User login

Menstrual migraines: Which options and when?

› Consider recommending that patients with menstrual migraines try using prophylactic triptans 2 days before the onset of menses. B

› Advise against estrogen-containing contraception for women who have menstrual migraines with aura, who smoke, or are over 35, due to the increased risk of stroke (absolute contraindication). A

› Consider estrogen-containing contraception if the benefits outweigh the risks for women with migraines who are under 35 and do not have aura (relative contraindication). A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Mary, a 34-year-old woman, is a new patient to your practice after moving to the area for a job. She has a history of migraine headaches triggered by her menstrual periods. She has been taking combined oral contraceptives (COCs) since she was 17, with a few years off when she had 2 children. Her migraines improved when she was pregnant, but worsened postpartum with each of her daughters to a point where she had to stop breastfeeding at 4 months to go back on the pills.

On the COCs, she gets one or 2 mild-to-moderate headaches a month. She uses sumatriptan for abortive treatment with good relief. She has not missed work in the past 4 years because of her migraines. During the 6 months she was off COCs when trying to get pregnant, she routinely missed 2 to 3 workdays per month due to migraines. She knows when she is going to get a headache because she sees flashing lights in her left visual field. She has no other neurologic symptoms with the headaches, and the character of the headaches has not changed. She is a non-smoker, has normal blood pressure and lipid levels, and no other vascular risk factors.

You review her history and talk to her about the risk of stroke with migraines and with COCs. She is almost 35 years of age and you recommend stopping the COCs due to the risk. She feels strongly that she wants to continue taking the COCs, saying her quality of life is poor when she is off the pills. What should you do?

Migraine headaches are 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women than in men,1 with a lifetime risk of 43% vs 18%, respectively.2 Women account for about 80% of the $1 billion spent each year in the United States in medical expenses and lost work productivity related to migraines.1,2

Clinical patterns suggestive of menstrual migraine. About half of women affected by migraine have menstrually-related migraines (MRM); 3% to 12% have pure menstrual migraines (PMM).3 MRM and PMM are both characterized by the presence of symptoms in at least 2 to 3 consecutive cycles, with symptoms occurring from between 2 days before to 3 days after the onset of menstruation. However, in PMM, symptoms do not occur at any other time of the menstrual cycle; in MRM, symptoms can occur at other times of the cycle. PMM is more likely to respond to hormone therapy than is MRM.

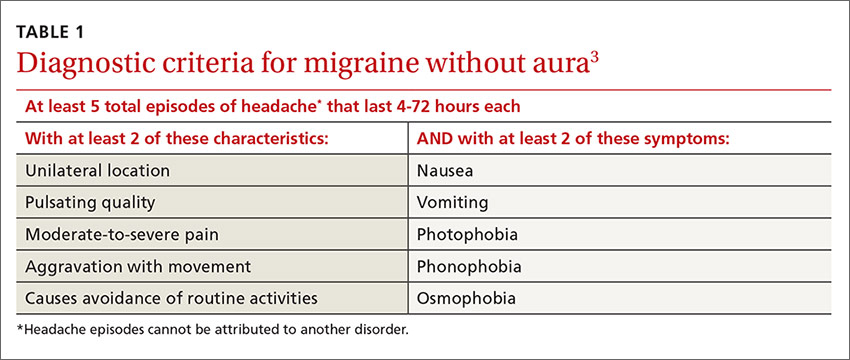

Multiple studies in the United States, Europe, and Asia have noted that migraines related to menses typically last longer, are more severe, less likely to be associated with aura, and more likely to be recurrent and recalcitrant to treatment than non-menstrual migraines.1 TABLE 13 describes diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura.

Possible mechanisms of MRM and PMM. The etiology of migraine is not well understood and is likely multifactorial.4 Incidence of menstrual migraines is related to cyclic changes in female hormones—specifically, the decreasing levels of estrogen that typically happen the week before onset of menses.1 The mechanism is not yet clear, though it is thought that a decline in estrogen levels triggers a decline in serotonin levels, which may lead to cranial vasodilation and sensitization of the trigeminal nerve.5,6 Estrogen decline has also been linked to increased cranial nociception as well as decreased endogenous opioid activity. A study using positron emission tomography found increased activity of serotonergic neurons in migraineurs.7 The evidence that triptans and serotonin receptor agonists are effective in the treatment of migraine also supports the theory that serotonin neurohormonal signaling pathways play a critical role in the pathogenesis of migraines.7

Prevalence patterns point to the role of estrogen. The prevalence of migraines in women increases around puberty, peaks between ages 30 and 40, and decreases after natural menopause.6 Migraine prevalence increases during the first week postpartum, when levels of estrogen and progesterone decrease suddenly and significantly.1 Migraine frequency and intensity decrease in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and after menopause, when estrogen levels fluctuate significantly less.1 In the Women’s Health Initiative study, women who used hormone replacement therapy (HRT) had a 42% increased risk of migraines compared with women in the study who had never used HRT.8

The association of migraine with female hormones was further supported by a Dutch study of male-to-female transgender patients on estrogen therapy, who had a 26% incidence of migraine, equivalent to the 25% prevalence in natal female controls in this study, compared with just 7.5% in male controls.9 The association between migraine and estrogen withdrawal was investigated in studies performed more than 40 years ago, when women experiencing migraines around the time of menses were given intramuscular estradiol and experienced a delay in symptom onset.10

Abortive and prophylactic treatments: Factors that guide selection

In considering probable menstrual migraine, take a detailed history, review headache diaries if available to determine association of headaches with menses, and perform a thorough neurologic examination. If a diagnosis of menstrual migraine is established, discuss the benefits of different treatment options, both abortive and prophylactic.

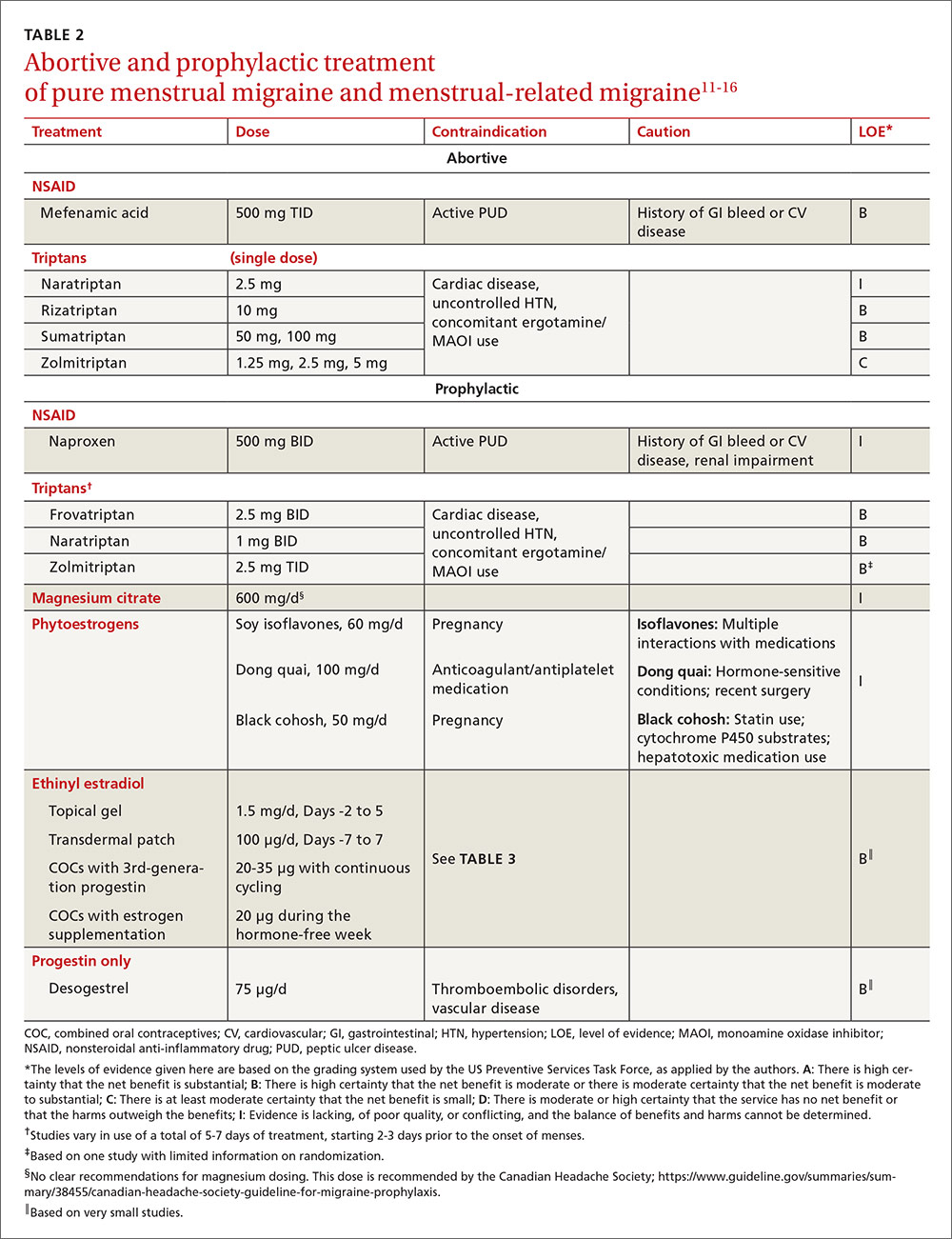

For the patient with MRM, take into account frequency of symptoms, predictability of menstruation, medication costs, and comorbidities. Both triptans and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be effective treatments for MRM.11 Abortive therapy may be appropriate if a patient prefers to take medication intermittently, if her menses are unpredictable, or if she does not get migraine headaches with every menses. Mefenamic acid, sumatriptan, and rizatriptan have category B recommendations for abortive treatment for menstrual migraines (TABLE 211-16). (For the patient who has regular MRM but unpredictable menses, ovulation predictor kits can be used to help predict the onset of menses, although this would involve additional cost.)

For the patient who has predictable menses and regularly occurring menstrual migraine, some data show that a short-term prophylactic regimen with triptans started 2 to 3 days before the onset of menses and continued for 5 to 7 days total can reduce the incidence of menstrual migraine (TABLE 211-16). At least one high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed a significant reduction in the incidence of MRM when women were treated prophylactically with frovatriptan, a long-acting triptan with a half-life of approximately 26 hours. Participants received frovatriptan 2.5 mg once a day or twice a day or placebo in the perimenstrual period (day -2 to +3). The incidence of MRM was 52%, 41%, and 67%, respectively (P<.0001).11,17

Another RCT of fair quality examined the effect of naratriptan (half-life 6-8 hours) on the median number of menstrual migraines over 4 menstrual cycles. Women who received 1 mg of naratriptan BID for 2 to 3 days before menses had 2 MRM episodes over the 4 cycles compared with 4 MRM episodes in women who received placebo over the same time period (P<.05).11,18 A third RCT, also of fair quality, compared 2 different regimens of zolmitriptan (half-life 3 hours) with placebo and found that women who received 2.5 mg of zolmitriptan either BID or TID 2 to 3 days prior to menses had a reduction both in frequency of menstrual migraines and in the mean number of breakthrough headaches per menstrual cycle, as well as a reduction in the need for rescue medications.12,19 Triptans are contraindicated in women with a history of cardiac disease or uncontrolled hypertension. Also, triptans can be expensive, precluding their use for some patients.

Evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of NSAIDs as prophylaxis for MRM.11 NSAIDs may be contraindicated in women with a history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal bleeding. That said, if NSAIDs are not contraindicated, a trial may be reasonable given their low cost.

Data are sparse on the use of vitamins and supplements in treating and preventing PMM or MRM. In one very small double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 1991 (N=24, with efficacy data for 20), participants received a 2-week course of oral magnesium premenstrually. There was a statistically significant reduction in the number of days with headache per month (from 4.7±3.1 days to 2.4±2.2 days; P<.01) and in the total pain index (P<.03).20 A number of studies have demonstrated a correlation between hypomagnesemia and migraine headaches.5,21 The exact mechanism for this relationship is unclear.

Some recent evidence-based reviews have examined the efficacy of nutraceuticals such as magnesium, feverfew, butterbur, coenzyme Q10, and riboflavin on typical migraine, but it is not clear if these results are translatable to the treatment and prophylaxis of menstrual migraine.11,22 A multicenter, single-blind, RCT is underway to examine the efficacy of acupuncture as prophylaxis for MRM.23

Estrogen: Prescribing criteria are strict

Most studies examining the role of exogenous estrogen in reducing menstrual migraines have used topical estrogen (either in patch or gel formulations) in the perimenstrual window (TABLE 211-16). The topical estrogen route has been examined, in particular, as it is presumed to confer less risk of hypercoagulability by avoiding first-pass metabolism. However, there is conflicting evidence on this issue, in particular regarding premenopausal women.13,25 Additionally, many of the studies of estrogen supplementation show a trend toward increased headache once estrogen is discontinued, presumably due to estrogen withdrawal.10,24

That said, one study by MacGregor, et al demonstrates that the use of estradiol gel in the perimenstrual window leads to a 22% reduction in migraine days as well as less severe migrainous symptoms.26 This trend has been demonstrated in other studies examining estrogen supplementation. Of note, the estrogen studies generally are small, older, and of fair to poor quality.11 These studies have used higher doses of estrogen than are commonly used for contraception today because lower doses of estrogen seem not to have the same impact on migraine.5,24

As for COCs, with either normal or extended cycling, data are more mixed than for estrogen supplementation alone; equivalent numbers of women experience improvement, no change, or worsening of their headache pattern. Many women have continuing or worsening migraines in the hormone-free week, and thus most studies have examined the use of extended cycling COCs.5 Sulak, et al demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in headache frequency using extended-cycling COCs, though they did not examine MRM in particular.27 The efficacy of extended-cycling COCs for reduction of MRM was confirmed by Coffee and colleagues with a small but statistically significant decrease in daily headache scores.28

Adverse effects. All estrogen therapies pose the risk of adverse effects (deep vein thrombosis, hypertension, breast tenderness, nausea, etc). Additionally, estrogen supplementation may actually trigger migraines in some women if, when it is discontinued, the blood estrogen level does not remain above a threshold concentration.5,10,24 Estrogen may also trigger migraine in previously headache-free women and may convert migraine without aura into migraine with aura. In either case, therapy should be stopped.5,24

There is promising evidence from 2 small RCTs and one observational trial that progestin-only contraceptive pills (POP) may reduce the frequency and severity of menstrual migraines (TABLE 211-16). More prospective data are needed to confirm this reduction, as there have not been specific studies examining other progesterone-only preparations to prevent menstrual migraines.

Risk of ischemic stroke. Unfortunately, there are population data showing that second-generation and, to a smaller degree, third-generation progestins, which include the desogestrel used in the above studies, may increase the risk of ischemic stroke. This is a particular concern in women who experience migraine.29 Second-generation progestins include levonorgestrel, which is in the levonorgestrel IUD; however, there is no direct evidence for increased ischemic stroke in this particular preparation, and the circulating plasma levels are low. Etonorgestrel, the active ingredient in the contraceptive implant, is a third-generation progestin, though there is no direct evidence of increased ischemic stroke with use of the etonorgestrel implant.

There is a 2- to 4-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke in women who experience migraine.1,5,30 As stated above, this risk may be further increased by some progesterone formulations. But there is also a demonstrable increase in ischemic stroke risk with the use of estrogen, particularly at the higher concentrations that have been shown to prevent MRM.31,32 The overall incidence of ischemic stroke in menstrual-age women is low, which has limited the number of studies with enough power to quantify the absolute increased risk of stroke in conjunction with estrogen use. Nevertheless, exogenous estrogen is thought to increase the risk of ischemic stroke an additional 2- to 4-fold.1,5,29,30,32-34

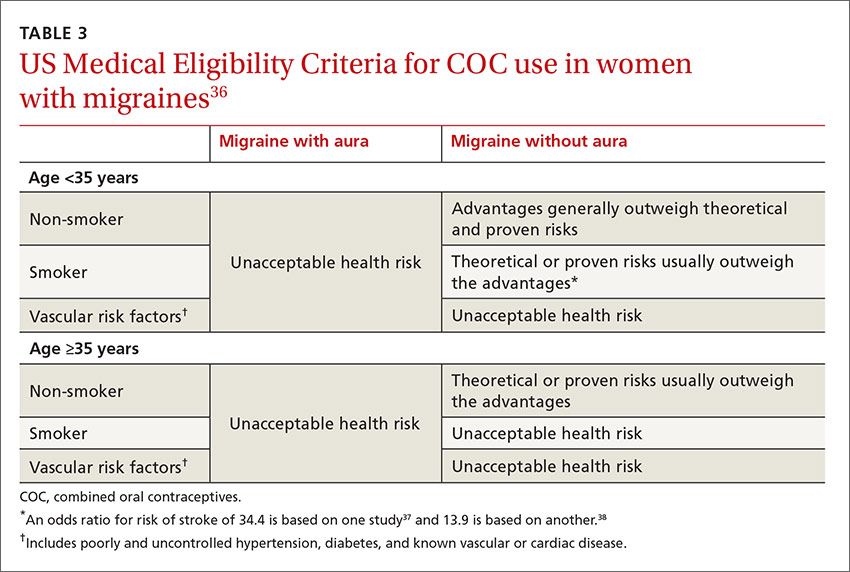

Women who experience aura. MRM, as it is defined, typically excludes women who experience aura; however, the number of women who experience aura with migraine either in proximity to their menses or throughout the month has not been well documented. The risk of ischemic stroke is higher for women who experience migraine with aura than those with migraine alone, possibly because aura is associated with reduced regional vascular flow leading to hypoperfusion, which sets the stage for a possible ischemic event.4,5,35 The risk of ischemic stroke is amplified further for women who are over 35, who smoke, or who have additional vascular risk factors (eg, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or known vascular or cardiac disease).1,5,34 This array of evidence serves as the basis for the US Medical Eligibility Criteria (USMEC) recommendations36 for hormonal contraceptive use, in particular the absolute contraindication for estrogen use in women who experience migraine with aura (TABLE 336-38).

CASE › Given Mary’s experience of aura with migraine, you talk with her at length about the risk of ischemic stroke and the USMEC recommendation that she absolutely should not be taking COCs. You suggest a progestin-only method of contraception such as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a progestin intrauterine device, or a hormonal implant, which may suppress ovulation and decrease her headaches. You discuss that while some women may have headaches with these progestin-only methods, stroke risk is significantly reduced. You also suggest a trial of prophylactic triptans as another possible option.

She says she understands the increased risk of stroke but is still unwilling to try anything else right now due to worries about her quality of life. You decide jointly to refill COCs for 3 months, and you document the shared decision process in the chart. After advising the patient that you will not continue to prescribe COCs for an extended period of time, you also schedule a follow-up appointment to further discuss risks and benefits of migraine treatment and means of reducing other risk factors for stroke.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, University of Wisconsin, Department of Family Medicine, 1100 Delaplaine Ct, Madison, WI 53715; sbschrag@wisc.edu.

1. MacGregor EA, Rosenberg JD, Kurth T. Sex-related differences in epidemiological and clinic-based headache studies. Headache. 2011;51:843-859.

2. Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed ML, et al. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:1170-1178.

3. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd ed. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808.

4. Garza I, Swanson JW, Cheshire WP Jr, et al. Headache and other craniofacial pain. In: Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J, et al, eds. Bradley’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1703-1744.

5. Martin VT, Behbehani M. Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis – part 2. Headache. 2006;46:365-386.

6. Brandes JL. The influence of estrogen on migraine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006; 295:1824-1830.

7. Loder EW. Menstrual migraine: pathophysiology, diagnosis and impact. Headache. 2006;46 (Suppl 2):S55-S60.

8. Misakian AL, Langer RD, Bensenor IM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and migraine headache. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2003;12:1027-1036.

9. Pringsheim T, Gooren L. Migraine prevalence in male to female transsexuals on hormone therapy. Neurology. 2004;63:593-594.

10. Somerville BW. The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 1972;22:355-365.

11. Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D. Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache: evidence-based review. Neurology. 2008;70:1555-1563.

12. Hu Y, Guan X, Fan L, et al. Triptans in prevention of menstrual migraine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Headache Pain. 2013;14:7.

13. Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:1227-1231.

14. Merki-Feld GS, Imthurn B, Langner R, et al. Headache frequency and intensity in female migraineurs using desogestrel-only contraception: a retrospective pilot diary study. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:340-346.

15.

16. Morotti M, Remorgida V, Venturini PL, et al. Progestin-only contraception compared with extended combined oral contraceptive in women with migraine without aura: a retrospective pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;183:178-182.

17. Silberstein SD, Elkind AH, Schreiber C, et al. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 2004;63:261-269.

18. Newman L, Mannix LK, Landy S, et al. Naratriptan as short-term prophylaxis of menstrually associated migraine: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2001;41:248-256.

19. Tuchman MM, Hee A, Emeribe U, et al. Oral zolmitriptan in the short-term prevention of menstrual migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:877-886.

20. Facchinetti F, Sances G, Borella P, et al. Magnesium prophylaxis of menstrual migraine: effects on intracellular magnesium. Headache. 1991;31:298-301.

21. Teigen L, Boes CJ. An evidence-based review of oral magnesium supplementation in the preventive treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia. 2014;35:912-922.

22. Taylor FR. Nutraceuticals and headache: the biological basis. Headache. 2011;51:484-501.

23. Zhang XZ, Zhang L, Guo J, et al. Acupuncture as prophylaxis for menstrual-related migraine: study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:374.

24. MacGregor EA. Oestrogen and attacks of migraine with and without aura. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:354-361.

25. Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, et al. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive system users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:339-346.

26. MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, et al. Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology. 2006;67:2159-2163.

27. Sulak P, Willis S, Kuehl T, et al. Headaches and oral contraceptives: impact of eliminating the standard 7-day placebo interval. Headache. 2007;47:27-37.

28. Coffee AL, Sulak PJ, Hill AJ, et al. Extended cycle combined oral contraceptives and prophylactic frovatriptan during the hormone-free interval in women with menstrual-related migraines. J Womens Health. 2014;23:310-317.

29. Lidegaard Ø, Kreiner S. Contraceptives and cerebral thrombosis: a five-year national case-control study. Contraception. 2002;65:197-205.

30. Bousser MG. Estrogen, migraine, and stroke. Stroke. 2004;35(Suppl 1):2652-2656.

31. Gillum LA, Mamidipudi SK, Johnston SC. Ischemic stroke risk with oral contraceptives: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:72-78.

32. Donaghy M, Chang CL, Poulter N. Duration, frequency, recency, and type of migraine and the risk of ischaemic stroke in women of childbearing age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:747-750.

33. Sacco S, Ricci S, Degan D. Migraine in women: the role of hormones and their impact on vascular diseases. J Headache Pain. 2012;12:177-189.

34. Merikangas KR, Fenton BT, Cheng SH, et al. Association between migraine and stroke in a large-scale epidemiological study of the United States. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:362-368.

35. MacClellan LR, Giles W, Cole J, et al. Probable migraine with visual aura and risk of ischemic stroke: the stroke prevention in young women study. Stroke. 2007;38:2438-2445.

36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep

37. Chang CL, Donaghy M, Poulter N. Migraine and stroke in young women: case-control study. The World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. BMJ. 1999;318:13-18.

38. Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglésias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischaemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310:830-833.

› Consider recommending that patients with menstrual migraines try using prophylactic triptans 2 days before the onset of menses. B

› Advise against estrogen-containing contraception for women who have menstrual migraines with aura, who smoke, or are over 35, due to the increased risk of stroke (absolute contraindication). A

› Consider estrogen-containing contraception if the benefits outweigh the risks for women with migraines who are under 35 and do not have aura (relative contraindication). A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Mary, a 34-year-old woman, is a new patient to your practice after moving to the area for a job. She has a history of migraine headaches triggered by her menstrual periods. She has been taking combined oral contraceptives (COCs) since she was 17, with a few years off when she had 2 children. Her migraines improved when she was pregnant, but worsened postpartum with each of her daughters to a point where she had to stop breastfeeding at 4 months to go back on the pills.

On the COCs, she gets one or 2 mild-to-moderate headaches a month. She uses sumatriptan for abortive treatment with good relief. She has not missed work in the past 4 years because of her migraines. During the 6 months she was off COCs when trying to get pregnant, she routinely missed 2 to 3 workdays per month due to migraines. She knows when she is going to get a headache because she sees flashing lights in her left visual field. She has no other neurologic symptoms with the headaches, and the character of the headaches has not changed. She is a non-smoker, has normal blood pressure and lipid levels, and no other vascular risk factors.

You review her history and talk to her about the risk of stroke with migraines and with COCs. She is almost 35 years of age and you recommend stopping the COCs due to the risk. She feels strongly that she wants to continue taking the COCs, saying her quality of life is poor when she is off the pills. What should you do?

Migraine headaches are 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women than in men,1 with a lifetime risk of 43% vs 18%, respectively.2 Women account for about 80% of the $1 billion spent each year in the United States in medical expenses and lost work productivity related to migraines.1,2

Clinical patterns suggestive of menstrual migraine. About half of women affected by migraine have menstrually-related migraines (MRM); 3% to 12% have pure menstrual migraines (PMM).3 MRM and PMM are both characterized by the presence of symptoms in at least 2 to 3 consecutive cycles, with symptoms occurring from between 2 days before to 3 days after the onset of menstruation. However, in PMM, symptoms do not occur at any other time of the menstrual cycle; in MRM, symptoms can occur at other times of the cycle. PMM is more likely to respond to hormone therapy than is MRM.

Multiple studies in the United States, Europe, and Asia have noted that migraines related to menses typically last longer, are more severe, less likely to be associated with aura, and more likely to be recurrent and recalcitrant to treatment than non-menstrual migraines.1 TABLE 13 describes diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura.

Possible mechanisms of MRM and PMM. The etiology of migraine is not well understood and is likely multifactorial.4 Incidence of menstrual migraines is related to cyclic changes in female hormones—specifically, the decreasing levels of estrogen that typically happen the week before onset of menses.1 The mechanism is not yet clear, though it is thought that a decline in estrogen levels triggers a decline in serotonin levels, which may lead to cranial vasodilation and sensitization of the trigeminal nerve.5,6 Estrogen decline has also been linked to increased cranial nociception as well as decreased endogenous opioid activity. A study using positron emission tomography found increased activity of serotonergic neurons in migraineurs.7 The evidence that triptans and serotonin receptor agonists are effective in the treatment of migraine also supports the theory that serotonin neurohormonal signaling pathways play a critical role in the pathogenesis of migraines.7

Prevalence patterns point to the role of estrogen. The prevalence of migraines in women increases around puberty, peaks between ages 30 and 40, and decreases after natural menopause.6 Migraine prevalence increases during the first week postpartum, when levels of estrogen and progesterone decrease suddenly and significantly.1 Migraine frequency and intensity decrease in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and after menopause, when estrogen levels fluctuate significantly less.1 In the Women’s Health Initiative study, women who used hormone replacement therapy (HRT) had a 42% increased risk of migraines compared with women in the study who had never used HRT.8

The association of migraine with female hormones was further supported by a Dutch study of male-to-female transgender patients on estrogen therapy, who had a 26% incidence of migraine, equivalent to the 25% prevalence in natal female controls in this study, compared with just 7.5% in male controls.9 The association between migraine and estrogen withdrawal was investigated in studies performed more than 40 years ago, when women experiencing migraines around the time of menses were given intramuscular estradiol and experienced a delay in symptom onset.10

Abortive and prophylactic treatments: Factors that guide selection

In considering probable menstrual migraine, take a detailed history, review headache diaries if available to determine association of headaches with menses, and perform a thorough neurologic examination. If a diagnosis of menstrual migraine is established, discuss the benefits of different treatment options, both abortive and prophylactic.

For the patient with MRM, take into account frequency of symptoms, predictability of menstruation, medication costs, and comorbidities. Both triptans and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be effective treatments for MRM.11 Abortive therapy may be appropriate if a patient prefers to take medication intermittently, if her menses are unpredictable, or if she does not get migraine headaches with every menses. Mefenamic acid, sumatriptan, and rizatriptan have category B recommendations for abortive treatment for menstrual migraines (TABLE 211-16). (For the patient who has regular MRM but unpredictable menses, ovulation predictor kits can be used to help predict the onset of menses, although this would involve additional cost.)

For the patient who has predictable menses and regularly occurring menstrual migraine, some data show that a short-term prophylactic regimen with triptans started 2 to 3 days before the onset of menses and continued for 5 to 7 days total can reduce the incidence of menstrual migraine (TABLE 211-16). At least one high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed a significant reduction in the incidence of MRM when women were treated prophylactically with frovatriptan, a long-acting triptan with a half-life of approximately 26 hours. Participants received frovatriptan 2.5 mg once a day or twice a day or placebo in the perimenstrual period (day -2 to +3). The incidence of MRM was 52%, 41%, and 67%, respectively (P<.0001).11,17

Another RCT of fair quality examined the effect of naratriptan (half-life 6-8 hours) on the median number of menstrual migraines over 4 menstrual cycles. Women who received 1 mg of naratriptan BID for 2 to 3 days before menses had 2 MRM episodes over the 4 cycles compared with 4 MRM episodes in women who received placebo over the same time period (P<.05).11,18 A third RCT, also of fair quality, compared 2 different regimens of zolmitriptan (half-life 3 hours) with placebo and found that women who received 2.5 mg of zolmitriptan either BID or TID 2 to 3 days prior to menses had a reduction both in frequency of menstrual migraines and in the mean number of breakthrough headaches per menstrual cycle, as well as a reduction in the need for rescue medications.12,19 Triptans are contraindicated in women with a history of cardiac disease or uncontrolled hypertension. Also, triptans can be expensive, precluding their use for some patients.

Evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of NSAIDs as prophylaxis for MRM.11 NSAIDs may be contraindicated in women with a history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal bleeding. That said, if NSAIDs are not contraindicated, a trial may be reasonable given their low cost.

Data are sparse on the use of vitamins and supplements in treating and preventing PMM or MRM. In one very small double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 1991 (N=24, with efficacy data for 20), participants received a 2-week course of oral magnesium premenstrually. There was a statistically significant reduction in the number of days with headache per month (from 4.7±3.1 days to 2.4±2.2 days; P<.01) and in the total pain index (P<.03).20 A number of studies have demonstrated a correlation between hypomagnesemia and migraine headaches.5,21 The exact mechanism for this relationship is unclear.

Some recent evidence-based reviews have examined the efficacy of nutraceuticals such as magnesium, feverfew, butterbur, coenzyme Q10, and riboflavin on typical migraine, but it is not clear if these results are translatable to the treatment and prophylaxis of menstrual migraine.11,22 A multicenter, single-blind, RCT is underway to examine the efficacy of acupuncture as prophylaxis for MRM.23

Estrogen: Prescribing criteria are strict

Most studies examining the role of exogenous estrogen in reducing menstrual migraines have used topical estrogen (either in patch or gel formulations) in the perimenstrual window (TABLE 211-16). The topical estrogen route has been examined, in particular, as it is presumed to confer less risk of hypercoagulability by avoiding first-pass metabolism. However, there is conflicting evidence on this issue, in particular regarding premenopausal women.13,25 Additionally, many of the studies of estrogen supplementation show a trend toward increased headache once estrogen is discontinued, presumably due to estrogen withdrawal.10,24

That said, one study by MacGregor, et al demonstrates that the use of estradiol gel in the perimenstrual window leads to a 22% reduction in migraine days as well as less severe migrainous symptoms.26 This trend has been demonstrated in other studies examining estrogen supplementation. Of note, the estrogen studies generally are small, older, and of fair to poor quality.11 These studies have used higher doses of estrogen than are commonly used for contraception today because lower doses of estrogen seem not to have the same impact on migraine.5,24

As for COCs, with either normal or extended cycling, data are more mixed than for estrogen supplementation alone; equivalent numbers of women experience improvement, no change, or worsening of their headache pattern. Many women have continuing or worsening migraines in the hormone-free week, and thus most studies have examined the use of extended cycling COCs.5 Sulak, et al demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in headache frequency using extended-cycling COCs, though they did not examine MRM in particular.27 The efficacy of extended-cycling COCs for reduction of MRM was confirmed by Coffee and colleagues with a small but statistically significant decrease in daily headache scores.28

Adverse effects. All estrogen therapies pose the risk of adverse effects (deep vein thrombosis, hypertension, breast tenderness, nausea, etc). Additionally, estrogen supplementation may actually trigger migraines in some women if, when it is discontinued, the blood estrogen level does not remain above a threshold concentration.5,10,24 Estrogen may also trigger migraine in previously headache-free women and may convert migraine without aura into migraine with aura. In either case, therapy should be stopped.5,24

There is promising evidence from 2 small RCTs and one observational trial that progestin-only contraceptive pills (POP) may reduce the frequency and severity of menstrual migraines (TABLE 211-16). More prospective data are needed to confirm this reduction, as there have not been specific studies examining other progesterone-only preparations to prevent menstrual migraines.

Risk of ischemic stroke. Unfortunately, there are population data showing that second-generation and, to a smaller degree, third-generation progestins, which include the desogestrel used in the above studies, may increase the risk of ischemic stroke. This is a particular concern in women who experience migraine.29 Second-generation progestins include levonorgestrel, which is in the levonorgestrel IUD; however, there is no direct evidence for increased ischemic stroke in this particular preparation, and the circulating plasma levels are low. Etonorgestrel, the active ingredient in the contraceptive implant, is a third-generation progestin, though there is no direct evidence of increased ischemic stroke with use of the etonorgestrel implant.

There is a 2- to 4-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke in women who experience migraine.1,5,30 As stated above, this risk may be further increased by some progesterone formulations. But there is also a demonstrable increase in ischemic stroke risk with the use of estrogen, particularly at the higher concentrations that have been shown to prevent MRM.31,32 The overall incidence of ischemic stroke in menstrual-age women is low, which has limited the number of studies with enough power to quantify the absolute increased risk of stroke in conjunction with estrogen use. Nevertheless, exogenous estrogen is thought to increase the risk of ischemic stroke an additional 2- to 4-fold.1,5,29,30,32-34

Women who experience aura. MRM, as it is defined, typically excludes women who experience aura; however, the number of women who experience aura with migraine either in proximity to their menses or throughout the month has not been well documented. The risk of ischemic stroke is higher for women who experience migraine with aura than those with migraine alone, possibly because aura is associated with reduced regional vascular flow leading to hypoperfusion, which sets the stage for a possible ischemic event.4,5,35 The risk of ischemic stroke is amplified further for women who are over 35, who smoke, or who have additional vascular risk factors (eg, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or known vascular or cardiac disease).1,5,34 This array of evidence serves as the basis for the US Medical Eligibility Criteria (USMEC) recommendations36 for hormonal contraceptive use, in particular the absolute contraindication for estrogen use in women who experience migraine with aura (TABLE 336-38).

CASE › Given Mary’s experience of aura with migraine, you talk with her at length about the risk of ischemic stroke and the USMEC recommendation that she absolutely should not be taking COCs. You suggest a progestin-only method of contraception such as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a progestin intrauterine device, or a hormonal implant, which may suppress ovulation and decrease her headaches. You discuss that while some women may have headaches with these progestin-only methods, stroke risk is significantly reduced. You also suggest a trial of prophylactic triptans as another possible option.

She says she understands the increased risk of stroke but is still unwilling to try anything else right now due to worries about her quality of life. You decide jointly to refill COCs for 3 months, and you document the shared decision process in the chart. After advising the patient that you will not continue to prescribe COCs for an extended period of time, you also schedule a follow-up appointment to further discuss risks and benefits of migraine treatment and means of reducing other risk factors for stroke.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, University of Wisconsin, Department of Family Medicine, 1100 Delaplaine Ct, Madison, WI 53715; sbschrag@wisc.edu.

› Consider recommending that patients with menstrual migraines try using prophylactic triptans 2 days before the onset of menses. B

› Advise against estrogen-containing contraception for women who have menstrual migraines with aura, who smoke, or are over 35, due to the increased risk of stroke (absolute contraindication). A

› Consider estrogen-containing contraception if the benefits outweigh the risks for women with migraines who are under 35 and do not have aura (relative contraindication). A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Mary, a 34-year-old woman, is a new patient to your practice after moving to the area for a job. She has a history of migraine headaches triggered by her menstrual periods. She has been taking combined oral contraceptives (COCs) since she was 17, with a few years off when she had 2 children. Her migraines improved when she was pregnant, but worsened postpartum with each of her daughters to a point where she had to stop breastfeeding at 4 months to go back on the pills.

On the COCs, she gets one or 2 mild-to-moderate headaches a month. She uses sumatriptan for abortive treatment with good relief. She has not missed work in the past 4 years because of her migraines. During the 6 months she was off COCs when trying to get pregnant, she routinely missed 2 to 3 workdays per month due to migraines. She knows when she is going to get a headache because she sees flashing lights in her left visual field. She has no other neurologic symptoms with the headaches, and the character of the headaches has not changed. She is a non-smoker, has normal blood pressure and lipid levels, and no other vascular risk factors.

You review her history and talk to her about the risk of stroke with migraines and with COCs. She is almost 35 years of age and you recommend stopping the COCs due to the risk. She feels strongly that she wants to continue taking the COCs, saying her quality of life is poor when she is off the pills. What should you do?

Migraine headaches are 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women than in men,1 with a lifetime risk of 43% vs 18%, respectively.2 Women account for about 80% of the $1 billion spent each year in the United States in medical expenses and lost work productivity related to migraines.1,2

Clinical patterns suggestive of menstrual migraine. About half of women affected by migraine have menstrually-related migraines (MRM); 3% to 12% have pure menstrual migraines (PMM).3 MRM and PMM are both characterized by the presence of symptoms in at least 2 to 3 consecutive cycles, with symptoms occurring from between 2 days before to 3 days after the onset of menstruation. However, in PMM, symptoms do not occur at any other time of the menstrual cycle; in MRM, symptoms can occur at other times of the cycle. PMM is more likely to respond to hormone therapy than is MRM.

Multiple studies in the United States, Europe, and Asia have noted that migraines related to menses typically last longer, are more severe, less likely to be associated with aura, and more likely to be recurrent and recalcitrant to treatment than non-menstrual migraines.1 TABLE 13 describes diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura.

Possible mechanisms of MRM and PMM. The etiology of migraine is not well understood and is likely multifactorial.4 Incidence of menstrual migraines is related to cyclic changes in female hormones—specifically, the decreasing levels of estrogen that typically happen the week before onset of menses.1 The mechanism is not yet clear, though it is thought that a decline in estrogen levels triggers a decline in serotonin levels, which may lead to cranial vasodilation and sensitization of the trigeminal nerve.5,6 Estrogen decline has also been linked to increased cranial nociception as well as decreased endogenous opioid activity. A study using positron emission tomography found increased activity of serotonergic neurons in migraineurs.7 The evidence that triptans and serotonin receptor agonists are effective in the treatment of migraine also supports the theory that serotonin neurohormonal signaling pathways play a critical role in the pathogenesis of migraines.7

Prevalence patterns point to the role of estrogen. The prevalence of migraines in women increases around puberty, peaks between ages 30 and 40, and decreases after natural menopause.6 Migraine prevalence increases during the first week postpartum, when levels of estrogen and progesterone decrease suddenly and significantly.1 Migraine frequency and intensity decrease in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and after menopause, when estrogen levels fluctuate significantly less.1 In the Women’s Health Initiative study, women who used hormone replacement therapy (HRT) had a 42% increased risk of migraines compared with women in the study who had never used HRT.8

The association of migraine with female hormones was further supported by a Dutch study of male-to-female transgender patients on estrogen therapy, who had a 26% incidence of migraine, equivalent to the 25% prevalence in natal female controls in this study, compared with just 7.5% in male controls.9 The association between migraine and estrogen withdrawal was investigated in studies performed more than 40 years ago, when women experiencing migraines around the time of menses were given intramuscular estradiol and experienced a delay in symptom onset.10

Abortive and prophylactic treatments: Factors that guide selection

In considering probable menstrual migraine, take a detailed history, review headache diaries if available to determine association of headaches with menses, and perform a thorough neurologic examination. If a diagnosis of menstrual migraine is established, discuss the benefits of different treatment options, both abortive and prophylactic.

For the patient with MRM, take into account frequency of symptoms, predictability of menstruation, medication costs, and comorbidities. Both triptans and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be effective treatments for MRM.11 Abortive therapy may be appropriate if a patient prefers to take medication intermittently, if her menses are unpredictable, or if she does not get migraine headaches with every menses. Mefenamic acid, sumatriptan, and rizatriptan have category B recommendations for abortive treatment for menstrual migraines (TABLE 211-16). (For the patient who has regular MRM but unpredictable menses, ovulation predictor kits can be used to help predict the onset of menses, although this would involve additional cost.)

For the patient who has predictable menses and regularly occurring menstrual migraine, some data show that a short-term prophylactic regimen with triptans started 2 to 3 days before the onset of menses and continued for 5 to 7 days total can reduce the incidence of menstrual migraine (TABLE 211-16). At least one high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed a significant reduction in the incidence of MRM when women were treated prophylactically with frovatriptan, a long-acting triptan with a half-life of approximately 26 hours. Participants received frovatriptan 2.5 mg once a day or twice a day or placebo in the perimenstrual period (day -2 to +3). The incidence of MRM was 52%, 41%, and 67%, respectively (P<.0001).11,17

Another RCT of fair quality examined the effect of naratriptan (half-life 6-8 hours) on the median number of menstrual migraines over 4 menstrual cycles. Women who received 1 mg of naratriptan BID for 2 to 3 days before menses had 2 MRM episodes over the 4 cycles compared with 4 MRM episodes in women who received placebo over the same time period (P<.05).11,18 A third RCT, also of fair quality, compared 2 different regimens of zolmitriptan (half-life 3 hours) with placebo and found that women who received 2.5 mg of zolmitriptan either BID or TID 2 to 3 days prior to menses had a reduction both in frequency of menstrual migraines and in the mean number of breakthrough headaches per menstrual cycle, as well as a reduction in the need for rescue medications.12,19 Triptans are contraindicated in women with a history of cardiac disease or uncontrolled hypertension. Also, triptans can be expensive, precluding their use for some patients.

Evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of NSAIDs as prophylaxis for MRM.11 NSAIDs may be contraindicated in women with a history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal bleeding. That said, if NSAIDs are not contraindicated, a trial may be reasonable given their low cost.

Data are sparse on the use of vitamins and supplements in treating and preventing PMM or MRM. In one very small double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 1991 (N=24, with efficacy data for 20), participants received a 2-week course of oral magnesium premenstrually. There was a statistically significant reduction in the number of days with headache per month (from 4.7±3.1 days to 2.4±2.2 days; P<.01) and in the total pain index (P<.03).20 A number of studies have demonstrated a correlation between hypomagnesemia and migraine headaches.5,21 The exact mechanism for this relationship is unclear.

Some recent evidence-based reviews have examined the efficacy of nutraceuticals such as magnesium, feverfew, butterbur, coenzyme Q10, and riboflavin on typical migraine, but it is not clear if these results are translatable to the treatment and prophylaxis of menstrual migraine.11,22 A multicenter, single-blind, RCT is underway to examine the efficacy of acupuncture as prophylaxis for MRM.23

Estrogen: Prescribing criteria are strict

Most studies examining the role of exogenous estrogen in reducing menstrual migraines have used topical estrogen (either in patch or gel formulations) in the perimenstrual window (TABLE 211-16). The topical estrogen route has been examined, in particular, as it is presumed to confer less risk of hypercoagulability by avoiding first-pass metabolism. However, there is conflicting evidence on this issue, in particular regarding premenopausal women.13,25 Additionally, many of the studies of estrogen supplementation show a trend toward increased headache once estrogen is discontinued, presumably due to estrogen withdrawal.10,24

That said, one study by MacGregor, et al demonstrates that the use of estradiol gel in the perimenstrual window leads to a 22% reduction in migraine days as well as less severe migrainous symptoms.26 This trend has been demonstrated in other studies examining estrogen supplementation. Of note, the estrogen studies generally are small, older, and of fair to poor quality.11 These studies have used higher doses of estrogen than are commonly used for contraception today because lower doses of estrogen seem not to have the same impact on migraine.5,24

As for COCs, with either normal or extended cycling, data are more mixed than for estrogen supplementation alone; equivalent numbers of women experience improvement, no change, or worsening of their headache pattern. Many women have continuing or worsening migraines in the hormone-free week, and thus most studies have examined the use of extended cycling COCs.5 Sulak, et al demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in headache frequency using extended-cycling COCs, though they did not examine MRM in particular.27 The efficacy of extended-cycling COCs for reduction of MRM was confirmed by Coffee and colleagues with a small but statistically significant decrease in daily headache scores.28

Adverse effects. All estrogen therapies pose the risk of adverse effects (deep vein thrombosis, hypertension, breast tenderness, nausea, etc). Additionally, estrogen supplementation may actually trigger migraines in some women if, when it is discontinued, the blood estrogen level does not remain above a threshold concentration.5,10,24 Estrogen may also trigger migraine in previously headache-free women and may convert migraine without aura into migraine with aura. In either case, therapy should be stopped.5,24

There is promising evidence from 2 small RCTs and one observational trial that progestin-only contraceptive pills (POP) may reduce the frequency and severity of menstrual migraines (TABLE 211-16). More prospective data are needed to confirm this reduction, as there have not been specific studies examining other progesterone-only preparations to prevent menstrual migraines.

Risk of ischemic stroke. Unfortunately, there are population data showing that second-generation and, to a smaller degree, third-generation progestins, which include the desogestrel used in the above studies, may increase the risk of ischemic stroke. This is a particular concern in women who experience migraine.29 Second-generation progestins include levonorgestrel, which is in the levonorgestrel IUD; however, there is no direct evidence for increased ischemic stroke in this particular preparation, and the circulating plasma levels are low. Etonorgestrel, the active ingredient in the contraceptive implant, is a third-generation progestin, though there is no direct evidence of increased ischemic stroke with use of the etonorgestrel implant.

There is a 2- to 4-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke in women who experience migraine.1,5,30 As stated above, this risk may be further increased by some progesterone formulations. But there is also a demonstrable increase in ischemic stroke risk with the use of estrogen, particularly at the higher concentrations that have been shown to prevent MRM.31,32 The overall incidence of ischemic stroke in menstrual-age women is low, which has limited the number of studies with enough power to quantify the absolute increased risk of stroke in conjunction with estrogen use. Nevertheless, exogenous estrogen is thought to increase the risk of ischemic stroke an additional 2- to 4-fold.1,5,29,30,32-34

Women who experience aura. MRM, as it is defined, typically excludes women who experience aura; however, the number of women who experience aura with migraine either in proximity to their menses or throughout the month has not been well documented. The risk of ischemic stroke is higher for women who experience migraine with aura than those with migraine alone, possibly because aura is associated with reduced regional vascular flow leading to hypoperfusion, which sets the stage for a possible ischemic event.4,5,35 The risk of ischemic stroke is amplified further for women who are over 35, who smoke, or who have additional vascular risk factors (eg, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or known vascular or cardiac disease).1,5,34 This array of evidence serves as the basis for the US Medical Eligibility Criteria (USMEC) recommendations36 for hormonal contraceptive use, in particular the absolute contraindication for estrogen use in women who experience migraine with aura (TABLE 336-38).

CASE › Given Mary’s experience of aura with migraine, you talk with her at length about the risk of ischemic stroke and the USMEC recommendation that she absolutely should not be taking COCs. You suggest a progestin-only method of contraception such as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a progestin intrauterine device, or a hormonal implant, which may suppress ovulation and decrease her headaches. You discuss that while some women may have headaches with these progestin-only methods, stroke risk is significantly reduced. You also suggest a trial of prophylactic triptans as another possible option.

She says she understands the increased risk of stroke but is still unwilling to try anything else right now due to worries about her quality of life. You decide jointly to refill COCs for 3 months, and you document the shared decision process in the chart. After advising the patient that you will not continue to prescribe COCs for an extended period of time, you also schedule a follow-up appointment to further discuss risks and benefits of migraine treatment and means of reducing other risk factors for stroke.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, University of Wisconsin, Department of Family Medicine, 1100 Delaplaine Ct, Madison, WI 53715; sbschrag@wisc.edu.

1. MacGregor EA, Rosenberg JD, Kurth T. Sex-related differences in epidemiological and clinic-based headache studies. Headache. 2011;51:843-859.

2. Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed ML, et al. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:1170-1178.

3. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd ed. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808.

4. Garza I, Swanson JW, Cheshire WP Jr, et al. Headache and other craniofacial pain. In: Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J, et al, eds. Bradley’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1703-1744.

5. Martin VT, Behbehani M. Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis – part 2. Headache. 2006;46:365-386.

6. Brandes JL. The influence of estrogen on migraine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006; 295:1824-1830.

7. Loder EW. Menstrual migraine: pathophysiology, diagnosis and impact. Headache. 2006;46 (Suppl 2):S55-S60.

8. Misakian AL, Langer RD, Bensenor IM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and migraine headache. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2003;12:1027-1036.

9. Pringsheim T, Gooren L. Migraine prevalence in male to female transsexuals on hormone therapy. Neurology. 2004;63:593-594.

10. Somerville BW. The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 1972;22:355-365.

11. Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D. Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache: evidence-based review. Neurology. 2008;70:1555-1563.

12. Hu Y, Guan X, Fan L, et al. Triptans in prevention of menstrual migraine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Headache Pain. 2013;14:7.

13. Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:1227-1231.

14. Merki-Feld GS, Imthurn B, Langner R, et al. Headache frequency and intensity in female migraineurs using desogestrel-only contraception: a retrospective pilot diary study. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:340-346.

15.

16. Morotti M, Remorgida V, Venturini PL, et al. Progestin-only contraception compared with extended combined oral contraceptive in women with migraine without aura: a retrospective pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;183:178-182.

17. Silberstein SD, Elkind AH, Schreiber C, et al. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 2004;63:261-269.

18. Newman L, Mannix LK, Landy S, et al. Naratriptan as short-term prophylaxis of menstrually associated migraine: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2001;41:248-256.

19. Tuchman MM, Hee A, Emeribe U, et al. Oral zolmitriptan in the short-term prevention of menstrual migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:877-886.

20. Facchinetti F, Sances G, Borella P, et al. Magnesium prophylaxis of menstrual migraine: effects on intracellular magnesium. Headache. 1991;31:298-301.

21. Teigen L, Boes CJ. An evidence-based review of oral magnesium supplementation in the preventive treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia. 2014;35:912-922.

22. Taylor FR. Nutraceuticals and headache: the biological basis. Headache. 2011;51:484-501.

23. Zhang XZ, Zhang L, Guo J, et al. Acupuncture as prophylaxis for menstrual-related migraine: study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:374.

24. MacGregor EA. Oestrogen and attacks of migraine with and without aura. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:354-361.

25. Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, et al. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive system users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:339-346.

26. MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, et al. Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology. 2006;67:2159-2163.

27. Sulak P, Willis S, Kuehl T, et al. Headaches and oral contraceptives: impact of eliminating the standard 7-day placebo interval. Headache. 2007;47:27-37.

28. Coffee AL, Sulak PJ, Hill AJ, et al. Extended cycle combined oral contraceptives and prophylactic frovatriptan during the hormone-free interval in women with menstrual-related migraines. J Womens Health. 2014;23:310-317.

29. Lidegaard Ø, Kreiner S. Contraceptives and cerebral thrombosis: a five-year national case-control study. Contraception. 2002;65:197-205.

30. Bousser MG. Estrogen, migraine, and stroke. Stroke. 2004;35(Suppl 1):2652-2656.

31. Gillum LA, Mamidipudi SK, Johnston SC. Ischemic stroke risk with oral contraceptives: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:72-78.

32. Donaghy M, Chang CL, Poulter N. Duration, frequency, recency, and type of migraine and the risk of ischaemic stroke in women of childbearing age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:747-750.

33. Sacco S, Ricci S, Degan D. Migraine in women: the role of hormones and their impact on vascular diseases. J Headache Pain. 2012;12:177-189.

34. Merikangas KR, Fenton BT, Cheng SH, et al. Association between migraine and stroke in a large-scale epidemiological study of the United States. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:362-368.

35. MacClellan LR, Giles W, Cole J, et al. Probable migraine with visual aura and risk of ischemic stroke: the stroke prevention in young women study. Stroke. 2007;38:2438-2445.

36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep

37. Chang CL, Donaghy M, Poulter N. Migraine and stroke in young women: case-control study. The World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. BMJ. 1999;318:13-18.

38. Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglésias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischaemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310:830-833.

1. MacGregor EA, Rosenberg JD, Kurth T. Sex-related differences in epidemiological and clinic-based headache studies. Headache. 2011;51:843-859.

2. Stewart WF, Wood C, Reed ML, et al. Cumulative lifetime migraine incidence in women and men. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:1170-1178.

3. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd ed. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808.

4. Garza I, Swanson JW, Cheshire WP Jr, et al. Headache and other craniofacial pain. In: Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J, et al, eds. Bradley’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1703-1744.

5. Martin VT, Behbehani M. Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis – part 2. Headache. 2006;46:365-386.

6. Brandes JL. The influence of estrogen on migraine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006; 295:1824-1830.

7. Loder EW. Menstrual migraine: pathophysiology, diagnosis and impact. Headache. 2006;46 (Suppl 2):S55-S60.

8. Misakian AL, Langer RD, Bensenor IM, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and migraine headache. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2003;12:1027-1036.

9. Pringsheim T, Gooren L. Migraine prevalence in male to female transsexuals on hormone therapy. Neurology. 2004;63:593-594.

10. Somerville BW. The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 1972;22:355-365.

11. Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D. Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache: evidence-based review. Neurology. 2008;70:1555-1563.

12. Hu Y, Guan X, Fan L, et al. Triptans in prevention of menstrual migraine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Headache Pain. 2013;14:7.

13. Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:1227-1231.

14. Merki-Feld GS, Imthurn B, Langner R, et al. Headache frequency and intensity in female migraineurs using desogestrel-only contraception: a retrospective pilot diary study. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:340-346.

15.

16. Morotti M, Remorgida V, Venturini PL, et al. Progestin-only contraception compared with extended combined oral contraceptive in women with migraine without aura: a retrospective pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;183:178-182.

17. Silberstein SD, Elkind AH, Schreiber C, et al. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 2004;63:261-269.

18. Newman L, Mannix LK, Landy S, et al. Naratriptan as short-term prophylaxis of menstrually associated migraine: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2001;41:248-256.

19. Tuchman MM, Hee A, Emeribe U, et al. Oral zolmitriptan in the short-term prevention of menstrual migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:877-886.

20. Facchinetti F, Sances G, Borella P, et al. Magnesium prophylaxis of menstrual migraine: effects on intracellular magnesium. Headache. 1991;31:298-301.

21. Teigen L, Boes CJ. An evidence-based review of oral magnesium supplementation in the preventive treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia. 2014;35:912-922.

22. Taylor FR. Nutraceuticals and headache: the biological basis. Headache. 2011;51:484-501.

23. Zhang XZ, Zhang L, Guo J, et al. Acupuncture as prophylaxis for menstrual-related migraine: study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:374.

24. MacGregor EA. Oestrogen and attacks of migraine with and without aura. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:354-361.

25. Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, et al. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive system users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:339-346.

26. MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, et al. Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology. 2006;67:2159-2163.

27. Sulak P, Willis S, Kuehl T, et al. Headaches and oral contraceptives: impact of eliminating the standard 7-day placebo interval. Headache. 2007;47:27-37.

28. Coffee AL, Sulak PJ, Hill AJ, et al. Extended cycle combined oral contraceptives and prophylactic frovatriptan during the hormone-free interval in women with menstrual-related migraines. J Womens Health. 2014;23:310-317.

29. Lidegaard Ø, Kreiner S. Contraceptives and cerebral thrombosis: a five-year national case-control study. Contraception. 2002;65:197-205.

30. Bousser MG. Estrogen, migraine, and stroke. Stroke. 2004;35(Suppl 1):2652-2656.

31. Gillum LA, Mamidipudi SK, Johnston SC. Ischemic stroke risk with oral contraceptives: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:72-78.

32. Donaghy M, Chang CL, Poulter N. Duration, frequency, recency, and type of migraine and the risk of ischaemic stroke in women of childbearing age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:747-750.

33. Sacco S, Ricci S, Degan D. Migraine in women: the role of hormones and their impact on vascular diseases. J Headache Pain. 2012;12:177-189.

34. Merikangas KR, Fenton BT, Cheng SH, et al. Association between migraine and stroke in a large-scale epidemiological study of the United States. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:362-368.

35. MacClellan LR, Giles W, Cole J, et al. Probable migraine with visual aura and risk of ischemic stroke: the stroke prevention in young women study. Stroke. 2007;38:2438-2445.

36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep

37. Chang CL, Donaghy M, Poulter N. Migraine and stroke in young women: case-control study. The World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. BMJ. 1999;318:13-18.

38. Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglésias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischaemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310:830-833.

Emergency contraception: An underutilized resource

• Offer emergency contraception (EC) to any woman who reports contraceptive failure or unprotected intercourse within the last 5 days; no clinical exam is necessary. B

• Prescribe a progestin-only EC or ulipristal acetate, both of which are more effective and have fewer adverse effects than an estrogen-progestin combination. A

• Consider giving sexually active teens <17 years an advance prescription for EC, as it is not available over the counter to this age group. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The average American woman will spend more than 30 years of her life trying to prevent pregnancy—not always successfully. Each year, half of the approximately 6 million pregnancies in the United States are unintended.1 Emergency contraception (EC) gives a woman a second chance to prevent pregnancy after a contraceptive failure or unprotected sex. But all too often, it isn’t offered and she doesn’t request it.

Lack of knowledge about EC continues to be a barrier to its use. Some women have heard about the “morning after pill,” but may not know that EC can be effective for up to 5 days after intercourse—or even that it’s available in this country.2 Others are unaware that it is possible to prevent pregnancy after intercourse,2 and mistakenly believe that EC drugs are abortifacients. In fact, they work primarily by interfering with ovulation and have not been found to prevent implantation or to disrupt an existing pregnancy.3-5

Providers also contribute to the limited use of EC, often because they’re unfamiliar with the options or uncomfortable discussing them with patients, particularly sexually active teens.2

This update can help you clear up misconceptions about EC with your patients. It also provides evidence-based information about the various types of EC, a review of issues affecting accessibility, and a telephone triage protocol to guide your response to women seeking postcoital contraception.

EC today: Plan B and beyond

Hormonal EC was first studied in the 1920s, when researchers found that estrogenic ovarian extracts interfered with pregnancy in animals. The first regimen was a high-dose estrogen-only formulation. In 1974, a combined estrogen-progestin replaced it. Known as the Yuzpe method for the physician who discovered it,6 this regimen used a widely available brand of combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive pills. The standard dose consisted of 100 mcg ethinyl estradiol (EE) and 0.5 mg levonorgestrel (LNG) taken 12 hours apart.2,7

Although the Yuzpe method is still in use, progestin-only EC—Plan B as well as generic (Next Choice) and single-dose (Plan B One-Step) LNG formulations—has become the standard of care because it has greater efficacy and fewer adverse effects.2 There are 2 additional options: the copper intrauterine device (IUD), which is highly effective both as EC and as a long-term contraceptive,6 and ulipristal acetate (UPA), which received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2010. This second-generation antiprogestin, sold under the brand name Ella, is well tolerated and highly effective.8

EC efficacy: What the evidence shows

EC is most likely to work when used within 24 hours, but remains effective—albeit to varying degrees—for up to 120 hours (TABLE).2,5,8,9 Thus, which EC is best for a particular patient depends, in part, on timing.

TABLE

Emergency contraception: Comparing methods*2,5,8,9

| EC method | Dose and timing | Benefits | Adverse effects/ drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen-progestin OCs | 100 mcg EE and 0.5 mg LNG, taken 12 h apart First dose within 72 h | Easily accessible and widely available; patient may use OCs she already has at home | Higher rates of adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, headache; less effective than other methods |

| Progestin-only (Plan B, Next Choice, others) | 1.5 mg LNG within 72 h (available in divided doses or in a single tablet; 2 tablets may be taken as a single dose) | Available OTC for patients ≥17 y; more effective and fewer adverse effects than estrogen-progestin Convenience of single dose | Prescription required for patients <17 y Approved for use within 72 h; effectiveness diminishes thereafter |

| UPA (Ella) | 30 mg UPA, taken ≤120 h† | More effective than LNG; fewer adverse effects than estrogen-progestin Efficacy remains high ≤5 days Convenience of single dose | Prescription required; not available at all pharmacies Not studied in breastfeeding‡ |

| Copper IUD | Insert ≤120 h | Extremely effective Provides immediate, long-term contraception | Insertion requires staff training; higher cost than oral EC |

| EC, emergency contraception; EE, ethinyl estradiol; IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel; OCs, oral contraceptives; OTC, over the counter; UPA, ulipristal acetate. *Low doses of mifepristone (<25-50 mg)—approved as an abortifacient in much larger doses—may also be used as EC. †Dosage should be repeated if vomiting occurs within 3 hours. ‡Advise patients to avoid breastfeeding for 36 hours | |||

Copper IUDs have the highest success rate: Studies have found the copper IUD to be >99% effective in preventing pregnancy when inserted within 5 days of unprotected intercourse.9,10 The copper ions it contains have a toxic effect on sperm, and impair the potential for fertilization; the device may also make the endometrium inhospitable to implantation.9,10

A just-published systematic review of 42 studies in 6 countries over a period of more than 30 years yielded similar results: Among more than 7000 women who had the IUDs inserted after unprotected intercourse, the pregnancy rate was 0.09%.11

But an IUD is appropriate only for women who want long-term contraception and would otherwise qualify for IUD insertion. By comparison, hormonal EC is not as effective and generally works best when used within a shorter time frame.

Progestin alone vs estrogen-progestin combo. To compare hormonal contraception, many researchers use a “prevented fraction”—an estimated percentage of pregnancies averted by treatment. A large World Health Organization-sponsored study found that the efficacy of progestin-only EC is superior to that of the estrogen-progestin combination, with prevented fractions of 85% and 57%, respectively. The progestin-only EC was also associated with significantly fewer adverse effects.12

In more recent studies, the prevented fraction for progestin-only EC has been found to range from 60% to 94%, while a meta-analysis of studies assessing estrogen-progestin EC r evealed a prevented fraction of ≥74%.2

Although there is evidence suggesting that progestin-only EC may work for up to 5 days,13,14 it has FDA approval only for use within 72 hours of intercourse.13 A time-sensitive analysis showed that when it was used within 12 hours of intercourse, the pregnancy rate was 0.5%. The rate increased steadily to 4.1% when the progestin-based EC was taken 61 to 72 hours after intercourse, and rose by an additional 50% after an additional 12-hour delay.15

Hormonal EC is only effective before ovulation occurs. Once luteinizing hormone (LH) starts to rise, it is ineffective. However, the likelihood of pregnancy drops precipitously after ovulation, and there is no risk of pregnancy in the luteal phase, with or without EC.

One pill or 2? Both Plan B and the generic Next Choice are sold as 2-dose regimens, with one 0.75-mg tablet taken within 72 hours and the second taken 12 hours later. Plan B One-Step, which consists of a single 1.5-mg tablet, is clinically equivalent to the 2-dose formula,16 but is more convenient and may improve adherence. Notably, though, one large randomized controlled trial (RCT) in China found that the 2-pill regimen was significantly more effective in preventing pregnancy in women who had further acts of unprotected intercourse after treatment.17

UPA has a 5-day window. UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse and has been found to be more effective than progestin-only EC, especially when used on Day 4 or 5 (72-120 hours).8 Adverse effects are mild to moderate, similar to those of LNG, and may include headache, abdominal pain, nausea, dysmenorrhea, fatigue, and dizziness.8

The medication binds to progesterone receptors, acting as an antagonist as well as a partial agonist. The mechanism of action depends on the phase of the woman’s cycle. Taken during the midfollicular phase, UPA inhibits follicle development.18 When used in the advanced follicular phase, just prior to ovulation, it delays LH peak and postpones ovulation.19

In one small study in which women were randomized to either UPA or placebo, researchers found that the drug delayed ovulation for ≥5 days in about 60% of those who took it; in comparison, ovulation occurred by Day 5 in every woman in the placebo group.19

How accessible is EC?

EC has a tumultuous history in the United States,20 and accessibility depends on a variety of factors—age among them.

Plan B, for instance, is subject to a 2-tier system. It was approved in 1999 as a prescription-only product and has been available over the counter (OTC) to women 17 years and older since 2009. Younger women can get it only by prescription.21

Nonetheless, Plan B made the news again last year, when US Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius overruled an FDA decision to give teens younger than 17 OTC access.22 Thus, the age restriction remains in place, although there is no medical evidence to support it.23 Other forms of EC, including UPA, are available to all women only by prescription.

Accessibility of EC also may vary from one part of the country to another. Some states have enacted laws with conscience clauses that allow pharmacists to refuse to dispense EC. Others have worked to increase access by authorizing pharmacists to initiate and dispense EC on their own, provided they work in collaboration with a doctor or other licensed prescriber. As of 2011, 9 states—Alaska, California, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Vermont, and Washington—had such agreements in place.24

Cost is another potential barrier. The cost of oral EC varies from about $10 to $70, plus the cost of a doctor visit for a teen who needs a prescription. Obtaining the copper IUD without insurance coverage would cost hundreds of dollars, to cover the price of insertion as well as the device.5

Increasing access: What you can do

In view of the barriers that adolescents face in obtaining EC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics, among other organizations, recommend that physicians give advance prescriptions to teens under the age of 17. 2,25

But how likely are they to actually buy the medication and use it on an emergency basis?

A 2007 Cochrane review found that giving women advance prescriptions for EC did not reduce pregnancy or abortion rates.26 Other studies have found that EC use is highest among women with the lowest risk of pregnancy—those who are already using contraception and are less likely to have unprotected intercourse. Those at the highest risk for unintended pregnancy were found to be less likely to use EC after every episode of unprotected intercourse.23,26 One RCT demonstrated that rates of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection were not significantly increased by advance provision of EC, leading the researchers to conclude that it was therefore unreasonable to restrict access.27