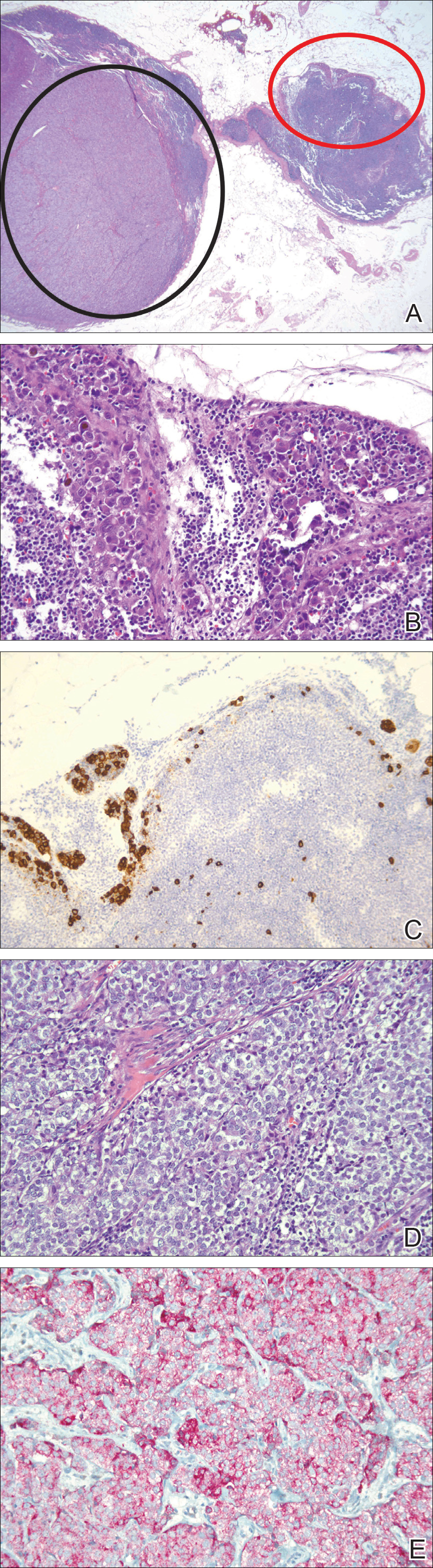

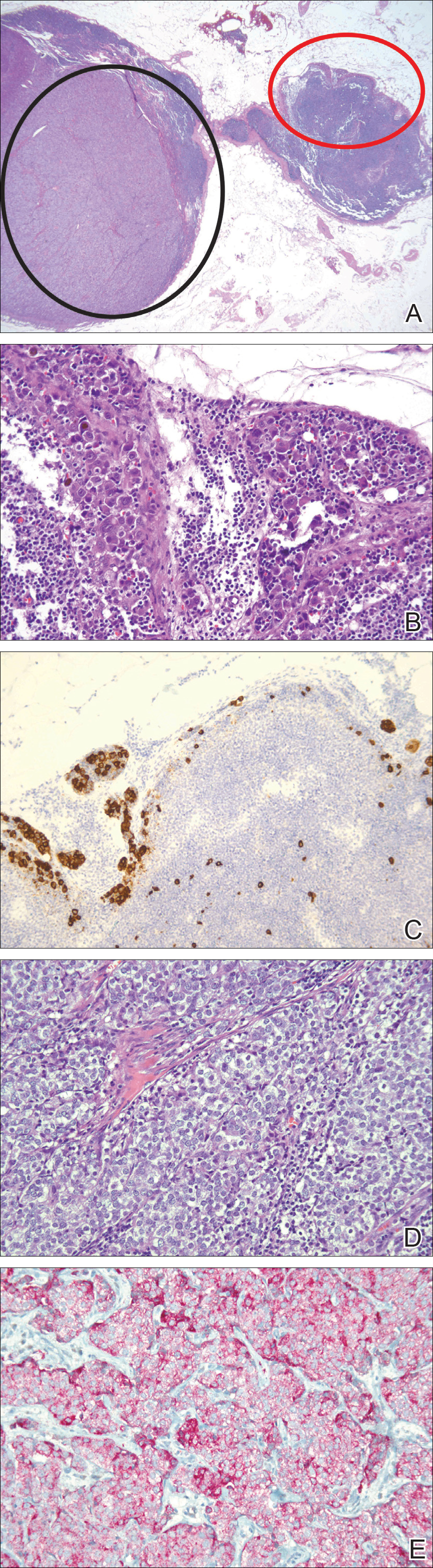

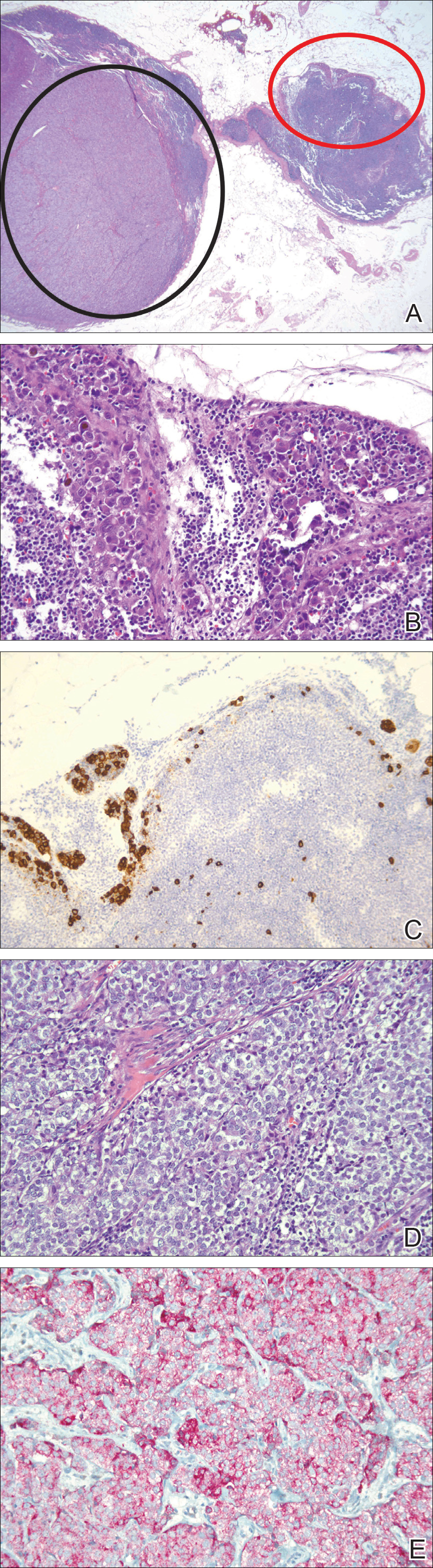

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

Practice Points

- Immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic sources of metastases.

- Thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease.