User login

The Impact of a Paracentesis Clinic on Internal Medicine Resident Procedural Competency

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

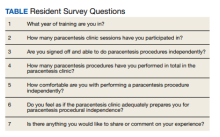

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255