User login

April 2018 - What's your diagnosis?

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” Chilaiditi syndrome

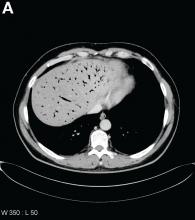

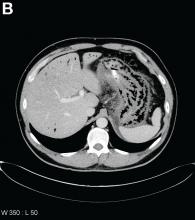

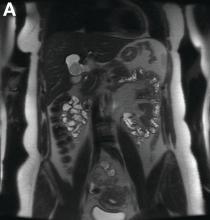

Abdominal CT images display the Chilaiditi sign, which is the radiographic term used to describe interposition of the colon, usually at the hepatic flexure, with the liver and right diaphragm.1 This is considered an incidental radiographic finding and is generally asymptomatic; however, when one develops clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating or distension, anorexia, constipation, or nausea it is called Chilaiditi syndrome.

First described by Greek radiologist Demetrius Chilaiditi in 1910, Chilaiditi syndrome is a rare occurrence with an incidence rate of 0.25%-0.28% in the general population.2 The etiology of Chilaiditi syndrome is felt to be congenital or acquired with predisposing congenital abnormalities such as absent suspensory or falciform ligaments, redundant colon, malposition of the colon, dolichocolon, and paralysis of the right diaphragm. Other risk factors for development of Chilaiditi syndrome include chronic constipation, cirrhosis, ascites, and obesity. Men are times times as likely as women to develop Chilaiditi syndrome and it is more common in the elderly, occurring in 1% of the elderly population.3 Chilaiditi sign is diagnosed with radiographic imaging meeting the following criteria: the right hemidiaphragm must be elevated above the liver by the intestine, the bowel must be distended by air to illustrate pseudopneumoperitoneum, and the superior margin of the liver must be depressed below the level of the left hemidiaphragm.1

Chilaiditi syndrome is managed conservatively with close observation. Recurrent symptoms can be treated with colopexy. This syndrome has been known to cause severe complications including volvulus of the cecum, splenic flexure, or transverse colon, cecal perforation, and subdiaphragmatic perforated appendicitis, which all require surgical intervention.3 It is important to recognize Chilaiditi syndrome on presentation to prevent unnecessary diagnostic studies and unwarranted surgical intervention.

References

1. Uygungul, E., Uygungul, D., Ayrik, C., et al. Chilaiditi sign: why are clinical findings more important in ED?. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:733.e1-733.e2.

2. Ho, M.P., Cheung, W.K., Tsai, K.C., et al. Chilaiditi syndrome mimicking subdiaphragmatic free air in an elderly adult. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2019-21.

3. Kang, D., Pan, A.S., Lopez, M.A., et al. Acute abdominal pain secondary to Chilaiditi syndrome. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:756590.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” Chilaiditi syndrome

Abdominal CT images display the Chilaiditi sign, which is the radiographic term used to describe interposition of the colon, usually at the hepatic flexure, with the liver and right diaphragm.1 This is considered an incidental radiographic finding and is generally asymptomatic; however, when one develops clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating or distension, anorexia, constipation, or nausea it is called Chilaiditi syndrome.

First described by Greek radiologist Demetrius Chilaiditi in 1910, Chilaiditi syndrome is a rare occurrence with an incidence rate of 0.25%-0.28% in the general population.2 The etiology of Chilaiditi syndrome is felt to be congenital or acquired with predisposing congenital abnormalities such as absent suspensory or falciform ligaments, redundant colon, malposition of the colon, dolichocolon, and paralysis of the right diaphragm. Other risk factors for development of Chilaiditi syndrome include chronic constipation, cirrhosis, ascites, and obesity. Men are times times as likely as women to develop Chilaiditi syndrome and it is more common in the elderly, occurring in 1% of the elderly population.3 Chilaiditi sign is diagnosed with radiographic imaging meeting the following criteria: the right hemidiaphragm must be elevated above the liver by the intestine, the bowel must be distended by air to illustrate pseudopneumoperitoneum, and the superior margin of the liver must be depressed below the level of the left hemidiaphragm.1

Chilaiditi syndrome is managed conservatively with close observation. Recurrent symptoms can be treated with colopexy. This syndrome has been known to cause severe complications including volvulus of the cecum, splenic flexure, or transverse colon, cecal perforation, and subdiaphragmatic perforated appendicitis, which all require surgical intervention.3 It is important to recognize Chilaiditi syndrome on presentation to prevent unnecessary diagnostic studies and unwarranted surgical intervention.

References

1. Uygungul, E., Uygungul, D., Ayrik, C., et al. Chilaiditi sign: why are clinical findings more important in ED?. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:733.e1-733.e2.

2. Ho, M.P., Cheung, W.K., Tsai, K.C., et al. Chilaiditi syndrome mimicking subdiaphragmatic free air in an elderly adult. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2019-21.

3. Kang, D., Pan, A.S., Lopez, M.A., et al. Acute abdominal pain secondary to Chilaiditi syndrome. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:756590.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” Chilaiditi syndrome

Abdominal CT images display the Chilaiditi sign, which is the radiographic term used to describe interposition of the colon, usually at the hepatic flexure, with the liver and right diaphragm.1 This is considered an incidental radiographic finding and is generally asymptomatic; however, when one develops clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating or distension, anorexia, constipation, or nausea it is called Chilaiditi syndrome.

First described by Greek radiologist Demetrius Chilaiditi in 1910, Chilaiditi syndrome is a rare occurrence with an incidence rate of 0.25%-0.28% in the general population.2 The etiology of Chilaiditi syndrome is felt to be congenital or acquired with predisposing congenital abnormalities such as absent suspensory or falciform ligaments, redundant colon, malposition of the colon, dolichocolon, and paralysis of the right diaphragm. Other risk factors for development of Chilaiditi syndrome include chronic constipation, cirrhosis, ascites, and obesity. Men are times times as likely as women to develop Chilaiditi syndrome and it is more common in the elderly, occurring in 1% of the elderly population.3 Chilaiditi sign is diagnosed with radiographic imaging meeting the following criteria: the right hemidiaphragm must be elevated above the liver by the intestine, the bowel must be distended by air to illustrate pseudopneumoperitoneum, and the superior margin of the liver must be depressed below the level of the left hemidiaphragm.1

Chilaiditi syndrome is managed conservatively with close observation. Recurrent symptoms can be treated with colopexy. This syndrome has been known to cause severe complications including volvulus of the cecum, splenic flexure, or transverse colon, cecal perforation, and subdiaphragmatic perforated appendicitis, which all require surgical intervention.3 It is important to recognize Chilaiditi syndrome on presentation to prevent unnecessary diagnostic studies and unwarranted surgical intervention.

References

1. Uygungul, E., Uygungul, D., Ayrik, C., et al. Chilaiditi sign: why are clinical findings more important in ED?. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:733.e1-733.e2.

2. Ho, M.P., Cheung, W.K., Tsai, K.C., et al. Chilaiditi syndrome mimicking subdiaphragmatic free air in an elderly adult. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2019-21.

3. Kang, D., Pan, A.S., Lopez, M.A., et al. Acute abdominal pain secondary to Chilaiditi syndrome. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:756590.

By Jordan Orr, MD, and Charles O. Elson III, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151[2]:241-2).

A 67-year-old man presented to the emergency department with complaints of subacute, right-sided flank pain with migratory pain to his right lower quadrant and suprapubic area of increasing intensity for 1 week. He described his pain as cramping in nature and of fluctuating intensity, acutely worse on the day of presentation. However, within 15 minutes of waiting in the emergency department his pain subsided completely. He further denied any associated nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, melena, hematochezia, dysuria, or hematuria. Vital signs and abdominal physical examination were normal. Further, laboratory testing was unremarkable including a normal urinalysis. A bedside ultrasound was negative for gallbladder pathology or nephrolithiasis; however, it revealed an abnormal appearing liver. As further diagnostic work up, an abdominopelvic computed tomography scan revealed the following images (Figures A, B). The patient was discharged from the emergency department with scheduled follow-up in the gastroenterology clinic.

What is your diagnosis and treatment?

Clinical Challenges - March 2018 What's your diagnosis?

The diagnosis: Spontaneous gallbladder perforation

References

1. Ausania, F., Guzman Suarez, S., Alvarez Garcia, H. et al. Gallbladder perforation: morbidity, mortality and preoperative risk prediction. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:955-60.

2. Niemeier, O.W. Acute free perforation of the gall-bladder. Ann Surg. 1934;99:922-4.

3. Hyodo, T., Kumano, S., Kushihata, F. et al. CT and MR cholangiography: advantages and pitfalls in perioperative evaluation of biliary tree. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:887-96.

The diagnosis: Spontaneous gallbladder perforation

References

1. Ausania, F., Guzman Suarez, S., Alvarez Garcia, H. et al. Gallbladder perforation: morbidity, mortality and preoperative risk prediction. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:955-60.

2. Niemeier, O.W. Acute free perforation of the gall-bladder. Ann Surg. 1934;99:922-4.

3. Hyodo, T., Kumano, S., Kushihata, F. et al. CT and MR cholangiography: advantages and pitfalls in perioperative evaluation of biliary tree. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:887-96.

The diagnosis: Spontaneous gallbladder perforation

References

1. Ausania, F., Guzman Suarez, S., Alvarez Garcia, H. et al. Gallbladder perforation: morbidity, mortality and preoperative risk prediction. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:955-60.

2. Niemeier, O.W. Acute free perforation of the gall-bladder. Ann Surg. 1934;99:922-4.

3. Hyodo, T., Kumano, S., Kushihata, F. et al. CT and MR cholangiography: advantages and pitfalls in perioperative evaluation of biliary tree. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:887-96.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151[1]:40-2).

What is your diagnosis and treatment?

Clinical Challenges - February 2018 What's your diagnosis?

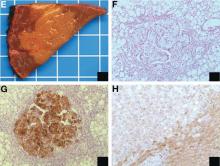

The diagnosis: Metastatic insulinoma surrounded by steatotic hepatocytes

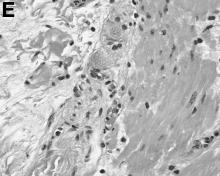

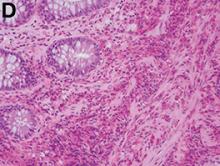

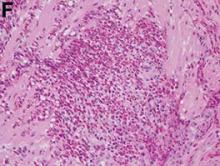

The loss of L-FABP expression in steatotic hepatocytes is the hallmark of HNF1alpha-inactivated liver adenoma,1 and clearly suggested this diagnosis. However, the emergence of multiple steatotic lesions over a short period of time was uncommon for liver adenomas. Despite the absence of radiologically detectable metastasis, this diagnosis could not be ruled out, and the patient underwent a surgical liver biopsy (tip of the right lobe). The specimen showed a 0.2 cm greyish nodule surrounded by a steatotic map-like area of 3.5 cm in the largest dimension (Figure E). Histopathologic examination showed neuroendocrine cells (Figures F [hematoxylin and eosin staining] and G [insulin immunostaining]), confirming the diagnosis of metastatic insulinoma surrounded by steatotic hepatocytes.

The key interest of the case is the reduction of L-FABP expression in the steatotic hepatocytes (Figure H [L-FABP immunostaining]), which was an unexpected finding and could have led to an incorrect diagnosis of HNF1α-inactivated liver adenoma.

In contrast with other functional neuroendocrine tumors, insulinomas are frequently benign tumors, and only about 10% of patients develop metastasis. In the liver, they are often surrounded by microscopic or radiologically detectable steatotic areas thanks to the paracrine effect of insulin. Such a feature has been previously described both with liver insulinoma metastases2 and after pancreatic islet transplantation.3 The reduction of L-FABP expression within the steatotic hepatocytes seems to be less frequent because it was not observed in an additional patient with G3 insulinoma (neuroendocrine carcinoma) metastases and in 3 pancreatic islet recipients (data not shown).

The present patient with multiple liver G2 insulinoma metastases illustrates 1) the potential of foci of steatosis to represent early signs of insulinoma liver metastasis, and 2) the presence of a reduction or even a loss of L-FABP expression in other liver lesions than HNF1alpha-inactivated liver adenoma.

Acknowledgment

Claudio De Vito’s current affiliation is Institute of Liver Studies, King’s College Hospital, London, UK.

The authors thank A.M.J. Shapiro from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada and A. Quaglia from the King’s College Hospital, London, UK for sharing the liver samples of transplanted pancreatic islets and G3 insulinoma metastasis. They are also grateful to the members of the Geneva Hepato-Biliary and Pancreatic Center for the discussion of the case.

References

1. Bioulac-Sage P., Cubel G., Taouji S., et al. Immunohistochemical markers on needle biopsies are helpful for the diagnosis of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1691-9.

2. Sohn J., Siegelman E., Osiason, A. Unusual patterns of hepatic steatosis caused by the local effect of insulin revealed on chemical shift MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:471-4.

3. Toso C., Isse K., Demetris A.J., et al. Histologic graft assessment after clinical islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1286-93.

The diagnosis: Metastatic insulinoma surrounded by steatotic hepatocytes

The loss of L-FABP expression in steatotic hepatocytes is the hallmark of HNF1alpha-inactivated liver adenoma,1 and clearly suggested this diagnosis. However, the emergence of multiple steatotic lesions over a short period of time was uncommon for liver adenomas. Despite the absence of radiologically detectable metastasis, this diagnosis could not be ruled out, and the patient underwent a surgical liver biopsy (tip of the right lobe). The specimen showed a 0.2 cm greyish nodule surrounded by a steatotic map-like area of 3.5 cm in the largest dimension (Figure E). Histopathologic examination showed neuroendocrine cells (Figures F [hematoxylin and eosin staining] and G [insulin immunostaining]), confirming the diagnosis of metastatic insulinoma surrounded by steatotic hepatocytes.

The key interest of the case is the reduction of L-FABP expression in the steatotic hepatocytes (Figure H [L-FABP immunostaining]), which was an unexpected finding and could have led to an incorrect diagnosis of HNF1α-inactivated liver adenoma.

In contrast with other functional neuroendocrine tumors, insulinomas are frequently benign tumors, and only about 10% of patients develop metastasis. In the liver, they are often surrounded by microscopic or radiologically detectable steatotic areas thanks to the paracrine effect of insulin. Such a feature has been previously described both with liver insulinoma metastases2 and after pancreatic islet transplantation.3 The reduction of L-FABP expression within the steatotic hepatocytes seems to be less frequent because it was not observed in an additional patient with G3 insulinoma (neuroendocrine carcinoma) metastases and in 3 pancreatic islet recipients (data not shown).

The present patient with multiple liver G2 insulinoma metastases illustrates 1) the potential of foci of steatosis to represent early signs of insulinoma liver metastasis, and 2) the presence of a reduction or even a loss of L-FABP expression in other liver lesions than HNF1alpha-inactivated liver adenoma.

Acknowledgment

Claudio De Vito’s current affiliation is Institute of Liver Studies, King’s College Hospital, London, UK.

The authors thank A.M.J. Shapiro from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada and A. Quaglia from the King’s College Hospital, London, UK for sharing the liver samples of transplanted pancreatic islets and G3 insulinoma metastasis. They are also grateful to the members of the Geneva Hepato-Biliary and Pancreatic Center for the discussion of the case.

References

1. Bioulac-Sage P., Cubel G., Taouji S., et al. Immunohistochemical markers on needle biopsies are helpful for the diagnosis of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1691-9.

2. Sohn J., Siegelman E., Osiason, A. Unusual patterns of hepatic steatosis caused by the local effect of insulin revealed on chemical shift MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:471-4.

3. Toso C., Isse K., Demetris A.J., et al. Histologic graft assessment after clinical islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1286-93.

The diagnosis: Metastatic insulinoma surrounded by steatotic hepatocytes

The loss of L-FABP expression in steatotic hepatocytes is the hallmark of HNF1alpha-inactivated liver adenoma,1 and clearly suggested this diagnosis. However, the emergence of multiple steatotic lesions over a short period of time was uncommon for liver adenomas. Despite the absence of radiologically detectable metastasis, this diagnosis could not be ruled out, and the patient underwent a surgical liver biopsy (tip of the right lobe). The specimen showed a 0.2 cm greyish nodule surrounded by a steatotic map-like area of 3.5 cm in the largest dimension (Figure E). Histopathologic examination showed neuroendocrine cells (Figures F [hematoxylin and eosin staining] and G [insulin immunostaining]), confirming the diagnosis of metastatic insulinoma surrounded by steatotic hepatocytes.

The key interest of the case is the reduction of L-FABP expression in the steatotic hepatocytes (Figure H [L-FABP immunostaining]), which was an unexpected finding and could have led to an incorrect diagnosis of HNF1α-inactivated liver adenoma.

In contrast with other functional neuroendocrine tumors, insulinomas are frequently benign tumors, and only about 10% of patients develop metastasis. In the liver, they are often surrounded by microscopic or radiologically detectable steatotic areas thanks to the paracrine effect of insulin. Such a feature has been previously described both with liver insulinoma metastases2 and after pancreatic islet transplantation.3 The reduction of L-FABP expression within the steatotic hepatocytes seems to be less frequent because it was not observed in an additional patient with G3 insulinoma (neuroendocrine carcinoma) metastases and in 3 pancreatic islet recipients (data not shown).

The present patient with multiple liver G2 insulinoma metastases illustrates 1) the potential of foci of steatosis to represent early signs of insulinoma liver metastasis, and 2) the presence of a reduction or even a loss of L-FABP expression in other liver lesions than HNF1alpha-inactivated liver adenoma.

Acknowledgment

Claudio De Vito’s current affiliation is Institute of Liver Studies, King’s College Hospital, London, UK.

The authors thank A.M.J. Shapiro from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada and A. Quaglia from the King’s College Hospital, London, UK for sharing the liver samples of transplanted pancreatic islets and G3 insulinoma metastasis. They are also grateful to the members of the Geneva Hepato-Biliary and Pancreatic Center for the discussion of the case.

References

1. Bioulac-Sage P., Cubel G., Taouji S., et al. Immunohistochemical markers on needle biopsies are helpful for the diagnosis of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1691-9.

2. Sohn J., Siegelman E., Osiason, A. Unusual patterns of hepatic steatosis caused by the local effect of insulin revealed on chemical shift MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:471-4.

3. Toso C., Isse K., Demetris A.J., et al. Histologic graft assessment after clinical islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1286-93.

By Claudio De Vito, MD, PhD, Laura Rubbia-Brandt, MD, PhD, and Christian Toso, MD, PhD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151[1]32, 330).

A 22-year-old woman with no past medical history was investigated for hypoglycemia episodes. A nodule located in the head of the pancreas was identified, with radiologic features of a neuroendocrine neoplasm. The overall clinical presentation was consistent with an insulinoma. No distant lesion was detected. She underwent a Whipple procedure, and the histopathologic examination reported a 2.2-cm, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (insulinoma) G2 (4% Ki-67 index), with no lymphovascular invasion or lymph node metastasis (0 of 30 lymph nodes).

Clinical Challenges - January 2018 What's your diagnosis?

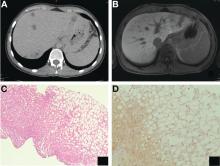

The diagnosis

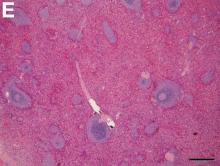

Answer: Posttraumatic splenosis

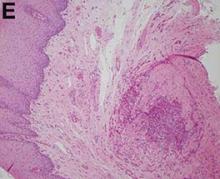

Pathologic examination of the specimen revealed a splenosis showing regular red and white pulp (Figure E). Splenosis is the heterotopic autotransplantation of splenic tissue within the abdominal or pelvic cavity and occurs in 16%–67% of patients with a history of splenic trauma or splenic surgery.1 Nevertheless, hepatic splenosis is rare.2 The literature documents only 16 case reports of hepatic splenosis, although the difficulty of diagnosis could have contributed to underreporting. Although usually harmless, splenosis is a rare cause of bowel obstruction or abdominal pain.

References

1. Fleming, C.R., Dickson, E.R., Harrison, E.G. Splenosis: autotransplantation of splenic tissue. Am J Med. 1976;61:414-9.

2. D’Angelica, M., Fong, Y., Blumgart, L.H. Isolated hepatic splenosis: first reported case. HPB Surg. 1998;11:39-42.

3. Ohmoto, K., Mimura, N., Iguchi, Y. et al. Percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy for superficial hepatocellular carcinoma on the surface of the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1547-51.

The diagnosis

Answer: Posttraumatic splenosis

Pathologic examination of the specimen revealed a splenosis showing regular red and white pulp (Figure E). Splenosis is the heterotopic autotransplantation of splenic tissue within the abdominal or pelvic cavity and occurs in 16%–67% of patients with a history of splenic trauma or splenic surgery.1 Nevertheless, hepatic splenosis is rare.2 The literature documents only 16 case reports of hepatic splenosis, although the difficulty of diagnosis could have contributed to underreporting. Although usually harmless, splenosis is a rare cause of bowel obstruction or abdominal pain.

References

1. Fleming, C.R., Dickson, E.R., Harrison, E.G. Splenosis: autotransplantation of splenic tissue. Am J Med. 1976;61:414-9.

2. D’Angelica, M., Fong, Y., Blumgart, L.H. Isolated hepatic splenosis: first reported case. HPB Surg. 1998;11:39-42.

3. Ohmoto, K., Mimura, N., Iguchi, Y. et al. Percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy for superficial hepatocellular carcinoma on the surface of the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1547-51.

The diagnosis

Answer: Posttraumatic splenosis

Pathologic examination of the specimen revealed a splenosis showing regular red and white pulp (Figure E). Splenosis is the heterotopic autotransplantation of splenic tissue within the abdominal or pelvic cavity and occurs in 16%–67% of patients with a history of splenic trauma or splenic surgery.1 Nevertheless, hepatic splenosis is rare.2 The literature documents only 16 case reports of hepatic splenosis, although the difficulty of diagnosis could have contributed to underreporting. Although usually harmless, splenosis is a rare cause of bowel obstruction or abdominal pain.

References

1. Fleming, C.R., Dickson, E.R., Harrison, E.G. Splenosis: autotransplantation of splenic tissue. Am J Med. 1976;61:414-9.

2. D’Angelica, M., Fong, Y., Blumgart, L.H. Isolated hepatic splenosis: first reported case. HPB Surg. 1998;11:39-42.

3. Ohmoto, K., Mimura, N., Iguchi, Y. et al. Percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy for superficial hepatocellular carcinoma on the surface of the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1547-51.

By Mareike Röther, MD, Jean-Francois Dufour, MD, and Beat Schnüriger, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144[3]:510, 659).

What is your diagnosis and treatment?

Clinical Challenges - December 2017 What's your diagnosis?

The diagnosis

Answer: Hydrogen peroxide ingestion causing significant portal venous gas and stomach wall thickening

Upon further questioning, it was found that the patient accidentally ingested approximately 50 mL of concentrated 35% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) solution, which he was using in diluted form as a naturopathic treatment for his diabetes mellitus. He was admitted to our institution and closely monitored for evidence of perforation and respiratory distress. Given the extent of portal venous gas, he was promptly treated with hyperbaric oxygen to prevent cerebral gas embolism. Clinically, he remained stable over the next 24 hours and repeat imaging the next day revealed dramatic improvement of the portal venous gas (Figure C). He was discharged on day 4 of hospitalization with no obvious clinical sequelae. Outpatient gastroscopy was arranged to assess any further potential damage, but he was lost to follow-up.

References

1. Watt, B.E., Proudfoot, A.T., Vale, J.A. Hydrogen peroxide poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2004;23:51-7.

2. French, L.K., Horowitz, B.Z., McKeown, N.J. Hydrogen peroxide ingestion associated with portal venous gas and treatment with hyperbaric oxygen: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:533-8.

The diagnosis

Answer: Hydrogen peroxide ingestion causing significant portal venous gas and stomach wall thickening

Upon further questioning, it was found that the patient accidentally ingested approximately 50 mL of concentrated 35% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) solution, which he was using in diluted form as a naturopathic treatment for his diabetes mellitus. He was admitted to our institution and closely monitored for evidence of perforation and respiratory distress. Given the extent of portal venous gas, he was promptly treated with hyperbaric oxygen to prevent cerebral gas embolism. Clinically, he remained stable over the next 24 hours and repeat imaging the next day revealed dramatic improvement of the portal venous gas (Figure C). He was discharged on day 4 of hospitalization with no obvious clinical sequelae. Outpatient gastroscopy was arranged to assess any further potential damage, but he was lost to follow-up.

References

1. Watt, B.E., Proudfoot, A.T., Vale, J.A. Hydrogen peroxide poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2004;23:51-7.

2. French, L.K., Horowitz, B.Z., McKeown, N.J. Hydrogen peroxide ingestion associated with portal venous gas and treatment with hyperbaric oxygen: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:533-8.

The diagnosis

Answer: Hydrogen peroxide ingestion causing significant portal venous gas and stomach wall thickening

Upon further questioning, it was found that the patient accidentally ingested approximately 50 mL of concentrated 35% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) solution, which he was using in diluted form as a naturopathic treatment for his diabetes mellitus. He was admitted to our institution and closely monitored for evidence of perforation and respiratory distress. Given the extent of portal venous gas, he was promptly treated with hyperbaric oxygen to prevent cerebral gas embolism. Clinically, he remained stable over the next 24 hours and repeat imaging the next day revealed dramatic improvement of the portal venous gas (Figure C). He was discharged on day 4 of hospitalization with no obvious clinical sequelae. Outpatient gastroscopy was arranged to assess any further potential damage, but he was lost to follow-up.

References

1. Watt, B.E., Proudfoot, A.T., Vale, J.A. Hydrogen peroxide poisoning. Toxicol Rev. 2004;23:51-7.

2. French, L.K., Horowitz, B.Z., McKeown, N.J. Hydrogen peroxide ingestion associated with portal venous gas and treatment with hyperbaric oxygen: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Toxicol. 2010;48:533-8.

By Mark C. Fok, BScPharm, Charles Zwirewich, MD, and Baljinder S. Salh, MBChB. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144[3]:509, 658-9).

A 49-year-old man presented with severe epigastric pain and nonbloody emesis after ingestion of a naturopathic treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

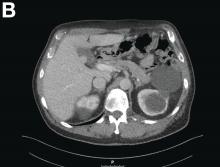

Urgent abdominal computed tomography was performed, which revealed extensive portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A) and pneumatosis with thickening of the stomach wall (Figure B).

What is your diagnosis and treatment?

Clinical Challenges - November 2017 What's your diagnosis?

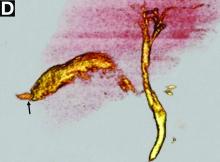

The diagnosis

Answer: Hepatic foregut duplication cyst and concurrent acute gangrenous cholecystitis

References

1. Imamoglu K.H., Walt, A.J. Duplication of the duodenum extending into liver. Am J Surg. 1977;133:628-32.

2. Seidman J.D., Yale-Loehr A.J., Beaver B., et al. Alimentary duplication presenting as an hepatic cyst in a neonate. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:695-8.

3. Vick D.J., Goodman Z.D., Deavers M.T., et al. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst: A study of six cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:671-7.

The diagnosis

Answer: Hepatic foregut duplication cyst and concurrent acute gangrenous cholecystitis

References

1. Imamoglu K.H., Walt, A.J. Duplication of the duodenum extending into liver. Am J Surg. 1977;133:628-32.

2. Seidman J.D., Yale-Loehr A.J., Beaver B., et al. Alimentary duplication presenting as an hepatic cyst in a neonate. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:695-8.

3. Vick D.J., Goodman Z.D., Deavers M.T., et al. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst: A study of six cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:671-7.

The diagnosis

Answer: Hepatic foregut duplication cyst and concurrent acute gangrenous cholecystitis

References

1. Imamoglu K.H., Walt, A.J. Duplication of the duodenum extending into liver. Am J Surg. 1977;133:628-32.

2. Seidman J.D., Yale-Loehr A.J., Beaver B., et al. Alimentary duplication presenting as an hepatic cyst in a neonate. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:695-8.

3. Vick D.J., Goodman Z.D., Deavers M.T., et al. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst: A study of six cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:671-7.

By Ryan Law, MD, Thomas C. Smyrk, and Stephen C. Hauser. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144[3]:508, 658).

A 43-year-old woman presented with progressively worsening right upper-quadrant abdominal pain. The episodic pain occurred after high-fat meals and lasted from minutes to hours with accompanying nausea. Her previous medical history was notable for endometriosis. She denied other constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed no hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, right upper-quadrant mass, or stigmata of chronic liver disease.

Initial laboratory evaluation yielded normal white blood cell count and liver chemistries. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen all demonstrated a 2.0 × 4.1 × 3.9-cm, nonenhancing, elongated, cystic mass located superior to the gallbladder within the porta hepatis, with possible communication at the bile duct confluence and abutment of the right portal vein (Figure A). No definitive findings of acute cholecystitis were present.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic ultrasonography was performed to further delineate the anatomy of the lesion. On endoscopic ultrasonography, the structure in question seemed to be embedded in the hepatic parenchyma with partial extension beyond the liver edge. Adherent debris was noted within the cystic structure. No lymphadenopathy was present. Cholangiography demonstrated filling of the lesion from a central right intrahepatic duct (Figure B). Attempts at cannulation of the cyst were unsuccessful.

The patient subsequently developed abnormal liver chemistries with continued right upper-quadrant pain. She was referred to an experienced hepatobiliary surgeon and underwent operative intervention. What is the diagnosis and how would you treat this patient?

Clinical Challenges - October 2017 What's your diagnosis?

The diagnosis

Answer: Necrolytic acral erythema

The patient’s clinicopathologic picture is consistent with necrolytic acral erythema (NAE). Notably, her serum zinc level was 121 mcg/dL (normal is greater than 55 mcg/dL). The patient was started on oral zinc supplementation. Several days after initiation of zinc therapy, her pain and pruritus dramatically improved.

NAE is a rare condition, first described in a cohort study of seven Egyptian patients with active HCV infection in 1996, and is considered a distinctive cutaneous presentation of HCV infection.1 Clinical presentation typically involves severe pruritus on acral surfaces accompanied by pain and a burning sensation. The skin findings include well-circumscribed, dusky, erythematous to hyperpigmented plaques with variable scaling and erosion that extend from dorsal feet to the legs. The pathogenesis of NAE remains unknown. However, it has been proposed that zinc deficiency and dysregulation secondary to hepatocellular dysfunction in HCV infection, is associated with NAE.2

Zinc supplementation has shown favorable outcomes in NAE patients with zinc deficiency.3 However, the appropriate threshold of serum zinc level in patients with NAE is unclear. Herein, we have reported a patient with NAE who responded to zinc supplementation despite a normal zinc level. A plausible explanation is that clinical zinc deficiency may occur in the skin before the development of decreased serum zinc levels.

Skin pruritus is a common presentation in patients with chronic HCV infection. Increased awareness of the distinct features of NAE may result in early diagnosis and initiation of effective therapy. Zinc supplementation may be beneficial in NAE patients with and without decreased serum zinc level.

References

1. el Darouti, M., Abu el Ela, M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-6.

2. Hadziyannis, S.J. Skin diseases associated with hepatitis C virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;10:12-21.

3. Abdallah, M.A., Hull, C., Horn, T.D. Necrolytic acral erythema: A patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-7.

The diagnosis

Answer: Necrolytic acral erythema

The patient’s clinicopathologic picture is consistent with necrolytic acral erythema (NAE). Notably, her serum zinc level was 121 mcg/dL (normal is greater than 55 mcg/dL). The patient was started on oral zinc supplementation. Several days after initiation of zinc therapy, her pain and pruritus dramatically improved.

NAE is a rare condition, first described in a cohort study of seven Egyptian patients with active HCV infection in 1996, and is considered a distinctive cutaneous presentation of HCV infection.1 Clinical presentation typically involves severe pruritus on acral surfaces accompanied by pain and a burning sensation. The skin findings include well-circumscribed, dusky, erythematous to hyperpigmented plaques with variable scaling and erosion that extend from dorsal feet to the legs. The pathogenesis of NAE remains unknown. However, it has been proposed that zinc deficiency and dysregulation secondary to hepatocellular dysfunction in HCV infection, is associated with NAE.2

Zinc supplementation has shown favorable outcomes in NAE patients with zinc deficiency.3 However, the appropriate threshold of serum zinc level in patients with NAE is unclear. Herein, we have reported a patient with NAE who responded to zinc supplementation despite a normal zinc level. A plausible explanation is that clinical zinc deficiency may occur in the skin before the development of decreased serum zinc levels.

Skin pruritus is a common presentation in patients with chronic HCV infection. Increased awareness of the distinct features of NAE may result in early diagnosis and initiation of effective therapy. Zinc supplementation may be beneficial in NAE patients with and without decreased serum zinc level.

References

1. el Darouti, M., Abu el Ela, M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-6.

2. Hadziyannis, S.J. Skin diseases associated with hepatitis C virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;10:12-21.

3. Abdallah, M.A., Hull, C., Horn, T.D. Necrolytic acral erythema: A patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-7.

The diagnosis

Answer: Necrolytic acral erythema

The patient’s clinicopathologic picture is consistent with necrolytic acral erythema (NAE). Notably, her serum zinc level was 121 mcg/dL (normal is greater than 55 mcg/dL). The patient was started on oral zinc supplementation. Several days after initiation of zinc therapy, her pain and pruritus dramatically improved.

NAE is a rare condition, first described in a cohort study of seven Egyptian patients with active HCV infection in 1996, and is considered a distinctive cutaneous presentation of HCV infection.1 Clinical presentation typically involves severe pruritus on acral surfaces accompanied by pain and a burning sensation. The skin findings include well-circumscribed, dusky, erythematous to hyperpigmented plaques with variable scaling and erosion that extend from dorsal feet to the legs. The pathogenesis of NAE remains unknown. However, it has been proposed that zinc deficiency and dysregulation secondary to hepatocellular dysfunction in HCV infection, is associated with NAE.2

Zinc supplementation has shown favorable outcomes in NAE patients with zinc deficiency.3 However, the appropriate threshold of serum zinc level in patients with NAE is unclear. Herein, we have reported a patient with NAE who responded to zinc supplementation despite a normal zinc level. A plausible explanation is that clinical zinc deficiency may occur in the skin before the development of decreased serum zinc levels.

Skin pruritus is a common presentation in patients with chronic HCV infection. Increased awareness of the distinct features of NAE may result in early diagnosis and initiation of effective therapy. Zinc supplementation may be beneficial in NAE patients with and without decreased serum zinc level.

References

1. el Darouti, M., Abu el Ela, M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-6.

2. Hadziyannis, S.J. Skin diseases associated with hepatitis C virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;10:12-21.

3. Abdallah, M.A., Hull, C., Horn, T.D. Necrolytic acral erythema: A patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-7.

By Mazen Albeldawi, MD, Vivian Ebrahim, MD, and Dian Jung Chiang, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144[2]:275, 469)

A 53-year-old woman with hepatitis C virus (HCV) cirrhosis was admitted to our inpatient service with several days of progressive bilateral lower extremity pruritus, accompanied by severe pain and parasthesias.

She had experienced intermittent pruritus for 2 years, but symptoms had become more severe in the 4 days before admission. Her pain was stabbing in nature and without radiation. Her pruritus has been refractory to multiple therapies including hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine, sertraline, cholestyramine, rifampin, naltrexone, topical steroids, and narrow-band ultraviolet B light therapy. She was hospitalized in March 2010 for a similar episode of intractable pruritus and pain, at which time she was diagnosed with lichen simplex chronicus. Plasmapheresis was attempted but abruptly stopped because of a blood stream infection. The patient was diagnosed with HCV cirrhosis (genotype 1A) in 2006 and was a nonresponder at 12 weeks to peginterferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Upon admission, her medications included sertraline 150 mg daily, hydroxyzine 25 mg 3 times daily, oxycodone-acetaminophen 5-325 mg every 4 hours, and clobetasol 0.05% ointment.

On examination, hyperpigmented, lichenified plaques with erosions involving the bilateral lower extremities, extending from the calves to the dorsal aspect of both feet were noted (Figures A and B)

Clinical Challenges - August 2017 What is the likely diagnosis and pathogenetic mechanisms?

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Lemmel’s syndrome

References

1. Egawa, N., Anjiki, H., Takuma, K., et al. Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula and pancreatobiliary disease. Dig Surg. 2010;27:105-9.

2. Lobo, D.N., Balfour, T.W., Iftikhar, S.Y. Periampullary diverticula: consequences of failed ERCP. Ann Royal Coll Surg. 1998;80:326-31.

3. Lemmel, G. Die klinische Bedeutung der Duodenaldivertikel. Archiv fur Verdauungskrankheiten. 1934;56:59-70.

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Lemmel’s syndrome

References

1. Egawa, N., Anjiki, H., Takuma, K., et al. Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula and pancreatobiliary disease. Dig Surg. 2010;27:105-9.

2. Lobo, D.N., Balfour, T.W., Iftikhar, S.Y. Periampullary diverticula: consequences of failed ERCP. Ann Royal Coll Surg. 1998;80:326-31.

3. Lemmel, G. Die klinische Bedeutung der Duodenaldivertikel. Archiv fur Verdauungskrankheiten. 1934;56:59-70.

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Lemmel’s syndrome

References

1. Egawa, N., Anjiki, H., Takuma, K., et al. Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula and pancreatobiliary disease. Dig Surg. 2010;27:105-9.

2. Lobo, D.N., Balfour, T.W., Iftikhar, S.Y. Periampullary diverticula: consequences of failed ERCP. Ann Royal Coll Surg. 1998;80:326-31.

3. Lemmel, G. Die klinische Bedeutung der Duodenaldivertikel. Archiv fur Verdauungskrankheiten. 1934;56:59-70.

By Crispin Musumba, MBChB, PhD, Edward Britton, MBBS, MRCP, and Howard Smart, MBBS, DM. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144:274, 468-469).

Clinical Challenges - July 2017 What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

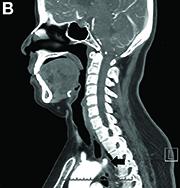

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Dysphagia lusoria

Dysphagia may be divided into an oropharyngeal cause or an esophageal cause. Esophageal dysphagia may be due to a luminal narrowing or a motility dysfunction. Causes of luminal narrowing include lesions within the lumen such as a foreign body, lesions within the wall of the esophagus such as a mucosal or submucosal tumor, and extrinsic lesions such as an enlarged mediastinal lymph node or mass. Esophageal dysphagia typically presents with difficulty in swallowing solids compared with liquids.

Evaluation of this condition involves a barium swallow study, CTA, or magnetic resonance angiography.2 Both CTA and MRA have largely supplanted the role of conventional angiography, which is invasive. Both CTA and magnetic resonance angiography may also diagnose any other intrathoracic pathology causing esophageal compression. The management of patients with mild to moderate dysphagia is diet modification (minced feeds to well-chewed food; eating slowly and with liquids). Vascular repair of the aberrant vessel is considered only if the patient has severe symptoms and has failed conservative management.3 Because our subject did not have significant weight loss or regurgitation, only dietary advice was offered. An interval outpatient upper endoscopy was planned upon discharge, for which she defaulted.

References

1. Bayford. An account of a singular case of obstructed degluitition. Memoirs of the Medical Society of London. 1794;2:275-86.

2. Alper, F., Akgun, M., Kantarci, M. et al. Demonstration of vascular abnormalities compressing esophagus by MDCT: special focus on dysphagia lusoria. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:82-7.

3. Levitt, B. and Richter, J.E. Dysphagia lusoria: a comprehensive review. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:455-60.

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Dysphagia lusoria

Dysphagia may be divided into an oropharyngeal cause or an esophageal cause. Esophageal dysphagia may be due to a luminal narrowing or a motility dysfunction. Causes of luminal narrowing include lesions within the lumen such as a foreign body, lesions within the wall of the esophagus such as a mucosal or submucosal tumor, and extrinsic lesions such as an enlarged mediastinal lymph node or mass. Esophageal dysphagia typically presents with difficulty in swallowing solids compared with liquids.

Evaluation of this condition involves a barium swallow study, CTA, or magnetic resonance angiography.2 Both CTA and MRA have largely supplanted the role of conventional angiography, which is invasive. Both CTA and magnetic resonance angiography may also diagnose any other intrathoracic pathology causing esophageal compression. The management of patients with mild to moderate dysphagia is diet modification (minced feeds to well-chewed food; eating slowly and with liquids). Vascular repair of the aberrant vessel is considered only if the patient has severe symptoms and has failed conservative management.3 Because our subject did not have significant weight loss or regurgitation, only dietary advice was offered. An interval outpatient upper endoscopy was planned upon discharge, for which she defaulted.

References

1. Bayford. An account of a singular case of obstructed degluitition. Memoirs of the Medical Society of London. 1794;2:275-86.

2. Alper, F., Akgun, M., Kantarci, M. et al. Demonstration of vascular abnormalities compressing esophagus by MDCT: special focus on dysphagia lusoria. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:82-7.

3. Levitt, B. and Richter, J.E. Dysphagia lusoria: a comprehensive review. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:455-60.

The diagnosis

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Dysphagia lusoria

Dysphagia may be divided into an oropharyngeal cause or an esophageal cause. Esophageal dysphagia may be due to a luminal narrowing or a motility dysfunction. Causes of luminal narrowing include lesions within the lumen such as a foreign body, lesions within the wall of the esophagus such as a mucosal or submucosal tumor, and extrinsic lesions such as an enlarged mediastinal lymph node or mass. Esophageal dysphagia typically presents with difficulty in swallowing solids compared with liquids.

Evaluation of this condition involves a barium swallow study, CTA, or magnetic resonance angiography.2 Both CTA and MRA have largely supplanted the role of conventional angiography, which is invasive. Both CTA and magnetic resonance angiography may also diagnose any other intrathoracic pathology causing esophageal compression. The management of patients with mild to moderate dysphagia is diet modification (minced feeds to well-chewed food; eating slowly and with liquids). Vascular repair of the aberrant vessel is considered only if the patient has severe symptoms and has failed conservative management.3 Because our subject did not have significant weight loss or regurgitation, only dietary advice was offered. An interval outpatient upper endoscopy was planned upon discharge, for which she defaulted.

References

1. Bayford. An account of a singular case of obstructed degluitition. Memoirs of the Medical Society of London. 1794;2:275-86.

2. Alper, F., Akgun, M., Kantarci, M. et al. Demonstration of vascular abnormalities compressing esophagus by MDCT: special focus on dysphagia lusoria. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:82-7.

3. Levitt, B. and Richter, J.E. Dysphagia lusoria: a comprehensive review. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:455-60.

What’s your diagnosis?

By Eric Wee, MD and Ma Clarissa Buenaseda, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144:273,467,468).

Clinical Challenges - June 2017 What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

Answer: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Our patient’s positive filarial serology, although not associated with EGE in the literature, is the first known documented association between likely filariasis and EGE. She is presently being further evaluated for active filarial parasitemia and consideration of diethylcarbamazine therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jay Luther for his guidance and manuscript review and Dr. Daniel Pratt for obtaining images.

References

1. Chen, M.J., Chu, C.H., Lin, S.C., et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813-6.

2. Hepburn, I.S., Sridhar, S., Schade, R.R. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a case report and review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2010;1:166-70.

3. Ogasa, M., Nakamura, Y., Sanai, H., et al. A case of pregnancy associated hypereosinophilia with hyperpermeability symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;62:14-6.

Answer: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Our patient’s positive filarial serology, although not associated with EGE in the literature, is the first known documented association between likely filariasis and EGE. She is presently being further evaluated for active filarial parasitemia and consideration of diethylcarbamazine therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jay Luther for his guidance and manuscript review and Dr. Daniel Pratt for obtaining images.

References

1. Chen, M.J., Chu, C.H., Lin, S.C., et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813-6.

2. Hepburn, I.S., Sridhar, S., Schade, R.R. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a case report and review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2010;1:166-70.

3. Ogasa, M., Nakamura, Y., Sanai, H., et al. A case of pregnancy associated hypereosinophilia with hyperpermeability symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;62:14-6.

Answer: Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Our patient’s positive filarial serology, although not associated with EGE in the literature, is the first known documented association between likely filariasis and EGE. She is presently being further evaluated for active filarial parasitemia and consideration of diethylcarbamazine therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jay Luther for his guidance and manuscript review and Dr. Daniel Pratt for obtaining images.

References

1. Chen, M.J., Chu, C.H., Lin, S.C., et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813-6.

2. Hepburn, I.S., Sridhar, S., Schade, R.R. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a case report and review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2010;1:166-70.

3. Ogasa, M., Nakamura, Y., Sanai, H., et al. A case of pregnancy associated hypereosinophilia with hyperpermeability symptoms. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;62:14-6.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

By Ravi B. Parikh, MD, George A. Alba, MD, and Lawrence R. Zukerberg, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144;272, 467).

Upon admittance to the general medicine service, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. She did not have any stigmata of chronic liver disease. Her abdomen was distended and diffusely tender with rebound tenderness and guarding (Figure A). Serum studies were notable for white blood cell count of 14.5 x 103/microL, with 46% eosinophils (absolute count 6660/mm3). Other values, including serum human chorionic gonadotropin, were normal.

What is the diagnosis? What is the appropriate management?