User login

Pregnancy, breastfeeding, and more linked to lower CRC risk

Estrogen exposure helps protect against colorectal cancer (CRC), and in some instances, the protection is site specific, a new analysis finds.

In a 17-year study involving almost 5,000 women, researchers from Germany found that hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and menopause at age 50 or older were all significantly associated with reductions in CRC risk.

Interestingly, the reduced risk of CRC observed for pregnancy and breastfeeding only applied to proximal colon cancer, while the association with oral contraceptive use was confined to the distal colon and rectum.

The results were published online in JNCI Cancer Spectrum.

CRC is the second most common cause of cancer death. It is responsible for more than one million deaths globally, according to the latest figures from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration.

And sex seems to make a difference. The Global Burden analysis, echoing previous data, found that CRC is less common among women and that fewer women die from the disease.

Little, however, is known about the mechanisms of estrogen signaling in CRC or the impact of reproductive factors on CRC, despite a large amount of literature linking CRC risk to exogenous estrogens, such as hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives.

In the current analysis, the team recruited 2,650 patients with CRC from 20 German cancer centers between 2003 and 2020. Researchers used standardized questionnaires to garner the women’s reproductive histories.

A matched control group of 2,175 participants who did not have a history of CRC was randomly selected from population registries. All analyses were adjusted for known CRC risk factors, such as age; body mass index; education level; family history; having previously undergone large-bowel endoscopy; diabetes; and smoking status.

The researchers found that each pregnancy was associated with a small but significant 9% reduction in CRC risk (odds ratio, 0.91), specifically in the proximal colon (OR, 0.86).

Overall, breastfeeding for a year or longer was associated with a significantly lower CRC risk, compared with never breastfeeding (OR, 0.74), but the results were only significant for the proximal colon (OR, 0.58).

Oral contraceptive use for 9 years or longer was associated with a lower CRC risk (OR, 0.75) but was only significant for the distal colon (OR, 0.63). Hormone replacement therapy was associated with a lower risk of CRC irrespective of tumor location (OR, 0.76). And using both was linked to a 42% CRC risk reduction (OR, 0.58).

Although age at menarche was not associated with CRC risk, menopause at age 50 or older was associated with a significant 17% lower risk of CRC.

In an email interview, lead author Tobias Niedermaier, PhD, expressed surprise at two of the findings. The first was the small association between pregnancies and CRC risk, “despite the strong increase in estrogen levels during pregnancy,” he said. He speculated that pregnancy-related increases in insulin levels may have “largely offset the protection effects of estrogen exposure during pregnancy.”

The second surprise was that the age at menarche did not have a bearing on CRC risk, which could be because “exposure to estrogen levels in younger ages [is] less relevant with respect to CRC risk, because CRC typically develops at comparably old age.”

John Marshall, MD, who was not involved in the research, commented that such studies “put a lot of pressure on people to perform in a certain way to modify their personal risk of something.” However, “we would not recommend people alter their life choices for reproduction for this,” said Dr. Marshall, chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Dr. Niedermaier agreed that “while this knowledge will certainly not change a woman’s decision on family planning,” he noted that the findings “could influence current CRC screening strategies, for example, by risk-adapted screening intervals [and] start and stop ages of screening.”

Dr. Niedermaier and colleagues’ work was funded by the German Research Council, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the Interdisciplinary Research Program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases. Dr. Niedermaier has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Marshall writes a column that appears regularly on Medscape: Marshall on Oncology. He has served as speaker or member of a speakers’ bureau for Genentech, Amgen, Bayer, Celgene Corporation, and Caris Life Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Estrogen exposure helps protect against colorectal cancer (CRC), and in some instances, the protection is site specific, a new analysis finds.

In a 17-year study involving almost 5,000 women, researchers from Germany found that hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and menopause at age 50 or older were all significantly associated with reductions in CRC risk.

Interestingly, the reduced risk of CRC observed for pregnancy and breastfeeding only applied to proximal colon cancer, while the association with oral contraceptive use was confined to the distal colon and rectum.

The results were published online in JNCI Cancer Spectrum.

CRC is the second most common cause of cancer death. It is responsible for more than one million deaths globally, according to the latest figures from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration.

And sex seems to make a difference. The Global Burden analysis, echoing previous data, found that CRC is less common among women and that fewer women die from the disease.

Little, however, is known about the mechanisms of estrogen signaling in CRC or the impact of reproductive factors on CRC, despite a large amount of literature linking CRC risk to exogenous estrogens, such as hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives.

In the current analysis, the team recruited 2,650 patients with CRC from 20 German cancer centers between 2003 and 2020. Researchers used standardized questionnaires to garner the women’s reproductive histories.

A matched control group of 2,175 participants who did not have a history of CRC was randomly selected from population registries. All analyses were adjusted for known CRC risk factors, such as age; body mass index; education level; family history; having previously undergone large-bowel endoscopy; diabetes; and smoking status.

The researchers found that each pregnancy was associated with a small but significant 9% reduction in CRC risk (odds ratio, 0.91), specifically in the proximal colon (OR, 0.86).

Overall, breastfeeding for a year or longer was associated with a significantly lower CRC risk, compared with never breastfeeding (OR, 0.74), but the results were only significant for the proximal colon (OR, 0.58).

Oral contraceptive use for 9 years or longer was associated with a lower CRC risk (OR, 0.75) but was only significant for the distal colon (OR, 0.63). Hormone replacement therapy was associated with a lower risk of CRC irrespective of tumor location (OR, 0.76). And using both was linked to a 42% CRC risk reduction (OR, 0.58).

Although age at menarche was not associated with CRC risk, menopause at age 50 or older was associated with a significant 17% lower risk of CRC.

In an email interview, lead author Tobias Niedermaier, PhD, expressed surprise at two of the findings. The first was the small association between pregnancies and CRC risk, “despite the strong increase in estrogen levels during pregnancy,” he said. He speculated that pregnancy-related increases in insulin levels may have “largely offset the protection effects of estrogen exposure during pregnancy.”

The second surprise was that the age at menarche did not have a bearing on CRC risk, which could be because “exposure to estrogen levels in younger ages [is] less relevant with respect to CRC risk, because CRC typically develops at comparably old age.”

John Marshall, MD, who was not involved in the research, commented that such studies “put a lot of pressure on people to perform in a certain way to modify their personal risk of something.” However, “we would not recommend people alter their life choices for reproduction for this,” said Dr. Marshall, chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Dr. Niedermaier agreed that “while this knowledge will certainly not change a woman’s decision on family planning,” he noted that the findings “could influence current CRC screening strategies, for example, by risk-adapted screening intervals [and] start and stop ages of screening.”

Dr. Niedermaier and colleagues’ work was funded by the German Research Council, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the Interdisciplinary Research Program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases. Dr. Niedermaier has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Marshall writes a column that appears regularly on Medscape: Marshall on Oncology. He has served as speaker or member of a speakers’ bureau for Genentech, Amgen, Bayer, Celgene Corporation, and Caris Life Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Estrogen exposure helps protect against colorectal cancer (CRC), and in some instances, the protection is site specific, a new analysis finds.

In a 17-year study involving almost 5,000 women, researchers from Germany found that hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and menopause at age 50 or older were all significantly associated with reductions in CRC risk.

Interestingly, the reduced risk of CRC observed for pregnancy and breastfeeding only applied to proximal colon cancer, while the association with oral contraceptive use was confined to the distal colon and rectum.

The results were published online in JNCI Cancer Spectrum.

CRC is the second most common cause of cancer death. It is responsible for more than one million deaths globally, according to the latest figures from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration.

And sex seems to make a difference. The Global Burden analysis, echoing previous data, found that CRC is less common among women and that fewer women die from the disease.

Little, however, is known about the mechanisms of estrogen signaling in CRC or the impact of reproductive factors on CRC, despite a large amount of literature linking CRC risk to exogenous estrogens, such as hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives.

In the current analysis, the team recruited 2,650 patients with CRC from 20 German cancer centers between 2003 and 2020. Researchers used standardized questionnaires to garner the women’s reproductive histories.

A matched control group of 2,175 participants who did not have a history of CRC was randomly selected from population registries. All analyses were adjusted for known CRC risk factors, such as age; body mass index; education level; family history; having previously undergone large-bowel endoscopy; diabetes; and smoking status.

The researchers found that each pregnancy was associated with a small but significant 9% reduction in CRC risk (odds ratio, 0.91), specifically in the proximal colon (OR, 0.86).

Overall, breastfeeding for a year or longer was associated with a significantly lower CRC risk, compared with never breastfeeding (OR, 0.74), but the results were only significant for the proximal colon (OR, 0.58).

Oral contraceptive use for 9 years or longer was associated with a lower CRC risk (OR, 0.75) but was only significant for the distal colon (OR, 0.63). Hormone replacement therapy was associated with a lower risk of CRC irrespective of tumor location (OR, 0.76). And using both was linked to a 42% CRC risk reduction (OR, 0.58).

Although age at menarche was not associated with CRC risk, menopause at age 50 or older was associated with a significant 17% lower risk of CRC.

In an email interview, lead author Tobias Niedermaier, PhD, expressed surprise at two of the findings. The first was the small association between pregnancies and CRC risk, “despite the strong increase in estrogen levels during pregnancy,” he said. He speculated that pregnancy-related increases in insulin levels may have “largely offset the protection effects of estrogen exposure during pregnancy.”

The second surprise was that the age at menarche did not have a bearing on CRC risk, which could be because “exposure to estrogen levels in younger ages [is] less relevant with respect to CRC risk, because CRC typically develops at comparably old age.”

John Marshall, MD, who was not involved in the research, commented that such studies “put a lot of pressure on people to perform in a certain way to modify their personal risk of something.” However, “we would not recommend people alter their life choices for reproduction for this,” said Dr. Marshall, chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Dr. Niedermaier agreed that “while this knowledge will certainly not change a woman’s decision on family planning,” he noted that the findings “could influence current CRC screening strategies, for example, by risk-adapted screening intervals [and] start and stop ages of screening.”

Dr. Niedermaier and colleagues’ work was funded by the German Research Council, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the Interdisciplinary Research Program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases. Dr. Niedermaier has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Marshall writes a column that appears regularly on Medscape: Marshall on Oncology. He has served as speaker or member of a speakers’ bureau for Genentech, Amgen, Bayer, Celgene Corporation, and Caris Life Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Excess weight over lifetime hikes risk for colorectal cancer

Excess weight over a lifetime may play a greater role in a person’s risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) than previously thought, according to new research.

In their paper published online March 17 in JAMA Oncology, the authors liken the cumulative effects of a lifetime with overweight or obesity to the increased risk of cancer the more people smoke over time.

This population-based, case-control study was led by Xiangwei Li, MSc, of the division of clinical epidemiology and aging research at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg.

It looked at height and self-reported weight documented in 10-year increments starting at age 20 years up to the current age for 5,635 people with CRC compared with 4,515 people in a control group.

Odds for colorectal cancer increased substantially over the decades when people carried the excess weight long term compared with participants who remained within the normal weight range during the period.

Coauthor Hermann Brenner, MD, MPH, a colleague in Li’s division at the German Cancer Research Center, said in an interview that a key message in the research is that “overweight and obesity are likely to increase the risk of colorectal cancer more strongly than suggested by previous studies that typically had considered body weight only at a single point of time.”

The researchers used a measure of weighted number of years lived with overweight or obesity (WYOs) determined by multiplying excess body mass index by number of years the person carried the excess weight.

They found a link between WYOs and CRC risk, with adjusted odds ratios (ORs) increasing from 1.25 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44) to 2.54 (95% CI, 2.24-2.89) from the first to the fourth quartile of WYOs, compared with people who stayed within normal weight parameters.

The odds went up substantially the longer the time carrying the excess weight.

“Each SD increment in WYOs was associated with an increase of CRC risk by 55% (adjusted OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.46-1.64),” the authors wrote. “This OR was higher than the OR per SD increase of excess body mass index at any single point of time, which ranged from 1.04 (95% CI, 0.93-1.16) to 1.27 (95% CI 1.16-1.39).”

Dr. Brenner said that although this study focused on colorectal cancer, “the same is likely to apply for other cancers and other chronic diseases.”

Prevention of overweight and obesity to reduce burden of cancer and other chronic diseases “should become a public health priority,” he said.

Preventing overweight in childhood is important

Overweight and obesity increasingly are starting in childhood, he noted, and may be a lifelong burden.

Therefore, “efforts to prevent their development in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood are particularly important,” Dr. Brenner said.

The average age of the patients was 68 years in both the CRC and control groups. There were more men than women in both groups: 59.7% were men in the CRC group and 61.1% were men in the control group.

“Our proposed concept of WYOs is comparable to the concept of pack-years in that WYOs can be considered a weighted measure of years lived with the exposure, with weights reflecting the intensity of exposure,” the authors wrote.

Study helps confirm what is becoming more clear to researchers

Kimmie Ng, MD, MPH, a professor at Harvard Medical School and oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston, said in an interview that the study helps confirm what is becoming more clear to researchers.

“We do think that exposures over the life course are the ones that will be most strongly contributing to a risk of colorectal cancer as an adult,” she said. “With obesity, what we think is happening is that it’s setting up this milieu of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance and we know those two factors can lead to higher rates of colorectal cancer development and increased tumor growth.”

She said the ideal, but impractical, way to do the study would be to follow healthy people from childhood and document their weight over a lifetime. In this case-control study, people were asked to recall their weight at different time periods, which is a limitation and could lead to recall bias.

But the study is important, Dr. Ng said, and it adds convincing evidence that addressing the link between excess weight and CRC and chronic diseases should be a public health priority. “With the recent rise in young-onset colorectal cancer since the 1990s there has been a lot of interest in looking at whether obesity is a major contributor to that rising trend,” Dr. Ng noted. “If obesity is truly linked to colorectal cancer, these rising rates of obesity are very worrisome for potentially leading to more colorectal cancers in young adulthood and beyond.“

The study authors and Dr. Ng report no relevant financial relationships.

The new research was funded by the German Research Council, the Interdisciplinary Research Program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases, Germany, and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Excess weight over a lifetime may play a greater role in a person’s risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) than previously thought, according to new research.

In their paper published online March 17 in JAMA Oncology, the authors liken the cumulative effects of a lifetime with overweight or obesity to the increased risk of cancer the more people smoke over time.

This population-based, case-control study was led by Xiangwei Li, MSc, of the division of clinical epidemiology and aging research at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg.

It looked at height and self-reported weight documented in 10-year increments starting at age 20 years up to the current age for 5,635 people with CRC compared with 4,515 people in a control group.

Odds for colorectal cancer increased substantially over the decades when people carried the excess weight long term compared with participants who remained within the normal weight range during the period.

Coauthor Hermann Brenner, MD, MPH, a colleague in Li’s division at the German Cancer Research Center, said in an interview that a key message in the research is that “overweight and obesity are likely to increase the risk of colorectal cancer more strongly than suggested by previous studies that typically had considered body weight only at a single point of time.”

The researchers used a measure of weighted number of years lived with overweight or obesity (WYOs) determined by multiplying excess body mass index by number of years the person carried the excess weight.

They found a link between WYOs and CRC risk, with adjusted odds ratios (ORs) increasing from 1.25 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44) to 2.54 (95% CI, 2.24-2.89) from the first to the fourth quartile of WYOs, compared with people who stayed within normal weight parameters.

The odds went up substantially the longer the time carrying the excess weight.

“Each SD increment in WYOs was associated with an increase of CRC risk by 55% (adjusted OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.46-1.64),” the authors wrote. “This OR was higher than the OR per SD increase of excess body mass index at any single point of time, which ranged from 1.04 (95% CI, 0.93-1.16) to 1.27 (95% CI 1.16-1.39).”

Dr. Brenner said that although this study focused on colorectal cancer, “the same is likely to apply for other cancers and other chronic diseases.”

Prevention of overweight and obesity to reduce burden of cancer and other chronic diseases “should become a public health priority,” he said.

Preventing overweight in childhood is important

Overweight and obesity increasingly are starting in childhood, he noted, and may be a lifelong burden.

Therefore, “efforts to prevent their development in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood are particularly important,” Dr. Brenner said.

The average age of the patients was 68 years in both the CRC and control groups. There were more men than women in both groups: 59.7% were men in the CRC group and 61.1% were men in the control group.

“Our proposed concept of WYOs is comparable to the concept of pack-years in that WYOs can be considered a weighted measure of years lived with the exposure, with weights reflecting the intensity of exposure,” the authors wrote.

Study helps confirm what is becoming more clear to researchers

Kimmie Ng, MD, MPH, a professor at Harvard Medical School and oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston, said in an interview that the study helps confirm what is becoming more clear to researchers.

“We do think that exposures over the life course are the ones that will be most strongly contributing to a risk of colorectal cancer as an adult,” she said. “With obesity, what we think is happening is that it’s setting up this milieu of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance and we know those two factors can lead to higher rates of colorectal cancer development and increased tumor growth.”

She said the ideal, but impractical, way to do the study would be to follow healthy people from childhood and document their weight over a lifetime. In this case-control study, people were asked to recall their weight at different time periods, which is a limitation and could lead to recall bias.

But the study is important, Dr. Ng said, and it adds convincing evidence that addressing the link between excess weight and CRC and chronic diseases should be a public health priority. “With the recent rise in young-onset colorectal cancer since the 1990s there has been a lot of interest in looking at whether obesity is a major contributor to that rising trend,” Dr. Ng noted. “If obesity is truly linked to colorectal cancer, these rising rates of obesity are very worrisome for potentially leading to more colorectal cancers in young adulthood and beyond.“

The study authors and Dr. Ng report no relevant financial relationships.

The new research was funded by the German Research Council, the Interdisciplinary Research Program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases, Germany, and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Excess weight over a lifetime may play a greater role in a person’s risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) than previously thought, according to new research.

In their paper published online March 17 in JAMA Oncology, the authors liken the cumulative effects of a lifetime with overweight or obesity to the increased risk of cancer the more people smoke over time.

This population-based, case-control study was led by Xiangwei Li, MSc, of the division of clinical epidemiology and aging research at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg.

It looked at height and self-reported weight documented in 10-year increments starting at age 20 years up to the current age for 5,635 people with CRC compared with 4,515 people in a control group.

Odds for colorectal cancer increased substantially over the decades when people carried the excess weight long term compared with participants who remained within the normal weight range during the period.

Coauthor Hermann Brenner, MD, MPH, a colleague in Li’s division at the German Cancer Research Center, said in an interview that a key message in the research is that “overweight and obesity are likely to increase the risk of colorectal cancer more strongly than suggested by previous studies that typically had considered body weight only at a single point of time.”

The researchers used a measure of weighted number of years lived with overweight or obesity (WYOs) determined by multiplying excess body mass index by number of years the person carried the excess weight.

They found a link between WYOs and CRC risk, with adjusted odds ratios (ORs) increasing from 1.25 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44) to 2.54 (95% CI, 2.24-2.89) from the first to the fourth quartile of WYOs, compared with people who stayed within normal weight parameters.

The odds went up substantially the longer the time carrying the excess weight.

“Each SD increment in WYOs was associated with an increase of CRC risk by 55% (adjusted OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.46-1.64),” the authors wrote. “This OR was higher than the OR per SD increase of excess body mass index at any single point of time, which ranged from 1.04 (95% CI, 0.93-1.16) to 1.27 (95% CI 1.16-1.39).”

Dr. Brenner said that although this study focused on colorectal cancer, “the same is likely to apply for other cancers and other chronic diseases.”

Prevention of overweight and obesity to reduce burden of cancer and other chronic diseases “should become a public health priority,” he said.

Preventing overweight in childhood is important

Overweight and obesity increasingly are starting in childhood, he noted, and may be a lifelong burden.

Therefore, “efforts to prevent their development in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood are particularly important,” Dr. Brenner said.

The average age of the patients was 68 years in both the CRC and control groups. There were more men than women in both groups: 59.7% were men in the CRC group and 61.1% were men in the control group.

“Our proposed concept of WYOs is comparable to the concept of pack-years in that WYOs can be considered a weighted measure of years lived with the exposure, with weights reflecting the intensity of exposure,” the authors wrote.

Study helps confirm what is becoming more clear to researchers

Kimmie Ng, MD, MPH, a professor at Harvard Medical School and oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston, said in an interview that the study helps confirm what is becoming more clear to researchers.

“We do think that exposures over the life course are the ones that will be most strongly contributing to a risk of colorectal cancer as an adult,” she said. “With obesity, what we think is happening is that it’s setting up this milieu of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance and we know those two factors can lead to higher rates of colorectal cancer development and increased tumor growth.”

She said the ideal, but impractical, way to do the study would be to follow healthy people from childhood and document their weight over a lifetime. In this case-control study, people were asked to recall their weight at different time periods, which is a limitation and could lead to recall bias.

But the study is important, Dr. Ng said, and it adds convincing evidence that addressing the link between excess weight and CRC and chronic diseases should be a public health priority. “With the recent rise in young-onset colorectal cancer since the 1990s there has been a lot of interest in looking at whether obesity is a major contributor to that rising trend,” Dr. Ng noted. “If obesity is truly linked to colorectal cancer, these rising rates of obesity are very worrisome for potentially leading to more colorectal cancers in young adulthood and beyond.“

The study authors and Dr. Ng report no relevant financial relationships.

The new research was funded by the German Research Council, the Interdisciplinary Research Program of the National Center for Tumor Diseases, Germany, and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Pediatric IBD increases cancer risk later in life

Children who are diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are more than twice as likely to develop cancer, especially gastrointestinal cancer, later in life compared with the general pediatric population, a new meta-analysis suggests.

Although the overall incidence rate of cancer in this population is low, “we found a 2.4-fold increase in the relative rate of cancer among patients with pediatric-onset IBD compared with the general pediatric population, primarily associated with an increased rate of gastrointestinal cancers,” wrote senior author Tine Jess, MD, DMSci, Aalborg University, Copenhagen, and colleagues.

The study was published online March 1 in JAMA Network Open.

Previous research indicates that IBD is associated with an increased risk for colon, small bowel, and other types of cancer in adults, but the risk among children with IBD is not well understood.

In the current analysis, Dr. Jess and colleagues examined five population-based studies from North America and Europe, which included more than 19,800 participants with pediatric-onset IBD. Of these participants, 715 were later diagnosed with cancer.

Overall, the risk for cancer among individuals with pediatric-onset IBD was 2.4-fold higher than that of their peers without IBD, but those rates varied by IBD subtype. Those with Crohn’s disease, for instance, were about two times more likely to develop cancer, while those with ulcerative colitis were 2.6 times more likely to develop cancer later.

Two studies included in the meta-analysis broke down results by sex and found that the risk for cancer was higher among male versus female patients (pooled relative rates [pRR], 3.23 in men and 2.45 in women).

These two studies also calculated the risk for cancer by exposure to thiopurines. Patients receiving these immunosuppressive drugs had an increased relative rate of cancer (pRR, 2.09). Although numerically higher, this rate was not statistically higher compared with patients not exposed to the drugs (pRR, 1.82).

When looking at risk by cancer site, the authors consistently observed the highest relative rates for gastrointestinal cancers. Specifically, the investigators calculated a 55-fold increased risk for liver cancer (pRR, 55.4), followed by a 20-fold increased risk for colorectal cancer (pRR, 20.2), and a 16-fold increased risk for small bowel cancer (pRR, 16.2).

Despite such high estimates for gastrointestinal cancers, “this risk corresponds to a mean incidence rate of 0.3 cases of liver cancer, 0.6 cases of colorectal cancer, and 0.1 cases of small bowel cancer per 1,000 person-years in this population,” the authors noted.

In other words, “the overall incidence rate of cancer in this population is low,” at less than 3.3 cases per 1,000 person-years, the authors concluded.

Relative rates of extraintestinal cancers were even lower, with the highest risks for nonmelanoma skin cancer (pRR, 3.62), lymphoid cancer (pRR, 3.10), and melanoma (pRR, 2.05).

The authors suggest that identifying variables that might reduce cancer risk in pediatric patients who develop IBD could better shape management and prevention strategies.

CRC screening guidelines already recommend that children undergo a colonoscopy 6-8 years after being diagnosed with colitis extending beyond the rectum. Annual colonoscopy is also recommended for patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis from the time of diagnosis and annual screening for skin cancer is recommended for all patients with IBD.

The investigators further suggest that because ongoing inflammation is an important risk factor for cancer, early and adequate control of inflammation could be critical in the prevention of long-term complications.

The study was supported by a grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Dr. Jess and coauthors Rahma Elmahdi, MD, Camilla Lemser, and Kristine Allin, MD, reported receiving grants from the Danish National Research Foundation National Center of Excellence during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Manasi Agrawal, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children who are diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are more than twice as likely to develop cancer, especially gastrointestinal cancer, later in life compared with the general pediatric population, a new meta-analysis suggests.

Although the overall incidence rate of cancer in this population is low, “we found a 2.4-fold increase in the relative rate of cancer among patients with pediatric-onset IBD compared with the general pediatric population, primarily associated with an increased rate of gastrointestinal cancers,” wrote senior author Tine Jess, MD, DMSci, Aalborg University, Copenhagen, and colleagues.

The study was published online March 1 in JAMA Network Open.

Previous research indicates that IBD is associated with an increased risk for colon, small bowel, and other types of cancer in adults, but the risk among children with IBD is not well understood.

In the current analysis, Dr. Jess and colleagues examined five population-based studies from North America and Europe, which included more than 19,800 participants with pediatric-onset IBD. Of these participants, 715 were later diagnosed with cancer.

Overall, the risk for cancer among individuals with pediatric-onset IBD was 2.4-fold higher than that of their peers without IBD, but those rates varied by IBD subtype. Those with Crohn’s disease, for instance, were about two times more likely to develop cancer, while those with ulcerative colitis were 2.6 times more likely to develop cancer later.

Two studies included in the meta-analysis broke down results by sex and found that the risk for cancer was higher among male versus female patients (pooled relative rates [pRR], 3.23 in men and 2.45 in women).

These two studies also calculated the risk for cancer by exposure to thiopurines. Patients receiving these immunosuppressive drugs had an increased relative rate of cancer (pRR, 2.09). Although numerically higher, this rate was not statistically higher compared with patients not exposed to the drugs (pRR, 1.82).

When looking at risk by cancer site, the authors consistently observed the highest relative rates for gastrointestinal cancers. Specifically, the investigators calculated a 55-fold increased risk for liver cancer (pRR, 55.4), followed by a 20-fold increased risk for colorectal cancer (pRR, 20.2), and a 16-fold increased risk for small bowel cancer (pRR, 16.2).

Despite such high estimates for gastrointestinal cancers, “this risk corresponds to a mean incidence rate of 0.3 cases of liver cancer, 0.6 cases of colorectal cancer, and 0.1 cases of small bowel cancer per 1,000 person-years in this population,” the authors noted.

In other words, “the overall incidence rate of cancer in this population is low,” at less than 3.3 cases per 1,000 person-years, the authors concluded.

Relative rates of extraintestinal cancers were even lower, with the highest risks for nonmelanoma skin cancer (pRR, 3.62), lymphoid cancer (pRR, 3.10), and melanoma (pRR, 2.05).

The authors suggest that identifying variables that might reduce cancer risk in pediatric patients who develop IBD could better shape management and prevention strategies.

CRC screening guidelines already recommend that children undergo a colonoscopy 6-8 years after being diagnosed with colitis extending beyond the rectum. Annual colonoscopy is also recommended for patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis from the time of diagnosis and annual screening for skin cancer is recommended for all patients with IBD.

The investigators further suggest that because ongoing inflammation is an important risk factor for cancer, early and adequate control of inflammation could be critical in the prevention of long-term complications.

The study was supported by a grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Dr. Jess and coauthors Rahma Elmahdi, MD, Camilla Lemser, and Kristine Allin, MD, reported receiving grants from the Danish National Research Foundation National Center of Excellence during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Manasi Agrawal, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children who are diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are more than twice as likely to develop cancer, especially gastrointestinal cancer, later in life compared with the general pediatric population, a new meta-analysis suggests.

Although the overall incidence rate of cancer in this population is low, “we found a 2.4-fold increase in the relative rate of cancer among patients with pediatric-onset IBD compared with the general pediatric population, primarily associated with an increased rate of gastrointestinal cancers,” wrote senior author Tine Jess, MD, DMSci, Aalborg University, Copenhagen, and colleagues.

The study was published online March 1 in JAMA Network Open.

Previous research indicates that IBD is associated with an increased risk for colon, small bowel, and other types of cancer in adults, but the risk among children with IBD is not well understood.

In the current analysis, Dr. Jess and colleagues examined five population-based studies from North America and Europe, which included more than 19,800 participants with pediatric-onset IBD. Of these participants, 715 were later diagnosed with cancer.

Overall, the risk for cancer among individuals with pediatric-onset IBD was 2.4-fold higher than that of their peers without IBD, but those rates varied by IBD subtype. Those with Crohn’s disease, for instance, were about two times more likely to develop cancer, while those with ulcerative colitis were 2.6 times more likely to develop cancer later.

Two studies included in the meta-analysis broke down results by sex and found that the risk for cancer was higher among male versus female patients (pooled relative rates [pRR], 3.23 in men and 2.45 in women).

These two studies also calculated the risk for cancer by exposure to thiopurines. Patients receiving these immunosuppressive drugs had an increased relative rate of cancer (pRR, 2.09). Although numerically higher, this rate was not statistically higher compared with patients not exposed to the drugs (pRR, 1.82).

When looking at risk by cancer site, the authors consistently observed the highest relative rates for gastrointestinal cancers. Specifically, the investigators calculated a 55-fold increased risk for liver cancer (pRR, 55.4), followed by a 20-fold increased risk for colorectal cancer (pRR, 20.2), and a 16-fold increased risk for small bowel cancer (pRR, 16.2).

Despite such high estimates for gastrointestinal cancers, “this risk corresponds to a mean incidence rate of 0.3 cases of liver cancer, 0.6 cases of colorectal cancer, and 0.1 cases of small bowel cancer per 1,000 person-years in this population,” the authors noted.

In other words, “the overall incidence rate of cancer in this population is low,” at less than 3.3 cases per 1,000 person-years, the authors concluded.

Relative rates of extraintestinal cancers were even lower, with the highest risks for nonmelanoma skin cancer (pRR, 3.62), lymphoid cancer (pRR, 3.10), and melanoma (pRR, 2.05).

The authors suggest that identifying variables that might reduce cancer risk in pediatric patients who develop IBD could better shape management and prevention strategies.

CRC screening guidelines already recommend that children undergo a colonoscopy 6-8 years after being diagnosed with colitis extending beyond the rectum. Annual colonoscopy is also recommended for patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis from the time of diagnosis and annual screening for skin cancer is recommended for all patients with IBD.

The investigators further suggest that because ongoing inflammation is an important risk factor for cancer, early and adequate control of inflammation could be critical in the prevention of long-term complications.

The study was supported by a grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Dr. Jess and coauthors Rahma Elmahdi, MD, Camilla Lemser, and Kristine Allin, MD, reported receiving grants from the Danish National Research Foundation National Center of Excellence during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Manasi Agrawal, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK

Colorectal cancer rates rising in people aged 50-54 years

mirroring the well-documented increases in early-onset CRC in persons younger than 50 years.

“It’s likely that the factors contributing to CRC at age 50–54 years are the same factors that contribute to early-onset CRC, which has increased in parallel,” Caitlin Murphy, PhD, MPH, with the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said in an interview.

“Many studies published in just the last year show that the well-known risk factors of CRC in older adults, such as obesity or sedentary lifestyle, are risk factors of CRC in younger adults. Growing evidence also suggests that early life exposures, or exposures in childhood, infancy, or even in the womb, play an important role,” Dr. Murphy said.

The study was published online October 28 in Gastroenterology .

Dr. Murphy and colleagues examined trends in age-specific CRC incidence rates for individuals aged 45–49, 50–54, and 55–59 years using the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

During the period 1992–2018, there were a total of 101,609 cases of CRC among adults aged 45–59 years.

Further analysis showed that the CRC incidence rates rose from 23.4 to 34.0 per 100,000 among people aged 45–49 years and from 46.4 to 63.8 per 100,000 among those aged 50–54 years.

Conversely, incidence rates decreased among individuals aged 55–59 years, from 81.7 to 63.7 per 100,000 persons.

“Because of this opposing trend, or decreasing rates for age 55–59 years and increasing rates for age 50–54 years, incidence rates for the two age groups were nearly identical in 2016–18,” the researchers write.

They also found a “clear pattern” of increasing CRC incidence among adults in their early 50s, supporting the hypothesis that incidence rates increase at older ages as higher-risk generations mature, the researchers note.

These data send a clear message, Dr. Murphy told this news organization.

“Don’t delay colorectal cancer screening. Encourage on-time screening by discussing screening with patients before they reach the recommended age to initiate screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force now recommends initiating average-risk screening at age 45 years,” Dr. Murphy said.

Concerning but not surprising

Rebecca Siegel, MPH, scientific director of Surveillance Research at the American Cancer Society, in Atlanta, who wasn’t involved in the study, said the results are “not surprising” and mirror the results of a 2017 study that showed that the incidence of CRC was increasing among individuals aged 50–54 years, as reported.

What’s “concerning,” Ms. Siegel said, is that people in this age group “have been recommended to be screened for CRC for decades. Hopefully, because the age to begin screening has been lowered from 50 to 45 years, this uptick will eventually flatten.”

David Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, in Norfolk, Va., who also wasn’t involved in the study, said the increasing incidence is “concerning in this younger population, and similar to what is seen recently for the 45- to 49-year-old population.

“Recent data have linked dietary influences in the early development of precancerous colon polyps and colon cancer. The increased ingestion of processed foods and sugary beverages, most of which contain high fructose corn syrup, is very likely involved in the pathogenesis to explain these striking epidemiologic shifts,” Dr. Johnson said in an interview.

“These concerns will likely be compounded by the COVID-related adverse effects on people [in terms of] appropriate, timely colorectal cancer screening,” Dr. Johnson added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Murphy has consulted for Freenome. Ms. Siegel and Dr. Johnson have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

mirroring the well-documented increases in early-onset CRC in persons younger than 50 years.

“It’s likely that the factors contributing to CRC at age 50–54 years are the same factors that contribute to early-onset CRC, which has increased in parallel,” Caitlin Murphy, PhD, MPH, with the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said in an interview.

“Many studies published in just the last year show that the well-known risk factors of CRC in older adults, such as obesity or sedentary lifestyle, are risk factors of CRC in younger adults. Growing evidence also suggests that early life exposures, or exposures in childhood, infancy, or even in the womb, play an important role,” Dr. Murphy said.

The study was published online October 28 in Gastroenterology .

Dr. Murphy and colleagues examined trends in age-specific CRC incidence rates for individuals aged 45–49, 50–54, and 55–59 years using the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

During the period 1992–2018, there were a total of 101,609 cases of CRC among adults aged 45–59 years.

Further analysis showed that the CRC incidence rates rose from 23.4 to 34.0 per 100,000 among people aged 45–49 years and from 46.4 to 63.8 per 100,000 among those aged 50–54 years.

Conversely, incidence rates decreased among individuals aged 55–59 years, from 81.7 to 63.7 per 100,000 persons.

“Because of this opposing trend, or decreasing rates for age 55–59 years and increasing rates for age 50–54 years, incidence rates for the two age groups were nearly identical in 2016–18,” the researchers write.

They also found a “clear pattern” of increasing CRC incidence among adults in their early 50s, supporting the hypothesis that incidence rates increase at older ages as higher-risk generations mature, the researchers note.

These data send a clear message, Dr. Murphy told this news organization.

“Don’t delay colorectal cancer screening. Encourage on-time screening by discussing screening with patients before they reach the recommended age to initiate screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force now recommends initiating average-risk screening at age 45 years,” Dr. Murphy said.

Concerning but not surprising

Rebecca Siegel, MPH, scientific director of Surveillance Research at the American Cancer Society, in Atlanta, who wasn’t involved in the study, said the results are “not surprising” and mirror the results of a 2017 study that showed that the incidence of CRC was increasing among individuals aged 50–54 years, as reported.

What’s “concerning,” Ms. Siegel said, is that people in this age group “have been recommended to be screened for CRC for decades. Hopefully, because the age to begin screening has been lowered from 50 to 45 years, this uptick will eventually flatten.”

David Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, in Norfolk, Va., who also wasn’t involved in the study, said the increasing incidence is “concerning in this younger population, and similar to what is seen recently for the 45- to 49-year-old population.

“Recent data have linked dietary influences in the early development of precancerous colon polyps and colon cancer. The increased ingestion of processed foods and sugary beverages, most of which contain high fructose corn syrup, is very likely involved in the pathogenesis to explain these striking epidemiologic shifts,” Dr. Johnson said in an interview.

“These concerns will likely be compounded by the COVID-related adverse effects on people [in terms of] appropriate, timely colorectal cancer screening,” Dr. Johnson added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Murphy has consulted for Freenome. Ms. Siegel and Dr. Johnson have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

mirroring the well-documented increases in early-onset CRC in persons younger than 50 years.

“It’s likely that the factors contributing to CRC at age 50–54 years are the same factors that contribute to early-onset CRC, which has increased in parallel,” Caitlin Murphy, PhD, MPH, with the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said in an interview.

“Many studies published in just the last year show that the well-known risk factors of CRC in older adults, such as obesity or sedentary lifestyle, are risk factors of CRC in younger adults. Growing evidence also suggests that early life exposures, or exposures in childhood, infancy, or even in the womb, play an important role,” Dr. Murphy said.

The study was published online October 28 in Gastroenterology .

Dr. Murphy and colleagues examined trends in age-specific CRC incidence rates for individuals aged 45–49, 50–54, and 55–59 years using the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

During the period 1992–2018, there were a total of 101,609 cases of CRC among adults aged 45–59 years.

Further analysis showed that the CRC incidence rates rose from 23.4 to 34.0 per 100,000 among people aged 45–49 years and from 46.4 to 63.8 per 100,000 among those aged 50–54 years.

Conversely, incidence rates decreased among individuals aged 55–59 years, from 81.7 to 63.7 per 100,000 persons.

“Because of this opposing trend, or decreasing rates for age 55–59 years and increasing rates for age 50–54 years, incidence rates for the two age groups were nearly identical in 2016–18,” the researchers write.

They also found a “clear pattern” of increasing CRC incidence among adults in their early 50s, supporting the hypothesis that incidence rates increase at older ages as higher-risk generations mature, the researchers note.

These data send a clear message, Dr. Murphy told this news organization.

“Don’t delay colorectal cancer screening. Encourage on-time screening by discussing screening with patients before they reach the recommended age to initiate screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force now recommends initiating average-risk screening at age 45 years,” Dr. Murphy said.

Concerning but not surprising

Rebecca Siegel, MPH, scientific director of Surveillance Research at the American Cancer Society, in Atlanta, who wasn’t involved in the study, said the results are “not surprising” and mirror the results of a 2017 study that showed that the incidence of CRC was increasing among individuals aged 50–54 years, as reported.

What’s “concerning,” Ms. Siegel said, is that people in this age group “have been recommended to be screened for CRC for decades. Hopefully, because the age to begin screening has been lowered from 50 to 45 years, this uptick will eventually flatten.”

David Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, in Norfolk, Va., who also wasn’t involved in the study, said the increasing incidence is “concerning in this younger population, and similar to what is seen recently for the 45- to 49-year-old population.

“Recent data have linked dietary influences in the early development of precancerous colon polyps and colon cancer. The increased ingestion of processed foods and sugary beverages, most of which contain high fructose corn syrup, is very likely involved in the pathogenesis to explain these striking epidemiologic shifts,” Dr. Johnson said in an interview.

“These concerns will likely be compounded by the COVID-related adverse effects on people [in terms of] appropriate, timely colorectal cancer screening,” Dr. Johnson added.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Murphy has consulted for Freenome. Ms. Siegel and Dr. Johnson have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Few poorly prepped colonoscopies repeated within 1 year

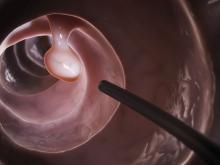

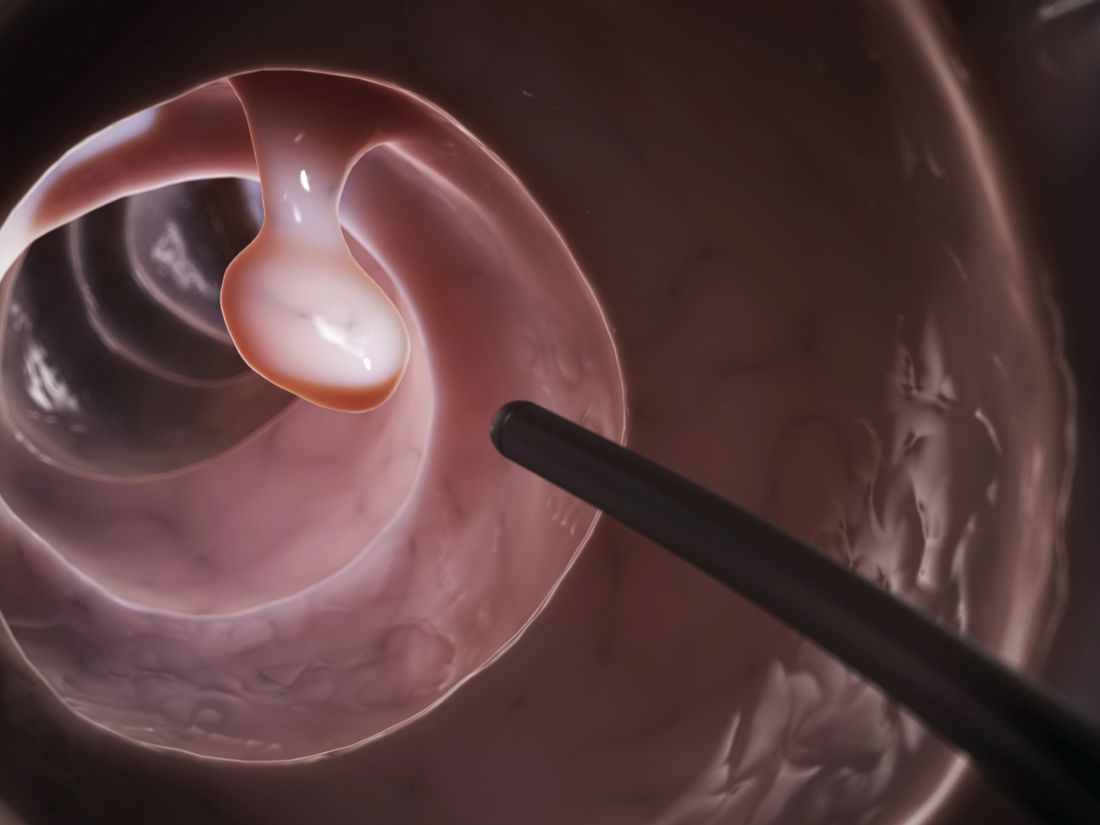

Approximately one-third of colonoscopies with inadequate bowel preparation were repeated within 1 year despite current guidelines, according to data from a new study of more than 260,000 procedures.

Previous studies have shown that poor bowel prep, which occurs in approximately 25% of colonoscopies, can lead to lesion miss rates of as much as 42%-48%, Audrey H. Calderwood, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and colleagues wrote. However, factors affecting recommendations for repeat colonoscopies following poor bowel prep have not been examined.

In the study, published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional retrospective analysis of 260,314 colonoscopies reported to the GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQuIC) from 2011 to 2018. The review included adults aged 50-75 years in whom bowel preparation was deemed inadequate. The GIQuIC database defines adequate bowel preparation as “sufficient to accurately detect polyps greater than 5 mm in size,” the researchers noted. The procedures in this study were performed at 672 sites by 4,001 endoscopists, and the primary outcome was a recommendation for a repeat colonoscopy within 1 year.

In 31.9% of the procedures, the recommended follow-up interval for repeat colonoscopy was within 1 year, and there were no significant differences according to indication for the procedures (32.3% of screening and 31.2% of surveillance). Of these, 54.9% of patients received a follow-up interval of 1 year and 24.7% a follow-up interval within 3 months. Only 2.4% were advised they required no follow-up procedure.

The researchers found that patients with more severe disease had a higher likelihood of receiving a recommendation for follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year – 84% with adenocarcinoma, 51.8% with advanced lesions, and 23.2% with one to two small adenomas.

In the multivariate analysis, there were specific patient factors significantly associated with 1-year follow-up recommendations. The researchers found patients aged 70-75 years were less likely than younger patients (adjusted odds ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-0.98) to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation; men were more likely than women (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06) to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation; and patients with adenocarcinoma findings more likely to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation compared to those with no adenocarcinoma (aOR, 10.43; 95% CI, 7.77-13.98). In addition, they found patients residing in the Northeast and those whose procedure was performed by an endoscopist with an adenoma detection rate of at least25% were more likely to receive recommendations for a repeat colonoscopy within 1 year.

“The recommendation for repeat screening or surveillance colonoscopy within 1 year when the index colonoscopy has an inadequate bowel preparation is currently a quality measure in gastroenterology,” the researchers noted. “Although our study period started in 2011, when we looked at the time period of 2014 to 2018, which is after publication of guidelines of when to repeat colonoscopy after inadequate bowel preparation, there were still low rates of guideline-concordant recommendations.”

These overall low rates, which are consistent with other studies, may be due uncertainty on the part of the endoscopist in determining inadequate bowel prep based on evolving guidelines, the researchers noted. However, the higher frequency of recommendations for repeat procedures within 1 year for patients with advanced disease suggests that endoscopists are taking pathology into account.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of standardized assessment of bowel prep quality, variation in descriptions of bowel cleanliness, and lack of information on the primary factor in follow-up recommendations. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, the inclusion of multiple sites and providers, and the low volume of timely repeat procedures, which has clinical implications in terms of missed lesions, “including potential interval CRC [colorectal cancer],” the researchers said.

Get the word out on describing preps and planning follow-ups

The current study is important because it highlights that, even when endoscopists have a reasonable understanding on how to set follow-up intervals for polyp follow-up, what to do with a patient who comes in poorly prepped is more of a problem, Kim L. Isaacs, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Dr Isaacs said she was not surprised by the study findings. “There are all gradations of inadequate preps that limit visualization in different ways, and there are many ways of recording this on procedure reports. The findings in the current study emphasize several points. The first is that the recommendation of following up an inadequate or poor prep in a year needs to be widely disseminated. The second is that there needs to be more education on standardization on how preps are described. In some poor preps, much of the colon can be seen, and clinicians can identify polyps 5-6 mm, so a 1-year follow-up may not be needed.” This type of research is challenging if the data are not standardized, she added.

Dr. Isaacs agreed with the authors’ description of repeat colonoscopies after poor bowel prep as a quality improvement area given the variability in following current recommendations, which leads into next steps for research.

“Understanding reasons for the recommendations that endoscopists made for follow-up would be the next step in this type of research,” Dr Isaacs noted. “After that, studies on the impact of an educational intervention, followed by repeating the initial assessment.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose; however, lead author Dr. Calderwood disclosed support from the National Cancer Institute, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Cancer Research Fellows Program, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Norris Cotton Cancer Center, and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr Isaacs had no financial conflicts to disclose but has previously served on the editorial board of GI & Hepatology News.

Approximately one-third of colonoscopies with inadequate bowel preparation were repeated within 1 year despite current guidelines, according to data from a new study of more than 260,000 procedures.

Previous studies have shown that poor bowel prep, which occurs in approximately 25% of colonoscopies, can lead to lesion miss rates of as much as 42%-48%, Audrey H. Calderwood, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and colleagues wrote. However, factors affecting recommendations for repeat colonoscopies following poor bowel prep have not been examined.

In the study, published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional retrospective analysis of 260,314 colonoscopies reported to the GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQuIC) from 2011 to 2018. The review included adults aged 50-75 years in whom bowel preparation was deemed inadequate. The GIQuIC database defines adequate bowel preparation as “sufficient to accurately detect polyps greater than 5 mm in size,” the researchers noted. The procedures in this study were performed at 672 sites by 4,001 endoscopists, and the primary outcome was a recommendation for a repeat colonoscopy within 1 year.

In 31.9% of the procedures, the recommended follow-up interval for repeat colonoscopy was within 1 year, and there were no significant differences according to indication for the procedures (32.3% of screening and 31.2% of surveillance). Of these, 54.9% of patients received a follow-up interval of 1 year and 24.7% a follow-up interval within 3 months. Only 2.4% were advised they required no follow-up procedure.

The researchers found that patients with more severe disease had a higher likelihood of receiving a recommendation for follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year – 84% with adenocarcinoma, 51.8% with advanced lesions, and 23.2% with one to two small adenomas.

In the multivariate analysis, there were specific patient factors significantly associated with 1-year follow-up recommendations. The researchers found patients aged 70-75 years were less likely than younger patients (adjusted odds ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-0.98) to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation; men were more likely than women (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06) to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation; and patients with adenocarcinoma findings more likely to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation compared to those with no adenocarcinoma (aOR, 10.43; 95% CI, 7.77-13.98). In addition, they found patients residing in the Northeast and those whose procedure was performed by an endoscopist with an adenoma detection rate of at least25% were more likely to receive recommendations for a repeat colonoscopy within 1 year.

“The recommendation for repeat screening or surveillance colonoscopy within 1 year when the index colonoscopy has an inadequate bowel preparation is currently a quality measure in gastroenterology,” the researchers noted. “Although our study period started in 2011, when we looked at the time period of 2014 to 2018, which is after publication of guidelines of when to repeat colonoscopy after inadequate bowel preparation, there were still low rates of guideline-concordant recommendations.”

These overall low rates, which are consistent with other studies, may be due uncertainty on the part of the endoscopist in determining inadequate bowel prep based on evolving guidelines, the researchers noted. However, the higher frequency of recommendations for repeat procedures within 1 year for patients with advanced disease suggests that endoscopists are taking pathology into account.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of standardized assessment of bowel prep quality, variation in descriptions of bowel cleanliness, and lack of information on the primary factor in follow-up recommendations. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, the inclusion of multiple sites and providers, and the low volume of timely repeat procedures, which has clinical implications in terms of missed lesions, “including potential interval CRC [colorectal cancer],” the researchers said.

Get the word out on describing preps and planning follow-ups

The current study is important because it highlights that, even when endoscopists have a reasonable understanding on how to set follow-up intervals for polyp follow-up, what to do with a patient who comes in poorly prepped is more of a problem, Kim L. Isaacs, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Dr Isaacs said she was not surprised by the study findings. “There are all gradations of inadequate preps that limit visualization in different ways, and there are many ways of recording this on procedure reports. The findings in the current study emphasize several points. The first is that the recommendation of following up an inadequate or poor prep in a year needs to be widely disseminated. The second is that there needs to be more education on standardization on how preps are described. In some poor preps, much of the colon can be seen, and clinicians can identify polyps 5-6 mm, so a 1-year follow-up may not be needed.” This type of research is challenging if the data are not standardized, she added.

Dr. Isaacs agreed with the authors’ description of repeat colonoscopies after poor bowel prep as a quality improvement area given the variability in following current recommendations, which leads into next steps for research.

“Understanding reasons for the recommendations that endoscopists made for follow-up would be the next step in this type of research,” Dr Isaacs noted. “After that, studies on the impact of an educational intervention, followed by repeating the initial assessment.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose; however, lead author Dr. Calderwood disclosed support from the National Cancer Institute, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Cancer Research Fellows Program, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Norris Cotton Cancer Center, and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr Isaacs had no financial conflicts to disclose but has previously served on the editorial board of GI & Hepatology News.

Approximately one-third of colonoscopies with inadequate bowel preparation were repeated within 1 year despite current guidelines, according to data from a new study of more than 260,000 procedures.

Previous studies have shown that poor bowel prep, which occurs in approximately 25% of colonoscopies, can lead to lesion miss rates of as much as 42%-48%, Audrey H. Calderwood, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and colleagues wrote. However, factors affecting recommendations for repeat colonoscopies following poor bowel prep have not been examined.

In the study, published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional retrospective analysis of 260,314 colonoscopies reported to the GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQuIC) from 2011 to 2018. The review included adults aged 50-75 years in whom bowel preparation was deemed inadequate. The GIQuIC database defines adequate bowel preparation as “sufficient to accurately detect polyps greater than 5 mm in size,” the researchers noted. The procedures in this study were performed at 672 sites by 4,001 endoscopists, and the primary outcome was a recommendation for a repeat colonoscopy within 1 year.

In 31.9% of the procedures, the recommended follow-up interval for repeat colonoscopy was within 1 year, and there were no significant differences according to indication for the procedures (32.3% of screening and 31.2% of surveillance). Of these, 54.9% of patients received a follow-up interval of 1 year and 24.7% a follow-up interval within 3 months. Only 2.4% were advised they required no follow-up procedure.

The researchers found that patients with more severe disease had a higher likelihood of receiving a recommendation for follow-up colonoscopy within 1 year – 84% with adenocarcinoma, 51.8% with advanced lesions, and 23.2% with one to two small adenomas.

In the multivariate analysis, there were specific patient factors significantly associated with 1-year follow-up recommendations. The researchers found patients aged 70-75 years were less likely than younger patients (adjusted odds ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-0.98) to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation; men were more likely than women (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06) to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation; and patients with adenocarcinoma findings more likely to receive a 1-year follow-up recommendation compared to those with no adenocarcinoma (aOR, 10.43; 95% CI, 7.77-13.98). In addition, they found patients residing in the Northeast and those whose procedure was performed by an endoscopist with an adenoma detection rate of at least25% were more likely to receive recommendations for a repeat colonoscopy within 1 year.

“The recommendation for repeat screening or surveillance colonoscopy within 1 year when the index colonoscopy has an inadequate bowel preparation is currently a quality measure in gastroenterology,” the researchers noted. “Although our study period started in 2011, when we looked at the time period of 2014 to 2018, which is after publication of guidelines of when to repeat colonoscopy after inadequate bowel preparation, there were still low rates of guideline-concordant recommendations.”

These overall low rates, which are consistent with other studies, may be due uncertainty on the part of the endoscopist in determining inadequate bowel prep based on evolving guidelines, the researchers noted. However, the higher frequency of recommendations for repeat procedures within 1 year for patients with advanced disease suggests that endoscopists are taking pathology into account.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of standardized assessment of bowel prep quality, variation in descriptions of bowel cleanliness, and lack of information on the primary factor in follow-up recommendations. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, the inclusion of multiple sites and providers, and the low volume of timely repeat procedures, which has clinical implications in terms of missed lesions, “including potential interval CRC [colorectal cancer],” the researchers said.

Get the word out on describing preps and planning follow-ups

The current study is important because it highlights that, even when endoscopists have a reasonable understanding on how to set follow-up intervals for polyp follow-up, what to do with a patient who comes in poorly prepped is more of a problem, Kim L. Isaacs, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Dr Isaacs said she was not surprised by the study findings. “There are all gradations of inadequate preps that limit visualization in different ways, and there are many ways of recording this on procedure reports. The findings in the current study emphasize several points. The first is that the recommendation of following up an inadequate or poor prep in a year needs to be widely disseminated. The second is that there needs to be more education on standardization on how preps are described. In some poor preps, much of the colon can be seen, and clinicians can identify polyps 5-6 mm, so a 1-year follow-up may not be needed.” This type of research is challenging if the data are not standardized, she added.

Dr. Isaacs agreed with the authors’ description of repeat colonoscopies after poor bowel prep as a quality improvement area given the variability in following current recommendations, which leads into next steps for research.

“Understanding reasons for the recommendations that endoscopists made for follow-up would be the next step in this type of research,” Dr Isaacs noted. “After that, studies on the impact of an educational intervention, followed by repeating the initial assessment.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose; however, lead author Dr. Calderwood disclosed support from the National Cancer Institute, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Cancer Research Fellows Program, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Norris Cotton Cancer Center, and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr Isaacs had no financial conflicts to disclose but has previously served on the editorial board of GI & Hepatology News.

FROM GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

USPSTF final recommendation on CRC screening: 45 is the new 50

Screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) should now begin at the age of 45 and not 50 for average-risk individuals in the United States, notes the final recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

The recommendation finalizes draft guidelines issued in October 2020 and mandates insurance coverage to ensure equal access to CRC screening regardless of a patient’s insurance status.

The USPSTF’s final recommendations also now align with those of the American Cancer Society, which lowered the age for initiation of CRC screening to 45 years in 2018.

“New statistics project an alarming rise in the incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer, projected to be the leading cause of cancer death in patients aged 20-49 by 2040,” commented Kimmie Ng, MD, MPH, director, Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and lead author of a JAMA editorial about the new guideline.

“We must take bold steps to translate the lowered age of beginning screening into meaningful decreases in CRC incidence and mortality,” she emphasized.

The USPSTF recommendations and substantial evidence supporting them were published online May 18, 2021, in JAMA.

Risk factors for CRC

As the USPSTF authors noted, age is one of the most important risk factors for CRC, with nearly 94% of all new cases of CRC occurring in adults 45 years of age and older. Justification for the lower age of CRC screening initiation was based on simulation models showing that initiation of screening at the age of 45 was associated with an estimated additional 22-27 life-years gained, compared with starting at the age of 50.

The USPSTF continues to recommend screening for CRC in all adults aged between 50 and 75 years, lowering the age for screening to 45 years in recognition of the fact that, in 2020, 11% of colon cancers and 15% of rectal cancers occurred in patients under the age of 50.

The USPSTF also continues to conclude that there is a “small net benefit” of screening for CRC in adults aged between 76 and 85 years who have been previously screened.

However, the decision to screen patients in this age group should be based on individual risk factors for CRC, a patient’s overall health status, and personal preference. Perhaps self-evidently, adults in this age group who have never been screened for CRC are more likely to benefit from CRC screening than those who have been previously screened.

Similar to the previous guidelines released in 2016, the updated USPSTF recommendations continue to offer a menu of screening strategies, although the frequency of screening for each of the screening strategies varies. Recommended screening strategies include:

- High-sensitivity guaiac fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year

- Stool DNA-FIT every 1-3 years

- CT colonography every 5 years

- every 5 years

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years plus annual FIT

- screening every 10 years

“Based on the evidence, there are many tests available that can effectively screen for colorectal cancer and the right test is the one that gets done,” USPSTF member Martha Kubik, PhD, RN, said in a statement.

“To encourage screening and help patients select the best test for them, we urge primary care clinicians to talk about the pros and cons of the various recommended options with their patients,” she added.

An accompanying review of the effectiveness, accuracy, and potential harms of CRC screening methods underscores how different screening tests have different levels of evidence demonstrating their ability to detect cancer, precursor lesions, or both, as well as their ability to reduce mortality from cancer.

Eligible patients

Currently, fewer than 70% of eligible patients in the United States undergo CRC screening, Dr. Ng pointed out in the editorial. In addition, CRC disproportionately affects African American patients, who are about 20% more likely to get CRC and about 40% more likely to die from it, compared with other patient groups. Modeling studies published along with the USPSTF recommendations showed equal benefit for screening regardless of race and gender, underscoring the importance of screening adherence, especially in patient populations disproportionately affected by CRC.

“Far too many people in the U.S. are not receiving this lifesaving preventive service,” USPSTF vice chair Michael Barry, MD, said in a statement.

“We hope that this new recommendation to screen people ages 45-49, coupled with our long-standing recommendation to screen people 50-75, will prevent more people from dying from colorectal cancer,” he added.

Dr. Ng echoed this sentiment in her editorial: “The USPSTF recommendation for beginning colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults at age 45 years has moved the field one step forward and indicates that ‘45 is the new 50,’ ” she observed.

“Lowering the recommended age to initiate screening will make colorectal cancer screening available to millions more people in the United States and, hopefully, many more lives will be saved by catching colorectal cancer earlier as well as by preventing colorectal cancer,” Dr. Ng affirmed.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in USPSTF meetings.