User login

Erythematous Periumbilical Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

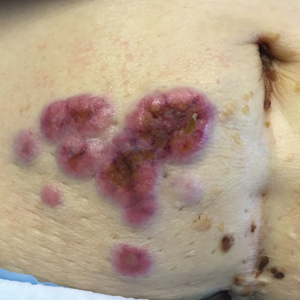

A 75-year-old woman (patient 1) with a history of localized invasive ductal breast cancer treated definitively with lumpectomy and radiation therapy more than a decade ago presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple periumbilical pink-red papules (top) of 2 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 10 days of acyclovir treatment prescribed by her primary care physician for presumed herpes zoster.

An 86-year-old man (patient 2) with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple pink periumbilical papules (bottom) of 6 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 21 days of valacyclovir treatment prescribed by his oncologist for presumed herpes zoster.

Friable Erythema and Erosions on the Mouth

The Diagnosis: Radiation Mucositis

The patient was undergoing active radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue, and according to the oncology team, the findings were in the precise location of radiation exposure. Radiation mucositis is a major and limiting side effect of radiation therapy for head and neck mucosal cancers, and symptom management is critical to ensure completion of the full radiation dose. Although infectious etiologies must be considered, the patient was already on prophylactic antiviral and antibacterial therapies. Moreover, the focal involvement with sparing of more mucosal tissue is atypical for most infections. Fixed drug reactions can present with localized mucosal and nonmucosal inflammation leading to erosion or ulceration. In this case, the only potential culprit was levofloxacin; however, it was initiated 2 days prior, and the patient never had reactions to this medication in the past.

Acute radiation mucositis is a transient but major limiting side effect of radiation therapy. The associated odynophagia, secondary infection, and reduced oral intake often can lead to diminished disease control secondary to treatment interruption and subsequent development of resistant tumor burden. Concurrent chemotherapy and alternated fractionation radiation therapy increase the incidence of mucositis. Trotti et al1 (n=6181) reported that severe mucositis (grades 3 to 4) was found in 56% of patients receiving altered fractionation radiation therapy compared to 34% of patients who received conventional radiation therapy. Other risk factors related to the development of acute radiation mucositis include associated chemotherapy, age (>65 years), poor oral hygiene, diabetes mellitus, and prior periodontal disease.2

Radiation causes direct cellular damage to keratinocytes, leading to ulceration and erythema, as well as keratinocyte stem cells, which interferes with the healing process. Typical symptoms of mucosal radiation injury may include erythema (asymptomatic or causing intolerance of warm foods) that develops at the end of the second week of radiation therapy, focal areas of desquamation that develops in week 3, and confluent mucositis that can further progress to ulceration and necrosis in weeks 4 to 5.2 The development of dysgeusia, which is estimated to occur in 67% of patients receiving radiotherapy and 76% of patients receiving combination therapy, also can contribute to nutritional difficulties and weight loss.3

Avoiding overtreatment by constraining radiation volume and limiting concurrent chemotherapy are important preventative measures. The mainstay for managing mucositis includes symptomatic relief with oral hygiene, topical agents, topical plus systemic analgesia, dietary changes, and treatment of associated infections. Benzydamine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, is not available in the United States but has been shown to effectively improve symptoms.4 Various formulations of topical anesthetics consisting of diphenhydramine with or without corticosteroids, antibiotics, and antifungals help alleviate symptoms of mucositis; however, no single formulation has been studied. Low-level laser therapy also has shown efficacy in managing symptoms of mucositis.5,6 For persistent odynophagia, systemic opioid therapy should be attempted to achieve uninterrupted radiation therapy. Severe mucositis requires balancing risks and benefits of interrupting treatment, as additional damage may cause permanent mucosal injury.

Our patient had adequate symptom control with benzocaine lozenges and a combination mouthwash containing diphenhydramine, nystatin, lidocaine, hydrocortisone, and tetracycline. He required only occasional doses of systemic oxycodone. After a 1-week hospital admission for treatment of the pneumonia, he resumed radiation therapy and completed a full 8-week radiation course.

- Trotti A, Bellm LA, Epstein JB, et al. Mucositis incidence, severity and associated outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: a systematic literature review. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:253-262.

- Mallick S, Benson R, Rath GK. Radiation induced oral mucositis: a review of current literature on prevention and management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:2285-2293.

- Hovan AJ, Williams PM, Stevenson-Moore P, et al; Dysgeusia Section, Oral Care Study Group, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). A systematic review of dysgeusia induced by cancer therapies. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1081-1087.

- Epstein JB, Silverman S, Paggiarino DA, et al. Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation‐induced oral mucositis. Cancer. 2001;92:875-885.

- Henke M, Alfonsi M, Foa P, et al. Palifermin decreases severe oral mucositis of patients undergoing postoperative radiochemotherapy for head and neck cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2815-2820.

- Bensadoun RJ, Nair RG. Low-level laser therapy in the prevention and treatment of cancer therapy-induced mucositis: 2012 state of the art based on literature review and meta-analysis. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:363-370.

The Diagnosis: Radiation Mucositis

The patient was undergoing active radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue, and according to the oncology team, the findings were in the precise location of radiation exposure. Radiation mucositis is a major and limiting side effect of radiation therapy for head and neck mucosal cancers, and symptom management is critical to ensure completion of the full radiation dose. Although infectious etiologies must be considered, the patient was already on prophylactic antiviral and antibacterial therapies. Moreover, the focal involvement with sparing of more mucosal tissue is atypical for most infections. Fixed drug reactions can present with localized mucosal and nonmucosal inflammation leading to erosion or ulceration. In this case, the only potential culprit was levofloxacin; however, it was initiated 2 days prior, and the patient never had reactions to this medication in the past.

Acute radiation mucositis is a transient but major limiting side effect of radiation therapy. The associated odynophagia, secondary infection, and reduced oral intake often can lead to diminished disease control secondary to treatment interruption and subsequent development of resistant tumor burden. Concurrent chemotherapy and alternated fractionation radiation therapy increase the incidence of mucositis. Trotti et al1 (n=6181) reported that severe mucositis (grades 3 to 4) was found in 56% of patients receiving altered fractionation radiation therapy compared to 34% of patients who received conventional radiation therapy. Other risk factors related to the development of acute radiation mucositis include associated chemotherapy, age (>65 years), poor oral hygiene, diabetes mellitus, and prior periodontal disease.2

Radiation causes direct cellular damage to keratinocytes, leading to ulceration and erythema, as well as keratinocyte stem cells, which interferes with the healing process. Typical symptoms of mucosal radiation injury may include erythema (asymptomatic or causing intolerance of warm foods) that develops at the end of the second week of radiation therapy, focal areas of desquamation that develops in week 3, and confluent mucositis that can further progress to ulceration and necrosis in weeks 4 to 5.2 The development of dysgeusia, which is estimated to occur in 67% of patients receiving radiotherapy and 76% of patients receiving combination therapy, also can contribute to nutritional difficulties and weight loss.3

Avoiding overtreatment by constraining radiation volume and limiting concurrent chemotherapy are important preventative measures. The mainstay for managing mucositis includes symptomatic relief with oral hygiene, topical agents, topical plus systemic analgesia, dietary changes, and treatment of associated infections. Benzydamine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, is not available in the United States but has been shown to effectively improve symptoms.4 Various formulations of topical anesthetics consisting of diphenhydramine with or without corticosteroids, antibiotics, and antifungals help alleviate symptoms of mucositis; however, no single formulation has been studied. Low-level laser therapy also has shown efficacy in managing symptoms of mucositis.5,6 For persistent odynophagia, systemic opioid therapy should be attempted to achieve uninterrupted radiation therapy. Severe mucositis requires balancing risks and benefits of interrupting treatment, as additional damage may cause permanent mucosal injury.

Our patient had adequate symptom control with benzocaine lozenges and a combination mouthwash containing diphenhydramine, nystatin, lidocaine, hydrocortisone, and tetracycline. He required only occasional doses of systemic oxycodone. After a 1-week hospital admission for treatment of the pneumonia, he resumed radiation therapy and completed a full 8-week radiation course.

The Diagnosis: Radiation Mucositis

The patient was undergoing active radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue, and according to the oncology team, the findings were in the precise location of radiation exposure. Radiation mucositis is a major and limiting side effect of radiation therapy for head and neck mucosal cancers, and symptom management is critical to ensure completion of the full radiation dose. Although infectious etiologies must be considered, the patient was already on prophylactic antiviral and antibacterial therapies. Moreover, the focal involvement with sparing of more mucosal tissue is atypical for most infections. Fixed drug reactions can present with localized mucosal and nonmucosal inflammation leading to erosion or ulceration. In this case, the only potential culprit was levofloxacin; however, it was initiated 2 days prior, and the patient never had reactions to this medication in the past.

Acute radiation mucositis is a transient but major limiting side effect of radiation therapy. The associated odynophagia, secondary infection, and reduced oral intake often can lead to diminished disease control secondary to treatment interruption and subsequent development of resistant tumor burden. Concurrent chemotherapy and alternated fractionation radiation therapy increase the incidence of mucositis. Trotti et al1 (n=6181) reported that severe mucositis (grades 3 to 4) was found in 56% of patients receiving altered fractionation radiation therapy compared to 34% of patients who received conventional radiation therapy. Other risk factors related to the development of acute radiation mucositis include associated chemotherapy, age (>65 years), poor oral hygiene, diabetes mellitus, and prior periodontal disease.2

Radiation causes direct cellular damage to keratinocytes, leading to ulceration and erythema, as well as keratinocyte stem cells, which interferes with the healing process. Typical symptoms of mucosal radiation injury may include erythema (asymptomatic or causing intolerance of warm foods) that develops at the end of the second week of radiation therapy, focal areas of desquamation that develops in week 3, and confluent mucositis that can further progress to ulceration and necrosis in weeks 4 to 5.2 The development of dysgeusia, which is estimated to occur in 67% of patients receiving radiotherapy and 76% of patients receiving combination therapy, also can contribute to nutritional difficulties and weight loss.3

Avoiding overtreatment by constraining radiation volume and limiting concurrent chemotherapy are important preventative measures. The mainstay for managing mucositis includes symptomatic relief with oral hygiene, topical agents, topical plus systemic analgesia, dietary changes, and treatment of associated infections. Benzydamine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, is not available in the United States but has been shown to effectively improve symptoms.4 Various formulations of topical anesthetics consisting of diphenhydramine with or without corticosteroids, antibiotics, and antifungals help alleviate symptoms of mucositis; however, no single formulation has been studied. Low-level laser therapy also has shown efficacy in managing symptoms of mucositis.5,6 For persistent odynophagia, systemic opioid therapy should be attempted to achieve uninterrupted radiation therapy. Severe mucositis requires balancing risks and benefits of interrupting treatment, as additional damage may cause permanent mucosal injury.

Our patient had adequate symptom control with benzocaine lozenges and a combination mouthwash containing diphenhydramine, nystatin, lidocaine, hydrocortisone, and tetracycline. He required only occasional doses of systemic oxycodone. After a 1-week hospital admission for treatment of the pneumonia, he resumed radiation therapy and completed a full 8-week radiation course.

- Trotti A, Bellm LA, Epstein JB, et al. Mucositis incidence, severity and associated outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: a systematic literature review. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:253-262.

- Mallick S, Benson R, Rath GK. Radiation induced oral mucositis: a review of current literature on prevention and management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:2285-2293.

- Hovan AJ, Williams PM, Stevenson-Moore P, et al; Dysgeusia Section, Oral Care Study Group, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). A systematic review of dysgeusia induced by cancer therapies. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1081-1087.

- Epstein JB, Silverman S, Paggiarino DA, et al. Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation‐induced oral mucositis. Cancer. 2001;92:875-885.

- Henke M, Alfonsi M, Foa P, et al. Palifermin decreases severe oral mucositis of patients undergoing postoperative radiochemotherapy for head and neck cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2815-2820.

- Bensadoun RJ, Nair RG. Low-level laser therapy in the prevention and treatment of cancer therapy-induced mucositis: 2012 state of the art based on literature review and meta-analysis. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:363-370.

- Trotti A, Bellm LA, Epstein JB, et al. Mucositis incidence, severity and associated outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: a systematic literature review. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:253-262.

- Mallick S, Benson R, Rath GK. Radiation induced oral mucositis: a review of current literature on prevention and management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:2285-2293.

- Hovan AJ, Williams PM, Stevenson-Moore P, et al; Dysgeusia Section, Oral Care Study Group, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). A systematic review of dysgeusia induced by cancer therapies. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1081-1087.

- Epstein JB, Silverman S, Paggiarino DA, et al. Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation‐induced oral mucositis. Cancer. 2001;92:875-885.

- Henke M, Alfonsi M, Foa P, et al. Palifermin decreases severe oral mucositis of patients undergoing postoperative radiochemotherapy for head and neck cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2815-2820.

- Bensadoun RJ, Nair RG. Low-level laser therapy in the prevention and treatment of cancer therapy-induced mucositis: 2012 state of the art based on literature review and meta-analysis. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:363-370.

A 68-year-old man with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue presented with a sore throat and odynophagia of 4 days' duration. At the time he was undergoing radiation therapy for the squamous cell carcinoma, and multiple myeloma was being actively treated with carfilzomib and pomalidomide. At the time of symptom onset he also was undergoing treatment with levofloxacin for community-acquired pneumonia. On day 2 of antibiotic therapy he noted pain with swallowing and an intolerance to warm foods. He was unaware of any new rash or lesions of the lips or mouth. He denied dysgeusia, changes in speech, bleeding, trauma, or recent smoking. He was taking prophylactic acyclovir and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole due to chemotherapy. Physical examination revealed a posterior oropharynx and uvula with well-defined friable erythema and erosions covered by white patches. There was no mucosal ulceration and no notable skin findings. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.