User login

Bedside Assessment of the Necessity of Daily Lab Testing for Patients Nearing Discharge

As part of the Choosing Wisely® campaign, the Society of Hospital Medicine recommends against performing “repetitive complete blood count [CBC] and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.”1 This recommendation stems from a body of research that shows that frequent or excessive phlebotomy can have negative consequences, including iatrogenic anemia (termed hospital-acquired anemia), which may necessitate blood transfusion.2 The downstream effects of potentially unnecessary testing, including the evaluation of false-positive results, must also be considered. Additional important effects include patient discomfort and disruption of sleep and unproductive work by hospital staff, including nurses, phlebotomists, and laboratory technicians.

Though interventions to reduce unnecessary daily labs have been previously evaluated, there are no studies that focus on decreasing lab testing on patients deemed clinically stable and close to discharge. This is in part due to the absence of clear criteria or guidelines to define clinical stability in the context of lab utilization.

We therefore aimed to implement a multifaceted, patient-centered initiative—the Necessity of Labs Assessed Bedside (NO LABS)—that focused on reducing lab testing in patients at 24 to 48 hours before discharge. We targeted the 24 to 48-hour period before the anticipated date of discharge, as this may be a period of greater stability and provide an opportunity to identify and decrease unnecessary testing.

METHODS

The study took place at Mount Sinai Hospital, which is an 1174-bed tertiary care teaching hospital in New York City. We targeted 2 inpatient medicine units where virtually all patients are assigned to a hospitalist rotating for a 2- to 4-week period, for the period of July 1, 2015, to July 31, 2016. These units employed bedside interdisciplinary rounds (IDR) attended by the hospitalist, social worker, case manager, nurse, nurse manager, and medical director. Bedside IDR focuses on the daily plan and patient safety by

As described by Dunn et al.,3 the IDR script included the following: a review of the plan of care by the hospitalist, identifying a patient’s personal goals for the day, a brief update of discharge planning (as appropriate), and a safety assessment performed by the nurse (identifying Foley catheters, falls risk, etc). We incorporated an inquiry into the daily IDR script identifying clinically stable patients for discharge in the next 24 to 48 hours (based on physician judgment), followed by a prompt to the hospitalist to discontinue labs when appropriate. The unit medical director and nurse manager were both tasked with prompting the hospitalist at the bedside. Our hospital utilizes computerized physician order entry. Lab orders were then discontinued by the clinician during rounds using a computer on wheels (or after rounds when one was not available). The hospitalist, unit medical director, and nurse manager were reminded about the project through weekly e-mails and in-person communication.

To assess whether the prompt was being incorporated consistently, an observer was added to rounds beginning in the second month of the project. The observer was present at least 3 times a week for the subsequent 3 months of the project. Our intervention also included education geared towards hospitalists, including a brief presentation on reducing unnecessary lab testing during a monthly hospitalist faculty meeting (the first and sixth month of the intervention). The group’s data on laboratory testing within the 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge were also presented at these monthly meetings (beginning 2 months into the intervention and monthly thereafter). Lastly, we provided the unit staff with unit-level metrics, biweekly for the first 3 months and every 2 to 3 months thereafter.

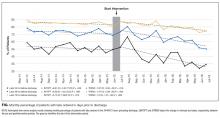

We extracted electronic medical record (EMR) data on lab utilization for patients on the 2 hospitalist units for the intervention period. Baseline data were obtained from July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015. Patients with a length of stay (LOS) ≤7 days (75th percentile) were included; on these units, longer stays were considered more likely to have complex social issues delaying discharge and thus less likely to require laboratory testing. We tracked ordering for 4 common lab tests: basic metabolic panel, CBC, CBC with differential, and the comprehensive metabolic panel. The primary outcome was the monthly percentage of patients for whom testing was ordered in the 24 and 48 hours preceding discharge. A secondary outcome was testing at 72 hours preceding discharge to identify any potential compensatory (increased) testing the evening prior. We applied a quasi-experimental interrupted time series design with a segmented regression analysis to estimate changes before and after our intervention, expressed in acute changes (change in intercept) and over time (changes in trend) while adjusting for preintervention trends. All analyses were performed with SAS v9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Our project was deemed a quality improvement project and thus an IRB submission was not required.

RESULTS

There were 1579 discharges in the preintervention period and 1308 discharges in the postintervention period. The average age of the patient population was similar in the baseline and postintervention groups (61.5 vs 59.3 years; P = 0.400), and there was no difference in the mean LOS before and after implementation (3.67 vs 3.68 days; P = 0.817).

DISCUSSION

Our structured, multifaceted approach effectively reduced daily lab testing in the 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge. Bedside IDR provided a unique opportunity to effectively communicate to the patient about necessary (or unnecessary) testing. Moreover, given the complexity of identifying clinical stability, our strategy focused on the onset of discharge planning, a more easily discernible and less obtrusive focal point to promote the discontinuation of lab testing.

Though the nature of bundled interventions can make it difficult to identify which intervention is most effective, we believe that all interventions were effective in different capacities during various phases in the intervention period. We believe that the decrease in lab testing in the 24 to 48 hours preceding discharge was primarily driven by the new rounding structure. This is evident in the significant decrease seen in the first few months of the intervention period. Six months into the intervention, we begin to see a decrease at 72 hours prior to discharge. Additionally, we see a decrease in the mean number of labs per patient day over the entire hospitalization period. We attribute these results to a gradual shift in the culture in our division as a direct consequence of educational sessions and individual feedback provided during this time.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use anticipated discharge as a correlate for clinical stability and therefore as an opportunity to prompt discontinuation of laboratory testing. Other studies evaluated interventions targeting the EMR and the ease with which providers can order recurring labs. These include restricting recurring orders in the EMR,4 a robust education and awareness campaign targeting house staff,5 and other multifaceted approaches to decreasing lab utilization,6 all of which have shown promising results. While these approaches show varying degrees of success, ours is unique in its focus on the period prior to discharge. In addition, the intervention can be readily implemented in settings that utilize scripted IDR. It also brings high-value decision-making to the bedside by informing the patient that in the setting of presumed clinical stability, no additional tests are warranted.

Our study has several limitations. First, while interdisciplinary discharge rounds are widely implemented,7,8 our rounds occur at the bedside and employ a script, potentially limiting generalizability. The structured prompting may be feasible during structured IDR in a standard conference room setting, though we did not assess this model. Second, bedside rounds only included patients who were able to participate. Rounding on patients unable to participate, such as patients with delirium with agitation, was done outside the patient room rather than at the bedside. A modified script was used in these instances (absent questions addressed to the patient), allowing for the prompt to be incorporated. These patients were included in the analysis. Lastly, as previously stated, we cannot clearly identify which intervention (the prompt, education, or feedback) most effectively led to a sustained decrease in lab ordering.

Our structured, multifaceted intervention reduced laboratory testing during the last 48 hours of admission. Hospitals that aim to decrease potentially unnecessary lab testing should consider implementing a bundle, including a prompt at a uniform and structured point during the hospitalization of patients who are expected to be discharged within 24 to 48 hours, clinician education, an audit, and feedback.

Disclosure

All authors report no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. PubMed

3. Dunn AS, Reyna, M, Radbill B, et al. The impact of bedside interdisciplinary rounds on length of stay and complications. J Hosp Med. 2017;3:137-142. PubMed

4. Iturrate E, Jubelt L, Volpicelli F, Hochman K. Optimize Your Electronic Medical Record to Increase Value: Reducing Laboratory Overutilization. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):215-220. PubMed

5. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a Resident-Led Project to Decrease Phlebotomy Rates in the Hospital: Think Twice, Stick Once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. PubMed

6. Corson AH, Fan VS, White T, et al. A Multifaceted Hospitalist Quality Improvement Intervention: Decreased Frequency of Common Labs. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):390-395. PubMed

7. Bhamidipati VS, Elliott DJ, Justice EM, Belleh E, Sonnad SS, Robinson EJ. Structure and outcomes of interdisciplinary rounds in hospitalized medicine patients: A systematic review and suggested taxonomy. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):513-523. PubMed

8. O’Leary, KJ, Sehgal NL, Terrell G, Williams MV, High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future Project Team. Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: a review and practical recommendations for improvement. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(1):48-54. PubMed

As part of the Choosing Wisely® campaign, the Society of Hospital Medicine recommends against performing “repetitive complete blood count [CBC] and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.”1 This recommendation stems from a body of research that shows that frequent or excessive phlebotomy can have negative consequences, including iatrogenic anemia (termed hospital-acquired anemia), which may necessitate blood transfusion.2 The downstream effects of potentially unnecessary testing, including the evaluation of false-positive results, must also be considered. Additional important effects include patient discomfort and disruption of sleep and unproductive work by hospital staff, including nurses, phlebotomists, and laboratory technicians.

Though interventions to reduce unnecessary daily labs have been previously evaluated, there are no studies that focus on decreasing lab testing on patients deemed clinically stable and close to discharge. This is in part due to the absence of clear criteria or guidelines to define clinical stability in the context of lab utilization.

We therefore aimed to implement a multifaceted, patient-centered initiative—the Necessity of Labs Assessed Bedside (NO LABS)—that focused on reducing lab testing in patients at 24 to 48 hours before discharge. We targeted the 24 to 48-hour period before the anticipated date of discharge, as this may be a period of greater stability and provide an opportunity to identify and decrease unnecessary testing.

METHODS

The study took place at Mount Sinai Hospital, which is an 1174-bed tertiary care teaching hospital in New York City. We targeted 2 inpatient medicine units where virtually all patients are assigned to a hospitalist rotating for a 2- to 4-week period, for the period of July 1, 2015, to July 31, 2016. These units employed bedside interdisciplinary rounds (IDR) attended by the hospitalist, social worker, case manager, nurse, nurse manager, and medical director. Bedside IDR focuses on the daily plan and patient safety by

As described by Dunn et al.,3 the IDR script included the following: a review of the plan of care by the hospitalist, identifying a patient’s personal goals for the day, a brief update of discharge planning (as appropriate), and a safety assessment performed by the nurse (identifying Foley catheters, falls risk, etc). We incorporated an inquiry into the daily IDR script identifying clinically stable patients for discharge in the next 24 to 48 hours (based on physician judgment), followed by a prompt to the hospitalist to discontinue labs when appropriate. The unit medical director and nurse manager were both tasked with prompting the hospitalist at the bedside. Our hospital utilizes computerized physician order entry. Lab orders were then discontinued by the clinician during rounds using a computer on wheels (or after rounds when one was not available). The hospitalist, unit medical director, and nurse manager were reminded about the project through weekly e-mails and in-person communication.

To assess whether the prompt was being incorporated consistently, an observer was added to rounds beginning in the second month of the project. The observer was present at least 3 times a week for the subsequent 3 months of the project. Our intervention also included education geared towards hospitalists, including a brief presentation on reducing unnecessary lab testing during a monthly hospitalist faculty meeting (the first and sixth month of the intervention). The group’s data on laboratory testing within the 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge were also presented at these monthly meetings (beginning 2 months into the intervention and monthly thereafter). Lastly, we provided the unit staff with unit-level metrics, biweekly for the first 3 months and every 2 to 3 months thereafter.

We extracted electronic medical record (EMR) data on lab utilization for patients on the 2 hospitalist units for the intervention period. Baseline data were obtained from July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015. Patients with a length of stay (LOS) ≤7 days (75th percentile) were included; on these units, longer stays were considered more likely to have complex social issues delaying discharge and thus less likely to require laboratory testing. We tracked ordering for 4 common lab tests: basic metabolic panel, CBC, CBC with differential, and the comprehensive metabolic panel. The primary outcome was the monthly percentage of patients for whom testing was ordered in the 24 and 48 hours preceding discharge. A secondary outcome was testing at 72 hours preceding discharge to identify any potential compensatory (increased) testing the evening prior. We applied a quasi-experimental interrupted time series design with a segmented regression analysis to estimate changes before and after our intervention, expressed in acute changes (change in intercept) and over time (changes in trend) while adjusting for preintervention trends. All analyses were performed with SAS v9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Our project was deemed a quality improvement project and thus an IRB submission was not required.

RESULTS

There were 1579 discharges in the preintervention period and 1308 discharges in the postintervention period. The average age of the patient population was similar in the baseline and postintervention groups (61.5 vs 59.3 years; P = 0.400), and there was no difference in the mean LOS before and after implementation (3.67 vs 3.68 days; P = 0.817).

DISCUSSION

Our structured, multifaceted approach effectively reduced daily lab testing in the 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge. Bedside IDR provided a unique opportunity to effectively communicate to the patient about necessary (or unnecessary) testing. Moreover, given the complexity of identifying clinical stability, our strategy focused on the onset of discharge planning, a more easily discernible and less obtrusive focal point to promote the discontinuation of lab testing.

Though the nature of bundled interventions can make it difficult to identify which intervention is most effective, we believe that all interventions were effective in different capacities during various phases in the intervention period. We believe that the decrease in lab testing in the 24 to 48 hours preceding discharge was primarily driven by the new rounding structure. This is evident in the significant decrease seen in the first few months of the intervention period. Six months into the intervention, we begin to see a decrease at 72 hours prior to discharge. Additionally, we see a decrease in the mean number of labs per patient day over the entire hospitalization period. We attribute these results to a gradual shift in the culture in our division as a direct consequence of educational sessions and individual feedback provided during this time.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use anticipated discharge as a correlate for clinical stability and therefore as an opportunity to prompt discontinuation of laboratory testing. Other studies evaluated interventions targeting the EMR and the ease with which providers can order recurring labs. These include restricting recurring orders in the EMR,4 a robust education and awareness campaign targeting house staff,5 and other multifaceted approaches to decreasing lab utilization,6 all of which have shown promising results. While these approaches show varying degrees of success, ours is unique in its focus on the period prior to discharge. In addition, the intervention can be readily implemented in settings that utilize scripted IDR. It also brings high-value decision-making to the bedside by informing the patient that in the setting of presumed clinical stability, no additional tests are warranted.

Our study has several limitations. First, while interdisciplinary discharge rounds are widely implemented,7,8 our rounds occur at the bedside and employ a script, potentially limiting generalizability. The structured prompting may be feasible during structured IDR in a standard conference room setting, though we did not assess this model. Second, bedside rounds only included patients who were able to participate. Rounding on patients unable to participate, such as patients with delirium with agitation, was done outside the patient room rather than at the bedside. A modified script was used in these instances (absent questions addressed to the patient), allowing for the prompt to be incorporated. These patients were included in the analysis. Lastly, as previously stated, we cannot clearly identify which intervention (the prompt, education, or feedback) most effectively led to a sustained decrease in lab ordering.

Our structured, multifaceted intervention reduced laboratory testing during the last 48 hours of admission. Hospitals that aim to decrease potentially unnecessary lab testing should consider implementing a bundle, including a prompt at a uniform and structured point during the hospitalization of patients who are expected to be discharged within 24 to 48 hours, clinician education, an audit, and feedback.

Disclosure

All authors report no conflicts of interest to disclose.

As part of the Choosing Wisely® campaign, the Society of Hospital Medicine recommends against performing “repetitive complete blood count [CBC] and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.”1 This recommendation stems from a body of research that shows that frequent or excessive phlebotomy can have negative consequences, including iatrogenic anemia (termed hospital-acquired anemia), which may necessitate blood transfusion.2 The downstream effects of potentially unnecessary testing, including the evaluation of false-positive results, must also be considered. Additional important effects include patient discomfort and disruption of sleep and unproductive work by hospital staff, including nurses, phlebotomists, and laboratory technicians.

Though interventions to reduce unnecessary daily labs have been previously evaluated, there are no studies that focus on decreasing lab testing on patients deemed clinically stable and close to discharge. This is in part due to the absence of clear criteria or guidelines to define clinical stability in the context of lab utilization.

We therefore aimed to implement a multifaceted, patient-centered initiative—the Necessity of Labs Assessed Bedside (NO LABS)—that focused on reducing lab testing in patients at 24 to 48 hours before discharge. We targeted the 24 to 48-hour period before the anticipated date of discharge, as this may be a period of greater stability and provide an opportunity to identify and decrease unnecessary testing.

METHODS

The study took place at Mount Sinai Hospital, which is an 1174-bed tertiary care teaching hospital in New York City. We targeted 2 inpatient medicine units where virtually all patients are assigned to a hospitalist rotating for a 2- to 4-week period, for the period of July 1, 2015, to July 31, 2016. These units employed bedside interdisciplinary rounds (IDR) attended by the hospitalist, social worker, case manager, nurse, nurse manager, and medical director. Bedside IDR focuses on the daily plan and patient safety by

As described by Dunn et al.,3 the IDR script included the following: a review of the plan of care by the hospitalist, identifying a patient’s personal goals for the day, a brief update of discharge planning (as appropriate), and a safety assessment performed by the nurse (identifying Foley catheters, falls risk, etc). We incorporated an inquiry into the daily IDR script identifying clinically stable patients for discharge in the next 24 to 48 hours (based on physician judgment), followed by a prompt to the hospitalist to discontinue labs when appropriate. The unit medical director and nurse manager were both tasked with prompting the hospitalist at the bedside. Our hospital utilizes computerized physician order entry. Lab orders were then discontinued by the clinician during rounds using a computer on wheels (or after rounds when one was not available). The hospitalist, unit medical director, and nurse manager were reminded about the project through weekly e-mails and in-person communication.

To assess whether the prompt was being incorporated consistently, an observer was added to rounds beginning in the second month of the project. The observer was present at least 3 times a week for the subsequent 3 months of the project. Our intervention also included education geared towards hospitalists, including a brief presentation on reducing unnecessary lab testing during a monthly hospitalist faculty meeting (the first and sixth month of the intervention). The group’s data on laboratory testing within the 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge were also presented at these monthly meetings (beginning 2 months into the intervention and monthly thereafter). Lastly, we provided the unit staff with unit-level metrics, biweekly for the first 3 months and every 2 to 3 months thereafter.

We extracted electronic medical record (EMR) data on lab utilization for patients on the 2 hospitalist units for the intervention period. Baseline data were obtained from July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015. Patients with a length of stay (LOS) ≤7 days (75th percentile) were included; on these units, longer stays were considered more likely to have complex social issues delaying discharge and thus less likely to require laboratory testing. We tracked ordering for 4 common lab tests: basic metabolic panel, CBC, CBC with differential, and the comprehensive metabolic panel. The primary outcome was the monthly percentage of patients for whom testing was ordered in the 24 and 48 hours preceding discharge. A secondary outcome was testing at 72 hours preceding discharge to identify any potential compensatory (increased) testing the evening prior. We applied a quasi-experimental interrupted time series design with a segmented regression analysis to estimate changes before and after our intervention, expressed in acute changes (change in intercept) and over time (changes in trend) while adjusting for preintervention trends. All analyses were performed with SAS v9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Our project was deemed a quality improvement project and thus an IRB submission was not required.

RESULTS

There were 1579 discharges in the preintervention period and 1308 discharges in the postintervention period. The average age of the patient population was similar in the baseline and postintervention groups (61.5 vs 59.3 years; P = 0.400), and there was no difference in the mean LOS before and after implementation (3.67 vs 3.68 days; P = 0.817).

DISCUSSION

Our structured, multifaceted approach effectively reduced daily lab testing in the 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge. Bedside IDR provided a unique opportunity to effectively communicate to the patient about necessary (or unnecessary) testing. Moreover, given the complexity of identifying clinical stability, our strategy focused on the onset of discharge planning, a more easily discernible and less obtrusive focal point to promote the discontinuation of lab testing.

Though the nature of bundled interventions can make it difficult to identify which intervention is most effective, we believe that all interventions were effective in different capacities during various phases in the intervention period. We believe that the decrease in lab testing in the 24 to 48 hours preceding discharge was primarily driven by the new rounding structure. This is evident in the significant decrease seen in the first few months of the intervention period. Six months into the intervention, we begin to see a decrease at 72 hours prior to discharge. Additionally, we see a decrease in the mean number of labs per patient day over the entire hospitalization period. We attribute these results to a gradual shift in the culture in our division as a direct consequence of educational sessions and individual feedback provided during this time.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use anticipated discharge as a correlate for clinical stability and therefore as an opportunity to prompt discontinuation of laboratory testing. Other studies evaluated interventions targeting the EMR and the ease with which providers can order recurring labs. These include restricting recurring orders in the EMR,4 a robust education and awareness campaign targeting house staff,5 and other multifaceted approaches to decreasing lab utilization,6 all of which have shown promising results. While these approaches show varying degrees of success, ours is unique in its focus on the period prior to discharge. In addition, the intervention can be readily implemented in settings that utilize scripted IDR. It also brings high-value decision-making to the bedside by informing the patient that in the setting of presumed clinical stability, no additional tests are warranted.

Our study has several limitations. First, while interdisciplinary discharge rounds are widely implemented,7,8 our rounds occur at the bedside and employ a script, potentially limiting generalizability. The structured prompting may be feasible during structured IDR in a standard conference room setting, though we did not assess this model. Second, bedside rounds only included patients who were able to participate. Rounding on patients unable to participate, such as patients with delirium with agitation, was done outside the patient room rather than at the bedside. A modified script was used in these instances (absent questions addressed to the patient), allowing for the prompt to be incorporated. These patients were included in the analysis. Lastly, as previously stated, we cannot clearly identify which intervention (the prompt, education, or feedback) most effectively led to a sustained decrease in lab ordering.

Our structured, multifaceted intervention reduced laboratory testing during the last 48 hours of admission. Hospitals that aim to decrease potentially unnecessary lab testing should consider implementing a bundle, including a prompt at a uniform and structured point during the hospitalization of patients who are expected to be discharged within 24 to 48 hours, clinician education, an audit, and feedback.

Disclosure

All authors report no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. PubMed

3. Dunn AS, Reyna, M, Radbill B, et al. The impact of bedside interdisciplinary rounds on length of stay and complications. J Hosp Med. 2017;3:137-142. PubMed

4. Iturrate E, Jubelt L, Volpicelli F, Hochman K. Optimize Your Electronic Medical Record to Increase Value: Reducing Laboratory Overutilization. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):215-220. PubMed

5. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a Resident-Led Project to Decrease Phlebotomy Rates in the Hospital: Think Twice, Stick Once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. PubMed

6. Corson AH, Fan VS, White T, et al. A Multifaceted Hospitalist Quality Improvement Intervention: Decreased Frequency of Common Labs. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):390-395. PubMed

7. Bhamidipati VS, Elliott DJ, Justice EM, Belleh E, Sonnad SS, Robinson EJ. Structure and outcomes of interdisciplinary rounds in hospitalized medicine patients: A systematic review and suggested taxonomy. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):513-523. PubMed

8. O’Leary, KJ, Sehgal NL, Terrell G, Williams MV, High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future Project Team. Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: a review and practical recommendations for improvement. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(1):48-54. PubMed

1. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

2. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):520-524. PubMed

3. Dunn AS, Reyna, M, Radbill B, et al. The impact of bedside interdisciplinary rounds on length of stay and complications. J Hosp Med. 2017;3:137-142. PubMed

4. Iturrate E, Jubelt L, Volpicelli F, Hochman K. Optimize Your Electronic Medical Record to Increase Value: Reducing Laboratory Overutilization. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):215-220. PubMed

5. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a Resident-Led Project to Decrease Phlebotomy Rates in the Hospital: Think Twice, Stick Once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. PubMed

6. Corson AH, Fan VS, White T, et al. A Multifaceted Hospitalist Quality Improvement Intervention: Decreased Frequency of Common Labs. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):390-395. PubMed

7. Bhamidipati VS, Elliott DJ, Justice EM, Belleh E, Sonnad SS, Robinson EJ. Structure and outcomes of interdisciplinary rounds in hospitalized medicine patients: A systematic review and suggested taxonomy. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):513-523. PubMed

8. O’Leary, KJ, Sehgal NL, Terrell G, Williams MV, High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future Project Team. Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: a review and practical recommendations for improvement. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(1):48-54. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

The value of using ultrasound to rule out deep vein thrombosis in cases of cellulitis

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Because of overlapping clinical manifestations, clinicians often order ultrasound to rule out deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in cases of cellulitis. Ultrasound testing is performed for 16% to 73% of patients diagnosed with cellulitis. Although testing is common, the pooled incidence of DVT is low (3.1%). Few data elucidate which patients with cellulitis are more likely to have concurrent DVT and require further testing. The Wells clinical prediction rule with

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 3-day-old cut on his anterior right shin. Associated redness, warmth, pain, and swelling had progressed. The patient had no history of prior DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE). His temperature was 38.5°C, and his white blood cell count of 18,000. On review of systems, he denied shortness of breath and chest pain. He was diagnosed with cellulitis and administered intravenous fluids and cefazolin. The clinician wondered whether to perform lower extremity ultrasound to rule out concurrent DVT.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK ULTRASOUND IS HELPFUL IN RULING OUT DVT IN CELLULITIS

Lower extremity cellulitis, a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, is characterized by unilateral erythema, pain, warmth, and swelling. The infection usually follows a skin breach that allows bacteria to enter. DVT may present similarly, and symptoms can include mild leukocytosis and elevated temperature. Because of the clinical similarities, clinicians often order compression ultrasound of the extremity to rule out concurrent DVT in cellulitis. Further impetus for testing stems from fear of the potential complications of untreated DVT, including post-thrombotic syndrome, chronic venous insufficiency, and venous ulceration. A subsequent PE can be fatal, or can cause significant morbidity, including chronic VTE with associated pulmonary hypertension. An estimated quarter of all PEs present as sudden death.1

WHY ULTRASOUND IS NOT HELPFUL IN THIS SETTING

Studies have shown that ultrasound is ordered for 16% to 73% of patients with a cellulitis diagnosis.2,3 Although testing is commonly performed, a meta-analysis of 9 studies of cellulitis patients who underwent ultrasound testing for concurrent DVT revealed a low pooled incidence of total DVT (3.1%) and proximal DVT (2.1%).4 Maze et al.2 retrospectively reviewed 1515 cellulitis cases (identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes) at a single center in New Zealand over 3 years. Of the 1515 patients, 240 (16%) had ultrasound performed, and only 3 (1.3%) were found to have DVT. Two of the 3 had active malignancy, and the third had injected battery acid into the area. In a 5-year retrospective cohort study at a Veterans Administration hospital in Connecticut, Gunderson and Chang3 reviewed the cases of 183 patients with cellulitis and found ultrasound testing commonly performed (73% of cases) to assess for DVT. Only 1 patient (<1%) was diagnosed with new DVT in the ipsilateral leg, and acute DVT was diagnosed in the contralateral leg of 2 other patients. Overall, these studies indicate the incidence of concurrent DVT in cellulitis is low, regardless of the frequency of ultrasound testing.

Although the cost of a single ultrasound test is not prohibitive, annual total costs hospital-wide and nationally are large. In the United States, the charge for a unilateral duplex ultrasound of the extremity ranges from $260 to $1300, and there is an additional charge for interpretation by a radiologist.5 In a retrospective study spanning 3.5 years and involving 2 community hospitals in Michigan, an estimated $290,000 was spent on ultrasound tests defined as unnecessary for patients with cellulitis.6 A limitation of the study was defining a test as unnecessary based on its result being negative.

DOES WELLS SCORE WITH D-DIMER HELP DEFINE A LOW-RISK POPULATION?

The Wells clinical prediction rule is commonly used to assess the pretest probability of DVT in patients presenting with unilateral leg symptoms. The Wells score is often combined with

WHEN MIGHT ULTRASOUND

Investigators have described possible DVT risk factors in patients with cellulitis, but definitive associations are lacking because of the insufficient number of patients studied.8,9 The most consistently identified DVT risk factor is history of previous thromboembolism. In a retrospective analysis of patients with cellulitis, Afzal et al.6 found that, of the 66.8% who underwent ultrasound testing, 5.5% were identified as having concurrent DVT. The authors performed univariate analyses of 15 potential risk factors, including active malignancy, oral contraceptive pill use, recent hospitalization, and surgery. A higher incidence of DVT was found for patients with history of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 5.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3-13.7), calf swelling (OR, 4.5; 95% CI, 1.3-15.8), CVA (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.2-10.1), or hypertension (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 0.98-12.2). Given the wide confidence intervals, paucity of studies, and lack of definitive data in the setting of cellulitis, clinicians may want to consider the risk factors established in larger trials in other settings, including known immobility (OR, <2); thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis (OR, 2-9); and trauma and recent surgery (OR, >10).10

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

As the incidence of concurrent VTE in patients with cellulitis is low, the essential step is to make a clear diagnosis of cellulitis based on its established signs and symptoms. A 2-center trial of 145 patients found that cellulitis was diagnosed accurately by general medicine and emergency medicine physicians 72% of the time, with evaluation by dermatologists and infectious disease specialists used as the gold standard. Only 5% of the misdiagnosed patients were diagnosed with DVT; stasis dermatitis was the most common alternative diagnosis. Taking a thorough history may elicit risk factors consistent with cellulitis, such as a recent injury with a break in the skin. On examination, cellulitis should be suspected for patients with fever and localized pain, redness, swelling, and warmth—the cardinal signs of dolor, rubor, tumor, and calor. An injury or entry site and leukocytosis also support the diagnosis of cellulitis. Distinct margins of erythema on the skin are highly suspicious for erysipelas.11 Other physical findings (eg, laceration, purulent drainage, lymphangitic spread, fluctuating mass) also are consistent with a diagnosis of cellulitis.

The patient’s history is also essential in determining whether any DVT risk factors are present. Past medical history of VTE or CVA, or recent history of surgery, immobility, or trauma, should alert the clinician to the possibility of DVT. Family history of VTE increases the likelihood of DVT. Acute shortness of breath or chest pain in the setting of concerning lower extremity findings for DVT should raise concern for DVT and concurrent PE.

If the classic features of cellulitis are present, empiric antibiotics should be initiated. Routine ultrasound testing for all patients with cellulitis is of low value. However, as the incidence of DVT in this population is not negligible, those with VTE risk factors should be targeted for testing. Studies in the setting of cellulitis provide little guidance regarding specific risk factors that can be used to determine who should undergo further testing. Given this limitation, we suggest that clinicians incorporate into their decision making the well-established VTE risk factors identified for large populations studied in other settings, such as the postoperative period. Specifically, clinicians should consider ultrasound testing for patients with cellulitis and prior history of VTE; immobility; thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis; or trauma and recent surgery.10-12 Ultrasound should also be considered for patients with cellulitis that does not improve and for patients whose localized symptoms worsen despite use of antibiotics.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Do not routinely perform ultrasound to rule out concurrent DVT in cases of cellulitis.

Consider compression ultrasound if there is a history of VTE; immobility; thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis; or trauma and recent surgery. Also consider it for patients who do not respond to antibiotics.

- In cases of cellulitis, avoid use of the Wells score alone or with

D -dimer testing, as it likely overestimates the DVT risk.

CONCLUSION

The current evidence shows that, for most patients with cellulitis, routine ultrasound testing for DVT is unnecessary. Ultrasound should be considered for patients with potent VTE risk factors. If symptoms do not improve, or if they worsen despite use of antibiotics, clinicians should be alert to potential anchoring bias and consider DVT. The Wells clinical prediction rule overestimates the incidence of DVT in cellulitis and has little value in this setting.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

1. Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21(1):23-29. PubMed

2. Maze MJ, Pithie A, Dawes T, Chambers ST. An audit of venous duplex ultrasonography in patients with lower limb cellulitis. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1329):53-56. PubMed

3. Gunderson CG, Chang JJ. Overuse of compression ultrasound for patients with lower extremity cellulitis. Thromb Res. 2014;134(4):846-850. PubMed

4. Gunderson CG, Chang JJ. Risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients with cellulitis and erysipelas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2013;132(3):336-340. PubMed

5. Extremity ultrasound (nonvascular) cost and procedure information. http://www.newchoicehealth.com/procedures/extremity-ultrasound-nonvascular. Accessed February 15, 2016.

6. Afzal MZ, Saleh MM, Razvi S, Hashmi H, Lampen R. Utility of lower extremity Doppler in patients with lower extremity cellulitis: a need to change the practice? South Med J. 2015;108(7):439-444. PubMed

7. Goodacre S, Sutton AJ, Sampson FC. Meta-analysis: the value of clinical assessment in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):129-139. PubMed

8. Maze MJ, Skea S, Pithie A, Metcalf S, Pearson JF, Chambers ST. Prevalence of concurrent deep vein thrombosis in patients with lower limb cellulitis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:141. PubMed

9. Bersier D, Bounameaux H. Cellulitis and deep vein thrombosis: a controversial association. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(4):867-868. PubMed

10. Anderson FA Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 suppl 1):I9-I16. PubMed

11. Rabuka CE, Azoulay LY, Kahn SR. Predictors of a positive duplex scan in patients with a clinical presentation compatible with deep vein thrombosis or cellulitis. Can J Infect Dis. 2003;14(4):210-214. PubMed

12. Samama MM. An epidemiologic study of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in medical outpatients: the Sirius Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(22):3415-3420. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Because of overlapping clinical manifestations, clinicians often order ultrasound to rule out deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in cases of cellulitis. Ultrasound testing is performed for 16% to 73% of patients diagnosed with cellulitis. Although testing is common, the pooled incidence of DVT is low (3.1%). Few data elucidate which patients with cellulitis are more likely to have concurrent DVT and require further testing. The Wells clinical prediction rule with

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 3-day-old cut on his anterior right shin. Associated redness, warmth, pain, and swelling had progressed. The patient had no history of prior DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE). His temperature was 38.5°C, and his white blood cell count of 18,000. On review of systems, he denied shortness of breath and chest pain. He was diagnosed with cellulitis and administered intravenous fluids and cefazolin. The clinician wondered whether to perform lower extremity ultrasound to rule out concurrent DVT.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK ULTRASOUND IS HELPFUL IN RULING OUT DVT IN CELLULITIS

Lower extremity cellulitis, a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, is characterized by unilateral erythema, pain, warmth, and swelling. The infection usually follows a skin breach that allows bacteria to enter. DVT may present similarly, and symptoms can include mild leukocytosis and elevated temperature. Because of the clinical similarities, clinicians often order compression ultrasound of the extremity to rule out concurrent DVT in cellulitis. Further impetus for testing stems from fear of the potential complications of untreated DVT, including post-thrombotic syndrome, chronic venous insufficiency, and venous ulceration. A subsequent PE can be fatal, or can cause significant morbidity, including chronic VTE with associated pulmonary hypertension. An estimated quarter of all PEs present as sudden death.1

WHY ULTRASOUND IS NOT HELPFUL IN THIS SETTING

Studies have shown that ultrasound is ordered for 16% to 73% of patients with a cellulitis diagnosis.2,3 Although testing is commonly performed, a meta-analysis of 9 studies of cellulitis patients who underwent ultrasound testing for concurrent DVT revealed a low pooled incidence of total DVT (3.1%) and proximal DVT (2.1%).4 Maze et al.2 retrospectively reviewed 1515 cellulitis cases (identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes) at a single center in New Zealand over 3 years. Of the 1515 patients, 240 (16%) had ultrasound performed, and only 3 (1.3%) were found to have DVT. Two of the 3 had active malignancy, and the third had injected battery acid into the area. In a 5-year retrospective cohort study at a Veterans Administration hospital in Connecticut, Gunderson and Chang3 reviewed the cases of 183 patients with cellulitis and found ultrasound testing commonly performed (73% of cases) to assess for DVT. Only 1 patient (<1%) was diagnosed with new DVT in the ipsilateral leg, and acute DVT was diagnosed in the contralateral leg of 2 other patients. Overall, these studies indicate the incidence of concurrent DVT in cellulitis is low, regardless of the frequency of ultrasound testing.

Although the cost of a single ultrasound test is not prohibitive, annual total costs hospital-wide and nationally are large. In the United States, the charge for a unilateral duplex ultrasound of the extremity ranges from $260 to $1300, and there is an additional charge for interpretation by a radiologist.5 In a retrospective study spanning 3.5 years and involving 2 community hospitals in Michigan, an estimated $290,000 was spent on ultrasound tests defined as unnecessary for patients with cellulitis.6 A limitation of the study was defining a test as unnecessary based on its result being negative.

DOES WELLS SCORE WITH D-DIMER HELP DEFINE A LOW-RISK POPULATION?

The Wells clinical prediction rule is commonly used to assess the pretest probability of DVT in patients presenting with unilateral leg symptoms. The Wells score is often combined with

WHEN MIGHT ULTRASOUND

Investigators have described possible DVT risk factors in patients with cellulitis, but definitive associations are lacking because of the insufficient number of patients studied.8,9 The most consistently identified DVT risk factor is history of previous thromboembolism. In a retrospective analysis of patients with cellulitis, Afzal et al.6 found that, of the 66.8% who underwent ultrasound testing, 5.5% were identified as having concurrent DVT. The authors performed univariate analyses of 15 potential risk factors, including active malignancy, oral contraceptive pill use, recent hospitalization, and surgery. A higher incidence of DVT was found for patients with history of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 5.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3-13.7), calf swelling (OR, 4.5; 95% CI, 1.3-15.8), CVA (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.2-10.1), or hypertension (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 0.98-12.2). Given the wide confidence intervals, paucity of studies, and lack of definitive data in the setting of cellulitis, clinicians may want to consider the risk factors established in larger trials in other settings, including known immobility (OR, <2); thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis (OR, 2-9); and trauma and recent surgery (OR, >10).10

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

As the incidence of concurrent VTE in patients with cellulitis is low, the essential step is to make a clear diagnosis of cellulitis based on its established signs and symptoms. A 2-center trial of 145 patients found that cellulitis was diagnosed accurately by general medicine and emergency medicine physicians 72% of the time, with evaluation by dermatologists and infectious disease specialists used as the gold standard. Only 5% of the misdiagnosed patients were diagnosed with DVT; stasis dermatitis was the most common alternative diagnosis. Taking a thorough history may elicit risk factors consistent with cellulitis, such as a recent injury with a break in the skin. On examination, cellulitis should be suspected for patients with fever and localized pain, redness, swelling, and warmth—the cardinal signs of dolor, rubor, tumor, and calor. An injury or entry site and leukocytosis also support the diagnosis of cellulitis. Distinct margins of erythema on the skin are highly suspicious for erysipelas.11 Other physical findings (eg, laceration, purulent drainage, lymphangitic spread, fluctuating mass) also are consistent with a diagnosis of cellulitis.

The patient’s history is also essential in determining whether any DVT risk factors are present. Past medical history of VTE or CVA, or recent history of surgery, immobility, or trauma, should alert the clinician to the possibility of DVT. Family history of VTE increases the likelihood of DVT. Acute shortness of breath or chest pain in the setting of concerning lower extremity findings for DVT should raise concern for DVT and concurrent PE.

If the classic features of cellulitis are present, empiric antibiotics should be initiated. Routine ultrasound testing for all patients with cellulitis is of low value. However, as the incidence of DVT in this population is not negligible, those with VTE risk factors should be targeted for testing. Studies in the setting of cellulitis provide little guidance regarding specific risk factors that can be used to determine who should undergo further testing. Given this limitation, we suggest that clinicians incorporate into their decision making the well-established VTE risk factors identified for large populations studied in other settings, such as the postoperative period. Specifically, clinicians should consider ultrasound testing for patients with cellulitis and prior history of VTE; immobility; thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis; or trauma and recent surgery.10-12 Ultrasound should also be considered for patients with cellulitis that does not improve and for patients whose localized symptoms worsen despite use of antibiotics.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Do not routinely perform ultrasound to rule out concurrent DVT in cases of cellulitis.

Consider compression ultrasound if there is a history of VTE; immobility; thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis; or trauma and recent surgery. Also consider it for patients who do not respond to antibiotics.

- In cases of cellulitis, avoid use of the Wells score alone or with

D -dimer testing, as it likely overestimates the DVT risk.

CONCLUSION

The current evidence shows that, for most patients with cellulitis, routine ultrasound testing for DVT is unnecessary. Ultrasound should be considered for patients with potent VTE risk factors. If symptoms do not improve, or if they worsen despite use of antibiotics, clinicians should be alert to potential anchoring bias and consider DVT. The Wells clinical prediction rule overestimates the incidence of DVT in cellulitis and has little value in this setting.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Because of overlapping clinical manifestations, clinicians often order ultrasound to rule out deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in cases of cellulitis. Ultrasound testing is performed for 16% to 73% of patients diagnosed with cellulitis. Although testing is common, the pooled incidence of DVT is low (3.1%). Few data elucidate which patients with cellulitis are more likely to have concurrent DVT and require further testing. The Wells clinical prediction rule with

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 3-day-old cut on his anterior right shin. Associated redness, warmth, pain, and swelling had progressed. The patient had no history of prior DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE). His temperature was 38.5°C, and his white blood cell count of 18,000. On review of systems, he denied shortness of breath and chest pain. He was diagnosed with cellulitis and administered intravenous fluids and cefazolin. The clinician wondered whether to perform lower extremity ultrasound to rule out concurrent DVT.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK ULTRASOUND IS HELPFUL IN RULING OUT DVT IN CELLULITIS

Lower extremity cellulitis, a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, is characterized by unilateral erythema, pain, warmth, and swelling. The infection usually follows a skin breach that allows bacteria to enter. DVT may present similarly, and symptoms can include mild leukocytosis and elevated temperature. Because of the clinical similarities, clinicians often order compression ultrasound of the extremity to rule out concurrent DVT in cellulitis. Further impetus for testing stems from fear of the potential complications of untreated DVT, including post-thrombotic syndrome, chronic venous insufficiency, and venous ulceration. A subsequent PE can be fatal, or can cause significant morbidity, including chronic VTE with associated pulmonary hypertension. An estimated quarter of all PEs present as sudden death.1

WHY ULTRASOUND IS NOT HELPFUL IN THIS SETTING

Studies have shown that ultrasound is ordered for 16% to 73% of patients with a cellulitis diagnosis.2,3 Although testing is commonly performed, a meta-analysis of 9 studies of cellulitis patients who underwent ultrasound testing for concurrent DVT revealed a low pooled incidence of total DVT (3.1%) and proximal DVT (2.1%).4 Maze et al.2 retrospectively reviewed 1515 cellulitis cases (identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes) at a single center in New Zealand over 3 years. Of the 1515 patients, 240 (16%) had ultrasound performed, and only 3 (1.3%) were found to have DVT. Two of the 3 had active malignancy, and the third had injected battery acid into the area. In a 5-year retrospective cohort study at a Veterans Administration hospital in Connecticut, Gunderson and Chang3 reviewed the cases of 183 patients with cellulitis and found ultrasound testing commonly performed (73% of cases) to assess for DVT. Only 1 patient (<1%) was diagnosed with new DVT in the ipsilateral leg, and acute DVT was diagnosed in the contralateral leg of 2 other patients. Overall, these studies indicate the incidence of concurrent DVT in cellulitis is low, regardless of the frequency of ultrasound testing.

Although the cost of a single ultrasound test is not prohibitive, annual total costs hospital-wide and nationally are large. In the United States, the charge for a unilateral duplex ultrasound of the extremity ranges from $260 to $1300, and there is an additional charge for interpretation by a radiologist.5 In a retrospective study spanning 3.5 years and involving 2 community hospitals in Michigan, an estimated $290,000 was spent on ultrasound tests defined as unnecessary for patients with cellulitis.6 A limitation of the study was defining a test as unnecessary based on its result being negative.

DOES WELLS SCORE WITH D-DIMER HELP DEFINE A LOW-RISK POPULATION?

The Wells clinical prediction rule is commonly used to assess the pretest probability of DVT in patients presenting with unilateral leg symptoms. The Wells score is often combined with

WHEN MIGHT ULTRASOUND

Investigators have described possible DVT risk factors in patients with cellulitis, but definitive associations are lacking because of the insufficient number of patients studied.8,9 The most consistently identified DVT risk factor is history of previous thromboembolism. In a retrospective analysis of patients with cellulitis, Afzal et al.6 found that, of the 66.8% who underwent ultrasound testing, 5.5% were identified as having concurrent DVT. The authors performed univariate analyses of 15 potential risk factors, including active malignancy, oral contraceptive pill use, recent hospitalization, and surgery. A higher incidence of DVT was found for patients with history of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 5.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3-13.7), calf swelling (OR, 4.5; 95% CI, 1.3-15.8), CVA (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.2-10.1), or hypertension (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 0.98-12.2). Given the wide confidence intervals, paucity of studies, and lack of definitive data in the setting of cellulitis, clinicians may want to consider the risk factors established in larger trials in other settings, including known immobility (OR, <2); thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis (OR, 2-9); and trauma and recent surgery (OR, >10).10

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

As the incidence of concurrent VTE in patients with cellulitis is low, the essential step is to make a clear diagnosis of cellulitis based on its established signs and symptoms. A 2-center trial of 145 patients found that cellulitis was diagnosed accurately by general medicine and emergency medicine physicians 72% of the time, with evaluation by dermatologists and infectious disease specialists used as the gold standard. Only 5% of the misdiagnosed patients were diagnosed with DVT; stasis dermatitis was the most common alternative diagnosis. Taking a thorough history may elicit risk factors consistent with cellulitis, such as a recent injury with a break in the skin. On examination, cellulitis should be suspected for patients with fever and localized pain, redness, swelling, and warmth—the cardinal signs of dolor, rubor, tumor, and calor. An injury or entry site and leukocytosis also support the diagnosis of cellulitis. Distinct margins of erythema on the skin are highly suspicious for erysipelas.11 Other physical findings (eg, laceration, purulent drainage, lymphangitic spread, fluctuating mass) also are consistent with a diagnosis of cellulitis.

The patient’s history is also essential in determining whether any DVT risk factors are present. Past medical history of VTE or CVA, or recent history of surgery, immobility, or trauma, should alert the clinician to the possibility of DVT. Family history of VTE increases the likelihood of DVT. Acute shortness of breath or chest pain in the setting of concerning lower extremity findings for DVT should raise concern for DVT and concurrent PE.

If the classic features of cellulitis are present, empiric antibiotics should be initiated. Routine ultrasound testing for all patients with cellulitis is of low value. However, as the incidence of DVT in this population is not negligible, those with VTE risk factors should be targeted for testing. Studies in the setting of cellulitis provide little guidance regarding specific risk factors that can be used to determine who should undergo further testing. Given this limitation, we suggest that clinicians incorporate into their decision making the well-established VTE risk factors identified for large populations studied in other settings, such as the postoperative period. Specifically, clinicians should consider ultrasound testing for patients with cellulitis and prior history of VTE; immobility; thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis; or trauma and recent surgery.10-12 Ultrasound should also be considered for patients with cellulitis that does not improve and for patients whose localized symptoms worsen despite use of antibiotics.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Do not routinely perform ultrasound to rule out concurrent DVT in cases of cellulitis.

Consider compression ultrasound if there is a history of VTE; immobility; thrombophilia, CHF, and CVA with hemiparesis; or trauma and recent surgery. Also consider it for patients who do not respond to antibiotics.

- In cases of cellulitis, avoid use of the Wells score alone or with

D -dimer testing, as it likely overestimates the DVT risk.

CONCLUSION

The current evidence shows that, for most patients with cellulitis, routine ultrasound testing for DVT is unnecessary. Ultrasound should be considered for patients with potent VTE risk factors. If symptoms do not improve, or if they worsen despite use of antibiotics, clinicians should be alert to potential anchoring bias and consider DVT. The Wells clinical prediction rule overestimates the incidence of DVT in cellulitis and has little value in this setting.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

1. Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21(1):23-29. PubMed

2. Maze MJ, Pithie A, Dawes T, Chambers ST. An audit of venous duplex ultrasonography in patients with lower limb cellulitis. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1329):53-56. PubMed

3. Gunderson CG, Chang JJ. Overuse of compression ultrasound for patients with lower extremity cellulitis. Thromb Res. 2014;134(4):846-850. PubMed

4. Gunderson CG, Chang JJ. Risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients with cellulitis and erysipelas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2013;132(3):336-340. PubMed

5. Extremity ultrasound (nonvascular) cost and procedure information. http://www.newchoicehealth.com/procedures/extremity-ultrasound-nonvascular. Accessed February 15, 2016.

6. Afzal MZ, Saleh MM, Razvi S, Hashmi H, Lampen R. Utility of lower extremity Doppler in patients with lower extremity cellulitis: a need to change the practice? South Med J. 2015;108(7):439-444. PubMed

7. Goodacre S, Sutton AJ, Sampson FC. Meta-analysis: the value of clinical assessment in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):129-139. PubMed

8. Maze MJ, Skea S, Pithie A, Metcalf S, Pearson JF, Chambers ST. Prevalence of concurrent deep vein thrombosis in patients with lower limb cellulitis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:141. PubMed

9. Bersier D, Bounameaux H. Cellulitis and deep vein thrombosis: a controversial association. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(4):867-868. PubMed

10. Anderson FA Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 suppl 1):I9-I16. PubMed

11. Rabuka CE, Azoulay LY, Kahn SR. Predictors of a positive duplex scan in patients with a clinical presentation compatible with deep vein thrombosis or cellulitis. Can J Infect Dis. 2003;14(4):210-214. PubMed

12. Samama MM. An epidemiologic study of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in medical outpatients: the Sirius Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(22):3415-3420. PubMed

1. Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21(1):23-29. PubMed

2. Maze MJ, Pithie A, Dawes T, Chambers ST. An audit of venous duplex ultrasonography in patients with lower limb cellulitis. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1329):53-56. PubMed

3. Gunderson CG, Chang JJ. Overuse of compression ultrasound for patients with lower extremity cellulitis. Thromb Res. 2014;134(4):846-850. PubMed

4. Gunderson CG, Chang JJ. Risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients with cellulitis and erysipelas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2013;132(3):336-340. PubMed

5. Extremity ultrasound (nonvascular) cost and procedure information. http://www.newchoicehealth.com/procedures/extremity-ultrasound-nonvascular. Accessed February 15, 2016.

6. Afzal MZ, Saleh MM, Razvi S, Hashmi H, Lampen R. Utility of lower extremity Doppler in patients with lower extremity cellulitis: a need to change the practice? South Med J. 2015;108(7):439-444. PubMed

7. Goodacre S, Sutton AJ, Sampson FC. Meta-analysis: the value of clinical assessment in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):129-139. PubMed

8. Maze MJ, Skea S, Pithie A, Metcalf S, Pearson JF, Chambers ST. Prevalence of concurrent deep vein thrombosis in patients with lower limb cellulitis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:141. PubMed

9. Bersier D, Bounameaux H. Cellulitis and deep vein thrombosis: a controversial association. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(4):867-868. PubMed

10. Anderson FA Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 suppl 1):I9-I16. PubMed

11. Rabuka CE, Azoulay LY, Kahn SR. Predictors of a positive duplex scan in patients with a clinical presentation compatible with deep vein thrombosis or cellulitis. Can J Infect Dis. 2003;14(4):210-214. PubMed

12. Samama MM. An epidemiologic study of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in medical outpatients: the Sirius Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(22):3415-3420. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Are we causing anemia by ordering unnecessary blood tests?

A 68-year-old woman is admitted for community-acquired pneumonia. She receives antibiotics, and her condition begins to improve after 2 days. She has her blood drawn daily throughout her admission.

On hospital day 3, she complains of fatigue, and on day 4, laboratory results show that her hemoglobin and hematocrit values have fallen. To make sure this result is not spurious, her blood is drawn again to repeat the test. On day 5, her hemoglobin level has dropped to 7.0 g/dL, which is 2 g/dL lower than at admission, and she receives a transfusion.

On day 7, her hemoglobin level is stable at 8.5 g/dL, and her physicians decide to discharge her. The morning of her discharge, as a nurse is about to draw her blood, the patient asks, “Are all these blood tests really necessary?”

DO WE DRAW TOO MUCH BLOOD?

This case portrays a common occurrence. Significant amounts of blood are drawn from patients, especially in critical care. Clinical uncertainty drives most laboratory testing ordered by physicians. Too often, however, these tests lead to more testing and interventions, without a clear benefit to the patient.1

When blood testing leads to more testing, a patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit can fall. Symptomatic iatrogenic anemia is associated with significant morbidity for patients with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease.

We draw much larger volumes of blood than most testing guidelines say are necessary. One author2 has noted that 50 to 60 mL of blood is removed for each set of tests, owing to the size of collection tubes, multiple reagents needed for each test, and the possibility that tests may need to be rerun. Yet about 3 mL of blood is sufficient to perform most laboratory tests even if the test needs to be rerun.2

CAN BLOOD DRAWS CAUSE ANEMIA?

A relationship between the volume of blood drawn and iatrogenic anemia was first described in 2005, when Thavendiranathan et al3 found that in adult patients on general medicine floors, the volume of blood drawn strongly predicted decreased hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. For every 100 mL of blood drawn, hemoglobin levels fell by an average of 0.7 g/dL, and 13.9% of the patients in the study had iron studies and fecal occult blood tests performed to investigate anemia.

Kurniali et al4 reported that during an average admission, 65% of patients experienced a drop in hemoglobin of 1.0 g/dL or more, and 49% developed anemia.

Salisbury et al,5 in 2011, studied 17,676 patients with acute myocardial infarction across 57 centers and found a correlation between the volume of blood taken and the development of anemia. On average, for every 50 mL of blood drawn, the risk of moderate to severe iatrogenic anemia increased by 18%. They also found significant variation in blood loss from testing in patients who developed moderate or severe anemia. The authors believed this indicated that moderate to severe anemia was more frequent at centers with higher than average diagnostic blood loss.5

This relationship has also been described in patients in intensive care, where it contributes to anemia of chronic disease. While anemia of critical illness is multifactorial, phlebotomy contributes to anemia in both short- and long-term stays in the intensive care unit.6

CHOOSING WISELY GUIDELINES

The Choosing Wisely initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation collects recommendations by a number of medical specialty societies to reduce overuse of healthcare resources.7 The Critical Care Societies Collaborative recommends ordering diagnostic tests only when they answer specific clinical questions rather than routinely. The Society of Hospital Medicine also recommends against repeat complete blood cell count and blood chemistry testing because it may contribute to anemia, which is of particular concern in patients with cardiorespiratory disease.

POSSIBLE HARM

The Critical Care Societies Collaborative, in its Choosing Wisely Guidelines, specifically cites anemia as a potential harm of unnecessary phlebotomy, noting it may result in transfusion, with its associated risks and costs. In addition, aggressive investigation of incidental and nonpathologic results of routine studies is wasteful and exposes the patient to additional risks.

REDUCING PHLEBOTOMY DECREASES IATROGENIC ANEMIA

Since the relationship between excessive phlebotomy and iatrogenic anemia was described, hospitals have attempted to address the problem.

In 2011, Stuebing and Miner8 described an intervention in which the house staff and attending physicians on non-intensive care surgical services were given weekly reports of the cost of the laboratory services for the previous week. They found that simply making providers aware of the cost of their tests reduced the number of tests ordered and resulted in significant hospital savings.

Another strategy is to use pediatric collection tubes in adult patients. A 2008 study in which all blood samples were drawn using pediatric tubes reduced the blood volume removed per patient by almost 75% in inpatient and critical care patients, without the need for repeat blood draws.9 However, Kurniali et al found that the use of pediatric collection tubes did not significantly change hemoglobin fluctuations throughout patient hospital stays.4

Corson et al10 in 2015 described an intervention involving detailing, auditing, and giving feedback regarding the frequency of laboratory tests commonly ordered by a group of hospitalists. The intervention resulted in a modest reduction in the number of common laboratory tests ordered per patient day and in hospital costs, without any changes in the length of hospital stay, mortality rate, or readmission rate.10

THE CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

As a general principle, diagnostic testing should be done to answer specific diagnostic questions and to guide management. Ordering of diagnostic tests should be decided on a day-to-day basis rather than scheduled automatically or done reflexively. In the case of blood draws, the volume of blood drawn is significantly increased by unnecessary testing, resulting in higher rates of hospital-acquired anemia.

- Ezzie ME, Aberegg SK, O’Brien JM Jr. Laboratory testing in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin 2007; 23:435–465.

- Stefanini M. Iatrogenic anemia (can it be prevented?). J Thromb Haemost 2014; 12:1591.

- Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK. Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20:520–524.

- Kurniali PC, Curry S, Brennan KW, et al. A retrospective study investigating the incidence and predisposing factors of hospital-acquired anemia. Anemia 2014; 2014:634582.

- Salisbury AC, Reid KJ, Alexander KP, et al. Diagnostic blood loss from phlebotomy and hospital-acquired anemia during acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1646–1653.

- Walsh TS, Lee RJ, Maciver CR, et al. Anemia during and at discharge from intensive care: the impact of restrictive blood transfusion practice. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32:100–109.

- American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. www.abimfoundation.org/Initiatives/Choosing-Wisely.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2016.

- Stuebing EA, Miner TJ. Surgical vampires and rising health care expenditure: reducing the cost of daily phlebotomy. Arch Surg 2011; 146:524–527.

- Sanchez-Giron F, Alvarez-Mora F. Reduction of blood loss from laboratory testing in hospitalized adult patients using small-volume (pediatric) tubes. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008; 132:1916–1919.

- Corson AH, Fan VS, White T, et al. A multifaceted hospitalist quality improvement intervention: decreased frequency of common labs. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:390–395.

A 68-year-old woman is admitted for community-acquired pneumonia. She receives antibiotics, and her condition begins to improve after 2 days. She has her blood drawn daily throughout her admission.

On hospital day 3, she complains of fatigue, and on day 4, laboratory results show that her hemoglobin and hematocrit values have fallen. To make sure this result is not spurious, her blood is drawn again to repeat the test. On day 5, her hemoglobin level has dropped to 7.0 g/dL, which is 2 g/dL lower than at admission, and she receives a transfusion.

On day 7, her hemoglobin level is stable at 8.5 g/dL, and her physicians decide to discharge her. The morning of her discharge, as a nurse is about to draw her blood, the patient asks, “Are all these blood tests really necessary?”

DO WE DRAW TOO MUCH BLOOD?

This case portrays a common occurrence. Significant amounts of blood are drawn from patients, especially in critical care. Clinical uncertainty drives most laboratory testing ordered by physicians. Too often, however, these tests lead to more testing and interventions, without a clear benefit to the patient.1

When blood testing leads to more testing, a patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit can fall. Symptomatic iatrogenic anemia is associated with significant morbidity for patients with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease.

We draw much larger volumes of blood than most testing guidelines say are necessary. One author2 has noted that 50 to 60 mL of blood is removed for each set of tests, owing to the size of collection tubes, multiple reagents needed for each test, and the possibility that tests may need to be rerun. Yet about 3 mL of blood is sufficient to perform most laboratory tests even if the test needs to be rerun.2

CAN BLOOD DRAWS CAUSE ANEMIA?

A relationship between the volume of blood drawn and iatrogenic anemia was first described in 2005, when Thavendiranathan et al3 found that in adult patients on general medicine floors, the volume of blood drawn strongly predicted decreased hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. For every 100 mL of blood drawn, hemoglobin levels fell by an average of 0.7 g/dL, and 13.9% of the patients in the study had iron studies and fecal occult blood tests performed to investigate anemia.

Kurniali et al4 reported that during an average admission, 65% of patients experienced a drop in hemoglobin of 1.0 g/dL or more, and 49% developed anemia.