User login

What treatments relieve arthritis and fatigue associated with systemic lupus erythematosus?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine improve the arthritis associated with mild systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—producing a 50% reduction in arthritis flares and articular involvement—and have few adverse effects (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Methotrexate reduces arthralgias by as much as 79%, but produces adverse effects in up to 70% of patients (SOR: B, systematic review of RCTs with limited patient-oriented evidence).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids are often used for SLE joint pain (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce arthritis symptoms by about 35% (SOR: B, RCTs with inconsistent evidence).

Abatacept and dehydroepiandrosterone don’t produce clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue associated with SLE, and abatacept causes significant adverse effects (SOR: B, posthoc analysis of a single RCT).

Aerobic exercise may help fatigue (SOR: B, systematic review with inconsistent evidence).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

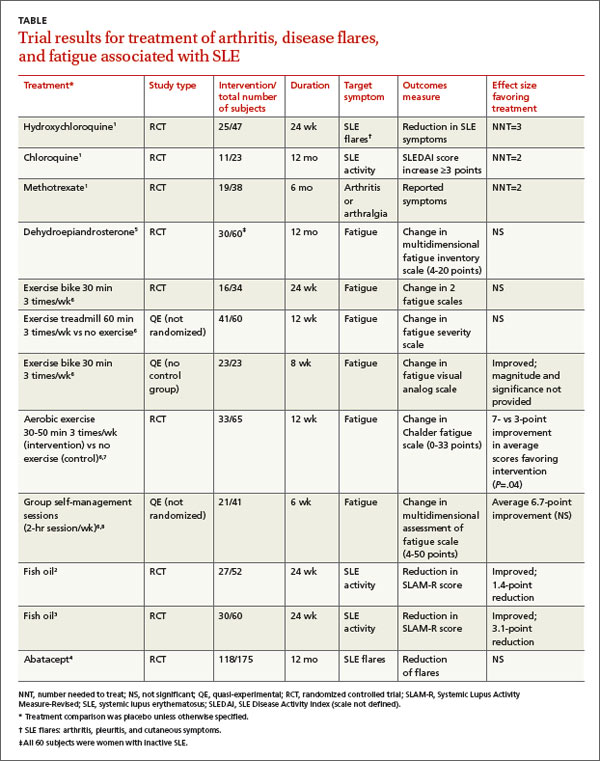

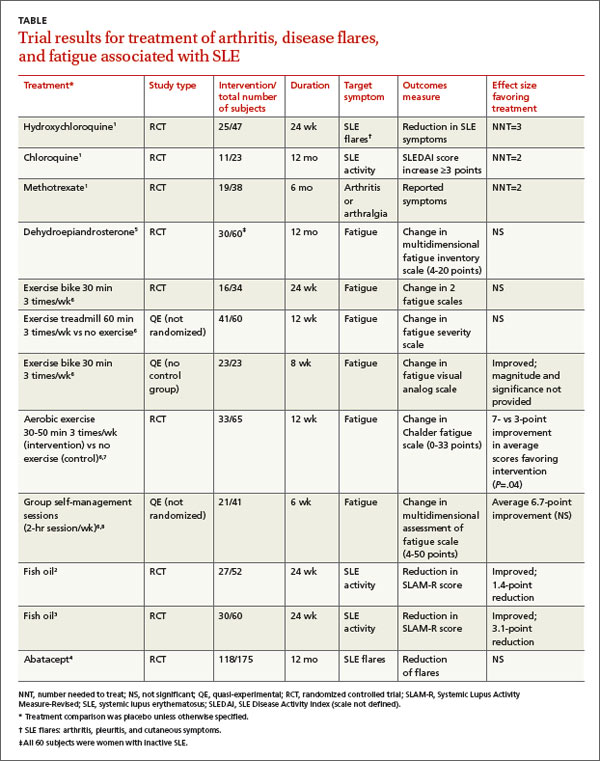

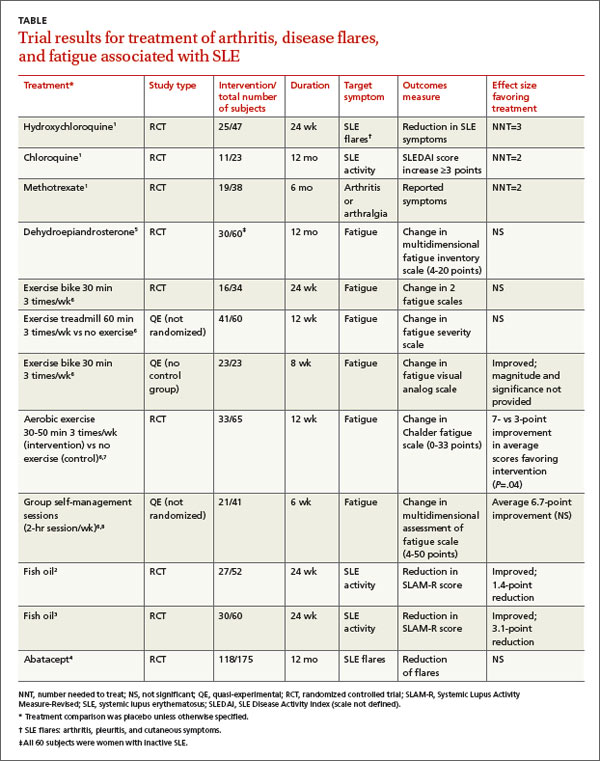

A systematic review of pharmacotherapy for joint pain in patients with SLE found 4 poor-quality RCTs that evaluated hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and methotrexate.1 Of the 2 studies that examined the effect of hydroxychloroquine, one (47 patients) showed a statistically significant 50% reduction in SLE flares (including arthritis, pleuritis, and cutaneous symptoms) over 24 weeks in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared with placebo (TABLE1-8). The second study (71 subjects) found a nonquantified decrease in self-reported pain when hydroxychloroquine was compared with placebo, although some of the patients were also taking prednisone (10 mg/d).

An RCT that evaluated the effect of chloroquine showed a statistically significant reduction in unspecified “articular involvement” compared with placebo.

The fourth RCT, assessing methotrexate, found a statistically significant reduction by as much as 79% in patients with residual arthritis or arthralgia at 6 months compared with placebo, although 70% of patients taking methotrexate developed significant adverse effects, including infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevated transaminases compared with 14% on placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=2).

The authors of the review noted that consensus opinion holds that oral corticosteroids and NSAIDs reduce SLE-associated joint pain, but they found no studies that objectively evaluated either of these interventions.1

Fish oil also helps arthritis

Two RCTs on the effects of 3 g/d of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (fish oil) for 24 weeks in SLE patients with mild disease found a reduction in Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R) scores.2,3 SLAM-R is a validated measure of SLE disease activity, rated on a scale from 0 to 81, including 23 clinical and 7 laboratory manifestations of disease.

In the first study (52 subjects), disease activity decreased from an average SLAM-R score of 6.1 at baseline to 4.7 (P<.05). The second study (60 subjects) found a similar reduction in mean SLAM-R scores from 9.4 to 6.3 (P<.001) and joint pain scores from 1.27 to 0.83 (P=.047).

Drug treatments don’t significantly relieve fatigue

An industry-sponsored RCT that compared abatacept with placebo found improvements in fatigue that weren’t clinically meaningful in posthoc analysis (-9.45 points difference on a self-reported 0-to-100 visual analog scale; 95% confidence interval, -17.65 to -1.25, with a 10-point reduction considered to be clinically meaningful). Abatacept also had a high rate of serious adverse events, including facial edema, polyneuropathy, and serious infections (24/121 with abatacept vs 4/59 placebo; NNH=8).4

Another RCT found no effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue in women with inactive SLE.5

Nondrug treatments for fatigue produce mixed results

Studies of nondrug treatment of SLE-associated fatigue show inconsistent results. A systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for fatigue in several chronic diseases found 2 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental studies that included 324 patients with SLE.6 Of 4 studies that evaluated the effect of exercise, 2 showed improvement and 2 didn’t. Neither group self-management nor relaxation therapy and telephone counseling significantly relieved fatigue.6-8 A small RCT (24 patients) found no benefit for acupuncture over sham needling in treating pain and fatigue in SLE.9

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology guideline for referral and management of SLE states that “NSAIDs are sometimes helpful for control of fever, arthritis, and mild serositis. Antimalarial agents (eg, hydroxychloroquine) are useful for skin and joint manifestations of SLE, for preventing flares, and for other constitutional symptoms of the disease. They may also reduce fatigue.”10

The European League Against Rheumatism recommends antimalarials or glucocorticoids to treat patients with SLE without major organ manifestations. They also say clinicians may try NSAIDs for limited periods of time in patients at low risk for the drugs’ complications.11

1. Madhok R, Wu O. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Evid. 2009;7:1123.

2. Duffy EM, Meenagh GK, McMillan SA, et al. The clinical effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fish oils and/ or copper in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1551-1556.

3. Wright SA, O’Prey FM, McHenry MT, et al. A randomised interventional trial of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids on endothelial function and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:841-848.

4. Merrill JT, Burgos-Vargas R, Westhovens R, et al. The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077-3087.

5. Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue and well-being in women with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1144-1147.

6. Neill J, Belan I, Reid K. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosis: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:617-635.

7. Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1050-1054.

8. Sohng KY. Effects of a self-management course for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:479-486.

9. Greco CM, Kao AH, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, et al. Acupuncture for systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot RCT feasibility and safety study. Lupus. 2008;17:1108-1116.

10. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1785-1796.

11. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al; Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:195-205.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine improve the arthritis associated with mild systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—producing a 50% reduction in arthritis flares and articular involvement—and have few adverse effects (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Methotrexate reduces arthralgias by as much as 79%, but produces adverse effects in up to 70% of patients (SOR: B, systematic review of RCTs with limited patient-oriented evidence).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids are often used for SLE joint pain (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce arthritis symptoms by about 35% (SOR: B, RCTs with inconsistent evidence).

Abatacept and dehydroepiandrosterone don’t produce clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue associated with SLE, and abatacept causes significant adverse effects (SOR: B, posthoc analysis of a single RCT).

Aerobic exercise may help fatigue (SOR: B, systematic review with inconsistent evidence).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of pharmacotherapy for joint pain in patients with SLE found 4 poor-quality RCTs that evaluated hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and methotrexate.1 Of the 2 studies that examined the effect of hydroxychloroquine, one (47 patients) showed a statistically significant 50% reduction in SLE flares (including arthritis, pleuritis, and cutaneous symptoms) over 24 weeks in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared with placebo (TABLE1-8). The second study (71 subjects) found a nonquantified decrease in self-reported pain when hydroxychloroquine was compared with placebo, although some of the patients were also taking prednisone (10 mg/d).

An RCT that evaluated the effect of chloroquine showed a statistically significant reduction in unspecified “articular involvement” compared with placebo.

The fourth RCT, assessing methotrexate, found a statistically significant reduction by as much as 79% in patients with residual arthritis or arthralgia at 6 months compared with placebo, although 70% of patients taking methotrexate developed significant adverse effects, including infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevated transaminases compared with 14% on placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=2).

The authors of the review noted that consensus opinion holds that oral corticosteroids and NSAIDs reduce SLE-associated joint pain, but they found no studies that objectively evaluated either of these interventions.1

Fish oil also helps arthritis

Two RCTs on the effects of 3 g/d of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (fish oil) for 24 weeks in SLE patients with mild disease found a reduction in Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R) scores.2,3 SLAM-R is a validated measure of SLE disease activity, rated on a scale from 0 to 81, including 23 clinical and 7 laboratory manifestations of disease.

In the first study (52 subjects), disease activity decreased from an average SLAM-R score of 6.1 at baseline to 4.7 (P<.05). The second study (60 subjects) found a similar reduction in mean SLAM-R scores from 9.4 to 6.3 (P<.001) and joint pain scores from 1.27 to 0.83 (P=.047).

Drug treatments don’t significantly relieve fatigue

An industry-sponsored RCT that compared abatacept with placebo found improvements in fatigue that weren’t clinically meaningful in posthoc analysis (-9.45 points difference on a self-reported 0-to-100 visual analog scale; 95% confidence interval, -17.65 to -1.25, with a 10-point reduction considered to be clinically meaningful). Abatacept also had a high rate of serious adverse events, including facial edema, polyneuropathy, and serious infections (24/121 with abatacept vs 4/59 placebo; NNH=8).4

Another RCT found no effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue in women with inactive SLE.5

Nondrug treatments for fatigue produce mixed results

Studies of nondrug treatment of SLE-associated fatigue show inconsistent results. A systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for fatigue in several chronic diseases found 2 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental studies that included 324 patients with SLE.6 Of 4 studies that evaluated the effect of exercise, 2 showed improvement and 2 didn’t. Neither group self-management nor relaxation therapy and telephone counseling significantly relieved fatigue.6-8 A small RCT (24 patients) found no benefit for acupuncture over sham needling in treating pain and fatigue in SLE.9

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology guideline for referral and management of SLE states that “NSAIDs are sometimes helpful for control of fever, arthritis, and mild serositis. Antimalarial agents (eg, hydroxychloroquine) are useful for skin and joint manifestations of SLE, for preventing flares, and for other constitutional symptoms of the disease. They may also reduce fatigue.”10

The European League Against Rheumatism recommends antimalarials or glucocorticoids to treat patients with SLE without major organ manifestations. They also say clinicians may try NSAIDs for limited periods of time in patients at low risk for the drugs’ complications.11

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine improve the arthritis associated with mild systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—producing a 50% reduction in arthritis flares and articular involvement—and have few adverse effects (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Methotrexate reduces arthralgias by as much as 79%, but produces adverse effects in up to 70% of patients (SOR: B, systematic review of RCTs with limited patient-oriented evidence).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids are often used for SLE joint pain (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce arthritis symptoms by about 35% (SOR: B, RCTs with inconsistent evidence).

Abatacept and dehydroepiandrosterone don’t produce clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue associated with SLE, and abatacept causes significant adverse effects (SOR: B, posthoc analysis of a single RCT).

Aerobic exercise may help fatigue (SOR: B, systematic review with inconsistent evidence).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of pharmacotherapy for joint pain in patients with SLE found 4 poor-quality RCTs that evaluated hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and methotrexate.1 Of the 2 studies that examined the effect of hydroxychloroquine, one (47 patients) showed a statistically significant 50% reduction in SLE flares (including arthritis, pleuritis, and cutaneous symptoms) over 24 weeks in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared with placebo (TABLE1-8). The second study (71 subjects) found a nonquantified decrease in self-reported pain when hydroxychloroquine was compared with placebo, although some of the patients were also taking prednisone (10 mg/d).

An RCT that evaluated the effect of chloroquine showed a statistically significant reduction in unspecified “articular involvement” compared with placebo.

The fourth RCT, assessing methotrexate, found a statistically significant reduction by as much as 79% in patients with residual arthritis or arthralgia at 6 months compared with placebo, although 70% of patients taking methotrexate developed significant adverse effects, including infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevated transaminases compared with 14% on placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=2).

The authors of the review noted that consensus opinion holds that oral corticosteroids and NSAIDs reduce SLE-associated joint pain, but they found no studies that objectively evaluated either of these interventions.1

Fish oil also helps arthritis

Two RCTs on the effects of 3 g/d of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (fish oil) for 24 weeks in SLE patients with mild disease found a reduction in Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R) scores.2,3 SLAM-R is a validated measure of SLE disease activity, rated on a scale from 0 to 81, including 23 clinical and 7 laboratory manifestations of disease.

In the first study (52 subjects), disease activity decreased from an average SLAM-R score of 6.1 at baseline to 4.7 (P<.05). The second study (60 subjects) found a similar reduction in mean SLAM-R scores from 9.4 to 6.3 (P<.001) and joint pain scores from 1.27 to 0.83 (P=.047).

Drug treatments don’t significantly relieve fatigue

An industry-sponsored RCT that compared abatacept with placebo found improvements in fatigue that weren’t clinically meaningful in posthoc analysis (-9.45 points difference on a self-reported 0-to-100 visual analog scale; 95% confidence interval, -17.65 to -1.25, with a 10-point reduction considered to be clinically meaningful). Abatacept also had a high rate of serious adverse events, including facial edema, polyneuropathy, and serious infections (24/121 with abatacept vs 4/59 placebo; NNH=8).4

Another RCT found no effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue in women with inactive SLE.5

Nondrug treatments for fatigue produce mixed results

Studies of nondrug treatment of SLE-associated fatigue show inconsistent results. A systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for fatigue in several chronic diseases found 2 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental studies that included 324 patients with SLE.6 Of 4 studies that evaluated the effect of exercise, 2 showed improvement and 2 didn’t. Neither group self-management nor relaxation therapy and telephone counseling significantly relieved fatigue.6-8 A small RCT (24 patients) found no benefit for acupuncture over sham needling in treating pain and fatigue in SLE.9

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology guideline for referral and management of SLE states that “NSAIDs are sometimes helpful for control of fever, arthritis, and mild serositis. Antimalarial agents (eg, hydroxychloroquine) are useful for skin and joint manifestations of SLE, for preventing flares, and for other constitutional symptoms of the disease. They may also reduce fatigue.”10

The European League Against Rheumatism recommends antimalarials or glucocorticoids to treat patients with SLE without major organ manifestations. They also say clinicians may try NSAIDs for limited periods of time in patients at low risk for the drugs’ complications.11

1. Madhok R, Wu O. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Evid. 2009;7:1123.

2. Duffy EM, Meenagh GK, McMillan SA, et al. The clinical effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fish oils and/ or copper in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1551-1556.

3. Wright SA, O’Prey FM, McHenry MT, et al. A randomised interventional trial of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids on endothelial function and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:841-848.

4. Merrill JT, Burgos-Vargas R, Westhovens R, et al. The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077-3087.

5. Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue and well-being in women with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1144-1147.

6. Neill J, Belan I, Reid K. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosis: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:617-635.

7. Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1050-1054.

8. Sohng KY. Effects of a self-management course for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:479-486.

9. Greco CM, Kao AH, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, et al. Acupuncture for systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot RCT feasibility and safety study. Lupus. 2008;17:1108-1116.

10. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1785-1796.

11. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al; Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:195-205.

1. Madhok R, Wu O. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Evid. 2009;7:1123.

2. Duffy EM, Meenagh GK, McMillan SA, et al. The clinical effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fish oils and/ or copper in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1551-1556.

3. Wright SA, O’Prey FM, McHenry MT, et al. A randomised interventional trial of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids on endothelial function and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:841-848.

4. Merrill JT, Burgos-Vargas R, Westhovens R, et al. The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077-3087.

5. Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue and well-being in women with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1144-1147.

6. Neill J, Belan I, Reid K. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosis: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:617-635.

7. Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1050-1054.

8. Sohng KY. Effects of a self-management course for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:479-486.

9. Greco CM, Kao AH, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, et al. Acupuncture for systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot RCT feasibility and safety study. Lupus. 2008;17:1108-1116.

10. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1785-1796.

11. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al; Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:195-205.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the most effective diagnostic evaluation of streptococcal pharyngitis?

Standardized clinical decision rules, such as the Centor criteria, can identify patients with low likelihood of group A beta-hemolytic streptococ-cal (GABHS) pharyngitis who require no further evaluation or antibiotics (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on validated cohort studies). For patients at intermediate and higher risk by clinical prediction rules, a positive rapid anti-gen detection (RAD) test is highly specific for GABHS (SOR: A, based on systematic reviews of diagnostic trials).

A negative RAD test result, using the best technique, approaches the sensitivity of throat culture (SOR: B, based on retrospective cohort studies). In children and populations with an increased prevalence of GABHS and GABHS complications, adding a backup throat culture reduces the risk of missing GABHS due to false-negative RAD results (SOR: C, based on expert opinion).

Evidence summary

In the US, GABHS is the cause of acute pharyn-gitis in 5% to 10% of adults and 15% to 30% of children. It is the only commonly occurring cause of pharyngitis with an indication for antibiotic therapy.1 The main benefit of antibiotic treatment in adults is earlier symptom relief—1 fewer day of fever and pain if antibiotics are begun within 3 days of onset.

Antibiotic treatment also reduces the incidence of acute rheumatic fever, which complicates 1 case per 100,000 in most of the US and Europe (relative risk reduction [RRR]=0.28).2 The risk of acute rheumatic fever is higher in some populaHawaiians (13–45 per 100,000).3 Treatment may also reduce suppurative complications (peritonsil-tions, particularly Native Americans and lar or retropharyngeal abscess), which occur in 1 case out of 1000.2,4

A systematic review of the diagnosis of GABHS evaluated the accuracy of history and physical exam elements.5 Clinical prediction rules based on selected symptoms and signs can identify patients at low risk for GABHS. The 4 Centor criteria (history of fever, anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudates, absence of cough) are well validated in adult populations ( Table 1 ), while other clinical prediction rules (such as McIssac) are validated in populations with children and adults ( Table 2 ). The number of criteria present determines the likelihood ratio (LR), with which to calculate the posttest probability of GABHS.

The usefulness of clinical prediction rules depends on knowing how prevalent GABHS is among cases of pharyngitis in a particular community. In a typical US adult population, GABHS comprises 5% to 10% of cases. The presence of only 1 Centor criterion would reduce the probability of GABHS pharyngitis to 2% to 3%, while meeting all 4 criteria would raise the probability to 25% to 40%, an intermediate value ( Table 1 ). If the prevalence of GABHS pharyngitis were 50%, as in some Native communities in Alaska, meeting all 4 criteria would predict an 86% probability of pharyngitis due to GABHS. Performing additional testing for patients with intermediate or high probability based on clinical prediction rules reduces the likelihood of unnecessary antibiotic treatment.1

A systematic review6 of RAD testing demonstrates that the newer techniques (optical immunoassay, chemiluminescent DNA probes) have a sensitivity of 80% to 90%, which compares closely with that of throat culture (90%–95%). Both have a specificity greater than 95%, so false-positive test results are uncommon (LR+ =16–19). Treatment based on a positive RAD test would result in few unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.1

A retrospective outcome study4 reviewed the frequency of suppurative complications of GABHS among 30,036 patients with pharyngitis diagnosed with either RAD testing or throat culture. Patients included adults and children in a primary care setting. Complication rates were identical. A prospective study of 465 suburban outpatients with pharyngitis assessed the accuracy of RAD diagnosis using throat culture as a reference. The RAD accuracy was 93% for pediatric patients and 97% for adults.5 In another retrospective review of RAD testing, investigators performed 11,427 RAD tests over 3 years in a private pediatric group. There were 8385 negative tests, among which follow-up cultures detected 200 (2.4%) that were positive for GABHS. In the second half of the study, a newer RAD test produced a false-negative rate of 1.4%.7 Because of the possibility of higher false-negative RAD test rates in some settings, unless the physician has ascertained that RAD testing is comparable to throat culture in their own setting, expert opinion recommends confirming a negative RAD test in children or adolescents with a throat culture.1 Patients at higher risk of GABHS or GABHS complications may also warrant throat culture back up of RAD testing.1

TABLE 1

Centor clinical prediction rules for diagnosis of GABHS (for adults)

| One point for each: History of fever, anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudates, absence of cough | |||||

| Points | LR+ | Pretest prevalence of GABHS (%) | |||

| 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Post-test probability of GABHS (%) | |||||

| 0 | 0.16 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 14 |

| 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 23 |

| 2 | 0.75 | 4 | 8 | 20 | 43 |

| 3 | 2.1 | 10 | 19 | 41 | 68 |

| 4 | 6.3 | 25 | 41 | 68 | 86 |

| GABHS, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus; LR+, positive likelihood ratio. | |||||

| Adapted from data in Ebell et al 2000.5 | |||||

TABLE 2

McIssac clinical prediction rules for diagnosis of GABHS (for adults and children)

| One point for each: History of fever (or measured temperature >38°C), absence of cough, tender anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar swelling or exudates, age <15. Subtract 1 point if age 45 or more | |||||

| Points | LR+ | Pretest prevalence of GABHS (%) | |||

| 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Post-test probability of GABHS (%) | |||||

| –1 or 0 | 0.05 | <1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 1 | 0.52 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 33 |

| 2 | 0.95 | 5 | 10 | 24 | 47 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 12 | 22 | 45 | 56 |

| 4 or 5 | 4.9 | 20 | 35 | 62 | 71 |

| GABHS, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus; LR+, positive likelihood ratio. | |||||

| Adapted from data in Ebell et al 2000.5 | |||||

Recommendations from others

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends that if the physician is unable to exclude the diagnosis of GABHS on epidemiological or clinical grounds, either RAD testing or throat culture should be done. A positive result warrants treatment for patients with signs and symptoms of acute pharyngitis. A negative RAD result for a child or adolescent should be confirmed by throat culture unless the physician has ascertained that the sensitivity of RAD testing and throat culture are comparable in his or her practice setting.1

The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends laboratory confirmation of GABHS pharyngitis in children with throat culture or RAD testing. If a patient suspected clinically of GABHS has a negative RAD test, a throat culture should be done. Since some experts believe RAD tests using optical immunoassay are sufficiently sensitive to be used without throat culture backup, physicians who wish to use them should validate them by comparison to throat culture in their practice.8

The RAD test helps to avoid overprescribing antibiotics

Peter Danis, MD

St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo

The patient with a sore throat presents a diagnostic dilemma at 8:00 in the evening or on a Sunday morning. Patients (or parents) want something done, and frequently request antibiotics. Most of the time, they appreciate accurate information on the likelihood of a sore throat being a “strep throat” and the benefit or lack of benefit of antibiotics. The “in-between” cases are the toughest to manage, and the RAD test gives us the additional information needed to avoid overprescribing antibiotics. Empathetic reassurance and symptomatic treatment still suffice in most cases.

1. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:113-125.

2. Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Special report: CDC principles of judicious antibiotics use. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:711-719.

3. Needham CA, McPherson KA, Webb KH. Streptococcal pharyngitis: impact of a high-sensitivity antigen test on physician outcome. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:3468-3473.

4. Webb KH, Needham CA, Kurtz SR. Use of a high-sensitivity rapid strep test without culture confirmation of negative results: 2 years’ experience. J Fam Pract 2000;49:34-43.

5. Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, Ives K, Carey M. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA 2000;284:2912-2918.

6. Stewart MH, Siff JE, Cydulka RK. Evaluation of the patient with sore throat, earache, and sinusitis: an evidence-based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1999;17:153-187.

7. Mayes T, Pichichero ME. Are follow-up throat cultures necessary when rapid antigen detection test are negative for group A streptococci?. Clin Pediatr 2001;40:191-195.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Group A streptococcal infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2003 Report of the committee on infectious diseases. 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003;573-584.

Standardized clinical decision rules, such as the Centor criteria, can identify patients with low likelihood of group A beta-hemolytic streptococ-cal (GABHS) pharyngitis who require no further evaluation or antibiotics (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on validated cohort studies). For patients at intermediate and higher risk by clinical prediction rules, a positive rapid anti-gen detection (RAD) test is highly specific for GABHS (SOR: A, based on systematic reviews of diagnostic trials).

A negative RAD test result, using the best technique, approaches the sensitivity of throat culture (SOR: B, based on retrospective cohort studies). In children and populations with an increased prevalence of GABHS and GABHS complications, adding a backup throat culture reduces the risk of missing GABHS due to false-negative RAD results (SOR: C, based on expert opinion).

Evidence summary

In the US, GABHS is the cause of acute pharyn-gitis in 5% to 10% of adults and 15% to 30% of children. It is the only commonly occurring cause of pharyngitis with an indication for antibiotic therapy.1 The main benefit of antibiotic treatment in adults is earlier symptom relief—1 fewer day of fever and pain if antibiotics are begun within 3 days of onset.

Antibiotic treatment also reduces the incidence of acute rheumatic fever, which complicates 1 case per 100,000 in most of the US and Europe (relative risk reduction [RRR]=0.28).2 The risk of acute rheumatic fever is higher in some populaHawaiians (13–45 per 100,000).3 Treatment may also reduce suppurative complications (peritonsil-tions, particularly Native Americans and lar or retropharyngeal abscess), which occur in 1 case out of 1000.2,4

A systematic review of the diagnosis of GABHS evaluated the accuracy of history and physical exam elements.5 Clinical prediction rules based on selected symptoms and signs can identify patients at low risk for GABHS. The 4 Centor criteria (history of fever, anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudates, absence of cough) are well validated in adult populations ( Table 1 ), while other clinical prediction rules (such as McIssac) are validated in populations with children and adults ( Table 2 ). The number of criteria present determines the likelihood ratio (LR), with which to calculate the posttest probability of GABHS.

The usefulness of clinical prediction rules depends on knowing how prevalent GABHS is among cases of pharyngitis in a particular community. In a typical US adult population, GABHS comprises 5% to 10% of cases. The presence of only 1 Centor criterion would reduce the probability of GABHS pharyngitis to 2% to 3%, while meeting all 4 criteria would raise the probability to 25% to 40%, an intermediate value ( Table 1 ). If the prevalence of GABHS pharyngitis were 50%, as in some Native communities in Alaska, meeting all 4 criteria would predict an 86% probability of pharyngitis due to GABHS. Performing additional testing for patients with intermediate or high probability based on clinical prediction rules reduces the likelihood of unnecessary antibiotic treatment.1

A systematic review6 of RAD testing demonstrates that the newer techniques (optical immunoassay, chemiluminescent DNA probes) have a sensitivity of 80% to 90%, which compares closely with that of throat culture (90%–95%). Both have a specificity greater than 95%, so false-positive test results are uncommon (LR+ =16–19). Treatment based on a positive RAD test would result in few unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.1

A retrospective outcome study4 reviewed the frequency of suppurative complications of GABHS among 30,036 patients with pharyngitis diagnosed with either RAD testing or throat culture. Patients included adults and children in a primary care setting. Complication rates were identical. A prospective study of 465 suburban outpatients with pharyngitis assessed the accuracy of RAD diagnosis using throat culture as a reference. The RAD accuracy was 93% for pediatric patients and 97% for adults.5 In another retrospective review of RAD testing, investigators performed 11,427 RAD tests over 3 years in a private pediatric group. There were 8385 negative tests, among which follow-up cultures detected 200 (2.4%) that were positive for GABHS. In the second half of the study, a newer RAD test produced a false-negative rate of 1.4%.7 Because of the possibility of higher false-negative RAD test rates in some settings, unless the physician has ascertained that RAD testing is comparable to throat culture in their own setting, expert opinion recommends confirming a negative RAD test in children or adolescents with a throat culture.1 Patients at higher risk of GABHS or GABHS complications may also warrant throat culture back up of RAD testing.1

TABLE 1

Centor clinical prediction rules for diagnosis of GABHS (for adults)

| One point for each: History of fever, anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudates, absence of cough | |||||

| Points | LR+ | Pretest prevalence of GABHS (%) | |||

| 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Post-test probability of GABHS (%) | |||||

| 0 | 0.16 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 14 |

| 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 23 |

| 2 | 0.75 | 4 | 8 | 20 | 43 |

| 3 | 2.1 | 10 | 19 | 41 | 68 |

| 4 | 6.3 | 25 | 41 | 68 | 86 |

| GABHS, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus; LR+, positive likelihood ratio. | |||||

| Adapted from data in Ebell et al 2000.5 | |||||

TABLE 2

McIssac clinical prediction rules for diagnosis of GABHS (for adults and children)

| One point for each: History of fever (or measured temperature >38°C), absence of cough, tender anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar swelling or exudates, age <15. Subtract 1 point if age 45 or more | |||||

| Points | LR+ | Pretest prevalence of GABHS (%) | |||

| 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Post-test probability of GABHS (%) | |||||

| –1 or 0 | 0.05 | <1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 1 | 0.52 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 33 |

| 2 | 0.95 | 5 | 10 | 24 | 47 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 12 | 22 | 45 | 56 |

| 4 or 5 | 4.9 | 20 | 35 | 62 | 71 |

| GABHS, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus; LR+, positive likelihood ratio. | |||||

| Adapted from data in Ebell et al 2000.5 | |||||

Recommendations from others

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends that if the physician is unable to exclude the diagnosis of GABHS on epidemiological or clinical grounds, either RAD testing or throat culture should be done. A positive result warrants treatment for patients with signs and symptoms of acute pharyngitis. A negative RAD result for a child or adolescent should be confirmed by throat culture unless the physician has ascertained that the sensitivity of RAD testing and throat culture are comparable in his or her practice setting.1

The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends laboratory confirmation of GABHS pharyngitis in children with throat culture or RAD testing. If a patient suspected clinically of GABHS has a negative RAD test, a throat culture should be done. Since some experts believe RAD tests using optical immunoassay are sufficiently sensitive to be used without throat culture backup, physicians who wish to use them should validate them by comparison to throat culture in their practice.8

The RAD test helps to avoid overprescribing antibiotics

Peter Danis, MD

St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo

The patient with a sore throat presents a diagnostic dilemma at 8:00 in the evening or on a Sunday morning. Patients (or parents) want something done, and frequently request antibiotics. Most of the time, they appreciate accurate information on the likelihood of a sore throat being a “strep throat” and the benefit or lack of benefit of antibiotics. The “in-between” cases are the toughest to manage, and the RAD test gives us the additional information needed to avoid overprescribing antibiotics. Empathetic reassurance and symptomatic treatment still suffice in most cases.

Standardized clinical decision rules, such as the Centor criteria, can identify patients with low likelihood of group A beta-hemolytic streptococ-cal (GABHS) pharyngitis who require no further evaluation or antibiotics (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on validated cohort studies). For patients at intermediate and higher risk by clinical prediction rules, a positive rapid anti-gen detection (RAD) test is highly specific for GABHS (SOR: A, based on systematic reviews of diagnostic trials).

A negative RAD test result, using the best technique, approaches the sensitivity of throat culture (SOR: B, based on retrospective cohort studies). In children and populations with an increased prevalence of GABHS and GABHS complications, adding a backup throat culture reduces the risk of missing GABHS due to false-negative RAD results (SOR: C, based on expert opinion).

Evidence summary

In the US, GABHS is the cause of acute pharyn-gitis in 5% to 10% of adults and 15% to 30% of children. It is the only commonly occurring cause of pharyngitis with an indication for antibiotic therapy.1 The main benefit of antibiotic treatment in adults is earlier symptom relief—1 fewer day of fever and pain if antibiotics are begun within 3 days of onset.

Antibiotic treatment also reduces the incidence of acute rheumatic fever, which complicates 1 case per 100,000 in most of the US and Europe (relative risk reduction [RRR]=0.28).2 The risk of acute rheumatic fever is higher in some populaHawaiians (13–45 per 100,000).3 Treatment may also reduce suppurative complications (peritonsil-tions, particularly Native Americans and lar or retropharyngeal abscess), which occur in 1 case out of 1000.2,4

A systematic review of the diagnosis of GABHS evaluated the accuracy of history and physical exam elements.5 Clinical prediction rules based on selected symptoms and signs can identify patients at low risk for GABHS. The 4 Centor criteria (history of fever, anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudates, absence of cough) are well validated in adult populations ( Table 1 ), while other clinical prediction rules (such as McIssac) are validated in populations with children and adults ( Table 2 ). The number of criteria present determines the likelihood ratio (LR), with which to calculate the posttest probability of GABHS.

The usefulness of clinical prediction rules depends on knowing how prevalent GABHS is among cases of pharyngitis in a particular community. In a typical US adult population, GABHS comprises 5% to 10% of cases. The presence of only 1 Centor criterion would reduce the probability of GABHS pharyngitis to 2% to 3%, while meeting all 4 criteria would raise the probability to 25% to 40%, an intermediate value ( Table 1 ). If the prevalence of GABHS pharyngitis were 50%, as in some Native communities in Alaska, meeting all 4 criteria would predict an 86% probability of pharyngitis due to GABHS. Performing additional testing for patients with intermediate or high probability based on clinical prediction rules reduces the likelihood of unnecessary antibiotic treatment.1

A systematic review6 of RAD testing demonstrates that the newer techniques (optical immunoassay, chemiluminescent DNA probes) have a sensitivity of 80% to 90%, which compares closely with that of throat culture (90%–95%). Both have a specificity greater than 95%, so false-positive test results are uncommon (LR+ =16–19). Treatment based on a positive RAD test would result in few unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.1

A retrospective outcome study4 reviewed the frequency of suppurative complications of GABHS among 30,036 patients with pharyngitis diagnosed with either RAD testing or throat culture. Patients included adults and children in a primary care setting. Complication rates were identical. A prospective study of 465 suburban outpatients with pharyngitis assessed the accuracy of RAD diagnosis using throat culture as a reference. The RAD accuracy was 93% for pediatric patients and 97% for adults.5 In another retrospective review of RAD testing, investigators performed 11,427 RAD tests over 3 years in a private pediatric group. There were 8385 negative tests, among which follow-up cultures detected 200 (2.4%) that were positive for GABHS. In the second half of the study, a newer RAD test produced a false-negative rate of 1.4%.7 Because of the possibility of higher false-negative RAD test rates in some settings, unless the physician has ascertained that RAD testing is comparable to throat culture in their own setting, expert opinion recommends confirming a negative RAD test in children or adolescents with a throat culture.1 Patients at higher risk of GABHS or GABHS complications may also warrant throat culture back up of RAD testing.1

TABLE 1

Centor clinical prediction rules for diagnosis of GABHS (for adults)

| One point for each: History of fever, anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudates, absence of cough | |||||

| Points | LR+ | Pretest prevalence of GABHS (%) | |||

| 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Post-test probability of GABHS (%) | |||||

| 0 | 0.16 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 14 |

| 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 23 |

| 2 | 0.75 | 4 | 8 | 20 | 43 |

| 3 | 2.1 | 10 | 19 | 41 | 68 |

| 4 | 6.3 | 25 | 41 | 68 | 86 |

| GABHS, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus; LR+, positive likelihood ratio. | |||||

| Adapted from data in Ebell et al 2000.5 | |||||

TABLE 2

McIssac clinical prediction rules for diagnosis of GABHS (for adults and children)

| One point for each: History of fever (or measured temperature >38°C), absence of cough, tender anterior cervical adenopathy, tonsillar swelling or exudates, age <15. Subtract 1 point if age 45 or more | |||||

| Points | LR+ | Pretest prevalence of GABHS (%) | |||

| 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Post-test probability of GABHS (%) | |||||

| –1 or 0 | 0.05 | <1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 1 | 0.52 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 33 |

| 2 | 0.95 | 5 | 10 | 24 | 47 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 12 | 22 | 45 | 56 |

| 4 or 5 | 4.9 | 20 | 35 | 62 | 71 |

| GABHS, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus; LR+, positive likelihood ratio. | |||||

| Adapted from data in Ebell et al 2000.5 | |||||

Recommendations from others

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends that if the physician is unable to exclude the diagnosis of GABHS on epidemiological or clinical grounds, either RAD testing or throat culture should be done. A positive result warrants treatment for patients with signs and symptoms of acute pharyngitis. A negative RAD result for a child or adolescent should be confirmed by throat culture unless the physician has ascertained that the sensitivity of RAD testing and throat culture are comparable in his or her practice setting.1

The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends laboratory confirmation of GABHS pharyngitis in children with throat culture or RAD testing. If a patient suspected clinically of GABHS has a negative RAD test, a throat culture should be done. Since some experts believe RAD tests using optical immunoassay are sufficiently sensitive to be used without throat culture backup, physicians who wish to use them should validate them by comparison to throat culture in their practice.8

The RAD test helps to avoid overprescribing antibiotics

Peter Danis, MD

St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo

The patient with a sore throat presents a diagnostic dilemma at 8:00 in the evening or on a Sunday morning. Patients (or parents) want something done, and frequently request antibiotics. Most of the time, they appreciate accurate information on the likelihood of a sore throat being a “strep throat” and the benefit or lack of benefit of antibiotics. The “in-between” cases are the toughest to manage, and the RAD test gives us the additional information needed to avoid overprescribing antibiotics. Empathetic reassurance and symptomatic treatment still suffice in most cases.

1. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:113-125.

2. Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Special report: CDC principles of judicious antibiotics use. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:711-719.

3. Needham CA, McPherson KA, Webb KH. Streptococcal pharyngitis: impact of a high-sensitivity antigen test on physician outcome. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:3468-3473.

4. Webb KH, Needham CA, Kurtz SR. Use of a high-sensitivity rapid strep test without culture confirmation of negative results: 2 years’ experience. J Fam Pract 2000;49:34-43.

5. Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, Ives K, Carey M. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA 2000;284:2912-2918.

6. Stewart MH, Siff JE, Cydulka RK. Evaluation of the patient with sore throat, earache, and sinusitis: an evidence-based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1999;17:153-187.

7. Mayes T, Pichichero ME. Are follow-up throat cultures necessary when rapid antigen detection test are negative for group A streptococci?. Clin Pediatr 2001;40:191-195.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Group A streptococcal infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2003 Report of the committee on infectious diseases. 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003;573-584.

1. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:113-125.

2. Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Special report: CDC principles of judicious antibiotics use. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:711-719.

3. Needham CA, McPherson KA, Webb KH. Streptococcal pharyngitis: impact of a high-sensitivity antigen test on physician outcome. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:3468-3473.

4. Webb KH, Needham CA, Kurtz SR. Use of a high-sensitivity rapid strep test without culture confirmation of negative results: 2 years’ experience. J Fam Pract 2000;49:34-43.

5. Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, Ives K, Carey M. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA 2000;284:2912-2918.

6. Stewart MH, Siff JE, Cydulka RK. Evaluation of the patient with sore throat, earache, and sinusitis: an evidence-based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1999;17:153-187.

7. Mayes T, Pichichero ME. Are follow-up throat cultures necessary when rapid antigen detection test are negative for group A streptococci?. Clin Pediatr 2001;40:191-195.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Group A streptococcal infections. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2003 Report of the committee on infectious diseases. 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003;573-584.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Do nasal decongestants relieve symptoms?

Oral and topical nasal decongestants result in a statistically significant improvement in subjective symptoms of nasal congestion and objective nasal airway resistance in adults’ common colds (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on randomized controlled trials). Evidence is lacking to support the use of decongestants in acute sinusitis.

Evidence summary

Nasal congestion is the most common symptom of the common cold, and hundreds of millions of dollars are spent annually on decongestants. A Cochrane review of 4 randomized controlled trials compared single doses of oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine.1 Included studies involved from 30 to 106 participants, were double-blinded and placebo-controlled, used either topical or oral decongestants for symptoms of less than 5 days’ duration, and measured either subjective or objective relief or adverse events. All 4 studies used nasal airway resistance as an objective measure of nasal congestion, and a combined symptom score as a subjective measure of relief. One study also administered a side-effect questionnaire.

In all studies, topical and oral decongestants were equally efficacious, producing a 13% reduction in subjective symptoms and a significant decrease in nasal airway resistance after 1 dose of decongestant. Only 1 study investigated repeated doses of decongestants and found no significant additional improvement from repeated doses over a 5-day period.

More studies are needed to evaluate efficacy of multiple doses. Clinical interpretation of these results must take into consideration that quality-of-life measures were not evaluated and that none of the studies included children under 12.

Limited data are available on decongestants in sinusitis. Most studies focused on the use of nasal corticosteroids. One placebo-controlled, randomized controlled trial evaluated the effect on mucociliary clearance from adding nasal saline, nasal steroids, or oxymetazoline to antibiotics in acute bacterial sinusitis.2 The group using oxymetazoline increased mucociliary clearance immediately (within 20 minutes). However, at 3 weeks, the improvement in mucociliary clearance in the oxymetazoline group was not significantly different than in the other groups.

An additional prospective, placebo-controlled study evaluated improvement in x-ray findings as well as subjective symptoms in acute sinusitis using phenoxymethyl-penicillin (penicillin V) in combination with oxymetazoline or placebo administered via a variety of nasal delivery systems.3 Oxymetazoline was not significantly different from placebo. Controlled prospective studies are lacking to support the use of decongestants in acute sinusitis.

Recommendations from others

Expert opinion from Current Clinical Topics in Infectious Diseases does not recommend the use of decongestants in sinusitis or the common cold in the absence of concurrent allergic rhinosinusitis.4 This recommendation is based on the lack of evidence regarding efficacy and the known rebound congestion associated with topical decongestants. If a decongestant is prescribed, the oral route is preferred, with the understanding of potential significant side effects of nervousness, insomnia, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Decongestants can do more harm than good

Russell W. Roberts, MD

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport

Never one to have been impressed with most of the current symptomatic treatments available for the common cold, I have for years been amazed at how quick the public is to purchase and repeatedly use these products.

While a judicious course of decongestants can ease the congestion, when misused they often cause significant harm and discomfort that is difficult to resolve. Patients whom I have assisted through successful discontinuance of topical nasal decongestants are among the most appreciative in my practice.

1. Taverner D, Bickford L, Draper M. Nasal decongestants for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001953. Updated quarterly.

2. Inanli S, Ozturk O, Korkmaz M, Tutkun A, Batman C. The effects of topical agents of fluticasone propionate, oxymetazoline, and 3% and 0.9% sodium chloride solutions on mucociliary clearance in the therapy of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in vivo. Laryngoscope 2002;112:320-325.

3. Wiklund L, Stierna P, Berglund R, Westrin KM, Tonnesson M. The efficacy of oxymetazoline administered with a nasal bellows container and combined with oral phenoxymethyl-penicillin in the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1994;515:57-64.

4. Chow AW. Acute sinusitis: current status of etiologies, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis 2001;21:31-63.

Oral and topical nasal decongestants result in a statistically significant improvement in subjective symptoms of nasal congestion and objective nasal airway resistance in adults’ common colds (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on randomized controlled trials). Evidence is lacking to support the use of decongestants in acute sinusitis.

Evidence summary

Nasal congestion is the most common symptom of the common cold, and hundreds of millions of dollars are spent annually on decongestants. A Cochrane review of 4 randomized controlled trials compared single doses of oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine.1 Included studies involved from 30 to 106 participants, were double-blinded and placebo-controlled, used either topical or oral decongestants for symptoms of less than 5 days’ duration, and measured either subjective or objective relief or adverse events. All 4 studies used nasal airway resistance as an objective measure of nasal congestion, and a combined symptom score as a subjective measure of relief. One study also administered a side-effect questionnaire.

In all studies, topical and oral decongestants were equally efficacious, producing a 13% reduction in subjective symptoms and a significant decrease in nasal airway resistance after 1 dose of decongestant. Only 1 study investigated repeated doses of decongestants and found no significant additional improvement from repeated doses over a 5-day period.

More studies are needed to evaluate efficacy of multiple doses. Clinical interpretation of these results must take into consideration that quality-of-life measures were not evaluated and that none of the studies included children under 12.

Limited data are available on decongestants in sinusitis. Most studies focused on the use of nasal corticosteroids. One placebo-controlled, randomized controlled trial evaluated the effect on mucociliary clearance from adding nasal saline, nasal steroids, or oxymetazoline to antibiotics in acute bacterial sinusitis.2 The group using oxymetazoline increased mucociliary clearance immediately (within 20 minutes). However, at 3 weeks, the improvement in mucociliary clearance in the oxymetazoline group was not significantly different than in the other groups.

An additional prospective, placebo-controlled study evaluated improvement in x-ray findings as well as subjective symptoms in acute sinusitis using phenoxymethyl-penicillin (penicillin V) in combination with oxymetazoline or placebo administered via a variety of nasal delivery systems.3 Oxymetazoline was not significantly different from placebo. Controlled prospective studies are lacking to support the use of decongestants in acute sinusitis.

Recommendations from others

Expert opinion from Current Clinical Topics in Infectious Diseases does not recommend the use of decongestants in sinusitis or the common cold in the absence of concurrent allergic rhinosinusitis.4 This recommendation is based on the lack of evidence regarding efficacy and the known rebound congestion associated with topical decongestants. If a decongestant is prescribed, the oral route is preferred, with the understanding of potential significant side effects of nervousness, insomnia, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Decongestants can do more harm than good

Russell W. Roberts, MD

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport

Never one to have been impressed with most of the current symptomatic treatments available for the common cold, I have for years been amazed at how quick the public is to purchase and repeatedly use these products.

While a judicious course of decongestants can ease the congestion, when misused they often cause significant harm and discomfort that is difficult to resolve. Patients whom I have assisted through successful discontinuance of topical nasal decongestants are among the most appreciative in my practice.

Oral and topical nasal decongestants result in a statistically significant improvement in subjective symptoms of nasal congestion and objective nasal airway resistance in adults’ common colds (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on randomized controlled trials). Evidence is lacking to support the use of decongestants in acute sinusitis.

Evidence summary

Nasal congestion is the most common symptom of the common cold, and hundreds of millions of dollars are spent annually on decongestants. A Cochrane review of 4 randomized controlled trials compared single doses of oxymetazoline, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine.1 Included studies involved from 30 to 106 participants, were double-blinded and placebo-controlled, used either topical or oral decongestants for symptoms of less than 5 days’ duration, and measured either subjective or objective relief or adverse events. All 4 studies used nasal airway resistance as an objective measure of nasal congestion, and a combined symptom score as a subjective measure of relief. One study also administered a side-effect questionnaire.

In all studies, topical and oral decongestants were equally efficacious, producing a 13% reduction in subjective symptoms and a significant decrease in nasal airway resistance after 1 dose of decongestant. Only 1 study investigated repeated doses of decongestants and found no significant additional improvement from repeated doses over a 5-day period.

More studies are needed to evaluate efficacy of multiple doses. Clinical interpretation of these results must take into consideration that quality-of-life measures were not evaluated and that none of the studies included children under 12.

Limited data are available on decongestants in sinusitis. Most studies focused on the use of nasal corticosteroids. One placebo-controlled, randomized controlled trial evaluated the effect on mucociliary clearance from adding nasal saline, nasal steroids, or oxymetazoline to antibiotics in acute bacterial sinusitis.2 The group using oxymetazoline increased mucociliary clearance immediately (within 20 minutes). However, at 3 weeks, the improvement in mucociliary clearance in the oxymetazoline group was not significantly different than in the other groups.

An additional prospective, placebo-controlled study evaluated improvement in x-ray findings as well as subjective symptoms in acute sinusitis using phenoxymethyl-penicillin (penicillin V) in combination with oxymetazoline or placebo administered via a variety of nasal delivery systems.3 Oxymetazoline was not significantly different from placebo. Controlled prospective studies are lacking to support the use of decongestants in acute sinusitis.

Recommendations from others

Expert opinion from Current Clinical Topics in Infectious Diseases does not recommend the use of decongestants in sinusitis or the common cold in the absence of concurrent allergic rhinosinusitis.4 This recommendation is based on the lack of evidence regarding efficacy and the known rebound congestion associated with topical decongestants. If a decongestant is prescribed, the oral route is preferred, with the understanding of potential significant side effects of nervousness, insomnia, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Decongestants can do more harm than good

Russell W. Roberts, MD

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport

Never one to have been impressed with most of the current symptomatic treatments available for the common cold, I have for years been amazed at how quick the public is to purchase and repeatedly use these products.

While a judicious course of decongestants can ease the congestion, when misused they often cause significant harm and discomfort that is difficult to resolve. Patients whom I have assisted through successful discontinuance of topical nasal decongestants are among the most appreciative in my practice.

1. Taverner D, Bickford L, Draper M. Nasal decongestants for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001953. Updated quarterly.

2. Inanli S, Ozturk O, Korkmaz M, Tutkun A, Batman C. The effects of topical agents of fluticasone propionate, oxymetazoline, and 3% and 0.9% sodium chloride solutions on mucociliary clearance in the therapy of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in vivo. Laryngoscope 2002;112:320-325.

3. Wiklund L, Stierna P, Berglund R, Westrin KM, Tonnesson M. The efficacy of oxymetazoline administered with a nasal bellows container and combined with oral phenoxymethyl-penicillin in the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1994;515:57-64.

4. Chow AW. Acute sinusitis: current status of etiologies, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis 2001;21:31-63.

1. Taverner D, Bickford L, Draper M. Nasal decongestants for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001953. Updated quarterly.

2. Inanli S, Ozturk O, Korkmaz M, Tutkun A, Batman C. The effects of topical agents of fluticasone propionate, oxymetazoline, and 3% and 0.9% sodium chloride solutions on mucociliary clearance in the therapy of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in vivo. Laryngoscope 2002;112:320-325.

3. Wiklund L, Stierna P, Berglund R, Westrin KM, Tonnesson M. The efficacy of oxymetazoline administered with a nasal bellows container and combined with oral phenoxymethyl-penicillin in the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1994;515:57-64.

4. Chow AW. Acute sinusitis: current status of etiologies, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis 2001;21:31-63.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network