User login

Bridging the Gap Between Inpatient and Outpatient Care

The Olin E. Teague Veterans’ Center (OETVC) in Temple, Texas, is a teaching hospital with 189 beds that provides patients access to medical, surgical, and specialty care. In 2022, 116,359 veterans received care at OETVC and 5393 inpatient admissions were noted. The inpatient ward consists of 3 teaching teams staffed by an attending physician, a second-year internal medicine resident, and 2 to 3 interns while hospitalists staff the 3 nonteaching teams. OETVC residents receive training on both routine and complex medical problems.

Each day, teaching teams discharge patients. With the complexity of discharges, there is always a risk of patients not following up with their primary care physicians, potential issues with filling medications, confusion about new medication regiments, and even potential postdischarge questions. In 1990, Holloway and colleagues evaluated potential risk factors for readmission among veterans. This study found that discharge from a geriatrics or intermediate care bed, chronic disease diagnosis, ≥ 2 procedures performed, increasing age, and distance from a veterans affairs medical center were risk factors.1

Several community hospital studies have evaluated readmission risk factors. One from 2000 noted that patients with more hospitalizations, lower mental health function, a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and increased satisfaction with access to emergency care were associated with increased readmission in 90 days.2 Due to the readmission risks, OETVC decided to construct a program that would help these patients successfully transition from inpatient to outpatient care while establishing means to discuss their care with a physician for reassurance and guidance.

TRANSITION OF CARE PROGRAM

Transition of care programs have been implemented and evaluated in many institutions. A 2017 systematic review of transition of care programs supported the use of tailored discharge planning and postdischarge phone calls to reduce hospital readmission, noting that 6 studies demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in 30-day readmission rate.3 Another study found that pharmacy involvement in the transition of care reduced medication-related problems following discharge.4

Program Goals

The foundational goal of our program was to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient medicine. We hoped to improve patient adherence with their discharge regimens, improve access to primary care physicians, and improve discharge follow-up. Since hospitalization can be overwhelming, we hoped to capture potential barriers to medical care postdischarge when patients return home while decreasing hospital readmissions. Our second- and third-year resident physicians spend as much time as needed going through the patient’s course of illness throughout their hospitalization and treatment plans to ensure their understanding and potential success.

This program benefits residents by providing medical education and patient communication opportunities. Residents must review the patient’s clinical trajectory before calling them. In this process, residents develop an understanding of routine and complex illness scripts, or pathways of common illnesses. They also prepare for potential questions about the hospitalization, new medications, and follow-up care. Lastly, residents can focus on communication skills. Without the time pressures of returning to a busy rotation, the residents spend as much time discussing the hospital course and ensuring patient understanding as needed.

Program Description

At the beginning of each week, second- and third-year residents review the list of discharges from the 3 teaching teams. The list is generated by a medical service management analyst. The residents review patient records for inpatient services, laboratory results, medication changes, and proposed follow-up plans designed by the admission team prior to their phone call. The resident is also responsible for reviewing and reconciling discharge instructions and orders. Then, the resident calls the patient and reviews their hospitalization. If a patient does not answer, the resident leaves a voicemail that complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

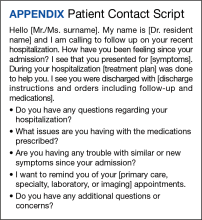

When patients answer the call, the resident follows a script (Appendix). Residents are encouraged to ask patients open-ended questions and address any new needs. They also discuss changes in symptoms, medications, functional status, and remind the patient about follow-up appointments. If imaging or specific orders were missed at discharge, the residents notify the chief resident, lead hospitalist, or deputy associate chief of staff for medical service. If additional laboratory tests need to be ordered, the resident devises a follow-up plan. If needed, specialty referrals can be placed. When residents feel there are multiple items that need to be addressed or if they notice any major concerns, they can recommend the patient present to the emergency department for evaluation. The chief resident, lead hospitalist, and deputy associate chair for medical service are available to assist with discussions about complex medical situations or new concerning symptoms. Residents document their encounters in the Computerized Patient Record System health record and any tests that need follow-up. This differs from the standard of care follow-up programs, which are conducted by primary care medicine nurses and do not fully discuss the hospitalization.

Implementation

This program was implemented as a 1-week elective for interested residents and part of the clinic rotation. The internal medicine medical service analyst pulls all discharges on Friday, which are then provided to the residents. The residents on rotation work through the discharges and find teaching team patients to follow up with and call.

Findings

Implementation of this program has yielded many benefits. The reminder of the importance of a primary care appointment has motivated patients to continue following up on an outpatient basis. Residents were also able to capture lapses in patient understanding. Residents could answer forgotten questions and help patients understand their admission pathology without time pressures. Residents have identified patients with hypoglycemia due to changed insulin regimens, set up specialist follow-up appointments, and provided additional education facilitating adherence. Additionally, several residents have expressed satisfaction with the ability to practice their communication skills. Others appreciated contributing to future patient successes.

While the focus on this article has been to share the program description, we have tabulated preliminary data. In January 2023, there were 239 internal medicine admissions; 158 admissions (66%) were teaching team patients, and 97 patients (61%) were called by a resident and spoken to regarding their care. There were 24 teaching team readmissions within 30 days, and 10 (42%) received a follow-up phone call. Eighty-one admitted patients were treated by nonteaching teams, 10 (12%) of whom were readmissions. Comparing 30-day readmission rates, 10 nonteaching team patients (12%), 10 teaching team patients (6.3%) who talk to a resident in the transition of care program were readmitted, and 24 teaching team patients who did not talk to a resident (10%) were readmitted.

DISCUSSION

The OETVC transition of care program was planned, formulated, and implemented without modeling after any other projects or institutions. This program aimed to utilize our residents as resources for patients.

Transition of care is defined as steps taken in a clinical encounter to assist with the coordination and continuity of patient care transferring between locations or levels of care.5 A 2018 study evaluating the utility of transition of care programs on adults aged ≥ 60 years found a reduction in rehospitalization rates, increased use of primary care services, and potential reduction in home health usage.6

In 2021, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine implemented a program after polling residents and discovering their awareness of gaps in the transition of care.7 In 2002, pharmacists evaluated the impact of follow-up telephone calls to recently hospitalized patients. This group of pharmacists found that these calls were associated with increased patient satisfaction, resolution of medication-related problems and fewer emergency department returns.8

Our program differs from other transition of care programs in that resident physicians made the follow-up calls to patients. Residents could address all aspects of medical care, including new symptoms, new prescriptions, adverse events, and risk factors for readmission, or order new imaging and medications when appropriate. In the program, residents called all patients discharged after receiving care within their team. Calls were not based on risk assessments. The residents were able to speak with 61% of discharged patients. When readmission rates were compared between patients who received a resident follow-up phone call and those who did not, patients receiving the resident phone call were readmitted at a lower rate: 6.3% vs 10%, respectively.

While our data suggest a potential trend of decreased readmission, more follow-up over a longer period may be needed. We believe this program can benefit patients and our model can act as a template for other institutions interested in starting their own programs.

Challenges

Although our process is efficient, there have been some challenges. The discharge is created by the medical service management analyst and then sent to the chief resident, but there was concern that the list could be missed if either individual was unavailable. The chairperson for the department of medicine and their secretary are now involved in the process. To reduce unanswered telephone calls, residents use OETVC phones. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant voicemails providing a time for a follow-up call were implemented. As a result, veterans have answered their phones more regularly and are more aware of calls. Orders are generally placed by the chief resident, lead hospitalist, or chair of the medical service to ensure follow-up because residents are on rotation for 1 week at a time. Access to a physician also allows patients to discuss items unrelated to their hospitalization, introducing new symptoms, or situations requiring a resident to act with limited data.

CONCLUSIONS

The transition of care follow-up program described in this article may be beneficial for both internal medicine residents and patients. Second- and third-year residents are developing a better understanding of the trajectory of many illnesses and are given the opportunity to retrospectively analyze what they would do differently based on knowledge gained from their chart reviews. They are also given the opportunity to work on communication skills and explain courses of illnesses to patients in an easy-to-understand format without time constraints. Patients now have access to a physician following discharge to discuss any concerns with their hospitalization, condition, and follow-up. This program will continue to address barriers to care and adapt to improve the success of care transitions.

1. Holloway JJ, Medendorp SV, Bromberg J. Risk factors for early readmission among veterans. Health Serv Res. 1990;25(1 Pt 2):213-237.

2. Smith DM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Weinberger M, et al. Predicting non-elective hospital readmissions: a multi-site study. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Readmissions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1113-1118. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00236-5

3. Kamermayer AK, Leasure AR, Anderson L. The Effectiveness of Transitions-of-Care Interventions in Reducing Hospital Readmissions and Mortality: A Systematic Review. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36(6):311-316. doi:10.1097/DCC.0000000000000266

4. Daliri S, Hugtenburg JG, Ter Riet G, et al. The effect of a pharmacy-led transitional care program on medication-related problems post-discharge: A before-After prospective study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213593. Published 2019 Mar 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213593

5. Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549-555. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x

6. Weeks LE, Macdonald M, Helwig M, Bishop A, Martin-Misener R, Iduye D. The impact of transitional care programs on health services utilization among community-dwelling older adults and their caregivers: a systematic review protocol of quantitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(3):26-34. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-2568

7. Sheikh F, Gathecha E, Arbaje AI, Christmas C. Internal Medicine Residents’ Views About Care Transitions: Results of an Educational Intervention. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:2382120520988590. Published 2021 Jan 20. doi:10.1177/2382120520988590

8. Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):239-248. doi:10.1016/s0011-5029(02)90031-3

The Olin E. Teague Veterans’ Center (OETVC) in Temple, Texas, is a teaching hospital with 189 beds that provides patients access to medical, surgical, and specialty care. In 2022, 116,359 veterans received care at OETVC and 5393 inpatient admissions were noted. The inpatient ward consists of 3 teaching teams staffed by an attending physician, a second-year internal medicine resident, and 2 to 3 interns while hospitalists staff the 3 nonteaching teams. OETVC residents receive training on both routine and complex medical problems.

Each day, teaching teams discharge patients. With the complexity of discharges, there is always a risk of patients not following up with their primary care physicians, potential issues with filling medications, confusion about new medication regiments, and even potential postdischarge questions. In 1990, Holloway and colleagues evaluated potential risk factors for readmission among veterans. This study found that discharge from a geriatrics or intermediate care bed, chronic disease diagnosis, ≥ 2 procedures performed, increasing age, and distance from a veterans affairs medical center were risk factors.1

Several community hospital studies have evaluated readmission risk factors. One from 2000 noted that patients with more hospitalizations, lower mental health function, a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and increased satisfaction with access to emergency care were associated with increased readmission in 90 days.2 Due to the readmission risks, OETVC decided to construct a program that would help these patients successfully transition from inpatient to outpatient care while establishing means to discuss their care with a physician for reassurance and guidance.

TRANSITION OF CARE PROGRAM

Transition of care programs have been implemented and evaluated in many institutions. A 2017 systematic review of transition of care programs supported the use of tailored discharge planning and postdischarge phone calls to reduce hospital readmission, noting that 6 studies demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in 30-day readmission rate.3 Another study found that pharmacy involvement in the transition of care reduced medication-related problems following discharge.4

Program Goals

The foundational goal of our program was to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient medicine. We hoped to improve patient adherence with their discharge regimens, improve access to primary care physicians, and improve discharge follow-up. Since hospitalization can be overwhelming, we hoped to capture potential barriers to medical care postdischarge when patients return home while decreasing hospital readmissions. Our second- and third-year resident physicians spend as much time as needed going through the patient’s course of illness throughout their hospitalization and treatment plans to ensure their understanding and potential success.

This program benefits residents by providing medical education and patient communication opportunities. Residents must review the patient’s clinical trajectory before calling them. In this process, residents develop an understanding of routine and complex illness scripts, or pathways of common illnesses. They also prepare for potential questions about the hospitalization, new medications, and follow-up care. Lastly, residents can focus on communication skills. Without the time pressures of returning to a busy rotation, the residents spend as much time discussing the hospital course and ensuring patient understanding as needed.

Program Description

At the beginning of each week, second- and third-year residents review the list of discharges from the 3 teaching teams. The list is generated by a medical service management analyst. The residents review patient records for inpatient services, laboratory results, medication changes, and proposed follow-up plans designed by the admission team prior to their phone call. The resident is also responsible for reviewing and reconciling discharge instructions and orders. Then, the resident calls the patient and reviews their hospitalization. If a patient does not answer, the resident leaves a voicemail that complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

When patients answer the call, the resident follows a script (Appendix). Residents are encouraged to ask patients open-ended questions and address any new needs. They also discuss changes in symptoms, medications, functional status, and remind the patient about follow-up appointments. If imaging or specific orders were missed at discharge, the residents notify the chief resident, lead hospitalist, or deputy associate chief of staff for medical service. If additional laboratory tests need to be ordered, the resident devises a follow-up plan. If needed, specialty referrals can be placed. When residents feel there are multiple items that need to be addressed or if they notice any major concerns, they can recommend the patient present to the emergency department for evaluation. The chief resident, lead hospitalist, and deputy associate chair for medical service are available to assist with discussions about complex medical situations or new concerning symptoms. Residents document their encounters in the Computerized Patient Record System health record and any tests that need follow-up. This differs from the standard of care follow-up programs, which are conducted by primary care medicine nurses and do not fully discuss the hospitalization.

Implementation

This program was implemented as a 1-week elective for interested residents and part of the clinic rotation. The internal medicine medical service analyst pulls all discharges on Friday, which are then provided to the residents. The residents on rotation work through the discharges and find teaching team patients to follow up with and call.

Findings

Implementation of this program has yielded many benefits. The reminder of the importance of a primary care appointment has motivated patients to continue following up on an outpatient basis. Residents were also able to capture lapses in patient understanding. Residents could answer forgotten questions and help patients understand their admission pathology without time pressures. Residents have identified patients with hypoglycemia due to changed insulin regimens, set up specialist follow-up appointments, and provided additional education facilitating adherence. Additionally, several residents have expressed satisfaction with the ability to practice their communication skills. Others appreciated contributing to future patient successes.

While the focus on this article has been to share the program description, we have tabulated preliminary data. In January 2023, there were 239 internal medicine admissions; 158 admissions (66%) were teaching team patients, and 97 patients (61%) were called by a resident and spoken to regarding their care. There were 24 teaching team readmissions within 30 days, and 10 (42%) received a follow-up phone call. Eighty-one admitted patients were treated by nonteaching teams, 10 (12%) of whom were readmissions. Comparing 30-day readmission rates, 10 nonteaching team patients (12%), 10 teaching team patients (6.3%) who talk to a resident in the transition of care program were readmitted, and 24 teaching team patients who did not talk to a resident (10%) were readmitted.

DISCUSSION

The OETVC transition of care program was planned, formulated, and implemented without modeling after any other projects or institutions. This program aimed to utilize our residents as resources for patients.

Transition of care is defined as steps taken in a clinical encounter to assist with the coordination and continuity of patient care transferring between locations or levels of care.5 A 2018 study evaluating the utility of transition of care programs on adults aged ≥ 60 years found a reduction in rehospitalization rates, increased use of primary care services, and potential reduction in home health usage.6

In 2021, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine implemented a program after polling residents and discovering their awareness of gaps in the transition of care.7 In 2002, pharmacists evaluated the impact of follow-up telephone calls to recently hospitalized patients. This group of pharmacists found that these calls were associated with increased patient satisfaction, resolution of medication-related problems and fewer emergency department returns.8

Our program differs from other transition of care programs in that resident physicians made the follow-up calls to patients. Residents could address all aspects of medical care, including new symptoms, new prescriptions, adverse events, and risk factors for readmission, or order new imaging and medications when appropriate. In the program, residents called all patients discharged after receiving care within their team. Calls were not based on risk assessments. The residents were able to speak with 61% of discharged patients. When readmission rates were compared between patients who received a resident follow-up phone call and those who did not, patients receiving the resident phone call were readmitted at a lower rate: 6.3% vs 10%, respectively.

While our data suggest a potential trend of decreased readmission, more follow-up over a longer period may be needed. We believe this program can benefit patients and our model can act as a template for other institutions interested in starting their own programs.

Challenges

Although our process is efficient, there have been some challenges. The discharge is created by the medical service management analyst and then sent to the chief resident, but there was concern that the list could be missed if either individual was unavailable. The chairperson for the department of medicine and their secretary are now involved in the process. To reduce unanswered telephone calls, residents use OETVC phones. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant voicemails providing a time for a follow-up call were implemented. As a result, veterans have answered their phones more regularly and are more aware of calls. Orders are generally placed by the chief resident, lead hospitalist, or chair of the medical service to ensure follow-up because residents are on rotation for 1 week at a time. Access to a physician also allows patients to discuss items unrelated to their hospitalization, introducing new symptoms, or situations requiring a resident to act with limited data.

CONCLUSIONS

The transition of care follow-up program described in this article may be beneficial for both internal medicine residents and patients. Second- and third-year residents are developing a better understanding of the trajectory of many illnesses and are given the opportunity to retrospectively analyze what they would do differently based on knowledge gained from their chart reviews. They are also given the opportunity to work on communication skills and explain courses of illnesses to patients in an easy-to-understand format without time constraints. Patients now have access to a physician following discharge to discuss any concerns with their hospitalization, condition, and follow-up. This program will continue to address barriers to care and adapt to improve the success of care transitions.

The Olin E. Teague Veterans’ Center (OETVC) in Temple, Texas, is a teaching hospital with 189 beds that provides patients access to medical, surgical, and specialty care. In 2022, 116,359 veterans received care at OETVC and 5393 inpatient admissions were noted. The inpatient ward consists of 3 teaching teams staffed by an attending physician, a second-year internal medicine resident, and 2 to 3 interns while hospitalists staff the 3 nonteaching teams. OETVC residents receive training on both routine and complex medical problems.

Each day, teaching teams discharge patients. With the complexity of discharges, there is always a risk of patients not following up with their primary care physicians, potential issues with filling medications, confusion about new medication regiments, and even potential postdischarge questions. In 1990, Holloway and colleagues evaluated potential risk factors for readmission among veterans. This study found that discharge from a geriatrics or intermediate care bed, chronic disease diagnosis, ≥ 2 procedures performed, increasing age, and distance from a veterans affairs medical center were risk factors.1

Several community hospital studies have evaluated readmission risk factors. One from 2000 noted that patients with more hospitalizations, lower mental health function, a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and increased satisfaction with access to emergency care were associated with increased readmission in 90 days.2 Due to the readmission risks, OETVC decided to construct a program that would help these patients successfully transition from inpatient to outpatient care while establishing means to discuss their care with a physician for reassurance and guidance.

TRANSITION OF CARE PROGRAM

Transition of care programs have been implemented and evaluated in many institutions. A 2017 systematic review of transition of care programs supported the use of tailored discharge planning and postdischarge phone calls to reduce hospital readmission, noting that 6 studies demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in 30-day readmission rate.3 Another study found that pharmacy involvement in the transition of care reduced medication-related problems following discharge.4

Program Goals

The foundational goal of our program was to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient medicine. We hoped to improve patient adherence with their discharge regimens, improve access to primary care physicians, and improve discharge follow-up. Since hospitalization can be overwhelming, we hoped to capture potential barriers to medical care postdischarge when patients return home while decreasing hospital readmissions. Our second- and third-year resident physicians spend as much time as needed going through the patient’s course of illness throughout their hospitalization and treatment plans to ensure their understanding and potential success.

This program benefits residents by providing medical education and patient communication opportunities. Residents must review the patient’s clinical trajectory before calling them. In this process, residents develop an understanding of routine and complex illness scripts, or pathways of common illnesses. They also prepare for potential questions about the hospitalization, new medications, and follow-up care. Lastly, residents can focus on communication skills. Without the time pressures of returning to a busy rotation, the residents spend as much time discussing the hospital course and ensuring patient understanding as needed.

Program Description

At the beginning of each week, second- and third-year residents review the list of discharges from the 3 teaching teams. The list is generated by a medical service management analyst. The residents review patient records for inpatient services, laboratory results, medication changes, and proposed follow-up plans designed by the admission team prior to their phone call. The resident is also responsible for reviewing and reconciling discharge instructions and orders. Then, the resident calls the patient and reviews their hospitalization. If a patient does not answer, the resident leaves a voicemail that complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

When patients answer the call, the resident follows a script (Appendix). Residents are encouraged to ask patients open-ended questions and address any new needs. They also discuss changes in symptoms, medications, functional status, and remind the patient about follow-up appointments. If imaging or specific orders were missed at discharge, the residents notify the chief resident, lead hospitalist, or deputy associate chief of staff for medical service. If additional laboratory tests need to be ordered, the resident devises a follow-up plan. If needed, specialty referrals can be placed. When residents feel there are multiple items that need to be addressed or if they notice any major concerns, they can recommend the patient present to the emergency department for evaluation. The chief resident, lead hospitalist, and deputy associate chair for medical service are available to assist with discussions about complex medical situations or new concerning symptoms. Residents document their encounters in the Computerized Patient Record System health record and any tests that need follow-up. This differs from the standard of care follow-up programs, which are conducted by primary care medicine nurses and do not fully discuss the hospitalization.

Implementation

This program was implemented as a 1-week elective for interested residents and part of the clinic rotation. The internal medicine medical service analyst pulls all discharges on Friday, which are then provided to the residents. The residents on rotation work through the discharges and find teaching team patients to follow up with and call.

Findings

Implementation of this program has yielded many benefits. The reminder of the importance of a primary care appointment has motivated patients to continue following up on an outpatient basis. Residents were also able to capture lapses in patient understanding. Residents could answer forgotten questions and help patients understand their admission pathology without time pressures. Residents have identified patients with hypoglycemia due to changed insulin regimens, set up specialist follow-up appointments, and provided additional education facilitating adherence. Additionally, several residents have expressed satisfaction with the ability to practice their communication skills. Others appreciated contributing to future patient successes.

While the focus on this article has been to share the program description, we have tabulated preliminary data. In January 2023, there were 239 internal medicine admissions; 158 admissions (66%) were teaching team patients, and 97 patients (61%) were called by a resident and spoken to regarding their care. There were 24 teaching team readmissions within 30 days, and 10 (42%) received a follow-up phone call. Eighty-one admitted patients were treated by nonteaching teams, 10 (12%) of whom were readmissions. Comparing 30-day readmission rates, 10 nonteaching team patients (12%), 10 teaching team patients (6.3%) who talk to a resident in the transition of care program were readmitted, and 24 teaching team patients who did not talk to a resident (10%) were readmitted.

DISCUSSION

The OETVC transition of care program was planned, formulated, and implemented without modeling after any other projects or institutions. This program aimed to utilize our residents as resources for patients.

Transition of care is defined as steps taken in a clinical encounter to assist with the coordination and continuity of patient care transferring between locations or levels of care.5 A 2018 study evaluating the utility of transition of care programs on adults aged ≥ 60 years found a reduction in rehospitalization rates, increased use of primary care services, and potential reduction in home health usage.6

In 2021, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine implemented a program after polling residents and discovering their awareness of gaps in the transition of care.7 In 2002, pharmacists evaluated the impact of follow-up telephone calls to recently hospitalized patients. This group of pharmacists found that these calls were associated with increased patient satisfaction, resolution of medication-related problems and fewer emergency department returns.8

Our program differs from other transition of care programs in that resident physicians made the follow-up calls to patients. Residents could address all aspects of medical care, including new symptoms, new prescriptions, adverse events, and risk factors for readmission, or order new imaging and medications when appropriate. In the program, residents called all patients discharged after receiving care within their team. Calls were not based on risk assessments. The residents were able to speak with 61% of discharged patients. When readmission rates were compared between patients who received a resident follow-up phone call and those who did not, patients receiving the resident phone call were readmitted at a lower rate: 6.3% vs 10%, respectively.

While our data suggest a potential trend of decreased readmission, more follow-up over a longer period may be needed. We believe this program can benefit patients and our model can act as a template for other institutions interested in starting their own programs.

Challenges

Although our process is efficient, there have been some challenges. The discharge is created by the medical service management analyst and then sent to the chief resident, but there was concern that the list could be missed if either individual was unavailable. The chairperson for the department of medicine and their secretary are now involved in the process. To reduce unanswered telephone calls, residents use OETVC phones. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant voicemails providing a time for a follow-up call were implemented. As a result, veterans have answered their phones more regularly and are more aware of calls. Orders are generally placed by the chief resident, lead hospitalist, or chair of the medical service to ensure follow-up because residents are on rotation for 1 week at a time. Access to a physician also allows patients to discuss items unrelated to their hospitalization, introducing new symptoms, or situations requiring a resident to act with limited data.

CONCLUSIONS

The transition of care follow-up program described in this article may be beneficial for both internal medicine residents and patients. Second- and third-year residents are developing a better understanding of the trajectory of many illnesses and are given the opportunity to retrospectively analyze what they would do differently based on knowledge gained from their chart reviews. They are also given the opportunity to work on communication skills and explain courses of illnesses to patients in an easy-to-understand format without time constraints. Patients now have access to a physician following discharge to discuss any concerns with their hospitalization, condition, and follow-up. This program will continue to address barriers to care and adapt to improve the success of care transitions.

1. Holloway JJ, Medendorp SV, Bromberg J. Risk factors for early readmission among veterans. Health Serv Res. 1990;25(1 Pt 2):213-237.

2. Smith DM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Weinberger M, et al. Predicting non-elective hospital readmissions: a multi-site study. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Readmissions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1113-1118. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00236-5

3. Kamermayer AK, Leasure AR, Anderson L. The Effectiveness of Transitions-of-Care Interventions in Reducing Hospital Readmissions and Mortality: A Systematic Review. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36(6):311-316. doi:10.1097/DCC.0000000000000266

4. Daliri S, Hugtenburg JG, Ter Riet G, et al. The effect of a pharmacy-led transitional care program on medication-related problems post-discharge: A before-After prospective study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213593. Published 2019 Mar 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213593

5. Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549-555. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x

6. Weeks LE, Macdonald M, Helwig M, Bishop A, Martin-Misener R, Iduye D. The impact of transitional care programs on health services utilization among community-dwelling older adults and their caregivers: a systematic review protocol of quantitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(3):26-34. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-2568

7. Sheikh F, Gathecha E, Arbaje AI, Christmas C. Internal Medicine Residents’ Views About Care Transitions: Results of an Educational Intervention. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:2382120520988590. Published 2021 Jan 20. doi:10.1177/2382120520988590

8. Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):239-248. doi:10.1016/s0011-5029(02)90031-3

1. Holloway JJ, Medendorp SV, Bromberg J. Risk factors for early readmission among veterans. Health Serv Res. 1990;25(1 Pt 2):213-237.

2. Smith DM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Weinberger M, et al. Predicting non-elective hospital readmissions: a multi-site study. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Readmissions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1113-1118. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00236-5

3. Kamermayer AK, Leasure AR, Anderson L. The Effectiveness of Transitions-of-Care Interventions in Reducing Hospital Readmissions and Mortality: A Systematic Review. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36(6):311-316. doi:10.1097/DCC.0000000000000266

4. Daliri S, Hugtenburg JG, Ter Riet G, et al. The effect of a pharmacy-led transitional care program on medication-related problems post-discharge: A before-After prospective study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213593. Published 2019 Mar 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213593

5. Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549-555. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x

6. Weeks LE, Macdonald M, Helwig M, Bishop A, Martin-Misener R, Iduye D. The impact of transitional care programs on health services utilization among community-dwelling older adults and their caregivers: a systematic review protocol of quantitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(3):26-34. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-2568

7. Sheikh F, Gathecha E, Arbaje AI, Christmas C. Internal Medicine Residents’ Views About Care Transitions: Results of an Educational Intervention. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:2382120520988590. Published 2021 Jan 20. doi:10.1177/2382120520988590

8. Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):239-248. doi:10.1016/s0011-5029(02)90031-3

The Impact of a Paracentesis Clinic on Internal Medicine Resident Procedural Competency

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

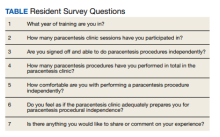

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255