User login

Primary Cutaneous Apocrine Carcinoma Arising Within a Nevus Sebaceus

Nevus sebaceus (NS) is a benign hair follicle neoplasm present in approximately 1.3% of the population, typically involving the scalp, neck, or face.1 These lesions usually are present at birth or identified soon after, during the first year. They present as a yellowish hairless patch or plaque but can develop a more papillomatous appearance, especially after puberty. Historically, the concern with NS was its tendency to transform into basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which prompted surgical excision of the lesion during childhood. This theory has been discounted more recently, as further research has suggested that what was once thought to be BCC may have been confused with the similarly appearing trichoblastoma; however, malignant transformation of NS does still occur, with BCC still being the most common.2 We present the case of a long-standing NS with rare transformation to apocrine carcinoma.

Case Report

A 76-year-old woman presented with several new lesions within a previously diagnosed NS. She reported having the large plaque for as long as she could recall but reported that several new growths developed within the plaque over the last 2 months, slowly increasing in size. She reported a prior biopsy within the growth several years prior, which she described as an irritated seborrheic keratosis.

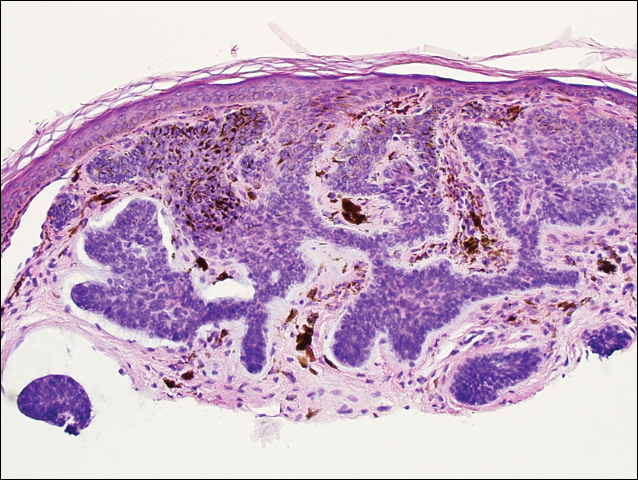

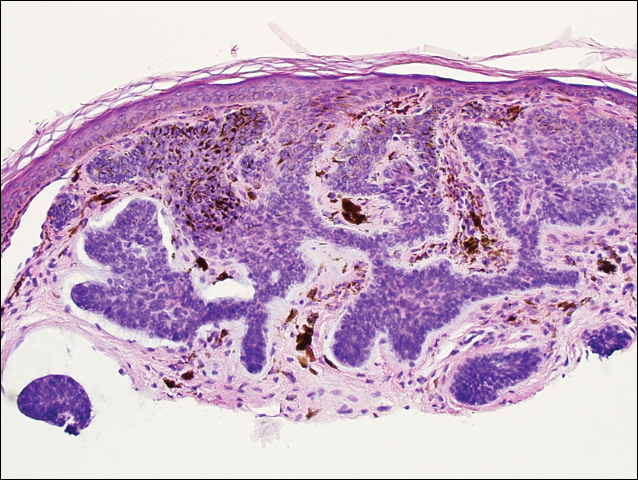

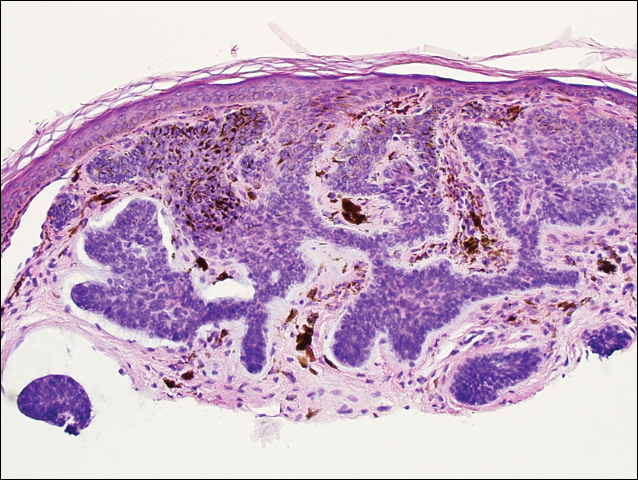

Physical examination demonstrated 4 distinct lesions within the flesh-colored, verrucous plaque located on the left side of the temporal scalp (Figure 1). The first lesion was a 2.5-cm pearly, pink, exophytic tumor (labeled as A in Figure 1). The next 2 lesions were brown, pedunculated, verrucous papules (labeled as B and C in Figure 1). The last lesion was a purple papule (labeled as D in Figure 1). Four shave biopsies were performed for histologic analysis of the lesions. Lesions B, C, and D were consistent with trichoblastomas, as pathology showed basaloid epithelial tumors that displayed primitive follicular structures, areas of stromal induction, and some pigmentation. Lesion A, originally thought to be suspicious for a BCC, was determined to be a primary cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma upon pathologic review. The pathology showed a dermal tumor displaying solid and tubular areas with decapitation secretion. Nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses were present (Figure 2), and staining for carcinoembryonic antigen was positive (Figure 3). Immunoreactivity with epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 was noted as well as focal positivity for mammaglobin. Primary apocrine carcinoma was favored over metastatic carcinoma due to the location of the lesion within an NS along with a negative history of internal malignancy. Dermatopathology recommended complete removal of all lesions within the NS.

Upon discussing biopsy results and recommendations with our patient, she agreed to undergo excision with intraoperative pathology by a plastic surgeon within our practice to ensure clear margins. The surgical defect following excision was sizeable and closed utilizing a rhomboid flap, full-thickness skin graft, and a split-thickness skin graft. At surgical follow-up, she was doing well and there have been no signs of local recurrence for 10 months since excision.

Comment

Presentation

Nevus sebaceus is the most common adnexal tumor and is classified as a benign congenital hair follicle tumor that is located most commonly on the scalp but also occurs on the face and neck.1 The lesions usually are present at birth but also can develop during the first year of life.2 Diagnosis may be later, during adolescence, when patients seek medical attention during the lesion’s rapid growth phase.1 Nevus sebaceus also is known as an organoid nevus because it may contain all components of the skin. It was originally identified by Jadassohn in 1895.3 It presents as a yellowish, smooth, hairless patch or plaque in prepubertal patients. During adolescence, the lesion typically becomes more yellowish, as well as papillomatous, scaly, or warty. The reported incidence of NS is 0.05% to 1% in dermatology patients.2

Differential

Nevus sebaceus also is a component of several syndromes that should be kept in mind, including Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome, which presents with neurologic, skeletal, genitourinary, cardiovascular, and ophthalmic disorders, in addition to cutaneous features. Others include phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica, didmyosis aplasticosebacea, SCALP syndrome (sebaceus nevus, central nervous system malformations, aplasia cutis congenita, limbal dermoid, and pigmented nevus), and more.4,5

Etiology

The etiology of NS has not been completely determined. One study that evaluated 44 NS tissue samples suggested the presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in NS formation, finding that 82% of NS lesions studied contained HPV DNA. From these results, Carlson et al6 suggested a possible maternal transmission of HPV and infection of ectodermal cells as a potential cause of NS; however, this hypothesis was soon challenged by a study that showed a complete absence of HPV in 16 samples via histological evaluation and polymerase chain reaction for a broad range of HPV types.7 There were investigations into a patched (PTCH) deletion as the cause of NS and thus explained the historically high rate of secondary BCC.8 Further studies showed no mutations at the PTCH locus in trichoblastomas or other tumors arising from NS.9,10

More recent studies have recognized HRAS and KRAS mutations as a causative factor in NS.11 Nevus sebaceus belongs to a group of syndromes resulting from lethal mutations that survive via mosaicism. Nevus sebaceus is caused by postzygotic HRAS or KRAS mutations and is known as a mosaic RASopathy.12 In fact, there is growing evidence to suggest that other nevoid proliferations including keratinocytic epidermal nevi and melanocytic nevi also fall into the spectrum of mosaic RASopathies.13

Staging

There are 3 clinical stages of NS, originally described by Mehregan and Pinkus.14 In stage I (historically known as the infantile stage), the lesion presents as a yellow to pink, smooth, hairless patch. Histologic features include immature hair follicles and hypoplastic sebaceous glands. In stage II (also known as the puberty stage), the lesion becomes more pronounced. Firmer plaques can develop with hyperkeratosis. Hormonal changes cause sebaceous glands to develop, accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and maturation of apocrine glands. Stage III (the tumoral stage) is a period that various neoplasms have the highest likelihood of occurring. Nevus sebaceus in an adolescent or adult demonstrates mature adnexal structures and greater epidermal hyperplasia.2,4,15

Malignancy

By virtue of these stages of NS development, malignant transformation is expected most often during stage III. However, cases have been reported of malignant tumor development in NS in children before puberty. Two case reports described a 7-year-old boy and a 10-year-old boy diagnosed with a BCC arising from an NS.16,17 However, secondary BCC formation before 16 years of age is rare. Basal cell carcinoma arising from an NS has been commonly reported and is the most common malignant neoplasm in NS (1.1%).2,3 However, the most common neoplasm overall is trichoblastoma (7.4%). The second most common tumor was syringocystadenoma papilliferum, occurring in approximately 5.2% of NS cases. The neoplasm rate in NS was found to be proportional to the patient age.2,18 Multiple studies have shown the overall rate of secondary neoplasms in NS to be 13% to 21.4%, with malignant tumors composing 0.8% to 2.5%.2,15,19 Other neoplasms that have been reported include keratoacanthoma, trichilemmoma, sebaceoma, nevocellular nevus, squamous cell carcinoma, adnexal carcinoma, apocrine adenocarcinoma, and malignant melanoma.19-21

It is argued that the reported rate of BCC formation is overestimated, as prior studies incorrectly labeled trichoblastomas as BCCs. In fact, the largest studies of NS from the 1990s revealed lower rates of malignant secondary tumors than previously determined.4

The identification of apocrine adenocarcinoma tumors arising from NS is exceedingly rare. A study performed by Cribier et al19 in 2000 retrospect

Histopathology

Histopathologic examination reveals considerable variation in morphology, and an underlying pattern has been difficult to recognize. Unfortunately, some authors have concluded that the diagnosis of apocrine carcinoma is relatively subjective.26 Robson et al26 identified 3 general architectural patterns: tubular, tubulopapillary, and solid. Tubular structures consisted of glands and ducts lined by a single or multilayered epithelium. Tubulopapillary architecture was characterized by epithelium forming papillary folds without a fibrovascular core. The solid morphology showed sheets of cells with limited ductal or tubular formation.26 The most specific criteria of these apocrine carcinomas are identification of decapitation secretion, periodic acid–Schiff–positive diastase-resistant material present in the cells or lumen, and positive immunostaining for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15.27

Robson et al26 reported estrogen receptor positivity and androgen receptor positivity in 62% and 64% of 24 primary apocrine carcinoma cases, respectively. However, whether these markers are as common in NS-related apocrine carcinomas has yet to be noted in the literature. One study reports a case of apocrine carcinoma from NS with positive staining for human epidermal growth factor-2, a cell membrane receptor tyrosine kinase commonly investigated in breast cancers and extramammary Paget disease.22

These apocrine carcinomas do have the potential for lymphatic metastasis, as seen with multiple studies. Domingo and Helwig21 identified regional lymph node metastasis in 2 of its 4 apocrine carcinoma patients. Robson et al26 reported lymphovascular invasion in 4 cases and perineural invasion in 2 of 24 patients studied. However, even in the context of recurrence and regional metastasis, the prognosis was good and seldom fatal.26

Treatment

The most effective treatment of NS is excision of dermal and epidermal components. Excision should be completed with a minimum of 2- to 3-mm margins and full thickness down to the underlying supporting fat.28 Historically, the practice of prophylactic excision of NS was supported by the potential for malignant transformation; however, early excision of NS may be less reasonable in light of these more recent studies showing lower incidence of BCC (0.8%), replaced by benign trichoblastomas.19 In the case of apocrine carcinoma development, excision is undoubtedly recommended, with unclear recommendations regarding further evaluation for metastasis.

Excision also may be favored for cosmetic purposes, given the visible regions where NS tends to develop. Chepla and Gosain29 argued that surgical intervention should be based on other factors such as location on the scalp, alopecia, and other issues affecting appearance and monitoring rather than incidence of malignant transformation. Close monitoring and biopsy of suspicious areas is a more conservative option.

Other therapies include CO2 laser, as demonstrated by Kiedrowicz et al,30 on linear NS in a patient with Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome.31 However, this approach is palliative and not effective in removing the entire lesion. Electrodesiccation and curettage and dermabrasion also are not good options for the same reason.4

Occurrence in Children

Nevus sebaceus in children, accompanied by other findings suggestive of epidermal nevus syndromes, should prompt further investigation. Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome includes major neurological abnormalities including hemimegalencephaly and seizures.32

Conclusion

Apocrine carcinomas are malignant neoplasms that may rarely arise within an NS. Their clinical identification is difficult and requires histopathologic evaluation. Upon recognition, prompt excision with tumor-free margins is recommended. As a rare entity, little data is available regarding its metastatic potential or overall survival rates. Further investigation is clearly necessary as new cases arise.

- Kamyab-Hesari K, Balochi K, Afshar N, et al. Clinicopathological study of 1016 consecutive adnexal skin tumors. Acta Med Iran. 2013;51:879-885.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Ball EA, Hussain M, Moss AL. Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising in a naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:259-260.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH. Nevus sebaceous revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:15-23.

- Happle R. The group of epidermal nevus syndromes part I. well defined phenotypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1-22; quiz 23-24.

- Carlson JA, Cribier B, Nuovo G, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated and genital-mucosal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA are prevalent in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:279-294.

- Kim D, Benjamin LT, Sahoo MK, et al. Human papilloma virus is not prevalent in nevus sebaceus [published online November 14, 2013]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:326-330.

- Xin H, Matt D, Qin JZ, et al. The sebaceous nevus: a nevus with deletions of the PTCH gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1834-1836.

- Hafner C, Schmiemann V, Ruetten A, et al. PTCH mutations are not mainly involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic trichoblastomas. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1496-1500.

- Takata M, Tojo M, Hatta N, et al. No evidence of deregulated patched-hedgehog signaling pathway in trichoblastomas and other tumors arising within nevus sebaceous. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1666-1670.

- Levinsohn JL, Tian LC, Boyden LM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals somatic mutations in HRAS and KRAS, which cause nevus sebaceus [published online October 25, 2012]. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:827-830.

- Happle R. Nevus sebaceus is a mosaic RASopathy. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:597-600.

- Luo S, Tsao H. Epidermal, sebaceous, and melanocytic nevoid proliferations are spectrums of mosaic RASopathies. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2493-2496.

- Mehregan AH, Pinkus H. Life history of organoid nevi. special reference to nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:574-588.

- Muñoz-Pérez MA, García-Hernandez MJ, Ríos JJ, et al. Sebaceus naevi: a clinicopathologic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:319-324.

- Altaykan A, Ersoy-Evans S, Erkin G, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in nevus sebaceous during childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:616-619.

- Turner CD, Shea CR, Rosoff PM. Basal cell carcinoma originating from a nevus sebaceus on the scalp of a 7-year-old boy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:247-249.

- Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:108-118.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Paudel U, Jha A, Pokhrel DB, et al. Apocrine carcinoma developing in a naevus sebaceous of scalp. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012;10:103-105.

- Domingo J, Helwig EB. Malignant neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:545-556.

- Tanese K, Wakabayashi A, Suzuki T, et al. Immunoexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 in apocrine carcinoma arising in naevus sebaceous, case report [published online August 23, 2009]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:360-362.

- Dalle S, Skowron F, Balme B, et al. Apocrine carcinoma developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:487-489.

- Jacyk WK, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, et al. Tubular apocrine carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:389-392.

- Ansai S, Koseki S, Hashimoto H, et al. A case of ductal sweat gland carcinoma connected to syringocystadenoma papilliferum arising in nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:557-563.

- Robson A, Lazar AJ, Ben Nagi J, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma: a clinico-pathologic analysis of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:682-690.

- Paties C, Taccagni GL, Papotti M, et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1993;71:375-381.

- Davison SP, Khachemoune A, Yu D, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn revisited with reconstruction options. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:145-150.

- Chepla KJ, Gosain AK. Giant nevus sebaceus: definition, surgical techniques, and rationale for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:296E-304E.

- Kiedrowicz M, Kacalak-Rzepka A, Królicki A et al. Therapeutic effects of CO2 laser therapy of linear nevus sebaceous in the course of the Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome. Postepy Dermatol Allergol. 2013;30:320-323.

- Ashinoff R. Linear nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn treated with the carbon dioxide laser. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:189-191.

- van de Warrenburg BP, van Gulik S, Renier WO, et al. The linear naevus sebaceus syndrome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998;100:126-132.

Nevus sebaceus (NS) is a benign hair follicle neoplasm present in approximately 1.3% of the population, typically involving the scalp, neck, or face.1 These lesions usually are present at birth or identified soon after, during the first year. They present as a yellowish hairless patch or plaque but can develop a more papillomatous appearance, especially after puberty. Historically, the concern with NS was its tendency to transform into basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which prompted surgical excision of the lesion during childhood. This theory has been discounted more recently, as further research has suggested that what was once thought to be BCC may have been confused with the similarly appearing trichoblastoma; however, malignant transformation of NS does still occur, with BCC still being the most common.2 We present the case of a long-standing NS with rare transformation to apocrine carcinoma.

Case Report

A 76-year-old woman presented with several new lesions within a previously diagnosed NS. She reported having the large plaque for as long as she could recall but reported that several new growths developed within the plaque over the last 2 months, slowly increasing in size. She reported a prior biopsy within the growth several years prior, which she described as an irritated seborrheic keratosis.

Physical examination demonstrated 4 distinct lesions within the flesh-colored, verrucous plaque located on the left side of the temporal scalp (Figure 1). The first lesion was a 2.5-cm pearly, pink, exophytic tumor (labeled as A in Figure 1). The next 2 lesions were brown, pedunculated, verrucous papules (labeled as B and C in Figure 1). The last lesion was a purple papule (labeled as D in Figure 1). Four shave biopsies were performed for histologic analysis of the lesions. Lesions B, C, and D were consistent with trichoblastomas, as pathology showed basaloid epithelial tumors that displayed primitive follicular structures, areas of stromal induction, and some pigmentation. Lesion A, originally thought to be suspicious for a BCC, was determined to be a primary cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma upon pathologic review. The pathology showed a dermal tumor displaying solid and tubular areas with decapitation secretion. Nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses were present (Figure 2), and staining for carcinoembryonic antigen was positive (Figure 3). Immunoreactivity with epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 was noted as well as focal positivity for mammaglobin. Primary apocrine carcinoma was favored over metastatic carcinoma due to the location of the lesion within an NS along with a negative history of internal malignancy. Dermatopathology recommended complete removal of all lesions within the NS.

Upon discussing biopsy results and recommendations with our patient, she agreed to undergo excision with intraoperative pathology by a plastic surgeon within our practice to ensure clear margins. The surgical defect following excision was sizeable and closed utilizing a rhomboid flap, full-thickness skin graft, and a split-thickness skin graft. At surgical follow-up, she was doing well and there have been no signs of local recurrence for 10 months since excision.

Comment

Presentation

Nevus sebaceus is the most common adnexal tumor and is classified as a benign congenital hair follicle tumor that is located most commonly on the scalp but also occurs on the face and neck.1 The lesions usually are present at birth but also can develop during the first year of life.2 Diagnosis may be later, during adolescence, when patients seek medical attention during the lesion’s rapid growth phase.1 Nevus sebaceus also is known as an organoid nevus because it may contain all components of the skin. It was originally identified by Jadassohn in 1895.3 It presents as a yellowish, smooth, hairless patch or plaque in prepubertal patients. During adolescence, the lesion typically becomes more yellowish, as well as papillomatous, scaly, or warty. The reported incidence of NS is 0.05% to 1% in dermatology patients.2

Differential

Nevus sebaceus also is a component of several syndromes that should be kept in mind, including Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome, which presents with neurologic, skeletal, genitourinary, cardiovascular, and ophthalmic disorders, in addition to cutaneous features. Others include phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica, didmyosis aplasticosebacea, SCALP syndrome (sebaceus nevus, central nervous system malformations, aplasia cutis congenita, limbal dermoid, and pigmented nevus), and more.4,5

Etiology

The etiology of NS has not been completely determined. One study that evaluated 44 NS tissue samples suggested the presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in NS formation, finding that 82% of NS lesions studied contained HPV DNA. From these results, Carlson et al6 suggested a possible maternal transmission of HPV and infection of ectodermal cells as a potential cause of NS; however, this hypothesis was soon challenged by a study that showed a complete absence of HPV in 16 samples via histological evaluation and polymerase chain reaction for a broad range of HPV types.7 There were investigations into a patched (PTCH) deletion as the cause of NS and thus explained the historically high rate of secondary BCC.8 Further studies showed no mutations at the PTCH locus in trichoblastomas or other tumors arising from NS.9,10

More recent studies have recognized HRAS and KRAS mutations as a causative factor in NS.11 Nevus sebaceus belongs to a group of syndromes resulting from lethal mutations that survive via mosaicism. Nevus sebaceus is caused by postzygotic HRAS or KRAS mutations and is known as a mosaic RASopathy.12 In fact, there is growing evidence to suggest that other nevoid proliferations including keratinocytic epidermal nevi and melanocytic nevi also fall into the spectrum of mosaic RASopathies.13

Staging

There are 3 clinical stages of NS, originally described by Mehregan and Pinkus.14 In stage I (historically known as the infantile stage), the lesion presents as a yellow to pink, smooth, hairless patch. Histologic features include immature hair follicles and hypoplastic sebaceous glands. In stage II (also known as the puberty stage), the lesion becomes more pronounced. Firmer plaques can develop with hyperkeratosis. Hormonal changes cause sebaceous glands to develop, accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and maturation of apocrine glands. Stage III (the tumoral stage) is a period that various neoplasms have the highest likelihood of occurring. Nevus sebaceus in an adolescent or adult demonstrates mature adnexal structures and greater epidermal hyperplasia.2,4,15

Malignancy

By virtue of these stages of NS development, malignant transformation is expected most often during stage III. However, cases have been reported of malignant tumor development in NS in children before puberty. Two case reports described a 7-year-old boy and a 10-year-old boy diagnosed with a BCC arising from an NS.16,17 However, secondary BCC formation before 16 years of age is rare. Basal cell carcinoma arising from an NS has been commonly reported and is the most common malignant neoplasm in NS (1.1%).2,3 However, the most common neoplasm overall is trichoblastoma (7.4%). The second most common tumor was syringocystadenoma papilliferum, occurring in approximately 5.2% of NS cases. The neoplasm rate in NS was found to be proportional to the patient age.2,18 Multiple studies have shown the overall rate of secondary neoplasms in NS to be 13% to 21.4%, with malignant tumors composing 0.8% to 2.5%.2,15,19 Other neoplasms that have been reported include keratoacanthoma, trichilemmoma, sebaceoma, nevocellular nevus, squamous cell carcinoma, adnexal carcinoma, apocrine adenocarcinoma, and malignant melanoma.19-21

It is argued that the reported rate of BCC formation is overestimated, as prior studies incorrectly labeled trichoblastomas as BCCs. In fact, the largest studies of NS from the 1990s revealed lower rates of malignant secondary tumors than previously determined.4

The identification of apocrine adenocarcinoma tumors arising from NS is exceedingly rare. A study performed by Cribier et al19 in 2000 retrospect

Histopathology

Histopathologic examination reveals considerable variation in morphology, and an underlying pattern has been difficult to recognize. Unfortunately, some authors have concluded that the diagnosis of apocrine carcinoma is relatively subjective.26 Robson et al26 identified 3 general architectural patterns: tubular, tubulopapillary, and solid. Tubular structures consisted of glands and ducts lined by a single or multilayered epithelium. Tubulopapillary architecture was characterized by epithelium forming papillary folds without a fibrovascular core. The solid morphology showed sheets of cells with limited ductal or tubular formation.26 The most specific criteria of these apocrine carcinomas are identification of decapitation secretion, periodic acid–Schiff–positive diastase-resistant material present in the cells or lumen, and positive immunostaining for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15.27

Robson et al26 reported estrogen receptor positivity and androgen receptor positivity in 62% and 64% of 24 primary apocrine carcinoma cases, respectively. However, whether these markers are as common in NS-related apocrine carcinomas has yet to be noted in the literature. One study reports a case of apocrine carcinoma from NS with positive staining for human epidermal growth factor-2, a cell membrane receptor tyrosine kinase commonly investigated in breast cancers and extramammary Paget disease.22

These apocrine carcinomas do have the potential for lymphatic metastasis, as seen with multiple studies. Domingo and Helwig21 identified regional lymph node metastasis in 2 of its 4 apocrine carcinoma patients. Robson et al26 reported lymphovascular invasion in 4 cases and perineural invasion in 2 of 24 patients studied. However, even in the context of recurrence and regional metastasis, the prognosis was good and seldom fatal.26

Treatment

The most effective treatment of NS is excision of dermal and epidermal components. Excision should be completed with a minimum of 2- to 3-mm margins and full thickness down to the underlying supporting fat.28 Historically, the practice of prophylactic excision of NS was supported by the potential for malignant transformation; however, early excision of NS may be less reasonable in light of these more recent studies showing lower incidence of BCC (0.8%), replaced by benign trichoblastomas.19 In the case of apocrine carcinoma development, excision is undoubtedly recommended, with unclear recommendations regarding further evaluation for metastasis.

Excision also may be favored for cosmetic purposes, given the visible regions where NS tends to develop. Chepla and Gosain29 argued that surgical intervention should be based on other factors such as location on the scalp, alopecia, and other issues affecting appearance and monitoring rather than incidence of malignant transformation. Close monitoring and biopsy of suspicious areas is a more conservative option.

Other therapies include CO2 laser, as demonstrated by Kiedrowicz et al,30 on linear NS in a patient with Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome.31 However, this approach is palliative and not effective in removing the entire lesion. Electrodesiccation and curettage and dermabrasion also are not good options for the same reason.4

Occurrence in Children

Nevus sebaceus in children, accompanied by other findings suggestive of epidermal nevus syndromes, should prompt further investigation. Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome includes major neurological abnormalities including hemimegalencephaly and seizures.32

Conclusion

Apocrine carcinomas are malignant neoplasms that may rarely arise within an NS. Their clinical identification is difficult and requires histopathologic evaluation. Upon recognition, prompt excision with tumor-free margins is recommended. As a rare entity, little data is available regarding its metastatic potential or overall survival rates. Further investigation is clearly necessary as new cases arise.

Nevus sebaceus (NS) is a benign hair follicle neoplasm present in approximately 1.3% of the population, typically involving the scalp, neck, or face.1 These lesions usually are present at birth or identified soon after, during the first year. They present as a yellowish hairless patch or plaque but can develop a more papillomatous appearance, especially after puberty. Historically, the concern with NS was its tendency to transform into basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which prompted surgical excision of the lesion during childhood. This theory has been discounted more recently, as further research has suggested that what was once thought to be BCC may have been confused with the similarly appearing trichoblastoma; however, malignant transformation of NS does still occur, with BCC still being the most common.2 We present the case of a long-standing NS with rare transformation to apocrine carcinoma.

Case Report

A 76-year-old woman presented with several new lesions within a previously diagnosed NS. She reported having the large plaque for as long as she could recall but reported that several new growths developed within the plaque over the last 2 months, slowly increasing in size. She reported a prior biopsy within the growth several years prior, which she described as an irritated seborrheic keratosis.

Physical examination demonstrated 4 distinct lesions within the flesh-colored, verrucous plaque located on the left side of the temporal scalp (Figure 1). The first lesion was a 2.5-cm pearly, pink, exophytic tumor (labeled as A in Figure 1). The next 2 lesions were brown, pedunculated, verrucous papules (labeled as B and C in Figure 1). The last lesion was a purple papule (labeled as D in Figure 1). Four shave biopsies were performed for histologic analysis of the lesions. Lesions B, C, and D were consistent with trichoblastomas, as pathology showed basaloid epithelial tumors that displayed primitive follicular structures, areas of stromal induction, and some pigmentation. Lesion A, originally thought to be suspicious for a BCC, was determined to be a primary cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma upon pathologic review. The pathology showed a dermal tumor displaying solid and tubular areas with decapitation secretion. Nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses were present (Figure 2), and staining for carcinoembryonic antigen was positive (Figure 3). Immunoreactivity with epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin 7 was noted as well as focal positivity for mammaglobin. Primary apocrine carcinoma was favored over metastatic carcinoma due to the location of the lesion within an NS along with a negative history of internal malignancy. Dermatopathology recommended complete removal of all lesions within the NS.

Upon discussing biopsy results and recommendations with our patient, she agreed to undergo excision with intraoperative pathology by a plastic surgeon within our practice to ensure clear margins. The surgical defect following excision was sizeable and closed utilizing a rhomboid flap, full-thickness skin graft, and a split-thickness skin graft. At surgical follow-up, she was doing well and there have been no signs of local recurrence for 10 months since excision.

Comment

Presentation

Nevus sebaceus is the most common adnexal tumor and is classified as a benign congenital hair follicle tumor that is located most commonly on the scalp but also occurs on the face and neck.1 The lesions usually are present at birth but also can develop during the first year of life.2 Diagnosis may be later, during adolescence, when patients seek medical attention during the lesion’s rapid growth phase.1 Nevus sebaceus also is known as an organoid nevus because it may contain all components of the skin. It was originally identified by Jadassohn in 1895.3 It presents as a yellowish, smooth, hairless patch or plaque in prepubertal patients. During adolescence, the lesion typically becomes more yellowish, as well as papillomatous, scaly, or warty. The reported incidence of NS is 0.05% to 1% in dermatology patients.2

Differential

Nevus sebaceus also is a component of several syndromes that should be kept in mind, including Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome, which presents with neurologic, skeletal, genitourinary, cardiovascular, and ophthalmic disorders, in addition to cutaneous features. Others include phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica, didmyosis aplasticosebacea, SCALP syndrome (sebaceus nevus, central nervous system malformations, aplasia cutis congenita, limbal dermoid, and pigmented nevus), and more.4,5

Etiology

The etiology of NS has not been completely determined. One study that evaluated 44 NS tissue samples suggested the presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in NS formation, finding that 82% of NS lesions studied contained HPV DNA. From these results, Carlson et al6 suggested a possible maternal transmission of HPV and infection of ectodermal cells as a potential cause of NS; however, this hypothesis was soon challenged by a study that showed a complete absence of HPV in 16 samples via histological evaluation and polymerase chain reaction for a broad range of HPV types.7 There were investigations into a patched (PTCH) deletion as the cause of NS and thus explained the historically high rate of secondary BCC.8 Further studies showed no mutations at the PTCH locus in trichoblastomas or other tumors arising from NS.9,10

More recent studies have recognized HRAS and KRAS mutations as a causative factor in NS.11 Nevus sebaceus belongs to a group of syndromes resulting from lethal mutations that survive via mosaicism. Nevus sebaceus is caused by postzygotic HRAS or KRAS mutations and is known as a mosaic RASopathy.12 In fact, there is growing evidence to suggest that other nevoid proliferations including keratinocytic epidermal nevi and melanocytic nevi also fall into the spectrum of mosaic RASopathies.13

Staging

There are 3 clinical stages of NS, originally described by Mehregan and Pinkus.14 In stage I (historically known as the infantile stage), the lesion presents as a yellow to pink, smooth, hairless patch. Histologic features include immature hair follicles and hypoplastic sebaceous glands. In stage II (also known as the puberty stage), the lesion becomes more pronounced. Firmer plaques can develop with hyperkeratosis. Hormonal changes cause sebaceous glands to develop, accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and maturation of apocrine glands. Stage III (the tumoral stage) is a period that various neoplasms have the highest likelihood of occurring. Nevus sebaceus in an adolescent or adult demonstrates mature adnexal structures and greater epidermal hyperplasia.2,4,15

Malignancy

By virtue of these stages of NS development, malignant transformation is expected most often during stage III. However, cases have been reported of malignant tumor development in NS in children before puberty. Two case reports described a 7-year-old boy and a 10-year-old boy diagnosed with a BCC arising from an NS.16,17 However, secondary BCC formation before 16 years of age is rare. Basal cell carcinoma arising from an NS has been commonly reported and is the most common malignant neoplasm in NS (1.1%).2,3 However, the most common neoplasm overall is trichoblastoma (7.4%). The second most common tumor was syringocystadenoma papilliferum, occurring in approximately 5.2% of NS cases. The neoplasm rate in NS was found to be proportional to the patient age.2,18 Multiple studies have shown the overall rate of secondary neoplasms in NS to be 13% to 21.4%, with malignant tumors composing 0.8% to 2.5%.2,15,19 Other neoplasms that have been reported include keratoacanthoma, trichilemmoma, sebaceoma, nevocellular nevus, squamous cell carcinoma, adnexal carcinoma, apocrine adenocarcinoma, and malignant melanoma.19-21

It is argued that the reported rate of BCC formation is overestimated, as prior studies incorrectly labeled trichoblastomas as BCCs. In fact, the largest studies of NS from the 1990s revealed lower rates of malignant secondary tumors than previously determined.4

The identification of apocrine adenocarcinoma tumors arising from NS is exceedingly rare. A study performed by Cribier et al19 in 2000 retrospect

Histopathology

Histopathologic examination reveals considerable variation in morphology, and an underlying pattern has been difficult to recognize. Unfortunately, some authors have concluded that the diagnosis of apocrine carcinoma is relatively subjective.26 Robson et al26 identified 3 general architectural patterns: tubular, tubulopapillary, and solid. Tubular structures consisted of glands and ducts lined by a single or multilayered epithelium. Tubulopapillary architecture was characterized by epithelium forming papillary folds without a fibrovascular core. The solid morphology showed sheets of cells with limited ductal or tubular formation.26 The most specific criteria of these apocrine carcinomas are identification of decapitation secretion, periodic acid–Schiff–positive diastase-resistant material present in the cells or lumen, and positive immunostaining for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15.27

Robson et al26 reported estrogen receptor positivity and androgen receptor positivity in 62% and 64% of 24 primary apocrine carcinoma cases, respectively. However, whether these markers are as common in NS-related apocrine carcinomas has yet to be noted in the literature. One study reports a case of apocrine carcinoma from NS with positive staining for human epidermal growth factor-2, a cell membrane receptor tyrosine kinase commonly investigated in breast cancers and extramammary Paget disease.22

These apocrine carcinomas do have the potential for lymphatic metastasis, as seen with multiple studies. Domingo and Helwig21 identified regional lymph node metastasis in 2 of its 4 apocrine carcinoma patients. Robson et al26 reported lymphovascular invasion in 4 cases and perineural invasion in 2 of 24 patients studied. However, even in the context of recurrence and regional metastasis, the prognosis was good and seldom fatal.26

Treatment

The most effective treatment of NS is excision of dermal and epidermal components. Excision should be completed with a minimum of 2- to 3-mm margins and full thickness down to the underlying supporting fat.28 Historically, the practice of prophylactic excision of NS was supported by the potential for malignant transformation; however, early excision of NS may be less reasonable in light of these more recent studies showing lower incidence of BCC (0.8%), replaced by benign trichoblastomas.19 In the case of apocrine carcinoma development, excision is undoubtedly recommended, with unclear recommendations regarding further evaluation for metastasis.

Excision also may be favored for cosmetic purposes, given the visible regions where NS tends to develop. Chepla and Gosain29 argued that surgical intervention should be based on other factors such as location on the scalp, alopecia, and other issues affecting appearance and monitoring rather than incidence of malignant transformation. Close monitoring and biopsy of suspicious areas is a more conservative option.

Other therapies include CO2 laser, as demonstrated by Kiedrowicz et al,30 on linear NS in a patient with Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome.31 However, this approach is palliative and not effective in removing the entire lesion. Electrodesiccation and curettage and dermabrasion also are not good options for the same reason.4

Occurrence in Children

Nevus sebaceus in children, accompanied by other findings suggestive of epidermal nevus syndromes, should prompt further investigation. Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome includes major neurological abnormalities including hemimegalencephaly and seizures.32

Conclusion

Apocrine carcinomas are malignant neoplasms that may rarely arise within an NS. Their clinical identification is difficult and requires histopathologic evaluation. Upon recognition, prompt excision with tumor-free margins is recommended. As a rare entity, little data is available regarding its metastatic potential or overall survival rates. Further investigation is clearly necessary as new cases arise.

- Kamyab-Hesari K, Balochi K, Afshar N, et al. Clinicopathological study of 1016 consecutive adnexal skin tumors. Acta Med Iran. 2013;51:879-885.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Ball EA, Hussain M, Moss AL. Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising in a naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:259-260.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH. Nevus sebaceous revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:15-23.

- Happle R. The group of epidermal nevus syndromes part I. well defined phenotypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1-22; quiz 23-24.

- Carlson JA, Cribier B, Nuovo G, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated and genital-mucosal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA are prevalent in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:279-294.

- Kim D, Benjamin LT, Sahoo MK, et al. Human papilloma virus is not prevalent in nevus sebaceus [published online November 14, 2013]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:326-330.

- Xin H, Matt D, Qin JZ, et al. The sebaceous nevus: a nevus with deletions of the PTCH gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1834-1836.

- Hafner C, Schmiemann V, Ruetten A, et al. PTCH mutations are not mainly involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic trichoblastomas. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1496-1500.

- Takata M, Tojo M, Hatta N, et al. No evidence of deregulated patched-hedgehog signaling pathway in trichoblastomas and other tumors arising within nevus sebaceous. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1666-1670.

- Levinsohn JL, Tian LC, Boyden LM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals somatic mutations in HRAS and KRAS, which cause nevus sebaceus [published online October 25, 2012]. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:827-830.

- Happle R. Nevus sebaceus is a mosaic RASopathy. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:597-600.

- Luo S, Tsao H. Epidermal, sebaceous, and melanocytic nevoid proliferations are spectrums of mosaic RASopathies. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2493-2496.

- Mehregan AH, Pinkus H. Life history of organoid nevi. special reference to nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:574-588.

- Muñoz-Pérez MA, García-Hernandez MJ, Ríos JJ, et al. Sebaceus naevi: a clinicopathologic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:319-324.

- Altaykan A, Ersoy-Evans S, Erkin G, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in nevus sebaceous during childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:616-619.

- Turner CD, Shea CR, Rosoff PM. Basal cell carcinoma originating from a nevus sebaceus on the scalp of a 7-year-old boy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:247-249.

- Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:108-118.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Paudel U, Jha A, Pokhrel DB, et al. Apocrine carcinoma developing in a naevus sebaceous of scalp. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012;10:103-105.

- Domingo J, Helwig EB. Malignant neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:545-556.

- Tanese K, Wakabayashi A, Suzuki T, et al. Immunoexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 in apocrine carcinoma arising in naevus sebaceous, case report [published online August 23, 2009]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:360-362.

- Dalle S, Skowron F, Balme B, et al. Apocrine carcinoma developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:487-489.

- Jacyk WK, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, et al. Tubular apocrine carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:389-392.

- Ansai S, Koseki S, Hashimoto H, et al. A case of ductal sweat gland carcinoma connected to syringocystadenoma papilliferum arising in nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:557-563.

- Robson A, Lazar AJ, Ben Nagi J, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma: a clinico-pathologic analysis of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:682-690.

- Paties C, Taccagni GL, Papotti M, et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1993;71:375-381.

- Davison SP, Khachemoune A, Yu D, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn revisited with reconstruction options. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:145-150.

- Chepla KJ, Gosain AK. Giant nevus sebaceus: definition, surgical techniques, and rationale for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:296E-304E.

- Kiedrowicz M, Kacalak-Rzepka A, Królicki A et al. Therapeutic effects of CO2 laser therapy of linear nevus sebaceous in the course of the Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome. Postepy Dermatol Allergol. 2013;30:320-323.

- Ashinoff R. Linear nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn treated with the carbon dioxide laser. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:189-191.

- van de Warrenburg BP, van Gulik S, Renier WO, et al. The linear naevus sebaceus syndrome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998;100:126-132.

- Kamyab-Hesari K, Balochi K, Afshar N, et al. Clinicopathological study of 1016 consecutive adnexal skin tumors. Acta Med Iran. 2013;51:879-885.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Ball EA, Hussain M, Moss AL. Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising in a naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn: case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:259-260.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH. Nevus sebaceous revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:15-23.

- Happle R. The group of epidermal nevus syndromes part I. well defined phenotypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1-22; quiz 23-24.

- Carlson JA, Cribier B, Nuovo G, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated and genital-mucosal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA are prevalent in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:279-294.

- Kim D, Benjamin LT, Sahoo MK, et al. Human papilloma virus is not prevalent in nevus sebaceus [published online November 14, 2013]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:326-330.

- Xin H, Matt D, Qin JZ, et al. The sebaceous nevus: a nevus with deletions of the PTCH gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1834-1836.

- Hafner C, Schmiemann V, Ruetten A, et al. PTCH mutations are not mainly involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic trichoblastomas. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1496-1500.

- Takata M, Tojo M, Hatta N, et al. No evidence of deregulated patched-hedgehog signaling pathway in trichoblastomas and other tumors arising within nevus sebaceous. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1666-1670.

- Levinsohn JL, Tian LC, Boyden LM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals somatic mutations in HRAS and KRAS, which cause nevus sebaceus [published online October 25, 2012]. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:827-830.

- Happle R. Nevus sebaceus is a mosaic RASopathy. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:597-600.

- Luo S, Tsao H. Epidermal, sebaceous, and melanocytic nevoid proliferations are spectrums of mosaic RASopathies. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2493-2496.

- Mehregan AH, Pinkus H. Life history of organoid nevi. special reference to nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:574-588.

- Muñoz-Pérez MA, García-Hernandez MJ, Ríos JJ, et al. Sebaceus naevi: a clinicopathologic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:319-324.

- Altaykan A, Ersoy-Evans S, Erkin G, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in nevus sebaceous during childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:616-619.

- Turner CD, Shea CR, Rosoff PM. Basal cell carcinoma originating from a nevus sebaceus on the scalp of a 7-year-old boy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:247-249.

- Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:108-118.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Paudel U, Jha A, Pokhrel DB, et al. Apocrine carcinoma developing in a naevus sebaceous of scalp. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012;10:103-105.

- Domingo J, Helwig EB. Malignant neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:545-556.

- Tanese K, Wakabayashi A, Suzuki T, et al. Immunoexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 in apocrine carcinoma arising in naevus sebaceous, case report [published online August 23, 2009]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:360-362.

- Dalle S, Skowron F, Balme B, et al. Apocrine carcinoma developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:487-489.

- Jacyk WK, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, et al. Tubular apocrine carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:389-392.

- Ansai S, Koseki S, Hashimoto H, et al. A case of ductal sweat gland carcinoma connected to syringocystadenoma papilliferum arising in nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:557-563.

- Robson A, Lazar AJ, Ben Nagi J, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma: a clinico-pathologic analysis of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:682-690.

- Paties C, Taccagni GL, Papotti M, et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1993;71:375-381.

- Davison SP, Khachemoune A, Yu D, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn revisited with reconstruction options. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:145-150.

- Chepla KJ, Gosain AK. Giant nevus sebaceus: definition, surgical techniques, and rationale for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:296E-304E.

- Kiedrowicz M, Kacalak-Rzepka A, Królicki A et al. Therapeutic effects of CO2 laser therapy of linear nevus sebaceous in the course of the Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome. Postepy Dermatol Allergol. 2013;30:320-323.

- Ashinoff R. Linear nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn treated with the carbon dioxide laser. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:189-191.

- van de Warrenburg BP, van Gulik S, Renier WO, et al. The linear naevus sebaceus syndrome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998;100:126-132.

Practice Points

- Nevus sebaceus (NS) in the centrofacial region has been correlated with a higher risk for neurological abnormalities, including intellectual disability and seizures.

- Historically, basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) were considered a common occurrence arising from an NS, prompting prophylactic surgical excision of such lesions.

- More recently, it has been recognized that the most common tumor to arise from NS is trichoblastoma rather than BCC; in fact, BCC and other malignancies have been found to be relatively rare compared to their benign counterparts.

- In light of this discovery, observation of NS may be a more prudent course of treatment versus prophylactic surgical excision.

Pediatric Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

In 1960, Gorlin and Goltz1 first described nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) as a distinct clinical entity with multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), jaw cysts, and bifid ribs. This rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis has a minimal prevalence of 1 case per 57,000 individuals2 and no sexual predilection.3 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is caused by a mutation in the human homolog of a Drosophila gene, patched 1 (PTCH1), which is located on chromosome 9q22.3.4,5 The major clinical diagnostic criteria includes multiple BCCs, odontogenic keratocysts, palmar or plantar pits, ectopic calcification of the falx cerebri, and a family history of NBCCS.6 Basal cell carcinoma formation is affected by both skin pigmentation and sun exposure; 80% of white patients with NBCCS will develop at least 1 BCC compared to only 40% of black patients with NBCCS.7 Goldstein et al8 postulated that this disparity is associated with increased skin pigmentation providing UV radiation protection, thus decreasing the tumor burden. We report a case of an 11-year-old black boy with NBCCS to highlight the treatment considerations in pediatric cases of NBCCS.

Case Report

An 11-year-old boy with Fitzpatrick skin type V presented with a history of multiple facial lesions after undergoing excision of large keratocysts from the right maxilla, left maxilla, and right mandible. Physical examination revealed multiple light to dark brown facial papules (Figure 1), palmar and plantar pitting (Figure 2), and frontal bossing.

He was previously diagnosed with autism and his surgical history was notable only for excision of the keratocysts. The patient was not taking any medications and did not have any drug allergies. There was no maternal family history of skin cancer or related syndromes; his paternal family history was unknown. A shave biopsy was performed on a facial papule from the right nasolabial fold. Histopathologic evaluation revealed findings consistent with a pigmented nodular BCC (Figure 3). The patient was subsequently sent for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, which demonstrated calcifications along the tentorium. Genetic consultation confirmed a heterozygous mutation of the PTCH1 gene.

Over the next 12 months, the patient had multiple biopsy-proven pigmented BCCs. Initial management of these carcinomas located on cosmetically sensitive areas, including the upper eyelid and penis, were excised by a pediatric plastic surgeon. A truncal carcinoma was treated with electrodesiccation and curettage, which resulted in keloid formation. Early suspicious lesions were treated with imiquimod cream 5% 5 times weekly in combination with the prophylactic use of tretinoin cream 0.1%. Despite this treatment regimen, the patient continued to demonstrate multiple small clinical pigmented BCCs along the malar surfaces of the cheeks and dorsum of the nose. The patient’s mother deferred chemoprevention with an oral retinoid due to the extensive side-effect profile and long-term necessity of administration.

Management also encompassed BCC surveillance every 4 months; annual digital panorex of the jaw; routine dental screening; routine developmental screening; annual follow-up with a geneticist to ensure multidisciplinary care; and annual vision, hearing, and speech-screening examinations. Strict sun-protective measures were encouraged, including wearing a hat during physical education class.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is a multisystem disorder that requires close monitoring under multidisciplinary care. Evans et al6 defined the diagnostic criteria of NBCCS to require the presence of 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor criteria. The major criteria include multiple BCCs, an odontogenic keratocyst or polyostotic bone cyst, palmar or plantar pits, ectopic calcification of the falx cerebri, and family history of NBCCS. The minor criteria are defined as congenital skeletal anomalies; macrocephaly with frontal bossing; cardiac or ovarian fibromas; medulloblastoma; lymphomesenteric cysts; and congenital malformations such as cleft lip or palate, polydactyly, or eye anomalies.6 The mean age of initial BCC diagnosis is 21 years, with proliferation of cancers between puberty and 35 years of age.7,9 Our case is unique due to the patient’s young age at the time of diagnosis as well as his presentation with multiple BCCs with a darker skin type. Kimonis et al7 reported that approximately 20% of black patients develop their first BCC by the age of 21 years and 40% by 35 years. The presence of multiple BCCs is complicated by the limited treatment options in a pediatric patient. The patient’s inability to withstand multiple procedures contributed to our clinical decision to have multiple lesions removed under general anesthesia by a pediatric plastic surgeon.

Due to the patient’s young age of onset, we placed a great emphasis on close surveillance and management. A management protocol for pediatric patients with NBCCS was described by Bree and Shah; BCNS Colloquium Group10 (eTable). We closely followed this protocol for surveillance; however, we scheduled dermatologic examinations every 4 months due to his extensive history of BCCs.

Management

Our case presents a challenging therapeutic and management dilemma. The management of NBCCS utilizes a multitude of treatment modalities, but many of them posed cosmetic challenges in our patient such as postinflammatory hypopigmentation and the propensity for keloid formation. Although surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery is the standard of treatment of nodular BCCs, we were limited due to the patient’s inability to tolerate multiple surgical procedures without the use of general anesthesia.

Case reports have discussed the use of CO2 laser resurfacing for management of multiple facial BCCs in patients with NBCCS. Doctoroff et al11 treated a patient with 45 facial BCCs with full-face CO2 laser resurfacing, and in a 10-month follow-up period the patient developed 6 new BCCs on the face. Nouri et al12 described 3 cases of multiple BCCs on the face, trunk, and extremities treated with ultrapulse CO2 laser with postoperative Mohs sections verifying complete histologic clearance of tumors. All 3 patients had Fitzpatrick skin type IV; their ages were 2, 16, and 35 years. Local anesthesia was used in the 2-year-old patient and intravenous sedation in the 16-year-old patient.12 Although CO2 laser therapy may be a practical treatment option, it posed too many cosmetic concerns in our patient.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an emerging treatment option for NBCCS patients. Itkin and Gilchrest13 treated 2 NBCCS patients with δ-aminolevulinic acid for 1 to 5 hours prior to treatment with blue light therapy. Complete clearance was documented in 89% (8/9) of superficial BCCs and 31% (5/16) of nodular BCCs on the face, indicating that blue light treatment may reduce the cutaneous tumor burden.13 Oseroff et al14 reported similar success in treating 3 children with NBCCS with 20% δ-aminolevulinic acid for 24 hours under occlusion followed by red light treatment. After 1 to 3 treatments, the children had 85% to 98% total clearance, demonstrating it as a viable treatment option in young patients that yields excellent cosmetic results and is well tolerated.14 Photodynamic therapy is reported to have a low risk of carcinogenicity15; however, there has been 1 reported case of melanoma developing at the site of multiple PDT treatments.16 Thus, the risk of carcinogenicity is increasingly bothersome in NBCCS patients due to their sensitivity to exposure. The limited number of studies using topical PDT on pediatric patients, the lack of treatment protocols for pediatric patients, and the need to use general anesthesia for pediatric patients all posed limitations to the use of PDT in our case.

Imiquimod cream 5% was shown in randomized, vehicle-controlled studies to be a safe and effective treatment of superficial BCCs when used 5 days weekly for 6 weeks.17 These studies excluded patients with NBCCS; however, other studies have been completed in patients with NBCCS. Kagy and Amonette18 successfully treated 3 nonfacial BCCs in a patient with NBCCS with imiquimod cream 5% daily for 18 weeks, with complete histologic resolution of the tumors. Micali et al19 also treated 4 patients with NBCCS using imiquimod cream 5% 3 to 5 times weekly for 8 to 14 weeks. Thirteen of 17 BCCs resolved, as confirmed with histologic evaluation.19 One case report revealed a child with NBCCS who was successfully managed with topical fluorouracil and topical tretinoin for more than 10 years.20 Our patient used imiquimod cream 5% 5 times weekly, which inhibited the growth of existing lesions but did not clear them entirely, as they were nodular in nature.

Chemoprevention with oral retinoids breaches a controversial treatment topic. In 1989, a case study of an NBCCS patient treated with surgical excision and oral etretinate for 12 months documented reduction of large tumors.21 A multicenter clinical trial reported that low-dose isotretinoin (10 mg daily) is ineffective in preventing the occurrence of new BCC formation in patients with a history of 2 or more sporadic BCCs.22 Chemoprevention with oral retinoids is well known for being effective for squamous cell carcinomas and actinic keratosis; however, the treatment is less effective for BCCs.22 Most importantly, the extensive side-effect profile and toxicity associated with long-term administration of oral retinoids prohibits many practitioners from routinely using them in pediatric NBCCS patients.

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients are exquisitely sensitive to ionizing radiation and the effects of UV exposure. Therefore, it is essential to emphasize the importance of sun-protective measures such as sun avoidance, broad-spectrum sunscreen use, and sun-protective clothing.

Conclusion

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is a multisystem disorder with a notable predisposition for skin cancer. Our case demonstrates the treatment considerations in a pediatric patient with Fitzpatrick skin type V. Pediatric NBCCS patients develop BCCs at a young age and will continue to develop additional lesions throughout life; therefore, skin preservation is an important consideration when choosing the appropriate treatment regimen. Particularly in our patient, utilizing multiple strategic treatment modalities in combination with chemoprevention moving forward will be a continued management challenge. Strict adherence to a surveillance protocol is encouraged to closely monitor the systemic manifestations of the disorder.

- Gorlin RJ, Goltz R. Multiple nevoid basal cell epitheliomata, jaw cysts, bifid rib-a syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1960;262:908-911.

- Evans DGR, Farndon PA, Burnell LD, et al. The incidence of Gorlin syndrome in 173 consecutive cases of medulloblastoma. Br J Cancer. 1991;64:959-961.

- Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004;6:530-539.

- Farndon PA, Del Mastro RG, Evans DG, et al. Location of gene for Gorlin Syndrome. Lancet. 1992;339:581-582.

- Bale AE, Yu KP. The hedgehog pathway and basal cell carcinomas. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:757-761.

- Evans DGR, Ladusans EJ, Rimmer S, et al. Complications of the naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: results of a population based study. J Med Genet. 1993;30:460-464.

- Kimonis VE, Goldstein AM, Pastakia B, et al. Clinical manifestations in 105 persons with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1997;69:299-308.

- Goldstein AM, Pastakia B, DiGiovanna JJ, et al. Clinical findings in two African-American families with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1994;50:272-281.

- Shanley S, Ratcliffe J, Hockey A, et al. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: review of 118 affected individuals. Am J Med Genet. 1994;50:282-290.

- Bree AF, Shah MR; BCNS Colloquium Group. Consensus statement from the first international colloquium on basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155:2091-2097.

- Doctoroff A, Oberlender SA, Purcell SM. Full-face carbon dioxide laser resurfacing in the management of a patient with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1236-1240.

- Nouri K, Chang A, Trent JT, et al. Ultrapulse CO2 used for the successful treatment of basal cell carcinomas found in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:287-290.

- Itkin A, Gilchrest BA. δ-Aminolevulinic acid and blue light photodynamic therapy for treatment of multiple basal cell carcinomas in two patients with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1054-1061.

- Oseroff AR, Shieh S, Frawley NP, et al. Treatment of diffuse basal cell carcinomas and basaloid follicular hamartomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome by wide-area 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:60-67.

- Morton CA, Brown SB, Collins S, et al. Guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy: report of a workshop of the British Photodermatology Group. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:552-567.

- Wolf P, Fink-Puches R, Reimann-Weber A, et al. Development of malignant melanoma after repeated topical photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid at the exposed site. Dermatology. 1997;194:53-54.

- Geisse J, Caro I, Lindholm J, et al. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: results from two phase III, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:722-733.

- Kagy MK, Amonette R. The use of imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinomas in a basal cell nevus syndrome patient. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:577-579.

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Nasca MR, et al. The use of imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma as observed in Gorlin’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:19-23.

- Strange PR, Lang PG. Long-term management of basal cell nevus syndrome with topical tretinoin and 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:842-845.

- Sanchez-Conejo-Mir J, Camacho F. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: combined etretinate and surgical treatment. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:868-871.

- Tangrea JA, Edwards BK, Taylor PR, et al. Long-term therapy with low-dose isotretinoin for prevention of basal cell carcinoma: a multicenter clinical trial. Isotretinoin-Basal Cell Carcinoma Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:328-332.

In 1960, Gorlin and Goltz1 first described nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) as a distinct clinical entity with multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), jaw cysts, and bifid ribs. This rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis has a minimal prevalence of 1 case per 57,000 individuals2 and no sexual predilection.3 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is caused by a mutation in the human homolog of a Drosophila gene, patched 1 (PTCH1), which is located on chromosome 9q22.3.4,5 The major clinical diagnostic criteria includes multiple BCCs, odontogenic keratocysts, palmar or plantar pits, ectopic calcification of the falx cerebri, and a family history of NBCCS.6 Basal cell carcinoma formation is affected by both skin pigmentation and sun exposure; 80% of white patients with NBCCS will develop at least 1 BCC compared to only 40% of black patients with NBCCS.7 Goldstein et al8 postulated that this disparity is associated with increased skin pigmentation providing UV radiation protection, thus decreasing the tumor burden. We report a case of an 11-year-old black boy with NBCCS to highlight the treatment considerations in pediatric cases of NBCCS.

Case Report

An 11-year-old boy with Fitzpatrick skin type V presented with a history of multiple facial lesions after undergoing excision of large keratocysts from the right maxilla, left maxilla, and right mandible. Physical examination revealed multiple light to dark brown facial papules (Figure 1), palmar and plantar pitting (Figure 2), and frontal bossing.

He was previously diagnosed with autism and his surgical history was notable only for excision of the keratocysts. The patient was not taking any medications and did not have any drug allergies. There was no maternal family history of skin cancer or related syndromes; his paternal family history was unknown. A shave biopsy was performed on a facial papule from the right nasolabial fold. Histopathologic evaluation revealed findings consistent with a pigmented nodular BCC (Figure 3). The patient was subsequently sent for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, which demonstrated calcifications along the tentorium. Genetic consultation confirmed a heterozygous mutation of the PTCH1 gene.

Over the next 12 months, the patient had multiple biopsy-proven pigmented BCCs. Initial management of these carcinomas located on cosmetically sensitive areas, including the upper eyelid and penis, were excised by a pediatric plastic surgeon. A truncal carcinoma was treated with electrodesiccation and curettage, which resulted in keloid formation. Early suspicious lesions were treated with imiquimod cream 5% 5 times weekly in combination with the prophylactic use of tretinoin cream 0.1%. Despite this treatment regimen, the patient continued to demonstrate multiple small clinical pigmented BCCs along the malar surfaces of the cheeks and dorsum of the nose. The patient’s mother deferred chemoprevention with an oral retinoid due to the extensive side-effect profile and long-term necessity of administration.

Management also encompassed BCC surveillance every 4 months; annual digital panorex of the jaw; routine dental screening; routine developmental screening; annual follow-up with a geneticist to ensure multidisciplinary care; and annual vision, hearing, and speech-screening examinations. Strict sun-protective measures were encouraged, including wearing a hat during physical education class.

Comment

Classification and Clinical Presentation

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is a multisystem disorder that requires close monitoring under multidisciplinary care. Evans et al6 defined the diagnostic criteria of NBCCS to require the presence of 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor criteria. The major criteria include multiple BCCs, an odontogenic keratocyst or polyostotic bone cyst, palmar or plantar pits, ectopic calcification of the falx cerebri, and family history of NBCCS. The minor criteria are defined as congenital skeletal anomalies; macrocephaly with frontal bossing; cardiac or ovarian fibromas; medulloblastoma; lymphomesenteric cysts; and congenital malformations such as cleft lip or palate, polydactyly, or eye anomalies.6 The mean age of initial BCC diagnosis is 21 years, with proliferation of cancers between puberty and 35 years of age.7,9 Our case is unique due to the patient’s young age at the time of diagnosis as well as his presentation with multiple BCCs with a darker skin type. Kimonis et al7 reported that approximately 20% of black patients develop their first BCC by the age of 21 years and 40% by 35 years. The presence of multiple BCCs is complicated by the limited treatment options in a pediatric patient. The patient’s inability to withstand multiple procedures contributed to our clinical decision to have multiple lesions removed under general anesthesia by a pediatric plastic surgeon.

Due to the patient’s young age of onset, we placed a great emphasis on close surveillance and management. A management protocol for pediatric patients with NBCCS was described by Bree and Shah; BCNS Colloquium Group10 (eTable). We closely followed this protocol for surveillance; however, we scheduled dermatologic examinations every 4 months due to his extensive history of BCCs.

Management

Our case presents a challenging therapeutic and management dilemma. The management of NBCCS utilizes a multitude of treatment modalities, but many of them posed cosmetic challenges in our patient such as postinflammatory hypopigmentation and the propensity for keloid formation. Although surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery is the standard of treatment of nodular BCCs, we were limited due to the patient’s inability to tolerate multiple surgical procedures without the use of general anesthesia.

Case reports have discussed the use of CO2 laser resurfacing for management of multiple facial BCCs in patients with NBCCS. Doctoroff et al11 treated a patient with 45 facial BCCs with full-face CO2 laser resurfacing, and in a 10-month follow-up period the patient developed 6 new BCCs on the face. Nouri et al12 described 3 cases of multiple BCCs on the face, trunk, and extremities treated with ultrapulse CO2 laser with postoperative Mohs sections verifying complete histologic clearance of tumors. All 3 patients had Fitzpatrick skin type IV; their ages were 2, 16, and 35 years. Local anesthesia was used in the 2-year-old patient and intravenous sedation in the 16-year-old patient.12 Although CO2 laser therapy may be a practical treatment option, it posed too many cosmetic concerns in our patient.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an emerging treatment option for NBCCS patients. Itkin and Gilchrest13 treated 2 NBCCS patients with δ-aminolevulinic acid for 1 to 5 hours prior to treatment with blue light therapy. Complete clearance was documented in 89% (8/9) of superficial BCCs and 31% (5/16) of nodular BCCs on the face, indicating that blue light treatment may reduce the cutaneous tumor burden.13 Oseroff et al14 reported similar success in treating 3 children with NBCCS with 20% δ-aminolevulinic acid for 24 hours under occlusion followed by red light treatment. After 1 to 3 treatments, the children had 85% to 98% total clearance, demonstrating it as a viable treatment option in young patients that yields excellent cosmetic results and is well tolerated.14 Photodynamic therapy is reported to have a low risk of carcinogenicity15; however, there has been 1 reported case of melanoma developing at the site of multiple PDT treatments.16 Thus, the risk of carcinogenicity is increasingly bothersome in NBCCS patients due to their sensitivity to exposure. The limited number of studies using topical PDT on pediatric patients, the lack of treatment protocols for pediatric patients, and the need to use general anesthesia for pediatric patients all posed limitations to the use of PDT in our case.

Imiquimod cream 5% was shown in randomized, vehicle-controlled studies to be a safe and effective treatment of superficial BCCs when used 5 days weekly for 6 weeks.17 These studies excluded patients with NBCCS; however, other studies have been completed in patients with NBCCS. Kagy and Amonette18 successfully treated 3 nonfacial BCCs in a patient with NBCCS with imiquimod cream 5% daily for 18 weeks, with complete histologic resolution of the tumors. Micali et al19 also treated 4 patients with NBCCS using imiquimod cream 5% 3 to 5 times weekly for 8 to 14 weeks. Thirteen of 17 BCCs resolved, as confirmed with histologic evaluation.19 One case report revealed a child with NBCCS who was successfully managed with topical fluorouracil and topical tretinoin for more than 10 years.20 Our patient used imiquimod cream 5% 5 times weekly, which inhibited the growth of existing lesions but did not clear them entirely, as they were nodular in nature.

Chemoprevention with oral retinoids breaches a controversial treatment topic. In 1989, a case study of an NBCCS patient treated with surgical excision and oral etretinate for 12 months documented reduction of large tumors.21 A multicenter clinical trial reported that low-dose isotretinoin (10 mg daily) is ineffective in preventing the occurrence of new BCC formation in patients with a history of 2 or more sporadic BCCs.22 Chemoprevention with oral retinoids is well known for being effective for squamous cell carcinomas and actinic keratosis; however, the treatment is less effective for BCCs.22 Most importantly, the extensive side-effect profile and toxicity associated with long-term administration of oral retinoids prohibits many practitioners from routinely using them in pediatric NBCCS patients.

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients are exquisitely sensitive to ionizing radiation and the effects of UV exposure. Therefore, it is essential to emphasize the importance of sun-protective measures such as sun avoidance, broad-spectrum sunscreen use, and sun-protective clothing.

Conclusion

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is a multisystem disorder with a notable predisposition for skin cancer. Our case demonstrates the treatment considerations in a pediatric patient with Fitzpatrick skin type V. Pediatric NBCCS patients develop BCCs at a young age and will continue to develop additional lesions throughout life; therefore, skin preservation is an important consideration when choosing the appropriate treatment regimen. Particularly in our patient, utilizing multiple strategic treatment modalities in combination with chemoprevention moving forward will be a continued management challenge. Strict adherence to a surveillance protocol is encouraged to closely monitor the systemic manifestations of the disorder.