User login

Status Report From the American Acne & Rosacea Society on Medical Management of Acne in Adult Women, Part 3: Oral Therapies

Selection of oral agents for treatment of AV in adult women is dependent on multiple factors including the patient’s age, medication history, child-bearing potential, clinical presentation, and treatment preference following a discussion of the anticipated benefits versus potential risks.1,2 In patients with the mixed inflammatory and comedonal clinical pattern of AV, oral antibiotics can be used concurrently with topical therapies when moderate to severe inflammatory lesions are noted.3,4 However, many adult women who had AV as teenagers have already utilized oral antibiotic therapies in the past and often are interested in alternative options, express concerns regarding antibiotic resistance, report a history of antibiotic-associated yeast infections or other side effects, and/or encounter issues related to drug-drug interactions.3,5-8 Oral hormonal therapies such as combination oral contraceptives (COCs) or spironolactone often are utilized to treat adult women with AV, sometimes in combination with each other or other agents. Combination oral contraceptives appear to be especially effective in the management of the U-shaped clinical pattern or predominantly inflammatory, late-onset AV.1,5,9,10 Potential warnings, contraindications, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions are important to keep in mind when considering the use of oral hormonal therapies.8-10 Oral isotretinoin, which should be prescribed with strict adherence to the iPLEDGE™ program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/), remains a viable option for cases of severe nodular AV and selected cases of refractory inflammatory AV, especially when scarring and/or marked psychosocial distress are noted.1,2,5,11 Although it is recognized that adult women with AV typically present with either a mixed inflammatory and comedonal or U-shaped clinical pattern predominantly involving the lower face and anterolateral neck, the available data do not adequately differentiate the relative responsiveness of these clinical patterns to specific therapeutic agents.

Combination Oral Contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives are commonly used to treat AV in adult women, including those without and those with measurable androgen excess (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]). Combination oral contraceptives contain ethinyl estradiol and a progestational agent (eg, progestin); the latter varies in terms of its nonselective receptor interactions and the relative magnitude or absence of androgenic effects.10,12,13 Although some COCs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AV, there is little data available to determine the comparative efficacy among these and other COCs.10,14 When choosing a COC for treatment of AV, it is best to select an agent whose effectiveness is supported by evidence from clinical studies.10,15

Mechanisms of Action

The reported mechanisms of action for COCs include inhibition of ovarian androgen production and ovulation through gonadotropin suppression; upregulated synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin, which decreases free testosterone levels through receptor binding; and inhibition of 5α-reductase (by some progestins), which reduces conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the active derivative that induces androgenic effects at peripheral target tissues.10,13,16,17

Therapeutic Benefits

Use of COCs to treat AV in adult women who do not have measurable androgen excess is most rational in patients who also desire a method of contraception. Multiple monotherapy studies have demonstrated the efficacy of COCs in the treatment of AV on the face and trunk.4,10,12,15,17,18 It may take a minimum of 3 monthly cycles of use before acne lesion counts begin to appreciably decrease.12,15,19-21 Initiating COC therapy during menstruation ensures the absence of pregnancy. Combination oral contraceptives may be used with other topical and oral therapies for AV.2,3,9,10 Potential ancillary benefits of COCs include normalization of the menstrual cycle; reduced premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms; and reduced risk of endometrial cancer (approximately 50%), ovarian cancer (approximately 40%), and colorectal cancer.22-24

Risks and Contraindications

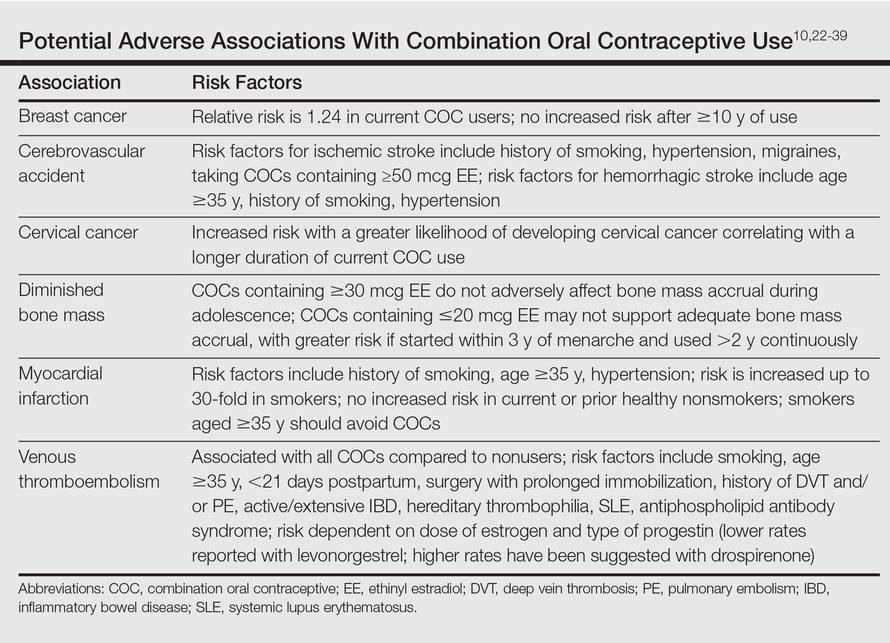

It is important to consider the potential risks associated with the use of COCs, especially in women with AV who are not seeking a method of contraception. Side effects of COCs can include nausea, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding, and weight gain.25,26 Potential adverse associations of COCs are described in the Table. The major potential vascular associations include venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular accident, all of which are influenced by concurrent factors such as a history of smoking, age (≥35 years), and hypertension.27-32 It is recommended that blood pressure be measured before initiating COC therapy as part of the general examination.33

The potential increase in breast cancer risk appears to be low, while the cervical cancer risk is reported to increase relative to the duration of use.34-37 This latter observation may be due to the greater likelihood of unprotected sex in women using a COC and exposure to multiple sexual partners in some cases, which may increase the likelihood of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection of the cervix. If a dermatologist elects to prescribe a COC to treat AV, it has been suggested that the patient also consult with her general practitioner or gynecologist to undergo pelvic and breast examinations and a Papanicolaou test.33 The recommendation for initial screening for cervical cancer is within 3 years of initiation of sexual intercourse or by 21 years of age, whichever is first.33,38,39

Combination oral contraceptives are not ideal for all adult women with AV. Absolute contraindications are pregnancy and history of thromboembolic, cardiac, or hepatic disease; in women aged 35 years and older who smoke, relative contraindications include hypertension, diabetes, migraines, breastfeeding, and current breast or liver cancer.33 In adult women with AV who have relative contra-indications but are likely to benefit from the use of a COC when other options are limited or not viable, consultation with a gynecologist is prudent. Other than rifamycin antibiotics (eg, rifampin) and griseofulvin, there is no definitive evidence that oral antibiotics (eg, tetracycline) or oral antifungal agents reduce the contraceptive efficacy of COCs, although cautions remain in print within some approved package inserts.8

Spironolactone

Available since 1957, spironolactone is an oral aldos-terone antagonist and potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension and congestive heart failure.9 Recognition of its antiandrogenic effects led to its use in dermatology to treat certain dermatologic disorders in women (eg, hirsutism, alopecia, AV).1,4,5,9,10 Spironolactone is not approved for AV by the FDA; therefore, available data from multiple independent studies and retrospective analyses that have been collectively reviewed support its efficacy when used as both monotherapy or in combination with other agents in adult women with AV, especially those with a U-shaped pattern and/or late-onset AV.9,40-43

Mechanism of Action

Spironolactone inhibits sebaceous gland activity through peripheral androgen receptor blockade, inhibition of 5α-reductase, decrease in androgen production, and increase in sex hormone–binding globulin.9,10,40

Therapeutic Benefits

Good to excellent improvement of AV in women, many of whom are postadolescent, has ranged from 66% to 100% in published reports9,40-43; however, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dosing regimens, and concomitant therapies were not usually controlled. Spironolactone has been used to treat AV in adult women as monotherapy or in combination with topical agents, oral antibiotics, and COCs.9,40-42 Additionally, dose-ranging studies have not been completed with spironolactone for AV.9,40 The suggested dose range is 50 mg to 200 mg daily; however, it usually is best to start at 50 mg daily and increase to 100 mg daily if clinical response is not adequate after 2 to 3 months. The gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of spironolactone is increased when ingested with a high-fat meal.9,10

Once effective control of AV is achieved, it is optimal to use the lowest dose needed to continue reasonable suppression of new AV lesions. There is no defined end point for spironolactone use in AV, with or without concurrent PCOS, as many adult women usually continue treatment with low-dose therapy because they experience marked flaring shortly after the drug is stopped.9

Risks and Contraindications

Side effects associated with spironolactone are dose related and include increased diuresis, migraines, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, gynecomastia, fatigue, and dizziness.9,10,40-44 Side effects (particularly menstrual irregularities and breast tenderness) are more common at doses higher than 100 mg daily, especially when used as monotherapy without concurrent use of a COC.9,40

Spironolactone-associated hyperkalemia is most clinically relevant in patients on higher doses (eg, 100–200 mg daily), in those with renal impairment and/or congestive heart failure, and when used concurrently with certain other medications. In any patient on spironolactone, the risk of clinically relevant hyperkalemia may be increased by coingestion of potassium supplements, potassium-based salt substitutes, potassium-sparing diuretics (eg, amiloride, triamterene); aldosterone antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, lisinopril, benazepril); angiotensin II receptor blockers (eg, losartan, valsartan); and tri-methoprim (with or without sulfamethoxazole).8,9,40,45 Spironolactone may also increase serum levels of lithium or digoxin.9,40,45,46 For management of AV, it is best that spironolactone be avoided in patients taking any of these medications.9

In healthy adult women with AV who are not on medications or supplements that interact adversely with spironolactone, there is no definitive recommendation regarding monitoring of serum potassium levels during treatment with spironolactone, and it has been suggested that monitoring serum potassium levels in this subgroup is not necessary.47 However, each clinician is advised to choose whether or not they wish to obtain baseline and/or periodic serum potassium levels when prescribing spironolactone for AV based on their degree of comfort and the patient’s history. Baseline and periodic blood testing to evaluate serum electrolytes and renal function are reasonable, especially as adult women with AV are usually treated with spironolactone over a prolonged period of time.9

The FDA black box warning for spironolactone states that it is tumorigenic in chronic toxicity studies in rats and refers to exposures 25- to 100-fold higher than those administered to humans.9,48 Although continued vigilance is warranted, evaluation of large populations of women treated with spironolactone do not suggest an association with increased risk of breast cancer.49,50

Spironolactone is a category C drug and thus should be avoided during pregnancy, primarily due to animal data suggesting risks of hypospadias and feminization in male fetuses.9 Importantly, there is an absence of reports linking exposure during pregnancy with congenital defects in humans, including in 2 known cases of high-dose exposures for maternal Bartter syndrome.9

The active metabolite, canrenone, is known to be present in breast milk at 0.2% of the maternal daily dose, but breastfeeding is generally believed to be safe with spironolactone based on evidence to date.9

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotic therapy may be used in combination with a topical regimen to treat AV in adult women, keeping in mind some important caveats.1-7 For instance, monotherapy with oral antibiotics should be avoided, and concomitant use of benzoyl peroxide is suggested to reduce emergence of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes strains.3,4 A therapeutic exit plan also is suggested when prescribing oral antibiotics to limit treatment to 3 to 4 months, if possible, to help mitigate the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (eg, staphylococci and streptococci).3-5,51

Tetracyclines, especially doxycycline and minocycline, are the most commonly prescribed agents. Doxycycline use warrants patient education on measures to limit the risks of esophageal and GI side effects and phototoxicity; enteric-coated and small tablet formulations have been shown to reduce GI side effects, especially when administered with food.3,52-55 In addition to vestibular side effects and hyperpigmentation, minocycline may be associated with rare but potentially severe adverse reactions such as drug hypersensitivity syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, and lupus-like syndrome, which are reported more commonly in women.5,52,54 Vestibular side effects have been shown to decrease with use of extended-release tablets with weight-based dosing.53

Oral Isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin is well established as highly effective for treatment of severe, recalcitrant AV, including nodular acne on the face and trunk.4,56 Currently available oral isotretinoins are branded generic formulations based on the pharmacokinetic profile of the original brand (Accutane [Roche Pharmaceuticals]) and with the use of Lidose Technology (Absorica [Cipher Pharmaceuticals]), which substantially increases GI absorption of isotretinoin in the absence of ingestion with a high-calorie, high-fat meal.57 The short- and long-term efficacy, dosing regimens, safety considerations, and serious teratogenic risks for oral isotretinoin are well published.4,56-58 Importantly, oral isotretinoin must be prescribed with strict adherence to the federally mandated iPLEDGE risk management program.

Low-dose oral isotretinoin therapy (<0.5 mg/kg–1 mg/kg daily) administered over several months longer than conventional regimens (ie, 16–20 weeks) has been suggested with demonstrated efficacy.57 However, this approach is not optimal due to the lack of established sustained clearance of AV after discontinuation of therapy and the greater potential for exposure to isotretinoin during pregnancy. Recurrences of AV do occur after completion of isotretinoin therapy, especially if cumulative systemic exposure to the drug during the initial course of treatment was inadequate.56,57

Oral isotretinoin has been shown to be effective in AV in adult women with or without PCOS with 0.5 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg daily and a total cumulative exposure of 120 mg/kg to 150 mg/kg.59 In one study, the presence of PCOS and greater number of nodules at baseline were predictive of a higher risk of relapse during the second year posttreatment.59

Conclusion

All oral therapies that are used to treat AV in adult women warrant individual consideration of possible benefits versus risks. Careful attention to possible side effects, patient-related risk factors, and potential drug-drug interactions is important. End points of therapy are not well established, with the exception of oral isotretinoin therapy. Clinicians must use their judgment in each case along with obtaining feedback from patients regarding the selection of therapy after a discussion of the available options.

- Holzmann R, Shakery K. Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(suppl 1):3-8.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Treatment guidelines in adult women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:198-207.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kim G. Optimizing use of oral antibiotics in acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:33-42.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Fisk WA, Lev-Tov HA, Sivamani RK. Epidemiology and management of acne in adult women. Curr Derm Rep. 2014;3:29-39.

- Del Rosso JQ, Leyden JJ. Status report on antibiotic resistance: implications for the dermatologist. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:127-132.

- Bowe WP, Leyden JJ. Clinical implications of antibiotic resistance: risk of systemic infection from Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:125-133.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic drug interactions of clinical significance to dermatologists. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:91-94.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Keri J, Berson DS, Thiboutot DM. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:146-155.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on isotretinoin. AAD Web site. https://www.aad.org /Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. June 2012;7:CD004425.

- Sitruk-Ware R. Pharmacology of different progestogens: the special case of drospirenone. Climacteric. 2005;8 (suppl 3):4-12.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for the treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 2012;7:CD004425.

- Thiboutot D, Archer DF, Lemay A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-dose contraceptive containing 20 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 microg of levonogestrel for acne treatment. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:461-468.

- Koulianos GT. Treatment of acne with oral contraceptives: criteria for pill selection. Cutis. 2000;66:281-286.

- Rabe T, Kowald A, Ortmann J, et al. Inhibition of skin 5-alpha reductase by oral contraceptive progestins in vitro. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2000;14:223-230.

- Palli MB, Reyes-Habito CM, Lima XT, et al. A single-center, randomized double-blind, parallel-group study to examine the safety and efficacy of 3mg drospirenone/0.02mg ethinyl estradiol compared with placebo in the treatment of moderate truncal acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:633-637.

- Koltun W, Maloney JM, Marr J, et al. Treatment of moderate acne vulgaris using a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol 20 μg plus drospirenone 3 mg administered in a 24/4 regimen: a pooled analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:171-175.

- Maloney JM, Dietze P, Watson D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive containing 3 mg drospirenone plus 20 μg ethinylestradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: lesion counts, investigator ratings and subject self-assessment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:837-844.

- Lucky AW, Koltun W, Thiboutot D, et al. A combined oral contraceptive containing 3-mg drospirenone/20-μg ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating lesion counts and participant self-assessment. Cutis. 2008;82:143-150.

- Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(suppl 4):S5-S22.

- Maguire K, Westhoff C. The state of hormonal contraception today: established and emerging noncontraceptive health benefits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205 (suppl 4):S4-S8.

- Weiss NS, Sayvetz TA. Incidence of endometrial cancer in relation to the use of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:551-554.

- Tyler KH, Zirwas MJ. Contraception and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1022-1029.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD003987.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD010813.

- Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1039-1044.

- Jick SS, Hernandez RK. Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data. BMJ. 2011;342:d2151.

- US Food and Drug Administration Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs /Drug Safety/UCM277384.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. Technical Report Series 877.

- Frangos JE, Alavian CN, Kimball AB. Acne and oral contraceptives: update on women’s health screening guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:781-786.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

- Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Urrutia RP, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1931-1943.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16 573 women with cervical cancer and 35 509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1609-1621.

- Agostino H, Di Meglio G. Low-dose oral contraceptives in adolescents: how low can you go? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:195-201.

- Buzney E, Sheu J, Buzney C, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:859.e1-859.e15.

- Stewart FH, Harper CC, Ellertson CE, et al. Clinical breast and pelvic examination requirements for hormonal contraception: current practice vs evidence. JAMA. 2001;285:2232-2239.

- Sawaya ME, Somani N. Antiandrogens and androgen inhibitors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:361-374.

- Muhlemann MF, Carter GD, Cream JJ, et al. Oral spironolactone: an effective treatment for acne vulgaris in women. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:227-232.

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498-502.

- Sato K, Matsumoto D, Iizuka F, et al. Anti-androgenic therapy using oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in Asians. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30:689-694.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year follow-up study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:541-545.

- Stockley I. Antihypertensive drug interactions. In: Stockley I, ed. Drug Interactions. 5th ed. London, United Kingdom: Pharmaceutical Press; 1999:335-347.

- Antoniou T, Gomes T, Mamdani MM, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced hyperkalaemia in elderly patients receiving spironolactone: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5228.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Aldactone [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2008.

- Biggar RJ, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Spironolactone use and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:870-875.

- Mackenzie IS, Macdonald TM, Thompson A, et al. Spironolactone and risk of incident breast cancer in women older than 55 years: retrospective, matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4447.

- Dreno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in dermatology: limiting antibiotic use in acne. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:330-334.

- Kim S, Michaels BD, Kim GK, et al. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:61-97.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic therapy for acne vulgaris: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics perspectives. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:40-47.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotics. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:113-124.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral doxycycline in the management of acne vulgaris: current perspectives on clinical use and recent findings with a new double-scored small tablet formulation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:19-26.

- Osofsky MG, Strauss JS. Isotretinoin. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:134-145.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(suppl 2):S3-S21.

- Patton TJ, Ferris LK. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:252-268.

- Cakir GA, Erdogan FG, Gurler A. Isotretinoin treatment in nodulocystic acne with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: efficacy and determinants of relapse. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:371-376.

Selection of oral agents for treatment of AV in adult women is dependent on multiple factors including the patient’s age, medication history, child-bearing potential, clinical presentation, and treatment preference following a discussion of the anticipated benefits versus potential risks.1,2 In patients with the mixed inflammatory and comedonal clinical pattern of AV, oral antibiotics can be used concurrently with topical therapies when moderate to severe inflammatory lesions are noted.3,4 However, many adult women who had AV as teenagers have already utilized oral antibiotic therapies in the past and often are interested in alternative options, express concerns regarding antibiotic resistance, report a history of antibiotic-associated yeast infections or other side effects, and/or encounter issues related to drug-drug interactions.3,5-8 Oral hormonal therapies such as combination oral contraceptives (COCs) or spironolactone often are utilized to treat adult women with AV, sometimes in combination with each other or other agents. Combination oral contraceptives appear to be especially effective in the management of the U-shaped clinical pattern or predominantly inflammatory, late-onset AV.1,5,9,10 Potential warnings, contraindications, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions are important to keep in mind when considering the use of oral hormonal therapies.8-10 Oral isotretinoin, which should be prescribed with strict adherence to the iPLEDGE™ program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/), remains a viable option for cases of severe nodular AV and selected cases of refractory inflammatory AV, especially when scarring and/or marked psychosocial distress are noted.1,2,5,11 Although it is recognized that adult women with AV typically present with either a mixed inflammatory and comedonal or U-shaped clinical pattern predominantly involving the lower face and anterolateral neck, the available data do not adequately differentiate the relative responsiveness of these clinical patterns to specific therapeutic agents.

Combination Oral Contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives are commonly used to treat AV in adult women, including those without and those with measurable androgen excess (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]). Combination oral contraceptives contain ethinyl estradiol and a progestational agent (eg, progestin); the latter varies in terms of its nonselective receptor interactions and the relative magnitude or absence of androgenic effects.10,12,13 Although some COCs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AV, there is little data available to determine the comparative efficacy among these and other COCs.10,14 When choosing a COC for treatment of AV, it is best to select an agent whose effectiveness is supported by evidence from clinical studies.10,15

Mechanisms of Action

The reported mechanisms of action for COCs include inhibition of ovarian androgen production and ovulation through gonadotropin suppression; upregulated synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin, which decreases free testosterone levels through receptor binding; and inhibition of 5α-reductase (by some progestins), which reduces conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the active derivative that induces androgenic effects at peripheral target tissues.10,13,16,17

Therapeutic Benefits

Use of COCs to treat AV in adult women who do not have measurable androgen excess is most rational in patients who also desire a method of contraception. Multiple monotherapy studies have demonstrated the efficacy of COCs in the treatment of AV on the face and trunk.4,10,12,15,17,18 It may take a minimum of 3 monthly cycles of use before acne lesion counts begin to appreciably decrease.12,15,19-21 Initiating COC therapy during menstruation ensures the absence of pregnancy. Combination oral contraceptives may be used with other topical and oral therapies for AV.2,3,9,10 Potential ancillary benefits of COCs include normalization of the menstrual cycle; reduced premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms; and reduced risk of endometrial cancer (approximately 50%), ovarian cancer (approximately 40%), and colorectal cancer.22-24

Risks and Contraindications

It is important to consider the potential risks associated with the use of COCs, especially in women with AV who are not seeking a method of contraception. Side effects of COCs can include nausea, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding, and weight gain.25,26 Potential adverse associations of COCs are described in the Table. The major potential vascular associations include venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular accident, all of which are influenced by concurrent factors such as a history of smoking, age (≥35 years), and hypertension.27-32 It is recommended that blood pressure be measured before initiating COC therapy as part of the general examination.33

The potential increase in breast cancer risk appears to be low, while the cervical cancer risk is reported to increase relative to the duration of use.34-37 This latter observation may be due to the greater likelihood of unprotected sex in women using a COC and exposure to multiple sexual partners in some cases, which may increase the likelihood of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection of the cervix. If a dermatologist elects to prescribe a COC to treat AV, it has been suggested that the patient also consult with her general practitioner or gynecologist to undergo pelvic and breast examinations and a Papanicolaou test.33 The recommendation for initial screening for cervical cancer is within 3 years of initiation of sexual intercourse or by 21 years of age, whichever is first.33,38,39

Combination oral contraceptives are not ideal for all adult women with AV. Absolute contraindications are pregnancy and history of thromboembolic, cardiac, or hepatic disease; in women aged 35 years and older who smoke, relative contraindications include hypertension, diabetes, migraines, breastfeeding, and current breast or liver cancer.33 In adult women with AV who have relative contra-indications but are likely to benefit from the use of a COC when other options are limited or not viable, consultation with a gynecologist is prudent. Other than rifamycin antibiotics (eg, rifampin) and griseofulvin, there is no definitive evidence that oral antibiotics (eg, tetracycline) or oral antifungal agents reduce the contraceptive efficacy of COCs, although cautions remain in print within some approved package inserts.8

Spironolactone

Available since 1957, spironolactone is an oral aldos-terone antagonist and potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension and congestive heart failure.9 Recognition of its antiandrogenic effects led to its use in dermatology to treat certain dermatologic disorders in women (eg, hirsutism, alopecia, AV).1,4,5,9,10 Spironolactone is not approved for AV by the FDA; therefore, available data from multiple independent studies and retrospective analyses that have been collectively reviewed support its efficacy when used as both monotherapy or in combination with other agents in adult women with AV, especially those with a U-shaped pattern and/or late-onset AV.9,40-43

Mechanism of Action

Spironolactone inhibits sebaceous gland activity through peripheral androgen receptor blockade, inhibition of 5α-reductase, decrease in androgen production, and increase in sex hormone–binding globulin.9,10,40

Therapeutic Benefits

Good to excellent improvement of AV in women, many of whom are postadolescent, has ranged from 66% to 100% in published reports9,40-43; however, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dosing regimens, and concomitant therapies were not usually controlled. Spironolactone has been used to treat AV in adult women as monotherapy or in combination with topical agents, oral antibiotics, and COCs.9,40-42 Additionally, dose-ranging studies have not been completed with spironolactone for AV.9,40 The suggested dose range is 50 mg to 200 mg daily; however, it usually is best to start at 50 mg daily and increase to 100 mg daily if clinical response is not adequate after 2 to 3 months. The gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of spironolactone is increased when ingested with a high-fat meal.9,10

Once effective control of AV is achieved, it is optimal to use the lowest dose needed to continue reasonable suppression of new AV lesions. There is no defined end point for spironolactone use in AV, with or without concurrent PCOS, as many adult women usually continue treatment with low-dose therapy because they experience marked flaring shortly after the drug is stopped.9

Risks and Contraindications

Side effects associated with spironolactone are dose related and include increased diuresis, migraines, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, gynecomastia, fatigue, and dizziness.9,10,40-44 Side effects (particularly menstrual irregularities and breast tenderness) are more common at doses higher than 100 mg daily, especially when used as monotherapy without concurrent use of a COC.9,40

Spironolactone-associated hyperkalemia is most clinically relevant in patients on higher doses (eg, 100–200 mg daily), in those with renal impairment and/or congestive heart failure, and when used concurrently with certain other medications. In any patient on spironolactone, the risk of clinically relevant hyperkalemia may be increased by coingestion of potassium supplements, potassium-based salt substitutes, potassium-sparing diuretics (eg, amiloride, triamterene); aldosterone antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, lisinopril, benazepril); angiotensin II receptor blockers (eg, losartan, valsartan); and tri-methoprim (with or without sulfamethoxazole).8,9,40,45 Spironolactone may also increase serum levels of lithium or digoxin.9,40,45,46 For management of AV, it is best that spironolactone be avoided in patients taking any of these medications.9

In healthy adult women with AV who are not on medications or supplements that interact adversely with spironolactone, there is no definitive recommendation regarding monitoring of serum potassium levels during treatment with spironolactone, and it has been suggested that monitoring serum potassium levels in this subgroup is not necessary.47 However, each clinician is advised to choose whether or not they wish to obtain baseline and/or periodic serum potassium levels when prescribing spironolactone for AV based on their degree of comfort and the patient’s history. Baseline and periodic blood testing to evaluate serum electrolytes and renal function are reasonable, especially as adult women with AV are usually treated with spironolactone over a prolonged period of time.9

The FDA black box warning for spironolactone states that it is tumorigenic in chronic toxicity studies in rats and refers to exposures 25- to 100-fold higher than those administered to humans.9,48 Although continued vigilance is warranted, evaluation of large populations of women treated with spironolactone do not suggest an association with increased risk of breast cancer.49,50

Spironolactone is a category C drug and thus should be avoided during pregnancy, primarily due to animal data suggesting risks of hypospadias and feminization in male fetuses.9 Importantly, there is an absence of reports linking exposure during pregnancy with congenital defects in humans, including in 2 known cases of high-dose exposures for maternal Bartter syndrome.9

The active metabolite, canrenone, is known to be present in breast milk at 0.2% of the maternal daily dose, but breastfeeding is generally believed to be safe with spironolactone based on evidence to date.9

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotic therapy may be used in combination with a topical regimen to treat AV in adult women, keeping in mind some important caveats.1-7 For instance, monotherapy with oral antibiotics should be avoided, and concomitant use of benzoyl peroxide is suggested to reduce emergence of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes strains.3,4 A therapeutic exit plan also is suggested when prescribing oral antibiotics to limit treatment to 3 to 4 months, if possible, to help mitigate the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (eg, staphylococci and streptococci).3-5,51

Tetracyclines, especially doxycycline and minocycline, are the most commonly prescribed agents. Doxycycline use warrants patient education on measures to limit the risks of esophageal and GI side effects and phototoxicity; enteric-coated and small tablet formulations have been shown to reduce GI side effects, especially when administered with food.3,52-55 In addition to vestibular side effects and hyperpigmentation, minocycline may be associated with rare but potentially severe adverse reactions such as drug hypersensitivity syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, and lupus-like syndrome, which are reported more commonly in women.5,52,54 Vestibular side effects have been shown to decrease with use of extended-release tablets with weight-based dosing.53

Oral Isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin is well established as highly effective for treatment of severe, recalcitrant AV, including nodular acne on the face and trunk.4,56 Currently available oral isotretinoins are branded generic formulations based on the pharmacokinetic profile of the original brand (Accutane [Roche Pharmaceuticals]) and with the use of Lidose Technology (Absorica [Cipher Pharmaceuticals]), which substantially increases GI absorption of isotretinoin in the absence of ingestion with a high-calorie, high-fat meal.57 The short- and long-term efficacy, dosing regimens, safety considerations, and serious teratogenic risks for oral isotretinoin are well published.4,56-58 Importantly, oral isotretinoin must be prescribed with strict adherence to the federally mandated iPLEDGE risk management program.

Low-dose oral isotretinoin therapy (<0.5 mg/kg–1 mg/kg daily) administered over several months longer than conventional regimens (ie, 16–20 weeks) has been suggested with demonstrated efficacy.57 However, this approach is not optimal due to the lack of established sustained clearance of AV after discontinuation of therapy and the greater potential for exposure to isotretinoin during pregnancy. Recurrences of AV do occur after completion of isotretinoin therapy, especially if cumulative systemic exposure to the drug during the initial course of treatment was inadequate.56,57

Oral isotretinoin has been shown to be effective in AV in adult women with or without PCOS with 0.5 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg daily and a total cumulative exposure of 120 mg/kg to 150 mg/kg.59 In one study, the presence of PCOS and greater number of nodules at baseline were predictive of a higher risk of relapse during the second year posttreatment.59

Conclusion

All oral therapies that are used to treat AV in adult women warrant individual consideration of possible benefits versus risks. Careful attention to possible side effects, patient-related risk factors, and potential drug-drug interactions is important. End points of therapy are not well established, with the exception of oral isotretinoin therapy. Clinicians must use their judgment in each case along with obtaining feedback from patients regarding the selection of therapy after a discussion of the available options.

Selection of oral agents for treatment of AV in adult women is dependent on multiple factors including the patient’s age, medication history, child-bearing potential, clinical presentation, and treatment preference following a discussion of the anticipated benefits versus potential risks.1,2 In patients with the mixed inflammatory and comedonal clinical pattern of AV, oral antibiotics can be used concurrently with topical therapies when moderate to severe inflammatory lesions are noted.3,4 However, many adult women who had AV as teenagers have already utilized oral antibiotic therapies in the past and often are interested in alternative options, express concerns regarding antibiotic resistance, report a history of antibiotic-associated yeast infections or other side effects, and/or encounter issues related to drug-drug interactions.3,5-8 Oral hormonal therapies such as combination oral contraceptives (COCs) or spironolactone often are utilized to treat adult women with AV, sometimes in combination with each other or other agents. Combination oral contraceptives appear to be especially effective in the management of the U-shaped clinical pattern or predominantly inflammatory, late-onset AV.1,5,9,10 Potential warnings, contraindications, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions are important to keep in mind when considering the use of oral hormonal therapies.8-10 Oral isotretinoin, which should be prescribed with strict adherence to the iPLEDGE™ program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/), remains a viable option for cases of severe nodular AV and selected cases of refractory inflammatory AV, especially when scarring and/or marked psychosocial distress are noted.1,2,5,11 Although it is recognized that adult women with AV typically present with either a mixed inflammatory and comedonal or U-shaped clinical pattern predominantly involving the lower face and anterolateral neck, the available data do not adequately differentiate the relative responsiveness of these clinical patterns to specific therapeutic agents.

Combination Oral Contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives are commonly used to treat AV in adult women, including those without and those with measurable androgen excess (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]). Combination oral contraceptives contain ethinyl estradiol and a progestational agent (eg, progestin); the latter varies in terms of its nonselective receptor interactions and the relative magnitude or absence of androgenic effects.10,12,13 Although some COCs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AV, there is little data available to determine the comparative efficacy among these and other COCs.10,14 When choosing a COC for treatment of AV, it is best to select an agent whose effectiveness is supported by evidence from clinical studies.10,15

Mechanisms of Action

The reported mechanisms of action for COCs include inhibition of ovarian androgen production and ovulation through gonadotropin suppression; upregulated synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin, which decreases free testosterone levels through receptor binding; and inhibition of 5α-reductase (by some progestins), which reduces conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the active derivative that induces androgenic effects at peripheral target tissues.10,13,16,17

Therapeutic Benefits

Use of COCs to treat AV in adult women who do not have measurable androgen excess is most rational in patients who also desire a method of contraception. Multiple monotherapy studies have demonstrated the efficacy of COCs in the treatment of AV on the face and trunk.4,10,12,15,17,18 It may take a minimum of 3 monthly cycles of use before acne lesion counts begin to appreciably decrease.12,15,19-21 Initiating COC therapy during menstruation ensures the absence of pregnancy. Combination oral contraceptives may be used with other topical and oral therapies for AV.2,3,9,10 Potential ancillary benefits of COCs include normalization of the menstrual cycle; reduced premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms; and reduced risk of endometrial cancer (approximately 50%), ovarian cancer (approximately 40%), and colorectal cancer.22-24

Risks and Contraindications

It is important to consider the potential risks associated with the use of COCs, especially in women with AV who are not seeking a method of contraception. Side effects of COCs can include nausea, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding, and weight gain.25,26 Potential adverse associations of COCs are described in the Table. The major potential vascular associations include venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular accident, all of which are influenced by concurrent factors such as a history of smoking, age (≥35 years), and hypertension.27-32 It is recommended that blood pressure be measured before initiating COC therapy as part of the general examination.33

The potential increase in breast cancer risk appears to be low, while the cervical cancer risk is reported to increase relative to the duration of use.34-37 This latter observation may be due to the greater likelihood of unprotected sex in women using a COC and exposure to multiple sexual partners in some cases, which may increase the likelihood of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection of the cervix. If a dermatologist elects to prescribe a COC to treat AV, it has been suggested that the patient also consult with her general practitioner or gynecologist to undergo pelvic and breast examinations and a Papanicolaou test.33 The recommendation for initial screening for cervical cancer is within 3 years of initiation of sexual intercourse or by 21 years of age, whichever is first.33,38,39

Combination oral contraceptives are not ideal for all adult women with AV. Absolute contraindications are pregnancy and history of thromboembolic, cardiac, or hepatic disease; in women aged 35 years and older who smoke, relative contraindications include hypertension, diabetes, migraines, breastfeeding, and current breast or liver cancer.33 In adult women with AV who have relative contra-indications but are likely to benefit from the use of a COC when other options are limited or not viable, consultation with a gynecologist is prudent. Other than rifamycin antibiotics (eg, rifampin) and griseofulvin, there is no definitive evidence that oral antibiotics (eg, tetracycline) or oral antifungal agents reduce the contraceptive efficacy of COCs, although cautions remain in print within some approved package inserts.8

Spironolactone

Available since 1957, spironolactone is an oral aldos-terone antagonist and potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension and congestive heart failure.9 Recognition of its antiandrogenic effects led to its use in dermatology to treat certain dermatologic disorders in women (eg, hirsutism, alopecia, AV).1,4,5,9,10 Spironolactone is not approved for AV by the FDA; therefore, available data from multiple independent studies and retrospective analyses that have been collectively reviewed support its efficacy when used as both monotherapy or in combination with other agents in adult women with AV, especially those with a U-shaped pattern and/or late-onset AV.9,40-43

Mechanism of Action

Spironolactone inhibits sebaceous gland activity through peripheral androgen receptor blockade, inhibition of 5α-reductase, decrease in androgen production, and increase in sex hormone–binding globulin.9,10,40

Therapeutic Benefits

Good to excellent improvement of AV in women, many of whom are postadolescent, has ranged from 66% to 100% in published reports9,40-43; however, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dosing regimens, and concomitant therapies were not usually controlled. Spironolactone has been used to treat AV in adult women as monotherapy or in combination with topical agents, oral antibiotics, and COCs.9,40-42 Additionally, dose-ranging studies have not been completed with spironolactone for AV.9,40 The suggested dose range is 50 mg to 200 mg daily; however, it usually is best to start at 50 mg daily and increase to 100 mg daily if clinical response is not adequate after 2 to 3 months. The gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of spironolactone is increased when ingested with a high-fat meal.9,10

Once effective control of AV is achieved, it is optimal to use the lowest dose needed to continue reasonable suppression of new AV lesions. There is no defined end point for spironolactone use in AV, with or without concurrent PCOS, as many adult women usually continue treatment with low-dose therapy because they experience marked flaring shortly after the drug is stopped.9

Risks and Contraindications

Side effects associated with spironolactone are dose related and include increased diuresis, migraines, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, gynecomastia, fatigue, and dizziness.9,10,40-44 Side effects (particularly menstrual irregularities and breast tenderness) are more common at doses higher than 100 mg daily, especially when used as monotherapy without concurrent use of a COC.9,40

Spironolactone-associated hyperkalemia is most clinically relevant in patients on higher doses (eg, 100–200 mg daily), in those with renal impairment and/or congestive heart failure, and when used concurrently with certain other medications. In any patient on spironolactone, the risk of clinically relevant hyperkalemia may be increased by coingestion of potassium supplements, potassium-based salt substitutes, potassium-sparing diuretics (eg, amiloride, triamterene); aldosterone antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, lisinopril, benazepril); angiotensin II receptor blockers (eg, losartan, valsartan); and tri-methoprim (with or without sulfamethoxazole).8,9,40,45 Spironolactone may also increase serum levels of lithium or digoxin.9,40,45,46 For management of AV, it is best that spironolactone be avoided in patients taking any of these medications.9

In healthy adult women with AV who are not on medications or supplements that interact adversely with spironolactone, there is no definitive recommendation regarding monitoring of serum potassium levels during treatment with spironolactone, and it has been suggested that monitoring serum potassium levels in this subgroup is not necessary.47 However, each clinician is advised to choose whether or not they wish to obtain baseline and/or periodic serum potassium levels when prescribing spironolactone for AV based on their degree of comfort and the patient’s history. Baseline and periodic blood testing to evaluate serum electrolytes and renal function are reasonable, especially as adult women with AV are usually treated with spironolactone over a prolonged period of time.9

The FDA black box warning for spironolactone states that it is tumorigenic in chronic toxicity studies in rats and refers to exposures 25- to 100-fold higher than those administered to humans.9,48 Although continued vigilance is warranted, evaluation of large populations of women treated with spironolactone do not suggest an association with increased risk of breast cancer.49,50

Spironolactone is a category C drug and thus should be avoided during pregnancy, primarily due to animal data suggesting risks of hypospadias and feminization in male fetuses.9 Importantly, there is an absence of reports linking exposure during pregnancy with congenital defects in humans, including in 2 known cases of high-dose exposures for maternal Bartter syndrome.9

The active metabolite, canrenone, is known to be present in breast milk at 0.2% of the maternal daily dose, but breastfeeding is generally believed to be safe with spironolactone based on evidence to date.9

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotic therapy may be used in combination with a topical regimen to treat AV in adult women, keeping in mind some important caveats.1-7 For instance, monotherapy with oral antibiotics should be avoided, and concomitant use of benzoyl peroxide is suggested to reduce emergence of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes strains.3,4 A therapeutic exit plan also is suggested when prescribing oral antibiotics to limit treatment to 3 to 4 months, if possible, to help mitigate the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (eg, staphylococci and streptococci).3-5,51

Tetracyclines, especially doxycycline and minocycline, are the most commonly prescribed agents. Doxycycline use warrants patient education on measures to limit the risks of esophageal and GI side effects and phototoxicity; enteric-coated and small tablet formulations have been shown to reduce GI side effects, especially when administered with food.3,52-55 In addition to vestibular side effects and hyperpigmentation, minocycline may be associated with rare but potentially severe adverse reactions such as drug hypersensitivity syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, and lupus-like syndrome, which are reported more commonly in women.5,52,54 Vestibular side effects have been shown to decrease with use of extended-release tablets with weight-based dosing.53

Oral Isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin is well established as highly effective for treatment of severe, recalcitrant AV, including nodular acne on the face and trunk.4,56 Currently available oral isotretinoins are branded generic formulations based on the pharmacokinetic profile of the original brand (Accutane [Roche Pharmaceuticals]) and with the use of Lidose Technology (Absorica [Cipher Pharmaceuticals]), which substantially increases GI absorption of isotretinoin in the absence of ingestion with a high-calorie, high-fat meal.57 The short- and long-term efficacy, dosing regimens, safety considerations, and serious teratogenic risks for oral isotretinoin are well published.4,56-58 Importantly, oral isotretinoin must be prescribed with strict adherence to the federally mandated iPLEDGE risk management program.

Low-dose oral isotretinoin therapy (<0.5 mg/kg–1 mg/kg daily) administered over several months longer than conventional regimens (ie, 16–20 weeks) has been suggested with demonstrated efficacy.57 However, this approach is not optimal due to the lack of established sustained clearance of AV after discontinuation of therapy and the greater potential for exposure to isotretinoin during pregnancy. Recurrences of AV do occur after completion of isotretinoin therapy, especially if cumulative systemic exposure to the drug during the initial course of treatment was inadequate.56,57

Oral isotretinoin has been shown to be effective in AV in adult women with or without PCOS with 0.5 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg daily and a total cumulative exposure of 120 mg/kg to 150 mg/kg.59 In one study, the presence of PCOS and greater number of nodules at baseline were predictive of a higher risk of relapse during the second year posttreatment.59

Conclusion

All oral therapies that are used to treat AV in adult women warrant individual consideration of possible benefits versus risks. Careful attention to possible side effects, patient-related risk factors, and potential drug-drug interactions is important. End points of therapy are not well established, with the exception of oral isotretinoin therapy. Clinicians must use their judgment in each case along with obtaining feedback from patients regarding the selection of therapy after a discussion of the available options.

- Holzmann R, Shakery K. Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(suppl 1):3-8.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Treatment guidelines in adult women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:198-207.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kim G. Optimizing use of oral antibiotics in acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:33-42.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Fisk WA, Lev-Tov HA, Sivamani RK. Epidemiology and management of acne in adult women. Curr Derm Rep. 2014;3:29-39.

- Del Rosso JQ, Leyden JJ. Status report on antibiotic resistance: implications for the dermatologist. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:127-132.

- Bowe WP, Leyden JJ. Clinical implications of antibiotic resistance: risk of systemic infection from Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:125-133.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic drug interactions of clinical significance to dermatologists. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:91-94.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Keri J, Berson DS, Thiboutot DM. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:146-155.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on isotretinoin. AAD Web site. https://www.aad.org /Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. June 2012;7:CD004425.

- Sitruk-Ware R. Pharmacology of different progestogens: the special case of drospirenone. Climacteric. 2005;8 (suppl 3):4-12.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for the treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 2012;7:CD004425.

- Thiboutot D, Archer DF, Lemay A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-dose contraceptive containing 20 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 microg of levonogestrel for acne treatment. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:461-468.

- Koulianos GT. Treatment of acne with oral contraceptives: criteria for pill selection. Cutis. 2000;66:281-286.

- Rabe T, Kowald A, Ortmann J, et al. Inhibition of skin 5-alpha reductase by oral contraceptive progestins in vitro. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2000;14:223-230.

- Palli MB, Reyes-Habito CM, Lima XT, et al. A single-center, randomized double-blind, parallel-group study to examine the safety and efficacy of 3mg drospirenone/0.02mg ethinyl estradiol compared with placebo in the treatment of moderate truncal acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:633-637.

- Koltun W, Maloney JM, Marr J, et al. Treatment of moderate acne vulgaris using a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol 20 μg plus drospirenone 3 mg administered in a 24/4 regimen: a pooled analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:171-175.

- Maloney JM, Dietze P, Watson D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive containing 3 mg drospirenone plus 20 μg ethinylestradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: lesion counts, investigator ratings and subject self-assessment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:837-844.

- Lucky AW, Koltun W, Thiboutot D, et al. A combined oral contraceptive containing 3-mg drospirenone/20-μg ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating lesion counts and participant self-assessment. Cutis. 2008;82:143-150.

- Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(suppl 4):S5-S22.

- Maguire K, Westhoff C. The state of hormonal contraception today: established and emerging noncontraceptive health benefits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205 (suppl 4):S4-S8.

- Weiss NS, Sayvetz TA. Incidence of endometrial cancer in relation to the use of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:551-554.

- Tyler KH, Zirwas MJ. Contraception and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1022-1029.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD003987.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD010813.

- Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1039-1044.

- Jick SS, Hernandez RK. Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data. BMJ. 2011;342:d2151.

- US Food and Drug Administration Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs /Drug Safety/UCM277384.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. Technical Report Series 877.

- Frangos JE, Alavian CN, Kimball AB. Acne and oral contraceptives: update on women’s health screening guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:781-786.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

- Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Urrutia RP, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1931-1943.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16 573 women with cervical cancer and 35 509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1609-1621.

- Agostino H, Di Meglio G. Low-dose oral contraceptives in adolescents: how low can you go? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:195-201.

- Buzney E, Sheu J, Buzney C, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:859.e1-859.e15.

- Stewart FH, Harper CC, Ellertson CE, et al. Clinical breast and pelvic examination requirements for hormonal contraception: current practice vs evidence. JAMA. 2001;285:2232-2239.

- Sawaya ME, Somani N. Antiandrogens and androgen inhibitors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:361-374.

- Muhlemann MF, Carter GD, Cream JJ, et al. Oral spironolactone: an effective treatment for acne vulgaris in women. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:227-232.

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498-502.

- Sato K, Matsumoto D, Iizuka F, et al. Anti-androgenic therapy using oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in Asians. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30:689-694.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year follow-up study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:541-545.

- Stockley I. Antihypertensive drug interactions. In: Stockley I, ed. Drug Interactions. 5th ed. London, United Kingdom: Pharmaceutical Press; 1999:335-347.

- Antoniou T, Gomes T, Mamdani MM, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced hyperkalaemia in elderly patients receiving spironolactone: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5228.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Aldactone [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2008.

- Biggar RJ, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Spironolactone use and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:870-875.

- Mackenzie IS, Macdonald TM, Thompson A, et al. Spironolactone and risk of incident breast cancer in women older than 55 years: retrospective, matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4447.

- Dreno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in dermatology: limiting antibiotic use in acne. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:330-334.

- Kim S, Michaels BD, Kim GK, et al. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:61-97.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic therapy for acne vulgaris: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics perspectives. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:40-47.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotics. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:113-124.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral doxycycline in the management of acne vulgaris: current perspectives on clinical use and recent findings with a new double-scored small tablet formulation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:19-26.

- Osofsky MG, Strauss JS. Isotretinoin. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:134-145.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(suppl 2):S3-S21.

- Patton TJ, Ferris LK. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:252-268.

- Cakir GA, Erdogan FG, Gurler A. Isotretinoin treatment in nodulocystic acne with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: efficacy and determinants of relapse. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:371-376.

- Holzmann R, Shakery K. Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(suppl 1):3-8.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Treatment guidelines in adult women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:198-207.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kim G. Optimizing use of oral antibiotics in acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:33-42.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Fisk WA, Lev-Tov HA, Sivamani RK. Epidemiology and management of acne in adult women. Curr Derm Rep. 2014;3:29-39.

- Del Rosso JQ, Leyden JJ. Status report on antibiotic resistance: implications for the dermatologist. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:127-132.

- Bowe WP, Leyden JJ. Clinical implications of antibiotic resistance: risk of systemic infection from Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:125-133.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic drug interactions of clinical significance to dermatologists. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:91-94.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Keri J, Berson DS, Thiboutot DM. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:146-155.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on isotretinoin. AAD Web site. https://www.aad.org /Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. June 2012;7:CD004425.

- Sitruk-Ware R. Pharmacology of different progestogens: the special case of drospirenone. Climacteric. 2005;8 (suppl 3):4-12.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for the treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 2012;7:CD004425.

- Thiboutot D, Archer DF, Lemay A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-dose contraceptive containing 20 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 microg of levonogestrel for acne treatment. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:461-468.

- Koulianos GT. Treatment of acne with oral contraceptives: criteria for pill selection. Cutis. 2000;66:281-286.

- Rabe T, Kowald A, Ortmann J, et al. Inhibition of skin 5-alpha reductase by oral contraceptive progestins in vitro. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2000;14:223-230.

- Palli MB, Reyes-Habito CM, Lima XT, et al. A single-center, randomized double-blind, parallel-group study to examine the safety and efficacy of 3mg drospirenone/0.02mg ethinyl estradiol compared with placebo in the treatment of moderate truncal acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:633-637.

- Koltun W, Maloney JM, Marr J, et al. Treatment of moderate acne vulgaris using a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol 20 μg plus drospirenone 3 mg administered in a 24/4 regimen: a pooled analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:171-175.

- Maloney JM, Dietze P, Watson D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive containing 3 mg drospirenone plus 20 μg ethinylestradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: lesion counts, investigator ratings and subject self-assessment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:837-844.

- Lucky AW, Koltun W, Thiboutot D, et al. A combined oral contraceptive containing 3-mg drospirenone/20-μg ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating lesion counts and participant self-assessment. Cutis. 2008;82:143-150.

- Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(suppl 4):S5-S22.

- Maguire K, Westhoff C. The state of hormonal contraception today: established and emerging noncontraceptive health benefits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205 (suppl 4):S4-S8.

- Weiss NS, Sayvetz TA. Incidence of endometrial cancer in relation to the use of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:551-554.

- Tyler KH, Zirwas MJ. Contraception and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1022-1029.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD003987.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD010813.

- Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1039-1044.

- Jick SS, Hernandez RK. Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data. BMJ. 2011;342:d2151.

- US Food and Drug Administration Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs /Drug Safety/UCM277384.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. Technical Report Series 877.

- Frangos JE, Alavian CN, Kimball AB. Acne and oral contraceptives: update on women’s health screening guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:781-786.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

- Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Urrutia RP, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1931-1943.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16 573 women with cervical cancer and 35 509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1609-1621.

- Agostino H, Di Meglio G. Low-dose oral contraceptives in adolescents: how low can you go? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:195-201.

- Buzney E, Sheu J, Buzney C, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:859.e1-859.e15.

- Stewart FH, Harper CC, Ellertson CE, et al. Clinical breast and pelvic examination requirements for hormonal contraception: current practice vs evidence. JAMA. 2001;285:2232-2239.

- Sawaya ME, Somani N. Antiandrogens and androgen inhibitors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:361-374.

- Muhlemann MF, Carter GD, Cream JJ, et al. Oral spironolactone: an effective treatment for acne vulgaris in women. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:227-232.

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498-502.

- Sato K, Matsumoto D, Iizuka F, et al. Anti-androgenic therapy using oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in Asians. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30:689-694.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year follow-up study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:541-545.

- Stockley I. Antihypertensive drug interactions. In: Stockley I, ed. Drug Interactions. 5th ed. London, United Kingdom: Pharmaceutical Press; 1999:335-347.

- Antoniou T, Gomes T, Mamdani MM, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced hyperkalaemia in elderly patients receiving spironolactone: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5228.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Aldactone [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2008.

- Biggar RJ, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Spironolactone use and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:870-875.

- Mackenzie IS, Macdonald TM, Thompson A, et al. Spironolactone and risk of incident breast cancer in women older than 55 years: retrospective, matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4447.

- Dreno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in dermatology: limiting antibiotic use in acne. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:330-334.

- Kim S, Michaels BD, Kim GK, et al. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:61-97.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic therapy for acne vulgaris: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics perspectives. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:40-47.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotics. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:113-124.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral doxycycline in the management of acne vulgaris: current perspectives on clinical use and recent findings with a new double-scored small tablet formulation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:19-26.

- Osofsky MG, Strauss JS. Isotretinoin. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:134-145.

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Baum EW. The use of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: clinical considerations and future directions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(suppl 2):S3-S21.

- Patton TJ, Ferris LK. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:252-268.

- Cakir GA, Erdogan FG, Gurler A. Isotretinoin treatment in nodulocystic acne with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: efficacy and determinants of relapse. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:371-376.

Practice Points

- Use of combination oral contraceptives to treat acne vulgaris (AV) in adult women who do not have measurable androgen excess is most rational in patients who also desire a method of contraception.

- Spironolactone is widely accepted as an oral agent that can be effective in treating adult women with AV and may be used in combination with other therapies.