User login

Inappropriate Treatment of HCA‐cSSTI

Classically, infections have been categorized as either community‐acquired (CAI) or nosocomial in origin. Until recently, this scheme was thought adequate to capture the differences in the microbiology and outcomes in the corresponding scenarios. However, recent evidence suggests that this distinction may no longer be valid. For example, with the spread and diffusion of healthcare delivery beyond the confines of the hospital along with the increasing use of broad spectrum antibiotics both in and out of the hospital, pathogens such as methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA), traditionally thought to be confined to the hospital, are now seen in patients presenting from the community to the emergency department (ED).1, 2 Reflecting this shift in epidemiology, some national guidelines now recognize healthcare‐associated infection (HCAI) as a distinct entity.3 The concept of HCAI allows the clinician to identify patients who, despite suffering a community onset infection, still may be at risk for a resistant bacterial pathogen. Recent studies in both bloodstream infection and pneumonia have clearly demonstrated that those with HCAI have distinct microbiology and outcomes relative to those with pure CAI.47

Most work focusing on establishing HCAI has not addressed skin and soft tissue infections. These infections, although not often fatal, account for an increasing number of admissions to the hospital.8, 9 In addition, they may be associated with substantial morbidity and cost.8 Given that many pathogens such as S. aureus, which may be resistant to typical antimicrobials used in the ED, are also major culprits in complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI), the HCAI paradigm may apply in cSSSI. Furthermore, because of these patterns of increased resistance, HCA‐cSSSI patients, similar to other HCAI groups, may be at an increased risk of being treated with initially inappropriate antibiotic therapy.7, 10

Since in the setting of other types of infection inappropriate empiric treatment has been shown to be associated with increased mortality and costs,7, 1015 and since indirect evidence suggests a similar impact on healthcare utilization among cSSSI patients,8 we hypothesized that among a cohort of patients hospitalized with a cSSSI, the initial empiric choice of therapy is independently associated with hospital length of stay (LOS). We performed a retrospective cohort study to address this question.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a single‐center retrospective cohort study of patients with cSSSI admitted to the hospital through the ED. All consecutive patients hospitalized between April 2006 and December 2007 meeting predefined inclusion criteria (see below) were enrolled. The study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee, and informed consent was waived. We have previously reported on the characteristics and outcomes of this cohort, including both community‐acquired and HCA‐cSSSI patients.16

Study Cohort

All consecutive patients admitted from the community through the ED between April 2006 and December 2007 at the Barnes‐Jewish Hospital, a 1200‐bed university‐affiliated, urban teaching hospital in St. Louis, MO were included if: (1) they had a diagnosis of a predefined cSSSI (see Appendix Table A1, based on reference 8) and (2) they had a positive microbiology culture obtained within 24 hours of hospital admission. Similar to the work by Edelsberg et al.8 we excluded patients if certain diagnoses and procedures were present (Appendix Table A2). Cases were also excluded if they represented a readmission for the same diagnosis within 30 days of the original hospitalization.

Definitions

HCAI was defined as any cSSSI in a patient with a history of recent hospitalization (within the previous year, consistent with the previous study16), receiving antibiotics prior to admission (previous 90 days), transferring from a nursing home, or needing chronic dialysis. We defined a polymicrobial infection as one with more than one organism, and mixed infection as an infection with both a gram‐positive and a gram‐negative organism. Inappropriate empiric therapy took place if a patient did not receive treatment within 24 hours of the time the culture was obtained with an agent exhibiting in vitro activity against the isolated pathogen(s). In mixed infections, appropriate therapy was treatment within 24 hours of culture being obtained with agent(s) active against all pathogens recovered.

Data Elements

We collected information about multiple baseline demographic and clinical factors including: age, gender, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, the presence of risk factors for HCAI, the presence of bacteremia at admission, and the location of admission (ward vs. intensive care unit [ICU]). Bacteriology data included information on specific bacterium/a recovered from culture, the site of the culture (eg, tissue, blood), susceptibility patterns, and whether the infection was monomicrobial, polymicrobial, or mixed. When blood culture was available and positive, we prioritized this over wound and other cultures and designated the corresponding organism as the culprit in the index infection. Cultures growing our coagulase‐negative S. aureus were excluded as a probable contaminant. Treatment data included information on the choice of the antimicrobial therapy and the timing of its institution relative to the timing of obtaining the culture specimen. The presence of such procedures as incision and drainage (I&D) or debridement was recorded.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics comparing HCAI patients treated appropriately to those receiving inappropriate empiric coverage based on their clinical, demographic, microbiologic and treatment characteristics were computed. Hospital LOS served as the primary and hospital mortality as the secondary outcomes, comparing patients with HCAI treated appropriately to those treated inappropriately. All continuous variables were compared using Student's t test or the Mann‐Whitney U test as appropriate. All categorical variables were compared using the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. To assess the attributable impact of inappropriate therapy in HCAI on the outcomes of interest, general linear models with log transformation were developed to model hospital LOS parameters; all means are presented as geometric means. All potential risk factors significant at the 0.1 level in univariate analyses were entered into the model. All calculations were performed in Stata version 9 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 717 patients with culture‐positive cSSSI admitted during the study period, 527 (73.5%) were classified as HCAI. The most common reason for classification as an HCAI was recent hospitalization. Among those with an HCA‐cSSSI, 405 (76.9%) received appropriate empiric treatment, with nearly one‐quarter receiving inappropriate initial coverage. Those receiving inappropriate antibiotic were more likely to be African American, and had a higher likelihood of having end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) than those with appropriate coverage (Table 1). While those patients treated appropriately had higher rates of both cellulitis and abscess as the presenting infection, a substantially higher proportion of those receiving inappropriate initial treatment had a decubitus ulcer (29.5% vs. 10.9%, P <0.001), a device‐associated infection (42.6% vs. 28.6%, P = 0.004), and had evidence of bacteremia (68.9% vs. 57.8%, P = 0.028) than those receiving appropriate empiric coverage (Table 2).

| Inappropriate (n = 122), n (%) | Appropriate (n = 405), n (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, years | 56.3 18.0 | 53.6 16.7 | 0.147 |

| Gender (F) | 62 (50.8) | 190 (46.9) | 0.449 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 51 (41.8) | 219 (54.1) | 0.048 |

| African American | 68 (55.7) | 178 (43.9) | |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 8 (2.0) | |

| HCAI risk factors | |||

| Recent hospitalization* | 110 (90.2) | 373 (92.1) | 0.498 |

| Within 90 days | 98 (80.3) | 274 (67.7) | 0.007 |

| >90 and 180 days | 52 (42.6) | 170 (42.0) | 0.899 |

| >180 days and 1 year | 46 (37.7) | 164 (40.5) | 0.581 |

| Prior antibiotics | 26 (21.3) | 90 (22.2) | 0.831 |

| Nursing home resident | 29 (23.8) | 54 (13.3) | 0.006 |

| Hemodialysis | 19 (15.6) | 39 (9.7) | 0.067 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| DM | 40 (37.8) | 128 (31.6) | 0.806 |

| PVD | 5 (4.1) | 15 (3.7) | 0.841 |

| Liver disease | 6 (4.9) | 33 (8.2) | 0.232 |

| Cancer | 21 (17.2) | 85 (21.0) | 0.362 |

| HIV | 1 (0.8) | 12 (3.0) | 0.316 |

| Organ transplant | 2 (1.6) | 8 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Autoimmune disease | 5 (4.1) | 8 (2.0) | 0.185 |

| ESRD | 22 (18.0) | 46 (11.4) | 0.054 |

| Inappropriate (n = 122), n (%) | Appropriate (n = 405), n (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Cellulitis | 28 (23.0) | 171 (42.2) | <0.001 |

| Decubitus ulcer | 36 (29.5) | 44 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Post‐op wound | 25 (20.5) | 75 (18.5) | 0.626 |

| Device‐associated infection | 52 (42.6) | 116 (28.6) | 0.004 |

| Diabetic foot ulcer | 9 (7.4) | 24 (5.9) | 0.562 |

| Abscess | 22 (18.0) | 108 (26.7) | 0.052 |

| Other* | 2 (1.6) | 17 (4.2) | 0.269 |

| Presence of bacteremia | 84 (68.9) | 234 (57.8) | 0.028 |

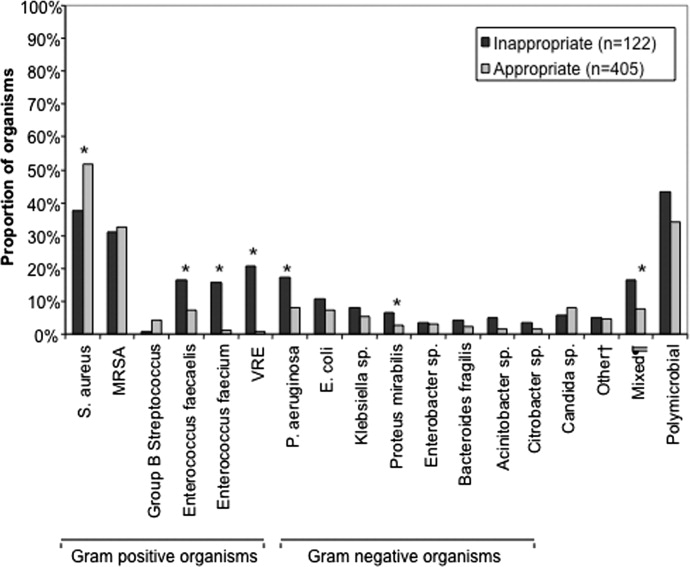

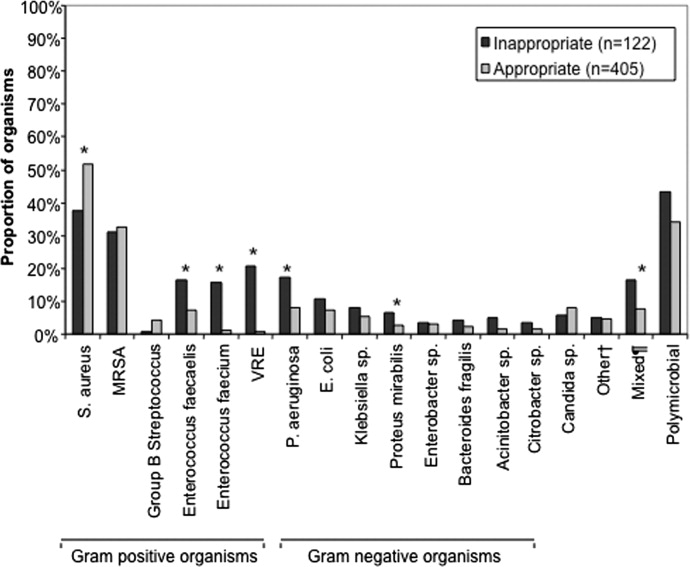

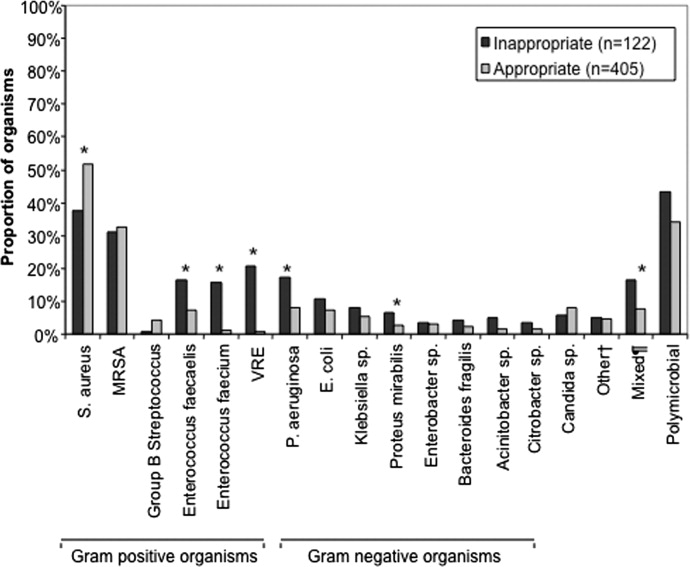

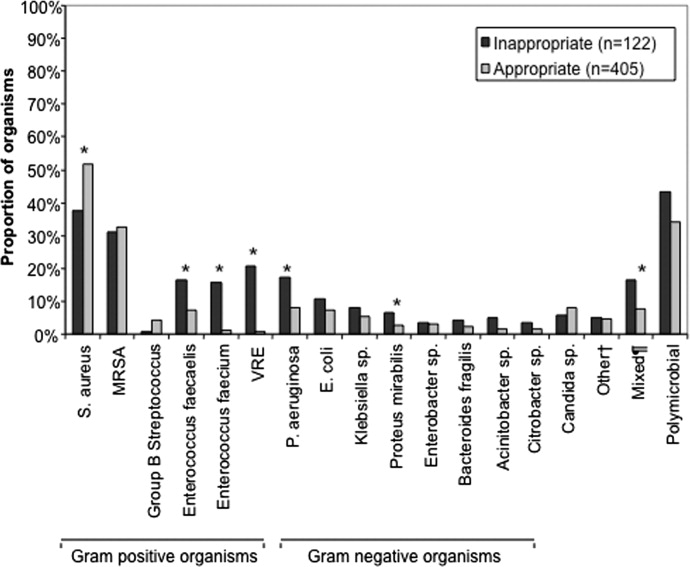

The pathogens recovered from the appropriately and inappropriately treated groups are listed in Figure 1. While S. aureus overall was more common among those treated appropriately, the frequency of MRSA did not differ between the groups. Both E. faecalis and E. faecium were recovered more frequently in the inappropriate group, resulting in a similar pattern among the vancomycin‐resistant enterococcal species. Likewise, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, and A. baumannii were all more frequently seen in the group treated inappropriately than in the group getting appropriate empiric coverage. A mixed infection was also more likely to be present among those not exposed (16.5%) than among those exposed (7.5%) to appropriate early therapy (P = 0.001) (Figure 1).

In terms of processes of care and outcomes (Table 3), commensurate with the higher prevalence of abscess in the appropriately treated group, the rate of I&D was significantly higher in this cohort (36.8%) than in the inappropriately treated (23.0%) group (P = 0.005). Need for initial ICU care did not differ as a function of appropriateness of therapy (P = 0.635).

| Inappropriate (n = 122) | Appropriate (n = 405) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| I&D/debridement | 28 (23.0%) | 149 (36.8%) | 0.005 |

| I&D in ED | 0 | 7 (1.7) | 0.361 |

| ICU | 9 (7.4%) | 25 (6.2%) | 0.635 |

| Hospital LOS, days | |||

| Median (IQR 25, 75) [Range] | 7.0 (4.2, 13.6) [0.686.6] | 6 (3.3, 10.1) [0.748.3] | 0.026 |

| Hospital mortality | 9 (7.4%) | 26 (6.4%) | 0.710 |

The unadjusted mortality rate was low overall and did not vary based on initial treatment (Table 3). In a generalized linear model with the log‐transformed LOS as the dependent variable, adjusting for multiple potential confounders, initial inappropriate antibiotic therapy had an attributable incremental increase in the hospital LOS of 1.8 days (95% CI, 1.42.3) (Table 4).

| Factor | Attributable LOS (days) | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Infection type: device | 3.6 | 2.74.8 | <0.001 |

| Infection type: decubitus ulcer | 3.3 | 2.64.2 | <0.001 |

| Infection type: abscess | 2.5 | 1.64.0 | <0.001 |

| Organism: P. mirabilis | 2.2 | 1.43.4 | <0.001 |

| Organism: E. faecalis | 2.1 | 1.72.6 | <0.001 |

| Nursing home resident | 2.1 | 1.62.6 | <0.001 |

| Inappropriate antibiotic | 1.8 | 1.42.3 | <0.001 |

| Race: Non‐Caucasian | 0.31 | 0.240.41 | <0.001 |

| Organism: E. faecium | 0.23 | 0.150.35 | <0.001 |

Because bacteremia is known to be an effect modifier of the relationship between the empiric choice of antibiotic and infection outcomes, we further explored its role in the HCAI cSSSI on the outcomes of interest (Table 5). Similar to the effect detected in the overall cohort, treatment with inappropriate therapy was associated with an increase in the hospital LOS, but not hospital mortality in those with bacteremia, though this phenomenon was observed only among patients with secondary bacteremia, and not among those without (Table 5).

| Bacteremia Present (n = 318) | Bacteremia Absent (n = 209) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (n = 84) | A (n = 234) | P Value | I (n = 38) | A (n = 171) | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Hospital LOS, days | ||||||

| Mean SD | 14.4 27.5 | 9.8 9.7 | 0.041 | 6.6 6.8 | 6.9 8.2 | 0.761 |

| Median (IQR 25, 75) | 8.8 (5.4, 13.9) | 7.0 (4.3, 11.7) | 4.4 (2.4, 7.7) | 3.9 (2.0, 8.2) | ||

| Hospital mortality | 8 (9.5%) | 24 (10.3%) | 0.848 | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.454 |

Discussion

This retrospective analysis provides evidence that inappropriate empiric antibiotic therapy for HCA‐cSSSI independently prolongs hospital LOS. The impact of inappropriate initial treatment on LOS is independent of many important confounders. In addition, we observed that this effect, while present among patients with secondary bacteremia, is absent among those without a blood stream infection.

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first cohort study to examine the outcomes associated with inappropriate treatment of a HCAI cSSSI within the context of available microbiology data. Edelsberg et al.8 examined clinical and economic outcomes associated with the failure of the initial treatment of cSSSI. While not specifically focusing on HCAI patients, these authors noted an overall 23% initial therapy failure rate. Among those patients who failed initial therapy, the risk of hospital death was nearly 3‐fold higher (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.91; 95% CI, 2.343.62), and they incurred the mean of 5.4 additional hospital days, compared to patients treated successfully with the initial regimen.8 Our study confirms Edelsberg et al.'s8 observation of prolonged hospital LOS in association with treatment failure, and builds upon it by defining the actual LOS increment attributable to inappropriate empiric therapy. It is worth noting that the study by Edelsberg et al.,8 however, lacked explicit definition of the HCAI population and microbiology data, and used treatment failure as a surrogate marker for inappropriate treatment. It is likely these differences between our two studies in the underlying population and exposure definitions that account for the differences in the mortality data between that study and ours.

It is not fundamentally surprising that early exposure to inappropriate empiric therapy alters healthcare resource utilization outcomes for the worse. Others have demonstrated that infection with a resistant organism results in prolongation of hospital LOS and costs. For example, in a large cohort of over 600 surgical hospitalizations requiring treatment for a gram‐negative infection, antibiotic resistance was an independent predictor of increased LOS and costs.15 These authors quantified the incremental burden of early gram‐negative resistance at over $11,000 in hospital costs.15 Unfortunately, the treatment differences for resistant and sensitive organisms were not examined.15 Similarly, Shorr et al. examined risk factors for prolonged hospital LOS and increased costs in a cohort of 291 patients with MRSA sterile site infection.17 Because in this study 23% of the patients received inappropriate empiric therapy, the authors were able to examine the impact of this exposure on utilization outcomes.17 In an adjusted analysis, inappropriate initial treatment was associated with an incremental increase in the LOS of 2.5 days, corresponding to the unadjusted cost differential of nearly $6,000.17 Although focusing on a different population, our results are consistent with these previous observations that antibiotic resistance and early inappropriate therapy affect hospital utilization parameters, in our case by adding nearly 2 days to the hospital LOS.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, as a retrospective cohort study it is prone to various forms of bias, most notably selection bias. To minimize the possibility of such, we established a priori case definitions and enrolled consecutive patients over a specific period of time. Second, as in any observational study, confounding is an issue. We dealt with this statistically by constructing a multivariable regression model; however, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Third, because some of the wound and ulcer cultures likely were obtained with a swab and thus represented colonization, rather than infection, we may have over‐estimated the rate of inappropriate therapy, and this needs to be followed up in future prospective studies. Similarly, we may have over‐estimated the likelihood of inappropriate therapy among polymicrobial and mixed infections as well, given that, for example, a gram‐negative organism may carry a different clinical significance when cultured from blood (infection) than when it is detected in a decubitus ulcer (potential colonization). Fourth, because we limited our cohort to patients without deep‐seated infections, such as necrotizing fasciitis, other procedures were not collected. This omission may have led to either over‐estimation or under‐estimation of the impact of inappropriate therapy on the outcomes of interest.

The fact that our cohort represents a single large urban academic tertiary care medical center may limit the generalizability of our results only to centers that share similar characteristics. Finally, similar to most other studies of this type, ours lacks data on posthospitalization outcomes and for this reason limits itself to hospital outcomes only.

In summary, we have shown that, similar to other populations with HCAI, a substantial proportion (nearly 1/4) of cSSSI patients with HCAI receive inappropriate empiric therapy for their infection, and this early exposure, though not affecting hospital mortality, is associated with a significant prolongation of the hospitalization by as much as 2 days. Studies are needed to refine decision rules for risk‐stratifying patients with cSSSI HCAI in order to determine the probability of infection with a resistant organism. In turn, such instruments at the bedside may assure improved utilization of appropriately targeted empiric therapy that will both optimize individual patient outcomes and reduce the risk of emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

Appendix

| Principal diagnosis code | Description |

|---|---|

| 680 | Carbuncle and furuncle |

| 681 | Cellulitis and abscess of finger and toe |

| 682 | Other cellulitis and abscess |

| 683 | Acute lymphadenitis |

| 685 | Pilonidal cyst with abscess |

| 686 | Other local infections of skin and subcutaneous tissue |

| 707 | Decubitus ulcer |

| 707.1 | Ulcers of lower limbs, except decubitus |

| 707.8 | Chronic ulcer of other specified sites |

| 707.9 | Chronic ulcer of unspecified site |

| 958.3 | Posttraumatic wound infection, not elsewhere classified |

| 996.62 | Infection due to other vascular device, implant, and graft |

| 997.62 | Infection (chronic) of amputation stump |

| 998.5 | Postoperative wound infection |

| Diagnosis code | Description |

|---|---|

| 728.86 | Necrotizing fasciitis |

| 785.4 | Gangrene |

| 686.09 | Ecthyma gangrenosum |

| 730.00730.2 | Osteomyelitis |

| 630677 | Complications of pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium |

| 288.0 | Neutropenia |

| 684 | Impetigo |

| Procedure code | |

| 39.95 | Plasmapheresis |

| 99.71 | Hemoperfusion |

- ,,, et al.Invasive methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States.JAMA.2007;298:1762–1771.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department.N Engl J Med.2006;17;355:666–674.

- Hospital‐Acquired Pneumonia Guideline Committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America.Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital‐acquired pneumonia, ventilator‐associated pneumonia, and healthcare‐associated pneumonia.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2005;171:388–416.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and outcomes of health‐care‐associated pneumonia: Results from a large US database of culture‐positive pneumonia.Chest.2005;128:3854–3862.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated bloodstream infections in adults: A reason to change the accepted definition of community‐acquired infections.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:791–797.

- ,,,,,.Healthcare‐associated bloodstream infection: A distinct entity? Insights from a large U.S. database.Crit Care Med.2006;34:2588–2595.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated pneumonia and community‐acquired pneumonia: a single‐center experience.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2007;51:3568–3573.

- ,,,,,.Clinical and economic consequences of failure of initial antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and skin‐structure infections.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2008;29:160–169.

- ,,, et al.Skin, soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in hospitalized patients: Epidemiology and microbiological, clinical, and economic outcomes.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2007;28:1290–1298.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus sterile‐site infection: The importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment.Crit Care Med.2006;34:2069–2074.

- ,,, et al.The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting.Chest.2000;118:146–155.

- ,.Modification of empiric antibiotic treatment in patients with pneumonia acquired in the intensive care unit.Intensive Care Med.1996;22:387–394.

- ,,, et al.Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator‐associated pneumonia.Chest.2002;122:262–268.

- ,,,,.Antimicrobial therapy escalation and hospital mortality among patients with HCAP: A single center experience.Chest.2008;134:963–968.

- ,,, et al.Cost of gram‐negative resistance.Crit Care Med.2007;35:89–95.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and outcomes of hospitalizations with complicated skin and skin‐structure infections: implications of healthcare‐associated infection risk factors.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2009;30:1203–1210.

- ,,.Inappropriate therapy for methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus: resource utilization and cost implications.Crit Care Med.2008;36:2335–2340.

Classically, infections have been categorized as either community‐acquired (CAI) or nosocomial in origin. Until recently, this scheme was thought adequate to capture the differences in the microbiology and outcomes in the corresponding scenarios. However, recent evidence suggests that this distinction may no longer be valid. For example, with the spread and diffusion of healthcare delivery beyond the confines of the hospital along with the increasing use of broad spectrum antibiotics both in and out of the hospital, pathogens such as methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA), traditionally thought to be confined to the hospital, are now seen in patients presenting from the community to the emergency department (ED).1, 2 Reflecting this shift in epidemiology, some national guidelines now recognize healthcare‐associated infection (HCAI) as a distinct entity.3 The concept of HCAI allows the clinician to identify patients who, despite suffering a community onset infection, still may be at risk for a resistant bacterial pathogen. Recent studies in both bloodstream infection and pneumonia have clearly demonstrated that those with HCAI have distinct microbiology and outcomes relative to those with pure CAI.47

Most work focusing on establishing HCAI has not addressed skin and soft tissue infections. These infections, although not often fatal, account for an increasing number of admissions to the hospital.8, 9 In addition, they may be associated with substantial morbidity and cost.8 Given that many pathogens such as S. aureus, which may be resistant to typical antimicrobials used in the ED, are also major culprits in complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI), the HCAI paradigm may apply in cSSSI. Furthermore, because of these patterns of increased resistance, HCA‐cSSSI patients, similar to other HCAI groups, may be at an increased risk of being treated with initially inappropriate antibiotic therapy.7, 10

Since in the setting of other types of infection inappropriate empiric treatment has been shown to be associated with increased mortality and costs,7, 1015 and since indirect evidence suggests a similar impact on healthcare utilization among cSSSI patients,8 we hypothesized that among a cohort of patients hospitalized with a cSSSI, the initial empiric choice of therapy is independently associated with hospital length of stay (LOS). We performed a retrospective cohort study to address this question.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a single‐center retrospective cohort study of patients with cSSSI admitted to the hospital through the ED. All consecutive patients hospitalized between April 2006 and December 2007 meeting predefined inclusion criteria (see below) were enrolled. The study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee, and informed consent was waived. We have previously reported on the characteristics and outcomes of this cohort, including both community‐acquired and HCA‐cSSSI patients.16

Study Cohort

All consecutive patients admitted from the community through the ED between April 2006 and December 2007 at the Barnes‐Jewish Hospital, a 1200‐bed university‐affiliated, urban teaching hospital in St. Louis, MO were included if: (1) they had a diagnosis of a predefined cSSSI (see Appendix Table A1, based on reference 8) and (2) they had a positive microbiology culture obtained within 24 hours of hospital admission. Similar to the work by Edelsberg et al.8 we excluded patients if certain diagnoses and procedures were present (Appendix Table A2). Cases were also excluded if they represented a readmission for the same diagnosis within 30 days of the original hospitalization.

Definitions

HCAI was defined as any cSSSI in a patient with a history of recent hospitalization (within the previous year, consistent with the previous study16), receiving antibiotics prior to admission (previous 90 days), transferring from a nursing home, or needing chronic dialysis. We defined a polymicrobial infection as one with more than one organism, and mixed infection as an infection with both a gram‐positive and a gram‐negative organism. Inappropriate empiric therapy took place if a patient did not receive treatment within 24 hours of the time the culture was obtained with an agent exhibiting in vitro activity against the isolated pathogen(s). In mixed infections, appropriate therapy was treatment within 24 hours of culture being obtained with agent(s) active against all pathogens recovered.

Data Elements

We collected information about multiple baseline demographic and clinical factors including: age, gender, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, the presence of risk factors for HCAI, the presence of bacteremia at admission, and the location of admission (ward vs. intensive care unit [ICU]). Bacteriology data included information on specific bacterium/a recovered from culture, the site of the culture (eg, tissue, blood), susceptibility patterns, and whether the infection was monomicrobial, polymicrobial, or mixed. When blood culture was available and positive, we prioritized this over wound and other cultures and designated the corresponding organism as the culprit in the index infection. Cultures growing our coagulase‐negative S. aureus were excluded as a probable contaminant. Treatment data included information on the choice of the antimicrobial therapy and the timing of its institution relative to the timing of obtaining the culture specimen. The presence of such procedures as incision and drainage (I&D) or debridement was recorded.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics comparing HCAI patients treated appropriately to those receiving inappropriate empiric coverage based on their clinical, demographic, microbiologic and treatment characteristics were computed. Hospital LOS served as the primary and hospital mortality as the secondary outcomes, comparing patients with HCAI treated appropriately to those treated inappropriately. All continuous variables were compared using Student's t test or the Mann‐Whitney U test as appropriate. All categorical variables were compared using the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. To assess the attributable impact of inappropriate therapy in HCAI on the outcomes of interest, general linear models with log transformation were developed to model hospital LOS parameters; all means are presented as geometric means. All potential risk factors significant at the 0.1 level in univariate analyses were entered into the model. All calculations were performed in Stata version 9 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 717 patients with culture‐positive cSSSI admitted during the study period, 527 (73.5%) were classified as HCAI. The most common reason for classification as an HCAI was recent hospitalization. Among those with an HCA‐cSSSI, 405 (76.9%) received appropriate empiric treatment, with nearly one‐quarter receiving inappropriate initial coverage. Those receiving inappropriate antibiotic were more likely to be African American, and had a higher likelihood of having end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) than those with appropriate coverage (Table 1). While those patients treated appropriately had higher rates of both cellulitis and abscess as the presenting infection, a substantially higher proportion of those receiving inappropriate initial treatment had a decubitus ulcer (29.5% vs. 10.9%, P <0.001), a device‐associated infection (42.6% vs. 28.6%, P = 0.004), and had evidence of bacteremia (68.9% vs. 57.8%, P = 0.028) than those receiving appropriate empiric coverage (Table 2).

| Inappropriate (n = 122), n (%) | Appropriate (n = 405), n (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, years | 56.3 18.0 | 53.6 16.7 | 0.147 |

| Gender (F) | 62 (50.8) | 190 (46.9) | 0.449 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 51 (41.8) | 219 (54.1) | 0.048 |

| African American | 68 (55.7) | 178 (43.9) | |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 8 (2.0) | |

| HCAI risk factors | |||

| Recent hospitalization* | 110 (90.2) | 373 (92.1) | 0.498 |

| Within 90 days | 98 (80.3) | 274 (67.7) | 0.007 |

| >90 and 180 days | 52 (42.6) | 170 (42.0) | 0.899 |

| >180 days and 1 year | 46 (37.7) | 164 (40.5) | 0.581 |

| Prior antibiotics | 26 (21.3) | 90 (22.2) | 0.831 |

| Nursing home resident | 29 (23.8) | 54 (13.3) | 0.006 |

| Hemodialysis | 19 (15.6) | 39 (9.7) | 0.067 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| DM | 40 (37.8) | 128 (31.6) | 0.806 |

| PVD | 5 (4.1) | 15 (3.7) | 0.841 |

| Liver disease | 6 (4.9) | 33 (8.2) | 0.232 |

| Cancer | 21 (17.2) | 85 (21.0) | 0.362 |

| HIV | 1 (0.8) | 12 (3.0) | 0.316 |

| Organ transplant | 2 (1.6) | 8 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Autoimmune disease | 5 (4.1) | 8 (2.0) | 0.185 |

| ESRD | 22 (18.0) | 46 (11.4) | 0.054 |

| Inappropriate (n = 122), n (%) | Appropriate (n = 405), n (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Cellulitis | 28 (23.0) | 171 (42.2) | <0.001 |

| Decubitus ulcer | 36 (29.5) | 44 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Post‐op wound | 25 (20.5) | 75 (18.5) | 0.626 |

| Device‐associated infection | 52 (42.6) | 116 (28.6) | 0.004 |

| Diabetic foot ulcer | 9 (7.4) | 24 (5.9) | 0.562 |

| Abscess | 22 (18.0) | 108 (26.7) | 0.052 |

| Other* | 2 (1.6) | 17 (4.2) | 0.269 |

| Presence of bacteremia | 84 (68.9) | 234 (57.8) | 0.028 |

The pathogens recovered from the appropriately and inappropriately treated groups are listed in Figure 1. While S. aureus overall was more common among those treated appropriately, the frequency of MRSA did not differ between the groups. Both E. faecalis and E. faecium were recovered more frequently in the inappropriate group, resulting in a similar pattern among the vancomycin‐resistant enterococcal species. Likewise, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, and A. baumannii were all more frequently seen in the group treated inappropriately than in the group getting appropriate empiric coverage. A mixed infection was also more likely to be present among those not exposed (16.5%) than among those exposed (7.5%) to appropriate early therapy (P = 0.001) (Figure 1).

In terms of processes of care and outcomes (Table 3), commensurate with the higher prevalence of abscess in the appropriately treated group, the rate of I&D was significantly higher in this cohort (36.8%) than in the inappropriately treated (23.0%) group (P = 0.005). Need for initial ICU care did not differ as a function of appropriateness of therapy (P = 0.635).

| Inappropriate (n = 122) | Appropriate (n = 405) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| I&D/debridement | 28 (23.0%) | 149 (36.8%) | 0.005 |

| I&D in ED | 0 | 7 (1.7) | 0.361 |

| ICU | 9 (7.4%) | 25 (6.2%) | 0.635 |

| Hospital LOS, days | |||

| Median (IQR 25, 75) [Range] | 7.0 (4.2, 13.6) [0.686.6] | 6 (3.3, 10.1) [0.748.3] | 0.026 |

| Hospital mortality | 9 (7.4%) | 26 (6.4%) | 0.710 |

The unadjusted mortality rate was low overall and did not vary based on initial treatment (Table 3). In a generalized linear model with the log‐transformed LOS as the dependent variable, adjusting for multiple potential confounders, initial inappropriate antibiotic therapy had an attributable incremental increase in the hospital LOS of 1.8 days (95% CI, 1.42.3) (Table 4).

| Factor | Attributable LOS (days) | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Infection type: device | 3.6 | 2.74.8 | <0.001 |

| Infection type: decubitus ulcer | 3.3 | 2.64.2 | <0.001 |

| Infection type: abscess | 2.5 | 1.64.0 | <0.001 |

| Organism: P. mirabilis | 2.2 | 1.43.4 | <0.001 |

| Organism: E. faecalis | 2.1 | 1.72.6 | <0.001 |

| Nursing home resident | 2.1 | 1.62.6 | <0.001 |

| Inappropriate antibiotic | 1.8 | 1.42.3 | <0.001 |

| Race: Non‐Caucasian | 0.31 | 0.240.41 | <0.001 |

| Organism: E. faecium | 0.23 | 0.150.35 | <0.001 |

Because bacteremia is known to be an effect modifier of the relationship between the empiric choice of antibiotic and infection outcomes, we further explored its role in the HCAI cSSSI on the outcomes of interest (Table 5). Similar to the effect detected in the overall cohort, treatment with inappropriate therapy was associated with an increase in the hospital LOS, but not hospital mortality in those with bacteremia, though this phenomenon was observed only among patients with secondary bacteremia, and not among those without (Table 5).

| Bacteremia Present (n = 318) | Bacteremia Absent (n = 209) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (n = 84) | A (n = 234) | P Value | I (n = 38) | A (n = 171) | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Hospital LOS, days | ||||||

| Mean SD | 14.4 27.5 | 9.8 9.7 | 0.041 | 6.6 6.8 | 6.9 8.2 | 0.761 |

| Median (IQR 25, 75) | 8.8 (5.4, 13.9) | 7.0 (4.3, 11.7) | 4.4 (2.4, 7.7) | 3.9 (2.0, 8.2) | ||

| Hospital mortality | 8 (9.5%) | 24 (10.3%) | 0.848 | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.454 |

Discussion

This retrospective analysis provides evidence that inappropriate empiric antibiotic therapy for HCA‐cSSSI independently prolongs hospital LOS. The impact of inappropriate initial treatment on LOS is independent of many important confounders. In addition, we observed that this effect, while present among patients with secondary bacteremia, is absent among those without a blood stream infection.

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first cohort study to examine the outcomes associated with inappropriate treatment of a HCAI cSSSI within the context of available microbiology data. Edelsberg et al.8 examined clinical and economic outcomes associated with the failure of the initial treatment of cSSSI. While not specifically focusing on HCAI patients, these authors noted an overall 23% initial therapy failure rate. Among those patients who failed initial therapy, the risk of hospital death was nearly 3‐fold higher (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.91; 95% CI, 2.343.62), and they incurred the mean of 5.4 additional hospital days, compared to patients treated successfully with the initial regimen.8 Our study confirms Edelsberg et al.'s8 observation of prolonged hospital LOS in association with treatment failure, and builds upon it by defining the actual LOS increment attributable to inappropriate empiric therapy. It is worth noting that the study by Edelsberg et al.,8 however, lacked explicit definition of the HCAI population and microbiology data, and used treatment failure as a surrogate marker for inappropriate treatment. It is likely these differences between our two studies in the underlying population and exposure definitions that account for the differences in the mortality data between that study and ours.

It is not fundamentally surprising that early exposure to inappropriate empiric therapy alters healthcare resource utilization outcomes for the worse. Others have demonstrated that infection with a resistant organism results in prolongation of hospital LOS and costs. For example, in a large cohort of over 600 surgical hospitalizations requiring treatment for a gram‐negative infection, antibiotic resistance was an independent predictor of increased LOS and costs.15 These authors quantified the incremental burden of early gram‐negative resistance at over $11,000 in hospital costs.15 Unfortunately, the treatment differences for resistant and sensitive organisms were not examined.15 Similarly, Shorr et al. examined risk factors for prolonged hospital LOS and increased costs in a cohort of 291 patients with MRSA sterile site infection.17 Because in this study 23% of the patients received inappropriate empiric therapy, the authors were able to examine the impact of this exposure on utilization outcomes.17 In an adjusted analysis, inappropriate initial treatment was associated with an incremental increase in the LOS of 2.5 days, corresponding to the unadjusted cost differential of nearly $6,000.17 Although focusing on a different population, our results are consistent with these previous observations that antibiotic resistance and early inappropriate therapy affect hospital utilization parameters, in our case by adding nearly 2 days to the hospital LOS.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, as a retrospective cohort study it is prone to various forms of bias, most notably selection bias. To minimize the possibility of such, we established a priori case definitions and enrolled consecutive patients over a specific period of time. Second, as in any observational study, confounding is an issue. We dealt with this statistically by constructing a multivariable regression model; however, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Third, because some of the wound and ulcer cultures likely were obtained with a swab and thus represented colonization, rather than infection, we may have over‐estimated the rate of inappropriate therapy, and this needs to be followed up in future prospective studies. Similarly, we may have over‐estimated the likelihood of inappropriate therapy among polymicrobial and mixed infections as well, given that, for example, a gram‐negative organism may carry a different clinical significance when cultured from blood (infection) than when it is detected in a decubitus ulcer (potential colonization). Fourth, because we limited our cohort to patients without deep‐seated infections, such as necrotizing fasciitis, other procedures were not collected. This omission may have led to either over‐estimation or under‐estimation of the impact of inappropriate therapy on the outcomes of interest.

The fact that our cohort represents a single large urban academic tertiary care medical center may limit the generalizability of our results only to centers that share similar characteristics. Finally, similar to most other studies of this type, ours lacks data on posthospitalization outcomes and for this reason limits itself to hospital outcomes only.

In summary, we have shown that, similar to other populations with HCAI, a substantial proportion (nearly 1/4) of cSSSI patients with HCAI receive inappropriate empiric therapy for their infection, and this early exposure, though not affecting hospital mortality, is associated with a significant prolongation of the hospitalization by as much as 2 days. Studies are needed to refine decision rules for risk‐stratifying patients with cSSSI HCAI in order to determine the probability of infection with a resistant organism. In turn, such instruments at the bedside may assure improved utilization of appropriately targeted empiric therapy that will both optimize individual patient outcomes and reduce the risk of emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

Appendix

| Principal diagnosis code | Description |

|---|---|

| 680 | Carbuncle and furuncle |

| 681 | Cellulitis and abscess of finger and toe |

| 682 | Other cellulitis and abscess |

| 683 | Acute lymphadenitis |

| 685 | Pilonidal cyst with abscess |

| 686 | Other local infections of skin and subcutaneous tissue |

| 707 | Decubitus ulcer |

| 707.1 | Ulcers of lower limbs, except decubitus |

| 707.8 | Chronic ulcer of other specified sites |

| 707.9 | Chronic ulcer of unspecified site |

| 958.3 | Posttraumatic wound infection, not elsewhere classified |

| 996.62 | Infection due to other vascular device, implant, and graft |

| 997.62 | Infection (chronic) of amputation stump |

| 998.5 | Postoperative wound infection |

| Diagnosis code | Description |

|---|---|

| 728.86 | Necrotizing fasciitis |

| 785.4 | Gangrene |

| 686.09 | Ecthyma gangrenosum |

| 730.00730.2 | Osteomyelitis |

| 630677 | Complications of pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium |

| 288.0 | Neutropenia |

| 684 | Impetigo |

| Procedure code | |

| 39.95 | Plasmapheresis |

| 99.71 | Hemoperfusion |

Classically, infections have been categorized as either community‐acquired (CAI) or nosocomial in origin. Until recently, this scheme was thought adequate to capture the differences in the microbiology and outcomes in the corresponding scenarios. However, recent evidence suggests that this distinction may no longer be valid. For example, with the spread and diffusion of healthcare delivery beyond the confines of the hospital along with the increasing use of broad spectrum antibiotics both in and out of the hospital, pathogens such as methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA), traditionally thought to be confined to the hospital, are now seen in patients presenting from the community to the emergency department (ED).1, 2 Reflecting this shift in epidemiology, some national guidelines now recognize healthcare‐associated infection (HCAI) as a distinct entity.3 The concept of HCAI allows the clinician to identify patients who, despite suffering a community onset infection, still may be at risk for a resistant bacterial pathogen. Recent studies in both bloodstream infection and pneumonia have clearly demonstrated that those with HCAI have distinct microbiology and outcomes relative to those with pure CAI.47

Most work focusing on establishing HCAI has not addressed skin and soft tissue infections. These infections, although not often fatal, account for an increasing number of admissions to the hospital.8, 9 In addition, they may be associated with substantial morbidity and cost.8 Given that many pathogens such as S. aureus, which may be resistant to typical antimicrobials used in the ED, are also major culprits in complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI), the HCAI paradigm may apply in cSSSI. Furthermore, because of these patterns of increased resistance, HCA‐cSSSI patients, similar to other HCAI groups, may be at an increased risk of being treated with initially inappropriate antibiotic therapy.7, 10

Since in the setting of other types of infection inappropriate empiric treatment has been shown to be associated with increased mortality and costs,7, 1015 and since indirect evidence suggests a similar impact on healthcare utilization among cSSSI patients,8 we hypothesized that among a cohort of patients hospitalized with a cSSSI, the initial empiric choice of therapy is independently associated with hospital length of stay (LOS). We performed a retrospective cohort study to address this question.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a single‐center retrospective cohort study of patients with cSSSI admitted to the hospital through the ED. All consecutive patients hospitalized between April 2006 and December 2007 meeting predefined inclusion criteria (see below) were enrolled. The study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee, and informed consent was waived. We have previously reported on the characteristics and outcomes of this cohort, including both community‐acquired and HCA‐cSSSI patients.16

Study Cohort

All consecutive patients admitted from the community through the ED between April 2006 and December 2007 at the Barnes‐Jewish Hospital, a 1200‐bed university‐affiliated, urban teaching hospital in St. Louis, MO were included if: (1) they had a diagnosis of a predefined cSSSI (see Appendix Table A1, based on reference 8) and (2) they had a positive microbiology culture obtained within 24 hours of hospital admission. Similar to the work by Edelsberg et al.8 we excluded patients if certain diagnoses and procedures were present (Appendix Table A2). Cases were also excluded if they represented a readmission for the same diagnosis within 30 days of the original hospitalization.

Definitions

HCAI was defined as any cSSSI in a patient with a history of recent hospitalization (within the previous year, consistent with the previous study16), receiving antibiotics prior to admission (previous 90 days), transferring from a nursing home, or needing chronic dialysis. We defined a polymicrobial infection as one with more than one organism, and mixed infection as an infection with both a gram‐positive and a gram‐negative organism. Inappropriate empiric therapy took place if a patient did not receive treatment within 24 hours of the time the culture was obtained with an agent exhibiting in vitro activity against the isolated pathogen(s). In mixed infections, appropriate therapy was treatment within 24 hours of culture being obtained with agent(s) active against all pathogens recovered.

Data Elements

We collected information about multiple baseline demographic and clinical factors including: age, gender, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, the presence of risk factors for HCAI, the presence of bacteremia at admission, and the location of admission (ward vs. intensive care unit [ICU]). Bacteriology data included information on specific bacterium/a recovered from culture, the site of the culture (eg, tissue, blood), susceptibility patterns, and whether the infection was monomicrobial, polymicrobial, or mixed. When blood culture was available and positive, we prioritized this over wound and other cultures and designated the corresponding organism as the culprit in the index infection. Cultures growing our coagulase‐negative S. aureus were excluded as a probable contaminant. Treatment data included information on the choice of the antimicrobial therapy and the timing of its institution relative to the timing of obtaining the culture specimen. The presence of such procedures as incision and drainage (I&D) or debridement was recorded.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics comparing HCAI patients treated appropriately to those receiving inappropriate empiric coverage based on their clinical, demographic, microbiologic and treatment characteristics were computed. Hospital LOS served as the primary and hospital mortality as the secondary outcomes, comparing patients with HCAI treated appropriately to those treated inappropriately. All continuous variables were compared using Student's t test or the Mann‐Whitney U test as appropriate. All categorical variables were compared using the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. To assess the attributable impact of inappropriate therapy in HCAI on the outcomes of interest, general linear models with log transformation were developed to model hospital LOS parameters; all means are presented as geometric means. All potential risk factors significant at the 0.1 level in univariate analyses were entered into the model. All calculations were performed in Stata version 9 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 717 patients with culture‐positive cSSSI admitted during the study period, 527 (73.5%) were classified as HCAI. The most common reason for classification as an HCAI was recent hospitalization. Among those with an HCA‐cSSSI, 405 (76.9%) received appropriate empiric treatment, with nearly one‐quarter receiving inappropriate initial coverage. Those receiving inappropriate antibiotic were more likely to be African American, and had a higher likelihood of having end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) than those with appropriate coverage (Table 1). While those patients treated appropriately had higher rates of both cellulitis and abscess as the presenting infection, a substantially higher proportion of those receiving inappropriate initial treatment had a decubitus ulcer (29.5% vs. 10.9%, P <0.001), a device‐associated infection (42.6% vs. 28.6%, P = 0.004), and had evidence of bacteremia (68.9% vs. 57.8%, P = 0.028) than those receiving appropriate empiric coverage (Table 2).

| Inappropriate (n = 122), n (%) | Appropriate (n = 405), n (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, years | 56.3 18.0 | 53.6 16.7 | 0.147 |

| Gender (F) | 62 (50.8) | 190 (46.9) | 0.449 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 51 (41.8) | 219 (54.1) | 0.048 |

| African American | 68 (55.7) | 178 (43.9) | |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 8 (2.0) | |

| HCAI risk factors | |||

| Recent hospitalization* | 110 (90.2) | 373 (92.1) | 0.498 |

| Within 90 days | 98 (80.3) | 274 (67.7) | 0.007 |

| >90 and 180 days | 52 (42.6) | 170 (42.0) | 0.899 |

| >180 days and 1 year | 46 (37.7) | 164 (40.5) | 0.581 |

| Prior antibiotics | 26 (21.3) | 90 (22.2) | 0.831 |

| Nursing home resident | 29 (23.8) | 54 (13.3) | 0.006 |

| Hemodialysis | 19 (15.6) | 39 (9.7) | 0.067 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| DM | 40 (37.8) | 128 (31.6) | 0.806 |

| PVD | 5 (4.1) | 15 (3.7) | 0.841 |

| Liver disease | 6 (4.9) | 33 (8.2) | 0.232 |

| Cancer | 21 (17.2) | 85 (21.0) | 0.362 |

| HIV | 1 (0.8) | 12 (3.0) | 0.316 |

| Organ transplant | 2 (1.6) | 8 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Autoimmune disease | 5 (4.1) | 8 (2.0) | 0.185 |

| ESRD | 22 (18.0) | 46 (11.4) | 0.054 |

| Inappropriate (n = 122), n (%) | Appropriate (n = 405), n (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Cellulitis | 28 (23.0) | 171 (42.2) | <0.001 |

| Decubitus ulcer | 36 (29.5) | 44 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Post‐op wound | 25 (20.5) | 75 (18.5) | 0.626 |

| Device‐associated infection | 52 (42.6) | 116 (28.6) | 0.004 |

| Diabetic foot ulcer | 9 (7.4) | 24 (5.9) | 0.562 |

| Abscess | 22 (18.0) | 108 (26.7) | 0.052 |

| Other* | 2 (1.6) | 17 (4.2) | 0.269 |

| Presence of bacteremia | 84 (68.9) | 234 (57.8) | 0.028 |

The pathogens recovered from the appropriately and inappropriately treated groups are listed in Figure 1. While S. aureus overall was more common among those treated appropriately, the frequency of MRSA did not differ between the groups. Both E. faecalis and E. faecium were recovered more frequently in the inappropriate group, resulting in a similar pattern among the vancomycin‐resistant enterococcal species. Likewise, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, and A. baumannii were all more frequently seen in the group treated inappropriately than in the group getting appropriate empiric coverage. A mixed infection was also more likely to be present among those not exposed (16.5%) than among those exposed (7.5%) to appropriate early therapy (P = 0.001) (Figure 1).

In terms of processes of care and outcomes (Table 3), commensurate with the higher prevalence of abscess in the appropriately treated group, the rate of I&D was significantly higher in this cohort (36.8%) than in the inappropriately treated (23.0%) group (P = 0.005). Need for initial ICU care did not differ as a function of appropriateness of therapy (P = 0.635).

| Inappropriate (n = 122) | Appropriate (n = 405) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| I&D/debridement | 28 (23.0%) | 149 (36.8%) | 0.005 |

| I&D in ED | 0 | 7 (1.7) | 0.361 |

| ICU | 9 (7.4%) | 25 (6.2%) | 0.635 |

| Hospital LOS, days | |||

| Median (IQR 25, 75) [Range] | 7.0 (4.2, 13.6) [0.686.6] | 6 (3.3, 10.1) [0.748.3] | 0.026 |

| Hospital mortality | 9 (7.4%) | 26 (6.4%) | 0.710 |

The unadjusted mortality rate was low overall and did not vary based on initial treatment (Table 3). In a generalized linear model with the log‐transformed LOS as the dependent variable, adjusting for multiple potential confounders, initial inappropriate antibiotic therapy had an attributable incremental increase in the hospital LOS of 1.8 days (95% CI, 1.42.3) (Table 4).

| Factor | Attributable LOS (days) | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Infection type: device | 3.6 | 2.74.8 | <0.001 |

| Infection type: decubitus ulcer | 3.3 | 2.64.2 | <0.001 |

| Infection type: abscess | 2.5 | 1.64.0 | <0.001 |

| Organism: P. mirabilis | 2.2 | 1.43.4 | <0.001 |

| Organism: E. faecalis | 2.1 | 1.72.6 | <0.001 |

| Nursing home resident | 2.1 | 1.62.6 | <0.001 |

| Inappropriate antibiotic | 1.8 | 1.42.3 | <0.001 |

| Race: Non‐Caucasian | 0.31 | 0.240.41 | <0.001 |

| Organism: E. faecium | 0.23 | 0.150.35 | <0.001 |

Because bacteremia is known to be an effect modifier of the relationship between the empiric choice of antibiotic and infection outcomes, we further explored its role in the HCAI cSSSI on the outcomes of interest (Table 5). Similar to the effect detected in the overall cohort, treatment with inappropriate therapy was associated with an increase in the hospital LOS, but not hospital mortality in those with bacteremia, though this phenomenon was observed only among patients with secondary bacteremia, and not among those without (Table 5).

| Bacteremia Present (n = 318) | Bacteremia Absent (n = 209) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (n = 84) | A (n = 234) | P Value | I (n = 38) | A (n = 171) | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Hospital LOS, days | ||||||

| Mean SD | 14.4 27.5 | 9.8 9.7 | 0.041 | 6.6 6.8 | 6.9 8.2 | 0.761 |

| Median (IQR 25, 75) | 8.8 (5.4, 13.9) | 7.0 (4.3, 11.7) | 4.4 (2.4, 7.7) | 3.9 (2.0, 8.2) | ||

| Hospital mortality | 8 (9.5%) | 24 (10.3%) | 0.848 | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | 0.454 |

Discussion

This retrospective analysis provides evidence that inappropriate empiric antibiotic therapy for HCA‐cSSSI independently prolongs hospital LOS. The impact of inappropriate initial treatment on LOS is independent of many important confounders. In addition, we observed that this effect, while present among patients with secondary bacteremia, is absent among those without a blood stream infection.

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first cohort study to examine the outcomes associated with inappropriate treatment of a HCAI cSSSI within the context of available microbiology data. Edelsberg et al.8 examined clinical and economic outcomes associated with the failure of the initial treatment of cSSSI. While not specifically focusing on HCAI patients, these authors noted an overall 23% initial therapy failure rate. Among those patients who failed initial therapy, the risk of hospital death was nearly 3‐fold higher (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.91; 95% CI, 2.343.62), and they incurred the mean of 5.4 additional hospital days, compared to patients treated successfully with the initial regimen.8 Our study confirms Edelsberg et al.'s8 observation of prolonged hospital LOS in association with treatment failure, and builds upon it by defining the actual LOS increment attributable to inappropriate empiric therapy. It is worth noting that the study by Edelsberg et al.,8 however, lacked explicit definition of the HCAI population and microbiology data, and used treatment failure as a surrogate marker for inappropriate treatment. It is likely these differences between our two studies in the underlying population and exposure definitions that account for the differences in the mortality data between that study and ours.

It is not fundamentally surprising that early exposure to inappropriate empiric therapy alters healthcare resource utilization outcomes for the worse. Others have demonstrated that infection with a resistant organism results in prolongation of hospital LOS and costs. For example, in a large cohort of over 600 surgical hospitalizations requiring treatment for a gram‐negative infection, antibiotic resistance was an independent predictor of increased LOS and costs.15 These authors quantified the incremental burden of early gram‐negative resistance at over $11,000 in hospital costs.15 Unfortunately, the treatment differences for resistant and sensitive organisms were not examined.15 Similarly, Shorr et al. examined risk factors for prolonged hospital LOS and increased costs in a cohort of 291 patients with MRSA sterile site infection.17 Because in this study 23% of the patients received inappropriate empiric therapy, the authors were able to examine the impact of this exposure on utilization outcomes.17 In an adjusted analysis, inappropriate initial treatment was associated with an incremental increase in the LOS of 2.5 days, corresponding to the unadjusted cost differential of nearly $6,000.17 Although focusing on a different population, our results are consistent with these previous observations that antibiotic resistance and early inappropriate therapy affect hospital utilization parameters, in our case by adding nearly 2 days to the hospital LOS.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, as a retrospective cohort study it is prone to various forms of bias, most notably selection bias. To minimize the possibility of such, we established a priori case definitions and enrolled consecutive patients over a specific period of time. Second, as in any observational study, confounding is an issue. We dealt with this statistically by constructing a multivariable regression model; however, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Third, because some of the wound and ulcer cultures likely were obtained with a swab and thus represented colonization, rather than infection, we may have over‐estimated the rate of inappropriate therapy, and this needs to be followed up in future prospective studies. Similarly, we may have over‐estimated the likelihood of inappropriate therapy among polymicrobial and mixed infections as well, given that, for example, a gram‐negative organism may carry a different clinical significance when cultured from blood (infection) than when it is detected in a decubitus ulcer (potential colonization). Fourth, because we limited our cohort to patients without deep‐seated infections, such as necrotizing fasciitis, other procedures were not collected. This omission may have led to either over‐estimation or under‐estimation of the impact of inappropriate therapy on the outcomes of interest.

The fact that our cohort represents a single large urban academic tertiary care medical center may limit the generalizability of our results only to centers that share similar characteristics. Finally, similar to most other studies of this type, ours lacks data on posthospitalization outcomes and for this reason limits itself to hospital outcomes only.

In summary, we have shown that, similar to other populations with HCAI, a substantial proportion (nearly 1/4) of cSSSI patients with HCAI receive inappropriate empiric therapy for their infection, and this early exposure, though not affecting hospital mortality, is associated with a significant prolongation of the hospitalization by as much as 2 days. Studies are needed to refine decision rules for risk‐stratifying patients with cSSSI HCAI in order to determine the probability of infection with a resistant organism. In turn, such instruments at the bedside may assure improved utilization of appropriately targeted empiric therapy that will both optimize individual patient outcomes and reduce the risk of emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

Appendix

| Principal diagnosis code | Description |

|---|---|

| 680 | Carbuncle and furuncle |

| 681 | Cellulitis and abscess of finger and toe |

| 682 | Other cellulitis and abscess |

| 683 | Acute lymphadenitis |

| 685 | Pilonidal cyst with abscess |

| 686 | Other local infections of skin and subcutaneous tissue |

| 707 | Decubitus ulcer |

| 707.1 | Ulcers of lower limbs, except decubitus |

| 707.8 | Chronic ulcer of other specified sites |

| 707.9 | Chronic ulcer of unspecified site |

| 958.3 | Posttraumatic wound infection, not elsewhere classified |

| 996.62 | Infection due to other vascular device, implant, and graft |

| 997.62 | Infection (chronic) of amputation stump |

| 998.5 | Postoperative wound infection |

| Diagnosis code | Description |

|---|---|

| 728.86 | Necrotizing fasciitis |

| 785.4 | Gangrene |

| 686.09 | Ecthyma gangrenosum |

| 730.00730.2 | Osteomyelitis |

| 630677 | Complications of pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium |

| 288.0 | Neutropenia |

| 684 | Impetigo |

| Procedure code | |

| 39.95 | Plasmapheresis |

| 99.71 | Hemoperfusion |

- ,,, et al.Invasive methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States.JAMA.2007;298:1762–1771.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department.N Engl J Med.2006;17;355:666–674.

- Hospital‐Acquired Pneumonia Guideline Committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America.Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital‐acquired pneumonia, ventilator‐associated pneumonia, and healthcare‐associated pneumonia.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2005;171:388–416.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and outcomes of health‐care‐associated pneumonia: Results from a large US database of culture‐positive pneumonia.Chest.2005;128:3854–3862.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated bloodstream infections in adults: A reason to change the accepted definition of community‐acquired infections.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:791–797.

- ,,,,,.Healthcare‐associated bloodstream infection: A distinct entity? Insights from a large U.S. database.Crit Care Med.2006;34:2588–2595.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated pneumonia and community‐acquired pneumonia: a single‐center experience.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2007;51:3568–3573.

- ,,,,,.Clinical and economic consequences of failure of initial antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and skin‐structure infections.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2008;29:160–169.

- ,,, et al.Skin, soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in hospitalized patients: Epidemiology and microbiological, clinical, and economic outcomes.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2007;28:1290–1298.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus sterile‐site infection: The importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment.Crit Care Med.2006;34:2069–2074.

- ,,, et al.The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting.Chest.2000;118:146–155.

- ,.Modification of empiric antibiotic treatment in patients with pneumonia acquired in the intensive care unit.Intensive Care Med.1996;22:387–394.

- ,,, et al.Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator‐associated pneumonia.Chest.2002;122:262–268.

- ,,,,.Antimicrobial therapy escalation and hospital mortality among patients with HCAP: A single center experience.Chest.2008;134:963–968.

- ,,, et al.Cost of gram‐negative resistance.Crit Care Med.2007;35:89–95.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and outcomes of hospitalizations with complicated skin and skin‐structure infections: implications of healthcare‐associated infection risk factors.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2009;30:1203–1210.

- ,,.Inappropriate therapy for methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus: resource utilization and cost implications.Crit Care Med.2008;36:2335–2340.

- ,,, et al.Invasive methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States.JAMA.2007;298:1762–1771.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department.N Engl J Med.2006;17;355:666–674.

- Hospital‐Acquired Pneumonia Guideline Committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America.Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital‐acquired pneumonia, ventilator‐associated pneumonia, and healthcare‐associated pneumonia.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2005;171:388–416.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and outcomes of health‐care‐associated pneumonia: Results from a large US database of culture‐positive pneumonia.Chest.2005;128:3854–3862.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated bloodstream infections in adults: A reason to change the accepted definition of community‐acquired infections.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:791–797.

- ,,,,,.Healthcare‐associated bloodstream infection: A distinct entity? Insights from a large U.S. database.Crit Care Med.2006;34:2588–2595.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated pneumonia and community‐acquired pneumonia: a single‐center experience.Antimicrob Agents Chemother.2007;51:3568–3573.

- ,,,,,.Clinical and economic consequences of failure of initial antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and skin‐structure infections.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2008;29:160–169.

- ,,, et al.Skin, soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in hospitalized patients: Epidemiology and microbiological, clinical, and economic outcomes.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2007;28:1290–1298.

- ,,, et al.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus sterile‐site infection: The importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment.Crit Care Med.2006;34:2069–2074.

- ,,, et al.The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting.Chest.2000;118:146–155.

- ,.Modification of empiric antibiotic treatment in patients with pneumonia acquired in the intensive care unit.Intensive Care Med.1996;22:387–394.

- ,,, et al.Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator‐associated pneumonia.Chest.2002;122:262–268.

- ,,,,.Antimicrobial therapy escalation and hospital mortality among patients with HCAP: A single center experience.Chest.2008;134:963–968.

- ,,, et al.Cost of gram‐negative resistance.Crit Care Med.2007;35:89–95.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and outcomes of hospitalizations with complicated skin and skin‐structure infections: implications of healthcare‐associated infection risk factors.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2009;30:1203–1210.

- ,,.Inappropriate therapy for methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus: resource utilization and cost implications.Crit Care Med.2008;36:2335–2340.

Copyright © 2010 Society of Hospital Medicine