User login

BNP testing improves outcomes in evaluation of dyspnea

Data on treating bronchiolitis severity limited

How Motivational Interviewing Helps Patients with Diabetes

In 2019, 30.3 million US adults were reported to have diabetes—an epidemic according to some public health experts.1,2 Even more sobering, an estimated 84.1 million (or more than 1 in 3) American adults have prediabetes.1 Diabetes is associated with multiple complications, including an increased risk for heart disease or stroke.3 In 2015, it was the seventh leading cause of death and a major cause of kidney failure, lower limb amputations, stroke, and blindness.2,4

As clinicians we often ask ourselves, “How can I help my patients become more effective managers of their diabetes, so that they can maximize their quality of life over both the short and long term?” Unfortunately, management of diabetes is fraught with difficulty, both for the provider and the patient. Medications for glycemic control can be expensive and inconvenient and can have adverse effects—all of which may lead to inconsistent adherence. Lifestyle changes—including diet, regular physical activity, exercise, and weight management—are important low-risk interventions that help patients maintain glycemic values and reduce the risk for diabetic complications. However, some patients may find it difficult to make or are ambivalent to behavioral change.

These patients may benefit from having structured verbal encouragement—such as motivational interviewing (MI)—incorporated into their visits. The following discussion will explain how MI can be an effective communication tool for encouraging patients with diabetes or prediabetes to make important behavioral changes and improve health outcomes.

Q What is MI?

First created by William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick in the 1980s as a counseling method to help patients with substance use disorders, MI was eventually expanded to address other clinical challenges, including tobacco cessation, weight management, and diabetes care. MI helps patients identify their motivations and goals to improve long-term outcomes and work through any ambivalence to change. It utilizes an empathic approach with open-ended questions.5 This helps reduce the resistance frequently encountered during an average “lecture-style” interaction and facilitates a collaborative relationship that empowers the patient to make positive lifestyle changes.

MI affirms the patient’s experience while exploring any discrepancies between goals and actions. Two important components for conducting MI are (1) verbally reflecting the patient’s motivations and thoughts about change and (2) allowing the patient to “voice the arguments for change.”6 These components help the patient take ownership of the overarching goal for behavioral change and in the development of an action plan.

MI involves 4 primary processes: engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning (defined in the Table).7 MI begins with building rapport and a trusting relationship by engaging with empathic responses that reflect the patient’s concerns and focusing on what is important to him or her. The clinician should evoke the patient’s reasons and motivations for change. During the planning process, the clinician highlights the salient points of the conversation and works with the patient to identify an action he or she could take as a first step toward change.7

Table

Motivational Interviewing Processes

Engaging: Demonstrating empathy |

Focusing: Identifying what is important to the patient |

Evoking: Eliciting patient’s internal motivations for change |

Planning: Reinforcing the patient’s commitment to change |

Source: Arkowitz H, et al. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. 2015. 7

Continue to: Q How can I use MI with my patients with diabetes?

Q How can I use MI with my patients with diabetes?

MI can be used in a variety of clinical settings, including primary care and behavioral health, and can be effective when employed even in short periods of time.8,9 This communication style can be incorporated into regular follow-up appointments to help the clinician and the patient work toward better glycemic control and improved long-term outcomes.

For clinicians who are new users of MI, consider the mnemonic OARS (Open-ended questions, Affirmations, accurate empathic Reflections, Summarizing) to utilize the core components of MI.10 The OARS techniques are vital MI tools that can help the clinician explore the patient’s motivation for pursuing change, and they help the clinician recognize and appreciate the patient’s perspective on the challenges of initiating change.10 The following sample conversation illustrates how OARS can be used.

Open-ended question:

Clinician: What do you think are the greatest challenges when it comes to controlling your diabetes?

Patient: It’s just so frustrating, I keep avoiding bad food and trying to eat healthy, but my sugar still goes up.

Affirmations:

Clinician: Thank you for sharing that with me. It sounds like you are persistent and have been working hard to make healthier choices.

Patient: Yes, but I’m so tired of trying. It just doesn’t seem to work.

Accurate empathic reflections:

Clinician: It is important for you to control your diabetes, but you feel discouraged by the results that you’ve seen.

Patient: Yeah, I just don’t know what else to do to make my sugar better.

Continue to: Summarizing

Summarizing:

Clinician: You’ve said that controlling your blood sugar is important to you and that you’ve tried eating healthily, but it just isn’t working well enough. It sounds like you are ready to explore alternatives that might help you gain better control of the situation. Is that right?

Patient: Well, yes, it is.

Here the patient recognizes the need for help in controlling his or her diabetes, and the clinician can then move the conversation to additional treatment options, such as medication changes or support group intervention. Using OARS, the provider can focus on what is important to the patient and evaluate any discrepancies between the patient’s goals and actions.

Q Does the research support MI for patients with diabetes?

Many studies have evaluated the efficacy of MI on behavioral change and health care–related outcomes.8,11-15 Since its inception, MI has shown great promise in addictive behavior modification.16 Multiple studies also show support for its beneficial effect on weight management as well as on physical activity level, which are 2 factors strongly associated with improved outcomes in patients with prediabetes and diabetes.8,11-15,17 In a 2017 meta-analysis of MI for patients with obesity, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes, Phillips and Guarnaccia found significant support for behavioral change leading to improvements in quantifiable medical measurements.18

Systematic reviews of MI in health care settings have produced some conflicting findings. While there is evidence for the usefulness of MI in bringing about positive lifestyle changes, data supporting the effective use of MI in specific diabetes-related outcomes (eg, A1C levels) have been less robust.8,11-15,19 However, this is a particularly challenging area of study due in part to limitations of research designs and the inherent difficulties in assuring high-quality, consistent MI approaches. Despite these limitations, MI has significant positive results in improving patient adherence to treatment regimens.9,16,20,21

Conclusion

MI is a promising method that empowers patients to make modifications to their lifestyle choices, work through ambivalence, and better align goals with actions. Although the data on patient outcomes is inconclusive, evidence suggests that MI conducted across appointments holds benefit and that it is even more effective when combined with additional nonpharmacologic techniques, such as cognitive behavioral therapy.17,22 Additionally, research suggests that MI strengthens the clinician-patient relationship, with patients reporting greater empathy from their clinicians and overall satisfaction with interactions.23 Improved communication and mutual respect in clinician-patient interactions help maintain the therapeutic alliance for the future. For additional guidance and resources on MI, visit the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers website at motivationalinterviewing.org.

1. CDC. About diabetes. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/diabetes.html. Reviewed August 6, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019.

2. World Health Organization. Diabetes. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Published October 3, 2018. Accessed December 2, 2019.

3. CDC. Put the brakes on diabetes complications. www.cdc.gov/features/preventing-diabetes-complications/index.html. Reviewed October 21, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019.

4. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2019.

5. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23(4):325-334.

6. Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527-537.

7. Arkowitz H, Miller WR, Rollnick S, eds. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

8. VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37(4):768-780.

9. Palacio A, Garay D, Langer B, et al. Motivational interviewing improves medication adherence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(8):929-940.

10. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

11. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

12. Frost H, Campbell P, Maxwell M, et al. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204890.

13. Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(5):843-861.

14. Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305-312.

15. Hardcastle S, Taylor A, Bailey M, Castle R. A randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness of a primary health care based counselling intervention on physical activity, diet and CHD risk factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2008:70(1):31-39.

16. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91-111.

17. Morton K, Beauchamp M, Prothero A, et al. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing for health behaviour change in primary care settings: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(2):205-223.

18. Phillips AS, Guarnaccia CA. Self-determination theory and motivational interviewing interventions for type 2 diabetes prevention and treatment: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2017:135910531773760.

19. Mathiesen AS, Egerod I, Jensen T, et al. Psychosocial interventions for reducing diabetes distress in vulnerable people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;12:19-33.

20. Skolasky RL, Maggard AM, Wegener ST, Riley LH 3rd. Telephone-based intervention to improve rehabilitation engagement after spinal stenosis surgery: a prospective lagged controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(1):21-30.

21. Schaefer MR, Kavookjian J. The impact of motivational interviewing on adherence and symptom severity in adolescents and young adults with chronic illness: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2190-2199.

22. Barrett, S, Begg, S, O’Halloran, P, et al. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy for lifestyle mediators of overweight and obesity in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1160.

23. Wagoner ST, Kavookjian J. The influence of motivational interviewing on patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(8):659-666.

In 2019, 30.3 million US adults were reported to have diabetes—an epidemic according to some public health experts.1,2 Even more sobering, an estimated 84.1 million (or more than 1 in 3) American adults have prediabetes.1 Diabetes is associated with multiple complications, including an increased risk for heart disease or stroke.3 In 2015, it was the seventh leading cause of death and a major cause of kidney failure, lower limb amputations, stroke, and blindness.2,4

As clinicians we often ask ourselves, “How can I help my patients become more effective managers of their diabetes, so that they can maximize their quality of life over both the short and long term?” Unfortunately, management of diabetes is fraught with difficulty, both for the provider and the patient. Medications for glycemic control can be expensive and inconvenient and can have adverse effects—all of which may lead to inconsistent adherence. Lifestyle changes—including diet, regular physical activity, exercise, and weight management—are important low-risk interventions that help patients maintain glycemic values and reduce the risk for diabetic complications. However, some patients may find it difficult to make or are ambivalent to behavioral change.

These patients may benefit from having structured verbal encouragement—such as motivational interviewing (MI)—incorporated into their visits. The following discussion will explain how MI can be an effective communication tool for encouraging patients with diabetes or prediabetes to make important behavioral changes and improve health outcomes.

Q What is MI?

First created by William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick in the 1980s as a counseling method to help patients with substance use disorders, MI was eventually expanded to address other clinical challenges, including tobacco cessation, weight management, and diabetes care. MI helps patients identify their motivations and goals to improve long-term outcomes and work through any ambivalence to change. It utilizes an empathic approach with open-ended questions.5 This helps reduce the resistance frequently encountered during an average “lecture-style” interaction and facilitates a collaborative relationship that empowers the patient to make positive lifestyle changes.

MI affirms the patient’s experience while exploring any discrepancies between goals and actions. Two important components for conducting MI are (1) verbally reflecting the patient’s motivations and thoughts about change and (2) allowing the patient to “voice the arguments for change.”6 These components help the patient take ownership of the overarching goal for behavioral change and in the development of an action plan.

MI involves 4 primary processes: engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning (defined in the Table).7 MI begins with building rapport and a trusting relationship by engaging with empathic responses that reflect the patient’s concerns and focusing on what is important to him or her. The clinician should evoke the patient’s reasons and motivations for change. During the planning process, the clinician highlights the salient points of the conversation and works with the patient to identify an action he or she could take as a first step toward change.7

Table

Motivational Interviewing Processes

Engaging: Demonstrating empathy |

Focusing: Identifying what is important to the patient |

Evoking: Eliciting patient’s internal motivations for change |

Planning: Reinforcing the patient’s commitment to change |

Source: Arkowitz H, et al. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. 2015. 7

Continue to: Q How can I use MI with my patients with diabetes?

Q How can I use MI with my patients with diabetes?

MI can be used in a variety of clinical settings, including primary care and behavioral health, and can be effective when employed even in short periods of time.8,9 This communication style can be incorporated into regular follow-up appointments to help the clinician and the patient work toward better glycemic control and improved long-term outcomes.

For clinicians who are new users of MI, consider the mnemonic OARS (Open-ended questions, Affirmations, accurate empathic Reflections, Summarizing) to utilize the core components of MI.10 The OARS techniques are vital MI tools that can help the clinician explore the patient’s motivation for pursuing change, and they help the clinician recognize and appreciate the patient’s perspective on the challenges of initiating change.10 The following sample conversation illustrates how OARS can be used.

Open-ended question:

Clinician: What do you think are the greatest challenges when it comes to controlling your diabetes?

Patient: It’s just so frustrating, I keep avoiding bad food and trying to eat healthy, but my sugar still goes up.

Affirmations:

Clinician: Thank you for sharing that with me. It sounds like you are persistent and have been working hard to make healthier choices.

Patient: Yes, but I’m so tired of trying. It just doesn’t seem to work.

Accurate empathic reflections:

Clinician: It is important for you to control your diabetes, but you feel discouraged by the results that you’ve seen.

Patient: Yeah, I just don’t know what else to do to make my sugar better.

Continue to: Summarizing

Summarizing:

Clinician: You’ve said that controlling your blood sugar is important to you and that you’ve tried eating healthily, but it just isn’t working well enough. It sounds like you are ready to explore alternatives that might help you gain better control of the situation. Is that right?

Patient: Well, yes, it is.

Here the patient recognizes the need for help in controlling his or her diabetes, and the clinician can then move the conversation to additional treatment options, such as medication changes or support group intervention. Using OARS, the provider can focus on what is important to the patient and evaluate any discrepancies between the patient’s goals and actions.

Q Does the research support MI for patients with diabetes?

Many studies have evaluated the efficacy of MI on behavioral change and health care–related outcomes.8,11-15 Since its inception, MI has shown great promise in addictive behavior modification.16 Multiple studies also show support for its beneficial effect on weight management as well as on physical activity level, which are 2 factors strongly associated with improved outcomes in patients with prediabetes and diabetes.8,11-15,17 In a 2017 meta-analysis of MI for patients with obesity, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes, Phillips and Guarnaccia found significant support for behavioral change leading to improvements in quantifiable medical measurements.18

Systematic reviews of MI in health care settings have produced some conflicting findings. While there is evidence for the usefulness of MI in bringing about positive lifestyle changes, data supporting the effective use of MI in specific diabetes-related outcomes (eg, A1C levels) have been less robust.8,11-15,19 However, this is a particularly challenging area of study due in part to limitations of research designs and the inherent difficulties in assuring high-quality, consistent MI approaches. Despite these limitations, MI has significant positive results in improving patient adherence to treatment regimens.9,16,20,21

Conclusion

MI is a promising method that empowers patients to make modifications to their lifestyle choices, work through ambivalence, and better align goals with actions. Although the data on patient outcomes is inconclusive, evidence suggests that MI conducted across appointments holds benefit and that it is even more effective when combined with additional nonpharmacologic techniques, such as cognitive behavioral therapy.17,22 Additionally, research suggests that MI strengthens the clinician-patient relationship, with patients reporting greater empathy from their clinicians and overall satisfaction with interactions.23 Improved communication and mutual respect in clinician-patient interactions help maintain the therapeutic alliance for the future. For additional guidance and resources on MI, visit the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers website at motivationalinterviewing.org.

In 2019, 30.3 million US adults were reported to have diabetes—an epidemic according to some public health experts.1,2 Even more sobering, an estimated 84.1 million (or more than 1 in 3) American adults have prediabetes.1 Diabetes is associated with multiple complications, including an increased risk for heart disease or stroke.3 In 2015, it was the seventh leading cause of death and a major cause of kidney failure, lower limb amputations, stroke, and blindness.2,4

As clinicians we often ask ourselves, “How can I help my patients become more effective managers of their diabetes, so that they can maximize their quality of life over both the short and long term?” Unfortunately, management of diabetes is fraught with difficulty, both for the provider and the patient. Medications for glycemic control can be expensive and inconvenient and can have adverse effects—all of which may lead to inconsistent adherence. Lifestyle changes—including diet, regular physical activity, exercise, and weight management—are important low-risk interventions that help patients maintain glycemic values and reduce the risk for diabetic complications. However, some patients may find it difficult to make or are ambivalent to behavioral change.

These patients may benefit from having structured verbal encouragement—such as motivational interviewing (MI)—incorporated into their visits. The following discussion will explain how MI can be an effective communication tool for encouraging patients with diabetes or prediabetes to make important behavioral changes and improve health outcomes.

Q What is MI?

First created by William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick in the 1980s as a counseling method to help patients with substance use disorders, MI was eventually expanded to address other clinical challenges, including tobacco cessation, weight management, and diabetes care. MI helps patients identify their motivations and goals to improve long-term outcomes and work through any ambivalence to change. It utilizes an empathic approach with open-ended questions.5 This helps reduce the resistance frequently encountered during an average “lecture-style” interaction and facilitates a collaborative relationship that empowers the patient to make positive lifestyle changes.

MI affirms the patient’s experience while exploring any discrepancies between goals and actions. Two important components for conducting MI are (1) verbally reflecting the patient’s motivations and thoughts about change and (2) allowing the patient to “voice the arguments for change.”6 These components help the patient take ownership of the overarching goal for behavioral change and in the development of an action plan.

MI involves 4 primary processes: engaging, focusing, evoking, and planning (defined in the Table).7 MI begins with building rapport and a trusting relationship by engaging with empathic responses that reflect the patient’s concerns and focusing on what is important to him or her. The clinician should evoke the patient’s reasons and motivations for change. During the planning process, the clinician highlights the salient points of the conversation and works with the patient to identify an action he or she could take as a first step toward change.7

Table

Motivational Interviewing Processes

Engaging: Demonstrating empathy |

Focusing: Identifying what is important to the patient |

Evoking: Eliciting patient’s internal motivations for change |

Planning: Reinforcing the patient’s commitment to change |

Source: Arkowitz H, et al. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. 2015. 7

Continue to: Q How can I use MI with my patients with diabetes?

Q How can I use MI with my patients with diabetes?

MI can be used in a variety of clinical settings, including primary care and behavioral health, and can be effective when employed even in short periods of time.8,9 This communication style can be incorporated into regular follow-up appointments to help the clinician and the patient work toward better glycemic control and improved long-term outcomes.

For clinicians who are new users of MI, consider the mnemonic OARS (Open-ended questions, Affirmations, accurate empathic Reflections, Summarizing) to utilize the core components of MI.10 The OARS techniques are vital MI tools that can help the clinician explore the patient’s motivation for pursuing change, and they help the clinician recognize and appreciate the patient’s perspective on the challenges of initiating change.10 The following sample conversation illustrates how OARS can be used.

Open-ended question:

Clinician: What do you think are the greatest challenges when it comes to controlling your diabetes?

Patient: It’s just so frustrating, I keep avoiding bad food and trying to eat healthy, but my sugar still goes up.

Affirmations:

Clinician: Thank you for sharing that with me. It sounds like you are persistent and have been working hard to make healthier choices.

Patient: Yes, but I’m so tired of trying. It just doesn’t seem to work.

Accurate empathic reflections:

Clinician: It is important for you to control your diabetes, but you feel discouraged by the results that you’ve seen.

Patient: Yeah, I just don’t know what else to do to make my sugar better.

Continue to: Summarizing

Summarizing:

Clinician: You’ve said that controlling your blood sugar is important to you and that you’ve tried eating healthily, but it just isn’t working well enough. It sounds like you are ready to explore alternatives that might help you gain better control of the situation. Is that right?

Patient: Well, yes, it is.

Here the patient recognizes the need for help in controlling his or her diabetes, and the clinician can then move the conversation to additional treatment options, such as medication changes or support group intervention. Using OARS, the provider can focus on what is important to the patient and evaluate any discrepancies between the patient’s goals and actions.

Q Does the research support MI for patients with diabetes?

Many studies have evaluated the efficacy of MI on behavioral change and health care–related outcomes.8,11-15 Since its inception, MI has shown great promise in addictive behavior modification.16 Multiple studies also show support for its beneficial effect on weight management as well as on physical activity level, which are 2 factors strongly associated with improved outcomes in patients with prediabetes and diabetes.8,11-15,17 In a 2017 meta-analysis of MI for patients with obesity, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes, Phillips and Guarnaccia found significant support for behavioral change leading to improvements in quantifiable medical measurements.18

Systematic reviews of MI in health care settings have produced some conflicting findings. While there is evidence for the usefulness of MI in bringing about positive lifestyle changes, data supporting the effective use of MI in specific diabetes-related outcomes (eg, A1C levels) have been less robust.8,11-15,19 However, this is a particularly challenging area of study due in part to limitations of research designs and the inherent difficulties in assuring high-quality, consistent MI approaches. Despite these limitations, MI has significant positive results in improving patient adherence to treatment regimens.9,16,20,21

Conclusion

MI is a promising method that empowers patients to make modifications to their lifestyle choices, work through ambivalence, and better align goals with actions. Although the data on patient outcomes is inconclusive, evidence suggests that MI conducted across appointments holds benefit and that it is even more effective when combined with additional nonpharmacologic techniques, such as cognitive behavioral therapy.17,22 Additionally, research suggests that MI strengthens the clinician-patient relationship, with patients reporting greater empathy from their clinicians and overall satisfaction with interactions.23 Improved communication and mutual respect in clinician-patient interactions help maintain the therapeutic alliance for the future. For additional guidance and resources on MI, visit the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers website at motivationalinterviewing.org.

1. CDC. About diabetes. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/diabetes.html. Reviewed August 6, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019.

2. World Health Organization. Diabetes. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Published October 3, 2018. Accessed December 2, 2019.

3. CDC. Put the brakes on diabetes complications. www.cdc.gov/features/preventing-diabetes-complications/index.html. Reviewed October 21, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019.

4. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2019.

5. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23(4):325-334.

6. Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527-537.

7. Arkowitz H, Miller WR, Rollnick S, eds. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

8. VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37(4):768-780.

9. Palacio A, Garay D, Langer B, et al. Motivational interviewing improves medication adherence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(8):929-940.

10. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

11. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

12. Frost H, Campbell P, Maxwell M, et al. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204890.

13. Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(5):843-861.

14. Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305-312.

15. Hardcastle S, Taylor A, Bailey M, Castle R. A randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness of a primary health care based counselling intervention on physical activity, diet and CHD risk factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2008:70(1):31-39.

16. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91-111.

17. Morton K, Beauchamp M, Prothero A, et al. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing for health behaviour change in primary care settings: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(2):205-223.

18. Phillips AS, Guarnaccia CA. Self-determination theory and motivational interviewing interventions for type 2 diabetes prevention and treatment: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2017:135910531773760.

19. Mathiesen AS, Egerod I, Jensen T, et al. Psychosocial interventions for reducing diabetes distress in vulnerable people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;12:19-33.

20. Skolasky RL, Maggard AM, Wegener ST, Riley LH 3rd. Telephone-based intervention to improve rehabilitation engagement after spinal stenosis surgery: a prospective lagged controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(1):21-30.

21. Schaefer MR, Kavookjian J. The impact of motivational interviewing on adherence and symptom severity in adolescents and young adults with chronic illness: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2190-2199.

22. Barrett, S, Begg, S, O’Halloran, P, et al. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy for lifestyle mediators of overweight and obesity in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1160.

23. Wagoner ST, Kavookjian J. The influence of motivational interviewing on patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(8):659-666.

1. CDC. About diabetes. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/diabetes.html. Reviewed August 6, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019.

2. World Health Organization. Diabetes. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Published October 3, 2018. Accessed December 2, 2019.

3. CDC. Put the brakes on diabetes complications. www.cdc.gov/features/preventing-diabetes-complications/index.html. Reviewed October 21, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019.

4. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2019.

5. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23(4):325-334.

6. Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527-537.

7. Arkowitz H, Miller WR, Rollnick S, eds. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

8. VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37(4):768-780.

9. Palacio A, Garay D, Langer B, et al. Motivational interviewing improves medication adherence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(8):929-940.

10. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

11. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

12. Frost H, Campbell P, Maxwell M, et al. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204890.

13. Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(5):843-861.

14. Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305-312.

15. Hardcastle S, Taylor A, Bailey M, Castle R. A randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness of a primary health care based counselling intervention on physical activity, diet and CHD risk factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2008:70(1):31-39.

16. Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91-111.

17. Morton K, Beauchamp M, Prothero A, et al. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing for health behaviour change in primary care settings: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(2):205-223.

18. Phillips AS, Guarnaccia CA. Self-determination theory and motivational interviewing interventions for type 2 diabetes prevention and treatment: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2017:135910531773760.

19. Mathiesen AS, Egerod I, Jensen T, et al. Psychosocial interventions for reducing diabetes distress in vulnerable people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;12:19-33.

20. Skolasky RL, Maggard AM, Wegener ST, Riley LH 3rd. Telephone-based intervention to improve rehabilitation engagement after spinal stenosis surgery: a prospective lagged controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(1):21-30.

21. Schaefer MR, Kavookjian J. The impact of motivational interviewing on adherence and symptom severity in adolescents and young adults with chronic illness: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2190-2199.

22. Barrett, S, Begg, S, O’Halloran, P, et al. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy for lifestyle mediators of overweight and obesity in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1160.

23. Wagoner ST, Kavookjian J. The influence of motivational interviewing on patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(8):659-666.

Monoclonal Antibodies in MS

A 19-year-old man was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 7 and is currently being treated with an infusible monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy. Early in the day, he receives an infusion at an outpatient clinic. That night, he begins to experience numbness and tingling in his right upper extremity, which prompts a visit to an urgent care clinic. There, the clinician administers IV fluids to the patient. After his symptoms improve, the patient is discharged home.

The next morning, he has a new onset of left-side shoulder and neck pain with a pulsating headache. The patient reports his symptoms to his primary care provider (PCP), who instructs him to visit the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and treatment of a possible infection.

EXAMINATION

The patient arrives at the ED with a 102.4°F fever, vomiting, cough, mild congestion, diaphoresis, generalized myalgias, and chills. He also reports depression and anxiety, saying that for the past 7 days, “I haven’t felt like my normal self.”

Medical history includes moderate persistent asthma that is not well controlled, status asthmaticus, and use of an electronic vaporizing device for inhaling nicotine and marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Besides mAb infusions, his medications include hydrocodone/acetaminophen, prochlorperazine, gabapentin, hydroxyzine, trazodone, albuterol, and montelukast.

Examination reveals vital signs within normal limits. Lab work confirms elevated white blood cell count and absolute neutrophil count. Chest x-ray shows diffuse bilateral interstitial and patchy airspace opacities. He is diagnosed with bilateral pneumonia and is admitted and started on an IV antibiotic.

Within 24 hours, a new chest x-ray shows worsening symptoms. CT of the chest with contrast reveals diffuse bilateral ground-glass and airspace opacities suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome; bilateral thickening of the pulmonary interstitium; trace bilateral pleural effusions; increased caliber of the main pulmonary artery; and mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy.

Subsequently, the patient developed sepsis and went into acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. He is transferred to the ICU, and pulmonology is consulted. A bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) reveals neutrophil predominance; fungal, bacterial, and viral cultures are negative. The patient is started on broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and high-dose IV steroids. After 4 days, he begins to improve and is transferred out of the ICU. He is discharged with oral steroids and antibiotics.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, the PCP and the ED provider identified risk factors that contributed to the patient’s pneumonia and its subsequent worsening to sepsis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory effect of mAb therapy increased the patient’s risk for infection and the severity of infection, which is why vigilant safety monitoring and surveillance is essential with mAb treatment.1 Bloodwork should be performed at least every 6 months and include a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel with differential, and JC virus antibody test. Additionally, urinalysis should be performed prior to every mAb infusion. All testing recommended in the package insert for the patient’s prescribed therapy should be performed.

The patient’s history of asthma and his chronic vaping predisposed him to respiratory infections. In mice studies, exposure to e-cigarette vapor has been shown to be cytotoxic to airway cells and to decrease macrophage and neutrophil antimicrobial function.2 Exposure also alters immunomodulating cytokines in the airway, increases inflammatory markers seen in BAL and serum samples, and increases the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus

TREATMENT AND PATIENT EDUCATION

The PCP’s treatment plan included patient education about the importance of infection control measures when receiving a mAb; this includes practicing good hand and environmental hygiene, maintaining vaccinations, avoiding or reducing exposure to individuals who have infections or colds, avoiding large crowds (especially during flu season), and following recommendations for nutrition and hydration. The PCP also discussed how to recognize the early signs and symptoms of an infection—and the need for vigilant safety monitoring. The PCP described available options for smoking cessation, including nicotine replacement products, prescription non-nicotine medications, behavioral therapy, and/or counseling (individual, group or telephone) and discussed the risks associated with consuming nicotine and/or marijuana/THC and using electronic vaporizing devices.

The PCP emphasized the importance of completing the entire course of the oral antibiotics prescribed at discharge. The patient and the PCP agreed to the following plan of care: appointments with a pulmonologist and a neurologist within the next 2 weeks, and follow-up visits with the

1. Celius EG. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: implications for disease-modifying therapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(suppl 201):34-36.

2. Hwang JH, Lyes M, Sladewski K, et al. Electronic cigarette inhalation alters innate immunity and airway cytokines while increasing the virulence of colonizing bacteria. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94(6):667-679.

A 19-year-old man was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 7 and is currently being treated with an infusible monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy. Early in the day, he receives an infusion at an outpatient clinic. That night, he begins to experience numbness and tingling in his right upper extremity, which prompts a visit to an urgent care clinic. There, the clinician administers IV fluids to the patient. After his symptoms improve, the patient is discharged home.

The next morning, he has a new onset of left-side shoulder and neck pain with a pulsating headache. The patient reports his symptoms to his primary care provider (PCP), who instructs him to visit the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and treatment of a possible infection.

EXAMINATION

The patient arrives at the ED with a 102.4°F fever, vomiting, cough, mild congestion, diaphoresis, generalized myalgias, and chills. He also reports depression and anxiety, saying that for the past 7 days, “I haven’t felt like my normal self.”

Medical history includes moderate persistent asthma that is not well controlled, status asthmaticus, and use of an electronic vaporizing device for inhaling nicotine and marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Besides mAb infusions, his medications include hydrocodone/acetaminophen, prochlorperazine, gabapentin, hydroxyzine, trazodone, albuterol, and montelukast.

Examination reveals vital signs within normal limits. Lab work confirms elevated white blood cell count and absolute neutrophil count. Chest x-ray shows diffuse bilateral interstitial and patchy airspace opacities. He is diagnosed with bilateral pneumonia and is admitted and started on an IV antibiotic.

Within 24 hours, a new chest x-ray shows worsening symptoms. CT of the chest with contrast reveals diffuse bilateral ground-glass and airspace opacities suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome; bilateral thickening of the pulmonary interstitium; trace bilateral pleural effusions; increased caliber of the main pulmonary artery; and mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy.

Subsequently, the patient developed sepsis and went into acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. He is transferred to the ICU, and pulmonology is consulted. A bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) reveals neutrophil predominance; fungal, bacterial, and viral cultures are negative. The patient is started on broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and high-dose IV steroids. After 4 days, he begins to improve and is transferred out of the ICU. He is discharged with oral steroids and antibiotics.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, the PCP and the ED provider identified risk factors that contributed to the patient’s pneumonia and its subsequent worsening to sepsis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory effect of mAb therapy increased the patient’s risk for infection and the severity of infection, which is why vigilant safety monitoring and surveillance is essential with mAb treatment.1 Bloodwork should be performed at least every 6 months and include a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel with differential, and JC virus antibody test. Additionally, urinalysis should be performed prior to every mAb infusion. All testing recommended in the package insert for the patient’s prescribed therapy should be performed.

The patient’s history of asthma and his chronic vaping predisposed him to respiratory infections. In mice studies, exposure to e-cigarette vapor has been shown to be cytotoxic to airway cells and to decrease macrophage and neutrophil antimicrobial function.2 Exposure also alters immunomodulating cytokines in the airway, increases inflammatory markers seen in BAL and serum samples, and increases the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus

TREATMENT AND PATIENT EDUCATION

The PCP’s treatment plan included patient education about the importance of infection control measures when receiving a mAb; this includes practicing good hand and environmental hygiene, maintaining vaccinations, avoiding or reducing exposure to individuals who have infections or colds, avoiding large crowds (especially during flu season), and following recommendations for nutrition and hydration. The PCP also discussed how to recognize the early signs and symptoms of an infection—and the need for vigilant safety monitoring. The PCP described available options for smoking cessation, including nicotine replacement products, prescription non-nicotine medications, behavioral therapy, and/or counseling (individual, group or telephone) and discussed the risks associated with consuming nicotine and/or marijuana/THC and using electronic vaporizing devices.

The PCP emphasized the importance of completing the entire course of the oral antibiotics prescribed at discharge. The patient and the PCP agreed to the following plan of care: appointments with a pulmonologist and a neurologist within the next 2 weeks, and follow-up visits with the

A 19-year-old man was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 7 and is currently being treated with an infusible monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy. Early in the day, he receives an infusion at an outpatient clinic. That night, he begins to experience numbness and tingling in his right upper extremity, which prompts a visit to an urgent care clinic. There, the clinician administers IV fluids to the patient. After his symptoms improve, the patient is discharged home.

The next morning, he has a new onset of left-side shoulder and neck pain with a pulsating headache. The patient reports his symptoms to his primary care provider (PCP), who instructs him to visit the emergency department (ED) for evaluation and treatment of a possible infection.

EXAMINATION

The patient arrives at the ED with a 102.4°F fever, vomiting, cough, mild congestion, diaphoresis, generalized myalgias, and chills. He also reports depression and anxiety, saying that for the past 7 days, “I haven’t felt like my normal self.”

Medical history includes moderate persistent asthma that is not well controlled, status asthmaticus, and use of an electronic vaporizing device for inhaling nicotine and marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Besides mAb infusions, his medications include hydrocodone/acetaminophen, prochlorperazine, gabapentin, hydroxyzine, trazodone, albuterol, and montelukast.

Examination reveals vital signs within normal limits. Lab work confirms elevated white blood cell count and absolute neutrophil count. Chest x-ray shows diffuse bilateral interstitial and patchy airspace opacities. He is diagnosed with bilateral pneumonia and is admitted and started on an IV antibiotic.

Within 24 hours, a new chest x-ray shows worsening symptoms. CT of the chest with contrast reveals diffuse bilateral ground-glass and airspace opacities suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome; bilateral thickening of the pulmonary interstitium; trace bilateral pleural effusions; increased caliber of the main pulmonary artery; and mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy.

Subsequently, the patient developed sepsis and went into acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. He is transferred to the ICU, and pulmonology is consulted. A bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) reveals neutrophil predominance; fungal, bacterial, and viral cultures are negative. The patient is started on broad-spectrum IV antibiotics and high-dose IV steroids. After 4 days, he begins to improve and is transferred out of the ICU. He is discharged with oral steroids and antibiotics.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, the PCP and the ED provider identified risk factors that contributed to the patient’s pneumonia and its subsequent worsening to sepsis and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory effect of mAb therapy increased the patient’s risk for infection and the severity of infection, which is why vigilant safety monitoring and surveillance is essential with mAb treatment.1 Bloodwork should be performed at least every 6 months and include a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel with differential, and JC virus antibody test. Additionally, urinalysis should be performed prior to every mAb infusion. All testing recommended in the package insert for the patient’s prescribed therapy should be performed.

The patient’s history of asthma and his chronic vaping predisposed him to respiratory infections. In mice studies, exposure to e-cigarette vapor has been shown to be cytotoxic to airway cells and to decrease macrophage and neutrophil antimicrobial function.2 Exposure also alters immunomodulating cytokines in the airway, increases inflammatory markers seen in BAL and serum samples, and increases the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus

TREATMENT AND PATIENT EDUCATION

The PCP’s treatment plan included patient education about the importance of infection control measures when receiving a mAb; this includes practicing good hand and environmental hygiene, maintaining vaccinations, avoiding or reducing exposure to individuals who have infections or colds, avoiding large crowds (especially during flu season), and following recommendations for nutrition and hydration. The PCP also discussed how to recognize the early signs and symptoms of an infection—and the need for vigilant safety monitoring. The PCP described available options for smoking cessation, including nicotine replacement products, prescription non-nicotine medications, behavioral therapy, and/or counseling (individual, group or telephone) and discussed the risks associated with consuming nicotine and/or marijuana/THC and using electronic vaporizing devices.

The PCP emphasized the importance of completing the entire course of the oral antibiotics prescribed at discharge. The patient and the PCP agreed to the following plan of care: appointments with a pulmonologist and a neurologist within the next 2 weeks, and follow-up visits with the

1. Celius EG. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: implications for disease-modifying therapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(suppl 201):34-36.

2. Hwang JH, Lyes M, Sladewski K, et al. Electronic cigarette inhalation alters innate immunity and airway cytokines while increasing the virulence of colonizing bacteria. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94(6):667-679.

1. Celius EG. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: implications for disease-modifying therapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(suppl 201):34-36.

2. Hwang JH, Lyes M, Sladewski K, et al. Electronic cigarette inhalation alters innate immunity and airway cytokines while increasing the virulence of colonizing bacteria. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94(6):667-679.

Proteinuria and Albuminuria: What’s the Difference?

Q)What exactly is the difference between the protein-to-creatinine ratio and the microalbumin in the lab report? How do they compare?

For the non-nephrology provider, the options for evaluating urine protein or albumin can seem confusing. The first thing to understand is the importance of assessing for proteinuria, an established marker for chronic kidney disease (CKD). Higher protein levels are associated with more rapid progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease and increased risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in both the nondiabetic and diabetic populations. Monitoring proteinuria levels can also aid in evaluating response to treatment.1

Proteinuria and albuminuria are not the same thing. Proteinuria indicates an elevated presence of protein in the urine (normal excretion should be < 150 mg/d), while al

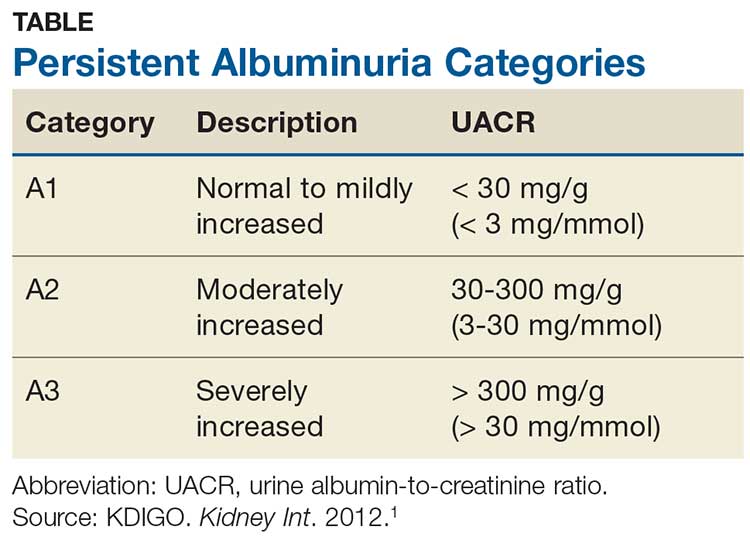

Albuminuria, without or with a reduction in estimated GFR (eGFR), lasting > 3 months is considered a marker of kidney damage. There are 3 categories of persistent albuminuria (see Table).1 Staging of CKD depends on both the eGFR and the albuminuria category; the results affect treatment considerations.

While there are several ways to assess for proteinuria, their accuracy varies. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline on the evaluation and management of CKD recommends the spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) as the preferred test for both initial and follow-up testing. While the UACR is typically reported as mg/g, it can also be reported in mg/mmol.1 Other options include the spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and a manual reading of a reagent strip (urine dipstick test) for total protein. Only if the first 2 choices are unavailable should a provider consider using a dipstick.

Reagent strip urinalysis may assess for protein or more specifically for albumin; tests for the latter are becoming more common. These tests are often used in a clinic setting, with results typically reported in the protein testing section. It is important to know which reagent strip urinalysis you are using (protein vs albumin) and how this is being reported. Additionally, test results depend on the urine concentration: Concentrated samples are more likely to indicate higher levels than may actually be present, while dilute samples may test negative (or positive for a trace amount) when in reality higher levels are present.

If a reagent strip urinalysis tests positive for protein, confirmatory testing is recommended using the UACR or the UPCR (if the former is not an option). A 24-hour urine screen for total protein excretion or an albumin excretion rate can be obtained if there are concerns about the accuracy of the previously discussed tests. A urine albumin excretion rate ≥ 30 mg/24 h corresponds to a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g (≥ 3 mg/mmol).1 Although 24-hour urine has been considered the gold standard, it is used less frequently today due to potential for improper sample collection, which can negatively affect accuracy, and inconvenience to patients.2

As a final note, if there is suspicion for nonalbumin proteinuria (eg, when increased plasma levels of low-molecular-weight proteins or immunoglobulin light chains are present), testing for specific urine proteins is recommended. This can include assessment with urine protein electrophoresis.1 —CS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN, FNKF

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

2. Ying T, Clayton P, Naresh C, Chadban S. Predictive value of spot versus 24-hour measures of proteinuria for death, end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease progression. BMC Nephrology. 2018;19:55.

Q)What exactly is the difference between the protein-to-creatinine ratio and the microalbumin in the lab report? How do they compare?

For the non-nephrology provider, the options for evaluating urine protein or albumin can seem confusing. The first thing to understand is the importance of assessing for proteinuria, an established marker for chronic kidney disease (CKD). Higher protein levels are associated with more rapid progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease and increased risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in both the nondiabetic and diabetic populations. Monitoring proteinuria levels can also aid in evaluating response to treatment.1

Proteinuria and albuminuria are not the same thing. Proteinuria indicates an elevated presence of protein in the urine (normal excretion should be < 150 mg/d), while al

Albuminuria, without or with a reduction in estimated GFR (eGFR), lasting > 3 months is considered a marker of kidney damage. There are 3 categories of persistent albuminuria (see Table).1 Staging of CKD depends on both the eGFR and the albuminuria category; the results affect treatment considerations.

While there are several ways to assess for proteinuria, their accuracy varies. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline on the evaluation and management of CKD recommends the spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) as the preferred test for both initial and follow-up testing. While the UACR is typically reported as mg/g, it can also be reported in mg/mmol.1 Other options include the spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and a manual reading of a reagent strip (urine dipstick test) for total protein. Only if the first 2 choices are unavailable should a provider consider using a dipstick.

Reagent strip urinalysis may assess for protein or more specifically for albumin; tests for the latter are becoming more common. These tests are often used in a clinic setting, with results typically reported in the protein testing section. It is important to know which reagent strip urinalysis you are using (protein vs albumin) and how this is being reported. Additionally, test results depend on the urine concentration: Concentrated samples are more likely to indicate higher levels than may actually be present, while dilute samples may test negative (or positive for a trace amount) when in reality higher levels are present.

If a reagent strip urinalysis tests positive for protein, confirmatory testing is recommended using the UACR or the UPCR (if the former is not an option). A 24-hour urine screen for total protein excretion or an albumin excretion rate can be obtained if there are concerns about the accuracy of the previously discussed tests. A urine albumin excretion rate ≥ 30 mg/24 h corresponds to a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g (≥ 3 mg/mmol).1 Although 24-hour urine has been considered the gold standard, it is used less frequently today due to potential for improper sample collection, which can negatively affect accuracy, and inconvenience to patients.2

As a final note, if there is suspicion for nonalbumin proteinuria (eg, when increased plasma levels of low-molecular-weight proteins or immunoglobulin light chains are present), testing for specific urine proteins is recommended. This can include assessment with urine protein electrophoresis.1 —CS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN, FNKF

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

Q)What exactly is the difference between the protein-to-creatinine ratio and the microalbumin in the lab report? How do they compare?

For the non-nephrology provider, the options for evaluating urine protein or albumin can seem confusing. The first thing to understand is the importance of assessing for proteinuria, an established marker for chronic kidney disease (CKD). Higher protein levels are associated with more rapid progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease and increased risk for cardiovascular events and mortality in both the nondiabetic and diabetic populations. Monitoring proteinuria levels can also aid in evaluating response to treatment.1

Proteinuria and albuminuria are not the same thing. Proteinuria indicates an elevated presence of protein in the urine (normal excretion should be < 150 mg/d), while al

Albuminuria, without or with a reduction in estimated GFR (eGFR), lasting > 3 months is considered a marker of kidney damage. There are 3 categories of persistent albuminuria (see Table).1 Staging of CKD depends on both the eGFR and the albuminuria category; the results affect treatment considerations.

While there are several ways to assess for proteinuria, their accuracy varies. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline on the evaluation and management of CKD recommends the spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) as the preferred test for both initial and follow-up testing. While the UACR is typically reported as mg/g, it can also be reported in mg/mmol.1 Other options include the spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and a manual reading of a reagent strip (urine dipstick test) for total protein. Only if the first 2 choices are unavailable should a provider consider using a dipstick.

Reagent strip urinalysis may assess for protein or more specifically for albumin; tests for the latter are becoming more common. These tests are often used in a clinic setting, with results typically reported in the protein testing section. It is important to know which reagent strip urinalysis you are using (protein vs albumin) and how this is being reported. Additionally, test results depend on the urine concentration: Concentrated samples are more likely to indicate higher levels than may actually be present, while dilute samples may test negative (or positive for a trace amount) when in reality higher levels are present.

If a reagent strip urinalysis tests positive for protein, confirmatory testing is recommended using the UACR or the UPCR (if the former is not an option). A 24-hour urine screen for total protein excretion or an albumin excretion rate can be obtained if there are concerns about the accuracy of the previously discussed tests. A urine albumin excretion rate ≥ 30 mg/24 h corresponds to a UACR of ≥ 30 mg/g (≥ 3 mg/mmol).1 Although 24-hour urine has been considered the gold standard, it is used less frequently today due to potential for improper sample collection, which can negatively affect accuracy, and inconvenience to patients.2

As a final note, if there is suspicion for nonalbumin proteinuria (eg, when increased plasma levels of low-molecular-weight proteins or immunoglobulin light chains are present), testing for specific urine proteins is recommended. This can include assessment with urine protein electrophoresis.1 —CS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN, FNKF

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

2. Ying T, Clayton P, Naresh C, Chadban S. Predictive value of spot versus 24-hour measures of proteinuria for death, end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease progression. BMC Nephrology. 2018;19:55.

1. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1-150.

2. Ying T, Clayton P, Naresh C, Chadban S. Predictive value of spot versus 24-hour measures of proteinuria for death, end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease progression. BMC Nephrology. 2018;19:55.

Acute Kidney Injury: Treatment Depends on the Cause

Q)I have a patient with a discharge diagnosis of community-acquired acute kidney injury. What does this mean? What do I do now?

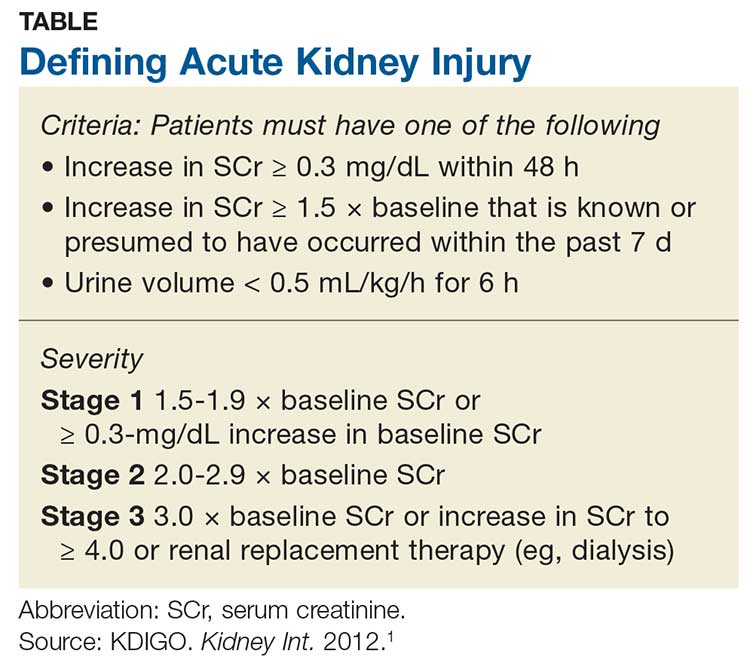

Acute kidney injury (AKI) refers to an abrupt decrease in kidney function that is possibly reversible or in which harm to the kidney can be modified.1,2 AKI encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions affecting the kidney—including acute renal failure, since even “failure” can sometimes be reversed.1 Criteria for AKI and its severity can be found in the Table.1

AKI can be either community-acquired (CA-AKI) or hospital-acquired (HA-AKI).1,2 In the United States, CA-AKI occurs less frequently than HA-AKI, although cases are likely underreported.1 Evaluation and management are similar for both.

The etiology of the AKI must be determined before treatment of the cause or precipitating factor can be attempted. Causes of AKI can be classified as prerenal (up to 70% of cases), intrinsic, or postrenal.1

Most AKI cases have a prerenal origin.3 Prerenal AKI occurs when there is inadequate blood flow to the kidneys, leading to a rise in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels. Reduced blood flow can be caused by

- Diuretic dosing

- Polypharmacy (diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs]/ angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], and/or NSAIDs are common culprits)

- Congestive heart failure exacerbation

- Volume depletion through vomiting or diarrhea

- Massive blood loss (trauma).3

Postrenal causes of AKI include any type of obstructive uropathy. Intrinsic causes involve any condition within the kidney, including interstitial nephritis or acute tubular necrosis. Use of antibiotics (eg, high-dose penicillin or vancomycin) is included in this category.

Obtaining an accurate medical history and examining the patient’s fluid status are critical. Although numerous novel biomarkers have been investigated for detection of AKI, none are yet in wide use. The primary assessment measures remain a serum panel to evaluate SCr and BUN levels; an electrolyte panel to assess for abnormalities; a complete blood count to assess for anemia caused by a less likely source; urinalysis; and imaging to assess for abnormalities or structural changes.

Urinalysis. Urine often holds the key to diagnosis of AKI. Notably in a prerenal injury, its specific gravity will be elevated, but the rest of the urine will likely be bland.3

Continue to: Urinalysis is helpful for...

Urinalysis is helpful for ruling out intrinsic causes of AKI. Patients with intrarenal AKI will have abnormal urine sediment; for example, red blood cell casts are found in glomerulonephritis; granular casts in cases of acute tubular necrosis; and white blood cell casts and eosinophils in acute interstitial nephritis.4

Imaging. The most commonly used imaging for AKI is retroperitoneal ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, which provides information on the size and shape of the kidneys and can detect stones or masses. It also detects the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, which can occur in postrenal injuries.

Currently, no definitive therapy or pharmacologic agent is approved for AKI; treatment focuses on reversing the cause of the injury. In the immediate aftermath of AKI, it is important to avoid potentially nephrotoxic medications, including NSAIDs. Minimize the use of diuretics and avoid ACEIs and ARB therapy; these can be reintroduced after lab results confirm that the AKI has resolved with a stabilized SCr.

Practice guidelines recommend prompt follow-up at 3 months in most cases of AKI.1 Providers should obtain a metabolic panel and perform a urinalysis to evaluate for chronic kidney disease (CKD), because almost one-third of patients with an AKI episode are newly classified with CKD in the following year.5 Earlier follow-up (< 3 months) is warranted if the patient has a significant comorbidity, such as congestive heart failure.1,2—CS

Christopher Sjoberg, CNN-NP

Idaho Nephrology Associates, Boise

Adjunct Faculty, Boise State University

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(suppl):1-138.

2. Palevsky PM, Liu KD, Brophy PD, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):649-672.

3. Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2012; 380(9843):756-766.

4. Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Disease. 7thed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

5. United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018.

Q)I have a patient with a discharge diagnosis of community-acquired acute kidney injury. What does this mean? What do I do now?

Acute kidney injury (AKI) refers to an abrupt decrease in kidney function that is possibly reversible or in which harm to the kidney can be modified.1,2 AKI encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions affecting the kidney—including acute renal failure, since even “failure” can sometimes be reversed.1 Criteria for AKI and its severity can be found in the Table.1

AKI can be either community-acquired (CA-AKI) or hospital-acquired (HA-AKI).1,2 In the United States, CA-AKI occurs less frequently than HA-AKI, although cases are likely underreported.1 Evaluation and management are similar for both.

The etiology of the AKI must be determined before treatment of the cause or precipitating factor can be attempted. Causes of AKI can be classified as prerenal (up to 70% of cases), intrinsic, or postrenal.1

Most AKI cases have a prerenal origin.3 Prerenal AKI occurs when there is inadequate blood flow to the kidneys, leading to a rise in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels. Reduced blood flow can be caused by

- Diuretic dosing

- Polypharmacy (diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs]/ angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], and/or NSAIDs are common culprits)

- Congestive heart failure exacerbation

- Volume depletion through vomiting or diarrhea

- Massive blood loss (trauma).3

Postrenal causes of AKI include any type of obstructive uropathy. Intrinsic causes involve any condition within the kidney, including interstitial nephritis or acute tubular necrosis. Use of antibiotics (eg, high-dose penicillin or vancomycin) is included in this category.

Obtaining an accurate medical history and examining the patient’s fluid status are critical. Although numerous novel biomarkers have been investigated for detection of AKI, none are yet in wide use. The primary assessment measures remain a serum panel to evaluate SCr and BUN levels; an electrolyte panel to assess for abnormalities; a complete blood count to assess for anemia caused by a less likely source; urinalysis; and imaging to assess for abnormalities or structural changes.

Urinalysis. Urine often holds the key to diagnosis of AKI. Notably in a prerenal injury, its specific gravity will be elevated, but the rest of the urine will likely be bland.3

Continue to: Urinalysis is helpful for...

Urinalysis is helpful for ruling out intrinsic causes of AKI. Patients with intrarenal AKI will have abnormal urine sediment; for example, red blood cell casts are found in glomerulonephritis; granular casts in cases of acute tubular necrosis; and white blood cell casts and eosinophils in acute interstitial nephritis.4

Imaging. The most commonly used imaging for AKI is retroperitoneal ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, which provides information on the size and shape of the kidneys and can detect stones or masses. It also detects the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, which can occur in postrenal injuries.

Currently, no definitive therapy or pharmacologic agent is approved for AKI; treatment focuses on reversing the cause of the injury. In the immediate aftermath of AKI, it is important to avoid potentially nephrotoxic medications, including NSAIDs. Minimize the use of diuretics and avoid ACEIs and ARB therapy; these can be reintroduced after lab results confirm that the AKI has resolved with a stabilized SCr.

Practice guidelines recommend prompt follow-up at 3 months in most cases of AKI.1 Providers should obtain a metabolic panel and perform a urinalysis to evaluate for chronic kidney disease (CKD), because almost one-third of patients with an AKI episode are newly classified with CKD in the following year.5 Earlier follow-up (< 3 months) is warranted if the patient has a significant comorbidity, such as congestive heart failure.1,2—CS

Christopher Sjoberg, CNN-NP

Idaho Nephrology Associates, Boise

Adjunct Faculty, Boise State University

Q)I have a patient with a discharge diagnosis of community-acquired acute kidney injury. What does this mean? What do I do now?

Acute kidney injury (AKI) refers to an abrupt decrease in kidney function that is possibly reversible or in which harm to the kidney can be modified.1,2 AKI encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions affecting the kidney—including acute renal failure, since even “failure” can sometimes be reversed.1 Criteria for AKI and its severity can be found in the Table.1

AKI can be either community-acquired (CA-AKI) or hospital-acquired (HA-AKI).1,2 In the United States, CA-AKI occurs less frequently than HA-AKI, although cases are likely underreported.1 Evaluation and management are similar for both.

The etiology of the AKI must be determined before treatment of the cause or precipitating factor can be attempted. Causes of AKI can be classified as prerenal (up to 70% of cases), intrinsic, or postrenal.1

Most AKI cases have a prerenal origin.3 Prerenal AKI occurs when there is inadequate blood flow to the kidneys, leading to a rise in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr) levels. Reduced blood flow can be caused by

- Diuretic dosing

- Polypharmacy (diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs]/ angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], and/or NSAIDs are common culprits)

- Congestive heart failure exacerbation

- Volume depletion through vomiting or diarrhea

- Massive blood loss (trauma).3

Postrenal causes of AKI include any type of obstructive uropathy. Intrinsic causes involve any condition within the kidney, including interstitial nephritis or acute tubular necrosis. Use of antibiotics (eg, high-dose penicillin or vancomycin) is included in this category.

Obtaining an accurate medical history and examining the patient’s fluid status are critical. Although numerous novel biomarkers have been investigated for detection of AKI, none are yet in wide use. The primary assessment measures remain a serum panel to evaluate SCr and BUN levels; an electrolyte panel to assess for abnormalities; a complete blood count to assess for anemia caused by a less likely source; urinalysis; and imaging to assess for abnormalities or structural changes.

Urinalysis. Urine often holds the key to diagnosis of AKI. Notably in a prerenal injury, its specific gravity will be elevated, but the rest of the urine will likely be bland.3

Continue to: Urinalysis is helpful for...

Urinalysis is helpful for ruling out intrinsic causes of AKI. Patients with intrarenal AKI will have abnormal urine sediment; for example, red blood cell casts are found in glomerulonephritis; granular casts in cases of acute tubular necrosis; and white blood cell casts and eosinophils in acute interstitial nephritis.4

Imaging. The most commonly used imaging for AKI is retroperitoneal ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, which provides information on the size and shape of the kidneys and can detect stones or masses. It also detects the presence or absence of hydronephrosis, which can occur in postrenal injuries.

Currently, no definitive therapy or pharmacologic agent is approved for AKI; treatment focuses on reversing the cause of the injury. In the immediate aftermath of AKI, it is important to avoid potentially nephrotoxic medications, including NSAIDs. Minimize the use of diuretics and avoid ACEIs and ARB therapy; these can be reintroduced after lab results confirm that the AKI has resolved with a stabilized SCr.

Practice guidelines recommend prompt follow-up at 3 months in most cases of AKI.1 Providers should obtain a metabolic panel and perform a urinalysis to evaluate for chronic kidney disease (CKD), because almost one-third of patients with an AKI episode are newly classified with CKD in the following year.5 Earlier follow-up (< 3 months) is warranted if the patient has a significant comorbidity, such as congestive heart failure.1,2—CS

Christopher Sjoberg, CNN-NP

Idaho Nephrology Associates, Boise

Adjunct Faculty, Boise State University