User login

What makes a quality “quality measure”?

The future of health care is value-based care. If Value equals Quality divided by Cost, then a defined, validated way to measure Quality is paramount to that equation. (Fortunately, Cost comes with convenient measurement units called dollars.) Payers now are asking health care providers to shift from a fee-for-service to a value-based reimbursement structure to encourage providers to deliver the best care at the lowest cost. Providers who can embrace this data-driven paradigm will succeed in this new environment.

So how do we define high-quality care? What makes a good quality measure? How do you actually measure what happens in a clinical encounter that impacts health outcomes?

To answer these questions, organizations have constructed standardized clinical quality measures. Clinical quality measures facilitate value-based care by providing a metric on which to measure a patient’s quality of care. They can be used 1) to decrease the overuse, underuse, and misuse of health care services and 2) to measure patient engagement and satisfaction with care.

What are quality measures?

The Academy of Medicine (formerly named the Institute of Medicine) defines health care quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1

Clearly defined components and terminology. From a quantitative standpoint, quality measures must have a clearly defined numerator and denominator and appropriate inclusions, exclusions, and exceptions. These components need to be expressed clearly in terms of publicly available terminologies, such as ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes or SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms) terms. A measure that asks if “antihypertensive meds” have been given will not nearly be as specific as one that asks if “labetalol IV, or hydralazine IV, or nifedipine SL” has been administered. The decision to tie the data elements in a measure to administrative data, such as ICD codes, or to clinical data, such as SNOMED CT, also affects how these measures can be calculated.

Moving targets. The target of the measure also must carefully be considered. Quality measures can be used to evaluate care across the full range of health care settings—from individual providers, to care teams, to hospitals and hospital systems, to health plans. While some measures easily can be assigned to a specific provider, others are not as straightforward. For example, who gets assigned the cesarean delivery when a midwife turns the case over to an obstetrician?

Timeframe in outcomes measurement. The data infrastructure is currently set up to support measurement of immediate events, 30-day or 90-day episodes, and health insurance plan member years. Longer-term outcomes, such as over 5- and 10- year periods, are out of reach for most measures. To obtain an accurate view of the impact of medical interventions or disease conditions, however, it will be important to follow patients over time. For example, to know the failure rate of intrauterine systems, sterilization, or hormonal contraceptives, it is important to be able to track pregnancy occurrence during use of these methods for longer than 90 days. Failures can occur years after a method is initiated.

Another example is to create a performance measure focused on the overall improvement in quality of life and costs related to different treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding. How does the patient experience vary over time between treatment with hormonal contraception, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy? Which option is most “valuable” over time when the patient experience and the cost are assessed for more than a 90-day episode? These important questions need to be answered as we maneuver into a value-based health system.

Risk adjustment. Quality measures also may need to be risk adjusted. The “My patients are sicker” refrain must be accounted for with full transparency and based on the best available data. Quality measures can be adjusted using an Observed/Expected factor, which helps to account for complicated cases.2

Clearly, social and behavioral determinants of health also play a role in these adjustments, but it can be more challenging to acquire the data elements needed for those types of adjustments. Including these data enables us to evaluate health disparities between populations, both demographically and socioeconomically.3 This is important for future development of minority inclusive quality measures. Some racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer health outcomes from preventable and treatable diseases. Evidence shows that these groups have differences in access to health care, quality of care, and health measures, including life expectancy and maternal mortality. Access to clinical data through quality measures allows for these health disparities to be brought into quantifiable perspective and assists in the development of future incentive programs to combat health inequalities and provide improved delivery of care.

Read about how to develop quality measures

Developing quality measures

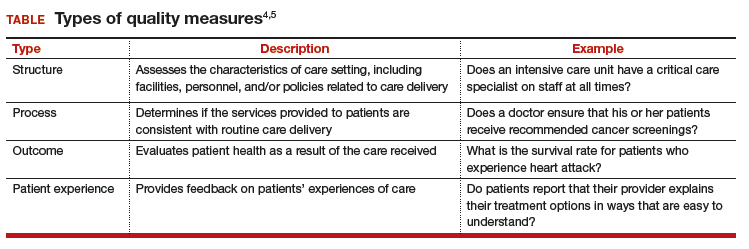

Quality measures generally fall into 4 broad categories: structure, process, outcome, and patient experience (TABLE).4,5 Quality measure development begins with an assessment of the evidence, which is usually derived from clinical guidelines that link a particular process, structure, or outcome with improved patient health or experience of care. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has developed a clinical practice guideline for screening, diagnosing, and managing gestational diabetes. The guideline addresses drug therapies, such as insulin, and alternative treatments, such as nutrition therapy. Much like the process for creating the guideline itself, translating the guideline into a quality measure requires a thoughtful, transparent, and well-defined process.

Role of the quality measure steward. Coordinating the process of translating evidence-based guidelines into quality measures requires a measure steward. Measure stewards usually are government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and/or for-profit companies. During the development process, the steward usually reaches out to additional stakeholders for feedback and consensus. Development process steps include:

- evaluation of the evidence, including the clinical practice guideline(s)

- consensus on the best measurement approach (consider the feasibility of the measurement and how it will be collected)

- development of detailed measure specifications (that is, what will be measured and how)

- feedback on the specifications from stakeholders, including professional societies and patient advocates

- testing of the measure logic and clinical validity against clinical data

- final approval by the measure steward.

Endorsement of quality measures. After a quality measure is developed, it is often endorsed by government agencies, professional societies, and/or consumer groups. Endorsement is a consensus-based process in which stakeholders evaluate a proposed measure based on established standards. Generally, stakeholders include health care professionals, consumers, payers, hospitals, health plans, and government agencies.

Evaluation of quality measures includes these important considerations:

- Are the necessary data fields available in a typical electronic health record (EHR) system?

- What is the data quality for those data fields?

- Can the measure be calculated reliably across different data sets or EHRs?

- Does the measure address one of the National Academy of Medicine quality properties? According to the academy, quality in the context of clinical care can be defined in terms of properties of effectiveness, equity, safety, efficiency, patient centeredness, and timeliness.1

Read about ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

In October 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the final Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Under this rule, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) was created, which was intended to drive “value” rather than “volume” in payment incentives. Measures are critical to defining value-based care. However, the law has limited or no impact on providers who do not care for Medicare patients.

Clinicians eligible to participate in MACRA must bill more than $90,000 a year in Medicare Part B allowed charges and provide care for more than 200 Medicare patients per year.6 This means that the MIPS largely overlooks ObGyns, as the bulk of our patients are insured either by private insurance or by Medicaid. However, maternity care spending is a significant part of both Medicaid and private insurers’ outlay, and both payers are actively considering using value-based financial models that will need to be fed by quality metrics. ACOG wants to be at the forefront of measure development for quality metrics that affect members and has committed resources to formation of a measure development team.

ACOG wants providers to be in control of how their practices are evaluated. For this reason, ACOG is focusing on measures that are based on clinical data entered by providers into an EHR at the point of care. At the same time, ACOG is cognizant of not increasing the documentation burden for providers. Understanding the quality of the data, as opposed to the quality of care, will be a fundamental task for the maternity care registry that ACOG is launching in 2018.

What can ObGyns do?

Quality measures are about more than just money. Public reporting of these measures on government and payer websites may influence public perception of a practice.7 The focus on patient-centered care means that patients have a voice in their care, financially as well as literally, so expect to see increased scrutiny of provider performance by patients as well as payers. One way to measure patient experience of treatments, symptoms, and quality of life is through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Assessing PROMs in routine care ensures that information only the patient can provide is collected and analyzed, thus further enhancing the delivery of care and evaluating how that care is impacting the lives of your patients.

The transition from fee-for-service to a value-based system will not happen overnight, but it will happen. This transition—from being paid for the quantity of documentation to the quality of documentation—will require some change management, rethinking of workflows, and better documentation tools (such as apps instead of EHR customization).

Many in the medical profession are actively exploring these changes and new developments. These changes are too important to leave to administrators, coders, scribes, app developers, and policy makers. Someone in your practice, hospital, or health system is working on these issues today. Tomorrow, you need to be at the table. The voices of practicing ObGyns are critical as we work to address the current challenging environment in which we spend more per capita than any other nation with far inferior results. Measures that matter to us and to our patients will help us provide better and more cost-effective care that payers and patients value.8

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Updated January 2, 2018. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Selecting quality and resource use measures: a decision guide for community quality collaboratives. Part 2. Introduction to measures of quality (continued). https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/perfmeasguide/perfmeaspt2a.html. Reviewed 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Thomas SB, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2050.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Types of quality measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/talkingquality/create/types.html. Reviewed 2011. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. Reviewed November 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Payment-Program/resource-library/QPP-Year-2-Final-Rule-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Published December 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz, A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1531–1541.

- Tooker J. The importance of measuring quality and performance in healthcare. MedGenMed. 2005;7(2):49.

The future of health care is value-based care. If Value equals Quality divided by Cost, then a defined, validated way to measure Quality is paramount to that equation. (Fortunately, Cost comes with convenient measurement units called dollars.) Payers now are asking health care providers to shift from a fee-for-service to a value-based reimbursement structure to encourage providers to deliver the best care at the lowest cost. Providers who can embrace this data-driven paradigm will succeed in this new environment.

So how do we define high-quality care? What makes a good quality measure? How do you actually measure what happens in a clinical encounter that impacts health outcomes?

To answer these questions, organizations have constructed standardized clinical quality measures. Clinical quality measures facilitate value-based care by providing a metric on which to measure a patient’s quality of care. They can be used 1) to decrease the overuse, underuse, and misuse of health care services and 2) to measure patient engagement and satisfaction with care.

What are quality measures?

The Academy of Medicine (formerly named the Institute of Medicine) defines health care quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1

Clearly defined components and terminology. From a quantitative standpoint, quality measures must have a clearly defined numerator and denominator and appropriate inclusions, exclusions, and exceptions. These components need to be expressed clearly in terms of publicly available terminologies, such as ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes or SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms) terms. A measure that asks if “antihypertensive meds” have been given will not nearly be as specific as one that asks if “labetalol IV, or hydralazine IV, or nifedipine SL” has been administered. The decision to tie the data elements in a measure to administrative data, such as ICD codes, or to clinical data, such as SNOMED CT, also affects how these measures can be calculated.

Moving targets. The target of the measure also must carefully be considered. Quality measures can be used to evaluate care across the full range of health care settings—from individual providers, to care teams, to hospitals and hospital systems, to health plans. While some measures easily can be assigned to a specific provider, others are not as straightforward. For example, who gets assigned the cesarean delivery when a midwife turns the case over to an obstetrician?

Timeframe in outcomes measurement. The data infrastructure is currently set up to support measurement of immediate events, 30-day or 90-day episodes, and health insurance plan member years. Longer-term outcomes, such as over 5- and 10- year periods, are out of reach for most measures. To obtain an accurate view of the impact of medical interventions or disease conditions, however, it will be important to follow patients over time. For example, to know the failure rate of intrauterine systems, sterilization, or hormonal contraceptives, it is important to be able to track pregnancy occurrence during use of these methods for longer than 90 days. Failures can occur years after a method is initiated.

Another example is to create a performance measure focused on the overall improvement in quality of life and costs related to different treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding. How does the patient experience vary over time between treatment with hormonal contraception, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy? Which option is most “valuable” over time when the patient experience and the cost are assessed for more than a 90-day episode? These important questions need to be answered as we maneuver into a value-based health system.

Risk adjustment. Quality measures also may need to be risk adjusted. The “My patients are sicker” refrain must be accounted for with full transparency and based on the best available data. Quality measures can be adjusted using an Observed/Expected factor, which helps to account for complicated cases.2

Clearly, social and behavioral determinants of health also play a role in these adjustments, but it can be more challenging to acquire the data elements needed for those types of adjustments. Including these data enables us to evaluate health disparities between populations, both demographically and socioeconomically.3 This is important for future development of minority inclusive quality measures. Some racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer health outcomes from preventable and treatable diseases. Evidence shows that these groups have differences in access to health care, quality of care, and health measures, including life expectancy and maternal mortality. Access to clinical data through quality measures allows for these health disparities to be brought into quantifiable perspective and assists in the development of future incentive programs to combat health inequalities and provide improved delivery of care.

Read about how to develop quality measures

Developing quality measures

Quality measures generally fall into 4 broad categories: structure, process, outcome, and patient experience (TABLE).4,5 Quality measure development begins with an assessment of the evidence, which is usually derived from clinical guidelines that link a particular process, structure, or outcome with improved patient health or experience of care. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has developed a clinical practice guideline for screening, diagnosing, and managing gestational diabetes. The guideline addresses drug therapies, such as insulin, and alternative treatments, such as nutrition therapy. Much like the process for creating the guideline itself, translating the guideline into a quality measure requires a thoughtful, transparent, and well-defined process.

Role of the quality measure steward. Coordinating the process of translating evidence-based guidelines into quality measures requires a measure steward. Measure stewards usually are government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and/or for-profit companies. During the development process, the steward usually reaches out to additional stakeholders for feedback and consensus. Development process steps include:

- evaluation of the evidence, including the clinical practice guideline(s)

- consensus on the best measurement approach (consider the feasibility of the measurement and how it will be collected)

- development of detailed measure specifications (that is, what will be measured and how)

- feedback on the specifications from stakeholders, including professional societies and patient advocates

- testing of the measure logic and clinical validity against clinical data

- final approval by the measure steward.

Endorsement of quality measures. After a quality measure is developed, it is often endorsed by government agencies, professional societies, and/or consumer groups. Endorsement is a consensus-based process in which stakeholders evaluate a proposed measure based on established standards. Generally, stakeholders include health care professionals, consumers, payers, hospitals, health plans, and government agencies.

Evaluation of quality measures includes these important considerations:

- Are the necessary data fields available in a typical electronic health record (EHR) system?

- What is the data quality for those data fields?

- Can the measure be calculated reliably across different data sets or EHRs?

- Does the measure address one of the National Academy of Medicine quality properties? According to the academy, quality in the context of clinical care can be defined in terms of properties of effectiveness, equity, safety, efficiency, patient centeredness, and timeliness.1

Read about ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

In October 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the final Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Under this rule, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) was created, which was intended to drive “value” rather than “volume” in payment incentives. Measures are critical to defining value-based care. However, the law has limited or no impact on providers who do not care for Medicare patients.

Clinicians eligible to participate in MACRA must bill more than $90,000 a year in Medicare Part B allowed charges and provide care for more than 200 Medicare patients per year.6 This means that the MIPS largely overlooks ObGyns, as the bulk of our patients are insured either by private insurance or by Medicaid. However, maternity care spending is a significant part of both Medicaid and private insurers’ outlay, and both payers are actively considering using value-based financial models that will need to be fed by quality metrics. ACOG wants to be at the forefront of measure development for quality metrics that affect members and has committed resources to formation of a measure development team.

ACOG wants providers to be in control of how their practices are evaluated. For this reason, ACOG is focusing on measures that are based on clinical data entered by providers into an EHR at the point of care. At the same time, ACOG is cognizant of not increasing the documentation burden for providers. Understanding the quality of the data, as opposed to the quality of care, will be a fundamental task for the maternity care registry that ACOG is launching in 2018.

What can ObGyns do?

Quality measures are about more than just money. Public reporting of these measures on government and payer websites may influence public perception of a practice.7 The focus on patient-centered care means that patients have a voice in their care, financially as well as literally, so expect to see increased scrutiny of provider performance by patients as well as payers. One way to measure patient experience of treatments, symptoms, and quality of life is through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Assessing PROMs in routine care ensures that information only the patient can provide is collected and analyzed, thus further enhancing the delivery of care and evaluating how that care is impacting the lives of your patients.

The transition from fee-for-service to a value-based system will not happen overnight, but it will happen. This transition—from being paid for the quantity of documentation to the quality of documentation—will require some change management, rethinking of workflows, and better documentation tools (such as apps instead of EHR customization).

Many in the medical profession are actively exploring these changes and new developments. These changes are too important to leave to administrators, coders, scribes, app developers, and policy makers. Someone in your practice, hospital, or health system is working on these issues today. Tomorrow, you need to be at the table. The voices of practicing ObGyns are critical as we work to address the current challenging environment in which we spend more per capita than any other nation with far inferior results. Measures that matter to us and to our patients will help us provide better and more cost-effective care that payers and patients value.8

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The future of health care is value-based care. If Value equals Quality divided by Cost, then a defined, validated way to measure Quality is paramount to that equation. (Fortunately, Cost comes with convenient measurement units called dollars.) Payers now are asking health care providers to shift from a fee-for-service to a value-based reimbursement structure to encourage providers to deliver the best care at the lowest cost. Providers who can embrace this data-driven paradigm will succeed in this new environment.

So how do we define high-quality care? What makes a good quality measure? How do you actually measure what happens in a clinical encounter that impacts health outcomes?

To answer these questions, organizations have constructed standardized clinical quality measures. Clinical quality measures facilitate value-based care by providing a metric on which to measure a patient’s quality of care. They can be used 1) to decrease the overuse, underuse, and misuse of health care services and 2) to measure patient engagement and satisfaction with care.

What are quality measures?

The Academy of Medicine (formerly named the Institute of Medicine) defines health care quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1

Clearly defined components and terminology. From a quantitative standpoint, quality measures must have a clearly defined numerator and denominator and appropriate inclusions, exclusions, and exceptions. These components need to be expressed clearly in terms of publicly available terminologies, such as ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes or SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms) terms. A measure that asks if “antihypertensive meds” have been given will not nearly be as specific as one that asks if “labetalol IV, or hydralazine IV, or nifedipine SL” has been administered. The decision to tie the data elements in a measure to administrative data, such as ICD codes, or to clinical data, such as SNOMED CT, also affects how these measures can be calculated.

Moving targets. The target of the measure also must carefully be considered. Quality measures can be used to evaluate care across the full range of health care settings—from individual providers, to care teams, to hospitals and hospital systems, to health plans. While some measures easily can be assigned to a specific provider, others are not as straightforward. For example, who gets assigned the cesarean delivery when a midwife turns the case over to an obstetrician?

Timeframe in outcomes measurement. The data infrastructure is currently set up to support measurement of immediate events, 30-day or 90-day episodes, and health insurance plan member years. Longer-term outcomes, such as over 5- and 10- year periods, are out of reach for most measures. To obtain an accurate view of the impact of medical interventions or disease conditions, however, it will be important to follow patients over time. For example, to know the failure rate of intrauterine systems, sterilization, or hormonal contraceptives, it is important to be able to track pregnancy occurrence during use of these methods for longer than 90 days. Failures can occur years after a method is initiated.

Another example is to create a performance measure focused on the overall improvement in quality of life and costs related to different treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding. How does the patient experience vary over time between treatment with hormonal contraception, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy? Which option is most “valuable” over time when the patient experience and the cost are assessed for more than a 90-day episode? These important questions need to be answered as we maneuver into a value-based health system.

Risk adjustment. Quality measures also may need to be risk adjusted. The “My patients are sicker” refrain must be accounted for with full transparency and based on the best available data. Quality measures can be adjusted using an Observed/Expected factor, which helps to account for complicated cases.2

Clearly, social and behavioral determinants of health also play a role in these adjustments, but it can be more challenging to acquire the data elements needed for those types of adjustments. Including these data enables us to evaluate health disparities between populations, both demographically and socioeconomically.3 This is important for future development of minority inclusive quality measures. Some racial and ethnic minority populations have poorer health outcomes from preventable and treatable diseases. Evidence shows that these groups have differences in access to health care, quality of care, and health measures, including life expectancy and maternal mortality. Access to clinical data through quality measures allows for these health disparities to be brought into quantifiable perspective and assists in the development of future incentive programs to combat health inequalities and provide improved delivery of care.

Read about how to develop quality measures

Developing quality measures

Quality measures generally fall into 4 broad categories: structure, process, outcome, and patient experience (TABLE).4,5 Quality measure development begins with an assessment of the evidence, which is usually derived from clinical guidelines that link a particular process, structure, or outcome with improved patient health or experience of care. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has developed a clinical practice guideline for screening, diagnosing, and managing gestational diabetes. The guideline addresses drug therapies, such as insulin, and alternative treatments, such as nutrition therapy. Much like the process for creating the guideline itself, translating the guideline into a quality measure requires a thoughtful, transparent, and well-defined process.

Role of the quality measure steward. Coordinating the process of translating evidence-based guidelines into quality measures requires a measure steward. Measure stewards usually are government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and/or for-profit companies. During the development process, the steward usually reaches out to additional stakeholders for feedback and consensus. Development process steps include:

- evaluation of the evidence, including the clinical practice guideline(s)

- consensus on the best measurement approach (consider the feasibility of the measurement and how it will be collected)

- development of detailed measure specifications (that is, what will be measured and how)

- feedback on the specifications from stakeholders, including professional societies and patient advocates

- testing of the measure logic and clinical validity against clinical data

- final approval by the measure steward.

Endorsement of quality measures. After a quality measure is developed, it is often endorsed by government agencies, professional societies, and/or consumer groups. Endorsement is a consensus-based process in which stakeholders evaluate a proposed measure based on established standards. Generally, stakeholders include health care professionals, consumers, payers, hospitals, health plans, and government agencies.

Evaluation of quality measures includes these important considerations:

- Are the necessary data fields available in a typical electronic health record (EHR) system?

- What is the data quality for those data fields?

- Can the measure be calculated reliably across different data sets or EHRs?

- Does the measure address one of the National Academy of Medicine quality properties? According to the academy, quality in the context of clinical care can be defined in terms of properties of effectiveness, equity, safety, efficiency, patient centeredness, and timeliness.1

Read about ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

ACOG’s role in developing quality measures

In October 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released the final Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Under this rule, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) was created, which was intended to drive “value” rather than “volume” in payment incentives. Measures are critical to defining value-based care. However, the law has limited or no impact on providers who do not care for Medicare patients.

Clinicians eligible to participate in MACRA must bill more than $90,000 a year in Medicare Part B allowed charges and provide care for more than 200 Medicare patients per year.6 This means that the MIPS largely overlooks ObGyns, as the bulk of our patients are insured either by private insurance or by Medicaid. However, maternity care spending is a significant part of both Medicaid and private insurers’ outlay, and both payers are actively considering using value-based financial models that will need to be fed by quality metrics. ACOG wants to be at the forefront of measure development for quality metrics that affect members and has committed resources to formation of a measure development team.

ACOG wants providers to be in control of how their practices are evaluated. For this reason, ACOG is focusing on measures that are based on clinical data entered by providers into an EHR at the point of care. At the same time, ACOG is cognizant of not increasing the documentation burden for providers. Understanding the quality of the data, as opposed to the quality of care, will be a fundamental task for the maternity care registry that ACOG is launching in 2018.

What can ObGyns do?

Quality measures are about more than just money. Public reporting of these measures on government and payer websites may influence public perception of a practice.7 The focus on patient-centered care means that patients have a voice in their care, financially as well as literally, so expect to see increased scrutiny of provider performance by patients as well as payers. One way to measure patient experience of treatments, symptoms, and quality of life is through patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Assessing PROMs in routine care ensures that information only the patient can provide is collected and analyzed, thus further enhancing the delivery of care and evaluating how that care is impacting the lives of your patients.

The transition from fee-for-service to a value-based system will not happen overnight, but it will happen. This transition—from being paid for the quantity of documentation to the quality of documentation—will require some change management, rethinking of workflows, and better documentation tools (such as apps instead of EHR customization).

Many in the medical profession are actively exploring these changes and new developments. These changes are too important to leave to administrators, coders, scribes, app developers, and policy makers. Someone in your practice, hospital, or health system is working on these issues today. Tomorrow, you need to be at the table. The voices of practicing ObGyns are critical as we work to address the current challenging environment in which we spend more per capita than any other nation with far inferior results. Measures that matter to us and to our patients will help us provide better and more cost-effective care that payers and patients value.8

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Updated January 2, 2018. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Selecting quality and resource use measures: a decision guide for community quality collaboratives. Part 2. Introduction to measures of quality (continued). https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/perfmeasguide/perfmeaspt2a.html. Reviewed 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Thomas SB, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2050.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Types of quality measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/talkingquality/create/types.html. Reviewed 2011. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. Reviewed November 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Payment-Program/resource-library/QPP-Year-2-Final-Rule-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Published December 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz, A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1531–1541.

- Tooker J. The importance of measuring quality and performance in healthcare. MedGenMed. 2005;7(2):49.

- National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Updated January 2, 2018. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Selecting quality and resource use measures: a decision guide for community quality collaboratives. Part 2. Introduction to measures of quality (continued). https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/perfmeasguide/perfmeaspt2a.html. Reviewed 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Thomas SB, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2050.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Types of quality measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/talkingquality/create/types.html. Reviewed 2011. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Understanding quality measurement. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html. Reviewed November 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality payment program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Payment-Program/resource-library/QPP-Year-2-Final-Rule-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Published December 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz, A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1531–1541.

- Tooker J. The importance of measuring quality and performance in healthcare. MedGenMed. 2005;7(2):49.

Read all parts of this series

PART 1 Value-based payment: What does it mean and how can ObGyns get out ahead

PART 2 What makes a “quality” quality measure?

PART 3 The role of patient-reported outcomes in women’s health

PART 4 It costs what?! How we can educate residents and students on how much things cost

Goodbye measures of data quantity, hello data quality measures of MACRA

Practicing clinical medicine is increasingly challenging. Besides the onslaught of new clinical information, we have credentialing, accreditation, certification, team-based care, and patient satisfaction that contribute to the complexity of current medical practice. At the heart of many of these challenges is the issue of accountability. Never has our work product as physicians been under such intense scrutiny as it is today.

To demonstrate proof of the care we have provided, we have enlisted a host of administrators, assistants, abstractors, and other helpers to decipher our work and demonstrate its value to professional organizations, boards, hospitals, insurers, and the government. They comb through our charts, decipher our handwriting and dictations, guesstimate our intentions, and sometimes devalue our care because we have not adequately documented what we have done. To solve this accountability problem, our government and the payer community have promoted the electronic health record (EHR) as the “single source of truth” for the care we provide.

This effort received a huge boost in 2009 with the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. HITECH authorized incentive payments through Medicare and Medicaid to health care providers that could demonstrate Meaningful Use (MU) of a certified EHR. This resulted in a boom in EHR purchases and installations.

By 2012, 71.8% of office-based physicians reported using some type of EHR system, up from 34.8% in 2007.1 In many respects this action was designed as a stimulus for the slow economy, but Congress also wanted some type of accountability that the money spent to subsidize EHR purchases was going to be well spent, and would hopefully have an impact on some of the serious health issues we face.

The initial stage of this MU program seemed to work out reasonably well. So, if a little is good, more must be better, right? Unfortunately, no. But, where did MU go wrong, and how is it being fixed? Contrary to popular belief, MU is not going away, it is being transformed. To help you navigate the tethered landscape of MU past and, more importantly, bring you up to speed on MU future (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 [MACRA]) and your payment incentives in this data-centric world, we address MU transformation in this article.

Where Meaningful Use stage 2 went wrong

MU stage 2 turned out to significantly increase the documentation burden on health care professionals. In addition, one of the tragic unintended consequences was that all available EHR development resources by vendors went toward meeting MU data capture requirements rather than to improving the usability and efficiency of the EHRs. Neither result has been well received by health care professionals.

Stage 3 of MU is now in place. It is an attempt to simplify the requirements and focus on quality, safety, interoperability, and patient engagement. See “Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications”. The current progression of MU stages is depicted in TABLE 1.2

Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications

Objective 1: Protect patient health information. Protect electronic health information created or maintained by the Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) through the implementation of appropriate technical, administrative, and physical safeguards.

Objective 2: Electronic prescribing. Eligible providers (EPs) must generate and transmit permissible prescriptions electronically, and eligible hospitals must generate and transmit permissible discharge prescriptions electronically.

Objective 3: Clinical decision support. Implement clinical decision support interventions focused on improving performance on high-priority health conditions.

Objective 4: Computerized provider order entry. Use computerized provider order entry for medication, laboratory, and diagnostic imaging orders directly entered by any licensed health care professional, credentialed medical assistant, or a medical staff member credentialed and performing the equivalent duties of a credentialed medical assistant, who can enter orders into the medical record per state, local, and professional guidelines.

Objective 5: Patient electronic access to health information. The EP provides patients (or patient-authorized representatives) with timely electronic access to their health information and patient-specific education.

Objective 6: Coordination of care through patient engagement. Use the CEHRT to engage with patients or their authorized representatives about the patient's care.

Objective 7: Health information exchange. The EP provides a summary of care record when transitioning or referring their patient to another setting of care, receives or retrieves a summary of care record upon the receipt of a transition or referral or upon the first patient encounter with a new patient, and incorporates summary of care information from other providers into their EHR using the functions of CEHRT.

Objective 8: Public health and clinical data registry reporting. The EP is in active engagement with a public health agency or clinical data registry to submit electronic public health data in a meaningful way using certified EHR technology, except where prohibited, and in accordance with applicable law and practice.

Reference

1. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 3. Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/30/2015-06685/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3#t-4. Accessed March 19, 2016.

Our new paradigm

Now that EHR implementation is fairly widespread, attention is focused on streamlining the reporting and documentation required for accountability, both from the data entry standpoint and the data analysis standpoint. Discrete data elements, entered by clinicians at the point of care, and downloaded directly from the EHR increasingly will be the way our patient care is assessed. Understanding this new paradigm is critical for both practice and professional viability.

Challenges in this new era

To understand the challenges ahead, we must first take a critical look at how physicians think about documentation, and what changes these models of documentation will have to undergo. Physicians are taught to think in complex models that we document as narratives or stories. While these models are composed of individual “elements” (patient age, due date, hemoglobin value, systolic blood pressure), the real information is in how these elements are related. Understanding a patient, a disease process, or a clinical workflow involves elements that must have context and relationships to be meaningful. Isolated hemoglobin or systolic blood pressure values tell us little, and may in fact obscure the forest for the trees. Physicians want to tell, and understand, the story.

However, an EHR is much more than a collection of narrative text documents. Entering data as discrete elements will allow each data element to be standardized, delegated, automated, analyzed, and monetized. In fact, these processes cannot be accomplished without the data being in this discrete form. While a common complaint about EHRs is that the “story” is hard to decipher, discrete elements are here to stay. Algorithms that can “read” a story and automatically populate these elements (known as natural language processing, or NLP) may someday allow us to go back to our dictations, but that day is frustratingly still far off.

Hello eCQMs

Up to now, physicians have relied on an army of abstractors, coders, billers, quality and safety helpers, and the like to read our notes and supply discrete data to the many clients who want to see accountability for our work. This process of course adds considerable cost to the health care system, and the data collected may not always supply accurate information. The gap between administrative data (gathered from the International Classificationof Diseases Ninth and Tenth revisions and Current Procedural Terminology [copyright American Medical Association] codes) and clinical reality is well documented.3–5

In an attempt to simplify this process, and to create a stronger connection to actual clinical data, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)6 is moving toward direct extraction of discrete data that have been entered by health care providers themselves.7 Using clinical data to report on quality metrics allows for improvement in risk adjustment as well as accuracy. Specific measures of this type have been designated eCQMs.

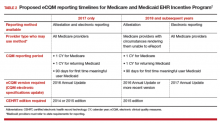

An eCQM is a format for a quality measure, utilizing data entered directly by health care professionals, and extracted directly from the EHR, without the need for additional personnel to review and abstract the chart. eCQMs rapidly are being phased into use for Medicare reimbursement; it is assumed that Medicaid and private payers soon will follow. Instead of payment solely for the quantity of documentation and intervention, we will soon also be paid for the quality of the care we provide (and document). TABLE 2 includes the proposed eCQM reporting timelines for Medicare and Medicaid.2

MACRA

eCQMs are a part of a larger federal effort to reform physician payments—MACRA. Over the past few years, there have been numerous federal programs to measure the quality and appropriateness of care. The Evaluation and Management (E&M) coding guidelines have been supplemented with factors for quality (Physician Quality Reporting System [PQRS]), resource use (the Value-based Payment Modifier), and EHR engagement (MU stages 1, 2, and 3). All of these programs are now being rolled up into a single program under MACRA.

MACRA has 2 distinct parts, known as the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and the Alternative Payment Model. MIPS keeps the underlying fee-for-service model but adds in a factor based on the following metrics:

- clinical quality (which will be based on eCQMs)

- resource use (a gauge of how many economic resources you use in comparison to your peers)

- clinical practice improvement (a measure of how well you are engaged in quality improvement, which includes capturing patient satisfaction data, and being part of a qualified clinical data registry is one way to demonstrate that engagement)

- meaningful use of EHR.

It is important to understand this last bulleted metric: MU is not going away (although that is a popular belief), it is just being transformed into MACRA, with the MU criteria simplified to emphasize a patient-centered medical record. Getting your patients involved through a portal and being able yourself to download, transmit, and accept patients’ data in electronic form are significant parts of MU. Vendors will continue to bear some of this burden, as their requirement to produce systems capable of these functions also increases their accountability.

Measurement and payment incentive

In the MIPS part of MACRA, the 4 factors of clinical quality, resource use, clinical practice improvement, and meaningful use of EHR will be combined in a formula to determine where each practitioner lies in comparison to his or her peers.

Now the bad news: Instead of receiving a bonus by meeting a benchmark, the bonus funds will be subtracted from those providers on the low end of the curve, and given to those at the top end. No matter how well the group does as a whole, no additional money will be available, and the bottom tier will be paying the bonuses of the top tier. The total pool of money to be distributed by CMS in the MIPS program will only grow by 0.5% per year for the foreseeable future. But MACRA does provide an alternative model for reimbursement, the Alternative Payment Model.

Alternative Payment Model

The Alternative Payment Model is basically an Accountable Care Organization—a group of providers agree to meet a certain standard of care (eCQMs again) and, in turn, receive a lump sum of money to deliver that care to a population. If there is some money left over at the end of a year, the group runs a profit. If not, they run a loss. One advantage of this model is that, under MACRA, the pool of money paid to “qualified” groups will increase at 5% per year for the next 5 years. This is certainly a better deal than the 0.5% increase of MIPS.

For specialists in general obstetrics and gynecology it may very well be that the volume of Medicare patients we see will be insufficient to participate meaningfully in either MIPS or the Alternative Payment Model. Regulations are still being crafted to exempt low-volume providers from the burdens associated with MACRA, and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) is working diligently to advocate for systems that will allow members to see Medicare patients without requiring the substantial investments these programs likely will require.

The EHR: The single source of truth

The push to make the EHR the single source of truth will streamline many peripheral activities on the health care delivery side as well as the payer side. These requirements will present a new challenge to health care professionals, however. No one went to medical school to become a data entry clerk. Still, EHRs show the promise to transform many aspects of health care delivery. They speed communication,8 reduce errors,9 and may well improve the safety and quality of care. There also is some evidence developing that they may slow the rising cost of health care.10

But they are also quickly becoming a major source of physician dissatisfaction,11 with an apparent dose-response relationship.12 Authors of a recent RAND study note, “the current state of EHR technology significantly worsened professional satisfaction in multiple ways, due to poor usability, time-consuming data entry, interference with face-to-face patient care, inefficient and less fulfilling work content, insufficient health information exchange, and degradation of clinical documentation.”13

This pushback against EHRs has beenheard all the way to Congress. The Senate recently has introduced the ‘‘Improving Health Information Technology Act.’’14 This bill includes proposals for rating EHR systems, decreasing “unnecessary” documentation, prohibiting “information blocking,” and increasing interoperability. It remains to be seen what specific actions will be included, and how this bill will fare in an election year.

So the practice of medicine continues to evolve, and our accountability obligations show no sign of slowing down. The vision of the EHR as a single source of truth—the tool to streamline both the data entry and the data analysis—is being pushed hard by the folks who control the purse strings. This certainly will change the way we conduct our work as physicians and health care professionals. There are innovative efforts being developed to ease this burden. Cloud-based object-oriented data models, independent “apps,” open Application Programming Interfaces, or other technologies may supplant the transactional billing platforms15 we now rely upon.

ACOG is engaged at many levels with these issues, and we will continue to keep the interests of our members and the health of our patients at the center of our efforts. But it seems that, at least for now, a move to capturing discrete data elements and relying on eCQMs for quality measurements will shape the foreseeable payment incentive future.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Hsiao CJ, Hing E, Ashman J. Trends in electronic health record system use among office-based physicians: United States, 2007–2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2014;(75):1–18.

- Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 3. Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/30/2015-06685/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3#t-4. Published March 10, 2015. Accessed March 19, 2016.

- Assareh H, Achat HM, Stubbs JM, Guevarra VM, Hill K.Incidence and variation of discrepancies in recording chronic conditions in Australian hospital administrative data. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147087.

- Williams DJ, Shah SS, Myers A, et al. Identifying pediatric community-acquired pneumonia hospitalizations: Accuracy of administrative billing codes. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(9):851–858.

- Liede A, Hernandez RK, Roth M, Calkins G, Larrabee K, Nicacio L. Validation of International Classification of Diseases coding for bone metastases in electronic health records using technology-enabled abstraction. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:441–448.

- Revisions of Quality Reporting Requirements for Specific Providers, Including Changes Related to the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program. Federal Register website. https://federalregister.gov/a/2015-19049. Published August 17, 2015. Accessed March 19, 2016.

- Panjamapirom A. Hospitals: Electronic CQM Reporting Has Arrived. Are You Ready? http://www.ihealthbeat.org/perspectives/2015/hospitals-electronic-cqm-reporting-has -arrived-are-you-ready. Published August 24, 2015. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Bernstein PS, Farinelli C, Merkatz IR. Using an electronic medical record to improve communication within a prenatal care network. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(3):607–612.

- George J, Bernstein PS. Using electronic medical records to reduce errors and risks in a prenatal network. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21(6):527–531.

- Adler-Milstein J, Salzberg C, Franz C, Orav EJ, Newhouse JP, Bates DW. Effect of electronic health records on health care costs: longitudinal comparative evidence from community practices. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):97–104.

- Pedulli L. Survey reveals widespread dissatisfaction with EHR systems. http://www.clinical-innovation.com/topics/ehr-emr/survey-reveals-widespread-dissatisfaction-ehr-systems. Published February 11, 2014. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100–e106.

- Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. RAND Corporation website. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR439.html. Published 2013. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Majority and Minority Staff of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. Summary of Improving Health Information Technology Act. http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Improving%20Health%20Information%20Technology%20Act%20--%20Summary.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2016.

- LetDoctorsbeDoctors.com. http://www.letdoctorsbedoctors.com/?sf21392355=1. Published 2016. Accessed March 18, 2016.

Practicing clinical medicine is increasingly challenging. Besides the onslaught of new clinical information, we have credentialing, accreditation, certification, team-based care, and patient satisfaction that contribute to the complexity of current medical practice. At the heart of many of these challenges is the issue of accountability. Never has our work product as physicians been under such intense scrutiny as it is today.

To demonstrate proof of the care we have provided, we have enlisted a host of administrators, assistants, abstractors, and other helpers to decipher our work and demonstrate its value to professional organizations, boards, hospitals, insurers, and the government. They comb through our charts, decipher our handwriting and dictations, guesstimate our intentions, and sometimes devalue our care because we have not adequately documented what we have done. To solve this accountability problem, our government and the payer community have promoted the electronic health record (EHR) as the “single source of truth” for the care we provide.

This effort received a huge boost in 2009 with the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. HITECH authorized incentive payments through Medicare and Medicaid to health care providers that could demonstrate Meaningful Use (MU) of a certified EHR. This resulted in a boom in EHR purchases and installations.

By 2012, 71.8% of office-based physicians reported using some type of EHR system, up from 34.8% in 2007.1 In many respects this action was designed as a stimulus for the slow economy, but Congress also wanted some type of accountability that the money spent to subsidize EHR purchases was going to be well spent, and would hopefully have an impact on some of the serious health issues we face.

The initial stage of this MU program seemed to work out reasonably well. So, if a little is good, more must be better, right? Unfortunately, no. But, where did MU go wrong, and how is it being fixed? Contrary to popular belief, MU is not going away, it is being transformed. To help you navigate the tethered landscape of MU past and, more importantly, bring you up to speed on MU future (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 [MACRA]) and your payment incentives in this data-centric world, we address MU transformation in this article.

Where Meaningful Use stage 2 went wrong

MU stage 2 turned out to significantly increase the documentation burden on health care professionals. In addition, one of the tragic unintended consequences was that all available EHR development resources by vendors went toward meeting MU data capture requirements rather than to improving the usability and efficiency of the EHRs. Neither result has been well received by health care professionals.

Stage 3 of MU is now in place. It is an attempt to simplify the requirements and focus on quality, safety, interoperability, and patient engagement. See “Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications”. The current progression of MU stages is depicted in TABLE 1.2

Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications

Objective 1: Protect patient health information. Protect electronic health information created or maintained by the Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) through the implementation of appropriate technical, administrative, and physical safeguards.

Objective 2: Electronic prescribing. Eligible providers (EPs) must generate and transmit permissible prescriptions electronically, and eligible hospitals must generate and transmit permissible discharge prescriptions electronically.

Objective 3: Clinical decision support. Implement clinical decision support interventions focused on improving performance on high-priority health conditions.

Objective 4: Computerized provider order entry. Use computerized provider order entry for medication, laboratory, and diagnostic imaging orders directly entered by any licensed health care professional, credentialed medical assistant, or a medical staff member credentialed and performing the equivalent duties of a credentialed medical assistant, who can enter orders into the medical record per state, local, and professional guidelines.

Objective 5: Patient electronic access to health information. The EP provides patients (or patient-authorized representatives) with timely electronic access to their health information and patient-specific education.

Objective 6: Coordination of care through patient engagement. Use the CEHRT to engage with patients or their authorized representatives about the patient's care.

Objective 7: Health information exchange. The EP provides a summary of care record when transitioning or referring their patient to another setting of care, receives or retrieves a summary of care record upon the receipt of a transition or referral or upon the first patient encounter with a new patient, and incorporates summary of care information from other providers into their EHR using the functions of CEHRT.

Objective 8: Public health and clinical data registry reporting. The EP is in active engagement with a public health agency or clinical data registry to submit electronic public health data in a meaningful way using certified EHR technology, except where prohibited, and in accordance with applicable law and practice.

Reference

1. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 3. Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/30/2015-06685/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3#t-4. Accessed March 19, 2016.

Our new paradigm

Now that EHR implementation is fairly widespread, attention is focused on streamlining the reporting and documentation required for accountability, both from the data entry standpoint and the data analysis standpoint. Discrete data elements, entered by clinicians at the point of care, and downloaded directly from the EHR increasingly will be the way our patient care is assessed. Understanding this new paradigm is critical for both practice and professional viability.

Challenges in this new era

To understand the challenges ahead, we must first take a critical look at how physicians think about documentation, and what changes these models of documentation will have to undergo. Physicians are taught to think in complex models that we document as narratives or stories. While these models are composed of individual “elements” (patient age, due date, hemoglobin value, systolic blood pressure), the real information is in how these elements are related. Understanding a patient, a disease process, or a clinical workflow involves elements that must have context and relationships to be meaningful. Isolated hemoglobin or systolic blood pressure values tell us little, and may in fact obscure the forest for the trees. Physicians want to tell, and understand, the story.

However, an EHR is much more than a collection of narrative text documents. Entering data as discrete elements will allow each data element to be standardized, delegated, automated, analyzed, and monetized. In fact, these processes cannot be accomplished without the data being in this discrete form. While a common complaint about EHRs is that the “story” is hard to decipher, discrete elements are here to stay. Algorithms that can “read” a story and automatically populate these elements (known as natural language processing, or NLP) may someday allow us to go back to our dictations, but that day is frustratingly still far off.

Hello eCQMs

Up to now, physicians have relied on an army of abstractors, coders, billers, quality and safety helpers, and the like to read our notes and supply discrete data to the many clients who want to see accountability for our work. This process of course adds considerable cost to the health care system, and the data collected may not always supply accurate information. The gap between administrative data (gathered from the International Classificationof Diseases Ninth and Tenth revisions and Current Procedural Terminology [copyright American Medical Association] codes) and clinical reality is well documented.3–5

In an attempt to simplify this process, and to create a stronger connection to actual clinical data, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)6 is moving toward direct extraction of discrete data that have been entered by health care providers themselves.7 Using clinical data to report on quality metrics allows for improvement in risk adjustment as well as accuracy. Specific measures of this type have been designated eCQMs.

An eCQM is a format for a quality measure, utilizing data entered directly by health care professionals, and extracted directly from the EHR, without the need for additional personnel to review and abstract the chart. eCQMs rapidly are being phased into use for Medicare reimbursement; it is assumed that Medicaid and private payers soon will follow. Instead of payment solely for the quantity of documentation and intervention, we will soon also be paid for the quality of the care we provide (and document). TABLE 2 includes the proposed eCQM reporting timelines for Medicare and Medicaid.2

MACRA

eCQMs are a part of a larger federal effort to reform physician payments—MACRA. Over the past few years, there have been numerous federal programs to measure the quality and appropriateness of care. The Evaluation and Management (E&M) coding guidelines have been supplemented with factors for quality (Physician Quality Reporting System [PQRS]), resource use (the Value-based Payment Modifier), and EHR engagement (MU stages 1, 2, and 3). All of these programs are now being rolled up into a single program under MACRA.

MACRA has 2 distinct parts, known as the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and the Alternative Payment Model. MIPS keeps the underlying fee-for-service model but adds in a factor based on the following metrics:

- clinical quality (which will be based on eCQMs)

- resource use (a gauge of how many economic resources you use in comparison to your peers)

- clinical practice improvement (a measure of how well you are engaged in quality improvement, which includes capturing patient satisfaction data, and being part of a qualified clinical data registry is one way to demonstrate that engagement)

- meaningful use of EHR.

It is important to understand this last bulleted metric: MU is not going away (although that is a popular belief), it is just being transformed into MACRA, with the MU criteria simplified to emphasize a patient-centered medical record. Getting your patients involved through a portal and being able yourself to download, transmit, and accept patients’ data in electronic form are significant parts of MU. Vendors will continue to bear some of this burden, as their requirement to produce systems capable of these functions also increases their accountability.

Measurement and payment incentive

In the MIPS part of MACRA, the 4 factors of clinical quality, resource use, clinical practice improvement, and meaningful use of EHR will be combined in a formula to determine where each practitioner lies in comparison to his or her peers.

Now the bad news: Instead of receiving a bonus by meeting a benchmark, the bonus funds will be subtracted from those providers on the low end of the curve, and given to those at the top end. No matter how well the group does as a whole, no additional money will be available, and the bottom tier will be paying the bonuses of the top tier. The total pool of money to be distributed by CMS in the MIPS program will only grow by 0.5% per year for the foreseeable future. But MACRA does provide an alternative model for reimbursement, the Alternative Payment Model.

Alternative Payment Model

The Alternative Payment Model is basically an Accountable Care Organization—a group of providers agree to meet a certain standard of care (eCQMs again) and, in turn, receive a lump sum of money to deliver that care to a population. If there is some money left over at the end of a year, the group runs a profit. If not, they run a loss. One advantage of this model is that, under MACRA, the pool of money paid to “qualified” groups will increase at 5% per year for the next 5 years. This is certainly a better deal than the 0.5% increase of MIPS.

For specialists in general obstetrics and gynecology it may very well be that the volume of Medicare patients we see will be insufficient to participate meaningfully in either MIPS or the Alternative Payment Model. Regulations are still being crafted to exempt low-volume providers from the burdens associated with MACRA, and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) is working diligently to advocate for systems that will allow members to see Medicare patients without requiring the substantial investments these programs likely will require.

The EHR: The single source of truth

The push to make the EHR the single source of truth will streamline many peripheral activities on the health care delivery side as well as the payer side. These requirements will present a new challenge to health care professionals, however. No one went to medical school to become a data entry clerk. Still, EHRs show the promise to transform many aspects of health care delivery. They speed communication,8 reduce errors,9 and may well improve the safety and quality of care. There also is some evidence developing that they may slow the rising cost of health care.10

But they are also quickly becoming a major source of physician dissatisfaction,11 with an apparent dose-response relationship.12 Authors of a recent RAND study note, “the current state of EHR technology significantly worsened professional satisfaction in multiple ways, due to poor usability, time-consuming data entry, interference with face-to-face patient care, inefficient and less fulfilling work content, insufficient health information exchange, and degradation of clinical documentation.”13

This pushback against EHRs has beenheard all the way to Congress. The Senate recently has introduced the ‘‘Improving Health Information Technology Act.’’14 This bill includes proposals for rating EHR systems, decreasing “unnecessary” documentation, prohibiting “information blocking,” and increasing interoperability. It remains to be seen what specific actions will be included, and how this bill will fare in an election year.

So the practice of medicine continues to evolve, and our accountability obligations show no sign of slowing down. The vision of the EHR as a single source of truth—the tool to streamline both the data entry and the data analysis—is being pushed hard by the folks who control the purse strings. This certainly will change the way we conduct our work as physicians and health care professionals. There are innovative efforts being developed to ease this burden. Cloud-based object-oriented data models, independent “apps,” open Application Programming Interfaces, or other technologies may supplant the transactional billing platforms15 we now rely upon.

ACOG is engaged at many levels with these issues, and we will continue to keep the interests of our members and the health of our patients at the center of our efforts. But it seems that, at least for now, a move to capturing discrete data elements and relying on eCQMs for quality measurements will shape the foreseeable payment incentive future.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Practicing clinical medicine is increasingly challenging. Besides the onslaught of new clinical information, we have credentialing, accreditation, certification, team-based care, and patient satisfaction that contribute to the complexity of current medical practice. At the heart of many of these challenges is the issue of accountability. Never has our work product as physicians been under such intense scrutiny as it is today.

To demonstrate proof of the care we have provided, we have enlisted a host of administrators, assistants, abstractors, and other helpers to decipher our work and demonstrate its value to professional organizations, boards, hospitals, insurers, and the government. They comb through our charts, decipher our handwriting and dictations, guesstimate our intentions, and sometimes devalue our care because we have not adequately documented what we have done. To solve this accountability problem, our government and the payer community have promoted the electronic health record (EHR) as the “single source of truth” for the care we provide.

This effort received a huge boost in 2009 with the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. HITECH authorized incentive payments through Medicare and Medicaid to health care providers that could demonstrate Meaningful Use (MU) of a certified EHR. This resulted in a boom in EHR purchases and installations.

By 2012, 71.8% of office-based physicians reported using some type of EHR system, up from 34.8% in 2007.1 In many respects this action was designed as a stimulus for the slow economy, but Congress also wanted some type of accountability that the money spent to subsidize EHR purchases was going to be well spent, and would hopefully have an impact on some of the serious health issues we face.

The initial stage of this MU program seemed to work out reasonably well. So, if a little is good, more must be better, right? Unfortunately, no. But, where did MU go wrong, and how is it being fixed? Contrary to popular belief, MU is not going away, it is being transformed. To help you navigate the tethered landscape of MU past and, more importantly, bring you up to speed on MU future (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 [MACRA]) and your payment incentives in this data-centric world, we address MU transformation in this article.

Where Meaningful Use stage 2 went wrong

MU stage 2 turned out to significantly increase the documentation burden on health care professionals. In addition, one of the tragic unintended consequences was that all available EHR development resources by vendors went toward meeting MU data capture requirements rather than to improving the usability and efficiency of the EHRs. Neither result has been well received by health care professionals.

Stage 3 of MU is now in place. It is an attempt to simplify the requirements and focus on quality, safety, interoperability, and patient engagement. See “Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications”. The current progression of MU stages is depicted in TABLE 1.2

Meaningful Use stage 3 specifications

Objective 1: Protect patient health information. Protect electronic health information created or maintained by the Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT) through the implementation of appropriate technical, administrative, and physical safeguards.

Objective 2: Electronic prescribing. Eligible providers (EPs) must generate and transmit permissible prescriptions electronically, and eligible hospitals must generate and transmit permissible discharge prescriptions electronically.