User login

Clinical Challenges - May 2017 What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Arteriovenous fistulas arising from the subclavian and coronary arteries

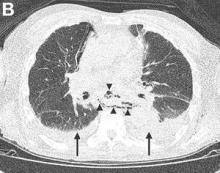

We performed aortography along with coronary angiography to find the feeding vessels for the vascular bundle (). There was an arteriovenous fistula that arose from the left subclavian artery, ran over the left mediastinum with the complex plexus, and emptied into the venous system of the left thorax. Multiple coronary artery fistulas originated in the left coronary artery, traversed the left and right mediastinum, and eventually emptied into the venous system of the mediastinum. The left anterior oblique view revealed a coronary artery fistula that arose from the distal right coronary artery and drained into the venous system of the thorax. In transthoracic echocardiography, the sizes of the left atrium and left ventricle were mildly dilated, but left ventricular systolic functions were preserved with an ejection fraction of 61%. We recommended surgery to the patient, but he refused invasive treatment. He will be followed with close observation.

A coronary artery fistula is usually of congenital origin, and connects a major coronary artery directly with the cardiac chamber, coronary sinus, superior vena cava, or pulmonary artery. However, its connection with a systemic venous system is extremely rare. Congenital subclavian arteriovenous fistulas are rare because they usually occur as a complication of previous trauma, percutaneous catheterization, or surgery.1 Complications include “steal” from the adjacent myocardium causing myocardial ischemia, thrombosis/embolism, cardiac failure, atrial fibrillation, rupture, endocarditis/endarteritis, and arrhythmia.2 Treatment options include close medical observation, surgical ligation, and catheter embolization.3

References

1. Brountzos, E.N., Kelekis, N.L., Danassi-Afentaki, D. et al. Congenital subclavian artery-to-subclavian vein fistula in an adult: treatment with transcatheter embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:675-7.

2. Wilde, P., Watt, I. Congenital coronary artery fistulae: six new cases with a collective review. Clin Radiol. 1980;31:301-11.

3. Mangukia, C.V. Coronary artery fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:2084-92.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Arteriovenous fistulas arising from the subclavian and coronary arteries

We performed aortography along with coronary angiography to find the feeding vessels for the vascular bundle (). There was an arteriovenous fistula that arose from the left subclavian artery, ran over the left mediastinum with the complex plexus, and emptied into the venous system of the left thorax. Multiple coronary artery fistulas originated in the left coronary artery, traversed the left and right mediastinum, and eventually emptied into the venous system of the mediastinum. The left anterior oblique view revealed a coronary artery fistula that arose from the distal right coronary artery and drained into the venous system of the thorax. In transthoracic echocardiography, the sizes of the left atrium and left ventricle were mildly dilated, but left ventricular systolic functions were preserved with an ejection fraction of 61%. We recommended surgery to the patient, but he refused invasive treatment. He will be followed with close observation.

A coronary artery fistula is usually of congenital origin, and connects a major coronary artery directly with the cardiac chamber, coronary sinus, superior vena cava, or pulmonary artery. However, its connection with a systemic venous system is extremely rare. Congenital subclavian arteriovenous fistulas are rare because they usually occur as a complication of previous trauma, percutaneous catheterization, or surgery.1 Complications include “steal” from the adjacent myocardium causing myocardial ischemia, thrombosis/embolism, cardiac failure, atrial fibrillation, rupture, endocarditis/endarteritis, and arrhythmia.2 Treatment options include close medical observation, surgical ligation, and catheter embolization.3

References

1. Brountzos, E.N., Kelekis, N.L., Danassi-Afentaki, D. et al. Congenital subclavian artery-to-subclavian vein fistula in an adult: treatment with transcatheter embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:675-7.

2. Wilde, P., Watt, I. Congenital coronary artery fistulae: six new cases with a collective review. Clin Radiol. 1980;31:301-11.

3. Mangukia, C.V. Coronary artery fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:2084-92.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Arteriovenous fistulas arising from the subclavian and coronary arteries

We performed aortography along with coronary angiography to find the feeding vessels for the vascular bundle (). There was an arteriovenous fistula that arose from the left subclavian artery, ran over the left mediastinum with the complex plexus, and emptied into the venous system of the left thorax. Multiple coronary artery fistulas originated in the left coronary artery, traversed the left and right mediastinum, and eventually emptied into the venous system of the mediastinum. The left anterior oblique view revealed a coronary artery fistula that arose from the distal right coronary artery and drained into the venous system of the thorax. In transthoracic echocardiography, the sizes of the left atrium and left ventricle were mildly dilated, but left ventricular systolic functions were preserved with an ejection fraction of 61%. We recommended surgery to the patient, but he refused invasive treatment. He will be followed with close observation.

A coronary artery fistula is usually of congenital origin, and connects a major coronary artery directly with the cardiac chamber, coronary sinus, superior vena cava, or pulmonary artery. However, its connection with a systemic venous system is extremely rare. Congenital subclavian arteriovenous fistulas are rare because they usually occur as a complication of previous trauma, percutaneous catheterization, or surgery.1 Complications include “steal” from the adjacent myocardium causing myocardial ischemia, thrombosis/embolism, cardiac failure, atrial fibrillation, rupture, endocarditis/endarteritis, and arrhythmia.2 Treatment options include close medical observation, surgical ligation, and catheter embolization.3

References

1. Brountzos, E.N., Kelekis, N.L., Danassi-Afentaki, D. et al. Congenital subclavian artery-to-subclavian vein fistula in an adult: treatment with transcatheter embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:675-7.

2. Wilde, P., Watt, I. Congenital coronary artery fistulae: six new cases with a collective review. Clin Radiol. 1980;31:301-11.

3. Mangukia, C.V. Coronary artery fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:2084-92.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

By Ki-Hyun Ryu, MD, Tae-Hee Lee, MD, and Taek-Geun Kwon, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144;35, 253).

Clinical Challenges - April 2017 What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page X: Pseudoachalasia in paraneoplastic syndrome, with radiographic documentation of onset and evolution

A barium esophagogram revealed an esophagus with characteristic features of achalasia: dilatation, retention of air and fluid, and a “bird’s beak” configuration distally (Figure E). Botulinum injection into the distal esophagus provided the patient with partial relief of her swallowing symptoms.

Evidence supporting the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia associated with paraneoplastic syndrome in this patient is 1) the development of characteristic features of achalasia in association with SCLC, the cancer that is most often associated with paraneoplastic achalasia;1 2) a serum antibody characteristic of SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndrome; 3) peripheral neuropathy attributed to paraneoplastic syndrome; and 4) absence of an obstructive neoplasm at the gastroesophageal junction.

Pseudoachalasia associated with malignancy may occur by one of three mechanisms1-3: 1) Primary or secondary carcinoma located at or near the gastroesophageal junction, 2) neural invasion of the esophagus, or 3) as a component of the paraneoplastic syndrome. Pseudoachalasia associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome is rare (an estimated 1 in 750,000), although it may be becoming more common.1 The relatively rapid onset of dysphagia is a reported feature of pseudoachalasia, in contrast with the more gradual onset in primary achalasia. Our report documents radiographically the progression within a few months from a normal-diameter esophagus to a very dilated, poorly functioning esophagus. We know of no similar report. Botulinum toxin injection has been reported effective in a few cases.1

References

1. Katzka, D.A., Farrugia, G., Arora, A.S., et al. Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:331-6.

2. Liu, W., Fackler, W., Rice, T.W., et al. The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia (A clinicopathological study of 13 cases of a rare entity). Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:784-8.

3. Gockel, J., Eckardt, V.F., Scmitt, T., et al. Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:378-85.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page X: Pseudoachalasia in paraneoplastic syndrome, with radiographic documentation of onset and evolution

A barium esophagogram revealed an esophagus with characteristic features of achalasia: dilatation, retention of air and fluid, and a “bird’s beak” configuration distally (Figure E). Botulinum injection into the distal esophagus provided the patient with partial relief of her swallowing symptoms.

Evidence supporting the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia associated with paraneoplastic syndrome in this patient is 1) the development of characteristic features of achalasia in association with SCLC, the cancer that is most often associated with paraneoplastic achalasia;1 2) a serum antibody characteristic of SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndrome; 3) peripheral neuropathy attributed to paraneoplastic syndrome; and 4) absence of an obstructive neoplasm at the gastroesophageal junction.

Pseudoachalasia associated with malignancy may occur by one of three mechanisms1-3: 1) Primary or secondary carcinoma located at or near the gastroesophageal junction, 2) neural invasion of the esophagus, or 3) as a component of the paraneoplastic syndrome. Pseudoachalasia associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome is rare (an estimated 1 in 750,000), although it may be becoming more common.1 The relatively rapid onset of dysphagia is a reported feature of pseudoachalasia, in contrast with the more gradual onset in primary achalasia. Our report documents radiographically the progression within a few months from a normal-diameter esophagus to a very dilated, poorly functioning esophagus. We know of no similar report. Botulinum toxin injection has been reported effective in a few cases.1

References

1. Katzka, D.A., Farrugia, G., Arora, A.S., et al. Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:331-6.

2. Liu, W., Fackler, W., Rice, T.W., et al. The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia (A clinicopathological study of 13 cases of a rare entity). Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:784-8.

3. Gockel, J., Eckardt, V.F., Scmitt, T., et al. Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:378-85.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page X: Pseudoachalasia in paraneoplastic syndrome, with radiographic documentation of onset and evolution

A barium esophagogram revealed an esophagus with characteristic features of achalasia: dilatation, retention of air and fluid, and a “bird’s beak” configuration distally (Figure E). Botulinum injection into the distal esophagus provided the patient with partial relief of her swallowing symptoms.

Evidence supporting the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia associated with paraneoplastic syndrome in this patient is 1) the development of characteristic features of achalasia in association with SCLC, the cancer that is most often associated with paraneoplastic achalasia;1 2) a serum antibody characteristic of SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndrome; 3) peripheral neuropathy attributed to paraneoplastic syndrome; and 4) absence of an obstructive neoplasm at the gastroesophageal junction.

Pseudoachalasia associated with malignancy may occur by one of three mechanisms1-3: 1) Primary or secondary carcinoma located at or near the gastroesophageal junction, 2) neural invasion of the esophagus, or 3) as a component of the paraneoplastic syndrome. Pseudoachalasia associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome is rare (an estimated 1 in 750,000), although it may be becoming more common.1 The relatively rapid onset of dysphagia is a reported feature of pseudoachalasia, in contrast with the more gradual onset in primary achalasia. Our report documents radiographically the progression within a few months from a normal-diameter esophagus to a very dilated, poorly functioning esophagus. We know of no similar report. Botulinum toxin injection has been reported effective in a few cases.1

References

1. Katzka, D.A., Farrugia, G., Arora, A.S., et al. Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:331-6.

2. Liu, W., Fackler, W., Rice, T.W., et al. The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia (A clinicopathological study of 13 cases of a rare entity). Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:784-8.

3. Gockel, J., Eckardt, V.F., Scmitt, T., et al. Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:378-85.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By William R. Brown, MD, and Elizabeth K. Dee, MD.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144:34, 252).

A 67-year-old woman with neuroendocrine small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), recurrent after chemotherapy and radiation therapy, complained of recent-onset dysphagia. She noticed regurgitation of liquids and some solid-food dysphagia. She had lost 20 pounds in the past 2 months. She had no past history of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms or esophagitis. Physical examination reveals no significant abnormalities, but she had had a peripheral sensory neuropathy that improved with treatment of her SCLC. Laboratory tests are unremarkable except for a positive Hu immunoglobulin (Ig)G serum anti-neuronal nuclear antibody test – an antibody that is associated with SCLC.

Clinical Challenges - March 2017: Gastrocardiac fistula with active bleeding

What's Your Diagnosis?

The Diagnosis

Answer: Gastrocardiac fistula with active bleeding

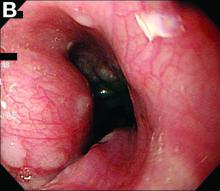

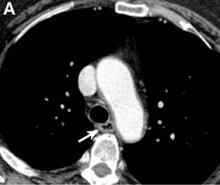

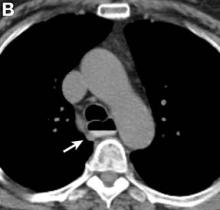

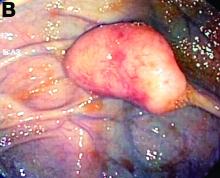

Active bleeding from a fistula between the right ventricle and reconstructed gastric conduit was identified after opening the gastric conduit (Figure B, black arrow). The surgeon decided to resect the gastric tube, create an esophagotomy and

Only seven cases of fistula between postesophagectomy gastric conduits and cardiac chambers, including this case, have been reported in English literature. The disease mortality rate is as high as 60%.1 Several predisposing risk factors exist for gastrocardiac fistula, including malignancy, radiation, ischemia, and peptic ulcer disease.1 We surmised that the previous pericardiectomy was the predisposing factor in this case.

Fistula rarely develops between the upper gastrointestinal tract and adjacent structures, including the trachea, bronchi, pleura, aorta, pericardium, and heart.2,3 The symptoms differ depending on the location of the fistula, and recurrent bronchopneumonia, pleuritis, mediastinitis, pericarditis, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding may be present. Because of the high mortality rate, physicians should be alert to these fatal fistula. If fistula is suspected, a contrast radiological study and direct endoscopic visualization can be employed to establish a diagnosis.

Gastrocardiac fistula is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The majority of diagnoses were made at autopsy. Only aggressive and emergent operative intervention can offer patients a chance of survival because they tend to deteriorate rapidly.1 This case of gastrocardiac fistula occurred after esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction and a pericardiectomy. Immediate surgery is required for life-threatening upper gastrointestinal bleeding if gastrocardiac fistula is suspected. Patient survival is likely after immediate operation.

References

1. Pentiak, P., Seder, C.W., Chmielewski, G.W., et al. Benign post-esophagectomy gastrocardiac fistula. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;13(4):447-9.

2. Schouten van der Velden, A.P., Ruers, T.J., Bonenkamp, J.J. A cardiogastric fistula after gastric tube interposition (A case report and review of literature). J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(1):79-82.

3. Rana, Z.A., Hosmane, V.R., Rana, N.R., et al. Gastro-right ventricular fistula: a deadly complication of a gastric pull-through. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(1):297-9.

The Diagnosis

Answer: Gastrocardiac fistula with active bleeding

Active bleeding from a fistula between the right ventricle and reconstructed gastric conduit was identified after opening the gastric conduit (Figure B, black arrow). The surgeon decided to resect the gastric tube, create an esophagotomy and

Only seven cases of fistula between postesophagectomy gastric conduits and cardiac chambers, including this case, have been reported in English literature. The disease mortality rate is as high as 60%.1 Several predisposing risk factors exist for gastrocardiac fistula, including malignancy, radiation, ischemia, and peptic ulcer disease.1 We surmised that the previous pericardiectomy was the predisposing factor in this case.

Fistula rarely develops between the upper gastrointestinal tract and adjacent structures, including the trachea, bronchi, pleura, aorta, pericardium, and heart.2,3 The symptoms differ depending on the location of the fistula, and recurrent bronchopneumonia, pleuritis, mediastinitis, pericarditis, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding may be present. Because of the high mortality rate, physicians should be alert to these fatal fistula. If fistula is suspected, a contrast radiological study and direct endoscopic visualization can be employed to establish a diagnosis.

Gastrocardiac fistula is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The majority of diagnoses were made at autopsy. Only aggressive and emergent operative intervention can offer patients a chance of survival because they tend to deteriorate rapidly.1 This case of gastrocardiac fistula occurred after esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction and a pericardiectomy. Immediate surgery is required for life-threatening upper gastrointestinal bleeding if gastrocardiac fistula is suspected. Patient survival is likely after immediate operation.

References

1. Pentiak, P., Seder, C.W., Chmielewski, G.W., et al. Benign post-esophagectomy gastrocardiac fistula. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;13(4):447-9.

2. Schouten van der Velden, A.P., Ruers, T.J., Bonenkamp, J.J. A cardiogastric fistula after gastric tube interposition (A case report and review of literature). J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(1):79-82.

3. Rana, Z.A., Hosmane, V.R., Rana, N.R., et al. Gastro-right ventricular fistula: a deadly complication of a gastric pull-through. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(1):297-9.

The Diagnosis

Answer: Gastrocardiac fistula with active bleeding

Active bleeding from a fistula between the right ventricle and reconstructed gastric conduit was identified after opening the gastric conduit (Figure B, black arrow). The surgeon decided to resect the gastric tube, create an esophagotomy and

Only seven cases of fistula between postesophagectomy gastric conduits and cardiac chambers, including this case, have been reported in English literature. The disease mortality rate is as high as 60%.1 Several predisposing risk factors exist for gastrocardiac fistula, including malignancy, radiation, ischemia, and peptic ulcer disease.1 We surmised that the previous pericardiectomy was the predisposing factor in this case.

Fistula rarely develops between the upper gastrointestinal tract and adjacent structures, including the trachea, bronchi, pleura, aorta, pericardium, and heart.2,3 The symptoms differ depending on the location of the fistula, and recurrent bronchopneumonia, pleuritis, mediastinitis, pericarditis, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding may be present. Because of the high mortality rate, physicians should be alert to these fatal fistula. If fistula is suspected, a contrast radiological study and direct endoscopic visualization can be employed to establish a diagnosis.

Gastrocardiac fistula is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The majority of diagnoses were made at autopsy. Only aggressive and emergent operative intervention can offer patients a chance of survival because they tend to deteriorate rapidly.1 This case of gastrocardiac fistula occurred after esophagectomy with gastric conduit reconstruction and a pericardiectomy. Immediate surgery is required for life-threatening upper gastrointestinal bleeding if gastrocardiac fistula is suspected. Patient survival is likely after immediate operation.

References

1. Pentiak, P., Seder, C.W., Chmielewski, G.W., et al. Benign post-esophagectomy gastrocardiac fistula. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;13(4):447-9.

2. Schouten van der Velden, A.P., Ruers, T.J., Bonenkamp, J.J. A cardiogastric fistula after gastric tube interposition (A case report and review of literature). J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(1):79-82.

3. Rana, Z.A., Hosmane, V.R., Rana, N.R., et al. Gastro-right ventricular fistula: a deadly complication of a gastric pull-through. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(1):297-9.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By Chih-Ming Lin, PhD, Yang-Yuan Chen, MD, and Hsin-Yuan Fang, MD.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144:31,251-2).

Clinical Challenges - February 2017: So-called carcinosarcoma of the esophagus

What's Your Diagnosis?

The Diagnosis

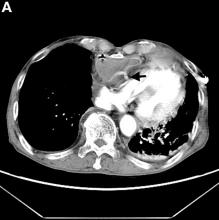

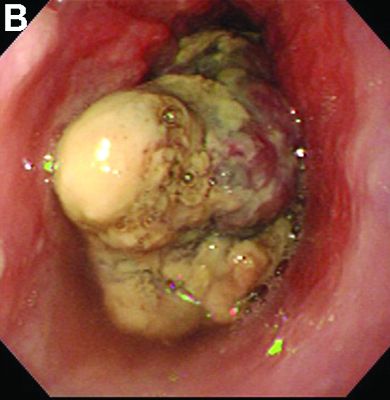

Carcinosarcoma is a rare malignant entity, representing less than 2% of all esophageal neoplasms. It usually shows a bulky appearance of an intraluminal polypoid lesion owing to predominant sarcomatous development with little stromal proliferation.

References

1. Hung J.J., Li A.F., Liu J.S., et al. Esophageal carcinosarcoma with basaloid squamous cell carcinoma and osteosarcoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85[3]:1102-4.

2. Madan A.K., Long A.E., Weldon C.B., et al. Esophageal carcinosarcoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5[4]:414-7.

The Diagnosis

Carcinosarcoma is a rare malignant entity, representing less than 2% of all esophageal neoplasms. It usually shows a bulky appearance of an intraluminal polypoid lesion owing to predominant sarcomatous development with little stromal proliferation.

References

1. Hung J.J., Li A.F., Liu J.S., et al. Esophageal carcinosarcoma with basaloid squamous cell carcinoma and osteosarcoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85[3]:1102-4.

2. Madan A.K., Long A.E., Weldon C.B., et al. Esophageal carcinosarcoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5[4]:414-7.

The Diagnosis

Carcinosarcoma is a rare malignant entity, representing less than 2% of all esophageal neoplasms. It usually shows a bulky appearance of an intraluminal polypoid lesion owing to predominant sarcomatous development with little stromal proliferation.

References

1. Hung J.J., Li A.F., Liu J.S., et al. Esophageal carcinosarcoma with basaloid squamous cell carcinoma and osteosarcoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85[3]:1102-4.

2. Madan A.K., Long A.E., Weldon C.B., et al. Esophageal carcinosarcoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5[4]:414-7.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By Kensuke Adachi, MD, PhD, and Kazuaki Enatsu, MD.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2013;144[1]:32, 251).

Clinical Challenges - January 2017

What’s your diagnosis?

The diagnosis

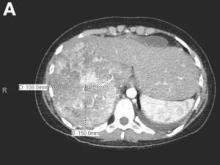

The radiographic and pathologic findings and the patient’s clinical presentation were most consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, which are manifestations of IgG4-related disease. IgG4-related disease is a fibroinflammatory condition that has been described in almost every organ system. Elevated serum IgG4 levels suggest this diagnosis, but many times remain normal.1,2 Therefore, a strong clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy of the affected tissue, which will show a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate organized in a matted and irregularly whorled pattern.2,3 Making a diagnosis requires immunohistochemical confirmation with IgG4 immunostaining of plasma cells.

The patient was started on prednisone followed by azathioprine and experienced a rapid and sustained clinical and biochemical response even after stopping immunosuppressive therapy. After treatment, repeat imaging studies were performed, which showed dramatic improvement in the above-mentioned abnormalities. Abdominal CT showed a decrease in size of the pancreatic head (Figure C) and repeat cholangiogram showed resolution of biliary stenoses (Figure D).

References

1. Oseini, A.M., Chaiteerakij, R., Shire, A.M., et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940-8.

2. Takuma, K., Kamisawa, T., Gopalakrishna, R., et al. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1015-20.

3. Stone, J.H., Zen, Y., Deshpande, V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539-51.

The diagnosis

The radiographic and pathologic findings and the patient’s clinical presentation were most consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, which are manifestations of IgG4-related disease. IgG4-related disease is a fibroinflammatory condition that has been described in almost every organ system. Elevated serum IgG4 levels suggest this diagnosis, but many times remain normal.1,2 Therefore, a strong clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy of the affected tissue, which will show a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate organized in a matted and irregularly whorled pattern.2,3 Making a diagnosis requires immunohistochemical confirmation with IgG4 immunostaining of plasma cells.

The patient was started on prednisone followed by azathioprine and experienced a rapid and sustained clinical and biochemical response even after stopping immunosuppressive therapy. After treatment, repeat imaging studies were performed, which showed dramatic improvement in the above-mentioned abnormalities. Abdominal CT showed a decrease in size of the pancreatic head (Figure C) and repeat cholangiogram showed resolution of biliary stenoses (Figure D).

References

1. Oseini, A.M., Chaiteerakij, R., Shire, A.M., et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940-8.

2. Takuma, K., Kamisawa, T., Gopalakrishna, R., et al. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1015-20.

3. Stone, J.H., Zen, Y., Deshpande, V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539-51.

The diagnosis

The radiographic and pathologic findings and the patient’s clinical presentation were most consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, which are manifestations of IgG4-related disease. IgG4-related disease is a fibroinflammatory condition that has been described in almost every organ system. Elevated serum IgG4 levels suggest this diagnosis, but many times remain normal.1,2 Therefore, a strong clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy of the affected tissue, which will show a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate organized in a matted and irregularly whorled pattern.2,3 Making a diagnosis requires immunohistochemical confirmation with IgG4 immunostaining of plasma cells.

The patient was started on prednisone followed by azathioprine and experienced a rapid and sustained clinical and biochemical response even after stopping immunosuppressive therapy. After treatment, repeat imaging studies were performed, which showed dramatic improvement in the above-mentioned abnormalities. Abdominal CT showed a decrease in size of the pancreatic head (Figure C) and repeat cholangiogram showed resolution of biliary stenoses (Figure D).

References

1. Oseini, A.M., Chaiteerakij, R., Shire, A.M., et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940-8.

2. Takuma, K., Kamisawa, T., Gopalakrishna, R., et al. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1015-20.

3. Stone, J.H., Zen, Y., Deshpande, V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539-51.

What’s your diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

By Victoria Gómez, MD, and Jaime Aranda-Michel, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012 Dec;143[6]:1441, 1694).

A 65-year-old woman was evaluated for recurrent painless jaundice. Prior investigations at an outside institution included an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography that showed a stricture in the distal common bile duct with a negative cytology for malignant cells. She underwent laparotomy, during which a pancreatic head mass was found and biopsies revealed no malignancy. A palliative cholecystojejunostomy with gastroenterostomy was performed. Postoperatively, the jaundice improved but she had epigastric pain, persistent nausea, anorexia, and a 20-pound weight loss. Two weeks later she developed recurrent jaundice, and a second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography demonstrated a hilar stricture. A presumptive diagnosis of multicentric cholangiocarcinoma was made and she was referred to hospice care. She then sought another opinion regarding her condition at our institution.

Clinical Challenges - December 2016

What is the most plausible diagnosis and what would be the next step?

The diagnosis

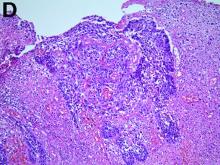

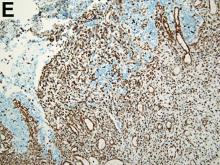

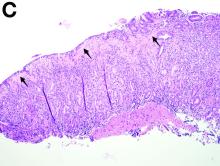

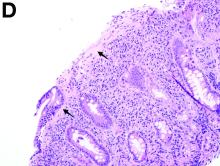

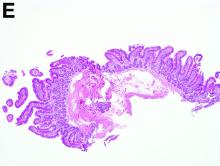

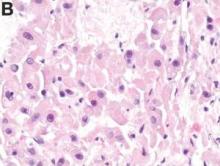

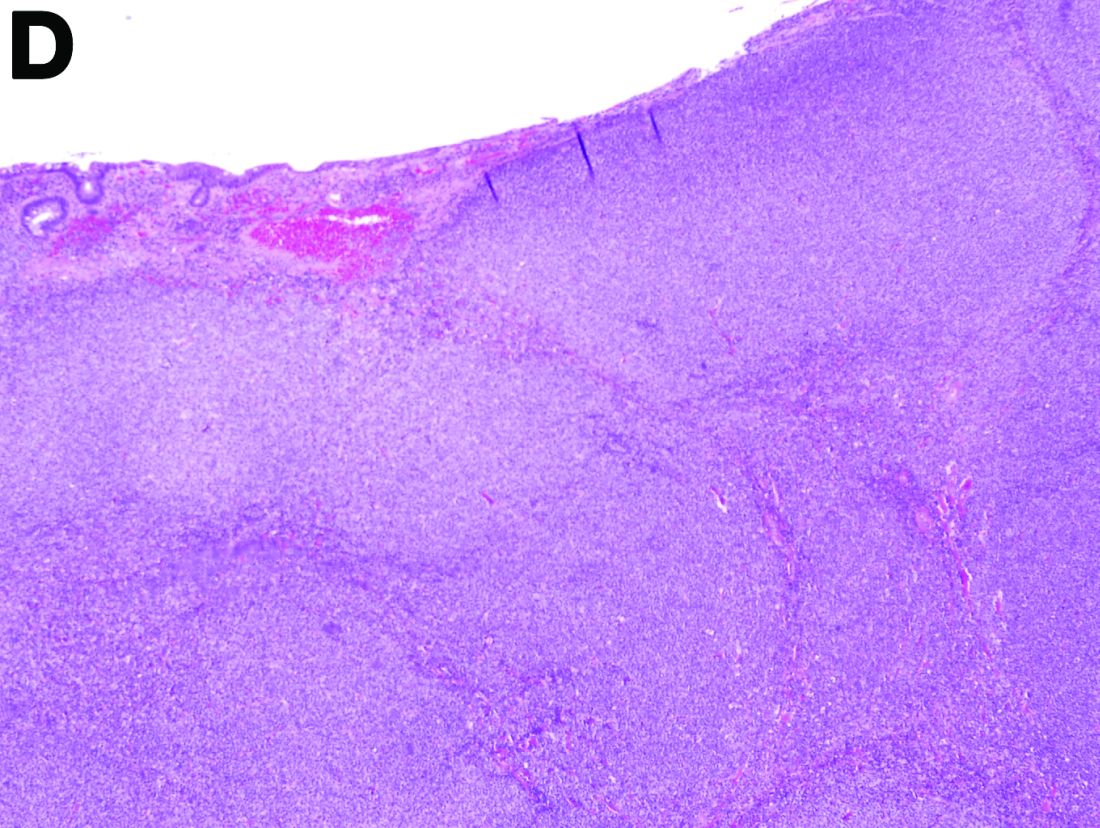

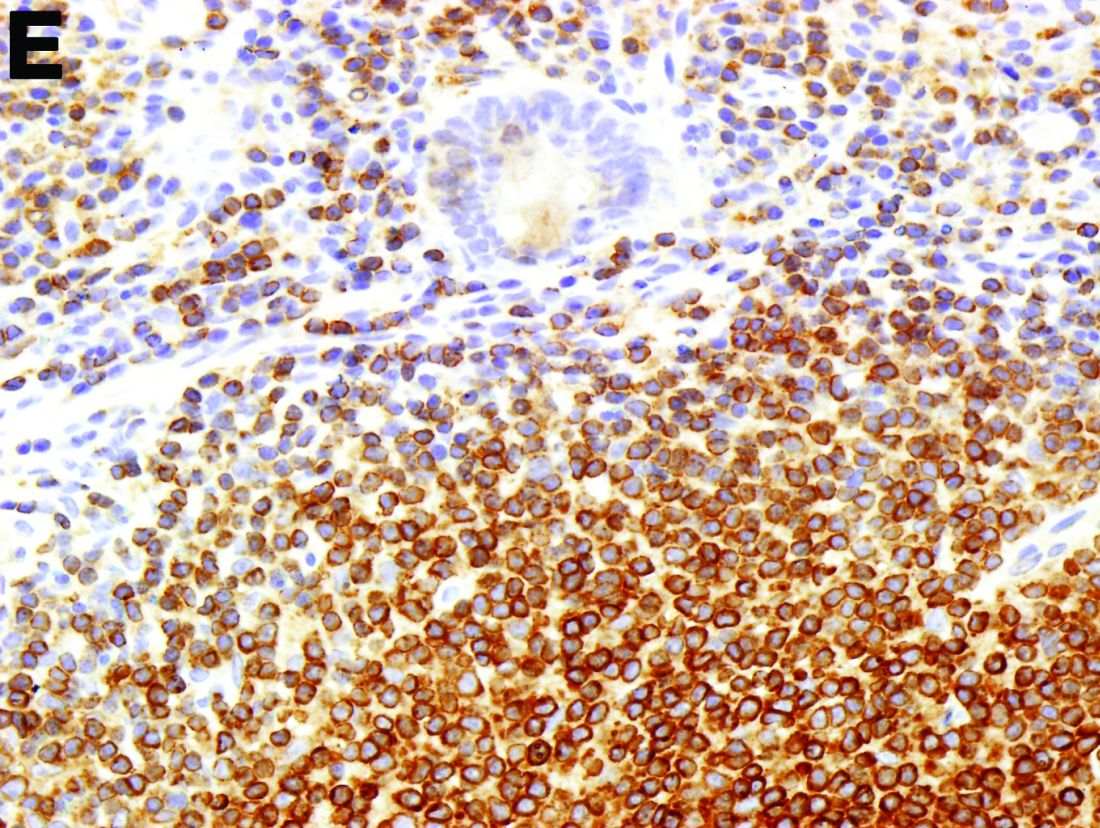

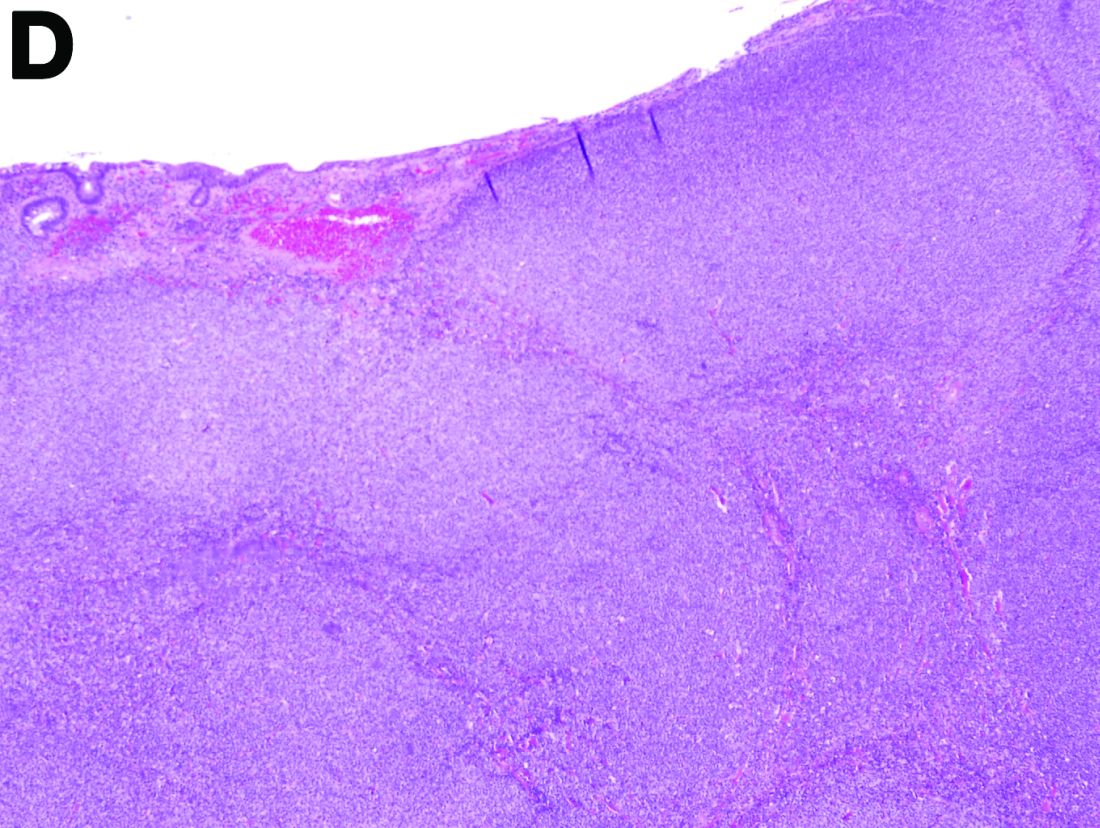

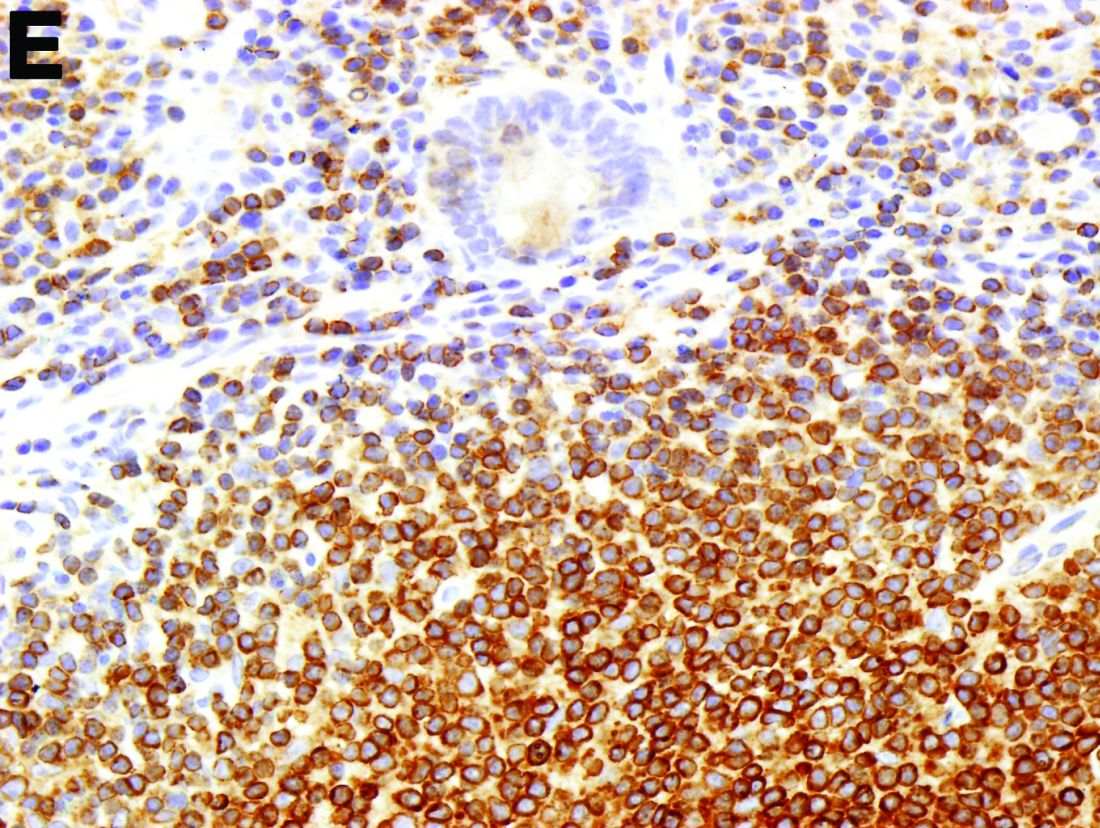

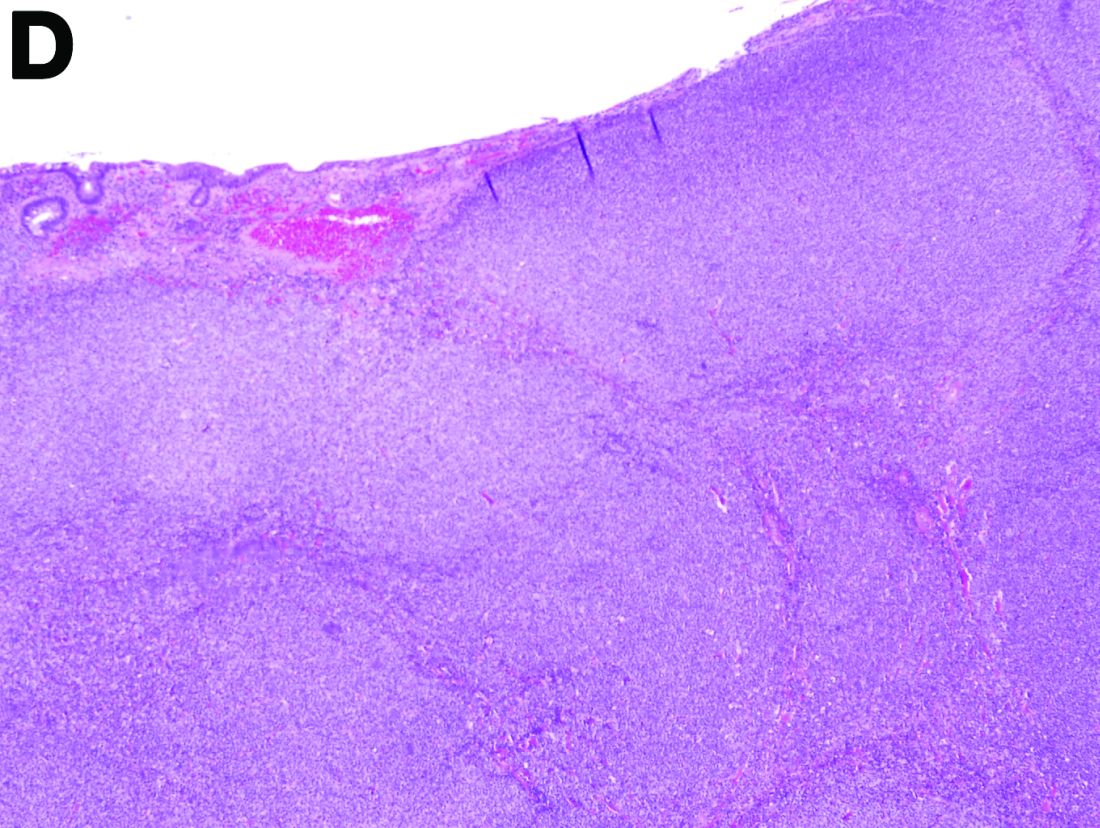

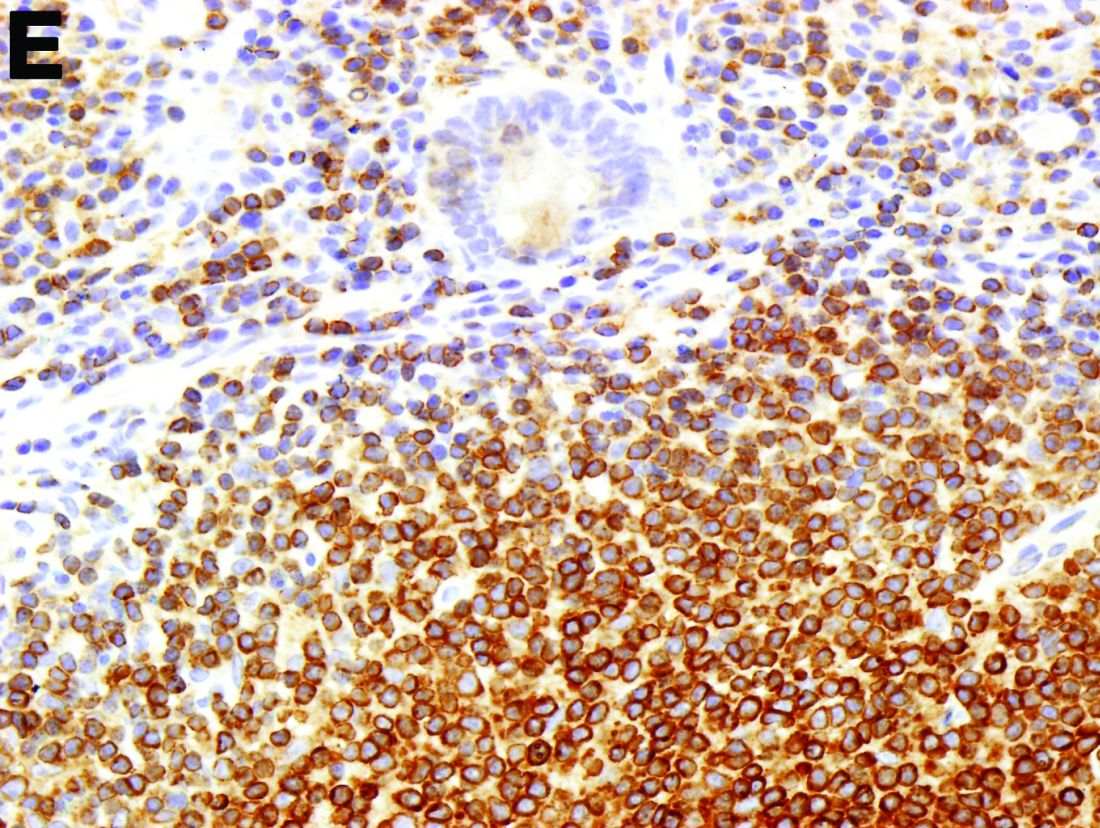

To clarify the diagnosis, endoscopic resection of the smaller lesion was performed and deeper biopsies of the other lesions were taken. Histology revealed lymphoid, centroblast, and centrocyte-like cell proliferation with follicular pattern (Figure D). Immunohistochemically, the follicles stained for bcl-6, CD20, and bcl-2 (Figure E), but not CD3, CD5, CD10, or cyclin D1.

Malignant lymphomas of the colon represent about 0.2% of all colonic neoplasms and most frequently are diffuse large B-cell, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, and mantle cell lymphomas.2 This phenotypic presentation, as multiple lymphomatous polyposis, has been reported in colon follicular lymphomas but is more typical of mantle cell lymphoma.3 Treatment usually consists of chemotherapy containing rituximab (anti-CD20) and should be decided on a case-by-case basis owing to possible relapse and the often indolent course.1

References

1. Damaj, G., Verkarre, V., Delmer, A. et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: A study of 25 cases and a literature review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:623-9.

2. Muller-Hermelink, H.K., Chott, A., Gascoyne, R.D. et al. B-cell lymphoma of the colon and rectum. In: S.R. Hamilton, L.A. Asltonen, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press;2001:139-41.

3. Hiraide, T., Shoji, T., Higashi, Y. et al. Extranodal multiple polypoid follicular lymphoma of the sigmoid colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(1):182-4.

The diagnosis

To clarify the diagnosis, endoscopic resection of the smaller lesion was performed and deeper biopsies of the other lesions were taken. Histology revealed lymphoid, centroblast, and centrocyte-like cell proliferation with follicular pattern (Figure D). Immunohistochemically, the follicles stained for bcl-6, CD20, and bcl-2 (Figure E), but not CD3, CD5, CD10, or cyclin D1.

Malignant lymphomas of the colon represent about 0.2% of all colonic neoplasms and most frequently are diffuse large B-cell, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, and mantle cell lymphomas.2 This phenotypic presentation, as multiple lymphomatous polyposis, has been reported in colon follicular lymphomas but is more typical of mantle cell lymphoma.3 Treatment usually consists of chemotherapy containing rituximab (anti-CD20) and should be decided on a case-by-case basis owing to possible relapse and the often indolent course.1

References

1. Damaj, G., Verkarre, V., Delmer, A. et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: A study of 25 cases and a literature review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:623-9.

2. Muller-Hermelink, H.K., Chott, A., Gascoyne, R.D. et al. B-cell lymphoma of the colon and rectum. In: S.R. Hamilton, L.A. Asltonen, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press;2001:139-41.

3. Hiraide, T., Shoji, T., Higashi, Y. et al. Extranodal multiple polypoid follicular lymphoma of the sigmoid colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(1):182-4.

The diagnosis

To clarify the diagnosis, endoscopic resection of the smaller lesion was performed and deeper biopsies of the other lesions were taken. Histology revealed lymphoid, centroblast, and centrocyte-like cell proliferation with follicular pattern (Figure D). Immunohistochemically, the follicles stained for bcl-6, CD20, and bcl-2 (Figure E), but not CD3, CD5, CD10, or cyclin D1.

Malignant lymphomas of the colon represent about 0.2% of all colonic neoplasms and most frequently are diffuse large B-cell, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, and mantle cell lymphomas.2 This phenotypic presentation, as multiple lymphomatous polyposis, has been reported in colon follicular lymphomas but is more typical of mantle cell lymphoma.3 Treatment usually consists of chemotherapy containing rituximab (anti-CD20) and should be decided on a case-by-case basis owing to possible relapse and the often indolent course.1

References

1. Damaj, G., Verkarre, V., Delmer, A. et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: A study of 25 cases and a literature review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:623-9.

2. Muller-Hermelink, H.K., Chott, A., Gascoyne, R.D. et al. B-cell lymphoma of the colon and rectum. In: S.R. Hamilton, L.A. Asltonen, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press;2001:139-41.

3. Hiraide, T., Shoji, T., Higashi, Y. et al. Extranodal multiple polypoid follicular lymphoma of the sigmoid colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(1):182-4.

What is the most plausible diagnosis and what would be the next step?

What is the most plausible diagnosis and what would be the next step?

What’s your diagnosis?

By Aníbal Ferreira, MD, PhD , Raquel Gonçalves, MD, and Carla Rolanda, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012 Dec;143[6]:1440, 1693-4).

An asymptomatic, 74-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes was referred for endoscopic colorectal cancer screening. Colonoscopy revealed a 30-mm, polypoid, firm lesion in the transverse colon (Figure A), a 20-mm similar lesion in the cecum (Figure B),

Clinical Challenges - November 2016

What’s your diagnosis?

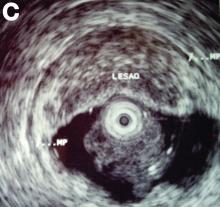

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page X: Collagenous gastritis and collagenous sprue

Recent studies have also shown the importance of obtaining at least 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb to avoid missing the diagnosis of celiac disease. In 126 patients with newly established celiac disease and 85 patients with a previous diagnosis on a gluten-free diet presenting for reevaluation, villous atrophy was limited to the duodenal bulb in 9% and 14% of cases, respectively.3

References

1. Brain, O., Rajaguru, C., Warren, B. et al. Collagenous gastritis: reports and systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1419-24.

2. Gopal, P., McKenna, B.J. The collagenous gastroenteritides: similarities and differences. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1485-9.

3. Evans, K.E., Aziz, I., Cross, S.S. et al. A prospective study of duodenal bulb biopsy in newly diagnosed and established adult celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1837-742.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page X: Collagenous gastritis and collagenous sprue

Recent studies have also shown the importance of obtaining at least 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb to avoid missing the diagnosis of celiac disease. In 126 patients with newly established celiac disease and 85 patients with a previous diagnosis on a gluten-free diet presenting for reevaluation, villous atrophy was limited to the duodenal bulb in 9% and 14% of cases, respectively.3

References

1. Brain, O., Rajaguru, C., Warren, B. et al. Collagenous gastritis: reports and systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1419-24.

2. Gopal, P., McKenna, B.J. The collagenous gastroenteritides: similarities and differences. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1485-9.

3. Evans, K.E., Aziz, I., Cross, S.S. et al. A prospective study of duodenal bulb biopsy in newly diagnosed and established adult celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1837-742.

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page X: Collagenous gastritis and collagenous sprue

Recent studies have also shown the importance of obtaining at least 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb to avoid missing the diagnosis of celiac disease. In 126 patients with newly established celiac disease and 85 patients with a previous diagnosis on a gluten-free diet presenting for reevaluation, villous atrophy was limited to the duodenal bulb in 9% and 14% of cases, respectively.3

References

1. Brain, O., Rajaguru, C., Warren, B. et al. Collagenous gastritis: reports and systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1419-24.

2. Gopal, P., McKenna, B.J. The collagenous gastroenteritides: similarities and differences. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1485-9.

3. Evans, K.E., Aziz, I., Cross, S.S. et al. A prospective study of duodenal bulb biopsy in newly diagnosed and established adult celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1837-742.

What’s your diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

By Benjamin Kloesel, MD, Vishal S. Chandan, MD, and Glenn L. Alexander, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012;143:1439, 1692).

A 30-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypothyroidism presents for evaluation of epigastric discomfort, nausea without emesis, abdominal bloating, and watery, nonbloody diarrhea for 5 months. This was associated with a 15-pound weight loss. Complete blood count, liver function tests, thyroid-stimulating hormone, immunoglobulin (Ig) levels, and IgG/IgA tissue transglutaminase (tTG) were within normal limits. Stool studies for bacterial pathogens, Giardia, Clostridium difficile toxin, and ova/parasites were negative.

Clinical Challenges - October 2016: Boerhaave’s syndrome (spontaneous rupture of the esophagus)

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

Gastrografin swallow (Figure C) demonstrated rupture of the distal esophagus, with leakage of gastrografin into the mediastinum (arrow). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy confirmed rupture of the left posterolateral wall of the distal esophagus consistent with Boerhaave’s syndrome (Figure D), and a self-expanding covered metal stent was placed.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics and nasogastric feeding were commenced, and the left pleural effusion drained with a tube thoracostomy. Unfortunately, despite initial improvement, the patient subsequently deteriorated and died 30 days after admission.

Boerhaave’s is a rare clinical entity defined as spontaneous esophageal rupture, excluding perforations resulting from foreign bodies or iatrogenic instrumentation.

Mackler’s triad of vomiting, lower chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema is the classical presentation but is seen in only a minority of cases; thus, diagnostic errors are common.2 Importantly, the chest radiograph is almost always abnormal, with pleural effusions or pneumomediastinum often seen.3 Surgical repair is the definitive treatment, but in patients considered unfit for surgery, conservative or endoscopic management is advocated. Mortality remains greater than 30%, and rises sharply if diagnosis is delayed,2 emphasizing the importance of awareness of this unusual diagnosis.

References

1. Lucendo, A.J., Fringal-Ruiz, A.B., Rodriguez, B. Boerhaave’s syndrome as the primary manifestation of adult eosinophilic esophagitis. (Two case reports and a review of the literature.) Dis Esophagus. 2011 Feb;24:E11-5.

2. Brauer, R.B., Liebermann-Meffert, D., Stein, H.J., et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome: Analysis of the literature and report of 18 new cases. Dis Esophagus. 1997 Jan;10:64-8.

3. Pate, J.W., Walker, W.A., Cole, F.H. Jr, et al. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: a 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989 May;47:689-92.

The diagnosis

Gastrografin swallow (Figure C) demonstrated rupture of the distal esophagus, with leakage of gastrografin into the mediastinum (arrow). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy confirmed rupture of the left posterolateral wall of the distal esophagus consistent with Boerhaave’s syndrome (Figure D), and a self-expanding covered metal stent was placed.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics and nasogastric feeding were commenced, and the left pleural effusion drained with a tube thoracostomy. Unfortunately, despite initial improvement, the patient subsequently deteriorated and died 30 days after admission.

Boerhaave’s is a rare clinical entity defined as spontaneous esophageal rupture, excluding perforations resulting from foreign bodies or iatrogenic instrumentation.

Mackler’s triad of vomiting, lower chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema is the classical presentation but is seen in only a minority of cases; thus, diagnostic errors are common.2 Importantly, the chest radiograph is almost always abnormal, with pleural effusions or pneumomediastinum often seen.3 Surgical repair is the definitive treatment, but in patients considered unfit for surgery, conservative or endoscopic management is advocated. Mortality remains greater than 30%, and rises sharply if diagnosis is delayed,2 emphasizing the importance of awareness of this unusual diagnosis.

References

1. Lucendo, A.J., Fringal-Ruiz, A.B., Rodriguez, B. Boerhaave’s syndrome as the primary manifestation of adult eosinophilic esophagitis. (Two case reports and a review of the literature.) Dis Esophagus. 2011 Feb;24:E11-5.

2. Brauer, R.B., Liebermann-Meffert, D., Stein, H.J., et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome: Analysis of the literature and report of 18 new cases. Dis Esophagus. 1997 Jan;10:64-8.

3. Pate, J.W., Walker, W.A., Cole, F.H. Jr, et al. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: a 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989 May;47:689-92.

The diagnosis

Gastrografin swallow (Figure C) demonstrated rupture of the distal esophagus, with leakage of gastrografin into the mediastinum (arrow). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy confirmed rupture of the left posterolateral wall of the distal esophagus consistent with Boerhaave’s syndrome (Figure D), and a self-expanding covered metal stent was placed.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics and nasogastric feeding were commenced, and the left pleural effusion drained with a tube thoracostomy. Unfortunately, despite initial improvement, the patient subsequently deteriorated and died 30 days after admission.

Boerhaave’s is a rare clinical entity defined as spontaneous esophageal rupture, excluding perforations resulting from foreign bodies or iatrogenic instrumentation.

Mackler’s triad of vomiting, lower chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema is the classical presentation but is seen in only a minority of cases; thus, diagnostic errors are common.2 Importantly, the chest radiograph is almost always abnormal, with pleural effusions or pneumomediastinum often seen.3 Surgical repair is the definitive treatment, but in patients considered unfit for surgery, conservative or endoscopic management is advocated. Mortality remains greater than 30%, and rises sharply if diagnosis is delayed,2 emphasizing the importance of awareness of this unusual diagnosis.

References

1. Lucendo, A.J., Fringal-Ruiz, A.B., Rodriguez, B. Boerhaave’s syndrome as the primary manifestation of adult eosinophilic esophagitis. (Two case reports and a review of the literature.) Dis Esophagus. 2011 Feb;24:E11-5.

2. Brauer, R.B., Liebermann-Meffert, D., Stein, H.J., et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome: Analysis of the literature and report of 18 new cases. Dis Esophagus. 1997 Jan;10:64-8.

3. Pate, J.W., Walker, W.A., Cole, F.H. Jr, et al. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: a 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989 May;47:689-92.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By Thomas P. Chapman, MD, David A. Gorard, MBBS, MD, and Emily A. Johns, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012;143:1438, 1692).

An 84-year-old man presented to the emergency department with acute left-sided chest pain, after a recent diarrheal and vomiting illness. He had a background of severe Alzheimer’s dementia and was a resident in a care home. On arrival in the emergency department, he was unable to give a clear history and was distressed by the chest pain.

Clinical Challenges - September 2016: Fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

Histologic analysis was consistent with a fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient developed decerebrate posturing without cerebral edema on CT of the head. The patient was treated with mannitol, hyperventilation, and therapeutic hypothermia, as well as lactulose, rifaximin, hemodialysis, and “empiric” sodium benzoate/sodium phenylacetate (Ammonul, Ucyclyd Pharma, Scottsdale, Ariz.) for the possibility of a urea cycle disorder. In hopes of decreasing blood flow to the tumor, the patient underwent embolization of the right hepatic artery with no clinical improvement. Given the persistently elevated ammonia level, a work-up for an underlying urea cycle disorder was performed, revealing trace citrulline and increased urine orotic acids and uracil, suggesting an ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency. She was started on parenteral nutrition with arginine supplementation, after which her ammonia level normalized with subsequent improvement in her mental status.

Fibrolamellar-HCC is a rare, malignant, primary liver tumor predominantly affecting young adults with no underlying liver disease. This hypervascular tumor is radiographically characterized by a central scar.1 Most patients experience vague abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Fibrolamellar-HCC carries a better prognosis than HCC; in surgically resectable cases, the 5-year survival rates range between 37% and 76% vs. 12-14 months in nonresectable cases.2 Systemic chemotherapy has been used in case reports and the role of sorafenib remains unexplored and ill defined.

This is the second reported case of metastatic fibrolamellar-HCC with hyperammonemia.3 Although urea cycle disorders are more commonly diagnosed in newborns and infants, patients with partial enzyme deficiencies may present later in life and manifest in the setting of metabolic decompensation or stress. Our patient’s initial evaluation was consistent with a urea cycle deficiency, but OTC sequencing from the blood was negative. We hypothesize that the patient exhibited a “functional” OTC deficiency as a result of a combination of the massive tumor burden and portal vein thrombus, leading to a decreased expression of the OTC gene and insufficient enzyme production. The patient is doing well 3 months post resection and is being considered for a phase I clinical trial with a telomerase inhibitor, imetelstat.

References

1. Ichikawa, T., Federle, M.P., Grazioli, L., et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: Imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):352-61.

2. Ward, S.C. Waxman, S. Fibrolamellar carcinoma: A review with focus on genetics and comparison to other malignant primary liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31(1):61-70.

3. Sethi, S., Tageja, N., Singh, J., et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: A rare presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(6):522-4.

The diagnosis

Histologic analysis was consistent with a fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient developed decerebrate posturing without cerebral edema on CT of the head. The patient was treated with mannitol, hyperventilation, and therapeutic hypothermia, as well as lactulose, rifaximin, hemodialysis, and “empiric” sodium benzoate/sodium phenylacetate (Ammonul, Ucyclyd Pharma, Scottsdale, Ariz.) for the possibility of a urea cycle disorder. In hopes of decreasing blood flow to the tumor, the patient underwent embolization of the right hepatic artery with no clinical improvement. Given the persistently elevated ammonia level, a work-up for an underlying urea cycle disorder was performed, revealing trace citrulline and increased urine orotic acids and uracil, suggesting an ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency. She was started on parenteral nutrition with arginine supplementation, after which her ammonia level normalized with subsequent improvement in her mental status.

Fibrolamellar-HCC is a rare, malignant, primary liver tumor predominantly affecting young adults with no underlying liver disease. This hypervascular tumor is radiographically characterized by a central scar.1 Most patients experience vague abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Fibrolamellar-HCC carries a better prognosis than HCC; in surgically resectable cases, the 5-year survival rates range between 37% and 76% vs. 12-14 months in nonresectable cases.2 Systemic chemotherapy has been used in case reports and the role of sorafenib remains unexplored and ill defined.

This is the second reported case of metastatic fibrolamellar-HCC with hyperammonemia.3 Although urea cycle disorders are more commonly diagnosed in newborns and infants, patients with partial enzyme deficiencies may present later in life and manifest in the setting of metabolic decompensation or stress. Our patient’s initial evaluation was consistent with a urea cycle deficiency, but OTC sequencing from the blood was negative. We hypothesize that the patient exhibited a “functional” OTC deficiency as a result of a combination of the massive tumor burden and portal vein thrombus, leading to a decreased expression of the OTC gene and insufficient enzyme production. The patient is doing well 3 months post resection and is being considered for a phase I clinical trial with a telomerase inhibitor, imetelstat.

References

1. Ichikawa, T., Federle, M.P., Grazioli, L., et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: Imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):352-61.

2. Ward, S.C. Waxman, S. Fibrolamellar carcinoma: A review with focus on genetics and comparison to other malignant primary liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31(1):61-70.

3. Sethi, S., Tageja, N., Singh, J., et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: A rare presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(6):522-4.

The diagnosis

Histologic analysis was consistent with a fibrolamellar-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient developed decerebrate posturing without cerebral edema on CT of the head. The patient was treated with mannitol, hyperventilation, and therapeutic hypothermia, as well as lactulose, rifaximin, hemodialysis, and “empiric” sodium benzoate/sodium phenylacetate (Ammonul, Ucyclyd Pharma, Scottsdale, Ariz.) for the possibility of a urea cycle disorder. In hopes of decreasing blood flow to the tumor, the patient underwent embolization of the right hepatic artery with no clinical improvement. Given the persistently elevated ammonia level, a work-up for an underlying urea cycle disorder was performed, revealing trace citrulline and increased urine orotic acids and uracil, suggesting an ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency. She was started on parenteral nutrition with arginine supplementation, after which her ammonia level normalized with subsequent improvement in her mental status.

Fibrolamellar-HCC is a rare, malignant, primary liver tumor predominantly affecting young adults with no underlying liver disease. This hypervascular tumor is radiographically characterized by a central scar.1 Most patients experience vague abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue. Fibrolamellar-HCC carries a better prognosis than HCC; in surgically resectable cases, the 5-year survival rates range between 37% and 76% vs. 12-14 months in nonresectable cases.2 Systemic chemotherapy has been used in case reports and the role of sorafenib remains unexplored and ill defined.

This is the second reported case of metastatic fibrolamellar-HCC with hyperammonemia.3 Although urea cycle disorders are more commonly diagnosed in newborns and infants, patients with partial enzyme deficiencies may present later in life and manifest in the setting of metabolic decompensation or stress. Our patient’s initial evaluation was consistent with a urea cycle deficiency, but OTC sequencing from the blood was negative. We hypothesize that the patient exhibited a “functional” OTC deficiency as a result of a combination of the massive tumor burden and portal vein thrombus, leading to a decreased expression of the OTC gene and insufficient enzyme production. The patient is doing well 3 months post resection and is being considered for a phase I clinical trial with a telomerase inhibitor, imetelstat.

References

1. Ichikawa, T., Federle, M.P., Grazioli, L., et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: Imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):352-61.

2. Ward, S.C. Waxman, S. Fibrolamellar carcinoma: A review with focus on genetics and comparison to other malignant primary liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31(1):61-70.

3. Sethi, S., Tageja, N., Singh, J., et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: A rare presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(6):522-4.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

By Jana G. Hashash, MD, Kavitha Thudi, MD, and Shahid M. Malik, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012;143[5]:1157, 1401-2).

An 18-year-old white woman with no significant medical history was in good health until 2 days before admission, when she developed nausea, vomiting, and confusion. She was awake but lethargic and disoriented with asterixis. The remainder of her neurologic examination was nonfocal.

Laboratory data revealed white blood cell count of 13,000/L, hemoglobin of 13 g, and a platelet count of 300,000/L. A serum venous ammonia level was 342 micromol/L (normal range, 9-33). A urine drug screen was negative, as were her serum acetaminophen and aminosalicylic acid levels. Infectious work-up was unrevealing. Work-up for underlying chronic liver disease, including viral hepatitis serologies, autoimmune serologies, ceruloplasmin level, alpha-1 antitrypsin level, as well as hemochromatosis gene testing, was negative. An electroencephalography revealed burst suppression but no seizure activity. A lumbar puncture was negative.

An abdominal contrast-enhanced CT revealed an 11 × 15-cm heterogeneous, hypervascular mass replacing the majority of the right hepatic lobe (Figure A), right portal vein thrombosis, an enlarged hypervascular portocaval node measuring 2.0 × 2.0 cm, and an 8-mm left lower lobe lung lesion concerning for metastatic disease. Her liver was mildly enlarged, but was noncirrhotic. There was no radiologic evidence of portal hypertension or varices. There was no evidence of extrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Serum tumor markers, including alpha-fetoprotein, were within normal limits (1 ng/mL).

What is the cause of this young patient’s acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Clinical Challenges - August 2016: Benign multicystic mesothelioma

What's Your Diagnosis?

The diagnosis

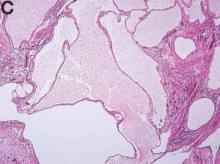

We present a case of benign multicystic mesothelioma with extensive involvement of the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a male patient. Benign multicystic mesothelioma is a rare tumor most frequently localized to the pelvic peritoneal surface. Patients are usually women of reproductive age without a history of asbestos exposure. The gross appearance is typically multiple translucent membranous cysts that are grouped together to form a mass or discontinuously studding the peritoneal surface. Microscopically, the cystic spaces are lined by mesothelial cells expressing markers such as calretinin. The major differential diagnosis is cystic lymphangioma, in which cystic spaces are lined by endothelial cells. Preoperative diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology has been described in the literature. Cytology shows monomorphous cells with mesothelial features in a clean background.1 The disease course is usually indolent, but local recurrence after operative intervention is common.2,3

References

1. Devaney, K., Kragel, P.J., Devaney, E.J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of multicystic mesothelioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992 Jan;8:68-72.

2. Ross, M.J., Welch, W.R., Scully, R.E. Multilocular peritoneal inclusion cysts (so-called cystic mesotheliomas). Cancer. 1989 Sep;64:1336-46.

3. Weiss, S.W. Tavassoli, F.A. Multicystic mesothelioma (An analysis of pathologic findings and biologic behavior in 37 cases). Am J Surg Pathol. 1988 Oct;12:737-46.

The diagnosis

We present a case of benign multicystic mesothelioma with extensive involvement of the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a male patient. Benign multicystic mesothelioma is a rare tumor most frequently localized to the pelvic peritoneal surface. Patients are usually women of reproductive age without a history of asbestos exposure. The gross appearance is typically multiple translucent membranous cysts that are grouped together to form a mass or discontinuously studding the peritoneal surface. Microscopically, the cystic spaces are lined by mesothelial cells expressing markers such as calretinin. The major differential diagnosis is cystic lymphangioma, in which cystic spaces are lined by endothelial cells. Preoperative diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology has been described in the literature. Cytology shows monomorphous cells with mesothelial features in a clean background.1 The disease course is usually indolent, but local recurrence after operative intervention is common.2,3

References

1. Devaney, K., Kragel, P.J., Devaney, E.J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of multicystic mesothelioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992 Jan;8:68-72.

2. Ross, M.J., Welch, W.R., Scully, R.E. Multilocular peritoneal inclusion cysts (so-called cystic mesotheliomas). Cancer. 1989 Sep;64:1336-46.

3. Weiss, S.W. Tavassoli, F.A. Multicystic mesothelioma (An analysis of pathologic findings and biologic behavior in 37 cases). Am J Surg Pathol. 1988 Oct;12:737-46.

The diagnosis

We present a case of benign multicystic mesothelioma with extensive involvement of the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a male patient. Benign multicystic mesothelioma is a rare tumor most frequently localized to the pelvic peritoneal surface. Patients are usually women of reproductive age without a history of asbestos exposure. The gross appearance is typically multiple translucent membranous cysts that are grouped together to form a mass or discontinuously studding the peritoneal surface. Microscopically, the cystic spaces are lined by mesothelial cells expressing markers such as calretinin. The major differential diagnosis is cystic lymphangioma, in which cystic spaces are lined by endothelial cells. Preoperative diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology has been described in the literature. Cytology shows monomorphous cells with mesothelial features in a clean background.1 The disease course is usually indolent, but local recurrence after operative intervention is common.2,3

References

1. Devaney, K., Kragel, P.J., Devaney, E.J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of multicystic mesothelioma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992 Jan;8:68-72.

2. Ross, M.J., Welch, W.R., Scully, R.E. Multilocular peritoneal inclusion cysts (so-called cystic mesotheliomas). Cancer. 1989 Sep;64:1336-46.

3. Weiss, S.W. Tavassoli, F.A. Multicystic mesothelioma (An analysis of pathologic findings and biologic behavior in 37 cases). Am J Surg Pathol. 1988 Oct;12:737-46.

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

What's Your Diagnosis?

BY SHAN-CHI YU, MD, CHIH-HORNG WU, MD, AND HSIN-YI HUANG, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012;143:1156, 1140).

The cystic lesions and appendix were resected under the clinical impression of pseudomyxoma peritonei.

There were multiple, thin-walled, cystic tumors containing clear fluid throughout the abdominal and pelvic cavities.

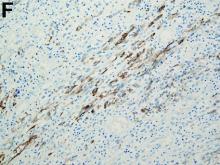

The cysts were lined by a single layer of flattened or cuboidal cells, which were positive for calretinin (Figures D) and negative for CD31 (an endothelial marker). A carcinoid tumor was incidentally found at the appendix.