User login

‘Meth’ recovery: 3 steps to successful chronic management

Clinicians could become discouraged when confronting methamphetamine-dependent patients’ wide-ranging psychiatric symptoms.

These patients often present with:

- overlapping primary psychiatric syndromes and secondary substance abuse

- complex histories fraught with psychological trauma, limited social supports, and court involvement.

Treatment can be successful, however, and patients can change their addictive behaviors with a chronic disease management approach that targets the drug’s cognitive sequelae and psychiatric effects. Medications show limited benefit (Box 1),1-8 but behavioral treatments—including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational incentives—have proven efficacy in treating methamphetamine addiction.

This article discusses how to counteract methamphetamine’s negative cognitive effects and enable patients to engage in psychosocial treatment. Our discussion is informed by an extensive literature search and clinical experience from treating patients in the Midwest—at the geographic heart of the “meth” epidemic.

CASE REPORT: Overwhelmed and suicidal

Ms. D, age 27, presents to the emergency department with anxiety, dysphoria, and a plan to commit suicide by overdose. She feels overwhelmed by her 4-hour-a-day customer service job—a prerequisite for staying at the halfway house where she has lived for 2 months. She has a 13-year history of polysubstance dependence and is under court order to complete chemical dependence treatment or go to jail.

No medications are FDA-approved for treating methamphetamine dependence, and evidence supporting medication use in methamphetamine dependence is extremely limited. Research efforts are aimed at finding medications that might be neuroprotective, decrease craving, block reinforcement mechanisms, or affect other factors behind methamphetamine addiction and relapse.1 Most trials have been conducted in animal models or controlled laboratory evaluations of drug effects on methamphetamine-induced states.

Bupropion has shown slight treatment efficacy, possibly by decreasing neuronal damage and blocking reinforcement.2-4 Modafinil5 and baclofen6 may have potential, but evidence is lacking.

Some results have been unexpectedly negative. Sertraline might be contraindicated in methamphetamine dependence treatment, according to results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial7 of sertraline and contingency management (Table 1). In a human laboratory study,8 topiramate accentuated—rather than diminished—subjective response to methamphetamine (Table 2).

Ms. D began using drugs at age 14 and has 3 convictions for driving under the influence of alcohol. An average student, she dropped out of high school but obtained a GED certificate. She first had psychiatric contact at age 16 and has been diagnosed at various times with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorder. She also has been violently sexually assaulted while engaging in prostitution to support her drug habit.

Ms. D has been hospitalized multiple times—voluntarily and involuntarily—in dual diagnosis treatment centers. Her 5-year-old son no longer lives with her, and she has limited social supports beyond her parents, who live in a neighboring state.

Table 1

Antidepressant trials for treating methamphetamine dependence

| Drug | Investigation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bupropion2-4 | Laboratory | Safety of bupropion with MAP |

| Laboratory | Reduced subjective effects and cue-induced craving | |

| Clinical trial | Trend toward reduced MAP use compared with placebo | |

| Sertraline7 | Clinical trial | Sertraline-treated subjects showed higher use of MAP compared with those receiving placebo and were less likely to complete treatment |

| MAP: methamphetamine | ||

3-step approach

For patients such as Ms. D, clinical evidence supports a 3-step approach to treating methamphetamine dependence:

- step 1: institute acute management and stabilization

- step 2: eliminate or decrease methamphetamine use to “move the frontal lobe back to the front”

- step 3: identify and target psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidities.

- help her eliminate or decrease methamphetamine use to allow neuronal systems to recover

- target maladaptive behaviors that hinder sobriety while providing motivational incentives to help her maintain a methamphetamine-free life.

How ‘meth’ affects cognition

Methamphetamine use has been associated with cognitive dysfunction at initial abstinence and even years later in some patients.10 Ms. D’s cognitive limitations in a fast-paced customer service job—even though hours are limited—lead to anxiety, dysphoria, and loss of self-esteem when she can’t manage patrons’ requests.

Methamphetamine has profound acute and chronic effects on the sympathetic nervous system, and dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic neuronal networks. Most evidence of chronic neuronal effects comes from animal research and reflects toxic damage to dopaminergic and serotonergic neuronal systems. Postmortem human studies of direct neurotoxicity from chronic methamphetamine exposure show:

- decreased dopamine and tyrosine hydroxylase levels

- reduced concentrations of dopamine transporters.11

In chronic methamphetamine abusers, functional magnetic resonance imaging, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and positron emission tomography show:

- changes in neurotransmitter, protein, brain metabolism, and transporter levels

- damage in multiple brain areas including the frontal region, basal ganglia, grey matter, corpus callosum, and striatum; smaller hippocampi; and cerebral vasculature changes.14-16

CASE CONTINUED: Does she understand?

After Ms. D is stabilized, her case manager expresses concern about her ability to follow through with treatment planning. He says, “I just don’t think she understands some of the things we discuss.” She then is referred for neuropsychological testing, which shows clear cognitive impairment. Specifically, she has a slowed rate of thinking, general cognitive ineficiency, deficits in learning and memory retention, and mild impulsivity.

Patients with a history of extensive methamphetamine abuse are ruled by the limbic system and may have higher cortical damage that complicates initiating, maintaining, and fully participating in treatment. Patients’ deficits in memory, executive functioning, attention, and cognitive speed may require you to simplify, repeat, and otherwise modify your treatment plan. You will need to provide clear instructions and consistent support—individually and psychosocially—and to recognize and reinforce patients’ treatment gains.

Even before using methamphetamine, patients may have had academic problems or learning disabilities that will compromise their ability to participate in treatment. Infection with HIV, syphilis, or hepatitis C can further hamper cognitive function.18

What treatments are effective?

Medications. Evidence is extremely limited, and no medications are approved to treat methamphetamine-addicted patients. Bupropion has shown some efficacy (Table 1),2-4,7 but other drugs such as sertraline and topiramate may aggravate rather than diminish methamphetamine dependence (Table 2).5,6,8,19

Behavioral treatments supply the evidence basis for methamphetamine dependence treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),20 contingency management (CM),21,22 and a manualized structured treatment—the Matrix Model23—all have proven efficacy.

CBT involves functional analysis and skills training. Patients are guided through analyzing their drug use and associated cognitions, emotions, and expectations and in identifying situations that trigger methamphetamine use or relapse. Skills training involves identifying, reinforcing, and practicing coping skills to help the patient avoid drug use and reinforce the ability to refuse use.

CM is based on operant conditioning—the use of consequences to modify behavior. It involves establishing a “contingent” relationship between a desired behavior/outcome (such as methamphetamine-free urinalysis) and delivering a positive reinforcing event to promote abstinence:

- Vouchers, privileges, or small amounts of money linked to healthy behaviors serve as incentives for negative urine testing.

- Rewards increase as periods of confirmed abstinence lengthen and are reset to smaller rewards if relapse occurs.

CM does not require extensive staff training and has been described as relatively simple to implement. CM also has been used successfully in urban gay and bisexual men with methamphetamine dependence (Box 2).18,25-29

Although CM’s efficacy is well-supported by clinical trials, we have encountered some resistance to the idea of “paying individuals to not use drugs” when training medical students, allied health staff, and residents. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) supports the use of motivational incentives in treating substance abuse and offers support materials, resources, and training on this approach (see Related Resources).

Multiple studies show that CBT and CM are equally effective for treating chronic methamphetamine abuse at a 1-year follow-up, although CM may be more effective than CBT for acute treatment.

The Matrix model is a 4-month intensive, manualized treatment program that uses CBT, education on drug effects, positive reinforcement for intended behavioral change, and a 12-step approach.

Methamphetamine dependence outcomes based on the Matrix treatment model were compared with community treatment as usual in a project sponsored by The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.30 End-point outcomes were similar, but the Matrix treatment was more effective in early treatment, including decreased urinalyses positive for methamphetamine and increased abstinence.

Methamphetamine use is estimated to be 5 to 10 times more prevalent in U.S. urban gay and bisexual groups than in the general population25 and likely is contributing to rising human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection rates in men having sex with men (MSM).

Used to enhance sexual performance, libido, and mood, methamphetamine is associated with increased rates of unprotected anal sex and multiple partners in MSM.26 An HIV infection rate of 61% was reported in methamphetamine-dependent MSM seeking treatment in a Los Angeles clinical trial.27 Methamphetamine also results in high-risk sexual practices and multiple partners among heterosexual men and women.28

Although seroconverted men report using methamphetamine to alleviate HIV-associated depression, the combination of HIV infection and methamphetamine use may have powerful negative effects. Methamphetamine use is associated with HIV treatment nonadherence and also may suppress immune function.29 Cognitive impairments associated with HIV and methamphetamine use are additive and are further exacerbated by hepatitis C infection.18

Recommendation. Screen for methamphetamine use in MSM populations, and educate these patients about risks associated with methamphetamine use. In all patient groups who report using methamphetamine, provide counseling on high-risk sexual behavior, screen for sexually transmitted diseases, and ensure that patients are vaccinated against hepatitis A and B infection (see Related Resources). Most important, refer for medical treatment when indicated.

In patients such as Ms. D, the structure of court-ordered treatment can provide accountability, enforced abstinence, and mandated treatment resources. This, in turn, may give your patient a better chance to engage a recovering and better functioning frontal lobe to inhibit urges for methamphetamine use and manage stress.

Table 2

Other agents studied in methamphetamine dependence trials

| Drug | Investigation | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Baclofen6 (GABAergic) | Clinical trial | No statistically significant effect compared with placebo; post hoc analysis showed ‘small’ treatment effects vs placebo |

| Gabapentin6 (GABAergic) | Clinical trial | No statistically signicant effect compared with placebo; post hoc analysis showed no treatment effects vs placebo |

| Topiramate8 (anticonvulsant) | Laboratory | Accentuated (rather than diminished) subjective effects of MAP |

| Aripiprazole19 (SGA) | Laboratory | Decreased subjective effects of amphetamine |

| Modafinil5 (wakefulness agent) | Clinical trial | Successful trial in cocaine dependence; potential option for MAP |

| MAP: methamphetamine; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic | ||

CASE CONTINUED: Racing thoughts and psychosis

Before hospital admission, Ms. D was being treated with gabapentin, 300 mg bid, and sustained-release bupropion, 150 mg/d, for anxiety and dysphoria. Previously, she has received multiple antidepressants and mood stabilizers with reportedly little effect.

Initially guarded, she at first denies psychotic symptoms but acknowledges their extent several days later. She describes periods of 6 months or more when she feels “lost.” The treatment team titrates quetiapine up to 200 mg/d and restarts duloxetine, 30 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, based on her past positive response to this antidepressant.

Methamphetamine abuse can cause and exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. Keep in mind 2 priorities as you approach these symptoms:

Aim for abstinence. Methamphetamine abuse produces a remarkable array of adverse effects. It causes dysphoria, anxiety, and psychosis during active use and in the interval after initial abstinence. Many of methamphetamine’s use and withdrawal symptoms resolve with time, however, and may not require pharmacologic treatment.31 Therefore, achieving abstinence and keeping patients in treatment is high priority.

Use behavioral approaches whenever feasible. Balance the need to use benzodiazepines for ongoing treatment of severe anxiety or agitation with the high risk of addiction or diversion in this group. Anxiety may resolve over time in association with sustained abstinence. Similarly, receiving treatment for methamphetamine dependence and maintaining abstinence appears to ease depressive symptoms, as shown by sustained improvements in Beck Depression Inventory scores at 1 year.32

Manage stress. Stress can worsen psychiatric symptoms, trigger methamphetamine abuse relapse and psychosis, and acutely and chronically augment methamphetamine’s toxic effects.33 You can help patients manage stress by:

- providing case management and CBT training

- advising them about proper sleep, nutrition, and medical care.

Targeting psychiatric symptoms

Step 3 in the chronic disease management approach to methamphetamine dependence is to identify and target psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidities. When approaching psychiatric symptoms, high priorities are to aim for abstinence and manage the patient’s stress (Box 3).31-33

In clinical practice, we find it difficult to diagnostically categorize and treat methamphetamine-abusing patients who show residual post-acute psychotic symptoms. Some appear to have no risk factors for primary psychotic illness, and their symptoms show an association with the severity of their past methamphetamine abuse.

Other patient presentations can be difficult to separate from family histories of psychotic illness. Research suggests that genetic risk factors may be associated with methamphetamine psychosis in some vulnerable patients.35

Unfortunately, no data exist to guide the use of antipsychotics to maintain symptom control. Some patients may need low-dose antipsychotics for maintenance treatment, and second-generation antipsychotics may have a theoretical advantage over first-generation antipsychotics. Use your clinical judgment in determining dosing and treatment duration, and in weighing risks and benefits of continued treatment.

Using imaging, researchers found aggression severity to be directly correlated with past total methamphetamine use and globally decreased serotonin transporter density.36 Serotonin transporter densities were 30% lower in methamphetamine users vs controls after >1 year of abstinence.

CASE CONTINUED: Discharge plans

Because of the severity of her psychiatric symptoms, Ms. D is unable to return to the halfway house after discharge. As her treatment team works to coordinate discharge placement, Ms. D continues to improve. Her psychotic and dysphoria symptoms resolve, and she shows increased spontaneity. These changes—attributed to supports during hospitalization, decreased stressors, and quetiapine treatment—continue until her discharge to a combined mental illness and chemical dependence program.

- Methamphetamine use and sexually transmitted diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/std/DearColleagueRiskBehaviorMetUse8-18-2006.pdf.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse Blending Initiative. Promoting Awareness of Motivational Incentives (PAMI). www.drugabuse.gov/blending/PAMI.html.

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Baclofen • various

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Trazodone • Desyrel

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Vocci FJ, Acri J, Elkashef A. Medication development for addictive disorders: the state of the science. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1432-4.

2. Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, 2nd, et al. Safety of intravenous methamphetamine administration during treatment with bupropion. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;182:426-35.

3. Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, et al. Bupropion reduces methamphetamine-induced subjective effects and cue-induced craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31:1537-44.

4. Ling W, Rawson R, Shoptaw S. Management of methamphetamine abuse and dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2006;8:345-54.

5. Umanoff DF. Trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005;30:2298; author reply 2299-300.

6. Heinzerling KG, Shoptaw S, Peck JA, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of baclofen and gabapentin for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;85:177-84.

7. Shoptaw S, Huber A, Peck J, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline and contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;85:12-8.

8. Johnson BA, Roache JD, Ait-Daoud N, et al. Effects of acute topiramate dosing on methamphetamine-induced subjective mood. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;10:85-98.

9. Bostwick J, Lineberry T. The ‘meth’ epidemic: Managing acute psychosis, agitation, and suicide risk. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):46-62.

10. Simon SL, Dacey J, Glynn S, et al. The effect of relapse on cognition in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat 2004;27:59-66.

11. Wilson JM, Kalasinsky KS, Levey AI, et al. Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic methamphetamine users. Nat Med 1996;2:699-703.

12. Moszczynska A, Fitzmaurice P, Ang L, et al. Why is parkinsonism not a feature of human methamphetamine users? Brain 2004;127:363-70.

13. Armstrong BD, Noguchi KK. The neurotoxic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and methamphetamine on serotonin, dopamine, and GABAergic terminals: an in-vitro autoradiographic study in rats. Neurotoxicology 2004;25:905-14.

14. London ED, Berman SM, Voytek B, et al. Cerebral metabolic dysfunction and impaired vigilance in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:770-8.

15. London ED, Simon SL, Berman SM, et al. Mood disturbances and regional cerebral metabolic abnormalities in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:73-84.

16. Nordahl TE, Salo R, Leamon M. Neuropsychological effects of chronic methamphetamine use on neurotransmitters and cognition: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;15:317-25.

17. Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Chang L, et al. Partial recovery of brain metabolism in methamphetamine abusers after protracted abstinence. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:242-8.

18. Cherner M, Letendre S, Heaton RK, et al. Hepatitis C augments cognitive deficits associated with HIV infection and methamphetamine. Neurology 2005;64:1343-7.

19. Stoops WW. Aripiprazole as a potential pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: human laboratory studies with damphetamine. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;14:413-21.

20. Yen CF, Wu HY, Yen JY, Ko CH. Effects of brief cognitive-behavioral interventions on confidence to resist the urges to use heroin and methamphetamine in relapse-related situations. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192:788-91.

21. Roll JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, et al. Contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1993-9.

22. Shoptaw S, Klausner JD, Reback CJ, et al. A public health response to the methamphetamine epidemic: the implementation of contingency management to treat methamphetamine dependence. BMC Public Health 2006;6:214.-

23. Shoptaw S, Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Obert JL. The Matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: evidence of efficacy. J Addict Dis 1994;13:129-41.

24. Sindelar J, Elbel B, Petry NM. What do we get for our money? Cost-effectiveness of adding contingency management. Addiction 2007;102:309-16.

25. Shoptaw S. Methamphetamine use in urban gay and bisexual populations. Top HIV Med 2006;14:84-7.

26. Bolding G, Hart G, Sherr L, Elford J. Use of crystal methamphetamine among gay men in London. Addiction 2006;101:1622-30.

27. Peck JA, Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, et al. HIV-associated medical, behavioral, and psychiatric characteristics of treatment-seeking, methamphetamine-dependent men who have sex with men. J Addict Dis 2005;24:115-32.

28. Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. The context of sexual risk behavior among heterosexual methamphetamine users. Addict Behav 2004;29:807-10.

29. Mahajan SD, Hu Z, Reynolds JL, et al. Methamphetamine modulates gene expression patterns in monocyte derived mature dendritic cells: implications for HIV-1 pathogenesis. Mol Diagn Ther 2006;10:257-69.

30. Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, et al. A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction 2004;99:708-17.

31. McGregor C, Srisurapanont M, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. The nature, time course and severity of methamphetamine withdrawal. Addiction 2005;100:1320-9.

32. Peck JA, Reback CJ, Yang X, et al. Sustained reductions in drug use and depression symptoms from treatment for drug abuse in methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men. J Urban Health 2005;82:i100-8.

33. Matuszewich L, Yamamoto BK. Chronic stress augments the long-term and acute effects of methamphetamine. Neuroscience 2004;124:637-46.

34. Batki SL, Harris DS. Quantitative drug levels in stimulant psychosis: relationship to symptom severity, catecholamines and hyperkinesia. Am J Addict 2004;13:461-70.

35. Suzuki A, Nakamura K, Sekine Y, et al. An association study between catechol-O-methyl transferase gene polymorphism and methamphetamine psychotic disorder. Psychiatr Genet 2006;16:133-8.

36. Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Takei N, et al. Brain serotonin transporter density and aggression in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:90-100.

Clinicians could become discouraged when confronting methamphetamine-dependent patients’ wide-ranging psychiatric symptoms.

These patients often present with:

- overlapping primary psychiatric syndromes and secondary substance abuse

- complex histories fraught with psychological trauma, limited social supports, and court involvement.

Treatment can be successful, however, and patients can change their addictive behaviors with a chronic disease management approach that targets the drug’s cognitive sequelae and psychiatric effects. Medications show limited benefit (Box 1),1-8 but behavioral treatments—including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational incentives—have proven efficacy in treating methamphetamine addiction.

This article discusses how to counteract methamphetamine’s negative cognitive effects and enable patients to engage in psychosocial treatment. Our discussion is informed by an extensive literature search and clinical experience from treating patients in the Midwest—at the geographic heart of the “meth” epidemic.

CASE REPORT: Overwhelmed and suicidal

Ms. D, age 27, presents to the emergency department with anxiety, dysphoria, and a plan to commit suicide by overdose. She feels overwhelmed by her 4-hour-a-day customer service job—a prerequisite for staying at the halfway house where she has lived for 2 months. She has a 13-year history of polysubstance dependence and is under court order to complete chemical dependence treatment or go to jail.

No medications are FDA-approved for treating methamphetamine dependence, and evidence supporting medication use in methamphetamine dependence is extremely limited. Research efforts are aimed at finding medications that might be neuroprotective, decrease craving, block reinforcement mechanisms, or affect other factors behind methamphetamine addiction and relapse.1 Most trials have been conducted in animal models or controlled laboratory evaluations of drug effects on methamphetamine-induced states.

Bupropion has shown slight treatment efficacy, possibly by decreasing neuronal damage and blocking reinforcement.2-4 Modafinil5 and baclofen6 may have potential, but evidence is lacking.

Some results have been unexpectedly negative. Sertraline might be contraindicated in methamphetamine dependence treatment, according to results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial7 of sertraline and contingency management (Table 1). In a human laboratory study,8 topiramate accentuated—rather than diminished—subjective response to methamphetamine (Table 2).

Ms. D began using drugs at age 14 and has 3 convictions for driving under the influence of alcohol. An average student, she dropped out of high school but obtained a GED certificate. She first had psychiatric contact at age 16 and has been diagnosed at various times with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorder. She also has been violently sexually assaulted while engaging in prostitution to support her drug habit.

Ms. D has been hospitalized multiple times—voluntarily and involuntarily—in dual diagnosis treatment centers. Her 5-year-old son no longer lives with her, and she has limited social supports beyond her parents, who live in a neighboring state.

Table 1

Antidepressant trials for treating methamphetamine dependence

| Drug | Investigation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bupropion2-4 | Laboratory | Safety of bupropion with MAP |

| Laboratory | Reduced subjective effects and cue-induced craving | |

| Clinical trial | Trend toward reduced MAP use compared with placebo | |

| Sertraline7 | Clinical trial | Sertraline-treated subjects showed higher use of MAP compared with those receiving placebo and were less likely to complete treatment |

| MAP: methamphetamine | ||

3-step approach

For patients such as Ms. D, clinical evidence supports a 3-step approach to treating methamphetamine dependence:

- step 1: institute acute management and stabilization

- step 2: eliminate or decrease methamphetamine use to “move the frontal lobe back to the front”

- step 3: identify and target psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidities.

- help her eliminate or decrease methamphetamine use to allow neuronal systems to recover

- target maladaptive behaviors that hinder sobriety while providing motivational incentives to help her maintain a methamphetamine-free life.

How ‘meth’ affects cognition

Methamphetamine use has been associated with cognitive dysfunction at initial abstinence and even years later in some patients.10 Ms. D’s cognitive limitations in a fast-paced customer service job—even though hours are limited—lead to anxiety, dysphoria, and loss of self-esteem when she can’t manage patrons’ requests.

Methamphetamine has profound acute and chronic effects on the sympathetic nervous system, and dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic neuronal networks. Most evidence of chronic neuronal effects comes from animal research and reflects toxic damage to dopaminergic and serotonergic neuronal systems. Postmortem human studies of direct neurotoxicity from chronic methamphetamine exposure show:

- decreased dopamine and tyrosine hydroxylase levels

- reduced concentrations of dopamine transporters.11

In chronic methamphetamine abusers, functional magnetic resonance imaging, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and positron emission tomography show:

- changes in neurotransmitter, protein, brain metabolism, and transporter levels

- damage in multiple brain areas including the frontal region, basal ganglia, grey matter, corpus callosum, and striatum; smaller hippocampi; and cerebral vasculature changes.14-16

CASE CONTINUED: Does she understand?

After Ms. D is stabilized, her case manager expresses concern about her ability to follow through with treatment planning. He says, “I just don’t think she understands some of the things we discuss.” She then is referred for neuropsychological testing, which shows clear cognitive impairment. Specifically, she has a slowed rate of thinking, general cognitive ineficiency, deficits in learning and memory retention, and mild impulsivity.

Patients with a history of extensive methamphetamine abuse are ruled by the limbic system and may have higher cortical damage that complicates initiating, maintaining, and fully participating in treatment. Patients’ deficits in memory, executive functioning, attention, and cognitive speed may require you to simplify, repeat, and otherwise modify your treatment plan. You will need to provide clear instructions and consistent support—individually and psychosocially—and to recognize and reinforce patients’ treatment gains.

Even before using methamphetamine, patients may have had academic problems or learning disabilities that will compromise their ability to participate in treatment. Infection with HIV, syphilis, or hepatitis C can further hamper cognitive function.18

What treatments are effective?

Medications. Evidence is extremely limited, and no medications are approved to treat methamphetamine-addicted patients. Bupropion has shown some efficacy (Table 1),2-4,7 but other drugs such as sertraline and topiramate may aggravate rather than diminish methamphetamine dependence (Table 2).5,6,8,19

Behavioral treatments supply the evidence basis for methamphetamine dependence treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),20 contingency management (CM),21,22 and a manualized structured treatment—the Matrix Model23—all have proven efficacy.

CBT involves functional analysis and skills training. Patients are guided through analyzing their drug use and associated cognitions, emotions, and expectations and in identifying situations that trigger methamphetamine use or relapse. Skills training involves identifying, reinforcing, and practicing coping skills to help the patient avoid drug use and reinforce the ability to refuse use.

CM is based on operant conditioning—the use of consequences to modify behavior. It involves establishing a “contingent” relationship between a desired behavior/outcome (such as methamphetamine-free urinalysis) and delivering a positive reinforcing event to promote abstinence:

- Vouchers, privileges, or small amounts of money linked to healthy behaviors serve as incentives for negative urine testing.

- Rewards increase as periods of confirmed abstinence lengthen and are reset to smaller rewards if relapse occurs.

CM does not require extensive staff training and has been described as relatively simple to implement. CM also has been used successfully in urban gay and bisexual men with methamphetamine dependence (Box 2).18,25-29

Although CM’s efficacy is well-supported by clinical trials, we have encountered some resistance to the idea of “paying individuals to not use drugs” when training medical students, allied health staff, and residents. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) supports the use of motivational incentives in treating substance abuse and offers support materials, resources, and training on this approach (see Related Resources).

Multiple studies show that CBT and CM are equally effective for treating chronic methamphetamine abuse at a 1-year follow-up, although CM may be more effective than CBT for acute treatment.

The Matrix model is a 4-month intensive, manualized treatment program that uses CBT, education on drug effects, positive reinforcement for intended behavioral change, and a 12-step approach.

Methamphetamine dependence outcomes based on the Matrix treatment model were compared with community treatment as usual in a project sponsored by The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.30 End-point outcomes were similar, but the Matrix treatment was more effective in early treatment, including decreased urinalyses positive for methamphetamine and increased abstinence.

Methamphetamine use is estimated to be 5 to 10 times more prevalent in U.S. urban gay and bisexual groups than in the general population25 and likely is contributing to rising human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection rates in men having sex with men (MSM).

Used to enhance sexual performance, libido, and mood, methamphetamine is associated with increased rates of unprotected anal sex and multiple partners in MSM.26 An HIV infection rate of 61% was reported in methamphetamine-dependent MSM seeking treatment in a Los Angeles clinical trial.27 Methamphetamine also results in high-risk sexual practices and multiple partners among heterosexual men and women.28

Although seroconverted men report using methamphetamine to alleviate HIV-associated depression, the combination of HIV infection and methamphetamine use may have powerful negative effects. Methamphetamine use is associated with HIV treatment nonadherence and also may suppress immune function.29 Cognitive impairments associated with HIV and methamphetamine use are additive and are further exacerbated by hepatitis C infection.18

Recommendation. Screen for methamphetamine use in MSM populations, and educate these patients about risks associated with methamphetamine use. In all patient groups who report using methamphetamine, provide counseling on high-risk sexual behavior, screen for sexually transmitted diseases, and ensure that patients are vaccinated against hepatitis A and B infection (see Related Resources). Most important, refer for medical treatment when indicated.

In patients such as Ms. D, the structure of court-ordered treatment can provide accountability, enforced abstinence, and mandated treatment resources. This, in turn, may give your patient a better chance to engage a recovering and better functioning frontal lobe to inhibit urges for methamphetamine use and manage stress.

Table 2

Other agents studied in methamphetamine dependence trials

| Drug | Investigation | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Baclofen6 (GABAergic) | Clinical trial | No statistically significant effect compared with placebo; post hoc analysis showed ‘small’ treatment effects vs placebo |

| Gabapentin6 (GABAergic) | Clinical trial | No statistically signicant effect compared with placebo; post hoc analysis showed no treatment effects vs placebo |

| Topiramate8 (anticonvulsant) | Laboratory | Accentuated (rather than diminished) subjective effects of MAP |

| Aripiprazole19 (SGA) | Laboratory | Decreased subjective effects of amphetamine |

| Modafinil5 (wakefulness agent) | Clinical trial | Successful trial in cocaine dependence; potential option for MAP |

| MAP: methamphetamine; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic | ||

CASE CONTINUED: Racing thoughts and psychosis

Before hospital admission, Ms. D was being treated with gabapentin, 300 mg bid, and sustained-release bupropion, 150 mg/d, for anxiety and dysphoria. Previously, she has received multiple antidepressants and mood stabilizers with reportedly little effect.

Initially guarded, she at first denies psychotic symptoms but acknowledges their extent several days later. She describes periods of 6 months or more when she feels “lost.” The treatment team titrates quetiapine up to 200 mg/d and restarts duloxetine, 30 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, based on her past positive response to this antidepressant.

Methamphetamine abuse can cause and exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. Keep in mind 2 priorities as you approach these symptoms:

Aim for abstinence. Methamphetamine abuse produces a remarkable array of adverse effects. It causes dysphoria, anxiety, and psychosis during active use and in the interval after initial abstinence. Many of methamphetamine’s use and withdrawal symptoms resolve with time, however, and may not require pharmacologic treatment.31 Therefore, achieving abstinence and keeping patients in treatment is high priority.

Use behavioral approaches whenever feasible. Balance the need to use benzodiazepines for ongoing treatment of severe anxiety or agitation with the high risk of addiction or diversion in this group. Anxiety may resolve over time in association with sustained abstinence. Similarly, receiving treatment for methamphetamine dependence and maintaining abstinence appears to ease depressive symptoms, as shown by sustained improvements in Beck Depression Inventory scores at 1 year.32

Manage stress. Stress can worsen psychiatric symptoms, trigger methamphetamine abuse relapse and psychosis, and acutely and chronically augment methamphetamine’s toxic effects.33 You can help patients manage stress by:

- providing case management and CBT training

- advising them about proper sleep, nutrition, and medical care.

Targeting psychiatric symptoms

Step 3 in the chronic disease management approach to methamphetamine dependence is to identify and target psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidities. When approaching psychiatric symptoms, high priorities are to aim for abstinence and manage the patient’s stress (Box 3).31-33

In clinical practice, we find it difficult to diagnostically categorize and treat methamphetamine-abusing patients who show residual post-acute psychotic symptoms. Some appear to have no risk factors for primary psychotic illness, and their symptoms show an association with the severity of their past methamphetamine abuse.

Other patient presentations can be difficult to separate from family histories of psychotic illness. Research suggests that genetic risk factors may be associated with methamphetamine psychosis in some vulnerable patients.35

Unfortunately, no data exist to guide the use of antipsychotics to maintain symptom control. Some patients may need low-dose antipsychotics for maintenance treatment, and second-generation antipsychotics may have a theoretical advantage over first-generation antipsychotics. Use your clinical judgment in determining dosing and treatment duration, and in weighing risks and benefits of continued treatment.

Using imaging, researchers found aggression severity to be directly correlated with past total methamphetamine use and globally decreased serotonin transporter density.36 Serotonin transporter densities were 30% lower in methamphetamine users vs controls after >1 year of abstinence.

CASE CONTINUED: Discharge plans

Because of the severity of her psychiatric symptoms, Ms. D is unable to return to the halfway house after discharge. As her treatment team works to coordinate discharge placement, Ms. D continues to improve. Her psychotic and dysphoria symptoms resolve, and she shows increased spontaneity. These changes—attributed to supports during hospitalization, decreased stressors, and quetiapine treatment—continue until her discharge to a combined mental illness and chemical dependence program.

- Methamphetamine use and sexually transmitted diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/std/DearColleagueRiskBehaviorMetUse8-18-2006.pdf.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse Blending Initiative. Promoting Awareness of Motivational Incentives (PAMI). www.drugabuse.gov/blending/PAMI.html.

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Baclofen • various

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Trazodone • Desyrel

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Clinicians could become discouraged when confronting methamphetamine-dependent patients’ wide-ranging psychiatric symptoms.

These patients often present with:

- overlapping primary psychiatric syndromes and secondary substance abuse

- complex histories fraught with psychological trauma, limited social supports, and court involvement.

Treatment can be successful, however, and patients can change their addictive behaviors with a chronic disease management approach that targets the drug’s cognitive sequelae and psychiatric effects. Medications show limited benefit (Box 1),1-8 but behavioral treatments—including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational incentives—have proven efficacy in treating methamphetamine addiction.

This article discusses how to counteract methamphetamine’s negative cognitive effects and enable patients to engage in psychosocial treatment. Our discussion is informed by an extensive literature search and clinical experience from treating patients in the Midwest—at the geographic heart of the “meth” epidemic.

CASE REPORT: Overwhelmed and suicidal

Ms. D, age 27, presents to the emergency department with anxiety, dysphoria, and a plan to commit suicide by overdose. She feels overwhelmed by her 4-hour-a-day customer service job—a prerequisite for staying at the halfway house where she has lived for 2 months. She has a 13-year history of polysubstance dependence and is under court order to complete chemical dependence treatment or go to jail.

No medications are FDA-approved for treating methamphetamine dependence, and evidence supporting medication use in methamphetamine dependence is extremely limited. Research efforts are aimed at finding medications that might be neuroprotective, decrease craving, block reinforcement mechanisms, or affect other factors behind methamphetamine addiction and relapse.1 Most trials have been conducted in animal models or controlled laboratory evaluations of drug effects on methamphetamine-induced states.

Bupropion has shown slight treatment efficacy, possibly by decreasing neuronal damage and blocking reinforcement.2-4 Modafinil5 and baclofen6 may have potential, but evidence is lacking.

Some results have been unexpectedly negative. Sertraline might be contraindicated in methamphetamine dependence treatment, according to results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial7 of sertraline and contingency management (Table 1). In a human laboratory study,8 topiramate accentuated—rather than diminished—subjective response to methamphetamine (Table 2).

Ms. D began using drugs at age 14 and has 3 convictions for driving under the influence of alcohol. An average student, she dropped out of high school but obtained a GED certificate. She first had psychiatric contact at age 16 and has been diagnosed at various times with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorder. She also has been violently sexually assaulted while engaging in prostitution to support her drug habit.

Ms. D has been hospitalized multiple times—voluntarily and involuntarily—in dual diagnosis treatment centers. Her 5-year-old son no longer lives with her, and she has limited social supports beyond her parents, who live in a neighboring state.

Table 1

Antidepressant trials for treating methamphetamine dependence

| Drug | Investigation | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bupropion2-4 | Laboratory | Safety of bupropion with MAP |

| Laboratory | Reduced subjective effects and cue-induced craving | |

| Clinical trial | Trend toward reduced MAP use compared with placebo | |

| Sertraline7 | Clinical trial | Sertraline-treated subjects showed higher use of MAP compared with those receiving placebo and were less likely to complete treatment |

| MAP: methamphetamine | ||

3-step approach

For patients such as Ms. D, clinical evidence supports a 3-step approach to treating methamphetamine dependence:

- step 1: institute acute management and stabilization

- step 2: eliminate or decrease methamphetamine use to “move the frontal lobe back to the front”

- step 3: identify and target psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidities.

- help her eliminate or decrease methamphetamine use to allow neuronal systems to recover

- target maladaptive behaviors that hinder sobriety while providing motivational incentives to help her maintain a methamphetamine-free life.

How ‘meth’ affects cognition

Methamphetamine use has been associated with cognitive dysfunction at initial abstinence and even years later in some patients.10 Ms. D’s cognitive limitations in a fast-paced customer service job—even though hours are limited—lead to anxiety, dysphoria, and loss of self-esteem when she can’t manage patrons’ requests.

Methamphetamine has profound acute and chronic effects on the sympathetic nervous system, and dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic neuronal networks. Most evidence of chronic neuronal effects comes from animal research and reflects toxic damage to dopaminergic and serotonergic neuronal systems. Postmortem human studies of direct neurotoxicity from chronic methamphetamine exposure show:

- decreased dopamine and tyrosine hydroxylase levels

- reduced concentrations of dopamine transporters.11

In chronic methamphetamine abusers, functional magnetic resonance imaging, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and positron emission tomography show:

- changes in neurotransmitter, protein, brain metabolism, and transporter levels

- damage in multiple brain areas including the frontal region, basal ganglia, grey matter, corpus callosum, and striatum; smaller hippocampi; and cerebral vasculature changes.14-16

CASE CONTINUED: Does she understand?

After Ms. D is stabilized, her case manager expresses concern about her ability to follow through with treatment planning. He says, “I just don’t think she understands some of the things we discuss.” She then is referred for neuropsychological testing, which shows clear cognitive impairment. Specifically, she has a slowed rate of thinking, general cognitive ineficiency, deficits in learning and memory retention, and mild impulsivity.

Patients with a history of extensive methamphetamine abuse are ruled by the limbic system and may have higher cortical damage that complicates initiating, maintaining, and fully participating in treatment. Patients’ deficits in memory, executive functioning, attention, and cognitive speed may require you to simplify, repeat, and otherwise modify your treatment plan. You will need to provide clear instructions and consistent support—individually and psychosocially—and to recognize and reinforce patients’ treatment gains.

Even before using methamphetamine, patients may have had academic problems or learning disabilities that will compromise their ability to participate in treatment. Infection with HIV, syphilis, or hepatitis C can further hamper cognitive function.18

What treatments are effective?

Medications. Evidence is extremely limited, and no medications are approved to treat methamphetamine-addicted patients. Bupropion has shown some efficacy (Table 1),2-4,7 but other drugs such as sertraline and topiramate may aggravate rather than diminish methamphetamine dependence (Table 2).5,6,8,19

Behavioral treatments supply the evidence basis for methamphetamine dependence treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),20 contingency management (CM),21,22 and a manualized structured treatment—the Matrix Model23—all have proven efficacy.

CBT involves functional analysis and skills training. Patients are guided through analyzing their drug use and associated cognitions, emotions, and expectations and in identifying situations that trigger methamphetamine use or relapse. Skills training involves identifying, reinforcing, and practicing coping skills to help the patient avoid drug use and reinforce the ability to refuse use.

CM is based on operant conditioning—the use of consequences to modify behavior. It involves establishing a “contingent” relationship between a desired behavior/outcome (such as methamphetamine-free urinalysis) and delivering a positive reinforcing event to promote abstinence:

- Vouchers, privileges, or small amounts of money linked to healthy behaviors serve as incentives for negative urine testing.

- Rewards increase as periods of confirmed abstinence lengthen and are reset to smaller rewards if relapse occurs.

CM does not require extensive staff training and has been described as relatively simple to implement. CM also has been used successfully in urban gay and bisexual men with methamphetamine dependence (Box 2).18,25-29

Although CM’s efficacy is well-supported by clinical trials, we have encountered some resistance to the idea of “paying individuals to not use drugs” when training medical students, allied health staff, and residents. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) supports the use of motivational incentives in treating substance abuse and offers support materials, resources, and training on this approach (see Related Resources).

Multiple studies show that CBT and CM are equally effective for treating chronic methamphetamine abuse at a 1-year follow-up, although CM may be more effective than CBT for acute treatment.

The Matrix model is a 4-month intensive, manualized treatment program that uses CBT, education on drug effects, positive reinforcement for intended behavioral change, and a 12-step approach.

Methamphetamine dependence outcomes based on the Matrix treatment model were compared with community treatment as usual in a project sponsored by The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.30 End-point outcomes were similar, but the Matrix treatment was more effective in early treatment, including decreased urinalyses positive for methamphetamine and increased abstinence.

Methamphetamine use is estimated to be 5 to 10 times more prevalent in U.S. urban gay and bisexual groups than in the general population25 and likely is contributing to rising human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection rates in men having sex with men (MSM).

Used to enhance sexual performance, libido, and mood, methamphetamine is associated with increased rates of unprotected anal sex and multiple partners in MSM.26 An HIV infection rate of 61% was reported in methamphetamine-dependent MSM seeking treatment in a Los Angeles clinical trial.27 Methamphetamine also results in high-risk sexual practices and multiple partners among heterosexual men and women.28

Although seroconverted men report using methamphetamine to alleviate HIV-associated depression, the combination of HIV infection and methamphetamine use may have powerful negative effects. Methamphetamine use is associated with HIV treatment nonadherence and also may suppress immune function.29 Cognitive impairments associated with HIV and methamphetamine use are additive and are further exacerbated by hepatitis C infection.18

Recommendation. Screen for methamphetamine use in MSM populations, and educate these patients about risks associated with methamphetamine use. In all patient groups who report using methamphetamine, provide counseling on high-risk sexual behavior, screen for sexually transmitted diseases, and ensure that patients are vaccinated against hepatitis A and B infection (see Related Resources). Most important, refer for medical treatment when indicated.

In patients such as Ms. D, the structure of court-ordered treatment can provide accountability, enforced abstinence, and mandated treatment resources. This, in turn, may give your patient a better chance to engage a recovering and better functioning frontal lobe to inhibit urges for methamphetamine use and manage stress.

Table 2

Other agents studied in methamphetamine dependence trials

| Drug | Investigation | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Baclofen6 (GABAergic) | Clinical trial | No statistically significant effect compared with placebo; post hoc analysis showed ‘small’ treatment effects vs placebo |

| Gabapentin6 (GABAergic) | Clinical trial | No statistically signicant effect compared with placebo; post hoc analysis showed no treatment effects vs placebo |

| Topiramate8 (anticonvulsant) | Laboratory | Accentuated (rather than diminished) subjective effects of MAP |

| Aripiprazole19 (SGA) | Laboratory | Decreased subjective effects of amphetamine |

| Modafinil5 (wakefulness agent) | Clinical trial | Successful trial in cocaine dependence; potential option for MAP |

| MAP: methamphetamine; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic | ||

CASE CONTINUED: Racing thoughts and psychosis

Before hospital admission, Ms. D was being treated with gabapentin, 300 mg bid, and sustained-release bupropion, 150 mg/d, for anxiety and dysphoria. Previously, she has received multiple antidepressants and mood stabilizers with reportedly little effect.

Initially guarded, she at first denies psychotic symptoms but acknowledges their extent several days later. She describes periods of 6 months or more when she feels “lost.” The treatment team titrates quetiapine up to 200 mg/d and restarts duloxetine, 30 mg/d, for depressive symptoms, based on her past positive response to this antidepressant.

Methamphetamine abuse can cause and exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. Keep in mind 2 priorities as you approach these symptoms:

Aim for abstinence. Methamphetamine abuse produces a remarkable array of adverse effects. It causes dysphoria, anxiety, and psychosis during active use and in the interval after initial abstinence. Many of methamphetamine’s use and withdrawal symptoms resolve with time, however, and may not require pharmacologic treatment.31 Therefore, achieving abstinence and keeping patients in treatment is high priority.

Use behavioral approaches whenever feasible. Balance the need to use benzodiazepines for ongoing treatment of severe anxiety or agitation with the high risk of addiction or diversion in this group. Anxiety may resolve over time in association with sustained abstinence. Similarly, receiving treatment for methamphetamine dependence and maintaining abstinence appears to ease depressive symptoms, as shown by sustained improvements in Beck Depression Inventory scores at 1 year.32

Manage stress. Stress can worsen psychiatric symptoms, trigger methamphetamine abuse relapse and psychosis, and acutely and chronically augment methamphetamine’s toxic effects.33 You can help patients manage stress by:

- providing case management and CBT training

- advising them about proper sleep, nutrition, and medical care.

Targeting psychiatric symptoms

Step 3 in the chronic disease management approach to methamphetamine dependence is to identify and target psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidities. When approaching psychiatric symptoms, high priorities are to aim for abstinence and manage the patient’s stress (Box 3).31-33

In clinical practice, we find it difficult to diagnostically categorize and treat methamphetamine-abusing patients who show residual post-acute psychotic symptoms. Some appear to have no risk factors for primary psychotic illness, and their symptoms show an association with the severity of their past methamphetamine abuse.

Other patient presentations can be difficult to separate from family histories of psychotic illness. Research suggests that genetic risk factors may be associated with methamphetamine psychosis in some vulnerable patients.35

Unfortunately, no data exist to guide the use of antipsychotics to maintain symptom control. Some patients may need low-dose antipsychotics for maintenance treatment, and second-generation antipsychotics may have a theoretical advantage over first-generation antipsychotics. Use your clinical judgment in determining dosing and treatment duration, and in weighing risks and benefits of continued treatment.

Using imaging, researchers found aggression severity to be directly correlated with past total methamphetamine use and globally decreased serotonin transporter density.36 Serotonin transporter densities were 30% lower in methamphetamine users vs controls after >1 year of abstinence.

CASE CONTINUED: Discharge plans

Because of the severity of her psychiatric symptoms, Ms. D is unable to return to the halfway house after discharge. As her treatment team works to coordinate discharge placement, Ms. D continues to improve. Her psychotic and dysphoria symptoms resolve, and she shows increased spontaneity. These changes—attributed to supports during hospitalization, decreased stressors, and quetiapine treatment—continue until her discharge to a combined mental illness and chemical dependence program.

- Methamphetamine use and sexually transmitted diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/std/DearColleagueRiskBehaviorMetUse8-18-2006.pdf.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse Blending Initiative. Promoting Awareness of Motivational Incentives (PAMI). www.drugabuse.gov/blending/PAMI.html.

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Baclofen • various

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Trazodone • Desyrel

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Vocci FJ, Acri J, Elkashef A. Medication development for addictive disorders: the state of the science. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1432-4.

2. Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, 2nd, et al. Safety of intravenous methamphetamine administration during treatment with bupropion. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;182:426-35.

3. Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, et al. Bupropion reduces methamphetamine-induced subjective effects and cue-induced craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31:1537-44.

4. Ling W, Rawson R, Shoptaw S. Management of methamphetamine abuse and dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2006;8:345-54.

5. Umanoff DF. Trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005;30:2298; author reply 2299-300.

6. Heinzerling KG, Shoptaw S, Peck JA, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of baclofen and gabapentin for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;85:177-84.

7. Shoptaw S, Huber A, Peck J, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline and contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;85:12-8.

8. Johnson BA, Roache JD, Ait-Daoud N, et al. Effects of acute topiramate dosing on methamphetamine-induced subjective mood. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;10:85-98.

9. Bostwick J, Lineberry T. The ‘meth’ epidemic: Managing acute psychosis, agitation, and suicide risk. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):46-62.

10. Simon SL, Dacey J, Glynn S, et al. The effect of relapse on cognition in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat 2004;27:59-66.

11. Wilson JM, Kalasinsky KS, Levey AI, et al. Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic methamphetamine users. Nat Med 1996;2:699-703.

12. Moszczynska A, Fitzmaurice P, Ang L, et al. Why is parkinsonism not a feature of human methamphetamine users? Brain 2004;127:363-70.

13. Armstrong BD, Noguchi KK. The neurotoxic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and methamphetamine on serotonin, dopamine, and GABAergic terminals: an in-vitro autoradiographic study in rats. Neurotoxicology 2004;25:905-14.

14. London ED, Berman SM, Voytek B, et al. Cerebral metabolic dysfunction and impaired vigilance in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:770-8.

15. London ED, Simon SL, Berman SM, et al. Mood disturbances and regional cerebral metabolic abnormalities in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:73-84.

16. Nordahl TE, Salo R, Leamon M. Neuropsychological effects of chronic methamphetamine use on neurotransmitters and cognition: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;15:317-25.

17. Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Chang L, et al. Partial recovery of brain metabolism in methamphetamine abusers after protracted abstinence. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:242-8.

18. Cherner M, Letendre S, Heaton RK, et al. Hepatitis C augments cognitive deficits associated with HIV infection and methamphetamine. Neurology 2005;64:1343-7.

19. Stoops WW. Aripiprazole as a potential pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: human laboratory studies with damphetamine. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;14:413-21.

20. Yen CF, Wu HY, Yen JY, Ko CH. Effects of brief cognitive-behavioral interventions on confidence to resist the urges to use heroin and methamphetamine in relapse-related situations. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192:788-91.

21. Roll JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, et al. Contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1993-9.

22. Shoptaw S, Klausner JD, Reback CJ, et al. A public health response to the methamphetamine epidemic: the implementation of contingency management to treat methamphetamine dependence. BMC Public Health 2006;6:214.-

23. Shoptaw S, Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Obert JL. The Matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: evidence of efficacy. J Addict Dis 1994;13:129-41.

24. Sindelar J, Elbel B, Petry NM. What do we get for our money? Cost-effectiveness of adding contingency management. Addiction 2007;102:309-16.

25. Shoptaw S. Methamphetamine use in urban gay and bisexual populations. Top HIV Med 2006;14:84-7.

26. Bolding G, Hart G, Sherr L, Elford J. Use of crystal methamphetamine among gay men in London. Addiction 2006;101:1622-30.

27. Peck JA, Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, et al. HIV-associated medical, behavioral, and psychiatric characteristics of treatment-seeking, methamphetamine-dependent men who have sex with men. J Addict Dis 2005;24:115-32.

28. Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. The context of sexual risk behavior among heterosexual methamphetamine users. Addict Behav 2004;29:807-10.

29. Mahajan SD, Hu Z, Reynolds JL, et al. Methamphetamine modulates gene expression patterns in monocyte derived mature dendritic cells: implications for HIV-1 pathogenesis. Mol Diagn Ther 2006;10:257-69.

30. Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, et al. A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction 2004;99:708-17.

31. McGregor C, Srisurapanont M, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. The nature, time course and severity of methamphetamine withdrawal. Addiction 2005;100:1320-9.

32. Peck JA, Reback CJ, Yang X, et al. Sustained reductions in drug use and depression symptoms from treatment for drug abuse in methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men. J Urban Health 2005;82:i100-8.

33. Matuszewich L, Yamamoto BK. Chronic stress augments the long-term and acute effects of methamphetamine. Neuroscience 2004;124:637-46.

34. Batki SL, Harris DS. Quantitative drug levels in stimulant psychosis: relationship to symptom severity, catecholamines and hyperkinesia. Am J Addict 2004;13:461-70.

35. Suzuki A, Nakamura K, Sekine Y, et al. An association study between catechol-O-methyl transferase gene polymorphism and methamphetamine psychotic disorder. Psychiatr Genet 2006;16:133-8.

36. Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Takei N, et al. Brain serotonin transporter density and aggression in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:90-100.

1. Vocci FJ, Acri J, Elkashef A. Medication development for addictive disorders: the state of the science. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1432-4.

2. Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, 2nd, et al. Safety of intravenous methamphetamine administration during treatment with bupropion. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;182:426-35.

3. Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, et al. Bupropion reduces methamphetamine-induced subjective effects and cue-induced craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31:1537-44.

4. Ling W, Rawson R, Shoptaw S. Management of methamphetamine abuse and dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2006;8:345-54.

5. Umanoff DF. Trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005;30:2298; author reply 2299-300.

6. Heinzerling KG, Shoptaw S, Peck JA, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of baclofen and gabapentin for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;85:177-84.

7. Shoptaw S, Huber A, Peck J, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline and contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;85:12-8.

8. Johnson BA, Roache JD, Ait-Daoud N, et al. Effects of acute topiramate dosing on methamphetamine-induced subjective mood. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;10:85-98.

9. Bostwick J, Lineberry T. The ‘meth’ epidemic: Managing acute psychosis, agitation, and suicide risk. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(11):46-62.

10. Simon SL, Dacey J, Glynn S, et al. The effect of relapse on cognition in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat 2004;27:59-66.

11. Wilson JM, Kalasinsky KS, Levey AI, et al. Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic methamphetamine users. Nat Med 1996;2:699-703.

12. Moszczynska A, Fitzmaurice P, Ang L, et al. Why is parkinsonism not a feature of human methamphetamine users? Brain 2004;127:363-70.

13. Armstrong BD, Noguchi KK. The neurotoxic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and methamphetamine on serotonin, dopamine, and GABAergic terminals: an in-vitro autoradiographic study in rats. Neurotoxicology 2004;25:905-14.

14. London ED, Berman SM, Voytek B, et al. Cerebral metabolic dysfunction and impaired vigilance in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:770-8.

15. London ED, Simon SL, Berman SM, et al. Mood disturbances and regional cerebral metabolic abnormalities in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:73-84.

16. Nordahl TE, Salo R, Leamon M. Neuropsychological effects of chronic methamphetamine use on neurotransmitters and cognition: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;15:317-25.

17. Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Chang L, et al. Partial recovery of brain metabolism in methamphetamine abusers after protracted abstinence. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:242-8.

18. Cherner M, Letendre S, Heaton RK, et al. Hepatitis C augments cognitive deficits associated with HIV infection and methamphetamine. Neurology 2005;64:1343-7.

19. Stoops WW. Aripiprazole as a potential pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: human laboratory studies with damphetamine. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;14:413-21.

20. Yen CF, Wu HY, Yen JY, Ko CH. Effects of brief cognitive-behavioral interventions on confidence to resist the urges to use heroin and methamphetamine in relapse-related situations. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192:788-91.

21. Roll JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, et al. Contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1993-9.

22. Shoptaw S, Klausner JD, Reback CJ, et al. A public health response to the methamphetamine epidemic: the implementation of contingency management to treat methamphetamine dependence. BMC Public Health 2006;6:214.-

23. Shoptaw S, Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Obert JL. The Matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: evidence of efficacy. J Addict Dis 1994;13:129-41.

24. Sindelar J, Elbel B, Petry NM. What do we get for our money? Cost-effectiveness of adding contingency management. Addiction 2007;102:309-16.

25. Shoptaw S. Methamphetamine use in urban gay and bisexual populations. Top HIV Med 2006;14:84-7.

26. Bolding G, Hart G, Sherr L, Elford J. Use of crystal methamphetamine among gay men in London. Addiction 2006;101:1622-30.

27. Peck JA, Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, et al. HIV-associated medical, behavioral, and psychiatric characteristics of treatment-seeking, methamphetamine-dependent men who have sex with men. J Addict Dis 2005;24:115-32.

28. Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. The context of sexual risk behavior among heterosexual methamphetamine users. Addict Behav 2004;29:807-10.

29. Mahajan SD, Hu Z, Reynolds JL, et al. Methamphetamine modulates gene expression patterns in monocyte derived mature dendritic cells: implications for HIV-1 pathogenesis. Mol Diagn Ther 2006;10:257-69.

30. Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, et al. A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction 2004;99:708-17.

31. McGregor C, Srisurapanont M, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. The nature, time course and severity of methamphetamine withdrawal. Addiction 2005;100:1320-9.

32. Peck JA, Reback CJ, Yang X, et al. Sustained reductions in drug use and depression symptoms from treatment for drug abuse in methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men. J Urban Health 2005;82:i100-8.

33. Matuszewich L, Yamamoto BK. Chronic stress augments the long-term and acute effects of methamphetamine. Neuroscience 2004;124:637-46.

34. Batki SL, Harris DS. Quantitative drug levels in stimulant psychosis: relationship to symptom severity, catecholamines and hyperkinesia. Am J Addict 2004;13:461-70.

35. Suzuki A, Nakamura K, Sekine Y, et al. An association study between catechol-O-methyl transferase gene polymorphism and methamphetamine psychotic disorder. Psychiatr Genet 2006;16:133-8.

36. Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Takei N, et al. Brain serotonin transporter density and aggression in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:90-100.

The ‘meth’ epidemic: Managing acute psychosis, agitation, and suicide risk

Methamphetamine abuse has spread to every region of the United States in the past 10 years (Table 1).1 Its long-lasting, difficult-to-treat medical effects destroy lives and create psychiatric and physical comorbidities that confound clinicians in emergency rooms and community practice settings.

This first in a series of two articles describes methamphetamine’s growing use and offers guidance to identify abusers and manage acute “meth” intoxication. Methamphetamine-abusing patients can appear in any area of acute psychiatric practice—during emergency department (ED) evaluations, medical-surgical consultations, and inpatient psychiatric admissions. Using case examples, we describe key clinical principles to help you assess patients in each of these settings.

Table 1

10-year growth in hospitalization rates

for methamphetamine/amphetamine use*

| Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | 1993 | 2003 |

| U.S. national rate | 13 | 56 |

| Northeast | ||

| Connecticut | 1 | 4 |

| Maine | 2 | 5 |

| Massachusetts | <1 | 2 |

| New Hampshire | <1 | 2 |

| New Jersey | 3 | 2 |

| New York | 2 | 4 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 2 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | 2 |

| Vermont | 5 | 4 |

| South | ||

| Alabama | 1 | 45 |

| Arkansas | 13 | 130 |

| Delaware | 2 | 2 |

| District of Columbia | — | 2 |

| Florida | 2 | 7 |

| Georgia | 3 | 39 |

| Kentucky | — | 20 |

| Louisiana | 4 | 21 |

| Maryland | 1 | 3 |

| Mississippi | — | 23 |

| North Carolina | <1 | 4 |

| Oklahoma | 19 | 117 |

| South Carolina | 1 | 9 |

| Tennessee | † | 6 |

| Texas | 7 | 17 |

| Virginia | 1 | 4 |

| West Virginia | <1 | — |

| Midwest | ||

| Illinois | 1 | 19 |

| Indiana | 3 | 28 |

| Iowa | 13 | 213 |

| Kansas | 15 | 65 |

| Michigan | 2 | 7 |

| Minnesota | 8 | 100 |

| Missouri | 7 | 84 |

| Nebraska | 8 | 117 |

| North Dakota | 3 | 44 |

| Ohio | 3 | 3 |

| South Dakota | 5 | 90 |

| Wisconsin | <1 | 5 |

| West | ||

| Alaska | 4 | 13 |

| Arizona | — | 36 |

| California | 66 | 212 |

| Colorado | 18 | 86 |

| Hawaii | 52 | 241 |

| Idaho | 20 | 72 |

| Montana | 30 | 133 |

| Nevada | 59 | 176 |

| New Mexico | 7 | 10 |

| Oregon | 98 | 251 |

| Utah | 16 | 186 |

| Washington | 18 | 143 |

| Wyoming | 15 | 209 |

| * Per 100,000 population aged 12 or older, with methamphetamine/amphetamine use as the primary diagnosis. Percentages in boldface exceed the national rate for that year. | ||

| † <0.05% | ||

| –No data available | ||

| Source: Reference 1 | ||

Scourge of the Heartland

A stimulant first synthesized in Japan,2 methamphetamine is the primary drug of abuse in Asia3 and the leading drug threat in the United States, according to U.S. law enforcement officials.4 Although most methamphetamine used in the United States is manufactured in “super-labs” along the U.S.-Mexican border,4 the drug is also easily made from common ingredients in small-scale home laboratories.

These smaller domestic “meth labs” have devastated rural communities and altered demographic patterns of methamphetamine abuse (Figure 1).5 Two aspects of rural life—relative isolation and availability of ingredients for production—proved critical in the initial spread of methamphetamine production and use in the United States. As a result, production by smaller labs is being targeted by state and federal law enforcement officers, who have had some success in eradicating this scourge (Box 1, Figure 2).6-9

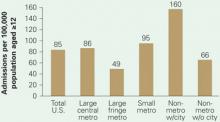

Figure 1 Substance abuse treatment admission rates

for methamphetamine-related diagnoses

Substance abuse treatment centers in rural areas had the highest admission rates for methamphetamine/amphetamine-related diagnoses in 2004. Admission rates in nonmetropolitan regions containing cities with populations >10,000 were triple those of suburbs, nearly twice those of big cities, and twice the U.S. average.

Figure 2 Methamphetamine clandestine laboratory incidents,* 2005

* Incidents include chemicals, contaminated glass, and equipment used in methamphetamine production found by law enforcement agencies at laboratories or dump sites.

Source: Drug Enforcement Administration database, reference 9Box 1

Dangerous recipes. The ease with which methamphetamine can be “cooked” in a home kitchen from ingredients available in pharmacies and hardware stores has contributed to the drug’s rapid spread. Meth users produce their own “fixes” using recipes readily available on the Internet and passed on by other “cooks.”6 The combination of inexperienced or intoxicated cooks, homemade equipment, and highly flammable ingredients results in frequent fires and explosions, often with injuries to home occupants and emergency responders.7

Meth labs have been estimated to produce 6 pounds of toxic waste for each 1 pound of methamphetamine produced. Composed of acid, lye, and phosphorus, this waste typically is dumped into ditches, rivers, yards, and drains. The fine-particulate methamphetamine residue generated during home production settles on exposed household surfaces, leading to absorption by children and others who come into contact with it.6,8

Disastrous results. Methamphetamine cooking has caused a social, environmental, and medical disaster—particularly in the Midwest (Figure 2), although the situation has improved in the past 2 years. Many states have passed laws restricting and monitoring sales of the methamphetamine ingredients ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. A change in U.S. law prohibiting pseudoephedrine imports in bulk from Canada has decreased domestic “superlab” production.9 Although these laws appear to have slowed U.S. manufacturing, the drug is still readily available, predominantly smuggled in from large-scale producers in Mexico.

Symptoms of ‘Meth’ Use

Physiologic effects. Methamphetamine is taken because it induces euphoria, anorexia, and increased energy, sexual stimulation, and alertness. Initial use evolves into abuse because of the drug’s highly addictive properties. Available in multiple forms and carrying a variety of labels (see Related resources), methamphetamine causes CNS release of monoamines—particularly dopamine—and damages dopaminergic neurons in the striatum and serotonergic neurons in the frontal lobes, striatum, and hippocampus.10,11

Through sympathetic nervous system activation, methamphetamine can cause reversible or irreversible damage to organ systems (Table 2).12-17

Table 2

Physiologic signs of methamphetamine abuse

| Vital signs | Tachycardia |

| Hypertension | |

| Pyrexia | |

| Laboratory abnormalities | Metabolic acidosis |

| Evidence of rhabdomyolysis | |

| Organ damage | Cardiomyopathy |

| Acute coronary syndrome | |

| Pulmonary edema | |

| Stigmata of chronic use | Premature aging |

| Cachexia | |

| Discolored and fractured teeth | |

| Skin lesions from stereotypical scratching related to formication (“meth bugs”) and/or compulsive picking | |

| Source: References 12-17 | |