User login

Edema Affecting the Penis and Scrotum

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can involve any region of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anus but most commonly presents in the terminal ileum, colon, or small bowel with transmural inflammation, fistula formation, and knife-cut fissures among the frequently described findings. Extraintestinal manifestations may be found in the liver, eyes, and joints, with cutaneous extraintestinal manifestations occurring in up to one-third of patients.1

Crohn disease can be associated with multiple cutaneous findings, including erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous ulcers, pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans, necrotizing vasculitis, and metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2 Typical histopathologic findings seen in MCD such as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis, possibly extending to the subcutaneous fat, are not specific to MCD. Associated genital edema is thought to be a consequence of granulomatous inflammation of lymphatics. In one study reviewing specimens from 10 cases of CD, a mean of 46% of all granulomas identified on the slides (264 granulomas in total) were located proximal to lymphatic vessels, suggesting a common pathway for development of intestinal disease and genital edema.3 The differential diagnosis for penile and scrotal swelling is broad, and the diagnosis may be missed if attention is not given to the clinical history of the patient in addition to histopathologic findings.2

Skin changes in CD also can be separated into perianal disease and true metastatic disease--the former recognized when anal lesions appear associated with segmental involvement of the GI tract and the latter as ulceration of the skin separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 The term sarcoidal reaction often is used to describe histopathologic findings in cutaneous CD, as it refers to the noncaseating granulomas found in approximately 60% of all cases.4 Ultimately, the location of noncaseating granulomas within the dermis of our patient's biopsy, taken in conjunction with the clinical history and the lack of defining features for other potential etiologies (eg, polarizable material, organisms on special stains), led to the diagnosis of cutaneous CD.

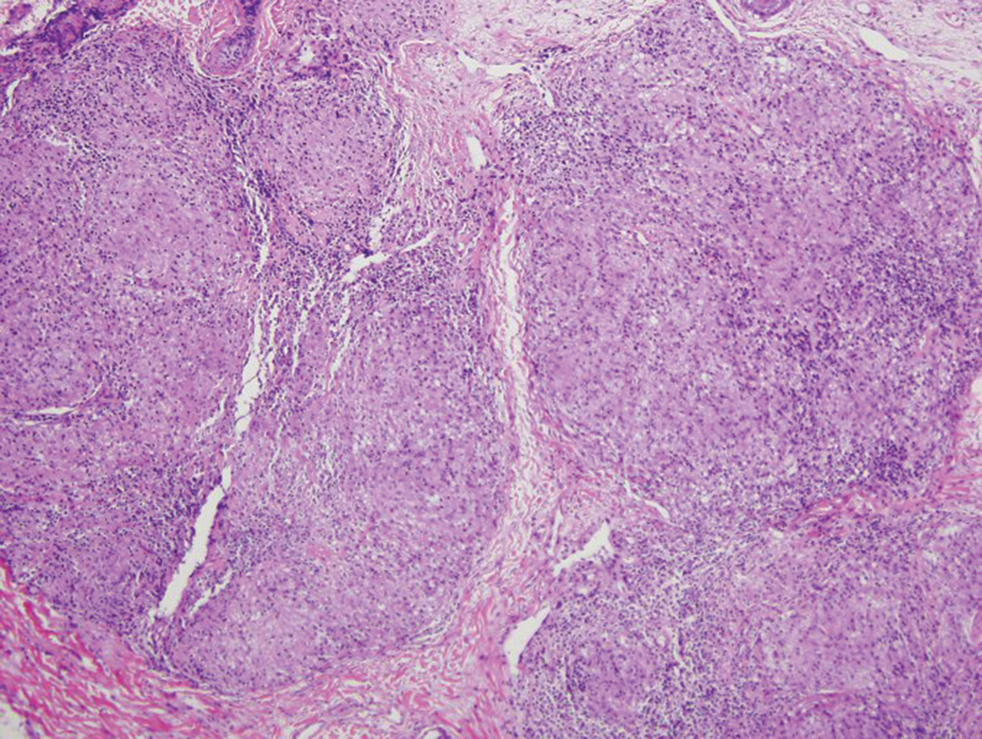

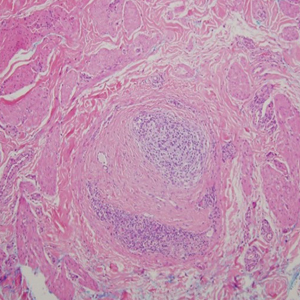

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis most commonly occur as papules, plaques, and subcutaneous nodules predominantly on the face, upper back, arms, and legs. Although the histologic features of sarcoidosis are characterized by lymphocyte-poor noncaseating granulomas (Figure 1), these findings also can be seen as a consequence of multiple granulomatous causes.5,6 In a review of 48 cutaneous specimens from patients with sarcoidosis, the granulomas were found most frequently in the deep dermis (34/48 [70.8%]), with superficial dermis (21/48) and subcutaneous fat granulomas (20/48) each present in less than 50% of biopsies.5 Although less typical, cutaneous sarcoidosis also has been noted in the literature to present in the perianal and gluteal region, demonstrating dermal noncaseating granulomas on biopsy.7 One distinction in particular to be noted between sarcoid and CD is that sarcoid lesions in the skin rarely ulcerate, while the lesions of cutaneous CD often are ulcerated.4,6

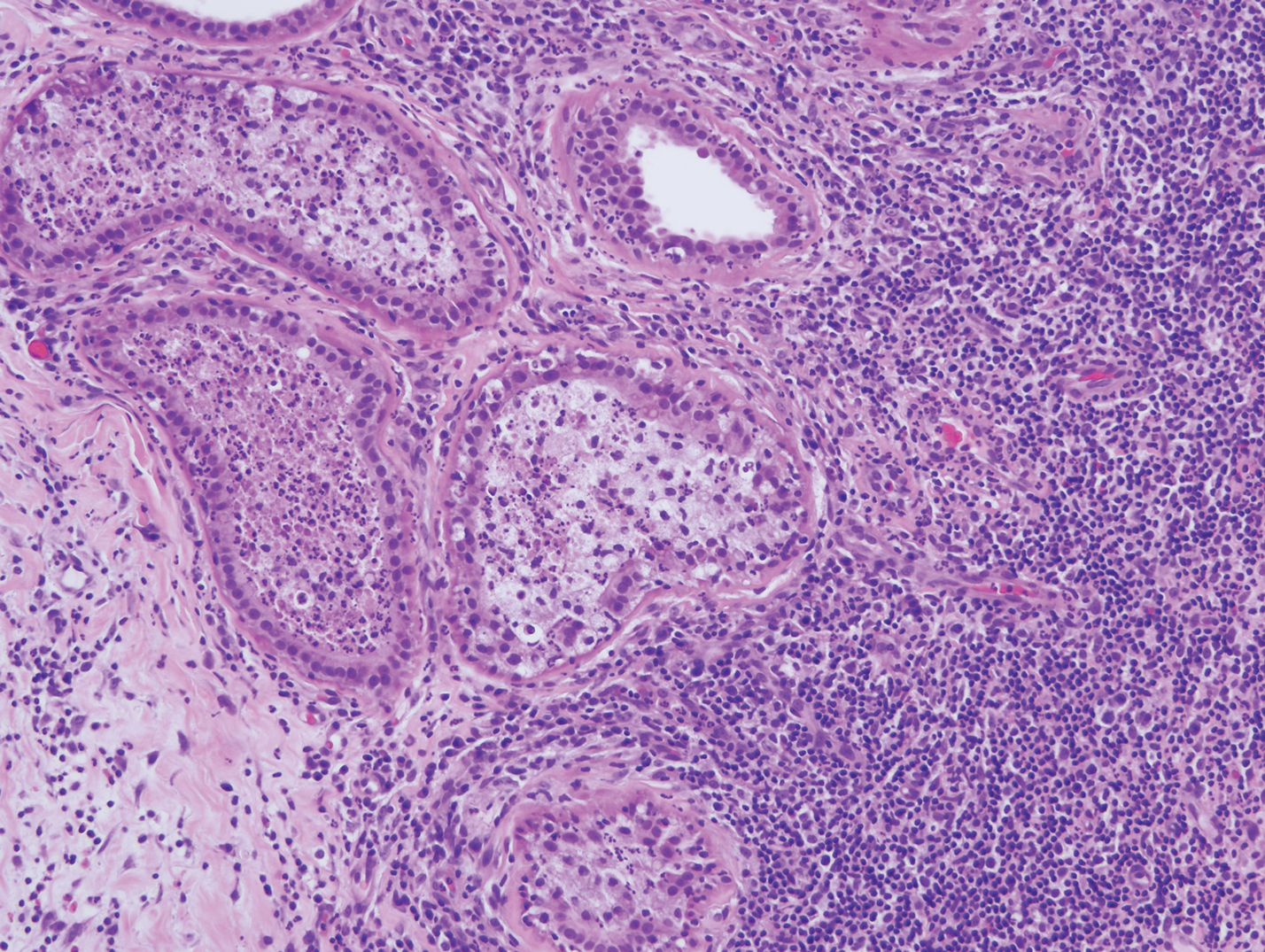

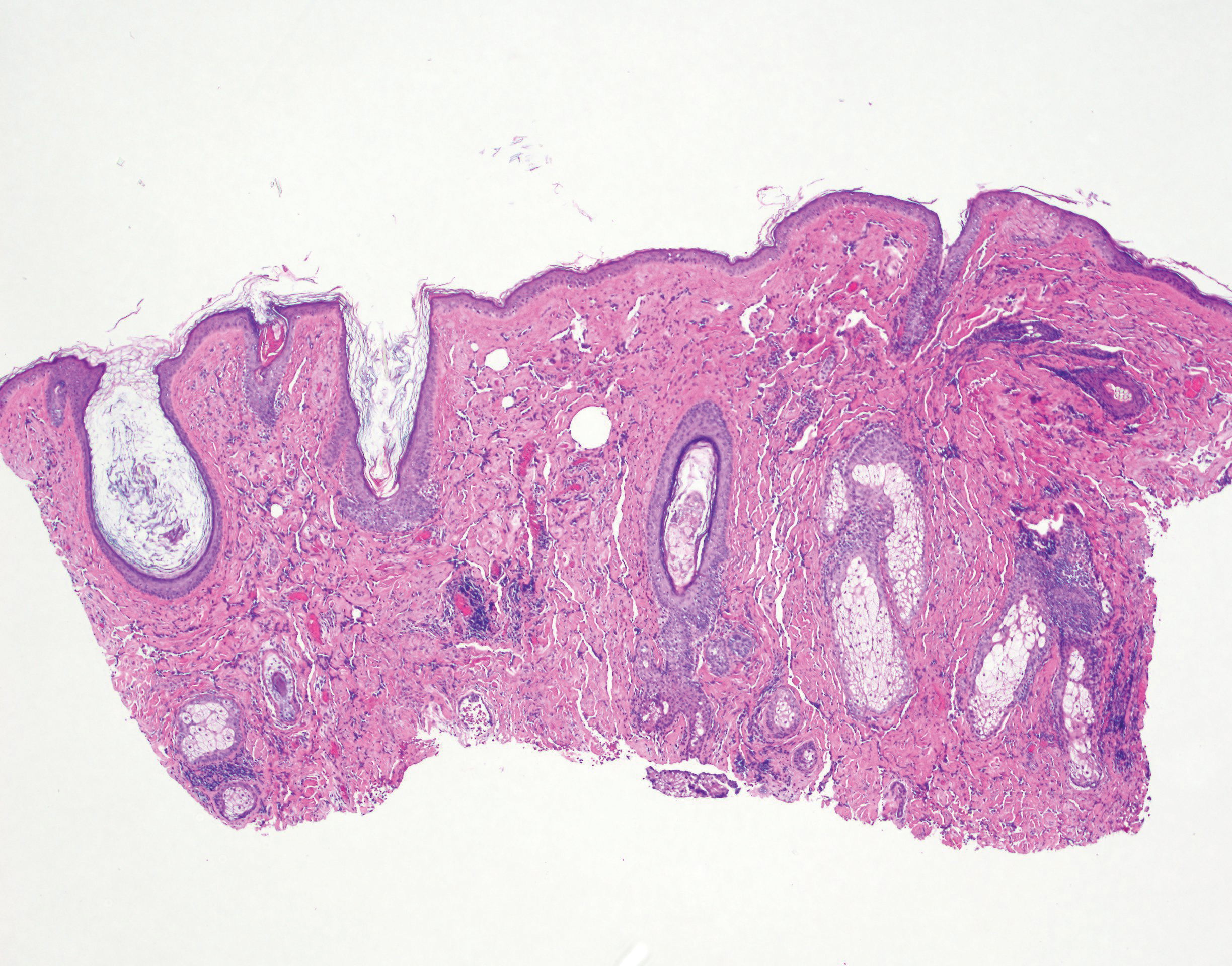

Lesions including abscesses in the groin may raise concern for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a disease of the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Typical lesions are tender subcutaneous erythematous nodules, cysts, and comedones that develop rapidly and may rupture to drain suppurative bloody discharge, subsequently healing with an atrophic scar.8 More persistent inflammation and rupture of nodules into the dermis may lead to formation of dermal tunnels with palpable cords and sinus tracts.8 Typical areas of disease involvement are in the axillae, inframammary folds, groin, or perigenital or perineal regions, with the diagnosis made on a combination of lesion morphology, location, and progression/recurrence frequency.9 Histologic examination of HS specimens can demonstrate a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, with more advanced disease characterized by increased inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, monocytes, and mast cells (Figure 2). The presence of granulomas in HS most often is of the foreign body type.9 Epithelioid granulomas noted in an area separate from inflammation in a patient with HS serve as a clue to be alert for systemic granulomatous disease.10

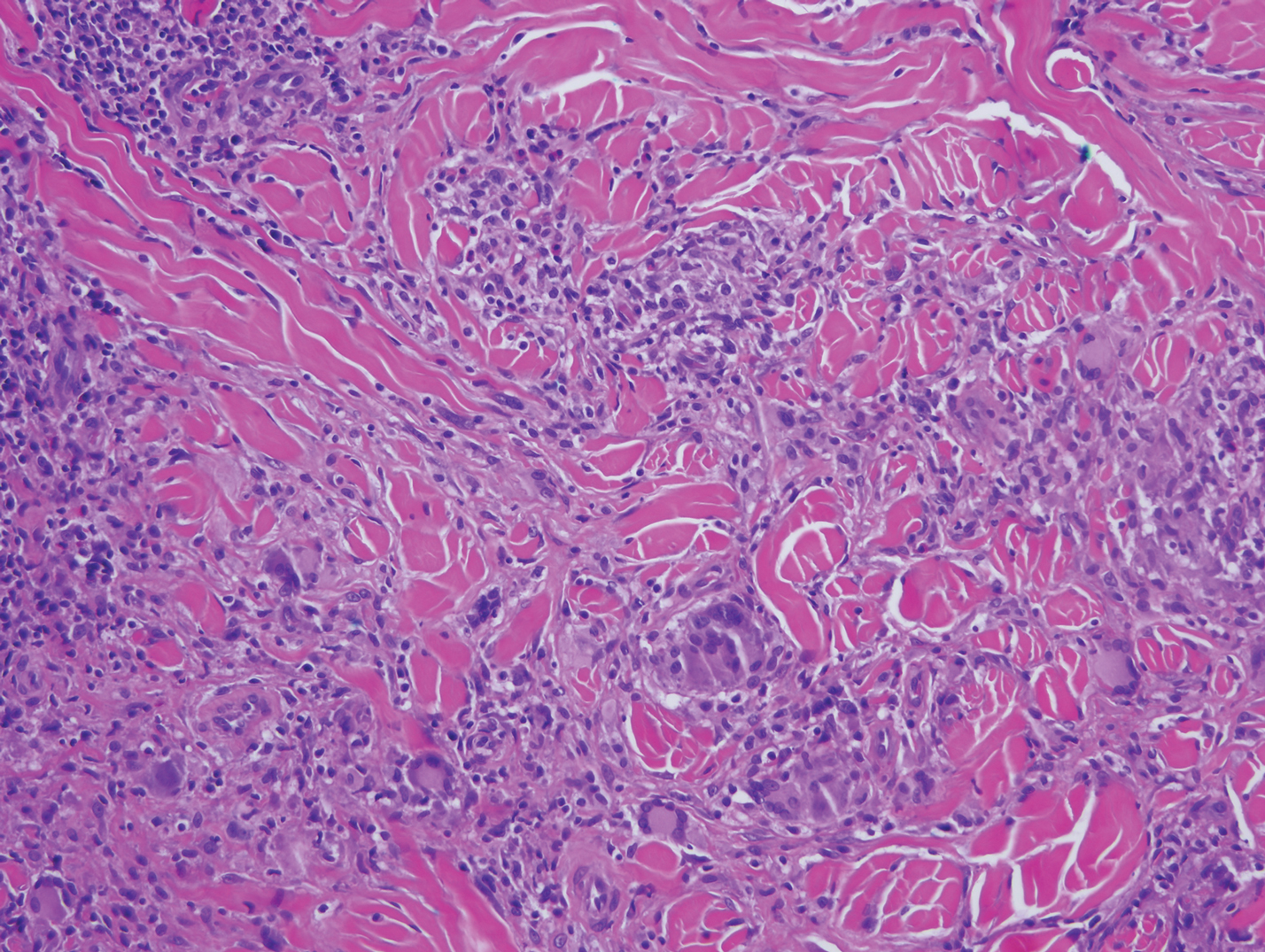

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma to show a granulomatous infiltrate; the granuloma generally is sarcoidal, though other forms are described (Figure 3).11 Beyond these granulomatous foci, the key histopathologic feature of granulomatous mycosis fungoides (GMF) is diffuse dermal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells. Epidermotropism and sparing of dermal nerves is the most critical finding in the diagnosis of GMF, especially in geographic regions where leprosy is endemic and high on the differential, as the conditions have histopathologic similarities.11,12 At the same time, lack of epidermotropism does not exclude the diagnosis of GMF.13 Clinically, GMF presentation is variable, but common findings include erythematous and hyperpigmented patches and plaques. Given the lack of clear clinical criteria, the diagnosis relies primarily on histopathologic features.11

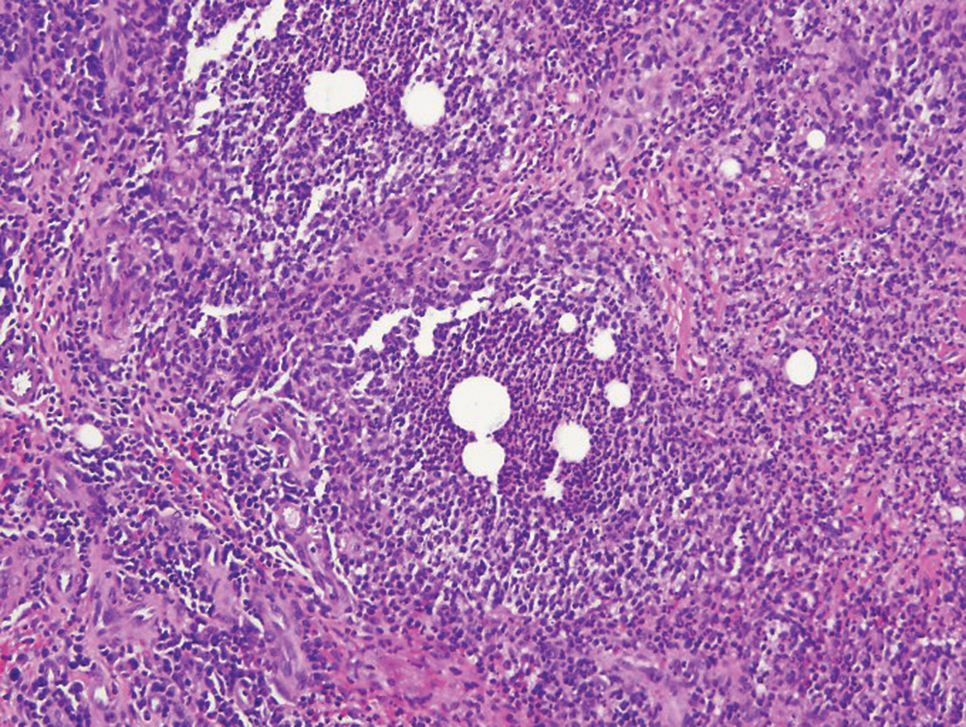

Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections may be attributed to both tuberculous and nontuberculous strains (atypical species).14 Clinical features range from small papules to large deformative plaques and ulcers.15 Histologic features also distinguish cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) from nontuberculous mycobacterial causes. Cutaneous TB shows caseous granulomas in the upper and mid dermis, while nontuberculous mycobacterial infections have more prominent neutrophil infiltration and interstitial granulomas (Figure 4).16

In cutaneous TB specifically, extrapulmonary manifestations may involve the skin in 1% to 1.5% of all TB cases, and although rare, ulcerative skin TB has been noted in one report as a nonhealing perianal ulcer that showed necrotizing granulomas on biopsy.17 Ultimately, diagnosis of cutaneous mycobacterial infection is confirmed with detection of acid-fast bacilli in the biopsy specimen.16

Diagnosis of cutaneous CD requires clinicopathologic correlation, as the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnoses of genital edema and noncaseating granulomas, respectively, are broad. Even though the clinical context was appropriate for cutaneous CD in this case, correct diagnosis required confirmatory histologic findings. Furthermore, taking multiple biopsies is prudent. In our patient, diagnostic findings only were present in the biopsy from the scrotum.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Barrick BJ, Tollefson MM, Schoch JJ, et al. Penile and scrotal swelling: an underrecognized presentation of Crohn's disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:172-177.

- Mooney EE, Walker J, Hourihane DO. Relation of granulomas to lymphatic vessels in Crohn's disease. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:335-338.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases [published online October 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184.

- Yoo SS, Mimouni D, Nikolskaia OV, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ulcerative-atrophic sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:108-112.

- Cohen GF, Wolfe CM. Recalcitrant diffuse cutaneous sarcoidosis with perianal involvement responding to adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1305-1306.

- Hoffman LK, Ghias MH, Lowes MA. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:47-54.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Hughes LE, et al. Granulomatous hidradenitis suppurativa and cutaneous Crohn's disease. Histopathology. 1993;23:111-115.

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohydrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2010;76:686-690.

- Pousa CM, Nery NS, Mann D, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides--a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:554-556.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- van Mechelen M, van der Hilst J, Gyssens IC, et al. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections: TB or not TB? Neth J Med. 2018;76:269-274.

- van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:629-638.

- De Maio F, Trecarichi EM, Visconti E, et al. Understanding cutaneous tuberculosis: two clinical cases. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:E005070.

- Wu S, Wang W, Chen H, et al. Perianal ulcerative skin tuberculosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E10836.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can involve any region of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anus but most commonly presents in the terminal ileum, colon, or small bowel with transmural inflammation, fistula formation, and knife-cut fissures among the frequently described findings. Extraintestinal manifestations may be found in the liver, eyes, and joints, with cutaneous extraintestinal manifestations occurring in up to one-third of patients.1

Crohn disease can be associated with multiple cutaneous findings, including erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous ulcers, pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans, necrotizing vasculitis, and metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2 Typical histopathologic findings seen in MCD such as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis, possibly extending to the subcutaneous fat, are not specific to MCD. Associated genital edema is thought to be a consequence of granulomatous inflammation of lymphatics. In one study reviewing specimens from 10 cases of CD, a mean of 46% of all granulomas identified on the slides (264 granulomas in total) were located proximal to lymphatic vessels, suggesting a common pathway for development of intestinal disease and genital edema.3 The differential diagnosis for penile and scrotal swelling is broad, and the diagnosis may be missed if attention is not given to the clinical history of the patient in addition to histopathologic findings.2

Skin changes in CD also can be separated into perianal disease and true metastatic disease--the former recognized when anal lesions appear associated with segmental involvement of the GI tract and the latter as ulceration of the skin separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 The term sarcoidal reaction often is used to describe histopathologic findings in cutaneous CD, as it refers to the noncaseating granulomas found in approximately 60% of all cases.4 Ultimately, the location of noncaseating granulomas within the dermis of our patient's biopsy, taken in conjunction with the clinical history and the lack of defining features for other potential etiologies (eg, polarizable material, organisms on special stains), led to the diagnosis of cutaneous CD.

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis most commonly occur as papules, plaques, and subcutaneous nodules predominantly on the face, upper back, arms, and legs. Although the histologic features of sarcoidosis are characterized by lymphocyte-poor noncaseating granulomas (Figure 1), these findings also can be seen as a consequence of multiple granulomatous causes.5,6 In a review of 48 cutaneous specimens from patients with sarcoidosis, the granulomas were found most frequently in the deep dermis (34/48 [70.8%]), with superficial dermis (21/48) and subcutaneous fat granulomas (20/48) each present in less than 50% of biopsies.5 Although less typical, cutaneous sarcoidosis also has been noted in the literature to present in the perianal and gluteal region, demonstrating dermal noncaseating granulomas on biopsy.7 One distinction in particular to be noted between sarcoid and CD is that sarcoid lesions in the skin rarely ulcerate, while the lesions of cutaneous CD often are ulcerated.4,6

Lesions including abscesses in the groin may raise concern for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a disease of the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Typical lesions are tender subcutaneous erythematous nodules, cysts, and comedones that develop rapidly and may rupture to drain suppurative bloody discharge, subsequently healing with an atrophic scar.8 More persistent inflammation and rupture of nodules into the dermis may lead to formation of dermal tunnels with palpable cords and sinus tracts.8 Typical areas of disease involvement are in the axillae, inframammary folds, groin, or perigenital or perineal regions, with the diagnosis made on a combination of lesion morphology, location, and progression/recurrence frequency.9 Histologic examination of HS specimens can demonstrate a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, with more advanced disease characterized by increased inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, monocytes, and mast cells (Figure 2). The presence of granulomas in HS most often is of the foreign body type.9 Epithelioid granulomas noted in an area separate from inflammation in a patient with HS serve as a clue to be alert for systemic granulomatous disease.10

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma to show a granulomatous infiltrate; the granuloma generally is sarcoidal, though other forms are described (Figure 3).11 Beyond these granulomatous foci, the key histopathologic feature of granulomatous mycosis fungoides (GMF) is diffuse dermal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells. Epidermotropism and sparing of dermal nerves is the most critical finding in the diagnosis of GMF, especially in geographic regions where leprosy is endemic and high on the differential, as the conditions have histopathologic similarities.11,12 At the same time, lack of epidermotropism does not exclude the diagnosis of GMF.13 Clinically, GMF presentation is variable, but common findings include erythematous and hyperpigmented patches and plaques. Given the lack of clear clinical criteria, the diagnosis relies primarily on histopathologic features.11

Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections may be attributed to both tuberculous and nontuberculous strains (atypical species).14 Clinical features range from small papules to large deformative plaques and ulcers.15 Histologic features also distinguish cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) from nontuberculous mycobacterial causes. Cutaneous TB shows caseous granulomas in the upper and mid dermis, while nontuberculous mycobacterial infections have more prominent neutrophil infiltration and interstitial granulomas (Figure 4).16

In cutaneous TB specifically, extrapulmonary manifestations may involve the skin in 1% to 1.5% of all TB cases, and although rare, ulcerative skin TB has been noted in one report as a nonhealing perianal ulcer that showed necrotizing granulomas on biopsy.17 Ultimately, diagnosis of cutaneous mycobacterial infection is confirmed with detection of acid-fast bacilli in the biopsy specimen.16

Diagnosis of cutaneous CD requires clinicopathologic correlation, as the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnoses of genital edema and noncaseating granulomas, respectively, are broad. Even though the clinical context was appropriate for cutaneous CD in this case, correct diagnosis required confirmatory histologic findings. Furthermore, taking multiple biopsies is prudent. In our patient, diagnostic findings only were present in the biopsy from the scrotum.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that can involve any region of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anus but most commonly presents in the terminal ileum, colon, or small bowel with transmural inflammation, fistula formation, and knife-cut fissures among the frequently described findings. Extraintestinal manifestations may be found in the liver, eyes, and joints, with cutaneous extraintestinal manifestations occurring in up to one-third of patients.1

Crohn disease can be associated with multiple cutaneous findings, including erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous ulcers, pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans, necrotizing vasculitis, and metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2 Typical histopathologic findings seen in MCD such as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis, possibly extending to the subcutaneous fat, are not specific to MCD. Associated genital edema is thought to be a consequence of granulomatous inflammation of lymphatics. In one study reviewing specimens from 10 cases of CD, a mean of 46% of all granulomas identified on the slides (264 granulomas in total) were located proximal to lymphatic vessels, suggesting a common pathway for development of intestinal disease and genital edema.3 The differential diagnosis for penile and scrotal swelling is broad, and the diagnosis may be missed if attention is not given to the clinical history of the patient in addition to histopathologic findings.2

Skin changes in CD also can be separated into perianal disease and true metastatic disease--the former recognized when anal lesions appear associated with segmental involvement of the GI tract and the latter as ulceration of the skin separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 The term sarcoidal reaction often is used to describe histopathologic findings in cutaneous CD, as it refers to the noncaseating granulomas found in approximately 60% of all cases.4 Ultimately, the location of noncaseating granulomas within the dermis of our patient's biopsy, taken in conjunction with the clinical history and the lack of defining features for other potential etiologies (eg, polarizable material, organisms on special stains), led to the diagnosis of cutaneous CD.

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis most commonly occur as papules, plaques, and subcutaneous nodules predominantly on the face, upper back, arms, and legs. Although the histologic features of sarcoidosis are characterized by lymphocyte-poor noncaseating granulomas (Figure 1), these findings also can be seen as a consequence of multiple granulomatous causes.5,6 In a review of 48 cutaneous specimens from patients with sarcoidosis, the granulomas were found most frequently in the deep dermis (34/48 [70.8%]), with superficial dermis (21/48) and subcutaneous fat granulomas (20/48) each present in less than 50% of biopsies.5 Although less typical, cutaneous sarcoidosis also has been noted in the literature to present in the perianal and gluteal region, demonstrating dermal noncaseating granulomas on biopsy.7 One distinction in particular to be noted between sarcoid and CD is that sarcoid lesions in the skin rarely ulcerate, while the lesions of cutaneous CD often are ulcerated.4,6

Lesions including abscesses in the groin may raise concern for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a disease of the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Typical lesions are tender subcutaneous erythematous nodules, cysts, and comedones that develop rapidly and may rupture to drain suppurative bloody discharge, subsequently healing with an atrophic scar.8 More persistent inflammation and rupture of nodules into the dermis may lead to formation of dermal tunnels with palpable cords and sinus tracts.8 Typical areas of disease involvement are in the axillae, inframammary folds, groin, or perigenital or perineal regions, with the diagnosis made on a combination of lesion morphology, location, and progression/recurrence frequency.9 Histologic examination of HS specimens can demonstrate a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate, with more advanced disease characterized by increased inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, monocytes, and mast cells (Figure 2). The presence of granulomas in HS most often is of the foreign body type.9 Epithelioid granulomas noted in an area separate from inflammation in a patient with HS serve as a clue to be alert for systemic granulomatous disease.10

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma to show a granulomatous infiltrate; the granuloma generally is sarcoidal, though other forms are described (Figure 3).11 Beyond these granulomatous foci, the key histopathologic feature of granulomatous mycosis fungoides (GMF) is diffuse dermal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells. Epidermotropism and sparing of dermal nerves is the most critical finding in the diagnosis of GMF, especially in geographic regions where leprosy is endemic and high on the differential, as the conditions have histopathologic similarities.11,12 At the same time, lack of epidermotropism does not exclude the diagnosis of GMF.13 Clinically, GMF presentation is variable, but common findings include erythematous and hyperpigmented patches and plaques. Given the lack of clear clinical criteria, the diagnosis relies primarily on histopathologic features.11

Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections may be attributed to both tuberculous and nontuberculous strains (atypical species).14 Clinical features range from small papules to large deformative plaques and ulcers.15 Histologic features also distinguish cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) from nontuberculous mycobacterial causes. Cutaneous TB shows caseous granulomas in the upper and mid dermis, while nontuberculous mycobacterial infections have more prominent neutrophil infiltration and interstitial granulomas (Figure 4).16

In cutaneous TB specifically, extrapulmonary manifestations may involve the skin in 1% to 1.5% of all TB cases, and although rare, ulcerative skin TB has been noted in one report as a nonhealing perianal ulcer that showed necrotizing granulomas on biopsy.17 Ultimately, diagnosis of cutaneous mycobacterial infection is confirmed with detection of acid-fast bacilli in the biopsy specimen.16

Diagnosis of cutaneous CD requires clinicopathologic correlation, as the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnoses of genital edema and noncaseating granulomas, respectively, are broad. Even though the clinical context was appropriate for cutaneous CD in this case, correct diagnosis required confirmatory histologic findings. Furthermore, taking multiple biopsies is prudent. In our patient, diagnostic findings only were present in the biopsy from the scrotum.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Barrick BJ, Tollefson MM, Schoch JJ, et al. Penile and scrotal swelling: an underrecognized presentation of Crohn's disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:172-177.

- Mooney EE, Walker J, Hourihane DO. Relation of granulomas to lymphatic vessels in Crohn's disease. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:335-338.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases [published online October 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184.

- Yoo SS, Mimouni D, Nikolskaia OV, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ulcerative-atrophic sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:108-112.

- Cohen GF, Wolfe CM. Recalcitrant diffuse cutaneous sarcoidosis with perianal involvement responding to adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1305-1306.

- Hoffman LK, Ghias MH, Lowes MA. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:47-54.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Hughes LE, et al. Granulomatous hidradenitis suppurativa and cutaneous Crohn's disease. Histopathology. 1993;23:111-115.

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohydrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2010;76:686-690.

- Pousa CM, Nery NS, Mann D, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides--a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:554-556.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- van Mechelen M, van der Hilst J, Gyssens IC, et al. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections: TB or not TB? Neth J Med. 2018;76:269-274.

- van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:629-638.

- De Maio F, Trecarichi EM, Visconti E, et al. Understanding cutaneous tuberculosis: two clinical cases. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:E005070.

- Wu S, Wang W, Chen H, et al. Perianal ulcerative skin tuberculosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E10836.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Barrick BJ, Tollefson MM, Schoch JJ, et al. Penile and scrotal swelling: an underrecognized presentation of Crohn's disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:172-177.

- Mooney EE, Walker J, Hourihane DO. Relation of granulomas to lymphatic vessels in Crohn's disease. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:335-338.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases [published online October 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184.

- Yoo SS, Mimouni D, Nikolskaia OV, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ulcerative-atrophic sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:108-112.

- Cohen GF, Wolfe CM. Recalcitrant diffuse cutaneous sarcoidosis with perianal involvement responding to adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1305-1306.

- Hoffman LK, Ghias MH, Lowes MA. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:47-54.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Hughes LE, et al. Granulomatous hidradenitis suppurativa and cutaneous Crohn's disease. Histopathology. 1993;23:111-115.

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohydrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2010;76:686-690.

- Pousa CM, Nery NS, Mann D, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides--a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:554-556.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- van Mechelen M, van der Hilst J, Gyssens IC, et al. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections: TB or not TB? Neth J Med. 2018;76:269-274.

- van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:629-638.

- De Maio F, Trecarichi EM, Visconti E, et al. Understanding cutaneous tuberculosis: two clinical cases. JMM Case Rep. 2016;3:E005070.

- Wu S, Wang W, Chen H, et al. Perianal ulcerative skin tuberculosis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E10836.

A 44-year-old man presented for evaluation of self-described "skin ripping" on the penis with penile and scrotal edema of 1 year's duration. He had a history of bowel symptoms and anorectal fistula of 3 years' duration. Purulent penile drainage and inguinal lymphadenopathy were noted on physical examination. Excisional biopsies of the scrotum and penis were performed. Special stains for organisms were negative.

Angiosarcoma Imitating a Morpheaform Basal Cell Carcinoma

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

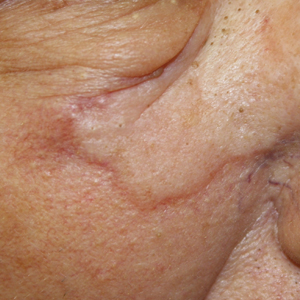

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

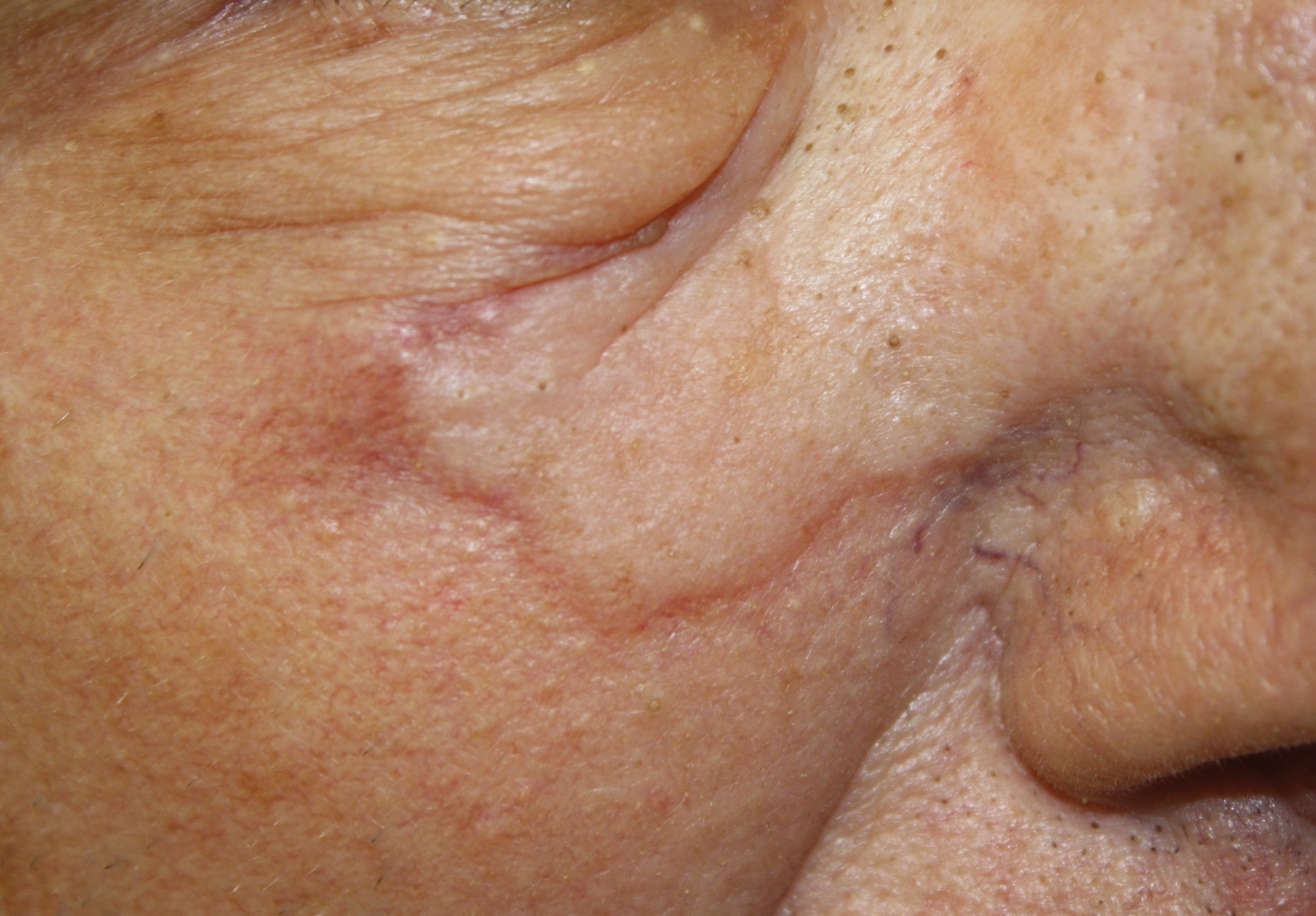

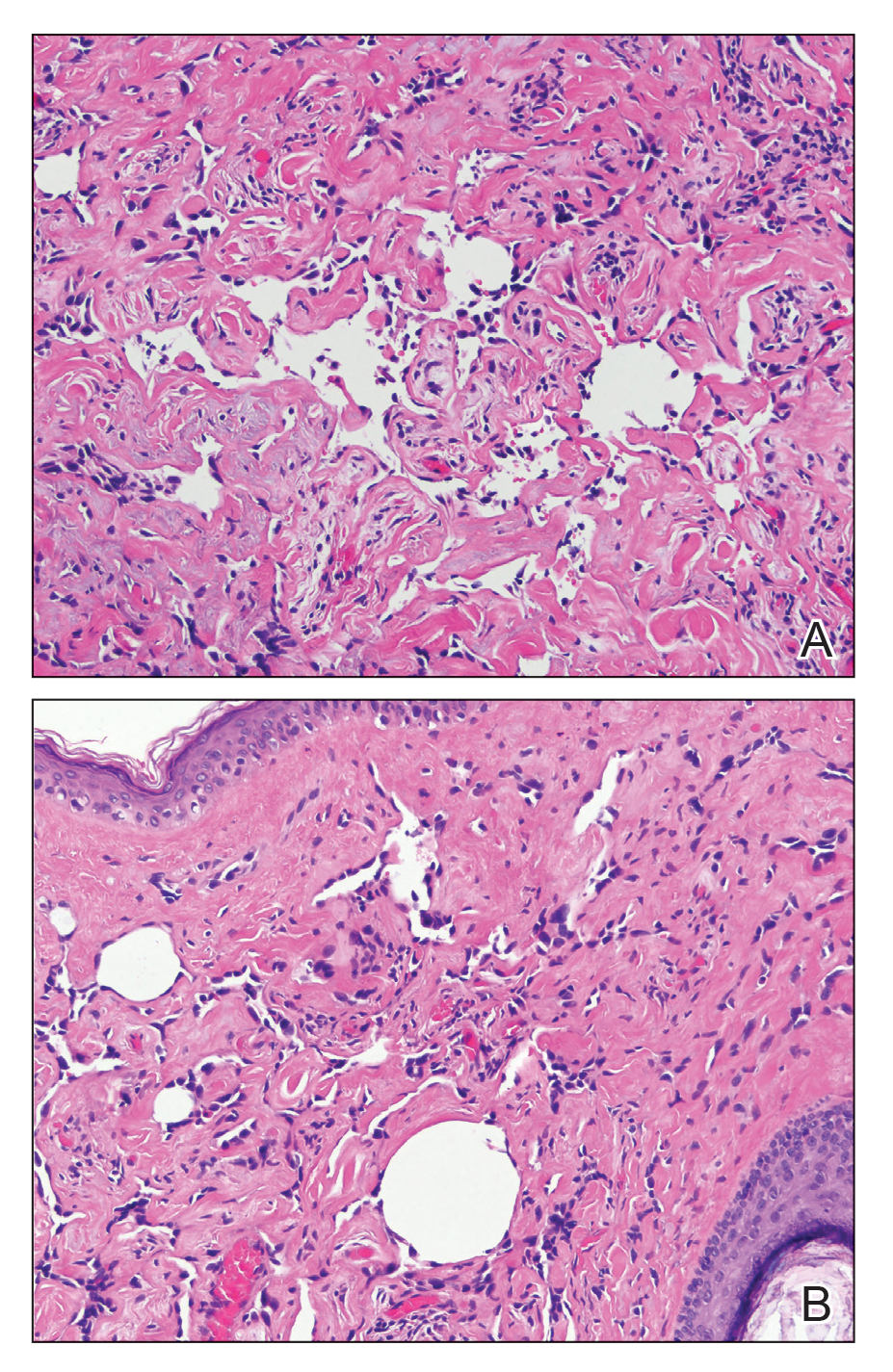

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

To the Editor:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common of the nonmelanoma skin cancers and is a highly curable skin growth.1,2 Conversely, angiosarcomas are aggressive vascular tumors of endothelial origin that classically appear as reddish purple patches or plaques that exhibit rapid growth and invasion.3 Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas are the most common type of this soft tissue tumor, occurring most often in the head and neck regions in men older than 70 years.4,5 Other types of angiosarcomas include those associated with radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema. Postradiation angiosarcomas have been most frequently reported after treatment of breast cancer and appear as infiltrative plaques over the irradiated area.4,5 Patients with chronic lymphedema, which most commonly is related to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer (90% of cases), may develop angiosarcoma presenting as a violaceous indurated plaque.5 Although angiosarcomas most often are seen with these distinct clinical characteristics, especially their violaceous color, they have been shown to mimic a few other skin disorders such as eczema and keratoacanthoma, but a limited number of cases of angiosarcoma mimicking BCC have been reported.1,6,7 We present a case of an elderly man with a unique presentation of a lesion that clinically appeared as a morpheaform BCC but was confirmed to be an angiosarcoma on histopathology.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a flesh-colored plaque on the face that initially had developed 2 years prior on the right central malar cheek. Computed tomography of the head and neck 1 year prior, which the patient reported was for workup of the lesion, was found to be negative; however, these medical records were not obtained for confirmation. The lesion had been stable in size and remained flesh colored until 6 months prior to the current presentation when it exhibited a rapid increase in size. An initial biopsy was performed 1 month prior to presentation by an outside dermatology office and had been read as an angiosarcoma.

Physical examination revealed a 6-cm, flesh-colored, indurated, ill-defined plaque distributed on the right malar cheek below the eye and extending to the nasal bridge (Figure 1). There was no cervical or facial lymphadenopathy. The clinical features resembled a morpheaform BCC, and the lesion did not exhibit any reddish or purple color indicating it was of vascular origin. However, due to the prior histopathology report and recent rapid enlargement, a repeat sampling with a larger punch biopsy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. Histopathology demonstrated multiple atypical vascular channels lined by hyperchromatic cells extending from the upper dermis to the base of the biopsy site (Figure 2). Large, oval, atypical nuclei were present in multiple endothelial cells in the vascular channels, with some forming irregularly contoured and slitlike formations (Figure 3). Immunochemical staining was intensely and uniformly positive for CD31 and CD34, both endothelial markers. Diffuse positive staining with CD31 is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of angiosarcoma.4 Other pertinent staining demonstrated 2+ positivity for factor VIII and 1+ positivity for D2-40; CD45, AE1/AE3, S-100, and human herpesvirus 8 were negative, consistent with angiosarcoma. The patient was referred to radiation oncology and otolaryngology at our Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Center for further investigation of the extent of the disease and discussion of treatment. Computed tomography of the head and neck region at this time showed extensive disease extending into the medial canthal area without metastasis. Due to the extent of disease and facial location, he was not deemed a candidate for surgery. He was treated with 6 weeks of targeted radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. He tolerated this treatment with minimal side effects and was found to be free from clinical disease 1 year after diagnosis. He was followed for 20 months by our Multidisciplinary Oncology Clinic without recurrence of his disease but was then lost to follow-up.

This case illustrates a rare presentation of an angiosarcoma clinically mimicking a BCC, which has been described in a small number of case reports and retrospective reviews. One study of 656 patients diagnosed with BCC based on clinical features revealed that 48 of these lesions were proven to be a BCC-mimicking lesion and only 1 was an angiosarcoma.1 Cutaneous lesions that appear on physical examination to be a highly curable BCC may not induce the same urgency for treatment as an angiosarcoma. Although the clinical presentation may mimic a morpheaform BCC, our case demonstrates that it is imperative to include angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis and underscores the utility of tissue sampling. Angiosarcoma has a poor overall 5-year survival rate, and patients often are found to have multiple metastatic lesions at diagnosis. However, diagnosis prior to metastasis may improve prognosis.8

Our patient’s angiosarcoma did not exhibit metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and he was able to achieve a favorable outcome. However, the 5-year survival rate is only 40%, and close clinical monitoring after diagnosis is required.8 Including angiosarcoma in the differential diagnosis for our patient, particularly upon lesion appearance 2 years prior, may have resulted in diagnosis antecedent to local invasion, possibly providing more treatment options. Employing a higher index of clinical suspicion for angiosarcoma may lead to decreased mortality in other patients due to increased detection.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

- Kim HS, Kim TW, Mun JH, et al. Basal cell carcinoma–mimicking lesions in Korean clinical settings. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:431-436.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294:681-690.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012.

- Dosset LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1915-1942.

- Kong YL, Chandran NS, Goh SG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp mimicking a keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18566.

- Trinh NQ, Rashed I, Hutchens KA, et al. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma masquerading as eczema: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:906426.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors. a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473-479.

Practice Points

- Angiosarcoma is an aggressive vascular tumor with a poor prognosis.

- Angiosarcomas can arise in the setting of chronic lymphedema or prior radiation therapy or can arise spontaneously.

- Classically, angiosarcoma presents as a violaceous patch or plaque but occasionally can exhibit atypical clinical features. Angiosarcomas should be considered on the differential for any changing plaque on the head or neck.