User login

Developing training pathways in advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy in the U.S.

As a gastroenterology and hepatology fellow, choosing a career path was a daunting prospect. Despite the additional specialization, there seemed to be endless career options to consider. Did I want to join an academic, private, or hybrid practice? Should I subspecialize within the field? Was it important to incorporate research or teaching into my practice? What about opportunities to take on administrative or leadership roles?

Fellowship training at a large academic research institution provided me the opportunity to work with expert faculty in inflammatory bowel disease, esophageal disease, motility and functional gastrointestinal disease, pancreaticobiliary disease, and hepatology. I enjoyed seeing patients in each of these subspecialty clinics. But, by the end of my second year of GI fellowship, I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to do professionally.

A career in academic general gastroenterology seemed to be a good fit for my personality and goals. Rather than focusing on research, I chose to position myself as a clinician educator. I knew that having a subspecialty area of expertise would help improve my clinical practice and make me a more attractive candidate to academic centers. To help narrow my choice, I looked at the clinical enterprise at our institution and assessed where the unmet clinical needs were most acute. Simultaneously, I identified potential mentors to support and guide me through the transition from fellow to independent practitioner. I decided to focus on acquiring the skills to care for patients with anorectal diseases and lower-GI motility disorders, as this area met both of my criteria – excellent mentorship and an unmet clinical need. Under the guidance of Dr. Yolanda Scarlett, I spent my 3rd year in clinic learning to interpret anorectal manometry tests, defecograms, and sitz marker studies and treating patients with refractory constipation, fecal incontinence, and anal fissures.

With a plan to develop an expertise in anorectal diseases and low-GI motility disorders, I also wanted to focus on improving my endoscopic skills to graduate as well rounded a clinician as possible. To achieve this goal, I sought out a separate endoscopy mentor, Dr. Ian Grimm, the director of endoscopy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Grimm, a classically trained advanced endoscopist performing endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), had a burgeoning interest in endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and had just returned from a few months in Japan learning to perform endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM).

When I began working with Dr. Grimm, I had not even heard the term third-space endoscopy and knew nothing about ESD or POEM. I spent as much time as possible watching and assisting Dr. Grimm with complex endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) during the first few months of my 3rd year. Soon after my exposure to advanced endoscopic resection, it was clear that I wanted to learn and incorporate this into my clinical practice. I watched Dr. Grimm perform the first POEM at UNC in the fall of 2016 and by that time I was hooked on learning third-space endoscopy. I observed and assisted with as many EMR, ESD, and POEM cases as I could that year. In addition to the hands-on and cognitive training with Dr. Grimm, I attended national meetings and workshops focused on learning third-space endoscopy. In the spring of my 3rd year I was honored to be the first fellow to complete the Olympus master class in ESD – a 2-day hands-on training course sponsored by Olympus. By the end of that year, I was performing complex EMR with minimal assistance and had completed multiple ESDs and POEMs with cognitive supervision only.

After fellowship, I joined the UNC faculty as a general gastroenterologist with expertise in anorectal disease and lower-GI motility disorders. While I was comfortable performing complex EMR, I still needed additional training and supervision before I felt ready to independently perform ESD or POEM. With the gracious support and encouragement of our division chief, I continued third-space endoscopy training with Dr. Grimm during dedicated protected time 2 days each month. Over the ensuing 4 years, I transitioned to fully independent practice performing all types of advanced EMR and third-space endoscopy including complex EMR, ESD, endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection (STER), esophageal POEM, gastric POEM, and Zenker’s POEM.

As one of the first gastroenterologists in the United States to perform third-space endoscopy without any formal training in advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopy, I believe learning advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy is best achieved through a training pathway separate from the conventional advanced endoscopy fellowship focused on teaching EUS and ERCP. Although there are transferable skills learned from EUS and ERCP to the techniques used in third-space endoscopy, there is nothing inherent to performing EUS or ERCP that enables one to learn how to perform an ESD or a POEM.

There is a robust training pathway to teach advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopy, but no formal training pathway exists to teach third-space endoscopy in the United States. Historically, a small number of interested and motivated advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopists sought out opportunities to learn third-space endoscopy after completion of their advanced endoscopy fellowship, in some cases many years after graduation. For these early adopters in the United States, the only training opportunities required travel to Japan or another Eastern country with arrangements made to observe and participate in third-space endoscopy cases with experts there. With increased recognition of the benefits of ESD and POEM over the past 5-10 years in the United States, there has been greater adoption of third-space endoscopy and with it, more training opportunities. Still, there are very few institutions with formalized training programs in advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy in the United States to date.

Proof that this model works

In Eastern countries such as Japan, training endoscopists to perform ESD and POEM has been successfully achieved through an apprenticeship model whereby an expert in third-space endoscopy closely supervises a trainee who gains greater autonomy with increasing experience and skill over time. My personal experience is proof that this model works. But, adopting such a model more widely in the United States may prove difficult. We lack a sufficient number of experienced third-space endoscopy operators and, given the challenges to appropriate reimbursement for third-space endoscopy in the United States, there is understandable resistance to accepting the prolonged training period necessary for technical mastery of this skill.

In part, a long training period is needed because of a relative paucity of appropriate target lesions for ESD and the rarity of achalasia in the United States. While there is consensus among experts regarding the benefits of ESD for resection of early gastric cancer (EGC), relatively few EGCs are found in the United States and indications for ESD outside resection of EGC are less well defined with less clear benefits over more widely performed piecemeal EMR. Despite these challenges, it is critical that we continue to develop dedicated training pathways to teach advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy in the United States. My practice has evolved considerably since completion of fellowship nearly 6 years ago, and I now focus almost exclusively on advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy. Recently, Dr. Grimm and I began an advanced endoscopic resection elective for the general GI fellows at UNC and we are excited to welcome our first advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy fellow to UNC this July.

While there are many possible avenues to expertise in advanced endoscopic resection, few will likely follow the same path that I have taken. Trainees who are interested in pursuing this subspecialty should seek out supportive mentors in a setting where there is already a robust case volume of esophageal motility disorders and endoscopic resections. Success requires the persistent motivation to seek out diverse opportunities for self-study, exposure to experts, data on developments in the field, and hands-on exposure to as many ex-vivo and in-vivo cases as possible.

Dr. Kroch is assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He disclosed having no conflicts of interest.

As a gastroenterology and hepatology fellow, choosing a career path was a daunting prospect. Despite the additional specialization, there seemed to be endless career options to consider. Did I want to join an academic, private, or hybrid practice? Should I subspecialize within the field? Was it important to incorporate research or teaching into my practice? What about opportunities to take on administrative or leadership roles?

Fellowship training at a large academic research institution provided me the opportunity to work with expert faculty in inflammatory bowel disease, esophageal disease, motility and functional gastrointestinal disease, pancreaticobiliary disease, and hepatology. I enjoyed seeing patients in each of these subspecialty clinics. But, by the end of my second year of GI fellowship, I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to do professionally.

A career in academic general gastroenterology seemed to be a good fit for my personality and goals. Rather than focusing on research, I chose to position myself as a clinician educator. I knew that having a subspecialty area of expertise would help improve my clinical practice and make me a more attractive candidate to academic centers. To help narrow my choice, I looked at the clinical enterprise at our institution and assessed where the unmet clinical needs were most acute. Simultaneously, I identified potential mentors to support and guide me through the transition from fellow to independent practitioner. I decided to focus on acquiring the skills to care for patients with anorectal diseases and lower-GI motility disorders, as this area met both of my criteria – excellent mentorship and an unmet clinical need. Under the guidance of Dr. Yolanda Scarlett, I spent my 3rd year in clinic learning to interpret anorectal manometry tests, defecograms, and sitz marker studies and treating patients with refractory constipation, fecal incontinence, and anal fissures.

With a plan to develop an expertise in anorectal diseases and low-GI motility disorders, I also wanted to focus on improving my endoscopic skills to graduate as well rounded a clinician as possible. To achieve this goal, I sought out a separate endoscopy mentor, Dr. Ian Grimm, the director of endoscopy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Grimm, a classically trained advanced endoscopist performing endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), had a burgeoning interest in endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and had just returned from a few months in Japan learning to perform endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM).

When I began working with Dr. Grimm, I had not even heard the term third-space endoscopy and knew nothing about ESD or POEM. I spent as much time as possible watching and assisting Dr. Grimm with complex endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) during the first few months of my 3rd year. Soon after my exposure to advanced endoscopic resection, it was clear that I wanted to learn and incorporate this into my clinical practice. I watched Dr. Grimm perform the first POEM at UNC in the fall of 2016 and by that time I was hooked on learning third-space endoscopy. I observed and assisted with as many EMR, ESD, and POEM cases as I could that year. In addition to the hands-on and cognitive training with Dr. Grimm, I attended national meetings and workshops focused on learning third-space endoscopy. In the spring of my 3rd year I was honored to be the first fellow to complete the Olympus master class in ESD – a 2-day hands-on training course sponsored by Olympus. By the end of that year, I was performing complex EMR with minimal assistance and had completed multiple ESDs and POEMs with cognitive supervision only.

After fellowship, I joined the UNC faculty as a general gastroenterologist with expertise in anorectal disease and lower-GI motility disorders. While I was comfortable performing complex EMR, I still needed additional training and supervision before I felt ready to independently perform ESD or POEM. With the gracious support and encouragement of our division chief, I continued third-space endoscopy training with Dr. Grimm during dedicated protected time 2 days each month. Over the ensuing 4 years, I transitioned to fully independent practice performing all types of advanced EMR and third-space endoscopy including complex EMR, ESD, endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection (STER), esophageal POEM, gastric POEM, and Zenker’s POEM.

As one of the first gastroenterologists in the United States to perform third-space endoscopy without any formal training in advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopy, I believe learning advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy is best achieved through a training pathway separate from the conventional advanced endoscopy fellowship focused on teaching EUS and ERCP. Although there are transferable skills learned from EUS and ERCP to the techniques used in third-space endoscopy, there is nothing inherent to performing EUS or ERCP that enables one to learn how to perform an ESD or a POEM.

There is a robust training pathway to teach advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopy, but no formal training pathway exists to teach third-space endoscopy in the United States. Historically, a small number of interested and motivated advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopists sought out opportunities to learn third-space endoscopy after completion of their advanced endoscopy fellowship, in some cases many years after graduation. For these early adopters in the United States, the only training opportunities required travel to Japan or another Eastern country with arrangements made to observe and participate in third-space endoscopy cases with experts there. With increased recognition of the benefits of ESD and POEM over the past 5-10 years in the United States, there has been greater adoption of third-space endoscopy and with it, more training opportunities. Still, there are very few institutions with formalized training programs in advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy in the United States to date.

Proof that this model works

In Eastern countries such as Japan, training endoscopists to perform ESD and POEM has been successfully achieved through an apprenticeship model whereby an expert in third-space endoscopy closely supervises a trainee who gains greater autonomy with increasing experience and skill over time. My personal experience is proof that this model works. But, adopting such a model more widely in the United States may prove difficult. We lack a sufficient number of experienced third-space endoscopy operators and, given the challenges to appropriate reimbursement for third-space endoscopy in the United States, there is understandable resistance to accepting the prolonged training period necessary for technical mastery of this skill.

In part, a long training period is needed because of a relative paucity of appropriate target lesions for ESD and the rarity of achalasia in the United States. While there is consensus among experts regarding the benefits of ESD for resection of early gastric cancer (EGC), relatively few EGCs are found in the United States and indications for ESD outside resection of EGC are less well defined with less clear benefits over more widely performed piecemeal EMR. Despite these challenges, it is critical that we continue to develop dedicated training pathways to teach advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy in the United States. My practice has evolved considerably since completion of fellowship nearly 6 years ago, and I now focus almost exclusively on advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy. Recently, Dr. Grimm and I began an advanced endoscopic resection elective for the general GI fellows at UNC and we are excited to welcome our first advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy fellow to UNC this July.

While there are many possible avenues to expertise in advanced endoscopic resection, few will likely follow the same path that I have taken. Trainees who are interested in pursuing this subspecialty should seek out supportive mentors in a setting where there is already a robust case volume of esophageal motility disorders and endoscopic resections. Success requires the persistent motivation to seek out diverse opportunities for self-study, exposure to experts, data on developments in the field, and hands-on exposure to as many ex-vivo and in-vivo cases as possible.

Dr. Kroch is assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He disclosed having no conflicts of interest.

As a gastroenterology and hepatology fellow, choosing a career path was a daunting prospect. Despite the additional specialization, there seemed to be endless career options to consider. Did I want to join an academic, private, or hybrid practice? Should I subspecialize within the field? Was it important to incorporate research or teaching into my practice? What about opportunities to take on administrative or leadership roles?

Fellowship training at a large academic research institution provided me the opportunity to work with expert faculty in inflammatory bowel disease, esophageal disease, motility and functional gastrointestinal disease, pancreaticobiliary disease, and hepatology. I enjoyed seeing patients in each of these subspecialty clinics. But, by the end of my second year of GI fellowship, I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to do professionally.

A career in academic general gastroenterology seemed to be a good fit for my personality and goals. Rather than focusing on research, I chose to position myself as a clinician educator. I knew that having a subspecialty area of expertise would help improve my clinical practice and make me a more attractive candidate to academic centers. To help narrow my choice, I looked at the clinical enterprise at our institution and assessed where the unmet clinical needs were most acute. Simultaneously, I identified potential mentors to support and guide me through the transition from fellow to independent practitioner. I decided to focus on acquiring the skills to care for patients with anorectal diseases and lower-GI motility disorders, as this area met both of my criteria – excellent mentorship and an unmet clinical need. Under the guidance of Dr. Yolanda Scarlett, I spent my 3rd year in clinic learning to interpret anorectal manometry tests, defecograms, and sitz marker studies and treating patients with refractory constipation, fecal incontinence, and anal fissures.

With a plan to develop an expertise in anorectal diseases and low-GI motility disorders, I also wanted to focus on improving my endoscopic skills to graduate as well rounded a clinician as possible. To achieve this goal, I sought out a separate endoscopy mentor, Dr. Ian Grimm, the director of endoscopy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Grimm, a classically trained advanced endoscopist performing endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), had a burgeoning interest in endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and had just returned from a few months in Japan learning to perform endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM).

When I began working with Dr. Grimm, I had not even heard the term third-space endoscopy and knew nothing about ESD or POEM. I spent as much time as possible watching and assisting Dr. Grimm with complex endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) during the first few months of my 3rd year. Soon after my exposure to advanced endoscopic resection, it was clear that I wanted to learn and incorporate this into my clinical practice. I watched Dr. Grimm perform the first POEM at UNC in the fall of 2016 and by that time I was hooked on learning third-space endoscopy. I observed and assisted with as many EMR, ESD, and POEM cases as I could that year. In addition to the hands-on and cognitive training with Dr. Grimm, I attended national meetings and workshops focused on learning third-space endoscopy. In the spring of my 3rd year I was honored to be the first fellow to complete the Olympus master class in ESD – a 2-day hands-on training course sponsored by Olympus. By the end of that year, I was performing complex EMR with minimal assistance and had completed multiple ESDs and POEMs with cognitive supervision only.

After fellowship, I joined the UNC faculty as a general gastroenterologist with expertise in anorectal disease and lower-GI motility disorders. While I was comfortable performing complex EMR, I still needed additional training and supervision before I felt ready to independently perform ESD or POEM. With the gracious support and encouragement of our division chief, I continued third-space endoscopy training with Dr. Grimm during dedicated protected time 2 days each month. Over the ensuing 4 years, I transitioned to fully independent practice performing all types of advanced EMR and third-space endoscopy including complex EMR, ESD, endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection (STER), esophageal POEM, gastric POEM, and Zenker’s POEM.

As one of the first gastroenterologists in the United States to perform third-space endoscopy without any formal training in advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopy, I believe learning advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy is best achieved through a training pathway separate from the conventional advanced endoscopy fellowship focused on teaching EUS and ERCP. Although there are transferable skills learned from EUS and ERCP to the techniques used in third-space endoscopy, there is nothing inherent to performing EUS or ERCP that enables one to learn how to perform an ESD or a POEM.

There is a robust training pathway to teach advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopy, but no formal training pathway exists to teach third-space endoscopy in the United States. Historically, a small number of interested and motivated advanced pancreaticobiliary endoscopists sought out opportunities to learn third-space endoscopy after completion of their advanced endoscopy fellowship, in some cases many years after graduation. For these early adopters in the United States, the only training opportunities required travel to Japan or another Eastern country with arrangements made to observe and participate in third-space endoscopy cases with experts there. With increased recognition of the benefits of ESD and POEM over the past 5-10 years in the United States, there has been greater adoption of third-space endoscopy and with it, more training opportunities. Still, there are very few institutions with formalized training programs in advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy in the United States to date.

Proof that this model works

In Eastern countries such as Japan, training endoscopists to perform ESD and POEM has been successfully achieved through an apprenticeship model whereby an expert in third-space endoscopy closely supervises a trainee who gains greater autonomy with increasing experience and skill over time. My personal experience is proof that this model works. But, adopting such a model more widely in the United States may prove difficult. We lack a sufficient number of experienced third-space endoscopy operators and, given the challenges to appropriate reimbursement for third-space endoscopy in the United States, there is understandable resistance to accepting the prolonged training period necessary for technical mastery of this skill.

In part, a long training period is needed because of a relative paucity of appropriate target lesions for ESD and the rarity of achalasia in the United States. While there is consensus among experts regarding the benefits of ESD for resection of early gastric cancer (EGC), relatively few EGCs are found in the United States and indications for ESD outside resection of EGC are less well defined with less clear benefits over more widely performed piecemeal EMR. Despite these challenges, it is critical that we continue to develop dedicated training pathways to teach advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy in the United States. My practice has evolved considerably since completion of fellowship nearly 6 years ago, and I now focus almost exclusively on advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy. Recently, Dr. Grimm and I began an advanced endoscopic resection elective for the general GI fellows at UNC and we are excited to welcome our first advanced endoscopic resection and third-space endoscopy fellow to UNC this July.

While there are many possible avenues to expertise in advanced endoscopic resection, few will likely follow the same path that I have taken. Trainees who are interested in pursuing this subspecialty should seek out supportive mentors in a setting where there is already a robust case volume of esophageal motility disorders and endoscopic resections. Success requires the persistent motivation to seek out diverse opportunities for self-study, exposure to experts, data on developments in the field, and hands-on exposure to as many ex-vivo and in-vivo cases as possible.

Dr. Kroch is assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He disclosed having no conflicts of interest.

Advances in endohepatology

Introduction

Historically, the role of endoscopy in hepatology has been limited to intraluminal and bile duct interventions, primarily for the management of varices and biliary strictures. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has broadened the range of endoscopic treatment by enabling transluminal access to the liver parenchyma and associated vasculature. In this review, we will address recent advances in the expanding field of endohepatology.

Endoscopic-ultrasound guided liver biopsy

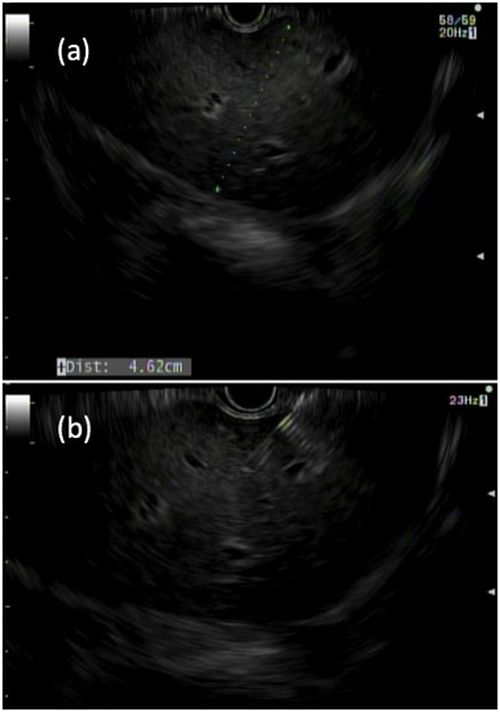

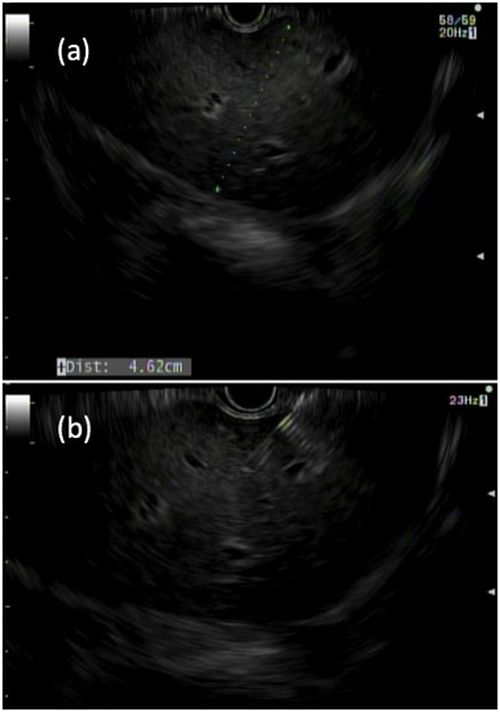

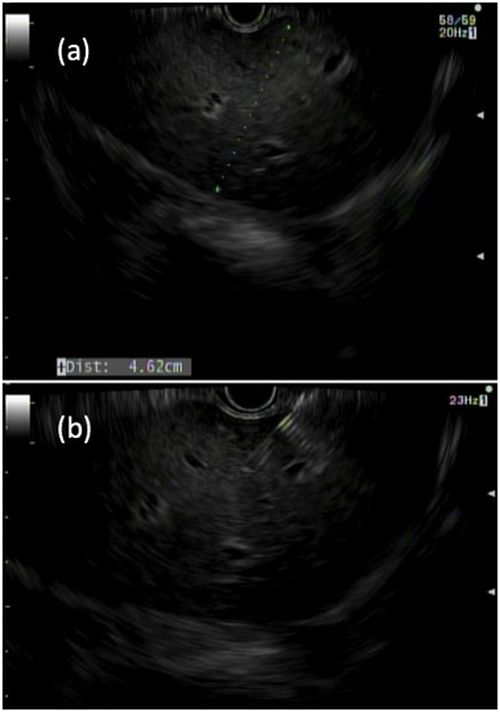

Liver biopsies are a critical tool in the diagnostic evaluation and management of patients with liver disease. Conventional approaches for obtaining liver tissue have been most commonly through the percutaneous or vascular approaches. In 2007, the first EUS-guided liver biopsy (EUS-LB) was described.1 EUS-LB is performed by advancing a line-array echoendoscope to the duodenal bulb to access the right lobe of the liver or proximal stomach to sample the left lobe. Doppler is first used to identify a pathway with few intervening vessels. Then a 19G or 20G needle is passed and slowly withdrawn to capture tissue (Figure 1). Careful evaluation with Doppler ultrasound to evaluate for bleeding is recommended after EUS-LB and if persistent, a small amount of clot may be reinjected as a blood or “Chang” patch akin to technique to control oozing postlumbar puncture.2

While large prospective studies are needed to compare the methods, it appears that specimen adequacy acquired via EUS-LB are comparable to percutaneous and transjugular approaches.3-5 Utilization of specific needle types and suction may optimize samples. Namely, 19G needles may provide better samples than smaller sizes and contemporary fine-needle biopsy needles with Franseen tips are superior to conventional spring-loaded cutting needles and fork tip needles.6-8 The use of dry suction has been shown to increase the yield of tissue, but at the expense of increased bloodiness. Wet suction, which involves the presence of fluid, rather than air, in the needle lumen to lubricate and improve transmission of negative pressure to the needle tip, is the preferred technique for EUS-LB given improvement in the likelihood of intact liver biopsy cores and increased specimen adequacy.9

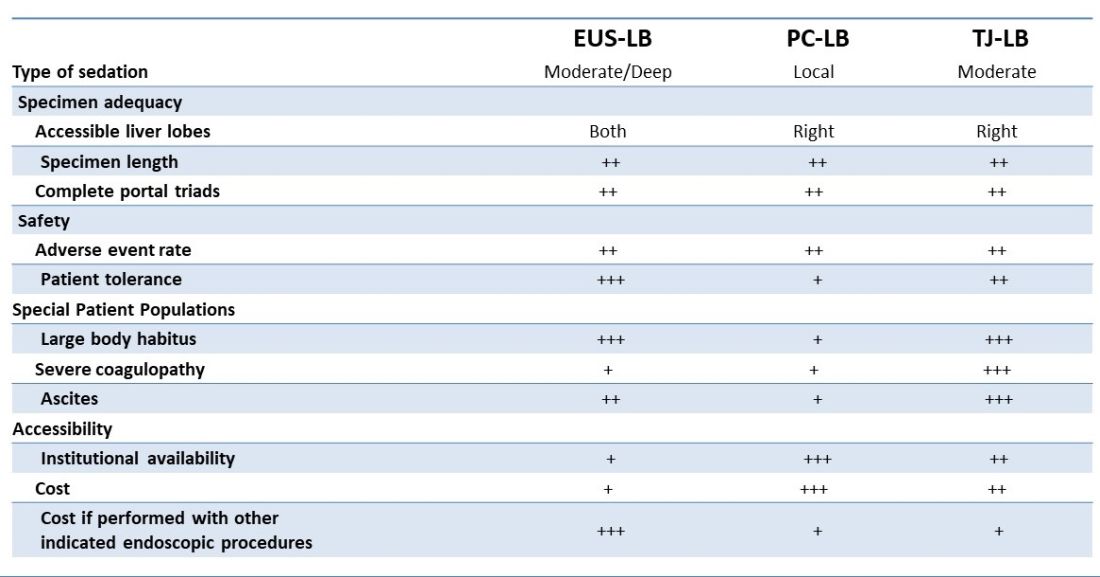

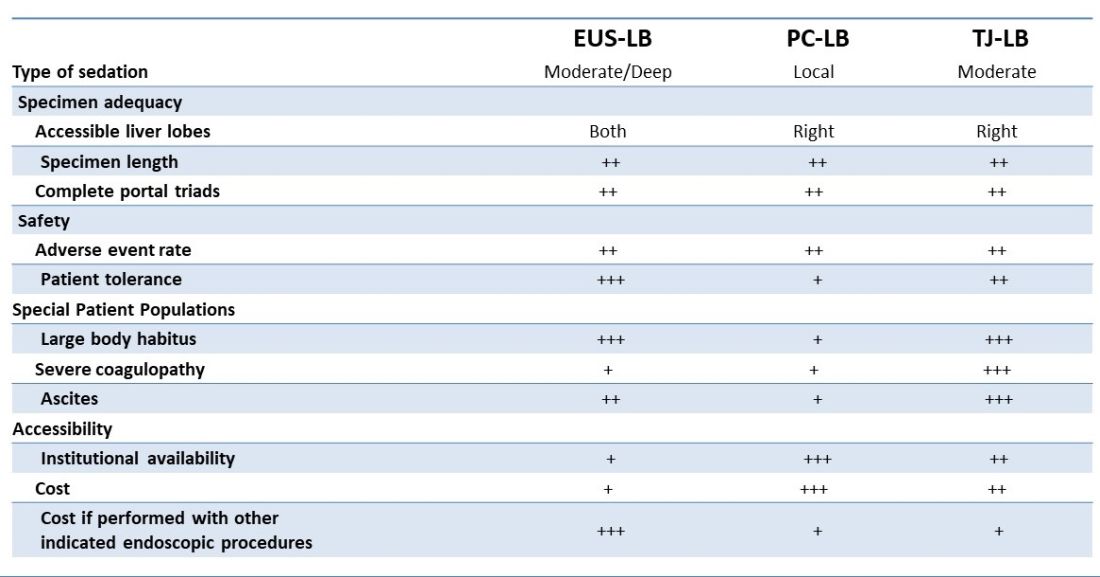

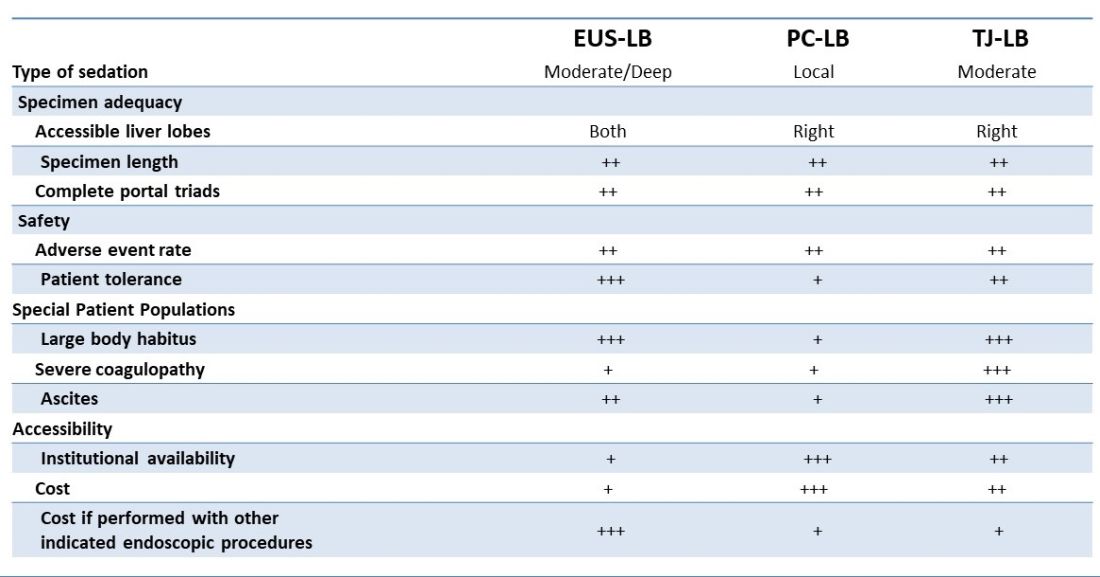

There are several advantages to EUS-LB (Table 1). When compared with percutaneous liver biopsy (PC-LB) and transjugular liver biopsy (TJ-LB), EUS-LB is uniquely able to access both liver lobes in a single setting, which minimizes sampling error.3 EUS-LB may also have an advantage in sampling focal liver lesions given the close proximity of the transducer to the liver.10 Another advantage over PC-LB is that EUS-LB can be performed in patients with a large body habitus. Additionally, EUS-LB is better tolerated than PC-LB, with less postprocedure pain and shorter postprocedure monitoring time.4,5

Rates of adverse events appear to be similar between the three methods. Similar to PC-LB, EUS-LB requires capsular puncture, which can lead to intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Therefore, TJ-LB is preferred in patients with significant coagulopathy. While small ascites is not an absolute contraindication for EUS-LB, large ascites can obscure a safe window from the proximal stomach or duodenum to the liver, and thus TJLB is also preferred in these patients.11 Given its relative novelty and logistic challenges, other disadvantages of EUS-LB include limited provider availability and increased cost, especially compared with PC-LB. The most significant limitation is that it requires moderate or deep sedation, as opposed to local anesthetics. However, if there is another indication for endoscopy (that is, variceal screening), then “one-stop shop” procedures including EUS-LB may be more convenient and cost-effective than traditional methods. Nevertheless, rigorous comparative studies are needed.

EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement

The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than or equal to 10 is a potent predictor of decompensation. There is growing evidence to support the use of beta-blockers to mitigate this risk.12 Therefore, early identification of patients with CSPH has important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. The current gold standard for diagnosing CSPH is with wedged HVPG measurements performed by interventional radiology.

Since its introduction in 2016, EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement (EUS-PPG) has emerged as an alternative to wedged HVPG.13,14 Using a linear echoendoscope, the portal vein is directly accessed with a 25G fine-needle aspiration needle, and three direct measurements are taken using a compact manometer to determine the mean pressure. The hepatic vein, or less commonly the inferior vena cava, pressure is also measured. The direct measurement of portal pressure provides a significant advantage of EUS-PPG over HVPG in patients with presinusoidal and prehepatic portal hypertension. Wedged HVPG, which utilizes the difference between the wedged and free hepatic venous pressure to indirectly estimate the portal venous pressure gradient, yields erroneously low gradients in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.15 An additional advantage of EUS-PPG is that it obviates the need for a central venous line placement, which is associated with thrombosis and, in rare cases, air embolus.16

Observational studies indicate that EUS-PPG has a high degree of consistency with HVPG measurements and a strong correlation between other clinical findings of portal hyper-tension including esophageal varices and thrombocytopenia.13,14 Nevertheless, EUS-PPG is performed under moderate or deep sedation which may impact HVPG measurements.17 In addition, the real-world application of EUS-PPG measurement on clinical care is undefined, but it is the topic of an ongoing clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov – NCT05357599).

EUS-guided interventions of gastric varices

Compared with esophageal varices, current approaches to the treatment and prophylaxis of gastric varices are more controversial.18 The most common approach to bleeding gastric varices in the United States is the placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Nevertheless, in addition to risks associated with central venous line placement, 5%-35% of individuals develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS and ischemic acute liver failure can occur in rare situations.19 Cyanoacrylate (CYA) glue injection is the recommended first-line endoscopic therapy for the treatment of bleeding gastric varices, but use has not been widely adopted in the United States because of a lack of an approved Food and Drug Administration CYA formulation, limited expertise, and risk of serious complications. In particular systemic embolization may result in pulmonary or cerebral infarct.12,18 EUS-guided interventions have been developed to mitigate these safety concerns. EUS-guided coil embolization can be performed, either alone or in combination with CYA injection.20 In the latter approach it acts as a scaffold to prevent migration of the glue bolus. Doppler assessment enables direct visualization of the gastric varix for identification of feeder vessels, more controlled deployment of hemostatic agents, and real-time confirmation of varix obliteration. Fluoroscopy can be used as an adjunct.

EUS-guided interventions in the management of gastric varices appear to be effective and superior to CYA injection under direct endoscopic visualization with improved likelihood of obliteration and lower rebleeding rates, without increase in adverse events.21 Additionally, EUS-guided combination therapy improves technical outcomes and reduces adverse events relative to EUS-guided coil or EUS-guided glue injection therapy alone.21-23 Nevertheless, large-scale prospective trials are needed to determine whether EUS-guided interventions should be considered over TIPS. The role of EUS-guided interventions as primary prophylaxis to prevent bleeding from large gastric varices also requires additional study.24

Future directions

with the goal of optimizing care and increasing efficiency. In addition to new endoscopic procedures to optimize liver biopsy, portal pressure measurement, and gastric variceal treatment, there are a number of emerging technologies including EUS-guided liver elastography, portal venous sampling, liver tumor chemoembolization, and intrahepatic portosystemic shunts.25 However, the practice of endohepatology faces a number of challenges before widespread adoption, including limited provider expertise and institutional availability. Additionally, more robust, multicenter outcomes and cost-effective analyses comparing these novel procedures with traditional approaches are needed to define their clinical impact.

Dr. Bui is a fellow in gastroenterology in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Buxbaum is associate professor of medicine (clinical scholar) in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California. Dr. Buxbaum is a consultant for Cook Medical, Boston Scientific, and Olympus. Dr. Bui has no disclosures.

References

1. Mathew A. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2354-5.

2. Sowa P et al. VideoGIE. 2021;6(11):487-8.

3. Pineda JJ et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):360-5.

4. Ali AH et al. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(2):157-67.

5. Shuja A et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(6):826-30.

6. Schulman AR et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(2):419-26.

7. DeWitt J et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E471-8.

8. Aggarwal SN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1133-8.

9. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(6):919-25.

10. Lee YN et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1161-6.

11. Kalambokis G et al. J Hepatol. 2007;47(2):284-94.

12. de Franchis R et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):959-74.

13. Choi AY et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(7):1373-9.

14. Zhang W et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(3):565-72.

15. Seijo S et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(10):855-60.

16. Vesely TM. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(11):1291-5.

17. Reverter E et al. Liver Int. 2014;34(1):16-25.

18. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1098-107.e1091.

19. Ripamonti R et al. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):165-76.

20. Rengstorff DS and Binmoeller KF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(4):553-8.

21. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):259-67.

22. Robles-Medranda C et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):268-75.

23. McCarty TR et al. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9(1):6-15.

24. Kouanda A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):291-6.

25. Bazarbashi AN et al. 2022;24(1):98-107.

Introduction

Historically, the role of endoscopy in hepatology has been limited to intraluminal and bile duct interventions, primarily for the management of varices and biliary strictures. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has broadened the range of endoscopic treatment by enabling transluminal access to the liver parenchyma and associated vasculature. In this review, we will address recent advances in the expanding field of endohepatology.

Endoscopic-ultrasound guided liver biopsy

Liver biopsies are a critical tool in the diagnostic evaluation and management of patients with liver disease. Conventional approaches for obtaining liver tissue have been most commonly through the percutaneous or vascular approaches. In 2007, the first EUS-guided liver biopsy (EUS-LB) was described.1 EUS-LB is performed by advancing a line-array echoendoscope to the duodenal bulb to access the right lobe of the liver or proximal stomach to sample the left lobe. Doppler is first used to identify a pathway with few intervening vessels. Then a 19G or 20G needle is passed and slowly withdrawn to capture tissue (Figure 1). Careful evaluation with Doppler ultrasound to evaluate for bleeding is recommended after EUS-LB and if persistent, a small amount of clot may be reinjected as a blood or “Chang” patch akin to technique to control oozing postlumbar puncture.2

While large prospective studies are needed to compare the methods, it appears that specimen adequacy acquired via EUS-LB are comparable to percutaneous and transjugular approaches.3-5 Utilization of specific needle types and suction may optimize samples. Namely, 19G needles may provide better samples than smaller sizes and contemporary fine-needle biopsy needles with Franseen tips are superior to conventional spring-loaded cutting needles and fork tip needles.6-8 The use of dry suction has been shown to increase the yield of tissue, but at the expense of increased bloodiness. Wet suction, which involves the presence of fluid, rather than air, in the needle lumen to lubricate and improve transmission of negative pressure to the needle tip, is the preferred technique for EUS-LB given improvement in the likelihood of intact liver biopsy cores and increased specimen adequacy.9

There are several advantages to EUS-LB (Table 1). When compared with percutaneous liver biopsy (PC-LB) and transjugular liver biopsy (TJ-LB), EUS-LB is uniquely able to access both liver lobes in a single setting, which minimizes sampling error.3 EUS-LB may also have an advantage in sampling focal liver lesions given the close proximity of the transducer to the liver.10 Another advantage over PC-LB is that EUS-LB can be performed in patients with a large body habitus. Additionally, EUS-LB is better tolerated than PC-LB, with less postprocedure pain and shorter postprocedure monitoring time.4,5

Rates of adverse events appear to be similar between the three methods. Similar to PC-LB, EUS-LB requires capsular puncture, which can lead to intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Therefore, TJ-LB is preferred in patients with significant coagulopathy. While small ascites is not an absolute contraindication for EUS-LB, large ascites can obscure a safe window from the proximal stomach or duodenum to the liver, and thus TJLB is also preferred in these patients.11 Given its relative novelty and logistic challenges, other disadvantages of EUS-LB include limited provider availability and increased cost, especially compared with PC-LB. The most significant limitation is that it requires moderate or deep sedation, as opposed to local anesthetics. However, if there is another indication for endoscopy (that is, variceal screening), then “one-stop shop” procedures including EUS-LB may be more convenient and cost-effective than traditional methods. Nevertheless, rigorous comparative studies are needed.

EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement

The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than or equal to 10 is a potent predictor of decompensation. There is growing evidence to support the use of beta-blockers to mitigate this risk.12 Therefore, early identification of patients with CSPH has important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. The current gold standard for diagnosing CSPH is with wedged HVPG measurements performed by interventional radiology.

Since its introduction in 2016, EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement (EUS-PPG) has emerged as an alternative to wedged HVPG.13,14 Using a linear echoendoscope, the portal vein is directly accessed with a 25G fine-needle aspiration needle, and three direct measurements are taken using a compact manometer to determine the mean pressure. The hepatic vein, or less commonly the inferior vena cava, pressure is also measured. The direct measurement of portal pressure provides a significant advantage of EUS-PPG over HVPG in patients with presinusoidal and prehepatic portal hypertension. Wedged HVPG, which utilizes the difference between the wedged and free hepatic venous pressure to indirectly estimate the portal venous pressure gradient, yields erroneously low gradients in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.15 An additional advantage of EUS-PPG is that it obviates the need for a central venous line placement, which is associated with thrombosis and, in rare cases, air embolus.16

Observational studies indicate that EUS-PPG has a high degree of consistency with HVPG measurements and a strong correlation between other clinical findings of portal hyper-tension including esophageal varices and thrombocytopenia.13,14 Nevertheless, EUS-PPG is performed under moderate or deep sedation which may impact HVPG measurements.17 In addition, the real-world application of EUS-PPG measurement on clinical care is undefined, but it is the topic of an ongoing clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov – NCT05357599).

EUS-guided interventions of gastric varices

Compared with esophageal varices, current approaches to the treatment and prophylaxis of gastric varices are more controversial.18 The most common approach to bleeding gastric varices in the United States is the placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Nevertheless, in addition to risks associated with central venous line placement, 5%-35% of individuals develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS and ischemic acute liver failure can occur in rare situations.19 Cyanoacrylate (CYA) glue injection is the recommended first-line endoscopic therapy for the treatment of bleeding gastric varices, but use has not been widely adopted in the United States because of a lack of an approved Food and Drug Administration CYA formulation, limited expertise, and risk of serious complications. In particular systemic embolization may result in pulmonary or cerebral infarct.12,18 EUS-guided interventions have been developed to mitigate these safety concerns. EUS-guided coil embolization can be performed, either alone or in combination with CYA injection.20 In the latter approach it acts as a scaffold to prevent migration of the glue bolus. Doppler assessment enables direct visualization of the gastric varix for identification of feeder vessels, more controlled deployment of hemostatic agents, and real-time confirmation of varix obliteration. Fluoroscopy can be used as an adjunct.

EUS-guided interventions in the management of gastric varices appear to be effective and superior to CYA injection under direct endoscopic visualization with improved likelihood of obliteration and lower rebleeding rates, without increase in adverse events.21 Additionally, EUS-guided combination therapy improves technical outcomes and reduces adverse events relative to EUS-guided coil or EUS-guided glue injection therapy alone.21-23 Nevertheless, large-scale prospective trials are needed to determine whether EUS-guided interventions should be considered over TIPS. The role of EUS-guided interventions as primary prophylaxis to prevent bleeding from large gastric varices also requires additional study.24

Future directions

with the goal of optimizing care and increasing efficiency. In addition to new endoscopic procedures to optimize liver biopsy, portal pressure measurement, and gastric variceal treatment, there are a number of emerging technologies including EUS-guided liver elastography, portal venous sampling, liver tumor chemoembolization, and intrahepatic portosystemic shunts.25 However, the practice of endohepatology faces a number of challenges before widespread adoption, including limited provider expertise and institutional availability. Additionally, more robust, multicenter outcomes and cost-effective analyses comparing these novel procedures with traditional approaches are needed to define their clinical impact.

Dr. Bui is a fellow in gastroenterology in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Buxbaum is associate professor of medicine (clinical scholar) in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California. Dr. Buxbaum is a consultant for Cook Medical, Boston Scientific, and Olympus. Dr. Bui has no disclosures.

References

1. Mathew A. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2354-5.

2. Sowa P et al. VideoGIE. 2021;6(11):487-8.

3. Pineda JJ et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):360-5.

4. Ali AH et al. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(2):157-67.

5. Shuja A et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(6):826-30.

6. Schulman AR et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(2):419-26.

7. DeWitt J et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E471-8.

8. Aggarwal SN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1133-8.

9. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(6):919-25.

10. Lee YN et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1161-6.

11. Kalambokis G et al. J Hepatol. 2007;47(2):284-94.

12. de Franchis R et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):959-74.

13. Choi AY et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(7):1373-9.

14. Zhang W et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(3):565-72.

15. Seijo S et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(10):855-60.

16. Vesely TM. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(11):1291-5.

17. Reverter E et al. Liver Int. 2014;34(1):16-25.

18. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1098-107.e1091.

19. Ripamonti R et al. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):165-76.

20. Rengstorff DS and Binmoeller KF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(4):553-8.

21. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):259-67.

22. Robles-Medranda C et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):268-75.

23. McCarty TR et al. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9(1):6-15.

24. Kouanda A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):291-6.

25. Bazarbashi AN et al. 2022;24(1):98-107.

Introduction

Historically, the role of endoscopy in hepatology has been limited to intraluminal and bile duct interventions, primarily for the management of varices and biliary strictures. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has broadened the range of endoscopic treatment by enabling transluminal access to the liver parenchyma and associated vasculature. In this review, we will address recent advances in the expanding field of endohepatology.

Endoscopic-ultrasound guided liver biopsy

Liver biopsies are a critical tool in the diagnostic evaluation and management of patients with liver disease. Conventional approaches for obtaining liver tissue have been most commonly through the percutaneous or vascular approaches. In 2007, the first EUS-guided liver biopsy (EUS-LB) was described.1 EUS-LB is performed by advancing a line-array echoendoscope to the duodenal bulb to access the right lobe of the liver or proximal stomach to sample the left lobe. Doppler is first used to identify a pathway with few intervening vessels. Then a 19G or 20G needle is passed and slowly withdrawn to capture tissue (Figure 1). Careful evaluation with Doppler ultrasound to evaluate for bleeding is recommended after EUS-LB and if persistent, a small amount of clot may be reinjected as a blood or “Chang” patch akin to technique to control oozing postlumbar puncture.2

While large prospective studies are needed to compare the methods, it appears that specimen adequacy acquired via EUS-LB are comparable to percutaneous and transjugular approaches.3-5 Utilization of specific needle types and suction may optimize samples. Namely, 19G needles may provide better samples than smaller sizes and contemporary fine-needle biopsy needles with Franseen tips are superior to conventional spring-loaded cutting needles and fork tip needles.6-8 The use of dry suction has been shown to increase the yield of tissue, but at the expense of increased bloodiness. Wet suction, which involves the presence of fluid, rather than air, in the needle lumen to lubricate and improve transmission of negative pressure to the needle tip, is the preferred technique for EUS-LB given improvement in the likelihood of intact liver biopsy cores and increased specimen adequacy.9

There are several advantages to EUS-LB (Table 1). When compared with percutaneous liver biopsy (PC-LB) and transjugular liver biopsy (TJ-LB), EUS-LB is uniquely able to access both liver lobes in a single setting, which minimizes sampling error.3 EUS-LB may also have an advantage in sampling focal liver lesions given the close proximity of the transducer to the liver.10 Another advantage over PC-LB is that EUS-LB can be performed in patients with a large body habitus. Additionally, EUS-LB is better tolerated than PC-LB, with less postprocedure pain and shorter postprocedure monitoring time.4,5

Rates of adverse events appear to be similar between the three methods. Similar to PC-LB, EUS-LB requires capsular puncture, which can lead to intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Therefore, TJ-LB is preferred in patients with significant coagulopathy. While small ascites is not an absolute contraindication for EUS-LB, large ascites can obscure a safe window from the proximal stomach or duodenum to the liver, and thus TJLB is also preferred in these patients.11 Given its relative novelty and logistic challenges, other disadvantages of EUS-LB include limited provider availability and increased cost, especially compared with PC-LB. The most significant limitation is that it requires moderate or deep sedation, as opposed to local anesthetics. However, if there is another indication for endoscopy (that is, variceal screening), then “one-stop shop” procedures including EUS-LB may be more convenient and cost-effective than traditional methods. Nevertheless, rigorous comparative studies are needed.

EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement

The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), defined as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than or equal to 10 is a potent predictor of decompensation. There is growing evidence to support the use of beta-blockers to mitigate this risk.12 Therefore, early identification of patients with CSPH has important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. The current gold standard for diagnosing CSPH is with wedged HVPG measurements performed by interventional radiology.

Since its introduction in 2016, EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement (EUS-PPG) has emerged as an alternative to wedged HVPG.13,14 Using a linear echoendoscope, the portal vein is directly accessed with a 25G fine-needle aspiration needle, and three direct measurements are taken using a compact manometer to determine the mean pressure. The hepatic vein, or less commonly the inferior vena cava, pressure is also measured. The direct measurement of portal pressure provides a significant advantage of EUS-PPG over HVPG in patients with presinusoidal and prehepatic portal hypertension. Wedged HVPG, which utilizes the difference between the wedged and free hepatic venous pressure to indirectly estimate the portal venous pressure gradient, yields erroneously low gradients in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.15 An additional advantage of EUS-PPG is that it obviates the need for a central venous line placement, which is associated with thrombosis and, in rare cases, air embolus.16

Observational studies indicate that EUS-PPG has a high degree of consistency with HVPG measurements and a strong correlation between other clinical findings of portal hyper-tension including esophageal varices and thrombocytopenia.13,14 Nevertheless, EUS-PPG is performed under moderate or deep sedation which may impact HVPG measurements.17 In addition, the real-world application of EUS-PPG measurement on clinical care is undefined, but it is the topic of an ongoing clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov – NCT05357599).

EUS-guided interventions of gastric varices

Compared with esophageal varices, current approaches to the treatment and prophylaxis of gastric varices are more controversial.18 The most common approach to bleeding gastric varices in the United States is the placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Nevertheless, in addition to risks associated with central venous line placement, 5%-35% of individuals develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS and ischemic acute liver failure can occur in rare situations.19 Cyanoacrylate (CYA) glue injection is the recommended first-line endoscopic therapy for the treatment of bleeding gastric varices, but use has not been widely adopted in the United States because of a lack of an approved Food and Drug Administration CYA formulation, limited expertise, and risk of serious complications. In particular systemic embolization may result in pulmonary or cerebral infarct.12,18 EUS-guided interventions have been developed to mitigate these safety concerns. EUS-guided coil embolization can be performed, either alone or in combination with CYA injection.20 In the latter approach it acts as a scaffold to prevent migration of the glue bolus. Doppler assessment enables direct visualization of the gastric varix for identification of feeder vessels, more controlled deployment of hemostatic agents, and real-time confirmation of varix obliteration. Fluoroscopy can be used as an adjunct.

EUS-guided interventions in the management of gastric varices appear to be effective and superior to CYA injection under direct endoscopic visualization with improved likelihood of obliteration and lower rebleeding rates, without increase in adverse events.21 Additionally, EUS-guided combination therapy improves technical outcomes and reduces adverse events relative to EUS-guided coil or EUS-guided glue injection therapy alone.21-23 Nevertheless, large-scale prospective trials are needed to determine whether EUS-guided interventions should be considered over TIPS. The role of EUS-guided interventions as primary prophylaxis to prevent bleeding from large gastric varices also requires additional study.24

Future directions

with the goal of optimizing care and increasing efficiency. In addition to new endoscopic procedures to optimize liver biopsy, portal pressure measurement, and gastric variceal treatment, there are a number of emerging technologies including EUS-guided liver elastography, portal venous sampling, liver tumor chemoembolization, and intrahepatic portosystemic shunts.25 However, the practice of endohepatology faces a number of challenges before widespread adoption, including limited provider expertise and institutional availability. Additionally, more robust, multicenter outcomes and cost-effective analyses comparing these novel procedures with traditional approaches are needed to define their clinical impact.

Dr. Bui is a fellow in gastroenterology in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Buxbaum is associate professor of medicine (clinical scholar) in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Southern California. Dr. Buxbaum is a consultant for Cook Medical, Boston Scientific, and Olympus. Dr. Bui has no disclosures.

References

1. Mathew A. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2354-5.

2. Sowa P et al. VideoGIE. 2021;6(11):487-8.

3. Pineda JJ et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):360-5.

4. Ali AH et al. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(2):157-67.

5. Shuja A et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(6):826-30.

6. Schulman AR et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(2):419-26.

7. DeWitt J et al. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(5):E471-8.

8. Aggarwal SN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1133-8.

9. Mok SRS et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(6):919-25.

10. Lee YN et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1161-6.

11. Kalambokis G et al. J Hepatol. 2007;47(2):284-94.

12. de Franchis R et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):959-74.

13. Choi AY et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(7):1373-9.

14. Zhang W et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(3):565-72.

15. Seijo S et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(10):855-60.

16. Vesely TM. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(11):1291-5.

17. Reverter E et al. Liver Int. 2014;34(1):16-25.

18. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1098-107.e1091.

19. Ripamonti R et al. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):165-76.

20. Rengstorff DS and Binmoeller KF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(4):553-8.

21. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):259-67.

22. Robles-Medranda C et al. Endoscopy. 2020;52(4):268-75.

23. McCarty TR et al. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9(1):6-15.

24. Kouanda A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(2):291-6.

25. Bazarbashi AN et al. 2022;24(1):98-107.

I selected a GI career path aligned with my goals

In this video, Dr. David Ramsay of Digestive Health Specialists in Winston Salem, N.C., discusses the different career paths available to fellows and early-career physicians, and why he chose to become a private practice gastroenterologist. Dr. Ramsay shares his insights into different private practice models and what physicians should consider when beginning their careers, as well as what questions to ask when trying to determine if an organization will be a good fit for their future career plans. He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

In this video, Dr. David Ramsay of Digestive Health Specialists in Winston Salem, N.C., discusses the different career paths available to fellows and early-career physicians, and why he chose to become a private practice gastroenterologist. Dr. Ramsay shares his insights into different private practice models and what physicians should consider when beginning their careers, as well as what questions to ask when trying to determine if an organization will be a good fit for their future career plans. He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

In this video, Dr. David Ramsay of Digestive Health Specialists in Winston Salem, N.C., discusses the different career paths available to fellows and early-career physicians, and why he chose to become a private practice gastroenterologist. Dr. Ramsay shares his insights into different private practice models and what physicians should consider when beginning their careers, as well as what questions to ask when trying to determine if an organization will be a good fit for their future career plans. He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

Increase in message volume begs the question: ‘Should we be compensated for our time?’

The American Gastroenterological Association and other gastrointestinal-specific organizations have excellent resources available to members that focus on optimizing reimbursement in your clinical and endoscopic practice.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency (PHE), many previously noncovered services were now covered under rules of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. During the pandemic, patient portal messages increased by 157%, meaning more work for health care teams, negatively impacting physician satisfaction, and increasing burnout.1 Medical burnout has been associated with increased time spent on electronic health records, with some subspeciality gastroenterology (GI) groups having a high EHR burden, according to a recently published article in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.2

This topic is a timely discussion as several large health systems have implemented processes to bill for non–face-to-face services (termed “asynchronous care”), some of which have not been well received in the lay media. It is important to note that despite these implementations, studies have shown only 1% of all incoming portal messages would meet criteria to be submitted for reimbursement. This impact might be slightly higher in chronic care management practices.

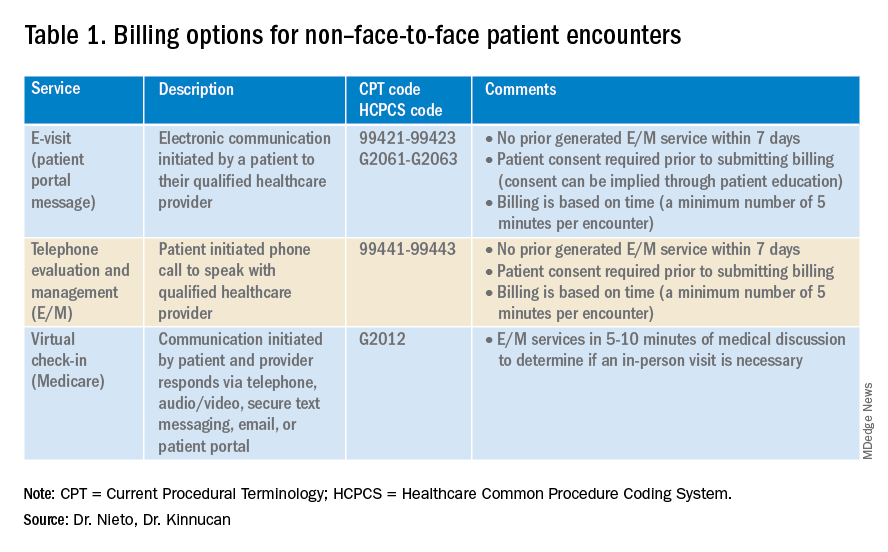

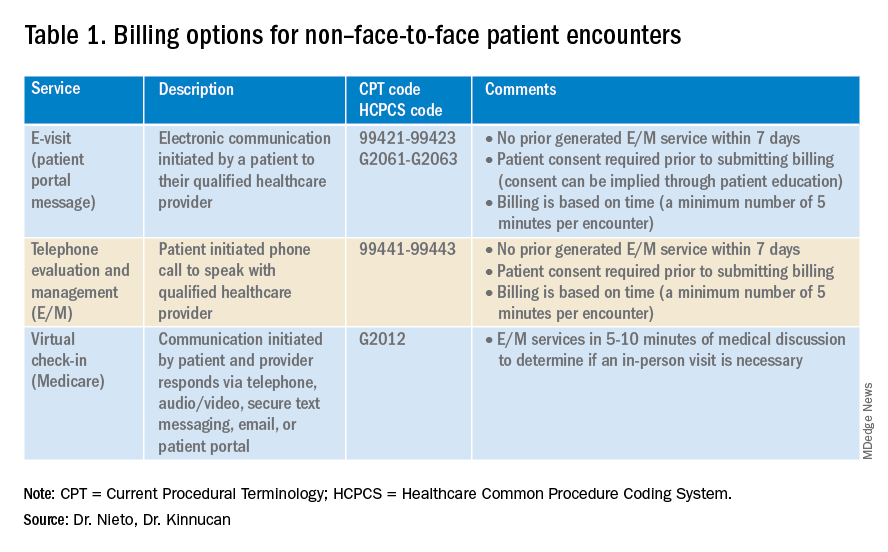

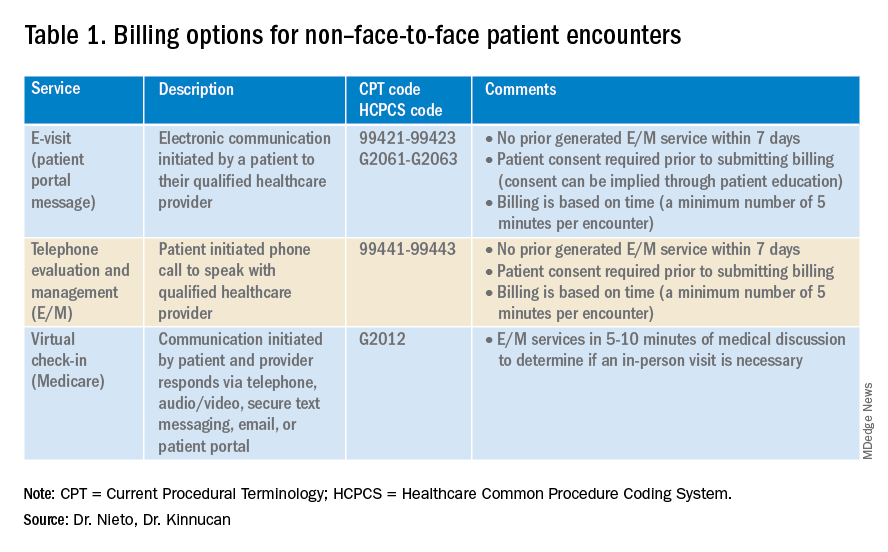

Providers and practices have several options when considering billing for non–face-to-face encounters, which we outline in Table 1.3

The focus of this article will be to review the more common non–face-to-face evaluation and management services, such as telephone E/M (patient phone call) and e-visits (patient portal messages) as these have recently generated the most interest and discussion amongst health care providers.

Telemedicine after COVID-19 pandemic

During the beginning of the pandemic, a web-based survey study found that almost all providers in GI practices implemented some form of telemedicine to continue to provide care for patients, compared to 32% prior to the pandemic.4,5 The high demand and essential requirement for telehealth evaluation facilitated its reimbursement, eliminating the primary barrier to previous use.6

One of the new covered benefits by CMS was asynchronous telehealth care.7 The PHE ended in May 2023, and since then a qualified health care provider (QHCP) does not have the full flexibility to deliver telemedicine services across state lines. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has considered some telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 PHE and many of those will be extended, at least through 2024.8 As during the pandemic, where the U.S. national payer network (CMS, state Medicaid, and private payers) and state health agencies assisted to ensure patients get the care they need by authorizing providers to be compensated for non–face-to-face services, we believe this service will continue to be part of our clinical practice.

We recommend you stay informed about local and federal laws, regulations, and alternatives for reimbursement as they may be modified at the beginning of a new calendar year. Remember, you can always talk with your revenue cycle team to clarify any query.

Telephone evaluation and management services

The patient requests to speak with you.

Telephone evaluation and management services became more widely used after the pandemic and were recognized by CMS as a covered medical service under PHE. As outlined in Table 1, there are associated codes with this service and it can only apply to an established patient in your practice. The cumulative time spent over a 7-day period without generating an immediate follow-up visit could qualify for this CPT code. However, for a patient with a high-complexity diagnosis and/or decisions being made about care, it might be better to consider a virtual office visit as this would value the complex care at a higher level than the time spent during the telephone E/M encounter.

A common question comes up: Can my nurse or support team bill for telephone care? No, only QHCP can, which means physicians and advanced practice providers can bill for this E/M service, and it does not include time spent by other members of clinical staff in patient care. However, there are CPT codes for chronic care management, which is not covered in this article.

Virtual evaluation and management services

You respond to a patient-initiated portal message.

Patient portal messages increased exponentially during the pandemic with 2.5 more minutes spent per message, resulting in more EHR work by practitioners, compared with prior to the pandemic. One study showed an immediate postpandemic increase in EHR patient-initiated messages with no return to prepandemic baseline.1

Although studies evaluating postpandemic telemedicine services are needed, we believe that this trend will continue, and for this reason, it is important to create sustainable workflows to continue to provide this patient driven avenue of care.9

E-visits are asynchronous patient or guardian portal messages that require a minimum of 5 minutes to provide medical decision-making without prior E/M services in the last 7 days. To obtain reimbursement for this service, it cannot be initiated by the provider, and patient consent must be obtained. Documentation should include this information and the time spent in the encounter. The associated CPT codes with this e-service are outlined in Table 1.

A common question is, “Are there additional codes I should use if a portal message E/M visit lasts more than 30 minutes?” No. If an e-visit lasts more than 30 minutes, the QHCP should bill the CPT code 99423. However, we would advise that, if this care requires more than 30 minutes, then either virtual or face-to-face E/M be considered for the optimal reimbursement for provider time spent. Another common question is around consent for services, and we advise providers to review this requirement with their compliance colleagues as each institution has different policies.

Virtual check-in

Medicare also covers brief communication technology–based services also known as virtual check-ins, where patients can communicate with their provider after having established care. During this brief conversation that can be via telephone, audio/video, secure text messaging, email, or patient portal, providers will determine if an in-person visit is necessary. CMS has designed G codes for these virtual check-ins that are from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Two codes are available for this E/M service: G2012, which is outlined in Table 1, and G2010, which covers the evaluation of images and/or recorded videos. In order to be reimbursed for a G2010 code, providers need at least a 5-minute response to make a clinical determination or give the patient a medical impression.

Patient satisfaction, physician well-being and quality of care outcomes

Large health care systems like Kaiser Permanente implemented secure message patient-physician communication (the patient portal) even before the pandemic, showing promising results in 2010 with reduction in office visits, improvement in measurable quality outcomes, and high level of patient satisfaction.10 Post pandemic, several large health care centers opted to announce the billing implementation for patient-initiated portal messages.11 A focus was placed on educating their patients about when a message will and will not be billed. Using this type of strategy can help to improve patient awareness about potential billing without affecting patient satisfaction and care outcomes. Studies have shown the EHR has contributed to physician burnout and some physicians reducing their clinical time or leaving medicine; a reduction in messaging might have a positive impact on physician well-being.

The challenge is that medical billing is not routinely included as a curriculum topic in many residency and fellowship programs; however, trainees are part of E/M services and have limited knowledge of billing processes. Unfortunately, at this time, trainees cannot submit for reimbursement for asynchronous care as described above. We hope that this brief article will help junior gastroenterologists optimize their outpatient billing practices.

Dr. Nieto is an internal medicine chief resident with WellStar Cobb Medical Center, Austell, Ga. Dr. Kinnucan is a gastroenterologist with Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose for this article. The authors certify that no financial and grant support has been received for this article.

References

1. Holmgren AJ et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021 Dec 9. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab268.

2. Bali AS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Apr 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002254.

3. AAFP. Family Physician. “Coding Scenario: Coding for Virtual-Digital Visits”

4. Keihanian T. et al. Telehealth Utilization in Gastroenterology Clinics Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Clinical Practice and Gastroenterology Training. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jun 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.040.

5. Lewin S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Oct 21. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa140.

6. Perisetti A and H Goyal. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Mar 3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-06874-x.

7. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Medicaid and Medicare billing for asynchronous telehealth. Updated: 2022 May 4.

8. Telehealth.HHS.gov. Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency. Last updated: 2023 Jan 23.

9. Fox B and Sizemore JO. Telehealth: Fad or the future. Epic Health Research Network. 2020 Aug 18.

10. Baer D. Patient-physician e-mail communication: the kaiser permanente experience. J Oncol Pract. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000323.

11. Myclevelandclinic.org. MyChart Messaging.

12. Sinsky CA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Aug 29. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07766-0.

The American Gastroenterological Association and other gastrointestinal-specific organizations have excellent resources available to members that focus on optimizing reimbursement in your clinical and endoscopic practice.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency (PHE), many previously noncovered services were now covered under rules of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. During the pandemic, patient portal messages increased by 157%, meaning more work for health care teams, negatively impacting physician satisfaction, and increasing burnout.1 Medical burnout has been associated with increased time spent on electronic health records, with some subspeciality gastroenterology (GI) groups having a high EHR burden, according to a recently published article in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.2

This topic is a timely discussion as several large health systems have implemented processes to bill for non–face-to-face services (termed “asynchronous care”), some of which have not been well received in the lay media. It is important to note that despite these implementations, studies have shown only 1% of all incoming portal messages would meet criteria to be submitted for reimbursement. This impact might be slightly higher in chronic care management practices.

Providers and practices have several options when considering billing for non–face-to-face encounters, which we outline in Table 1.3

The focus of this article will be to review the more common non–face-to-face evaluation and management services, such as telephone E/M (patient phone call) and e-visits (patient portal messages) as these have recently generated the most interest and discussion amongst health care providers.

Telemedicine after COVID-19 pandemic

During the beginning of the pandemic, a web-based survey study found that almost all providers in GI practices implemented some form of telemedicine to continue to provide care for patients, compared to 32% prior to the pandemic.4,5 The high demand and essential requirement for telehealth evaluation facilitated its reimbursement, eliminating the primary barrier to previous use.6

One of the new covered benefits by CMS was asynchronous telehealth care.7 The PHE ended in May 2023, and since then a qualified health care provider (QHCP) does not have the full flexibility to deliver telemedicine services across state lines. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has considered some telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 PHE and many of those will be extended, at least through 2024.8 As during the pandemic, where the U.S. national payer network (CMS, state Medicaid, and private payers) and state health agencies assisted to ensure patients get the care they need by authorizing providers to be compensated for non–face-to-face services, we believe this service will continue to be part of our clinical practice.

We recommend you stay informed about local and federal laws, regulations, and alternatives for reimbursement as they may be modified at the beginning of a new calendar year. Remember, you can always talk with your revenue cycle team to clarify any query.

Telephone evaluation and management services

The patient requests to speak with you.

Telephone evaluation and management services became more widely used after the pandemic and were recognized by CMS as a covered medical service under PHE. As outlined in Table 1, there are associated codes with this service and it can only apply to an established patient in your practice. The cumulative time spent over a 7-day period without generating an immediate follow-up visit could qualify for this CPT code. However, for a patient with a high-complexity diagnosis and/or decisions being made about care, it might be better to consider a virtual office visit as this would value the complex care at a higher level than the time spent during the telephone E/M encounter.

A common question comes up: Can my nurse or support team bill for telephone care? No, only QHCP can, which means physicians and advanced practice providers can bill for this E/M service, and it does not include time spent by other members of clinical staff in patient care. However, there are CPT codes for chronic care management, which is not covered in this article.

Virtual evaluation and management services

You respond to a patient-initiated portal message.

Patient portal messages increased exponentially during the pandemic with 2.5 more minutes spent per message, resulting in more EHR work by practitioners, compared with prior to the pandemic. One study showed an immediate postpandemic increase in EHR patient-initiated messages with no return to prepandemic baseline.1

Although studies evaluating postpandemic telemedicine services are needed, we believe that this trend will continue, and for this reason, it is important to create sustainable workflows to continue to provide this patient driven avenue of care.9

E-visits are asynchronous patient or guardian portal messages that require a minimum of 5 minutes to provide medical decision-making without prior E/M services in the last 7 days. To obtain reimbursement for this service, it cannot be initiated by the provider, and patient consent must be obtained. Documentation should include this information and the time spent in the encounter. The associated CPT codes with this e-service are outlined in Table 1.

A common question is, “Are there additional codes I should use if a portal message E/M visit lasts more than 30 minutes?” No. If an e-visit lasts more than 30 minutes, the QHCP should bill the CPT code 99423. However, we would advise that, if this care requires more than 30 minutes, then either virtual or face-to-face E/M be considered for the optimal reimbursement for provider time spent. Another common question is around consent for services, and we advise providers to review this requirement with their compliance colleagues as each institution has different policies.

Virtual check-in

Medicare also covers brief communication technology–based services also known as virtual check-ins, where patients can communicate with their provider after having established care. During this brief conversation that can be via telephone, audio/video, secure text messaging, email, or patient portal, providers will determine if an in-person visit is necessary. CMS has designed G codes for these virtual check-ins that are from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Two codes are available for this E/M service: G2012, which is outlined in Table 1, and G2010, which covers the evaluation of images and/or recorded videos. In order to be reimbursed for a G2010 code, providers need at least a 5-minute response to make a clinical determination or give the patient a medical impression.

Patient satisfaction, physician well-being and quality of care outcomes

Large health care systems like Kaiser Permanente implemented secure message patient-physician communication (the patient portal) even before the pandemic, showing promising results in 2010 with reduction in office visits, improvement in measurable quality outcomes, and high level of patient satisfaction.10 Post pandemic, several large health care centers opted to announce the billing implementation for patient-initiated portal messages.11 A focus was placed on educating their patients about when a message will and will not be billed. Using this type of strategy can help to improve patient awareness about potential billing without affecting patient satisfaction and care outcomes. Studies have shown the EHR has contributed to physician burnout and some physicians reducing their clinical time or leaving medicine; a reduction in messaging might have a positive impact on physician well-being.

The challenge is that medical billing is not routinely included as a curriculum topic in many residency and fellowship programs; however, trainees are part of E/M services and have limited knowledge of billing processes. Unfortunately, at this time, trainees cannot submit for reimbursement for asynchronous care as described above. We hope that this brief article will help junior gastroenterologists optimize their outpatient billing practices.

Dr. Nieto is an internal medicine chief resident with WellStar Cobb Medical Center, Austell, Ga. Dr. Kinnucan is a gastroenterologist with Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose for this article. The authors certify that no financial and grant support has been received for this article.