User login

Acantholytic Anaplastic Extramammary Paget Disease

To the Editor:

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation that is classically known as a mimicker of Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin) due to their histologic similarities.1,2 However, acantholytic anaplastic EMPD (AAEMPD) is a rare variant that can pose a particularly difficult diagnostic challenge because of its histologic similarity to benign acantholytic disorders and other malignant neoplasms. Major histologic features suggestive of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The differential diagnosis of EMPD typically includes Bowen disease and pagetoid Bowen disease, but the acantholytic anaplastic variant more often is confused with intraepidermal acantholytic lesions such as acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies to assist in the definitive diagnosis of AAEMPD are strongly advised because of these difficulties in diagnosis.4 Cases of EMPD with an acantholytic appearance have rarely been reported in the literature.5-7

A 78-year-old man with a history of arthritis, heart disease, hypertension, and gastrointestinal disease presented for evaluation of a tender lesion of the right genitocrural crease of 5 years’ duration. He had no history of cutaneous or internal malignancy. Previously the lesion had been treated by dermatology with a variety of topical products including antifungal and antibiotic creams with no improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, 7×5-cm, tender, erythematous, macerated plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum with an odor possibly due to secondary infection (Figure 1).

plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the specimen was submitted for pathologic examination. Bacterial cultures taken at the time of biopsy revealed polybacterial colonization with Acinetobacter, Morganella, and mixed skin flora. The patient was treated with a 10-day course of oral sulfamethoxazole 800 mg and trimethoprim 160 mg twice daily once culture results returned. The biopsy results were communicated to the patient; however, he subsequently relocated, assumed care at another facility, and has since been lost to follow-up.

The biopsy specimen was examined grossly, serially sectioned, and submitted for routine processing with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Hale colloidal iron staining. Routine IHC was performed with antibodies to cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and low- molecular-weight cytokeratin (LMWCK).

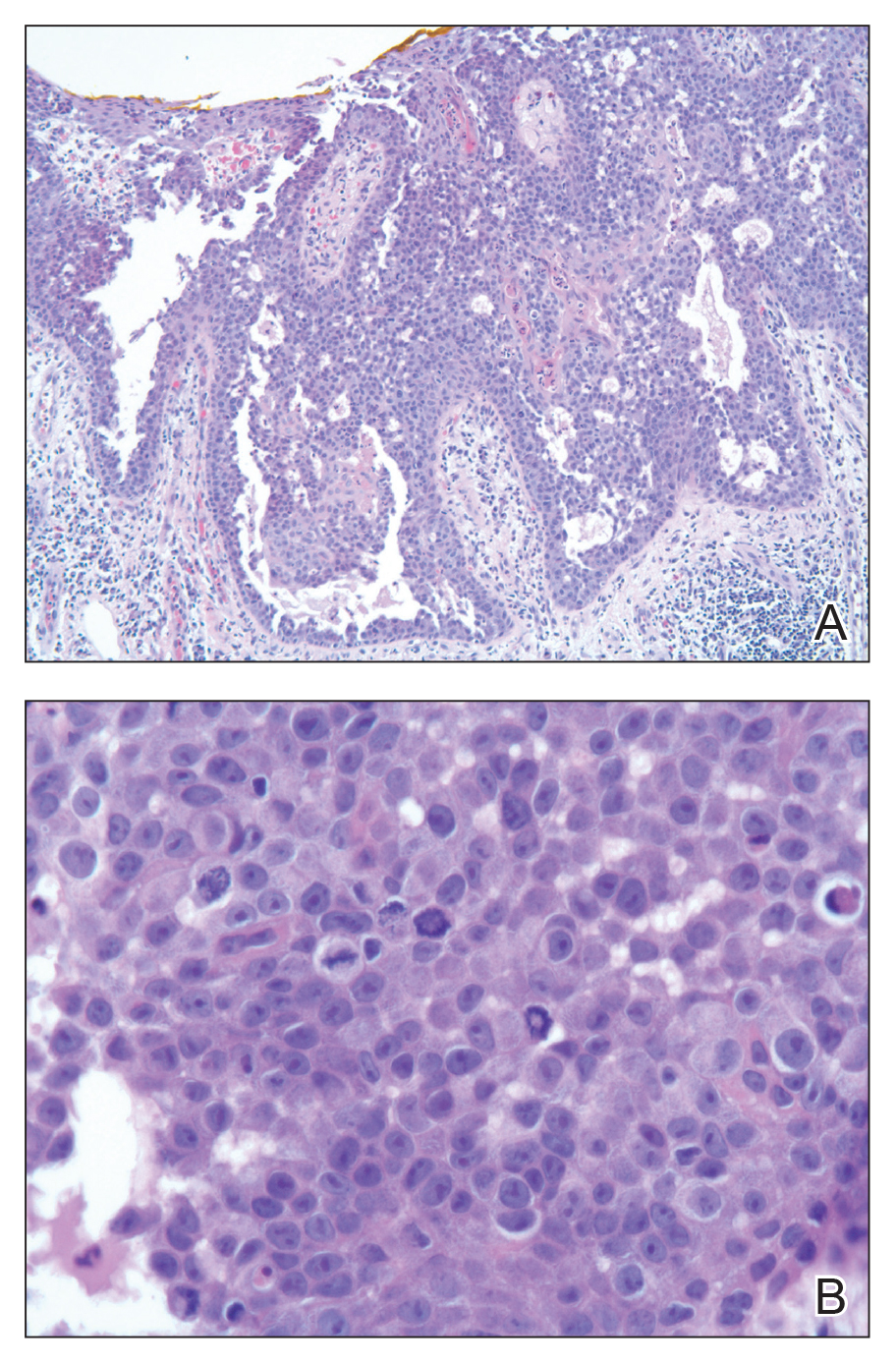

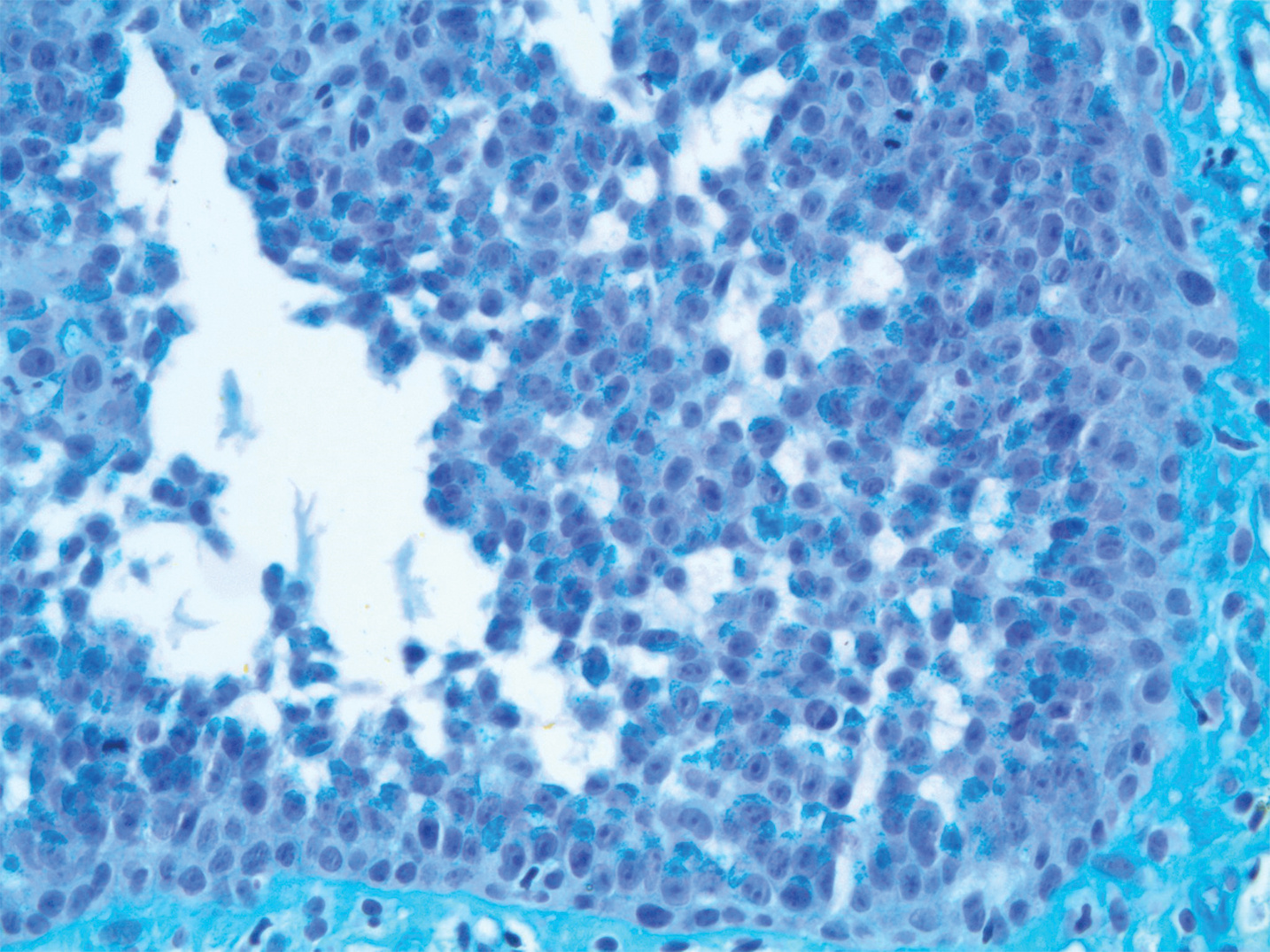

Pathologic examination of the biopsy showed prominent acanthosis of the epidermis composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells with associated full-thickness suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 2A). On inspection at higher magnification, the neoplastic cells demonstrated anaplasia as cytologic atypia with prominent and frequently multiple nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 2B). There was a marked increase in mitotic activity with as many as 5 mitotic figures per high-power field. A fairly dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils was present in the dermis. No fungal elements were observed on periodic acid–Schiff staining. The vast majority of tumor cells demonstrated moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin on Hale colloidal iron staining (Figure 3).

(H&E, original magnification ×400).

Immunohistochemistry staining of tumor cells was positive for CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and LMWCK. The tumor cells were negative for CK20. On the basis of the histopathologic and IHC findings, the patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation. The most commonly involved sites are the anogenital areas including the vulvar, perianal, perineal, scrotal, and penile regions, as well as other areas rich in apocrine glands such as the axillae.8 Extramammary Paget disease most commonly originates as a primary intraepidermal neoplasm (type 1 EMPD), but an underlying malignant neoplasm that spreads intraepithelially is seen in a minority of cases (types 2 and 3 EMPD). In the vulva, type 1a refers to cutaneous noninvasive Paget disease, type 1b refers to dermal invasion of Paget disease, type 1c refers to vulvar adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, type 2 refers to rectal/anal adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, and type 3 refers to urogenital neoplasia–associated Paget disease.9

The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be challenging to diagnose because of its similarities to many other lesions, including acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, Bowen disease, pagetoid Bowen disease, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Major histologic features of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be differentiated from other diagnoses using IHC studies, with findings indicative of AAEMPD outlined below.

The proliferative neoplastic cell in EMPD is the Paget cell, which can be identified as a large round cell located in the epidermis with pale-staining cytoplasm, a large nucleus, and sometimes a prominent nucleolus. Paget cells can be distributed singly or in clusters, nests, or glandular structures within the epidermis and adjacent to adnexal structures.10 Extramammary Paget disease can have many patterns, including glandular, acantholysis-like, upper nest, tall nest, budding, and sheetlike.11

Immunohistochemically, Paget cells in EMPD typically express pancytokeratins (CKAE1/AE3), low-molecular-weight/simple epithelial type keratins (CK7, CAM 5.2), sweat gland antigens (epithelial membrane antigen, CEA, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 [GCDFP15]), mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), and often androgen receptor.12-18 Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin and demonstrate prominent cytoplasmic staining with Hale colloidal iron.17 Paget cells typically do not express high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6), melanocytic antigens, estrogen receptor, or progesterone receptor.15,18

Immunohistochemical staining has been shown to differ between primary cutaneous (type 1) and secondary (types 2 and 3) EMPD. Primary cutaneous EMPD typically expresses sweat gland markers (CK7+, CK20−, GCDFP15+). Secondary EMPD typically expresses an endodermal phenotype (CK7+, CK20+, GCDFP15−).12

Acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area is a rare lesion included in the spectrum of focal acantholytic dyskeratoses described by Ackerman.19 It also has been referred to as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva, though histologically similar lesions also have been reported in men.20-22 Histologically, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area has prominent acantholysis and dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains.19 Familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) is caused by mutations of the ATP2C1 gene, which encodes for a secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase pump type 1 (SPCA1) in the Golgi apparatus in keratinocytes.23 Familial benign pemphigus has a histologic appearance similar to acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, but a positive family history of familial benign pemphigus can be used to differentiate the 2 entities from each other due to the autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern of familial benign pemphigus. Both of these disorders can appear similar to AAEMPD because of their extensive intraepidermal acantholysis, but they differ in the lack of Paget cells, intraepidermal atypia, and increased mitotic activity.

Acantholytic Bowen disease is a histologic variant that can be difficult to distinguish from AAEMPD on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections because of their similar histologic features but can be differentiated by IHC stains.5 Acantholytic Bowen disease expresses high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6) but is negative for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA. Extramammary Paget disease generally has the opposite pattern: positive staining for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA, but negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin.13,14,24

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare malignancy of squamous and glandular differentiation known for being locally aggressive and metastatic.25 Histologically, cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma shows infiltrating nests of neoplastic cells with both squamous and glandular features. It differs notably from AAEMPD in that cutaneous adenosquamous carcinomas tend to arise in the head and arm regions, and their histologic morphology is different. The IHC profiles are similar, with positive staining for CEA, CK7, and mucin; however, they differ in that AAEMPD is negative for high-molecular-weight keratin while cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is positive.25

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma with well-differentiated keratinocytes and a blunt pushing border.24 Similar to AAEMPD, this neoplasm can arise in the genital and perineal areas; however, the 2 entities differ considerably in morphology on histologic examination.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal blistering disorder of the skin and mucous membranes of which pemphigus vegetans is a subtype.26,27 Pemphigus vulgaris is another diagnosis that can possibly be mimicked by AAEMPD.28 Histologic features of pemphigus vulgaris include intraepidermal acantholysis of keratinocytes immediately above the basal layer of the epidermis. Pemphigus vegetans is similar with the addition of papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and an eosinophilic infiltrate.26,27 Immunofluorescence typically demonstrates intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.26 These diseases mimic AAEMPD histologically but differ in their relative lack of atypia and Paget cells.

In summary, we report a case of AAEMPD in a 78-year-old man in whom routine histologic specimens showed marked intraepidermal acantholysis and atypical tumor cells with increased mitoses. The latter finding prompted IHC studies that revealed positive CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin, and LMWCK staining with negative CK20 staining. Hale colloidal iron staining showed moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin. The patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD. It is imperative to maintain clinical suspicion for AAEMPD and to examine acantholytic disorders with scrutiny. When there is evidence of atypia or mitoses, use of IHC stains can assist in fully characterizing the lesion.

- Bowen JT. Precancerous dermatosis: a study of two cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241-255.

- Jones RE Jr, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a critical reexamination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:101-132.

- Rayne SC, Santa Cruz DJ. Anaplastic Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1085-1091.

- Wang EC, Kwah YC, Tan WP, et al. Extramammary Paget disease: immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Du X, Yin X, Zhou N, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:683.

- Mobini N. Acantholytic anaplastic Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:374-380.

- Oh YJ, Lew BL, Sim WY. Acantholytic anaplastic extramammary Paget’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:226-230.

- Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

- Wilkinson EJ, Brown HM. Vulvar Paget disease of urothelial origin: a report of three cases and a proposed classification of vulvar Paget disease. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:549-554.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Shiomi T, Yoshida Y, Shomori K, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease: evaluation of the histopathological patterns of Paget cell proliferation in the epidermis. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1054-1057.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Vulvar Paget’s disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1178-1187.

- Alhumaidi A. Practical immunohistochemistry of epithelial skin tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2012;78:698-708.

- Battles O, Page D, Johnson J. Cytokeratins, CEA and mucin histochemistry in the diagnosis and characterization of extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:6-12.

- Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581-590.

- Krishna M. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: an immunohistochemical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:207-215.

- Helm KF, Goellner JR, Peters MS. Immunohistochemical stain in extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:402-407.

- Liegl B, Horn L, Moinfar F. Androgen receptors are frequently expressed in mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1283-288.

- Ackerman AB. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Arch Derm. 1972;106:702-706.

- Dittmer CJ, Hornemann A, Rose C, et al. Successful laser therapy of a papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva: case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;291:723-725.

- Roh MR, Choi YJ, Lee KG. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva. J Dermatol. 2009;36:427-429.

- Wong KT, Mihm MC Jr. Acantholytic dermatosis localized to genitalia and crural areas of male patients: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:27-32.

- Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000; 24:61-65.

- Elston DM. Malignant tumors of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Requisites in Dermatology: Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012:53-68.

- Fu JM, McCalmont T, Yu SS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

- Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetans. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:429-452.

- Rados J. Autoimmune blistering diseases: histologic meaning. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:377-388.

- Kohler S, Smoller BR. A case of extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking pemphigus vulgaris on histologic examination. Dermatology. 1997;195:54-56.

To the Editor:

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation that is classically known as a mimicker of Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin) due to their histologic similarities.1,2 However, acantholytic anaplastic EMPD (AAEMPD) is a rare variant that can pose a particularly difficult diagnostic challenge because of its histologic similarity to benign acantholytic disorders and other malignant neoplasms. Major histologic features suggestive of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The differential diagnosis of EMPD typically includes Bowen disease and pagetoid Bowen disease, but the acantholytic anaplastic variant more often is confused with intraepidermal acantholytic lesions such as acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies to assist in the definitive diagnosis of AAEMPD are strongly advised because of these difficulties in diagnosis.4 Cases of EMPD with an acantholytic appearance have rarely been reported in the literature.5-7

A 78-year-old man with a history of arthritis, heart disease, hypertension, and gastrointestinal disease presented for evaluation of a tender lesion of the right genitocrural crease of 5 years’ duration. He had no history of cutaneous or internal malignancy. Previously the lesion had been treated by dermatology with a variety of topical products including antifungal and antibiotic creams with no improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, 7×5-cm, tender, erythematous, macerated plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum with an odor possibly due to secondary infection (Figure 1).

plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the specimen was submitted for pathologic examination. Bacterial cultures taken at the time of biopsy revealed polybacterial colonization with Acinetobacter, Morganella, and mixed skin flora. The patient was treated with a 10-day course of oral sulfamethoxazole 800 mg and trimethoprim 160 mg twice daily once culture results returned. The biopsy results were communicated to the patient; however, he subsequently relocated, assumed care at another facility, and has since been lost to follow-up.

The biopsy specimen was examined grossly, serially sectioned, and submitted for routine processing with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Hale colloidal iron staining. Routine IHC was performed with antibodies to cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and low- molecular-weight cytokeratin (LMWCK).

Pathologic examination of the biopsy showed prominent acanthosis of the epidermis composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells with associated full-thickness suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 2A). On inspection at higher magnification, the neoplastic cells demonstrated anaplasia as cytologic atypia with prominent and frequently multiple nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 2B). There was a marked increase in mitotic activity with as many as 5 mitotic figures per high-power field. A fairly dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils was present in the dermis. No fungal elements were observed on periodic acid–Schiff staining. The vast majority of tumor cells demonstrated moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin on Hale colloidal iron staining (Figure 3).

(H&E, original magnification ×400).

Immunohistochemistry staining of tumor cells was positive for CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and LMWCK. The tumor cells were negative for CK20. On the basis of the histopathologic and IHC findings, the patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation. The most commonly involved sites are the anogenital areas including the vulvar, perianal, perineal, scrotal, and penile regions, as well as other areas rich in apocrine glands such as the axillae.8 Extramammary Paget disease most commonly originates as a primary intraepidermal neoplasm (type 1 EMPD), but an underlying malignant neoplasm that spreads intraepithelially is seen in a minority of cases (types 2 and 3 EMPD). In the vulva, type 1a refers to cutaneous noninvasive Paget disease, type 1b refers to dermal invasion of Paget disease, type 1c refers to vulvar adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, type 2 refers to rectal/anal adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, and type 3 refers to urogenital neoplasia–associated Paget disease.9

The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be challenging to diagnose because of its similarities to many other lesions, including acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, Bowen disease, pagetoid Bowen disease, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Major histologic features of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be differentiated from other diagnoses using IHC studies, with findings indicative of AAEMPD outlined below.

The proliferative neoplastic cell in EMPD is the Paget cell, which can be identified as a large round cell located in the epidermis with pale-staining cytoplasm, a large nucleus, and sometimes a prominent nucleolus. Paget cells can be distributed singly or in clusters, nests, or glandular structures within the epidermis and adjacent to adnexal structures.10 Extramammary Paget disease can have many patterns, including glandular, acantholysis-like, upper nest, tall nest, budding, and sheetlike.11

Immunohistochemically, Paget cells in EMPD typically express pancytokeratins (CKAE1/AE3), low-molecular-weight/simple epithelial type keratins (CK7, CAM 5.2), sweat gland antigens (epithelial membrane antigen, CEA, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 [GCDFP15]), mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), and often androgen receptor.12-18 Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin and demonstrate prominent cytoplasmic staining with Hale colloidal iron.17 Paget cells typically do not express high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6), melanocytic antigens, estrogen receptor, or progesterone receptor.15,18

Immunohistochemical staining has been shown to differ between primary cutaneous (type 1) and secondary (types 2 and 3) EMPD. Primary cutaneous EMPD typically expresses sweat gland markers (CK7+, CK20−, GCDFP15+). Secondary EMPD typically expresses an endodermal phenotype (CK7+, CK20+, GCDFP15−).12

Acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area is a rare lesion included in the spectrum of focal acantholytic dyskeratoses described by Ackerman.19 It also has been referred to as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva, though histologically similar lesions also have been reported in men.20-22 Histologically, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area has prominent acantholysis and dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains.19 Familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) is caused by mutations of the ATP2C1 gene, which encodes for a secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase pump type 1 (SPCA1) in the Golgi apparatus in keratinocytes.23 Familial benign pemphigus has a histologic appearance similar to acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, but a positive family history of familial benign pemphigus can be used to differentiate the 2 entities from each other due to the autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern of familial benign pemphigus. Both of these disorders can appear similar to AAEMPD because of their extensive intraepidermal acantholysis, but they differ in the lack of Paget cells, intraepidermal atypia, and increased mitotic activity.

Acantholytic Bowen disease is a histologic variant that can be difficult to distinguish from AAEMPD on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections because of their similar histologic features but can be differentiated by IHC stains.5 Acantholytic Bowen disease expresses high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6) but is negative for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA. Extramammary Paget disease generally has the opposite pattern: positive staining for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA, but negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin.13,14,24

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare malignancy of squamous and glandular differentiation known for being locally aggressive and metastatic.25 Histologically, cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma shows infiltrating nests of neoplastic cells with both squamous and glandular features. It differs notably from AAEMPD in that cutaneous adenosquamous carcinomas tend to arise in the head and arm regions, and their histologic morphology is different. The IHC profiles are similar, with positive staining for CEA, CK7, and mucin; however, they differ in that AAEMPD is negative for high-molecular-weight keratin while cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is positive.25

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma with well-differentiated keratinocytes and a blunt pushing border.24 Similar to AAEMPD, this neoplasm can arise in the genital and perineal areas; however, the 2 entities differ considerably in morphology on histologic examination.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal blistering disorder of the skin and mucous membranes of which pemphigus vegetans is a subtype.26,27 Pemphigus vulgaris is another diagnosis that can possibly be mimicked by AAEMPD.28 Histologic features of pemphigus vulgaris include intraepidermal acantholysis of keratinocytes immediately above the basal layer of the epidermis. Pemphigus vegetans is similar with the addition of papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and an eosinophilic infiltrate.26,27 Immunofluorescence typically demonstrates intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.26 These diseases mimic AAEMPD histologically but differ in their relative lack of atypia and Paget cells.

In summary, we report a case of AAEMPD in a 78-year-old man in whom routine histologic specimens showed marked intraepidermal acantholysis and atypical tumor cells with increased mitoses. The latter finding prompted IHC studies that revealed positive CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin, and LMWCK staining with negative CK20 staining. Hale colloidal iron staining showed moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin. The patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD. It is imperative to maintain clinical suspicion for AAEMPD and to examine acantholytic disorders with scrutiny. When there is evidence of atypia or mitoses, use of IHC stains can assist in fully characterizing the lesion.

To the Editor:

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation that is classically known as a mimicker of Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin) due to their histologic similarities.1,2 However, acantholytic anaplastic EMPD (AAEMPD) is a rare variant that can pose a particularly difficult diagnostic challenge because of its histologic similarity to benign acantholytic disorders and other malignant neoplasms. Major histologic features suggestive of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The differential diagnosis of EMPD typically includes Bowen disease and pagetoid Bowen disease, but the acantholytic anaplastic variant more often is confused with intraepidermal acantholytic lesions such as acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies to assist in the definitive diagnosis of AAEMPD are strongly advised because of these difficulties in diagnosis.4 Cases of EMPD with an acantholytic appearance have rarely been reported in the literature.5-7

A 78-year-old man with a history of arthritis, heart disease, hypertension, and gastrointestinal disease presented for evaluation of a tender lesion of the right genitocrural crease of 5 years’ duration. He had no history of cutaneous or internal malignancy. Previously the lesion had been treated by dermatology with a variety of topical products including antifungal and antibiotic creams with no improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, 7×5-cm, tender, erythematous, macerated plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum with an odor possibly due to secondary infection (Figure 1).

plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the specimen was submitted for pathologic examination. Bacterial cultures taken at the time of biopsy revealed polybacterial colonization with Acinetobacter, Morganella, and mixed skin flora. The patient was treated with a 10-day course of oral sulfamethoxazole 800 mg and trimethoprim 160 mg twice daily once culture results returned. The biopsy results were communicated to the patient; however, he subsequently relocated, assumed care at another facility, and has since been lost to follow-up.

The biopsy specimen was examined grossly, serially sectioned, and submitted for routine processing with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Hale colloidal iron staining. Routine IHC was performed with antibodies to cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and low- molecular-weight cytokeratin (LMWCK).

Pathologic examination of the biopsy showed prominent acanthosis of the epidermis composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells with associated full-thickness suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 2A). On inspection at higher magnification, the neoplastic cells demonstrated anaplasia as cytologic atypia with prominent and frequently multiple nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 2B). There was a marked increase in mitotic activity with as many as 5 mitotic figures per high-power field. A fairly dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils was present in the dermis. No fungal elements were observed on periodic acid–Schiff staining. The vast majority of tumor cells demonstrated moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin on Hale colloidal iron staining (Figure 3).

(H&E, original magnification ×400).

Immunohistochemistry staining of tumor cells was positive for CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and LMWCK. The tumor cells were negative for CK20. On the basis of the histopathologic and IHC findings, the patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation. The most commonly involved sites are the anogenital areas including the vulvar, perianal, perineal, scrotal, and penile regions, as well as other areas rich in apocrine glands such as the axillae.8 Extramammary Paget disease most commonly originates as a primary intraepidermal neoplasm (type 1 EMPD), but an underlying malignant neoplasm that spreads intraepithelially is seen in a minority of cases (types 2 and 3 EMPD). In the vulva, type 1a refers to cutaneous noninvasive Paget disease, type 1b refers to dermal invasion of Paget disease, type 1c refers to vulvar adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, type 2 refers to rectal/anal adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, and type 3 refers to urogenital neoplasia–associated Paget disease.9

The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be challenging to diagnose because of its similarities to many other lesions, including acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, Bowen disease, pagetoid Bowen disease, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Major histologic features of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be differentiated from other diagnoses using IHC studies, with findings indicative of AAEMPD outlined below.

The proliferative neoplastic cell in EMPD is the Paget cell, which can be identified as a large round cell located in the epidermis with pale-staining cytoplasm, a large nucleus, and sometimes a prominent nucleolus. Paget cells can be distributed singly or in clusters, nests, or glandular structures within the epidermis and adjacent to adnexal structures.10 Extramammary Paget disease can have many patterns, including glandular, acantholysis-like, upper nest, tall nest, budding, and sheetlike.11

Immunohistochemically, Paget cells in EMPD typically express pancytokeratins (CKAE1/AE3), low-molecular-weight/simple epithelial type keratins (CK7, CAM 5.2), sweat gland antigens (epithelial membrane antigen, CEA, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 [GCDFP15]), mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), and often androgen receptor.12-18 Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin and demonstrate prominent cytoplasmic staining with Hale colloidal iron.17 Paget cells typically do not express high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6), melanocytic antigens, estrogen receptor, or progesterone receptor.15,18

Immunohistochemical staining has been shown to differ between primary cutaneous (type 1) and secondary (types 2 and 3) EMPD. Primary cutaneous EMPD typically expresses sweat gland markers (CK7+, CK20−, GCDFP15+). Secondary EMPD typically expresses an endodermal phenotype (CK7+, CK20+, GCDFP15−).12

Acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area is a rare lesion included in the spectrum of focal acantholytic dyskeratoses described by Ackerman.19 It also has been referred to as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva, though histologically similar lesions also have been reported in men.20-22 Histologically, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area has prominent acantholysis and dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains.19 Familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) is caused by mutations of the ATP2C1 gene, which encodes for a secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase pump type 1 (SPCA1) in the Golgi apparatus in keratinocytes.23 Familial benign pemphigus has a histologic appearance similar to acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, but a positive family history of familial benign pemphigus can be used to differentiate the 2 entities from each other due to the autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern of familial benign pemphigus. Both of these disorders can appear similar to AAEMPD because of their extensive intraepidermal acantholysis, but they differ in the lack of Paget cells, intraepidermal atypia, and increased mitotic activity.

Acantholytic Bowen disease is a histologic variant that can be difficult to distinguish from AAEMPD on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections because of their similar histologic features but can be differentiated by IHC stains.5 Acantholytic Bowen disease expresses high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6) but is negative for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA. Extramammary Paget disease generally has the opposite pattern: positive staining for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA, but negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin.13,14,24

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare malignancy of squamous and glandular differentiation known for being locally aggressive and metastatic.25 Histologically, cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma shows infiltrating nests of neoplastic cells with both squamous and glandular features. It differs notably from AAEMPD in that cutaneous adenosquamous carcinomas tend to arise in the head and arm regions, and their histologic morphology is different. The IHC profiles are similar, with positive staining for CEA, CK7, and mucin; however, they differ in that AAEMPD is negative for high-molecular-weight keratin while cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is positive.25

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma with well-differentiated keratinocytes and a blunt pushing border.24 Similar to AAEMPD, this neoplasm can arise in the genital and perineal areas; however, the 2 entities differ considerably in morphology on histologic examination.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal blistering disorder of the skin and mucous membranes of which pemphigus vegetans is a subtype.26,27 Pemphigus vulgaris is another diagnosis that can possibly be mimicked by AAEMPD.28 Histologic features of pemphigus vulgaris include intraepidermal acantholysis of keratinocytes immediately above the basal layer of the epidermis. Pemphigus vegetans is similar with the addition of papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and an eosinophilic infiltrate.26,27 Immunofluorescence typically demonstrates intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.26 These diseases mimic AAEMPD histologically but differ in their relative lack of atypia and Paget cells.

In summary, we report a case of AAEMPD in a 78-year-old man in whom routine histologic specimens showed marked intraepidermal acantholysis and atypical tumor cells with increased mitoses. The latter finding prompted IHC studies that revealed positive CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin, and LMWCK staining with negative CK20 staining. Hale colloidal iron staining showed moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin. The patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD. It is imperative to maintain clinical suspicion for AAEMPD and to examine acantholytic disorders with scrutiny. When there is evidence of atypia or mitoses, use of IHC stains can assist in fully characterizing the lesion.

- Bowen JT. Precancerous dermatosis: a study of two cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241-255.

- Jones RE Jr, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a critical reexamination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:101-132.

- Rayne SC, Santa Cruz DJ. Anaplastic Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1085-1091.

- Wang EC, Kwah YC, Tan WP, et al. Extramammary Paget disease: immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Du X, Yin X, Zhou N, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:683.

- Mobini N. Acantholytic anaplastic Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:374-380.

- Oh YJ, Lew BL, Sim WY. Acantholytic anaplastic extramammary Paget’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:226-230.

- Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

- Wilkinson EJ, Brown HM. Vulvar Paget disease of urothelial origin: a report of three cases and a proposed classification of vulvar Paget disease. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:549-554.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Shiomi T, Yoshida Y, Shomori K, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease: evaluation of the histopathological patterns of Paget cell proliferation in the epidermis. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1054-1057.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Vulvar Paget’s disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1178-1187.

- Alhumaidi A. Practical immunohistochemistry of epithelial skin tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2012;78:698-708.

- Battles O, Page D, Johnson J. Cytokeratins, CEA and mucin histochemistry in the diagnosis and characterization of extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:6-12.

- Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581-590.

- Krishna M. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: an immunohistochemical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:207-215.

- Helm KF, Goellner JR, Peters MS. Immunohistochemical stain in extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:402-407.

- Liegl B, Horn L, Moinfar F. Androgen receptors are frequently expressed in mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1283-288.

- Ackerman AB. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Arch Derm. 1972;106:702-706.

- Dittmer CJ, Hornemann A, Rose C, et al. Successful laser therapy of a papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva: case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;291:723-725.

- Roh MR, Choi YJ, Lee KG. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva. J Dermatol. 2009;36:427-429.

- Wong KT, Mihm MC Jr. Acantholytic dermatosis localized to genitalia and crural areas of male patients: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:27-32.

- Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000; 24:61-65.

- Elston DM. Malignant tumors of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Requisites in Dermatology: Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012:53-68.

- Fu JM, McCalmont T, Yu SS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

- Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetans. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:429-452.

- Rados J. Autoimmune blistering diseases: histologic meaning. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:377-388.

- Kohler S, Smoller BR. A case of extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking pemphigus vulgaris on histologic examination. Dermatology. 1997;195:54-56.

- Bowen JT. Precancerous dermatosis: a study of two cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241-255.

- Jones RE Jr, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a critical reexamination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:101-132.

- Rayne SC, Santa Cruz DJ. Anaplastic Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1085-1091.

- Wang EC, Kwah YC, Tan WP, et al. Extramammary Paget disease: immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Du X, Yin X, Zhou N, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:683.

- Mobini N. Acantholytic anaplastic Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:374-380.

- Oh YJ, Lew BL, Sim WY. Acantholytic anaplastic extramammary Paget’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:226-230.

- Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

- Wilkinson EJ, Brown HM. Vulvar Paget disease of urothelial origin: a report of three cases and a proposed classification of vulvar Paget disease. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:549-554.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Shiomi T, Yoshida Y, Shomori K, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease: evaluation of the histopathological patterns of Paget cell proliferation in the epidermis. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1054-1057.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Vulvar Paget’s disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1178-1187.

- Alhumaidi A. Practical immunohistochemistry of epithelial skin tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2012;78:698-708.

- Battles O, Page D, Johnson J. Cytokeratins, CEA and mucin histochemistry in the diagnosis and characterization of extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:6-12.

- Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581-590.

- Krishna M. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: an immunohistochemical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:207-215.

- Helm KF, Goellner JR, Peters MS. Immunohistochemical stain in extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:402-407.

- Liegl B, Horn L, Moinfar F. Androgen receptors are frequently expressed in mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1283-288.

- Ackerman AB. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Arch Derm. 1972;106:702-706.

- Dittmer CJ, Hornemann A, Rose C, et al. Successful laser therapy of a papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva: case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;291:723-725.

- Roh MR, Choi YJ, Lee KG. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva. J Dermatol. 2009;36:427-429.

- Wong KT, Mihm MC Jr. Acantholytic dermatosis localized to genitalia and crural areas of male patients: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:27-32.

- Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000; 24:61-65.

- Elston DM. Malignant tumors of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Requisites in Dermatology: Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012:53-68.

- Fu JM, McCalmont T, Yu SS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

- Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetans. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:429-452.

- Rados J. Autoimmune blistering diseases: histologic meaning. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:377-388.

- Kohler S, Smoller BR. A case of extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking pemphigus vulgaris on histologic examination. Dermatology. 1997;195:54-56.

Practice Points

- The acantholytic anaplastic variant of extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) can be mimicked by many other entities including Bowen disease, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, and pemphigus vulgaris.

- A good immunohistochemical panel to evaluate for EMPD includes cytokeratin (CK) 7, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), CK20, and carcinoembryonic antigen.