User login

Knead a Hand? Use of a Portable Massager to Reduce Patient Pain and Anxiety During Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

Pain and anxiety are common in fully conscious patients undergoing dermatologic surgery with local anesthesia. Particularly during nail surgery, pain from anesthetic injection—caused by both needle insertion and fluid infiltration—occurs because the nail unit is highly vascularized and innervated.1 Current methods to improve patient comfort during infiltration include use of a buffered anesthetic solution, warming the anesthetic, slower technique, and direct cold application.2

Perioperative anxiety correlates with increased postoperative pain, analgesic use, and delayed recovery. Furthermore, increased perioperative anxiety reduces the pain threshold and elevates estimates of pain intensity.3 Therefore, reducing procedure-related anxiety and pain may improve quality of care and ease patient discomfort.

Distraction is a common and practical nonpharmacotherapeutic technique for reducing pain and anxiety during medical procedures. The refocusing method of distraction aims to divert attention away from pain to more pleasant stimuli to reduce pain perception.3 Several methods of distraction—using stress balls, engaging in conversation, hand-holding, applying virtual reality, and playing videos—can decrease perioperative anxiety and pain.3-6

Procedural pain and distraction techniques have been evaluated in the pediatric population more than in adults.4 Nail surgery–associated pain and distraction techniques for nail surgery have been inadequately studied.7

We offer a distraction technique utilizing a portable massager to ensure that patients are as comfortable as possible when the local anesthetic is injected prior to the first incision.

The Technique

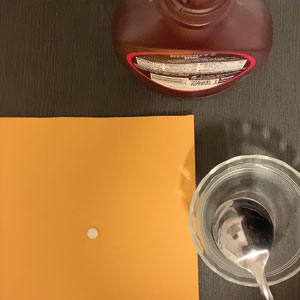

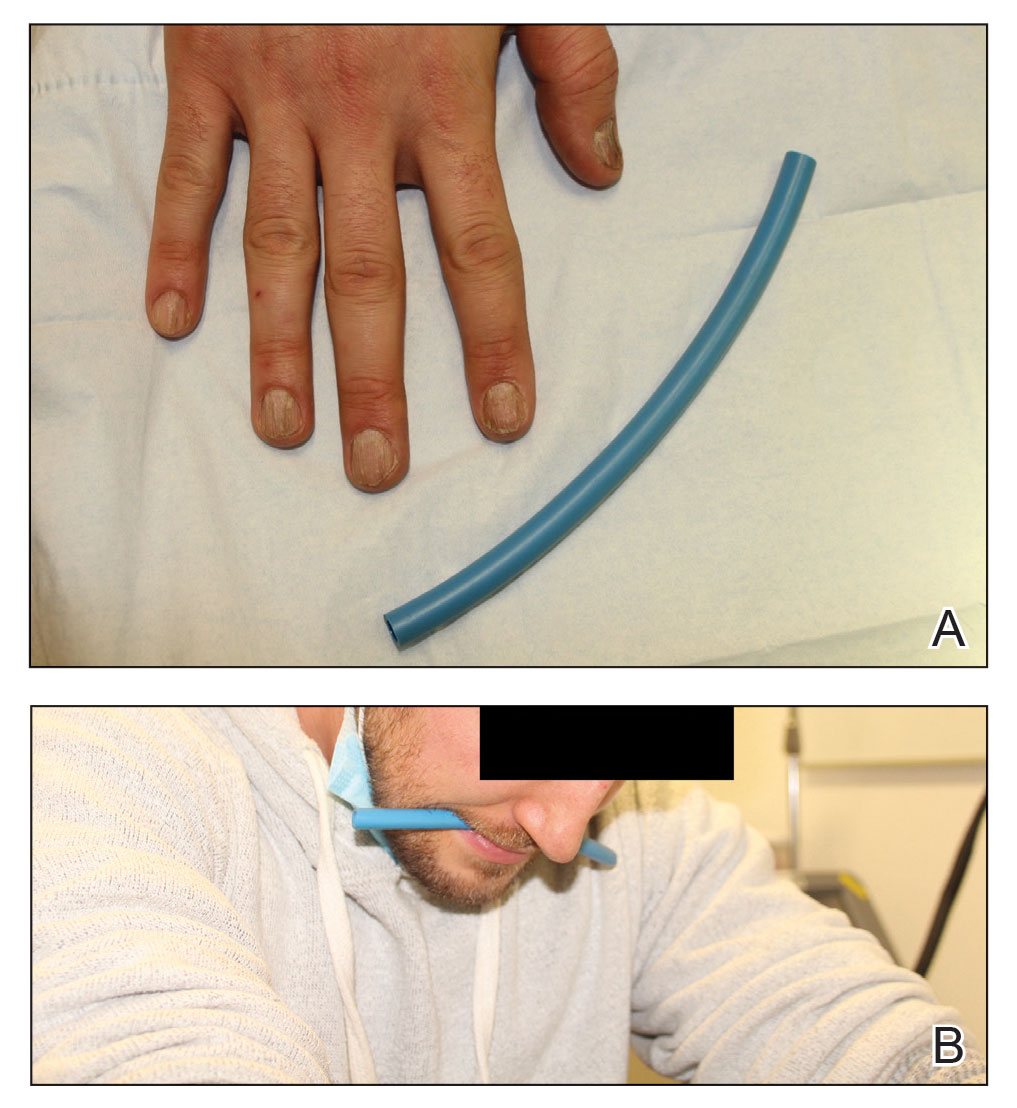

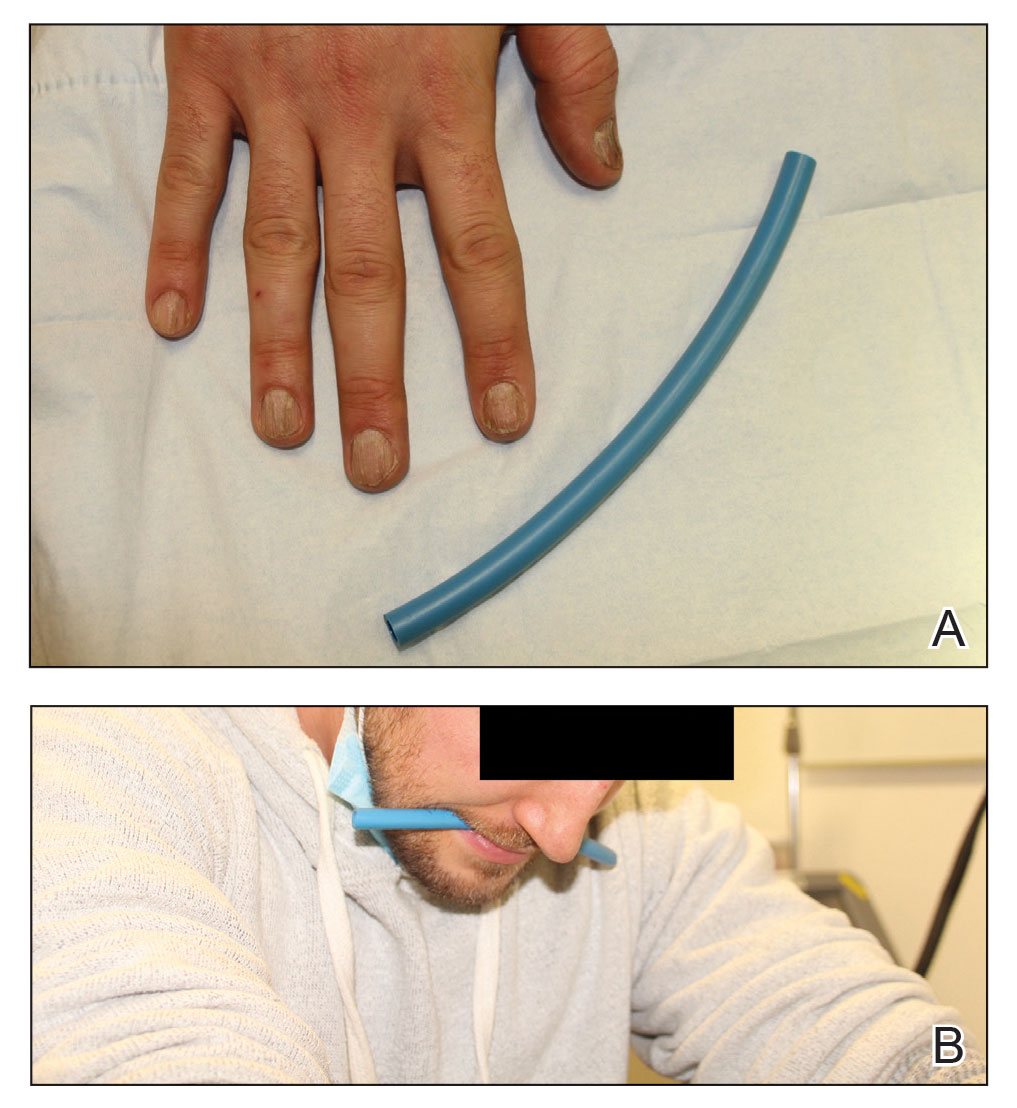

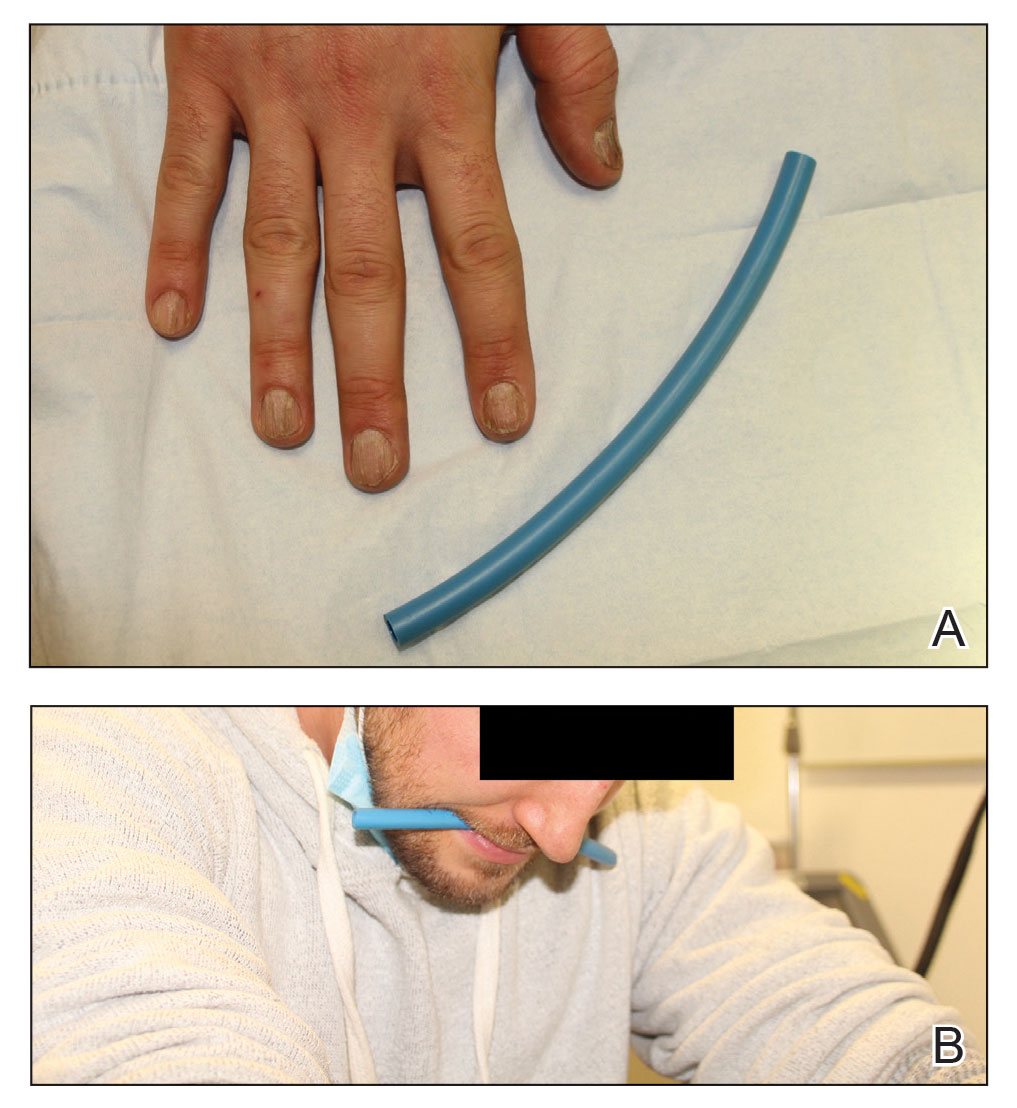

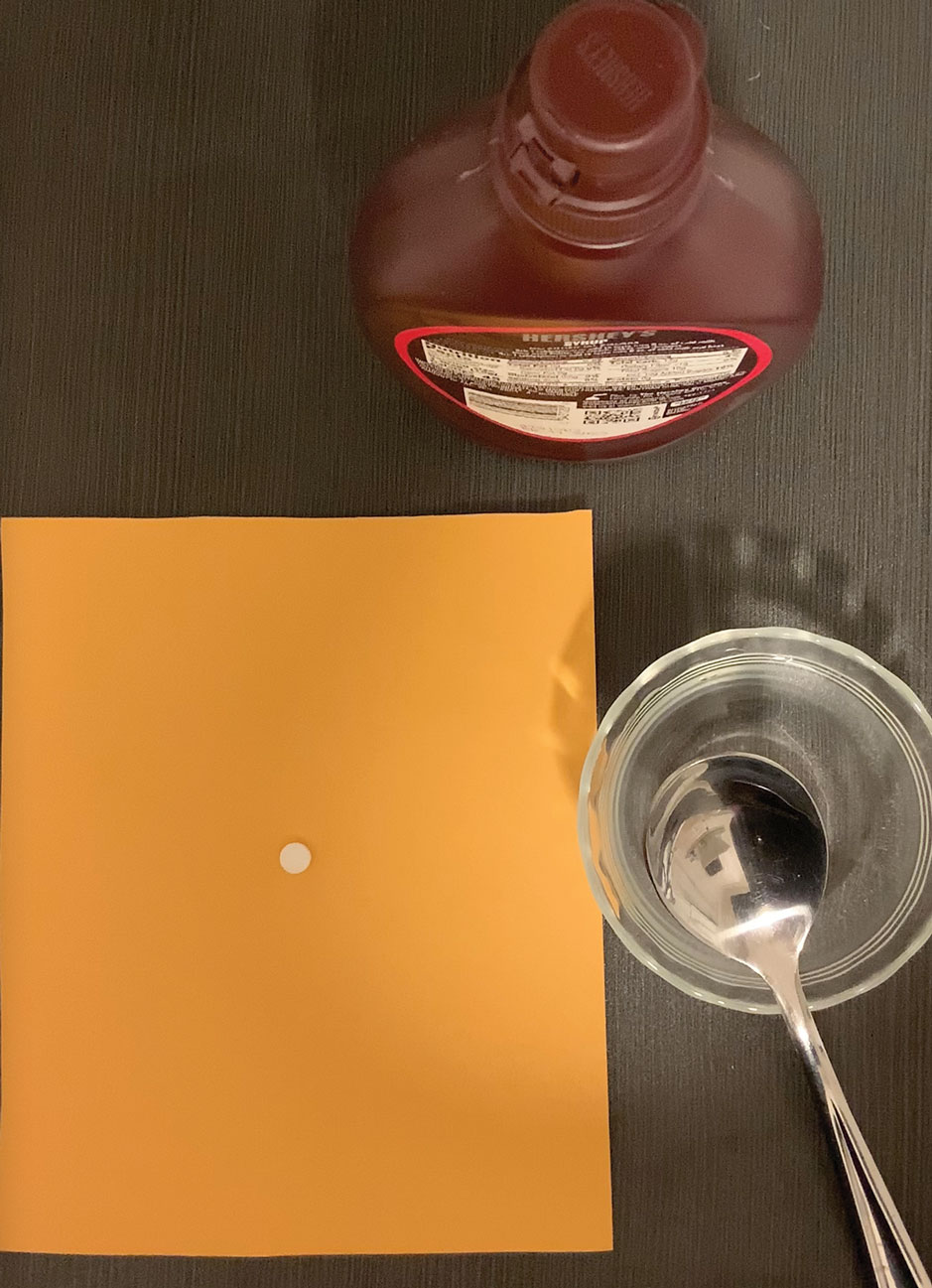

A portable shiatsu massager that uses heat and deep-tissue kneading is placed on the upper thigh for toenail cases or lower arm for fingernail cases during injection of anesthetic to divert the patient’s attention from the surgical site (Figure). Kneading from the massage helps distract the patient from pain by introducing a competing, more pleasant, vibrating sensation that overrides pain signals; the relaxation component helps to diminish patient anxiety during injection.

Practice Implications

Use of a portable massager may reduce pain through both distraction and vibration. In a randomized clinical trial of 115 patients undergoing hand or facial surgery, patients who viewed a distraction video during the procedure reported a lower pain score compared to the control group (mean [SD] visual analog scale of pain score, 3.4 [2.6] vs 4.5 [2.6][P=.01]).4 In another randomized clinical trial of 25 patients undergoing lip augmentation, 92% of patients (23/25) in the vibration-assisted arm endorsed less pain during procedures compared to the arm without vibration (mean [SD] pain score, 3.82 [1.73] vs 5.6 [1.76][P<.001]).8

Utilization of a portable massager is a safe means of improving the patient experience; the distracting and relaxing effects and intense pulsations simultaneously reduce anxiety and pain during nail surgery. Controlled clinical trials are needed to evaluate its efficacy in diminishing both anxiety and pain during nail procedures compared to other analgesic methods.

- Lipner SR. Pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgery. Cutis. 2018;101:76-77.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Air cooling for improved analgesia during local anesthetic infiltration for nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E231-E232. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.032

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. Randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of simple distraction interventions on pain and anxiety experienced during conscious surgery. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1447-1455. doi:10.1002/ejp.675

- Molleman J, Tielemans JF, Braam MJI, et al. Distraction as a simple and effective method to reduce pain during local anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019;72:1979-1985. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2019.07.023

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ricardo JW, Qiu Y, Lipner SR. Longitudinal perioperative pain assessment in nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.042

- Guney K, Sezgin B, Yavuzer R. The efficacy of vibration anesthesia on reducing pain levels during lip augmentation: worth the buzz? Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:1044-1048. doi:10.1093/asj/sjx073

Practice Gap

Pain and anxiety are common in fully conscious patients undergoing dermatologic surgery with local anesthesia. Particularly during nail surgery, pain from anesthetic injection—caused by both needle insertion and fluid infiltration—occurs because the nail unit is highly vascularized and innervated.1 Current methods to improve patient comfort during infiltration include use of a buffered anesthetic solution, warming the anesthetic, slower technique, and direct cold application.2

Perioperative anxiety correlates with increased postoperative pain, analgesic use, and delayed recovery. Furthermore, increased perioperative anxiety reduces the pain threshold and elevates estimates of pain intensity.3 Therefore, reducing procedure-related anxiety and pain may improve quality of care and ease patient discomfort.

Distraction is a common and practical nonpharmacotherapeutic technique for reducing pain and anxiety during medical procedures. The refocusing method of distraction aims to divert attention away from pain to more pleasant stimuli to reduce pain perception.3 Several methods of distraction—using stress balls, engaging in conversation, hand-holding, applying virtual reality, and playing videos—can decrease perioperative anxiety and pain.3-6

Procedural pain and distraction techniques have been evaluated in the pediatric population more than in adults.4 Nail surgery–associated pain and distraction techniques for nail surgery have been inadequately studied.7

We offer a distraction technique utilizing a portable massager to ensure that patients are as comfortable as possible when the local anesthetic is injected prior to the first incision.

The Technique

A portable shiatsu massager that uses heat and deep-tissue kneading is placed on the upper thigh for toenail cases or lower arm for fingernail cases during injection of anesthetic to divert the patient’s attention from the surgical site (Figure). Kneading from the massage helps distract the patient from pain by introducing a competing, more pleasant, vibrating sensation that overrides pain signals; the relaxation component helps to diminish patient anxiety during injection.

Practice Implications

Use of a portable massager may reduce pain through both distraction and vibration. In a randomized clinical trial of 115 patients undergoing hand or facial surgery, patients who viewed a distraction video during the procedure reported a lower pain score compared to the control group (mean [SD] visual analog scale of pain score, 3.4 [2.6] vs 4.5 [2.6][P=.01]).4 In another randomized clinical trial of 25 patients undergoing lip augmentation, 92% of patients (23/25) in the vibration-assisted arm endorsed less pain during procedures compared to the arm without vibration (mean [SD] pain score, 3.82 [1.73] vs 5.6 [1.76][P<.001]).8

Utilization of a portable massager is a safe means of improving the patient experience; the distracting and relaxing effects and intense pulsations simultaneously reduce anxiety and pain during nail surgery. Controlled clinical trials are needed to evaluate its efficacy in diminishing both anxiety and pain during nail procedures compared to other analgesic methods.

Practice Gap

Pain and anxiety are common in fully conscious patients undergoing dermatologic surgery with local anesthesia. Particularly during nail surgery, pain from anesthetic injection—caused by both needle insertion and fluid infiltration—occurs because the nail unit is highly vascularized and innervated.1 Current methods to improve patient comfort during infiltration include use of a buffered anesthetic solution, warming the anesthetic, slower technique, and direct cold application.2

Perioperative anxiety correlates with increased postoperative pain, analgesic use, and delayed recovery. Furthermore, increased perioperative anxiety reduces the pain threshold and elevates estimates of pain intensity.3 Therefore, reducing procedure-related anxiety and pain may improve quality of care and ease patient discomfort.

Distraction is a common and practical nonpharmacotherapeutic technique for reducing pain and anxiety during medical procedures. The refocusing method of distraction aims to divert attention away from pain to more pleasant stimuli to reduce pain perception.3 Several methods of distraction—using stress balls, engaging in conversation, hand-holding, applying virtual reality, and playing videos—can decrease perioperative anxiety and pain.3-6

Procedural pain and distraction techniques have been evaluated in the pediatric population more than in adults.4 Nail surgery–associated pain and distraction techniques for nail surgery have been inadequately studied.7

We offer a distraction technique utilizing a portable massager to ensure that patients are as comfortable as possible when the local anesthetic is injected prior to the first incision.

The Technique

A portable shiatsu massager that uses heat and deep-tissue kneading is placed on the upper thigh for toenail cases or lower arm for fingernail cases during injection of anesthetic to divert the patient’s attention from the surgical site (Figure). Kneading from the massage helps distract the patient from pain by introducing a competing, more pleasant, vibrating sensation that overrides pain signals; the relaxation component helps to diminish patient anxiety during injection.

Practice Implications

Use of a portable massager may reduce pain through both distraction and vibration. In a randomized clinical trial of 115 patients undergoing hand or facial surgery, patients who viewed a distraction video during the procedure reported a lower pain score compared to the control group (mean [SD] visual analog scale of pain score, 3.4 [2.6] vs 4.5 [2.6][P=.01]).4 In another randomized clinical trial of 25 patients undergoing lip augmentation, 92% of patients (23/25) in the vibration-assisted arm endorsed less pain during procedures compared to the arm without vibration (mean [SD] pain score, 3.82 [1.73] vs 5.6 [1.76][P<.001]).8

Utilization of a portable massager is a safe means of improving the patient experience; the distracting and relaxing effects and intense pulsations simultaneously reduce anxiety and pain during nail surgery. Controlled clinical trials are needed to evaluate its efficacy in diminishing both anxiety and pain during nail procedures compared to other analgesic methods.

- Lipner SR. Pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgery. Cutis. 2018;101:76-77.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Air cooling for improved analgesia during local anesthetic infiltration for nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E231-E232. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.032

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. Randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of simple distraction interventions on pain and anxiety experienced during conscious surgery. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1447-1455. doi:10.1002/ejp.675

- Molleman J, Tielemans JF, Braam MJI, et al. Distraction as a simple and effective method to reduce pain during local anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019;72:1979-1985. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2019.07.023

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ricardo JW, Qiu Y, Lipner SR. Longitudinal perioperative pain assessment in nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.042

- Guney K, Sezgin B, Yavuzer R. The efficacy of vibration anesthesia on reducing pain levels during lip augmentation: worth the buzz? Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:1044-1048. doi:10.1093/asj/sjx073

- Lipner SR. Pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgery. Cutis. 2018;101:76-77.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Air cooling for improved analgesia during local anesthetic infiltration for nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E231-E232. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.032

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. Randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of simple distraction interventions on pain and anxiety experienced during conscious surgery. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1447-1455. doi:10.1002/ejp.675

- Molleman J, Tielemans JF, Braam MJI, et al. Distraction as a simple and effective method to reduce pain during local anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019;72:1979-1985. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2019.07.023

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ricardo JW, Qiu Y, Lipner SR. Longitudinal perioperative pain assessment in nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.042

- Guney K, Sezgin B, Yavuzer R. The efficacy of vibration anesthesia on reducing pain levels during lip augmentation: worth the buzz? Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:1044-1048. doi:10.1093/asj/sjx073

Cadaveric Split-Thickness Skin Graft With Partial Guiding Closure for Scalp Defects Extending to the Periosteum

Practice Gap

Scalp defects that extend to or below the periosteum often pose a reconstructive conundrum. Secondary-intention healing is challenging without an intact periosteum, and complex rotational flaps are required in these scenarios.1 For a tumor that is at high risk for recurrence or when adjuvant therapy is necessary, tissue distortion of flaps can make monitoring for recurrence difficult. Similarly, for patients in poor health or who are elderly and have substantial skin atrophy, extensive closure may be undesirable or more technically challenging with a higher risk for adverse events. In these scenarios, additional strategies are necessary to optimize wound healing and cosmesis. A cadaveric split-thickness skin graft (STSG) consisting of biologically active tissue can be used to expedite granulation.2

Technique

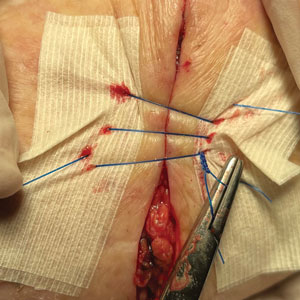

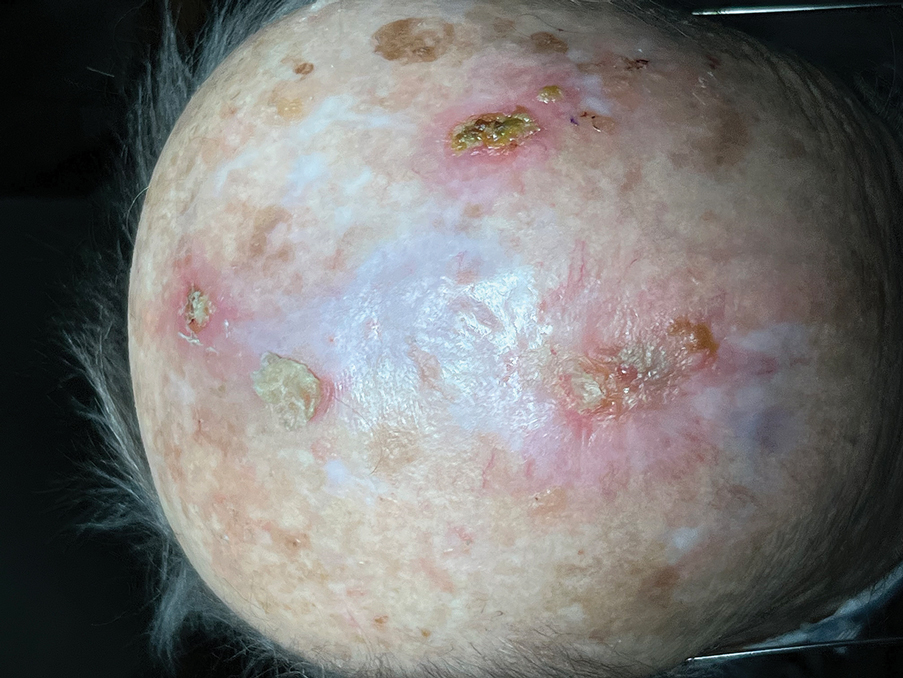

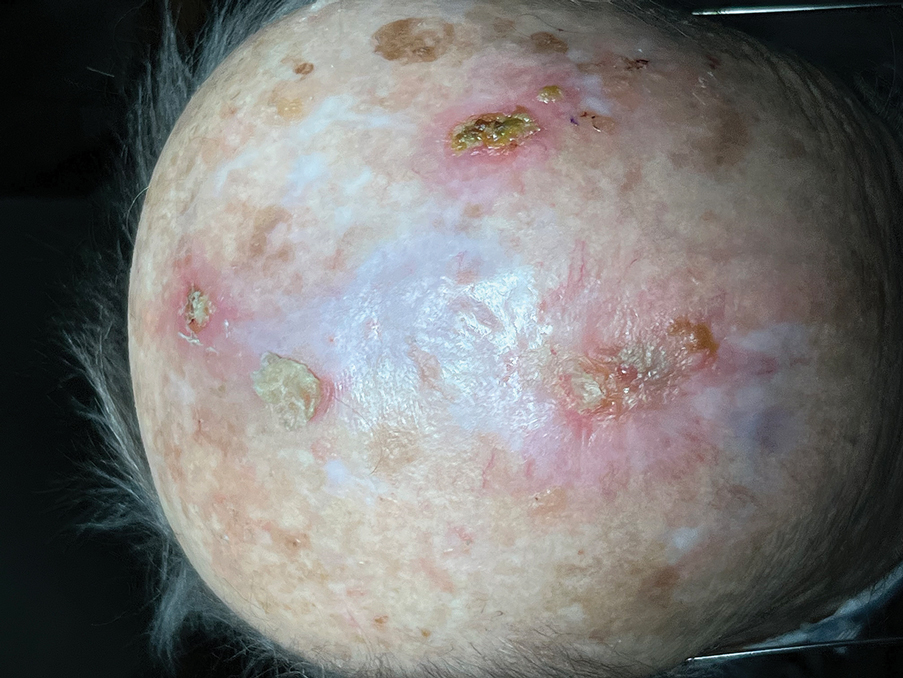

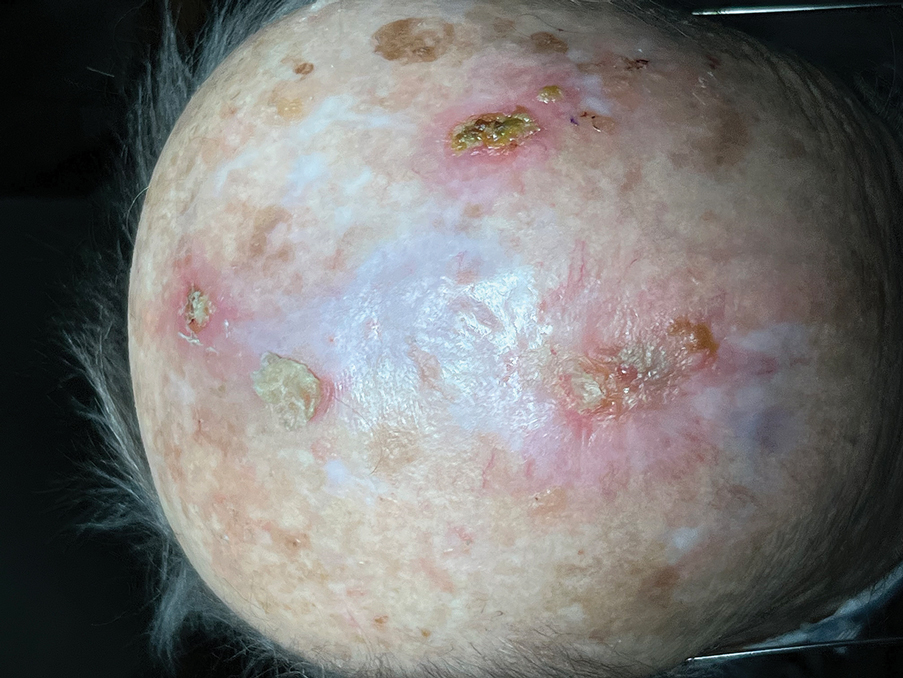

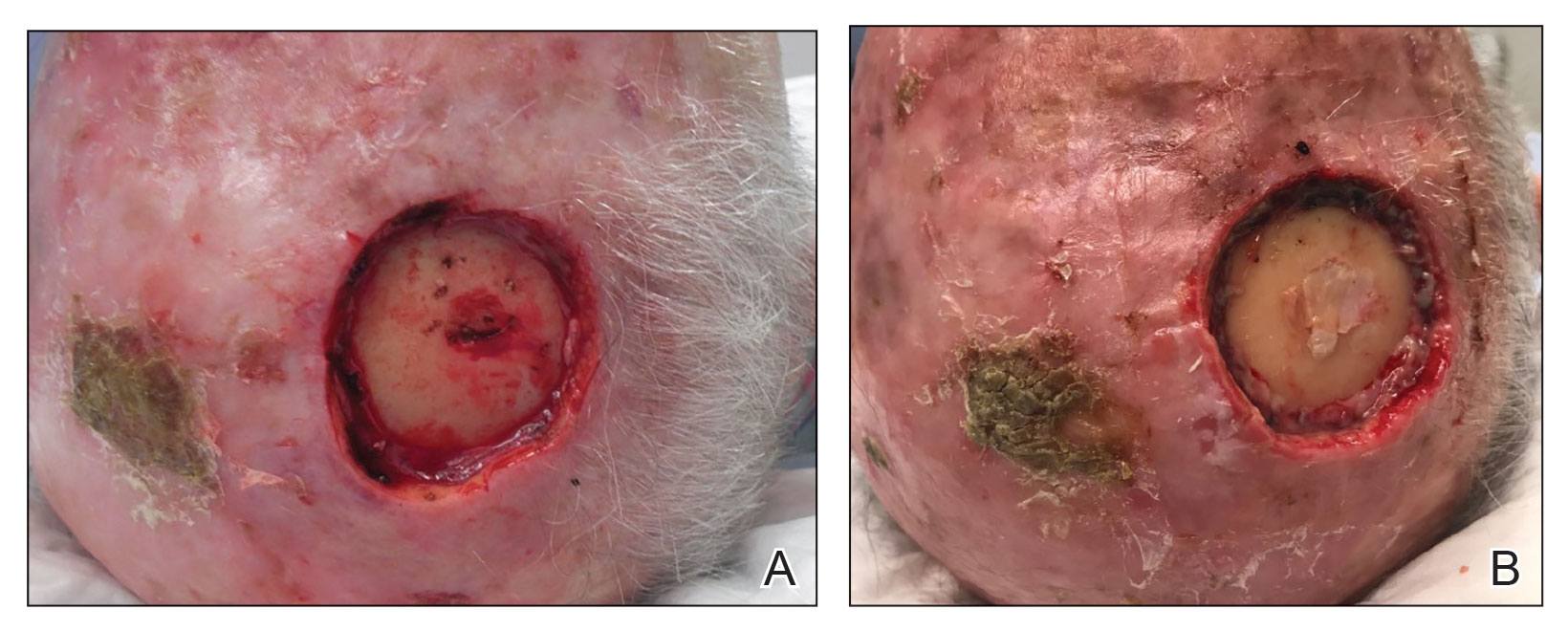

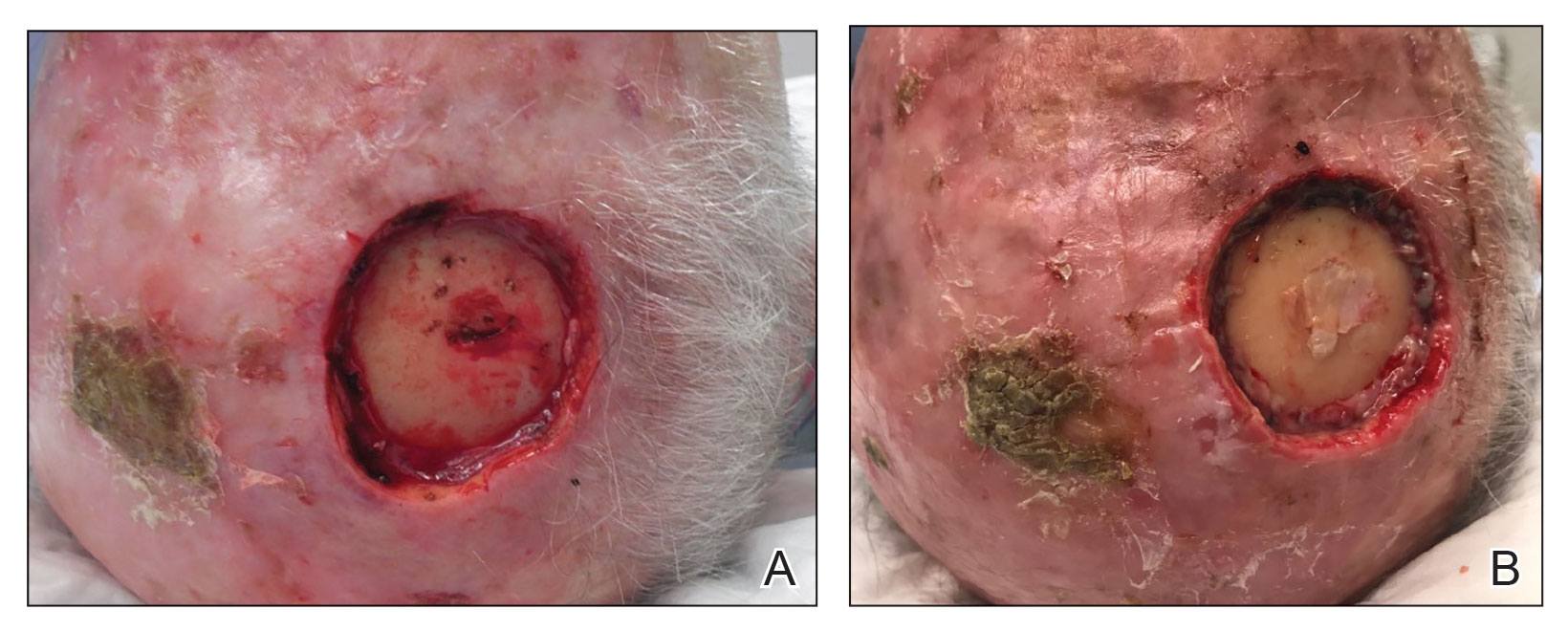

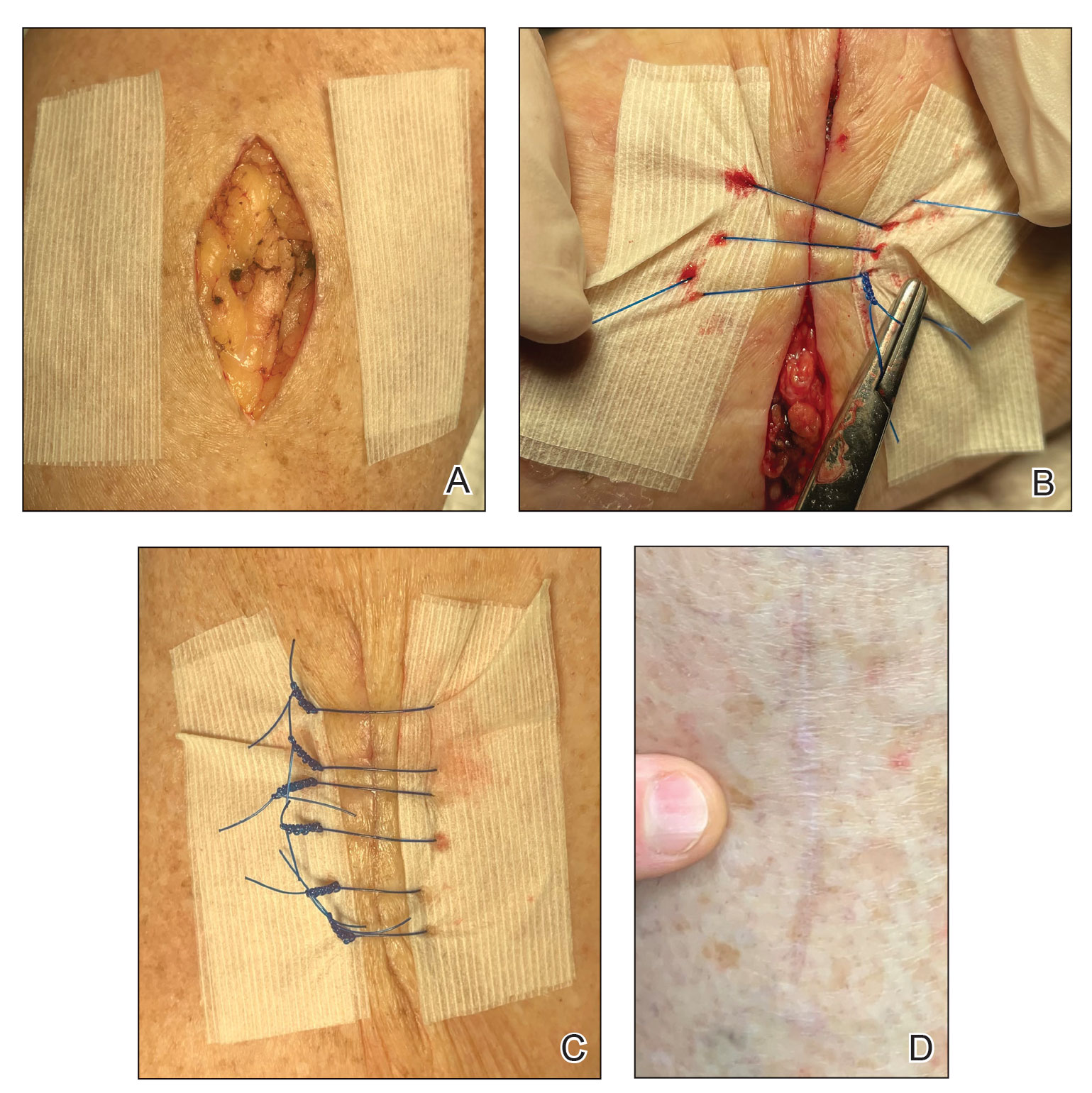

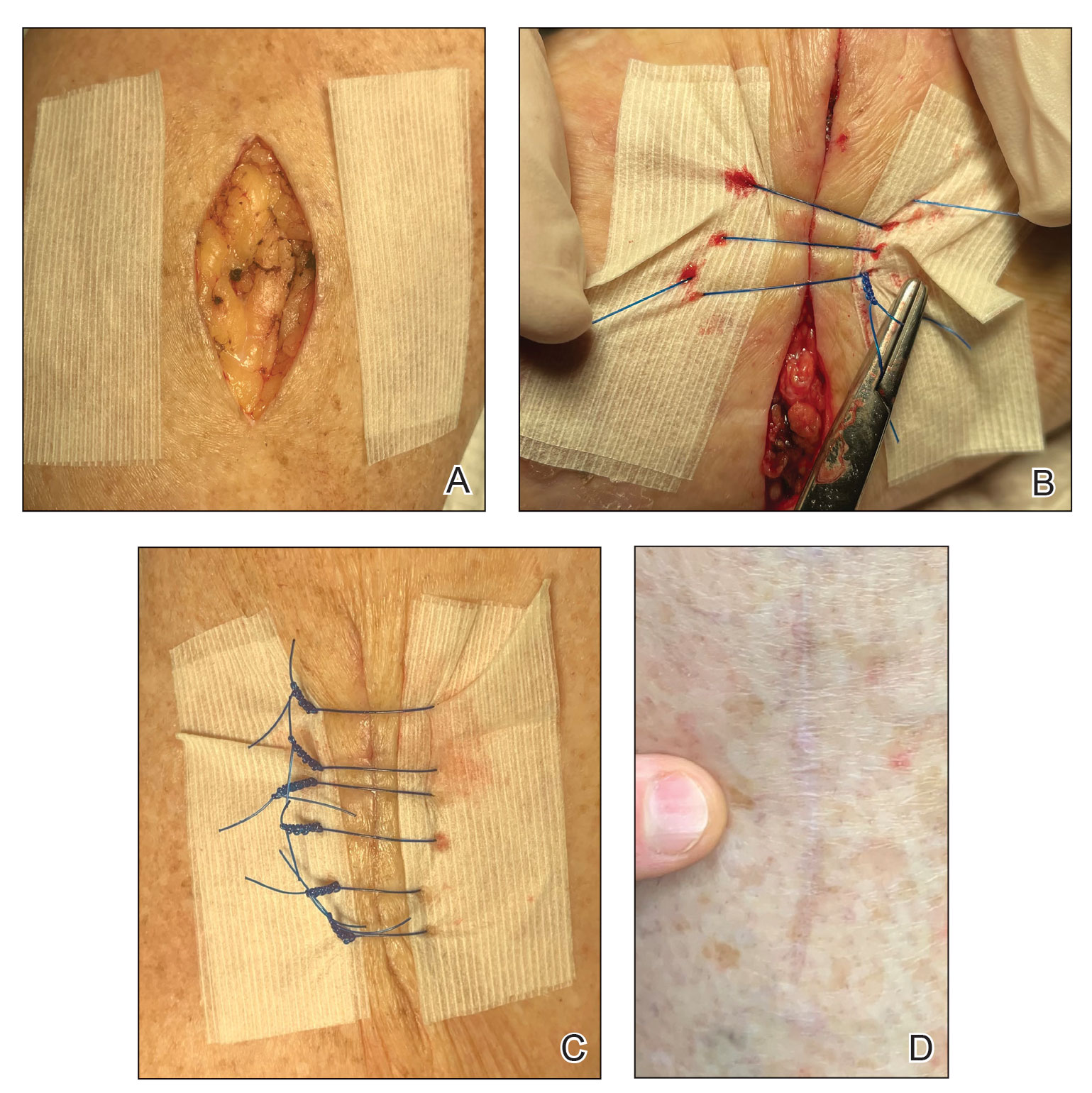

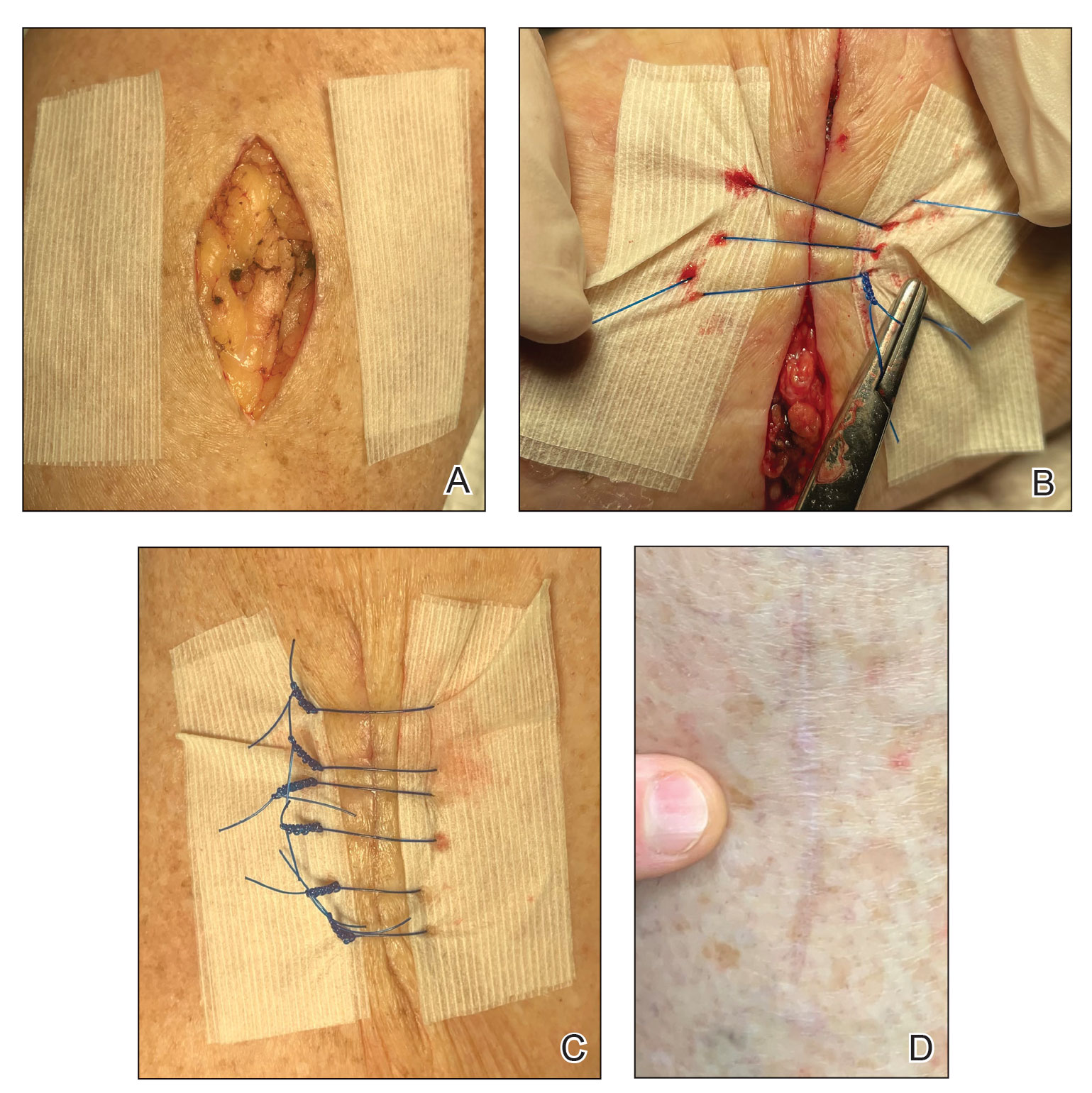

Following tumor clearance on the scalp (Figure 1), wide undermining is performed and 3-0 polyglactin 910 epidermal pulley sutures are placed to partially close the defect. A cadaveric STSG is placed over the remaining exposed periosteum and secured under the pulley sutures (Figure 2). The cadaveric STSG is replaced at 1-week intervals. At 4 weeks, sutures typically are removed. The cadaveric STSG is used until the exposed periosteum is fully granulated and the surgeon decides that granulation arrest is unlikely. The wound then heals by unassisted granulation. This approach provides an excellent final cosmetic outcome while avoiding extensive reconstruction (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

Scalp defects requiring closure are common for dermatologic surgeons. Several techniques to promote tissue granulation in defects that involve exposed periosteum have been reported, including (1) creation of small holes with a scalpel or chisel to access cortical circulation and (2) using laser modalities to stimulate granulation (eg, an erbium:YAG or CO2 laser).3,4 Although direct comparative studies are needed, the cadaveric STSG provides an approach that increases tissue granulation but does not require more invasive techniques or equipment.

Autologous STSGs need a wound bed and can fail with an exposed periosteum. Furthermore, an autologous STSG that survives may leave an unsightly, hypopigmented, depressed defect. When a defect involves the periosteum and a primary closure or flap is not ideal, a skin substitute may be an option.

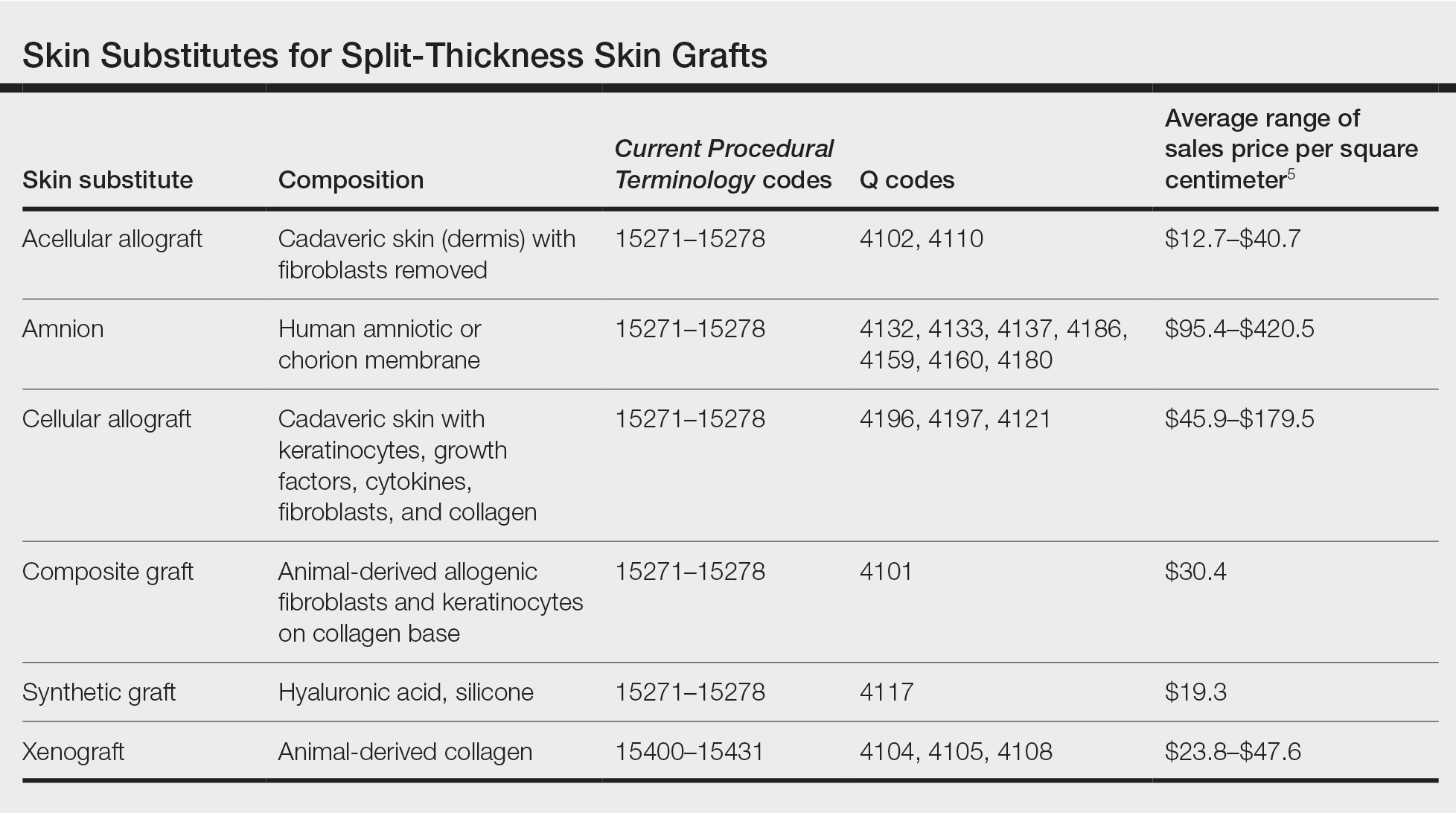

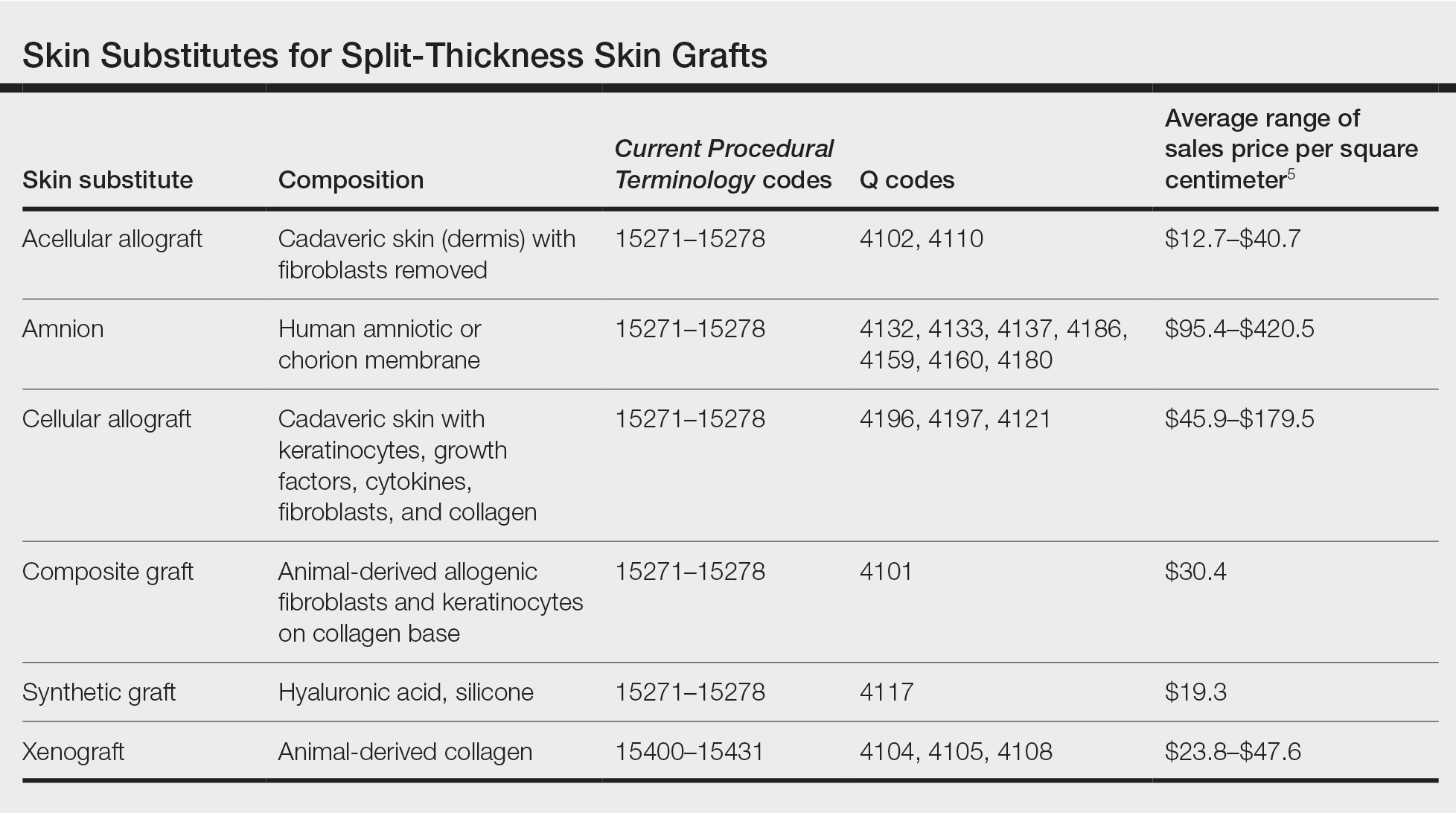

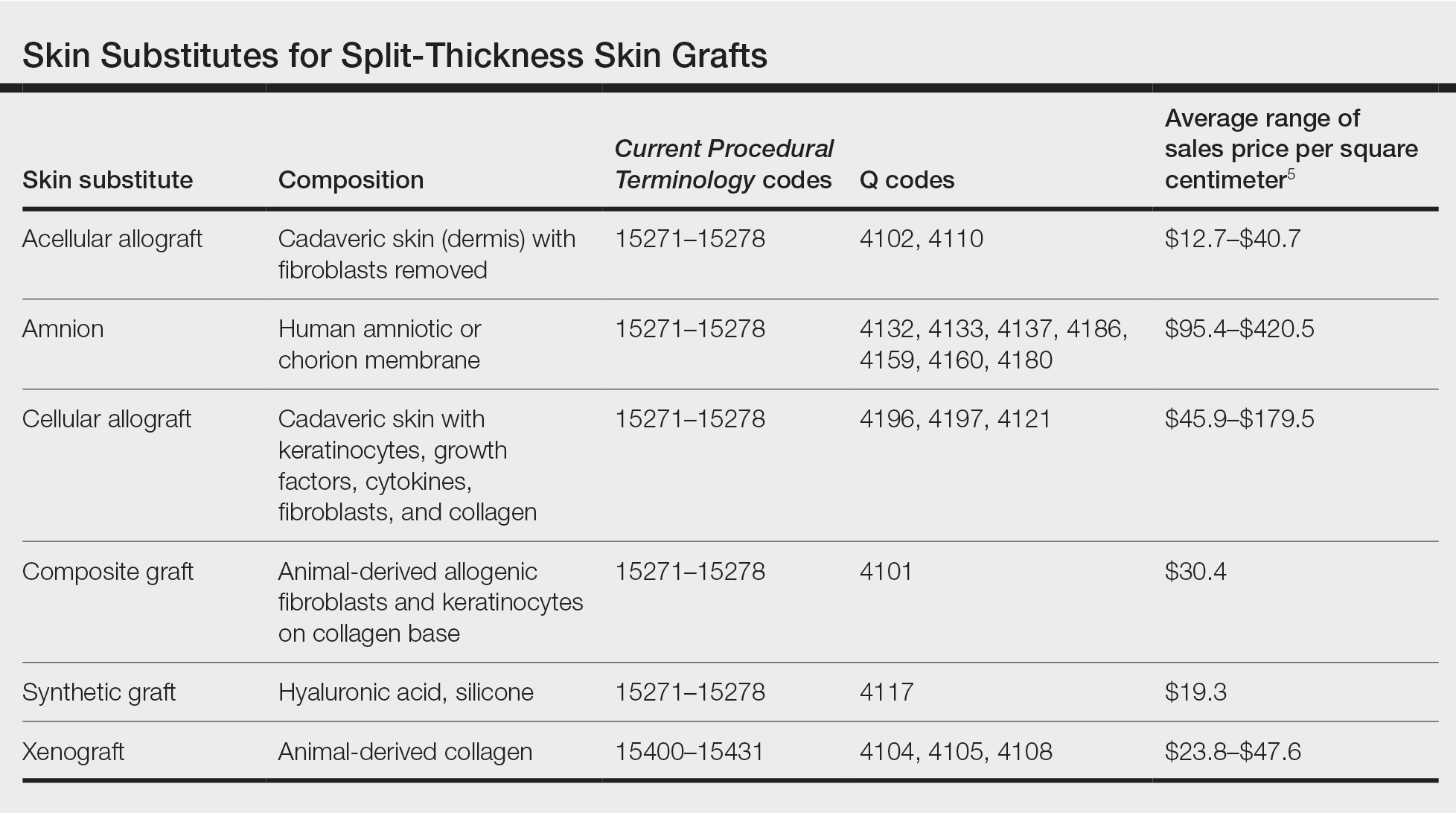

Skin substitutes, including cadaveric STSG, generally are classified as bioengineered skin equivalents, amniotic tissue, or cadaveric bioproducts (Table). Unlike autologous grafts, these skin substitutes can provide rapid coverage of the defect and do not require a highly vascularized wound bed.6 They also minimize the inflammatory response and potentially improve the final cosmetic outcome by improving granulation rather than immediate STSG closure creating a step-off in deep wounds.6

Cadaveric STSGs also have been used in nonhealing ulcerations; diabetic foot ulcers; and ulcerations in which muscle, tendon, or bone are exposed, demonstrating induction of wound healing with superior scar quality and skin function.2,7,8 The utility of the cadaveric STSG is further highlighted by its potential to reduce costs9 compared to bioengineered skin substitutes, though considerable variability exists in pricing (Table).

Consider using a cadaveric STSG with a guiding closure in cases in which there is concern for delayed or absent tissue granulation or when monitoring for recurrence is essential.

- Jibbe A, Tolkachjov SN. An efficient single-layer suture technique for large scalp flaps. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E395-E396. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.062

- Mosti G, Mattaliano V, Magliaro A, et al. Cadaveric skin grafts may greatly increase the healing rate of recalcitrant ulcers when used both alone and in combination with split-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:169-179. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001990

- Valesky EM, Vogl T, Kaufmann R, et al. Trepanation or complete removal of the outer table of the calvarium for granulation induction: the erbium:YAG laser as an alternative to the rose head burr. Dermatology. 2015;230:276-281. doi:10.1159/000368749

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH. Scalpel-made holes on exposed scalp bone to promote second intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.020

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 2023 ASP Pricing. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/asp-pricing-files

- Shores JT, Gabriel A, Gupta S. Skin substitutes and alternatives: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(9 Pt 1):493-508. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000288217.83128.f3

- Li X, Meng X, Wang X, et al. Human acellular dermal matrix allograft: a randomized, controlled human trial for the long-term evaluation of patients with extensive burns. Burns. 2015;41:689-699. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.12.007

- Juhasz I, Kiss B, Lukacs L, et al. Long-term followup of dermal substitution with acellular dermal implant in burns and postburn scar corrections. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:210150. doi:10.1155/2010/210150

- Towler MA, Rush EW, Richardson MK, et al. Randomized, prospective, blinded-enrollment, head-to-head venous leg ulcer healing trial comparing living, bioengineered skin graft substitute (Apligraf) with living, cryopreserved, human skin allograft (TheraSkin). Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:357-365. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2018.02.006

Practice Gap

Scalp defects that extend to or below the periosteum often pose a reconstructive conundrum. Secondary-intention healing is challenging without an intact periosteum, and complex rotational flaps are required in these scenarios.1 For a tumor that is at high risk for recurrence or when adjuvant therapy is necessary, tissue distortion of flaps can make monitoring for recurrence difficult. Similarly, for patients in poor health or who are elderly and have substantial skin atrophy, extensive closure may be undesirable or more technically challenging with a higher risk for adverse events. In these scenarios, additional strategies are necessary to optimize wound healing and cosmesis. A cadaveric split-thickness skin graft (STSG) consisting of biologically active tissue can be used to expedite granulation.2

Technique

Following tumor clearance on the scalp (Figure 1), wide undermining is performed and 3-0 polyglactin 910 epidermal pulley sutures are placed to partially close the defect. A cadaveric STSG is placed over the remaining exposed periosteum and secured under the pulley sutures (Figure 2). The cadaveric STSG is replaced at 1-week intervals. At 4 weeks, sutures typically are removed. The cadaveric STSG is used until the exposed periosteum is fully granulated and the surgeon decides that granulation arrest is unlikely. The wound then heals by unassisted granulation. This approach provides an excellent final cosmetic outcome while avoiding extensive reconstruction (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

Scalp defects requiring closure are common for dermatologic surgeons. Several techniques to promote tissue granulation in defects that involve exposed periosteum have been reported, including (1) creation of small holes with a scalpel or chisel to access cortical circulation and (2) using laser modalities to stimulate granulation (eg, an erbium:YAG or CO2 laser).3,4 Although direct comparative studies are needed, the cadaveric STSG provides an approach that increases tissue granulation but does not require more invasive techniques or equipment.

Autologous STSGs need a wound bed and can fail with an exposed periosteum. Furthermore, an autologous STSG that survives may leave an unsightly, hypopigmented, depressed defect. When a defect involves the periosteum and a primary closure or flap is not ideal, a skin substitute may be an option.

Skin substitutes, including cadaveric STSG, generally are classified as bioengineered skin equivalents, amniotic tissue, or cadaveric bioproducts (Table). Unlike autologous grafts, these skin substitutes can provide rapid coverage of the defect and do not require a highly vascularized wound bed.6 They also minimize the inflammatory response and potentially improve the final cosmetic outcome by improving granulation rather than immediate STSG closure creating a step-off in deep wounds.6

Cadaveric STSGs also have been used in nonhealing ulcerations; diabetic foot ulcers; and ulcerations in which muscle, tendon, or bone are exposed, demonstrating induction of wound healing with superior scar quality and skin function.2,7,8 The utility of the cadaveric STSG is further highlighted by its potential to reduce costs9 compared to bioengineered skin substitutes, though considerable variability exists in pricing (Table).

Consider using a cadaveric STSG with a guiding closure in cases in which there is concern for delayed or absent tissue granulation or when monitoring for recurrence is essential.

Practice Gap

Scalp defects that extend to or below the periosteum often pose a reconstructive conundrum. Secondary-intention healing is challenging without an intact periosteum, and complex rotational flaps are required in these scenarios.1 For a tumor that is at high risk for recurrence or when adjuvant therapy is necessary, tissue distortion of flaps can make monitoring for recurrence difficult. Similarly, for patients in poor health or who are elderly and have substantial skin atrophy, extensive closure may be undesirable or more technically challenging with a higher risk for adverse events. In these scenarios, additional strategies are necessary to optimize wound healing and cosmesis. A cadaveric split-thickness skin graft (STSG) consisting of biologically active tissue can be used to expedite granulation.2

Technique

Following tumor clearance on the scalp (Figure 1), wide undermining is performed and 3-0 polyglactin 910 epidermal pulley sutures are placed to partially close the defect. A cadaveric STSG is placed over the remaining exposed periosteum and secured under the pulley sutures (Figure 2). The cadaveric STSG is replaced at 1-week intervals. At 4 weeks, sutures typically are removed. The cadaveric STSG is used until the exposed periosteum is fully granulated and the surgeon decides that granulation arrest is unlikely. The wound then heals by unassisted granulation. This approach provides an excellent final cosmetic outcome while avoiding extensive reconstruction (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

Scalp defects requiring closure are common for dermatologic surgeons. Several techniques to promote tissue granulation in defects that involve exposed periosteum have been reported, including (1) creation of small holes with a scalpel or chisel to access cortical circulation and (2) using laser modalities to stimulate granulation (eg, an erbium:YAG or CO2 laser).3,4 Although direct comparative studies are needed, the cadaveric STSG provides an approach that increases tissue granulation but does not require more invasive techniques or equipment.

Autologous STSGs need a wound bed and can fail with an exposed periosteum. Furthermore, an autologous STSG that survives may leave an unsightly, hypopigmented, depressed defect. When a defect involves the periosteum and a primary closure or flap is not ideal, a skin substitute may be an option.

Skin substitutes, including cadaveric STSG, generally are classified as bioengineered skin equivalents, amniotic tissue, or cadaveric bioproducts (Table). Unlike autologous grafts, these skin substitutes can provide rapid coverage of the defect and do not require a highly vascularized wound bed.6 They also minimize the inflammatory response and potentially improve the final cosmetic outcome by improving granulation rather than immediate STSG closure creating a step-off in deep wounds.6

Cadaveric STSGs also have been used in nonhealing ulcerations; diabetic foot ulcers; and ulcerations in which muscle, tendon, or bone are exposed, demonstrating induction of wound healing with superior scar quality and skin function.2,7,8 The utility of the cadaveric STSG is further highlighted by its potential to reduce costs9 compared to bioengineered skin substitutes, though considerable variability exists in pricing (Table).

Consider using a cadaveric STSG with a guiding closure in cases in which there is concern for delayed or absent tissue granulation or when monitoring for recurrence is essential.

- Jibbe A, Tolkachjov SN. An efficient single-layer suture technique for large scalp flaps. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E395-E396. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.062

- Mosti G, Mattaliano V, Magliaro A, et al. Cadaveric skin grafts may greatly increase the healing rate of recalcitrant ulcers when used both alone and in combination with split-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:169-179. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001990

- Valesky EM, Vogl T, Kaufmann R, et al. Trepanation or complete removal of the outer table of the calvarium for granulation induction: the erbium:YAG laser as an alternative to the rose head burr. Dermatology. 2015;230:276-281. doi:10.1159/000368749

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH. Scalpel-made holes on exposed scalp bone to promote second intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.020

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 2023 ASP Pricing. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/asp-pricing-files

- Shores JT, Gabriel A, Gupta S. Skin substitutes and alternatives: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(9 Pt 1):493-508. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000288217.83128.f3

- Li X, Meng X, Wang X, et al. Human acellular dermal matrix allograft: a randomized, controlled human trial for the long-term evaluation of patients with extensive burns. Burns. 2015;41:689-699. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.12.007

- Juhasz I, Kiss B, Lukacs L, et al. Long-term followup of dermal substitution with acellular dermal implant in burns and postburn scar corrections. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:210150. doi:10.1155/2010/210150

- Towler MA, Rush EW, Richardson MK, et al. Randomized, prospective, blinded-enrollment, head-to-head venous leg ulcer healing trial comparing living, bioengineered skin graft substitute (Apligraf) with living, cryopreserved, human skin allograft (TheraSkin). Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:357-365. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2018.02.006

- Jibbe A, Tolkachjov SN. An efficient single-layer suture technique for large scalp flaps. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E395-E396. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.062

- Mosti G, Mattaliano V, Magliaro A, et al. Cadaveric skin grafts may greatly increase the healing rate of recalcitrant ulcers when used both alone and in combination with split-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:169-179. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001990

- Valesky EM, Vogl T, Kaufmann R, et al. Trepanation or complete removal of the outer table of the calvarium for granulation induction: the erbium:YAG laser as an alternative to the rose head burr. Dermatology. 2015;230:276-281. doi:10.1159/000368749

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH. Scalpel-made holes on exposed scalp bone to promote second intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.020

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 2023 ASP Pricing. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/asp-pricing-files

- Shores JT, Gabriel A, Gupta S. Skin substitutes and alternatives: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(9 Pt 1):493-508. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000288217.83128.f3

- Li X, Meng X, Wang X, et al. Human acellular dermal matrix allograft: a randomized, controlled human trial for the long-term evaluation of patients with extensive burns. Burns. 2015;41:689-699. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.12.007

- Juhasz I, Kiss B, Lukacs L, et al. Long-term followup of dermal substitution with acellular dermal implant in burns and postburn scar corrections. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:210150. doi:10.1155/2010/210150

- Towler MA, Rush EW, Richardson MK, et al. Randomized, prospective, blinded-enrollment, head-to-head venous leg ulcer healing trial comparing living, bioengineered skin graft substitute (Apligraf) with living, cryopreserved, human skin allograft (TheraSkin). Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:357-365. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2018.02.006

Affixing a Scalp Dressing With Hairpins

Practice Gap

Wound dressings protect the skin and prevent contamination. The hair often makes it difficult to affix a dressing after a minor scalp trauma or local surgery on the head. Traditional approaches for fastening a dressing on the head include bandage winding or adhesive tape, but these methods often affect aesthetics or cause discomfort—bandage winding can make it inconvenient for the patient to move their head, and adhesive tape can cause pain by pulling the hair during removal.

To better position a scalp dressing, tie-over dressings, braid dressings, and paper clips have been used as fixators.1-3 These methods have benefits and disadvantages.

Tie-over Dressing—The dressing is clasped with long sutures that were reserved during wound closure. This method is sturdy, can slightly compress the wound, and is applicable to any part of the scalp. However, it requires more sutures, and more careful wound care may be required due to the edge of the dressing being close to the wound.

Braid Dressing—Tape, a rubber band, or braided hair is used to bind the gauze pad. This dressing is simple and inexpensive. However, it is limited to patients with long hair; even then, it often is difficult to anchor the dressing by braiding hair. Moreover, removal of the rubber band and tape can cause discomfort or pain.

Paper Clip—This is a simple scalp dressing fixator. However, due to the short and circular structure of the clip, it is not conducive to affixing a gauze dressing for patients with short hair, and it often hooks the gauze and hair, making it inconvenient for the physician and a source of discomfort for the patient when the paper clip is being removed.

The Technique

To address shortcomings of traditional methods, we encourage the use of hairpins to affix a dressing after a scalp wound is sutured. Two steps are required:

- Position the gauze to cover the wound and press the gauze down with your hand.

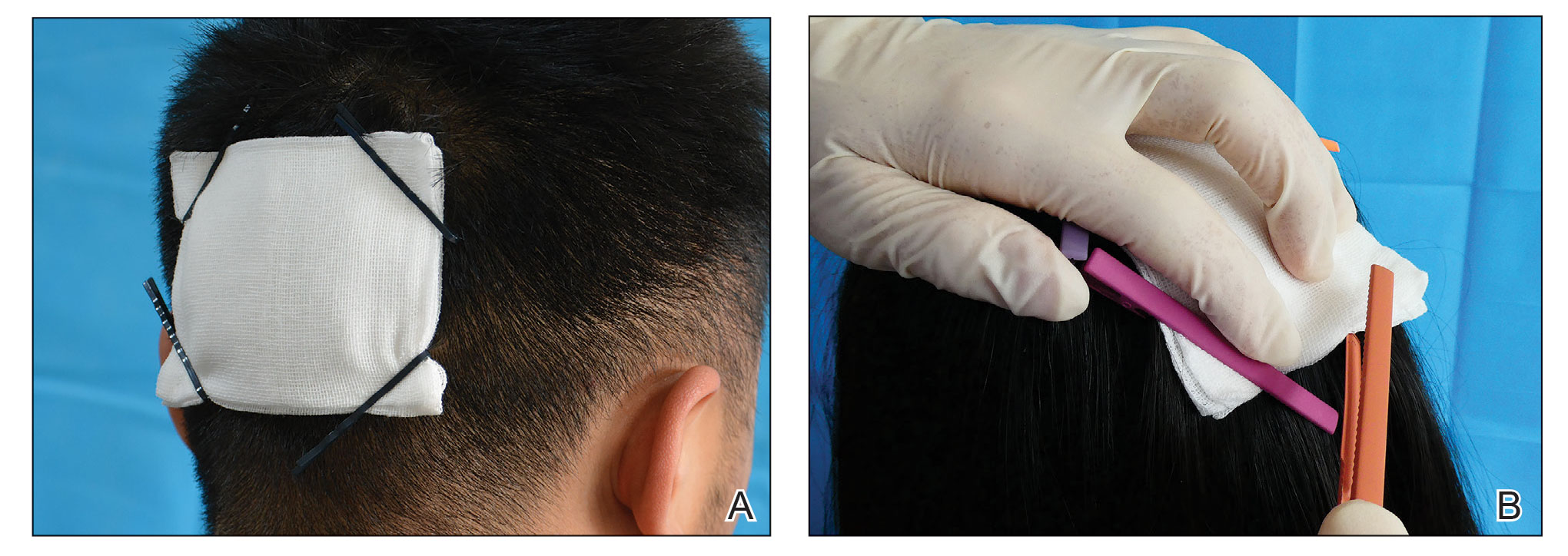

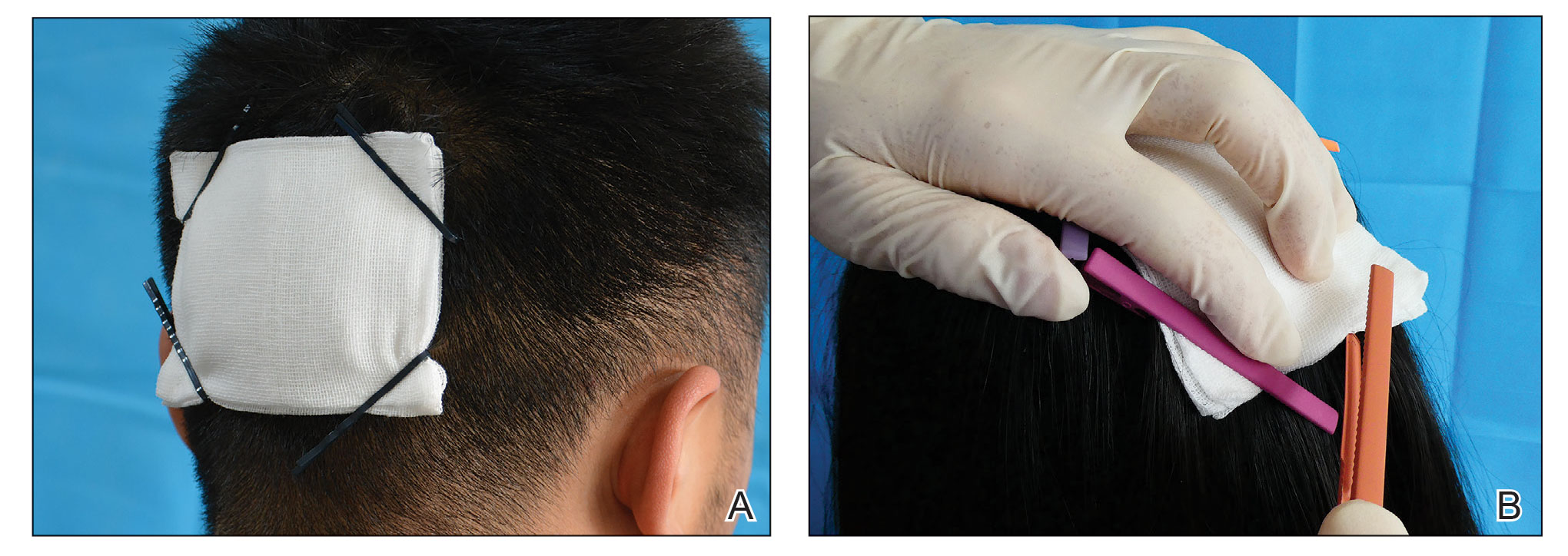

- Clamp the 4 corners of the dressing and adjacent hair with hairpins (Figure, A).

Practical Implications

Hairpins are common for fixing hairstyles and decorating hair. They are inexpensive, easy to obtain, simple in structure, convenient to use without additional discomfort, and easy to remove (Figure, B). Because most hairpins have a powerful clamping force, they can affix dressings in short hair (Figure, A). All medical staff can use hairpins to anchor the scalp dressing. Even a patient’s family members can carry out simple dressing replacement and wound cleaning using this method. Patients also have many options for hairpin styles, which is especially useful in easing the apprehension of surgery in pediatric patients.

- Ginzburg A, Mutalik S. Another method of tie-over dressing for surgical wounds of hair-bearing areas. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:893-894. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.99155.x

- Yanaka K, Nose T. Braid dressing for hair-bearing scalp wound. Neurocrit Care. 2004;1:217-218. doi:10.1385/NCC:1:2:217

- Bu W, Zhang Q, Fang F, et al. Fixation of head dressing gauzes with paper clips is similar to and better than using tape. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E95-E96. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.046

Practice Gap

Wound dressings protect the skin and prevent contamination. The hair often makes it difficult to affix a dressing after a minor scalp trauma or local surgery on the head. Traditional approaches for fastening a dressing on the head include bandage winding or adhesive tape, but these methods often affect aesthetics or cause discomfort—bandage winding can make it inconvenient for the patient to move their head, and adhesive tape can cause pain by pulling the hair during removal.

To better position a scalp dressing, tie-over dressings, braid dressings, and paper clips have been used as fixators.1-3 These methods have benefits and disadvantages.

Tie-over Dressing—The dressing is clasped with long sutures that were reserved during wound closure. This method is sturdy, can slightly compress the wound, and is applicable to any part of the scalp. However, it requires more sutures, and more careful wound care may be required due to the edge of the dressing being close to the wound.

Braid Dressing—Tape, a rubber band, or braided hair is used to bind the gauze pad. This dressing is simple and inexpensive. However, it is limited to patients with long hair; even then, it often is difficult to anchor the dressing by braiding hair. Moreover, removal of the rubber band and tape can cause discomfort or pain.

Paper Clip—This is a simple scalp dressing fixator. However, due to the short and circular structure of the clip, it is not conducive to affixing a gauze dressing for patients with short hair, and it often hooks the gauze and hair, making it inconvenient for the physician and a source of discomfort for the patient when the paper clip is being removed.

The Technique

To address shortcomings of traditional methods, we encourage the use of hairpins to affix a dressing after a scalp wound is sutured. Two steps are required:

- Position the gauze to cover the wound and press the gauze down with your hand.

- Clamp the 4 corners of the dressing and adjacent hair with hairpins (Figure, A).

Practical Implications

Hairpins are common for fixing hairstyles and decorating hair. They are inexpensive, easy to obtain, simple in structure, convenient to use without additional discomfort, and easy to remove (Figure, B). Because most hairpins have a powerful clamping force, they can affix dressings in short hair (Figure, A). All medical staff can use hairpins to anchor the scalp dressing. Even a patient’s family members can carry out simple dressing replacement and wound cleaning using this method. Patients also have many options for hairpin styles, which is especially useful in easing the apprehension of surgery in pediatric patients.

Practice Gap

Wound dressings protect the skin and prevent contamination. The hair often makes it difficult to affix a dressing after a minor scalp trauma or local surgery on the head. Traditional approaches for fastening a dressing on the head include bandage winding or adhesive tape, but these methods often affect aesthetics or cause discomfort—bandage winding can make it inconvenient for the patient to move their head, and adhesive tape can cause pain by pulling the hair during removal.

To better position a scalp dressing, tie-over dressings, braid dressings, and paper clips have been used as fixators.1-3 These methods have benefits and disadvantages.

Tie-over Dressing—The dressing is clasped with long sutures that were reserved during wound closure. This method is sturdy, can slightly compress the wound, and is applicable to any part of the scalp. However, it requires more sutures, and more careful wound care may be required due to the edge of the dressing being close to the wound.

Braid Dressing—Tape, a rubber band, or braided hair is used to bind the gauze pad. This dressing is simple and inexpensive. However, it is limited to patients with long hair; even then, it often is difficult to anchor the dressing by braiding hair. Moreover, removal of the rubber band and tape can cause discomfort or pain.

Paper Clip—This is a simple scalp dressing fixator. However, due to the short and circular structure of the clip, it is not conducive to affixing a gauze dressing for patients with short hair, and it often hooks the gauze and hair, making it inconvenient for the physician and a source of discomfort for the patient when the paper clip is being removed.

The Technique

To address shortcomings of traditional methods, we encourage the use of hairpins to affix a dressing after a scalp wound is sutured. Two steps are required:

- Position the gauze to cover the wound and press the gauze down with your hand.

- Clamp the 4 corners of the dressing and adjacent hair with hairpins (Figure, A).

Practical Implications

Hairpins are common for fixing hairstyles and decorating hair. They are inexpensive, easy to obtain, simple in structure, convenient to use without additional discomfort, and easy to remove (Figure, B). Because most hairpins have a powerful clamping force, they can affix dressings in short hair (Figure, A). All medical staff can use hairpins to anchor the scalp dressing. Even a patient’s family members can carry out simple dressing replacement and wound cleaning using this method. Patients also have many options for hairpin styles, which is especially useful in easing the apprehension of surgery in pediatric patients.

- Ginzburg A, Mutalik S. Another method of tie-over dressing for surgical wounds of hair-bearing areas. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:893-894. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.99155.x

- Yanaka K, Nose T. Braid dressing for hair-bearing scalp wound. Neurocrit Care. 2004;1:217-218. doi:10.1385/NCC:1:2:217

- Bu W, Zhang Q, Fang F, et al. Fixation of head dressing gauzes with paper clips is similar to and better than using tape. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E95-E96. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.046

- Ginzburg A, Mutalik S. Another method of tie-over dressing for surgical wounds of hair-bearing areas. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:893-894. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.99155.x

- Yanaka K, Nose T. Braid dressing for hair-bearing scalp wound. Neurocrit Care. 2004;1:217-218. doi:10.1385/NCC:1:2:217

- Bu W, Zhang Q, Fang F, et al. Fixation of head dressing gauzes with paper clips is similar to and better than using tape. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E95-E96. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.046

Use of the Retroauricular Pull-Through Sandwich Flap for Repair of an Extensive Conchal Bowl Defect With Complete Cartilage Loss

Practice Gap

Repair of a conchal defect requires careful consideration to achieve an optimal outcome. Reconstruction should resurface exposed cartilage, restore the natural projection of the auricle, and direct sound into the external auditory meatus. Patients also should be able to wear glasses and a hearing aid.

The reconstructive ladder for most conchal bowl defects includes secondary intention healing, full-thickness skin grafting (FTSG), and either a revolving-door flap or a flip-flop flap. Secondary intention and FTSG are appropriate for superficial defects, in which the loss of cartilage is not substantial.1,2 Revolving-door and flip-flop flaps are single-stage retroauricular approaches used to repair relatively small defects of the conchal bowl.3 However, reconstructive options are limited for a large defect in which there is extensive loss of cartilage; 3-stage retroauricular approaches have been utilized. The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap is a 3-stage repair that can be utilized to reconstruct a through-and-through defect of the central ear:

- Stage 1: an anteriorly based retroauricular pedicle is incised, hinged over, and sutured to the medial aspect of the defect, resurfacing the posterior ear.

- Stage 2: the pedicle is severed and the flap is folded on itself to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 3: the folded edge is de-epithelialized and set into the lateral defect.4

The revolving-door flap also uses a 3-stage approach and is utilized for a full-thickness central auricular defect:

- Stage 1: a revolving-door flap is used to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 2: a cartilage graft provides structural support.

- Stage 3: division and inset with an FTSG is used to resurface the posterior ear.

The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap and revolving-door flap techniques are useful for defects when there is intact posterior auricular skin but not when there is extensive loss of cartilage. Other downsides to these 3-stage approaches are the time and multiple procedures required.5

We describe the technique of a retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap for repair of a large conchal bowl defect with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Technique

A 62-year-old man presented for treatment of a 2.6×2.4-cm nodular and infiltrative basal cell carcinoma of the right conchal bowl. The tumor was cleared with 3 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery, resulting in a 5.5×4.2-cm defect with complete loss of cartilage throughout the concha, helical crus, and inner rim of the antihelix (Figure 1). A 2-stage repair was performed utilizing a cartilage graft and a pull-through retroauricular interpolation flap.

Stage 1—A cartilage graft was harvested from the left concha and sutured into the central defect for structural support (Figure 2). An incision was then made through the posterior auricular skin, just medial to the residual antihelical cartilage, and a retroauricular interpolation flap was pulled through this incision to resurface the lateral two-thirds of the conchal bowl defect. This created a “sandwich” of tissue, with the following layers (ordered from anterior to posterior): retroauricular interpolation flap, cartilage graft, and intact posterior auricular skin.

A preauricular banner transposition flap was used to repair the medial one-third of the conchal defect. A small area was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 3).

Stage 2—The patient returned 3 weeks later for division and inset of the retroauricular interpolation flap. The pedicle of the flap was severed and its free edge was sutured into the lateral aspect of the defect. The posterior auricular incision that the flap had been pulled through in stage 1 of the repair was closed in a layered fashion, and the secondary defect of the postauricular scalp was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 4).

Final Results—At follow-up 1 month later, the patient was noted to have good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 5).

Practice Implications

The retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap combines a cartilage graft and a retroauricular interpolation flap pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to resurface the anterior ear. This repair is most useful for a large conchal bowl defect in which there is extensive missing cartilage but intact posterior auricular skin.

The retroauricular scalp is a substantial tissue reservoir with robust vasculature; an interpolation flap from this area frequently is used to repair an extensive ear defect. The most common use of an interpolation flap is for a large helical defect; however, the flap also can be pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to the front of the ear in a manner similar to revolving-door and flip-flop flaps, thus allowing for increased flap reach.

A cartilage graft provides structural support, helping to maintain auricular projection. The helical arcades provide a robust vascular supply and maintain viability of the helical rim tissue, despite the large aperture created for the pull-through flap.

We recommend this 2-stage repair for large conchal bowl defects with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

- Clark DP, Hanke CW. Neoplasms of the conchal bowl: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1223-1228. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1988.tb03479.x

- Dessy LA, Figus A, Fioramonti P, et al. Reconstruction of anterior auricular conchal defect after malignancy excision: revolving-door flap versus full-thickness skin graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.073

- Golash A, Bera S, Kanoi AV, et al. The revolving door flap: revisiting an elegant but forgotten flap for ear defect reconstruction. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:64-70. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709531

- Heinz MB, Hölzle F, Ghassemi A. Repairing a non-marginal full-thickness auricular defect using a reversed flap from the postauricular area. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:764-768. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.11.005

- Leitenberger JJ, Golden SK. Reconstruction after full-thickness loss of the antihelix, scapha, and triangular fossa. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:893-896. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000664

Practice Gap

Repair of a conchal defect requires careful consideration to achieve an optimal outcome. Reconstruction should resurface exposed cartilage, restore the natural projection of the auricle, and direct sound into the external auditory meatus. Patients also should be able to wear glasses and a hearing aid.

The reconstructive ladder for most conchal bowl defects includes secondary intention healing, full-thickness skin grafting (FTSG), and either a revolving-door flap or a flip-flop flap. Secondary intention and FTSG are appropriate for superficial defects, in which the loss of cartilage is not substantial.1,2 Revolving-door and flip-flop flaps are single-stage retroauricular approaches used to repair relatively small defects of the conchal bowl.3 However, reconstructive options are limited for a large defect in which there is extensive loss of cartilage; 3-stage retroauricular approaches have been utilized. The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap is a 3-stage repair that can be utilized to reconstruct a through-and-through defect of the central ear:

- Stage 1: an anteriorly based retroauricular pedicle is incised, hinged over, and sutured to the medial aspect of the defect, resurfacing the posterior ear.

- Stage 2: the pedicle is severed and the flap is folded on itself to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 3: the folded edge is de-epithelialized and set into the lateral defect.4

The revolving-door flap also uses a 3-stage approach and is utilized for a full-thickness central auricular defect:

- Stage 1: a revolving-door flap is used to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 2: a cartilage graft provides structural support.

- Stage 3: division and inset with an FTSG is used to resurface the posterior ear.

The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap and revolving-door flap techniques are useful for defects when there is intact posterior auricular skin but not when there is extensive loss of cartilage. Other downsides to these 3-stage approaches are the time and multiple procedures required.5

We describe the technique of a retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap for repair of a large conchal bowl defect with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Technique

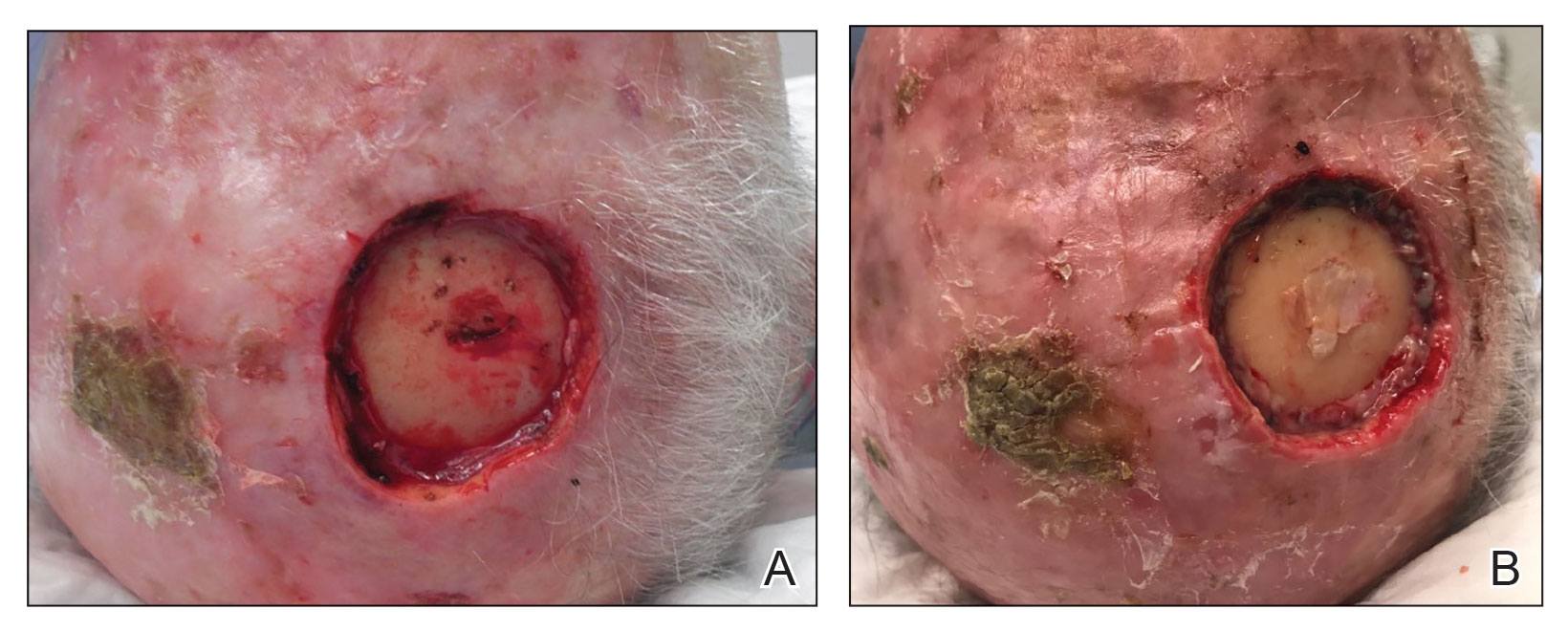

A 62-year-old man presented for treatment of a 2.6×2.4-cm nodular and infiltrative basal cell carcinoma of the right conchal bowl. The tumor was cleared with 3 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery, resulting in a 5.5×4.2-cm defect with complete loss of cartilage throughout the concha, helical crus, and inner rim of the antihelix (Figure 1). A 2-stage repair was performed utilizing a cartilage graft and a pull-through retroauricular interpolation flap.

Stage 1—A cartilage graft was harvested from the left concha and sutured into the central defect for structural support (Figure 2). An incision was then made through the posterior auricular skin, just medial to the residual antihelical cartilage, and a retroauricular interpolation flap was pulled through this incision to resurface the lateral two-thirds of the conchal bowl defect. This created a “sandwich” of tissue, with the following layers (ordered from anterior to posterior): retroauricular interpolation flap, cartilage graft, and intact posterior auricular skin.

A preauricular banner transposition flap was used to repair the medial one-third of the conchal defect. A small area was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 3).

Stage 2—The patient returned 3 weeks later for division and inset of the retroauricular interpolation flap. The pedicle of the flap was severed and its free edge was sutured into the lateral aspect of the defect. The posterior auricular incision that the flap had been pulled through in stage 1 of the repair was closed in a layered fashion, and the secondary defect of the postauricular scalp was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 4).

Final Results—At follow-up 1 month later, the patient was noted to have good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 5).

Practice Implications

The retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap combines a cartilage graft and a retroauricular interpolation flap pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to resurface the anterior ear. This repair is most useful for a large conchal bowl defect in which there is extensive missing cartilage but intact posterior auricular skin.

The retroauricular scalp is a substantial tissue reservoir with robust vasculature; an interpolation flap from this area frequently is used to repair an extensive ear defect. The most common use of an interpolation flap is for a large helical defect; however, the flap also can be pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to the front of the ear in a manner similar to revolving-door and flip-flop flaps, thus allowing for increased flap reach.

A cartilage graft provides structural support, helping to maintain auricular projection. The helical arcades provide a robust vascular supply and maintain viability of the helical rim tissue, despite the large aperture created for the pull-through flap.

We recommend this 2-stage repair for large conchal bowl defects with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Practice Gap

Repair of a conchal defect requires careful consideration to achieve an optimal outcome. Reconstruction should resurface exposed cartilage, restore the natural projection of the auricle, and direct sound into the external auditory meatus. Patients also should be able to wear glasses and a hearing aid.

The reconstructive ladder for most conchal bowl defects includes secondary intention healing, full-thickness skin grafting (FTSG), and either a revolving-door flap or a flip-flop flap. Secondary intention and FTSG are appropriate for superficial defects, in which the loss of cartilage is not substantial.1,2 Revolving-door and flip-flop flaps are single-stage retroauricular approaches used to repair relatively small defects of the conchal bowl.3 However, reconstructive options are limited for a large defect in which there is extensive loss of cartilage; 3-stage retroauricular approaches have been utilized. The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap is a 3-stage repair that can be utilized to reconstruct a through-and-through defect of the central ear:

- Stage 1: an anteriorly based retroauricular pedicle is incised, hinged over, and sutured to the medial aspect of the defect, resurfacing the posterior ear.

- Stage 2: the pedicle is severed and the flap is folded on itself to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 3: the folded edge is de-epithelialized and set into the lateral defect.4

The revolving-door flap also uses a 3-stage approach and is utilized for a full-thickness central auricular defect:

- Stage 1: a revolving-door flap is used to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 2: a cartilage graft provides structural support.

- Stage 3: division and inset with an FTSG is used to resurface the posterior ear.

The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap and revolving-door flap techniques are useful for defects when there is intact posterior auricular skin but not when there is extensive loss of cartilage. Other downsides to these 3-stage approaches are the time and multiple procedures required.5

We describe the technique of a retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap for repair of a large conchal bowl defect with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Technique

A 62-year-old man presented for treatment of a 2.6×2.4-cm nodular and infiltrative basal cell carcinoma of the right conchal bowl. The tumor was cleared with 3 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery, resulting in a 5.5×4.2-cm defect with complete loss of cartilage throughout the concha, helical crus, and inner rim of the antihelix (Figure 1). A 2-stage repair was performed utilizing a cartilage graft and a pull-through retroauricular interpolation flap.

Stage 1—A cartilage graft was harvested from the left concha and sutured into the central defect for structural support (Figure 2). An incision was then made through the posterior auricular skin, just medial to the residual antihelical cartilage, and a retroauricular interpolation flap was pulled through this incision to resurface the lateral two-thirds of the conchal bowl defect. This created a “sandwich” of tissue, with the following layers (ordered from anterior to posterior): retroauricular interpolation flap, cartilage graft, and intact posterior auricular skin.

A preauricular banner transposition flap was used to repair the medial one-third of the conchal defect. A small area was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 3).

Stage 2—The patient returned 3 weeks later for division and inset of the retroauricular interpolation flap. The pedicle of the flap was severed and its free edge was sutured into the lateral aspect of the defect. The posterior auricular incision that the flap had been pulled through in stage 1 of the repair was closed in a layered fashion, and the secondary defect of the postauricular scalp was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 4).

Final Results—At follow-up 1 month later, the patient was noted to have good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 5).

Practice Implications

The retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap combines a cartilage graft and a retroauricular interpolation flap pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to resurface the anterior ear. This repair is most useful for a large conchal bowl defect in which there is extensive missing cartilage but intact posterior auricular skin.

The retroauricular scalp is a substantial tissue reservoir with robust vasculature; an interpolation flap from this area frequently is used to repair an extensive ear defect. The most common use of an interpolation flap is for a large helical defect; however, the flap also can be pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to the front of the ear in a manner similar to revolving-door and flip-flop flaps, thus allowing for increased flap reach.

A cartilage graft provides structural support, helping to maintain auricular projection. The helical arcades provide a robust vascular supply and maintain viability of the helical rim tissue, despite the large aperture created for the pull-through flap.

We recommend this 2-stage repair for large conchal bowl defects with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

- Clark DP, Hanke CW. Neoplasms of the conchal bowl: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1223-1228. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1988.tb03479.x

- Dessy LA, Figus A, Fioramonti P, et al. Reconstruction of anterior auricular conchal defect after malignancy excision: revolving-door flap versus full-thickness skin graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.073

- Golash A, Bera S, Kanoi AV, et al. The revolving door flap: revisiting an elegant but forgotten flap for ear defect reconstruction. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:64-70. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709531

- Heinz MB, Hölzle F, Ghassemi A. Repairing a non-marginal full-thickness auricular defect using a reversed flap from the postauricular area. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:764-768. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.11.005

- Leitenberger JJ, Golden SK. Reconstruction after full-thickness loss of the antihelix, scapha, and triangular fossa. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:893-896. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000664

- Clark DP, Hanke CW. Neoplasms of the conchal bowl: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1223-1228. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1988.tb03479.x

- Dessy LA, Figus A, Fioramonti P, et al. Reconstruction of anterior auricular conchal defect after malignancy excision: revolving-door flap versus full-thickness skin graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.073

- Golash A, Bera S, Kanoi AV, et al. The revolving door flap: revisiting an elegant but forgotten flap for ear defect reconstruction. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:64-70. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709531

- Heinz MB, Hölzle F, Ghassemi A. Repairing a non-marginal full-thickness auricular defect using a reversed flap from the postauricular area. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:764-768. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.11.005

- Leitenberger JJ, Golden SK. Reconstruction after full-thickness loss of the antihelix, scapha, and triangular fossa. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:893-896. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000664

Glitter Effects of Nail Art on Optical Coherence Tomography

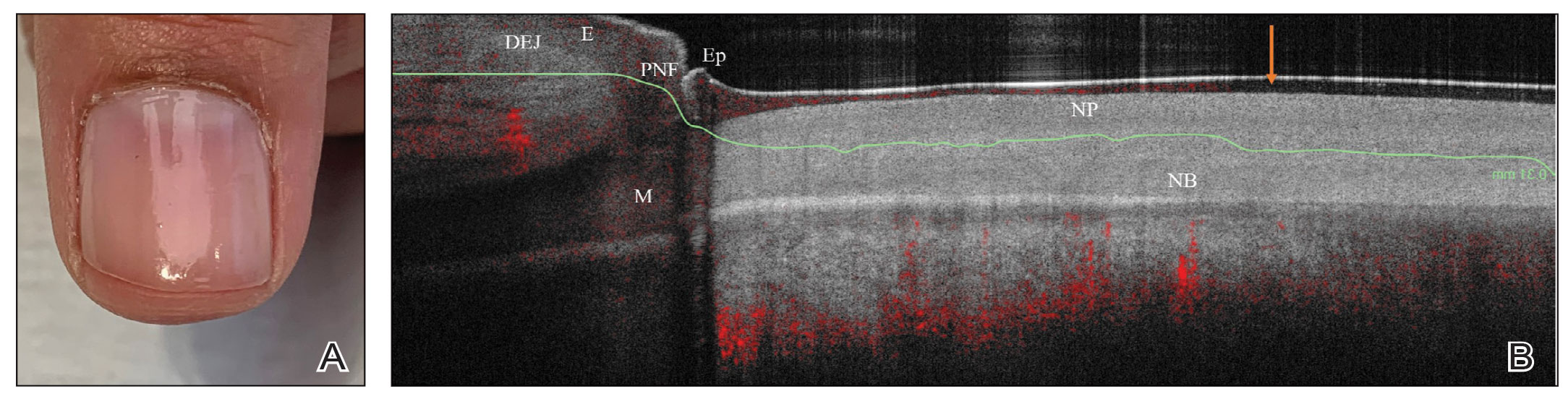

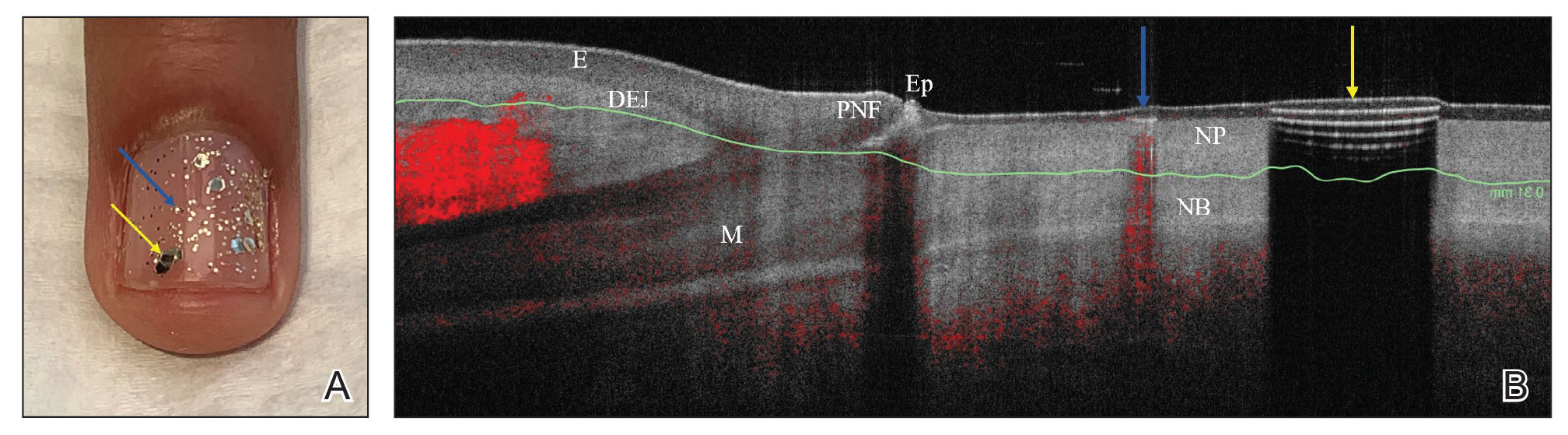

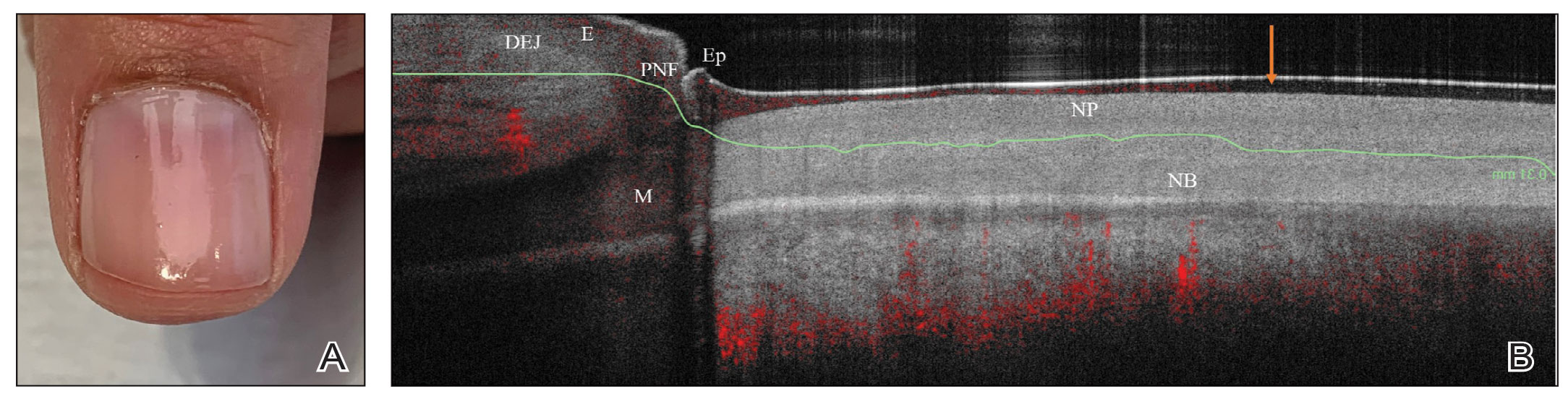

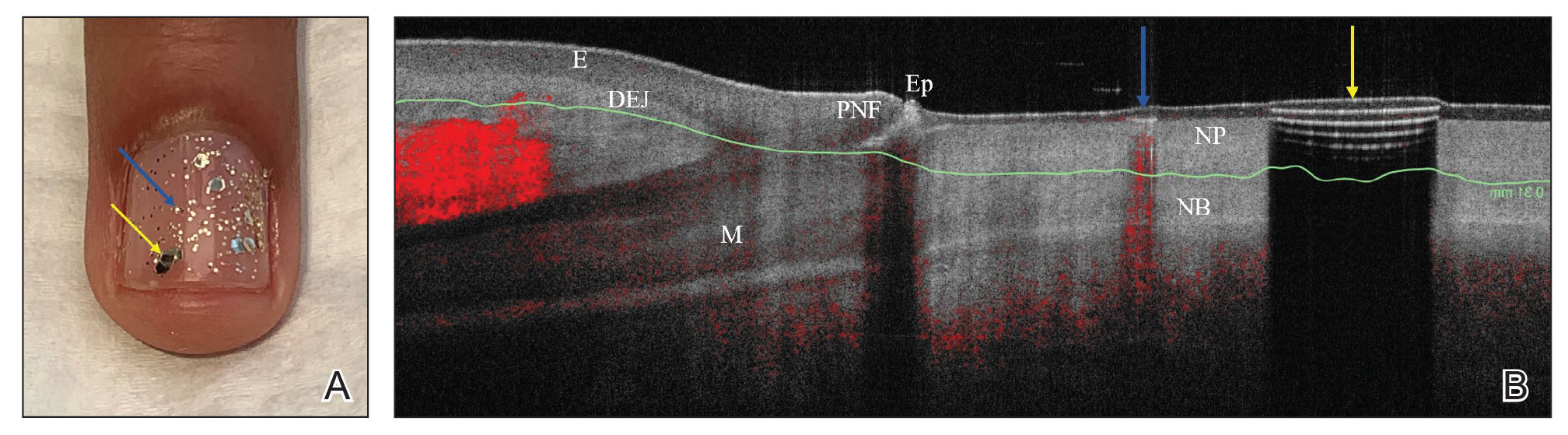

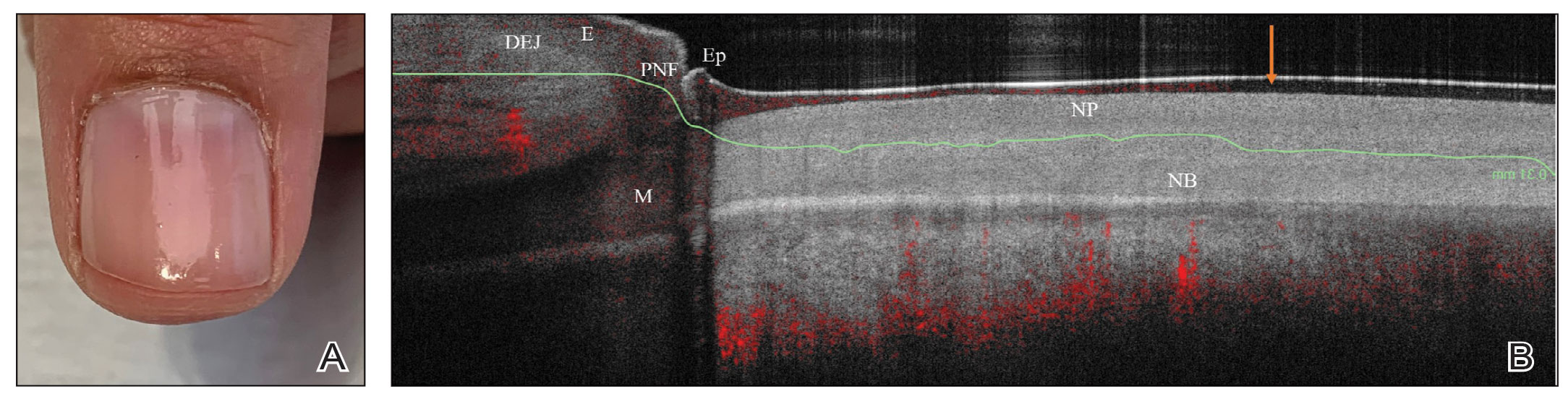

Practice Gap

Nail art can skew the results of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology that is used to visualize nail morphology in diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and onychomycosis, with a penetration depth of 2 mm and high-resolution images.1 Few studies have evaluated the effects of nail art on OCT. Saleah and colleagues1 found that clear, semitransparent, and red nail polishes do not interfere with visualization of the nail plate, whereas nontransparent gel polish and art stones obscure the image. They did not comment on the effect of glitter nail art in their study, though they did test 1 nail that contained glitter.1 Monpeurt et al2 compared matte and glossy nail polishes. They found that matte polish was readily identifiable from the nail plate, whereas glossy polish presented a greater number of artifacts.2

The Solution

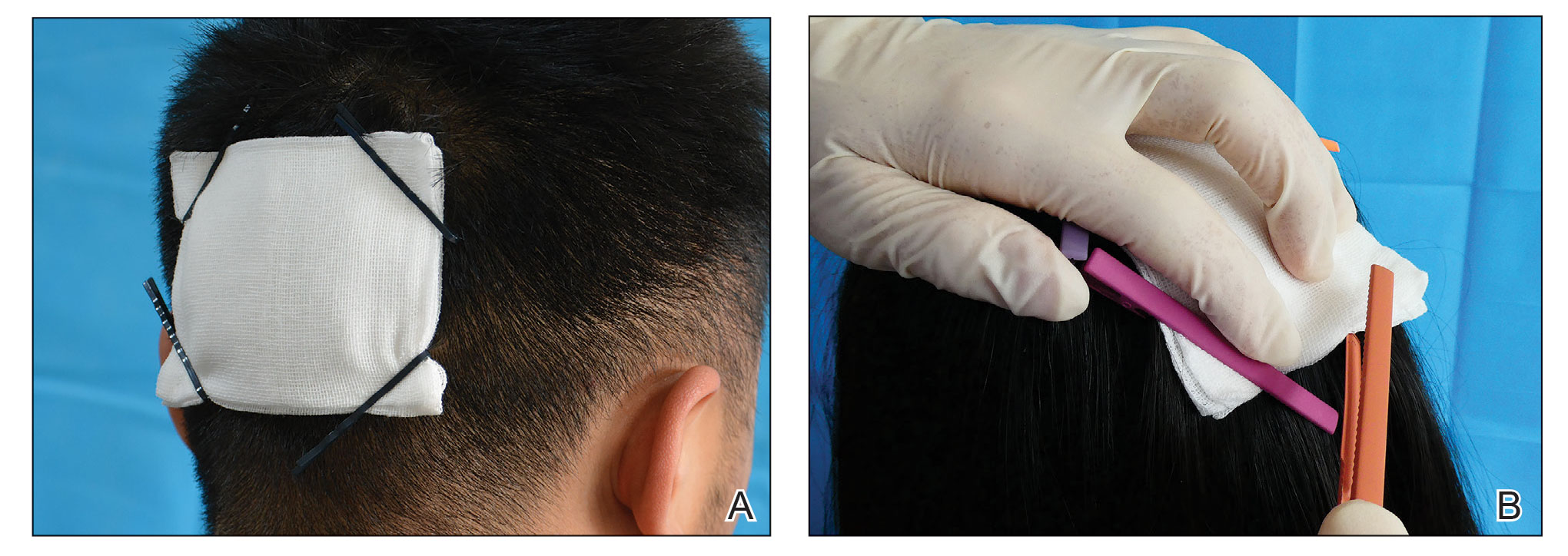

We looked at 3 glitter nail polishes—gold, pink, and silver—that were scanned by OCT to assess the effect of the polish on the resulting image. We determined that glitter particles completely obscured the nail bed and nail plate, regardless of color (Figure 1). Glossy clear polish imparted a distinct film on the top of the nail plate that did not obscure the nail plate or the nail bed (Figure 2).

We conclude that glitter nail polish contains numerous reflective solid particles that interfere with OCT imaging of the nail plate and nail bed. As a result, we recommend removal of nail art to properly assess nail pathology. Because removal may need to be conducted by a nail technician, the treating clinician should inform the patient ahead of time to come to the appointment with bare (ie, unpolished) nails.

Practice Implications

Bringing awareness to the necessity of removing nail art prior to OCT imaging is crucial because many patients partake in its application, and removal may require the involvement of a professional nail technician. If a patient can be made aware that they should remove all nail art in advance, they will be better prepared for an OCT imaging session. Such a protocol increases efficiency, decreases diagnostic delay, and reduces cost associated with multiple office visits.

- Saleah S, Kim P, Seong D, et al. A preliminary study of post-progressive nail-art effects on in vivo nail plate using optical coherence tomography-based intensity profiling assessment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:666. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79497-3

- Monpeurt C, Cinotti E, Hebert M, et al. Thickness and morphology assessment of nail polishes applied on nails by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:156-157. doi:10.1111/srt.12406

Practice Gap

Nail art can skew the results of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology that is used to visualize nail morphology in diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and onychomycosis, with a penetration depth of 2 mm and high-resolution images.1 Few studies have evaluated the effects of nail art on OCT. Saleah and colleagues1 found that clear, semitransparent, and red nail polishes do not interfere with visualization of the nail plate, whereas nontransparent gel polish and art stones obscure the image. They did not comment on the effect of glitter nail art in their study, though they did test 1 nail that contained glitter.1 Monpeurt et al2 compared matte and glossy nail polishes. They found that matte polish was readily identifiable from the nail plate, whereas glossy polish presented a greater number of artifacts.2

The Solution

We looked at 3 glitter nail polishes—gold, pink, and silver—that were scanned by OCT to assess the effect of the polish on the resulting image. We determined that glitter particles completely obscured the nail bed and nail plate, regardless of color (Figure 1). Glossy clear polish imparted a distinct film on the top of the nail plate that did not obscure the nail plate or the nail bed (Figure 2).

We conclude that glitter nail polish contains numerous reflective solid particles that interfere with OCT imaging of the nail plate and nail bed. As a result, we recommend removal of nail art to properly assess nail pathology. Because removal may need to be conducted by a nail technician, the treating clinician should inform the patient ahead of time to come to the appointment with bare (ie, unpolished) nails.

Practice Implications

Bringing awareness to the necessity of removing nail art prior to OCT imaging is crucial because many patients partake in its application, and removal may require the involvement of a professional nail technician. If a patient can be made aware that they should remove all nail art in advance, they will be better prepared for an OCT imaging session. Such a protocol increases efficiency, decreases diagnostic delay, and reduces cost associated with multiple office visits.

Practice Gap

Nail art can skew the results of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology that is used to visualize nail morphology in diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and onychomycosis, with a penetration depth of 2 mm and high-resolution images.1 Few studies have evaluated the effects of nail art on OCT. Saleah and colleagues1 found that clear, semitransparent, and red nail polishes do not interfere with visualization of the nail plate, whereas nontransparent gel polish and art stones obscure the image. They did not comment on the effect of glitter nail art in their study, though they did test 1 nail that contained glitter.1 Monpeurt et al2 compared matte and glossy nail polishes. They found that matte polish was readily identifiable from the nail plate, whereas glossy polish presented a greater number of artifacts.2

The Solution

We looked at 3 glitter nail polishes—gold, pink, and silver—that were scanned by OCT to assess the effect of the polish on the resulting image. We determined that glitter particles completely obscured the nail bed and nail plate, regardless of color (Figure 1). Glossy clear polish imparted a distinct film on the top of the nail plate that did not obscure the nail plate or the nail bed (Figure 2).

We conclude that glitter nail polish contains numerous reflective solid particles that interfere with OCT imaging of the nail plate and nail bed. As a result, we recommend removal of nail art to properly assess nail pathology. Because removal may need to be conducted by a nail technician, the treating clinician should inform the patient ahead of time to come to the appointment with bare (ie, unpolished) nails.

Practice Implications

Bringing awareness to the necessity of removing nail art prior to OCT imaging is crucial because many patients partake in its application, and removal may require the involvement of a professional nail technician. If a patient can be made aware that they should remove all nail art in advance, they will be better prepared for an OCT imaging session. Such a protocol increases efficiency, decreases diagnostic delay, and reduces cost associated with multiple office visits.

- Saleah S, Kim P, Seong D, et al. A preliminary study of post-progressive nail-art effects on in vivo nail plate using optical coherence tomography-based intensity profiling assessment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:666. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79497-3

- Monpeurt C, Cinotti E, Hebert M, et al. Thickness and morphology assessment of nail polishes applied on nails by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:156-157. doi:10.1111/srt.12406

- Saleah S, Kim P, Seong D, et al. A preliminary study of post-progressive nail-art effects on in vivo nail plate using optical coherence tomography-based intensity profiling assessment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:666. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79497-3

- Monpeurt C, Cinotti E, Hebert M, et al. Thickness and morphology assessment of nail polishes applied on nails by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:156-157. doi:10.1111/srt.12406

Polyurethane Tubing to Minimize Pain During Nail Injections

Practice Gap

Nail matrix and nail bed injections with triamcinolone acetonide are used to treat trachyonychia and inflammatory nail conditions, including nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus. The procedure should be quick in well-trained hands, with each nail injection taking only seconds to perform. Typically, patients have multiple nails involved, requiring at least 1 injection into the nail matrix or the nail bed (or both) in each nail at each visit. Patients often are anxious when undergoing nail injections; the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular, which can cause notable transient discomfort during the procedure1,2 as well as postoperative pain.3

Nail injections must be repeated every 4 to 6 weeks to sustain clinical benefit and maximize outcomes, which can lead to heightened anxiety and apprehension before and during the visit. Furthermore, pain and anxiety associated with the procedure may deter patients from returning for follow-up injections, which can impact treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Dermatologists should implement strategies to decrease periprocedural anxiety to improve the nail injection experience. In our practice, we routinely incorporate stress-reducing techniques—music, talkesthesia, a sleep mask, cool air, ethyl chloride, and squeezing a stress ball—into the clinical workflow of the procedure. The goal of these techniques is to divert attention away from painful stimuli. Most patients, however, receive injections in both hands, making it impractical to employ some of these techniques, particularly squeezing a stress ball. We employed a unique method involving polyurethane tubing to reduce stress and anxiety during nail procedures.

The Technique

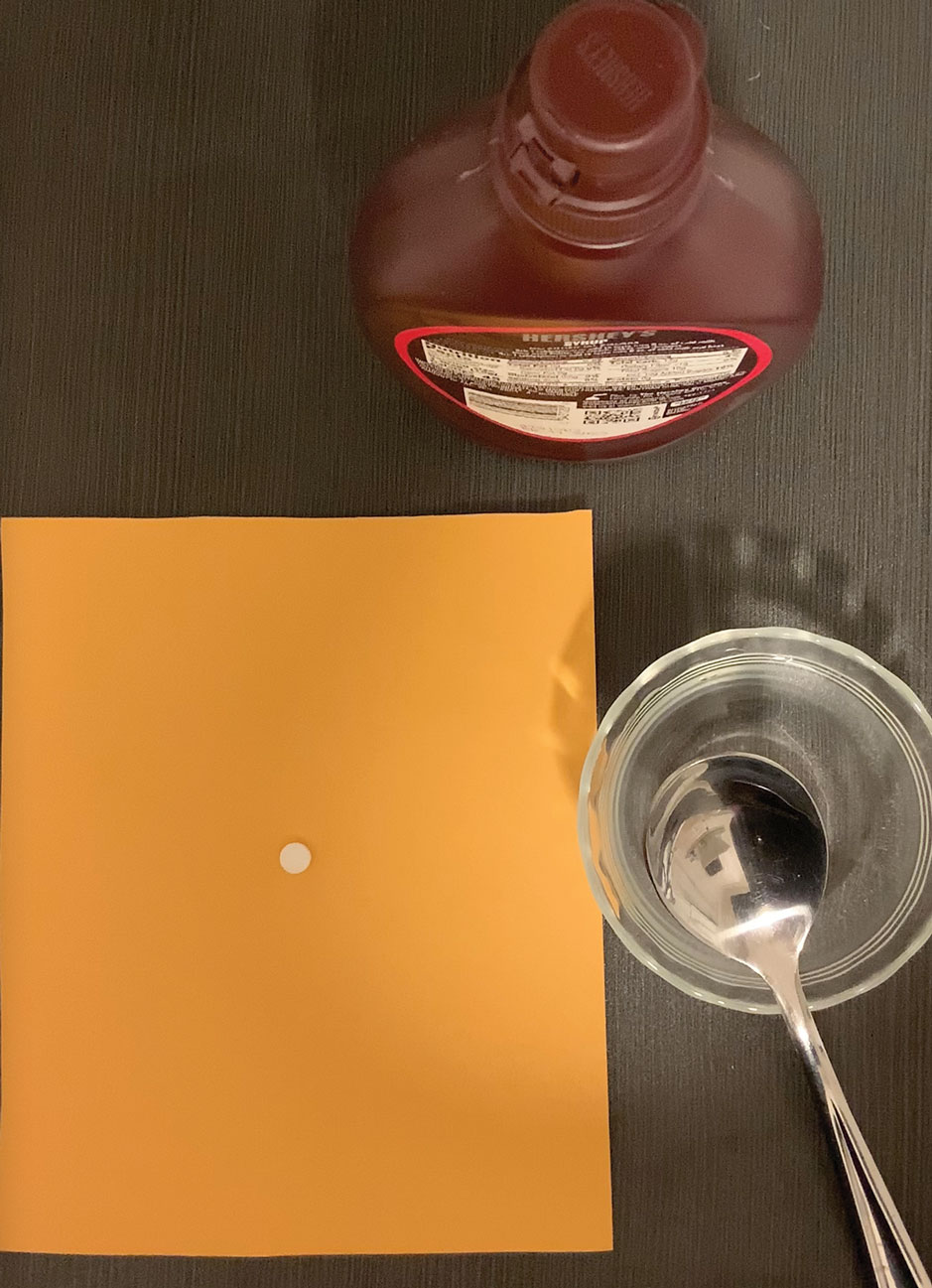

A patient was receiving treatment with intralesional triamcinolone injections to the nail matrix for trachyonychia involving all of the fingernails. He worked as an equipment and facilities manager, giving him access to polyurethane tubing, which is routinely used in the manufacture of some medical devices that require gas or liquid to operate. He found the nail injections to be painful but was motivated to proceed with treatment. He brought in a piece of polyurethane tubing to a subsequent visit to bite on during the injections (Figure) and reported considerable relief of pain.

What you were not taught in United States history class was that this method—clenching an object orally—dates to the era before the Civil War, before appropriate anesthetics and analgesics were developed, when patients and soldiers bit on a bullet or leather strap during surgical procedures.4 Clenching and chewing have been shown to promote relaxation and reduce acute pain and stress.5

Practical Implications

Polyurethane tubing can be purchased in bulk, is inexpensive ($0.30/foot on Amazon), and unlikely to damage teeth due to its flexibility. It can be cut into 6-inch pieces and given to the patient at their first nail injection appointment. The patient can then bring the tubing to subsequent appointments to use as a mastication tool during nail injections.

We instruct the patient to disinfect the dedicated piece of tubing after the initial visit and each subsequent visit by soaking it for 15 minutes in either a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution, antibacterial mouthwash, a solution of baking soda (bicarbonate of soda) and water (1 cup of water to 2 teaspoons of baking soda), or white vinegar. We instruct them to thoroughly dry the disinfected polyurethane tube and store it in a clean, reusable, resealable zipper storage bag between appointments.

In addition to reducing anxiety and pain, this method also distracts the patient and therefore promotes patient and physician safety. Patients are less likely to jump or startle during the injection, thereby reducing the risk of physically interfering with the nail surgeon or making an unanticipated advance into the surgical field.

Although frustrated patients with nail disease may need to “bite the bullet” when they accept treatment with nail injections, lessons from our patient and from United States history offer a safe and cost-effective pain management strategy. Minimizing discomfort and anxiety during the first nail injection is crucial because doing so is likely to promote adherence with follow-up injections and therefore improve clinical outcomes.

Future clinical studies should validate the clinical utility of oral mastication and clenching during nail procedures compared to other perioperative stress- and anxiety-reducing techniques.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0013

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PW, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Albin MS. The use of anesthetics during the Civil War, 1861-1865. Pharm Hist. 2000;42:99-114.

- Tahara Y, Sakurai K, Ando T. Influence of chewing and clenching on salivary cortisol levels as an indicator of stress. J Prosthodont. 2007;16:129-135. doi:10.1111/j.1532-849X.2007.00178.x

Practice Gap

Nail matrix and nail bed injections with triamcinolone acetonide are used to treat trachyonychia and inflammatory nail conditions, including nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus. The procedure should be quick in well-trained hands, with each nail injection taking only seconds to perform. Typically, patients have multiple nails involved, requiring at least 1 injection into the nail matrix or the nail bed (or both) in each nail at each visit. Patients often are anxious when undergoing nail injections; the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular, which can cause notable transient discomfort during the procedure1,2 as well as postoperative pain.3

Nail injections must be repeated every 4 to 6 weeks to sustain clinical benefit and maximize outcomes, which can lead to heightened anxiety and apprehension before and during the visit. Furthermore, pain and anxiety associated with the procedure may deter patients from returning for follow-up injections, which can impact treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Dermatologists should implement strategies to decrease periprocedural anxiety to improve the nail injection experience. In our practice, we routinely incorporate stress-reducing techniques—music, talkesthesia, a sleep mask, cool air, ethyl chloride, and squeezing a stress ball—into the clinical workflow of the procedure. The goal of these techniques is to divert attention away from painful stimuli. Most patients, however, receive injections in both hands, making it impractical to employ some of these techniques, particularly squeezing a stress ball. We employed a unique method involving polyurethane tubing to reduce stress and anxiety during nail procedures.

The Technique

A patient was receiving treatment with intralesional triamcinolone injections to the nail matrix for trachyonychia involving all of the fingernails. He worked as an equipment and facilities manager, giving him access to polyurethane tubing, which is routinely used in the manufacture of some medical devices that require gas or liquid to operate. He found the nail injections to be painful but was motivated to proceed with treatment. He brought in a piece of polyurethane tubing to a subsequent visit to bite on during the injections (Figure) and reported considerable relief of pain.

What you were not taught in United States history class was that this method—clenching an object orally—dates to the era before the Civil War, before appropriate anesthetics and analgesics were developed, when patients and soldiers bit on a bullet or leather strap during surgical procedures.4 Clenching and chewing have been shown to promote relaxation and reduce acute pain and stress.5

Practical Implications

Polyurethane tubing can be purchased in bulk, is inexpensive ($0.30/foot on Amazon), and unlikely to damage teeth due to its flexibility. It can be cut into 6-inch pieces and given to the patient at their first nail injection appointment. The patient can then bring the tubing to subsequent appointments to use as a mastication tool during nail injections.

We instruct the patient to disinfect the dedicated piece of tubing after the initial visit and each subsequent visit by soaking it for 15 minutes in either a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution, antibacterial mouthwash, a solution of baking soda (bicarbonate of soda) and water (1 cup of water to 2 teaspoons of baking soda), or white vinegar. We instruct them to thoroughly dry the disinfected polyurethane tube and store it in a clean, reusable, resealable zipper storage bag between appointments.

In addition to reducing anxiety and pain, this method also distracts the patient and therefore promotes patient and physician safety. Patients are less likely to jump or startle during the injection, thereby reducing the risk of physically interfering with the nail surgeon or making an unanticipated advance into the surgical field.

Although frustrated patients with nail disease may need to “bite the bullet” when they accept treatment with nail injections, lessons from our patient and from United States history offer a safe and cost-effective pain management strategy. Minimizing discomfort and anxiety during the first nail injection is crucial because doing so is likely to promote adherence with follow-up injections and therefore improve clinical outcomes.

Future clinical studies should validate the clinical utility of oral mastication and clenching during nail procedures compared to other perioperative stress- and anxiety-reducing techniques.

Practice Gap

Nail matrix and nail bed injections with triamcinolone acetonide are used to treat trachyonychia and inflammatory nail conditions, including nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus. The procedure should be quick in well-trained hands, with each nail injection taking only seconds to perform. Typically, patients have multiple nails involved, requiring at least 1 injection into the nail matrix or the nail bed (or both) in each nail at each visit. Patients often are anxious when undergoing nail injections; the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular, which can cause notable transient discomfort during the procedure1,2 as well as postoperative pain.3

Nail injections must be repeated every 4 to 6 weeks to sustain clinical benefit and maximize outcomes, which can lead to heightened anxiety and apprehension before and during the visit. Furthermore, pain and anxiety associated with the procedure may deter patients from returning for follow-up injections, which can impact treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Dermatologists should implement strategies to decrease periprocedural anxiety to improve the nail injection experience. In our practice, we routinely incorporate stress-reducing techniques—music, talkesthesia, a sleep mask, cool air, ethyl chloride, and squeezing a stress ball—into the clinical workflow of the procedure. The goal of these techniques is to divert attention away from painful stimuli. Most patients, however, receive injections in both hands, making it impractical to employ some of these techniques, particularly squeezing a stress ball. We employed a unique method involving polyurethane tubing to reduce stress and anxiety during nail procedures.

The Technique