User login

Annual Skin Check: Examining the Dermatology Headlines of 2019

From chemical sunscreen to the measles outbreak and drug approvals to product recalls, dermatology experienced its share of firsts and controversies in 2019.

Chemical Sunscreen Controversies

Controversial concerns about the effects of chemical sunscreen on coral reefs took an unprecedented turn in the United States this last year. On February 5, 2019, an ordinance was passed in Key West, Florida, prohibiting the sale of sunscreen containing the organic UV filters oxybenzone and/or octinoxate within city limits.1 On June 25, 2019, a similar law that also included octocrylene was passed in the US Virgin Islands.2 In so doing, these areas joined Hawaii, the Republic of Palau, and parts of Mexico in restricting chemical sunscreen sales.1 Although the Key West ordinance is set to take effect in January 2021, opponents, including dermatologists who believe it will discourage sunscreen use, currently are trying to overturn the ban.3 In the US Virgin Islands, part of the ban went into effect in September 2019, with the rest of the ban set to start in March 2020.2 Companies have started to follow suit. On August 1, 2019, CVS Pharmacy announced that, by the end of 2020, it will remove oxybenzone and octinoxate from some of its store-brand chemical sunscreens.4

On February 26, 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed that there are insufficient data to determine if 12 organic UV filters—including the aforementioned oxybenzone, octinoxate, and octocrylene—are generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE).5 Although these ingredients were listed as GRASE by the FDA in 2011, the rise in sunscreen use since then, as well as changes in sunscreen formulations, prompted the FDA to ask manufacturers to perform additional studies on safety parameters such as systemic absorption.5,6 One study conducted by the FDA itself was published in May 2019 and showed that maximal use of 4 sunscreens resulted in systemic absorption of 4 organic UV filters above 0.5 ng/mL, the FDA’s threshold for requiring nonclinical toxicology assessment. The study authors concluded that “further studies [are needed] to determine the clinical significance of these findings. [But] These results do not indicate that individuals should refrain from the use of

End of the New York City Measles Outbreak

On September 3, 2019, New York City’s largest measles outbreak in nearly 30 years was declared over. This announcement reflected the fact that 2 incubation periods for measles—42 days—had passed since the last measles patient was considered contagious. In total, there were 654 cases of measles and 52 associated hospitalizations, including 16 admissions to the intensive care unit. Most patients were younger than 18 years and unvaccinated.8

The outbreak began in October 2018 after Orthodox Jewish children from Brooklyn became infected while visiting Israel and imported the measles virus upon their return home.8,9 All 5 boroughs in New York City were ultimately affected, although 4 zip codes in Williamsburg, a neighborhood in Brooklyn with an undervaccinated Orthodox Jewish community, accounted for 72% of cases.8,10 As part of a $6 million effort to stop the outbreak, an emergency order was placed on these 4 zip codes, posing potential fines on people living or working there if they were unvaccinated.8 In addition, a bill was passed and signed into law in New York State that eliminated religious exemptions for immunizations.11 In collaboration with Jewish leaders, these efforts increased the administration of measles-mumps-rubella vaccines by 41% compared with the year before in Williamsburg and Borough Park, another heavily Orthodox Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn.8

Drug Approvals for Pediatric Dermatology

On March 11, 2019, the IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor dupilumab became the third biologic with a pediatric dermatology indication when the FDA extended its approval to adolescents for the treatment of atopic dermatitis.12 The FDA approval was based on a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 42% (34/82) of adolescents treated with dupilumab monotherapy every other week achieved 75% or more improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at week 16 compared with 8% (7/85) in the placebo group (P<.001).13

In October 2019, trifarotene cream and minocycline foam were approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne in patients 9 years and older.14,15 As such, both became the first acne therapies to include patients as young as 9 years in their studies and indication—a milestone, considering the fact that children have historically been excluded from clinical trials.16 The 2 topical treatments also are noteworthy for being first in class: trifarotene cream is the only topical retinoid to selectively target the retinoic acid receptor γ and to have been studied specifically for both facial and truncal acne,14,17 and minocycline foam is the first topical tetracycline.15

Drug Approvals for Rare Dermatologic Diseases

On July 19, 2019, apremilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, became the first medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of adults with oral ulcers due to Behçet disease, a rare multisystem inflammatory disease.18 The FDA approval was based on a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which 53% (55/104) of patients receiving apremilast monotherapy were ulcer free at week 12 compared to 22% (23/103) receiving placebo (P<.0001)(ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02307513).19

On October 8, 2019, afamelanotide was approved by the FDA to increase pain-free light exposure in adults with erythropoietic protoporphyria, a rare metabolic disorder associated with photosensitivity.20 A melanocortin receptor agonist, afamelanotide is believed to confer photoprotection by increasing the production of eumelanin in the epidermis. The FDA approval was based on 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, both of which found that patients given afamelanotide spent significantly more time in direct sunlight without pain compared to patients in the placebo group (P=.005 and P=.04).21

Recalls of Popular Skin Products

On July 5, 2019, Neutrogena recalled its cult-favorite Light Therapy Acne Mask. The recall was driven by rare reports of transient visual side effects due to insufficient eye protection from the mask’s light-emitting diodes.22,23 Reported in association with 0.02% of masks sold at the time of the recall, these side effects included eye pain, irritation, tearing, blurry vision, seeing spots, and changes in color vision.24 In addition, a risk for potentially irreversible eye injury from the mask was cited in people taking photosensitizing medications, such as doxycycline, and people with certain underlying eye conditions, such as retinitis pigmentosa and ocular albinism.22,24,25

Following decades of asbestos-related controversy, 1 lot of the iconic Johnson’s Baby Powder was recalled for the first time on October 18, 2019, after the FDA found subtrace levels of asbestos in 1 of the lot’s bottles.26 After the recall, Johnson & Johnson reported that 2 third-party laboratories did not ultimately find asbestos when they tested the bottle of interest as well as other bottles from the recalled lot. Three of 5 samples prepared in 1 room by the third-party laboratories initially did test positive for asbestos, but this result was attributed to the room’s air conditioner, which was found to be contaminated with asbestos. When the same samples were prepared in another room, no asbestos was detected.27 The FDA maintained there was “no indication of cross-contamination” when they originally tested the implicated bottle.28

- Zraick K. Key West bans sunscreen containing chemicals believed to harm coral reefs. New York Times. February 7, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/us/sunscreen-coral-reef-key-west.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Gies H. The U.S. Virigin Islands becomes the first American jurisdiction to ban common chemical sunscreens. Pacific Standard. July 18, 2019. https://psmag.com/environment/sunscreen-is-corals-biggest-anemone. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Luscombe R. Republicans seek to overturn Key West ban on coral-damaging sunscreens. The Guardian. November 9, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/09/key-west-sunscreen-coral-reef-backlash-skin-cancer. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Salazar D. CVS to remove 2 chemicals from 60 store-brand sunscreens. Drug Store News. August 2, 2019. https://drugstorenews.com/retail-news/cvs-to-remove-2-chemicals-from-60-store-brand-sunscreens. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2019;84(38):6204-6275. To be codified at 21 CFR §201, 310, 347, and 352.

- DeLeo VA. Sunscreen regulations and advice for your patients. Cutis. 2019;103:251-253.

- Matta MK, Zusterzeel R, Pilli NR, et al. Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2082-2091.

- Mayor de Blasio, health officials declare end of measles outbreak in New York City [news release]. New York, NY: City of New York; September 3, 2019. https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/409-19/mayor-de-blasio-health-officials-declare-end-measles-outbreak-new-york-city. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Health department reports eleven new cases of measles in Brooklyn’s Orthodox Jewish community, urges on time vaccination for all children, especially before traveling to Israel and other countries experiencing measles outbreaks [news release]. New York, NY: City of New York; November 2, 2018. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/about/press/pr2018/pr091-18.page. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles elimination. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/elimination.html. Updated October 4, 2019. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- McKinley J. Measles outbreak: N.Y. eliminates religious exemptions for vaccinations. New York Times. June 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/13/nyregion/measles-vaccinations-new-york.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- FDA approves Dupixent® (dupilumab) for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adolescents [news release]. Cambridge, MA: Sanofi; March 11, 2019. http://www.news.sanofi.us/2019-03-11-FDA-approves-Dupixent-R-dupilumab-for-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-in-adolescents. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial [published online ahead of print November 6, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336.

- Galderma receives FDA approval for AKLIEF® (trifarotene) cream, 0.005%, the first new retinoid molecule for the treatment of acne in over 20 years [news release]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; October 4, 2019. https://www.multivu.com/players/English/8613051-galderma-aklief-retinoid-molecule-acne-treatment/. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Update—Foamix receives FDA approval of AMZEEQ™ topical minocycline treatment for millions of moderate to severe acne sufferers [news release]. Bridgewater, NJ: Foamix Pharmaceuticals Ltd; October 18, 2019. http://www.foamix.com/news-releases/news-release-details/update-foamix-receives-fda-approval-amzeeqtm-topical-minocycline. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Redfearn S. Clinical trial patient inclusion and exclusion criteria need an overhaul, say experts. CenterWatch website. April 23, 2018. https://www.centerwatch.com/cwweekly/2018/04/23/clinical-trial-patient-inclusion-and-exclusion-criteria-need-an-overhaul-say-experts. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Tan J, Thiboutot D, Popp G, et al. Randomized phase 3 evaluation of trifarotene 50 mug/g cream treatment of moderate facial and truncal acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1691-1699.

- FDA approves OTEZLA® (apremilast) for the treatment of oral ulcers associated with Behçet’s disease [news release]. Summit, NJ: Celgene; July 19, 2019. https://ir.celgene.com/press-releases/press-release-details/2019/FDA-Approves-OTEZLA-apremilast-for-the-Treatment-of-Oral-Ulcers-Associated-with-Behets-Disease/default.aspx. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Apremilast [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2019.

- FDA approves first treatment to increase pain-free light exposure in patients with a rare disorder [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; October 8, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-increase-pain-free-light-exposure-patients-rare-disorder. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Langendonk JG, Balwani M, Anderson KE, et al. Afamelanotide for erythropoietic protoporphyria. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:48-59.

- Light Therapy Mask recall statement. Neutrogena website. https://www.neutrogena.com/light-therapy-statement.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Bromwich JE. Neutrogena recalls Light Therapy Masks, citing risk of eye injury. New York Times. July 18, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/style/neutrogena-light-therapy-mask-recall.html. Accessed December 23, 2019, 2019.

- Nguyen T. Neutrogena recalls acne mask over concerns about blue light. Chemical & Engineering News. August 6, 2019. https://cen.acs.org/safety/lab-safety/Neutrogena-recalls-acne-mask-over-concerns-about-blue-light/97/web/2019/08. Accessed November 16, 2019.

- Australian Government Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Neutrogena Visibly Clear Light Therapy Acne Mask and Activator: Recall - potential for eye damage. https://www.tga.gov.au/alert/neutrogena-visibly-clear-light-therapy-acne-mask-and-activator. Published July 17, 2019. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc. to voluntarily recall a single lot of Johnson’s Baby Powder in the United States [press release]. New Brunswick, NJ: Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc; October 18, 2019. https://www.factsabouttalc.com/_document/15-new-tests-from-the-same-bottle-of-johnsons-baby-powder-previously-tested-by-fda-find-no-asbestos?id=0000016e-1915-dc68-af7e-df3f147c0000. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- 15 new tests from the same bottle of Johnson’s Baby Powder previously tested by FDA find no asbestos [press release]. New Brunswick, NJ: Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc; October 29, 2019. https://www.factsabouttalc.com/_document/johnson-johnson-consumer-inc-to-voluntarily-recall-a-single-lot-of-johnsons-baby-powder-in-the-united-states?id=0000016d-debf-d71d-a77d-dfbfebeb0000. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Hsu T. Johnson & Johnson says recalled baby powder doesn’t have asbestos. New York Times. October 29, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/29/business/johnson-baby-powder-asbestos.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

From chemical sunscreen to the measles outbreak and drug approvals to product recalls, dermatology experienced its share of firsts and controversies in 2019.

Chemical Sunscreen Controversies

Controversial concerns about the effects of chemical sunscreen on coral reefs took an unprecedented turn in the United States this last year. On February 5, 2019, an ordinance was passed in Key West, Florida, prohibiting the sale of sunscreen containing the organic UV filters oxybenzone and/or octinoxate within city limits.1 On June 25, 2019, a similar law that also included octocrylene was passed in the US Virgin Islands.2 In so doing, these areas joined Hawaii, the Republic of Palau, and parts of Mexico in restricting chemical sunscreen sales.1 Although the Key West ordinance is set to take effect in January 2021, opponents, including dermatologists who believe it will discourage sunscreen use, currently are trying to overturn the ban.3 In the US Virgin Islands, part of the ban went into effect in September 2019, with the rest of the ban set to start in March 2020.2 Companies have started to follow suit. On August 1, 2019, CVS Pharmacy announced that, by the end of 2020, it will remove oxybenzone and octinoxate from some of its store-brand chemical sunscreens.4

On February 26, 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed that there are insufficient data to determine if 12 organic UV filters—including the aforementioned oxybenzone, octinoxate, and octocrylene—are generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE).5 Although these ingredients were listed as GRASE by the FDA in 2011, the rise in sunscreen use since then, as well as changes in sunscreen formulations, prompted the FDA to ask manufacturers to perform additional studies on safety parameters such as systemic absorption.5,6 One study conducted by the FDA itself was published in May 2019 and showed that maximal use of 4 sunscreens resulted in systemic absorption of 4 organic UV filters above 0.5 ng/mL, the FDA’s threshold for requiring nonclinical toxicology assessment. The study authors concluded that “further studies [are needed] to determine the clinical significance of these findings. [But] These results do not indicate that individuals should refrain from the use of

End of the New York City Measles Outbreak

On September 3, 2019, New York City’s largest measles outbreak in nearly 30 years was declared over. This announcement reflected the fact that 2 incubation periods for measles—42 days—had passed since the last measles patient was considered contagious. In total, there were 654 cases of measles and 52 associated hospitalizations, including 16 admissions to the intensive care unit. Most patients were younger than 18 years and unvaccinated.8

The outbreak began in October 2018 after Orthodox Jewish children from Brooklyn became infected while visiting Israel and imported the measles virus upon their return home.8,9 All 5 boroughs in New York City were ultimately affected, although 4 zip codes in Williamsburg, a neighborhood in Brooklyn with an undervaccinated Orthodox Jewish community, accounted for 72% of cases.8,10 As part of a $6 million effort to stop the outbreak, an emergency order was placed on these 4 zip codes, posing potential fines on people living or working there if they were unvaccinated.8 In addition, a bill was passed and signed into law in New York State that eliminated religious exemptions for immunizations.11 In collaboration with Jewish leaders, these efforts increased the administration of measles-mumps-rubella vaccines by 41% compared with the year before in Williamsburg and Borough Park, another heavily Orthodox Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn.8

Drug Approvals for Pediatric Dermatology

On March 11, 2019, the IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor dupilumab became the third biologic with a pediatric dermatology indication when the FDA extended its approval to adolescents for the treatment of atopic dermatitis.12 The FDA approval was based on a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 42% (34/82) of adolescents treated with dupilumab monotherapy every other week achieved 75% or more improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at week 16 compared with 8% (7/85) in the placebo group (P<.001).13

In October 2019, trifarotene cream and minocycline foam were approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne in patients 9 years and older.14,15 As such, both became the first acne therapies to include patients as young as 9 years in their studies and indication—a milestone, considering the fact that children have historically been excluded from clinical trials.16 The 2 topical treatments also are noteworthy for being first in class: trifarotene cream is the only topical retinoid to selectively target the retinoic acid receptor γ and to have been studied specifically for both facial and truncal acne,14,17 and minocycline foam is the first topical tetracycline.15

Drug Approvals for Rare Dermatologic Diseases

On July 19, 2019, apremilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, became the first medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of adults with oral ulcers due to Behçet disease, a rare multisystem inflammatory disease.18 The FDA approval was based on a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which 53% (55/104) of patients receiving apremilast monotherapy were ulcer free at week 12 compared to 22% (23/103) receiving placebo (P<.0001)(ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02307513).19

On October 8, 2019, afamelanotide was approved by the FDA to increase pain-free light exposure in adults with erythropoietic protoporphyria, a rare metabolic disorder associated with photosensitivity.20 A melanocortin receptor agonist, afamelanotide is believed to confer photoprotection by increasing the production of eumelanin in the epidermis. The FDA approval was based on 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, both of which found that patients given afamelanotide spent significantly more time in direct sunlight without pain compared to patients in the placebo group (P=.005 and P=.04).21

Recalls of Popular Skin Products

On July 5, 2019, Neutrogena recalled its cult-favorite Light Therapy Acne Mask. The recall was driven by rare reports of transient visual side effects due to insufficient eye protection from the mask’s light-emitting diodes.22,23 Reported in association with 0.02% of masks sold at the time of the recall, these side effects included eye pain, irritation, tearing, blurry vision, seeing spots, and changes in color vision.24 In addition, a risk for potentially irreversible eye injury from the mask was cited in people taking photosensitizing medications, such as doxycycline, and people with certain underlying eye conditions, such as retinitis pigmentosa and ocular albinism.22,24,25

Following decades of asbestos-related controversy, 1 lot of the iconic Johnson’s Baby Powder was recalled for the first time on October 18, 2019, after the FDA found subtrace levels of asbestos in 1 of the lot’s bottles.26 After the recall, Johnson & Johnson reported that 2 third-party laboratories did not ultimately find asbestos when they tested the bottle of interest as well as other bottles from the recalled lot. Three of 5 samples prepared in 1 room by the third-party laboratories initially did test positive for asbestos, but this result was attributed to the room’s air conditioner, which was found to be contaminated with asbestos. When the same samples were prepared in another room, no asbestos was detected.27 The FDA maintained there was “no indication of cross-contamination” when they originally tested the implicated bottle.28

From chemical sunscreen to the measles outbreak and drug approvals to product recalls, dermatology experienced its share of firsts and controversies in 2019.

Chemical Sunscreen Controversies

Controversial concerns about the effects of chemical sunscreen on coral reefs took an unprecedented turn in the United States this last year. On February 5, 2019, an ordinance was passed in Key West, Florida, prohibiting the sale of sunscreen containing the organic UV filters oxybenzone and/or octinoxate within city limits.1 On June 25, 2019, a similar law that also included octocrylene was passed in the US Virgin Islands.2 In so doing, these areas joined Hawaii, the Republic of Palau, and parts of Mexico in restricting chemical sunscreen sales.1 Although the Key West ordinance is set to take effect in January 2021, opponents, including dermatologists who believe it will discourage sunscreen use, currently are trying to overturn the ban.3 In the US Virgin Islands, part of the ban went into effect in September 2019, with the rest of the ban set to start in March 2020.2 Companies have started to follow suit. On August 1, 2019, CVS Pharmacy announced that, by the end of 2020, it will remove oxybenzone and octinoxate from some of its store-brand chemical sunscreens.4

On February 26, 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed that there are insufficient data to determine if 12 organic UV filters—including the aforementioned oxybenzone, octinoxate, and octocrylene—are generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE).5 Although these ingredients were listed as GRASE by the FDA in 2011, the rise in sunscreen use since then, as well as changes in sunscreen formulations, prompted the FDA to ask manufacturers to perform additional studies on safety parameters such as systemic absorption.5,6 One study conducted by the FDA itself was published in May 2019 and showed that maximal use of 4 sunscreens resulted in systemic absorption of 4 organic UV filters above 0.5 ng/mL, the FDA’s threshold for requiring nonclinical toxicology assessment. The study authors concluded that “further studies [are needed] to determine the clinical significance of these findings. [But] These results do not indicate that individuals should refrain from the use of

End of the New York City Measles Outbreak

On September 3, 2019, New York City’s largest measles outbreak in nearly 30 years was declared over. This announcement reflected the fact that 2 incubation periods for measles—42 days—had passed since the last measles patient was considered contagious. In total, there were 654 cases of measles and 52 associated hospitalizations, including 16 admissions to the intensive care unit. Most patients were younger than 18 years and unvaccinated.8

The outbreak began in October 2018 after Orthodox Jewish children from Brooklyn became infected while visiting Israel and imported the measles virus upon their return home.8,9 All 5 boroughs in New York City were ultimately affected, although 4 zip codes in Williamsburg, a neighborhood in Brooklyn with an undervaccinated Orthodox Jewish community, accounted for 72% of cases.8,10 As part of a $6 million effort to stop the outbreak, an emergency order was placed on these 4 zip codes, posing potential fines on people living or working there if they were unvaccinated.8 In addition, a bill was passed and signed into law in New York State that eliminated religious exemptions for immunizations.11 In collaboration with Jewish leaders, these efforts increased the administration of measles-mumps-rubella vaccines by 41% compared with the year before in Williamsburg and Borough Park, another heavily Orthodox Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn.8

Drug Approvals for Pediatric Dermatology

On March 11, 2019, the IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor dupilumab became the third biologic with a pediatric dermatology indication when the FDA extended its approval to adolescents for the treatment of atopic dermatitis.12 The FDA approval was based on a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 42% (34/82) of adolescents treated with dupilumab monotherapy every other week achieved 75% or more improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at week 16 compared with 8% (7/85) in the placebo group (P<.001).13

In October 2019, trifarotene cream and minocycline foam were approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne in patients 9 years and older.14,15 As such, both became the first acne therapies to include patients as young as 9 years in their studies and indication—a milestone, considering the fact that children have historically been excluded from clinical trials.16 The 2 topical treatments also are noteworthy for being first in class: trifarotene cream is the only topical retinoid to selectively target the retinoic acid receptor γ and to have been studied specifically for both facial and truncal acne,14,17 and minocycline foam is the first topical tetracycline.15

Drug Approvals for Rare Dermatologic Diseases

On July 19, 2019, apremilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, became the first medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of adults with oral ulcers due to Behçet disease, a rare multisystem inflammatory disease.18 The FDA approval was based on a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which 53% (55/104) of patients receiving apremilast monotherapy were ulcer free at week 12 compared to 22% (23/103) receiving placebo (P<.0001)(ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02307513).19

On October 8, 2019, afamelanotide was approved by the FDA to increase pain-free light exposure in adults with erythropoietic protoporphyria, a rare metabolic disorder associated with photosensitivity.20 A melanocortin receptor agonist, afamelanotide is believed to confer photoprotection by increasing the production of eumelanin in the epidermis. The FDA approval was based on 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, both of which found that patients given afamelanotide spent significantly more time in direct sunlight without pain compared to patients in the placebo group (P=.005 and P=.04).21

Recalls of Popular Skin Products

On July 5, 2019, Neutrogena recalled its cult-favorite Light Therapy Acne Mask. The recall was driven by rare reports of transient visual side effects due to insufficient eye protection from the mask’s light-emitting diodes.22,23 Reported in association with 0.02% of masks sold at the time of the recall, these side effects included eye pain, irritation, tearing, blurry vision, seeing spots, and changes in color vision.24 In addition, a risk for potentially irreversible eye injury from the mask was cited in people taking photosensitizing medications, such as doxycycline, and people with certain underlying eye conditions, such as retinitis pigmentosa and ocular albinism.22,24,25

Following decades of asbestos-related controversy, 1 lot of the iconic Johnson’s Baby Powder was recalled for the first time on October 18, 2019, after the FDA found subtrace levels of asbestos in 1 of the lot’s bottles.26 After the recall, Johnson & Johnson reported that 2 third-party laboratories did not ultimately find asbestos when they tested the bottle of interest as well as other bottles from the recalled lot. Three of 5 samples prepared in 1 room by the third-party laboratories initially did test positive for asbestos, but this result was attributed to the room’s air conditioner, which was found to be contaminated with asbestos. When the same samples were prepared in another room, no asbestos was detected.27 The FDA maintained there was “no indication of cross-contamination” when they originally tested the implicated bottle.28

- Zraick K. Key West bans sunscreen containing chemicals believed to harm coral reefs. New York Times. February 7, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/us/sunscreen-coral-reef-key-west.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Gies H. The U.S. Virigin Islands becomes the first American jurisdiction to ban common chemical sunscreens. Pacific Standard. July 18, 2019. https://psmag.com/environment/sunscreen-is-corals-biggest-anemone. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Luscombe R. Republicans seek to overturn Key West ban on coral-damaging sunscreens. The Guardian. November 9, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/09/key-west-sunscreen-coral-reef-backlash-skin-cancer. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Salazar D. CVS to remove 2 chemicals from 60 store-brand sunscreens. Drug Store News. August 2, 2019. https://drugstorenews.com/retail-news/cvs-to-remove-2-chemicals-from-60-store-brand-sunscreens. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2019;84(38):6204-6275. To be codified at 21 CFR §201, 310, 347, and 352.

- DeLeo VA. Sunscreen regulations and advice for your patients. Cutis. 2019;103:251-253.

- Matta MK, Zusterzeel R, Pilli NR, et al. Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2082-2091.

- Mayor de Blasio, health officials declare end of measles outbreak in New York City [news release]. New York, NY: City of New York; September 3, 2019. https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/409-19/mayor-de-blasio-health-officials-declare-end-measles-outbreak-new-york-city. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Health department reports eleven new cases of measles in Brooklyn’s Orthodox Jewish community, urges on time vaccination for all children, especially before traveling to Israel and other countries experiencing measles outbreaks [news release]. New York, NY: City of New York; November 2, 2018. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/about/press/pr2018/pr091-18.page. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles elimination. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/elimination.html. Updated October 4, 2019. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- McKinley J. Measles outbreak: N.Y. eliminates religious exemptions for vaccinations. New York Times. June 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/13/nyregion/measles-vaccinations-new-york.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- FDA approves Dupixent® (dupilumab) for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adolescents [news release]. Cambridge, MA: Sanofi; March 11, 2019. http://www.news.sanofi.us/2019-03-11-FDA-approves-Dupixent-R-dupilumab-for-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-in-adolescents. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial [published online ahead of print November 6, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336.

- Galderma receives FDA approval for AKLIEF® (trifarotene) cream, 0.005%, the first new retinoid molecule for the treatment of acne in over 20 years [news release]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; October 4, 2019. https://www.multivu.com/players/English/8613051-galderma-aklief-retinoid-molecule-acne-treatment/. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Update—Foamix receives FDA approval of AMZEEQ™ topical minocycline treatment for millions of moderate to severe acne sufferers [news release]. Bridgewater, NJ: Foamix Pharmaceuticals Ltd; October 18, 2019. http://www.foamix.com/news-releases/news-release-details/update-foamix-receives-fda-approval-amzeeqtm-topical-minocycline. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Redfearn S. Clinical trial patient inclusion and exclusion criteria need an overhaul, say experts. CenterWatch website. April 23, 2018. https://www.centerwatch.com/cwweekly/2018/04/23/clinical-trial-patient-inclusion-and-exclusion-criteria-need-an-overhaul-say-experts. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Tan J, Thiboutot D, Popp G, et al. Randomized phase 3 evaluation of trifarotene 50 mug/g cream treatment of moderate facial and truncal acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1691-1699.

- FDA approves OTEZLA® (apremilast) for the treatment of oral ulcers associated with Behçet’s disease [news release]. Summit, NJ: Celgene; July 19, 2019. https://ir.celgene.com/press-releases/press-release-details/2019/FDA-Approves-OTEZLA-apremilast-for-the-Treatment-of-Oral-Ulcers-Associated-with-Behets-Disease/default.aspx. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Apremilast [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2019.

- FDA approves first treatment to increase pain-free light exposure in patients with a rare disorder [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; October 8, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-increase-pain-free-light-exposure-patients-rare-disorder. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Langendonk JG, Balwani M, Anderson KE, et al. Afamelanotide for erythropoietic protoporphyria. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:48-59.

- Light Therapy Mask recall statement. Neutrogena website. https://www.neutrogena.com/light-therapy-statement.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Bromwich JE. Neutrogena recalls Light Therapy Masks, citing risk of eye injury. New York Times. July 18, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/style/neutrogena-light-therapy-mask-recall.html. Accessed December 23, 2019, 2019.

- Nguyen T. Neutrogena recalls acne mask over concerns about blue light. Chemical & Engineering News. August 6, 2019. https://cen.acs.org/safety/lab-safety/Neutrogena-recalls-acne-mask-over-concerns-about-blue-light/97/web/2019/08. Accessed November 16, 2019.

- Australian Government Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Neutrogena Visibly Clear Light Therapy Acne Mask and Activator: Recall - potential for eye damage. https://www.tga.gov.au/alert/neutrogena-visibly-clear-light-therapy-acne-mask-and-activator. Published July 17, 2019. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc. to voluntarily recall a single lot of Johnson’s Baby Powder in the United States [press release]. New Brunswick, NJ: Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc; October 18, 2019. https://www.factsabouttalc.com/_document/15-new-tests-from-the-same-bottle-of-johnsons-baby-powder-previously-tested-by-fda-find-no-asbestos?id=0000016e-1915-dc68-af7e-df3f147c0000. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- 15 new tests from the same bottle of Johnson’s Baby Powder previously tested by FDA find no asbestos [press release]. New Brunswick, NJ: Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc; October 29, 2019. https://www.factsabouttalc.com/_document/johnson-johnson-consumer-inc-to-voluntarily-recall-a-single-lot-of-johnsons-baby-powder-in-the-united-states?id=0000016d-debf-d71d-a77d-dfbfebeb0000. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Hsu T. Johnson & Johnson says recalled baby powder doesn’t have asbestos. New York Times. October 29, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/29/business/johnson-baby-powder-asbestos.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Zraick K. Key West bans sunscreen containing chemicals believed to harm coral reefs. New York Times. February 7, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/us/sunscreen-coral-reef-key-west.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Gies H. The U.S. Virigin Islands becomes the first American jurisdiction to ban common chemical sunscreens. Pacific Standard. July 18, 2019. https://psmag.com/environment/sunscreen-is-corals-biggest-anemone. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Luscombe R. Republicans seek to overturn Key West ban on coral-damaging sunscreens. The Guardian. November 9, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/09/key-west-sunscreen-coral-reef-backlash-skin-cancer. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Salazar D. CVS to remove 2 chemicals from 60 store-brand sunscreens. Drug Store News. August 2, 2019. https://drugstorenews.com/retail-news/cvs-to-remove-2-chemicals-from-60-store-brand-sunscreens. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Registr. 2019;84(38):6204-6275. To be codified at 21 CFR §201, 310, 347, and 352.

- DeLeo VA. Sunscreen regulations and advice for your patients. Cutis. 2019;103:251-253.

- Matta MK, Zusterzeel R, Pilli NR, et al. Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2082-2091.

- Mayor de Blasio, health officials declare end of measles outbreak in New York City [news release]. New York, NY: City of New York; September 3, 2019. https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/409-19/mayor-de-blasio-health-officials-declare-end-measles-outbreak-new-york-city. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Health department reports eleven new cases of measles in Brooklyn’s Orthodox Jewish community, urges on time vaccination for all children, especially before traveling to Israel and other countries experiencing measles outbreaks [news release]. New York, NY: City of New York; November 2, 2018. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/about/press/pr2018/pr091-18.page. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles elimination. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/elimination.html. Updated October 4, 2019. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- McKinley J. Measles outbreak: N.Y. eliminates religious exemptions for vaccinations. New York Times. June 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/13/nyregion/measles-vaccinations-new-york.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- FDA approves Dupixent® (dupilumab) for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adolescents [news release]. Cambridge, MA: Sanofi; March 11, 2019. http://www.news.sanofi.us/2019-03-11-FDA-approves-Dupixent-R-dupilumab-for-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-in-adolescents. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial [published online ahead of print November 6, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336.

- Galderma receives FDA approval for AKLIEF® (trifarotene) cream, 0.005%, the first new retinoid molecule for the treatment of acne in over 20 years [news release]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; October 4, 2019. https://www.multivu.com/players/English/8613051-galderma-aklief-retinoid-molecule-acne-treatment/. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Update—Foamix receives FDA approval of AMZEEQ™ topical minocycline treatment for millions of moderate to severe acne sufferers [news release]. Bridgewater, NJ: Foamix Pharmaceuticals Ltd; October 18, 2019. http://www.foamix.com/news-releases/news-release-details/update-foamix-receives-fda-approval-amzeeqtm-topical-minocycline. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Redfearn S. Clinical trial patient inclusion and exclusion criteria need an overhaul, say experts. CenterWatch website. April 23, 2018. https://www.centerwatch.com/cwweekly/2018/04/23/clinical-trial-patient-inclusion-and-exclusion-criteria-need-an-overhaul-say-experts. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Tan J, Thiboutot D, Popp G, et al. Randomized phase 3 evaluation of trifarotene 50 mug/g cream treatment of moderate facial and truncal acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1691-1699.

- FDA approves OTEZLA® (apremilast) for the treatment of oral ulcers associated with Behçet’s disease [news release]. Summit, NJ: Celgene; July 19, 2019. https://ir.celgene.com/press-releases/press-release-details/2019/FDA-Approves-OTEZLA-apremilast-for-the-Treatment-of-Oral-Ulcers-Associated-with-Behets-Disease/default.aspx. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Apremilast [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2019.

- FDA approves first treatment to increase pain-free light exposure in patients with a rare disorder [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; October 8, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-increase-pain-free-light-exposure-patients-rare-disorder. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Langendonk JG, Balwani M, Anderson KE, et al. Afamelanotide for erythropoietic protoporphyria. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:48-59.

- Light Therapy Mask recall statement. Neutrogena website. https://www.neutrogena.com/light-therapy-statement.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Bromwich JE. Neutrogena recalls Light Therapy Masks, citing risk of eye injury. New York Times. July 18, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/style/neutrogena-light-therapy-mask-recall.html. Accessed December 23, 2019, 2019.

- Nguyen T. Neutrogena recalls acne mask over concerns about blue light. Chemical & Engineering News. August 6, 2019. https://cen.acs.org/safety/lab-safety/Neutrogena-recalls-acne-mask-over-concerns-about-blue-light/97/web/2019/08. Accessed November 16, 2019.

- Australian Government Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Neutrogena Visibly Clear Light Therapy Acne Mask and Activator: Recall - potential for eye damage. https://www.tga.gov.au/alert/neutrogena-visibly-clear-light-therapy-acne-mask-and-activator. Published July 17, 2019. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc. to voluntarily recall a single lot of Johnson’s Baby Powder in the United States [press release]. New Brunswick, NJ: Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc; October 18, 2019. https://www.factsabouttalc.com/_document/15-new-tests-from-the-same-bottle-of-johnsons-baby-powder-previously-tested-by-fda-find-no-asbestos?id=0000016e-1915-dc68-af7e-df3f147c0000. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- 15 new tests from the same bottle of Johnson’s Baby Powder previously tested by FDA find no asbestos [press release]. New Brunswick, NJ: Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc; October 29, 2019. https://www.factsabouttalc.com/_document/johnson-johnson-consumer-inc-to-voluntarily-recall-a-single-lot-of-johnsons-baby-powder-in-the-united-states?id=0000016d-debf-d71d-a77d-dfbfebeb0000. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Hsu T. Johnson & Johnson says recalled baby powder doesn’t have asbestos. New York Times. October 29, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/29/business/johnson-baby-powder-asbestos.html. Accessed December 23, 2019.

Resident Pearls

- Chemical sunscreen made headlines in 2019 due to concerns over coral reef toxicity and systemic absorption in humans.

- With a total of 654 cases, New York City’s largest measles outbreak in nearly 30 years ended in September 2019.

- From dupilumab for adolescent atopic dermatitis to apremilast for Behçet disease, the US Food and Drug Administration approved several therapies for pediatric dermatology and rare dermatologic conditions in 2019.

- Two popular skin care products—the Neutrogena Light Therapy Acne Mask and Johnson’s Baby Powder—were involved in recalls in 2019.

Skin Scores: A Review of Clinical Scoring Systems in Dermatology

The practice of dermatology is rife with bedside tools: swabs, smears, and scoring systems. First popularized in specialties such as emergency medicine and internal medicine, clinical scoring systems are now emerging in dermatology. These evidence-based scores can be calculated quickly at the bedside—often through a free smartphone app—to help guide clinical decision-making regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and management. As with any medical tool, scoring systems have limitations and should be used as a supplement, not substitute, for one’s clinical judgement. This article reviews 4 clinical scoring systems practical for dermatology residents.

SCORTEN Prognosticates Cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Perhaps the best-known scoring system in dermatology, the SCORTEN is widely used to predict hospital mortality from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. The SCORTEN includes 7 variables of equal weight—age of 40 years or older, heart rate of 120 beats per minute or more, cancer/hematologic malignancy, involved body surface area (BSA) greater than 10%, serum urea greater than 10 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/L, and serum glucose greater than 14 mmol/L—each contributing 1 point to the overall score if present.1 The involved BSA is defined as the sum of detached and detachable epidermis.1

The SCORTEN was developed and prospectively validated to be calculated at the end of the first 24 hours of admission; for this calculation, use the BSA affected at that time, and use the most abnormal values during the first 24 hours of admission for the other variables.1 In addition, a follow-up study including some of the original coauthors recommends recalculating the SCORTEN at the end of hospital day 3, having found that the score’s predictive value was better on this day than hospital days 1, 2, 4, or 5.2 Based on the original study, a SCORTEN of 0 to 1 corresponds to a mortality rate of 3.2%, 2 to 12.1%, 3 to 35.3%, 4 to 58.3%, and 5 or greater to 90.0%.1

Limitations of the SCORTEN include its ability to overestimate or underestimate mortality as demonstrated by 2 multi-institutional cohorts.3,4 Recently, the ABCD-10 score was developed as an alternative to the SCORTEN and was found to predict mortality similarly when validated in an internal cohort.5

PEST Screens for Psoriatic Arthritis

Dermatologists play an important role in screening for psoriatic arthritis, as an estimated 1 in 5 patients with psoriasis have psoriatic arthritis.6 To this end, several screening tools have been developed to help differentiate psoriatic arthritis from other arthritides. Joint guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation acknowledge that “. . . these screening tools have tended to perform less well when tested in groups of people other than those for which they were originally developed. As such, their usefulness in routine clinical practice remains controversial.”7 Nevertheless, the guidelines state, “[b]ecause screening and early detection of inflammatory arthritis are essential to optimize patient [quality of life] and reduce morbidity, providers may consider using a formal screening tool of their choice.”7

With these limitations in mind, I have found the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) to be the most useful psoriatic arthritis screening tool. One study determined that the PEST has the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity compared to 2 other psoriatic arthritis screening tools, the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) and the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP).8

The PEST is comprised of 5 questions: (1) Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)? (2) Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis? (3) Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits? (4) Have you had pain in your heel? (5) Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason? According to the PEST, a referral to a rheumatologist should be considered for patients answering yes to 3 or more questions, which is 97% sensitive and 79% specific for psoriatic arthritis.9 Patients who answer yes to fewer than 3 questions should still be referred to a rheumatologist if there is a strong clinical suspicion of psoriatic arthritis.10

The PEST can be accessed for free in 13 languages via the GRAPPA (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) app as well as downloaded for free from the National Psoriasis Foundation’s website (https://www.psoriasis.org/psa-screening/providers).

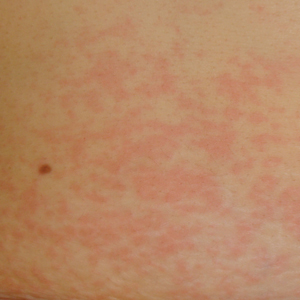

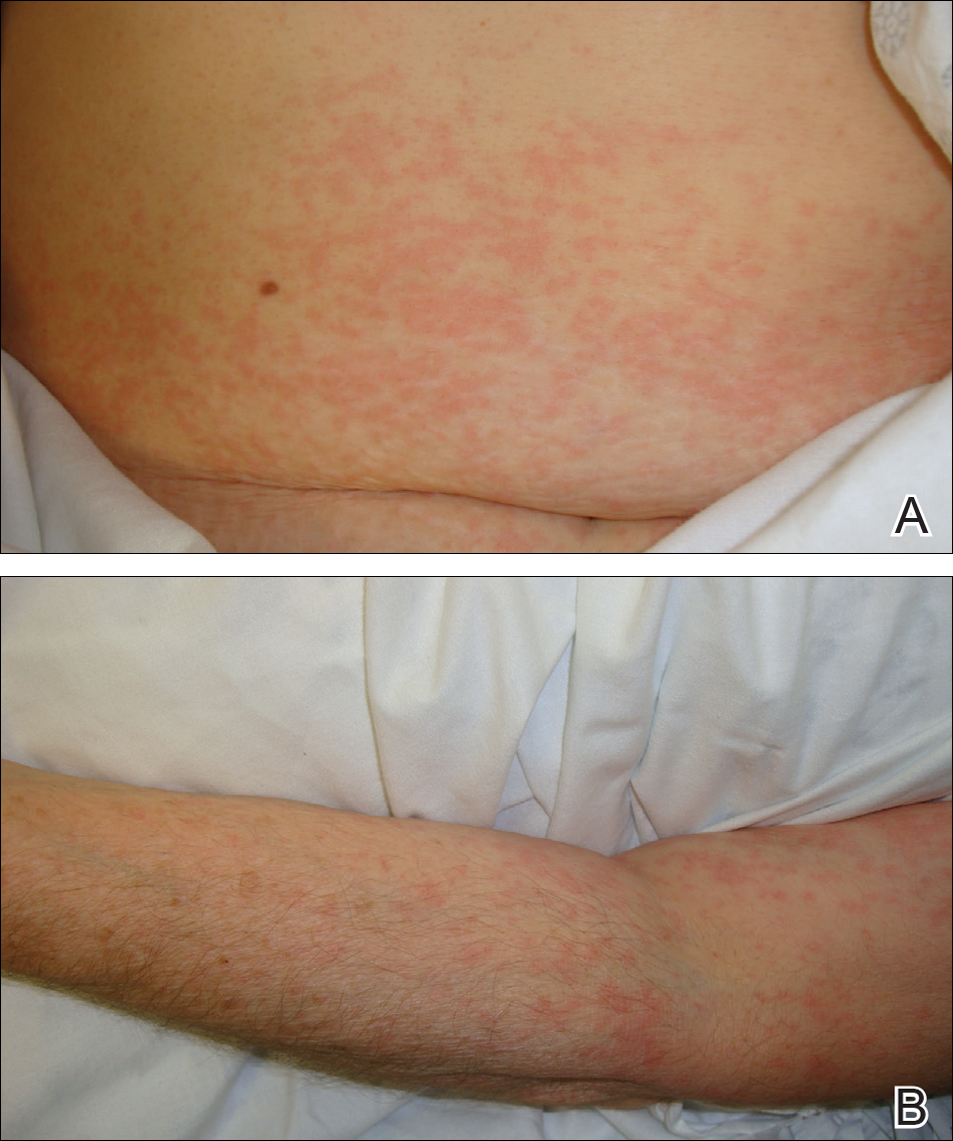

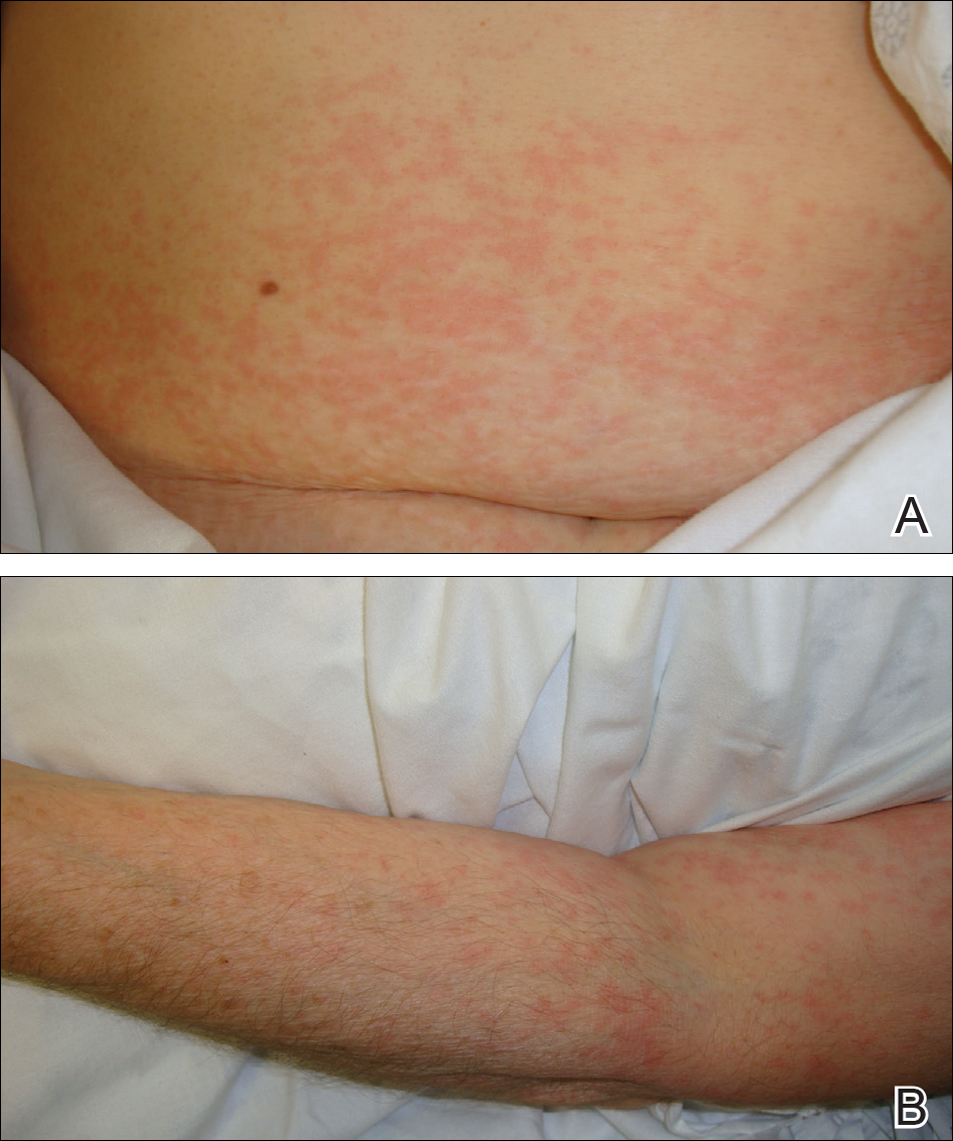

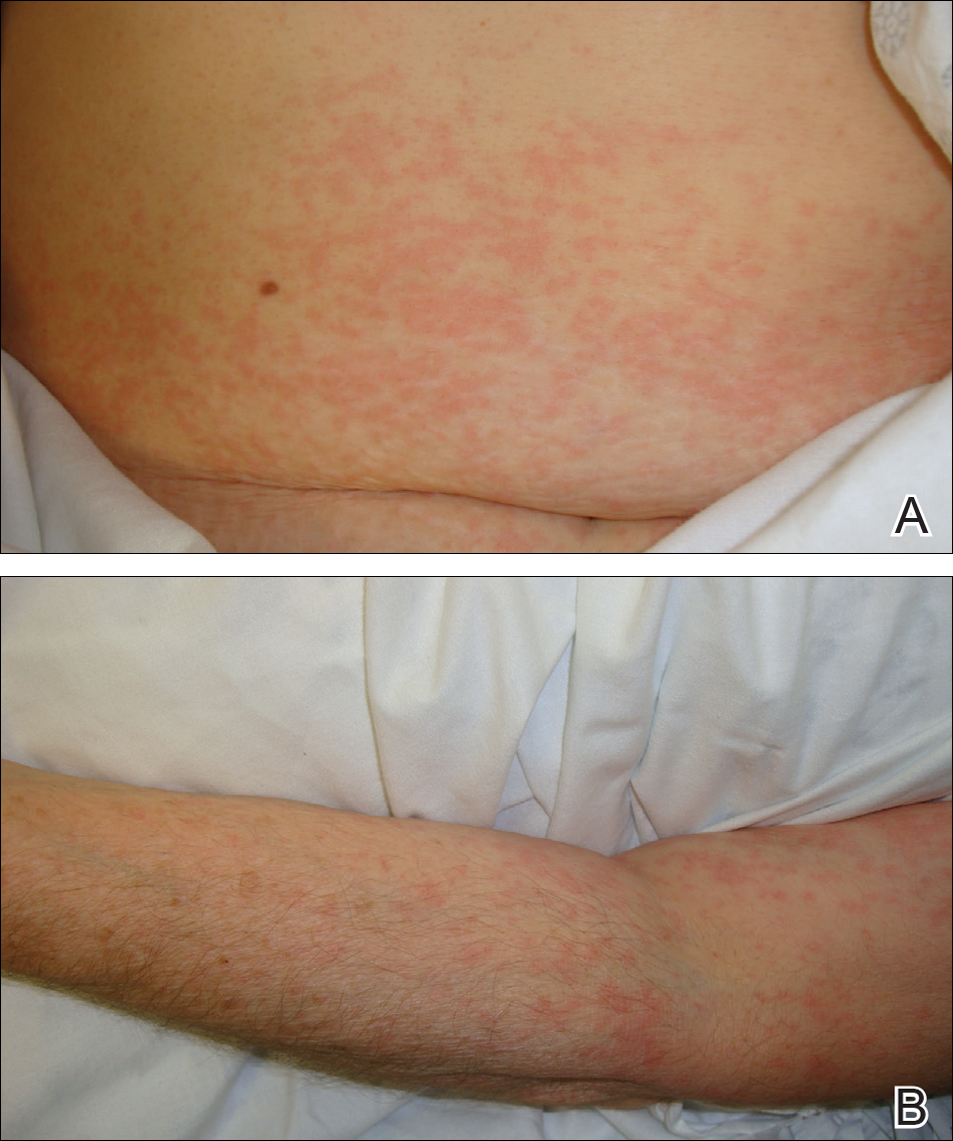

ALT-70 Differentiates Cellulitis From Pseudocellulitis

Overdiagnosing cellulitis in the United States has been estimated to result in up to 130,000 unnecessary hospitalizations and up to $515 million in avoidable health care spending.11 Dermatologists are in a unique position to help fix this issue. In one retrospective study of 1430 inpatient dermatology consultations, 74.32% of inpatients evaluated for presumed cellulitis by a dermatologist were instead diagnosed with a cellulitis mimicker (ie, pseudocellulitis), such as stasis dermatitis or contact dermatitis.12

The ALT-70 score was developed and prospectively validated to help differentiate lower extremity cellulitis from pseudocellulitis in adult patients in the emergency department (ED).13 In addition, the score has retrospectively been shown to function similarly in the inpatient setting when calculated at 24 and 48 hours after ED presentation.14 Although the ALT-70 score was designed for use by frontline clinicians prior to dermatology consultation, I also have found it helpful to calculate as a consultant, as it provides an objective measure of risk to communicate to the primary team in support of one diagnosis or another.

ALT-70 is an acronym for the score’s 4 variables: asymmetry, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and age of 70 years or older.15 If present, each variable confers a certain number of points to the final score: 3 points for asymmetry (defined as unilateral leg involvement), 1 point for leukocytosis (white blood cell count ≥10,000/μL), 1 point for tachycardia (≥90 beats per minute), and 2 points for age of 70 years or older. An ALT-70 score of 0 to 2 corresponds to an 83.3% or greater chance of pseudocellulitis, suggesting that the diagnosis of cellulitis be reconsidered. A score of 3 to 4 is indeterminate, and additional information such as a dermatology consultation should be pursued. A score of 5 to 7 corresponds to an 82.2% or greater chance of cellulitis, signifying that empiric treatment with antibiotics be considered.15

The ALT-70 score does not apply to cases involving areas other than the lower extremities; intravenous antibiotic use within 48 hours before ED presentation; surgery within the last 30 days; abscess; penetrating trauma; burn; or known history of osteomyelitis, diabetic ulcer, or indwelling hardware at the site of infection.15 The ALT-70 score is available for free via the MDCalc app and website (https://www.mdcalc.com/alt-70-score-cellulitis).

Mohs AUC Determines the Appropriateness of Mohs Micrographic Surgery

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery published appropriate use criteria (AUC) to guide the decision to pursue Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) in the United States.16 Based on various tumor and patient characteristics, the Mohs AUC assign scores to 270 different clinical scenarios. A score of 1 to 3 signifies that MMS is inappropriate and generally not considered acceptable. A score 4 to 6 indicates that the appropriateness of MMS is uncertain. A score 7 to 9 means that MMS is appropriate and generally considered acceptable.16

Since publication, the Mohs AUC have been criticized for classifying most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for MMS17 (which an AUC coauthor18 and others19,20 have defended), excluding certain reasons for performing MMS (such as operating on multiple tumors on the same day),21 including counterintuitive scores,22 and omitting trials from Europe23 (which AUC coauthors also have defended24).

Final Thoughts

Scoring systems are emerging in dermatology as evidence-based bedside tools to help guide clinical decision-making. Despite their limitations, these scores have the potential to make a meaningful impact in dermatology as they have in other specialties.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153.

- Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:272-276.

- Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multicenter retrospective study of 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:2315-2321.

- Sekula P, Liss Y, Davidovici B, et al. Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis included in the RegiSCAR study. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:237-245.

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality among patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-ABCD-10. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:448-454.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.e219.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Karreman MC, Weel A, van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:597-602.

- Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:469-474.

- Zhang A, Kurtzman DJB, Perez-Chada LM, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and the dermatologist: an approach to screening and clinical evaluation. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:551-560.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:141-146.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Li DG, Dewan AK, Xia FD, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model outperforms thermal imaging for the diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a prospective evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1076-1080.e1071.

- Singer S, Li DG, Gunasekera N, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model maintains predictive value at 24 and 48 hours after presentation [published online March 23, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.050.

- Raff AB, Weng QY, Cohen JM, et al. A predictive model for diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:618-625.e2.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs surgery appropriate use criteria for primary superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:755-756.

- Montuno MA, Coldiron BM. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:394-395.

- MacFarlane DF, Perlis C. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395-396.

- Kantor J. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria [published online December 23, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064.

- Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:317-318.

- Connolly S, Baker D, Coldiron B, et al. Reply to “comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:318.

The practice of dermatology is rife with bedside tools: swabs, smears, and scoring systems. First popularized in specialties such as emergency medicine and internal medicine, clinical scoring systems are now emerging in dermatology. These evidence-based scores can be calculated quickly at the bedside—often through a free smartphone app—to help guide clinical decision-making regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and management. As with any medical tool, scoring systems have limitations and should be used as a supplement, not substitute, for one’s clinical judgement. This article reviews 4 clinical scoring systems practical for dermatology residents.

SCORTEN Prognosticates Cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Perhaps the best-known scoring system in dermatology, the SCORTEN is widely used to predict hospital mortality from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. The SCORTEN includes 7 variables of equal weight—age of 40 years or older, heart rate of 120 beats per minute or more, cancer/hematologic malignancy, involved body surface area (BSA) greater than 10%, serum urea greater than 10 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/L, and serum glucose greater than 14 mmol/L—each contributing 1 point to the overall score if present.1 The involved BSA is defined as the sum of detached and detachable epidermis.1

The SCORTEN was developed and prospectively validated to be calculated at the end of the first 24 hours of admission; for this calculation, use the BSA affected at that time, and use the most abnormal values during the first 24 hours of admission for the other variables.1 In addition, a follow-up study including some of the original coauthors recommends recalculating the SCORTEN at the end of hospital day 3, having found that the score’s predictive value was better on this day than hospital days 1, 2, 4, or 5.2 Based on the original study, a SCORTEN of 0 to 1 corresponds to a mortality rate of 3.2%, 2 to 12.1%, 3 to 35.3%, 4 to 58.3%, and 5 or greater to 90.0%.1

Limitations of the SCORTEN include its ability to overestimate or underestimate mortality as demonstrated by 2 multi-institutional cohorts.3,4 Recently, the ABCD-10 score was developed as an alternative to the SCORTEN and was found to predict mortality similarly when validated in an internal cohort.5

PEST Screens for Psoriatic Arthritis

Dermatologists play an important role in screening for psoriatic arthritis, as an estimated 1 in 5 patients with psoriasis have psoriatic arthritis.6 To this end, several screening tools have been developed to help differentiate psoriatic arthritis from other arthritides. Joint guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation acknowledge that “. . . these screening tools have tended to perform less well when tested in groups of people other than those for which they were originally developed. As such, their usefulness in routine clinical practice remains controversial.”7 Nevertheless, the guidelines state, “[b]ecause screening and early detection of inflammatory arthritis are essential to optimize patient [quality of life] and reduce morbidity, providers may consider using a formal screening tool of their choice.”7

With these limitations in mind, I have found the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) to be the most useful psoriatic arthritis screening tool. One study determined that the PEST has the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity compared to 2 other psoriatic arthritis screening tools, the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) and the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP).8

The PEST is comprised of 5 questions: (1) Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)? (2) Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis? (3) Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits? (4) Have you had pain in your heel? (5) Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason? According to the PEST, a referral to a rheumatologist should be considered for patients answering yes to 3 or more questions, which is 97% sensitive and 79% specific for psoriatic arthritis.9 Patients who answer yes to fewer than 3 questions should still be referred to a rheumatologist if there is a strong clinical suspicion of psoriatic arthritis.10

The PEST can be accessed for free in 13 languages via the GRAPPA (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) app as well as downloaded for free from the National Psoriasis Foundation’s website (https://www.psoriasis.org/psa-screening/providers).

ALT-70 Differentiates Cellulitis From Pseudocellulitis

Overdiagnosing cellulitis in the United States has been estimated to result in up to 130,000 unnecessary hospitalizations and up to $515 million in avoidable health care spending.11 Dermatologists are in a unique position to help fix this issue. In one retrospective study of 1430 inpatient dermatology consultations, 74.32% of inpatients evaluated for presumed cellulitis by a dermatologist were instead diagnosed with a cellulitis mimicker (ie, pseudocellulitis), such as stasis dermatitis or contact dermatitis.12

The ALT-70 score was developed and prospectively validated to help differentiate lower extremity cellulitis from pseudocellulitis in adult patients in the emergency department (ED).13 In addition, the score has retrospectively been shown to function similarly in the inpatient setting when calculated at 24 and 48 hours after ED presentation.14 Although the ALT-70 score was designed for use by frontline clinicians prior to dermatology consultation, I also have found it helpful to calculate as a consultant, as it provides an objective measure of risk to communicate to the primary team in support of one diagnosis or another.

ALT-70 is an acronym for the score’s 4 variables: asymmetry, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and age of 70 years or older.15 If present, each variable confers a certain number of points to the final score: 3 points for asymmetry (defined as unilateral leg involvement), 1 point for leukocytosis (white blood cell count ≥10,000/μL), 1 point for tachycardia (≥90 beats per minute), and 2 points for age of 70 years or older. An ALT-70 score of 0 to 2 corresponds to an 83.3% or greater chance of pseudocellulitis, suggesting that the diagnosis of cellulitis be reconsidered. A score of 3 to 4 is indeterminate, and additional information such as a dermatology consultation should be pursued. A score of 5 to 7 corresponds to an 82.2% or greater chance of cellulitis, signifying that empiric treatment with antibiotics be considered.15

The ALT-70 score does not apply to cases involving areas other than the lower extremities; intravenous antibiotic use within 48 hours before ED presentation; surgery within the last 30 days; abscess; penetrating trauma; burn; or known history of osteomyelitis, diabetic ulcer, or indwelling hardware at the site of infection.15 The ALT-70 score is available for free via the MDCalc app and website (https://www.mdcalc.com/alt-70-score-cellulitis).

Mohs AUC Determines the Appropriateness of Mohs Micrographic Surgery

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery published appropriate use criteria (AUC) to guide the decision to pursue Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) in the United States.16 Based on various tumor and patient characteristics, the Mohs AUC assign scores to 270 different clinical scenarios. A score of 1 to 3 signifies that MMS is inappropriate and generally not considered acceptable. A score 4 to 6 indicates that the appropriateness of MMS is uncertain. A score 7 to 9 means that MMS is appropriate and generally considered acceptable.16

Since publication, the Mohs AUC have been criticized for classifying most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for MMS17 (which an AUC coauthor18 and others19,20 have defended), excluding certain reasons for performing MMS (such as operating on multiple tumors on the same day),21 including counterintuitive scores,22 and omitting trials from Europe23 (which AUC coauthors also have defended24).

Final Thoughts

Scoring systems are emerging in dermatology as evidence-based bedside tools to help guide clinical decision-making. Despite their limitations, these scores have the potential to make a meaningful impact in dermatology as they have in other specialties.

The practice of dermatology is rife with bedside tools: swabs, smears, and scoring systems. First popularized in specialties such as emergency medicine and internal medicine, clinical scoring systems are now emerging in dermatology. These evidence-based scores can be calculated quickly at the bedside—often through a free smartphone app—to help guide clinical decision-making regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and management. As with any medical tool, scoring systems have limitations and should be used as a supplement, not substitute, for one’s clinical judgement. This article reviews 4 clinical scoring systems practical for dermatology residents.

SCORTEN Prognosticates Cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Perhaps the best-known scoring system in dermatology, the SCORTEN is widely used to predict hospital mortality from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. The SCORTEN includes 7 variables of equal weight—age of 40 years or older, heart rate of 120 beats per minute or more, cancer/hematologic malignancy, involved body surface area (BSA) greater than 10%, serum urea greater than 10 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/L, and serum glucose greater than 14 mmol/L—each contributing 1 point to the overall score if present.1 The involved BSA is defined as the sum of detached and detachable epidermis.1

The SCORTEN was developed and prospectively validated to be calculated at the end of the first 24 hours of admission; for this calculation, use the BSA affected at that time, and use the most abnormal values during the first 24 hours of admission for the other variables.1 In addition, a follow-up study including some of the original coauthors recommends recalculating the SCORTEN at the end of hospital day 3, having found that the score’s predictive value was better on this day than hospital days 1, 2, 4, or 5.2 Based on the original study, a SCORTEN of 0 to 1 corresponds to a mortality rate of 3.2%, 2 to 12.1%, 3 to 35.3%, 4 to 58.3%, and 5 or greater to 90.0%.1

Limitations of the SCORTEN include its ability to overestimate or underestimate mortality as demonstrated by 2 multi-institutional cohorts.3,4 Recently, the ABCD-10 score was developed as an alternative to the SCORTEN and was found to predict mortality similarly when validated in an internal cohort.5

PEST Screens for Psoriatic Arthritis

Dermatologists play an important role in screening for psoriatic arthritis, as an estimated 1 in 5 patients with psoriasis have psoriatic arthritis.6 To this end, several screening tools have been developed to help differentiate psoriatic arthritis from other arthritides. Joint guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation acknowledge that “. . . these screening tools have tended to perform less well when tested in groups of people other than those for which they were originally developed. As such, their usefulness in routine clinical practice remains controversial.”7 Nevertheless, the guidelines state, “[b]ecause screening and early detection of inflammatory arthritis are essential to optimize patient [quality of life] and reduce morbidity, providers may consider using a formal screening tool of their choice.”7

With these limitations in mind, I have found the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) to be the most useful psoriatic arthritis screening tool. One study determined that the PEST has the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity compared to 2 other psoriatic arthritis screening tools, the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) and the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP).8

The PEST is comprised of 5 questions: (1) Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)? (2) Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis? (3) Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits? (4) Have you had pain in your heel? (5) Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason? According to the PEST, a referral to a rheumatologist should be considered for patients answering yes to 3 or more questions, which is 97% sensitive and 79% specific for psoriatic arthritis.9 Patients who answer yes to fewer than 3 questions should still be referred to a rheumatologist if there is a strong clinical suspicion of psoriatic arthritis.10

The PEST can be accessed for free in 13 languages via the GRAPPA (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) app as well as downloaded for free from the National Psoriasis Foundation’s website (https://www.psoriasis.org/psa-screening/providers).

ALT-70 Differentiates Cellulitis From Pseudocellulitis

Overdiagnosing cellulitis in the United States has been estimated to result in up to 130,000 unnecessary hospitalizations and up to $515 million in avoidable health care spending.11 Dermatologists are in a unique position to help fix this issue. In one retrospective study of 1430 inpatient dermatology consultations, 74.32% of inpatients evaluated for presumed cellulitis by a dermatologist were instead diagnosed with a cellulitis mimicker (ie, pseudocellulitis), such as stasis dermatitis or contact dermatitis.12

The ALT-70 score was developed and prospectively validated to help differentiate lower extremity cellulitis from pseudocellulitis in adult patients in the emergency department (ED).13 In addition, the score has retrospectively been shown to function similarly in the inpatient setting when calculated at 24 and 48 hours after ED presentation.14 Although the ALT-70 score was designed for use by frontline clinicians prior to dermatology consultation, I also have found it helpful to calculate as a consultant, as it provides an objective measure of risk to communicate to the primary team in support of one diagnosis or another.

ALT-70 is an acronym for the score’s 4 variables: asymmetry, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and age of 70 years or older.15 If present, each variable confers a certain number of points to the final score: 3 points for asymmetry (defined as unilateral leg involvement), 1 point for leukocytosis (white blood cell count ≥10,000/μL), 1 point for tachycardia (≥90 beats per minute), and 2 points for age of 70 years or older. An ALT-70 score of 0 to 2 corresponds to an 83.3% or greater chance of pseudocellulitis, suggesting that the diagnosis of cellulitis be reconsidered. A score of 3 to 4 is indeterminate, and additional information such as a dermatology consultation should be pursued. A score of 5 to 7 corresponds to an 82.2% or greater chance of cellulitis, signifying that empiric treatment with antibiotics be considered.15

The ALT-70 score does not apply to cases involving areas other than the lower extremities; intravenous antibiotic use within 48 hours before ED presentation; surgery within the last 30 days; abscess; penetrating trauma; burn; or known history of osteomyelitis, diabetic ulcer, or indwelling hardware at the site of infection.15 The ALT-70 score is available for free via the MDCalc app and website (https://www.mdcalc.com/alt-70-score-cellulitis).

Mohs AUC Determines the Appropriateness of Mohs Micrographic Surgery

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery published appropriate use criteria (AUC) to guide the decision to pursue Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) in the United States.16 Based on various tumor and patient characteristics, the Mohs AUC assign scores to 270 different clinical scenarios. A score of 1 to 3 signifies that MMS is inappropriate and generally not considered acceptable. A score 4 to 6 indicates that the appropriateness of MMS is uncertain. A score 7 to 9 means that MMS is appropriate and generally considered acceptable.16

Since publication, the Mohs AUC have been criticized for classifying most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for MMS17 (which an AUC coauthor18 and others19,20 have defended), excluding certain reasons for performing MMS (such as operating on multiple tumors on the same day),21 including counterintuitive scores,22 and omitting trials from Europe23 (which AUC coauthors also have defended24).

Final Thoughts

Scoring systems are emerging in dermatology as evidence-based bedside tools to help guide clinical decision-making. Despite their limitations, these scores have the potential to make a meaningful impact in dermatology as they have in other specialties.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153.

- Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:272-276.

- Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multicenter retrospective study of 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:2315-2321.

- Sekula P, Liss Y, Davidovici B, et al. Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis included in the RegiSCAR study. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:237-245.

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality among patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-ABCD-10. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:448-454.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.e219.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Karreman MC, Weel A, van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:597-602.

- Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:469-474.

- Zhang A, Kurtzman DJB, Perez-Chada LM, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and the dermatologist: an approach to screening and clinical evaluation. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:551-560.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:141-146.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Li DG, Dewan AK, Xia FD, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model outperforms thermal imaging for the diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a prospective evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1076-1080.e1071.

- Singer S, Li DG, Gunasekera N, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model maintains predictive value at 24 and 48 hours after presentation [published online March 23, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.050.

- Raff AB, Weng QY, Cohen JM, et al. A predictive model for diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:618-625.e2.