User login

Right place, right time: Facilitating end-of-life conversations

As the geriatric population continues to grow and treatment advances blur the lines between improving the length of life vs improving its quality, end-of-life (EOL) conversations are becoming increasingly important. These discussions are a crucial part of the advance care planning (ACP) process, in which patients discuss their treatment preferences and values with their caregiver/surrogate decision maker and health care provider to ultimately improve EOL decision-making and care. 1,2

EOL conversations are most helpful when incorporated in the outpatient setting as part of the patient’s ongoing health care plan or when initiating treatment for a chronic or life-threatening disease. Because family physicians promote general wellness, understand the patient’s health status and medical history, and have an ongoing—and often longstanding—relationship with patients and their families, we are ideally positioned to engage patients in EOL discussions. However, these conversations can be challenging in the outpatient setting, and often clinicians struggle not only to find ways to raise the subject, but also to find the time to have these supportive, meaningful conversations.3

In this article, we will address the importance of having EOL discussions in the outpatient setting, specifically about advance directives (ADs), and the reasons why patients and physicians might avoid these discussions. The role of palliative care in EOL care, along with its benefits and methods for overcoming patient and physician barriers to its successful use, are reviewed. Finally, we examine specific challenges associated with discussing EOL care with patients with decreased mental capacity, such as those with dementia, and provide strategies to successfully facilitate EOL discussions in these populations.

Moving patients toward completion of advance directives

Although many older patients express a desire to document their wishes before EOL situations arise, they may not fully understand the benefits of an AD or how to complete one. 4 Often the family physician is best equipped to address the patient’s concerns and discuss their goals for EOL care, as well as the potential situations that might arise.

Managing an aging population. Projections suggest that primary care physicians will encounter increasing numbers of geriatric patients in the next 2 decades. Thus it is essential for those in primary care to receive proper training during their residency for the care of this group of patients. According to a group of academic educators and geriatricians from internal medicine and family medicine whose goal was to define a set of minimal and essential competencies in the care of older adults, this includes training on how to discuss and document “advance care planning and goals of care with all patients with chronic or complex illness,” as well as how to differentiate among “types of code status, health care proxies, and advanced directives” within the state in which training occurs. 5

Educate patients and ease fears. Patients often avoid EOL conversations or wait for their family physician to start the conversation. They may not understand how ADs can help guide care or they may believe they are “too healthy” to have these conversations at this time. 4 Simply asking about existing ADs or providing forms to patients during an outpatient visit can open the door to more in-depth discussions. Some examples of opening phrases include:

- Do you have a living will or durable power of attorney for health care?

- Have you ever discussed your health care wishes with your loved ones?

- Who would you want to speak for you regarding your health care if you could not speak for yourself? Have you discussed your health care wishes with that person?

By normalizing the conversation as a routine part of comprehensive, patient-centered care, the family physician can allay patient fears, foster open and honest conversations, and encourage ongoing discussions with loved ones as situations arise.6

Continue to: When ADs are executed...

When ADs are executed, patients often fail to have meaningful conversations with their surrogates about specific treatment wishes or EOL scenarios. As a result, the surrogate may not feel prepared to serve as a proxy decision maker or may find the role extremely stressful.7 Physicians should encourage open conversations between patients and their surrogates about potential EOL scenarios when possible. When possible and appropriate, it is also important to encourage the patient to include the surrogate in future outpatient visits so that the surrogate can understand the patient’s health status and potential decisions they may need to make.

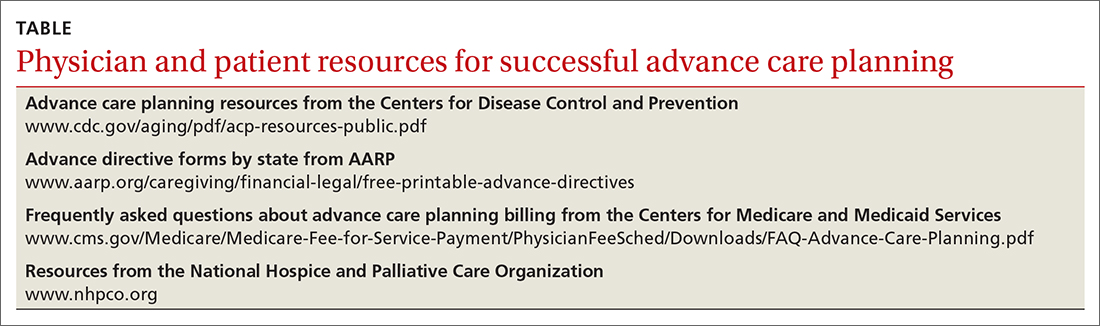

Don’t overlook clinician barriers. Family physicians also might avoid AD discussions because they do not understand laws that govern ADs, which vary from state to state. Various online resources for patients and physicians exist that clarify state-specific regulations and provide state-specific forms (TABLE).

Time constraints present another challenge for family physicians. This can be addressed by establishing workflows that include EOL elements. Also, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has provided separate billing codes for AD discussion based on time spent explaining and discussing how to complete forms.8 CPT codes 99497 and 99498 are time-based codes that cover the first 30 minutes and each additional 30 minutes, respectively, of time spent explaining and discussing how to complete standard forms in a face-to-face setting (TABLE).9 CMS also includes discussion of AD documents as an optional element of the annual Medicare wellness visit.8

Improve quality of life for patients with any serious illness

Unlike hospice, which focuses on providing comfort rather than cure in the final months of a patient’s life, palliative care strives to prevent and relieve the patient’s suffering from a serious illness that is not immediately life-threatening. Palliative care focuses on the early identification, careful assessment, and treatment of the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms associated with a patient’s condition(s).10,11 It has been well established that palliative care has a positive effect on many clinical outcomes including symptom burden, quality of life, satisfaction with care, and survival.12-14 Patients who receive palliative care consultation also tend to perceive a higher quality of care.15

Conversations lead to better outcomes. Palliative care consultation is being increasingly used in the outpatient setting and can be introduced early in a disease process. Doing so provides an additional opportunity for the family physician to introduce an EOL discussion. A comparison of outcomes between patients who had initial inpatient palliative care consultation vs outpatient palliative care referral found that outpatient referral improved quality EOL care and was associated with significantly fewer emergency department visits (68% vs 48%; P < .001) and hospital admissions (86% vs 52%; P < .001), as well as shorter hospital stays in the last 30 days of life (3-11 vs 5-14 days; P = .01).14 Despite these benefits, 60% to 90% of patients with a serious illness report never having discussed EOL care issues with their clinician.16,17

Continue to: Early EOL discussions...

Early EOL discussions have also been shown to have a positive impact on families. In a US study, family members stated that timely EOL care discussions allowed them to make use of hospice and palliative care services sooner and to make the most of their time with the patient.18

Timing and communication are key

Logistically it can be difficult to gather the right people (patient, family, etc) in the right place and at the right time. For physicians, the most often cited barriers include inadequate time to conduct an EOL discussion, 19 a perceived lack of competence in EOL conversations, 1,20 difficulty navigating patient readiness, 21 and a fear of destroying hope due to prognostic uncertainty. 19,20

A prospective, observational study used the Quality of Communication (QOC) questionnaire to assess life-sustaining treatment preferences, ACP, and the quality of EOL care communication in Dutch outpatients with clinically stable but severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 105) or congestive heart failure (n = 80). The QOC questionnaire is a validated instrument that asks patients to rate their physician on several communication skills from 0 (“the very worst” or “My doctor didn’t do this”) to 10 (“the very best”). In this study, quality communication was identified by patients as one of the most important skills for physicians to provide adequate EOL care. 22 While QOC ratings were high for general communication skills (median, 8.0 points), quality EOL care communication was rated very low (median, 0.0 points). Researchers say that this was primarily because most EOL topics were not discussed—especially spirituality, prognosis, and what dying might be like. 22 In a secondary analysis that evaluated quality of EOL care communication during 1-year follow-up of patients with advanced chronic organ failure (n = 265) with the QOC questionnaire, patient ratings improved to moderate to good (medians, 6-8 points) when these topics were addressed. 23

Pick a strategy and prepare. As the older population continues to grow, the demands of palliative care management cannot be met by specialists alone and the responsibility of discussing EOL care with patients and their families will increasingly fall to family physicians as well. 24 Several strategies and approaches have evolved to assist family physicians with acquiring the skills to conduct productive EOL discussions. These include widely referenced resources, such as VitalTalk 25 and the ABCDE Plan. 26 VitalTalk teaches skills to help clinicians navigate difficult conversations, 25 and the “ABCDE” method provides a pneumonic for recommendations for how to deliver bad news ( A dvance preparation; B uild a therapeutic environment/relationship; C ommunicate well; D eal with patient and family reactions; E ncourage and validate emotions). 26

Other strategies include familiarizing oneself with the patient’s medical history and present situation (eg, What are the patient’s symptoms? What do other involved clinicians think and recommend? What therapies have been attempted? What are the relevant social and emotional dynamics?); asking the patient who they want present for the EOL conversation; scheduling the conversation for when you can set aside an appropriate amount of time and in a private place where there will be no interruptions; and going into the meeting with your goal in mind, whether it is to deliver bad news, clarify the prognosis, establish goals of care, or communicate the patient’s goals and wishes for the EOL to those in attendance. 27 It can be very helpful to begin the conversation by clarifying what the patient and their family/surrogate understand about the current diagnosis and prognosis. From there, the family physician can present a “headline” that prepares them for the current conversation (eg, “I have your latest test results, and I need to share some serious news”). This can facilitate a more detailed discussion of the patient’s and surrogate’s goals of care. Using these strategies, family physicians can lead a productive EOL discussion that benefits everyone.

Continue to: How to navigate EOL discussions with patients with dementia

How to navigate EOL discussions with patients with dementia

EOL discussions with patients with dementia become even more complex and warrant specific discussion because one must consider the timing of such discussions, 2,28,29 the trajectory of the disease and how that affects the patient’s capacity for EOL conversations, and the critical importance of engaging caregivers/surrogate decision makers in these discussions. 2 ACP provides an opportunity for the physician, patient, and caregiver/surrogate to jointly explore the patient’s values, beliefs, and preferences for care through the EOL as the disease progresses and the patient’s decisional capacity declines.

Ensure meaningful participation with timing. EOL discussions should occur while the patient has the cognitive capacity to actively participate in the planning process. A National Institutes of Health stage I behavioral intervention development trial evaluated a structured psychoeducational intervention, known as SPIRIT (Sharing Patient’s Illness Representation to Increase Trust), that aimed to promote cognitive and emotional preparation for EOL decisions for patients and their surrogates.28 It was found to be effective in patients, including those with end-stage renal disease and advanced heart failure, and their surrogates.28 Preliminary results from the trial confirmed that people with mild-to-moderate dementia (recent Montreal Cognitive Assessment score ≥ 13) are able to participate meaningfully in EOL discussions and ACP.28

Song et al29 adapted SPIRIT for use with patients with dementia and conducted a feasibility study with 23 patient-surrogate dyads.The mixed-methods study involved an expert panel review of the adapted SPIRIT, followed by a randomized trial with qualitative interviews. All 23 patients with dementia, including 14 with moderate dementia, were able to articulate their values and EOL preferences somewhat or very coherently (91.3% inter-rater reliability).29 In addition, dyad care goal congruence (agreement between patient’s EOL preferences and surrogate’s understanding of those preferences) and surrogate decision-making confidence (comfort in performing as a surrogate) were high and patient decisional conflict (patient difficulty in weighing the benefits and burdens of life-sustaining treatments and decision-making) was low, both at baseline as well as post intervention.29 Although preparedness for EOL decision-making outcome measures did not change, people with dementia and their surrogates perceived SPIRIT to be beneficial, particularly in helping them be on the same page.29

The randomized trial portion of the study (phase 2) continues to recruit 120 patient-surrogate dyads. Patient and surrogate self-reported preparedness for EOL decision-making are the primary outcomes, measured at baseline and 2 to 3 days post intervention. The estimated study completion date is May 31, 2022.30

Evidence-based clinical guidance can improve the process. Following the Belgian Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s procedures as a sample methodology, Piers et al2 developed evidence-based clinical recommendations for providers to use in the practical application of ACP in their care of patients with dementia.The researchers searched the literature; developed recommendations based on the evidence obtained, as well as their collective expert opinion; and performed validation using expert and end-user feedback and peer review. The study resulted in 32 recommendations focused on 8 domains that ranged from the beginning of the process (preconditions for optimal implementation of ACP) to later stages (ACP when it is difficult/no longer possible to communicate).2Specific guidance for ACP in dementia care include the following:

- ACP initiation. Begin conversations around the time of diagnosis, continue them throughout ongoing care, and revisit them when changes occur in the patient’s health, financial, or residential status.

- ACP conversations. Use conversations to identify significant others in the patient’s life (potential caregivers and/or surrogate decision makers) and explore the patient’s awareness of the disease and its trajectory. Discuss the patient’s values and beliefs, as well as their fears about, and preferences for, future care and the EOL.

- Role of significant others in the ACP process. Involve a patient’s significant others early in the ACP process, educate them about the surrogate decision-maker role, assess their disease awareness, and inform them about the disease trajectory and anticipated EOL decisions. 2

Continue to: Incorporate and document patients' values and preferences with LEAD

Incorporate and document patients’ values and preferences with LEAD. Dassel et al31 developed the Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia (LEAD) tool, which is a validated dementia-focused EOL planning tool that can be used to promote discussion and document a patient’s care preferences and values within the context of their changing cognitive ability.Dassel et al31 used a 4-phase mixed-method design that included (1) focus groups of patients with early-stage dementia and family caregivers, (2) clinical utility evaluation by content experts, (3) instrument completion sampling to evaluate its psychometric properties, and (4) additional focus groups to inform how the instrument should be used by families and in clinical practice.Six scales with high internal consistency and high test-retest reliability were identified: 3 scales represented patient values (concern about being a burden, the importance of quality [vs length] of life, and the preference for autonomy in decision-making) and 3 scales represented patient preferences (use of life-prolonging measures, controlling the timing of death, and the location of EOL care).31

The LEAD Guide can be used as a self-assessment tool that is completed individually and then shared with the surrogate decision maker and health care provider.32 It also can be used to guide conversations with the surrogate and physician, as well as with trusted family and friends. Using this framework, family physicians can facilitate EOL planning with the patient and their surrogate that is based on the patient’s values and preferences for EOL care prior to, and in anticipation of, the patient’s loss of decisional capacity.31

Facilitate discussions that improve outcomes

Conversations about EOL care are taking on increased importance as the population ages and treatments advance. Understanding the concerns of patients and their surrogate decision makers, as well as the resources available to guide these difficult discussions ( TABLE ), will help family physicians conduct effective conversations that enhance care, reduce the burden on surrogate decision makers, and have a positive impact on many clinical outcomes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shirley Bodi, MD, 3000 Arlington Avenue, Department of Family Medicine, Dowling Hall, Suite 2200, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 43614; Shirley.Bodi2@utoledo.edu

1. Bergenholtz Heidi, Timm HU, Missel M. Talking about end of life in general palliative care – what’s going on? A qualitative study on end-of-life conversations in an acute care hospital in Denmark. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18:62. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0448-z

2. Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, et al. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:88. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0332-2

3. Tunzi M, Ventres W. A reflective case study in family medicine advance care planning conversations. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:108-114. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.180198

4. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:31-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02093.x

5. Williams BC, Warshaw G, Fabiny AR, et al. Medicine in the 21st century: recommended essential geriatrics competencies for internal medicine and family medicine residents. J Grad Med Ed. 2010;2:373-383. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00065.1

6. Alano G, Pekmezaris R, Tai J, et al. Factors influencing older adults to complete advance directives. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:267-275. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000064

7. Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:336-346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008

8. Edelberg C. Advance care planning with and without an annual wellness visit. Ed Management website. June 1, 2016. Accessed November 16, 2021. ww.reliasmedia.com/articles/137829-advanced-care-planning-with-and-without-an-annual-wellness-visit

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Frequently asked questions about billing the physician fee schedule for advance care planning services. July 14, 2016. Accessed December 20, 2021. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/FAQ-Advance-Care-Planning.pdf

10. World Health Organization. Palliative care fact sheet. August 5, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

11. National Institute on Aging. What are palliative care and hospice care? Reviewed May 14, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care#palliative-vs-hospice

12. Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat, SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83-91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83

13. Muir JC, Daley F, Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:126-135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.017

14. Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743-1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628

15. Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, e al. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142:128-133. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2222

16. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:195-204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809

17. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patients mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665

18. Park E, Check DK, Yopp JM, et al. An exploratory study of end-of-life prognostic communication needs as reported by widowed fathers due to cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1471-1476. doi: 10.1002/pon.3757

19. Tavares N, Jarrett N, Hunt K, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care conversations in COPD: a systematic literature review. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3:00068-2016. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00068-2016

20. Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:507-517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823

21. Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035

22. Janssen DJA, Spruit MA, Schols JMGA, et al. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest. 2011;139:1081-1088. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1753

23. Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. Patient-clinician communication about end-of-life care on patients with advanced chronic organ failure during one year. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1109-1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.008

24. Brighton LJ, Bristowe K. Communication in palliative care: talking about the end of life, before the end of life. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:466-470. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133368

25. VitalTalk website. Accessed December 20, 2021. vitaltalk.org

26. Rabow MQ, McPhee SJ. Beyond breaking bad news: how to help patients who suffer. Wes J Med. 1999;171:260-263. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1305864

27. Pfeifer M, Head B. Which critical communication skills are essential for interdisciplinary end-of-life discussions? AMA J Ethics. 2018;8:E724-E731. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2018.724

28. Song M-K, Ward SE, Hepburn K, et al. SPIRIT advance care planning intervention in early stage dementias: an NIH stage I behavioral intervention development trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;71:55-62. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.06.005

29. Song M-K, Ward SE, Hepburn K, et al. Can persons with dementia meaningfully participate in advance care planning discussions? A mixed-methods study of SPIRIT. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:1410-1416. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0088

30. Two-phased study of SPIRIT in mild dementia. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03311711. Updated August 23, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03311711

31. Dassel K, Utz R, Supiano K, et al. Development of a dementia-focused end-of-life planning tool: the LEAD Guide (Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia). Innov Aging. 2019;3:igz024. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz024

32. Dassel K, Supiano K, Utz R, et al. The LEAD Guide. Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2019. Accessed December 20, 2021. utahgwep.org/resources/search-all-resources/send/10-dementia/27-the-lead-guide#:~:text=The%20LEAD%20Guide%20(Life%2DPlanning,your%20decisions%20about%20your%20care

As the geriatric population continues to grow and treatment advances blur the lines between improving the length of life vs improving its quality, end-of-life (EOL) conversations are becoming increasingly important. These discussions are a crucial part of the advance care planning (ACP) process, in which patients discuss their treatment preferences and values with their caregiver/surrogate decision maker and health care provider to ultimately improve EOL decision-making and care. 1,2

EOL conversations are most helpful when incorporated in the outpatient setting as part of the patient’s ongoing health care plan or when initiating treatment for a chronic or life-threatening disease. Because family physicians promote general wellness, understand the patient’s health status and medical history, and have an ongoing—and often longstanding—relationship with patients and their families, we are ideally positioned to engage patients in EOL discussions. However, these conversations can be challenging in the outpatient setting, and often clinicians struggle not only to find ways to raise the subject, but also to find the time to have these supportive, meaningful conversations.3

In this article, we will address the importance of having EOL discussions in the outpatient setting, specifically about advance directives (ADs), and the reasons why patients and physicians might avoid these discussions. The role of palliative care in EOL care, along with its benefits and methods for overcoming patient and physician barriers to its successful use, are reviewed. Finally, we examine specific challenges associated with discussing EOL care with patients with decreased mental capacity, such as those with dementia, and provide strategies to successfully facilitate EOL discussions in these populations.

Moving patients toward completion of advance directives

Although many older patients express a desire to document their wishes before EOL situations arise, they may not fully understand the benefits of an AD or how to complete one. 4 Often the family physician is best equipped to address the patient’s concerns and discuss their goals for EOL care, as well as the potential situations that might arise.

Managing an aging population. Projections suggest that primary care physicians will encounter increasing numbers of geriatric patients in the next 2 decades. Thus it is essential for those in primary care to receive proper training during their residency for the care of this group of patients. According to a group of academic educators and geriatricians from internal medicine and family medicine whose goal was to define a set of minimal and essential competencies in the care of older adults, this includes training on how to discuss and document “advance care planning and goals of care with all patients with chronic or complex illness,” as well as how to differentiate among “types of code status, health care proxies, and advanced directives” within the state in which training occurs. 5

Educate patients and ease fears. Patients often avoid EOL conversations or wait for their family physician to start the conversation. They may not understand how ADs can help guide care or they may believe they are “too healthy” to have these conversations at this time. 4 Simply asking about existing ADs or providing forms to patients during an outpatient visit can open the door to more in-depth discussions. Some examples of opening phrases include:

- Do you have a living will or durable power of attorney for health care?

- Have you ever discussed your health care wishes with your loved ones?

- Who would you want to speak for you regarding your health care if you could not speak for yourself? Have you discussed your health care wishes with that person?

By normalizing the conversation as a routine part of comprehensive, patient-centered care, the family physician can allay patient fears, foster open and honest conversations, and encourage ongoing discussions with loved ones as situations arise.6

Continue to: When ADs are executed...

When ADs are executed, patients often fail to have meaningful conversations with their surrogates about specific treatment wishes or EOL scenarios. As a result, the surrogate may not feel prepared to serve as a proxy decision maker or may find the role extremely stressful.7 Physicians should encourage open conversations between patients and their surrogates about potential EOL scenarios when possible. When possible and appropriate, it is also important to encourage the patient to include the surrogate in future outpatient visits so that the surrogate can understand the patient’s health status and potential decisions they may need to make.

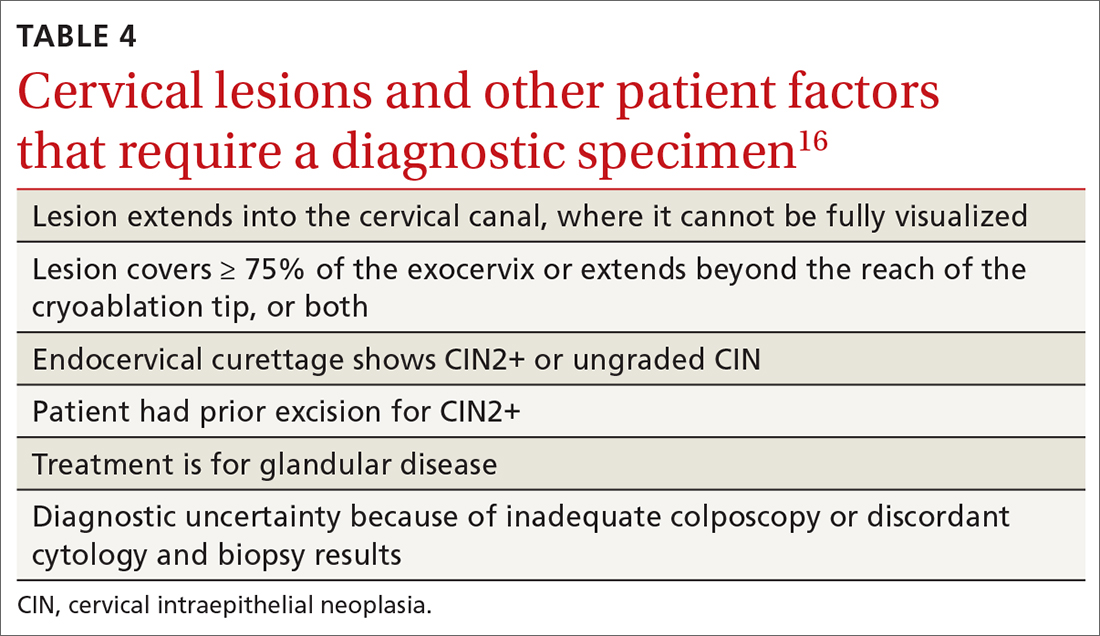

Don’t overlook clinician barriers. Family physicians also might avoid AD discussions because they do not understand laws that govern ADs, which vary from state to state. Various online resources for patients and physicians exist that clarify state-specific regulations and provide state-specific forms (TABLE).

Time constraints present another challenge for family physicians. This can be addressed by establishing workflows that include EOL elements. Also, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has provided separate billing codes for AD discussion based on time spent explaining and discussing how to complete forms.8 CPT codes 99497 and 99498 are time-based codes that cover the first 30 minutes and each additional 30 minutes, respectively, of time spent explaining and discussing how to complete standard forms in a face-to-face setting (TABLE).9 CMS also includes discussion of AD documents as an optional element of the annual Medicare wellness visit.8

Improve quality of life for patients with any serious illness

Unlike hospice, which focuses on providing comfort rather than cure in the final months of a patient’s life, palliative care strives to prevent and relieve the patient’s suffering from a serious illness that is not immediately life-threatening. Palliative care focuses on the early identification, careful assessment, and treatment of the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms associated with a patient’s condition(s).10,11 It has been well established that palliative care has a positive effect on many clinical outcomes including symptom burden, quality of life, satisfaction with care, and survival.12-14 Patients who receive palliative care consultation also tend to perceive a higher quality of care.15

Conversations lead to better outcomes. Palliative care consultation is being increasingly used in the outpatient setting and can be introduced early in a disease process. Doing so provides an additional opportunity for the family physician to introduce an EOL discussion. A comparison of outcomes between patients who had initial inpatient palliative care consultation vs outpatient palliative care referral found that outpatient referral improved quality EOL care and was associated with significantly fewer emergency department visits (68% vs 48%; P < .001) and hospital admissions (86% vs 52%; P < .001), as well as shorter hospital stays in the last 30 days of life (3-11 vs 5-14 days; P = .01).14 Despite these benefits, 60% to 90% of patients with a serious illness report never having discussed EOL care issues with their clinician.16,17

Continue to: Early EOL discussions...

Early EOL discussions have also been shown to have a positive impact on families. In a US study, family members stated that timely EOL care discussions allowed them to make use of hospice and palliative care services sooner and to make the most of their time with the patient.18

Timing and communication are key

Logistically it can be difficult to gather the right people (patient, family, etc) in the right place and at the right time. For physicians, the most often cited barriers include inadequate time to conduct an EOL discussion, 19 a perceived lack of competence in EOL conversations, 1,20 difficulty navigating patient readiness, 21 and a fear of destroying hope due to prognostic uncertainty. 19,20

A prospective, observational study used the Quality of Communication (QOC) questionnaire to assess life-sustaining treatment preferences, ACP, and the quality of EOL care communication in Dutch outpatients with clinically stable but severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 105) or congestive heart failure (n = 80). The QOC questionnaire is a validated instrument that asks patients to rate their physician on several communication skills from 0 (“the very worst” or “My doctor didn’t do this”) to 10 (“the very best”). In this study, quality communication was identified by patients as one of the most important skills for physicians to provide adequate EOL care. 22 While QOC ratings were high for general communication skills (median, 8.0 points), quality EOL care communication was rated very low (median, 0.0 points). Researchers say that this was primarily because most EOL topics were not discussed—especially spirituality, prognosis, and what dying might be like. 22 In a secondary analysis that evaluated quality of EOL care communication during 1-year follow-up of patients with advanced chronic organ failure (n = 265) with the QOC questionnaire, patient ratings improved to moderate to good (medians, 6-8 points) when these topics were addressed. 23

Pick a strategy and prepare. As the older population continues to grow, the demands of palliative care management cannot be met by specialists alone and the responsibility of discussing EOL care with patients and their families will increasingly fall to family physicians as well. 24 Several strategies and approaches have evolved to assist family physicians with acquiring the skills to conduct productive EOL discussions. These include widely referenced resources, such as VitalTalk 25 and the ABCDE Plan. 26 VitalTalk teaches skills to help clinicians navigate difficult conversations, 25 and the “ABCDE” method provides a pneumonic for recommendations for how to deliver bad news ( A dvance preparation; B uild a therapeutic environment/relationship; C ommunicate well; D eal with patient and family reactions; E ncourage and validate emotions). 26

Other strategies include familiarizing oneself with the patient’s medical history and present situation (eg, What are the patient’s symptoms? What do other involved clinicians think and recommend? What therapies have been attempted? What are the relevant social and emotional dynamics?); asking the patient who they want present for the EOL conversation; scheduling the conversation for when you can set aside an appropriate amount of time and in a private place where there will be no interruptions; and going into the meeting with your goal in mind, whether it is to deliver bad news, clarify the prognosis, establish goals of care, or communicate the patient’s goals and wishes for the EOL to those in attendance. 27 It can be very helpful to begin the conversation by clarifying what the patient and their family/surrogate understand about the current diagnosis and prognosis. From there, the family physician can present a “headline” that prepares them for the current conversation (eg, “I have your latest test results, and I need to share some serious news”). This can facilitate a more detailed discussion of the patient’s and surrogate’s goals of care. Using these strategies, family physicians can lead a productive EOL discussion that benefits everyone.

Continue to: How to navigate EOL discussions with patients with dementia

How to navigate EOL discussions with patients with dementia

EOL discussions with patients with dementia become even more complex and warrant specific discussion because one must consider the timing of such discussions, 2,28,29 the trajectory of the disease and how that affects the patient’s capacity for EOL conversations, and the critical importance of engaging caregivers/surrogate decision makers in these discussions. 2 ACP provides an opportunity for the physician, patient, and caregiver/surrogate to jointly explore the patient’s values, beliefs, and preferences for care through the EOL as the disease progresses and the patient’s decisional capacity declines.

Ensure meaningful participation with timing. EOL discussions should occur while the patient has the cognitive capacity to actively participate in the planning process. A National Institutes of Health stage I behavioral intervention development trial evaluated a structured psychoeducational intervention, known as SPIRIT (Sharing Patient’s Illness Representation to Increase Trust), that aimed to promote cognitive and emotional preparation for EOL decisions for patients and their surrogates.28 It was found to be effective in patients, including those with end-stage renal disease and advanced heart failure, and their surrogates.28 Preliminary results from the trial confirmed that people with mild-to-moderate dementia (recent Montreal Cognitive Assessment score ≥ 13) are able to participate meaningfully in EOL discussions and ACP.28

Song et al29 adapted SPIRIT for use with patients with dementia and conducted a feasibility study with 23 patient-surrogate dyads.The mixed-methods study involved an expert panel review of the adapted SPIRIT, followed by a randomized trial with qualitative interviews. All 23 patients with dementia, including 14 with moderate dementia, were able to articulate their values and EOL preferences somewhat or very coherently (91.3% inter-rater reliability).29 In addition, dyad care goal congruence (agreement between patient’s EOL preferences and surrogate’s understanding of those preferences) and surrogate decision-making confidence (comfort in performing as a surrogate) were high and patient decisional conflict (patient difficulty in weighing the benefits and burdens of life-sustaining treatments and decision-making) was low, both at baseline as well as post intervention.29 Although preparedness for EOL decision-making outcome measures did not change, people with dementia and their surrogates perceived SPIRIT to be beneficial, particularly in helping them be on the same page.29

The randomized trial portion of the study (phase 2) continues to recruit 120 patient-surrogate dyads. Patient and surrogate self-reported preparedness for EOL decision-making are the primary outcomes, measured at baseline and 2 to 3 days post intervention. The estimated study completion date is May 31, 2022.30

Evidence-based clinical guidance can improve the process. Following the Belgian Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s procedures as a sample methodology, Piers et al2 developed evidence-based clinical recommendations for providers to use in the practical application of ACP in their care of patients with dementia.The researchers searched the literature; developed recommendations based on the evidence obtained, as well as their collective expert opinion; and performed validation using expert and end-user feedback and peer review. The study resulted in 32 recommendations focused on 8 domains that ranged from the beginning of the process (preconditions for optimal implementation of ACP) to later stages (ACP when it is difficult/no longer possible to communicate).2Specific guidance for ACP in dementia care include the following:

- ACP initiation. Begin conversations around the time of diagnosis, continue them throughout ongoing care, and revisit them when changes occur in the patient’s health, financial, or residential status.

- ACP conversations. Use conversations to identify significant others in the patient’s life (potential caregivers and/or surrogate decision makers) and explore the patient’s awareness of the disease and its trajectory. Discuss the patient’s values and beliefs, as well as their fears about, and preferences for, future care and the EOL.

- Role of significant others in the ACP process. Involve a patient’s significant others early in the ACP process, educate them about the surrogate decision-maker role, assess their disease awareness, and inform them about the disease trajectory and anticipated EOL decisions. 2

Continue to: Incorporate and document patients' values and preferences with LEAD

Incorporate and document patients’ values and preferences with LEAD. Dassel et al31 developed the Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia (LEAD) tool, which is a validated dementia-focused EOL planning tool that can be used to promote discussion and document a patient’s care preferences and values within the context of their changing cognitive ability.Dassel et al31 used a 4-phase mixed-method design that included (1) focus groups of patients with early-stage dementia and family caregivers, (2) clinical utility evaluation by content experts, (3) instrument completion sampling to evaluate its psychometric properties, and (4) additional focus groups to inform how the instrument should be used by families and in clinical practice.Six scales with high internal consistency and high test-retest reliability were identified: 3 scales represented patient values (concern about being a burden, the importance of quality [vs length] of life, and the preference for autonomy in decision-making) and 3 scales represented patient preferences (use of life-prolonging measures, controlling the timing of death, and the location of EOL care).31

The LEAD Guide can be used as a self-assessment tool that is completed individually and then shared with the surrogate decision maker and health care provider.32 It also can be used to guide conversations with the surrogate and physician, as well as with trusted family and friends. Using this framework, family physicians can facilitate EOL planning with the patient and their surrogate that is based on the patient’s values and preferences for EOL care prior to, and in anticipation of, the patient’s loss of decisional capacity.31

Facilitate discussions that improve outcomes

Conversations about EOL care are taking on increased importance as the population ages and treatments advance. Understanding the concerns of patients and their surrogate decision makers, as well as the resources available to guide these difficult discussions ( TABLE ), will help family physicians conduct effective conversations that enhance care, reduce the burden on surrogate decision makers, and have a positive impact on many clinical outcomes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shirley Bodi, MD, 3000 Arlington Avenue, Department of Family Medicine, Dowling Hall, Suite 2200, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 43614; Shirley.Bodi2@utoledo.edu

As the geriatric population continues to grow and treatment advances blur the lines between improving the length of life vs improving its quality, end-of-life (EOL) conversations are becoming increasingly important. These discussions are a crucial part of the advance care planning (ACP) process, in which patients discuss their treatment preferences and values with their caregiver/surrogate decision maker and health care provider to ultimately improve EOL decision-making and care. 1,2

EOL conversations are most helpful when incorporated in the outpatient setting as part of the patient’s ongoing health care plan or when initiating treatment for a chronic or life-threatening disease. Because family physicians promote general wellness, understand the patient’s health status and medical history, and have an ongoing—and often longstanding—relationship with patients and their families, we are ideally positioned to engage patients in EOL discussions. However, these conversations can be challenging in the outpatient setting, and often clinicians struggle not only to find ways to raise the subject, but also to find the time to have these supportive, meaningful conversations.3

In this article, we will address the importance of having EOL discussions in the outpatient setting, specifically about advance directives (ADs), and the reasons why patients and physicians might avoid these discussions. The role of palliative care in EOL care, along with its benefits and methods for overcoming patient and physician barriers to its successful use, are reviewed. Finally, we examine specific challenges associated with discussing EOL care with patients with decreased mental capacity, such as those with dementia, and provide strategies to successfully facilitate EOL discussions in these populations.

Moving patients toward completion of advance directives

Although many older patients express a desire to document their wishes before EOL situations arise, they may not fully understand the benefits of an AD or how to complete one. 4 Often the family physician is best equipped to address the patient’s concerns and discuss their goals for EOL care, as well as the potential situations that might arise.

Managing an aging population. Projections suggest that primary care physicians will encounter increasing numbers of geriatric patients in the next 2 decades. Thus it is essential for those in primary care to receive proper training during their residency for the care of this group of patients. According to a group of academic educators and geriatricians from internal medicine and family medicine whose goal was to define a set of minimal and essential competencies in the care of older adults, this includes training on how to discuss and document “advance care planning and goals of care with all patients with chronic or complex illness,” as well as how to differentiate among “types of code status, health care proxies, and advanced directives” within the state in which training occurs. 5

Educate patients and ease fears. Patients often avoid EOL conversations or wait for their family physician to start the conversation. They may not understand how ADs can help guide care or they may believe they are “too healthy” to have these conversations at this time. 4 Simply asking about existing ADs or providing forms to patients during an outpatient visit can open the door to more in-depth discussions. Some examples of opening phrases include:

- Do you have a living will or durable power of attorney for health care?

- Have you ever discussed your health care wishes with your loved ones?

- Who would you want to speak for you regarding your health care if you could not speak for yourself? Have you discussed your health care wishes with that person?

By normalizing the conversation as a routine part of comprehensive, patient-centered care, the family physician can allay patient fears, foster open and honest conversations, and encourage ongoing discussions with loved ones as situations arise.6

Continue to: When ADs are executed...

When ADs are executed, patients often fail to have meaningful conversations with their surrogates about specific treatment wishes or EOL scenarios. As a result, the surrogate may not feel prepared to serve as a proxy decision maker or may find the role extremely stressful.7 Physicians should encourage open conversations between patients and their surrogates about potential EOL scenarios when possible. When possible and appropriate, it is also important to encourage the patient to include the surrogate in future outpatient visits so that the surrogate can understand the patient’s health status and potential decisions they may need to make.

Don’t overlook clinician barriers. Family physicians also might avoid AD discussions because they do not understand laws that govern ADs, which vary from state to state. Various online resources for patients and physicians exist that clarify state-specific regulations and provide state-specific forms (TABLE).

Time constraints present another challenge for family physicians. This can be addressed by establishing workflows that include EOL elements. Also, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has provided separate billing codes for AD discussion based on time spent explaining and discussing how to complete forms.8 CPT codes 99497 and 99498 are time-based codes that cover the first 30 minutes and each additional 30 minutes, respectively, of time spent explaining and discussing how to complete standard forms in a face-to-face setting (TABLE).9 CMS also includes discussion of AD documents as an optional element of the annual Medicare wellness visit.8

Improve quality of life for patients with any serious illness

Unlike hospice, which focuses on providing comfort rather than cure in the final months of a patient’s life, palliative care strives to prevent and relieve the patient’s suffering from a serious illness that is not immediately life-threatening. Palliative care focuses on the early identification, careful assessment, and treatment of the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms associated with a patient’s condition(s).10,11 It has been well established that palliative care has a positive effect on many clinical outcomes including symptom burden, quality of life, satisfaction with care, and survival.12-14 Patients who receive palliative care consultation also tend to perceive a higher quality of care.15

Conversations lead to better outcomes. Palliative care consultation is being increasingly used in the outpatient setting and can be introduced early in a disease process. Doing so provides an additional opportunity for the family physician to introduce an EOL discussion. A comparison of outcomes between patients who had initial inpatient palliative care consultation vs outpatient palliative care referral found that outpatient referral improved quality EOL care and was associated with significantly fewer emergency department visits (68% vs 48%; P < .001) and hospital admissions (86% vs 52%; P < .001), as well as shorter hospital stays in the last 30 days of life (3-11 vs 5-14 days; P = .01).14 Despite these benefits, 60% to 90% of patients with a serious illness report never having discussed EOL care issues with their clinician.16,17

Continue to: Early EOL discussions...

Early EOL discussions have also been shown to have a positive impact on families. In a US study, family members stated that timely EOL care discussions allowed them to make use of hospice and palliative care services sooner and to make the most of their time with the patient.18

Timing and communication are key

Logistically it can be difficult to gather the right people (patient, family, etc) in the right place and at the right time. For physicians, the most often cited barriers include inadequate time to conduct an EOL discussion, 19 a perceived lack of competence in EOL conversations, 1,20 difficulty navigating patient readiness, 21 and a fear of destroying hope due to prognostic uncertainty. 19,20

A prospective, observational study used the Quality of Communication (QOC) questionnaire to assess life-sustaining treatment preferences, ACP, and the quality of EOL care communication in Dutch outpatients with clinically stable but severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 105) or congestive heart failure (n = 80). The QOC questionnaire is a validated instrument that asks patients to rate their physician on several communication skills from 0 (“the very worst” or “My doctor didn’t do this”) to 10 (“the very best”). In this study, quality communication was identified by patients as one of the most important skills for physicians to provide adequate EOL care. 22 While QOC ratings were high for general communication skills (median, 8.0 points), quality EOL care communication was rated very low (median, 0.0 points). Researchers say that this was primarily because most EOL topics were not discussed—especially spirituality, prognosis, and what dying might be like. 22 In a secondary analysis that evaluated quality of EOL care communication during 1-year follow-up of patients with advanced chronic organ failure (n = 265) with the QOC questionnaire, patient ratings improved to moderate to good (medians, 6-8 points) when these topics were addressed. 23

Pick a strategy and prepare. As the older population continues to grow, the demands of palliative care management cannot be met by specialists alone and the responsibility of discussing EOL care with patients and their families will increasingly fall to family physicians as well. 24 Several strategies and approaches have evolved to assist family physicians with acquiring the skills to conduct productive EOL discussions. These include widely referenced resources, such as VitalTalk 25 and the ABCDE Plan. 26 VitalTalk teaches skills to help clinicians navigate difficult conversations, 25 and the “ABCDE” method provides a pneumonic for recommendations for how to deliver bad news ( A dvance preparation; B uild a therapeutic environment/relationship; C ommunicate well; D eal with patient and family reactions; E ncourage and validate emotions). 26

Other strategies include familiarizing oneself with the patient’s medical history and present situation (eg, What are the patient’s symptoms? What do other involved clinicians think and recommend? What therapies have been attempted? What are the relevant social and emotional dynamics?); asking the patient who they want present for the EOL conversation; scheduling the conversation for when you can set aside an appropriate amount of time and in a private place where there will be no interruptions; and going into the meeting with your goal in mind, whether it is to deliver bad news, clarify the prognosis, establish goals of care, or communicate the patient’s goals and wishes for the EOL to those in attendance. 27 It can be very helpful to begin the conversation by clarifying what the patient and their family/surrogate understand about the current diagnosis and prognosis. From there, the family physician can present a “headline” that prepares them for the current conversation (eg, “I have your latest test results, and I need to share some serious news”). This can facilitate a more detailed discussion of the patient’s and surrogate’s goals of care. Using these strategies, family physicians can lead a productive EOL discussion that benefits everyone.

Continue to: How to navigate EOL discussions with patients with dementia

How to navigate EOL discussions with patients with dementia

EOL discussions with patients with dementia become even more complex and warrant specific discussion because one must consider the timing of such discussions, 2,28,29 the trajectory of the disease and how that affects the patient’s capacity for EOL conversations, and the critical importance of engaging caregivers/surrogate decision makers in these discussions. 2 ACP provides an opportunity for the physician, patient, and caregiver/surrogate to jointly explore the patient’s values, beliefs, and preferences for care through the EOL as the disease progresses and the patient’s decisional capacity declines.

Ensure meaningful participation with timing. EOL discussions should occur while the patient has the cognitive capacity to actively participate in the planning process. A National Institutes of Health stage I behavioral intervention development trial evaluated a structured psychoeducational intervention, known as SPIRIT (Sharing Patient’s Illness Representation to Increase Trust), that aimed to promote cognitive and emotional preparation for EOL decisions for patients and their surrogates.28 It was found to be effective in patients, including those with end-stage renal disease and advanced heart failure, and their surrogates.28 Preliminary results from the trial confirmed that people with mild-to-moderate dementia (recent Montreal Cognitive Assessment score ≥ 13) are able to participate meaningfully in EOL discussions and ACP.28

Song et al29 adapted SPIRIT for use with patients with dementia and conducted a feasibility study with 23 patient-surrogate dyads.The mixed-methods study involved an expert panel review of the adapted SPIRIT, followed by a randomized trial with qualitative interviews. All 23 patients with dementia, including 14 with moderate dementia, were able to articulate their values and EOL preferences somewhat or very coherently (91.3% inter-rater reliability).29 In addition, dyad care goal congruence (agreement between patient’s EOL preferences and surrogate’s understanding of those preferences) and surrogate decision-making confidence (comfort in performing as a surrogate) were high and patient decisional conflict (patient difficulty in weighing the benefits and burdens of life-sustaining treatments and decision-making) was low, both at baseline as well as post intervention.29 Although preparedness for EOL decision-making outcome measures did not change, people with dementia and their surrogates perceived SPIRIT to be beneficial, particularly in helping them be on the same page.29

The randomized trial portion of the study (phase 2) continues to recruit 120 patient-surrogate dyads. Patient and surrogate self-reported preparedness for EOL decision-making are the primary outcomes, measured at baseline and 2 to 3 days post intervention. The estimated study completion date is May 31, 2022.30

Evidence-based clinical guidance can improve the process. Following the Belgian Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine’s procedures as a sample methodology, Piers et al2 developed evidence-based clinical recommendations for providers to use in the practical application of ACP in their care of patients with dementia.The researchers searched the literature; developed recommendations based on the evidence obtained, as well as their collective expert opinion; and performed validation using expert and end-user feedback and peer review. The study resulted in 32 recommendations focused on 8 domains that ranged from the beginning of the process (preconditions for optimal implementation of ACP) to later stages (ACP when it is difficult/no longer possible to communicate).2Specific guidance for ACP in dementia care include the following:

- ACP initiation. Begin conversations around the time of diagnosis, continue them throughout ongoing care, and revisit them when changes occur in the patient’s health, financial, or residential status.

- ACP conversations. Use conversations to identify significant others in the patient’s life (potential caregivers and/or surrogate decision makers) and explore the patient’s awareness of the disease and its trajectory. Discuss the patient’s values and beliefs, as well as their fears about, and preferences for, future care and the EOL.

- Role of significant others in the ACP process. Involve a patient’s significant others early in the ACP process, educate them about the surrogate decision-maker role, assess their disease awareness, and inform them about the disease trajectory and anticipated EOL decisions. 2

Continue to: Incorporate and document patients' values and preferences with LEAD

Incorporate and document patients’ values and preferences with LEAD. Dassel et al31 developed the Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia (LEAD) tool, which is a validated dementia-focused EOL planning tool that can be used to promote discussion and document a patient’s care preferences and values within the context of their changing cognitive ability.Dassel et al31 used a 4-phase mixed-method design that included (1) focus groups of patients with early-stage dementia and family caregivers, (2) clinical utility evaluation by content experts, (3) instrument completion sampling to evaluate its psychometric properties, and (4) additional focus groups to inform how the instrument should be used by families and in clinical practice.Six scales with high internal consistency and high test-retest reliability were identified: 3 scales represented patient values (concern about being a burden, the importance of quality [vs length] of life, and the preference for autonomy in decision-making) and 3 scales represented patient preferences (use of life-prolonging measures, controlling the timing of death, and the location of EOL care).31

The LEAD Guide can be used as a self-assessment tool that is completed individually and then shared with the surrogate decision maker and health care provider.32 It also can be used to guide conversations with the surrogate and physician, as well as with trusted family and friends. Using this framework, family physicians can facilitate EOL planning with the patient and their surrogate that is based on the patient’s values and preferences for EOL care prior to, and in anticipation of, the patient’s loss of decisional capacity.31

Facilitate discussions that improve outcomes

Conversations about EOL care are taking on increased importance as the population ages and treatments advance. Understanding the concerns of patients and their surrogate decision makers, as well as the resources available to guide these difficult discussions ( TABLE ), will help family physicians conduct effective conversations that enhance care, reduce the burden on surrogate decision makers, and have a positive impact on many clinical outcomes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shirley Bodi, MD, 3000 Arlington Avenue, Department of Family Medicine, Dowling Hall, Suite 2200, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 43614; Shirley.Bodi2@utoledo.edu

1. Bergenholtz Heidi, Timm HU, Missel M. Talking about end of life in general palliative care – what’s going on? A qualitative study on end-of-life conversations in an acute care hospital in Denmark. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18:62. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0448-z

2. Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, et al. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:88. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0332-2

3. Tunzi M, Ventres W. A reflective case study in family medicine advance care planning conversations. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:108-114. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.180198

4. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:31-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02093.x

5. Williams BC, Warshaw G, Fabiny AR, et al. Medicine in the 21st century: recommended essential geriatrics competencies for internal medicine and family medicine residents. J Grad Med Ed. 2010;2:373-383. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00065.1

6. Alano G, Pekmezaris R, Tai J, et al. Factors influencing older adults to complete advance directives. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:267-275. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000064

7. Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:336-346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008

8. Edelberg C. Advance care planning with and without an annual wellness visit. Ed Management website. June 1, 2016. Accessed November 16, 2021. ww.reliasmedia.com/articles/137829-advanced-care-planning-with-and-without-an-annual-wellness-visit

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Frequently asked questions about billing the physician fee schedule for advance care planning services. July 14, 2016. Accessed December 20, 2021. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/FAQ-Advance-Care-Planning.pdf

10. World Health Organization. Palliative care fact sheet. August 5, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

11. National Institute on Aging. What are palliative care and hospice care? Reviewed May 14, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care#palliative-vs-hospice

12. Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat, SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83-91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83

13. Muir JC, Daley F, Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:126-135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.017

14. Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743-1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628

15. Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, e al. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142:128-133. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2222

16. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:195-204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809

17. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patients mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665

18. Park E, Check DK, Yopp JM, et al. An exploratory study of end-of-life prognostic communication needs as reported by widowed fathers due to cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1471-1476. doi: 10.1002/pon.3757

19. Tavares N, Jarrett N, Hunt K, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care conversations in COPD: a systematic literature review. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3:00068-2016. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00068-2016

20. Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:507-517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823

21. Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035

22. Janssen DJA, Spruit MA, Schols JMGA, et al. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest. 2011;139:1081-1088. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1753

23. Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. Patient-clinician communication about end-of-life care on patients with advanced chronic organ failure during one year. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1109-1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.008

24. Brighton LJ, Bristowe K. Communication in palliative care: talking about the end of life, before the end of life. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:466-470. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133368

25. VitalTalk website. Accessed December 20, 2021. vitaltalk.org

26. Rabow MQ, McPhee SJ. Beyond breaking bad news: how to help patients who suffer. Wes J Med. 1999;171:260-263. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1305864

27. Pfeifer M, Head B. Which critical communication skills are essential for interdisciplinary end-of-life discussions? AMA J Ethics. 2018;8:E724-E731. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2018.724

28. Song M-K, Ward SE, Hepburn K, et al. SPIRIT advance care planning intervention in early stage dementias: an NIH stage I behavioral intervention development trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;71:55-62. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.06.005

29. Song M-K, Ward SE, Hepburn K, et al. Can persons with dementia meaningfully participate in advance care planning discussions? A mixed-methods study of SPIRIT. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:1410-1416. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0088

30. Two-phased study of SPIRIT in mild dementia. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03311711. Updated August 23, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03311711

31. Dassel K, Utz R, Supiano K, et al. Development of a dementia-focused end-of-life planning tool: the LEAD Guide (Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia). Innov Aging. 2019;3:igz024. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz024

32. Dassel K, Supiano K, Utz R, et al. The LEAD Guide. Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2019. Accessed December 20, 2021. utahgwep.org/resources/search-all-resources/send/10-dementia/27-the-lead-guide#:~:text=The%20LEAD%20Guide%20(Life%2DPlanning,your%20decisions%20about%20your%20care

1. Bergenholtz Heidi, Timm HU, Missel M. Talking about end of life in general palliative care – what’s going on? A qualitative study on end-of-life conversations in an acute care hospital in Denmark. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18:62. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0448-z

2. Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, et al. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:88. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0332-2

3. Tunzi M, Ventres W. A reflective case study in family medicine advance care planning conversations. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:108-114. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.01.180198

4. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:31-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02093.x

5. Williams BC, Warshaw G, Fabiny AR, et al. Medicine in the 21st century: recommended essential geriatrics competencies for internal medicine and family medicine residents. J Grad Med Ed. 2010;2:373-383. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00065.1

6. Alano G, Pekmezaris R, Tai J, et al. Factors influencing older adults to complete advance directives. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:267-275. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000064

7. Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:336-346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008

8. Edelberg C. Advance care planning with and without an annual wellness visit. Ed Management website. June 1, 2016. Accessed November 16, 2021. ww.reliasmedia.com/articles/137829-advanced-care-planning-with-and-without-an-annual-wellness-visit

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Frequently asked questions about billing the physician fee schedule for advance care planning services. July 14, 2016. Accessed December 20, 2021. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/FAQ-Advance-Care-Planning.pdf

10. World Health Organization. Palliative care fact sheet. August 5, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

11. National Institute on Aging. What are palliative care and hospice care? Reviewed May 14, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care#palliative-vs-hospice

12. Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat, SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83-91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83

13. Muir JC, Daley F, Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:126-135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.017

14. Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743-1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628

15. Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, e al. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142:128-133. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2222

16. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:195-204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809

17. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patients mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665

18. Park E, Check DK, Yopp JM, et al. An exploratory study of end-of-life prognostic communication needs as reported by widowed fathers due to cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1471-1476. doi: 10.1002/pon.3757

19. Tavares N, Jarrett N, Hunt K, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care conversations in COPD: a systematic literature review. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3:00068-2016. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00068-2016

20. Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:507-517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823

21. Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035

22. Janssen DJA, Spruit MA, Schols JMGA, et al. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest. 2011;139:1081-1088. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1753

23. Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. Patient-clinician communication about end-of-life care on patients with advanced chronic organ failure during one year. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1109-1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.008

24. Brighton LJ, Bristowe K. Communication in palliative care: talking about the end of life, before the end of life. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:466-470. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133368

25. VitalTalk website. Accessed December 20, 2021. vitaltalk.org

26. Rabow MQ, McPhee SJ. Beyond breaking bad news: how to help patients who suffer. Wes J Med. 1999;171:260-263. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1305864

27. Pfeifer M, Head B. Which critical communication skills are essential for interdisciplinary end-of-life discussions? AMA J Ethics. 2018;8:E724-E731. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2018.724

28. Song M-K, Ward SE, Hepburn K, et al. SPIRIT advance care planning intervention in early stage dementias: an NIH stage I behavioral intervention development trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;71:55-62. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.06.005

29. Song M-K, Ward SE, Hepburn K, et al. Can persons with dementia meaningfully participate in advance care planning discussions? A mixed-methods study of SPIRIT. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:1410-1416. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0088

30. Two-phased study of SPIRIT in mild dementia. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03311711. Updated August 23, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03311711

31. Dassel K, Utz R, Supiano K, et al. Development of a dementia-focused end-of-life planning tool: the LEAD Guide (Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia). Innov Aging. 2019;3:igz024. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz024

32. Dassel K, Supiano K, Utz R, et al. The LEAD Guide. Life-planning in Early Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2019. Accessed December 20, 2021. utahgwep.org/resources/search-all-resources/send/10-dementia/27-the-lead-guide#:~:text=The%20LEAD%20Guide%20(Life%2DPlanning,your%20decisions%20about%20your%20care

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Improve patients’ quality of life and satisfaction with care through the successful implementation of palliative care. C

› Initiate end-of-life (EOL) discussions with patients with dementia at diagnosis, while the patient is cognizant and able to actively express their values and preferences for EOL care. C

› Engage surrogate decision makers in conversations about dementia, its trajectory, and their role in EOL care early in the process. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Cervical cancer update: The latest on screening & management

The World Health Organization estimates that, in 2020, worldwide, there were 604,000 new cases of uterine cervical cancer and approximately 342,000 deaths, 84% of which occurred in developing countries.1 In the United States, as of 2018, the lifetime risk of death from cervical cancer was 2.2 for every 100,000

In this article, we summarize recent updates in the epidemiology, prevention, and treatment of cervical cancer. We emphasize recent information of value to family physicians, including updates in clinical guidelines and other pertinent national recommendations.

Spotlight continues to shine on HPV

It has been known for several decades that cervical cancer is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). Of more than 100 known HPV types, 14 or 15 are classified as carcinogenic. HPV 16 is the most common oncogenic type, causing more than 60% of cases of cervical cancer3,4

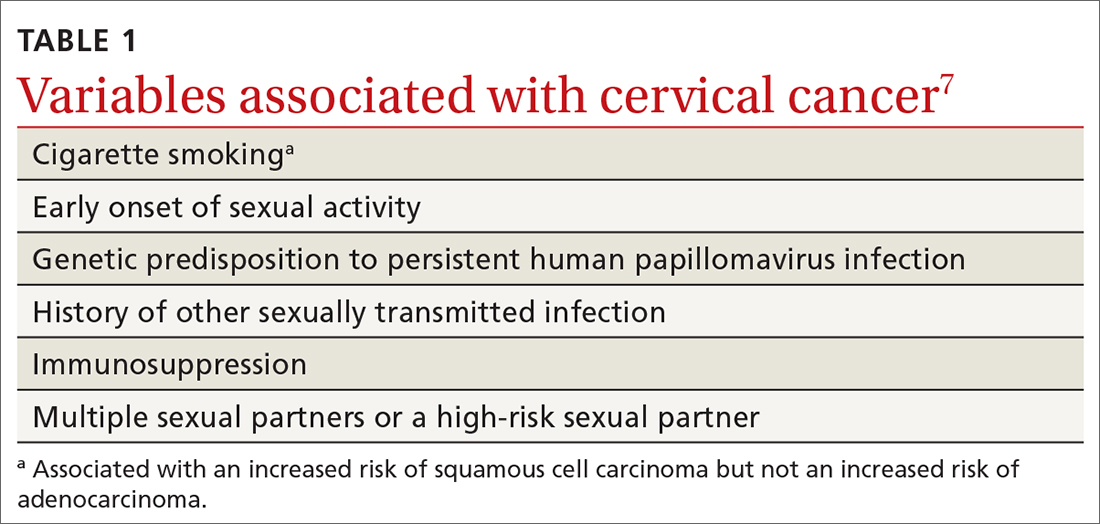

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection, with as many as 80% of sexually active people becoming infected during their lifetime, generally before 50 years of age.5 HPV also causes other anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers; however, worldwide, more than 80% of HPV-associated cancers are cervical.6 Risk factors for cervical cancer are listed in TABLE 1.7 Cervical cancer is less common when partners are circumcised.7

Most cases of HPV infection clear in 1 or 2 years

At least 70% of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); 20% to 25% are adenocarcinoma (ADC); and < 3% to 5% are adenosquamous carcinoma.10 Almost 100% of cervical SCCs are HPV+, as are 86% of cervical ADCs. The most common reason for HPV-negative status in patients with cervical cancer is false-negative testing because of inadequate methods.

Primary prevention through vaccination