User login

Munchausen Syndrome by Adult Proxy

Asher first described Munchausen syndrome by proxy over 60 years ago. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always traveled widely; and their stories like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful.[1] Munchausen syndrome is a psychiatric disorder in which a patient intentionally induces or feigns symptoms of physical or psychiatric illness to assume the sick role. In 1977, Meadow described the first case in which a caregiverperpetrator deliberately produced physical symptoms in a child for proxy gratification.[2] Unlike malingering, in which external incentives drive conscious symptom falsification, Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is associated with fulfillment of the abuser's own psychological need for garnering praise from medical staff for devoted care given a sick child.[3, 4]

MSBP was once considered vanishingly rare. Many experts now believe it is more common, with a reported annual incidence of 0.4/100,000 in children younger than 16 years, and 2/100,000 in children younger than 1 year.[5] It is a disorder in which a parent, often the mother (94%99%)[6] and often with training or interest in the medical field,[5] is the perpetrator. The medical team caring for her child often views her as unusually helpful, and she is frequently psychiatrically ill with disorders such as depression, personality disorder, or prior personal history of somatoform or factitious disorder.[7, 8] The perpetrator typically inflicts physical harm, although occasionally she may simply lie about symptoms or tamper with laboratory samples.[5] The most common methods of inflicting harm are poisoning and suffocation. Overall mortality is 6% to 9%.[6, 9]

Although a large body of literature addresses pediatric cases, there is little to guide clinicians when victims are adults. An obvious reason may be that MSBP with adult proxies (MSB‐AP) has been reported so rarely, although we believe it is under‐recognized and more common than thought. The primary objective of this review was to identify all published cases of MSB‐AP, and synthesize them to characterize victims and perpetrators, modes of deceit, and relationships between victims and perpetrators so that clinicians will be better equipped to recognize such cases or at least include MSB‐AP in the differential of possibilities when symptoms and history are inconsistent.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study. The databases of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Knowledge, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through April 2014 to identify all published cases of Munchausen by proxy in patients 18 years or older. The following search terms were used: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, factitious disorder by proxy, Munchausen syndrome, and factitious disorder. Reports were included when they described single or multiple cases of MSBP with victims aged at least 18 years. The search was not limited to articles published in English. Bibliographies of selected articles were reviewed for reports identifying additional cases.

RESULTS

We found 10 reports describing 11 cases of MSB‐AP and 1 report describing 2 unique cases of MSB‐AP (Tables 1 and 2). Two case reports were published in French[10, 11] and 1 in Polish.[12] Sigal et al.[13] describes 2 different victims with a common perpetrator, and another report[14] describes the same perpetrator with a third victim. One case, though cited as MSB‐AP in the literature was excluded because it did not meet the criteria for the disorder. In this case, the wife of a 28‐year‐old alcoholic male poured acid on him while he was inebriated, ostensibly to vent frustration and coerce him into sobriety.[15, 16]

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Presenting Features | Occupation/Education | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | F | 20s | Abscesses (skin) | NP | Death |

| F | 21 | Abscesses (skin) | Child care | Paraplegia | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | NP | Rash | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | M | 69 | None | Retired businessman | Continued fabrication |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | M | 40s | Coma | Businessman | Abuse stopped |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | 73 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | 21 | NP | Developmental delay | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | 80 | Syncope | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | F | 82 | None | NP | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | M | 71 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | 23 | Rash | High school graduate | Continued abuse |

| F | 21 | Recurrent bacteremia | College student | Death | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | F | 79 | Fluid overload/false symptom history | Retired | Continued |

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Relationship | Occupation | Mode of Abuse | Outcome When Confronted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | M | 26 | Husbanda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration |

| M | 29 | Boyfrienda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | 34 | Cellmatea | Worked in medical clinic where incarcerated | Poisoningc followed by subcutaneous turpentine injection | Confession and attempted murder conviction |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | F | 55 | Companion | Nurse | False history of hematuria, weakness, headaches | Denial |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | F | 47 | Wife | Nurse | Tranquilizer injections | Confession and placed on probation |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | NP | Daughter | Nurse | Insulin injections | Denial |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | NP | Mother | Business woman | False history of Batten's disease | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | NP | Granddaughter | NP | Poisoningb | Denial |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | M | NP | Son | NP | False history of memory loss | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | F | NP | Wife | Hospital employee | Poisoningb | Confession |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | NP | Mother | Unemployed chronic medical problems | Toxin application to skin | Denial |

| F | NP | Mother | Medical office receptionist | Intravenous injection unknown substance | Denial | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | M | NP | Son | NP | Fluid administration in context of fluid restriction/erratic medication administration/falsifying severity of symptoms | Denial |

Of the 13 victims, 9 (69%) were women and 4 (31%) were men. Of the ages reported, the median age was 69 years and the mean age was 51 (range, 2182 years). Exact age was not reported in 3 cases. Lying about signs and symptoms, but not actually inducing injury, occurred in 3 cases (23%), whereas in 10 cases (77%), the victims presented with physical findings, including coma (3), rash (2), skin abscesses (2), syncope (1), recurrent bacteremia (1), and fluid overload (1). Seven (54%) of the victims were poisoned, 2 via drug injection and 5 by beverage/food contamination. A perpetrator sedated 3 victims and subsequently injected them, 2 with gasoline and another with turpentine. Two of the victims were involved in business, 1 worked in childcare, 1 attended beauty school after graduating from high school, 1 attended college, and 1 was developmentally delayed. Victim education or occupation was not reported in 7 cases.

Of the 11 perpetrators, 8 (73%) were women, and 3 (27%) were men (note that the same male perpetrator had 3 victims). Median age was 34 years (range, 2655 years), although exact age was not reported in 4 cases. The perpetrator was the victim's mother in 3 cases, wife in 2 cases, son in 2 cases, and daughter, granddaughter, husband, companion, boyfriend, or prison cellmate in 1 case each. Five (38%) worked in healthcare.

All of the perpetrators were highly involved, even overly involved, in the care of their victims, frequently present, sometimes hovering, in hospital settings, and were viewed as generally helpful, if not overintrusive, by hospital staff. When confronted, 3 perpetrators confessed, 3 denied abuse that then ceased, and 4 more denied abuse that continued, culminating in death in 1 case. In 1 case, the outcome was not reported.[8] At least 3 victims remained with their perpetrators. Two perpetrators were criminally charged, 1 receiving probation and the other incarceration. The latter began abusing his cellmate, behavior that did not stop until he was confronted in prison.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to locate and review all published cases of MSB‐AP. Our secondary aim was to describe salient characteristics of perpetrators, victims, and fabricated diseases in hopes of helping clinicians better recognize this disorder.

Our review shows that perpetrators were exclusively the victims' caregivers, including mothers, wives, husbands, daughters, granddaughters, or companions. These perpetrators, many with healthcare backgrounds, were attentive, helpful, and excessively present. In the majority of cases, hidden physical abuse yielded visible disease. Less commonly, perpetrators lied about symptoms rather than actually creating signs of disease. The most common mode of disease instigation involved poisoning through beverage/food contamination or subcutaneous injection. Geriatric and developmentally delayed persons appeared particularly vulnerable to victimization. Of the 13 victims, 5 were geriatric and 1 was developmentally delayed.

The adult cases we report are similar to child cases in that the perpetrators are caregivers; however, the caregivers of the adults are a more diverse group. Other similarities between adult and child cases are that physical signs occur more often than simply falsifying information, and poisoning is the most common method of disease fabrication. Suffocation, although common in child cases, has not been reported in adults. Though present in only a minority of cases, another feature distinguishing these cases from those reported in the pediatric literature is the presence of collusion between the perpetrator and victim. When MSBP was first described, Meadow believed that victims would reach an age at which the disorder would cease because they would fight back or report the abuse.[2] In 7 of the adult cases, the victims were unknowingly poisoned; however, in 2 cases,[17] the victims knew what their mothers were doing to them and yet denied that they were harming them. To explain this collusion, Deimel et al. proposed Stockholm syndrome, a condition in which a victim holds a perpetrator in high regard, despite experiencing at their hands what others might consider brainwashing and torture.

The data from the individual cases are sometimes frustratingly incomplete, with inconsistent reporting of dyad demographics and outcomes across the 13 cases, which compromises efforts to compare and contrast them. However, because no published studies have thoroughly reviewed all existing cases of MSB‐AP, we believe our review provides important insights into this condition by consolidating available information. It is our hope that by characterizing perpetrators, victims, and common presentations, we will raise awareness about this condition among healthcare providers so that it may be included in the differential diagnosis when they encounter this dyad: a patient's medical problems do not respond as expected to therapy and a caregivers appears overly involved or attention seeking.

The diagnosis of a factitious disorder often presents an immense clinical challenge and generally involves a multidisciplinary approach.[18] In addition to the incomplete data for existing cases in the literature, we recognize the ongoing difficulties in precise diagnosis of this disorder. Because a hallmark of pathology is secrecy at the outset and often denial, and even abrupt transition of care, upon confrontation, it is often very difficult, especially early on, to uncover patterns of perpetration, let alone posit a motive. We recognize that there may be some perpetrators who are motivated by something other than purely psychological end points, such as financial reward or even sexual victimization. And when alternate care venues are sought, clinicians are often left wondering. Further, the damage that may come to a therapeutic relationship by prematurely diagnosing MSB‐AP is important to keep in mind. Hospitalists who suspect MSB‐AP should consult psychiatry. Although MSB‐AP is a diagnosis of exclusion and often based on circumstantial evidence, psychiatry can assist in diagnosing this disorder and, in the event of a confession, provide immediate therapeutic intervention. Social services can aid in a vulnerable adult investigation for patients who do not have capacity.

When Meadow first described MSBP, he ended his article by asking Is this degree of falsification rare or is it under‐recognized? Time has answered Meadow's question. Now we ask the same question with regard to MSB‐AP, is it rare or under‐recognized? We must remain vigilant for this disorder. Early recognition can prevent healthcare providers from unknowingly perpetuating victimization by treating caregiver‐induced pathology as if legitimate, thereby satisfying the perpetrator's psychological needs. Despite Meadow's assertion that proxies outgrow their victimization, our review warns that advanced age does not preclude vulnerability and in some cases, may actually increase it. In the future, the incidence and prevalence of MSB‐AP is likely to increase as medical technology allows greater survival of cognitively impaired populations who are dependent on others for care. The elderly and developmentally delayed may be especially at risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.C.B., M.B.W., and M.I.L. report no conflicts of interest. J.M.B. receives payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from nonprofit continuing medical education organizations and universities for occasional lectures; however, this funding is not relevant to this review.

- . Munchausen syndrome. Lancet. 1951(1):339–341.

- . Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343–345.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

- , , , et al. Position paper: definitional issues in Munchausen by proxy. Child Maltreat. 2002;7(2):105–111.

- , , , . Epidemiology of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, non‐accidental poisoning, and non‐accidental suffocation. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(1):57–61.

- . Web of deceit: a literature review of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(4):547–563.

- , . Psychopathology of perpetrators of fabricated or induced illness in children: case series. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(2):113–118.

- , . The central venous catheter as a source of medical chaos in Munchausen syndrome by proxy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(4):623–627.

- , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: diagnosis and prevalence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):318–321.

- , , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy between two adults [in French]. Presse Med. 1996;25(12):583–586.

- , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy in an old woman [in French]. Revue Geriatr. 2003;28:425–428.

- , , , . Consciousness disturbances: a case report of Munchausen by proxy syndrome in an elderly patient [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2003;60(4):307–308.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy: a perpetrator abusing two adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(11):696–698.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy revisited. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1991;28(1):33–36.

- , , , , , . Otolaryngology fantastica: the ear, nose, and throat manifestations of Munchausen's syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):51–57.

- . Witchcraft's syndrome: Munchausen's syndrome by proxy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(3):229–230.

- , , , , , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: an adult dyad. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):294–299.

- , . Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422–1432.

- , . More in sickness than in health: a case study of Munchausen by proxy in the elderly. J Fam Ther. 1989;11(4):321–334.

- , . Recurrent hypoglycaemia in multiple myeloma: a case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy in an elderly patient. J Intern Med. 1998;244(2):175–178.

- , , , , . Idiopathic recurrent stupor: a warning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):368–369.

- , , . Munchausen by proxy in older adults: A case report. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):178–181.

Asher first described Munchausen syndrome by proxy over 60 years ago. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always traveled widely; and their stories like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful.[1] Munchausen syndrome is a psychiatric disorder in which a patient intentionally induces or feigns symptoms of physical or psychiatric illness to assume the sick role. In 1977, Meadow described the first case in which a caregiverperpetrator deliberately produced physical symptoms in a child for proxy gratification.[2] Unlike malingering, in which external incentives drive conscious symptom falsification, Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is associated with fulfillment of the abuser's own psychological need for garnering praise from medical staff for devoted care given a sick child.[3, 4]

MSBP was once considered vanishingly rare. Many experts now believe it is more common, with a reported annual incidence of 0.4/100,000 in children younger than 16 years, and 2/100,000 in children younger than 1 year.[5] It is a disorder in which a parent, often the mother (94%99%)[6] and often with training or interest in the medical field,[5] is the perpetrator. The medical team caring for her child often views her as unusually helpful, and she is frequently psychiatrically ill with disorders such as depression, personality disorder, or prior personal history of somatoform or factitious disorder.[7, 8] The perpetrator typically inflicts physical harm, although occasionally she may simply lie about symptoms or tamper with laboratory samples.[5] The most common methods of inflicting harm are poisoning and suffocation. Overall mortality is 6% to 9%.[6, 9]

Although a large body of literature addresses pediatric cases, there is little to guide clinicians when victims are adults. An obvious reason may be that MSBP with adult proxies (MSB‐AP) has been reported so rarely, although we believe it is under‐recognized and more common than thought. The primary objective of this review was to identify all published cases of MSB‐AP, and synthesize them to characterize victims and perpetrators, modes of deceit, and relationships between victims and perpetrators so that clinicians will be better equipped to recognize such cases or at least include MSB‐AP in the differential of possibilities when symptoms and history are inconsistent.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study. The databases of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Knowledge, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through April 2014 to identify all published cases of Munchausen by proxy in patients 18 years or older. The following search terms were used: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, factitious disorder by proxy, Munchausen syndrome, and factitious disorder. Reports were included when they described single or multiple cases of MSBP with victims aged at least 18 years. The search was not limited to articles published in English. Bibliographies of selected articles were reviewed for reports identifying additional cases.

RESULTS

We found 10 reports describing 11 cases of MSB‐AP and 1 report describing 2 unique cases of MSB‐AP (Tables 1 and 2). Two case reports were published in French[10, 11] and 1 in Polish.[12] Sigal et al.[13] describes 2 different victims with a common perpetrator, and another report[14] describes the same perpetrator with a third victim. One case, though cited as MSB‐AP in the literature was excluded because it did not meet the criteria for the disorder. In this case, the wife of a 28‐year‐old alcoholic male poured acid on him while he was inebriated, ostensibly to vent frustration and coerce him into sobriety.[15, 16]

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Presenting Features | Occupation/Education | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | F | 20s | Abscesses (skin) | NP | Death |

| F | 21 | Abscesses (skin) | Child care | Paraplegia | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | NP | Rash | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | M | 69 | None | Retired businessman | Continued fabrication |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | M | 40s | Coma | Businessman | Abuse stopped |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | 73 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | 21 | NP | Developmental delay | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | 80 | Syncope | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | F | 82 | None | NP | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | M | 71 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | 23 | Rash | High school graduate | Continued abuse |

| F | 21 | Recurrent bacteremia | College student | Death | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | F | 79 | Fluid overload/false symptom history | Retired | Continued |

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Relationship | Occupation | Mode of Abuse | Outcome When Confronted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | M | 26 | Husbanda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration |

| M | 29 | Boyfrienda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | 34 | Cellmatea | Worked in medical clinic where incarcerated | Poisoningc followed by subcutaneous turpentine injection | Confession and attempted murder conviction |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | F | 55 | Companion | Nurse | False history of hematuria, weakness, headaches | Denial |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | F | 47 | Wife | Nurse | Tranquilizer injections | Confession and placed on probation |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | NP | Daughter | Nurse | Insulin injections | Denial |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | NP | Mother | Business woman | False history of Batten's disease | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | NP | Granddaughter | NP | Poisoningb | Denial |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | M | NP | Son | NP | False history of memory loss | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | F | NP | Wife | Hospital employee | Poisoningb | Confession |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | NP | Mother | Unemployed chronic medical problems | Toxin application to skin | Denial |

| F | NP | Mother | Medical office receptionist | Intravenous injection unknown substance | Denial | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | M | NP | Son | NP | Fluid administration in context of fluid restriction/erratic medication administration/falsifying severity of symptoms | Denial |

Of the 13 victims, 9 (69%) were women and 4 (31%) were men. Of the ages reported, the median age was 69 years and the mean age was 51 (range, 2182 years). Exact age was not reported in 3 cases. Lying about signs and symptoms, but not actually inducing injury, occurred in 3 cases (23%), whereas in 10 cases (77%), the victims presented with physical findings, including coma (3), rash (2), skin abscesses (2), syncope (1), recurrent bacteremia (1), and fluid overload (1). Seven (54%) of the victims were poisoned, 2 via drug injection and 5 by beverage/food contamination. A perpetrator sedated 3 victims and subsequently injected them, 2 with gasoline and another with turpentine. Two of the victims were involved in business, 1 worked in childcare, 1 attended beauty school after graduating from high school, 1 attended college, and 1 was developmentally delayed. Victim education or occupation was not reported in 7 cases.

Of the 11 perpetrators, 8 (73%) were women, and 3 (27%) were men (note that the same male perpetrator had 3 victims). Median age was 34 years (range, 2655 years), although exact age was not reported in 4 cases. The perpetrator was the victim's mother in 3 cases, wife in 2 cases, son in 2 cases, and daughter, granddaughter, husband, companion, boyfriend, or prison cellmate in 1 case each. Five (38%) worked in healthcare.

All of the perpetrators were highly involved, even overly involved, in the care of their victims, frequently present, sometimes hovering, in hospital settings, and were viewed as generally helpful, if not overintrusive, by hospital staff. When confronted, 3 perpetrators confessed, 3 denied abuse that then ceased, and 4 more denied abuse that continued, culminating in death in 1 case. In 1 case, the outcome was not reported.[8] At least 3 victims remained with their perpetrators. Two perpetrators were criminally charged, 1 receiving probation and the other incarceration. The latter began abusing his cellmate, behavior that did not stop until he was confronted in prison.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to locate and review all published cases of MSB‐AP. Our secondary aim was to describe salient characteristics of perpetrators, victims, and fabricated diseases in hopes of helping clinicians better recognize this disorder.

Our review shows that perpetrators were exclusively the victims' caregivers, including mothers, wives, husbands, daughters, granddaughters, or companions. These perpetrators, many with healthcare backgrounds, were attentive, helpful, and excessively present. In the majority of cases, hidden physical abuse yielded visible disease. Less commonly, perpetrators lied about symptoms rather than actually creating signs of disease. The most common mode of disease instigation involved poisoning through beverage/food contamination or subcutaneous injection. Geriatric and developmentally delayed persons appeared particularly vulnerable to victimization. Of the 13 victims, 5 were geriatric and 1 was developmentally delayed.

The adult cases we report are similar to child cases in that the perpetrators are caregivers; however, the caregivers of the adults are a more diverse group. Other similarities between adult and child cases are that physical signs occur more often than simply falsifying information, and poisoning is the most common method of disease fabrication. Suffocation, although common in child cases, has not been reported in adults. Though present in only a minority of cases, another feature distinguishing these cases from those reported in the pediatric literature is the presence of collusion between the perpetrator and victim. When MSBP was first described, Meadow believed that victims would reach an age at which the disorder would cease because they would fight back or report the abuse.[2] In 7 of the adult cases, the victims were unknowingly poisoned; however, in 2 cases,[17] the victims knew what their mothers were doing to them and yet denied that they were harming them. To explain this collusion, Deimel et al. proposed Stockholm syndrome, a condition in which a victim holds a perpetrator in high regard, despite experiencing at their hands what others might consider brainwashing and torture.

The data from the individual cases are sometimes frustratingly incomplete, with inconsistent reporting of dyad demographics and outcomes across the 13 cases, which compromises efforts to compare and contrast them. However, because no published studies have thoroughly reviewed all existing cases of MSB‐AP, we believe our review provides important insights into this condition by consolidating available information. It is our hope that by characterizing perpetrators, victims, and common presentations, we will raise awareness about this condition among healthcare providers so that it may be included in the differential diagnosis when they encounter this dyad: a patient's medical problems do not respond as expected to therapy and a caregivers appears overly involved or attention seeking.

The diagnosis of a factitious disorder often presents an immense clinical challenge and generally involves a multidisciplinary approach.[18] In addition to the incomplete data for existing cases in the literature, we recognize the ongoing difficulties in precise diagnosis of this disorder. Because a hallmark of pathology is secrecy at the outset and often denial, and even abrupt transition of care, upon confrontation, it is often very difficult, especially early on, to uncover patterns of perpetration, let alone posit a motive. We recognize that there may be some perpetrators who are motivated by something other than purely psychological end points, such as financial reward or even sexual victimization. And when alternate care venues are sought, clinicians are often left wondering. Further, the damage that may come to a therapeutic relationship by prematurely diagnosing MSB‐AP is important to keep in mind. Hospitalists who suspect MSB‐AP should consult psychiatry. Although MSB‐AP is a diagnosis of exclusion and often based on circumstantial evidence, psychiatry can assist in diagnosing this disorder and, in the event of a confession, provide immediate therapeutic intervention. Social services can aid in a vulnerable adult investigation for patients who do not have capacity.

When Meadow first described MSBP, he ended his article by asking Is this degree of falsification rare or is it under‐recognized? Time has answered Meadow's question. Now we ask the same question with regard to MSB‐AP, is it rare or under‐recognized? We must remain vigilant for this disorder. Early recognition can prevent healthcare providers from unknowingly perpetuating victimization by treating caregiver‐induced pathology as if legitimate, thereby satisfying the perpetrator's psychological needs. Despite Meadow's assertion that proxies outgrow their victimization, our review warns that advanced age does not preclude vulnerability and in some cases, may actually increase it. In the future, the incidence and prevalence of MSB‐AP is likely to increase as medical technology allows greater survival of cognitively impaired populations who are dependent on others for care. The elderly and developmentally delayed may be especially at risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.C.B., M.B.W., and M.I.L. report no conflicts of interest. J.M.B. receives payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from nonprofit continuing medical education organizations and universities for occasional lectures; however, this funding is not relevant to this review.

Asher first described Munchausen syndrome by proxy over 60 years ago. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always traveled widely; and their stories like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful.[1] Munchausen syndrome is a psychiatric disorder in which a patient intentionally induces or feigns symptoms of physical or psychiatric illness to assume the sick role. In 1977, Meadow described the first case in which a caregiverperpetrator deliberately produced physical symptoms in a child for proxy gratification.[2] Unlike malingering, in which external incentives drive conscious symptom falsification, Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is associated with fulfillment of the abuser's own psychological need for garnering praise from medical staff for devoted care given a sick child.[3, 4]

MSBP was once considered vanishingly rare. Many experts now believe it is more common, with a reported annual incidence of 0.4/100,000 in children younger than 16 years, and 2/100,000 in children younger than 1 year.[5] It is a disorder in which a parent, often the mother (94%99%)[6] and often with training or interest in the medical field,[5] is the perpetrator. The medical team caring for her child often views her as unusually helpful, and she is frequently psychiatrically ill with disorders such as depression, personality disorder, or prior personal history of somatoform or factitious disorder.[7, 8] The perpetrator typically inflicts physical harm, although occasionally she may simply lie about symptoms or tamper with laboratory samples.[5] The most common methods of inflicting harm are poisoning and suffocation. Overall mortality is 6% to 9%.[6, 9]

Although a large body of literature addresses pediatric cases, there is little to guide clinicians when victims are adults. An obvious reason may be that MSBP with adult proxies (MSB‐AP) has been reported so rarely, although we believe it is under‐recognized and more common than thought. The primary objective of this review was to identify all published cases of MSB‐AP, and synthesize them to characterize victims and perpetrators, modes of deceit, and relationships between victims and perpetrators so that clinicians will be better equipped to recognize such cases or at least include MSB‐AP in the differential of possibilities when symptoms and history are inconsistent.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study. The databases of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Knowledge, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through April 2014 to identify all published cases of Munchausen by proxy in patients 18 years or older. The following search terms were used: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, factitious disorder by proxy, Munchausen syndrome, and factitious disorder. Reports were included when they described single or multiple cases of MSBP with victims aged at least 18 years. The search was not limited to articles published in English. Bibliographies of selected articles were reviewed for reports identifying additional cases.

RESULTS

We found 10 reports describing 11 cases of MSB‐AP and 1 report describing 2 unique cases of MSB‐AP (Tables 1 and 2). Two case reports were published in French[10, 11] and 1 in Polish.[12] Sigal et al.[13] describes 2 different victims with a common perpetrator, and another report[14] describes the same perpetrator with a third victim. One case, though cited as MSB‐AP in the literature was excluded because it did not meet the criteria for the disorder. In this case, the wife of a 28‐year‐old alcoholic male poured acid on him while he was inebriated, ostensibly to vent frustration and coerce him into sobriety.[15, 16]

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Presenting Features | Occupation/Education | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | F | 20s | Abscesses (skin) | NP | Death |

| F | 21 | Abscesses (skin) | Child care | Paraplegia | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | NP | Rash | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | M | 69 | None | Retired businessman | Continued fabrication |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | M | 40s | Coma | Businessman | Abuse stopped |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | 73 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | 21 | NP | Developmental delay | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | 80 | Syncope | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | F | 82 | None | NP | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | M | 71 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | 23 | Rash | High school graduate | Continued abuse |

| F | 21 | Recurrent bacteremia | College student | Death | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | F | 79 | Fluid overload/false symptom history | Retired | Continued |

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Relationship | Occupation | Mode of Abuse | Outcome When Confronted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | M | 26 | Husbanda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration |

| M | 29 | Boyfrienda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | 34 | Cellmatea | Worked in medical clinic where incarcerated | Poisoningc followed by subcutaneous turpentine injection | Confession and attempted murder conviction |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | F | 55 | Companion | Nurse | False history of hematuria, weakness, headaches | Denial |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | F | 47 | Wife | Nurse | Tranquilizer injections | Confession and placed on probation |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | NP | Daughter | Nurse | Insulin injections | Denial |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | NP | Mother | Business woman | False history of Batten's disease | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | NP | Granddaughter | NP | Poisoningb | Denial |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | M | NP | Son | NP | False history of memory loss | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | F | NP | Wife | Hospital employee | Poisoningb | Confession |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | NP | Mother | Unemployed chronic medical problems | Toxin application to skin | Denial |

| F | NP | Mother | Medical office receptionist | Intravenous injection unknown substance | Denial | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | M | NP | Son | NP | Fluid administration in context of fluid restriction/erratic medication administration/falsifying severity of symptoms | Denial |

Of the 13 victims, 9 (69%) were women and 4 (31%) were men. Of the ages reported, the median age was 69 years and the mean age was 51 (range, 2182 years). Exact age was not reported in 3 cases. Lying about signs and symptoms, but not actually inducing injury, occurred in 3 cases (23%), whereas in 10 cases (77%), the victims presented with physical findings, including coma (3), rash (2), skin abscesses (2), syncope (1), recurrent bacteremia (1), and fluid overload (1). Seven (54%) of the victims were poisoned, 2 via drug injection and 5 by beverage/food contamination. A perpetrator sedated 3 victims and subsequently injected them, 2 with gasoline and another with turpentine. Two of the victims were involved in business, 1 worked in childcare, 1 attended beauty school after graduating from high school, 1 attended college, and 1 was developmentally delayed. Victim education or occupation was not reported in 7 cases.

Of the 11 perpetrators, 8 (73%) were women, and 3 (27%) were men (note that the same male perpetrator had 3 victims). Median age was 34 years (range, 2655 years), although exact age was not reported in 4 cases. The perpetrator was the victim's mother in 3 cases, wife in 2 cases, son in 2 cases, and daughter, granddaughter, husband, companion, boyfriend, or prison cellmate in 1 case each. Five (38%) worked in healthcare.

All of the perpetrators were highly involved, even overly involved, in the care of their victims, frequently present, sometimes hovering, in hospital settings, and were viewed as generally helpful, if not overintrusive, by hospital staff. When confronted, 3 perpetrators confessed, 3 denied abuse that then ceased, and 4 more denied abuse that continued, culminating in death in 1 case. In 1 case, the outcome was not reported.[8] At least 3 victims remained with their perpetrators. Two perpetrators were criminally charged, 1 receiving probation and the other incarceration. The latter began abusing his cellmate, behavior that did not stop until he was confronted in prison.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to locate and review all published cases of MSB‐AP. Our secondary aim was to describe salient characteristics of perpetrators, victims, and fabricated diseases in hopes of helping clinicians better recognize this disorder.

Our review shows that perpetrators were exclusively the victims' caregivers, including mothers, wives, husbands, daughters, granddaughters, or companions. These perpetrators, many with healthcare backgrounds, were attentive, helpful, and excessively present. In the majority of cases, hidden physical abuse yielded visible disease. Less commonly, perpetrators lied about symptoms rather than actually creating signs of disease. The most common mode of disease instigation involved poisoning through beverage/food contamination or subcutaneous injection. Geriatric and developmentally delayed persons appeared particularly vulnerable to victimization. Of the 13 victims, 5 were geriatric and 1 was developmentally delayed.

The adult cases we report are similar to child cases in that the perpetrators are caregivers; however, the caregivers of the adults are a more diverse group. Other similarities between adult and child cases are that physical signs occur more often than simply falsifying information, and poisoning is the most common method of disease fabrication. Suffocation, although common in child cases, has not been reported in adults. Though present in only a minority of cases, another feature distinguishing these cases from those reported in the pediatric literature is the presence of collusion between the perpetrator and victim. When MSBP was first described, Meadow believed that victims would reach an age at which the disorder would cease because they would fight back or report the abuse.[2] In 7 of the adult cases, the victims were unknowingly poisoned; however, in 2 cases,[17] the victims knew what their mothers were doing to them and yet denied that they were harming them. To explain this collusion, Deimel et al. proposed Stockholm syndrome, a condition in which a victim holds a perpetrator in high regard, despite experiencing at their hands what others might consider brainwashing and torture.

The data from the individual cases are sometimes frustratingly incomplete, with inconsistent reporting of dyad demographics and outcomes across the 13 cases, which compromises efforts to compare and contrast them. However, because no published studies have thoroughly reviewed all existing cases of MSB‐AP, we believe our review provides important insights into this condition by consolidating available information. It is our hope that by characterizing perpetrators, victims, and common presentations, we will raise awareness about this condition among healthcare providers so that it may be included in the differential diagnosis when they encounter this dyad: a patient's medical problems do not respond as expected to therapy and a caregivers appears overly involved or attention seeking.

The diagnosis of a factitious disorder often presents an immense clinical challenge and generally involves a multidisciplinary approach.[18] In addition to the incomplete data for existing cases in the literature, we recognize the ongoing difficulties in precise diagnosis of this disorder. Because a hallmark of pathology is secrecy at the outset and often denial, and even abrupt transition of care, upon confrontation, it is often very difficult, especially early on, to uncover patterns of perpetration, let alone posit a motive. We recognize that there may be some perpetrators who are motivated by something other than purely psychological end points, such as financial reward or even sexual victimization. And when alternate care venues are sought, clinicians are often left wondering. Further, the damage that may come to a therapeutic relationship by prematurely diagnosing MSB‐AP is important to keep in mind. Hospitalists who suspect MSB‐AP should consult psychiatry. Although MSB‐AP is a diagnosis of exclusion and often based on circumstantial evidence, psychiatry can assist in diagnosing this disorder and, in the event of a confession, provide immediate therapeutic intervention. Social services can aid in a vulnerable adult investigation for patients who do not have capacity.

When Meadow first described MSBP, he ended his article by asking Is this degree of falsification rare or is it under‐recognized? Time has answered Meadow's question. Now we ask the same question with regard to MSB‐AP, is it rare or under‐recognized? We must remain vigilant for this disorder. Early recognition can prevent healthcare providers from unknowingly perpetuating victimization by treating caregiver‐induced pathology as if legitimate, thereby satisfying the perpetrator's psychological needs. Despite Meadow's assertion that proxies outgrow their victimization, our review warns that advanced age does not preclude vulnerability and in some cases, may actually increase it. In the future, the incidence and prevalence of MSB‐AP is likely to increase as medical technology allows greater survival of cognitively impaired populations who are dependent on others for care. The elderly and developmentally delayed may be especially at risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.C.B., M.B.W., and M.I.L. report no conflicts of interest. J.M.B. receives payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from nonprofit continuing medical education organizations and universities for occasional lectures; however, this funding is not relevant to this review.

- . Munchausen syndrome. Lancet. 1951(1):339–341.

- . Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343–345.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

- , , , et al. Position paper: definitional issues in Munchausen by proxy. Child Maltreat. 2002;7(2):105–111.

- , , , . Epidemiology of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, non‐accidental poisoning, and non‐accidental suffocation. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(1):57–61.

- . Web of deceit: a literature review of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(4):547–563.

- , . Psychopathology of perpetrators of fabricated or induced illness in children: case series. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(2):113–118.

- , . The central venous catheter as a source of medical chaos in Munchausen syndrome by proxy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(4):623–627.

- , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: diagnosis and prevalence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):318–321.

- , , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy between two adults [in French]. Presse Med. 1996;25(12):583–586.

- , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy in an old woman [in French]. Revue Geriatr. 2003;28:425–428.

- , , , . Consciousness disturbances: a case report of Munchausen by proxy syndrome in an elderly patient [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2003;60(4):307–308.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy: a perpetrator abusing two adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(11):696–698.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy revisited. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1991;28(1):33–36.

- , , , , , . Otolaryngology fantastica: the ear, nose, and throat manifestations of Munchausen's syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):51–57.

- . Witchcraft's syndrome: Munchausen's syndrome by proxy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(3):229–230.

- , , , , , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: an adult dyad. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):294–299.

- , . Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422–1432.

- , . More in sickness than in health: a case study of Munchausen by proxy in the elderly. J Fam Ther. 1989;11(4):321–334.

- , . Recurrent hypoglycaemia in multiple myeloma: a case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy in an elderly patient. J Intern Med. 1998;244(2):175–178.

- , , , , . Idiopathic recurrent stupor: a warning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):368–369.

- , , . Munchausen by proxy in older adults: A case report. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):178–181.

- . Munchausen syndrome. Lancet. 1951(1):339–341.

- . Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343–345.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

- , , , et al. Position paper: definitional issues in Munchausen by proxy. Child Maltreat. 2002;7(2):105–111.

- , , , . Epidemiology of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, non‐accidental poisoning, and non‐accidental suffocation. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(1):57–61.

- . Web of deceit: a literature review of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(4):547–563.

- , . Psychopathology of perpetrators of fabricated or induced illness in children: case series. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(2):113–118.

- , . The central venous catheter as a source of medical chaos in Munchausen syndrome by proxy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(4):623–627.

- , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: diagnosis and prevalence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):318–321.

- , , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy between two adults [in French]. Presse Med. 1996;25(12):583–586.

- , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy in an old woman [in French]. Revue Geriatr. 2003;28:425–428.

- , , , . Consciousness disturbances: a case report of Munchausen by proxy syndrome in an elderly patient [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2003;60(4):307–308.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy: a perpetrator abusing two adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(11):696–698.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy revisited. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1991;28(1):33–36.

- , , , , , . Otolaryngology fantastica: the ear, nose, and throat manifestations of Munchausen's syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):51–57.

- . Witchcraft's syndrome: Munchausen's syndrome by proxy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(3):229–230.

- , , , , , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: an adult dyad. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):294–299.

- , . Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422–1432.

- , . More in sickness than in health: a case study of Munchausen by proxy in the elderly. J Fam Ther. 1989;11(4):321–334.

- , . Recurrent hypoglycaemia in multiple myeloma: a case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy in an elderly patient. J Intern Med. 1998;244(2):175–178.

- , , , , . Idiopathic recurrent stupor: a warning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):368–369.

- , , . Munchausen by proxy in older adults: A case report. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):178–181.

© 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine

Let the "script" of your patient's suicide attempt help you plan effective treatment

The ‘meth’ epidemic: Managing acute psychosis, agitation, and suicide risk

Methamphetamine abuse has spread to every region of the United States in the past 10 years (Table 1).1 Its long-lasting, difficult-to-treat medical effects destroy lives and create psychiatric and physical comorbidities that confound clinicians in emergency rooms and community practice settings.

This first in a series of two articles describes methamphetamine’s growing use and offers guidance to identify abusers and manage acute “meth” intoxication. Methamphetamine-abusing patients can appear in any area of acute psychiatric practice—during emergency department (ED) evaluations, medical-surgical consultations, and inpatient psychiatric admissions. Using case examples, we describe key clinical principles to help you assess patients in each of these settings.

Table 1

10-year growth in hospitalization rates

for methamphetamine/amphetamine use*

| Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | 1993 | 2003 |

| U.S. national rate | 13 | 56 |

| Northeast | ||

| Connecticut | 1 | 4 |

| Maine | 2 | 5 |

| Massachusetts | <1 | 2 |

| New Hampshire | <1 | 2 |

| New Jersey | 3 | 2 |

| New York | 2 | 4 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 2 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | 2 |

| Vermont | 5 | 4 |

| South | ||

| Alabama | 1 | 45 |

| Arkansas | 13 | 130 |

| Delaware | 2 | 2 |

| District of Columbia | — | 2 |

| Florida | 2 | 7 |

| Georgia | 3 | 39 |

| Kentucky | — | 20 |

| Louisiana | 4 | 21 |

| Maryland | 1 | 3 |

| Mississippi | — | 23 |

| North Carolina | <1 | 4 |

| Oklahoma | 19 | 117 |

| South Carolina | 1 | 9 |

| Tennessee | † | 6 |

| Texas | 7 | 17 |

| Virginia | 1 | 4 |

| West Virginia | <1 | — |

| Midwest | ||

| Illinois | 1 | 19 |

| Indiana | 3 | 28 |

| Iowa | 13 | 213 |

| Kansas | 15 | 65 |

| Michigan | 2 | 7 |

| Minnesota | 8 | 100 |

| Missouri | 7 | 84 |

| Nebraska | 8 | 117 |

| North Dakota | 3 | 44 |

| Ohio | 3 | 3 |

| South Dakota | 5 | 90 |

| Wisconsin | <1 | 5 |

| West | ||

| Alaska | 4 | 13 |

| Arizona | — | 36 |

| California | 66 | 212 |

| Colorado | 18 | 86 |

| Hawaii | 52 | 241 |

| Idaho | 20 | 72 |

| Montana | 30 | 133 |

| Nevada | 59 | 176 |

| New Mexico | 7 | 10 |

| Oregon | 98 | 251 |

| Utah | 16 | 186 |

| Washington | 18 | 143 |

| Wyoming | 15 | 209 |

| * Per 100,000 population aged 12 or older, with methamphetamine/amphetamine use as the primary diagnosis. Percentages in boldface exceed the national rate for that year. | ||

| † <0.05% | ||

| –No data available | ||

| Source: Reference 1 | ||

Scourge of the Heartland

A stimulant first synthesized in Japan,2 methamphetamine is the primary drug of abuse in Asia3 and the leading drug threat in the United States, according to U.S. law enforcement officials.4 Although most methamphetamine used in the United States is manufactured in “super-labs” along the U.S.-Mexican border,4 the drug is also easily made from common ingredients in small-scale home laboratories.

These smaller domestic “meth labs” have devastated rural communities and altered demographic patterns of methamphetamine abuse (Figure 1).5 Two aspects of rural life—relative isolation and availability of ingredients for production—proved critical in the initial spread of methamphetamine production and use in the United States. As a result, production by smaller labs is being targeted by state and federal law enforcement officers, who have had some success in eradicating this scourge (Box 1, Figure 2).6-9

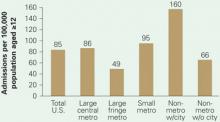

Figure 1 Substance abuse treatment admission rates

for methamphetamine-related diagnoses

Substance abuse treatment centers in rural areas had the highest admission rates for methamphetamine/amphetamine-related diagnoses in 2004. Admission rates in nonmetropolitan regions containing cities with populations >10,000 were triple those of suburbs, nearly twice those of big cities, and twice the U.S. average.

Figure 2 Methamphetamine clandestine laboratory incidents,* 2005

* Incidents include chemicals, contaminated glass, and equipment used in methamphetamine production found by law enforcement agencies at laboratories or dump sites.

Source: Drug Enforcement Administration database, reference 9Box 1

Dangerous recipes. The ease with which methamphetamine can be “cooked” in a home kitchen from ingredients available in pharmacies and hardware stores has contributed to the drug’s rapid spread. Meth users produce their own “fixes” using recipes readily available on the Internet and passed on by other “cooks.”6 The combination of inexperienced or intoxicated cooks, homemade equipment, and highly flammable ingredients results in frequent fires and explosions, often with injuries to home occupants and emergency responders.7

Meth labs have been estimated to produce 6 pounds of toxic waste for each 1 pound of methamphetamine produced. Composed of acid, lye, and phosphorus, this waste typically is dumped into ditches, rivers, yards, and drains. The fine-particulate methamphetamine residue generated during home production settles on exposed household surfaces, leading to absorption by children and others who come into contact with it.6,8

Disastrous results. Methamphetamine cooking has caused a social, environmental, and medical disaster—particularly in the Midwest (Figure 2), although the situation has improved in the past 2 years. Many states have passed laws restricting and monitoring sales of the methamphetamine ingredients ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. A change in U.S. law prohibiting pseudoephedrine imports in bulk from Canada has decreased domestic “superlab” production.9 Although these laws appear to have slowed U.S. manufacturing, the drug is still readily available, predominantly smuggled in from large-scale producers in Mexico.

Symptoms of ‘Meth’ Use

Physiologic effects. Methamphetamine is taken because it induces euphoria, anorexia, and increased energy, sexual stimulation, and alertness. Initial use evolves into abuse because of the drug’s highly addictive properties. Available in multiple forms and carrying a variety of labels (see Related resources), methamphetamine causes CNS release of monoamines—particularly dopamine—and damages dopaminergic neurons in the striatum and serotonergic neurons in the frontal lobes, striatum, and hippocampus.10,11

Through sympathetic nervous system activation, methamphetamine can cause reversible or irreversible damage to organ systems (Table 2).12-17

Table 2

Physiologic signs of methamphetamine abuse

| Vital signs | Tachycardia |

| Hypertension | |

| Pyrexia | |

| Laboratory abnormalities | Metabolic acidosis |

| Evidence of rhabdomyolysis | |

| Organ damage | Cardiomyopathy |

| Acute coronary syndrome | |

| Pulmonary edema | |

| Stigmata of chronic use | Premature aging |

| Cachexia | |

| Discolored and fractured teeth | |

| Skin lesions from stereotypical scratching related to formication (“meth bugs”) and/or compulsive picking | |

| Source: References 12-17 | |

Psychiatric effects. Methamphetamine abusers frequently report depressive symptoms, including irritability, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidal ideation.10,18 These patients may show:

- signs of psychosis, including paranoia, hallucinations, and homicidal thoughts

- neurocognitive changes, including poor attention, impaired verbal memory, and decreased executive functioning.19

Agitation is frequent, and its severity appears to correlate directly with methamphetamine blood levels.20 Violent behavior is common. In 1,016 previous users, 40% of men and 46% of women described difficulty controlling their behavior when under methamphetamine’s influence.18

In acute clinical practice, differentiating a primary thought disorder from methamphetamine-induced psychosis is challenging—especially when a patient shows signs of both.21 Methamphetamine also can contribute profoundly to depressive and anxiety disorders. Users may experience residual psychotic symptoms years after the original abuse ends, particularly when stressed. Their positive and negative symptoms are strikingly similar to those seen in schizophrenia.21

Longitudinal illness course, recent history, collateral information, and laboratory and physical data may all inform clinical presentations and comorbidity.

Emergent Evaluation

Gathering data. Police bring Mr. J, age 22, to the ED after his parents said he talked about killing himself and the mother of his 4-year-old child. Police report that Mr. J’s parents said he and his friends abuse methamphetamine, but no first-hand information is available.

Disheveled and uncooperative, Mr. J threatens to harm ED staff. His speech is pressured, and he appears to be responding to internal stimuli. Vital signs include temperature 37.8° C, pulse rate 105 bpm, blood pressure 140/85 mm Hg, and respiration rate 18 breaths per minute.

Mr. J refuses to provide blood or urine for drug screening or to provide a history to the ED physician. He attempts to walk out and is placed in restraints after he tries to punch the ED security officer.

Options for containing uncooperative and agitated patients such as Mr. J are extremely limited, and the overriding concern with violently intoxicated patients is to minimize damage to self, others, and property. Methamphetamine abusers have a propensity for impulsivity and violence;18 many are brought to the hospital by police and have criminal histories.1 In emergent evaluation, begin by searching patients and their belongings for weapons.

Because laboratory results and patient history are not immediately available, methamphetamine abuse often is not included in the initial differential diagnosis—particularly for patients with pre-existing primary affective or psychotic disorders. It is critical to remember that methamphetamine abuse might be complicating a patient’s psychiatric presentation.

Managing agitation. When agitation is prominent, secure the patient in a quiet room to reduce stimulation. Have on hand adequate staffing and benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, or both.

In theory, using an antipsychotic to control methamphetamine-induced agitation is problematic because synergy between the two agents might adversely affect cardiac function.15 On the other hand, acute treatment of agitation often leads to salutary declines in pulse rate, blood pressure, respiration rate, and body temperature.

Benzodiazepines vs neuroleptics. Evidence for acute treatment of agitation is limited,22 especially when agitation was induced by methamphetamine. A randomized, controlled comparison of lorazepam and droperidol (a neuroleptic not routinely prescribed for psychosis) suggested that droperidol could be used safely to control agitation in ED patients, with methamphetamine toxicity.23 Droperidol provided more rapid and effective sedation than lorazepam.

Droperidol use has decreased dramatically since 2001, however, when the FDA ordered a black-box warning about potential for cardiac dysrhythmias.24-25 After that warning, the American College of Emergency Physicians26 examined the evidence to identify the most effective pharmacologic treatment for agitation of unknown etiology. Its recommendation—felt to represent “moderate” clinical certainty—was monotherapy with either:

- a benzodiazepine (lorazepam or midazolam)

- or a conventional antipsychotic (droperidol or haloperidol).

The level of certainty for combining a benzodiazepine with an antipsychotic was lower. In our experience, psychiatrists tend to favor haloperidol and lorazepam over droperidol and midazolam.

Evidence on treating methamphetamine-induced agitation is limited (Box 2).22-26 Before you prescribe any medication, keep in mind its side effect profile, the patient’s age and physical condition, and the possibility that other substances might be contributing to emergent presentations.

We have repeatedly and effectively treated acutely agitated patients in the ED with haloperidol and lorazepam without observing adverse effects. Psychiatrists generally favor haloperidol and lorazepam over droperidol and midazolam. When a patient can cooperate with treatment, we recommend an ECG to rule out prolonged QTc interval, an uncommon complication. Telemetry and a cardiology consultation are indicated with a QTc interval >450 msec or >25% over previous ECGs, particularly if you plan to continue haloperidol treatment.27

Physical examination. Because methamphetamine use can cause substantial physical morbidity, we recommend a thorough physical exam aimed at identifying its stigmata (Table 2). Look especially for injuries resulting from violence, and test for sexually-transmitted diseases. Drug testing in the ED is essential to diagnosis and for planning treatment (Box 3).28,29

Medical-Surgical Consultation

Ensuring safety. Ms. A, age 41, is admitted to the trauma surgery service after a motor vehicle accident in which she was the driver. She has long-standing methamphetamine dependence and is severely agitated. Urine drug testing is positive for methamphetamine, marijuana, and alcohol. Her alcohol serum level of 165 mg/dL exceeds the legal threshold for intoxication.

Tibial and fibular fractures sustained in the car accident require open reduction and internal fixation. On the postsurgical floor 2 days later, Ms. A remains “extremely irritable, dysphoric, and suicidal,” according to the trauma surgery consultation. Staff is concerned about her boyfriend’s behavior: “We think he’s using drugs and might be bringing her drugs.”

Understanding Ms. A’s behavior requires us to consider a broad range of diagnostic contributors, including:

- untreated withdrawal from alcohol or other drugs

- delirium from ongoing effects of the trauma or corrective operation

- inadequate pain control, particularly given her history of substance dependence

- psychiatric comorbidity.

Management includes:

- monitoring for withdrawal and treating it if symptoms emerge

- identifying and minimizing medical factors contributing to confusion, and medicating agitation with psychotropics

- providing adequate analgesia, mindful that dosing may need to be aggressive—particularly if the abused substances include narcotics

- assessing for pre-existing and methamphetamine-induced psychiatric disorders.

If the patient is cognitively able to cooperate, perform a thorough suicide assessment and provide initial supportive and cognitive-behavioral therapy to target suicidal behavior. Consider one-to-one monitoring, depending on the potential for deliberate self-injury, and guard against impulsive actions occurring in a drug- or treatment-induced delirium that could endanger the patient or staff.

A one-to-one monitor also can watch for smuggled contraband. When hospitalized, patients who are chronic substance abusers are prone to continue using illicit substances smuggled in by associates, such as the boyfriend in this case. Consider further testing for illicit drugs if you suspect smuggling.

Acute Psychiatric Inpatient

Initial diagnosis and treatment planning. Miss G, age 23 and homeless, is admitted directly to the inpatient psychiatric unit from an urgent care clinic. She reports being “depressed and suicidal.” An intermittent methamphetamine abuser, she says she last used the drug the previous day.

Miss G reveals that she is on probation for forged checks and drug use. She believes she failed a random urinalysis given earlier in the day as a condition of her probation, and she fears being sent back to jail. Her history includes childhood sexual abuse and emotional abuse in a relationship that ended the previous year.

Take the long-term view. Emergency room physicians and psychiatrists often disagree about drug testing in the ED. Emergency medicine physicians argue that the yield is low and results do not affect short-term ED management. However, we believe that drug testing is essential during the initial evaluation and that, at a minimum, urine toxicology screening must be performed to aid diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning.

A positive toxicology screen provides nearly irrefutable evidence with which to confront a resistant patient who is likely to be involved with the criminal justice system. In a study by Perrone et al,28 the patient history combined with drug testing was most likely to identify substance abuse. Overreliance on either the history or testing alone was flawed.

Objective data. In our experience, patients with legal problems often deny drug abuse. A toxicology screen provides objective data on concomitant use of other substances abused by many methamphetamine users to temper methamphetamine-related insomnia, anxiety, and overstimulation. Hair testing, a promising tool being investigated, may allow more substance abuse to be detected and possibly determine the level of use.29

Physical examination shows multiple erythematous excoriations on her arms from repetitive picking at her skin, poor dentition, and cachexia. She reports multiple recent sexual partners without using condoms. She cannot remember when she last menstruated, and she doesn’t recall ever being tested for sexually transmitted disease.

As in any medical setting involving methamphetamine abusers, acute management of psychiatric inpatients includes careful attention to methamphetamine-related physical conditions—in Miss G’s case possible sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy, cellulitis, and dental disease.

Mood and anxiety disorders. Methamphetamine users may present with depressive symptoms and suicidality.18,30 In a study of Taiwanese methamphetamine abusers who had recently quit the drug, depressive symptoms were common on cessation but often resolved without antidepressants within 2 to 3 weeks.30 Evidence on antidepressant use in the methamphetamine-dependent patient is limited, and the existing studies have yielded conflicting results (as we will detail in part 2 of this article).

For patients previously diagnosed with mood or anxiety disorders, do not restart psychotropics until you have considered how methamphetamine use is contributing to the immediate presentation. We recommend initial observation for several weeks before starting an antidepressant if there is no pre-methamphetamine history of mood or anxiety symptoms.

Psychosocial treatments. Involve social services in assessing the patient’s need for community resources. Miss G’s ability to benefit from these programs will depend on her cognitive capacity, education level, trauma history, and comorbid psychiatric illness.

For patients who relapse to methamphetamine use, previous successful treatment and abstinence may be a hopeful prognostic sign and warrant referral to a program for recidivists. The patient’s legal status may limit some options in the community but open others in the criminal justice system.

Methamphetamine users often have multiple problems that require attention. For example, compared with other mothers under investigation by child welfare services in California, methamphetamine-abusing mothers were younger and less educated on average, less likely to have had substance-abuse treatment, and more likely to have criminal records.31 These findings underscore the challenge of coordinating a response that integrates separate and complex systems—psychiatric/substance abuse treatment, child welfare, and criminal justice.

- Methresources. Web site pooling information from multiple agencies for communities, law enforcement, and policy makers. www.methresources.gov.

- Methamphetamine. National drug threat assessment, with information on methamphetamine production, trafficking, and patterns of use. U.S. Department of Justice. Drug Enforcement Administration. www.dea.gov/concern/18862/meth.htm.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug and Alcohol Services Information System. Trends in methamphetamine/amphetamine admissions to treatment: 1993-2003. The DASIS Report 2006; Issue 9. www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k6/methTX/methTX.pdf.

Drug brand names

- Droperidol • Inapsine

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Midazolam • Versed

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Drug and Alcohol Services Information System. Trends in methamphetamine/amphetamine admissions to treatment: 1993-2003. The DASIS Report 2006; Issue 9. Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k6/methTX/methTX.htm. Accessed September 4, 2006.

2. Suwaki H, Fukui S, Konuma K. Methamphetamine abuse in Japan: its 45 year history and the current situation. In: Klee H, ed. Amphetamine misuse: international perspectives on current trends Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997:199-214.

3. Greenfeld KT. The need for speed. Time (Asia ed) February 26, 2001. Available at: http://www.time.com/time/asia/news/magazine/0,9754,100581,00.html. Accessed September 4, 2006.

4. Williams P. Meth trade moves south of the border. Tighter restrictions reduce U.S. meth labs, so Mexican drug lords fill gap. NBC News August 25, 2006. Available at: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/14500890/. Accessed September 4, 2006.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Drug and Alcohol Services Information System. Methamphetamine/amphetamine treatment admissions in urban and rural areas: 2004. The DASIS Report 2006; Issue 27. Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k6/methRuralTX/methRuralTX.htm. Accessed September 4, 2006.

6. Research Overview: Methamphetamine Production Precursor Chemicals and Child Endangerment Albuquerque, NM: New Mexico Sentencing Commission; January 2004. Available at: http://www.nmsc.state.nm.us/DWIDrugReports.htm. Accessed October 1, 2006.

7. Santos AP, Wilson AK, Hornung CA, et al. Methamphetamine laboratory explosions: a new and emerging burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 2005;26(3):228-32.

8. Martyny JW, Arbuckle SL, McCammon CS, et al. Chemical exposures associated with clandestine methamphetamine laboratories Denver, CO: The National Jewish Medical and Research Center. Available at: http://www.njc.org/pdf/chemical_exposures.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2006.

9. U.S. Department of Justice. Drug Enforcement Administration. Maps of methamphetamine lab incidents. Available at: http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/concern/map_lab_seizures.html. Accessed September 4, 2006.

10. Anglin MD, Burke C, Perrochet B, et al. History of the methamphetamine problem. J Psychoactive Drugs 2000;32(2):137-41.

11. National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse. Methamphetamine abuse and addiction. NIH Publication No 02-4210. Research Report Series January 2002. Available at: http://www.nida.nih.gov/ResearchReports/Methamph/Methamph.html. Accessed October 1, 2006.

12. Burchell SA, Ho HC, Yu M, Margulies DR. Effects of methamphetamine on trauma patients: a cause of severe metabolic acidosis? Crit Care Med 2000;28(6):2112-5.

13. Richards JR, Johnson EB, Stark RW, Derlet RW. Methamphetamine abuse and rhabdomyolysis in the ED: a 5-year study. Am J Emerg Med 1999;17(7):681-5.

14. Wijetunga M, Seto T, Lindsay J, Schatz I. Crystal methamphetamine-associated cardiomyopathy: tip of the iceberg? J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2003;41(7):981-6.

15. Turnipseed SD, Richards JR, Kirk JD, et al. Frequency of acute coronary syndrome in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain after methamphetamine use. J Emerg Med 2003;24(4):369-73.

16. Nestor TA, Tamamoto WI, Kam TH, Schultz T. Acute pulmonary oedema caused by crystalline methamphetamine. Lancet 1989;2(8674):1277-8.

17. Venker D. Crystal methamphetamine and the dental patient. Iowa Dent J 1999;85(4):34.-

18. Zweben JE, Cohen JB, Christian D, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in methamphetamine users. Am J Addict 2004;13(2):181-90.

19. Nordahl TE, Salo R, Leamon M. Neuropsychological effects of chronic methamphetamine use on neurotransmitters and cognition: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;15(3):317-25.

20. Batki SL, Harris DS. Quantitative drug levels in stimulant psychosis: relationship to symptom severity, catecholamines and hyperkinesia. Am J Addict 2004;13(5):461-70.

21. Yui K, Ikemoto S, Ishiguro T, Goto K. Studies of amphetamine or methamphetamine psychosis in Japan: relation of methamphetamine psychosis to schizophrenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;914:1-12.

22. Marder SR. A review of agitation in mental illness: treatment guidelines and current therapies. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(suppl10):13-21.

23. Richards JR, Derlet RW, Duncan DR. Chemical restraint for the agitated patient in the emergency department: lorazepam versus droperidol. J Emerg Med 1998;16(4):567-73.

24. Shale JH, Shale CM, Mastin WD. Safety of droperidol in behavioural emergencies. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2004;3(4):369-78.

25. Jacoby JL, Fulton J, Cesta M, Heller M. After the black box warning: dramatic changes in ED use of droperidol. Am J Emerg Med 2005;23(2):196.-Letter.

26. Lukens TW, Wolf SJ, Edlow JA, et al. American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Critical Issues in the Diagnosis and Management of the Adult Psychiatric Patient in the Emergency Department Clinical policy: critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2006;47(1):79-99.

27. American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, compendium 2004 Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 29-66.

28. Perrone J, De Roos F, Jayaraman S, Hollander JE. Drug screening versus history in detection of substance use in ED psychiatric patients. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19(1):49-51.

29. Mieczkowski T. Hair analysis for detection of psychotropic drug use [letter]. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81(4):568-9.

30. McGregor C, Srisurapanont M, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. The nature, time course and severity of methamphetamine withdrawal. Addiction 2005;100(9):1320-9.

31. Grella CE, Hser YI, Huang YC. Mothers in substance abuse treatment: differences in characteristics based on involvement with child welfare services. Child Abuse Negl 2006;30(1):55-73.

Methamphetamine abuse has spread to every region of the United States in the past 10 years (Table 1).1 Its long-lasting, difficult-to-treat medical effects destroy lives and create psychiatric and physical comorbidities that confound clinicians in emergency rooms and community practice settings.

This first in a series of two articles describes methamphetamine’s growing use and offers guidance to identify abusers and manage acute “meth” intoxication. Methamphetamine-abusing patients can appear in any area of acute psychiatric practice—during emergency department (ED) evaluations, medical-surgical consultations, and inpatient psychiatric admissions. Using case examples, we describe key clinical principles to help you assess patients in each of these settings.

Table 1

10-year growth in hospitalization rates

for methamphetamine/amphetamine use*

| Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | 1993 | 2003 |

| U.S. national rate | 13 | 56 |

| Northeast | ||

| Connecticut | 1 | 4 |

| Maine | 2 | 5 |

| Massachusetts | <1 | 2 |

| New Hampshire | <1 | 2 |

| New Jersey | 3 | 2 |

| New York | 2 | 4 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 2 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | 2 |

| Vermont | 5 | 4 |