User login

ABSTRACT

Objective: Promoting a culture of safety is a critical component of improving health care quality. Recognizing staff who stop the line for safety can positively impact the growth of a culture of safety. The purpose of this initiative was to demonstrate to staff the importance of speaking up for safety and being acknowledged for doing so.

Methods: Following a review of the literature on safety awards programs and their role in promoting a culture of safety in health care covering the period 2017 to 2020, a formal process was developed and implemented to disseminate safety awards to employees.

Results: During the initial 18 months of the initiative, a total of 59 awards were presented. The awards were well received by the recipients and other staff members. Within this period, adjustments were made to enhance the scope and reach of the program.

Conclusion: Recognizing staff behaviors that support a culture of safety is important for improving health care quality and employee engagement. Future research should focus on a formal evaluation of the impact of safety awards programs on patient safety outcomes.

Keywords: patient safety, culture of safety, incident reporting, near miss.

A key aspect of improving health care quality is promoting and sustaining a culture of safety in the workplace. Improving the quality of health care services and systems involves making informed choices regarding the types of strategies to implement.1 An essential aspect of supporting a safety culture is safety-event reporting. To approach the goal of zero harm, all safety events, whether they result in actual harm or are considered near misses, need to be reported. Near-miss events are errors that occur while care is being provided but are detected and corrected before harm reaches the patient.1-3 Near-miss reporting plays a critical role in helping to identify and correct weaknesses in health care delivery systems and processes.4 However, evidence shows that there are a multitude of barriers to the reporting of near-miss events, such as fear of punitive actions, additional workload, unsupportive work environments, a culture with poor psychological safety, knowledge deficit, and lack of recognition of staff who do report near misses.4-11

According to The Joint Commission (TJC), acknowledging health care team members who recognize and report unsafe conditions that provide insight for improving patient safety is a key method for promoting the reporting of near-miss events.6 As a result, some health care organizations and patient safety agencies have started to institute some form of recognition for their employees in the realm of safety.8-10 The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority offers exceptional guidance for creating a safety awards program to promote a culture of safety.12 Furthermore, TJC supports recognizing individuals and health care teams who identify and report near misses, or who have suggestions for initiatives to promote patient safety, with “good catch” awards. Individuals or teams working to promote and sustain a culture of safety should be recognized for their efforts. Acknowledging “good catches” to reward the identification, communication, and resolution of safety issues is an effective strategy for improving patient safety and health care quality.6,8

This quality improvement (QI) initiative was undertaken to demonstrate to staff that, in building an organizational culture of safety, it is important that staff be encouraged to speak up for safety and be acknowledged for doing so. If health care organizations want staff to be motivated to report near misses and improve safety and health care quality, the culture needs to shift from focusing on blame to incentivizing individuals and teams to speak up when they have concerns.8-10 Although deciding which safety actions are worthy of recognition can be challenging, recognizing all safe acts, regardless of how big or small they are perceived to be, is important. This QI initiative aimed to establish a tiered approach to recognize staff members for various categories of safety acts.

METHODS

A review of the literature from January 2017 to May 2020 for peer-reviewed publications regarding how other organizations implemented safety award programs to promote a culture of safety resulted in a dearth of evidence. This prompted us at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System to develop and implement a formal program to disseminate safety awards to employees.

Program Launch and Promotion

In 2020, our institution embarked on a journey to high reliability with the goal of approaching zero harm. As part of efforts to promote a culture of safety, the hospital’s High Reliability Organization (HRO) team worked to develop a safety awards recognition program. Prior to the launch, the hospital’s patient safety committee recognized staff members through the medical center safety event reporting system (the Joint Patient Safety Reporting system [JPSR]) or through direct communication with staff members on safety actions they were engaged in. JPSR is the Veterans Health Administration National Center for Patient Safety incident reporting system for reporting, tracking, and trending of patient incidents in a national database. The award consisted of a certificate presented by the patient safety committee chairpersons to the employee in front of their peers in their respective work area. Hospital leadership was not involved in the safety awards recognition program at that time. No nomination process existed prior to our QI launch.

Once the QI initiative was launched and marketed heavily at staff meetings, we started to receive nominations for actions that were truly exceptional, while many others were submitted for behaviors that were within the day-to-day scope of practice of the staff member. For those early nominations that did not meet criteria for an award, we thanked staff for their submissions with a gentle statement that their nomination did not meet the criteria for an award. After following this practice for a few weeks, we became concerned that if we did not acknowledge the staff who came forward to request recognition for their routine work that supported safety, we could risk losing their engagement in a culture of safety. As such, we decided to create 3 levels of awards to recognize behaviors that went above and beyond while also acknowledging staff for actions within their scope of practice. Additionally, hospital leadership wanted to ensure that all staff recognize that their safety efforts are valued by leadership and that that sense of value will hopefully contribute to a culture of safety over time.

Initially, the single award system was called the “Good Catch Award” to acknowledge staff who go above and beyond to speak up and take action when they have safety concerns. This particular recognition includes a certificate, an encased baseball card that has been personalized by including the staff member’s picture and safety event identified, a stress-release baseball, and a stick of Bazooka gum (similar to what used to come in baseball cards packs). The award is presented to employees in their work area by the HRO and patient safety teams and includes representatives from the executive leadership team (ELT). The safety event identified is described by an ELT member, and all items are presented to the employee. Participation by the leadership team communicates how much the work being done to promote a culture of safety and advance quality health care is appreciated. This action also encourages others in the organization to identify and report safety concerns.13

With the rollout of the QI initiative, the volume of nominations submitted quickly increased (eg, approximately 1 every 2 months before to 3 per month following implementation). Frequently, nominations were for actions believed to be within the scope of the employee’s responsibilities. Our institution’s leadership team quickly recognized that, as an organization, not diminishing the importance of the “Good Catch Award” was important. However, the

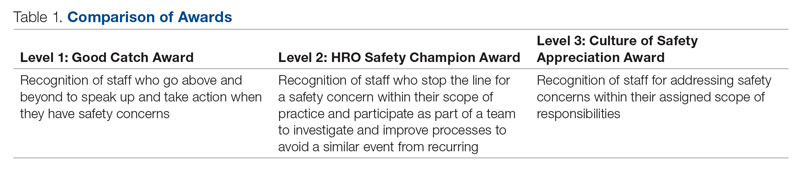

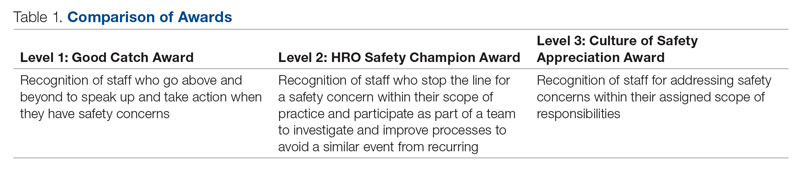

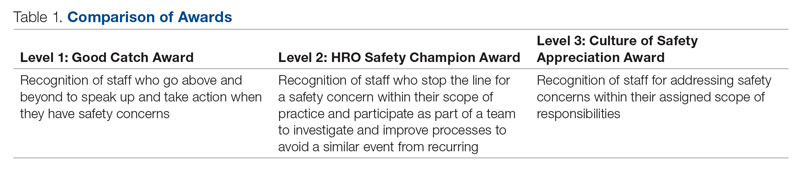

The original Good Catch Award was labelled as a Level 1 award. The Level 2 safety recognition award, named the HRO Safety Champion Award, is given to employees who stop the line for a safety concern within their scope of practice and also participate as part of a team to investigate and improve processes to avoid recurring safety concerns in the future. For the Level Two award, a certificate is presented to an employee by the hospital’s HRO lead, HRO physician champion, patient safety manager, immediate supervisor, and peers. With the Level 3 award, the Culture of Safety Appreciation Award, individuals are recognized for addressing safety concerns within their assigned scope of responsibilities. Recognition is bestowed by an email of appreciation sent to the employee, acknowledging their commitment to promoting a culture of safety and quality health care. The recipient’s direct supervisor and other hospital leaders are copied on the message.14 See Table 1 for a

Our institution’s HRO and patient safety teams utilized many additional venues to disseminate information regarding awardees and their actions. These included our monthly HRO newsletter, monthly safety forums, and biweekly Team Connecticut Healthcare system-wide huddles.

Nomination Process

Awards nominations are submitted via the hospital intranet homepage, where there is an “HRO Safety Award Nomination” icon. Once a staff member clicks the icon, a template opens asking for information, such as the reason for the nomination submission, and then walks them through the template using the CAR (C-context, A-actions, and R-results)15 format for describing the situation, identifying actions taken, and specifying the outcome of the action. Emails with award nominations can also be sent to the HRO lead, HRO champion, or Patient Safety Committee co-chairs. Calls for nominations are made at several venues attended by employees as well as supervisors. These include monthly safety forums, biweekly Team Connecticut Healthcare system-wide huddles, supervisory staff meetings, department and unit-based staff meetings, and many other formal and informal settings. This QI initiative has allowed us to capture potential awardees through several avenues, including self-nominations. All nominations are reviewed by a safety awards committee. Each committee member ranks the nomination as a Level 1, 2, or 3 award. For nominations where conflicting scores are obtained, the committee discusses the nomination together to resolve discrepancies.

Needed Resources

Material resources required for this QI initiative include certificate paper, plastic baseball card sleeves, stress-release baseballs, and Bazooka gum. The largest resource investment was the time needed to support the initiative. This included the time spent scheduling the Level 1 and 2 award presentations with staff and leadership. Time was also required to put the individual award packages together, which included printing the paper certificates, obtaining awardee pictures, placing them with their safety stories in a plastic baseball card sleeve, and arranging for the hospital photographer to take pictures of the awardees with their peers and leaders.

RESULTS

Prior to this QI initiative launch, 14 awards were given out over the preceding 2-year period. During the initial 18 months of the initiative (December 2020 to June 2022), 59 awards were presented (Level 1, n = 26; Level 2, n = 22; and Level 3, n = 11). Looking further into the Level 1 awards presented, 25 awardees worked in clinical roles and 1 in a nonclinical position (Table 2). The awardees represented multidisciplinary areas, including medical/surgical (med/surg) inpatient units, anesthesia, operating room, pharmacy, mental health clinics, surgical intensive care, specialty care clinics, and nutrition and food services. With the Level 2 awards, 18 clinical staff and 4 nonclinical staff received awards from the areas of med/surg inpatient, outpatient surgical suites, the medical center director’s office, radiology, pharmacy, primary care, facilities management, environmental management, infection prevention, and emergency services. All Level 3 awardees were from clinical areas, including primary care, hospital education, sterile processing, pharmacies, operating rooms, and med/surg inpatient units.

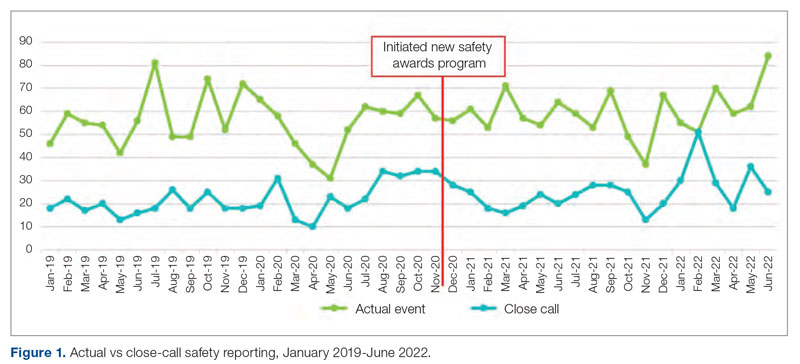

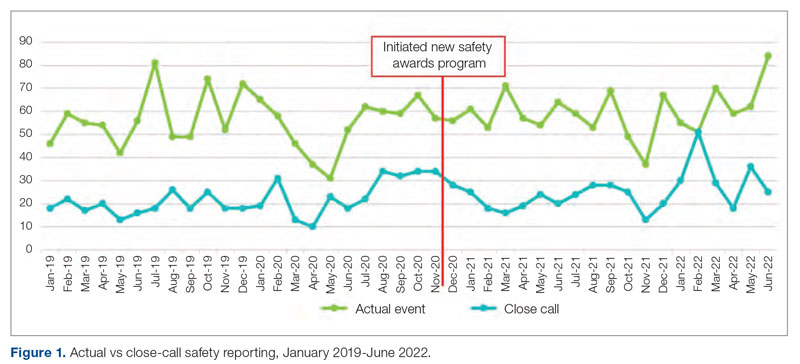

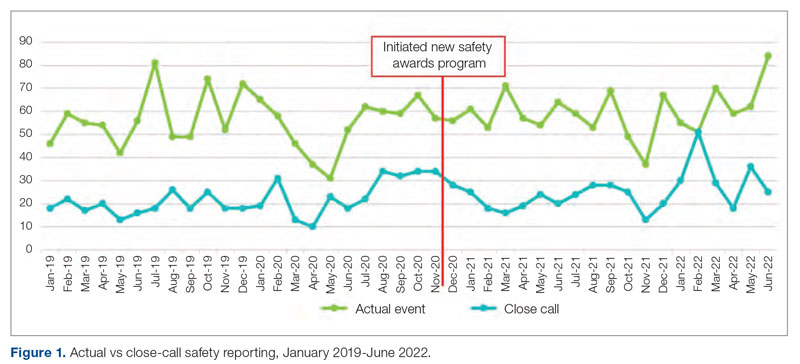

With the inception of this QI initiative, our organization has begun to see trends reflecting increased reporting of both actual and close-call events in JPSR (Figure 1).

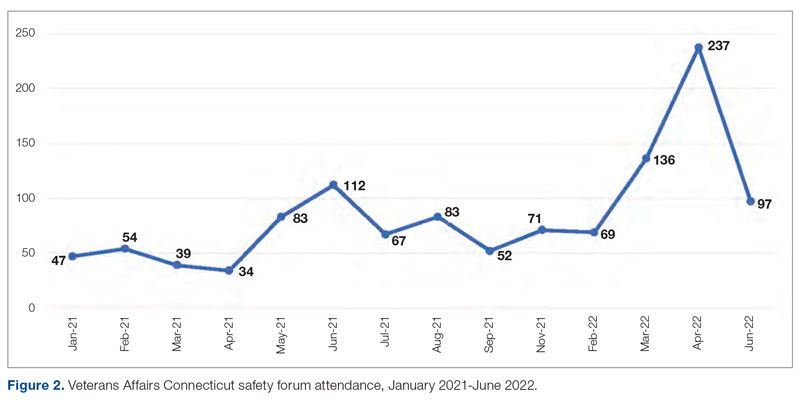

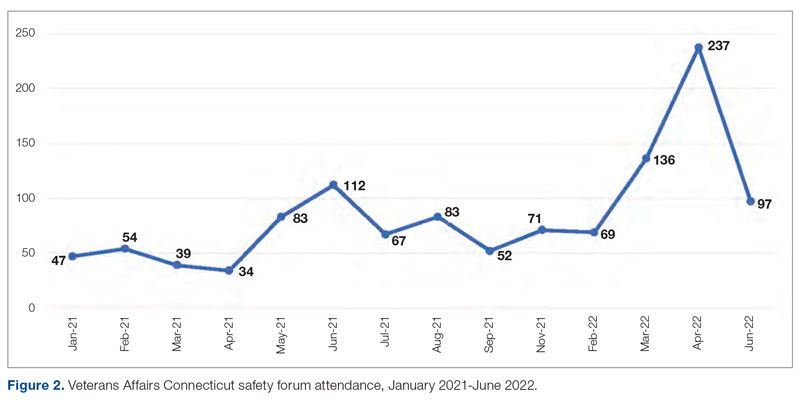

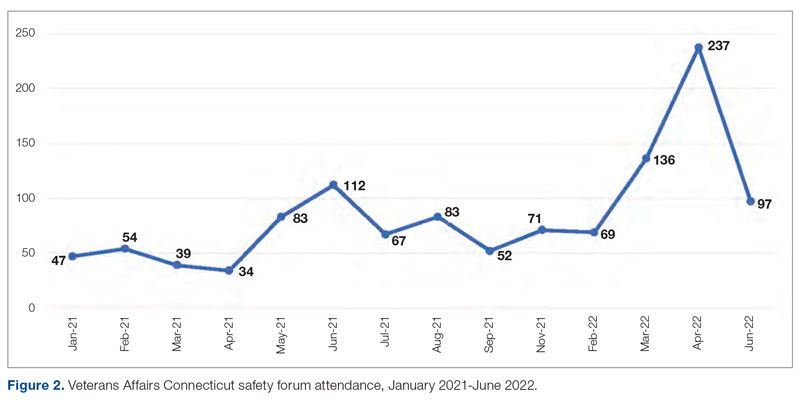

With the inclusion of information regarding awardees and their actions in monthly safety forums, attendance at these forums has increased from an average of 64 attendees per month in 2021 to an average of 131 attendees per month in 2022 (Figure 2).

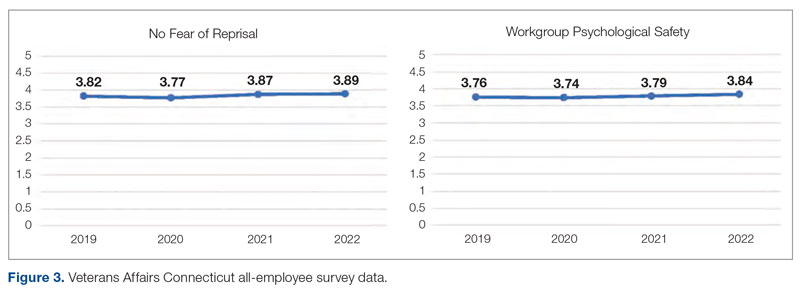

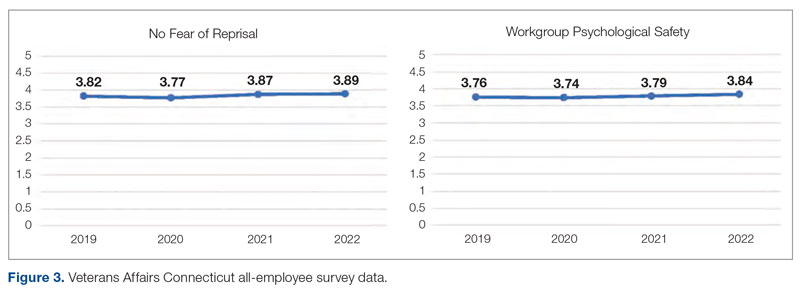

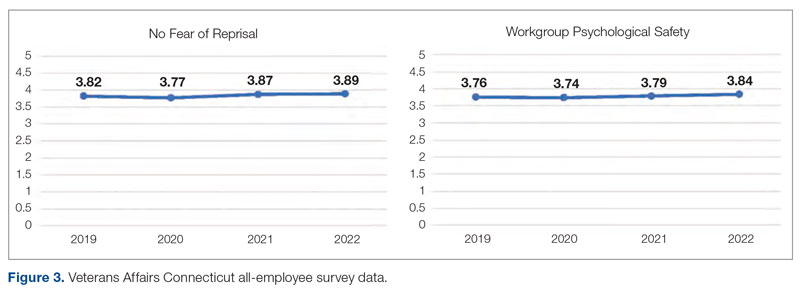

Finally, our organization’s annual All-Employee Survey results have shown incremental increases in staff reporting feeling psychologically safe and not fearing reprisal (Figure 3). It is important to note that there may be other contributing factors to these incremental changes.

Level 1 – Good Catch Award. M.S. was assigned as a continuous safety monitor, or “sitter,” on one of the med/surg inpatient units. M.S. arrived at the bedside and asked for a report on the patient at a change in shift. The report stated that the patient was sleeping and had not moved in a while. M.S. set about to perform the functions of a sitter and did her usual tasks in cleaning and tidying the room for the patient for breakfast and taking care of all items in the room, in general. M.S. introduced herself to the patient, who she thought might wake up because of her speaking to him. She thought the patient was in an odd position, and knowing that a patient should be a little further up in the bed, she tried with touch to awaken him to adjust his position. M.S. found that the patient was rather chilly to the touch and immediately became concerned. She continued to attempt to rouse the patient. M.S. called for the nurse and began to adjust the patient’s position. M.S. insisted that the patient was cold and “something was wrong.” A set of vitals was taken and a rapid response team code was called. The patient was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit to receive a higher level of care. If not for the diligence and caring attitude of M.S., this patient may have had a very poor outcome.

Reason for criteria being met: The scope of practice of a sitter is to be present in a patient’s room to monitor for falls and overall safety. This employee noticed that the patient was not responsive to verbal or tactile stimuli. Her immediate reporting of her concern to the nurse resulted in prompt intervention. If she had let the patient be, the patient could have died. The staff member went above and beyond by speaking up and taking action when she had a patient safety concern.

Level 2 – HRO Safety Champion Award. A patient presented to an outpatient clinic for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for a COVID-19 infection; the treatment has been scheduled by the patient’s primary care provider. At that time, outpatient mAb therapy was the recommended care option for patients stable enough to receive treatment in this setting, but it is contraindicated in patients who are too unstable to receive mAb therapy in an outpatient setting, such as those with increased oxygen demands. R.L., a staff nurse, assessed the patient on arrival and found that his vital signs were stable, except for a slightly elevated respiratory rate. Upon questioning, the patient reported that he had increased his oxygen use at home from 2 to 4 L via a nasal cannula. R.L. assessed that the patient was too high-risk for outpatient mAb therapy and had the patient checked into the emergency department (ED) to receive a full diagnostic workup and evaluation by Dr. W., an ED provider. The patient required admission to the hospital for a higher level of care in an inpatient unit because of severe COVID-19 infection. Within 48 hours of admission, the patient’s condition further declined, requiring an upgrade to the medical intensive care unit with progressive interventions. Owing to the clinical assessment skills and prompt action of R.L., the patient was admitted to the hospital instead of receiving treatment in a suboptimal care setting and returning home. Had the patient gone home, his rapid decline could have had serious consequences.

Reason for criteria being met: On a cursory look, the patient may have passed as someone sufficiently stable to undergo outpatient treatment. However, the nurse stopped the line, paid close attention, and picked up on an abnormal vital sign and the projected consequences. The nurse brought the patient to a higher level of care in the ED so that he could get the attention he needed. If this patient was given mAb therapy in the outpatient setting, he would have been discharged and become sicker with the COVID-19 illness. As a result of this incident, R.L. is working with the outpatient clinic and ED staff to enahance triage and evaluation of patients referred for outpatient therapy for COVID-19 infections to prevent a similar event from recurring.

Level 3 – Culture of Safety Appreciation Award. While C.C. was reviewing the hazardous item

Reason for criteria being met: The employee works in the hospital education department. It is within her scope of responsibilities to provide ongoing education to staff in order to address potential safety concerns.

DISCUSSION

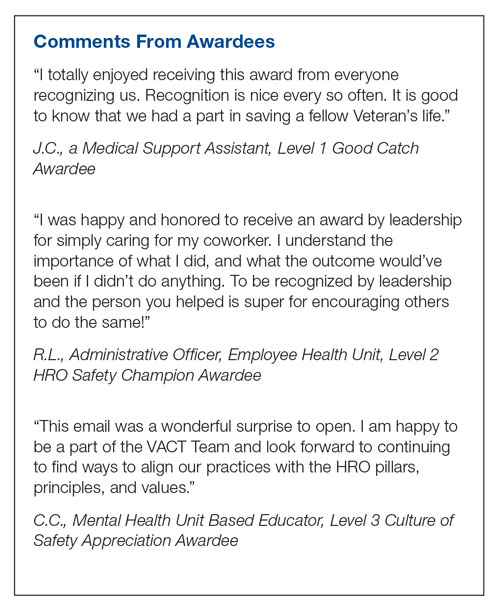

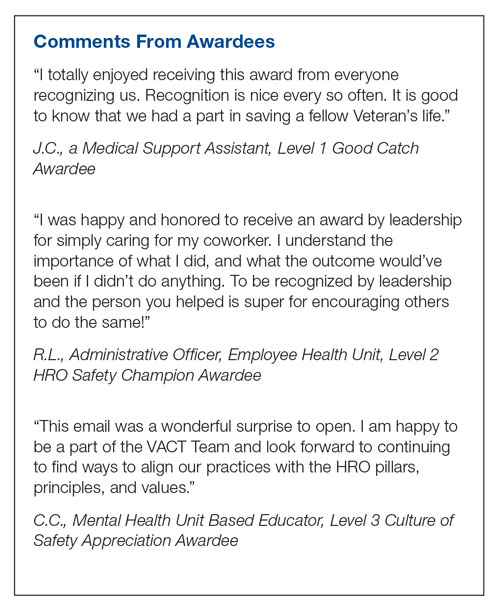

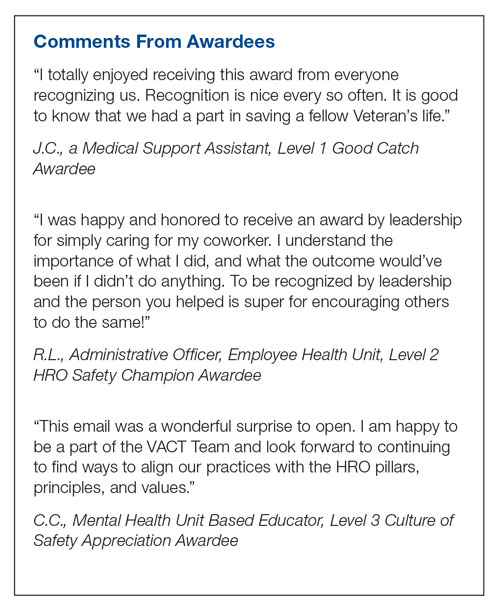

This QI initiative was undertaken to demonstrate to staff that, in building an organizational culture of safety and advancing quality health care, it is important that staff be encouraged to speak up for safety and be acknowledged for doing so. As part of efforts to continuously build on a safety-first culture, transparency and celebration of successes were demonstrated. This QI initiative demonstrated that a diverse and wide range of employees were reached, from clinical to nonclinical staff, and frontline to supervisory staff, as all were included in the recognition process. While many award nominations were received through the submission of safety concerns to the high-reliability team and patient safety office, several came directly from staff who wanted to recognize their peers for their work, supporting a culture of safety. This showed that staff felt that taking the time to submit a write-up to recognize a peer was an important task. Achieving zero harm for patients and staff alike is a top priority for our institution and guides all decisions, which reinforces that everyone has a responsibility to ensure that safety is always the first consideration. A culture of safety is enhanced by staff recognition. This QI initiative also showed that staff felt valued when they were acknowledged, regardless of the level of recognition they received. The theme of feeling valued came from unsolicited feedback. For example, some direct comments from awardees are presented in the Box.

In addition to endorsing the importance of safe practices to staff, safety award programs can identify gaps in existing standard procedures that can be updated quickly and shared broadly across a health care organization. The authors observed that the existence of the award program gives staff permission to use their voice to speak up when they have questions or concerns related to safety and to proactively engage in safety practices; a cultural shift of this kind informs safety practices and procedures and contributes to a more inspiring workplace. Staff at our organization who have received any of the safety awards, and those who are aware of these awards, have embraced the program readily. At the time of submission of this manuscript, there was a relative paucity of published literature on the details, performance, and impact of such programs. This initiative aims to share a road map highlighting the various dimensions of staff recognition and how the program supports our health care system in fostering a strong, sustainable culture of safety and health care quality. A next step is to formally assess the impact of the awards program on our culture of safety and quality using a psychometrically sound measurement tool, as recommended by TJC,16 such as the

CONCLUSION

A health care organization safety awards program is a strategy for building and sustaining a culture of safety. This QI initiative may be valuable to other organizations in the process of establishing a safety awards program of their own. Future research should focus on a formal evaluation of the impact of safety awards programs on patient safety outcomes.

Corresponding author: John S. Murray, PhD, MPH, MSGH, RN, FAAN, 20 Chapel Street, Unit A502, Brookline, MA 02446; JMurray325@aol.com

Disclosures: None reported.

1. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies. National Library of Medicine; 2019.

2.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Implementing near-miss reporting and improvement tracking in primary care practices: lessons learned. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

4. Hamed M, Konstantinidis S. Barriers to incident reporting among nurses: a qualitative systematic review. West J Nurs Res. 2022;44(5):506-523. doi:10.1177/0193945921999449

5. Mohamed M, Abubeker IY, Al-Mohanadi D, et al. Perceived barriers of incident reporting among internists: results from Hamad medical corporation in Qatar. Avicenna J Med. 2021;11(3):139-144. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1734386

6. The Joint Commission. The essential role of leadership in developing a safety culture. The Joint Commission; 2017.

7. Yali G, Nzala S. Healthcare providers’ perspective on barriers to patient safety incident reporting in Lusaka District. J Prev Rehabil Med. 2022;4:44-52. doi:10.21617/jprm2022.417

8. Herzer KR, Mirrer M, Xie Y, et al. Patient safety reporting systems: sustained quality improvement using a multidisciplinary team and “good catch” awards. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(8):339-347. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38044-6

9. Rogers E, Griffin E, Carnie W, et al. A just culture approach to managing medication errors. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(4):308-315. doi:10.1310/hpj5204-308

10. Murray JS, Clifford J, Larson S, et al. Implementing just culture to improve patient safety. Mil Med. 2022;0: 1. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac115

11. Paradiso L, Sweeney N. Just culture: it’s more than policy. Nurs Manag. 2019;50(6):38–45. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000558482.07815.ae

12. Wallace S, Mamrol M, Finley E; Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority. Promote a culture of safety with good catch reports. PA Patient Saf Advis. 2017;14(3).

13. Tan KH, Pang NL, Siau C, et al: Building an organizational culture of patient safety. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019;24:253-261. doi.10.1177/251604351987897

14. Merchant N, O’Neal J, Dealino-Perez C, et al: A high reliability mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37(6):504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

15. Behavioral interview questions and answers. Hudson. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://au.hudson.com/insights/career-advice/job-interviews/behavioural-interview-questions-and-answers/

16. The Joint Commission. Safety culture assessment: Improving the survey process. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/accred-and-cert/safety_culture_assessment_improving_the_survey_process.pdf

17. Reis CT, Paiva SG, Sousa P. The patient safety culture: a systematic review by characteristics of hospital survey on patient safety culture dimensions. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2018;30(9):660-677. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy080

18. Fourar YO, Benhassine W, Boughaba A, et al. Contribution to the assessment of patient safety culture in Algerian healthcare settings: the ASCO project. Int J Healthc Manag. 2022;15:52-61. doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2020.1836736

ABSTRACT

Objective: Promoting a culture of safety is a critical component of improving health care quality. Recognizing staff who stop the line for safety can positively impact the growth of a culture of safety. The purpose of this initiative was to demonstrate to staff the importance of speaking up for safety and being acknowledged for doing so.

Methods: Following a review of the literature on safety awards programs and their role in promoting a culture of safety in health care covering the period 2017 to 2020, a formal process was developed and implemented to disseminate safety awards to employees.

Results: During the initial 18 months of the initiative, a total of 59 awards were presented. The awards were well received by the recipients and other staff members. Within this period, adjustments were made to enhance the scope and reach of the program.

Conclusion: Recognizing staff behaviors that support a culture of safety is important for improving health care quality and employee engagement. Future research should focus on a formal evaluation of the impact of safety awards programs on patient safety outcomes.

Keywords: patient safety, culture of safety, incident reporting, near miss.

A key aspect of improving health care quality is promoting and sustaining a culture of safety in the workplace. Improving the quality of health care services and systems involves making informed choices regarding the types of strategies to implement.1 An essential aspect of supporting a safety culture is safety-event reporting. To approach the goal of zero harm, all safety events, whether they result in actual harm or are considered near misses, need to be reported. Near-miss events are errors that occur while care is being provided but are detected and corrected before harm reaches the patient.1-3 Near-miss reporting plays a critical role in helping to identify and correct weaknesses in health care delivery systems and processes.4 However, evidence shows that there are a multitude of barriers to the reporting of near-miss events, such as fear of punitive actions, additional workload, unsupportive work environments, a culture with poor psychological safety, knowledge deficit, and lack of recognition of staff who do report near misses.4-11

According to The Joint Commission (TJC), acknowledging health care team members who recognize and report unsafe conditions that provide insight for improving patient safety is a key method for promoting the reporting of near-miss events.6 As a result, some health care organizations and patient safety agencies have started to institute some form of recognition for their employees in the realm of safety.8-10 The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority offers exceptional guidance for creating a safety awards program to promote a culture of safety.12 Furthermore, TJC supports recognizing individuals and health care teams who identify and report near misses, or who have suggestions for initiatives to promote patient safety, with “good catch” awards. Individuals or teams working to promote and sustain a culture of safety should be recognized for their efforts. Acknowledging “good catches” to reward the identification, communication, and resolution of safety issues is an effective strategy for improving patient safety and health care quality.6,8

This quality improvement (QI) initiative was undertaken to demonstrate to staff that, in building an organizational culture of safety, it is important that staff be encouraged to speak up for safety and be acknowledged for doing so. If health care organizations want staff to be motivated to report near misses and improve safety and health care quality, the culture needs to shift from focusing on blame to incentivizing individuals and teams to speak up when they have concerns.8-10 Although deciding which safety actions are worthy of recognition can be challenging, recognizing all safe acts, regardless of how big or small they are perceived to be, is important. This QI initiative aimed to establish a tiered approach to recognize staff members for various categories of safety acts.

METHODS

A review of the literature from January 2017 to May 2020 for peer-reviewed publications regarding how other organizations implemented safety award programs to promote a culture of safety resulted in a dearth of evidence. This prompted us at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System to develop and implement a formal program to disseminate safety awards to employees.

Program Launch and Promotion

In 2020, our institution embarked on a journey to high reliability with the goal of approaching zero harm. As part of efforts to promote a culture of safety, the hospital’s High Reliability Organization (HRO) team worked to develop a safety awards recognition program. Prior to the launch, the hospital’s patient safety committee recognized staff members through the medical center safety event reporting system (the Joint Patient Safety Reporting system [JPSR]) or through direct communication with staff members on safety actions they were engaged in. JPSR is the Veterans Health Administration National Center for Patient Safety incident reporting system for reporting, tracking, and trending of patient incidents in a national database. The award consisted of a certificate presented by the patient safety committee chairpersons to the employee in front of their peers in their respective work area. Hospital leadership was not involved in the safety awards recognition program at that time. No nomination process existed prior to our QI launch.

Once the QI initiative was launched and marketed heavily at staff meetings, we started to receive nominations for actions that were truly exceptional, while many others were submitted for behaviors that were within the day-to-day scope of practice of the staff member. For those early nominations that did not meet criteria for an award, we thanked staff for their submissions with a gentle statement that their nomination did not meet the criteria for an award. After following this practice for a few weeks, we became concerned that if we did not acknowledge the staff who came forward to request recognition for their routine work that supported safety, we could risk losing their engagement in a culture of safety. As such, we decided to create 3 levels of awards to recognize behaviors that went above and beyond while also acknowledging staff for actions within their scope of practice. Additionally, hospital leadership wanted to ensure that all staff recognize that their safety efforts are valued by leadership and that that sense of value will hopefully contribute to a culture of safety over time.

Initially, the single award system was called the “Good Catch Award” to acknowledge staff who go above and beyond to speak up and take action when they have safety concerns. This particular recognition includes a certificate, an encased baseball card that has been personalized by including the staff member’s picture and safety event identified, a stress-release baseball, and a stick of Bazooka gum (similar to what used to come in baseball cards packs). The award is presented to employees in their work area by the HRO and patient safety teams and includes representatives from the executive leadership team (ELT). The safety event identified is described by an ELT member, and all items are presented to the employee. Participation by the leadership team communicates how much the work being done to promote a culture of safety and advance quality health care is appreciated. This action also encourages others in the organization to identify and report safety concerns.13

With the rollout of the QI initiative, the volume of nominations submitted quickly increased (eg, approximately 1 every 2 months before to 3 per month following implementation). Frequently, nominations were for actions believed to be within the scope of the employee’s responsibilities. Our institution’s leadership team quickly recognized that, as an organization, not diminishing the importance of the “Good Catch Award” was important. However, the

The original Good Catch Award was labelled as a Level 1 award. The Level 2 safety recognition award, named the HRO Safety Champion Award, is given to employees who stop the line for a safety concern within their scope of practice and also participate as part of a team to investigate and improve processes to avoid recurring safety concerns in the future. For the Level Two award, a certificate is presented to an employee by the hospital’s HRO lead, HRO physician champion, patient safety manager, immediate supervisor, and peers. With the Level 3 award, the Culture of Safety Appreciation Award, individuals are recognized for addressing safety concerns within their assigned scope of responsibilities. Recognition is bestowed by an email of appreciation sent to the employee, acknowledging their commitment to promoting a culture of safety and quality health care. The recipient’s direct supervisor and other hospital leaders are copied on the message.14 See Table 1 for a

Our institution’s HRO and patient safety teams utilized many additional venues to disseminate information regarding awardees and their actions. These included our monthly HRO newsletter, monthly safety forums, and biweekly Team Connecticut Healthcare system-wide huddles.

Nomination Process

Awards nominations are submitted via the hospital intranet homepage, where there is an “HRO Safety Award Nomination” icon. Once a staff member clicks the icon, a template opens asking for information, such as the reason for the nomination submission, and then walks them through the template using the CAR (C-context, A-actions, and R-results)15 format for describing the situation, identifying actions taken, and specifying the outcome of the action. Emails with award nominations can also be sent to the HRO lead, HRO champion, or Patient Safety Committee co-chairs. Calls for nominations are made at several venues attended by employees as well as supervisors. These include monthly safety forums, biweekly Team Connecticut Healthcare system-wide huddles, supervisory staff meetings, department and unit-based staff meetings, and many other formal and informal settings. This QI initiative has allowed us to capture potential awardees through several avenues, including self-nominations. All nominations are reviewed by a safety awards committee. Each committee member ranks the nomination as a Level 1, 2, or 3 award. For nominations where conflicting scores are obtained, the committee discusses the nomination together to resolve discrepancies.

Needed Resources

Material resources required for this QI initiative include certificate paper, plastic baseball card sleeves, stress-release baseballs, and Bazooka gum. The largest resource investment was the time needed to support the initiative. This included the time spent scheduling the Level 1 and 2 award presentations with staff and leadership. Time was also required to put the individual award packages together, which included printing the paper certificates, obtaining awardee pictures, placing them with their safety stories in a plastic baseball card sleeve, and arranging for the hospital photographer to take pictures of the awardees with their peers and leaders.

RESULTS

Prior to this QI initiative launch, 14 awards were given out over the preceding 2-year period. During the initial 18 months of the initiative (December 2020 to June 2022), 59 awards were presented (Level 1, n = 26; Level 2, n = 22; and Level 3, n = 11). Looking further into the Level 1 awards presented, 25 awardees worked in clinical roles and 1 in a nonclinical position (Table 2). The awardees represented multidisciplinary areas, including medical/surgical (med/surg) inpatient units, anesthesia, operating room, pharmacy, mental health clinics, surgical intensive care, specialty care clinics, and nutrition and food services. With the Level 2 awards, 18 clinical staff and 4 nonclinical staff received awards from the areas of med/surg inpatient, outpatient surgical suites, the medical center director’s office, radiology, pharmacy, primary care, facilities management, environmental management, infection prevention, and emergency services. All Level 3 awardees were from clinical areas, including primary care, hospital education, sterile processing, pharmacies, operating rooms, and med/surg inpatient units.

With the inception of this QI initiative, our organization has begun to see trends reflecting increased reporting of both actual and close-call events in JPSR (Figure 1).

With the inclusion of information regarding awardees and their actions in monthly safety forums, attendance at these forums has increased from an average of 64 attendees per month in 2021 to an average of 131 attendees per month in 2022 (Figure 2).

Finally, our organization’s annual All-Employee Survey results have shown incremental increases in staff reporting feeling psychologically safe and not fearing reprisal (Figure 3). It is important to note that there may be other contributing factors to these incremental changes.

Level 1 – Good Catch Award. M.S. was assigned as a continuous safety monitor, or “sitter,” on one of the med/surg inpatient units. M.S. arrived at the bedside and asked for a report on the patient at a change in shift. The report stated that the patient was sleeping and had not moved in a while. M.S. set about to perform the functions of a sitter and did her usual tasks in cleaning and tidying the room for the patient for breakfast and taking care of all items in the room, in general. M.S. introduced herself to the patient, who she thought might wake up because of her speaking to him. She thought the patient was in an odd position, and knowing that a patient should be a little further up in the bed, she tried with touch to awaken him to adjust his position. M.S. found that the patient was rather chilly to the touch and immediately became concerned. She continued to attempt to rouse the patient. M.S. called for the nurse and began to adjust the patient’s position. M.S. insisted that the patient was cold and “something was wrong.” A set of vitals was taken and a rapid response team code was called. The patient was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit to receive a higher level of care. If not for the diligence and caring attitude of M.S., this patient may have had a very poor outcome.

Reason for criteria being met: The scope of practice of a sitter is to be present in a patient’s room to monitor for falls and overall safety. This employee noticed that the patient was not responsive to verbal or tactile stimuli. Her immediate reporting of her concern to the nurse resulted in prompt intervention. If she had let the patient be, the patient could have died. The staff member went above and beyond by speaking up and taking action when she had a patient safety concern.

Level 2 – HRO Safety Champion Award. A patient presented to an outpatient clinic for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for a COVID-19 infection; the treatment has been scheduled by the patient’s primary care provider. At that time, outpatient mAb therapy was the recommended care option for patients stable enough to receive treatment in this setting, but it is contraindicated in patients who are too unstable to receive mAb therapy in an outpatient setting, such as those with increased oxygen demands. R.L., a staff nurse, assessed the patient on arrival and found that his vital signs were stable, except for a slightly elevated respiratory rate. Upon questioning, the patient reported that he had increased his oxygen use at home from 2 to 4 L via a nasal cannula. R.L. assessed that the patient was too high-risk for outpatient mAb therapy and had the patient checked into the emergency department (ED) to receive a full diagnostic workup and evaluation by Dr. W., an ED provider. The patient required admission to the hospital for a higher level of care in an inpatient unit because of severe COVID-19 infection. Within 48 hours of admission, the patient’s condition further declined, requiring an upgrade to the medical intensive care unit with progressive interventions. Owing to the clinical assessment skills and prompt action of R.L., the patient was admitted to the hospital instead of receiving treatment in a suboptimal care setting and returning home. Had the patient gone home, his rapid decline could have had serious consequences.

Reason for criteria being met: On a cursory look, the patient may have passed as someone sufficiently stable to undergo outpatient treatment. However, the nurse stopped the line, paid close attention, and picked up on an abnormal vital sign and the projected consequences. The nurse brought the patient to a higher level of care in the ED so that he could get the attention he needed. If this patient was given mAb therapy in the outpatient setting, he would have been discharged and become sicker with the COVID-19 illness. As a result of this incident, R.L. is working with the outpatient clinic and ED staff to enahance triage and evaluation of patients referred for outpatient therapy for COVID-19 infections to prevent a similar event from recurring.

Level 3 – Culture of Safety Appreciation Award. While C.C. was reviewing the hazardous item

Reason for criteria being met: The employee works in the hospital education department. It is within her scope of responsibilities to provide ongoing education to staff in order to address potential safety concerns.

DISCUSSION

This QI initiative was undertaken to demonstrate to staff that, in building an organizational culture of safety and advancing quality health care, it is important that staff be encouraged to speak up for safety and be acknowledged for doing so. As part of efforts to continuously build on a safety-first culture, transparency and celebration of successes were demonstrated. This QI initiative demonstrated that a diverse and wide range of employees were reached, from clinical to nonclinical staff, and frontline to supervisory staff, as all were included in the recognition process. While many award nominations were received through the submission of safety concerns to the high-reliability team and patient safety office, several came directly from staff who wanted to recognize their peers for their work, supporting a culture of safety. This showed that staff felt that taking the time to submit a write-up to recognize a peer was an important task. Achieving zero harm for patients and staff alike is a top priority for our institution and guides all decisions, which reinforces that everyone has a responsibility to ensure that safety is always the first consideration. A culture of safety is enhanced by staff recognition. This QI initiative also showed that staff felt valued when they were acknowledged, regardless of the level of recognition they received. The theme of feeling valued came from unsolicited feedback. For example, some direct comments from awardees are presented in the Box.

In addition to endorsing the importance of safe practices to staff, safety award programs can identify gaps in existing standard procedures that can be updated quickly and shared broadly across a health care organization. The authors observed that the existence of the award program gives staff permission to use their voice to speak up when they have questions or concerns related to safety and to proactively engage in safety practices; a cultural shift of this kind informs safety practices and procedures and contributes to a more inspiring workplace. Staff at our organization who have received any of the safety awards, and those who are aware of these awards, have embraced the program readily. At the time of submission of this manuscript, there was a relative paucity of published literature on the details, performance, and impact of such programs. This initiative aims to share a road map highlighting the various dimensions of staff recognition and how the program supports our health care system in fostering a strong, sustainable culture of safety and health care quality. A next step is to formally assess the impact of the awards program on our culture of safety and quality using a psychometrically sound measurement tool, as recommended by TJC,16 such as the

CONCLUSION

A health care organization safety awards program is a strategy for building and sustaining a culture of safety. This QI initiative may be valuable to other organizations in the process of establishing a safety awards program of their own. Future research should focus on a formal evaluation of the impact of safety awards programs on patient safety outcomes.

Corresponding author: John S. Murray, PhD, MPH, MSGH, RN, FAAN, 20 Chapel Street, Unit A502, Brookline, MA 02446; JMurray325@aol.com

Disclosures: None reported.

ABSTRACT

Objective: Promoting a culture of safety is a critical component of improving health care quality. Recognizing staff who stop the line for safety can positively impact the growth of a culture of safety. The purpose of this initiative was to demonstrate to staff the importance of speaking up for safety and being acknowledged for doing so.

Methods: Following a review of the literature on safety awards programs and their role in promoting a culture of safety in health care covering the period 2017 to 2020, a formal process was developed and implemented to disseminate safety awards to employees.

Results: During the initial 18 months of the initiative, a total of 59 awards were presented. The awards were well received by the recipients and other staff members. Within this period, adjustments were made to enhance the scope and reach of the program.

Conclusion: Recognizing staff behaviors that support a culture of safety is important for improving health care quality and employee engagement. Future research should focus on a formal evaluation of the impact of safety awards programs on patient safety outcomes.

Keywords: patient safety, culture of safety, incident reporting, near miss.

A key aspect of improving health care quality is promoting and sustaining a culture of safety in the workplace. Improving the quality of health care services and systems involves making informed choices regarding the types of strategies to implement.1 An essential aspect of supporting a safety culture is safety-event reporting. To approach the goal of zero harm, all safety events, whether they result in actual harm or are considered near misses, need to be reported. Near-miss events are errors that occur while care is being provided but are detected and corrected before harm reaches the patient.1-3 Near-miss reporting plays a critical role in helping to identify and correct weaknesses in health care delivery systems and processes.4 However, evidence shows that there are a multitude of barriers to the reporting of near-miss events, such as fear of punitive actions, additional workload, unsupportive work environments, a culture with poor psychological safety, knowledge deficit, and lack of recognition of staff who do report near misses.4-11

According to The Joint Commission (TJC), acknowledging health care team members who recognize and report unsafe conditions that provide insight for improving patient safety is a key method for promoting the reporting of near-miss events.6 As a result, some health care organizations and patient safety agencies have started to institute some form of recognition for their employees in the realm of safety.8-10 The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority offers exceptional guidance for creating a safety awards program to promote a culture of safety.12 Furthermore, TJC supports recognizing individuals and health care teams who identify and report near misses, or who have suggestions for initiatives to promote patient safety, with “good catch” awards. Individuals or teams working to promote and sustain a culture of safety should be recognized for their efforts. Acknowledging “good catches” to reward the identification, communication, and resolution of safety issues is an effective strategy for improving patient safety and health care quality.6,8

This quality improvement (QI) initiative was undertaken to demonstrate to staff that, in building an organizational culture of safety, it is important that staff be encouraged to speak up for safety and be acknowledged for doing so. If health care organizations want staff to be motivated to report near misses and improve safety and health care quality, the culture needs to shift from focusing on blame to incentivizing individuals and teams to speak up when they have concerns.8-10 Although deciding which safety actions are worthy of recognition can be challenging, recognizing all safe acts, regardless of how big or small they are perceived to be, is important. This QI initiative aimed to establish a tiered approach to recognize staff members for various categories of safety acts.

METHODS

A review of the literature from January 2017 to May 2020 for peer-reviewed publications regarding how other organizations implemented safety award programs to promote a culture of safety resulted in a dearth of evidence. This prompted us at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System to develop and implement a formal program to disseminate safety awards to employees.

Program Launch and Promotion

In 2020, our institution embarked on a journey to high reliability with the goal of approaching zero harm. As part of efforts to promote a culture of safety, the hospital’s High Reliability Organization (HRO) team worked to develop a safety awards recognition program. Prior to the launch, the hospital’s patient safety committee recognized staff members through the medical center safety event reporting system (the Joint Patient Safety Reporting system [JPSR]) or through direct communication with staff members on safety actions they were engaged in. JPSR is the Veterans Health Administration National Center for Patient Safety incident reporting system for reporting, tracking, and trending of patient incidents in a national database. The award consisted of a certificate presented by the patient safety committee chairpersons to the employee in front of their peers in their respective work area. Hospital leadership was not involved in the safety awards recognition program at that time. No nomination process existed prior to our QI launch.

Once the QI initiative was launched and marketed heavily at staff meetings, we started to receive nominations for actions that were truly exceptional, while many others were submitted for behaviors that were within the day-to-day scope of practice of the staff member. For those early nominations that did not meet criteria for an award, we thanked staff for their submissions with a gentle statement that their nomination did not meet the criteria for an award. After following this practice for a few weeks, we became concerned that if we did not acknowledge the staff who came forward to request recognition for their routine work that supported safety, we could risk losing their engagement in a culture of safety. As such, we decided to create 3 levels of awards to recognize behaviors that went above and beyond while also acknowledging staff for actions within their scope of practice. Additionally, hospital leadership wanted to ensure that all staff recognize that their safety efforts are valued by leadership and that that sense of value will hopefully contribute to a culture of safety over time.

Initially, the single award system was called the “Good Catch Award” to acknowledge staff who go above and beyond to speak up and take action when they have safety concerns. This particular recognition includes a certificate, an encased baseball card that has been personalized by including the staff member’s picture and safety event identified, a stress-release baseball, and a stick of Bazooka gum (similar to what used to come in baseball cards packs). The award is presented to employees in their work area by the HRO and patient safety teams and includes representatives from the executive leadership team (ELT). The safety event identified is described by an ELT member, and all items are presented to the employee. Participation by the leadership team communicates how much the work being done to promote a culture of safety and advance quality health care is appreciated. This action also encourages others in the organization to identify and report safety concerns.13

With the rollout of the QI initiative, the volume of nominations submitted quickly increased (eg, approximately 1 every 2 months before to 3 per month following implementation). Frequently, nominations were for actions believed to be within the scope of the employee’s responsibilities. Our institution’s leadership team quickly recognized that, as an organization, not diminishing the importance of the “Good Catch Award” was important. However, the

The original Good Catch Award was labelled as a Level 1 award. The Level 2 safety recognition award, named the HRO Safety Champion Award, is given to employees who stop the line for a safety concern within their scope of practice and also participate as part of a team to investigate and improve processes to avoid recurring safety concerns in the future. For the Level Two award, a certificate is presented to an employee by the hospital’s HRO lead, HRO physician champion, patient safety manager, immediate supervisor, and peers. With the Level 3 award, the Culture of Safety Appreciation Award, individuals are recognized for addressing safety concerns within their assigned scope of responsibilities. Recognition is bestowed by an email of appreciation sent to the employee, acknowledging their commitment to promoting a culture of safety and quality health care. The recipient’s direct supervisor and other hospital leaders are copied on the message.14 See Table 1 for a

Our institution’s HRO and patient safety teams utilized many additional venues to disseminate information regarding awardees and their actions. These included our monthly HRO newsletter, monthly safety forums, and biweekly Team Connecticut Healthcare system-wide huddles.

Nomination Process

Awards nominations are submitted via the hospital intranet homepage, where there is an “HRO Safety Award Nomination” icon. Once a staff member clicks the icon, a template opens asking for information, such as the reason for the nomination submission, and then walks them through the template using the CAR (C-context, A-actions, and R-results)15 format for describing the situation, identifying actions taken, and specifying the outcome of the action. Emails with award nominations can also be sent to the HRO lead, HRO champion, or Patient Safety Committee co-chairs. Calls for nominations are made at several venues attended by employees as well as supervisors. These include monthly safety forums, biweekly Team Connecticut Healthcare system-wide huddles, supervisory staff meetings, department and unit-based staff meetings, and many other formal and informal settings. This QI initiative has allowed us to capture potential awardees through several avenues, including self-nominations. All nominations are reviewed by a safety awards committee. Each committee member ranks the nomination as a Level 1, 2, or 3 award. For nominations where conflicting scores are obtained, the committee discusses the nomination together to resolve discrepancies.

Needed Resources

Material resources required for this QI initiative include certificate paper, plastic baseball card sleeves, stress-release baseballs, and Bazooka gum. The largest resource investment was the time needed to support the initiative. This included the time spent scheduling the Level 1 and 2 award presentations with staff and leadership. Time was also required to put the individual award packages together, which included printing the paper certificates, obtaining awardee pictures, placing them with their safety stories in a plastic baseball card sleeve, and arranging for the hospital photographer to take pictures of the awardees with their peers and leaders.

RESULTS

Prior to this QI initiative launch, 14 awards were given out over the preceding 2-year period. During the initial 18 months of the initiative (December 2020 to June 2022), 59 awards were presented (Level 1, n = 26; Level 2, n = 22; and Level 3, n = 11). Looking further into the Level 1 awards presented, 25 awardees worked in clinical roles and 1 in a nonclinical position (Table 2). The awardees represented multidisciplinary areas, including medical/surgical (med/surg) inpatient units, anesthesia, operating room, pharmacy, mental health clinics, surgical intensive care, specialty care clinics, and nutrition and food services. With the Level 2 awards, 18 clinical staff and 4 nonclinical staff received awards from the areas of med/surg inpatient, outpatient surgical suites, the medical center director’s office, radiology, pharmacy, primary care, facilities management, environmental management, infection prevention, and emergency services. All Level 3 awardees were from clinical areas, including primary care, hospital education, sterile processing, pharmacies, operating rooms, and med/surg inpatient units.

With the inception of this QI initiative, our organization has begun to see trends reflecting increased reporting of both actual and close-call events in JPSR (Figure 1).

With the inclusion of information regarding awardees and their actions in monthly safety forums, attendance at these forums has increased from an average of 64 attendees per month in 2021 to an average of 131 attendees per month in 2022 (Figure 2).

Finally, our organization’s annual All-Employee Survey results have shown incremental increases in staff reporting feeling psychologically safe and not fearing reprisal (Figure 3). It is important to note that there may be other contributing factors to these incremental changes.

Level 1 – Good Catch Award. M.S. was assigned as a continuous safety monitor, or “sitter,” on one of the med/surg inpatient units. M.S. arrived at the bedside and asked for a report on the patient at a change in shift. The report stated that the patient was sleeping and had not moved in a while. M.S. set about to perform the functions of a sitter and did her usual tasks in cleaning and tidying the room for the patient for breakfast and taking care of all items in the room, in general. M.S. introduced herself to the patient, who she thought might wake up because of her speaking to him. She thought the patient was in an odd position, and knowing that a patient should be a little further up in the bed, she tried with touch to awaken him to adjust his position. M.S. found that the patient was rather chilly to the touch and immediately became concerned. She continued to attempt to rouse the patient. M.S. called for the nurse and began to adjust the patient’s position. M.S. insisted that the patient was cold and “something was wrong.” A set of vitals was taken and a rapid response team code was called. The patient was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit to receive a higher level of care. If not for the diligence and caring attitude of M.S., this patient may have had a very poor outcome.

Reason for criteria being met: The scope of practice of a sitter is to be present in a patient’s room to monitor for falls and overall safety. This employee noticed that the patient was not responsive to verbal or tactile stimuli. Her immediate reporting of her concern to the nurse resulted in prompt intervention. If she had let the patient be, the patient could have died. The staff member went above and beyond by speaking up and taking action when she had a patient safety concern.

Level 2 – HRO Safety Champion Award. A patient presented to an outpatient clinic for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for a COVID-19 infection; the treatment has been scheduled by the patient’s primary care provider. At that time, outpatient mAb therapy was the recommended care option for patients stable enough to receive treatment in this setting, but it is contraindicated in patients who are too unstable to receive mAb therapy in an outpatient setting, such as those with increased oxygen demands. R.L., a staff nurse, assessed the patient on arrival and found that his vital signs were stable, except for a slightly elevated respiratory rate. Upon questioning, the patient reported that he had increased his oxygen use at home from 2 to 4 L via a nasal cannula. R.L. assessed that the patient was too high-risk for outpatient mAb therapy and had the patient checked into the emergency department (ED) to receive a full diagnostic workup and evaluation by Dr. W., an ED provider. The patient required admission to the hospital for a higher level of care in an inpatient unit because of severe COVID-19 infection. Within 48 hours of admission, the patient’s condition further declined, requiring an upgrade to the medical intensive care unit with progressive interventions. Owing to the clinical assessment skills and prompt action of R.L., the patient was admitted to the hospital instead of receiving treatment in a suboptimal care setting and returning home. Had the patient gone home, his rapid decline could have had serious consequences.

Reason for criteria being met: On a cursory look, the patient may have passed as someone sufficiently stable to undergo outpatient treatment. However, the nurse stopped the line, paid close attention, and picked up on an abnormal vital sign and the projected consequences. The nurse brought the patient to a higher level of care in the ED so that he could get the attention he needed. If this patient was given mAb therapy in the outpatient setting, he would have been discharged and become sicker with the COVID-19 illness. As a result of this incident, R.L. is working with the outpatient clinic and ED staff to enahance triage and evaluation of patients referred for outpatient therapy for COVID-19 infections to prevent a similar event from recurring.

Level 3 – Culture of Safety Appreciation Award. While C.C. was reviewing the hazardous item

Reason for criteria being met: The employee works in the hospital education department. It is within her scope of responsibilities to provide ongoing education to staff in order to address potential safety concerns.

DISCUSSION

This QI initiative was undertaken to demonstrate to staff that, in building an organizational culture of safety and advancing quality health care, it is important that staff be encouraged to speak up for safety and be acknowledged for doing so. As part of efforts to continuously build on a safety-first culture, transparency and celebration of successes were demonstrated. This QI initiative demonstrated that a diverse and wide range of employees were reached, from clinical to nonclinical staff, and frontline to supervisory staff, as all were included in the recognition process. While many award nominations were received through the submission of safety concerns to the high-reliability team and patient safety office, several came directly from staff who wanted to recognize their peers for their work, supporting a culture of safety. This showed that staff felt that taking the time to submit a write-up to recognize a peer was an important task. Achieving zero harm for patients and staff alike is a top priority for our institution and guides all decisions, which reinforces that everyone has a responsibility to ensure that safety is always the first consideration. A culture of safety is enhanced by staff recognition. This QI initiative also showed that staff felt valued when they were acknowledged, regardless of the level of recognition they received. The theme of feeling valued came from unsolicited feedback. For example, some direct comments from awardees are presented in the Box.

In addition to endorsing the importance of safe practices to staff, safety award programs can identify gaps in existing standard procedures that can be updated quickly and shared broadly across a health care organization. The authors observed that the existence of the award program gives staff permission to use their voice to speak up when they have questions or concerns related to safety and to proactively engage in safety practices; a cultural shift of this kind informs safety practices and procedures and contributes to a more inspiring workplace. Staff at our organization who have received any of the safety awards, and those who are aware of these awards, have embraced the program readily. At the time of submission of this manuscript, there was a relative paucity of published literature on the details, performance, and impact of such programs. This initiative aims to share a road map highlighting the various dimensions of staff recognition and how the program supports our health care system in fostering a strong, sustainable culture of safety and health care quality. A next step is to formally assess the impact of the awards program on our culture of safety and quality using a psychometrically sound measurement tool, as recommended by TJC,16 such as the

CONCLUSION

A health care organization safety awards program is a strategy for building and sustaining a culture of safety. This QI initiative may be valuable to other organizations in the process of establishing a safety awards program of their own. Future research should focus on a formal evaluation of the impact of safety awards programs on patient safety outcomes.

Corresponding author: John S. Murray, PhD, MPH, MSGH, RN, FAAN, 20 Chapel Street, Unit A502, Brookline, MA 02446; JMurray325@aol.com

Disclosures: None reported.

1. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies. National Library of Medicine; 2019.

2.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Implementing near-miss reporting and improvement tracking in primary care practices: lessons learned. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

4. Hamed M, Konstantinidis S. Barriers to incident reporting among nurses: a qualitative systematic review. West J Nurs Res. 2022;44(5):506-523. doi:10.1177/0193945921999449

5. Mohamed M, Abubeker IY, Al-Mohanadi D, et al. Perceived barriers of incident reporting among internists: results from Hamad medical corporation in Qatar. Avicenna J Med. 2021;11(3):139-144. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1734386

6. The Joint Commission. The essential role of leadership in developing a safety culture. The Joint Commission; 2017.

7. Yali G, Nzala S. Healthcare providers’ perspective on barriers to patient safety incident reporting in Lusaka District. J Prev Rehabil Med. 2022;4:44-52. doi:10.21617/jprm2022.417

8. Herzer KR, Mirrer M, Xie Y, et al. Patient safety reporting systems: sustained quality improvement using a multidisciplinary team and “good catch” awards. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(8):339-347. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38044-6

9. Rogers E, Griffin E, Carnie W, et al. A just culture approach to managing medication errors. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(4):308-315. doi:10.1310/hpj5204-308

10. Murray JS, Clifford J, Larson S, et al. Implementing just culture to improve patient safety. Mil Med. 2022;0: 1. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac115

11. Paradiso L, Sweeney N. Just culture: it’s more than policy. Nurs Manag. 2019;50(6):38–45. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000558482.07815.ae

12. Wallace S, Mamrol M, Finley E; Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority. Promote a culture of safety with good catch reports. PA Patient Saf Advis. 2017;14(3).

13. Tan KH, Pang NL, Siau C, et al: Building an organizational culture of patient safety. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019;24:253-261. doi.10.1177/251604351987897

14. Merchant N, O’Neal J, Dealino-Perez C, et al: A high reliability mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37(6):504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

15. Behavioral interview questions and answers. Hudson. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://au.hudson.com/insights/career-advice/job-interviews/behavioural-interview-questions-and-answers/

16. The Joint Commission. Safety culture assessment: Improving the survey process. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/accred-and-cert/safety_culture_assessment_improving_the_survey_process.pdf

17. Reis CT, Paiva SG, Sousa P. The patient safety culture: a systematic review by characteristics of hospital survey on patient safety culture dimensions. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2018;30(9):660-677. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy080

18. Fourar YO, Benhassine W, Boughaba A, et al. Contribution to the assessment of patient safety culture in Algerian healthcare settings: the ASCO project. Int J Healthc Manag. 2022;15:52-61. doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2020.1836736

1. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies. National Library of Medicine; 2019.

2.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Implementing near-miss reporting and improvement tracking in primary care practices: lessons learned. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

4. Hamed M, Konstantinidis S. Barriers to incident reporting among nurses: a qualitative systematic review. West J Nurs Res. 2022;44(5):506-523. doi:10.1177/0193945921999449

5. Mohamed M, Abubeker IY, Al-Mohanadi D, et al. Perceived barriers of incident reporting among internists: results from Hamad medical corporation in Qatar. Avicenna J Med. 2021;11(3):139-144. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1734386

6. The Joint Commission. The essential role of leadership in developing a safety culture. The Joint Commission; 2017.

7. Yali G, Nzala S. Healthcare providers’ perspective on barriers to patient safety incident reporting in Lusaka District. J Prev Rehabil Med. 2022;4:44-52. doi:10.21617/jprm2022.417

8. Herzer KR, Mirrer M, Xie Y, et al. Patient safety reporting systems: sustained quality improvement using a multidisciplinary team and “good catch” awards. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(8):339-347. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38044-6

9. Rogers E, Griffin E, Carnie W, et al. A just culture approach to managing medication errors. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(4):308-315. doi:10.1310/hpj5204-308

10. Murray JS, Clifford J, Larson S, et al. Implementing just culture to improve patient safety. Mil Med. 2022;0: 1. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac115

11. Paradiso L, Sweeney N. Just culture: it’s more than policy. Nurs Manag. 2019;50(6):38–45. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000558482.07815.ae

12. Wallace S, Mamrol M, Finley E; Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority. Promote a culture of safety with good catch reports. PA Patient Saf Advis. 2017;14(3).

13. Tan KH, Pang NL, Siau C, et al: Building an organizational culture of patient safety. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019;24:253-261. doi.10.1177/251604351987897

14. Merchant N, O’Neal J, Dealino-Perez C, et al: A high reliability mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37(6):504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

15. Behavioral interview questions and answers. Hudson. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://au.hudson.com/insights/career-advice/job-interviews/behavioural-interview-questions-and-answers/

16. The Joint Commission. Safety culture assessment: Improving the survey process. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/accred-and-cert/safety_culture_assessment_improving_the_survey_process.pdf

17. Reis CT, Paiva SG, Sousa P. The patient safety culture: a systematic review by characteristics of hospital survey on patient safety culture dimensions. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2018;30(9):660-677. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy080

18. Fourar YO, Benhassine W, Boughaba A, et al. Contribution to the assessment of patient safety culture in Algerian healthcare settings: the ASCO project. Int J Healthc Manag. 2022;15:52-61. doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2020.1836736