User login

Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma of the External Auditory Canal

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

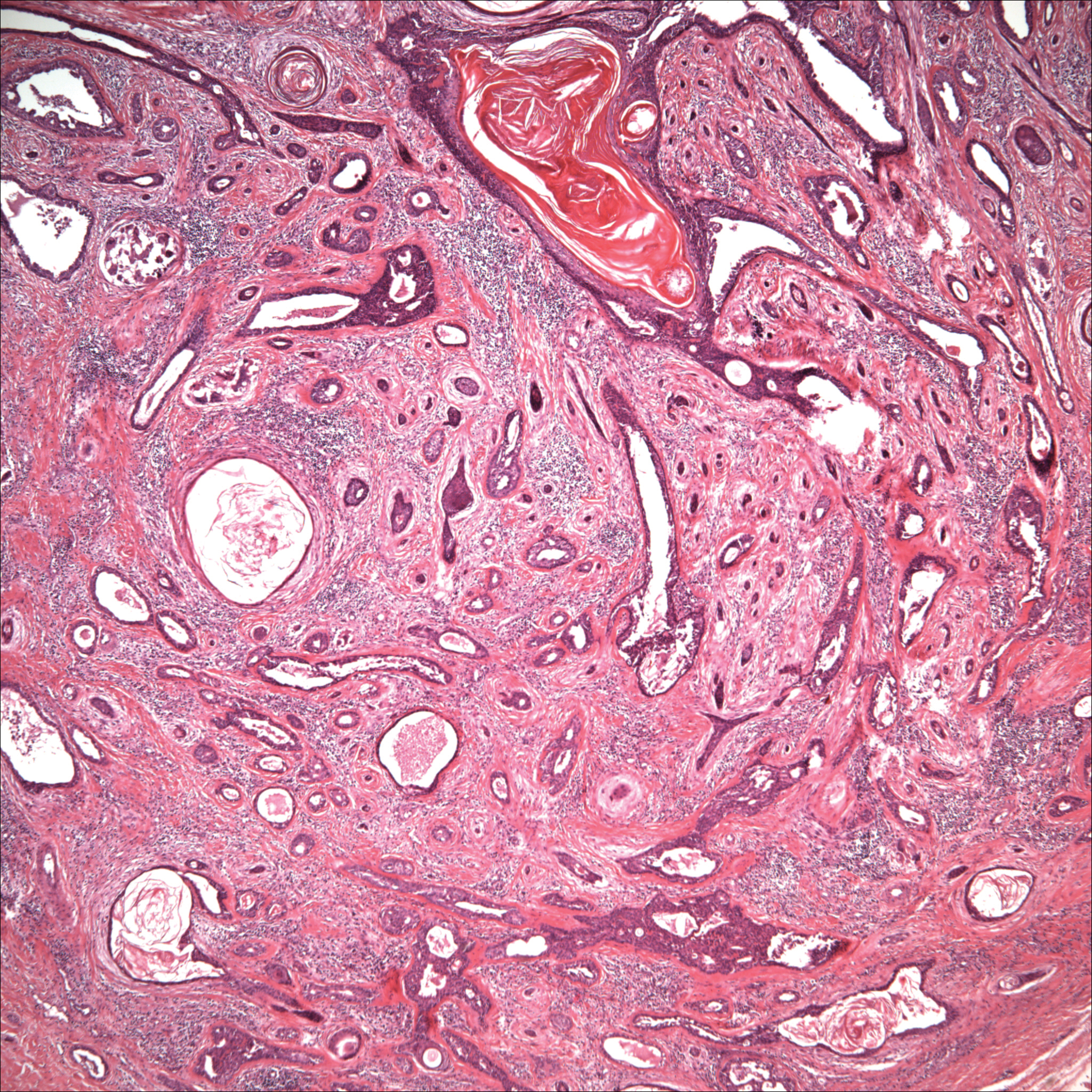

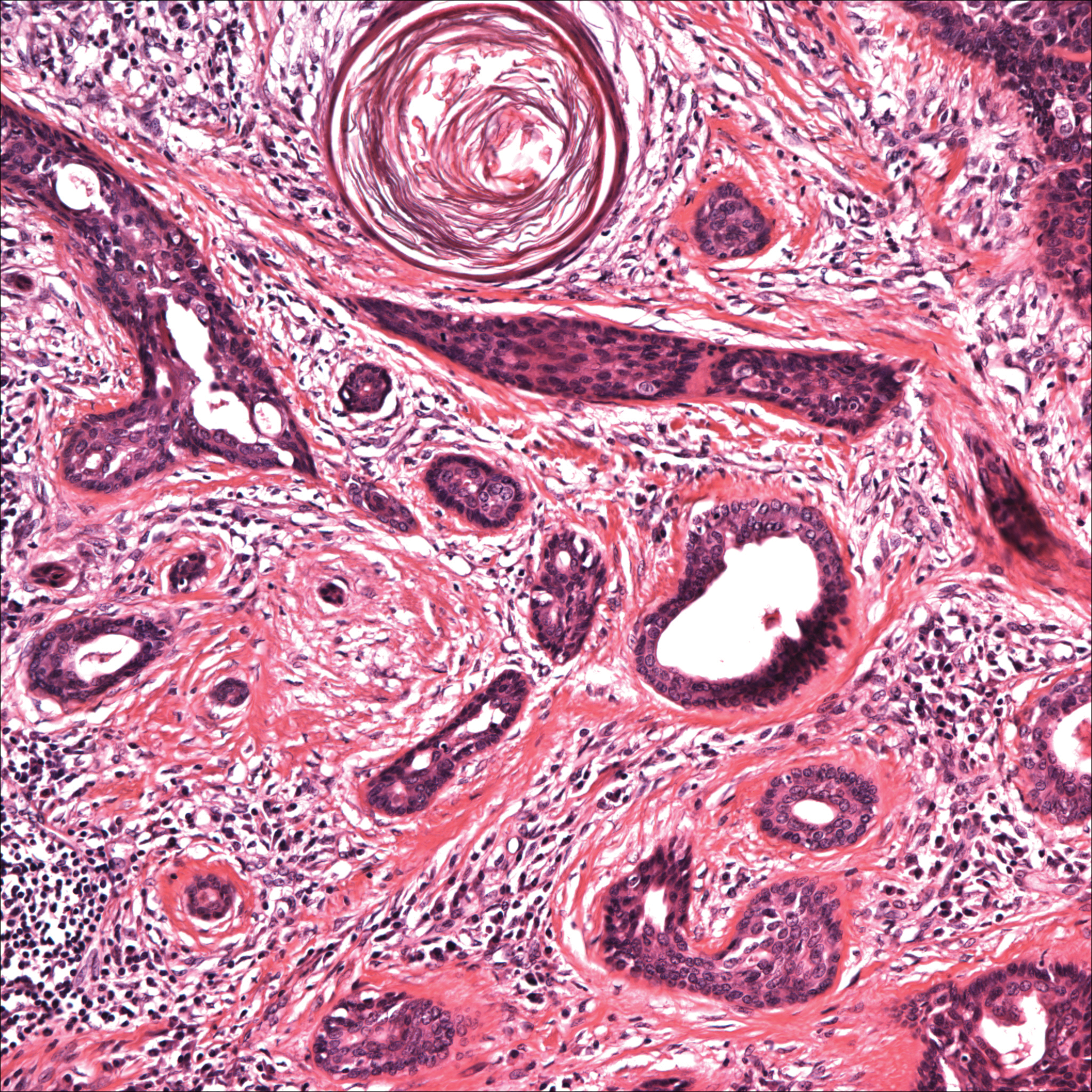

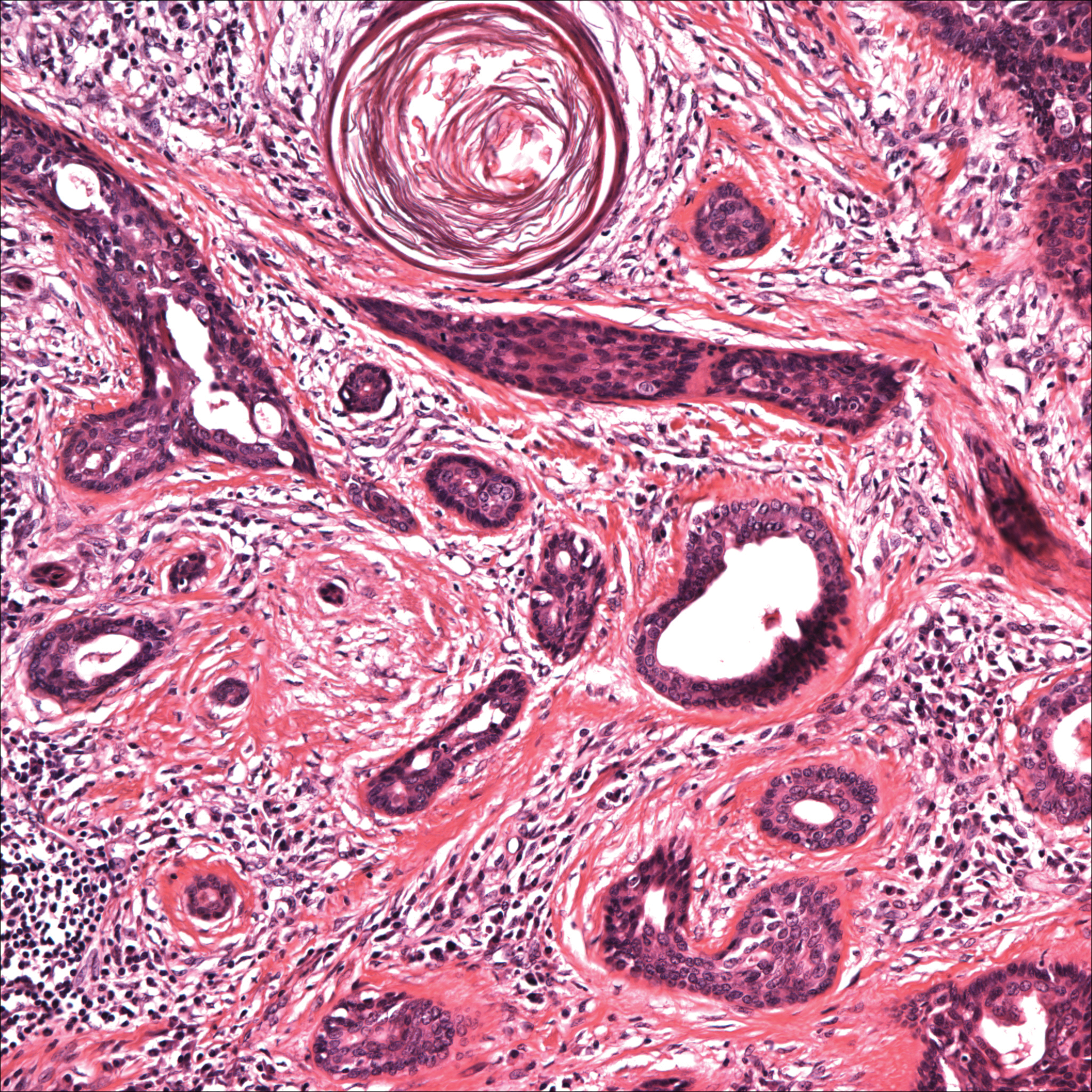

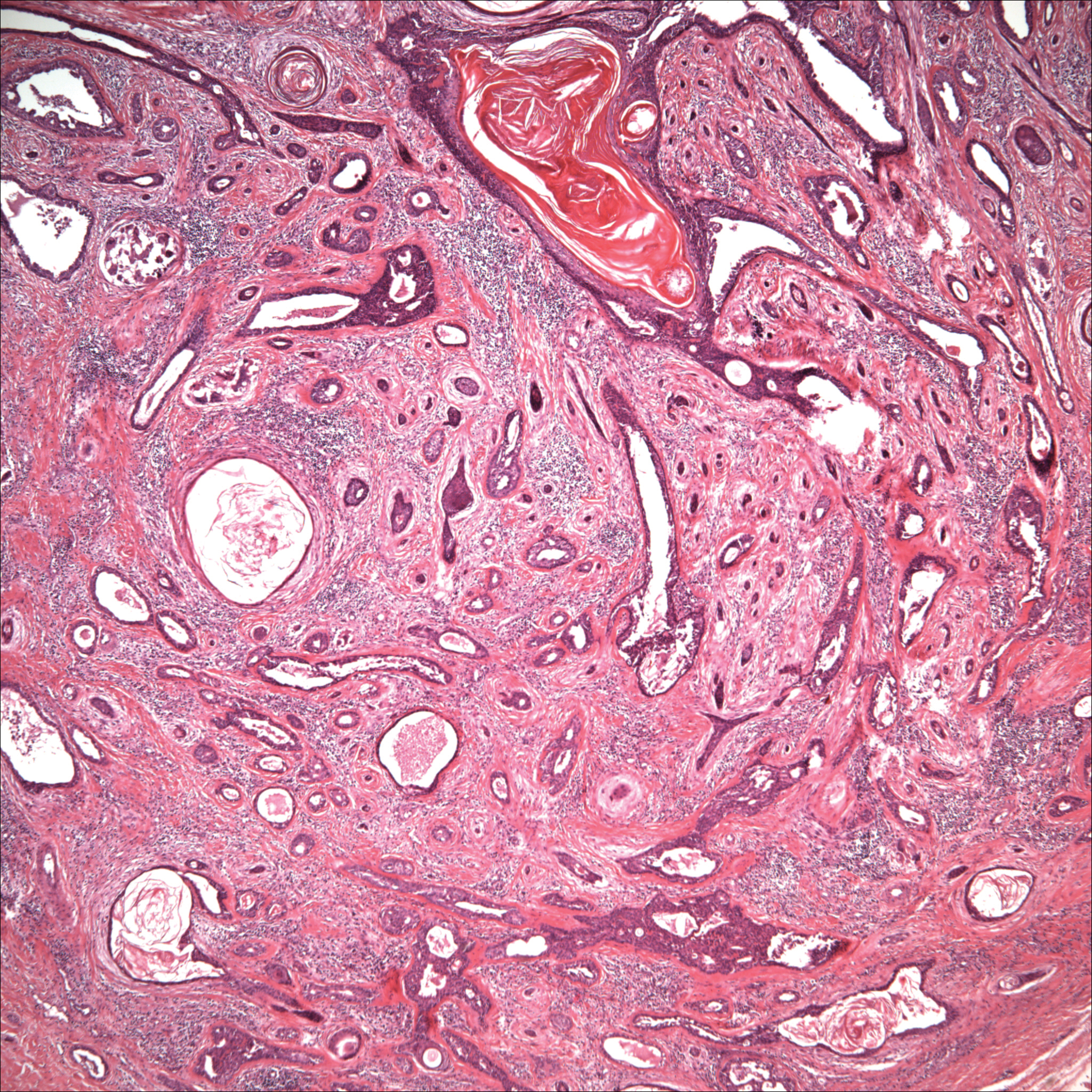

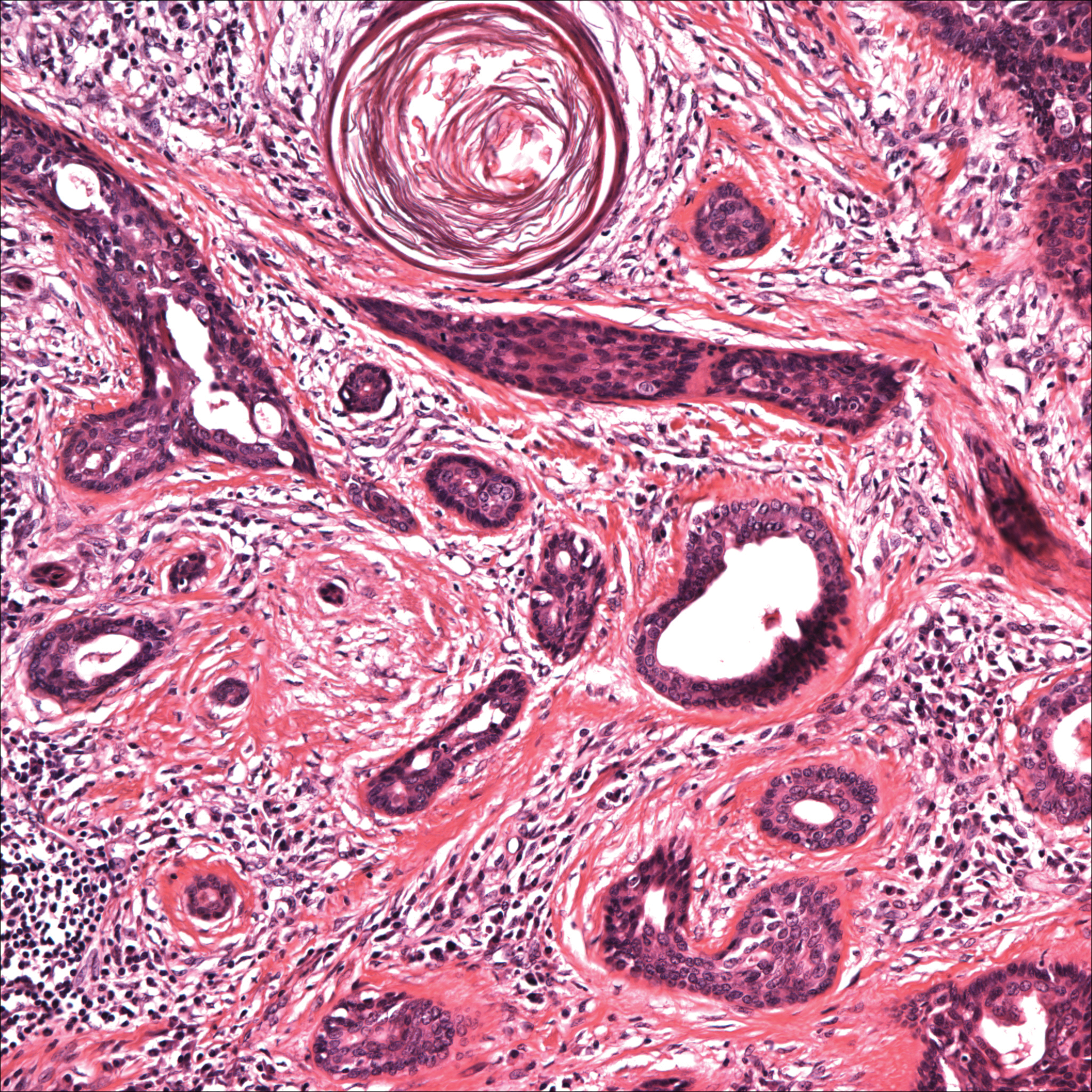

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

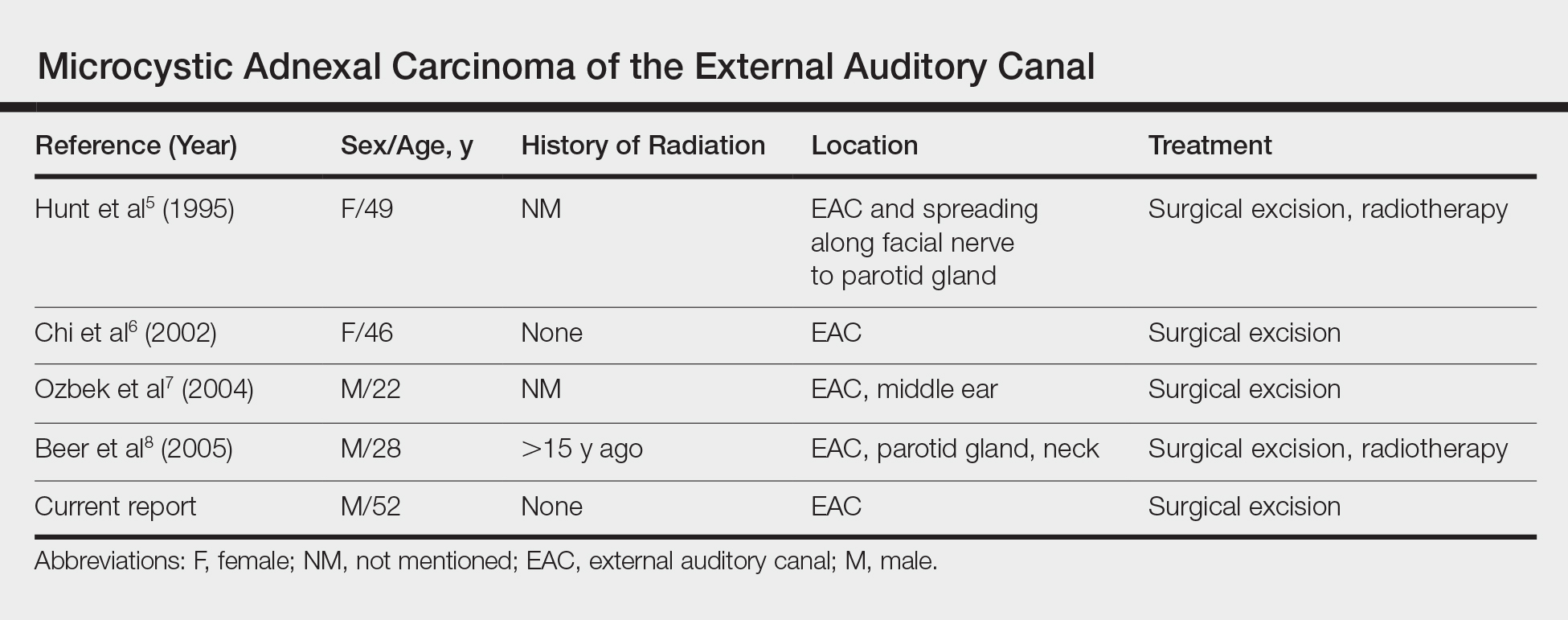

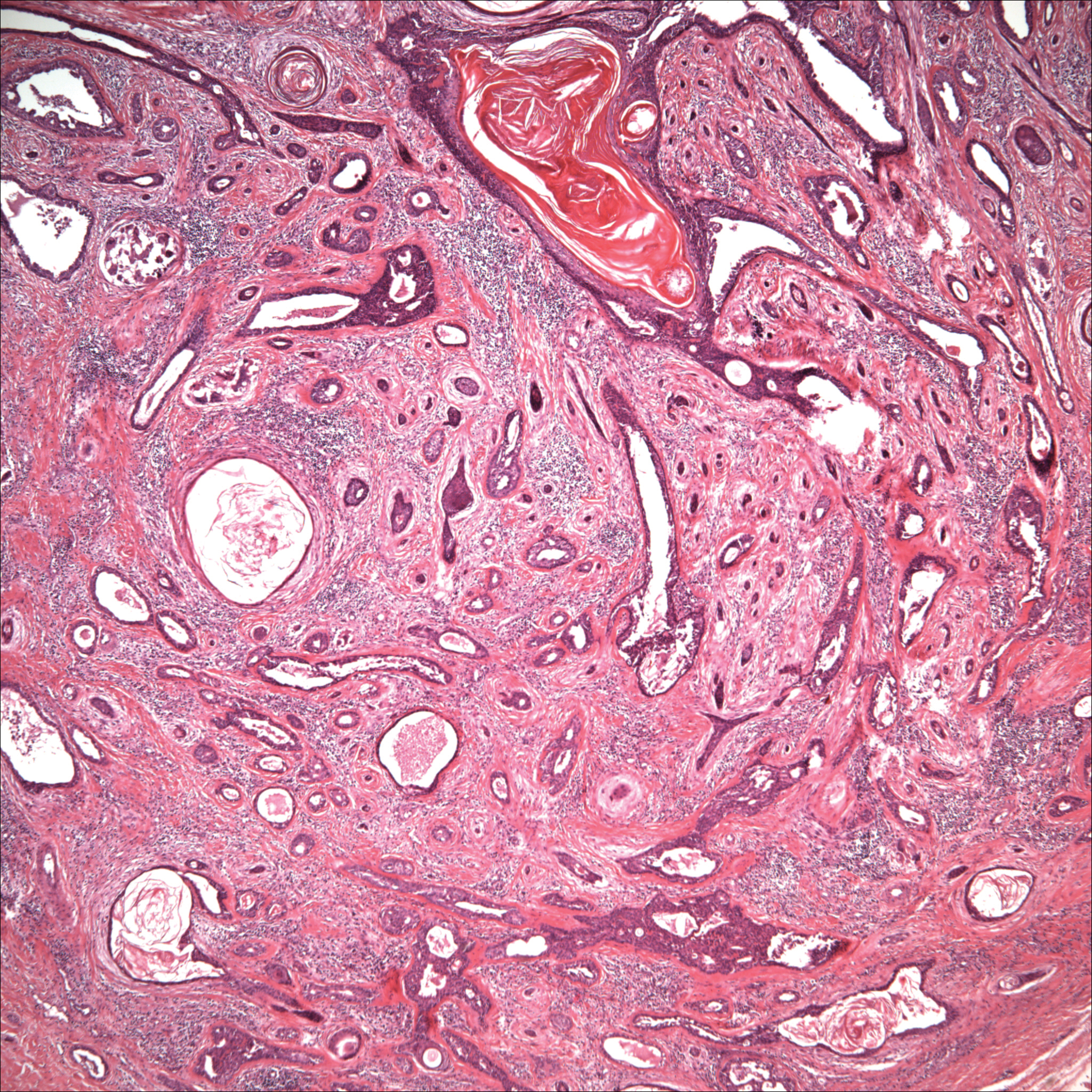

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

Practice Points

- Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor with a high potential for local recurrence.

- The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.

- Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence is essential.

Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

To the Editor:

Onychomadesis is characterized by separation of the nail plate from the matrix due to a temporary arrest in nail matrix activity. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is a relatively common viral infection, especially in children. Although the relationship between onychomadesis and HFMD has been noted, there are few reports in the literature.1-9 We present 2 cases of onychomadesis following HFMD in Taiwanese siblings.

A 3-year-old girl presented with proximal nail plate detachment from the proximal nail fold on the bilateral great toenails (Figure 1) and a transverse whole-thickness sulcus on the bilateral thumbnails (Figure 2) of several weeks’ duration. Her 6-year-old sister had similar nail changes. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease was diagnosed about 4 weeks prior to nail changes. The mother reported that only the younger sister experienced fever. There was no history of notable medication intake, nail trauma, periungual erythema, vesicular lesion, or dermatitis. In both patients, the nail changes were temporary with spontaneous normal nail plate regrowth several months later. A diagnosis of onychomadesis was made.

The etiology of onychomadesis includes drug ingestion, especially chemotherapy; severe systemic diseases; high fever; infection, including viral illnesses such as influenza, measles, and HFMD; and idiopathic onychomadesis.1,2,5,10 In 2000, Clementz and Mancini1 reported 5 children with nail matrix arrest following HFMD and suggested an epidemic caused by the same virus strain. Bernier et al2 reported another 4 cases and suggested more than one viral strain may have been implicated in the nail matrix arrest. Although these authors list HFMD as one of the causes of onychomadesis,1,2 the number of cases reported was small; however, studies with a larger number of cases and even outbreak have been reported more recently.3-8 Salazar et al3 reported an onychomadesis outbreak associated with HFMD in Valencia, Spain, in 2008 (N=298). This outbreak primarily was caused by coxsackievirus (CV) A10 (49% of cases).5 Another onychomadesis outbreak occurred in Saragossa, Spain, in 2008, and CV B1, B2, and unidentified nonpoliovirus enterovirus were isolated.6 Outbreaks also occurred in Finland in 2008, and the causative agents were identified as CV A6 and A10.7,8 The latency period for onychomadesis following HFMD was 1 to 2 months (mean, 40 days), and the majority of cases occurred in patients younger than 6 years.1-5 Not all of the nails were involved; in one report, each patient shed only 4 nails on average.6

Although there is a definite relationship between HFMD and onychomadesis, the mechanism is still unclear. Some authors claim that nail matrix arrest is caused by high fever10; however, we found that 40% (2/5)1 to 63% (10/16)4 of reported cases did not have a fever. Additionally, only 1 of our patients had fever. Therefore high fever–induced nail matrix arrest is not a reasonable explanation. Davia et al5 observed no relationship between onychomadesis and the severity of HFMD. In addition, no serious complications of HFMD were mentioned in prior reports.

We propose that HFMD-related onychomadesis is caused by the viral infection itself, rather than by severe systemic disease.1-5,7 Certain viral strains associated with HFMD can induce arrest of nail matrix activity. Osterback et al7 detected CV A6 in shed nail fragments and suggested that virus replication damaged the nail matrix and resulted in temporary nail dystrophy. This hypothesis can explain that only some nails, not all, were involved. In our cases, we noted an incomplete and slanted cleft on the thumbnail (Figure 2). We also found that incomplete onychomadesis appeared in the clinical photograph from a prior report.5 The slanted cleft in our case may be caused by secondary external force after original incomplete onychomadesis or a different rate of nail regrowth because of different intensity of nail matrix damage. The phenomenon of incomplete onychomadesis in the same nail further suggests the mechanism of onychomadesis following HFMD is localized nail matrix damage.

In conclusion, we report 2 cases of onychomadesis associated with HFMD. Our report highlights that there is no racial difference in post-HFMD onychomadesis. These cases highlight that HFMD is an important cause of onychomadesis, especially in children. We suggest that certain viral strains associated with HFMD may specifically arrest nail matrix growth activity, regardless of fever or disease severity.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Bernier V, Labreze C, Bury F, et al. Nail matrix arrest in the course of hand, foot and mouth disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:649-651.

- Salazar A, Febrer I, Guiral S, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, June 2008. Euro Surveill. 2008;13:18917.

- Redondo Granado MJ, Torres Hinojal MC, Izquierdo López B. Post viral onychomadesis outbreak in Valladolid [in Spanish]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;71:436-439.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Habif TP. Nail diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010:947-973.

To the Editor:

Onychomadesis is characterized by separation of the nail plate from the matrix due to a temporary arrest in nail matrix activity. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is a relatively common viral infection, especially in children. Although the relationship between onychomadesis and HFMD has been noted, there are few reports in the literature.1-9 We present 2 cases of onychomadesis following HFMD in Taiwanese siblings.

A 3-year-old girl presented with proximal nail plate detachment from the proximal nail fold on the bilateral great toenails (Figure 1) and a transverse whole-thickness sulcus on the bilateral thumbnails (Figure 2) of several weeks’ duration. Her 6-year-old sister had similar nail changes. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease was diagnosed about 4 weeks prior to nail changes. The mother reported that only the younger sister experienced fever. There was no history of notable medication intake, nail trauma, periungual erythema, vesicular lesion, or dermatitis. In both patients, the nail changes were temporary with spontaneous normal nail plate regrowth several months later. A diagnosis of onychomadesis was made.

The etiology of onychomadesis includes drug ingestion, especially chemotherapy; severe systemic diseases; high fever; infection, including viral illnesses such as influenza, measles, and HFMD; and idiopathic onychomadesis.1,2,5,10 In 2000, Clementz and Mancini1 reported 5 children with nail matrix arrest following HFMD and suggested an epidemic caused by the same virus strain. Bernier et al2 reported another 4 cases and suggested more than one viral strain may have been implicated in the nail matrix arrest. Although these authors list HFMD as one of the causes of onychomadesis,1,2 the number of cases reported was small; however, studies with a larger number of cases and even outbreak have been reported more recently.3-8 Salazar et al3 reported an onychomadesis outbreak associated with HFMD in Valencia, Spain, in 2008 (N=298). This outbreak primarily was caused by coxsackievirus (CV) A10 (49% of cases).5 Another onychomadesis outbreak occurred in Saragossa, Spain, in 2008, and CV B1, B2, and unidentified nonpoliovirus enterovirus were isolated.6 Outbreaks also occurred in Finland in 2008, and the causative agents were identified as CV A6 and A10.7,8 The latency period for onychomadesis following HFMD was 1 to 2 months (mean, 40 days), and the majority of cases occurred in patients younger than 6 years.1-5 Not all of the nails were involved; in one report, each patient shed only 4 nails on average.6

Although there is a definite relationship between HFMD and onychomadesis, the mechanism is still unclear. Some authors claim that nail matrix arrest is caused by high fever10; however, we found that 40% (2/5)1 to 63% (10/16)4 of reported cases did not have a fever. Additionally, only 1 of our patients had fever. Therefore high fever–induced nail matrix arrest is not a reasonable explanation. Davia et al5 observed no relationship between onychomadesis and the severity of HFMD. In addition, no serious complications of HFMD were mentioned in prior reports.

We propose that HFMD-related onychomadesis is caused by the viral infection itself, rather than by severe systemic disease.1-5,7 Certain viral strains associated with HFMD can induce arrest of nail matrix activity. Osterback et al7 detected CV A6 in shed nail fragments and suggested that virus replication damaged the nail matrix and resulted in temporary nail dystrophy. This hypothesis can explain that only some nails, not all, were involved. In our cases, we noted an incomplete and slanted cleft on the thumbnail (Figure 2). We also found that incomplete onychomadesis appeared in the clinical photograph from a prior report.5 The slanted cleft in our case may be caused by secondary external force after original incomplete onychomadesis or a different rate of nail regrowth because of different intensity of nail matrix damage. The phenomenon of incomplete onychomadesis in the same nail further suggests the mechanism of onychomadesis following HFMD is localized nail matrix damage.

In conclusion, we report 2 cases of onychomadesis associated with HFMD. Our report highlights that there is no racial difference in post-HFMD onychomadesis. These cases highlight that HFMD is an important cause of onychomadesis, especially in children. We suggest that certain viral strains associated with HFMD may specifically arrest nail matrix growth activity, regardless of fever or disease severity.

To the Editor:

Onychomadesis is characterized by separation of the nail plate from the matrix due to a temporary arrest in nail matrix activity. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is a relatively common viral infection, especially in children. Although the relationship between onychomadesis and HFMD has been noted, there are few reports in the literature.1-9 We present 2 cases of onychomadesis following HFMD in Taiwanese siblings.

A 3-year-old girl presented with proximal nail plate detachment from the proximal nail fold on the bilateral great toenails (Figure 1) and a transverse whole-thickness sulcus on the bilateral thumbnails (Figure 2) of several weeks’ duration. Her 6-year-old sister had similar nail changes. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease was diagnosed about 4 weeks prior to nail changes. The mother reported that only the younger sister experienced fever. There was no history of notable medication intake, nail trauma, periungual erythema, vesicular lesion, or dermatitis. In both patients, the nail changes were temporary with spontaneous normal nail plate regrowth several months later. A diagnosis of onychomadesis was made.

The etiology of onychomadesis includes drug ingestion, especially chemotherapy; severe systemic diseases; high fever; infection, including viral illnesses such as influenza, measles, and HFMD; and idiopathic onychomadesis.1,2,5,10 In 2000, Clementz and Mancini1 reported 5 children with nail matrix arrest following HFMD and suggested an epidemic caused by the same virus strain. Bernier et al2 reported another 4 cases and suggested more than one viral strain may have been implicated in the nail matrix arrest. Although these authors list HFMD as one of the causes of onychomadesis,1,2 the number of cases reported was small; however, studies with a larger number of cases and even outbreak have been reported more recently.3-8 Salazar et al3 reported an onychomadesis outbreak associated with HFMD in Valencia, Spain, in 2008 (N=298). This outbreak primarily was caused by coxsackievirus (CV) A10 (49% of cases).5 Another onychomadesis outbreak occurred in Saragossa, Spain, in 2008, and CV B1, B2, and unidentified nonpoliovirus enterovirus were isolated.6 Outbreaks also occurred in Finland in 2008, and the causative agents were identified as CV A6 and A10.7,8 The latency period for onychomadesis following HFMD was 1 to 2 months (mean, 40 days), and the majority of cases occurred in patients younger than 6 years.1-5 Not all of the nails were involved; in one report, each patient shed only 4 nails on average.6

Although there is a definite relationship between HFMD and onychomadesis, the mechanism is still unclear. Some authors claim that nail matrix arrest is caused by high fever10; however, we found that 40% (2/5)1 to 63% (10/16)4 of reported cases did not have a fever. Additionally, only 1 of our patients had fever. Therefore high fever–induced nail matrix arrest is not a reasonable explanation. Davia et al5 observed no relationship between onychomadesis and the severity of HFMD. In addition, no serious complications of HFMD were mentioned in prior reports.

We propose that HFMD-related onychomadesis is caused by the viral infection itself, rather than by severe systemic disease.1-5,7 Certain viral strains associated with HFMD can induce arrest of nail matrix activity. Osterback et al7 detected CV A6 in shed nail fragments and suggested that virus replication damaged the nail matrix and resulted in temporary nail dystrophy. This hypothesis can explain that only some nails, not all, were involved. In our cases, we noted an incomplete and slanted cleft on the thumbnail (Figure 2). We also found that incomplete onychomadesis appeared in the clinical photograph from a prior report.5 The slanted cleft in our case may be caused by secondary external force after original incomplete onychomadesis or a different rate of nail regrowth because of different intensity of nail matrix damage. The phenomenon of incomplete onychomadesis in the same nail further suggests the mechanism of onychomadesis following HFMD is localized nail matrix damage.

In conclusion, we report 2 cases of onychomadesis associated with HFMD. Our report highlights that there is no racial difference in post-HFMD onychomadesis. These cases highlight that HFMD is an important cause of onychomadesis, especially in children. We suggest that certain viral strains associated with HFMD may specifically arrest nail matrix growth activity, regardless of fever or disease severity.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Bernier V, Labreze C, Bury F, et al. Nail matrix arrest in the course of hand, foot and mouth disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:649-651.

- Salazar A, Febrer I, Guiral S, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, June 2008. Euro Surveill. 2008;13:18917.

- Redondo Granado MJ, Torres Hinojal MC, Izquierdo López B. Post viral onychomadesis outbreak in Valladolid [in Spanish]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;71:436-439.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Habif TP. Nail diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010:947-973.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Bernier V, Labreze C, Bury F, et al. Nail matrix arrest in the course of hand, foot and mouth disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:649-651.

- Salazar A, Febrer I, Guiral S, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, June 2008. Euro Surveill. 2008;13:18917.

- Redondo Granado MJ, Torres Hinojal MC, Izquierdo López B. Post viral onychomadesis outbreak in Valladolid [in Spanish]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;71:436-439.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Habif TP. Nail diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010:947-973.

Practice Points

- Onychomadesis is a late complication of hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) with a latency period of 1 to 2 months.

- Although the mechanism between onychomadesis and HFMD is still unclear, we propose that it is caused by the viral infection itself rather than severe systemic disease.