User login

Case Presentation. A 23-year-old male U.S. Army veteran with a history of alcohol use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) West Roxbury campus emergency department (ED) with epigastric abdominal pain in the setting of consuming alcohol. The patient had served in the infantry in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He consumed up to 12 alcoholic drinks per day (both beer and hard liquor) for the past 3 years and had been hospitalized 3 times previously; twice for alcohol detoxification and once for PTSD. He is a former tobacco smoker with fewer than 5 pack-years, he uses marijuana often and does not use IV drugs. In the ED, his physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 130 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/111 mm Hg. He was alert and oriented and had a mild tremor. The patient was diaphoretic with dry mucous membranes, tenderness to palpation in the epigastrium, and abdominal guarding. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed acute pancreatitis without necrosis. The patient received 1 L of normal saline and was admitted to the medical ward for presumed alcoholic pancreatitis.

► Rahul Ganatra, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dr. Weber, we care for many young people who drink more than they should and almost none of them end up with alcoholic pancreatitis. What are the relevant risk factors that make individuals like this patient more susceptible to alcoholic pancreatitis?

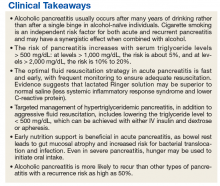

►Horst Christian Weber, MD, Gastroenterology Service, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. While we don’t have a good understanding of the precise mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis, we do know that in the U.S., alcohol consumption is responsible for about one-third of all cases.1 Acute pancreatitis in general may present with a wide range of disease severity. It is the most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalization,2 and the mortality of hospital inpatients with pancreatitis is about 5%.3,4 Therefore, acute pancreatitis represents a prevalent condition with a critical impact on morbidity and mortality. Alcoholic pancreatitis typically occurs after many years of heavy alcohol use, not after a single drinking

► Dr. Ganatra. At this point, the chemistry laboratory paged the admitting resident with the notification that the patient’s blood was grossly lipemic. Ultracentrifugation was performed to separate the lipid layer and his laboratory values result (Table). Notable abnormalities included polycythemia with a hemoglobin of 17.4 g/dL, hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mmol/L, normal renal function, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (AST 258 IU/L and ALT 153 IU/L, respectively), hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 2.7 mg/dL, and a serum alcohol level of 147 mg/dL. Due to anticipated requirement for a higher level of care, the patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU).

Dr. Breu, can you help us interpret this patient’s numerous laboratory abnormalities? Without yet having the triglyceride level available, how does the fact that the patient’s blood was lipemic affect our interpretation of his labs? What further workup is warranted?

► Anthony Breu, MD, Medical Service, VABHS, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. First, the positive alcohol level confirms a recent ingestion. Second, he has elevated transaminases with the AST greater than the ALT, which is consistent with alcoholic liver disease. While the initial assumption is that this patient has alcohol-induced pancreatitis, the elevations in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase may suggest gallstone pancreatitis, and the lipemic appearing serum could suggest triglyceride-mediated pancreatitis. If the patient does have elevated triglyceride levels, the sodium level may indicate pseudohyponatremia, a laboratory artifact seen if a dilution step is used. To further evaluate the patient, I would obtain a triglyceride level and a right upper quadrant ultrasound. Direct ion-selective electrode analysis of the sodium level can be done with a device used to measure blood gases to exclude pseudohyponatremia.

► Dr. Ganatra. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was obtained in the MICU, which showed hepatic steatosis and hepatomegaly to 19 cm, but no evidence of biliary obstruction by stones or sludge. The common bile duct measured 3.2 mm in diameter. A triglyceride level returned above assay at > 3,392 mg/dL. A review of the medical record revealed a triglyceride level of 105 mg/dL 16 months prior. The Gastroenterology Department was consulted.

Dr. Weber, we now have 2 etiologies for pancreatitis in this patient: alcohol and hypertriglyceridemia. How do each cause pancreatitis? Is it possible to determine in this case which one is the more likely driver?

► Dr. Weber. The mechanism for alcohol-induced pancreatitis is not fully known, but there are several hypotheses. One is that alcohol may increase the synthesis or activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes.6 Another is that metabolites of alcohol are directly toxic to the pancreas.6 Based on the epidemiologic observation that alcoholic pancreatitis usually happens in long-standing users, all we can say is that it is not very likely to be the effect of an acute insult. For hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, we believe the injury is due to the toxic effect of free fatty acids in the pancreas liberated by lipolysis of triglycerides by pancreatic lipases. Higher triglycerides are associated with higher risk, suggesting a dose-response relationship: This risk is not greatly increased until triglycerides exceed 500 mg/dL; above 1,000 mg/dL, the risk is about 5%, and above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is between 10% and 20%.7 In summary, we cannot really determine whether the alcohol or the triglycerides are the main cause of his pancreatitis, but given his markedly elevated triglycerides, he should be treated for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis.

►Dr. Ganatra. Dr. Breu, regardless of the underlying etiology, this patient requires treatment. What does the literature suggest as the best course of action regarding crystalloid administration in patients with acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. There are 2 issues to discuss regarding IV fluids in acute pancreatitis: choice of crystalloid and rate of administration. For the choice of IV fluid, lactated Ringer solution (LR) may be preferred over normal saline (NS). There are both pathophysiologic and evidence-based rationales for this choice. As Dr. Weber alluded to, trypsinogen activation is an important step in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and requires a low pH compartment. As most clinicians have experienced, NS may cause a metabolic acidosis; however, the use of LR may mitigate this. A 2011 randomized clinical trial showed that patients who received LR had less systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and lower C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 24 hours compared with patients who received NS.8 While these are surrogate outcomes, they, along with the theoretical basis, suggest LR is preferred.

Regarding rate, the key is fast and early.9 In my experience, internists often underdose IV rehydration within the first 12 to 24 hours, fail to change the rate based on clinical response, and leave patients on high rates too long. In a patient like this, a rate of 350 cc/h is a reasonable place to start. But, one must reassess response (ie, ensure there is a decrease in hematocrit and/or blood urea nitrogen) every 6 hours and increase the rate as needed. After the first 24 to 48 hours have passed, the rate should be lowered.

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient received 2 mg of IV hydromorphone and a 2 L bolus of LR. This was followed by a continuous infusion of LR at 200 cc/h. Dr. Weber, apart from the standard therapies for pancreatitis, what are our treatment options in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis?

►Dr. Weber. In the acute setting, IV insulin with or without dextrose is the most extensively studied therapy. Insulin rapidly decreases triglyceride levels by activating lipoprotein lipase and inhibiting hormone- sensitive lipase. The net effect is reduction in serum triglycerides available to be hydrolyzed to free fatty acids in the pancreas.7 For severe cases (ie, where acute pancreatitis is accompanied by hypocalcemia, lactic acidosis or a markedly elevated lipase), apheresis with therapeutic plasma exchange to more rapidly reduce triglyceride concentration is the preferred therapy. The goal is to reduce triglycerides to levels

►Dr. Ganatra. Due to the possibility that the patient would require apheresis, which was not available at the VABHS West Roxbury campus, the patient was transferred to an affiliate hospital. The patient was started on 10% dextrose at 300 cc/h and an IV insulin infusion. His triglycerides fell to < 500 mg/dL over the subsequent 48 hours, and ultimately, apheresis was not required. Enteral nutrition by nasogastric (NG) tube was initiated on hospital day 6. The patient’s hospital course was notable for acute respiratory distress syndrome that required intubation for 7 days, hyperbilirubinemia (with a peak bilirubin of 10.5 mg/dL), acute kidney injury (with a peak creatinine 4.7 mg/dL), fever without an identified infectious source, alcohol withdrawal syndrome that required phenobarbital, and delirium. Nine days later, he was transferred back to the VABHS West Roxbury campus. His condition stabilized, and he was transferred to the medical floor. On hospital day 14, the patient’s mental status improved, and he began tolerating oral nutrition.

Dr. Breu, over the years, the standard of care regarding when to start enteral nutrition in pancreatitis has changed considerably. This patient received enteral nutrition via NG tube but also had periods of being NPO (nothing by mouth) for up to 6 days. What is the current best practice for timing of initiating enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. It is true that the standard of care has changed and continues to evolve. Many decades ago, patients with acute pancreatitis would routinely undergo NG tube suction to reduce delivery of gastric contents to the duodenum, thereby decreasing pancreas activation, allowing it to rest.11 The NG tube also allowed for decompression of any ileus that had formed. Beginning in the 1970s, several clinical trials were performed, showing that NG tube suction was no better than simply making the patient NPO.12,13 More recently, we have begun to move toward earlier feeding. Again, there is a pathophysiologic rationale (bowel rest is associated with intestinal atrophy, predisposing to bacterial translocation and resulting infectious complications) and increasing evidence supporting this practice.9 Even in severe pancreatitis, hunger may be used to initiate oral intake.14

►Dr. Ganatra. On hospital day 16, the patient developed sudden-onset right-sided back and flank pain, and his hemoglobin dropped to 6.1 mg/dL, which required transfusion of packed red blood cells. He remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Dr. Weber, what are the major complications of acute pancreatitis, and when should we suspect them? Should we be worried about complications of pancreatitis in this patient?

►Dr. Weber. Organ failure in the acute setting can occur due to activation of cytokine cascades and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and is described by clinical and radiologic criteria called the Atlanta Classification.15 Apart from organ failure, the most serious complications of acute pancreatitis are necrosis of pancreatic tissue leading to walled-off pancreatic necrosis and the formation of peripancreatic fluid collections and pseudocysts, which occur in about 15% of patients with acute pancreatitis. These complications are serious because they can become infected, which portends a higher mortality and in some cases require surgical resection.

Other complications of acute pancreatitis include pseudoaneurysm formation, which is when a vessel bleeds into a pancreatic pseudocyst, and thromboses of the splenic, portal, or mesenteric veins. Thrombotic complications may occur in up to half of patients with pancreatic necrosis but are uncommon without some degree of necrosis.16 No necrosis was noted on this patient’s initial CT scan, so the probability of thrombosis is low. Also, as it takes several weeks for pseudocyst formation to occur, a bleeding pseudoaneurysm is unlikely at this early stage. Therefore, a complication of pancreatitis is unlikely in this patient, and evaluation for other causes of abdominal pain should be considered.

►Dr. Ganatra. A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained and revealed no evidence of complications or other acute pathology. His pain was managed conservatively, and hemoglobin remained stable. Over the next 5 days, the patient’s symptoms gradually resolved, his oral intake improved, and he was discharged home on gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily 19 days after admission. He declined psychiatry follow-up for his PTSD, and after discharge he did not keep his scheduled gastroenterology (GI) follow-up appointment. Four months later, the patient presented again with epigastric abdominal pain similar to his initial presentation. The patient had resumed drinking, stating that “alcohol is the only thing that helps [with the PTSD].” He had not been taking the gemfibrozil. He was admitted with a recurrent episode of pancreatitis; however, his triglycerides on admission were 119 mg/dL.

Dr. Weber, this patient’s triglycerides declined rapidly over a period of just 4 months with questionable adherence to gemfibrozil. However, he was admitted again with another episode of pancreatitis, this time in the setting of alcohol use alone without markedly elevated triglycerides. What do we know about recurrence risk for pancreatitis? Are some etiologies of pancreatitis more likely to present with recurrent attacks than are others?

►Dr. Weber. The rate of recurrence following an episode of acute pancreatitis varies according to the cause, but in general, about 20% to 30% of patients will experience a recurrence, and 5% to 10% will go on to develop chronic pancreatitis.17 Alcoholic pancreatitis does carry a higher risk of recurrence than pancreatitis due to other causes; the risk is as high as 50%. Not surprisingly, recurrence of acute pancreatitis increases risk for development of chronic pancreatitis. As this patient is a smoker, it is worth noting that smoking potentiates pancreatic damage from alcohol and increases the risk for both recurrent and chronic pancreatitis.5

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient was treated with IV hydromorphone and IV LR at 350 cc/h. Oral nutrition was begun immediately. He manifested no organ dysfunction, and his symptoms improved over the course of 48 hours. He was discharged home with psychiatry and GI follow-up scheduled. Dr. Breu and Dr. Weber, how should we counsel this patient to reduce his risk of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis in the future, and what options do we have for pharmacotherapy to decrease his risk?

►Dr. Breu. I’ll let Dr. Weber comment on mitigating the risk of hypertriglyceride-induced pancreatitis and reserve my comments to pharmacotherapy in alcohol use disorder. This patient may be a candidate for naltrexone therapy, either in oral or intramuscular formulations. Both have been showed to reduce the risk of returning to heavy drinking and may be particularly beneficial in those with a family history.18,19 Acamprosate is also an option.

►Dr. Weber. Data on recurrence risk in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis are limited, but there are case reports suggesting that a fatty diet and alcohol use are implicated in recurrence.20 I would counsel the patient on lifestyle modifications that are known to reduce this risk. I agree with Dr. Breu that devoting our efforts to helping him reduce or eliminate his alcohol consumption is the single most important thing we can do to reduce his risk for recurrent attacks. Since the patient reports that he drinks alcohol in order to cope with his PTSD, establishing care with a mental health provider to address this is of the utmost importance. In addition, smoking cessation and promoting medication adherence with gemfibrozil will also reduce risk for future episodes, but continued alcohol use is his strongest risk factor.

►Dr. Ganatra. After discharge, the patient engaged with outpatient psychiatry and GI. He still reports feeling that alcohol is the only thing that alleviates his PTSD and anxiety symptoms. He is not currently interested in pharmacotherapy for cessation of alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ivana Jankovic, MD, Matthew Lewis Chase, MD

1. Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27(4):286-290.

2. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3.

3. Cavallini G, Frulloni L, Bassi C, et al; ProInf-AISP Study Group. Prospective multicentre survey on acute pancreatitis in Italy (ProInf-AISP): results on 1005 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(3):205-211.

4. Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2379-2400.

5. Hartwig W, Werner J, Ryschich E, et al. Cigarette smoke enhances ethanol-induced pancreatic injury. Pancreas. 2000;21(3):272-278.

6. Chowdhury P, Gupta P. Pathophysiology of alcoholic pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(46):7421-7427.

7. Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195-203.

8. Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(8):710-717.e1.

9. Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1400-1415; 1416.

10. Preiss D, Tikkanen MJ, Welsh P, et al. Lipid-modifying therapies and risk of pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(8):804-811.

11. Nardi GL. Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1963;268(19):1065-1067.

12. Naeije R, Salingret E, Clumeck N, De Troyer A, Devis G. Is nasogastric suction necessary in acute pancreatitis? Br Med J. 1978;2(6138):659-660.

13. Levant JA, Secrist DM, Resin H, Sturdevant RA, Guth PH. Nasogastric suction in the treatment of alcoholic pancreatitis: a controlled study. JAMA. 1974;229(1):51-52.

14. Zhao XL, Zhu SF, Xue GJ, et al. Early oral refeeding based on hunger in moderate and severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):171-175.

15. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111.

16. Easler J, Muddana V, Furlan A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):854-862.

17. Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1096-1103.

18. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

19. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617-1625.

20. Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas. 1996;13(1):96-99.

Case Presentation. A 23-year-old male U.S. Army veteran with a history of alcohol use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) West Roxbury campus emergency department (ED) with epigastric abdominal pain in the setting of consuming alcohol. The patient had served in the infantry in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He consumed up to 12 alcoholic drinks per day (both beer and hard liquor) for the past 3 years and had been hospitalized 3 times previously; twice for alcohol detoxification and once for PTSD. He is a former tobacco smoker with fewer than 5 pack-years, he uses marijuana often and does not use IV drugs. In the ED, his physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 130 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/111 mm Hg. He was alert and oriented and had a mild tremor. The patient was diaphoretic with dry mucous membranes, tenderness to palpation in the epigastrium, and abdominal guarding. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed acute pancreatitis without necrosis. The patient received 1 L of normal saline and was admitted to the medical ward for presumed alcoholic pancreatitis.

► Rahul Ganatra, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dr. Weber, we care for many young people who drink more than they should and almost none of them end up with alcoholic pancreatitis. What are the relevant risk factors that make individuals like this patient more susceptible to alcoholic pancreatitis?

►Horst Christian Weber, MD, Gastroenterology Service, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. While we don’t have a good understanding of the precise mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis, we do know that in the U.S., alcohol consumption is responsible for about one-third of all cases.1 Acute pancreatitis in general may present with a wide range of disease severity. It is the most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalization,2 and the mortality of hospital inpatients with pancreatitis is about 5%.3,4 Therefore, acute pancreatitis represents a prevalent condition with a critical impact on morbidity and mortality. Alcoholic pancreatitis typically occurs after many years of heavy alcohol use, not after a single drinking

► Dr. Ganatra. At this point, the chemistry laboratory paged the admitting resident with the notification that the patient’s blood was grossly lipemic. Ultracentrifugation was performed to separate the lipid layer and his laboratory values result (Table). Notable abnormalities included polycythemia with a hemoglobin of 17.4 g/dL, hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mmol/L, normal renal function, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (AST 258 IU/L and ALT 153 IU/L, respectively), hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 2.7 mg/dL, and a serum alcohol level of 147 mg/dL. Due to anticipated requirement for a higher level of care, the patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU).

Dr. Breu, can you help us interpret this patient’s numerous laboratory abnormalities? Without yet having the triglyceride level available, how does the fact that the patient’s blood was lipemic affect our interpretation of his labs? What further workup is warranted?

► Anthony Breu, MD, Medical Service, VABHS, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. First, the positive alcohol level confirms a recent ingestion. Second, he has elevated transaminases with the AST greater than the ALT, which is consistent with alcoholic liver disease. While the initial assumption is that this patient has alcohol-induced pancreatitis, the elevations in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase may suggest gallstone pancreatitis, and the lipemic appearing serum could suggest triglyceride-mediated pancreatitis. If the patient does have elevated triglyceride levels, the sodium level may indicate pseudohyponatremia, a laboratory artifact seen if a dilution step is used. To further evaluate the patient, I would obtain a triglyceride level and a right upper quadrant ultrasound. Direct ion-selective electrode analysis of the sodium level can be done with a device used to measure blood gases to exclude pseudohyponatremia.

► Dr. Ganatra. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was obtained in the MICU, which showed hepatic steatosis and hepatomegaly to 19 cm, but no evidence of biliary obstruction by stones or sludge. The common bile duct measured 3.2 mm in diameter. A triglyceride level returned above assay at > 3,392 mg/dL. A review of the medical record revealed a triglyceride level of 105 mg/dL 16 months prior. The Gastroenterology Department was consulted.

Dr. Weber, we now have 2 etiologies for pancreatitis in this patient: alcohol and hypertriglyceridemia. How do each cause pancreatitis? Is it possible to determine in this case which one is the more likely driver?

► Dr. Weber. The mechanism for alcohol-induced pancreatitis is not fully known, but there are several hypotheses. One is that alcohol may increase the synthesis or activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes.6 Another is that metabolites of alcohol are directly toxic to the pancreas.6 Based on the epidemiologic observation that alcoholic pancreatitis usually happens in long-standing users, all we can say is that it is not very likely to be the effect of an acute insult. For hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, we believe the injury is due to the toxic effect of free fatty acids in the pancreas liberated by lipolysis of triglycerides by pancreatic lipases. Higher triglycerides are associated with higher risk, suggesting a dose-response relationship: This risk is not greatly increased until triglycerides exceed 500 mg/dL; above 1,000 mg/dL, the risk is about 5%, and above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is between 10% and 20%.7 In summary, we cannot really determine whether the alcohol or the triglycerides are the main cause of his pancreatitis, but given his markedly elevated triglycerides, he should be treated for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis.

►Dr. Ganatra. Dr. Breu, regardless of the underlying etiology, this patient requires treatment. What does the literature suggest as the best course of action regarding crystalloid administration in patients with acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. There are 2 issues to discuss regarding IV fluids in acute pancreatitis: choice of crystalloid and rate of administration. For the choice of IV fluid, lactated Ringer solution (LR) may be preferred over normal saline (NS). There are both pathophysiologic and evidence-based rationales for this choice. As Dr. Weber alluded to, trypsinogen activation is an important step in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and requires a low pH compartment. As most clinicians have experienced, NS may cause a metabolic acidosis; however, the use of LR may mitigate this. A 2011 randomized clinical trial showed that patients who received LR had less systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and lower C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 24 hours compared with patients who received NS.8 While these are surrogate outcomes, they, along with the theoretical basis, suggest LR is preferred.

Regarding rate, the key is fast and early.9 In my experience, internists often underdose IV rehydration within the first 12 to 24 hours, fail to change the rate based on clinical response, and leave patients on high rates too long. In a patient like this, a rate of 350 cc/h is a reasonable place to start. But, one must reassess response (ie, ensure there is a decrease in hematocrit and/or blood urea nitrogen) every 6 hours and increase the rate as needed. After the first 24 to 48 hours have passed, the rate should be lowered.

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient received 2 mg of IV hydromorphone and a 2 L bolus of LR. This was followed by a continuous infusion of LR at 200 cc/h. Dr. Weber, apart from the standard therapies for pancreatitis, what are our treatment options in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis?

►Dr. Weber. In the acute setting, IV insulin with or without dextrose is the most extensively studied therapy. Insulin rapidly decreases triglyceride levels by activating lipoprotein lipase and inhibiting hormone- sensitive lipase. The net effect is reduction in serum triglycerides available to be hydrolyzed to free fatty acids in the pancreas.7 For severe cases (ie, where acute pancreatitis is accompanied by hypocalcemia, lactic acidosis or a markedly elevated lipase), apheresis with therapeutic plasma exchange to more rapidly reduce triglyceride concentration is the preferred therapy. The goal is to reduce triglycerides to levels

►Dr. Ganatra. Due to the possibility that the patient would require apheresis, which was not available at the VABHS West Roxbury campus, the patient was transferred to an affiliate hospital. The patient was started on 10% dextrose at 300 cc/h and an IV insulin infusion. His triglycerides fell to < 500 mg/dL over the subsequent 48 hours, and ultimately, apheresis was not required. Enteral nutrition by nasogastric (NG) tube was initiated on hospital day 6. The patient’s hospital course was notable for acute respiratory distress syndrome that required intubation for 7 days, hyperbilirubinemia (with a peak bilirubin of 10.5 mg/dL), acute kidney injury (with a peak creatinine 4.7 mg/dL), fever without an identified infectious source, alcohol withdrawal syndrome that required phenobarbital, and delirium. Nine days later, he was transferred back to the VABHS West Roxbury campus. His condition stabilized, and he was transferred to the medical floor. On hospital day 14, the patient’s mental status improved, and he began tolerating oral nutrition.

Dr. Breu, over the years, the standard of care regarding when to start enteral nutrition in pancreatitis has changed considerably. This patient received enteral nutrition via NG tube but also had periods of being NPO (nothing by mouth) for up to 6 days. What is the current best practice for timing of initiating enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. It is true that the standard of care has changed and continues to evolve. Many decades ago, patients with acute pancreatitis would routinely undergo NG tube suction to reduce delivery of gastric contents to the duodenum, thereby decreasing pancreas activation, allowing it to rest.11 The NG tube also allowed for decompression of any ileus that had formed. Beginning in the 1970s, several clinical trials were performed, showing that NG tube suction was no better than simply making the patient NPO.12,13 More recently, we have begun to move toward earlier feeding. Again, there is a pathophysiologic rationale (bowel rest is associated with intestinal atrophy, predisposing to bacterial translocation and resulting infectious complications) and increasing evidence supporting this practice.9 Even in severe pancreatitis, hunger may be used to initiate oral intake.14

►Dr. Ganatra. On hospital day 16, the patient developed sudden-onset right-sided back and flank pain, and his hemoglobin dropped to 6.1 mg/dL, which required transfusion of packed red blood cells. He remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Dr. Weber, what are the major complications of acute pancreatitis, and when should we suspect them? Should we be worried about complications of pancreatitis in this patient?

►Dr. Weber. Organ failure in the acute setting can occur due to activation of cytokine cascades and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and is described by clinical and radiologic criteria called the Atlanta Classification.15 Apart from organ failure, the most serious complications of acute pancreatitis are necrosis of pancreatic tissue leading to walled-off pancreatic necrosis and the formation of peripancreatic fluid collections and pseudocysts, which occur in about 15% of patients with acute pancreatitis. These complications are serious because they can become infected, which portends a higher mortality and in some cases require surgical resection.

Other complications of acute pancreatitis include pseudoaneurysm formation, which is when a vessel bleeds into a pancreatic pseudocyst, and thromboses of the splenic, portal, or mesenteric veins. Thrombotic complications may occur in up to half of patients with pancreatic necrosis but are uncommon without some degree of necrosis.16 No necrosis was noted on this patient’s initial CT scan, so the probability of thrombosis is low. Also, as it takes several weeks for pseudocyst formation to occur, a bleeding pseudoaneurysm is unlikely at this early stage. Therefore, a complication of pancreatitis is unlikely in this patient, and evaluation for other causes of abdominal pain should be considered.

►Dr. Ganatra. A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained and revealed no evidence of complications or other acute pathology. His pain was managed conservatively, and hemoglobin remained stable. Over the next 5 days, the patient’s symptoms gradually resolved, his oral intake improved, and he was discharged home on gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily 19 days after admission. He declined psychiatry follow-up for his PTSD, and after discharge he did not keep his scheduled gastroenterology (GI) follow-up appointment. Four months later, the patient presented again with epigastric abdominal pain similar to his initial presentation. The patient had resumed drinking, stating that “alcohol is the only thing that helps [with the PTSD].” He had not been taking the gemfibrozil. He was admitted with a recurrent episode of pancreatitis; however, his triglycerides on admission were 119 mg/dL.

Dr. Weber, this patient’s triglycerides declined rapidly over a period of just 4 months with questionable adherence to gemfibrozil. However, he was admitted again with another episode of pancreatitis, this time in the setting of alcohol use alone without markedly elevated triglycerides. What do we know about recurrence risk for pancreatitis? Are some etiologies of pancreatitis more likely to present with recurrent attacks than are others?

►Dr. Weber. The rate of recurrence following an episode of acute pancreatitis varies according to the cause, but in general, about 20% to 30% of patients will experience a recurrence, and 5% to 10% will go on to develop chronic pancreatitis.17 Alcoholic pancreatitis does carry a higher risk of recurrence than pancreatitis due to other causes; the risk is as high as 50%. Not surprisingly, recurrence of acute pancreatitis increases risk for development of chronic pancreatitis. As this patient is a smoker, it is worth noting that smoking potentiates pancreatic damage from alcohol and increases the risk for both recurrent and chronic pancreatitis.5

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient was treated with IV hydromorphone and IV LR at 350 cc/h. Oral nutrition was begun immediately. He manifested no organ dysfunction, and his symptoms improved over the course of 48 hours. He was discharged home with psychiatry and GI follow-up scheduled. Dr. Breu and Dr. Weber, how should we counsel this patient to reduce his risk of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis in the future, and what options do we have for pharmacotherapy to decrease his risk?

►Dr. Breu. I’ll let Dr. Weber comment on mitigating the risk of hypertriglyceride-induced pancreatitis and reserve my comments to pharmacotherapy in alcohol use disorder. This patient may be a candidate for naltrexone therapy, either in oral or intramuscular formulations. Both have been showed to reduce the risk of returning to heavy drinking and may be particularly beneficial in those with a family history.18,19 Acamprosate is also an option.

►Dr. Weber. Data on recurrence risk in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis are limited, but there are case reports suggesting that a fatty diet and alcohol use are implicated in recurrence.20 I would counsel the patient on lifestyle modifications that are known to reduce this risk. I agree with Dr. Breu that devoting our efforts to helping him reduce or eliminate his alcohol consumption is the single most important thing we can do to reduce his risk for recurrent attacks. Since the patient reports that he drinks alcohol in order to cope with his PTSD, establishing care with a mental health provider to address this is of the utmost importance. In addition, smoking cessation and promoting medication adherence with gemfibrozil will also reduce risk for future episodes, but continued alcohol use is his strongest risk factor.

►Dr. Ganatra. After discharge, the patient engaged with outpatient psychiatry and GI. He still reports feeling that alcohol is the only thing that alleviates his PTSD and anxiety symptoms. He is not currently interested in pharmacotherapy for cessation of alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ivana Jankovic, MD, Matthew Lewis Chase, MD

Case Presentation. A 23-year-old male U.S. Army veteran with a history of alcohol use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) West Roxbury campus emergency department (ED) with epigastric abdominal pain in the setting of consuming alcohol. The patient had served in the infantry in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He consumed up to 12 alcoholic drinks per day (both beer and hard liquor) for the past 3 years and had been hospitalized 3 times previously; twice for alcohol detoxification and once for PTSD. He is a former tobacco smoker with fewer than 5 pack-years, he uses marijuana often and does not use IV drugs. In the ED, his physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 130 beats per minute and blood pressure of 161/111 mm Hg. He was alert and oriented and had a mild tremor. The patient was diaphoretic with dry mucous membranes, tenderness to palpation in the epigastrium, and abdominal guarding. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed acute pancreatitis without necrosis. The patient received 1 L of normal saline and was admitted to the medical ward for presumed alcoholic pancreatitis.

► Rahul Ganatra, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dr. Weber, we care for many young people who drink more than they should and almost none of them end up with alcoholic pancreatitis. What are the relevant risk factors that make individuals like this patient more susceptible to alcoholic pancreatitis?

►Horst Christian Weber, MD, Gastroenterology Service, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. While we don’t have a good understanding of the precise mechanism of alcoholic pancreatitis, we do know that in the U.S., alcohol consumption is responsible for about one-third of all cases.1 Acute pancreatitis in general may present with a wide range of disease severity. It is the most common cause of gastrointestinal-related hospitalization,2 and the mortality of hospital inpatients with pancreatitis is about 5%.3,4 Therefore, acute pancreatitis represents a prevalent condition with a critical impact on morbidity and mortality. Alcoholic pancreatitis typically occurs after many years of heavy alcohol use, not after a single drinking

► Dr. Ganatra. At this point, the chemistry laboratory paged the admitting resident with the notification that the patient’s blood was grossly lipemic. Ultracentrifugation was performed to separate the lipid layer and his laboratory values result (Table). Notable abnormalities included polycythemia with a hemoglobin of 17.4 g/dL, hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mmol/L, normal renal function, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (AST 258 IU/L and ALT 153 IU/L, respectively), hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 2.7 mg/dL, and a serum alcohol level of 147 mg/dL. Due to anticipated requirement for a higher level of care, the patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU).

Dr. Breu, can you help us interpret this patient’s numerous laboratory abnormalities? Without yet having the triglyceride level available, how does the fact that the patient’s blood was lipemic affect our interpretation of his labs? What further workup is warranted?

► Anthony Breu, MD, Medical Service, VABHS, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. First, the positive alcohol level confirms a recent ingestion. Second, he has elevated transaminases with the AST greater than the ALT, which is consistent with alcoholic liver disease. While the initial assumption is that this patient has alcohol-induced pancreatitis, the elevations in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase may suggest gallstone pancreatitis, and the lipemic appearing serum could suggest triglyceride-mediated pancreatitis. If the patient does have elevated triglyceride levels, the sodium level may indicate pseudohyponatremia, a laboratory artifact seen if a dilution step is used. To further evaluate the patient, I would obtain a triglyceride level and a right upper quadrant ultrasound. Direct ion-selective electrode analysis of the sodium level can be done with a device used to measure blood gases to exclude pseudohyponatremia.

► Dr. Ganatra. A right upper quadrant ultrasound was obtained in the MICU, which showed hepatic steatosis and hepatomegaly to 19 cm, but no evidence of biliary obstruction by stones or sludge. The common bile duct measured 3.2 mm in diameter. A triglyceride level returned above assay at > 3,392 mg/dL. A review of the medical record revealed a triglyceride level of 105 mg/dL 16 months prior. The Gastroenterology Department was consulted.

Dr. Weber, we now have 2 etiologies for pancreatitis in this patient: alcohol and hypertriglyceridemia. How do each cause pancreatitis? Is it possible to determine in this case which one is the more likely driver?

► Dr. Weber. The mechanism for alcohol-induced pancreatitis is not fully known, but there are several hypotheses. One is that alcohol may increase the synthesis or activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes.6 Another is that metabolites of alcohol are directly toxic to the pancreas.6 Based on the epidemiologic observation that alcoholic pancreatitis usually happens in long-standing users, all we can say is that it is not very likely to be the effect of an acute insult. For hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, we believe the injury is due to the toxic effect of free fatty acids in the pancreas liberated by lipolysis of triglycerides by pancreatic lipases. Higher triglycerides are associated with higher risk, suggesting a dose-response relationship: This risk is not greatly increased until triglycerides exceed 500 mg/dL; above 1,000 mg/dL, the risk is about 5%, and above 2,000 mg/dL, the risk is between 10% and 20%.7 In summary, we cannot really determine whether the alcohol or the triglycerides are the main cause of his pancreatitis, but given his markedly elevated triglycerides, he should be treated for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis.

►Dr. Ganatra. Dr. Breu, regardless of the underlying etiology, this patient requires treatment. What does the literature suggest as the best course of action regarding crystalloid administration in patients with acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. There are 2 issues to discuss regarding IV fluids in acute pancreatitis: choice of crystalloid and rate of administration. For the choice of IV fluid, lactated Ringer solution (LR) may be preferred over normal saline (NS). There are both pathophysiologic and evidence-based rationales for this choice. As Dr. Weber alluded to, trypsinogen activation is an important step in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and requires a low pH compartment. As most clinicians have experienced, NS may cause a metabolic acidosis; however, the use of LR may mitigate this. A 2011 randomized clinical trial showed that patients who received LR had less systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and lower C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 24 hours compared with patients who received NS.8 While these are surrogate outcomes, they, along with the theoretical basis, suggest LR is preferred.

Regarding rate, the key is fast and early.9 In my experience, internists often underdose IV rehydration within the first 12 to 24 hours, fail to change the rate based on clinical response, and leave patients on high rates too long. In a patient like this, a rate of 350 cc/h is a reasonable place to start. But, one must reassess response (ie, ensure there is a decrease in hematocrit and/or blood urea nitrogen) every 6 hours and increase the rate as needed. After the first 24 to 48 hours have passed, the rate should be lowered.

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient received 2 mg of IV hydromorphone and a 2 L bolus of LR. This was followed by a continuous infusion of LR at 200 cc/h. Dr. Weber, apart from the standard therapies for pancreatitis, what are our treatment options in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis?

►Dr. Weber. In the acute setting, IV insulin with or without dextrose is the most extensively studied therapy. Insulin rapidly decreases triglyceride levels by activating lipoprotein lipase and inhibiting hormone- sensitive lipase. The net effect is reduction in serum triglycerides available to be hydrolyzed to free fatty acids in the pancreas.7 For severe cases (ie, where acute pancreatitis is accompanied by hypocalcemia, lactic acidosis or a markedly elevated lipase), apheresis with therapeutic plasma exchange to more rapidly reduce triglyceride concentration is the preferred therapy. The goal is to reduce triglycerides to levels

►Dr. Ganatra. Due to the possibility that the patient would require apheresis, which was not available at the VABHS West Roxbury campus, the patient was transferred to an affiliate hospital. The patient was started on 10% dextrose at 300 cc/h and an IV insulin infusion. His triglycerides fell to < 500 mg/dL over the subsequent 48 hours, and ultimately, apheresis was not required. Enteral nutrition by nasogastric (NG) tube was initiated on hospital day 6. The patient’s hospital course was notable for acute respiratory distress syndrome that required intubation for 7 days, hyperbilirubinemia (with a peak bilirubin of 10.5 mg/dL), acute kidney injury (with a peak creatinine 4.7 mg/dL), fever without an identified infectious source, alcohol withdrawal syndrome that required phenobarbital, and delirium. Nine days later, he was transferred back to the VABHS West Roxbury campus. His condition stabilized, and he was transferred to the medical floor. On hospital day 14, the patient’s mental status improved, and he began tolerating oral nutrition.

Dr. Breu, over the years, the standard of care regarding when to start enteral nutrition in pancreatitis has changed considerably. This patient received enteral nutrition via NG tube but also had periods of being NPO (nothing by mouth) for up to 6 days. What is the current best practice for timing of initiating enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis?

►Dr. Breu. It is true that the standard of care has changed and continues to evolve. Many decades ago, patients with acute pancreatitis would routinely undergo NG tube suction to reduce delivery of gastric contents to the duodenum, thereby decreasing pancreas activation, allowing it to rest.11 The NG tube also allowed for decompression of any ileus that had formed. Beginning in the 1970s, several clinical trials were performed, showing that NG tube suction was no better than simply making the patient NPO.12,13 More recently, we have begun to move toward earlier feeding. Again, there is a pathophysiologic rationale (bowel rest is associated with intestinal atrophy, predisposing to bacterial translocation and resulting infectious complications) and increasing evidence supporting this practice.9 Even in severe pancreatitis, hunger may be used to initiate oral intake.14

►Dr. Ganatra. On hospital day 16, the patient developed sudden-onset right-sided back and flank pain, and his hemoglobin dropped to 6.1 mg/dL, which required transfusion of packed red blood cells. He remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Dr. Weber, what are the major complications of acute pancreatitis, and when should we suspect them? Should we be worried about complications of pancreatitis in this patient?

►Dr. Weber. Organ failure in the acute setting can occur due to activation of cytokine cascades and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and is described by clinical and radiologic criteria called the Atlanta Classification.15 Apart from organ failure, the most serious complications of acute pancreatitis are necrosis of pancreatic tissue leading to walled-off pancreatic necrosis and the formation of peripancreatic fluid collections and pseudocysts, which occur in about 15% of patients with acute pancreatitis. These complications are serious because they can become infected, which portends a higher mortality and in some cases require surgical resection.

Other complications of acute pancreatitis include pseudoaneurysm formation, which is when a vessel bleeds into a pancreatic pseudocyst, and thromboses of the splenic, portal, or mesenteric veins. Thrombotic complications may occur in up to half of patients with pancreatic necrosis but are uncommon without some degree of necrosis.16 No necrosis was noted on this patient’s initial CT scan, so the probability of thrombosis is low. Also, as it takes several weeks for pseudocyst formation to occur, a bleeding pseudoaneurysm is unlikely at this early stage. Therefore, a complication of pancreatitis is unlikely in this patient, and evaluation for other causes of abdominal pain should be considered.

►Dr. Ganatra. A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained and revealed no evidence of complications or other acute pathology. His pain was managed conservatively, and hemoglobin remained stable. Over the next 5 days, the patient’s symptoms gradually resolved, his oral intake improved, and he was discharged home on gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily 19 days after admission. He declined psychiatry follow-up for his PTSD, and after discharge he did not keep his scheduled gastroenterology (GI) follow-up appointment. Four months later, the patient presented again with epigastric abdominal pain similar to his initial presentation. The patient had resumed drinking, stating that “alcohol is the only thing that helps [with the PTSD].” He had not been taking the gemfibrozil. He was admitted with a recurrent episode of pancreatitis; however, his triglycerides on admission were 119 mg/dL.

Dr. Weber, this patient’s triglycerides declined rapidly over a period of just 4 months with questionable adherence to gemfibrozil. However, he was admitted again with another episode of pancreatitis, this time in the setting of alcohol use alone without markedly elevated triglycerides. What do we know about recurrence risk for pancreatitis? Are some etiologies of pancreatitis more likely to present with recurrent attacks than are others?

►Dr. Weber. The rate of recurrence following an episode of acute pancreatitis varies according to the cause, but in general, about 20% to 30% of patients will experience a recurrence, and 5% to 10% will go on to develop chronic pancreatitis.17 Alcoholic pancreatitis does carry a higher risk of recurrence than pancreatitis due to other causes; the risk is as high as 50%. Not surprisingly, recurrence of acute pancreatitis increases risk for development of chronic pancreatitis. As this patient is a smoker, it is worth noting that smoking potentiates pancreatic damage from alcohol and increases the risk for both recurrent and chronic pancreatitis.5

►Dr. Ganatra. The patient was treated with IV hydromorphone and IV LR at 350 cc/h. Oral nutrition was begun immediately. He manifested no organ dysfunction, and his symptoms improved over the course of 48 hours. He was discharged home with psychiatry and GI follow-up scheduled. Dr. Breu and Dr. Weber, how should we counsel this patient to reduce his risk of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis in the future, and what options do we have for pharmacotherapy to decrease his risk?

►Dr. Breu. I’ll let Dr. Weber comment on mitigating the risk of hypertriglyceride-induced pancreatitis and reserve my comments to pharmacotherapy in alcohol use disorder. This patient may be a candidate for naltrexone therapy, either in oral or intramuscular formulations. Both have been showed to reduce the risk of returning to heavy drinking and may be particularly beneficial in those with a family history.18,19 Acamprosate is also an option.

►Dr. Weber. Data on recurrence risk in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis are limited, but there are case reports suggesting that a fatty diet and alcohol use are implicated in recurrence.20 I would counsel the patient on lifestyle modifications that are known to reduce this risk. I agree with Dr. Breu that devoting our efforts to helping him reduce or eliminate his alcohol consumption is the single most important thing we can do to reduce his risk for recurrent attacks. Since the patient reports that he drinks alcohol in order to cope with his PTSD, establishing care with a mental health provider to address this is of the utmost importance. In addition, smoking cessation and promoting medication adherence with gemfibrozil will also reduce risk for future episodes, but continued alcohol use is his strongest risk factor.

►Dr. Ganatra. After discharge, the patient engaged with outpatient psychiatry and GI. He still reports feeling that alcohol is the only thing that alleviates his PTSD and anxiety symptoms. He is not currently interested in pharmacotherapy for cessation of alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ivana Jankovic, MD, Matthew Lewis Chase, MD

1. Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27(4):286-290.

2. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3.

3. Cavallini G, Frulloni L, Bassi C, et al; ProInf-AISP Study Group. Prospective multicentre survey on acute pancreatitis in Italy (ProInf-AISP): results on 1005 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(3):205-211.

4. Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2379-2400.

5. Hartwig W, Werner J, Ryschich E, et al. Cigarette smoke enhances ethanol-induced pancreatic injury. Pancreas. 2000;21(3):272-278.

6. Chowdhury P, Gupta P. Pathophysiology of alcoholic pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(46):7421-7427.

7. Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195-203.

8. Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(8):710-717.e1.

9. Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1400-1415; 1416.

10. Preiss D, Tikkanen MJ, Welsh P, et al. Lipid-modifying therapies and risk of pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(8):804-811.

11. Nardi GL. Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1963;268(19):1065-1067.

12. Naeije R, Salingret E, Clumeck N, De Troyer A, Devis G. Is nasogastric suction necessary in acute pancreatitis? Br Med J. 1978;2(6138):659-660.

13. Levant JA, Secrist DM, Resin H, Sturdevant RA, Guth PH. Nasogastric suction in the treatment of alcoholic pancreatitis: a controlled study. JAMA. 1974;229(1):51-52.

14. Zhao XL, Zhu SF, Xue GJ, et al. Early oral refeeding based on hunger in moderate and severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):171-175.

15. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111.

16. Easler J, Muddana V, Furlan A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):854-862.

17. Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1096-1103.

18. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

19. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617-1625.

20. Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas. 1996;13(1):96-99.

1. Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27(4):286-290.

2. Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e1-e3.

3. Cavallini G, Frulloni L, Bassi C, et al; ProInf-AISP Study Group. Prospective multicentre survey on acute pancreatitis in Italy (ProInf-AISP): results on 1005 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(3):205-211.

4. Banks PA, Freeman ML; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2379-2400.

5. Hartwig W, Werner J, Ryschich E, et al. Cigarette smoke enhances ethanol-induced pancreatic injury. Pancreas. 2000;21(3):272-278.

6. Chowdhury P, Gupta P. Pathophysiology of alcoholic pancreatitis: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(46):7421-7427.

7. Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195-203.

8. Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(8):710-717.e1.

9. Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1400-1415; 1416.

10. Preiss D, Tikkanen MJ, Welsh P, et al. Lipid-modifying therapies and risk of pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(8):804-811.

11. Nardi GL. Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1963;268(19):1065-1067.

12. Naeije R, Salingret E, Clumeck N, De Troyer A, Devis G. Is nasogastric suction necessary in acute pancreatitis? Br Med J. 1978;2(6138):659-660.

13. Levant JA, Secrist DM, Resin H, Sturdevant RA, Guth PH. Nasogastric suction in the treatment of alcoholic pancreatitis: a controlled study. JAMA. 1974;229(1):51-52.

14. Zhao XL, Zhu SF, Xue GJ, et al. Early oral refeeding based on hunger in moderate and severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):171-175.

15. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111.

16. Easler J, Muddana V, Furlan A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):854-862.

17. Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1096-1103.

18. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

19. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617-1625.

20. Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas. 1996;13(1):96-99.