User login

Tissue Isn’t the Issue

A 43-year-old man with a history of asplenia, hepatitis C, and nephrolithiasis reported right-flank pain. He described severe, sharp pain that came in waves and radiated to the right groin, associated with nausea and nonbloody emesis. He noted “pink urine” but no dysuria. He had 4prior similar episodes during which he had passed kidney stones, although stone analysis had never been performed. He denied having fevers or chills.

The patient had been involved in a remote motor vehicle accident complicated by splenic laceration, for which he underwent splenectomy. He was appropriately immunized. The patient also suffered from bipolar affective disorder and untreated chronic hepatitis C infection with no evidence of cirrhosis. He smoked one pack of tobacco per day for the last 10 years and reported distant alcohol and methamphetamine use.

Right-flank pain can arise from conditions affecting the lower thorax (effusion, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism), abdomen (hepatobiliary or intestinal disease), retroperitoneum (hemorrhage or infection), musculoskeletal system, peripheral nerves (herpes zoster), or the genitourinary system (pyelonephritis). Pain radiating to the groin, discolored urine (suggesting hematuria), and history of kidney stones increase the likelihood of renal colic from nephrolithiasis.

Less commonly, flank pain and hematuria may present as initial symptoms of renal cell carcinoma, renal infarction, or aortic dissection. The patient’s immunosuppression from asplenia and active injection drug use could predispose him to septic emboli to his kidneys. Prior trauma causing aortic injury could predispose himto subsequent dissection.

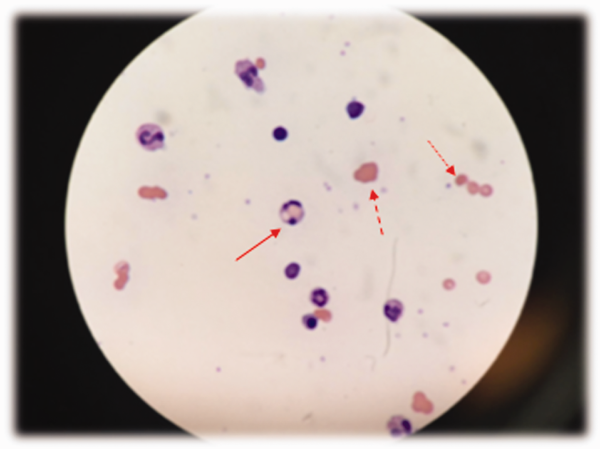

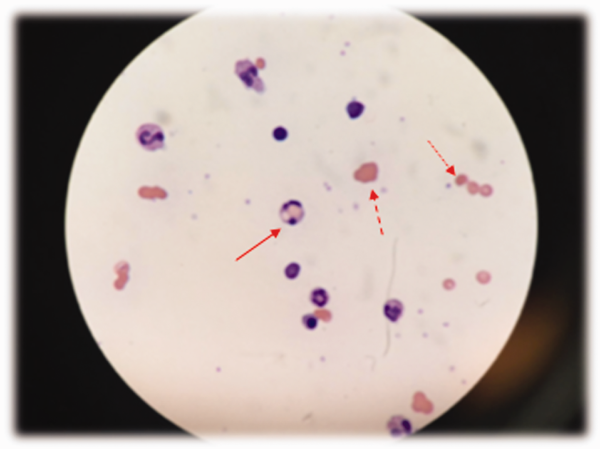

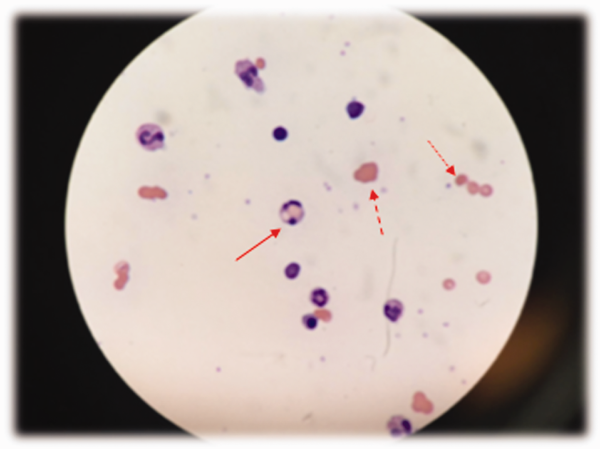

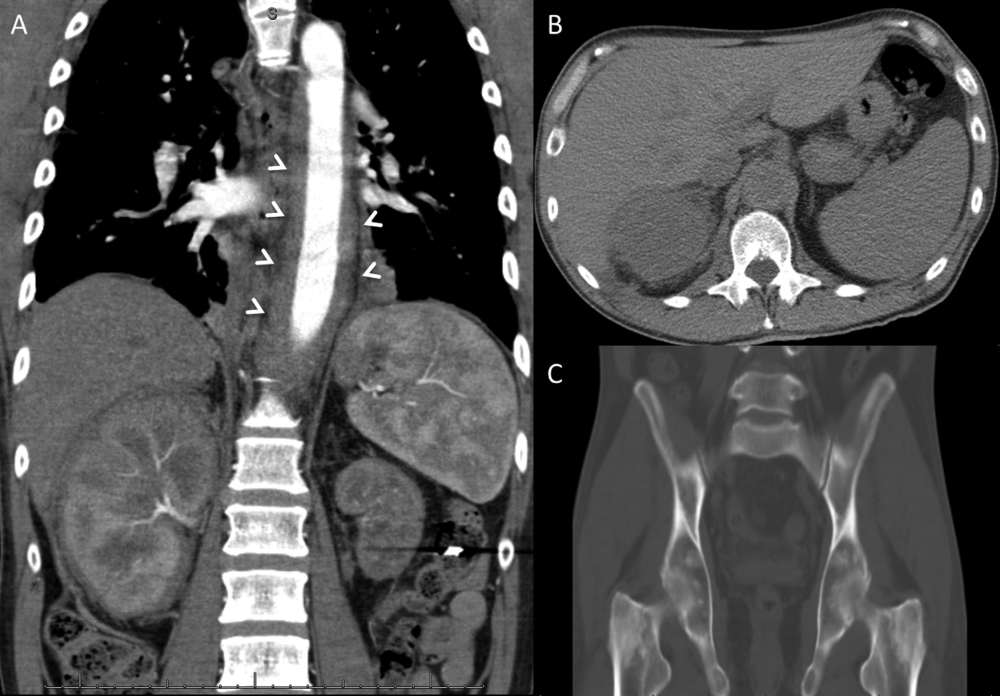

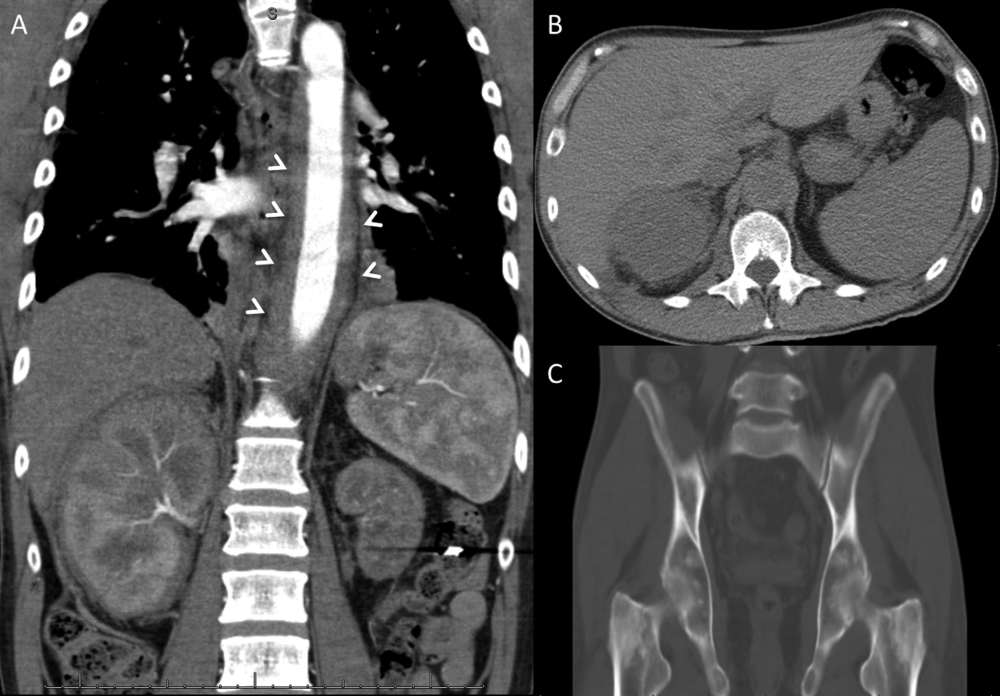

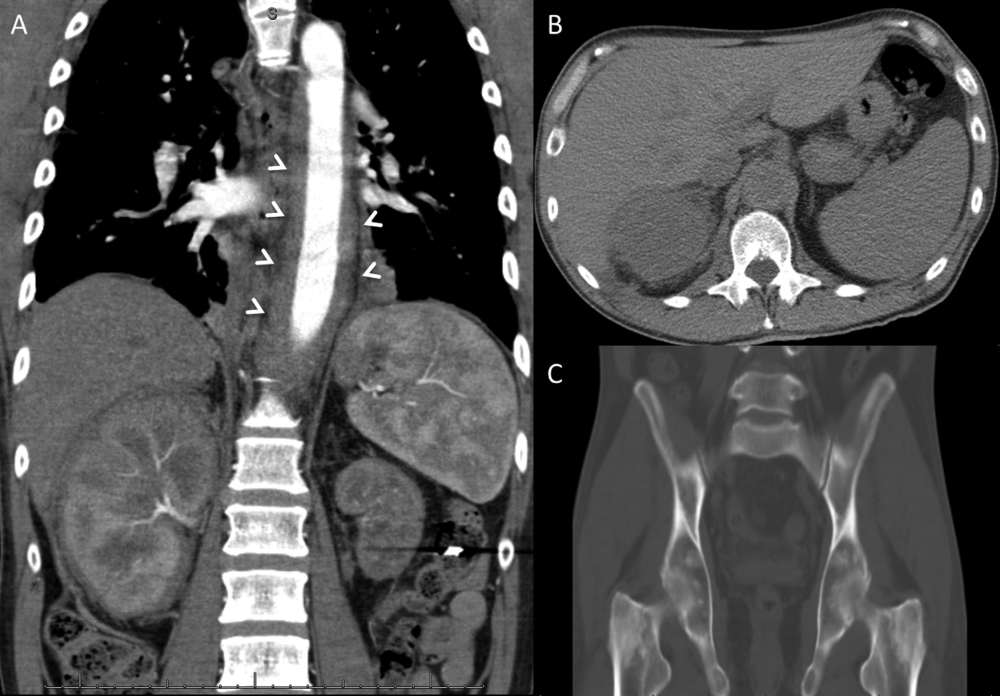

The patient appeared well with a heart rate of 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 122/76 mmHg, temperature 36.8°C, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. His cardiopulmonary and abdominal examinations were normal, and he had no costovertebral angle tenderness. His skin was warm and dry without rashes. His white blood cell (WBC) count was 26,000/μL; absolute neutrophil count was 22,000/μL. Serum chemistries were normal, including creatinine 0.63 mg/dL, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, and phosphorus 3.1 mg/dL. Lactate was 0.8 mmol/L (reference range: 0-2.0 mmol/L). Urinalysis revealed large ketones, >50 red blood cells (RBC) per high power field (HPF), <5 WBC per HPF, 1+ calcium oxalate crystals and pH 6.0. A bedside ultrasound showed mild right hydronephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated diffuse, mildly prominent subcentimeter mesenteric lymphadenopathy and no kidney stones. He was treated with intravenous fluids and pain control, and was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of a passed kidney stone.

A passed stone would not explain this degree of leukocytosis. The CT results reduce the likelihood of a renal neoplasm, renal infarction, or pyelonephritis. Mesenteric lymphadenopathy is nonspecific, but it may signal underlying infection or malignancy with spread to lymph nodes, or it may be part of a systemic disorder causing generalized lymphadenopathy. Malignant causes of mesenteric lymphadenopathy (with no apparent primary tumor) include testicular cancer, lymphoma, and primary urogenital neoplasms.

The lower extremity nodules are consistent with erythema nodosum, which may be observed in numerous infectious and noninfectious illnesses. The rapid tempo of this febrile illness mandates early consideration of infection. Splenectomized patients are at risk for overwhelming post-splenectomy infection from encapsulated organisms, although this risk is significantly mitigated with appropriate immunization. The patient is at risk of bacterial endocarditis, which could explain his fevers and polyarthritis, although plaques, pustules, and oral ulcers would be unusual. Disseminated gonococcal infection causes fevers, oral lesions, polyarthritis and pustular skin lesions, but plaques are uncommon. Disseminated mycobacterial and fungal infections may cause oral ulcers, but affected patients tend to be severely ill and have profound immunosuppression. Secondary syphilis may account for many of the findings; however, oral ulcers would be unusual, and the rash tends to be more widespread, with a predilection for the palms and soles. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can cause oral ulcers and is the chief viral etiology to consider.

Noninfectious illnesses to consider include neoplasms and connective tissue diseases. Malignancy would be unlikely to manifest this abruptly or produce a paraneoplastic disorder with these features.

The patient described severe fatigue and drenching night sweats for two months prior to admission. He denied dyspnea or cough. He was born in the southwestern United States and had lived in California for almost a decade. He had been incarcerated for a few years and released three years prior. He had intermittently lived in homeless shelters, but currently lived alone in downtown San Francisco. He had traveled remotely to the Caribbean, and more recently traveled frequently to the Central Valley in California. The patient formerly worked as a pipe-fitter and welder. He denied animal exposure or recent sick contacts. He was sexually active with women, and intermittently used barrier protection.

His years in the southwestern United States may have exposed the patient to blastomycosis or histoplasmosis; both can mimic mycobacterial disease. Blastomycosis demonstrates a slightly stronger predilection for spreading to the bones, genitourinary tract, and central nervous system, whereas histoplasmosis is a more frequent cause of polyarthrtitis and mesenteric adenopathy. The patient’s travel to the Central Valley, California raises the possibility of coccidioidomycosis, which typically starts with pulmonary disease prior to dissemination to bones, skin, and other less common sites. Pipe-fitters are predisposed to asbestos-related illnesses, including lung cancer and mesothelioma, which would not explain this patient’s presentation. Incarceration and high-risk sexual practices increase his risk for tuberculosis, HIV, and syphilis. Widespread skin involvement is more characteristic of syphilis or primary HIV infection than of disseminated fungal or mycobacterial infection.

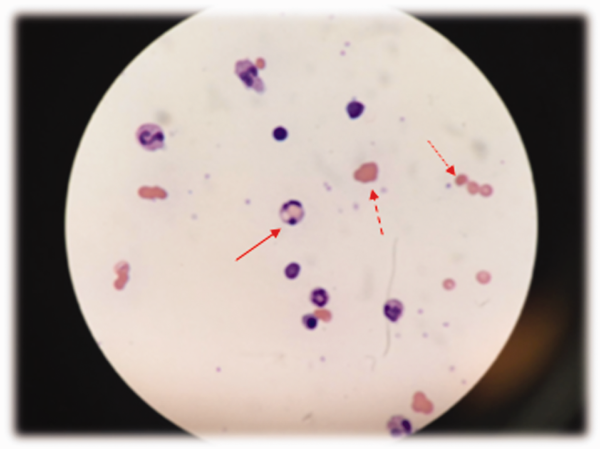

WBC measured 29,000/uL with a neutrophilic predominance. His peripheral blood smear was unremarkable. A comprehensive metabolic panel was normal. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 317 U/L (reference range 140-280 U/L). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 39 mm/hr (reference range < 20 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 66 mg/L (reference range <6.3 mg/L). Blood, urine, and throat cultures were sent. Chest radiograph showed clear lungs without adenopathy. Ankle and knee radiographs identified small effusions bilaterally without bony abnormalities. CT of his brain showed a small, hypodense lesion in the right lacrimal gland. A lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed absence of RBCs; WBC, 2/µL; protein, 35 mg/dL; glucose, 62 mg/dL; negative gram stain. CSF bacterial and fungal cultures, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction (HSV PCR), and cryptococcal antigen were sent for laboratory analysis. The patient was started on vancomycin and aztreonam.

Lesions of the lacrimal gland feature multiple causes, including autoimmune diseases (Sjögren’s, Behçet’s disease), granulomatous diseases (sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis), neoplasms (salivary gland tumors, lymphoma), and infections. Initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics is reasonable while awaiting additional information from blood and urine cultures, serologies for HIV and syphilis, and purified protein derivative or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

If these tests fail to reveal a diagnosis, the search for atypical infections and noninfectious possibilities should expand.

The patient continued to have intermittent fevers, sweats, and malaise over the next 3 days. All bacterial and fungal cultures remained negative, and antibiotics were discontinued. Rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, antinuclear antibody, and cryoglobulins were negative. Serum C3, C4, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin (RPR), HIV antibody, IGRA, and serum antibodies for Coccidioides, histoplasmosis, and West Nile virus were negative. Urine nucleic acid amplification testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia was negative. CSF VDRL, HSV PCR and cryptococcal antigen were negative. HSV culture from an oral ulcer showed no growth. The patient had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 3 million virus equivalents/mL.

The additional test results lower

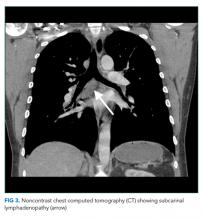

The most likely diagnosis is Löfgren’s syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis characterized by erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and polyarthralgias or polyarthritis. Löfgren’s syndrome may include fevers, uveitis, widespread skin lesions and other systemic manifestations. Sarcoidosis could explain the lacrimal gland lesion, and could manifest with recurrent kidney stones. Oral lesions may occur in sarcoidosis. A normal serum ACE level may be observed in up to half of patients. The lack of visualized granulomas on the submental node FNA may reflect sampling error, lower likelihood of visualizing granulomas on FNA (compared with excisional biopsy), or biopsy location (hilar nodes are more likely to demonstrate sarcoid granulomas).

Although Löfgren’s syndrome is often self-limited, treatment can ameliorate symptoms. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication can be tried first, with prednisone reserved for refractory cases.

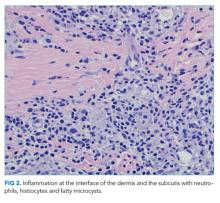

The constellation of bilateral hilar adenopathy, arthritis, and erythema nodosum was consistent with Löfgren’s syndrome, further supported by granulomatous infiltrates on biopsy. The patient’s symptoms resolved with naproxen. He was scheduled for follow-up in dermatology and rheumatology clinics and was referred to hepatology for management of hepatitis C.

COMMENTARY

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. The disease derives its name from Boeck’s 1899 report describing benign cutaneous lesions that resembled sarcomas.1 Sarcoidosis most commonly manifests as bilateral hilar adenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates, but may impact any tissue or organ, including the eyes, nonhilar lymph nodes, liver, spleen, joints, mucous membranes, and skin. Nephrolithiasis may result from hypercalcemia and/or hypercalciuria (related to granulomatous production of 1,25 vitamin D) and can be the presenting feature of sarcoidosis.2 Less common presentations include neurologic sarcoidosis (which can present with seizures, aseptic meningitis, encephalopathy, neuroendocrine dysfunction, myelopathy and peripheral neuropathies), cardiac sarcoidosis (which may present with arrhythmias, valvular dysfunction, heart failure, ischemia, or pericardial disease), and Heerfordt syndrome (the constellation of parotid gland enlargement, facial palsy, anterior uveitis, and fever). Sarcoidosis may mimic other diseases, including malignancy, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and infiltrative tuberculosis.3 Sarcoidosis-like reactions have occurred in response to malignancy and medications.4

The patient’s rash demonstrated a predilection for areas of prior scarring, which has a limited differential diagnosis. Keloids and hypertrophic scars occur at sites of former surgical wounds, lacerations, or areas of inflammation. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is a benign inflammatory condition where papules cluster in areas of prior striae. Cutaneous lesions of Behçet’s syndrome display pathergy, where pustular response is observed at sites of injury. Granulomatous infiltration in sarcoidosis may demonstrate a predilection for scars and tattoos (ie, scar or tattoo sarcoidosis).5 Sarcoidosis can have other cutaneous manifestations, including psoriaform, ulcerative, or erythrodermic lesions; subcutaneous nodules; scarring or nonscarring alopecia; and lupus pernio – violaceous, nodular and plaque-like lesions on the nose, earlobes, cheeks, and digits.5

Löfgren’s syndrome is a distinct variant of sarcoidosis.In 1952, Dr. Löfgren described a case series of patients with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and coexisting erythema nodosum and polyarthralgia.6 The epidemiology favors young women.7 Patients with Löfgren’s syndrome present acutely (as in this case), which differs from the typical subacute course observed with sarcoidosis. In addition to the classic presentation described above, patients with Löfgren’s syndrome may demonstrate additional manifestations of sarcoidosis, including fevers, peripheral adenopathy, arthritis, and granulomatous skin lesions. Painful symptoms may require short-term anti-inflammatory treatments. Most patients do not require systemic immunosuppression. Symptoms usually decrease over several months, and the majority of patients experience complete remission within years. Rare recurrences have been described up to several years.8

In confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, current guidelines recommend exclusion of other diseases that present similarly, a work-up that generally includes compatible laboratory tests and imaging, and histologic demonstration of noncaseating granulomas.9 However, Löfgren’s syndrome is a notable exception. The constellation of fever, bilateral hilar adenopathy, polyarthralgia, and erythema nodosum suffices to diagnose Löfgren’s syndrome as long as the disease remits rapidly and spontaneously.9 Thus, in this case, although granulomatous infiltrates were confirmed on biopsy, the diagnosis of Löfgren’s syndrome could have been based on clinical and radiologic features alone.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

- Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that most commonly presents with bilateral hilar adenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates but can also present atypically, including with nephrolithiasis from hypercalcemia, neurologic syndromes, and cardiac involvement.

- Löfgren’s syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis, is characterized by relatively acute onset of fevers, erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar adenopathy, and polyarthralgia or polyarthritis. Most patients recover and manifest complete remission.

- A limited differential exists for rashes with a predilection for areas of tattoos and prior scarring, including keloids, PUPPP, Behçet’s disease, and granulomatous infiltration.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

1. Multiple Benign Sarcoids of the Skin. JAMA. 1899;XXXIII(26):1620-1621.

2. Rizzato G, Fraioli P, Montemurro L. Nephrolithiasis as a presenting feature of chronic sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1995;50(5):555-559. PubMed

3. Romanov V. Atypical variants of clinical course of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(58):3782. PubMed

4. Arish N, Kuint R, Sapir E, et al. Characteristics of Sarcoidosis in Patients with Previous Malignancy: Causality or Coincidence? Respiration. 2017;93(4):247-252. PubMed

5. Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(3):295-302. PubMed

6. Löfgren S. The Bilateral Hilar Lymphoma Syndrome. Acta Med Scand. 1952;142(4):265-273. PubMed

7. Mañá J, Gómez-Vaquero C, Montero A et al. Löfgren’s syndrome revisited: a study of 186 patients. Am J Med. 1999;107(3):240-245. PubMed

8. Gran J, Bohmer E. Acute Sarcoid Arthritis: A Favourable Outcome? Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25(2):70-73. PubMed

9. American Thoracic Society. Statement on Sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.Otate voluptiatia qui aut iur, utendi quiae incipis m PubMed

A 43-year-old man with a history of asplenia, hepatitis C, and nephrolithiasis reported right-flank pain. He described severe, sharp pain that came in waves and radiated to the right groin, associated with nausea and nonbloody emesis. He noted “pink urine” but no dysuria. He had 4prior similar episodes during which he had passed kidney stones, although stone analysis had never been performed. He denied having fevers or chills.

The patient had been involved in a remote motor vehicle accident complicated by splenic laceration, for which he underwent splenectomy. He was appropriately immunized. The patient also suffered from bipolar affective disorder and untreated chronic hepatitis C infection with no evidence of cirrhosis. He smoked one pack of tobacco per day for the last 10 years and reported distant alcohol and methamphetamine use.

Right-flank pain can arise from conditions affecting the lower thorax (effusion, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism), abdomen (hepatobiliary or intestinal disease), retroperitoneum (hemorrhage or infection), musculoskeletal system, peripheral nerves (herpes zoster), or the genitourinary system (pyelonephritis). Pain radiating to the groin, discolored urine (suggesting hematuria), and history of kidney stones increase the likelihood of renal colic from nephrolithiasis.

Less commonly, flank pain and hematuria may present as initial symptoms of renal cell carcinoma, renal infarction, or aortic dissection. The patient’s immunosuppression from asplenia and active injection drug use could predispose him to septic emboli to his kidneys. Prior trauma causing aortic injury could predispose himto subsequent dissection.

The patient appeared well with a heart rate of 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 122/76 mmHg, temperature 36.8°C, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. His cardiopulmonary and abdominal examinations were normal, and he had no costovertebral angle tenderness. His skin was warm and dry without rashes. His white blood cell (WBC) count was 26,000/μL; absolute neutrophil count was 22,000/μL. Serum chemistries were normal, including creatinine 0.63 mg/dL, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, and phosphorus 3.1 mg/dL. Lactate was 0.8 mmol/L (reference range: 0-2.0 mmol/L). Urinalysis revealed large ketones, >50 red blood cells (RBC) per high power field (HPF), <5 WBC per HPF, 1+ calcium oxalate crystals and pH 6.0. A bedside ultrasound showed mild right hydronephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated diffuse, mildly prominent subcentimeter mesenteric lymphadenopathy and no kidney stones. He was treated with intravenous fluids and pain control, and was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of a passed kidney stone.

A passed stone would not explain this degree of leukocytosis. The CT results reduce the likelihood of a renal neoplasm, renal infarction, or pyelonephritis. Mesenteric lymphadenopathy is nonspecific, but it may signal underlying infection or malignancy with spread to lymph nodes, or it may be part of a systemic disorder causing generalized lymphadenopathy. Malignant causes of mesenteric lymphadenopathy (with no apparent primary tumor) include testicular cancer, lymphoma, and primary urogenital neoplasms.

The lower extremity nodules are consistent with erythema nodosum, which may be observed in numerous infectious and noninfectious illnesses. The rapid tempo of this febrile illness mandates early consideration of infection. Splenectomized patients are at risk for overwhelming post-splenectomy infection from encapsulated organisms, although this risk is significantly mitigated with appropriate immunization. The patient is at risk of bacterial endocarditis, which could explain his fevers and polyarthritis, although plaques, pustules, and oral ulcers would be unusual. Disseminated gonococcal infection causes fevers, oral lesions, polyarthritis and pustular skin lesions, but plaques are uncommon. Disseminated mycobacterial and fungal infections may cause oral ulcers, but affected patients tend to be severely ill and have profound immunosuppression. Secondary syphilis may account for many of the findings; however, oral ulcers would be unusual, and the rash tends to be more widespread, with a predilection for the palms and soles. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can cause oral ulcers and is the chief viral etiology to consider.

Noninfectious illnesses to consider include neoplasms and connective tissue diseases. Malignancy would be unlikely to manifest this abruptly or produce a paraneoplastic disorder with these features.

The patient described severe fatigue and drenching night sweats for two months prior to admission. He denied dyspnea or cough. He was born in the southwestern United States and had lived in California for almost a decade. He had been incarcerated for a few years and released three years prior. He had intermittently lived in homeless shelters, but currently lived alone in downtown San Francisco. He had traveled remotely to the Caribbean, and more recently traveled frequently to the Central Valley in California. The patient formerly worked as a pipe-fitter and welder. He denied animal exposure or recent sick contacts. He was sexually active with women, and intermittently used barrier protection.

His years in the southwestern United States may have exposed the patient to blastomycosis or histoplasmosis; both can mimic mycobacterial disease. Blastomycosis demonstrates a slightly stronger predilection for spreading to the bones, genitourinary tract, and central nervous system, whereas histoplasmosis is a more frequent cause of polyarthrtitis and mesenteric adenopathy. The patient’s travel to the Central Valley, California raises the possibility of coccidioidomycosis, which typically starts with pulmonary disease prior to dissemination to bones, skin, and other less common sites. Pipe-fitters are predisposed to asbestos-related illnesses, including lung cancer and mesothelioma, which would not explain this patient’s presentation. Incarceration and high-risk sexual practices increase his risk for tuberculosis, HIV, and syphilis. Widespread skin involvement is more characteristic of syphilis or primary HIV infection than of disseminated fungal or mycobacterial infection.

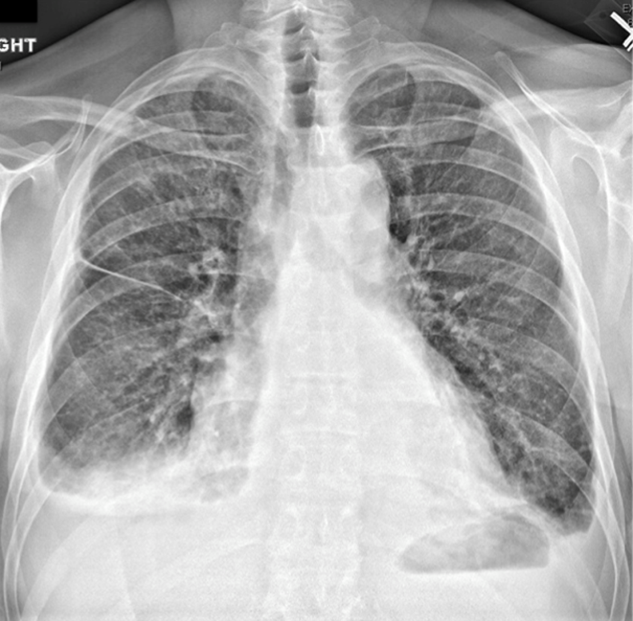

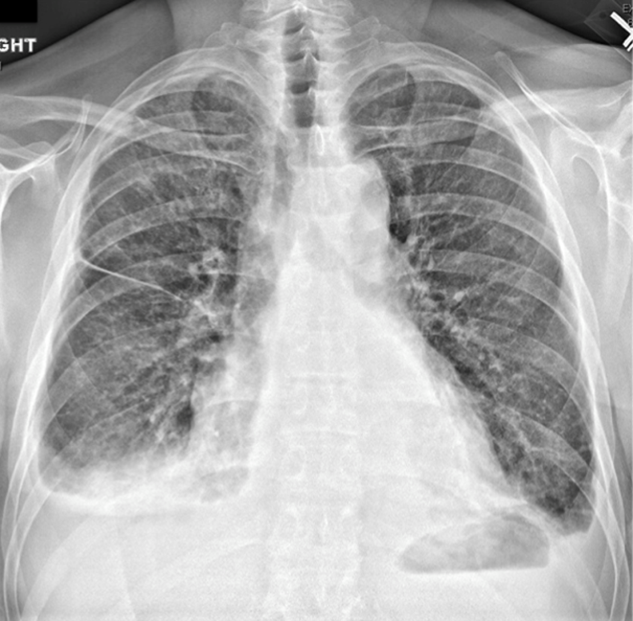

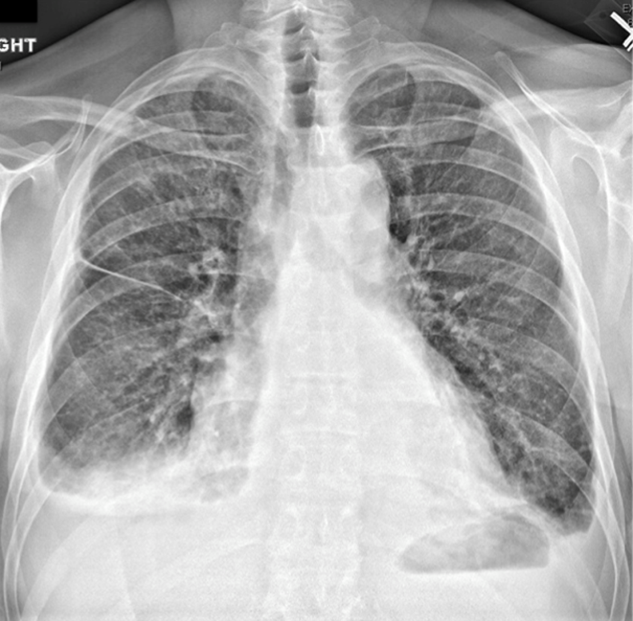

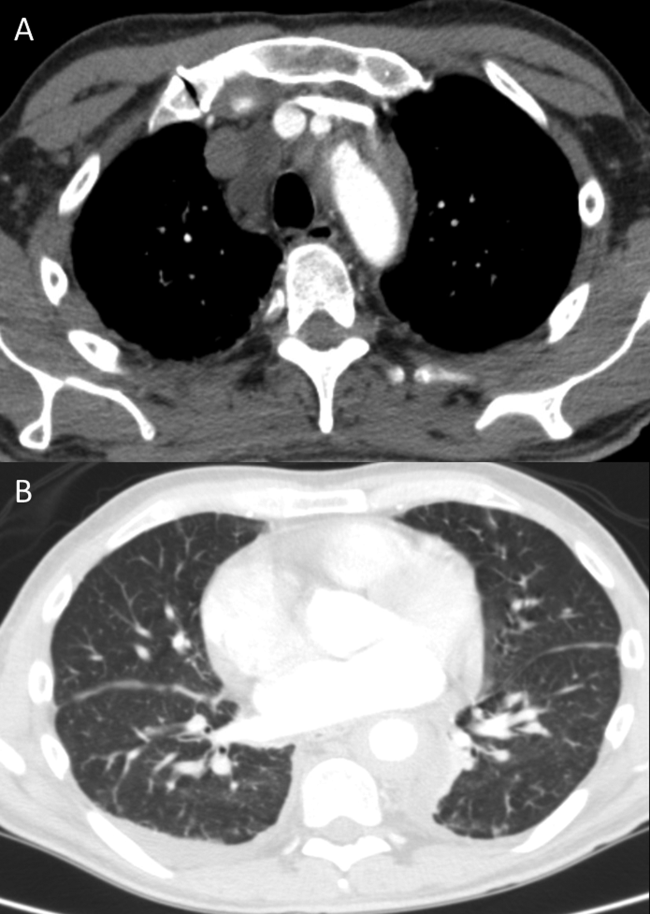

WBC measured 29,000/uL with a neutrophilic predominance. His peripheral blood smear was unremarkable. A comprehensive metabolic panel was normal. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 317 U/L (reference range 140-280 U/L). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 39 mm/hr (reference range < 20 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 66 mg/L (reference range <6.3 mg/L). Blood, urine, and throat cultures were sent. Chest radiograph showed clear lungs without adenopathy. Ankle and knee radiographs identified small effusions bilaterally without bony abnormalities. CT of his brain showed a small, hypodense lesion in the right lacrimal gland. A lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed absence of RBCs; WBC, 2/µL; protein, 35 mg/dL; glucose, 62 mg/dL; negative gram stain. CSF bacterial and fungal cultures, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction (HSV PCR), and cryptococcal antigen were sent for laboratory analysis. The patient was started on vancomycin and aztreonam.

Lesions of the lacrimal gland feature multiple causes, including autoimmune diseases (Sjögren’s, Behçet’s disease), granulomatous diseases (sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis), neoplasms (salivary gland tumors, lymphoma), and infections. Initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics is reasonable while awaiting additional information from blood and urine cultures, serologies for HIV and syphilis, and purified protein derivative or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

If these tests fail to reveal a diagnosis, the search for atypical infections and noninfectious possibilities should expand.

The patient continued to have intermittent fevers, sweats, and malaise over the next 3 days. All bacterial and fungal cultures remained negative, and antibiotics were discontinued. Rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, antinuclear antibody, and cryoglobulins were negative. Serum C3, C4, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin (RPR), HIV antibody, IGRA, and serum antibodies for Coccidioides, histoplasmosis, and West Nile virus were negative. Urine nucleic acid amplification testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia was negative. CSF VDRL, HSV PCR and cryptococcal antigen were negative. HSV culture from an oral ulcer showed no growth. The patient had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 3 million virus equivalents/mL.

The additional test results lower

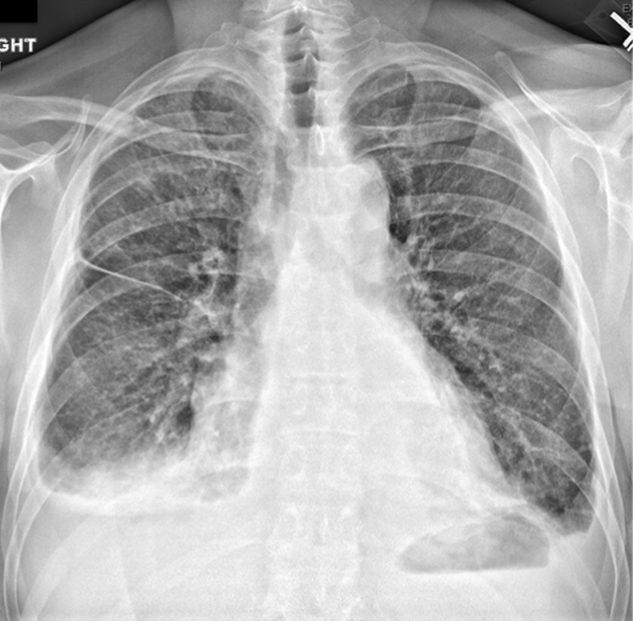

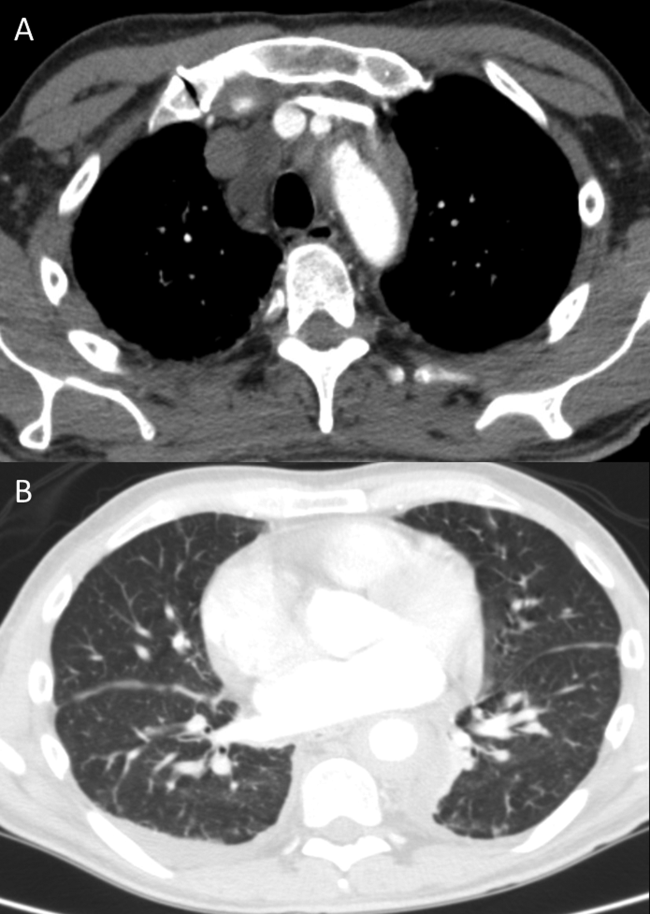

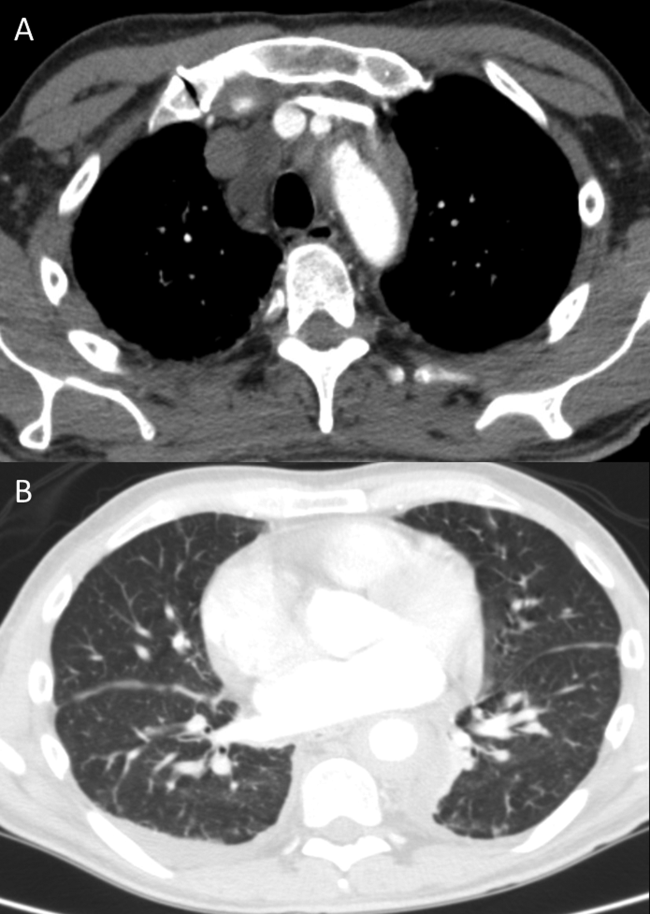

The most likely diagnosis is Löfgren’s syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis characterized by erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and polyarthralgias or polyarthritis. Löfgren’s syndrome may include fevers, uveitis, widespread skin lesions and other systemic manifestations. Sarcoidosis could explain the lacrimal gland lesion, and could manifest with recurrent kidney stones. Oral lesions may occur in sarcoidosis. A normal serum ACE level may be observed in up to half of patients. The lack of visualized granulomas on the submental node FNA may reflect sampling error, lower likelihood of visualizing granulomas on FNA (compared with excisional biopsy), or biopsy location (hilar nodes are more likely to demonstrate sarcoid granulomas).

Although Löfgren’s syndrome is often self-limited, treatment can ameliorate symptoms. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication can be tried first, with prednisone reserved for refractory cases.

The constellation of bilateral hilar adenopathy, arthritis, and erythema nodosum was consistent with Löfgren’s syndrome, further supported by granulomatous infiltrates on biopsy. The patient’s symptoms resolved with naproxen. He was scheduled for follow-up in dermatology and rheumatology clinics and was referred to hepatology for management of hepatitis C.

COMMENTARY

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. The disease derives its name from Boeck’s 1899 report describing benign cutaneous lesions that resembled sarcomas.1 Sarcoidosis most commonly manifests as bilateral hilar adenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates, but may impact any tissue or organ, including the eyes, nonhilar lymph nodes, liver, spleen, joints, mucous membranes, and skin. Nephrolithiasis may result from hypercalcemia and/or hypercalciuria (related to granulomatous production of 1,25 vitamin D) and can be the presenting feature of sarcoidosis.2 Less common presentations include neurologic sarcoidosis (which can present with seizures, aseptic meningitis, encephalopathy, neuroendocrine dysfunction, myelopathy and peripheral neuropathies), cardiac sarcoidosis (which may present with arrhythmias, valvular dysfunction, heart failure, ischemia, or pericardial disease), and Heerfordt syndrome (the constellation of parotid gland enlargement, facial palsy, anterior uveitis, and fever). Sarcoidosis may mimic other diseases, including malignancy, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and infiltrative tuberculosis.3 Sarcoidosis-like reactions have occurred in response to malignancy and medications.4

The patient’s rash demonstrated a predilection for areas of prior scarring, which has a limited differential diagnosis. Keloids and hypertrophic scars occur at sites of former surgical wounds, lacerations, or areas of inflammation. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is a benign inflammatory condition where papules cluster in areas of prior striae. Cutaneous lesions of Behçet’s syndrome display pathergy, where pustular response is observed at sites of injury. Granulomatous infiltration in sarcoidosis may demonstrate a predilection for scars and tattoos (ie, scar or tattoo sarcoidosis).5 Sarcoidosis can have other cutaneous manifestations, including psoriaform, ulcerative, or erythrodermic lesions; subcutaneous nodules; scarring or nonscarring alopecia; and lupus pernio – violaceous, nodular and plaque-like lesions on the nose, earlobes, cheeks, and digits.5

Löfgren’s syndrome is a distinct variant of sarcoidosis.In 1952, Dr. Löfgren described a case series of patients with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and coexisting erythema nodosum and polyarthralgia.6 The epidemiology favors young women.7 Patients with Löfgren’s syndrome present acutely (as in this case), which differs from the typical subacute course observed with sarcoidosis. In addition to the classic presentation described above, patients with Löfgren’s syndrome may demonstrate additional manifestations of sarcoidosis, including fevers, peripheral adenopathy, arthritis, and granulomatous skin lesions. Painful symptoms may require short-term anti-inflammatory treatments. Most patients do not require systemic immunosuppression. Symptoms usually decrease over several months, and the majority of patients experience complete remission within years. Rare recurrences have been described up to several years.8

In confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, current guidelines recommend exclusion of other diseases that present similarly, a work-up that generally includes compatible laboratory tests and imaging, and histologic demonstration of noncaseating granulomas.9 However, Löfgren’s syndrome is a notable exception. The constellation of fever, bilateral hilar adenopathy, polyarthralgia, and erythema nodosum suffices to diagnose Löfgren’s syndrome as long as the disease remits rapidly and spontaneously.9 Thus, in this case, although granulomatous infiltrates were confirmed on biopsy, the diagnosis of Löfgren’s syndrome could have been based on clinical and radiologic features alone.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

- Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that most commonly presents with bilateral hilar adenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates but can also present atypically, including with nephrolithiasis from hypercalcemia, neurologic syndromes, and cardiac involvement.

- Löfgren’s syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis, is characterized by relatively acute onset of fevers, erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar adenopathy, and polyarthralgia or polyarthritis. Most patients recover and manifest complete remission.

- A limited differential exists for rashes with a predilection for areas of tattoos and prior scarring, including keloids, PUPPP, Behçet’s disease, and granulomatous infiltration.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

A 43-year-old man with a history of asplenia, hepatitis C, and nephrolithiasis reported right-flank pain. He described severe, sharp pain that came in waves and radiated to the right groin, associated with nausea and nonbloody emesis. He noted “pink urine” but no dysuria. He had 4prior similar episodes during which he had passed kidney stones, although stone analysis had never been performed. He denied having fevers or chills.

The patient had been involved in a remote motor vehicle accident complicated by splenic laceration, for which he underwent splenectomy. He was appropriately immunized. The patient also suffered from bipolar affective disorder and untreated chronic hepatitis C infection with no evidence of cirrhosis. He smoked one pack of tobacco per day for the last 10 years and reported distant alcohol and methamphetamine use.

Right-flank pain can arise from conditions affecting the lower thorax (effusion, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism), abdomen (hepatobiliary or intestinal disease), retroperitoneum (hemorrhage or infection), musculoskeletal system, peripheral nerves (herpes zoster), or the genitourinary system (pyelonephritis). Pain radiating to the groin, discolored urine (suggesting hematuria), and history of kidney stones increase the likelihood of renal colic from nephrolithiasis.

Less commonly, flank pain and hematuria may present as initial symptoms of renal cell carcinoma, renal infarction, or aortic dissection. The patient’s immunosuppression from asplenia and active injection drug use could predispose him to septic emboli to his kidneys. Prior trauma causing aortic injury could predispose himto subsequent dissection.

The patient appeared well with a heart rate of 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 122/76 mmHg, temperature 36.8°C, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. His cardiopulmonary and abdominal examinations were normal, and he had no costovertebral angle tenderness. His skin was warm and dry without rashes. His white blood cell (WBC) count was 26,000/μL; absolute neutrophil count was 22,000/μL. Serum chemistries were normal, including creatinine 0.63 mg/dL, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, and phosphorus 3.1 mg/dL. Lactate was 0.8 mmol/L (reference range: 0-2.0 mmol/L). Urinalysis revealed large ketones, >50 red blood cells (RBC) per high power field (HPF), <5 WBC per HPF, 1+ calcium oxalate crystals and pH 6.0. A bedside ultrasound showed mild right hydronephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated diffuse, mildly prominent subcentimeter mesenteric lymphadenopathy and no kidney stones. He was treated with intravenous fluids and pain control, and was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of a passed kidney stone.

A passed stone would not explain this degree of leukocytosis. The CT results reduce the likelihood of a renal neoplasm, renal infarction, or pyelonephritis. Mesenteric lymphadenopathy is nonspecific, but it may signal underlying infection or malignancy with spread to lymph nodes, or it may be part of a systemic disorder causing generalized lymphadenopathy. Malignant causes of mesenteric lymphadenopathy (with no apparent primary tumor) include testicular cancer, lymphoma, and primary urogenital neoplasms.

The lower extremity nodules are consistent with erythema nodosum, which may be observed in numerous infectious and noninfectious illnesses. The rapid tempo of this febrile illness mandates early consideration of infection. Splenectomized patients are at risk for overwhelming post-splenectomy infection from encapsulated organisms, although this risk is significantly mitigated with appropriate immunization. The patient is at risk of bacterial endocarditis, which could explain his fevers and polyarthritis, although plaques, pustules, and oral ulcers would be unusual. Disseminated gonococcal infection causes fevers, oral lesions, polyarthritis and pustular skin lesions, but plaques are uncommon. Disseminated mycobacterial and fungal infections may cause oral ulcers, but affected patients tend to be severely ill and have profound immunosuppression. Secondary syphilis may account for many of the findings; however, oral ulcers would be unusual, and the rash tends to be more widespread, with a predilection for the palms and soles. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can cause oral ulcers and is the chief viral etiology to consider.

Noninfectious illnesses to consider include neoplasms and connective tissue diseases. Malignancy would be unlikely to manifest this abruptly or produce a paraneoplastic disorder with these features.

The patient described severe fatigue and drenching night sweats for two months prior to admission. He denied dyspnea or cough. He was born in the southwestern United States and had lived in California for almost a decade. He had been incarcerated for a few years and released three years prior. He had intermittently lived in homeless shelters, but currently lived alone in downtown San Francisco. He had traveled remotely to the Caribbean, and more recently traveled frequently to the Central Valley in California. The patient formerly worked as a pipe-fitter and welder. He denied animal exposure or recent sick contacts. He was sexually active with women, and intermittently used barrier protection.

His years in the southwestern United States may have exposed the patient to blastomycosis or histoplasmosis; both can mimic mycobacterial disease. Blastomycosis demonstrates a slightly stronger predilection for spreading to the bones, genitourinary tract, and central nervous system, whereas histoplasmosis is a more frequent cause of polyarthrtitis and mesenteric adenopathy. The patient’s travel to the Central Valley, California raises the possibility of coccidioidomycosis, which typically starts with pulmonary disease prior to dissemination to bones, skin, and other less common sites. Pipe-fitters are predisposed to asbestos-related illnesses, including lung cancer and mesothelioma, which would not explain this patient’s presentation. Incarceration and high-risk sexual practices increase his risk for tuberculosis, HIV, and syphilis. Widespread skin involvement is more characteristic of syphilis or primary HIV infection than of disseminated fungal or mycobacterial infection.

WBC measured 29,000/uL with a neutrophilic predominance. His peripheral blood smear was unremarkable. A comprehensive metabolic panel was normal. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 317 U/L (reference range 140-280 U/L). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 39 mm/hr (reference range < 20 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 66 mg/L (reference range <6.3 mg/L). Blood, urine, and throat cultures were sent. Chest radiograph showed clear lungs without adenopathy. Ankle and knee radiographs identified small effusions bilaterally without bony abnormalities. CT of his brain showed a small, hypodense lesion in the right lacrimal gland. A lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed absence of RBCs; WBC, 2/µL; protein, 35 mg/dL; glucose, 62 mg/dL; negative gram stain. CSF bacterial and fungal cultures, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction (HSV PCR), and cryptococcal antigen were sent for laboratory analysis. The patient was started on vancomycin and aztreonam.

Lesions of the lacrimal gland feature multiple causes, including autoimmune diseases (Sjögren’s, Behçet’s disease), granulomatous diseases (sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis), neoplasms (salivary gland tumors, lymphoma), and infections. Initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics is reasonable while awaiting additional information from blood and urine cultures, serologies for HIV and syphilis, and purified protein derivative or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

If these tests fail to reveal a diagnosis, the search for atypical infections and noninfectious possibilities should expand.

The patient continued to have intermittent fevers, sweats, and malaise over the next 3 days. All bacterial and fungal cultures remained negative, and antibiotics were discontinued. Rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, antinuclear antibody, and cryoglobulins were negative. Serum C3, C4, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin (RPR), HIV antibody, IGRA, and serum antibodies for Coccidioides, histoplasmosis, and West Nile virus were negative. Urine nucleic acid amplification testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia was negative. CSF VDRL, HSV PCR and cryptococcal antigen were negative. HSV culture from an oral ulcer showed no growth. The patient had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 3 million virus equivalents/mL.

The additional test results lower

The most likely diagnosis is Löfgren’s syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis characterized by erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and polyarthralgias or polyarthritis. Löfgren’s syndrome may include fevers, uveitis, widespread skin lesions and other systemic manifestations. Sarcoidosis could explain the lacrimal gland lesion, and could manifest with recurrent kidney stones. Oral lesions may occur in sarcoidosis. A normal serum ACE level may be observed in up to half of patients. The lack of visualized granulomas on the submental node FNA may reflect sampling error, lower likelihood of visualizing granulomas on FNA (compared with excisional biopsy), or biopsy location (hilar nodes are more likely to demonstrate sarcoid granulomas).

Although Löfgren’s syndrome is often self-limited, treatment can ameliorate symptoms. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication can be tried first, with prednisone reserved for refractory cases.

The constellation of bilateral hilar adenopathy, arthritis, and erythema nodosum was consistent with Löfgren’s syndrome, further supported by granulomatous infiltrates on biopsy. The patient’s symptoms resolved with naproxen. He was scheduled for follow-up in dermatology and rheumatology clinics and was referred to hepatology for management of hepatitis C.

COMMENTARY

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. The disease derives its name from Boeck’s 1899 report describing benign cutaneous lesions that resembled sarcomas.1 Sarcoidosis most commonly manifests as bilateral hilar adenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates, but may impact any tissue or organ, including the eyes, nonhilar lymph nodes, liver, spleen, joints, mucous membranes, and skin. Nephrolithiasis may result from hypercalcemia and/or hypercalciuria (related to granulomatous production of 1,25 vitamin D) and can be the presenting feature of sarcoidosis.2 Less common presentations include neurologic sarcoidosis (which can present with seizures, aseptic meningitis, encephalopathy, neuroendocrine dysfunction, myelopathy and peripheral neuropathies), cardiac sarcoidosis (which may present with arrhythmias, valvular dysfunction, heart failure, ischemia, or pericardial disease), and Heerfordt syndrome (the constellation of parotid gland enlargement, facial palsy, anterior uveitis, and fever). Sarcoidosis may mimic other diseases, including malignancy, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and infiltrative tuberculosis.3 Sarcoidosis-like reactions have occurred in response to malignancy and medications.4

The patient’s rash demonstrated a predilection for areas of prior scarring, which has a limited differential diagnosis. Keloids and hypertrophic scars occur at sites of former surgical wounds, lacerations, or areas of inflammation. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is a benign inflammatory condition where papules cluster in areas of prior striae. Cutaneous lesions of Behçet’s syndrome display pathergy, where pustular response is observed at sites of injury. Granulomatous infiltration in sarcoidosis may demonstrate a predilection for scars and tattoos (ie, scar or tattoo sarcoidosis).5 Sarcoidosis can have other cutaneous manifestations, including psoriaform, ulcerative, or erythrodermic lesions; subcutaneous nodules; scarring or nonscarring alopecia; and lupus pernio – violaceous, nodular and plaque-like lesions on the nose, earlobes, cheeks, and digits.5

Löfgren’s syndrome is a distinct variant of sarcoidosis.In 1952, Dr. Löfgren described a case series of patients with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and coexisting erythema nodosum and polyarthralgia.6 The epidemiology favors young women.7 Patients with Löfgren’s syndrome present acutely (as in this case), which differs from the typical subacute course observed with sarcoidosis. In addition to the classic presentation described above, patients with Löfgren’s syndrome may demonstrate additional manifestations of sarcoidosis, including fevers, peripheral adenopathy, arthritis, and granulomatous skin lesions. Painful symptoms may require short-term anti-inflammatory treatments. Most patients do not require systemic immunosuppression. Symptoms usually decrease over several months, and the majority of patients experience complete remission within years. Rare recurrences have been described up to several years.8

In confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, current guidelines recommend exclusion of other diseases that present similarly, a work-up that generally includes compatible laboratory tests and imaging, and histologic demonstration of noncaseating granulomas.9 However, Löfgren’s syndrome is a notable exception. The constellation of fever, bilateral hilar adenopathy, polyarthralgia, and erythema nodosum suffices to diagnose Löfgren’s syndrome as long as the disease remits rapidly and spontaneously.9 Thus, in this case, although granulomatous infiltrates were confirmed on biopsy, the diagnosis of Löfgren’s syndrome could have been based on clinical and radiologic features alone.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

- Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that most commonly presents with bilateral hilar adenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates but can also present atypically, including with nephrolithiasis from hypercalcemia, neurologic syndromes, and cardiac involvement.

- Löfgren’s syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis, is characterized by relatively acute onset of fevers, erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar adenopathy, and polyarthralgia or polyarthritis. Most patients recover and manifest complete remission.

- A limited differential exists for rashes with a predilection for areas of tattoos and prior scarring, including keloids, PUPPP, Behçet’s disease, and granulomatous infiltration.

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

1. Multiple Benign Sarcoids of the Skin. JAMA. 1899;XXXIII(26):1620-1621.

2. Rizzato G, Fraioli P, Montemurro L. Nephrolithiasis as a presenting feature of chronic sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1995;50(5):555-559. PubMed

3. Romanov V. Atypical variants of clinical course of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(58):3782. PubMed

4. Arish N, Kuint R, Sapir E, et al. Characteristics of Sarcoidosis in Patients with Previous Malignancy: Causality or Coincidence? Respiration. 2017;93(4):247-252. PubMed

5. Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(3):295-302. PubMed

6. Löfgren S. The Bilateral Hilar Lymphoma Syndrome. Acta Med Scand. 1952;142(4):265-273. PubMed

7. Mañá J, Gómez-Vaquero C, Montero A et al. Löfgren’s syndrome revisited: a study of 186 patients. Am J Med. 1999;107(3):240-245. PubMed

8. Gran J, Bohmer E. Acute Sarcoid Arthritis: A Favourable Outcome? Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25(2):70-73. PubMed

9. American Thoracic Society. Statement on Sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.Otate voluptiatia qui aut iur, utendi quiae incipis m PubMed

1. Multiple Benign Sarcoids of the Skin. JAMA. 1899;XXXIII(26):1620-1621.

2. Rizzato G, Fraioli P, Montemurro L. Nephrolithiasis as a presenting feature of chronic sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1995;50(5):555-559. PubMed

3. Romanov V. Atypical variants of clinical course of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(58):3782. PubMed

4. Arish N, Kuint R, Sapir E, et al. Characteristics of Sarcoidosis in Patients with Previous Malignancy: Causality or Coincidence? Respiration. 2017;93(4):247-252. PubMed

5. Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(3):295-302. PubMed

6. Löfgren S. The Bilateral Hilar Lymphoma Syndrome. Acta Med Scand. 1952;142(4):265-273. PubMed

7. Mañá J, Gómez-Vaquero C, Montero A et al. Löfgren’s syndrome revisited: a study of 186 patients. Am J Med. 1999;107(3):240-245. PubMed

8. Gran J, Bohmer E. Acute Sarcoid Arthritis: A Favourable Outcome? Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25(2):70-73. PubMed

9. American Thoracic Society. Statement on Sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736-755.Otate voluptiatia qui aut iur, utendi quiae incipis m PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Prescription for Note Bloat: An Effective Progress Note Template

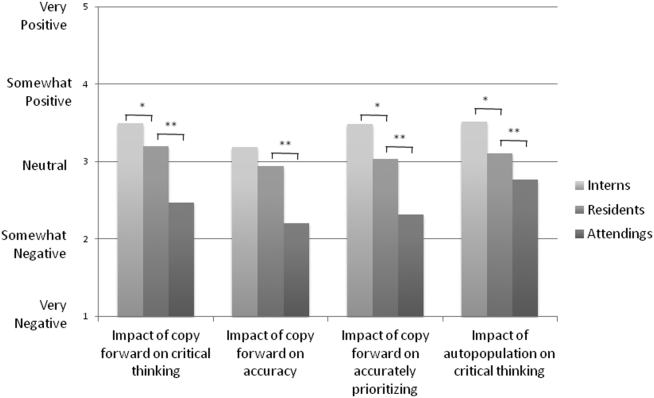

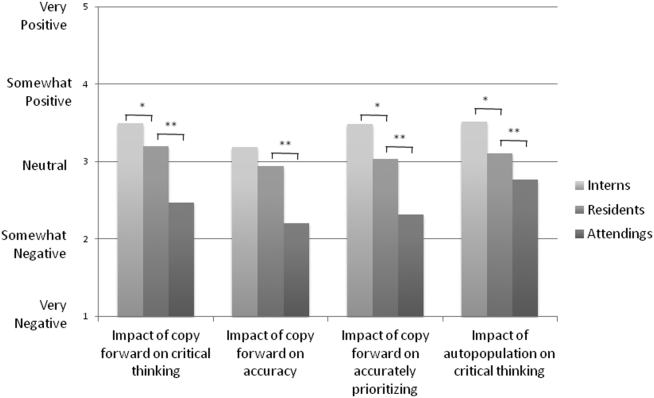

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) has led to significant progress in the modernization of healthcare delivery. Ease of access has improved clinical efficiency, and digital data have allowed for point-of-care decision support tools ranging from predicting the 30-day risk of readmission to providing up-to-date guidelines for the care of various diseases.1,2 Documentation tools such as copy-forward and autopopulation increase the speed of documentation, and typed notes improve legibility and ease of note transmission.3,4

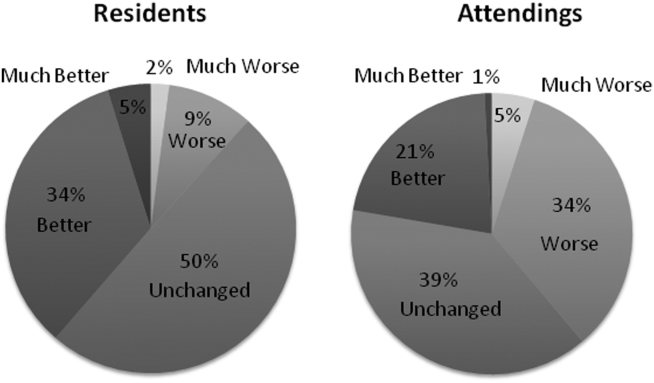

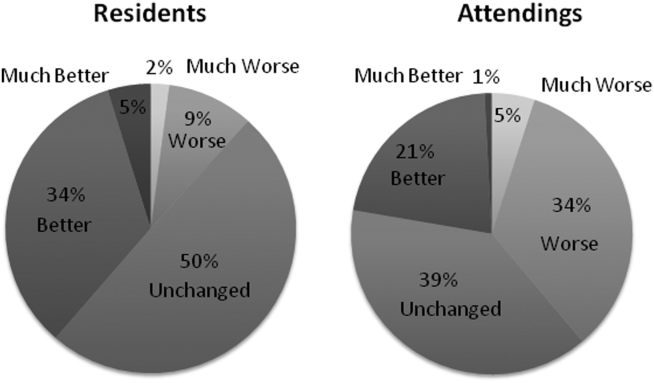

However, all of these benefits come with a potential for harm, particularly with respect to accurate and concise documentation. Many experts have described the perpetuation of false information leading to errors, copying-forward of inconsistent and outdated information, and the phenomenon of “note bloat” — physician notes that contain multiple pages of nonessential information, often leaving key aspects buried or lost.5-7 Providers seem to recognize the hazards of copy-and-paste functionality yet persist in utilizing it. In 1 survey, more than 70% of attendings and residents felt that copy and paste led to inaccurate and outdated information, yet 80% stated they would still use it.8

There is little evidence to guide institutions on ways to improve EHR documentation practices. Recent studies have shown that operative note templates improved documentation and decreased the number of missing components.9,10 In the nonoperative setting, 1 small pilot study of pediatric interns demonstrated that a bundled intervention composed of a note template and classroom teaching resulted in improvement in overall note quality and a decrease in “note clutter.”11 In a larger study of pediatric residents, a standardized and simplified note template resulted in a shorter note, although notes were completed later in the day.12 The present study seeks to build upon these efforts by investigating the effect of didactic teaching and an electronic progress note template on note quality, length, and timeliness across 4 academic internal medicine residency programs.

METHODS

Study Design

This prospective quality improvement study took place across 4 academic institutions: University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), University of California San Francisco (UCSF), University of California San Diego (UCSD), and University of Iowa, all of which use Epic EHR (Epic Corp., Madison, WI). The intervention combined brief educational conferences directed at housestaff and attendings with the implementation of an electronic progress note template. Guided by resident input, a note-writing task force at UCSF and UCLA developed a set of best practice guidelines and an aligned note template for progress notes (supplementary Appendix 1). UCSD and the University of Iowa adopted them at their respective institutions. The template’s design minimized autopopulation while encouraging providers to enter relevant data via free text fields (eg, physical exam), prompts (eg, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…”), and drop-down menus (eg, deep vein thrombosis [DVT] prophylaxis: enoxaparin, heparin subcutaneously, etc; supplementary Appendix 2). Additionally, an inpatient checklist was included at the end of the note to serve as a reminder for key inpatient concerns and quality measures, such as Foley catheter days, discharge planning, and code status. Lectures that focused on issues with documentation in the EHR, the best practice guidelines, and a review of the note template with instructions on how to access it were presented to the housestaff. Each institution tailored the lecture to suit their culture. Housestaff were encouraged but not required to use the note template.

Selection and Grading of Progress Notes

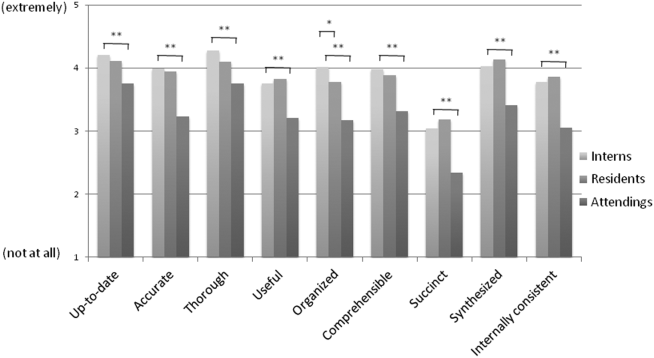

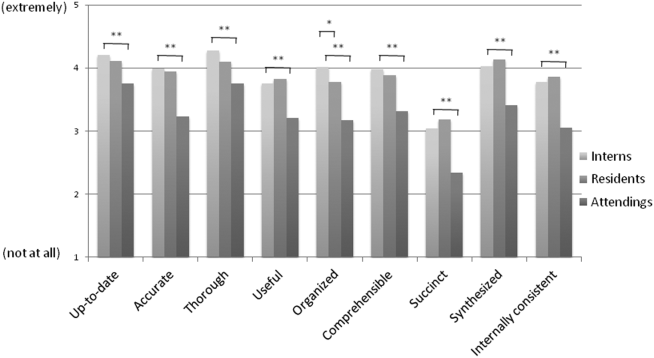

Progress notes were eligible for the study if they were written by an intern on an internal medicine teaching service, from a patient with a hospitalization length of at least 3 days with a progress note selected from hospital day 2 or 3, and written while the patient was on the general medicine wards. The preintervention notes were authored from September 2013 to December 2013 and the postintervention notes from April 2014 to June 2014. One note was selected per patient and no more than 3 notes were selected per intern. Each institution selected the first 50 notes chronologically that met these criteria for both the preintervention and the postintervention periods, for a total of 400 notes. The note-grading tool consisted of the following 3 sections to analyze note quality: (1) a general impression of the note (eg, below average, average, above average); (2) the validated Physician Documentation Quality Instrument, 9-item version (PDQI-9) that evaluates notes on 9 domains (up to date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, internally consistent) on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely); and (3) a note competency questionnaire based on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency note checklist that asked yes or no questions about best practice elements (eg, is there a relevant and focused physical exam).12

Graders were internal medicine teaching faculty involved in the study and were assigned to review notes from their respective sites by directly utilizing the EHR. Although this introduces potential for bias, it was felt that many of the grading elements required the grader to know details of the patient that would not be captured if the note was removed from the context of the EHR. Additionally, graders documented note length (number of lines of text), the time signed by the housestaff, and whether the template was used. Three different graders independently evaluated each note and submitted ratings by using Research Electronic Data Capture.13

Statistical Analysis

Means for each item on the grading tool were computed across raters for each progress note. These were summarized by institution as well as by pre- and postintervention. Cumulative logit mixed effects models were used to compare item responses between study conditions. The number of lines per note before and after the note template intervention was compared by using a mixed effects negative binomial regression model. The timestamp on each note, representing the time of day the note was signed, was compared pre- and postintervention by using a linear mixed effects model. All models included random note and rater effects, and fixed institution and intervention period effects, as well as their interaction. Inter-rater reliability of the grading tool was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using the estimated variance components. Data obtained from the PDQI-9 portion were analyzed by individual components as well as by sum score combining each component. The sum score was used to generate odds ratios to assess the likelihood that postintervention notes that used the template compared to those that did not would increase PDQI-9 sum scores. Both cumulative and site-specific data were analyzed. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

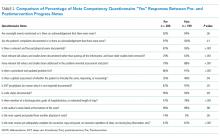

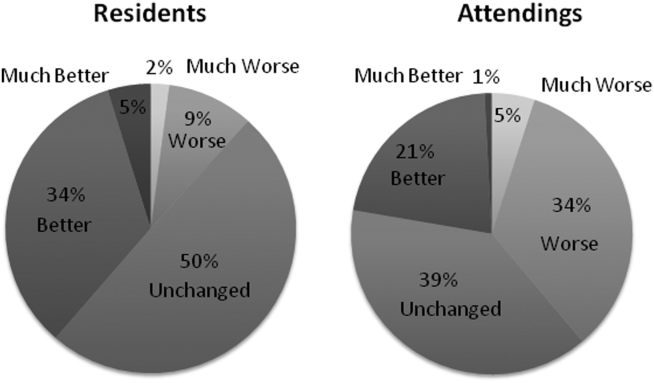

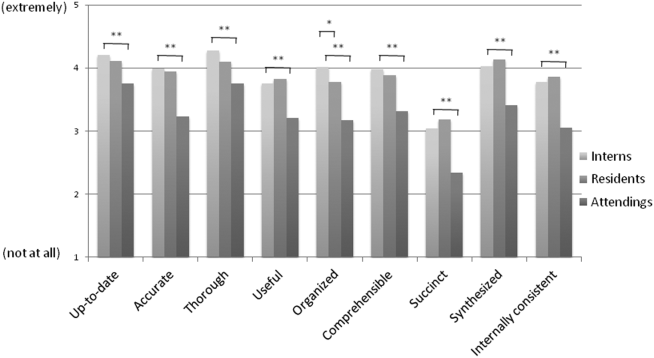

The mean general impression score significantly improved from 2.0 to 2.3 (on a 1-3 scale in which 2 is average) after the intervention (P < .001). Additionally, note quality significantly improved across each domain of the PDQI-9 (P < .001 for all domains, Table 1). The ICC was 0.245 for the general impression score and 0.143 for the PDQI-9 sum score.

Three of 4 institutions documented the number of lines per note and the time the note was signed by the intern. Mean number of lines per note decreased by 25% (361 lines preintervention, 265 lines postintervention, P < .001). Mean time signed was approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes earlier in the day (3:27

Site-specific data revealed variation between sites. Template use was 92% at UCSF, 90% at UCLA, 79% at Iowa, and 21% at UCSD. The mean general impression score significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and UCSD, but not at Iowa. The PDQI-9 score improved across all domains at UCSF and UCLA, 2 domains at UCSD, and 0 domains at Iowa. Documentation of pertinent labs and studies significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and Iowa, but not UCSD. Note length decreased at UCSF and UCLA, but not at UCSD. Notes were signed earlier at UCLA and UCSD, but not at UCSF.

When comparing postintervention notes based on template use, notes that used the template were significantly more likely to receive a higher mean impression score (odds ratio [OR] 11.95, P < .001), higher PDQI-9 sum score (OR 3.05, P < .001), be approximately 25% shorter (326 lines vs 239 lines, P < .001), and be completed approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes earlier (3:07

DISCUSSION

A bundled intervention consisting of educational lectures and a best practice progress note template significantly improved the quality, decreased the length, and resulted in earlier completion of inpatient progress notes. These findings are consistent with a prior study that demonstrated that a bundled note template intervention improved total note score and reduced note clutter.11 We saw a broad improvement in progress notes across all 9 domains of the PDQI-9, which corresponded with an improved general impression score. We also found statistically significant improvements in 7 of the 13 categories of the competency questionnaire.

Arguably the greatest impact of the intervention was shortening the documentation of labs and studies. Autopopulation can lead to the appearance of a comprehensive note; however, key data are often lost in a sea of numbers and imaging reports.6,14 Using simple prompts followed by free text such as, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…” reduced autopopulation and reminded housestaff to identify only the key information that affected patient care for that day, resulting in a more streamlined, clear, and high-yield note.

The time spent documenting care is an important consideration for physician workflow and for uptake of any note intervention.14-18 One study from 2016 revealed that internal medicine housestaff spend more than half of an average shift using the computer, with 52% of that time spent on documentation.17 Although functions such as autopopulation and copy-forward were created as efficiency tools, we hypothesize that they may actually prolong note writing time by leading to disorganized, distended notes that are difficult to use the following day. There was concern that limiting these “efficiency functions” might discourage housestaff from using the progress note template. It was encouraging to find that postintervention notes were signed 1.3 hours earlier in the day. This study did not measure the impact of shorter notes and earlier completion time, but in theory, this could allow interns to spend more time in direct patient care and to be at lower risk of duty hour violations.19 Furthermore, while the clinical impact of this is unknown, it is possible that timely note completion may improve patient care by making notes available earlier for consultants and other members of the care team.

We found that adding an “inpatient checklist” to the progress note template facilitated a review of key inpatient concerns and quality measures. Although we did not specifically compare before-and-after documentation of all of the components of the checklist, there appeared to be improvement in the domains measured. Notably, there was a 31% increase (P < .001) in the percentage of notes documenting the “discharge plan, goals of hospitalization, or estimated length of stay.” In the surgical literature, studies have demonstrated that incorporating checklists improves patient safety, the delivery of care, and potentially shortens the length of stay.20-22 Future studies should explore the impact of adding a checklist to the daily progress note, as there may be potential to improve both process and outcome measures.

Institution-specific data provided insightful results. UCSD encountered low template use among their interns; however, they still had evidence of improvement in note quality, though not at the same level of UCLA and UCSF. Some barriers to uptake identified were as follows: (1) interns were accustomed to import labs and studies into their note to use as their rounding report, and (2) the intervention took place late in the year when interns had developed a functional writing system that they were reluctant to change. The University of Iowa did not show significant improvement in their note quality despite a relatively high template uptake. Both of these outcomes raise the possibility that in addition to the template, there were other factors at play. Perhaps because UCSF and UCLA created the best practice guidelines and template, it was a better fit for their culture and they had more institutional buy-in. Or because the educational lectures were similar, but not standardized across institutions, some lectures may have been more effective than others. However, when evaluating the postintervention notes at UCSD and Iowa, templated notes were found to be much more likely to score higher on the PDQI-9 than nontemplated notes, which serves as evidence of the efficacy of the note template.

Some of the strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size spanning 4 institutions and the use of 3 different assessment tools for grading progress note quality (general impression score, PDQI-9, and competency note questionnaire). An additional strength is our unique finding suggesting that note writing may be more efficient by removing, rather than adding, “efficiency functions.” There were several limitations of this study. Pre- and postintervention notes were examined at different points in the same academic year, thus certain domains may have improved as interns progressed in clinical skill and comfort with documentation, independent of our intervention.21 However, our analysis of postintervention notes across the same time period revealed that use of the template was strongly associated with higher quality, shorter notes and earlier completion time arguing that the effect seen was not merely intern experience. The poor interrater reliability is also a limitation. Although the PDQI-9 was previously validated, future use of the grading tool may require more rater training for calibration or more objective wording.23 The study was not blinded, and thus, bias may have falsely elevated postintervention scores; however, we attempted to minimize bias by incorporating a more objective yes/no competency questionnaire and by having each note scored by 3 graders. Other studies have attempted to address this form of bias by printing out notes and blinding the graders. This design, however, isolates the note from all other data in the medical record, making it difficult to assess domains such as accuracy and completeness. Our inclusion of objective outcomes such as note length and time of note completion help to mitigate some of the bias.

Future research can expand on the results of this study by introducing similar progress note interventions at other institutions and/or in nonacademic environments to validate the results and expand generalizability. Longer term follow-up would be useful to determine if these effects are transient or long lasting. Similarly, it would be interesting to determine if such results are sustained even after new interns start suggesting that institutional culture can be changed. Investigators could focus on similar projects to improve other notes that are particularly at a high risk for propagating false information, such as the History and Physical or Discharge Summary. Future research should also focus on outcomes data, including whether a more efficient note can allow housestaff to spend more time with patients, decrease patient length of stay, reduce clinical errors, and improve educational time for trainees. Lastly, we should determine if interventions such as this can mitigate the widespread frustrations with electronic documentation that are associated with physician and provider burnout.15,24 One would hope that the technology could be harnessed to improve provider productivity and be effectively integrated into comprehensive patient care.

Our research makes progress toward recommendations made by the American College of Physicians “to improve accuracy of information recorded and the value of information,” and develop automated tools that “enhance documentation quality without facilitating improper behaviors.”19 Institutions should consider developing internal best practices for clinical documentation and building structured note templates.19 Our research would suggest that, combined with a small educational intervention, such templates can make progress notes more accurate and succinct, make note writing more efficient, and be harnessed to improve quality metrics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Michael Pfeffer, MD, and Sitaram Vangala, MS, for their contributions to and support of this research study and manuscript.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Herzig SJ, Guess JR, Feinbloom DB, et al. Improving appropriateness of acid-suppressive medication use via computerized clinical decision support. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):41-45. PubMed

2. Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Clark C, et al. Predicting all-cause readmissions using electronic health record data from the entire hospitalization: Model development and comparison. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):473-480. PubMed

3. Donati A, Gabbanelli V, Pantanetti S, et al. The impact of a clinical information system in an intensive care unit. J Clin Monit Comput. 2008;22(1):31-36. PubMed

4. Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1066-1069. PubMed

5. Hartzband P, Groopman J. Off the record--avoiding the pitfalls of going electronic. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1656-1658. PubMed

6. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. Copy-and-paste. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2335-2336. PubMed

7. Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. John Lennon’s elbow. JAMA. 2012;308(5):463-464. PubMed

8. O’Donnell HC, Kaushal R, Barrón Y, Callahan MA, Adelman RD, Siegler EL. Physicians’ attitudes towards copy and pasting in electronic note writing. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):63-68. PubMed

9. Mahapatra P, Ieong E. Improving Documentation and Communication Using Operative Note Proformas. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u209122.w3712. PubMed

10. Thomson DR, Baldwin MJ, Bellini MI, Silva MA. Improving the quality of operative notes for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Assessing the impact of a standardized operation note proforma. Int J Surg. 2016;27:17-20. PubMed

11. Dean SM, Eickhoff JC, Bakel LA. The effectiveness of a bundled intervention to improve resident progress notes in an electronic health record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):104-107. PubMed

12. Aylor M, Campbell EM, Winter C, Phillipi CA. Resident Notes in an Electronic Health Record: A Mixed-Methods Study Using a Standardized Intervention With Qualitative Analysis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;6(3):257-262.

13. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. PubMed

14. Chi J, Kugler J, Chu IM, et al. Medical students and the electronic health record: ‘an epic use of time’. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):891-895. PubMed

15. Martin SA, Sinsky CA. The map is not the territory: medical records and 21st century practice. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2053-2056. PubMed

16. Oxentenko AS, Manohar CU, McCoy CP, et al. Internal medicine residents’ computer use in the inpatient setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):529-532. PubMed

17. Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. How Do Residents Spend Their Shift Time? A Time and Motion Study With a Particular Focus on the Use of Computers. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):827-832. PubMed

18. Chen L, Guo U, Illipparambil LC, et al. Racing Against the Clock: Internal Medicine Residents’ Time Spent On Electronic Health Records. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):39-44. PubMed

19. Kuhn T, Basch P, Barr M, Yackel T, Physicians MICotACo. Clinical documentation in the 21st century: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):301-303. PubMed

20. Treadwell JR, Lucas S, Tsou AY. Surgical checklists: a systematic review of impacts and implementation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):299-318. PubMed

21. Ko HC, Turner TJ, Finnigan MA. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care teams in acute hospital settings--limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:211. PubMed

22. Diaz-Montes TP, Cobb L, Ibeanu OA, Njoku P, Gerardi MA. Introduction of checklists at daily progress notes improves patient care among the gynecological oncology service. J Patient Saf. 2012;8(4):189-193. PubMed

23. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing Electronic Note Quality Using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(2):164-174. PubMed

24. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013. PubMed

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) has led to significant progress in the modernization of healthcare delivery. Ease of access has improved clinical efficiency, and digital data have allowed for point-of-care decision support tools ranging from predicting the 30-day risk of readmission to providing up-to-date guidelines for the care of various diseases.1,2 Documentation tools such as copy-forward and autopopulation increase the speed of documentation, and typed notes improve legibility and ease of note transmission.3,4

However, all of these benefits come with a potential for harm, particularly with respect to accurate and concise documentation. Many experts have described the perpetuation of false information leading to errors, copying-forward of inconsistent and outdated information, and the phenomenon of “note bloat” — physician notes that contain multiple pages of nonessential information, often leaving key aspects buried or lost.5-7 Providers seem to recognize the hazards of copy-and-paste functionality yet persist in utilizing it. In 1 survey, more than 70% of attendings and residents felt that copy and paste led to inaccurate and outdated information, yet 80% stated they would still use it.8

There is little evidence to guide institutions on ways to improve EHR documentation practices. Recent studies have shown that operative note templates improved documentation and decreased the number of missing components.9,10 In the nonoperative setting, 1 small pilot study of pediatric interns demonstrated that a bundled intervention composed of a note template and classroom teaching resulted in improvement in overall note quality and a decrease in “note clutter.”11 In a larger study of pediatric residents, a standardized and simplified note template resulted in a shorter note, although notes were completed later in the day.12 The present study seeks to build upon these efforts by investigating the effect of didactic teaching and an electronic progress note template on note quality, length, and timeliness across 4 academic internal medicine residency programs.

METHODS

Study Design

This prospective quality improvement study took place across 4 academic institutions: University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), University of California San Francisco (UCSF), University of California San Diego (UCSD), and University of Iowa, all of which use Epic EHR (Epic Corp., Madison, WI). The intervention combined brief educational conferences directed at housestaff and attendings with the implementation of an electronic progress note template. Guided by resident input, a note-writing task force at UCSF and UCLA developed a set of best practice guidelines and an aligned note template for progress notes (supplementary Appendix 1). UCSD and the University of Iowa adopted them at their respective institutions. The template’s design minimized autopopulation while encouraging providers to enter relevant data via free text fields (eg, physical exam), prompts (eg, “I have reviewed all the labs from today. Pertinent labs include…”), and drop-down menus (eg, deep vein thrombosis [DVT] prophylaxis: enoxaparin, heparin subcutaneously, etc; supplementary Appendix 2). Additionally, an inpatient checklist was included at the end of the note to serve as a reminder for key inpatient concerns and quality measures, such as Foley catheter days, discharge planning, and code status. Lectures that focused on issues with documentation in the EHR, the best practice guidelines, and a review of the note template with instructions on how to access it were presented to the housestaff. Each institution tailored the lecture to suit their culture. Housestaff were encouraged but not required to use the note template.

Selection and Grading of Progress Notes

Progress notes were eligible for the study if they were written by an intern on an internal medicine teaching service, from a patient with a hospitalization length of at least 3 days with a progress note selected from hospital day 2 or 3, and written while the patient was on the general medicine wards. The preintervention notes were authored from September 2013 to December 2013 and the postintervention notes from April 2014 to June 2014. One note was selected per patient and no more than 3 notes were selected per intern. Each institution selected the first 50 notes chronologically that met these criteria for both the preintervention and the postintervention periods, for a total of 400 notes. The note-grading tool consisted of the following 3 sections to analyze note quality: (1) a general impression of the note (eg, below average, average, above average); (2) the validated Physician Documentation Quality Instrument, 9-item version (PDQI-9) that evaluates notes on 9 domains (up to date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, internally consistent) on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely); and (3) a note competency questionnaire based on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency note checklist that asked yes or no questions about best practice elements (eg, is there a relevant and focused physical exam).12

Graders were internal medicine teaching faculty involved in the study and were assigned to review notes from their respective sites by directly utilizing the EHR. Although this introduces potential for bias, it was felt that many of the grading elements required the grader to know details of the patient that would not be captured if the note was removed from the context of the EHR. Additionally, graders documented note length (number of lines of text), the time signed by the housestaff, and whether the template was used. Three different graders independently evaluated each note and submitted ratings by using Research Electronic Data Capture.13

Statistical Analysis

Means for each item on the grading tool were computed across raters for each progress note. These were summarized by institution as well as by pre- and postintervention. Cumulative logit mixed effects models were used to compare item responses between study conditions. The number of lines per note before and after the note template intervention was compared by using a mixed effects negative binomial regression model. The timestamp on each note, representing the time of day the note was signed, was compared pre- and postintervention by using a linear mixed effects model. All models included random note and rater effects, and fixed institution and intervention period effects, as well as their interaction. Inter-rater reliability of the grading tool was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using the estimated variance components. Data obtained from the PDQI-9 portion were analyzed by individual components as well as by sum score combining each component. The sum score was used to generate odds ratios to assess the likelihood that postintervention notes that used the template compared to those that did not would increase PDQI-9 sum scores. Both cumulative and site-specific data were analyzed. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The mean general impression score significantly improved from 2.0 to 2.3 (on a 1-3 scale in which 2 is average) after the intervention (P < .001). Additionally, note quality significantly improved across each domain of the PDQI-9 (P < .001 for all domains, Table 1). The ICC was 0.245 for the general impression score and 0.143 for the PDQI-9 sum score.

Three of 4 institutions documented the number of lines per note and the time the note was signed by the intern. Mean number of lines per note decreased by 25% (361 lines preintervention, 265 lines postintervention, P < .001). Mean time signed was approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes earlier in the day (3:27

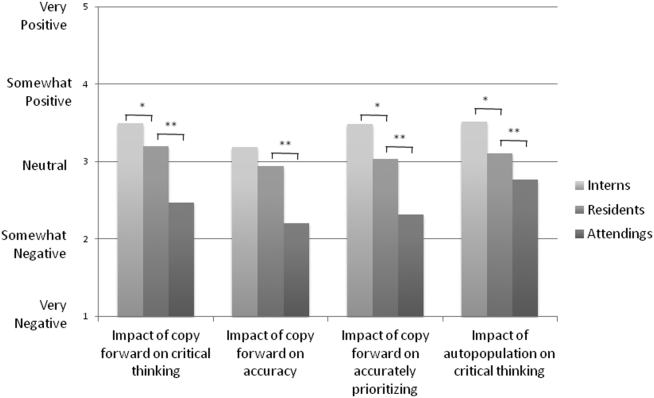

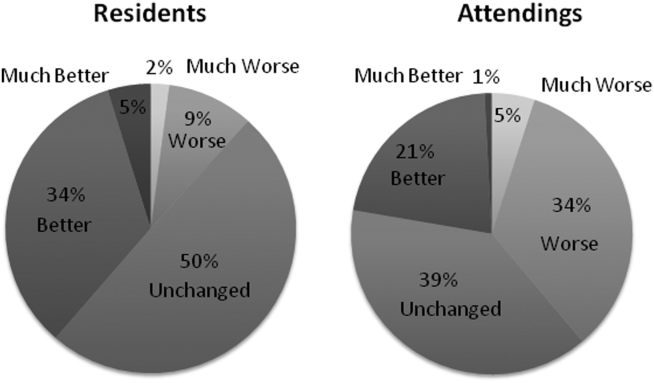

Site-specific data revealed variation between sites. Template use was 92% at UCSF, 90% at UCLA, 79% at Iowa, and 21% at UCSD. The mean general impression score significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and UCSD, but not at Iowa. The PDQI-9 score improved across all domains at UCSF and UCLA, 2 domains at UCSD, and 0 domains at Iowa. Documentation of pertinent labs and studies significantly improved at UCSF, UCLA, and Iowa, but not UCSD. Note length decreased at UCSF and UCLA, but not at UCSD. Notes were signed earlier at UCLA and UCSD, but not at UCSF.

When comparing postintervention notes based on template use, notes that used the template were significantly more likely to receive a higher mean impression score (odds ratio [OR] 11.95, P < .001), higher PDQI-9 sum score (OR 3.05, P < .001), be approximately 25% shorter (326 lines vs 239 lines, P < .001), and be completed approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes earlier (3:07

DISCUSSION

A bundled intervention consisting of educational lectures and a best practice progress note template significantly improved the quality, decreased the length, and resulted in earlier completion of inpatient progress notes. These findings are consistent with a prior study that demonstrated that a bundled note template intervention improved total note score and reduced note clutter.11 We saw a broad improvement in progress notes across all 9 domains of the PDQI-9, which corresponded with an improved general impression score. We also found statistically significant improvements in 7 of the 13 categories of the competency questionnaire.