User login

Improving Anticoagulation Transitions

Anticoagulants are among the prescriptions with the highest risk of an adverse drug event (ADE) after discharge, and many of these events are preventable.[1, 2, 3] In recognition of the high risk for adverse events, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Map details several key features of a safe anticoagulation management program, including the recommendation during the transition period that clinicians ensure proper lab monitoring and establish capacity for follow‐up testing.[4]

Despite the potential for harm, most hospitals do not have a structured process for the transmission of vital information related to warfarin management from the inpatient to the ambulatory setting. Our aim was to develop a concise report containing the essential information regarding the patient's anticoagulation regimen, the Safe Transitions Anticoagulation Report (STAR), and a process to ensure the report can be readily accessed and utilized by ambulatory clinicians.

METHODS

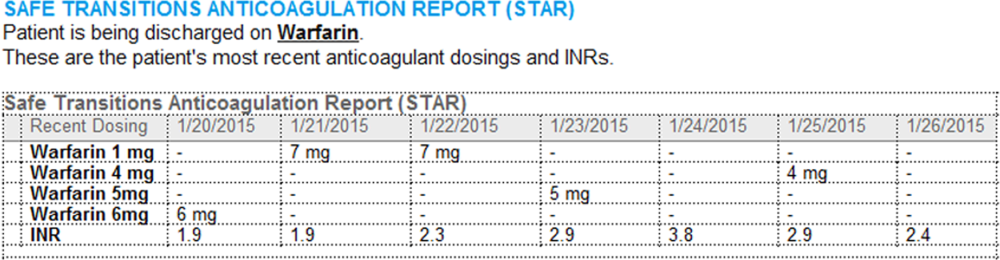

We assembled an interdisciplinary team to develop a new report and workflow to ensure that information on inpatient warfarin management was transmitted to outpatient providers in a reliable and structured manner. Explicit goals were to maximize use of the electronic medical record (EMR) to autopopulate aspects of the new report and create a process that worked seamlessly into the workflow. The final items were selected based on the risk of harm if not conveyed and feasibility of incorporation through the EMR:

- Warfarin doses: the 7 warfarin doses immediately prior to discharge

- International normalized ratio (INR) values: the 7 INR values immediately prior to discharge

- Bridging anticoagulation: the low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) prescribed as a bridging anticoagulant, if any

The STAR resides in both the discharge summary and the after visit summary (AVS) for patients discharged on warfarin. At our institution, the AVS contains a medication list, discharge instructions, and appointments, and is automatically produced through our EMR. Our institution utilizes the Epic EMR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) in the hospital, ambulatory clinics, and faculty practices.

A process was developed where a structured table is automatically created (Figure 1). A field was added to our EMR's discharge summary template asking whether the patient is being discharged on warfarin. Answering yes produces a second question asking whether the patient is also being discharged on bridging anticoagulation with LMWH. The STAR is not inserted into the discharge summary if the clinician completing the discharge summary deletes the anticoagulation question. The STAR is automatically created for patients discharged on warfarin and inserted into the AVS by the EMR regardless of whether the discharge summary has been completed. Patients are instructed by their nurse to bring their AVS to their follow‐up appointments.

The STAR project team utilized plan‐do‐study‐act cycles to test small changes and make revisions. The workflow was piloted on 2 medical/surgical units from January 2014 through March 2014, and revised based on feedback from clinicians and nursing staff. The STAR initiative was fully implemented across our institution in April 2014.

The study was evaluated by the institutional review board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and full review was waived.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were the timeliness of laboratory monitoring and quality of anticoagulation management for patients with an established relationship at 1 of the main outpatient practices in our system. Our institution has an anticoagulation clinic for patients followed at the general medicine clinic. We defined an established relationship as having been seen in the same practice on at least 2 occasions in the 12 months prior to admission. The primary outcomes were the percentage of patients who had an INR measurement done and the percentage who had a therapeutic INR value within 10 days after discharge. As the 10‐day period is arbitrary, we also assessed these outcomes for the 3‐, 7‐, and 30‐day periods after discharge. The therapeutic range was defined for all patients as an INR of 2.0 to 3.0, as this is the target range for the large majority of patients on warfarin in our system. Outcomes during the intervention period were compared to baseline values during the preintervention period. For patients with multiple admissions, the first admission during each period was included.

Ambulatory Physician Survey

We surveyed ambulatory care physicians at the main practices for our health system. The survey assessed how often the STAR was viewed and incorporated into decision making, whether the report improved workflow, and whether ambulatory providers perceived that the report increased patient safety. The survey was distributed at the 6‐month interval during the intervention phase. The survey was disseminated electronically on 3 occasions, and a paper version was distributed on 1 occasion to housestaff and general medicine faculty.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons for categorical data were performed using the 2 test. P values were based on 2‐tailed tests of significance, and a value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The STAR was embedded in the discharge summary for 1370 (78.6%) discharges during the intervention period. A total of 505 patients in the preintervention period and 292 patients in the intervention period were established patients at an affiliated practice and comprised the study population. Demographics and indications for warfarin for the preintervention and intervention groups are listed in the Table 1.

| Preintervention Group, N=505 | Intervention Group, N=292 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y | 66.7 | 68.0 | 0.29 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 236 (46.7) | 153 (52.4) | 0.12 |

| Discharged on bridging agent, n (%) | 90 (17.8) | 36 (12.3) | 0.04 |

| Average length of stay, d | 7.1 | 7.6 | 0.46 |

| Newly prescribed warfarin, n (%) | 147 (29.1) | 62 (21.2) | 0.01 |

| INR 2.03.0 range at discharge, n (%) | 187 (37.0) | 137 (46.9) | 0.02 |

| Warfarin indication, n (%)* | |||

| Venous thromboembolism | 93 (18.4) | 39 (13.4) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 204 (40.3) | 127 (43.5) | |

| Mechanical heart valve | 19 (3.8) | 17 (6.5) | |

| Prevention of thromboembolism | 142 (28.1) | 94 (32.2) | |

| Intracardiac thrombosis | 3 (0.5) | 6 (2.1) | |

| Thrombophilia | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Other | 19 (3.8) | 12 (4.1) | |

| No indication | 32 (6.3) | 1 (3.8) | |

The frequency of INR testing within 10 days of discharge was similar for the preintervention and intervention periods (41.4% and 47.6%, respectively, P=0.09). Similarly, the likelihood of having at least 1 therapeutic INR value within 10 days of discharge was not statistically different for the groups (17.0% and 21.2%, P=0.14). The pattern was similar for the 3‐, 7‐, and 30‐day periods; a higher percentage of the intervention group had INR testing and attained a therapeutic INR value, though for no time period did this reach statistical significance. This pattern was also found when limiting the analysis to patients discharged home rather than to a facility, patients on warfarin, prior to admission, and patients started on warfarin during the hospitalization.

A total of 87of 207 (42.0%) clinicians responded to the survey. Of respondents, 75% reported that they had seen 1 patient who had been discharged on warfarin since the STAR initiative had begun, 58% of whom reported having viewed the STAR. Most respondents who viewed the STAR found it to be helpful or very helpful in guiding warfarin management (67%), improving their workflow and efficiency (58%), and improving patient safety (77%). Approximately one‐third of respondents who had viewed the STAR (34%) reported that they selected a different dose than they would have chosen had the STAR not been available.

DISCUSSION

We developed a concise report that is seamlessly created and inserted into the discharge summary. Though the STAR was perceived as improving patient safety by ambulatory care providers, there was no impact on attaining a therapeutic INR after discharge. There are several possible explanations for a lack of benefit. Most notably, our intervention was comprised of a stand‐alone EMR‐based tool and focused on 1 component of the transitions process. Given the complexity of healthcare delivery and anticoagulant management, it is likely that broader interventions are required to improve clinical outcomes over the transition period. Potential targets of multifaceted approaches may include improving access to care, providing greater access to anticoagulation clinics, enhancing patient education, and promoting direct physician‐physician communication. Bundled interventions will likely need to include involvement of an interdisciplinary team, such as pharmacist involvement in the medication reconciliation process.

The transition period from the hospital to the outpatient setting has the potential to jeopardize patient safety if vital information is not reliably transmitted across venues.[5, 6, 7, 8] Forster and colleagues noted an 11% incidence of ADEs in the posthospitalization period, of which 60% were either preventable or ameliorable.[3] To decrease the risk to patient safety during the transitions period, the Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement by the Society of Hospital Medicine and other medical organizations called for incorporation of standard data transfer forms (templates and transmission protocols).[9] Despite the high risk and preventable nature of many of the events, few specific tools have been developed. As part of broader initiatives to improve the transitions process, the STAR may have the potential to be a means for health systems to improve the quality of the transition of care for patients on anticoagulants.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was performed at a single health system. It is unknown whether the EMR‐based report could be similarly employed at other systems. Second, our study was unable to assess clinical endpoints. Given the lack of effect on attaining a therapeutic INR, it is unlikely that downstream outcomes, such as thromboembolism, were impacted. Lastly, we were unable to examine whether our intervention improved the care of patients whose outpatient provider was external to our system.

The STAR is a concise tool developed to provide essential anticoagulant‐related information to ambulatory providers. Though the report was perceived as improving patient safety, our finding of a lack of impact on attaining a therapeutic INR after discharge suggests that the tool would need to be a component of a broader multifaceted intervention to impact clinical outcomes.

Disclosures

This project was funded by a grant from the Cardinal Health E3 Foundation. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , Medication errors: experience of the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) MEDMARX reporting system. J Clin Pharm. 2003;43:760–767.

- , , , , The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–167.

- , , , , Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Int Med. 2005;204:317–323.

- IHI Improvement Map. Available at: http://app.ihi.org/imap/tool/#Process=54aa289b‐16fd‐4a64‐8329‐3941dfc565d1. Accessed February 20 2015.

- , , , Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , , Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–841.

- Transitions of care in patients receiving oral anticoagulants: general principles, procedures, and impact of new oral anticoagulants. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28:54–65.

- Care transitions in anticoagulation management for patients with atrial fibrillation: an emphasis on safety. Oschner J. 2013;13:419–427.

- , , , et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:364–370.

Anticoagulants are among the prescriptions with the highest risk of an adverse drug event (ADE) after discharge, and many of these events are preventable.[1, 2, 3] In recognition of the high risk for adverse events, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Map details several key features of a safe anticoagulation management program, including the recommendation during the transition period that clinicians ensure proper lab monitoring and establish capacity for follow‐up testing.[4]

Despite the potential for harm, most hospitals do not have a structured process for the transmission of vital information related to warfarin management from the inpatient to the ambulatory setting. Our aim was to develop a concise report containing the essential information regarding the patient's anticoagulation regimen, the Safe Transitions Anticoagulation Report (STAR), and a process to ensure the report can be readily accessed and utilized by ambulatory clinicians.

METHODS

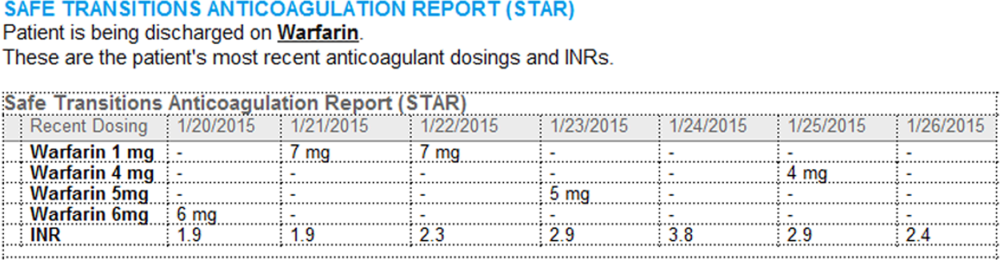

We assembled an interdisciplinary team to develop a new report and workflow to ensure that information on inpatient warfarin management was transmitted to outpatient providers in a reliable and structured manner. Explicit goals were to maximize use of the electronic medical record (EMR) to autopopulate aspects of the new report and create a process that worked seamlessly into the workflow. The final items were selected based on the risk of harm if not conveyed and feasibility of incorporation through the EMR:

- Warfarin doses: the 7 warfarin doses immediately prior to discharge

- International normalized ratio (INR) values: the 7 INR values immediately prior to discharge

- Bridging anticoagulation: the low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) prescribed as a bridging anticoagulant, if any

The STAR resides in both the discharge summary and the after visit summary (AVS) for patients discharged on warfarin. At our institution, the AVS contains a medication list, discharge instructions, and appointments, and is automatically produced through our EMR. Our institution utilizes the Epic EMR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) in the hospital, ambulatory clinics, and faculty practices.

A process was developed where a structured table is automatically created (Figure 1). A field was added to our EMR's discharge summary template asking whether the patient is being discharged on warfarin. Answering yes produces a second question asking whether the patient is also being discharged on bridging anticoagulation with LMWH. The STAR is not inserted into the discharge summary if the clinician completing the discharge summary deletes the anticoagulation question. The STAR is automatically created for patients discharged on warfarin and inserted into the AVS by the EMR regardless of whether the discharge summary has been completed. Patients are instructed by their nurse to bring their AVS to their follow‐up appointments.

The STAR project team utilized plan‐do‐study‐act cycles to test small changes and make revisions. The workflow was piloted on 2 medical/surgical units from January 2014 through March 2014, and revised based on feedback from clinicians and nursing staff. The STAR initiative was fully implemented across our institution in April 2014.

The study was evaluated by the institutional review board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and full review was waived.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were the timeliness of laboratory monitoring and quality of anticoagulation management for patients with an established relationship at 1 of the main outpatient practices in our system. Our institution has an anticoagulation clinic for patients followed at the general medicine clinic. We defined an established relationship as having been seen in the same practice on at least 2 occasions in the 12 months prior to admission. The primary outcomes were the percentage of patients who had an INR measurement done and the percentage who had a therapeutic INR value within 10 days after discharge. As the 10‐day period is arbitrary, we also assessed these outcomes for the 3‐, 7‐, and 30‐day periods after discharge. The therapeutic range was defined for all patients as an INR of 2.0 to 3.0, as this is the target range for the large majority of patients on warfarin in our system. Outcomes during the intervention period were compared to baseline values during the preintervention period. For patients with multiple admissions, the first admission during each period was included.

Ambulatory Physician Survey

We surveyed ambulatory care physicians at the main practices for our health system. The survey assessed how often the STAR was viewed and incorporated into decision making, whether the report improved workflow, and whether ambulatory providers perceived that the report increased patient safety. The survey was distributed at the 6‐month interval during the intervention phase. The survey was disseminated electronically on 3 occasions, and a paper version was distributed on 1 occasion to housestaff and general medicine faculty.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons for categorical data were performed using the 2 test. P values were based on 2‐tailed tests of significance, and a value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The STAR was embedded in the discharge summary for 1370 (78.6%) discharges during the intervention period. A total of 505 patients in the preintervention period and 292 patients in the intervention period were established patients at an affiliated practice and comprised the study population. Demographics and indications for warfarin for the preintervention and intervention groups are listed in the Table 1.

| Preintervention Group, N=505 | Intervention Group, N=292 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y | 66.7 | 68.0 | 0.29 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 236 (46.7) | 153 (52.4) | 0.12 |

| Discharged on bridging agent, n (%) | 90 (17.8) | 36 (12.3) | 0.04 |

| Average length of stay, d | 7.1 | 7.6 | 0.46 |

| Newly prescribed warfarin, n (%) | 147 (29.1) | 62 (21.2) | 0.01 |

| INR 2.03.0 range at discharge, n (%) | 187 (37.0) | 137 (46.9) | 0.02 |

| Warfarin indication, n (%)* | |||

| Venous thromboembolism | 93 (18.4) | 39 (13.4) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 204 (40.3) | 127 (43.5) | |

| Mechanical heart valve | 19 (3.8) | 17 (6.5) | |

| Prevention of thromboembolism | 142 (28.1) | 94 (32.2) | |

| Intracardiac thrombosis | 3 (0.5) | 6 (2.1) | |

| Thrombophilia | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Other | 19 (3.8) | 12 (4.1) | |

| No indication | 32 (6.3) | 1 (3.8) | |

The frequency of INR testing within 10 days of discharge was similar for the preintervention and intervention periods (41.4% and 47.6%, respectively, P=0.09). Similarly, the likelihood of having at least 1 therapeutic INR value within 10 days of discharge was not statistically different for the groups (17.0% and 21.2%, P=0.14). The pattern was similar for the 3‐, 7‐, and 30‐day periods; a higher percentage of the intervention group had INR testing and attained a therapeutic INR value, though for no time period did this reach statistical significance. This pattern was also found when limiting the analysis to patients discharged home rather than to a facility, patients on warfarin, prior to admission, and patients started on warfarin during the hospitalization.

A total of 87of 207 (42.0%) clinicians responded to the survey. Of respondents, 75% reported that they had seen 1 patient who had been discharged on warfarin since the STAR initiative had begun, 58% of whom reported having viewed the STAR. Most respondents who viewed the STAR found it to be helpful or very helpful in guiding warfarin management (67%), improving their workflow and efficiency (58%), and improving patient safety (77%). Approximately one‐third of respondents who had viewed the STAR (34%) reported that they selected a different dose than they would have chosen had the STAR not been available.

DISCUSSION

We developed a concise report that is seamlessly created and inserted into the discharge summary. Though the STAR was perceived as improving patient safety by ambulatory care providers, there was no impact on attaining a therapeutic INR after discharge. There are several possible explanations for a lack of benefit. Most notably, our intervention was comprised of a stand‐alone EMR‐based tool and focused on 1 component of the transitions process. Given the complexity of healthcare delivery and anticoagulant management, it is likely that broader interventions are required to improve clinical outcomes over the transition period. Potential targets of multifaceted approaches may include improving access to care, providing greater access to anticoagulation clinics, enhancing patient education, and promoting direct physician‐physician communication. Bundled interventions will likely need to include involvement of an interdisciplinary team, such as pharmacist involvement in the medication reconciliation process.

The transition period from the hospital to the outpatient setting has the potential to jeopardize patient safety if vital information is not reliably transmitted across venues.[5, 6, 7, 8] Forster and colleagues noted an 11% incidence of ADEs in the posthospitalization period, of which 60% were either preventable or ameliorable.[3] To decrease the risk to patient safety during the transitions period, the Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement by the Society of Hospital Medicine and other medical organizations called for incorporation of standard data transfer forms (templates and transmission protocols).[9] Despite the high risk and preventable nature of many of the events, few specific tools have been developed. As part of broader initiatives to improve the transitions process, the STAR may have the potential to be a means for health systems to improve the quality of the transition of care for patients on anticoagulants.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was performed at a single health system. It is unknown whether the EMR‐based report could be similarly employed at other systems. Second, our study was unable to assess clinical endpoints. Given the lack of effect on attaining a therapeutic INR, it is unlikely that downstream outcomes, such as thromboembolism, were impacted. Lastly, we were unable to examine whether our intervention improved the care of patients whose outpatient provider was external to our system.

The STAR is a concise tool developed to provide essential anticoagulant‐related information to ambulatory providers. Though the report was perceived as improving patient safety, our finding of a lack of impact on attaining a therapeutic INR after discharge suggests that the tool would need to be a component of a broader multifaceted intervention to impact clinical outcomes.

Disclosures

This project was funded by a grant from the Cardinal Health E3 Foundation. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Anticoagulants are among the prescriptions with the highest risk of an adverse drug event (ADE) after discharge, and many of these events are preventable.[1, 2, 3] In recognition of the high risk for adverse events, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Map details several key features of a safe anticoagulation management program, including the recommendation during the transition period that clinicians ensure proper lab monitoring and establish capacity for follow‐up testing.[4]

Despite the potential for harm, most hospitals do not have a structured process for the transmission of vital information related to warfarin management from the inpatient to the ambulatory setting. Our aim was to develop a concise report containing the essential information regarding the patient's anticoagulation regimen, the Safe Transitions Anticoagulation Report (STAR), and a process to ensure the report can be readily accessed and utilized by ambulatory clinicians.

METHODS

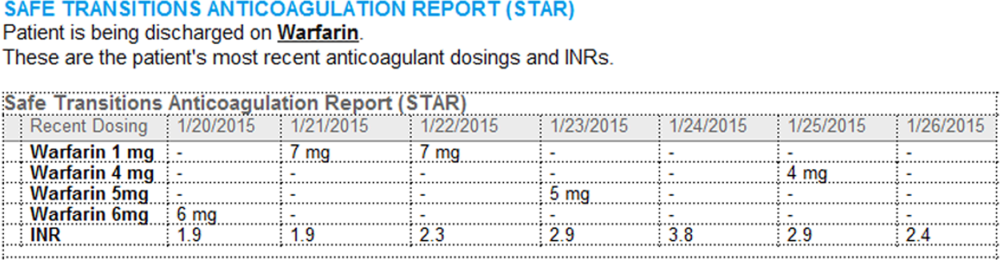

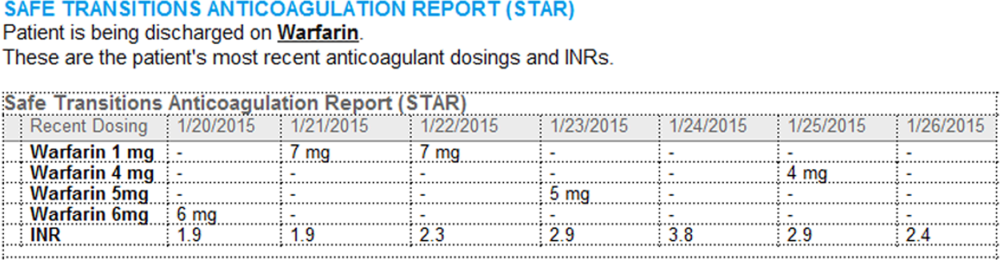

We assembled an interdisciplinary team to develop a new report and workflow to ensure that information on inpatient warfarin management was transmitted to outpatient providers in a reliable and structured manner. Explicit goals were to maximize use of the electronic medical record (EMR) to autopopulate aspects of the new report and create a process that worked seamlessly into the workflow. The final items were selected based on the risk of harm if not conveyed and feasibility of incorporation through the EMR:

- Warfarin doses: the 7 warfarin doses immediately prior to discharge

- International normalized ratio (INR) values: the 7 INR values immediately prior to discharge

- Bridging anticoagulation: the low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) prescribed as a bridging anticoagulant, if any

The STAR resides in both the discharge summary and the after visit summary (AVS) for patients discharged on warfarin. At our institution, the AVS contains a medication list, discharge instructions, and appointments, and is automatically produced through our EMR. Our institution utilizes the Epic EMR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) in the hospital, ambulatory clinics, and faculty practices.

A process was developed where a structured table is automatically created (Figure 1). A field was added to our EMR's discharge summary template asking whether the patient is being discharged on warfarin. Answering yes produces a second question asking whether the patient is also being discharged on bridging anticoagulation with LMWH. The STAR is not inserted into the discharge summary if the clinician completing the discharge summary deletes the anticoagulation question. The STAR is automatically created for patients discharged on warfarin and inserted into the AVS by the EMR regardless of whether the discharge summary has been completed. Patients are instructed by their nurse to bring their AVS to their follow‐up appointments.

The STAR project team utilized plan‐do‐study‐act cycles to test small changes and make revisions. The workflow was piloted on 2 medical/surgical units from January 2014 through March 2014, and revised based on feedback from clinicians and nursing staff. The STAR initiative was fully implemented across our institution in April 2014.

The study was evaluated by the institutional review board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and full review was waived.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were the timeliness of laboratory monitoring and quality of anticoagulation management for patients with an established relationship at 1 of the main outpatient practices in our system. Our institution has an anticoagulation clinic for patients followed at the general medicine clinic. We defined an established relationship as having been seen in the same practice on at least 2 occasions in the 12 months prior to admission. The primary outcomes were the percentage of patients who had an INR measurement done and the percentage who had a therapeutic INR value within 10 days after discharge. As the 10‐day period is arbitrary, we also assessed these outcomes for the 3‐, 7‐, and 30‐day periods after discharge. The therapeutic range was defined for all patients as an INR of 2.0 to 3.0, as this is the target range for the large majority of patients on warfarin in our system. Outcomes during the intervention period were compared to baseline values during the preintervention period. For patients with multiple admissions, the first admission during each period was included.

Ambulatory Physician Survey

We surveyed ambulatory care physicians at the main practices for our health system. The survey assessed how often the STAR was viewed and incorporated into decision making, whether the report improved workflow, and whether ambulatory providers perceived that the report increased patient safety. The survey was distributed at the 6‐month interval during the intervention phase. The survey was disseminated electronically on 3 occasions, and a paper version was distributed on 1 occasion to housestaff and general medicine faculty.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons for categorical data were performed using the 2 test. P values were based on 2‐tailed tests of significance, and a value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The STAR was embedded in the discharge summary for 1370 (78.6%) discharges during the intervention period. A total of 505 patients in the preintervention period and 292 patients in the intervention period were established patients at an affiliated practice and comprised the study population. Demographics and indications for warfarin for the preintervention and intervention groups are listed in the Table 1.

| Preintervention Group, N=505 | Intervention Group, N=292 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y | 66.7 | 68.0 | 0.29 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 236 (46.7) | 153 (52.4) | 0.12 |

| Discharged on bridging agent, n (%) | 90 (17.8) | 36 (12.3) | 0.04 |

| Average length of stay, d | 7.1 | 7.6 | 0.46 |

| Newly prescribed warfarin, n (%) | 147 (29.1) | 62 (21.2) | 0.01 |

| INR 2.03.0 range at discharge, n (%) | 187 (37.0) | 137 (46.9) | 0.02 |

| Warfarin indication, n (%)* | |||

| Venous thromboembolism | 93 (18.4) | 39 (13.4) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 204 (40.3) | 127 (43.5) | |

| Mechanical heart valve | 19 (3.8) | 17 (6.5) | |

| Prevention of thromboembolism | 142 (28.1) | 94 (32.2) | |

| Intracardiac thrombosis | 3 (0.5) | 6 (2.1) | |

| Thrombophilia | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Other | 19 (3.8) | 12 (4.1) | |

| No indication | 32 (6.3) | 1 (3.8) | |

The frequency of INR testing within 10 days of discharge was similar for the preintervention and intervention periods (41.4% and 47.6%, respectively, P=0.09). Similarly, the likelihood of having at least 1 therapeutic INR value within 10 days of discharge was not statistically different for the groups (17.0% and 21.2%, P=0.14). The pattern was similar for the 3‐, 7‐, and 30‐day periods; a higher percentage of the intervention group had INR testing and attained a therapeutic INR value, though for no time period did this reach statistical significance. This pattern was also found when limiting the analysis to patients discharged home rather than to a facility, patients on warfarin, prior to admission, and patients started on warfarin during the hospitalization.

A total of 87of 207 (42.0%) clinicians responded to the survey. Of respondents, 75% reported that they had seen 1 patient who had been discharged on warfarin since the STAR initiative had begun, 58% of whom reported having viewed the STAR. Most respondents who viewed the STAR found it to be helpful or very helpful in guiding warfarin management (67%), improving their workflow and efficiency (58%), and improving patient safety (77%). Approximately one‐third of respondents who had viewed the STAR (34%) reported that they selected a different dose than they would have chosen had the STAR not been available.

DISCUSSION

We developed a concise report that is seamlessly created and inserted into the discharge summary. Though the STAR was perceived as improving patient safety by ambulatory care providers, there was no impact on attaining a therapeutic INR after discharge. There are several possible explanations for a lack of benefit. Most notably, our intervention was comprised of a stand‐alone EMR‐based tool and focused on 1 component of the transitions process. Given the complexity of healthcare delivery and anticoagulant management, it is likely that broader interventions are required to improve clinical outcomes over the transition period. Potential targets of multifaceted approaches may include improving access to care, providing greater access to anticoagulation clinics, enhancing patient education, and promoting direct physician‐physician communication. Bundled interventions will likely need to include involvement of an interdisciplinary team, such as pharmacist involvement in the medication reconciliation process.

The transition period from the hospital to the outpatient setting has the potential to jeopardize patient safety if vital information is not reliably transmitted across venues.[5, 6, 7, 8] Forster and colleagues noted an 11% incidence of ADEs in the posthospitalization period, of which 60% were either preventable or ameliorable.[3] To decrease the risk to patient safety during the transitions period, the Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement by the Society of Hospital Medicine and other medical organizations called for incorporation of standard data transfer forms (templates and transmission protocols).[9] Despite the high risk and preventable nature of many of the events, few specific tools have been developed. As part of broader initiatives to improve the transitions process, the STAR may have the potential to be a means for health systems to improve the quality of the transition of care for patients on anticoagulants.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was performed at a single health system. It is unknown whether the EMR‐based report could be similarly employed at other systems. Second, our study was unable to assess clinical endpoints. Given the lack of effect on attaining a therapeutic INR, it is unlikely that downstream outcomes, such as thromboembolism, were impacted. Lastly, we were unable to examine whether our intervention improved the care of patients whose outpatient provider was external to our system.

The STAR is a concise tool developed to provide essential anticoagulant‐related information to ambulatory providers. Though the report was perceived as improving patient safety, our finding of a lack of impact on attaining a therapeutic INR after discharge suggests that the tool would need to be a component of a broader multifaceted intervention to impact clinical outcomes.

Disclosures

This project was funded by a grant from the Cardinal Health E3 Foundation. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , Medication errors: experience of the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) MEDMARX reporting system. J Clin Pharm. 2003;43:760–767.

- , , , , The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–167.

- , , , , Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Int Med. 2005;204:317–323.

- IHI Improvement Map. Available at: http://app.ihi.org/imap/tool/#Process=54aa289b‐16fd‐4a64‐8329‐3941dfc565d1. Accessed February 20 2015.

- , , , Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , , Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–841.

- Transitions of care in patients receiving oral anticoagulants: general principles, procedures, and impact of new oral anticoagulants. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28:54–65.

- Care transitions in anticoagulation management for patients with atrial fibrillation: an emphasis on safety. Oschner J. 2013;13:419–427.

- , , , et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:364–370.

- , , , Medication errors: experience of the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) MEDMARX reporting system. J Clin Pharm. 2003;43:760–767.

- , , , , The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–167.

- , , , , Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Int Med. 2005;204:317–323.

- IHI Improvement Map. Available at: http://app.ihi.org/imap/tool/#Process=54aa289b‐16fd‐4a64‐8329‐3941dfc565d1. Accessed February 20 2015.

- , , , Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , , Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–841.

- Transitions of care in patients receiving oral anticoagulants: general principles, procedures, and impact of new oral anticoagulants. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28:54–65.

- Care transitions in anticoagulation management for patients with atrial fibrillation: an emphasis on safety. Oschner J. 2013;13:419–427.

- , , , et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:364–370.

When Should Antiplatelet Agents and Anticoagulants Be Restarted after Gastrointestinal Bleed?

Source: Adapted from Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

Two Cases

A 76-year-old female with a history of hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and diverticulosis is admitted with acute onset of dizziness and several episodes of bright red blood per rectum. Her labs show a new anemia at hemoglobin level 6.9 g/dL and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.7. She is transfused several units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma without further bleeding. She undergoes an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, which are notable only for extensive diverticulosis. In preparing the discharge medication reconciliation, you are uncertain what to do with the patient’s anticoagulation.

An 85-year-old male with coronary artery disease status post-percutaneous coronary intervention, with placement of a drug-eluting stent several years prior, is admitted with multiple weeks of epigastric discomfort and acute onset of hematemesis. His laboratory tests are notable for a new anemia at hemoglobin level 6.5 g/dL. Urgent EGD demonstrates a bleeding ulcer, which is cauterized. He is started on a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI). He inquires as to when he can restart his home medications, including aspirin.

Overview

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a serious complication of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy. Risks for GI bleeding include older age, history of peptic ulcer disease, NSAID or steroid use, and the use of antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy. The estimated incidence of GI bleeding in the general population is 48 to 160 cases (upper GI) and 21 cases (lower GI) per 1,000 adults per year, with a case-mortality rate between 5% and 14%.1

Although there is consensus on ceasing anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents during an acute GI bleed, debate remains over the appropriate approach to restarting these agents.

Anticoagulant Resumption

A recent study published in Archives of Internal Medicine supports a quick resumption of anticoagulation following a GI bleed.2 Although previous studies on restarting anticoagulants were small and demonstrated mixed results, this retrospective cohort study examined more than 442 warfarin-associated GI bleeds. After adjusting for various clinical indicators (e.g. clinical seriousness of bleeding, requirement of transfusions), the investigators found that the decision not to resume warfarin within 90 days of an initial GI hemorrhage was associated with an increased risk of thrombosis and death. Of note, in those patients restarted on warfarin, the mean time to medication initiation was four days following the initial GI bleed. In those not restarted on warfarin, the earliest incidence of thrombosis was documented at eight days following cessation of anticoagulation.2

Though its clinical implications are limited by the retrospective design, this study is helpful in guiding management decisions. Randomized control trials and society recommendations on this topic are lacking, so the decision to resume anticoagulants rests on patient-specific estimates of the risk of recurrent bleeding and the benefits of resuming anticoagulants.

In identifying those patients most likely to benefit from restarting anticoagulation, the risk of thromboembolism should be determined using an established risk stratification framework, such as Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th edition (see Table 1).3 According to the guidelines, patients at highest risk of thromboembolism (in the absence of anticoagulation) are those with:

- mitral valve prostheses;

- atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of five to six or cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) within the last three months; and/or

- venous thromboembolism (VTE) within the last three months or history of severe thrombophilia.

Patients at the lowest risk of thromboembolism are those with:

- mechanical aortic prostheses with no other stroke risk factors;

- atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of zero to two; and/or

- a single VTE that occurred >12 months prior.

There are several approaches to identifying patients at greatest risk for bleeding. Location-specific modeling for upper GI bleeds (e.g. Rockall score) and lower GI bleeds (e.g. BLEED score) focus on the clinical presentation and/or endoscopic findings. General hemorrhage risk scores (e.g. HAS-BLED, ATRIA) focus on medical comorbidities. While easy to use, the predictive value of such scores as part of anticoagulation resumption after a GI hemorrhage remains uncertain.

Based on the above methods of risk stratification, patients at higher risk of thromboembolism and lower risk of bleeding will likely benefit from waiting only a short time interval before restarting anticoagulation. Based on the trial conducted by Witt and colleagues, anticoagulation typically can be reinitiated within four days of obtaining hemostatic and hemodynamic stability.2 Conversely, those at highest risk of bleeding and lower risk of thromboembolism will benefit from a delayed resumption of anticoagulation. Involvement of a specialist, such as a gastroenterologist, could help further clarify the risk of rebleeding.

The ideal approach for patients with a high risk of both bleeding and thromboembolism remains uncertain. Such cases highlight the need for an informed discussion with the patient and any involved caregivers, as well as involvement of inpatient subspecialists and outpatient longitudinal providers.

There remains a lack of evidence on the best method to restart anticoagulation. Based on small and retrospective trials, we recommend restarting warfarin at the patient’s previous home dose. The duration of inpatient monitoring following warfarin initiation should be individualized, but warfarin is not expected to impair coagulation for four to six days after initiation.

Little data is available with respect to the role of novel oral anticoagulants after a GI bleed. Given the lack of reversing agents for these drugs, we recommend exercising caution in populations with a high risk of rebleeding. Theoretically, given that these agents reach peak effect faster than warfarin, waiting an additional four days after the time frame recommended for starting warfarin is a prudent resumption strategy for novel oral anticoagulants.

Source: Adapted from Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

Resumption of Antiplatelet Agents

The decision to resume antiplatelet therapy should also be highly individualized. In addition to weighing the risk of bleeding (as described in the previous section), the physician must also estimate the benefits of antiplatelet therapy in decreasing the risk of cardiovascular events.

In low-risk patients on antiplatelet therapy (i.e., for primary cardiovascular prevention) reinitiation after a bleeding episode can be reasonably delayed, because the risk of rebleeding likely outweighs the potential benefit of restarting therapy.

For patients who are at intermediate risk (i.e., those on antiplatelet agents for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease), emerging evidence argues for early reinstitution after a GI bleed. In a trial published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Sung and colleagues randomized 156 patients to aspirin or placebo therapy immediately following endoscopically obtained hemostasis for peptic ulcer bleeding.4 All patients received PPIs. There was no significant difference in bleeding rates between the two groups, but delayed resumption of aspirin was associated with a significant increase in all-cause mortality.

Two recent meta-analyses provide further insight into the risks of withholding aspirin therapy. The first, which included 50,279 patients on aspirin for secondary prevention, found that aspirin non-adherence or withdrawal after a GI bleed was associated with a three-fold higher risk of major adverse cardiac events.5 Cardiac event rates were highest in the subgroup of patients with a history of prior percutaneous coronary stenting.

A second meta-analysis evaluated patients who had aspirin held perioperatively. In a population of patients on aspirin for secondary prevention, the mean time after withholding aspirin was 8.5 days to coronary events, 14.3 days to cerebrovascular events, and 25.8 days to peripheral arterial events.6 Events occurred as early as five days after withdrawal of aspirin.

Patients with recent intracoronary stenting are at highest risk of thrombosis. In patients with a bare metal stent placed within six weeks, or a drug-eluting stent placed within six months, every effort should be made to minimize interruptions of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Based on the data presented above, for patients at intermediate and/or high risk of adverse cardiac events, we recommend reinstitution of aspirin as soon as possible following a GI hemorrhage, preferably within five days. PPI co-therapy is a mainstay for secondary prevention of upper GI bleeding in patients on antiplatelet therapy. Current research and guidelines have not addressed specifically the role of withholding and reinitiating aspirin in lower GI bleeding, non-peptic ulcer, or upper-GI bleeding, however, a similar strategy is likely appropriate. As with the decision for restarting anticoagulants, discussion with relevant specialists is essential to best define the risk of re-bleeding.

Back to the Cases

Given her CHADS2 score of three, the patient with a diverticular bleed has a 9.6% annual risk of stroke if she does not resume anticoagulation. Using the HAS-BLED and ATRIA scores, this patient has 2.6% to 5.8% annual risk of hemorrhage. We recommend resuming warfarin anticoagulation therapy within four days of achieving hemostasis.

For the patient with coronary artery disease with remote drug-eluting stent placement and upper GI bleed, evidence supports early resumption of appropriate antiplatelet therapy following endoscopic therapy and hemostasis. We recommend resuming aspirin during the current hospitalization and concomitant treatment with a PPI indefinitely.

Bottom Line

Following a GI bleed, the risks and benefits of restarting anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents need to be carefully considered. In patients on oral anticoagulants at high risk for thromboembolism and low risk for rebleeding, consider restarting anticoagulation within four to five days. Patients on antiplatelet agents for secondary prevention should have the medication restarted during hospitalization after endoscopically obtained hemostasis of a peptic ulcer.

In all cases, hospitalists should engage the patient, gastroenterologist, and outpatient provider to best determine when resumption of anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet agents should occur.

Dr. Allen-Dicker is a hospitalist and clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Briones is director of perioperative services in the division of hospital medicine and an assistant professor; Dr. Berman is a hospitalist and a clinical instructor, and Dr. Dunn is a professor of medicine and chief of the division of hospital medicine, all at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

References

- Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):101-113.

- Witt DM, Delate T, Garcia DA, et al. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1484-1491.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

- Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):1-9.

- Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2667-2674.

- Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, Rücker G. Low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention – cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation – review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2005;257(5):399-414.

Source: Adapted from Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

Two Cases

A 76-year-old female with a history of hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and diverticulosis is admitted with acute onset of dizziness and several episodes of bright red blood per rectum. Her labs show a new anemia at hemoglobin level 6.9 g/dL and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.7. She is transfused several units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma without further bleeding. She undergoes an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, which are notable only for extensive diverticulosis. In preparing the discharge medication reconciliation, you are uncertain what to do with the patient’s anticoagulation.

An 85-year-old male with coronary artery disease status post-percutaneous coronary intervention, with placement of a drug-eluting stent several years prior, is admitted with multiple weeks of epigastric discomfort and acute onset of hematemesis. His laboratory tests are notable for a new anemia at hemoglobin level 6.5 g/dL. Urgent EGD demonstrates a bleeding ulcer, which is cauterized. He is started on a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI). He inquires as to when he can restart his home medications, including aspirin.

Overview

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a serious complication of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy. Risks for GI bleeding include older age, history of peptic ulcer disease, NSAID or steroid use, and the use of antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy. The estimated incidence of GI bleeding in the general population is 48 to 160 cases (upper GI) and 21 cases (lower GI) per 1,000 adults per year, with a case-mortality rate between 5% and 14%.1

Although there is consensus on ceasing anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents during an acute GI bleed, debate remains over the appropriate approach to restarting these agents.

Anticoagulant Resumption

A recent study published in Archives of Internal Medicine supports a quick resumption of anticoagulation following a GI bleed.2 Although previous studies on restarting anticoagulants were small and demonstrated mixed results, this retrospective cohort study examined more than 442 warfarin-associated GI bleeds. After adjusting for various clinical indicators (e.g. clinical seriousness of bleeding, requirement of transfusions), the investigators found that the decision not to resume warfarin within 90 days of an initial GI hemorrhage was associated with an increased risk of thrombosis and death. Of note, in those patients restarted on warfarin, the mean time to medication initiation was four days following the initial GI bleed. In those not restarted on warfarin, the earliest incidence of thrombosis was documented at eight days following cessation of anticoagulation.2

Though its clinical implications are limited by the retrospective design, this study is helpful in guiding management decisions. Randomized control trials and society recommendations on this topic are lacking, so the decision to resume anticoagulants rests on patient-specific estimates of the risk of recurrent bleeding and the benefits of resuming anticoagulants.

In identifying those patients most likely to benefit from restarting anticoagulation, the risk of thromboembolism should be determined using an established risk stratification framework, such as Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th edition (see Table 1).3 According to the guidelines, patients at highest risk of thromboembolism (in the absence of anticoagulation) are those with:

- mitral valve prostheses;

- atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of five to six or cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) within the last three months; and/or

- venous thromboembolism (VTE) within the last three months or history of severe thrombophilia.

Patients at the lowest risk of thromboembolism are those with:

- mechanical aortic prostheses with no other stroke risk factors;

- atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of zero to two; and/or

- a single VTE that occurred >12 months prior.

There are several approaches to identifying patients at greatest risk for bleeding. Location-specific modeling for upper GI bleeds (e.g. Rockall score) and lower GI bleeds (e.g. BLEED score) focus on the clinical presentation and/or endoscopic findings. General hemorrhage risk scores (e.g. HAS-BLED, ATRIA) focus on medical comorbidities. While easy to use, the predictive value of such scores as part of anticoagulation resumption after a GI hemorrhage remains uncertain.

Based on the above methods of risk stratification, patients at higher risk of thromboembolism and lower risk of bleeding will likely benefit from waiting only a short time interval before restarting anticoagulation. Based on the trial conducted by Witt and colleagues, anticoagulation typically can be reinitiated within four days of obtaining hemostatic and hemodynamic stability.2 Conversely, those at highest risk of bleeding and lower risk of thromboembolism will benefit from a delayed resumption of anticoagulation. Involvement of a specialist, such as a gastroenterologist, could help further clarify the risk of rebleeding.

The ideal approach for patients with a high risk of both bleeding and thromboembolism remains uncertain. Such cases highlight the need for an informed discussion with the patient and any involved caregivers, as well as involvement of inpatient subspecialists and outpatient longitudinal providers.

There remains a lack of evidence on the best method to restart anticoagulation. Based on small and retrospective trials, we recommend restarting warfarin at the patient’s previous home dose. The duration of inpatient monitoring following warfarin initiation should be individualized, but warfarin is not expected to impair coagulation for four to six days after initiation.

Little data is available with respect to the role of novel oral anticoagulants after a GI bleed. Given the lack of reversing agents for these drugs, we recommend exercising caution in populations with a high risk of rebleeding. Theoretically, given that these agents reach peak effect faster than warfarin, waiting an additional four days after the time frame recommended for starting warfarin is a prudent resumption strategy for novel oral anticoagulants.

Source: Adapted from Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

Resumption of Antiplatelet Agents

The decision to resume antiplatelet therapy should also be highly individualized. In addition to weighing the risk of bleeding (as described in the previous section), the physician must also estimate the benefits of antiplatelet therapy in decreasing the risk of cardiovascular events.

In low-risk patients on antiplatelet therapy (i.e., for primary cardiovascular prevention) reinitiation after a bleeding episode can be reasonably delayed, because the risk of rebleeding likely outweighs the potential benefit of restarting therapy.

For patients who are at intermediate risk (i.e., those on antiplatelet agents for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease), emerging evidence argues for early reinstitution after a GI bleed. In a trial published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Sung and colleagues randomized 156 patients to aspirin or placebo therapy immediately following endoscopically obtained hemostasis for peptic ulcer bleeding.4 All patients received PPIs. There was no significant difference in bleeding rates between the two groups, but delayed resumption of aspirin was associated with a significant increase in all-cause mortality.

Two recent meta-analyses provide further insight into the risks of withholding aspirin therapy. The first, which included 50,279 patients on aspirin for secondary prevention, found that aspirin non-adherence or withdrawal after a GI bleed was associated with a three-fold higher risk of major adverse cardiac events.5 Cardiac event rates were highest in the subgroup of patients with a history of prior percutaneous coronary stenting.

A second meta-analysis evaluated patients who had aspirin held perioperatively. In a population of patients on aspirin for secondary prevention, the mean time after withholding aspirin was 8.5 days to coronary events, 14.3 days to cerebrovascular events, and 25.8 days to peripheral arterial events.6 Events occurred as early as five days after withdrawal of aspirin.

Patients with recent intracoronary stenting are at highest risk of thrombosis. In patients with a bare metal stent placed within six weeks, or a drug-eluting stent placed within six months, every effort should be made to minimize interruptions of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Based on the data presented above, for patients at intermediate and/or high risk of adverse cardiac events, we recommend reinstitution of aspirin as soon as possible following a GI hemorrhage, preferably within five days. PPI co-therapy is a mainstay for secondary prevention of upper GI bleeding in patients on antiplatelet therapy. Current research and guidelines have not addressed specifically the role of withholding and reinitiating aspirin in lower GI bleeding, non-peptic ulcer, or upper-GI bleeding, however, a similar strategy is likely appropriate. As with the decision for restarting anticoagulants, discussion with relevant specialists is essential to best define the risk of re-bleeding.

Back to the Cases

Given her CHADS2 score of three, the patient with a diverticular bleed has a 9.6% annual risk of stroke if she does not resume anticoagulation. Using the HAS-BLED and ATRIA scores, this patient has 2.6% to 5.8% annual risk of hemorrhage. We recommend resuming warfarin anticoagulation therapy within four days of achieving hemostasis.

For the patient with coronary artery disease with remote drug-eluting stent placement and upper GI bleed, evidence supports early resumption of appropriate antiplatelet therapy following endoscopic therapy and hemostasis. We recommend resuming aspirin during the current hospitalization and concomitant treatment with a PPI indefinitely.

Bottom Line

Following a GI bleed, the risks and benefits of restarting anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents need to be carefully considered. In patients on oral anticoagulants at high risk for thromboembolism and low risk for rebleeding, consider restarting anticoagulation within four to five days. Patients on antiplatelet agents for secondary prevention should have the medication restarted during hospitalization after endoscopically obtained hemostasis of a peptic ulcer.

In all cases, hospitalists should engage the patient, gastroenterologist, and outpatient provider to best determine when resumption of anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet agents should occur.

Dr. Allen-Dicker is a hospitalist and clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Briones is director of perioperative services in the division of hospital medicine and an assistant professor; Dr. Berman is a hospitalist and a clinical instructor, and Dr. Dunn is a professor of medicine and chief of the division of hospital medicine, all at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

References

- Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):101-113.

- Witt DM, Delate T, Garcia DA, et al. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1484-1491.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

- Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):1-9.

- Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2667-2674.

- Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, Rücker G. Low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention – cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation – review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2005;257(5):399-414.

Source: Adapted from Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

Two Cases

A 76-year-old female with a history of hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and diverticulosis is admitted with acute onset of dizziness and several episodes of bright red blood per rectum. Her labs show a new anemia at hemoglobin level 6.9 g/dL and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.7. She is transfused several units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma without further bleeding. She undergoes an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, which are notable only for extensive diverticulosis. In preparing the discharge medication reconciliation, you are uncertain what to do with the patient’s anticoagulation.

An 85-year-old male with coronary artery disease status post-percutaneous coronary intervention, with placement of a drug-eluting stent several years prior, is admitted with multiple weeks of epigastric discomfort and acute onset of hematemesis. His laboratory tests are notable for a new anemia at hemoglobin level 6.5 g/dL. Urgent EGD demonstrates a bleeding ulcer, which is cauterized. He is started on a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI). He inquires as to when he can restart his home medications, including aspirin.

Overview

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a serious complication of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy. Risks for GI bleeding include older age, history of peptic ulcer disease, NSAID or steroid use, and the use of antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy. The estimated incidence of GI bleeding in the general population is 48 to 160 cases (upper GI) and 21 cases (lower GI) per 1,000 adults per year, with a case-mortality rate between 5% and 14%.1

Although there is consensus on ceasing anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents during an acute GI bleed, debate remains over the appropriate approach to restarting these agents.

Anticoagulant Resumption

A recent study published in Archives of Internal Medicine supports a quick resumption of anticoagulation following a GI bleed.2 Although previous studies on restarting anticoagulants were small and demonstrated mixed results, this retrospective cohort study examined more than 442 warfarin-associated GI bleeds. After adjusting for various clinical indicators (e.g. clinical seriousness of bleeding, requirement of transfusions), the investigators found that the decision not to resume warfarin within 90 days of an initial GI hemorrhage was associated with an increased risk of thrombosis and death. Of note, in those patients restarted on warfarin, the mean time to medication initiation was four days following the initial GI bleed. In those not restarted on warfarin, the earliest incidence of thrombosis was documented at eight days following cessation of anticoagulation.2

Though its clinical implications are limited by the retrospective design, this study is helpful in guiding management decisions. Randomized control trials and society recommendations on this topic are lacking, so the decision to resume anticoagulants rests on patient-specific estimates of the risk of recurrent bleeding and the benefits of resuming anticoagulants.

In identifying those patients most likely to benefit from restarting anticoagulation, the risk of thromboembolism should be determined using an established risk stratification framework, such as Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th edition (see Table 1).3 According to the guidelines, patients at highest risk of thromboembolism (in the absence of anticoagulation) are those with:

- mitral valve prostheses;

- atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of five to six or cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) within the last three months; and/or

- venous thromboembolism (VTE) within the last three months or history of severe thrombophilia.

Patients at the lowest risk of thromboembolism are those with:

- mechanical aortic prostheses with no other stroke risk factors;

- atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of zero to two; and/or

- a single VTE that occurred >12 months prior.

There are several approaches to identifying patients at greatest risk for bleeding. Location-specific modeling for upper GI bleeds (e.g. Rockall score) and lower GI bleeds (e.g. BLEED score) focus on the clinical presentation and/or endoscopic findings. General hemorrhage risk scores (e.g. HAS-BLED, ATRIA) focus on medical comorbidities. While easy to use, the predictive value of such scores as part of anticoagulation resumption after a GI hemorrhage remains uncertain.

Based on the above methods of risk stratification, patients at higher risk of thromboembolism and lower risk of bleeding will likely benefit from waiting only a short time interval before restarting anticoagulation. Based on the trial conducted by Witt and colleagues, anticoagulation typically can be reinitiated within four days of obtaining hemostatic and hemodynamic stability.2 Conversely, those at highest risk of bleeding and lower risk of thromboembolism will benefit from a delayed resumption of anticoagulation. Involvement of a specialist, such as a gastroenterologist, could help further clarify the risk of rebleeding.

The ideal approach for patients with a high risk of both bleeding and thromboembolism remains uncertain. Such cases highlight the need for an informed discussion with the patient and any involved caregivers, as well as involvement of inpatient subspecialists and outpatient longitudinal providers.

There remains a lack of evidence on the best method to restart anticoagulation. Based on small and retrospective trials, we recommend restarting warfarin at the patient’s previous home dose. The duration of inpatient monitoring following warfarin initiation should be individualized, but warfarin is not expected to impair coagulation for four to six days after initiation.

Little data is available with respect to the role of novel oral anticoagulants after a GI bleed. Given the lack of reversing agents for these drugs, we recommend exercising caution in populations with a high risk of rebleeding. Theoretically, given that these agents reach peak effect faster than warfarin, waiting an additional four days after the time frame recommended for starting warfarin is a prudent resumption strategy for novel oral anticoagulants.

Source: Adapted from Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

Resumption of Antiplatelet Agents

The decision to resume antiplatelet therapy should also be highly individualized. In addition to weighing the risk of bleeding (as described in the previous section), the physician must also estimate the benefits of antiplatelet therapy in decreasing the risk of cardiovascular events.

In low-risk patients on antiplatelet therapy (i.e., for primary cardiovascular prevention) reinitiation after a bleeding episode can be reasonably delayed, because the risk of rebleeding likely outweighs the potential benefit of restarting therapy.

For patients who are at intermediate risk (i.e., those on antiplatelet agents for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease), emerging evidence argues for early reinstitution after a GI bleed. In a trial published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Sung and colleagues randomized 156 patients to aspirin or placebo therapy immediately following endoscopically obtained hemostasis for peptic ulcer bleeding.4 All patients received PPIs. There was no significant difference in bleeding rates between the two groups, but delayed resumption of aspirin was associated with a significant increase in all-cause mortality.

Two recent meta-analyses provide further insight into the risks of withholding aspirin therapy. The first, which included 50,279 patients on aspirin for secondary prevention, found that aspirin non-adherence or withdrawal after a GI bleed was associated with a three-fold higher risk of major adverse cardiac events.5 Cardiac event rates were highest in the subgroup of patients with a history of prior percutaneous coronary stenting.

A second meta-analysis evaluated patients who had aspirin held perioperatively. In a population of patients on aspirin for secondary prevention, the mean time after withholding aspirin was 8.5 days to coronary events, 14.3 days to cerebrovascular events, and 25.8 days to peripheral arterial events.6 Events occurred as early as five days after withdrawal of aspirin.

Patients with recent intracoronary stenting are at highest risk of thrombosis. In patients with a bare metal stent placed within six weeks, or a drug-eluting stent placed within six months, every effort should be made to minimize interruptions of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Based on the data presented above, for patients at intermediate and/or high risk of adverse cardiac events, we recommend reinstitution of aspirin as soon as possible following a GI hemorrhage, preferably within five days. PPI co-therapy is a mainstay for secondary prevention of upper GI bleeding in patients on antiplatelet therapy. Current research and guidelines have not addressed specifically the role of withholding and reinitiating aspirin in lower GI bleeding, non-peptic ulcer, or upper-GI bleeding, however, a similar strategy is likely appropriate. As with the decision for restarting anticoagulants, discussion with relevant specialists is essential to best define the risk of re-bleeding.

Back to the Cases

Given her CHADS2 score of three, the patient with a diverticular bleed has a 9.6% annual risk of stroke if she does not resume anticoagulation. Using the HAS-BLED and ATRIA scores, this patient has 2.6% to 5.8% annual risk of hemorrhage. We recommend resuming warfarin anticoagulation therapy within four days of achieving hemostasis.

For the patient with coronary artery disease with remote drug-eluting stent placement and upper GI bleed, evidence supports early resumption of appropriate antiplatelet therapy following endoscopic therapy and hemostasis. We recommend resuming aspirin during the current hospitalization and concomitant treatment with a PPI indefinitely.

Bottom Line

Following a GI bleed, the risks and benefits of restarting anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents need to be carefully considered. In patients on oral anticoagulants at high risk for thromboembolism and low risk for rebleeding, consider restarting anticoagulation within four to five days. Patients on antiplatelet agents for secondary prevention should have the medication restarted during hospitalization after endoscopically obtained hemostasis of a peptic ulcer.

In all cases, hospitalists should engage the patient, gastroenterologist, and outpatient provider to best determine when resumption of anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet agents should occur.

Dr. Allen-Dicker is a hospitalist and clinical instructor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Briones is director of perioperative services in the division of hospital medicine and an assistant professor; Dr. Berman is a hospitalist and a clinical instructor, and Dr. Dunn is a professor of medicine and chief of the division of hospital medicine, all at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

References

- Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):101-113.

- Witt DM, Delate T, Garcia DA, et al. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1484-1491.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e326S-350S.

- Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):1-9.

- Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2667-2674.

- Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, Rücker G. Low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention – cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation – review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2005;257(5):399-414.