User login

Treatment of Melasma Using Tranexamic Acid: What’s Known and What’s Next

Tranexamic acid is a synthetic lysine derivative that inhibits plasminogen activation by blocking lysine-binding sites on the plasminogen molecule. Although the US Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for tranexamic acid include treatment of patients with menorrhagia and reduction or prevention of hemorrhage in patients with hemophilia undergoing tooth extraction, the potential efficacy of tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma has been consistently reported since the 1980s.1

Tranexamic acid exerts effects on pigmentation via its inhibitory effects on UV light–induced plasminogen activator and plasmin activity.2 UV radiation induces the synthesis of plasminogen activator by keratinocytes, which results in increased conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Plasminogen activator induces tyrosinase activity, resulting in increased melanin synthesis. The presence of plasmin results in increased production of both arachidonic acid and fibroblast growth factor, which stimulate melanogenesis and neovascularization, respectively.3 By inhibiting plasminogen activation, tranexamic acid mitigates UV radiation–induced melanogenesis and neovascularization. In treated guinea pig skin, application of topical tranexamic acid following UV radiation exposure inhibited the development of expected skin hyperpigmentation and also reduced tyrosinase activity.4,5

The largest study on the use of oral tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma was a retrospective chart review of 561 melasma patients treated with tranexamic acid at a single center in Singapore.6 More than 90% of patients received prior treatment of their melasma, including bleaching creams and energy-based treatment. Among patients who received oral tranexamic acid over a 4-month period, 90% of patients demonstrated improvement in their melasma severity. Side effects were experienced by 7% of patients; the most common side effects were abdominal bloating and pain (experienced by 2% of patients). Notably, 1 patient developed deep vein thrombosis during treatment and subsequently was found to have protein S deficiency.6

Although the daily doses of tranexamic acid for the treatment of menorrhagia and perioperative hemophilia patients are 3900 mg and 30 to 40 mg/kg, respectively, effective daily doses reported for the treatment of melasma have ranged from the initial report of efficacy at 750 to 1500 mg to subsequent reports of improvement at daily doses of 500 mg.1,2,6-8

Challenges to the use of tranexamic acid for melasma treatment in the United States include the medicolegal environment, specifically the risks associated with using a systemic procoagulant medication for a cosmetic indication. Patients should be screened and counseled on the risks of developing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism prior to initiating treatment. Cost and accessibility also may limit the use of tranexamic acid in the United States. Tranexamic acid is available for off-label use in the United States with a prescription in the form of 650-mg tablets that can be split by patients to approximate twice-daily 325 mg dosing. This cosmetic indication poses an out-of-pocket cost to patients of over $110 per month or as low as $48 per month with a coupon at the time of publication.9

Given the potential for serious adverse effects with the use of systemic tranexamic acid, there has been interest in formulating and evaluating topical tranexamic acid for cosmetic indications.10-13 Topical tranexamic acid has been used alone and in conjunction with modalities to increase uptake, including intradermal injection, microneedling, and fractionated CO2 laser.12-14 Although these reports show initial promise, the currently available data are limited by small sample sizes, short treatment durations, lack of dose comparisons, and lack of short-term or long-term follow-up data. In addition to addressing these knowledge gaps in our understanding of topical tranexamic acid as a treatment option for melasma, further studies on the minimum systemic dose may address the downside of cost and potential for complications that may limit use of this medication in the United States.

The potential uses for tranexamic acid extend to the treatment of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and rosacea. Melanocytes cultured in media conditioned by fractionated CO2 laser–treated keratinocytes were found to have decreased tyrosinase activity and reduced melanin content when treated with tranexamic acid, suggesting the potential role for tranexamic acid to be used postprocedurally to reduce the risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in prone skin types.15 Oral and topical tranexamic acid also have been reported to improve the appearance of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, potentially relating to the inhibitory effects of tranexamic acid on neovascularization.3,16,17 Although larger-scale controlled studies are required for further investigation of tranexamic acid for these indications, it has shown early promise as an adjunctive treatment for several dermatologic disorders, including melasma, and warrants further characterization as a potential therapeutic option.

- Higashi N. Treatment of melasma with oral tranexamic acid. Skin Res. 1988;30:676-680.

- Tse TW, Hui E. Tranexamic acid: an important adjuvant in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:57-66.

- Sundbeck A, Karlsson L, Lilja J, et al. Inhibition of tumour vascularization by tranexamic acid. experimental studies on possible mechanisms. Anticancer Res. 1981;1:299-304.

- Maeda K, Naganuma M. Topical trans-4-aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid prevents ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;47:136-141.

- Li D, Shi Y, Li M, et al. Tranexamic acid can treat ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation in guinea pigs. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:289-292.

- Lee HC, Thng TG, Goh CL. Oral tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma: a retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:385-392.

- Kim HJ, Moon SH, Cho SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in melasma: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:776-781.

- Perper M, Eber AE, Fayne R, et al. Tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:373-381.

- Tranexamic acid. GoodRx website. https://www.goodrx.com/tranexamic-acid. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Kim SJ, Park JY, Shibata T, et al. Efficacy and possible mechanisms of topical tranexamic acid in melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:480-485.

- Ebrahimi B, Naeini FF. Topical tranexamic acid as a promising treatment for melasma. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:753-757.

- Xu Y, Ma R, Juliandri J, et al. Efficacy of functional microarray of microneedles combined with topical tranexamic acid for melasma: a randomized, self-controlled, split-face study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(19):e6897.

- Hsiao CY, Sung HC, Hu S, et al. Fractional CO2 laser treatment to enhance skin permeation of tranexamic acid with minimal skin disruption. Dermatology (Basel). 2015;230:269-275.

- Saki N, Darayesh M, Heiran A. Comparing the efficacy of topical hydroquinone 2% versus intradermal tranexamic acid microinjections in treating melasma: a split-face controlled trial [published online November 9, 2017]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2017.1392476.

- Kim MS, Bang SH, Kim JH, et al. Tranexamic acid diminishes laser-induced melanogenesis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:250-256.

- Kim MS, Chang SE, Haw S, et al. Tranexamic acid solution soaking is an excellent approach for rosacea patients: a preliminary observation in six patients. J Dermatol. 2013;40:70-71.

- Kwon HJ, Suh JH, Ko EJ, et al. Combination treatment of propranolol, minocycline, and tranexamic acid for effective control of rosacea [published online November 26, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12439.

Tranexamic acid is a synthetic lysine derivative that inhibits plasminogen activation by blocking lysine-binding sites on the plasminogen molecule. Although the US Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for tranexamic acid include treatment of patients with menorrhagia and reduction or prevention of hemorrhage in patients with hemophilia undergoing tooth extraction, the potential efficacy of tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma has been consistently reported since the 1980s.1

Tranexamic acid exerts effects on pigmentation via its inhibitory effects on UV light–induced plasminogen activator and plasmin activity.2 UV radiation induces the synthesis of plasminogen activator by keratinocytes, which results in increased conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Plasminogen activator induces tyrosinase activity, resulting in increased melanin synthesis. The presence of plasmin results in increased production of both arachidonic acid and fibroblast growth factor, which stimulate melanogenesis and neovascularization, respectively.3 By inhibiting plasminogen activation, tranexamic acid mitigates UV radiation–induced melanogenesis and neovascularization. In treated guinea pig skin, application of topical tranexamic acid following UV radiation exposure inhibited the development of expected skin hyperpigmentation and also reduced tyrosinase activity.4,5

The largest study on the use of oral tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma was a retrospective chart review of 561 melasma patients treated with tranexamic acid at a single center in Singapore.6 More than 90% of patients received prior treatment of their melasma, including bleaching creams and energy-based treatment. Among patients who received oral tranexamic acid over a 4-month period, 90% of patients demonstrated improvement in their melasma severity. Side effects were experienced by 7% of patients; the most common side effects were abdominal bloating and pain (experienced by 2% of patients). Notably, 1 patient developed deep vein thrombosis during treatment and subsequently was found to have protein S deficiency.6

Although the daily doses of tranexamic acid for the treatment of menorrhagia and perioperative hemophilia patients are 3900 mg and 30 to 40 mg/kg, respectively, effective daily doses reported for the treatment of melasma have ranged from the initial report of efficacy at 750 to 1500 mg to subsequent reports of improvement at daily doses of 500 mg.1,2,6-8

Challenges to the use of tranexamic acid for melasma treatment in the United States include the medicolegal environment, specifically the risks associated with using a systemic procoagulant medication for a cosmetic indication. Patients should be screened and counseled on the risks of developing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism prior to initiating treatment. Cost and accessibility also may limit the use of tranexamic acid in the United States. Tranexamic acid is available for off-label use in the United States with a prescription in the form of 650-mg tablets that can be split by patients to approximate twice-daily 325 mg dosing. This cosmetic indication poses an out-of-pocket cost to patients of over $110 per month or as low as $48 per month with a coupon at the time of publication.9

Given the potential for serious adverse effects with the use of systemic tranexamic acid, there has been interest in formulating and evaluating topical tranexamic acid for cosmetic indications.10-13 Topical tranexamic acid has been used alone and in conjunction with modalities to increase uptake, including intradermal injection, microneedling, and fractionated CO2 laser.12-14 Although these reports show initial promise, the currently available data are limited by small sample sizes, short treatment durations, lack of dose comparisons, and lack of short-term or long-term follow-up data. In addition to addressing these knowledge gaps in our understanding of topical tranexamic acid as a treatment option for melasma, further studies on the minimum systemic dose may address the downside of cost and potential for complications that may limit use of this medication in the United States.

The potential uses for tranexamic acid extend to the treatment of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and rosacea. Melanocytes cultured in media conditioned by fractionated CO2 laser–treated keratinocytes were found to have decreased tyrosinase activity and reduced melanin content when treated with tranexamic acid, suggesting the potential role for tranexamic acid to be used postprocedurally to reduce the risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in prone skin types.15 Oral and topical tranexamic acid also have been reported to improve the appearance of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, potentially relating to the inhibitory effects of tranexamic acid on neovascularization.3,16,17 Although larger-scale controlled studies are required for further investigation of tranexamic acid for these indications, it has shown early promise as an adjunctive treatment for several dermatologic disorders, including melasma, and warrants further characterization as a potential therapeutic option.

Tranexamic acid is a synthetic lysine derivative that inhibits plasminogen activation by blocking lysine-binding sites on the plasminogen molecule. Although the US Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for tranexamic acid include treatment of patients with menorrhagia and reduction or prevention of hemorrhage in patients with hemophilia undergoing tooth extraction, the potential efficacy of tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma has been consistently reported since the 1980s.1

Tranexamic acid exerts effects on pigmentation via its inhibitory effects on UV light–induced plasminogen activator and plasmin activity.2 UV radiation induces the synthesis of plasminogen activator by keratinocytes, which results in increased conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Plasminogen activator induces tyrosinase activity, resulting in increased melanin synthesis. The presence of plasmin results in increased production of both arachidonic acid and fibroblast growth factor, which stimulate melanogenesis and neovascularization, respectively.3 By inhibiting plasminogen activation, tranexamic acid mitigates UV radiation–induced melanogenesis and neovascularization. In treated guinea pig skin, application of topical tranexamic acid following UV radiation exposure inhibited the development of expected skin hyperpigmentation and also reduced tyrosinase activity.4,5

The largest study on the use of oral tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma was a retrospective chart review of 561 melasma patients treated with tranexamic acid at a single center in Singapore.6 More than 90% of patients received prior treatment of their melasma, including bleaching creams and energy-based treatment. Among patients who received oral tranexamic acid over a 4-month period, 90% of patients demonstrated improvement in their melasma severity. Side effects were experienced by 7% of patients; the most common side effects were abdominal bloating and pain (experienced by 2% of patients). Notably, 1 patient developed deep vein thrombosis during treatment and subsequently was found to have protein S deficiency.6

Although the daily doses of tranexamic acid for the treatment of menorrhagia and perioperative hemophilia patients are 3900 mg and 30 to 40 mg/kg, respectively, effective daily doses reported for the treatment of melasma have ranged from the initial report of efficacy at 750 to 1500 mg to subsequent reports of improvement at daily doses of 500 mg.1,2,6-8

Challenges to the use of tranexamic acid for melasma treatment in the United States include the medicolegal environment, specifically the risks associated with using a systemic procoagulant medication for a cosmetic indication. Patients should be screened and counseled on the risks of developing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism prior to initiating treatment. Cost and accessibility also may limit the use of tranexamic acid in the United States. Tranexamic acid is available for off-label use in the United States with a prescription in the form of 650-mg tablets that can be split by patients to approximate twice-daily 325 mg dosing. This cosmetic indication poses an out-of-pocket cost to patients of over $110 per month or as low as $48 per month with a coupon at the time of publication.9

Given the potential for serious adverse effects with the use of systemic tranexamic acid, there has been interest in formulating and evaluating topical tranexamic acid for cosmetic indications.10-13 Topical tranexamic acid has been used alone and in conjunction with modalities to increase uptake, including intradermal injection, microneedling, and fractionated CO2 laser.12-14 Although these reports show initial promise, the currently available data are limited by small sample sizes, short treatment durations, lack of dose comparisons, and lack of short-term or long-term follow-up data. In addition to addressing these knowledge gaps in our understanding of topical tranexamic acid as a treatment option for melasma, further studies on the minimum systemic dose may address the downside of cost and potential for complications that may limit use of this medication in the United States.

The potential uses for tranexamic acid extend to the treatment of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and rosacea. Melanocytes cultured in media conditioned by fractionated CO2 laser–treated keratinocytes were found to have decreased tyrosinase activity and reduced melanin content when treated with tranexamic acid, suggesting the potential role for tranexamic acid to be used postprocedurally to reduce the risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in prone skin types.15 Oral and topical tranexamic acid also have been reported to improve the appearance of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, potentially relating to the inhibitory effects of tranexamic acid on neovascularization.3,16,17 Although larger-scale controlled studies are required for further investigation of tranexamic acid for these indications, it has shown early promise as an adjunctive treatment for several dermatologic disorders, including melasma, and warrants further characterization as a potential therapeutic option.

- Higashi N. Treatment of melasma with oral tranexamic acid. Skin Res. 1988;30:676-680.

- Tse TW, Hui E. Tranexamic acid: an important adjuvant in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:57-66.

- Sundbeck A, Karlsson L, Lilja J, et al. Inhibition of tumour vascularization by tranexamic acid. experimental studies on possible mechanisms. Anticancer Res. 1981;1:299-304.

- Maeda K, Naganuma M. Topical trans-4-aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid prevents ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;47:136-141.

- Li D, Shi Y, Li M, et al. Tranexamic acid can treat ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation in guinea pigs. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:289-292.

- Lee HC, Thng TG, Goh CL. Oral tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma: a retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:385-392.

- Kim HJ, Moon SH, Cho SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in melasma: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:776-781.

- Perper M, Eber AE, Fayne R, et al. Tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:373-381.

- Tranexamic acid. GoodRx website. https://www.goodrx.com/tranexamic-acid. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Kim SJ, Park JY, Shibata T, et al. Efficacy and possible mechanisms of topical tranexamic acid in melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:480-485.

- Ebrahimi B, Naeini FF. Topical tranexamic acid as a promising treatment for melasma. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:753-757.

- Xu Y, Ma R, Juliandri J, et al. Efficacy of functional microarray of microneedles combined with topical tranexamic acid for melasma: a randomized, self-controlled, split-face study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(19):e6897.

- Hsiao CY, Sung HC, Hu S, et al. Fractional CO2 laser treatment to enhance skin permeation of tranexamic acid with minimal skin disruption. Dermatology (Basel). 2015;230:269-275.

- Saki N, Darayesh M, Heiran A. Comparing the efficacy of topical hydroquinone 2% versus intradermal tranexamic acid microinjections in treating melasma: a split-face controlled trial [published online November 9, 2017]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2017.1392476.

- Kim MS, Bang SH, Kim JH, et al. Tranexamic acid diminishes laser-induced melanogenesis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:250-256.

- Kim MS, Chang SE, Haw S, et al. Tranexamic acid solution soaking is an excellent approach for rosacea patients: a preliminary observation in six patients. J Dermatol. 2013;40:70-71.

- Kwon HJ, Suh JH, Ko EJ, et al. Combination treatment of propranolol, minocycline, and tranexamic acid for effective control of rosacea [published online November 26, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12439.

- Higashi N. Treatment of melasma with oral tranexamic acid. Skin Res. 1988;30:676-680.

- Tse TW, Hui E. Tranexamic acid: an important adjuvant in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:57-66.

- Sundbeck A, Karlsson L, Lilja J, et al. Inhibition of tumour vascularization by tranexamic acid. experimental studies on possible mechanisms. Anticancer Res. 1981;1:299-304.

- Maeda K, Naganuma M. Topical trans-4-aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid prevents ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;47:136-141.

- Li D, Shi Y, Li M, et al. Tranexamic acid can treat ultraviolet radiation-induced pigmentation in guinea pigs. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:289-292.

- Lee HC, Thng TG, Goh CL. Oral tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma: a retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:385-392.

- Kim HJ, Moon SH, Cho SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in melasma: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:776-781.

- Perper M, Eber AE, Fayne R, et al. Tranexamic acid in the treatment of melasma: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:373-381.

- Tranexamic acid. GoodRx website. https://www.goodrx.com/tranexamic-acid. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- Kim SJ, Park JY, Shibata T, et al. Efficacy and possible mechanisms of topical tranexamic acid in melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:480-485.

- Ebrahimi B, Naeini FF. Topical tranexamic acid as a promising treatment for melasma. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:753-757.

- Xu Y, Ma R, Juliandri J, et al. Efficacy of functional microarray of microneedles combined with topical tranexamic acid for melasma: a randomized, self-controlled, split-face study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(19):e6897.

- Hsiao CY, Sung HC, Hu S, et al. Fractional CO2 laser treatment to enhance skin permeation of tranexamic acid with minimal skin disruption. Dermatology (Basel). 2015;230:269-275.

- Saki N, Darayesh M, Heiran A. Comparing the efficacy of topical hydroquinone 2% versus intradermal tranexamic acid microinjections in treating melasma: a split-face controlled trial [published online November 9, 2017]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2017.1392476.

- Kim MS, Bang SH, Kim JH, et al. Tranexamic acid diminishes laser-induced melanogenesis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:250-256.

- Kim MS, Chang SE, Haw S, et al. Tranexamic acid solution soaking is an excellent approach for rosacea patients: a preliminary observation in six patients. J Dermatol. 2013;40:70-71.

- Kwon HJ, Suh JH, Ko EJ, et al. Combination treatment of propranolol, minocycline, and tranexamic acid for effective control of rosacea [published online November 26, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12439.

Resident Pearl

- Oral tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent that can be used off-label for the treatment of melasma.

Videodermoscopy as a Novel Tool for Dermatologic Education

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

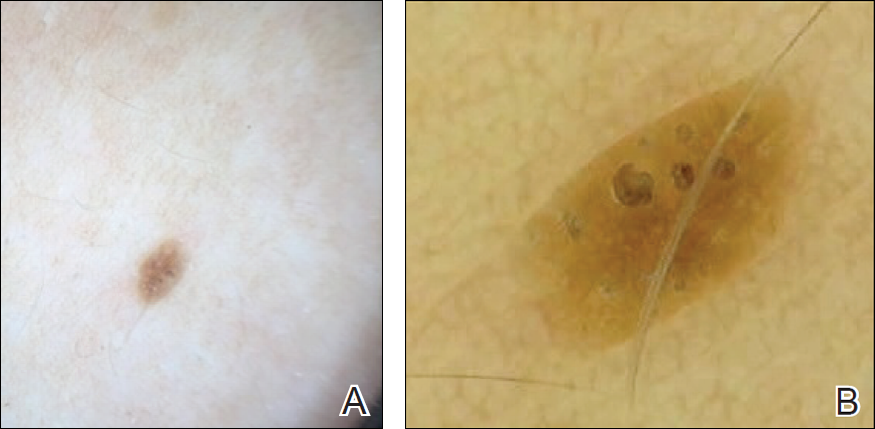

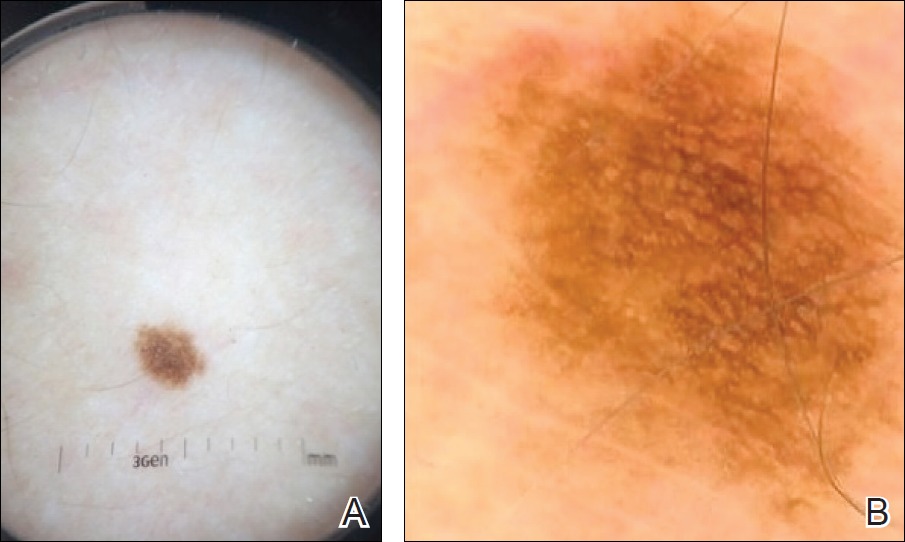

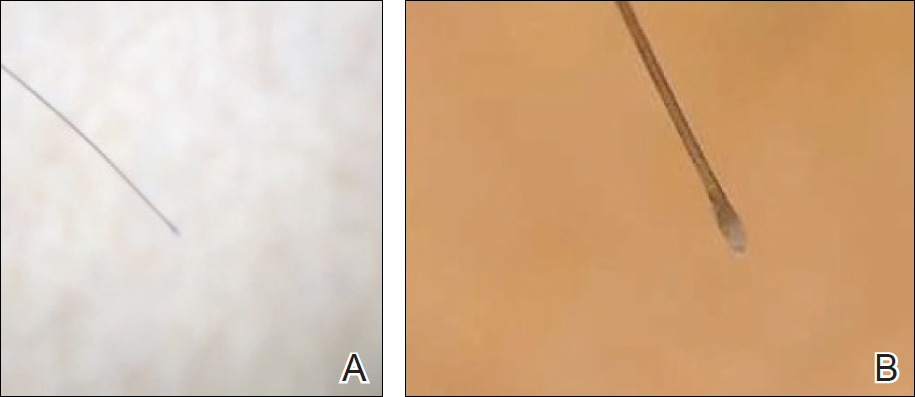

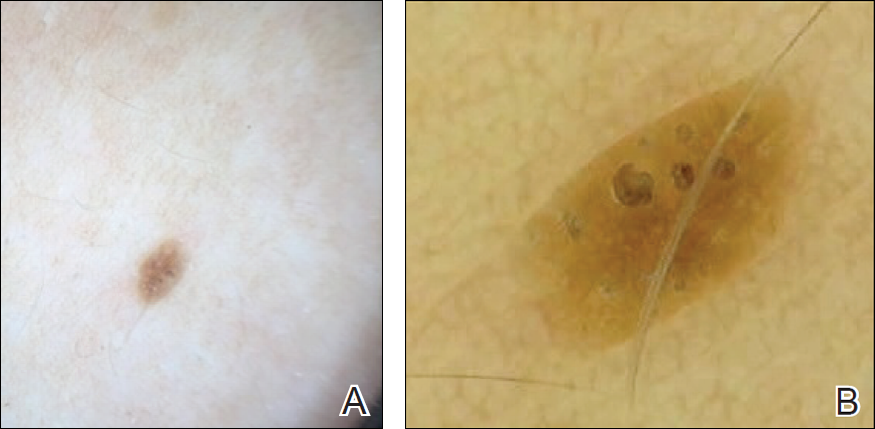

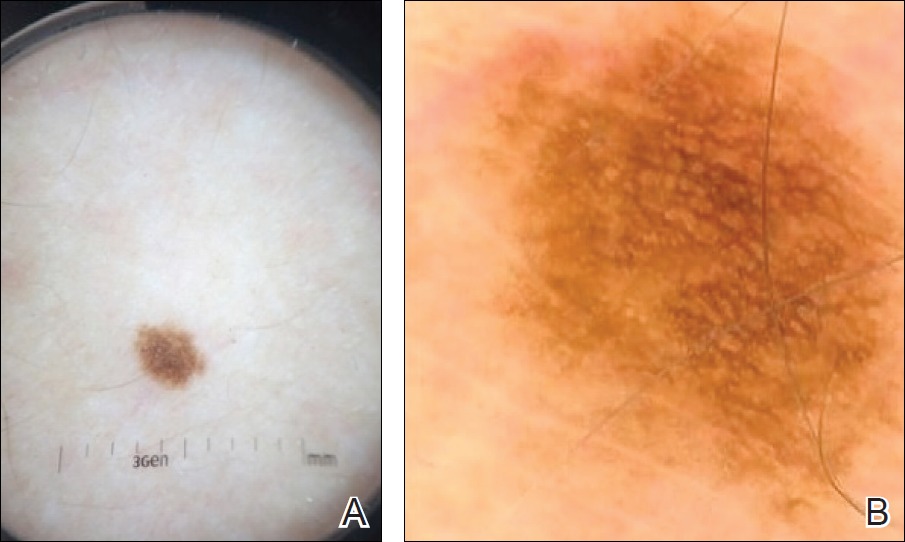

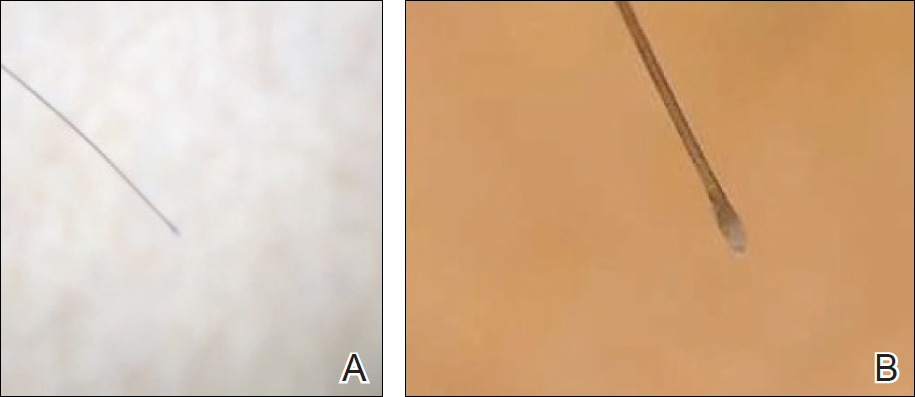

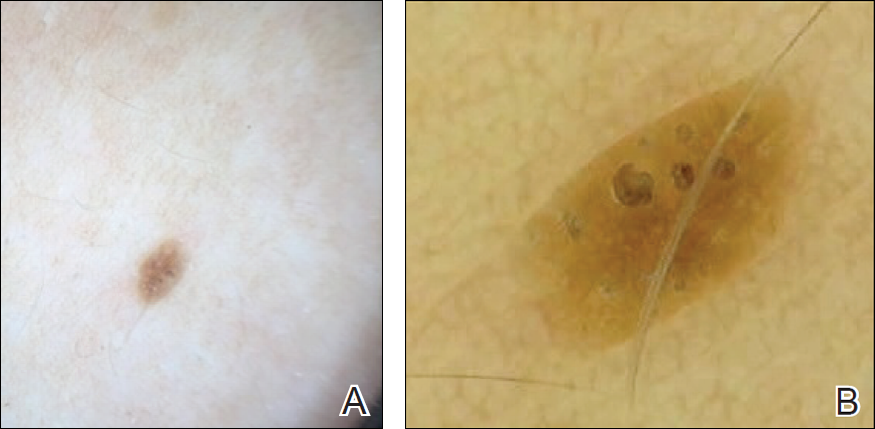

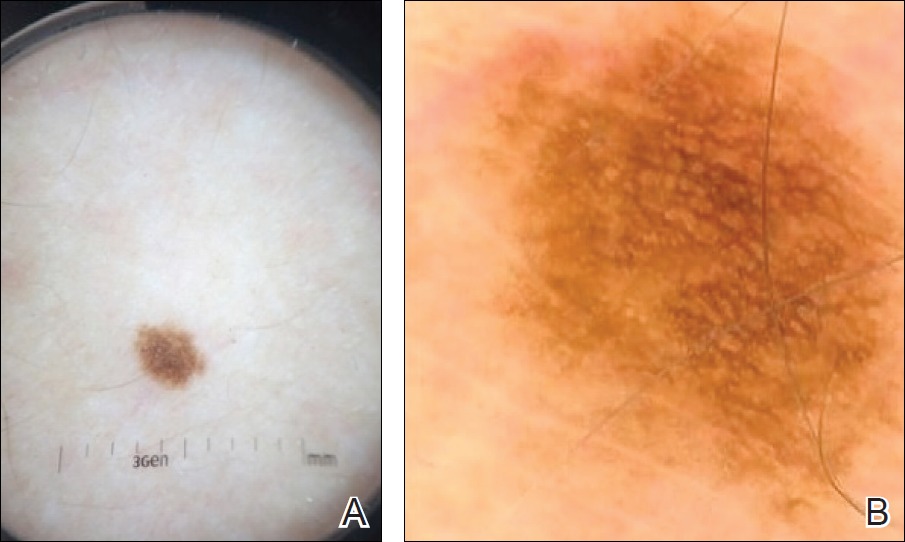

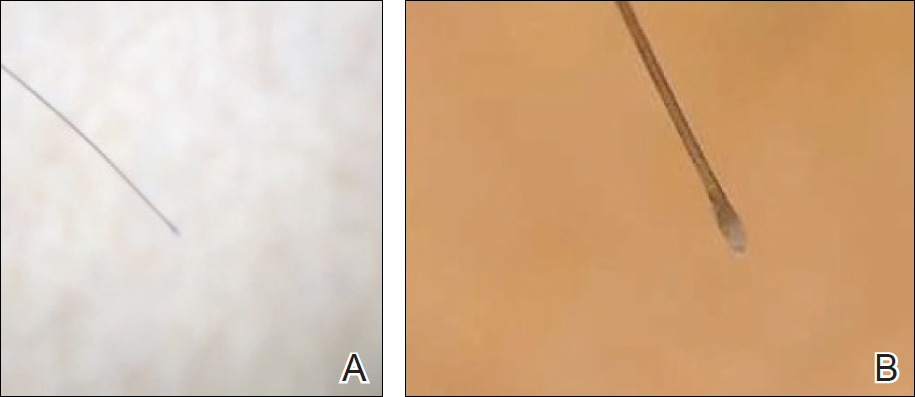

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

Resident Pearl

- Bedside dermoscopy training can be enhanced through the use of videodermoscopy, which permits simultaneous, high-magnification viewing.