User login

Problematic Medications: Antibiotics in Renal Patients

Q) At a lecture I recently attended, the speaker said sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim is a potentially dangerous medication. I use it all the time. Is there any data to support her comments? Where did she get her information?

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMX/TMP) is a combination of two antibiotics, each of which has the potential to interact with other substances.

It is well documented that sulfamethoxazole can inhibit the metabolism of cytochrome P450 2C9 substrates. Frequently prescribed medications that also use the cytochrome substrate include warfarin and oral antihypoglycemic agents.

Trimethoprim’s distinct properties also lead to drug interactions. Trimethoprim inhibits sodium uptake by the appropriate channels in the distal tubule of the kidney, preventing reabsorption and altering the electrical balance of the tubular cells. As a result, the amount of potassium excreted into the urine is reduced, yielding an accumulation of serum potassium.1

High serum potassium retention can manifest as hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Use of potassium-sparing drugs by patients with comorbidities, including CKD, can increase risk for hyperkalemia; concurrent use of these drugs with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) compounds the risk.2 The first reports of hyperkalemia with trimethoprim use occurred in HIV patients treated with large doses for Pneumocystis carinii infection.3

In a population-based case-control study, the results of which were published in the British Medical Journal, Fralick and colleagues analyzed data on older patients (age 66 or older) who were taking either ACE inhibitors or ARBs in combination with an antibiotic.4 They found a significantly increased risk for sudden death within seven days of prescription of SMX/TMP, compared to amoxicillin; a secondary analysis also revealed an increased risk for sudden death within 14 days with SMX/TMP. The researchers speculated that this excess risk, which translated to 3 sudden deaths in 1,000 patients taking SMX/TMP versus 1 sudden death in 1,000 patients taking amoxicillin, “reflects unrecognized arrhythmic death due to hyperkalemia.”

Since more than 250 million prescriptions for ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 20 million prescriptions for SMX/TMP are written each year, there will be instances of overlap. The prudent clinician would prescribe a different antibiotic or, if avoidance is not possible, use the lowest effective dose and duration of SMX/TMP. Close monitoring of serum potassium levels is warranted in patients with comorbidities, especially CKD, who are taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs—and of course, in our geriatric population. —DLC

Debra L. Coplon, DNP, DCC

City of Memphis Wellness Clinic, Tennessee

REFERENCES

1. Velazquez H, Perazella MA, Wright FS, Ellison DH. Renal mechanism of trimethoprim-induced hyperkalemia. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:296-301.

2. Horn JR, Hansten PD. Trimethoprim and potassium-sparing drugs: a risk for hyperkalemia. www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2011/February2011/DrugInteractions-0211. Accessed August 24, 2015.

3. Medina I, Mills J, Leoung G, et al. Oral therapy for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a controlled trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus trimethoprim-dapsone. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:776-782.

4. Fralick M, Macdonald EM, Gomes T, et al. Co-trimoxazole and sudden death in patients receiving inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system: population based study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6196.

5. Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, Gipson DS, et al. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014.

6. Muriithi AK, Leung N, Valeri AM, et al. Biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis, 1993-2011: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(4):558-566.

7. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, Herbison P. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86(4):837-844.

8. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrology. 2013;14:150.

Q) At a lecture I recently attended, the speaker said sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim is a potentially dangerous medication. I use it all the time. Is there any data to support her comments? Where did she get her information?

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMX/TMP) is a combination of two antibiotics, each of which has the potential to interact with other substances.

It is well documented that sulfamethoxazole can inhibit the metabolism of cytochrome P450 2C9 substrates. Frequently prescribed medications that also use the cytochrome substrate include warfarin and oral antihypoglycemic agents.

Trimethoprim’s distinct properties also lead to drug interactions. Trimethoprim inhibits sodium uptake by the appropriate channels in the distal tubule of the kidney, preventing reabsorption and altering the electrical balance of the tubular cells. As a result, the amount of potassium excreted into the urine is reduced, yielding an accumulation of serum potassium.1

High serum potassium retention can manifest as hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Use of potassium-sparing drugs by patients with comorbidities, including CKD, can increase risk for hyperkalemia; concurrent use of these drugs with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) compounds the risk.2 The first reports of hyperkalemia with trimethoprim use occurred in HIV patients treated with large doses for Pneumocystis carinii infection.3

In a population-based case-control study, the results of which were published in the British Medical Journal, Fralick and colleagues analyzed data on older patients (age 66 or older) who were taking either ACE inhibitors or ARBs in combination with an antibiotic.4 They found a significantly increased risk for sudden death within seven days of prescription of SMX/TMP, compared to amoxicillin; a secondary analysis also revealed an increased risk for sudden death within 14 days with SMX/TMP. The researchers speculated that this excess risk, which translated to 3 sudden deaths in 1,000 patients taking SMX/TMP versus 1 sudden death in 1,000 patients taking amoxicillin, “reflects unrecognized arrhythmic death due to hyperkalemia.”

Since more than 250 million prescriptions for ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 20 million prescriptions for SMX/TMP are written each year, there will be instances of overlap. The prudent clinician would prescribe a different antibiotic or, if avoidance is not possible, use the lowest effective dose and duration of SMX/TMP. Close monitoring of serum potassium levels is warranted in patients with comorbidities, especially CKD, who are taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs—and of course, in our geriatric population. —DLC

Debra L. Coplon, DNP, DCC

City of Memphis Wellness Clinic, Tennessee

REFERENCES

1. Velazquez H, Perazella MA, Wright FS, Ellison DH. Renal mechanism of trimethoprim-induced hyperkalemia. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:296-301.

2. Horn JR, Hansten PD. Trimethoprim and potassium-sparing drugs: a risk for hyperkalemia. www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2011/February2011/DrugInteractions-0211. Accessed August 24, 2015.

3. Medina I, Mills J, Leoung G, et al. Oral therapy for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a controlled trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus trimethoprim-dapsone. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:776-782.

4. Fralick M, Macdonald EM, Gomes T, et al. Co-trimoxazole and sudden death in patients receiving inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system: population based study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6196.

5. Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, Gipson DS, et al. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014.

6. Muriithi AK, Leung N, Valeri AM, et al. Biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis, 1993-2011: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(4):558-566.

7. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, Herbison P. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86(4):837-844.

8. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrology. 2013;14:150.

Q) At a lecture I recently attended, the speaker said sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim is a potentially dangerous medication. I use it all the time. Is there any data to support her comments? Where did she get her information?

Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMX/TMP) is a combination of two antibiotics, each of which has the potential to interact with other substances.

It is well documented that sulfamethoxazole can inhibit the metabolism of cytochrome P450 2C9 substrates. Frequently prescribed medications that also use the cytochrome substrate include warfarin and oral antihypoglycemic agents.

Trimethoprim’s distinct properties also lead to drug interactions. Trimethoprim inhibits sodium uptake by the appropriate channels in the distal tubule of the kidney, preventing reabsorption and altering the electrical balance of the tubular cells. As a result, the amount of potassium excreted into the urine is reduced, yielding an accumulation of serum potassium.1

High serum potassium retention can manifest as hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Use of potassium-sparing drugs by patients with comorbidities, including CKD, can increase risk for hyperkalemia; concurrent use of these drugs with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) compounds the risk.2 The first reports of hyperkalemia with trimethoprim use occurred in HIV patients treated with large doses for Pneumocystis carinii infection.3

In a population-based case-control study, the results of which were published in the British Medical Journal, Fralick and colleagues analyzed data on older patients (age 66 or older) who were taking either ACE inhibitors or ARBs in combination with an antibiotic.4 They found a significantly increased risk for sudden death within seven days of prescription of SMX/TMP, compared to amoxicillin; a secondary analysis also revealed an increased risk for sudden death within 14 days with SMX/TMP. The researchers speculated that this excess risk, which translated to 3 sudden deaths in 1,000 patients taking SMX/TMP versus 1 sudden death in 1,000 patients taking amoxicillin, “reflects unrecognized arrhythmic death due to hyperkalemia.”

Since more than 250 million prescriptions for ACE inhibitors/ARBs and 20 million prescriptions for SMX/TMP are written each year, there will be instances of overlap. The prudent clinician would prescribe a different antibiotic or, if avoidance is not possible, use the lowest effective dose and duration of SMX/TMP. Close monitoring of serum potassium levels is warranted in patients with comorbidities, especially CKD, who are taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs—and of course, in our geriatric population. —DLC

Debra L. Coplon, DNP, DCC

City of Memphis Wellness Clinic, Tennessee

REFERENCES

1. Velazquez H, Perazella MA, Wright FS, Ellison DH. Renal mechanism of trimethoprim-induced hyperkalemia. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:296-301.

2. Horn JR, Hansten PD. Trimethoprim and potassium-sparing drugs: a risk for hyperkalemia. www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2011/February2011/DrugInteractions-0211. Accessed August 24, 2015.

3. Medina I, Mills J, Leoung G, et al. Oral therapy for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a controlled trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus trimethoprim-dapsone. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:776-782.

4. Fralick M, Macdonald EM, Gomes T, et al. Co-trimoxazole and sudden death in patients receiving inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system: population based study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6196.

5. Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, Gipson DS, et al. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014.

6. Muriithi AK, Leung N, Valeri AM, et al. Biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis, 1993-2011: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(4):558-566.

7. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, Herbison P. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86(4):837-844.

8. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrology. 2013;14:150.

Be Sure to Look for Secondary Diabetes

A 63-year-old Hispanic woman was referred to endocrinology by her primary care provider for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which was diagnosed 16 years ago. Her antidiabetic medications included insulin glargine (55 U bid), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glipizide (10 mg bid). She also had known dyslipidemia, hypertension, and depression. There was a history of poorly controlled glucose (A1C between 9% and 13% in the past three years).

This was a relatively common new patient consult in our endocrine clinic. Upon entering the room, I was greeted by the patient and two family members. I quickly noticed the patient’s facial plethora and central obesity with comparatively thin extremities. Further inquiry revealed that the greatest challenge for the patient and her family was her bouts of severe depression, during which she would stop caring and cease to take her medications.

During the physical exam, mild but not significant supraclavicular and dorsocervical fat pads were appreciated. The exam was otherwise unremarkable, with no purple striae on the torso, abdomen, breasts, and extremities.

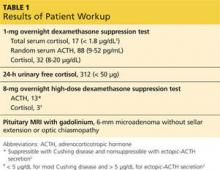

In addition to routine diabetes lab tests (ie, A1C, chemistry panel, lipid panel, urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio), an overnight 1-mg oral dexamethasone suppression test was ordered. Results of the latter were abnormal, and further workup confirmed Cushing disease (see Table 1 for results). The patient was referred for neurosurgery.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION: SECONDARY DIABETES

It is well known that the prevalence of diabetes is skyrocketing, and medical offices are filled with affected patients. According to a 2011 report from the CDC, 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases are type 2, 5% are type 1 (autoimmune), and the rest (about 1% to 5%) are “other types” of diabetes.3 Due to these disproportionate statistics, clinicians often overlook the possibility of uncommon etiologies and assume all patients with diabetes have type 2—especially when the patient is overweight or obese.

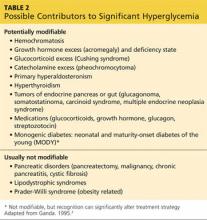

Table 2 lists conditions and medications that may contribute to significant hyperglycemia.4 Some contributors are rather obvious (eg, status post pancreatectomy) or have no impact on treatment strategy (eg, chromosomal defects such as Down or Turner syndrome). However, certain conditions, such as Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, and hemochromatosis, can be relatively hard to recognize due to the variable rate of clinical manifestation, especially in the earlier stages of the disease. Experts have raised concerns that the prevalence of secondary diabetes (1% to 5%) may actually be underestimated due to “misdiagnosis” as T2DM.

Early detection of the underlying disorder, followed by initiation of appropriate treatment, is critical. It will not only improve but also may resolve the patient’s hyperglycemia, and it may also reverse or stop the damage to other vital organs.

The case patient had an unfortunate situation in which her Cushing syndrome was masked by commonly encountered diagnoses of hypertension, T2DM, obesity, and depression. Cushing is an easy diagnosis to miss, since it has an insidious onset and it can take more than five years for some of the physical findings to become evident.

Pancreatic cancer is another uncommon but critical disease worth mentioning. Pancreatic cancer should be in the differential diagnosis for previously euglycemic patients who experience abrupt elevation of glucose or previously well-managed patients whose glucose values quickly get out of control without obvious cause (eg, medication cessation, addition of glucocorticoid therapy, uncontrolled diet).

In our practice, we have encountered three patients with pancreatic cancer in this setting. The only sign was a sudden rise in glucose (300 to 500 mg/dL throughout the day) in patients whose A1C had been low (in the 6% range) with one or two oral medications. Thorough history taking did not reveal any potential causes for sudden hyperglycemia. Only one patient had a palpable mass on abdominal exam and elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin. Unfortunately, that patient died eight months later. The other two had favorable outcomes from surgery and chemotherapy. Early detection was the key for those two patients.

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Since the majority of patients with diabetes have T2DM, it is easy to “default” and start treating all patients as such, especially if they are overweight or obese. However, up to 5% of patients actually have underlying disease that may cause or worsen their diabetic status. Overlooking these rare conditions can be detrimental to the patient, as it will adversely affect not only glycemic control but more importantly, overall health. Identifying the underlying disease will allow the patient to receive appropriate treatment, which may offload a significant burden on glycemic control and in some cases, cure the hyperglycemia.

REFERENCES

1. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540.

2. Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Up-to-Date. www.uptodate.com/contents/establishing-the-cause-of-cushings-syndrome. Accessed June 24, 2015.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2015.

4. Ganda OP. Prevalence and incidence of secondary and other types of diabetes. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995:69-84.

A 63-year-old Hispanic woman was referred to endocrinology by her primary care provider for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which was diagnosed 16 years ago. Her antidiabetic medications included insulin glargine (55 U bid), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glipizide (10 mg bid). She also had known dyslipidemia, hypertension, and depression. There was a history of poorly controlled glucose (A1C between 9% and 13% in the past three years).

This was a relatively common new patient consult in our endocrine clinic. Upon entering the room, I was greeted by the patient and two family members. I quickly noticed the patient’s facial plethora and central obesity with comparatively thin extremities. Further inquiry revealed that the greatest challenge for the patient and her family was her bouts of severe depression, during which she would stop caring and cease to take her medications.

During the physical exam, mild but not significant supraclavicular and dorsocervical fat pads were appreciated. The exam was otherwise unremarkable, with no purple striae on the torso, abdomen, breasts, and extremities.

In addition to routine diabetes lab tests (ie, A1C, chemistry panel, lipid panel, urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio), an overnight 1-mg oral dexamethasone suppression test was ordered. Results of the latter were abnormal, and further workup confirmed Cushing disease (see Table 1 for results). The patient was referred for neurosurgery.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION: SECONDARY DIABETES

It is well known that the prevalence of diabetes is skyrocketing, and medical offices are filled with affected patients. According to a 2011 report from the CDC, 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases are type 2, 5% are type 1 (autoimmune), and the rest (about 1% to 5%) are “other types” of diabetes.3 Due to these disproportionate statistics, clinicians often overlook the possibility of uncommon etiologies and assume all patients with diabetes have type 2—especially when the patient is overweight or obese.

Table 2 lists conditions and medications that may contribute to significant hyperglycemia.4 Some contributors are rather obvious (eg, status post pancreatectomy) or have no impact on treatment strategy (eg, chromosomal defects such as Down or Turner syndrome). However, certain conditions, such as Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, and hemochromatosis, can be relatively hard to recognize due to the variable rate of clinical manifestation, especially in the earlier stages of the disease. Experts have raised concerns that the prevalence of secondary diabetes (1% to 5%) may actually be underestimated due to “misdiagnosis” as T2DM.

Early detection of the underlying disorder, followed by initiation of appropriate treatment, is critical. It will not only improve but also may resolve the patient’s hyperglycemia, and it may also reverse or stop the damage to other vital organs.

The case patient had an unfortunate situation in which her Cushing syndrome was masked by commonly encountered diagnoses of hypertension, T2DM, obesity, and depression. Cushing is an easy diagnosis to miss, since it has an insidious onset and it can take more than five years for some of the physical findings to become evident.

Pancreatic cancer is another uncommon but critical disease worth mentioning. Pancreatic cancer should be in the differential diagnosis for previously euglycemic patients who experience abrupt elevation of glucose or previously well-managed patients whose glucose values quickly get out of control without obvious cause (eg, medication cessation, addition of glucocorticoid therapy, uncontrolled diet).

In our practice, we have encountered three patients with pancreatic cancer in this setting. The only sign was a sudden rise in glucose (300 to 500 mg/dL throughout the day) in patients whose A1C had been low (in the 6% range) with one or two oral medications. Thorough history taking did not reveal any potential causes for sudden hyperglycemia. Only one patient had a palpable mass on abdominal exam and elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin. Unfortunately, that patient died eight months later. The other two had favorable outcomes from surgery and chemotherapy. Early detection was the key for those two patients.

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Since the majority of patients with diabetes have T2DM, it is easy to “default” and start treating all patients as such, especially if they are overweight or obese. However, up to 5% of patients actually have underlying disease that may cause or worsen their diabetic status. Overlooking these rare conditions can be detrimental to the patient, as it will adversely affect not only glycemic control but more importantly, overall health. Identifying the underlying disease will allow the patient to receive appropriate treatment, which may offload a significant burden on glycemic control and in some cases, cure the hyperglycemia.

REFERENCES

1. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540.

2. Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Up-to-Date. www.uptodate.com/contents/establishing-the-cause-of-cushings-syndrome. Accessed June 24, 2015.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2015.

4. Ganda OP. Prevalence and incidence of secondary and other types of diabetes. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995:69-84.

A 63-year-old Hispanic woman was referred to endocrinology by her primary care provider for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which was diagnosed 16 years ago. Her antidiabetic medications included insulin glargine (55 U bid), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glipizide (10 mg bid). She also had known dyslipidemia, hypertension, and depression. There was a history of poorly controlled glucose (A1C between 9% and 13% in the past three years).

This was a relatively common new patient consult in our endocrine clinic. Upon entering the room, I was greeted by the patient and two family members. I quickly noticed the patient’s facial plethora and central obesity with comparatively thin extremities. Further inquiry revealed that the greatest challenge for the patient and her family was her bouts of severe depression, during which she would stop caring and cease to take her medications.

During the physical exam, mild but not significant supraclavicular and dorsocervical fat pads were appreciated. The exam was otherwise unremarkable, with no purple striae on the torso, abdomen, breasts, and extremities.

In addition to routine diabetes lab tests (ie, A1C, chemistry panel, lipid panel, urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio), an overnight 1-mg oral dexamethasone suppression test was ordered. Results of the latter were abnormal, and further workup confirmed Cushing disease (see Table 1 for results). The patient was referred for neurosurgery.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION: SECONDARY DIABETES

It is well known that the prevalence of diabetes is skyrocketing, and medical offices are filled with affected patients. According to a 2011 report from the CDC, 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases are type 2, 5% are type 1 (autoimmune), and the rest (about 1% to 5%) are “other types” of diabetes.3 Due to these disproportionate statistics, clinicians often overlook the possibility of uncommon etiologies and assume all patients with diabetes have type 2—especially when the patient is overweight or obese.

Table 2 lists conditions and medications that may contribute to significant hyperglycemia.4 Some contributors are rather obvious (eg, status post pancreatectomy) or have no impact on treatment strategy (eg, chromosomal defects such as Down or Turner syndrome). However, certain conditions, such as Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, and hemochromatosis, can be relatively hard to recognize due to the variable rate of clinical manifestation, especially in the earlier stages of the disease. Experts have raised concerns that the prevalence of secondary diabetes (1% to 5%) may actually be underestimated due to “misdiagnosis” as T2DM.

Early detection of the underlying disorder, followed by initiation of appropriate treatment, is critical. It will not only improve but also may resolve the patient’s hyperglycemia, and it may also reverse or stop the damage to other vital organs.

The case patient had an unfortunate situation in which her Cushing syndrome was masked by commonly encountered diagnoses of hypertension, T2DM, obesity, and depression. Cushing is an easy diagnosis to miss, since it has an insidious onset and it can take more than five years for some of the physical findings to become evident.

Pancreatic cancer is another uncommon but critical disease worth mentioning. Pancreatic cancer should be in the differential diagnosis for previously euglycemic patients who experience abrupt elevation of glucose or previously well-managed patients whose glucose values quickly get out of control without obvious cause (eg, medication cessation, addition of glucocorticoid therapy, uncontrolled diet).

In our practice, we have encountered three patients with pancreatic cancer in this setting. The only sign was a sudden rise in glucose (300 to 500 mg/dL throughout the day) in patients whose A1C had been low (in the 6% range) with one or two oral medications. Thorough history taking did not reveal any potential causes for sudden hyperglycemia. Only one patient had a palpable mass on abdominal exam and elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin. Unfortunately, that patient died eight months later. The other two had favorable outcomes from surgery and chemotherapy. Early detection was the key for those two patients.

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Since the majority of patients with diabetes have T2DM, it is easy to “default” and start treating all patients as such, especially if they are overweight or obese. However, up to 5% of patients actually have underlying disease that may cause or worsen their diabetic status. Overlooking these rare conditions can be detrimental to the patient, as it will adversely affect not only glycemic control but more importantly, overall health. Identifying the underlying disease will allow the patient to receive appropriate treatment, which may offload a significant burden on glycemic control and in some cases, cure the hyperglycemia.

REFERENCES

1. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540.

2. Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Up-to-Date. www.uptodate.com/contents/establishing-the-cause-of-cushings-syndrome. Accessed June 24, 2015.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2015.

4. Ganda OP. Prevalence and incidence of secondary and other types of diabetes. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995:69-84.

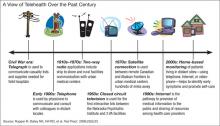

The Right Care at the Right Time and in the Right Place: The Role of Technology in the VHA

Embracing technology is nothing new for the VHA, whether it is telehealth, e-consults, or electronic health records. “The VHA is in a unique position to create the first truly national telemedicine network in the U.S.,” Adam W. Darkins, MD, then acting chief consultant of telemedicine at the VA wrote in a 2001 newsletter. “It is our collective task to make sure that if this happens, we have a system that can ‘plug and play.’”1

To better understand the progress in delivering health care, Federal Practitioner decided to devote this entire issue to the topic and to discuss the VHA and technology with Madhulika Agarwal, MD, MPH. As deputy under secretary for health for policy and services, Dr. Agarwal has been at the heart of the VHA’s embrace of many of these technologies for health care delivery and has been in a position to oversee their execution. More than anyone else at the VHA, she is familiar with the potential and limitations of telehealth.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the interview. To hear the complete interview, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

Importance of Telehealth to the VHA

Madhulika Agarwal, MD, MPH. Our goal is to ensure that veterans have optimal health and that we deliver the best health care with a focus on timely access and with an exceptional experience. And over the years, we have been building technologic tools so that we can provide the right care at the right time and in the right place. Telehealth affords veterans the convenience of accessing primary or specialized care services either from their local VA community clinic or from the privacy of their own home.

Now we have many virtual access solutions. The home telehealth, clinical video teleconferencing, store-and-forward technologies, e-consults, My HealtheVet, plus SCAN-ECHO [Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes]; and these all have demonstrated that they are mission-critical tools, which improve and expand the access for veterans who may have difficulty accessing care for multiple reasons.

It could be some clinical issues where there are transportation difficulties, such as for veterans with spinal cord injury, or mild traumatic brain injury, or geographic barriers. Many of our veterans, I would say roughly 40% to 45% of them, live in rural and highly rural areas where they may not have access to care nearby. Or it could be further exacerbated with geographic challenges by inclement weather or the drive times. And lastly, I would say it’s the lack of specialists in these rural communities where many of our veterans live.

VHA is successfully integrating into the existing technical administrative clinical infrastructures, and this infrastructure provides a reliable and robust IT network. We have an electronic health record. We provide national policy guidance regarding health information security, credentialing, privileging, etc. And our strategic goal has been to have personalized, proactive, patient-driven care; and telehealth supports that goal.

Improving Veteran Access

Dr. Agarwal. It’s interesting that both the Choice program, which is part of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, known as VACAA, and telehealth aim at improving veteran access to care. Under the Choice program, many veterans now have the option to access community partner health care rather than waiting for a VA appointment, or traveling to a VA facility when the geographic distance is more than 40 miles, or if the appointment in the VA is not available for 30 days.

The Choice program and telehealth are 2 very concrete examples of VHA’s transformation from a facility or provider-centric health care delivery model to a model that puts the veteran’s needs at the center and improving the veteran’s access to resources to meet their health care needs.

Related: Committed to Showing Results at the VA

More than 717,000 veterans have accessed VA care through telehealth in fiscal year [FY] 14, and 45% of these veterans live in rural and highly rural areas. In FY14, the total for veterans using telehealth represented about an 18% growth from the prior year; and the telehealth services provide access to help in more than 45 different specialty areas, including those areas where VHA has a particular expertise, especially, for example, in mental health that may not be available from the local community partner.

Telehealth Uses

Dr. Agarwal. A veteran who is living in a rural area, let’s just say in some rural part of Maryland, and has to commute to the Baltimore VA, which you know is an inner-city VA medical center, to keep his appointment for a mental health condition with his VA provider. Now, using telemental health, this veteran can access this provider from his or her own home through encrypted video conferencing and complete the telemental health visit in the comfort of his or her own home so that they are not subject to the traffic and other challenges that they would otherwise face and get even more stressed than what they started out with. The ability, the convenience of having the service of counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy into their own homes, is just remarkable.

Another example that I could cite for you would be an appointment in the hearing aid clinic. So a veteran who lives in the Florida Keys normally would have to travel 5 hours from the Florida Keys, go to Miami, stay in a hotel overnight so that they can go to their appointment at 8 am. Instead, the veteran now can visit the Key West clinic and have his hearing aid adjusted by a VA audiologist who’s located in Miami; and it saves the entire trip.

The third one I will cite you has to do with the C&P [Compensation & Pension] exams. Now, a veteran living even out of the country can access a VA provider in Connecticut or some [other] state, using the encrypted video conferencing; and they can have the whole clinical evaluation for C&P completed using the video conferencing. These are some of the examples of how telehealth has been used very successfully.

Technologic and Educational Challenges

Dr. Agarwal. We have been a pioneer of telehealth. And with that, of course, all those challenges come into play. And we certainly have implementation challenges that include provider and patient education and their buy-in into the use of technology and providing services as well as the technology itself and some administrative issues. They can all be very closely linked.

You know, one illustrative example that I just cited earlier about video conferencing is one such example into the veteran’s home. It is very convenient.… We started to implement this home telemental health program a couple of years ago. But since then, about 108,000 veterans have accessed using the video conferencing technology; but fewer than 2,000 or so have done it from their own home. And that’s largely because the current video visit from home is quite cumbersome. It requires passwords for each visit. It requires that the veteran download VA-licensed software on their own device. And in addition, there are restrictions because of the availability of the broadband Internet connectivity, which is required for the video visit—more so in the rural areas.

Related: Preparing the Military Health System for the 21st Century

Our general counsel is reviewing and attempting to resolve state licensure requirements that have been raised by some states, because the veterans here receive care at home and outside of our VA brick-and-mortar facility, as well as the legality of VA providers potentially prescribing a controlled substance for a veteran at home without a prior in-person office visit.

But to overcome the provider challenges, the national telehealth training and resource center has been working on training the providers in the use of telehealth. Roughly 11,400 VA staff have been trained in the use of telehealth in FY14. We have currently 144 facility telehealth coordinators and more than 1,100 telehealth clinical technicians who assist with training and outreach for both VA staff and veteran patients.

Legal/Security Challenges

Dr. Agarwal. High-speed connectivity happens to be one of the key ones.… Using 4G services, I think, is going to be essential for every veteran regardless of rurality. And when these 4G services are not available, that certainly hinders the ability to provide telehealth to all veterans. Having the right security with full data encryption is essential so that we can protect the private health information of the veterans.

But unfortunately, at this time, there is not an easy way to do that. I think a lot of innovation is required so that we can make it much easier for the veterans with 1-button access, both for the veterans as well as for the providers. And that’s going to require significant effort in the grid technology as well as overcoming certain legal requirements.

What Is Driving Telehealth?

Dr. Agarwal. The real driver here has to be the veterans’ needs, not the needs of telehealth nor the clinical services or operations. I think the whole goal here is that we must use technology to the extent possible. We have to move toward virtual access as the norm.

As much as possible, we should provide the virtual access in the veterans’ homes or wherever the veterans would like to receive their services. Make the connectivity as simple as possible for the veterans and move beyond the concept of the episodic visit so that the health information and self-care management tools are available to the veterans at all times. And that essentially needs to be the overarching strategy, and that should drive how we develop the technologies to provide the services.

Data Analysis

Dr. Agarwal. We have the general enrollee data. We look at access gaps in clinical services and the telehealth activity data for our program management and oversight as well as in developing an overarching strategy for the clinical services and telehealth services. It’s done somewhat in conjunction. And our outcome analysis shows that there has been significant reduction in admissions and bed days of care with the use of telehealth.

For example, in FY14, an analysis of 10,621 veterans who were newly enrolled in home telehealth with noninstitutional care needs and chronic care management categories had a decrease of about 54% of bed days of care. This was about a 32% decrease in the hospital admissions compared [with] the same patient data prior to the enrollment and home telehealth. The analysis of telemental health outcomes shows that there was a 35% reduction in acute psychiatric bed days of care for veterans receiving CBT [cognitive behavioral therapy] or the clinical video conferencing telemental health in FY14 when it was compared [with] the utilization in the prior year.

Telehealth Pilot Programs

Dr. Agarwal. I must admit that there are many more programs that begin in the facilities, but at the national level. The first one is the tele-ICU implementation, where VISN 23 is supporting VISN 15, 5 of the medical centers with clinical video teleconferencing capability for live interactive consults with ICU specialists; and it covers about 78 beds. VISN 10 is supporting VISN 7 in 7 of their medical centers, which covers about 72 beds.

Another program, which is in the pilot phase right now, is the telewound care pilot, which is being implemented in 6 VISNs and combines the use of home telehealth, clinical video teleconferencing, and store-and-forward telehealth technologies to create access to a continuum of wound care options across multiple patients and provider settings and locations, all with the goal of enhancing and improving wound care treatment and healing.… The initial phase has been that all the participating facilities have been identified, and some of the operations manuals have been developed.

Related: Acting Surgeon General Confident in Battle Against Tobacco, Ebola, and Preventable Diseases

The third quarter of this year, we will have a completion of the operations manual Provider Training and Treatment Template. The local sites are also working on the infrastructure and knowledge base so that this project can be completed by FY15.

And the last highlight that I’ll mention, which is in its very early stages, is a low-acuity/low-intensity pilot with the focus on health promotion and health prevention behaviors, such as tobacco cessation, weight management, and newly diagnosed but stable veterans with diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart failure, using a web-based browser technology.

VA Telehealth Leadership

Dr. Agarwal. Overall, when we start to look at the monumental impact of technology on other industries, such as banking, shopping, travel, and even personal communications, the emerging technologies continue to change the overall landscape of all these environments. This is an exciting time to be in the health care industry, because I think we have lagged somewhat behind in using technology. But as we look forward, the consumer-driven health care is going to become the norm.

As you know, VA has long been a pioneer with electronic medical records and with virtual modalities, such as telehealth both in the home and in the community, the use of patient web portals, such as My HealtheVet, secure messaging for various apps, kiosks; and we remain on the forefront of developing and utilizing these approaches to enhance health care delivery.

We all know that health care in the U.S. is complex and fragmented. VA is looking to become the benchmark in U.S. health care delivery, aiding in the transformation of the delivery of services for veterans and families, focusing on unified, integrated, and personalized virtual services that seamlessly connect them with the state-of-the-art health care system.

1. Darkins A. A message from the acting chief consultant: telemedicine grows throughout VHA. Telemedicine News. 2001;1(1):1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.telehealth.va.gov/newsletter/2001/040201-newsletter_spring_01.pdf. Published April 2, 2001. Accessed June 23, 2015.

Embracing technology is nothing new for the VHA, whether it is telehealth, e-consults, or electronic health records. “The VHA is in a unique position to create the first truly national telemedicine network in the U.S.,” Adam W. Darkins, MD, then acting chief consultant of telemedicine at the VA wrote in a 2001 newsletter. “It is our collective task to make sure that if this happens, we have a system that can ‘plug and play.’”1

To better understand the progress in delivering health care, Federal Practitioner decided to devote this entire issue to the topic and to discuss the VHA and technology with Madhulika Agarwal, MD, MPH. As deputy under secretary for health for policy and services, Dr. Agarwal has been at the heart of the VHA’s embrace of many of these technologies for health care delivery and has been in a position to oversee their execution. More than anyone else at the VHA, she is familiar with the potential and limitations of telehealth.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the interview. To hear the complete interview, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

Importance of Telehealth to the VHA

Madhulika Agarwal, MD, MPH. Our goal is to ensure that veterans have optimal health and that we deliver the best health care with a focus on timely access and with an exceptional experience. And over the years, we have been building technologic tools so that we can provide the right care at the right time and in the right place. Telehealth affords veterans the convenience of accessing primary or specialized care services either from their local VA community clinic or from the privacy of their own home.

Now we have many virtual access solutions. The home telehealth, clinical video teleconferencing, store-and-forward technologies, e-consults, My HealtheVet, plus SCAN-ECHO [Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes]; and these all have demonstrated that they are mission-critical tools, which improve and expand the access for veterans who may have difficulty accessing care for multiple reasons.

It could be some clinical issues where there are transportation difficulties, such as for veterans with spinal cord injury, or mild traumatic brain injury, or geographic barriers. Many of our veterans, I would say roughly 40% to 45% of them, live in rural and highly rural areas where they may not have access to care nearby. Or it could be further exacerbated with geographic challenges by inclement weather or the drive times. And lastly, I would say it’s the lack of specialists in these rural communities where many of our veterans live.

VHA is successfully integrating into the existing technical administrative clinical infrastructures, and this infrastructure provides a reliable and robust IT network. We have an electronic health record. We provide national policy guidance regarding health information security, credentialing, privileging, etc. And our strategic goal has been to have personalized, proactive, patient-driven care; and telehealth supports that goal.

Improving Veteran Access

Dr. Agarwal. It’s interesting that both the Choice program, which is part of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, known as VACAA, and telehealth aim at improving veteran access to care. Under the Choice program, many veterans now have the option to access community partner health care rather than waiting for a VA appointment, or traveling to a VA facility when the geographic distance is more than 40 miles, or if the appointment in the VA is not available for 30 days.

The Choice program and telehealth are 2 very concrete examples of VHA’s transformation from a facility or provider-centric health care delivery model to a model that puts the veteran’s needs at the center and improving the veteran’s access to resources to meet their health care needs.

Related: Committed to Showing Results at the VA

More than 717,000 veterans have accessed VA care through telehealth in fiscal year [FY] 14, and 45% of these veterans live in rural and highly rural areas. In FY14, the total for veterans using telehealth represented about an 18% growth from the prior year; and the telehealth services provide access to help in more than 45 different specialty areas, including those areas where VHA has a particular expertise, especially, for example, in mental health that may not be available from the local community partner.

Telehealth Uses

Dr. Agarwal. A veteran who is living in a rural area, let’s just say in some rural part of Maryland, and has to commute to the Baltimore VA, which you know is an inner-city VA medical center, to keep his appointment for a mental health condition with his VA provider. Now, using telemental health, this veteran can access this provider from his or her own home through encrypted video conferencing and complete the telemental health visit in the comfort of his or her own home so that they are not subject to the traffic and other challenges that they would otherwise face and get even more stressed than what they started out with. The ability, the convenience of having the service of counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy into their own homes, is just remarkable.

Another example that I could cite for you would be an appointment in the hearing aid clinic. So a veteran who lives in the Florida Keys normally would have to travel 5 hours from the Florida Keys, go to Miami, stay in a hotel overnight so that they can go to their appointment at 8 am. Instead, the veteran now can visit the Key West clinic and have his hearing aid adjusted by a VA audiologist who’s located in Miami; and it saves the entire trip.

The third one I will cite you has to do with the C&P [Compensation & Pension] exams. Now, a veteran living even out of the country can access a VA provider in Connecticut or some [other] state, using the encrypted video conferencing; and they can have the whole clinical evaluation for C&P completed using the video conferencing. These are some of the examples of how telehealth has been used very successfully.

Technologic and Educational Challenges

Dr. Agarwal. We have been a pioneer of telehealth. And with that, of course, all those challenges come into play. And we certainly have implementation challenges that include provider and patient education and their buy-in into the use of technology and providing services as well as the technology itself and some administrative issues. They can all be very closely linked.

You know, one illustrative example that I just cited earlier about video conferencing is one such example into the veteran’s home. It is very convenient.… We started to implement this home telemental health program a couple of years ago. But since then, about 108,000 veterans have accessed using the video conferencing technology; but fewer than 2,000 or so have done it from their own home. And that’s largely because the current video visit from home is quite cumbersome. It requires passwords for each visit. It requires that the veteran download VA-licensed software on their own device. And in addition, there are restrictions because of the availability of the broadband Internet connectivity, which is required for the video visit—more so in the rural areas.

Related: Preparing the Military Health System for the 21st Century

Our general counsel is reviewing and attempting to resolve state licensure requirements that have been raised by some states, because the veterans here receive care at home and outside of our VA brick-and-mortar facility, as well as the legality of VA providers potentially prescribing a controlled substance for a veteran at home without a prior in-person office visit.

But to overcome the provider challenges, the national telehealth training and resource center has been working on training the providers in the use of telehealth. Roughly 11,400 VA staff have been trained in the use of telehealth in FY14. We have currently 144 facility telehealth coordinators and more than 1,100 telehealth clinical technicians who assist with training and outreach for both VA staff and veteran patients.

Legal/Security Challenges

Dr. Agarwal. High-speed connectivity happens to be one of the key ones.… Using 4G services, I think, is going to be essential for every veteran regardless of rurality. And when these 4G services are not available, that certainly hinders the ability to provide telehealth to all veterans. Having the right security with full data encryption is essential so that we can protect the private health information of the veterans.

But unfortunately, at this time, there is not an easy way to do that. I think a lot of innovation is required so that we can make it much easier for the veterans with 1-button access, both for the veterans as well as for the providers. And that’s going to require significant effort in the grid technology as well as overcoming certain legal requirements.

What Is Driving Telehealth?

Dr. Agarwal. The real driver here has to be the veterans’ needs, not the needs of telehealth nor the clinical services or operations. I think the whole goal here is that we must use technology to the extent possible. We have to move toward virtual access as the norm.

As much as possible, we should provide the virtual access in the veterans’ homes or wherever the veterans would like to receive their services. Make the connectivity as simple as possible for the veterans and move beyond the concept of the episodic visit so that the health information and self-care management tools are available to the veterans at all times. And that essentially needs to be the overarching strategy, and that should drive how we develop the technologies to provide the services.

Data Analysis

Dr. Agarwal. We have the general enrollee data. We look at access gaps in clinical services and the telehealth activity data for our program management and oversight as well as in developing an overarching strategy for the clinical services and telehealth services. It’s done somewhat in conjunction. And our outcome analysis shows that there has been significant reduction in admissions and bed days of care with the use of telehealth.

For example, in FY14, an analysis of 10,621 veterans who were newly enrolled in home telehealth with noninstitutional care needs and chronic care management categories had a decrease of about 54% of bed days of care. This was about a 32% decrease in the hospital admissions compared [with] the same patient data prior to the enrollment and home telehealth. The analysis of telemental health outcomes shows that there was a 35% reduction in acute psychiatric bed days of care for veterans receiving CBT [cognitive behavioral therapy] or the clinical video conferencing telemental health in FY14 when it was compared [with] the utilization in the prior year.

Telehealth Pilot Programs

Dr. Agarwal. I must admit that there are many more programs that begin in the facilities, but at the national level. The first one is the tele-ICU implementation, where VISN 23 is supporting VISN 15, 5 of the medical centers with clinical video teleconferencing capability for live interactive consults with ICU specialists; and it covers about 78 beds. VISN 10 is supporting VISN 7 in 7 of their medical centers, which covers about 72 beds.

Another program, which is in the pilot phase right now, is the telewound care pilot, which is being implemented in 6 VISNs and combines the use of home telehealth, clinical video teleconferencing, and store-and-forward telehealth technologies to create access to a continuum of wound care options across multiple patients and provider settings and locations, all with the goal of enhancing and improving wound care treatment and healing.… The initial phase has been that all the participating facilities have been identified, and some of the operations manuals have been developed.

Related: Acting Surgeon General Confident in Battle Against Tobacco, Ebola, and Preventable Diseases

The third quarter of this year, we will have a completion of the operations manual Provider Training and Treatment Template. The local sites are also working on the infrastructure and knowledge base so that this project can be completed by FY15.

And the last highlight that I’ll mention, which is in its very early stages, is a low-acuity/low-intensity pilot with the focus on health promotion and health prevention behaviors, such as tobacco cessation, weight management, and newly diagnosed but stable veterans with diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart failure, using a web-based browser technology.

VA Telehealth Leadership

Dr. Agarwal. Overall, when we start to look at the monumental impact of technology on other industries, such as banking, shopping, travel, and even personal communications, the emerging technologies continue to change the overall landscape of all these environments. This is an exciting time to be in the health care industry, because I think we have lagged somewhat behind in using technology. But as we look forward, the consumer-driven health care is going to become the norm.

As you know, VA has long been a pioneer with electronic medical records and with virtual modalities, such as telehealth both in the home and in the community, the use of patient web portals, such as My HealtheVet, secure messaging for various apps, kiosks; and we remain on the forefront of developing and utilizing these approaches to enhance health care delivery.

We all know that health care in the U.S. is complex and fragmented. VA is looking to become the benchmark in U.S. health care delivery, aiding in the transformation of the delivery of services for veterans and families, focusing on unified, integrated, and personalized virtual services that seamlessly connect them with the state-of-the-art health care system.

Embracing technology is nothing new for the VHA, whether it is telehealth, e-consults, or electronic health records. “The VHA is in a unique position to create the first truly national telemedicine network in the U.S.,” Adam W. Darkins, MD, then acting chief consultant of telemedicine at the VA wrote in a 2001 newsletter. “It is our collective task to make sure that if this happens, we have a system that can ‘plug and play.’”1

To better understand the progress in delivering health care, Federal Practitioner decided to devote this entire issue to the topic and to discuss the VHA and technology with Madhulika Agarwal, MD, MPH. As deputy under secretary for health for policy and services, Dr. Agarwal has been at the heart of the VHA’s embrace of many of these technologies for health care delivery and has been in a position to oversee their execution. More than anyone else at the VHA, she is familiar with the potential and limitations of telehealth.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the interview. To hear the complete interview, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

Importance of Telehealth to the VHA

Madhulika Agarwal, MD, MPH. Our goal is to ensure that veterans have optimal health and that we deliver the best health care with a focus on timely access and with an exceptional experience. And over the years, we have been building technologic tools so that we can provide the right care at the right time and in the right place. Telehealth affords veterans the convenience of accessing primary or specialized care services either from their local VA community clinic or from the privacy of their own home.

Now we have many virtual access solutions. The home telehealth, clinical video teleconferencing, store-and-forward technologies, e-consults, My HealtheVet, plus SCAN-ECHO [Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes]; and these all have demonstrated that they are mission-critical tools, which improve and expand the access for veterans who may have difficulty accessing care for multiple reasons.

It could be some clinical issues where there are transportation difficulties, such as for veterans with spinal cord injury, or mild traumatic brain injury, or geographic barriers. Many of our veterans, I would say roughly 40% to 45% of them, live in rural and highly rural areas where they may not have access to care nearby. Or it could be further exacerbated with geographic challenges by inclement weather or the drive times. And lastly, I would say it’s the lack of specialists in these rural communities where many of our veterans live.

VHA is successfully integrating into the existing technical administrative clinical infrastructures, and this infrastructure provides a reliable and robust IT network. We have an electronic health record. We provide national policy guidance regarding health information security, credentialing, privileging, etc. And our strategic goal has been to have personalized, proactive, patient-driven care; and telehealth supports that goal.

Improving Veteran Access

Dr. Agarwal. It’s interesting that both the Choice program, which is part of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, known as VACAA, and telehealth aim at improving veteran access to care. Under the Choice program, many veterans now have the option to access community partner health care rather than waiting for a VA appointment, or traveling to a VA facility when the geographic distance is more than 40 miles, or if the appointment in the VA is not available for 30 days.

The Choice program and telehealth are 2 very concrete examples of VHA’s transformation from a facility or provider-centric health care delivery model to a model that puts the veteran’s needs at the center and improving the veteran’s access to resources to meet their health care needs.

Related: Committed to Showing Results at the VA

More than 717,000 veterans have accessed VA care through telehealth in fiscal year [FY] 14, and 45% of these veterans live in rural and highly rural areas. In FY14, the total for veterans using telehealth represented about an 18% growth from the prior year; and the telehealth services provide access to help in more than 45 different specialty areas, including those areas where VHA has a particular expertise, especially, for example, in mental health that may not be available from the local community partner.

Telehealth Uses

Dr. Agarwal. A veteran who is living in a rural area, let’s just say in some rural part of Maryland, and has to commute to the Baltimore VA, which you know is an inner-city VA medical center, to keep his appointment for a mental health condition with his VA provider. Now, using telemental health, this veteran can access this provider from his or her own home through encrypted video conferencing and complete the telemental health visit in the comfort of his or her own home so that they are not subject to the traffic and other challenges that they would otherwise face and get even more stressed than what they started out with. The ability, the convenience of having the service of counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy into their own homes, is just remarkable.

Another example that I could cite for you would be an appointment in the hearing aid clinic. So a veteran who lives in the Florida Keys normally would have to travel 5 hours from the Florida Keys, go to Miami, stay in a hotel overnight so that they can go to their appointment at 8 am. Instead, the veteran now can visit the Key West clinic and have his hearing aid adjusted by a VA audiologist who’s located in Miami; and it saves the entire trip.

The third one I will cite you has to do with the C&P [Compensation & Pension] exams. Now, a veteran living even out of the country can access a VA provider in Connecticut or some [other] state, using the encrypted video conferencing; and they can have the whole clinical evaluation for C&P completed using the video conferencing. These are some of the examples of how telehealth has been used very successfully.

Technologic and Educational Challenges

Dr. Agarwal. We have been a pioneer of telehealth. And with that, of course, all those challenges come into play. And we certainly have implementation challenges that include provider and patient education and their buy-in into the use of technology and providing services as well as the technology itself and some administrative issues. They can all be very closely linked.

You know, one illustrative example that I just cited earlier about video conferencing is one such example into the veteran’s home. It is very convenient.… We started to implement this home telemental health program a couple of years ago. But since then, about 108,000 veterans have accessed using the video conferencing technology; but fewer than 2,000 or so have done it from their own home. And that’s largely because the current video visit from home is quite cumbersome. It requires passwords for each visit. It requires that the veteran download VA-licensed software on their own device. And in addition, there are restrictions because of the availability of the broadband Internet connectivity, which is required for the video visit—more so in the rural areas.

Related: Preparing the Military Health System for the 21st Century

Our general counsel is reviewing and attempting to resolve state licensure requirements that have been raised by some states, because the veterans here receive care at home and outside of our VA brick-and-mortar facility, as well as the legality of VA providers potentially prescribing a controlled substance for a veteran at home without a prior in-person office visit.

But to overcome the provider challenges, the national telehealth training and resource center has been working on training the providers in the use of telehealth. Roughly 11,400 VA staff have been trained in the use of telehealth in FY14. We have currently 144 facility telehealth coordinators and more than 1,100 telehealth clinical technicians who assist with training and outreach for both VA staff and veteran patients.

Legal/Security Challenges

Dr. Agarwal. High-speed connectivity happens to be one of the key ones.… Using 4G services, I think, is going to be essential for every veteran regardless of rurality. And when these 4G services are not available, that certainly hinders the ability to provide telehealth to all veterans. Having the right security with full data encryption is essential so that we can protect the private health information of the veterans.

But unfortunately, at this time, there is not an easy way to do that. I think a lot of innovation is required so that we can make it much easier for the veterans with 1-button access, both for the veterans as well as for the providers. And that’s going to require significant effort in the grid technology as well as overcoming certain legal requirements.

What Is Driving Telehealth?

Dr. Agarwal. The real driver here has to be the veterans’ needs, not the needs of telehealth nor the clinical services or operations. I think the whole goal here is that we must use technology to the extent possible. We have to move toward virtual access as the norm.

As much as possible, we should provide the virtual access in the veterans’ homes or wherever the veterans would like to receive their services. Make the connectivity as simple as possible for the veterans and move beyond the concept of the episodic visit so that the health information and self-care management tools are available to the veterans at all times. And that essentially needs to be the overarching strategy, and that should drive how we develop the technologies to provide the services.

Data Analysis

Dr. Agarwal. We have the general enrollee data. We look at access gaps in clinical services and the telehealth activity data for our program management and oversight as well as in developing an overarching strategy for the clinical services and telehealth services. It’s done somewhat in conjunction. And our outcome analysis shows that there has been significant reduction in admissions and bed days of care with the use of telehealth.

For example, in FY14, an analysis of 10,621 veterans who were newly enrolled in home telehealth with noninstitutional care needs and chronic care management categories had a decrease of about 54% of bed days of care. This was about a 32% decrease in the hospital admissions compared [with] the same patient data prior to the enrollment and home telehealth. The analysis of telemental health outcomes shows that there was a 35% reduction in acute psychiatric bed days of care for veterans receiving CBT [cognitive behavioral therapy] or the clinical video conferencing telemental health in FY14 when it was compared [with] the utilization in the prior year.

Telehealth Pilot Programs

Dr. Agarwal. I must admit that there are many more programs that begin in the facilities, but at the national level. The first one is the tele-ICU implementation, where VISN 23 is supporting VISN 15, 5 of the medical centers with clinical video teleconferencing capability for live interactive consults with ICU specialists; and it covers about 78 beds. VISN 10 is supporting VISN 7 in 7 of their medical centers, which covers about 72 beds.

Another program, which is in the pilot phase right now, is the telewound care pilot, which is being implemented in 6 VISNs and combines the use of home telehealth, clinical video teleconferencing, and store-and-forward telehealth technologies to create access to a continuum of wound care options across multiple patients and provider settings and locations, all with the goal of enhancing and improving wound care treatment and healing.… The initial phase has been that all the participating facilities have been identified, and some of the operations manuals have been developed.

Related: Acting Surgeon General Confident in Battle Against Tobacco, Ebola, and Preventable Diseases

The third quarter of this year, we will have a completion of the operations manual Provider Training and Treatment Template. The local sites are also working on the infrastructure and knowledge base so that this project can be completed by FY15.

And the last highlight that I’ll mention, which is in its very early stages, is a low-acuity/low-intensity pilot with the focus on health promotion and health prevention behaviors, such as tobacco cessation, weight management, and newly diagnosed but stable veterans with diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart failure, using a web-based browser technology.

VA Telehealth Leadership

Dr. Agarwal. Overall, when we start to look at the monumental impact of technology on other industries, such as banking, shopping, travel, and even personal communications, the emerging technologies continue to change the overall landscape of all these environments. This is an exciting time to be in the health care industry, because I think we have lagged somewhat behind in using technology. But as we look forward, the consumer-driven health care is going to become the norm.

As you know, VA has long been a pioneer with electronic medical records and with virtual modalities, such as telehealth both in the home and in the community, the use of patient web portals, such as My HealtheVet, secure messaging for various apps, kiosks; and we remain on the forefront of developing and utilizing these approaches to enhance health care delivery.

We all know that health care in the U.S. is complex and fragmented. VA is looking to become the benchmark in U.S. health care delivery, aiding in the transformation of the delivery of services for veterans and families, focusing on unified, integrated, and personalized virtual services that seamlessly connect them with the state-of-the-art health care system.

1. Darkins A. A message from the acting chief consultant: telemedicine grows throughout VHA. Telemedicine News. 2001;1(1):1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.telehealth.va.gov/newsletter/2001/040201-newsletter_spring_01.pdf. Published April 2, 2001. Accessed June 23, 2015.

1. Darkins A. A message from the acting chief consultant: telemedicine grows throughout VHA. Telemedicine News. 2001;1(1):1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.telehealth.va.gov/newsletter/2001/040201-newsletter_spring_01.pdf. Published April 2, 2001. Accessed June 23, 2015.

Understanding Hematuria: Causes

Q) I have been treating a 60-year-old man with a long history of microscopic hematuria and waxing/waning proteinuria. What could be the cause of his hematuria?

Hematuria is a consequence of erythrocytes, or red blood cells (RBCs), in the urine. This can cause a visible change in color, considered gross or macroscopic hematuria; or the blood may only be visible under microscopy or by urine dipstick (referred to as microscopic hematuria).

Both findings are followed up with urinalysis to quantify erythrocytes, protein, and presence of casts and to review RBC morphology. This information will assist in determining if the hematuria is glomerular or nonglomerular in origin.1

The examination and treatment plan for nonglomerular hematuria will focus on urinary tract diseases. If the patient is found to have glomerular hematuria, the focus will be on diseases of the kidney. A thorough history and physical should be performed in addition to urinalysis.

Glomerular disease is suggested in those with micro- or macroscopic proteinuria, proteinuria > 1 g/24h, or an absence of casts. Our index patient has microscopic hematuria and “waxing/waning” (unquantified) proteinuria, suggesting glomerular origin.

There are a number of renal causes for glomerular bleeding, including primary glomerulonephritis, multisystem autoimmune disease, and hereditary or infective glomerulonephritis.2 Renal biopsy is recommended for patients who have hypertension, proteinuria, and hematuria, to determine the cause and thus determine the appropriate treatment.

Amy L. Hazel, RN, MSN, CNP

Kidney & Hypertension Consultants, Canton, Ohio

REFERENCES

1. Greenberg A. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

2. Barratt J, Feehally J. IgA nephropathy [disease of the month]. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7): 2088-2097.

Q) I have been treating a 60-year-old man with a long history of microscopic hematuria and waxing/waning proteinuria. What could be the cause of his hematuria?

Hematuria is a consequence of erythrocytes, or red blood cells (RBCs), in the urine. This can cause a visible change in color, considered gross or macroscopic hematuria; or the blood may only be visible under microscopy or by urine dipstick (referred to as microscopic hematuria).

Both findings are followed up with urinalysis to quantify erythrocytes, protein, and presence of casts and to review RBC morphology. This information will assist in determining if the hematuria is glomerular or nonglomerular in origin.1

The examination and treatment plan for nonglomerular hematuria will focus on urinary tract diseases. If the patient is found to have glomerular hematuria, the focus will be on diseases of the kidney. A thorough history and physical should be performed in addition to urinalysis.

Glomerular disease is suggested in those with micro- or macroscopic proteinuria, proteinuria > 1 g/24h, or an absence of casts. Our index patient has microscopic hematuria and “waxing/waning” (unquantified) proteinuria, suggesting glomerular origin.

There are a number of renal causes for glomerular bleeding, including primary glomerulonephritis, multisystem autoimmune disease, and hereditary or infective glomerulonephritis.2 Renal biopsy is recommended for patients who have hypertension, proteinuria, and hematuria, to determine the cause and thus determine the appropriate treatment.

Amy L. Hazel, RN, MSN, CNP

Kidney & Hypertension Consultants, Canton, Ohio

REFERENCES

1. Greenberg A. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

2. Barratt J, Feehally J. IgA nephropathy [disease of the month]. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7): 2088-2097.

Q) I have been treating a 60-year-old man with a long history of microscopic hematuria and waxing/waning proteinuria. What could be the cause of his hematuria?

Hematuria is a consequence of erythrocytes, or red blood cells (RBCs), in the urine. This can cause a visible change in color, considered gross or macroscopic hematuria; or the blood may only be visible under microscopy or by urine dipstick (referred to as microscopic hematuria).

Both findings are followed up with urinalysis to quantify erythrocytes, protein, and presence of casts and to review RBC morphology. This information will assist in determining if the hematuria is glomerular or nonglomerular in origin.1

The examination and treatment plan for nonglomerular hematuria will focus on urinary tract diseases. If the patient is found to have glomerular hematuria, the focus will be on diseases of the kidney. A thorough history and physical should be performed in addition to urinalysis.

Glomerular disease is suggested in those with micro- or macroscopic proteinuria, proteinuria > 1 g/24h, or an absence of casts. Our index patient has microscopic hematuria and “waxing/waning” (unquantified) proteinuria, suggesting glomerular origin.

There are a number of renal causes for glomerular bleeding, including primary glomerulonephritis, multisystem autoimmune disease, and hereditary or infective glomerulonephritis.2 Renal biopsy is recommended for patients who have hypertension, proteinuria, and hematuria, to determine the cause and thus determine the appropriate treatment.

Amy L. Hazel, RN, MSN, CNP

Kidney & Hypertension Consultants, Canton, Ohio

REFERENCES

1. Greenberg A. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

2. Barratt J, Feehally J. IgA nephropathy [disease of the month]. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7): 2088-2097.

Understanding Hematuria: IgA Nephropathy

Q) My hematuria patient had more significant proteinuria recently, so the nephrologist sent him for kidney biopsy. It was read as IgA nephropathy: “classic mesangial staining on IF with moderate-advanced chronic injury (15/32 gloms globally sclerosed, 40% IFTA, mild arteriosclerosis).” What exactly does this mean, and what is IgA nephropathy?

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy is the most common type of glomerulonephritis; up to 40% of patients with IgA nephropathy develop end-stage renal disease within 20 years of diagnosis. More common in men, IgA nephropathy is usually diagnosed in people in their second or third decades of life.2,3

Considered an autoimmune disease, IgA nephropathy typically presents with macroscopic or gross hematuria that occurs within 24 hours of the onset of an upper respiratory infection (URI). The hematuria typically resolves quickly, in one to three days. An individual bacterial or viral element has not yet been identified.