User login

CASE: Patient discloses personal information in electronic communication. How to respond and what’s at stake?

Your nurse comes to you with a dilemma. Last Friday she received an email from a patient, sent to the nurse’s personal email account (G-mail) that conveyed information regarding the patient’s recent treatment for a herpetic vulvar lesion. The text details presumed exposure, date and time, number of sexual partners, concernfor “spread of disease,” and the patient’s desire to have a comprehensive sexually transmitted infection screening as soon as possible.

Your nurse has years of professional experience, but she is perhaps not the most savvy with regard to current information technology and social media. Nonetheless, she knows it is best not to immediately respond to the patient’s email without checking with you. She tracks you down on Monday morning to review the email and the dilemma she feels she has been placed in. What’s the best next step?

While discussing the general question with the staff, another nurse notes that there have been some reviews of the office on social media. It seems that this second nurse tweets and texts with patients all the time. The office manager strongly suggests that the office “join the 21st Century” by setting up a Facebook page and using their webpage to attract new patients and communicate with current patients.

How do you prepare for this? Is your staff knowledgeable about the dos and don’ts of social media?

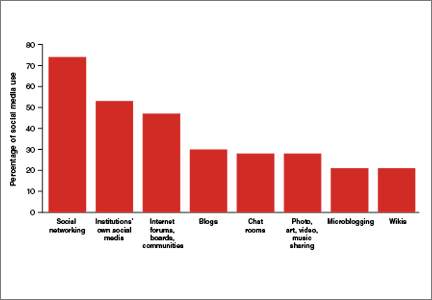

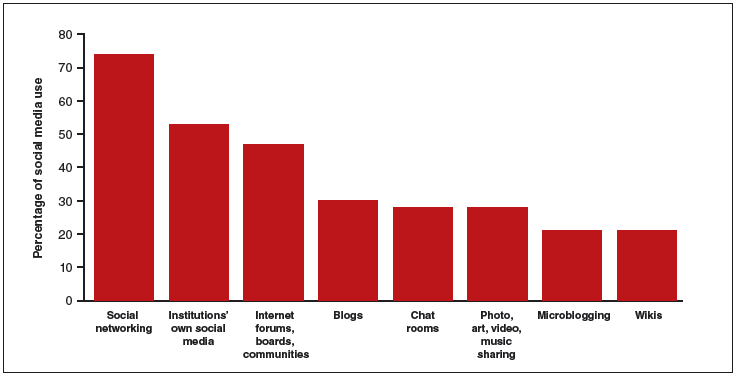

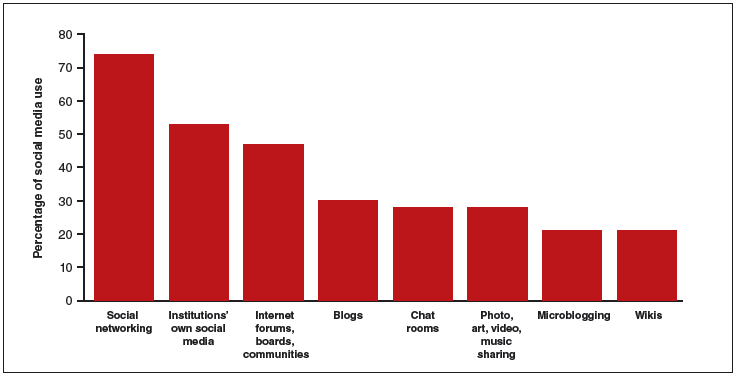

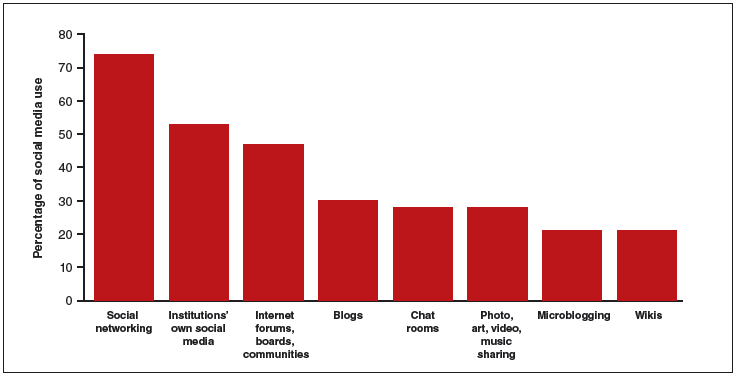

The use of social media by health care providers has been growing for several years. Back in 2011 a large survey by QuantiaMD revealed that 87% of physicians used social media for personal reasons, and 67% of them used it professionally.1 How they used it for professional purposes also was explored in 2011, with almost 3 of 4 physicians using it for social networking and more than half engaging with their own institution’s social media (FIGURE).2 In 2013, 53% of physicians indicated that their practice had a Facebook platform, 28% had a presence on LinkedIn, and 21% were on Twitter.3 Not surprisingly, social media use is higher among younger physicians4; the 2016 equivalents to these percentages most likely are higher.

| Health providers’ use of social media for professional reasons2 |

|

In 2011, a survey found that most health providers used social networking, their institutions’ own social media, and Internet forums, boards, and communities for professional reasons. |

Patients’ outreach through social media regarding health care information continues to grow, with 33.8% asking for health advice using social media.5 While email and other social media open the possibility of improved communication with patients, they also present a number of important professional and legal issues that deserve special consideration.6 Each medium presents its own challenges, but there are 4 categories of concern related to basic values and rights that we consider important to review:

- confidentiality

- dual relationships and conflicts of interest

- quality of care and advice

- general professionalism (including advertising).

Confidentiality

Few values of the medical profession are of longer standing than the commitment to maintain patient privacy. Fifth Century BC obligations continue to apply to the technology of the 21st Century AD. And the challenges are significant.

Email is not secure

In the opening case, the choice to email her clinician was apparently the patient’s. She probably does not realize that email is not very confidential, although it is undoubtedly in the Terms of Service Agreement she clicked through. Her email was likely scanned by her email service provider—Google, in this case—as well as the nurse. If, however, the physician’s office responds by email, it may well compound the confidentiality problem by further distributing the information through yet another email provider.

If, as a physician, you encourage email communication by your patients, a smart approach is to emphasize that such communications are not very confidential. At a minimum, until a secure email system can be established, it is best not to transmit medical information via email and to inform patients of the risk of such communication. In the case above, the nurse who received the email should respond to the patient by telephone (much more secure). Or she can respond to the patient by email (not including the patient’s message in the return), writing that, because email communications are inherently not confidential, she suggests a phone call or personal visit.

This case also notes that the patient sent the email to the nurse’s personal account, not to an office email account. Sending medical emails to an employee’s personal account raises additional problems of confidentiality and appropriate controls. It should be made clear that employees should not be discussing private medical matters via their own email accounts.

Other forms of social media are also not secure

Similar concerns arise about texting and using Twitter by the second nurse. These activities apparently had been unknown to the physician, but the practice still may be responsible for her actions. These are insecure forms of communication and raise serious ethical and legal concerns.

Other social media pose confidentiality risks as well. For example, a physician was dismissed from a position and reprimanded by the medical board for posting patient information on Facebook,7 and an ObGyn caused problems by posting a nasty note about a patient who showed up late for an appointment.8 Too many patients may not understand that posting on social media is the equivalent of standing on a street corner yelling private information. Social media sites that invite the discussion of personal matters are an invitation to trouble.

Physicians are ethically obliged to protect confidentiality

Professional standards place significant ethical obligations on physicians to protect patient confidentiality. The American Medical Association (AMA) has an ethics opinion on professionalism with social media,9 as does the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).10 Another excellent discussion of ethical and practical issues is a joint position paper by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards.11 Both documents focus attention on issues of confidentiality.

Physicians are legally obliged to protect confidentiality

There are many legal protections for confidentiality that can be implicated by electronic communications and social media. All states provide protection for unwarranted disclosure of private patient information. Such disclosures made electronically are included.12 Indeed, because electronic disclosures may be broadcast more widely, they may be especially dangerous. The misuse of social media may result in license discipline by the state board, regulatory sanctions, or civil liability (rare, but criminal sanctions are a possibility in extreme circumstances).

In addition to state laws regarding confidentiality, there are a number of federal laws that cover confidential medical information. None is more important than the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the more recent HITECH amendments (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health).13 These laws have both privacy provisions and security (including “encryption”) requirements. These are complicated laws but at their core are the notions that health care providers and some others:

- are responsible for maintaining the security and privacy of health information

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.14

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.

A good source of step-by-step information about these laws is “Health information privacy: Covered entities and business associates,” on the US Health and Human Services website.14

HITECH also provides for notice to patients when health information is inappropriately transmitted. Thus, a missing USB flash drive with patient information may require notification to thousands of patients.15 Any consideration of the use of email or social media in medical practice must take into account the HIPAA/HITECH obligations to protect the security of patient health information. There can be serious professional consequences for failing to follow the HIPAA requirements.16

Dual relationships and conflicts of interest

In our hypothetical case, the office manager’s suggestion that the office use Facebook and their website to attract new patients also may raise confidentiality problems. The Facebook suggestion especially needs to be considered carefully. Facebook use is estimated to be 63% to 96% among students and 13% to 47% among health care professionals.17 Facebook is most often seen as an interactive social site; it risks blurring the lines between personal and professional relationships.9 There is a consensus that a physician should not “friend” patients on Facebook. The AMA ethics opinion notes that “physicians must maintain appropriate boundaries of the patient-physician relationship in accordance with professional ethical guidelines, just as they would in any other context.”9

Separate personal and professional contacts

Difficulties with interactive social media are not limited to the physicians in a practice. The problems increase with the number of staff members who post or respond on social media. Control of social media is essential. The practice must ensure that staff members do not slip into inappropriate personal comments and relationships. Staff should understand (and be reminded of) the necessity of separating personal and professional contacts.

Avoid misunderstandings

In addition, whatever the intent of the physician and staff may be, it is essentially impossible to know how patients will interpret interactions on these social media. The very informal, off-the-cuff, chatty way in which Facebook and similar sites are used invites misunderstandings, and maintaining professional boundaries is necessary.

Ground rules

All of this is not to say that professionals should never use Facebook or similar sites. Rather, if used, ground rules need to be established.

Social media communications must:

- be professional and not related to personal matters

- not be used to give medical advice

- be controlled by high level staff

- be reviewed periodically.

Staff training

Particularly for interactive social media (email, texts, Twitter, Facebook, etc), it is essential that there be both clear policies and good staff training (TABLE).9–11,18 There really should be no “making it up as we go along.” Staff on a social media lark of their own can be disastrous for the practice. Policies need to be updated frequently, and staff training reinforced and repeated periodically.

Quality of care and advice

Start with your website

Institutions’ websites are major sources of health care information: Nearly 32% of US adults would be very likely to prefer a hospital based on its website.5 Your website can be an important face of your practice to the community—for good or for bad. On one hand, the practice can control what is on a website and, unlike some social media, it will not be directed to individual patients. Done well, it “provides golden opportunities for marketing physician services, as well as for contributing to public health by providing high-quality online content that is both accurate and understandable to laypeople.”19 Done badly, it can convey incorrect and harmful information and discredit the medical practice that established it.

Your website introduces the practice and settings, but it will serve another purpose to thousands of people who likely will see it over time as a source of credible health information. The importance of ensuring that your website is carefully constructed to provide, or link to, good medical advice that contributes to quality of care cannot be overstated.

A good website begins with a clear statement of the reasons and goals for having the site. Professional design assistance generally is used to create the site, but that design process needs to be overseen by a medical professional to ensure that it conveys the sense of the practice and provides completely accurate information. A homepage of dancing clowns with stethoscopes may seem good to a 20-something-year-old designer, but it is not appropriate for a physician. It will be the practice, not the designer, who is held accountable for the site content. Links to other sites need to be vetted and used with care. Patients and other members of the public may well take the links as carrying the endorsement of the practice and its physicians.

Perhaps the greatest risk of a website is that it will not be kept current. Unfortunately, they do not update themselves. Some knowledgeable staff member must frequently review it to update everything from office hours and personnel to links to other sites. In addition, the physicians periodically must review it to ensure that all medical information is up to date and accurate. Old, outdated information about the office can put off potential patients. Outdated medical information may be harmful to patients who rely on it.

Any professional website should include disclaimers informing users that the site is not intended to establish a professional relationship or to give professional advice. The nature and extent of the disclaimer will depend on the type of information on the site. An example of a particularly thorough disclaimer is the Mayo Clinic disclaimer and terms of use (http://www.mayoclinic.org/about-this-site/terms-conditions-use-policy).

General professionalism

At the end of the day, social media are an outreach from a medical practice and from the profession to the public.20 Failure to treat these platforms with appropriate professional standards may result in professional discipline, damages, or civil penalties. Almost all of the reviews of social media use in health care practice note that the risks of inappropriate use are not only to the individual physician but also to the general medical profession, which may be undermined. Consider posting policies of the relevent state medical boards, the AMA, and ACOG in your office after you have had a discussion with your staff about them.21

The AMA statement includes a provision that a physician seeing unprofessional social media conduct by a colleague has the responsibility to bring that to the attention of the colleague. If the colleague does not correct a significant problem, “the physician should report the matter to appropriate authorities.”9

Bottom line

Any practitioner considering the use of social media must view it as a major step that requires caution, expert assistance, and constant attention to potential privacy, quality, and professionalism issues. If you are considering it, ensure that all staff associated with the practice understand and agree to the established limits on social media use.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, patients, & social media. Quantia MD website. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/DoctorsPatientSocialMedia.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Kuberacka A, Wengrojj J, Fabozzi N. Social media use in U.S. healthcare provider institutions: Insights from Frost & Sullivan and iHT2 survey. Frost and Sullivan website. http://ihealthtran.com/pdf/frostiht2survey.pdf. Published August 30, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- O’Connor ME. How do tech savvy physicians use health technology and social media? Health Care Social Media website. http://hcsmmonitor.com/2014/01/08/how-do-tech-savvy-physicians-use-health-technology-and-social-media/. Published January 8, 2014. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American Medical Association (AMA) Insurance. 2014 work/life profiles of today’s U.S. physician. AMA Insurance website. https://www.amainsure.com/work-life-profiles-of-todays-us-physician.html. Published April 2014. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- National Research Corporation. 2013 National Market Insights Survey: Health care social media website. https://healthcaresocialmedia.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/nrc-infographiclong.jpg. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Suby C. Social media in health care: benefits, concerns and guidelines for use. Creat Nurs. 2013;19(3):140–147.

- Conaboy C. For doctors, social media a tricky case. Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/health/articles/2011/04/20/for_doctors_social_media_a_tricky_case/?page=full. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Matyszczyk C. Outcry as ob-gyn uses Facebook to complain about patient. CNET. http://www.cnet.com/news/outcry-as-ob-gyn-uses-facebook-to-complain-about-patient/Minion Pro. Published February 9, 2013. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American Medical Association (AMA). Opinion 9.124: Professionalism in the use of social media. AMA website. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion9124.page? Published June 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Professional Liability. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 622: professional use of digital and social media. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):516-520.

- Farnan JM, Sulmasy LS, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: Policy Statement From the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620–627.

- Hader A, Drown E. Patient privacy and social media. AANA J. 2010;78(4):270–274.

- Kavoussi SC, Huang JJ, Tsai JC, Kempton JE. HIPAA for physicians in the information age. Conn Med. 2014;78(7):425–427.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS). Health information privacy: Covered entities and business associates. HHS website. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/. Published March 14, 2012. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Perna G. Breach report: lost flash drive at Kaiser Permanente affects 49,000 patients. Healthcare Informatics website. http://www.healthcare-informatics.com/news-item/breach-report-lost-flash-drive-kaiser-permanente-affects-49000-patients. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- McBride M. How to ensure your social media efforts are HIPAA-compliant. Med Econ. 2012;89:70–74.

- Von Muhlen M, Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):777–781.

- Omurtag K, Turek P. Incorporating social media into practice: a blueprint for reproductive health providers. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56(3):463–470.

- Radmanesh A, Duszak R, Fitzgerald R. Social media and public outreach: a physician primer. Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(7):1223–1224.

- Grajales FJ 3rd, Sheps S, Ho K, Novak-Lauscher H, Eysenbach G. Social media: a review and tutorial of applications in medicine and health care. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e13.

- ACOG Today. Social media guide: how to comment with patients and spread women’s health messages. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/-/media/ACOG-Today/acogToday201211.pdf. Published November 2012. Accessed February 18, 2016.

CASE: Patient discloses personal information in electronic communication. How to respond and what’s at stake?

Your nurse comes to you with a dilemma. Last Friday she received an email from a patient, sent to the nurse’s personal email account (G-mail) that conveyed information regarding the patient’s recent treatment for a herpetic vulvar lesion. The text details presumed exposure, date and time, number of sexual partners, concernfor “spread of disease,” and the patient’s desire to have a comprehensive sexually transmitted infection screening as soon as possible.

Your nurse has years of professional experience, but she is perhaps not the most savvy with regard to current information technology and social media. Nonetheless, she knows it is best not to immediately respond to the patient’s email without checking with you. She tracks you down on Monday morning to review the email and the dilemma she feels she has been placed in. What’s the best next step?

While discussing the general question with the staff, another nurse notes that there have been some reviews of the office on social media. It seems that this second nurse tweets and texts with patients all the time. The office manager strongly suggests that the office “join the 21st Century” by setting up a Facebook page and using their webpage to attract new patients and communicate with current patients.

How do you prepare for this? Is your staff knowledgeable about the dos and don’ts of social media?

The use of social media by health care providers has been growing for several years. Back in 2011 a large survey by QuantiaMD revealed that 87% of physicians used social media for personal reasons, and 67% of them used it professionally.1 How they used it for professional purposes also was explored in 2011, with almost 3 of 4 physicians using it for social networking and more than half engaging with their own institution’s social media (FIGURE).2 In 2013, 53% of physicians indicated that their practice had a Facebook platform, 28% had a presence on LinkedIn, and 21% were on Twitter.3 Not surprisingly, social media use is higher among younger physicians4; the 2016 equivalents to these percentages most likely are higher.

| Health providers’ use of social media for professional reasons2 |

|

In 2011, a survey found that most health providers used social networking, their institutions’ own social media, and Internet forums, boards, and communities for professional reasons. |

Patients’ outreach through social media regarding health care information continues to grow, with 33.8% asking for health advice using social media.5 While email and other social media open the possibility of improved communication with patients, they also present a number of important professional and legal issues that deserve special consideration.6 Each medium presents its own challenges, but there are 4 categories of concern related to basic values and rights that we consider important to review:

- confidentiality

- dual relationships and conflicts of interest

- quality of care and advice

- general professionalism (including advertising).

Confidentiality

Few values of the medical profession are of longer standing than the commitment to maintain patient privacy. Fifth Century BC obligations continue to apply to the technology of the 21st Century AD. And the challenges are significant.

Email is not secure

In the opening case, the choice to email her clinician was apparently the patient’s. She probably does not realize that email is not very confidential, although it is undoubtedly in the Terms of Service Agreement she clicked through. Her email was likely scanned by her email service provider—Google, in this case—as well as the nurse. If, however, the physician’s office responds by email, it may well compound the confidentiality problem by further distributing the information through yet another email provider.

If, as a physician, you encourage email communication by your patients, a smart approach is to emphasize that such communications are not very confidential. At a minimum, until a secure email system can be established, it is best not to transmit medical information via email and to inform patients of the risk of such communication. In the case above, the nurse who received the email should respond to the patient by telephone (much more secure). Or she can respond to the patient by email (not including the patient’s message in the return), writing that, because email communications are inherently not confidential, she suggests a phone call or personal visit.

This case also notes that the patient sent the email to the nurse’s personal account, not to an office email account. Sending medical emails to an employee’s personal account raises additional problems of confidentiality and appropriate controls. It should be made clear that employees should not be discussing private medical matters via their own email accounts.

Other forms of social media are also not secure

Similar concerns arise about texting and using Twitter by the second nurse. These activities apparently had been unknown to the physician, but the practice still may be responsible for her actions. These are insecure forms of communication and raise serious ethical and legal concerns.

Other social media pose confidentiality risks as well. For example, a physician was dismissed from a position and reprimanded by the medical board for posting patient information on Facebook,7 and an ObGyn caused problems by posting a nasty note about a patient who showed up late for an appointment.8 Too many patients may not understand that posting on social media is the equivalent of standing on a street corner yelling private information. Social media sites that invite the discussion of personal matters are an invitation to trouble.

Physicians are ethically obliged to protect confidentiality

Professional standards place significant ethical obligations on physicians to protect patient confidentiality. The American Medical Association (AMA) has an ethics opinion on professionalism with social media,9 as does the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).10 Another excellent discussion of ethical and practical issues is a joint position paper by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards.11 Both documents focus attention on issues of confidentiality.

Physicians are legally obliged to protect confidentiality

There are many legal protections for confidentiality that can be implicated by electronic communications and social media. All states provide protection for unwarranted disclosure of private patient information. Such disclosures made electronically are included.12 Indeed, because electronic disclosures may be broadcast more widely, they may be especially dangerous. The misuse of social media may result in license discipline by the state board, regulatory sanctions, or civil liability (rare, but criminal sanctions are a possibility in extreme circumstances).

In addition to state laws regarding confidentiality, there are a number of federal laws that cover confidential medical information. None is more important than the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the more recent HITECH amendments (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health).13 These laws have both privacy provisions and security (including “encryption”) requirements. These are complicated laws but at their core are the notions that health care providers and some others:

- are responsible for maintaining the security and privacy of health information

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.14

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.

A good source of step-by-step information about these laws is “Health information privacy: Covered entities and business associates,” on the US Health and Human Services website.14

HITECH also provides for notice to patients when health information is inappropriately transmitted. Thus, a missing USB flash drive with patient information may require notification to thousands of patients.15 Any consideration of the use of email or social media in medical practice must take into account the HIPAA/HITECH obligations to protect the security of patient health information. There can be serious professional consequences for failing to follow the HIPAA requirements.16

Dual relationships and conflicts of interest

In our hypothetical case, the office manager’s suggestion that the office use Facebook and their website to attract new patients also may raise confidentiality problems. The Facebook suggestion especially needs to be considered carefully. Facebook use is estimated to be 63% to 96% among students and 13% to 47% among health care professionals.17 Facebook is most often seen as an interactive social site; it risks blurring the lines between personal and professional relationships.9 There is a consensus that a physician should not “friend” patients on Facebook. The AMA ethics opinion notes that “physicians must maintain appropriate boundaries of the patient-physician relationship in accordance with professional ethical guidelines, just as they would in any other context.”9

Separate personal and professional contacts

Difficulties with interactive social media are not limited to the physicians in a practice. The problems increase with the number of staff members who post or respond on social media. Control of social media is essential. The practice must ensure that staff members do not slip into inappropriate personal comments and relationships. Staff should understand (and be reminded of) the necessity of separating personal and professional contacts.

Avoid misunderstandings

In addition, whatever the intent of the physician and staff may be, it is essentially impossible to know how patients will interpret interactions on these social media. The very informal, off-the-cuff, chatty way in which Facebook and similar sites are used invites misunderstandings, and maintaining professional boundaries is necessary.

Ground rules

All of this is not to say that professionals should never use Facebook or similar sites. Rather, if used, ground rules need to be established.

Social media communications must:

- be professional and not related to personal matters

- not be used to give medical advice

- be controlled by high level staff

- be reviewed periodically.

Staff training

Particularly for interactive social media (email, texts, Twitter, Facebook, etc), it is essential that there be both clear policies and good staff training (TABLE).9–11,18 There really should be no “making it up as we go along.” Staff on a social media lark of their own can be disastrous for the practice. Policies need to be updated frequently, and staff training reinforced and repeated periodically.

Quality of care and advice

Start with your website

Institutions’ websites are major sources of health care information: Nearly 32% of US adults would be very likely to prefer a hospital based on its website.5 Your website can be an important face of your practice to the community—for good or for bad. On one hand, the practice can control what is on a website and, unlike some social media, it will not be directed to individual patients. Done well, it “provides golden opportunities for marketing physician services, as well as for contributing to public health by providing high-quality online content that is both accurate and understandable to laypeople.”19 Done badly, it can convey incorrect and harmful information and discredit the medical practice that established it.

Your website introduces the practice and settings, but it will serve another purpose to thousands of people who likely will see it over time as a source of credible health information. The importance of ensuring that your website is carefully constructed to provide, or link to, good medical advice that contributes to quality of care cannot be overstated.

A good website begins with a clear statement of the reasons and goals for having the site. Professional design assistance generally is used to create the site, but that design process needs to be overseen by a medical professional to ensure that it conveys the sense of the practice and provides completely accurate information. A homepage of dancing clowns with stethoscopes may seem good to a 20-something-year-old designer, but it is not appropriate for a physician. It will be the practice, not the designer, who is held accountable for the site content. Links to other sites need to be vetted and used with care. Patients and other members of the public may well take the links as carrying the endorsement of the practice and its physicians.

Perhaps the greatest risk of a website is that it will not be kept current. Unfortunately, they do not update themselves. Some knowledgeable staff member must frequently review it to update everything from office hours and personnel to links to other sites. In addition, the physicians periodically must review it to ensure that all medical information is up to date and accurate. Old, outdated information about the office can put off potential patients. Outdated medical information may be harmful to patients who rely on it.

Any professional website should include disclaimers informing users that the site is not intended to establish a professional relationship or to give professional advice. The nature and extent of the disclaimer will depend on the type of information on the site. An example of a particularly thorough disclaimer is the Mayo Clinic disclaimer and terms of use (http://www.mayoclinic.org/about-this-site/terms-conditions-use-policy).

General professionalism

At the end of the day, social media are an outreach from a medical practice and from the profession to the public.20 Failure to treat these platforms with appropriate professional standards may result in professional discipline, damages, or civil penalties. Almost all of the reviews of social media use in health care practice note that the risks of inappropriate use are not only to the individual physician but also to the general medical profession, which may be undermined. Consider posting policies of the relevent state medical boards, the AMA, and ACOG in your office after you have had a discussion with your staff about them.21

The AMA statement includes a provision that a physician seeing unprofessional social media conduct by a colleague has the responsibility to bring that to the attention of the colleague. If the colleague does not correct a significant problem, “the physician should report the matter to appropriate authorities.”9

Bottom line

Any practitioner considering the use of social media must view it as a major step that requires caution, expert assistance, and constant attention to potential privacy, quality, and professionalism issues. If you are considering it, ensure that all staff associated with the practice understand and agree to the established limits on social media use.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Patient discloses personal information in electronic communication. How to respond and what’s at stake?

Your nurse comes to you with a dilemma. Last Friday she received an email from a patient, sent to the nurse’s personal email account (G-mail) that conveyed information regarding the patient’s recent treatment for a herpetic vulvar lesion. The text details presumed exposure, date and time, number of sexual partners, concernfor “spread of disease,” and the patient’s desire to have a comprehensive sexually transmitted infection screening as soon as possible.

Your nurse has years of professional experience, but she is perhaps not the most savvy with regard to current information technology and social media. Nonetheless, she knows it is best not to immediately respond to the patient’s email without checking with you. She tracks you down on Monday morning to review the email and the dilemma she feels she has been placed in. What’s the best next step?

While discussing the general question with the staff, another nurse notes that there have been some reviews of the office on social media. It seems that this second nurse tweets and texts with patients all the time. The office manager strongly suggests that the office “join the 21st Century” by setting up a Facebook page and using their webpage to attract new patients and communicate with current patients.

How do you prepare for this? Is your staff knowledgeable about the dos and don’ts of social media?

The use of social media by health care providers has been growing for several years. Back in 2011 a large survey by QuantiaMD revealed that 87% of physicians used social media for personal reasons, and 67% of them used it professionally.1 How they used it for professional purposes also was explored in 2011, with almost 3 of 4 physicians using it for social networking and more than half engaging with their own institution’s social media (FIGURE).2 In 2013, 53% of physicians indicated that their practice had a Facebook platform, 28% had a presence on LinkedIn, and 21% were on Twitter.3 Not surprisingly, social media use is higher among younger physicians4; the 2016 equivalents to these percentages most likely are higher.

| Health providers’ use of social media for professional reasons2 |

|

In 2011, a survey found that most health providers used social networking, their institutions’ own social media, and Internet forums, boards, and communities for professional reasons. |

Patients’ outreach through social media regarding health care information continues to grow, with 33.8% asking for health advice using social media.5 While email and other social media open the possibility of improved communication with patients, they also present a number of important professional and legal issues that deserve special consideration.6 Each medium presents its own challenges, but there are 4 categories of concern related to basic values and rights that we consider important to review:

- confidentiality

- dual relationships and conflicts of interest

- quality of care and advice

- general professionalism (including advertising).

Confidentiality

Few values of the medical profession are of longer standing than the commitment to maintain patient privacy. Fifth Century BC obligations continue to apply to the technology of the 21st Century AD. And the challenges are significant.

Email is not secure

In the opening case, the choice to email her clinician was apparently the patient’s. She probably does not realize that email is not very confidential, although it is undoubtedly in the Terms of Service Agreement she clicked through. Her email was likely scanned by her email service provider—Google, in this case—as well as the nurse. If, however, the physician’s office responds by email, it may well compound the confidentiality problem by further distributing the information through yet another email provider.

If, as a physician, you encourage email communication by your patients, a smart approach is to emphasize that such communications are not very confidential. At a minimum, until a secure email system can be established, it is best not to transmit medical information via email and to inform patients of the risk of such communication. In the case above, the nurse who received the email should respond to the patient by telephone (much more secure). Or she can respond to the patient by email (not including the patient’s message in the return), writing that, because email communications are inherently not confidential, she suggests a phone call or personal visit.

This case also notes that the patient sent the email to the nurse’s personal account, not to an office email account. Sending medical emails to an employee’s personal account raises additional problems of confidentiality and appropriate controls. It should be made clear that employees should not be discussing private medical matters via their own email accounts.

Other forms of social media are also not secure

Similar concerns arise about texting and using Twitter by the second nurse. These activities apparently had been unknown to the physician, but the practice still may be responsible for her actions. These are insecure forms of communication and raise serious ethical and legal concerns.

Other social media pose confidentiality risks as well. For example, a physician was dismissed from a position and reprimanded by the medical board for posting patient information on Facebook,7 and an ObGyn caused problems by posting a nasty note about a patient who showed up late for an appointment.8 Too many patients may not understand that posting on social media is the equivalent of standing on a street corner yelling private information. Social media sites that invite the discussion of personal matters are an invitation to trouble.

Physicians are ethically obliged to protect confidentiality

Professional standards place significant ethical obligations on physicians to protect patient confidentiality. The American Medical Association (AMA) has an ethics opinion on professionalism with social media,9 as does the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).10 Another excellent discussion of ethical and practical issues is a joint position paper by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards.11 Both documents focus attention on issues of confidentiality.

Physicians are legally obliged to protect confidentiality

There are many legal protections for confidentiality that can be implicated by electronic communications and social media. All states provide protection for unwarranted disclosure of private patient information. Such disclosures made electronically are included.12 Indeed, because electronic disclosures may be broadcast more widely, they may be especially dangerous. The misuse of social media may result in license discipline by the state board, regulatory sanctions, or civil liability (rare, but criminal sanctions are a possibility in extreme circumstances).

In addition to state laws regarding confidentiality, there are a number of federal laws that cover confidential medical information. None is more important than the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the more recent HITECH amendments (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health).13 These laws have both privacy provisions and security (including “encryption”) requirements. These are complicated laws but at their core are the notions that health care providers and some others:

- are responsible for maintaining the security and privacy of health information

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.14

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.

A good source of step-by-step information about these laws is “Health information privacy: Covered entities and business associates,” on the US Health and Human Services website.14

HITECH also provides for notice to patients when health information is inappropriately transmitted. Thus, a missing USB flash drive with patient information may require notification to thousands of patients.15 Any consideration of the use of email or social media in medical practice must take into account the HIPAA/HITECH obligations to protect the security of patient health information. There can be serious professional consequences for failing to follow the HIPAA requirements.16

Dual relationships and conflicts of interest

In our hypothetical case, the office manager’s suggestion that the office use Facebook and their website to attract new patients also may raise confidentiality problems. The Facebook suggestion especially needs to be considered carefully. Facebook use is estimated to be 63% to 96% among students and 13% to 47% among health care professionals.17 Facebook is most often seen as an interactive social site; it risks blurring the lines between personal and professional relationships.9 There is a consensus that a physician should not “friend” patients on Facebook. The AMA ethics opinion notes that “physicians must maintain appropriate boundaries of the patient-physician relationship in accordance with professional ethical guidelines, just as they would in any other context.”9

Separate personal and professional contacts

Difficulties with interactive social media are not limited to the physicians in a practice. The problems increase with the number of staff members who post or respond on social media. Control of social media is essential. The practice must ensure that staff members do not slip into inappropriate personal comments and relationships. Staff should understand (and be reminded of) the necessity of separating personal and professional contacts.

Avoid misunderstandings

In addition, whatever the intent of the physician and staff may be, it is essentially impossible to know how patients will interpret interactions on these social media. The very informal, off-the-cuff, chatty way in which Facebook and similar sites are used invites misunderstandings, and maintaining professional boundaries is necessary.

Ground rules

All of this is not to say that professionals should never use Facebook or similar sites. Rather, if used, ground rules need to be established.

Social media communications must:

- be professional and not related to personal matters

- not be used to give medical advice

- be controlled by high level staff

- be reviewed periodically.

Staff training

Particularly for interactive social media (email, texts, Twitter, Facebook, etc), it is essential that there be both clear policies and good staff training (TABLE).9–11,18 There really should be no “making it up as we go along.” Staff on a social media lark of their own can be disastrous for the practice. Policies need to be updated frequently, and staff training reinforced and repeated periodically.

Quality of care and advice

Start with your website

Institutions’ websites are major sources of health care information: Nearly 32% of US adults would be very likely to prefer a hospital based on its website.5 Your website can be an important face of your practice to the community—for good or for bad. On one hand, the practice can control what is on a website and, unlike some social media, it will not be directed to individual patients. Done well, it “provides golden opportunities for marketing physician services, as well as for contributing to public health by providing high-quality online content that is both accurate and understandable to laypeople.”19 Done badly, it can convey incorrect and harmful information and discredit the medical practice that established it.

Your website introduces the practice and settings, but it will serve another purpose to thousands of people who likely will see it over time as a source of credible health information. The importance of ensuring that your website is carefully constructed to provide, or link to, good medical advice that contributes to quality of care cannot be overstated.

A good website begins with a clear statement of the reasons and goals for having the site. Professional design assistance generally is used to create the site, but that design process needs to be overseen by a medical professional to ensure that it conveys the sense of the practice and provides completely accurate information. A homepage of dancing clowns with stethoscopes may seem good to a 20-something-year-old designer, but it is not appropriate for a physician. It will be the practice, not the designer, who is held accountable for the site content. Links to other sites need to be vetted and used with care. Patients and other members of the public may well take the links as carrying the endorsement of the practice and its physicians.

Perhaps the greatest risk of a website is that it will not be kept current. Unfortunately, they do not update themselves. Some knowledgeable staff member must frequently review it to update everything from office hours and personnel to links to other sites. In addition, the physicians periodically must review it to ensure that all medical information is up to date and accurate. Old, outdated information about the office can put off potential patients. Outdated medical information may be harmful to patients who rely on it.

Any professional website should include disclaimers informing users that the site is not intended to establish a professional relationship or to give professional advice. The nature and extent of the disclaimer will depend on the type of information on the site. An example of a particularly thorough disclaimer is the Mayo Clinic disclaimer and terms of use (http://www.mayoclinic.org/about-this-site/terms-conditions-use-policy).

General professionalism

At the end of the day, social media are an outreach from a medical practice and from the profession to the public.20 Failure to treat these platforms with appropriate professional standards may result in professional discipline, damages, or civil penalties. Almost all of the reviews of social media use in health care practice note that the risks of inappropriate use are not only to the individual physician but also to the general medical profession, which may be undermined. Consider posting policies of the relevent state medical boards, the AMA, and ACOG in your office after you have had a discussion with your staff about them.21

The AMA statement includes a provision that a physician seeing unprofessional social media conduct by a colleague has the responsibility to bring that to the attention of the colleague. If the colleague does not correct a significant problem, “the physician should report the matter to appropriate authorities.”9

Bottom line

Any practitioner considering the use of social media must view it as a major step that requires caution, expert assistance, and constant attention to potential privacy, quality, and professionalism issues. If you are considering it, ensure that all staff associated with the practice understand and agree to the established limits on social media use.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, patients, & social media. Quantia MD website. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/DoctorsPatientSocialMedia.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Kuberacka A, Wengrojj J, Fabozzi N. Social media use in U.S. healthcare provider institutions: Insights from Frost & Sullivan and iHT2 survey. Frost and Sullivan website. http://ihealthtran.com/pdf/frostiht2survey.pdf. Published August 30, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- O’Connor ME. How do tech savvy physicians use health technology and social media? Health Care Social Media website. http://hcsmmonitor.com/2014/01/08/how-do-tech-savvy-physicians-use-health-technology-and-social-media/. Published January 8, 2014. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American Medical Association (AMA) Insurance. 2014 work/life profiles of today’s U.S. physician. AMA Insurance website. https://www.amainsure.com/work-life-profiles-of-todays-us-physician.html. Published April 2014. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- National Research Corporation. 2013 National Market Insights Survey: Health care social media website. https://healthcaresocialmedia.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/nrc-infographiclong.jpg. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Suby C. Social media in health care: benefits, concerns and guidelines for use. Creat Nurs. 2013;19(3):140–147.

- Conaboy C. For doctors, social media a tricky case. Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/health/articles/2011/04/20/for_doctors_social_media_a_tricky_case/?page=full. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Matyszczyk C. Outcry as ob-gyn uses Facebook to complain about patient. CNET. http://www.cnet.com/news/outcry-as-ob-gyn-uses-facebook-to-complain-about-patient/Minion Pro. Published February 9, 2013. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American Medical Association (AMA). Opinion 9.124: Professionalism in the use of social media. AMA website. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion9124.page? Published June 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Professional Liability. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 622: professional use of digital and social media. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):516-520.

- Farnan JM, Sulmasy LS, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: Policy Statement From the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620–627.

- Hader A, Drown E. Patient privacy and social media. AANA J. 2010;78(4):270–274.

- Kavoussi SC, Huang JJ, Tsai JC, Kempton JE. HIPAA for physicians in the information age. Conn Med. 2014;78(7):425–427.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS). Health information privacy: Covered entities and business associates. HHS website. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/. Published March 14, 2012. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Perna G. Breach report: lost flash drive at Kaiser Permanente affects 49,000 patients. Healthcare Informatics website. http://www.healthcare-informatics.com/news-item/breach-report-lost-flash-drive-kaiser-permanente-affects-49000-patients. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- McBride M. How to ensure your social media efforts are HIPAA-compliant. Med Econ. 2012;89:70–74.

- Von Muhlen M, Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):777–781.

- Omurtag K, Turek P. Incorporating social media into practice: a blueprint for reproductive health providers. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56(3):463–470.

- Radmanesh A, Duszak R, Fitzgerald R. Social media and public outreach: a physician primer. Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(7):1223–1224.

- Grajales FJ 3rd, Sheps S, Ho K, Novak-Lauscher H, Eysenbach G. Social media: a review and tutorial of applications in medicine and health care. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e13.

- ACOG Today. Social media guide: how to comment with patients and spread women’s health messages. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/-/media/ACOG-Today/acogToday201211.pdf. Published November 2012. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, patients, & social media. Quantia MD website. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/DoctorsPatientSocialMedia.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Kuberacka A, Wengrojj J, Fabozzi N. Social media use in U.S. healthcare provider institutions: Insights from Frost & Sullivan and iHT2 survey. Frost and Sullivan website. http://ihealthtran.com/pdf/frostiht2survey.pdf. Published August 30, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- O’Connor ME. How do tech savvy physicians use health technology and social media? Health Care Social Media website. http://hcsmmonitor.com/2014/01/08/how-do-tech-savvy-physicians-use-health-technology-and-social-media/. Published January 8, 2014. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American Medical Association (AMA) Insurance. 2014 work/life profiles of today’s U.S. physician. AMA Insurance website. https://www.amainsure.com/work-life-profiles-of-todays-us-physician.html. Published April 2014. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- National Research Corporation. 2013 National Market Insights Survey: Health care social media website. https://healthcaresocialmedia.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/nrc-infographiclong.jpg. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Suby C. Social media in health care: benefits, concerns and guidelines for use. Creat Nurs. 2013;19(3):140–147.

- Conaboy C. For doctors, social media a tricky case. Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/health/articles/2011/04/20/for_doctors_social_media_a_tricky_case/?page=full. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Matyszczyk C. Outcry as ob-gyn uses Facebook to complain about patient. CNET. http://www.cnet.com/news/outcry-as-ob-gyn-uses-facebook-to-complain-about-patient/Minion Pro. Published February 9, 2013. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American Medical Association (AMA). Opinion 9.124: Professionalism in the use of social media. AMA website. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion9124.page? Published June 2011. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Professional Liability. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 622: professional use of digital and social media. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):516-520.

- Farnan JM, Sulmasy LS, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: Policy Statement From the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):620–627.

- Hader A, Drown E. Patient privacy and social media. AANA J. 2010;78(4):270–274.

- Kavoussi SC, Huang JJ, Tsai JC, Kempton JE. HIPAA for physicians in the information age. Conn Med. 2014;78(7):425–427.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS). Health information privacy: Covered entities and business associates. HHS website. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/. Published March 14, 2012. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- Perna G. Breach report: lost flash drive at Kaiser Permanente affects 49,000 patients. Healthcare Informatics website. http://www.healthcare-informatics.com/news-item/breach-report-lost-flash-drive-kaiser-permanente-affects-49000-patients. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- McBride M. How to ensure your social media efforts are HIPAA-compliant. Med Econ. 2012;89:70–74.

- Von Muhlen M, Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):777–781.

- Omurtag K, Turek P. Incorporating social media into practice: a blueprint for reproductive health providers. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56(3):463–470.

- Radmanesh A, Duszak R, Fitzgerald R. Social media and public outreach: a physician primer. Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(7):1223–1224.

- Grajales FJ 3rd, Sheps S, Ho K, Novak-Lauscher H, Eysenbach G. Social media: a review and tutorial of applications in medicine and health care. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e13.

- ACOG Today. Social media guide: how to comment with patients and spread women’s health messages. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. http://www.acog.org/-/media/ACOG-Today/acogToday201211.pdf. Published November 2012. Accessed February 18, 2016.

In this Article

- Health providers’ use of social media

- Protecting confidentiality

- Creating a social media policy