User login

Purpuric Bullae on the Lower Extremities

The Diagnosis: Bullous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

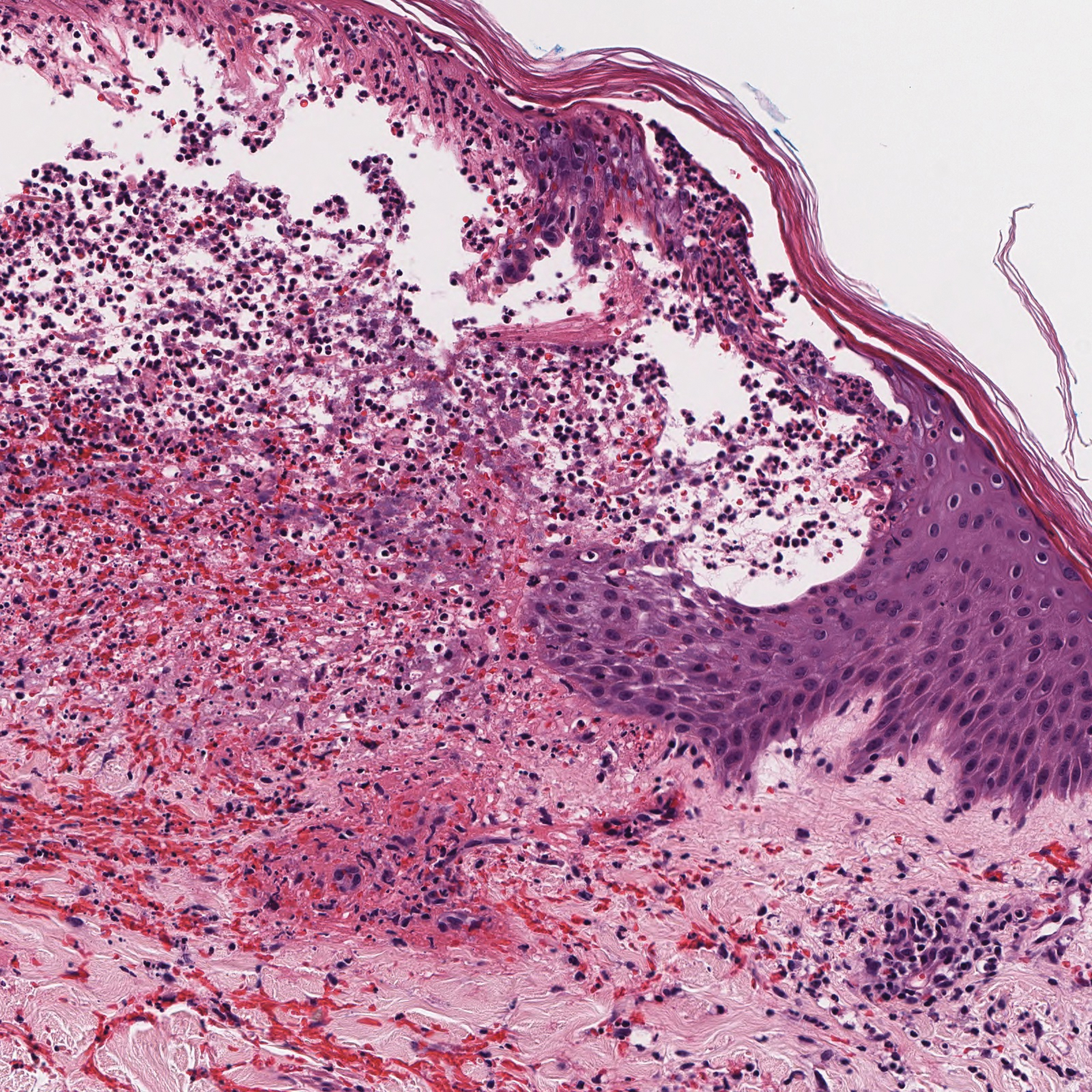

Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showed a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, karyorrhexis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrin deposition in the vessel wall (quiz images). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed fibrin surrounding the vasculature, consistent with vasculitis. The clinical and histopathological evaluation supported the diagnosis of bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). The patient had a full LCV workup including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and C3/C4/total complement level, which were all within reference range. The patient denied that she had taken any medications prior to the onset of the rash. She was started on a 12-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, and the rash resolved in 1 week.

Although the incidence of LCV is estimated to be 30 cases per million individuals per year,1 bullous LCV is a rarer entity with only a few cases reported in the literature.2,3 As in our patient's case, up to 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic or the etiology cannot be determined despite laboratory workup and medication review. Other cases can be secondary to medication, infection, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy.3 Despite the exact pathogenesis of bullous LCV being unknown,4 it likely is related to a type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules leading to endothelial injury, activation of the complement cascade, and development of intraepidermal or subepidermal blister formation depending on location of inflammation and edema.2 Clinically, an intraepidermal split would be more flaccid, similar to pemphigus vulgaris, while a subepidermal split, as in our patient, would be taut bullae. The subepidermal split more commonly is seen in bullous LCV.2

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis on H&E staining characteristically has a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic fragments called leukocytoclasis, and blood extravasation.3 Extravasated blood presents clinically as petechiae. In this case, the petechiae helped distinguish this entity from the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, DIF would be helpful in distinguishing bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris from LCV.2 Direct immunofluorescence in bullous LCV would have fibrinogen surrounding the vasculature without C3 and IgG deposition (intraepidermal or subepidermal).

Mild cases of LCV often resolve with supportive measures including elevation of the legs, ice packs applied to the affected area, and removal of the inciting drug or event.4 In the few cases reported in the literature, bullous LCV presented more diffusely than classic LCV with bullous lesions on the forearms and the lower extremities. Oral steroids are efficacious for extensive bullous LCV.4

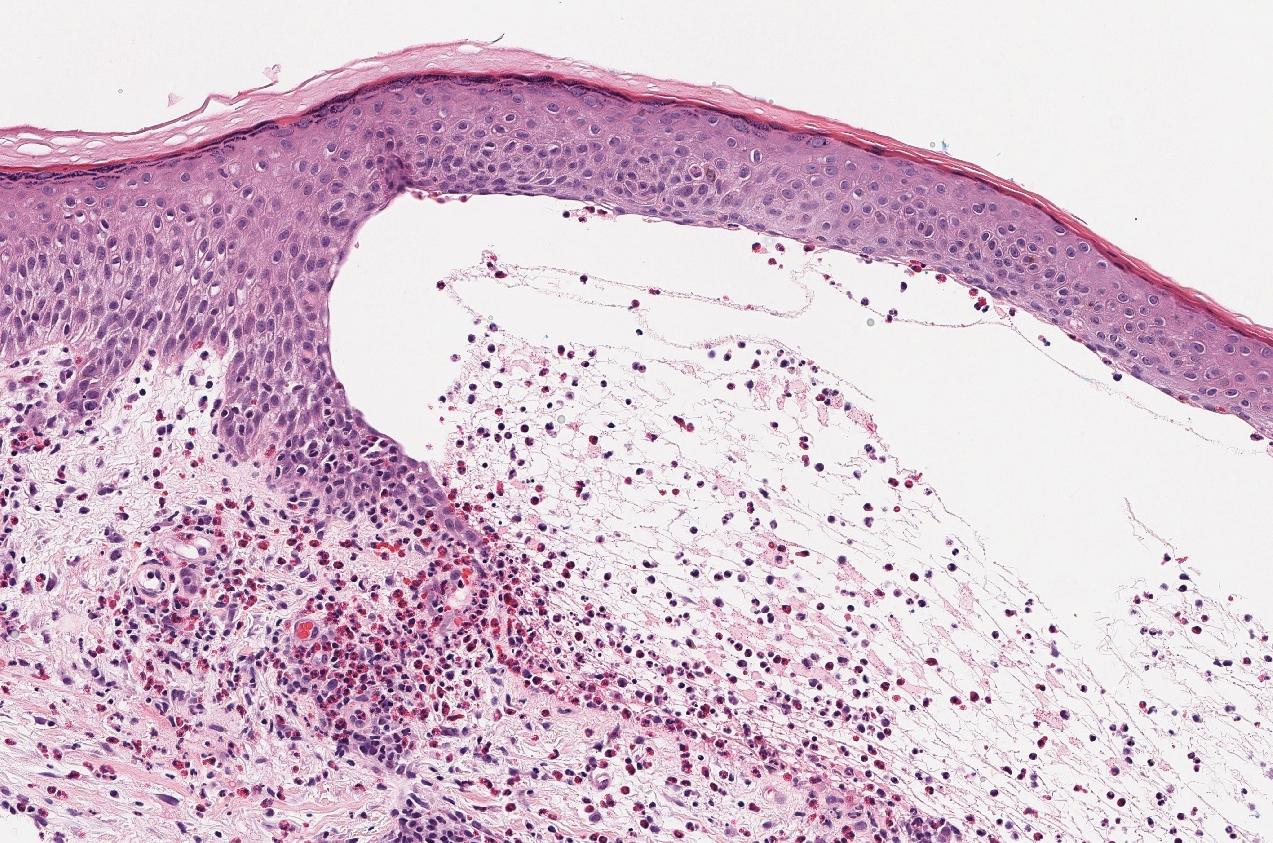

The differential diagnosis of bullous LCV includes bullous diseases with subepidermal split including BP and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease typically affecting patients older than 60 years.5 The pathogenesis of BP is related to development of autoantibodies directed against hemidesmosome components, bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG) 1 or BPAG2.5 Bullous pemphigoid presents clinically as widespread, generally pruritic, erythematous, urticarial plaques with bullae. Histologically, BP characteristically has a subepidermal split with superficial dermal edema and eosinophils at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence confirms the diagnosis with IgG and C3 deposition in an n-serrated pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.6 Bullous pemphigoid can be distinguished from bullous LCV by the older age of presentation, DIF findings, and the absence of purpura.

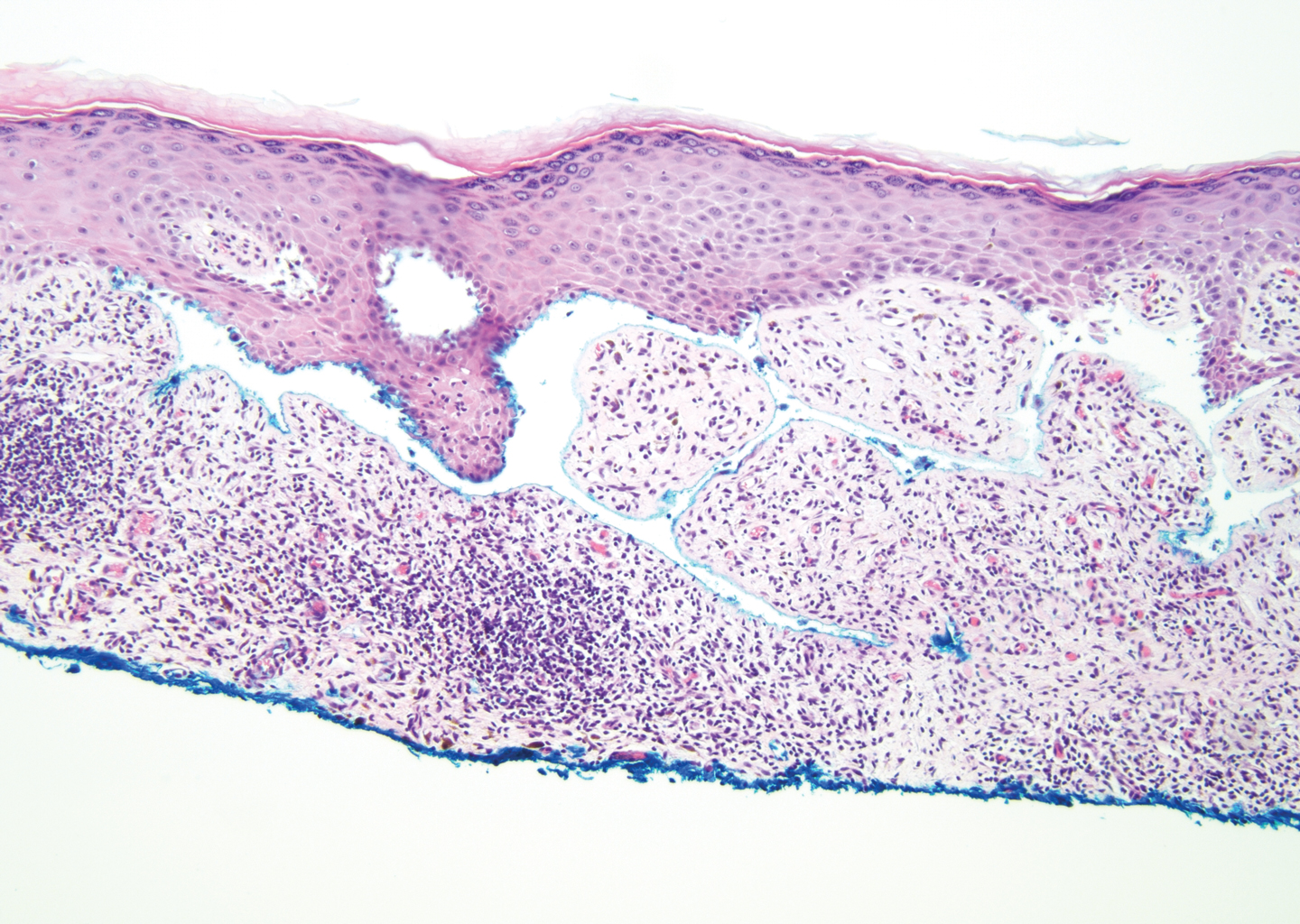

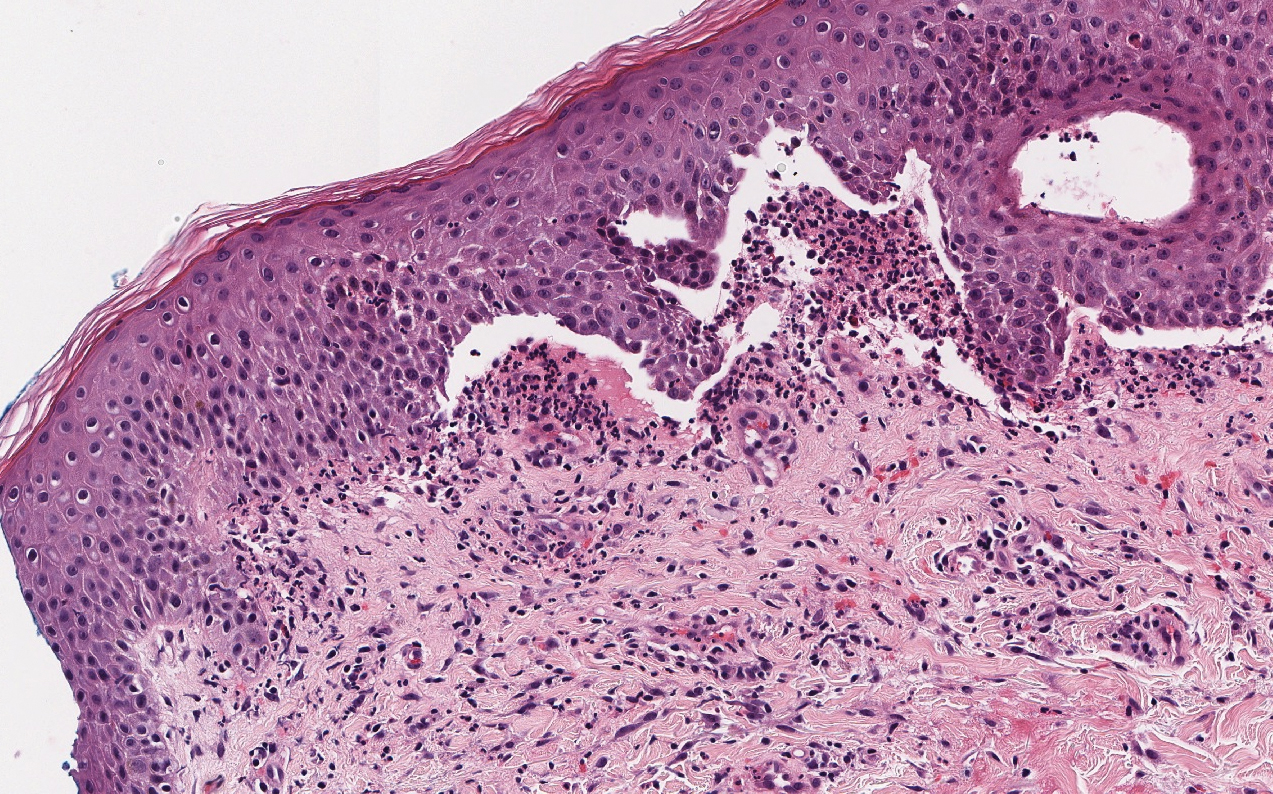

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis represents a rare subepidermal vesiculobullous disease occurring in patients in their 60s.7 Clinically, this entity presents as tense bullae often located on the periphery of an urticarial plaque, classically called the "string of pearls sign." Histologically, LABD also presents with subepidermal split; however, neutrophils are the predominant cell type vs eosinophils in BP (Figure 2).7 Direct immunofluorescence is specific with a linear deposition of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis most commonly is induced by vancomycin. Unlike bullous LCV, the bullae of LABD have an annular peripheral pattern on an erythematous base and lack purpura.

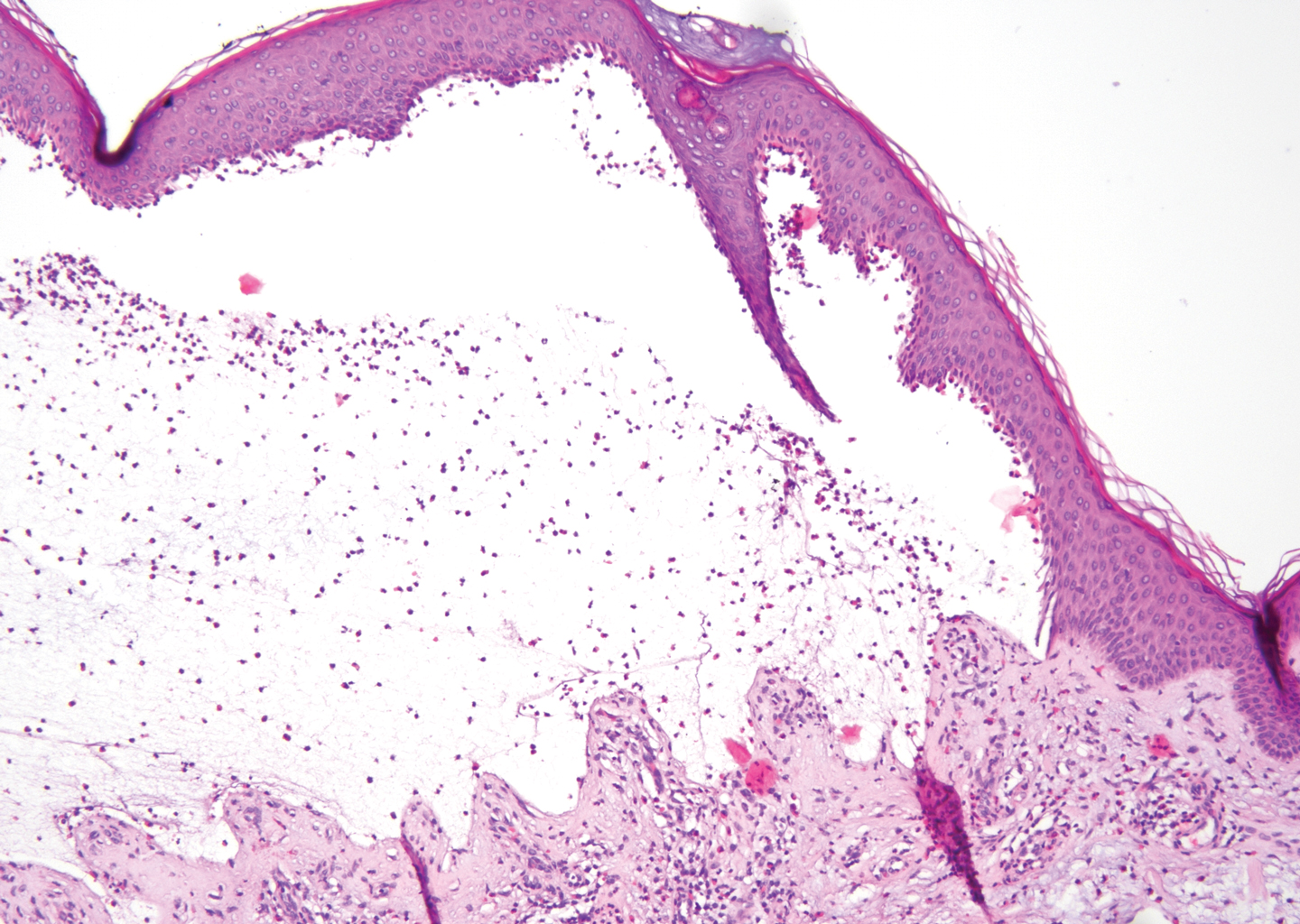

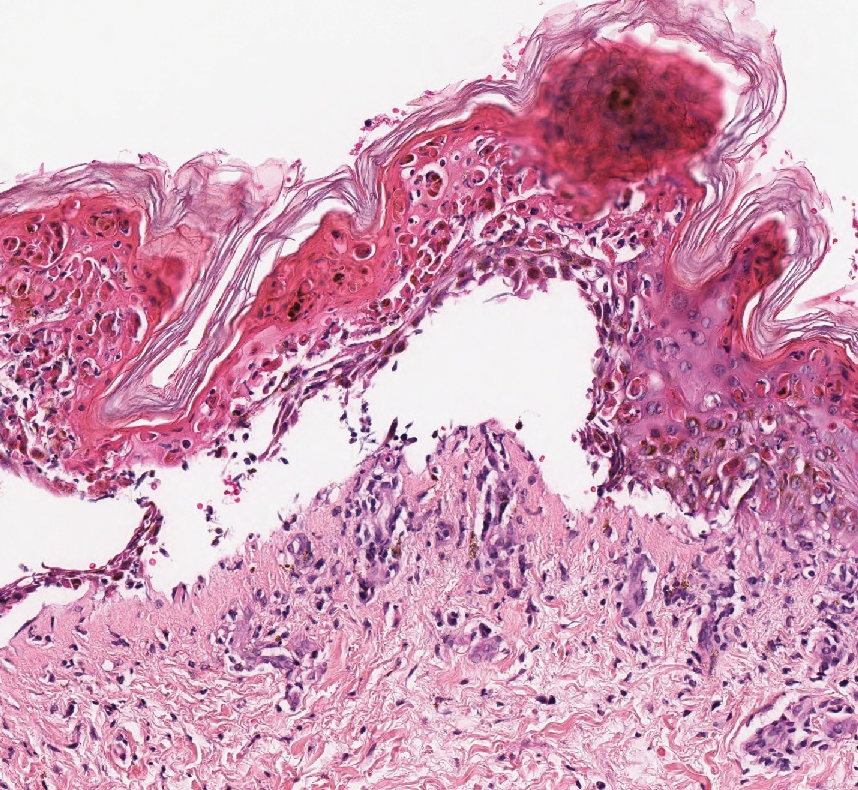

Stasis dermatitis is inflammation of the dermis due to venous insufficiency that often is present in the bilateral lower extremities. The disorder affects approximately 7% of adults older than 50 years, but it also can occur in younger patients.8 The pathophysiology of stasis dermatitis is caused by edema, which leads to extracellular fluid, plasma proteins, macrophages, and erythrocytes passing into the interstitial space. Patients with stasis dermatitis present with scaly erythematous papules and plaques or edematous blisters on the lower extremities. Diagnosis usually can be made clinically; however, a skin biopsy also can be helpful. Hematoxylin and eosin shows a pauci-inflammatory subepidermal bulla with fibrin (Figure 3).8 The overlying epidermis is intact. The dermis has cannon ball angiomatosis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrosis typical of stasis dermatitis. Stasis dermatitis with bullae is cell poor and lacks the perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and neutrophilic fragments that often are present in LCV, making the 2 entities distinguishable.

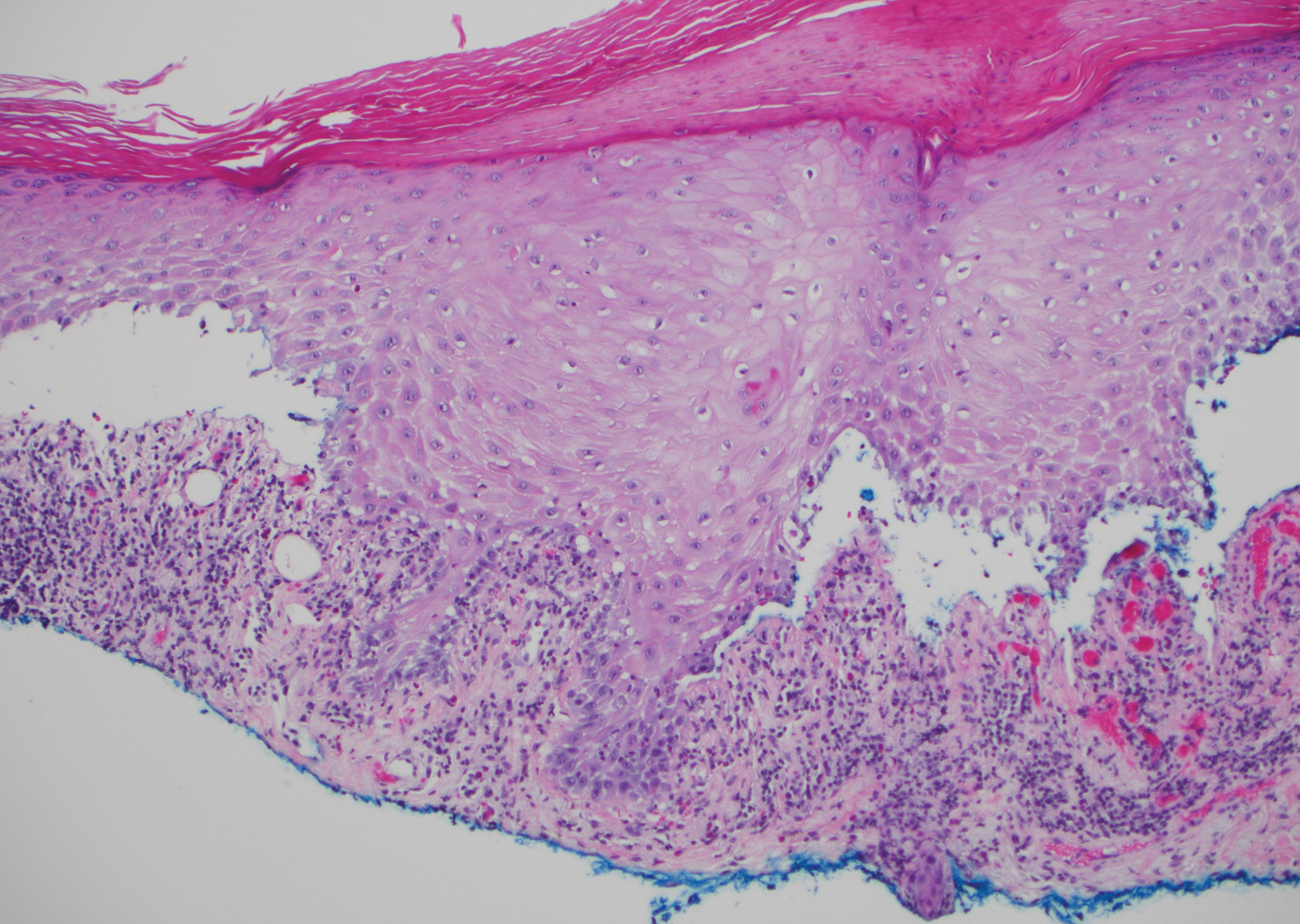

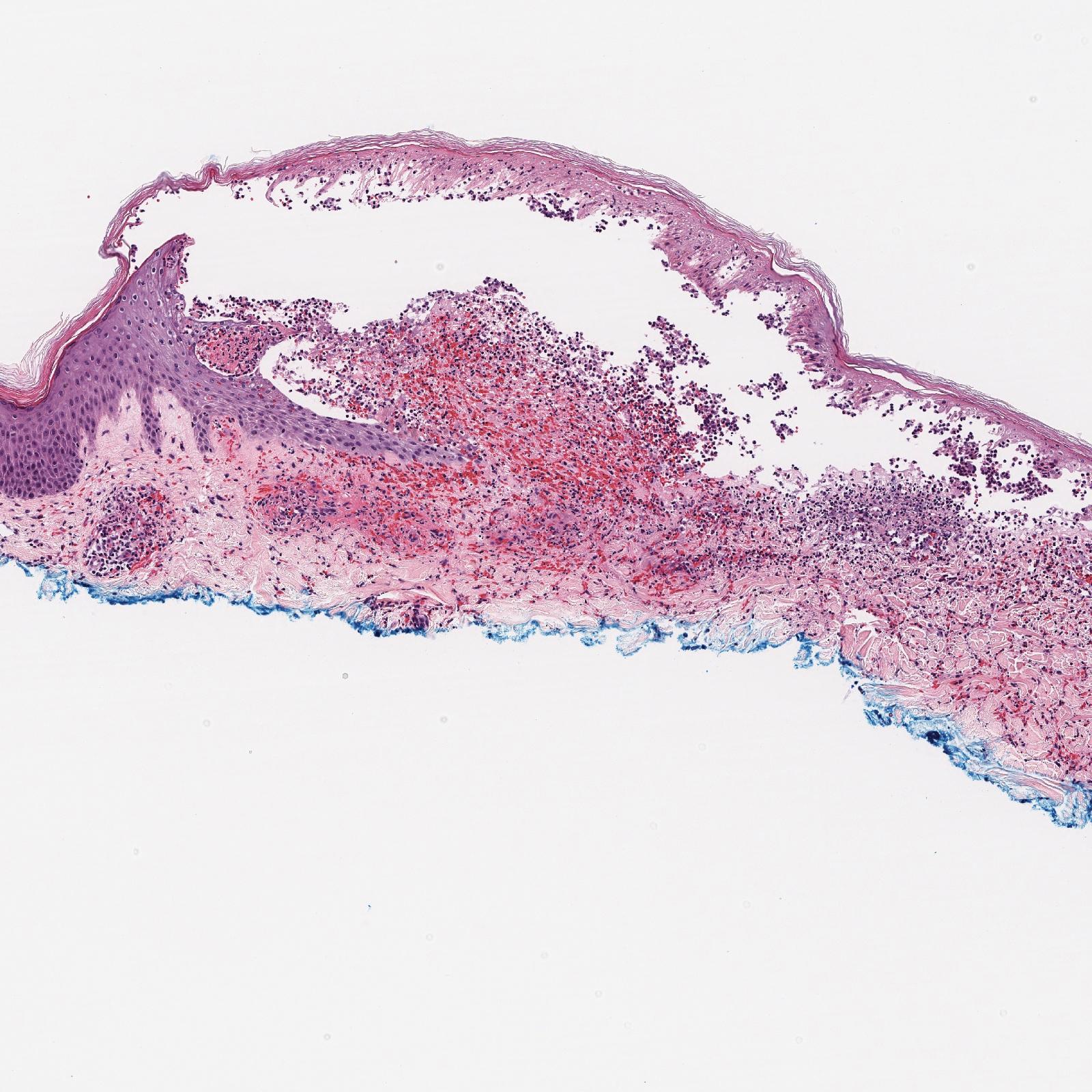

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) lies on a spectrum of severe cutaneous drug reactions involving the skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous involvement typically begins on the trunk and face and later can involve the palms and soles.9 Similar drugs have been implicated in bullous LCV and SJS/TEN, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Histologically, SJS/TEN has full-thickness epidermal necrolysis, vacuolar interface, and keratinocyte apoptosis (Figure 4).9 The clinical presentation of sloughing of skin with positive Nikolsky sign, oral involvement, and H&E and DIF findings can help differentiate this entity from bullous LCV.

- Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19:77-78.

- Davidson KA, Ringpfeil F, Lee JB. Ibuprofen-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2001;67:303-307.

- Lazic T, Fonder M, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Orlistat-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2013;91:148-149.

- Mericliler M, Shnawa A, Al-Qaysi D, et al. Oxacillin-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. IDCases. 2019;17:E00539.

- Bernard P, Antonicelli F. Bullous pemphigoid: a review of its diagnosis, associations and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:513-528.

- High WA. Blistering disorders. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:161-171.

- Visentainer L, Massuda JY, Cintra ML, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD)--an atypical presentation. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1091-1093.

- Hyman DA, Cohen PR. Stasis dermatitis as a complication of recurrent levofloxacin-associated bilateral leg edema. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20399.

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showed a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, karyorrhexis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrin deposition in the vessel wall (quiz images). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed fibrin surrounding the vasculature, consistent with vasculitis. The clinical and histopathological evaluation supported the diagnosis of bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). The patient had a full LCV workup including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and C3/C4/total complement level, which were all within reference range. The patient denied that she had taken any medications prior to the onset of the rash. She was started on a 12-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, and the rash resolved in 1 week.

Although the incidence of LCV is estimated to be 30 cases per million individuals per year,1 bullous LCV is a rarer entity with only a few cases reported in the literature.2,3 As in our patient's case, up to 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic or the etiology cannot be determined despite laboratory workup and medication review. Other cases can be secondary to medication, infection, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy.3 Despite the exact pathogenesis of bullous LCV being unknown,4 it likely is related to a type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules leading to endothelial injury, activation of the complement cascade, and development of intraepidermal or subepidermal blister formation depending on location of inflammation and edema.2 Clinically, an intraepidermal split would be more flaccid, similar to pemphigus vulgaris, while a subepidermal split, as in our patient, would be taut bullae. The subepidermal split more commonly is seen in bullous LCV.2

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis on H&E staining characteristically has a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic fragments called leukocytoclasis, and blood extravasation.3 Extravasated blood presents clinically as petechiae. In this case, the petechiae helped distinguish this entity from the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, DIF would be helpful in distinguishing bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris from LCV.2 Direct immunofluorescence in bullous LCV would have fibrinogen surrounding the vasculature without C3 and IgG deposition (intraepidermal or subepidermal).

Mild cases of LCV often resolve with supportive measures including elevation of the legs, ice packs applied to the affected area, and removal of the inciting drug or event.4 In the few cases reported in the literature, bullous LCV presented more diffusely than classic LCV with bullous lesions on the forearms and the lower extremities. Oral steroids are efficacious for extensive bullous LCV.4

The differential diagnosis of bullous LCV includes bullous diseases with subepidermal split including BP and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease typically affecting patients older than 60 years.5 The pathogenesis of BP is related to development of autoantibodies directed against hemidesmosome components, bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG) 1 or BPAG2.5 Bullous pemphigoid presents clinically as widespread, generally pruritic, erythematous, urticarial plaques with bullae. Histologically, BP characteristically has a subepidermal split with superficial dermal edema and eosinophils at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence confirms the diagnosis with IgG and C3 deposition in an n-serrated pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.6 Bullous pemphigoid can be distinguished from bullous LCV by the older age of presentation, DIF findings, and the absence of purpura.

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis represents a rare subepidermal vesiculobullous disease occurring in patients in their 60s.7 Clinically, this entity presents as tense bullae often located on the periphery of an urticarial plaque, classically called the "string of pearls sign." Histologically, LABD also presents with subepidermal split; however, neutrophils are the predominant cell type vs eosinophils in BP (Figure 2).7 Direct immunofluorescence is specific with a linear deposition of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis most commonly is induced by vancomycin. Unlike bullous LCV, the bullae of LABD have an annular peripheral pattern on an erythematous base and lack purpura.

Stasis dermatitis is inflammation of the dermis due to venous insufficiency that often is present in the bilateral lower extremities. The disorder affects approximately 7% of adults older than 50 years, but it also can occur in younger patients.8 The pathophysiology of stasis dermatitis is caused by edema, which leads to extracellular fluid, plasma proteins, macrophages, and erythrocytes passing into the interstitial space. Patients with stasis dermatitis present with scaly erythematous papules and plaques or edematous blisters on the lower extremities. Diagnosis usually can be made clinically; however, a skin biopsy also can be helpful. Hematoxylin and eosin shows a pauci-inflammatory subepidermal bulla with fibrin (Figure 3).8 The overlying epidermis is intact. The dermis has cannon ball angiomatosis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrosis typical of stasis dermatitis. Stasis dermatitis with bullae is cell poor and lacks the perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and neutrophilic fragments that often are present in LCV, making the 2 entities distinguishable.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) lies on a spectrum of severe cutaneous drug reactions involving the skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous involvement typically begins on the trunk and face and later can involve the palms and soles.9 Similar drugs have been implicated in bullous LCV and SJS/TEN, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Histologically, SJS/TEN has full-thickness epidermal necrolysis, vacuolar interface, and keratinocyte apoptosis (Figure 4).9 The clinical presentation of sloughing of skin with positive Nikolsky sign, oral involvement, and H&E and DIF findings can help differentiate this entity from bullous LCV.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showed a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, karyorrhexis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrin deposition in the vessel wall (quiz images). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed fibrin surrounding the vasculature, consistent with vasculitis. The clinical and histopathological evaluation supported the diagnosis of bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). The patient had a full LCV workup including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B and hepatitis C screening, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and C3/C4/total complement level, which were all within reference range. The patient denied that she had taken any medications prior to the onset of the rash. She was started on a 12-day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, and the rash resolved in 1 week.

Although the incidence of LCV is estimated to be 30 cases per million individuals per year,1 bullous LCV is a rarer entity with only a few cases reported in the literature.2,3 As in our patient's case, up to 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic or the etiology cannot be determined despite laboratory workup and medication review. Other cases can be secondary to medication, infection, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy.3 Despite the exact pathogenesis of bullous LCV being unknown,4 it likely is related to a type III hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules leading to endothelial injury, activation of the complement cascade, and development of intraepidermal or subepidermal blister formation depending on location of inflammation and edema.2 Clinically, an intraepidermal split would be more flaccid, similar to pemphigus vulgaris, while a subepidermal split, as in our patient, would be taut bullae. The subepidermal split more commonly is seen in bullous LCV.2

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis on H&E staining characteristically has a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic fragments called leukocytoclasis, and blood extravasation.3 Extravasated blood presents clinically as petechiae. In this case, the petechiae helped distinguish this entity from the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, DIF would be helpful in distinguishing bullous diseases such as bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris from LCV.2 Direct immunofluorescence in bullous LCV would have fibrinogen surrounding the vasculature without C3 and IgG deposition (intraepidermal or subepidermal).

Mild cases of LCV often resolve with supportive measures including elevation of the legs, ice packs applied to the affected area, and removal of the inciting drug or event.4 In the few cases reported in the literature, bullous LCV presented more diffusely than classic LCV with bullous lesions on the forearms and the lower extremities. Oral steroids are efficacious for extensive bullous LCV.4

The differential diagnosis of bullous LCV includes bullous diseases with subepidermal split including BP and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease typically affecting patients older than 60 years.5 The pathogenesis of BP is related to development of autoantibodies directed against hemidesmosome components, bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG) 1 or BPAG2.5 Bullous pemphigoid presents clinically as widespread, generally pruritic, erythematous, urticarial plaques with bullae. Histologically, BP characteristically has a subepidermal split with superficial dermal edema and eosinophils at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence confirms the diagnosis with IgG and C3 deposition in an n-serrated pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.6 Bullous pemphigoid can be distinguished from bullous LCV by the older age of presentation, DIF findings, and the absence of purpura.

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis represents a rare subepidermal vesiculobullous disease occurring in patients in their 60s.7 Clinically, this entity presents as tense bullae often located on the periphery of an urticarial plaque, classically called the "string of pearls sign." Histologically, LABD also presents with subepidermal split; however, neutrophils are the predominant cell type vs eosinophils in BP (Figure 2).7 Direct immunofluorescence is specific with a linear deposition of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis most commonly is induced by vancomycin. Unlike bullous LCV, the bullae of LABD have an annular peripheral pattern on an erythematous base and lack purpura.

Stasis dermatitis is inflammation of the dermis due to venous insufficiency that often is present in the bilateral lower extremities. The disorder affects approximately 7% of adults older than 50 years, but it also can occur in younger patients.8 The pathophysiology of stasis dermatitis is caused by edema, which leads to extracellular fluid, plasma proteins, macrophages, and erythrocytes passing into the interstitial space. Patients with stasis dermatitis present with scaly erythematous papules and plaques or edematous blisters on the lower extremities. Diagnosis usually can be made clinically; however, a skin biopsy also can be helpful. Hematoxylin and eosin shows a pauci-inflammatory subepidermal bulla with fibrin (Figure 3).8 The overlying epidermis is intact. The dermis has cannon ball angiomatosis, red blood cell extravasation, and fibrosis typical of stasis dermatitis. Stasis dermatitis with bullae is cell poor and lacks the perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and neutrophilic fragments that often are present in LCV, making the 2 entities distinguishable.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) lies on a spectrum of severe cutaneous drug reactions involving the skin and mucous membranes. Cutaneous involvement typically begins on the trunk and face and later can involve the palms and soles.9 Similar drugs have been implicated in bullous LCV and SJS/TEN, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Histologically, SJS/TEN has full-thickness epidermal necrolysis, vacuolar interface, and keratinocyte apoptosis (Figure 4).9 The clinical presentation of sloughing of skin with positive Nikolsky sign, oral involvement, and H&E and DIF findings can help differentiate this entity from bullous LCV.

- Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19:77-78.

- Davidson KA, Ringpfeil F, Lee JB. Ibuprofen-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2001;67:303-307.

- Lazic T, Fonder M, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Orlistat-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2013;91:148-149.

- Mericliler M, Shnawa A, Al-Qaysi D, et al. Oxacillin-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. IDCases. 2019;17:E00539.

- Bernard P, Antonicelli F. Bullous pemphigoid: a review of its diagnosis, associations and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:513-528.

- High WA. Blistering disorders. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:161-171.

- Visentainer L, Massuda JY, Cintra ML, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD)--an atypical presentation. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1091-1093.

- Hyman DA, Cohen PR. Stasis dermatitis as a complication of recurrent levofloxacin-associated bilateral leg edema. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20399.

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39.

- Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19:77-78.

- Davidson KA, Ringpfeil F, Lee JB. Ibuprofen-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2001;67:303-307.

- Lazic T, Fonder M, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Orlistat-induced bullous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Cutis. 2013;91:148-149.

- Mericliler M, Shnawa A, Al-Qaysi D, et al. Oxacillin-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. IDCases. 2019;17:E00539.

- Bernard P, Antonicelli F. Bullous pemphigoid: a review of its diagnosis, associations and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:513-528.

- High WA. Blistering disorders. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:161-171.

- Visentainer L, Massuda JY, Cintra ML, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD)--an atypical presentation. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1091-1093.

- Hyman DA, Cohen PR. Stasis dermatitis as a complication of recurrent levofloxacin-associated bilateral leg edema. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20399.

- Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39.

A 30-year-old woman with a medical history of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus and morbid obesity presented to the dermatology clinic with a painful blistering rash on the lower extremities with scattered red-purple papules of 1 week's duration. The rash began on the left dorsal foot. Physical examination showed nonblanching, 2- to 4-mm, violaceous papules with numerous vesiculopustular bullae on the lower extremities from the dorsal feet to the proximal knee. A shave biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin stain and a punch biopsy for direct immunofluorescence were performed.

Distinct Violaceous Plaques in Conjunction With Blisters

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

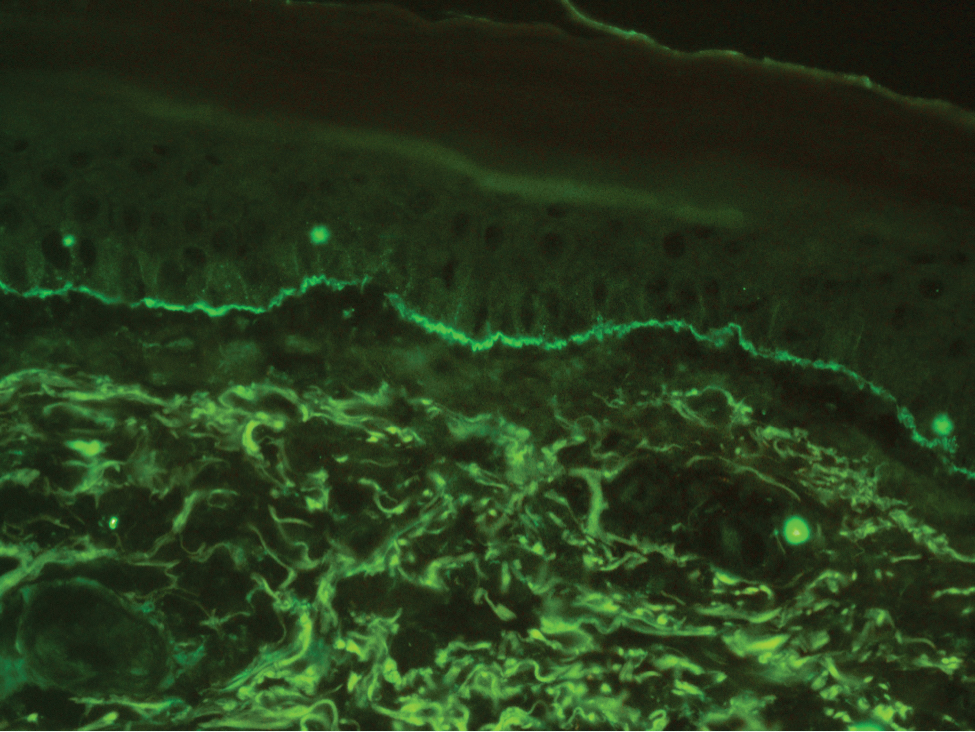

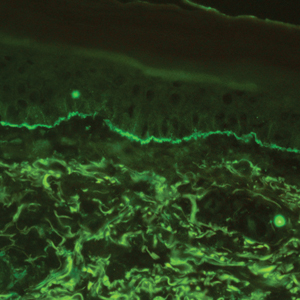

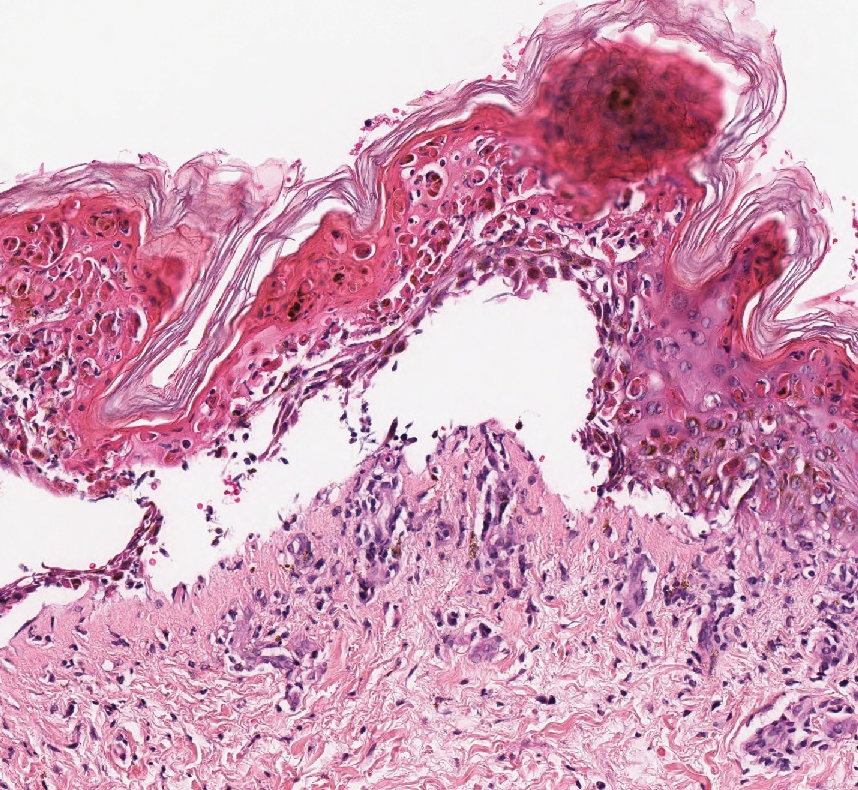

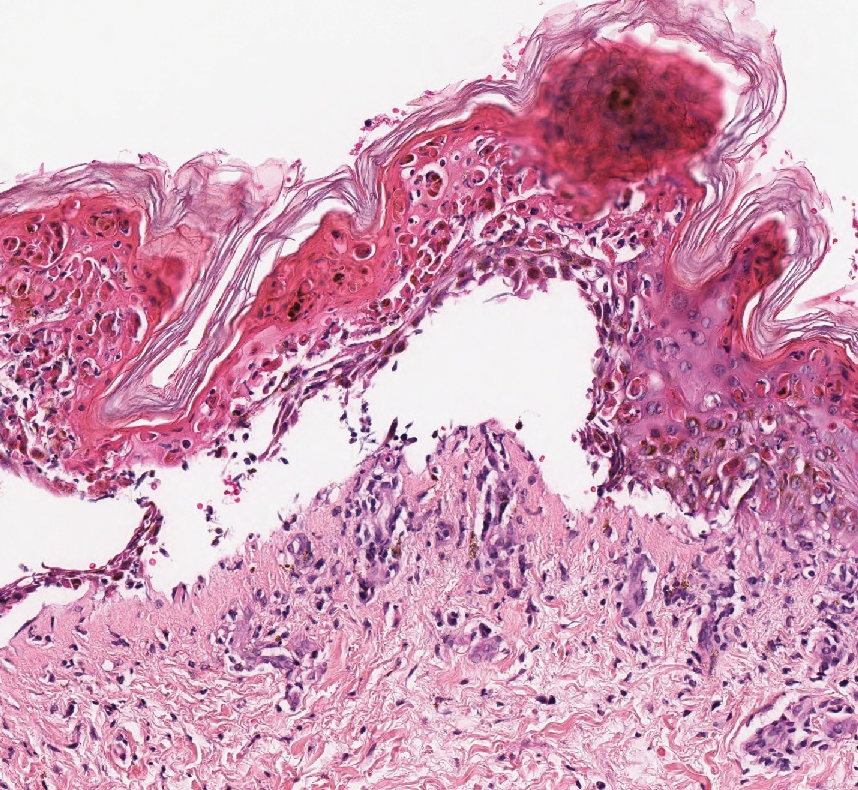

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

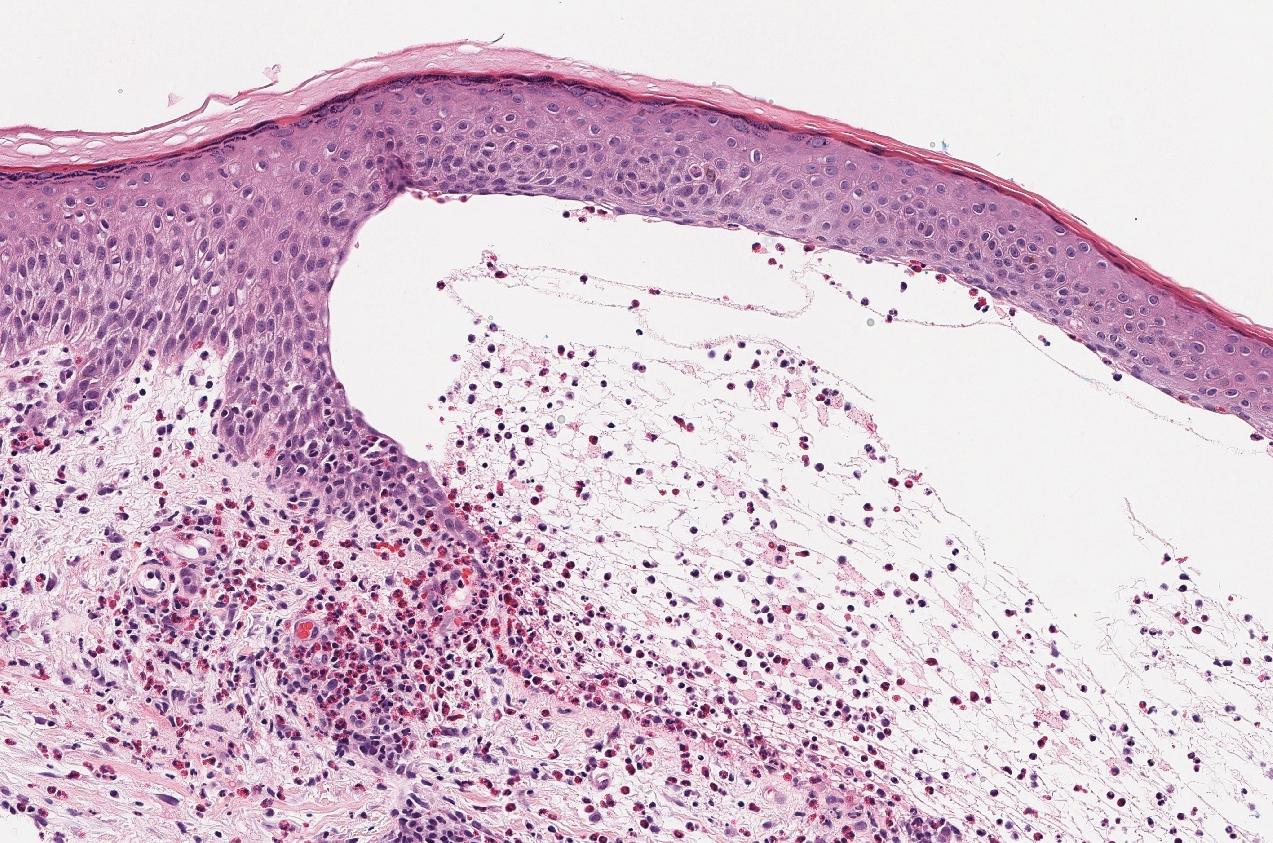

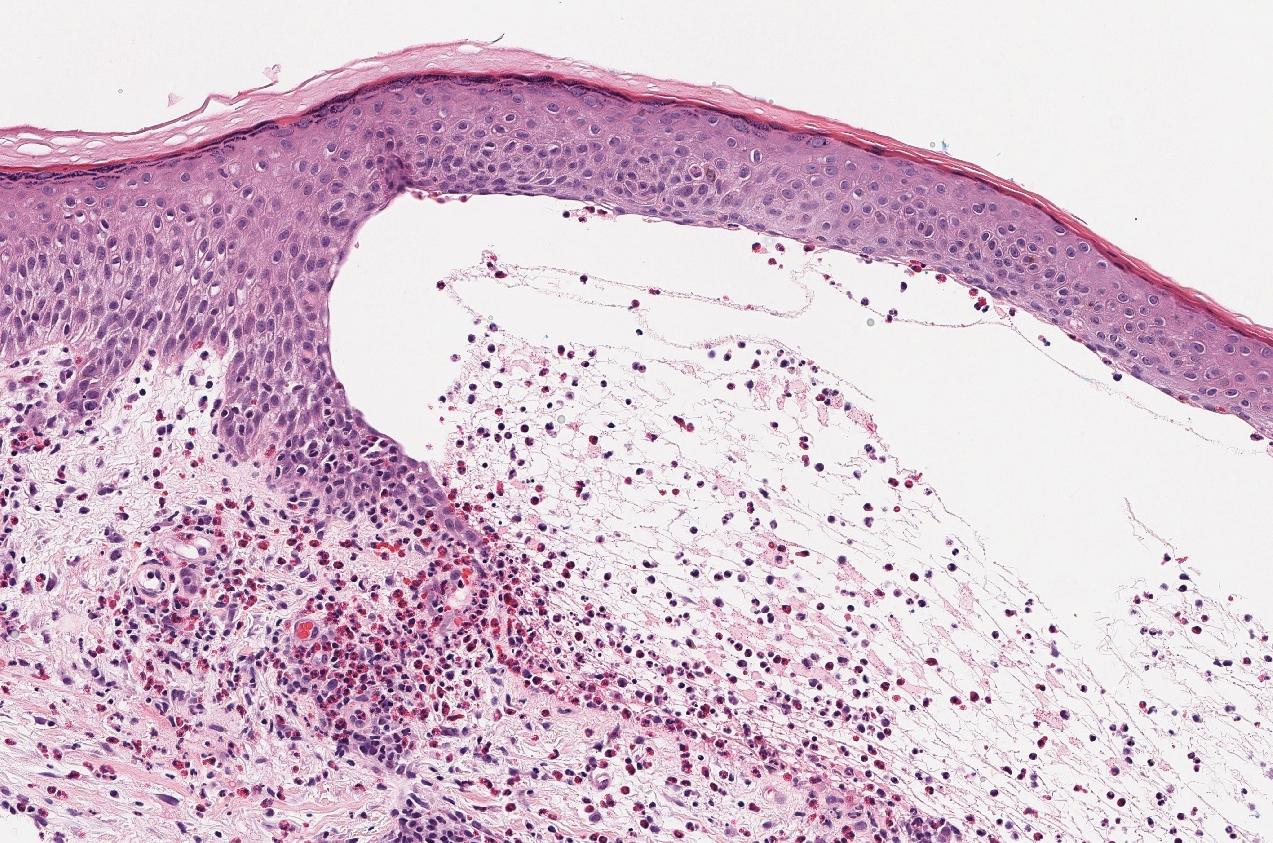

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

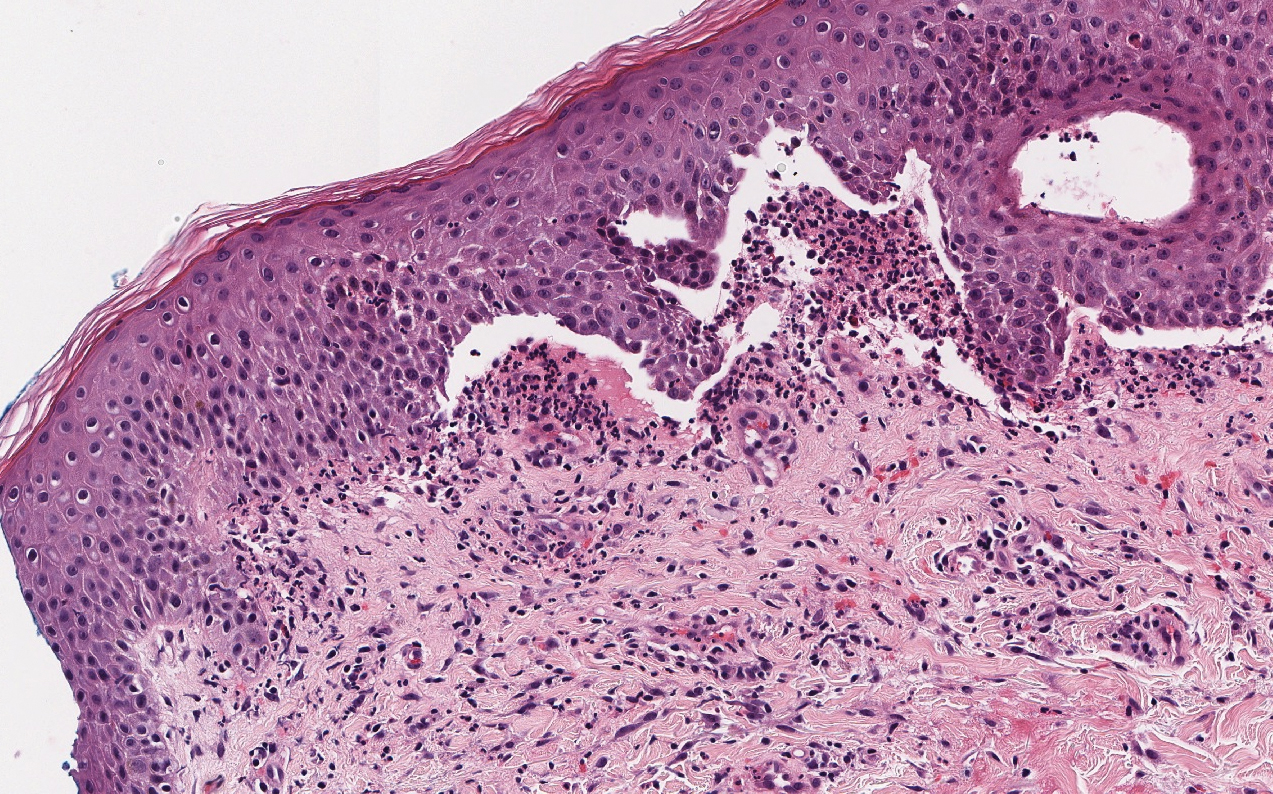

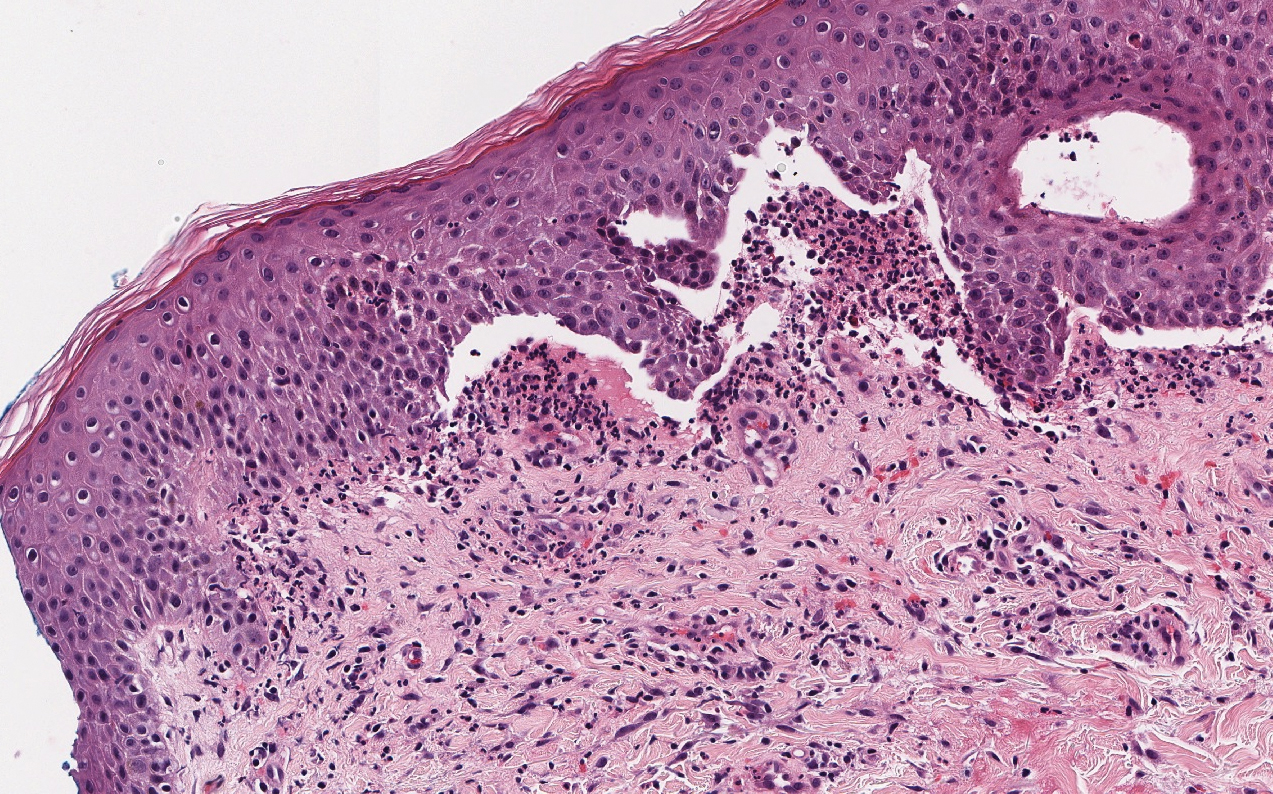

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash of several months' duration that began as itchy bumps on the wrists and spread to involve the legs. Approximately 2 months prior to presentation, she noted blisters on the feet and legs. She initially went to her primary care physician, who prescribed levofloxacin, cephalexin, and a 5-day course of prednisone. The prednisone initially helped; however the rash worsened on discontinuation. In our clinic, the patient had scattered tense bullae and numerous erosions with crust on the dorsum of the feet and legs, some of which were in conjunction with violaceous papules and plaques. There also was hypertrophic scale on the soles of the feet. A potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from the feet was negative for fungal elements. Two shave biopsies of a violaceous plaque and bulla as well as a perilesional punch biopsy from the leg were obtained.

Blanchable Erythematous Patches on the Fingers

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

The diagnosis of irritant contact dermatitis secondary to skateboarding is similar to pool palms, a benign, self-limiting irritant contact dermatitis.1 We propose that contact with concrete surfaces during skateboarding can lead to a presentation similar to pool palms. In our case, it was likely that the finger pulpitis noted in the physical examination was due to daily skateboarding rather than once-weekly swimming. Furthermore, the fingertip contact with concrete in pool palms is similar to the rough surface exposure on the skateboard.

Pool palms is more commonly reported in children due to their participation in sports and other activities with recent exposure to rough surfaces, most commonly the floor of swimming pools.2 The condition resolves after eliminating exposures.3 The frequency and duration of exposure to rough surfaces in swimming pools leading to development of this condition is unknown.

There have been mixed reports on the pathogenesis of pool palms. Some literature supports the idea that it is a wet dermatitis, a combination of prolonged water contact, friction, chemicals, and microbes leading to a chronic dermatitis. This theory states that the primary factor influencing the development of erythematous patches on the fingers, palms, and soles is the hyperhydration of the corneal layer at these sites.4 A different theory attributes pool palms to a mechanical origin, such as repeated microtrauma from contact with the rough concrete surfaces of swimming pools.5 This theory further states that the chemicals in pool water, such as chlorine and sodium hypochlorite, rarely produce irritant, allergic, or urticarial reactions.3

Based on these theories, we hypothesized that fingertip pulpitis can result from activities other than swimming (eg, skateboarding). Our case supports the latter theory on fingertip pulpitis in pool palms being a result of frictional dermatitis rather than wet dermatitis because we attributed our patient’s findings to contact with rough surfaces during skateboarding. Although the patient did swim, he only did so once weekly in the summer months, and the lesions had been persistent for 2 years consistently. His skateboarding hobby was more frequent, and he endorsed contact of the pads of the bilateral second to fifth fingers to the rough surfaces of the road and skateboard. The patient did not have lesions on the toes, further supporting the hypothesis that skateboarding led to the current presentation.

In children, hand-foot-and-mouth disease classically presents with oval-shaped, erythematous vesicles on the palmar surfaces of the hands and feet and generally is accompanied by fever and sore throat.6 Furthermore, unlike in our case, the viral exanthem usually would be present for up to 3 weeks and would not persist for more than 2 years. Erythema multiforme has an erythematous color and can present on the palms; however, the lesions have a classic targetoid appearance. It would be unique for erythema multiforme to present only on the fingertips rather than more diffusely on the palms or in other areas such as the face.7 Limited cutaneous sclerosis (scleroderma) initially can present with edematous pitted scars on the digital tips; however, with time the fingers will have a taut, white, shiny appearance that can develop into contractures and debilitating ulcerations.8 In our patient, the plaques did not advance to any further disease. Lastly, in contrast to our patient, punctate palmoplantar keratoderma presents as hyperkeratotic, firm, translucent, or opaque papules on the palms and soles. Over time, the papules can appear verrucous or callouslike.9 In our case, the plaques on the fingertips were erythematous rather than translucent or opaque papules.

Our case raises questions on whether prior reports of pool palms can be attributed to other activities involving contact with rough surfaces. More research is needed on the frequency and duration of rough surface exposure resulting in fingertip pulpitis.

- Lopez-Neyra A, Vano-Galvan S, Alvarez-Twose I, et al. Pool palms [in Spanish]. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

- Wong LC, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95.

- Mandojana RM. Pool palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2 pt 1):280-281.

- Novoa A, Klear S. Pool palms [published online September 30, 2015]. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:41.

- Martín JM, Martín JM, Ricart JM. Erythematous-violaceous lesions on the palms [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:507-508.

- Marcini AJ, Shani-Adir A. Other viral diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:1345-1366.

- French LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrosis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:319-334.

- Connoly MK. Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) and related disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:643-646.

- Krol AL, Siegel D. Keratodermas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:871-886.

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

The diagnosis of irritant contact dermatitis secondary to skateboarding is similar to pool palms, a benign, self-limiting irritant contact dermatitis.1 We propose that contact with concrete surfaces during skateboarding can lead to a presentation similar to pool palms. In our case, it was likely that the finger pulpitis noted in the physical examination was due to daily skateboarding rather than once-weekly swimming. Furthermore, the fingertip contact with concrete in pool palms is similar to the rough surface exposure on the skateboard.

Pool palms is more commonly reported in children due to their participation in sports and other activities with recent exposure to rough surfaces, most commonly the floor of swimming pools.2 The condition resolves after eliminating exposures.3 The frequency and duration of exposure to rough surfaces in swimming pools leading to development of this condition is unknown.

There have been mixed reports on the pathogenesis of pool palms. Some literature supports the idea that it is a wet dermatitis, a combination of prolonged water contact, friction, chemicals, and microbes leading to a chronic dermatitis. This theory states that the primary factor influencing the development of erythematous patches on the fingers, palms, and soles is the hyperhydration of the corneal layer at these sites.4 A different theory attributes pool palms to a mechanical origin, such as repeated microtrauma from contact with the rough concrete surfaces of swimming pools.5 This theory further states that the chemicals in pool water, such as chlorine and sodium hypochlorite, rarely produce irritant, allergic, or urticarial reactions.3

Based on these theories, we hypothesized that fingertip pulpitis can result from activities other than swimming (eg, skateboarding). Our case supports the latter theory on fingertip pulpitis in pool palms being a result of frictional dermatitis rather than wet dermatitis because we attributed our patient’s findings to contact with rough surfaces during skateboarding. Although the patient did swim, he only did so once weekly in the summer months, and the lesions had been persistent for 2 years consistently. His skateboarding hobby was more frequent, and he endorsed contact of the pads of the bilateral second to fifth fingers to the rough surfaces of the road and skateboard. The patient did not have lesions on the toes, further supporting the hypothesis that skateboarding led to the current presentation.

In children, hand-foot-and-mouth disease classically presents with oval-shaped, erythematous vesicles on the palmar surfaces of the hands and feet and generally is accompanied by fever and sore throat.6 Furthermore, unlike in our case, the viral exanthem usually would be present for up to 3 weeks and would not persist for more than 2 years. Erythema multiforme has an erythematous color and can present on the palms; however, the lesions have a classic targetoid appearance. It would be unique for erythema multiforme to present only on the fingertips rather than more diffusely on the palms or in other areas such as the face.7 Limited cutaneous sclerosis (scleroderma) initially can present with edematous pitted scars on the digital tips; however, with time the fingers will have a taut, white, shiny appearance that can develop into contractures and debilitating ulcerations.8 In our patient, the plaques did not advance to any further disease. Lastly, in contrast to our patient, punctate palmoplantar keratoderma presents as hyperkeratotic, firm, translucent, or opaque papules on the palms and soles. Over time, the papules can appear verrucous or callouslike.9 In our case, the plaques on the fingertips were erythematous rather than translucent or opaque papules.

Our case raises questions on whether prior reports of pool palms can be attributed to other activities involving contact with rough surfaces. More research is needed on the frequency and duration of rough surface exposure resulting in fingertip pulpitis.

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

The diagnosis of irritant contact dermatitis secondary to skateboarding is similar to pool palms, a benign, self-limiting irritant contact dermatitis.1 We propose that contact with concrete surfaces during skateboarding can lead to a presentation similar to pool palms. In our case, it was likely that the finger pulpitis noted in the physical examination was due to daily skateboarding rather than once-weekly swimming. Furthermore, the fingertip contact with concrete in pool palms is similar to the rough surface exposure on the skateboard.

Pool palms is more commonly reported in children due to their participation in sports and other activities with recent exposure to rough surfaces, most commonly the floor of swimming pools.2 The condition resolves after eliminating exposures.3 The frequency and duration of exposure to rough surfaces in swimming pools leading to development of this condition is unknown.

There have been mixed reports on the pathogenesis of pool palms. Some literature supports the idea that it is a wet dermatitis, a combination of prolonged water contact, friction, chemicals, and microbes leading to a chronic dermatitis. This theory states that the primary factor influencing the development of erythematous patches on the fingers, palms, and soles is the hyperhydration of the corneal layer at these sites.4 A different theory attributes pool palms to a mechanical origin, such as repeated microtrauma from contact with the rough concrete surfaces of swimming pools.5 This theory further states that the chemicals in pool water, such as chlorine and sodium hypochlorite, rarely produce irritant, allergic, or urticarial reactions.3

Based on these theories, we hypothesized that fingertip pulpitis can result from activities other than swimming (eg, skateboarding). Our case supports the latter theory on fingertip pulpitis in pool palms being a result of frictional dermatitis rather than wet dermatitis because we attributed our patient’s findings to contact with rough surfaces during skateboarding. Although the patient did swim, he only did so once weekly in the summer months, and the lesions had been persistent for 2 years consistently. His skateboarding hobby was more frequent, and he endorsed contact of the pads of the bilateral second to fifth fingers to the rough surfaces of the road and skateboard. The patient did not have lesions on the toes, further supporting the hypothesis that skateboarding led to the current presentation.

In children, hand-foot-and-mouth disease classically presents with oval-shaped, erythematous vesicles on the palmar surfaces of the hands and feet and generally is accompanied by fever and sore throat.6 Furthermore, unlike in our case, the viral exanthem usually would be present for up to 3 weeks and would not persist for more than 2 years. Erythema multiforme has an erythematous color and can present on the palms; however, the lesions have a classic targetoid appearance. It would be unique for erythema multiforme to present only on the fingertips rather than more diffusely on the palms or in other areas such as the face.7 Limited cutaneous sclerosis (scleroderma) initially can present with edematous pitted scars on the digital tips; however, with time the fingers will have a taut, white, shiny appearance that can develop into contractures and debilitating ulcerations.8 In our patient, the plaques did not advance to any further disease. Lastly, in contrast to our patient, punctate palmoplantar keratoderma presents as hyperkeratotic, firm, translucent, or opaque papules on the palms and soles. Over time, the papules can appear verrucous or callouslike.9 In our case, the plaques on the fingertips were erythematous rather than translucent or opaque papules.

Our case raises questions on whether prior reports of pool palms can be attributed to other activities involving contact with rough surfaces. More research is needed on the frequency and duration of rough surface exposure resulting in fingertip pulpitis.

- Lopez-Neyra A, Vano-Galvan S, Alvarez-Twose I, et al. Pool palms [in Spanish]. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

- Wong LC, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95.

- Mandojana RM. Pool palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2 pt 1):280-281.

- Novoa A, Klear S. Pool palms [published online September 30, 2015]. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:41.

- Martín JM, Martín JM, Ricart JM. Erythematous-violaceous lesions on the palms [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:507-508.

- Marcini AJ, Shani-Adir A. Other viral diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:1345-1366.

- French LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrosis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:319-334.

- Connoly MK. Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) and related disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:643-646.

- Krol AL, Siegel D. Keratodermas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:871-886.

- Lopez-Neyra A, Vano-Galvan S, Alvarez-Twose I, et al. Pool palms [in Spanish]. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

- Wong LC, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95.

- Mandojana RM. Pool palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2 pt 1):280-281.

- Novoa A, Klear S. Pool palms [published online September 30, 2015]. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:41.

- Martín JM, Martín JM, Ricart JM. Erythematous-violaceous lesions on the palms [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:507-508.

- Marcini AJ, Shani-Adir A. Other viral diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:1345-1366.

- French LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrosis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:319-334.

- Connoly MK. Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) and related disorders. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:643-646.

- Krol AL, Siegel D. Keratodermas. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2012:871-886.

A 12-year-old boy presented with well-defined, blanchable, erythematous patches on the distal bilateral palmar aspects of the second to fifth fingers of 2 years’ duration. The patient stated that he skateboarded daily throughout the year and swam once weekly in the summer months. Furthermore, the patient cited frequent contact with the rough undersurface of the skateboard and concrete road surfaces while skateboarding. He stated that the lesions were always present and worsened in the summer months. The lesions had an occasional burning sensation when they were more prominently erythematous, and the patient denied any pattern of exacerbation, numbness, bleeding, or itching. There was no notable family history or evidence of systemic disease.