User login

A Facility-Wide Plan to Increase Access to Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care and General Mental Health Settings

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

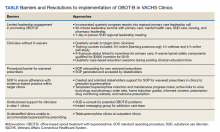

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

In reply: Prescribing opioids

In Reply: We thank Dr. Pettiway for his remarks. The intent of our article was to identify common challenges when prescribing opioids for chronic pain and offer tips to the provider struggling with how to do so safely. We hope these comments will offer additional clarity.

First, as general internists who are essentially “self-trained” in the management of chronic pain, we fully acknowledge the importance of practical experience in learning how to prescribe opioids safely and effectively. Dr. Pettiway is correct that a dedicated physician who keeps up with the medical literature, attends relevant continuing medical education courses, and strives to provide deliberate, rational, and evidence-based care to his or her patients can do so effectively. However, the medical literature suggests that medical school training in the management of chronic pain is sparse; one review found that in 2011 only 5 out of 133 US medical schools required coursework on pain management, and only 13 offered it as an elective.1 Many primary care providers do feel unprepared to handle this challenge.

Additionally, Dr. Pettiway raises a good question about where misused prescription opioids originate and whether prescribers are responsible. The data show that the majority of misused prescription opioids are obtained from a family member or friend and not directly from a physician.2,3 However, this supply does generally originate from a prescription. Providers need to educate their patients about the risk for diversion, the need to keep pills safely hidden and locked away, and the importance of safely discarding unused supplies. Responsible prescribers need to anticipate these concerns and educate patients about them.

In summary, we firmly believe that primary care providers are capable of safe, effective, and responsible opioid prescribing and hope that our paper provides additional guidance on how to do so.

- Roehr B. US needs new strategy to help 116 million patients in chronic pain. BMJ 2011; 343:d4206.

- Becker WC, Tobin DG, Fiellin DA. Nonmedical use of opioid analgesics obtained directly from physicians: prevalence and correlates. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1034–1036.

- Substance Abuse and Mental health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm. Accessed June 29, 2016.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Pettiway for his remarks. The intent of our article was to identify common challenges when prescribing opioids for chronic pain and offer tips to the provider struggling with how to do so safely. We hope these comments will offer additional clarity.

First, as general internists who are essentially “self-trained” in the management of chronic pain, we fully acknowledge the importance of practical experience in learning how to prescribe opioids safely and effectively. Dr. Pettiway is correct that a dedicated physician who keeps up with the medical literature, attends relevant continuing medical education courses, and strives to provide deliberate, rational, and evidence-based care to his or her patients can do so effectively. However, the medical literature suggests that medical school training in the management of chronic pain is sparse; one review found that in 2011 only 5 out of 133 US medical schools required coursework on pain management, and only 13 offered it as an elective.1 Many primary care providers do feel unprepared to handle this challenge.

Additionally, Dr. Pettiway raises a good question about where misused prescription opioids originate and whether prescribers are responsible. The data show that the majority of misused prescription opioids are obtained from a family member or friend and not directly from a physician.2,3 However, this supply does generally originate from a prescription. Providers need to educate their patients about the risk for diversion, the need to keep pills safely hidden and locked away, and the importance of safely discarding unused supplies. Responsible prescribers need to anticipate these concerns and educate patients about them.

In summary, we firmly believe that primary care providers are capable of safe, effective, and responsible opioid prescribing and hope that our paper provides additional guidance on how to do so.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Pettiway for his remarks. The intent of our article was to identify common challenges when prescribing opioids for chronic pain and offer tips to the provider struggling with how to do so safely. We hope these comments will offer additional clarity.

First, as general internists who are essentially “self-trained” in the management of chronic pain, we fully acknowledge the importance of practical experience in learning how to prescribe opioids safely and effectively. Dr. Pettiway is correct that a dedicated physician who keeps up with the medical literature, attends relevant continuing medical education courses, and strives to provide deliberate, rational, and evidence-based care to his or her patients can do so effectively. However, the medical literature suggests that medical school training in the management of chronic pain is sparse; one review found that in 2011 only 5 out of 133 US medical schools required coursework on pain management, and only 13 offered it as an elective.1 Many primary care providers do feel unprepared to handle this challenge.

Additionally, Dr. Pettiway raises a good question about where misused prescription opioids originate and whether prescribers are responsible. The data show that the majority of misused prescription opioids are obtained from a family member or friend and not directly from a physician.2,3 However, this supply does generally originate from a prescription. Providers need to educate their patients about the risk for diversion, the need to keep pills safely hidden and locked away, and the importance of safely discarding unused supplies. Responsible prescribers need to anticipate these concerns and educate patients about them.

In summary, we firmly believe that primary care providers are capable of safe, effective, and responsible opioid prescribing and hope that our paper provides additional guidance on how to do so.

- Roehr B. US needs new strategy to help 116 million patients in chronic pain. BMJ 2011; 343:d4206.

- Becker WC, Tobin DG, Fiellin DA. Nonmedical use of opioid analgesics obtained directly from physicians: prevalence and correlates. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1034–1036.

- Substance Abuse and Mental health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm. Accessed June 29, 2016.

- Roehr B. US needs new strategy to help 116 million patients in chronic pain. BMJ 2011; 343:d4206.

- Becker WC, Tobin DG, Fiellin DA. Nonmedical use of opioid analgesics obtained directly from physicians: prevalence and correlates. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1034–1036.

- Substance Abuse and Mental health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.htm. Accessed June 29, 2016.

Prescribing opioids in primary care: Safely starting, monitoring, and stopping

Chronic pain affects an estimated 100 million Americans, at a cost of $635 billion each year in medical expenses, lost wages, and reduced productivity.1 It is often managed in primary care settings with opioids by clinicians who have little or no formal training in pain management.2,3 Some primary care providers may seek assistance from board-certified pain specialists, but with only four such experts for every 100,000 patients with chronic pain, primary care providers are typically on their own.4

Although opioids may help in some chronic pain syndromes, they also carry the risk of serious harm, including unintentional overdose and death. In 2009, unintentional drug overdoses, most commonly with opioids, surpassed motor vehicle accidents as the leading cause of accidental death in the United States.5 Additionally, nonmedical use of prescription drugs is the third most common category of drug abuse, after marijuana and alcohol.6

Unfortunately, clinicians cannot accurately predict future medication misuse.7 And while the potential harms of opioids are many, the long-term benefits are questionable.8,9

For these reasons, providers need to understand the indications for and potential benefits of opioids, as well as the potential harms and how to monitor their safe use. Also important to know is how and when to discontinue opioids while preserving the therapeutic relationship.

This paper offers practical strategies to primary care providers and their care teams on how to safely initiate, monitor, and discontinue chronic opioid therapy.

STARTING OPIOID THERAPY FOR CHRONIC PAIN

Guidelines recommend considering starting patients on opioid therapy when the benefits are likely to outweigh the risks, when pain is moderate to severe, and when other multimodal treatment strategies have not achieved functional goals.10 Unfortunately, few studies have examined or demonstrated long-term benefit, and those that did examine this outcome reported reduction of pain severity but did not assess functional improvement.9 Meanwhile, data are increasingly clear that long-term use increases the risk of harm, both acute (eg, overdose) and chronic (eg, osteoporosis), especially with high doses.

Tools have been developed to predict the risk of misuse,11–13 but few have been validated in primary care, where most opioids are prescribed. This limitation aside, consensus guidelines state that untreated substance use disorders, poorly controlled psychiatric disease, and erratic treatment adherence are contraindications to opioid therapy, at least until these other issues are treated.10

Faced with the benefit-harm conundrum, we recommend a generally conservative approach to opioid initiation. With long-term functional benefit questionable and toxicity relatively common, we are increasingly avoiding chronic opioid therapy in younger patients with chronic pain.

Empathize and partner with your patient

Chronic pain care can be fraught with frustration and mutual distrust between patient and provider.14 Empathy and a collaborative stance help signal to the patient that the provider has the patient’s best interest in mind,15 whether initiating or deciding not to initiate opioids.

Optimize nonopioid therapy

In light of the risks associated with chronic opioid therapy, the clinician is urged to review and optimize nonopioid therapy before starting a patient on opioid treatment, and to maintain this approach if opioid therapy is started. Whenever possible, nonopioid treatment should include disease-modifying therapy and nondrug modalities such as physical therapy.

Judicious use of adequately dosed analgesics such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be sufficient to achieve analgesic goals if not contraindicated, and in some patients the addition of a topical analgesic (eg, diclofenac gel, lidocaine patches), a tricyclic or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressant, an anticonvulsant (eg, gabapentin), or a combination of the above can effectively address underlying pain-generating mechanisms.16 As with opioids, the risks and benefits of nonopioid pharmacotherapy should be reviewed both at initiation and periodically thereafter.

Frame the opioid treatment plan as a ‘therapeutic trial’

Starting an opioid should be framed as a “therapeutic trial.” These drugs should be continued only if safe and effective, at the lowest effective dose, and as one component of a multimodal pain treatment plan. Concurrent use of nonpharmacologic therapies (eg, physical therapy, structured exercise, yoga, relaxation training, biofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy) and rational pharmacotherapy while promoting patient self-care is the standard of pain management called for by the Institute of Medicine.1

Set functional goals

We recommend clearly defining functional goals with each patient before starting therapy. These goals should be written into the treatment plan as a way for patient and provider to evaluate the effectiveness of chronic opioid therapy. A useful mnemonic to help identify such goals is SMART, an acronym for specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and time-bound. Specific goals will depend on pain severity, but examples could include being able to do grocery shopping without assistance, to play on the floor with grandchildren, or to engage in healthy exercise habits such as 20 minutes of moderately brisk walking 3 days per week.

Obtain informed consent, and document it thoroughly

Providers must communicate risks, potential benefits, and safe medication-taking practices, including how to safely store and dispose of unused opioids, and document this conversation clearly in the medical record. From a medicolegal perspective, if it wasn’t documented, it did not happen.17

Informed consent can be further advanced with the use of a controlled substance agreement that outlines the treatment plan as well as potential risks, benefits, and practice policies in a structured way. Most states now either recommend or mandate the use of such agreements.18

Controlled substance agreements give providers a greater sense of mastery and comfort when prescribing opioids,19 but they have important limitations. In particular, there is a lack of consensus on what the agreement should say and relatively weak evidence that these agreements are efficacious. Additionally, a poorly written agreement can be stigmatizing and can erode trust.20 However, we believe that when the agreement is written in an appropriate framework of safety at an appropriate level of health literacy and with a focus on shared decision-making, it can be very helpful and should be used.

Employ safe, rational pharmacotherapy

Considerations when choosing an opioid include its potency, onset of action, and half-life. Comorbid conditions (eg, advanced age,21 sleep-disordered breathing22) and concurrent medications (eg, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, muscle relaxants) also affect decisions about the formulation, starting dose, rapidity of titration, and ceiling dose. Risk of harm increases in patients with such comorbid factors, and it is prudent to start with lower doses of shorter-acting medications until patients can demonstrate safe use. Risk of unintentional overdose is higher with higher prescribed doses.23 Pharmacologically there is no analgesic dose ceiling, but we urge caution, particularly in opioid-naive patients.

A patient’s response to any particular opioid is idiosyncratic and variable. There are more than 100 known polymorphisms in the human opioid mu-receptor gene, and thus differences in receptor affinity and activation as well as in metabolism make it difficult to predict which opioid will work best for a particular patient.24 However, a less potent opioid receptor agonist with less addictive potential, such as tramadol or codeine, should generally be tried first before escalating to a riskier, more potent opioid such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, or morphine. This “analgesic ladder,” a concept introduced by the World Health Organization in 1986 to provide a framework for managing cancer pain, has been adapted to a variety of chronic pain syndromes.25

Methadone deserves special mention. A strongly lipophilic molecule with a long and variable half-life, it accumulates in fat,26 and long after the analgesic effect has worn off, methadone will still be present. Repeated dosing or rapid dose escalation in an attempt to achieve adequate analgesia may result in inadvertent overdose. Additionally, methadone can prolong the QT interval, and periodic electrocardiographic monitoring is recommended.27 For these reasons, we recommend avoiding the use of methadone in most cases unless the provider has significant experience, expertise, or support in the safe use of this medication.

Table 1 summarizes these recommendations.

MONITORING AND SAFETY

Providers must periodically reassess the safety and efficacy of chronic opioid therapy to be sure that it is still indicated.10 Since we cannot accurately predict which patients will suffer adverse reactions or demonstrate aberrant behaviors,7 it is important to be transparent and consistent with monitoring practices for all patients on chronic opioid therapy.17 By framing monitoring in terms of safety and employing it universally, providers can minimize miscommunication and accidental stigmatization.

Prescription monitoring programs

In 2002, Congress appropriated funding to the US Department of Justice to support prescription monitoring programs nationally.28 At the time of this writing, Missouri is the only state without an approved monitoring program.29

Although the design and function of the programs vary from state to state, they require pharmacies to collect and report data on controlled substances for individual patients and prescribers. These data are sometimes shared across state lines, and the programs enhance the capacity of regulatory and law enforcement agencies to analyze controlled substance use.

Prescribers can (and are sometimes required to) register for access in their state and use this resource to assess the opioid refill history of their patients. This powerful tool improves detection of “doctor-shopping” and other common scams.30

Additionally, recognizing that the risk of death from overdose increases as the total daily dose of opioids increases,23 some states provide data on their composite report expressing the morphine equivalent daily dose or daily morphine milligram equivalents of the opioids prescribed. This information is valuable to the busy clinician; at a glance the prescriber can quickly discern the total daily opioid dose and use that information to assess risk and manage change. Furthermore, some states restrict further dose escalation when the morphine equivalent daily dose exceeds a predetermined amount (typically 100 to 120 morphine milligram equivalents).

Tamper-resistant prescribing

To minimize the risk of prescription tampering, simple techniques such as writing out the number of tablets dispensed can help, and use of tamper-resistant prescription paper has been required for Medicaid recipients since 2008.31

When possible, we recommend products with abuse-deterrent properties. Although the science of abuse deterrence is relatively new and few products are labeled as such, a number of opioids are formulated to resist deformation, vaporization, dissolving, or other physical tampering. Additionally, some abuse-deterrent opioid formulations contain naloxone, which is released only when the drug is deformed in some way, thereby decreasing the user’s response to an abused substance or resulting in opioid withdrawal.32

Urine drug testing

Although complex and nuanced, guidelines recommend urine drug testing to confirm the presence or absence of prescribed and illicit substances in the body.10 There is no consensus on when or how often to test, but it should be done randomly and without forewarning to foil efforts to defeat testing such as provision of synthetic, adulterated, or substituted urine.

Providers underuse urine drug testing.33 We recommend that it be done at the start of opioid therapy, sporadically thereafter, when therapy is changed, and whenever the provider is concerned about possible aberrant drug use.

Understanding opioid metabolism, cross-reactivity, and the types of tests available will help avoid misinterpretation of results.34 For example, a positive “opiate” result in most screening immunoassay tests does not reflect oxycodone use, since tests for synthetic opioids often need to be ordered separately; the commonly used Cedia opiate assay cross-reacts with oxycodone at a concentration of 10,000 ng/mL only 3.1% of the time.35 Immunoassay screening tests are widely available, sensitive, inexpensive, and fast, but they are qualitative, have limited specificity, and are subject to false-positive and false-negative results.36 Table 2 outlines some common characteristics of substances on screening immunoassays, including reported causes of false-positive results.37–39

Confirmatory testing using gas chromatography or mass spectroscopy is more expensive and slower to process, but is highly sensitive and specific, quantitative, and useful when screening results are difficult to interpret.

Knowing how and when to order the right urine drug test and knowing how to interpret the results are skills prescribers should master.

DISCONTINUING OPIOIDS

When opioids are no longer safe or effective, they should be stopped. The decision can be difficult for both the patient and provider, and a certain degree of equanimity is needed to approach it rationally.

Strong indications for discontinuation

Respiratory depression, cognitive impairment, falls, and motor vehicle accidents mean harm is already apparent. At a minimum, dose reduction is warranted and discontinuation should be strongly considered. Similarly, overdose (intentional or accidental) and active suicidal ideation contraindicate ongoing opioid prescribing unless the ongoing risk can be decisively mitigated.

Certain aberrant behaviors such as prescription forgery or theft, threats of violence to obtain analgesics, and diversion (transfer of the drug to another person for nonmedical use) also warrant immediate discontinuation. Continuing to prescribe an opioid while knowing diversion is taking place may be a violation of federal or state law or both.40

Another reason to stop is failure to achieve the expected benefit from chronic opioid therapy (ie, agreed-upon functional goals) despite appropriate dose adjustment. In these cases, ongoing risk by definition outweighs observed benefit.

Relative indications for discontinuation

Opioid therapy has many potential adverse effects. Depending on the severity and duration of the symptom and its response to either dose reduction or adjunctive management, opioids may need to be discontinued.

For example, pruritus, constipation, urinary retention, nausea, sedation, and sexual dysfunction may all be reasons to stop chronic opioid therapy. Similarly, chronic opioid therapy may paradoxically worsen pain in some susceptible patients, a complication known as opioid-induced hyperalgesia; in these cases, tapering off opioids should be considered as well.41 Aberrant behaviors should prompt reconsideration of chronic opioid therapy; these include hazardous alcohol consumption, use of illicit drugs, pill hoarding, and use of opioids in a manner different than intended by the prescriber.

Another relative indication for discontinuation is receipt of controlled substances from other providers. A well-written controlled substance agreement and adequate counseling may help mitigate this risk; poor communication between providers, lack of integration of electronic medical record systems, urgent or emergency room care, and poor health literacy may all lead to redundant prescribing in some circumstances. While unintentional use of controlled substances from different providers is no less dangerous than intentional misuse, the specifics of each case need to be considered before opioids are reflexively discontinued.

How to discontinue opioids

In most cases, opioids should be tapered to reduce the risk and severity of withdrawal symptoms. Decreasing the dose by 10% of the original dose per week is usually well tolerated with minimal adverse effects.42 Tapering can be done much faster, and numerous rapid detoxification protocols are available. In general, a patient needs 20% of the previous day’s dose to prevent withdrawal symptoms.43

Withdrawal symptoms are rarely life-threatening but can be very uncomfortable. Some providers add clonidine to attenuate associated autonomic symptoms such as hypertension, nausea, cramps, diaphoresis, and tachycardia if they occur. Other adjunctive medications include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for body aches, antiemetics for nausea and vomiting, bismuth subsalicylate for diarrhea, and trazodone for insomnia.

It is unlawful for primary care physicians to use another opioid to treat symptoms of withdrawal in the outpatient setting unless it is issued through a federally certified narcotic treatment program or prescribed by a qualified clinician registered with the US Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine-naloxone.44

In some circumstances, it may be appropriate to abruptly discontinue opioids without a taper, such as when diversion is evident. However, a decision to discontinue opioids due to misuse should not equate to an automatic decision to terminate a patient from the practice. Instead, providers should use this opportunity to offer empathy and referral to drug treatment counseling and rehabilitation. A decision to discontinue opioids because they are no longer safe or effective does not mean that the patient’s pain is not real—it is “real” for them, even if caused by the pain of addiction—or that shared decision-making is no longer possible or appropriate.

Handling difficult conversations when discontinuing opioids

The conversation between patient and provider when discontinuing opioids can be difficult. Misaligned expectations of both parties, patient fear of uncontrolled pain, and provider concern about causing suffering are frequent contributing factors. Patients abusing prescription drugs may also have a stronger relationship with their medication than with their provider and may use manipulative strategies including overt hostility and threats to obtain a prescription. Providers need to maintain their composure to de-escalate these potentially upsetting confrontations.

Table 3 outlines some specific suggestions that may be helpful, including the following:

- Frame the discussion in terms of safety—opioids are being discontinued because the benefit no longer outweighs the risk

- Don’t debate your decision with the patient, but present your reasoning in a considered manner

- Focus on the appropriateness of the treatment and not on the patient’s character

- Avoid the use of labels (eg, “drug addict”)

- Emphasize your commitment to the patient’s well-being and an alternative treatment plan (ie, nonabandonment)

- Respond to emotional distress with empathy, but do not let that change your decision to discontinue opioids.

Finally, we strongly encourage providers to insist on being treated respectfully. When safety cannot be ensured, providers should remove themselves from the room until the patient can calm down or the provider can ask for assistance from colleagues.

Maintaining empathy by understanding grief

Discontinuing opioids may trigger in a patient an emotional response similar to grief. When considered in this framework, it may empower an otherwise frustrated provider to remain empathetic even in the midst of a difficult confrontation. Paralleling Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief,45 we propose a similar model we call the “five stages of opioid loss”; this model has been successfully used in the residency continuity clinic at the University of Connecticut as a training aid.