User login

Suture Selection to Minimize Postoperative Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Patients With Skin of Color During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Practice Gap

Proper suture selection is imperative for appropriate wound healing to minimize the risk for infection and inflammation and to reduce scarring. In Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), suture selection should be given high consideration in patients with skin of color.1 Using the right type of suture and wound closure technique can lead to favorable aesthetic outcomes by preventing postoperative postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and keloids. Data on the choice of suture material in patients with skin of color are limited.

Suture selection depends on a variety of factors including but not limited to the location of the wound on the body, risk for infection, cost, availability, and the personal preference and experience of the MMS surgeon. During the COVID-19 pandemic, suturepreference among dermatologic surgeons shifted to fast-absorbing gut sutures,2 offering alternatives to synthetic monofilament polypropylene and nylon sutures. Absorbable sutures reduced the need for in-person follow-up visits without increasing the incidence of postoperative complications.

Despite these benefits, research suggests that natural absorbable gut sutures induce cutaneous inflammation and should be avoided in patients with skin of color.1,3,4 Nonabsorbable sutures are less reactive, reducing PIH after MMS in patients with skin of color.

Tools and Technique

Use of nonabsorbable stitches is a practical solution to reduce the risk for inflammation in patients with skin of color. Increased inflammation can lead to PIH and increase the risk for keloids in this patient population. Some patients will experience PIH after a surgical procedure regardless of the sutures used to repair the closure; however, one of our goals with patients with skin of color undergoing MMS is to reduce the inflammatory risk that could lead to PIH to ensure optimal aesthetic outcomes.

A middle-aged African woman with darker skin and a history of developing PIH after trauma to the skin presented to our clinic for MMS of a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans on the upper abdomen. We used a simple running suture with 4-0 nylon to close the surgical wound. We avoided fast-absorbing gut sutures because they have high tissue reactivity1,4; use of sutures with low tissue reactivity, such as nylon and polypropylene, decreases the risk for inflammation without compromising alignment of wound edges and overall cosmesis of the repair. Prolene also is cost-effective and presents a decreased risk for wound dehiscence.5 After cauterizing the wound, we placed multiple synthetic absorbable sutures first to close the wound. We then did a double-running suture of nonabsorbable monofilament suture to reapproximate the epidermal edges with minimal tension. We placed 2 sets of running stitches to minimize the risk for dehiscence along the scar.

The patient was required to return for removal of the nonabsorbable sutures; this postoperative visit was covered by health insurance at no additional cost to the patient. In comparison, long-term repeat visits to treat PIH with a laser or chemical peel would have been more costly. Given that treatment of PIH is considered cosmetic, laser treatment would have been priced at several hundred dollars per session at our institution, and the patient would likely have had a copay for a pretreatment lightening cream such as hydroquinone. Our patient had a favorable cosmetic outcome and reported no or minimal evidence of PIH months after the procedure.

Patients should be instructed to apply petrolatum twice daily, use sun-protective clothing, and cover sutures to minimize exposure to the sun and prevent crusting of the wound. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can be proactively treated postoperatively with topical hydroquinone, which was not needed in our patient.

Practice Implications

Although some studies suggest that there are no cosmetic differences between absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures, the effect of suture type in patients with skin of color undergoing MMS often is unreported or is not studied.6,7 The high reactivity and cutaneous inflammation associated with absorbable gut sutures are important considerations in this patient population.

In patients with skin of color undergoing MMS, we use nonabsorbable epidermal sutures such as nylon and Prolene because of their low reactivity and association with favorable aesthetic outcomes. Nonabsorbable sutures can be safely used in patients of all ages who are undergoing MMS under local anesthesia.

An exception would be the use of the absorbable suture Monocryl (J&J MedTech) in patients with skin of color who need a running subcuticular wound closure because it has low tissue reactivity and maintains high tensile strength. Monocryl has been shown to create less-reactive scars, which decreases the risk for keloids.8,9

More clinical studies are needed to assess the increased susceptibility to PIH in patients with skin of color when using absorbable gut sutures.

- Williams R, Ciocon D. Mohs micrographic surgery in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:536-541. doi:10.36849/JDD.6469

- Gallop J, Andrasik W, Lucas J. Successful use of percutaneous dissolvable sutures during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:34-38. doi:10.1177/12034754221143083

- Byrne M, Aly A. The surgical suture. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(suppl 2):S67-S72. doi:10.1093/asj/sjz036

- Koppa M, House R, Tobin V, et al. Suture material choice can increase risk of hypersensitivity in hand trauma patients. Eur J Plast Surg. 2023;46:239-243. doi:10.1007/s00238-022-01986-7

- Pandey S, Singh M, Singh K, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing non-absorbable polypropylene (Prolene®) and delayed absorbable polyglactin 910 (Vicryl®) suture material in mass closure of vertical laparotomy wounds. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:306-310. doi:10.1007/s12262-012-0492-x

- Parell GJ, Becker GD. Comparison of absorbable with nonabsorbable sutures in closure of facial skin wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003;5:488-490. doi:10.1001/archfaci.5.6.488

- Kim J, Singh Maan H, Cool AJ, et al. Fast absorbing gut suture versus cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in the epidermal closure of linear repairs following Mohs micrographic surgery. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:24-29.

- Niessen FB, Spauwen PH, Kon M. The role of suture material in hypertrophic scar formation: Monocryl vs. Vicryl-Rapide. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:254-260. doi:10.1097/00000637-199709000-00006

- Fosko SW, Heap D. Surgical pearl: an economical means of skin closure with absorbable suture. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 pt 1):248-250. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70084-2

Practice Gap

Proper suture selection is imperative for appropriate wound healing to minimize the risk for infection and inflammation and to reduce scarring. In Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), suture selection should be given high consideration in patients with skin of color.1 Using the right type of suture and wound closure technique can lead to favorable aesthetic outcomes by preventing postoperative postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and keloids. Data on the choice of suture material in patients with skin of color are limited.

Suture selection depends on a variety of factors including but not limited to the location of the wound on the body, risk for infection, cost, availability, and the personal preference and experience of the MMS surgeon. During the COVID-19 pandemic, suturepreference among dermatologic surgeons shifted to fast-absorbing gut sutures,2 offering alternatives to synthetic monofilament polypropylene and nylon sutures. Absorbable sutures reduced the need for in-person follow-up visits without increasing the incidence of postoperative complications.

Despite these benefits, research suggests that natural absorbable gut sutures induce cutaneous inflammation and should be avoided in patients with skin of color.1,3,4 Nonabsorbable sutures are less reactive, reducing PIH after MMS in patients with skin of color.

Tools and Technique

Use of nonabsorbable stitches is a practical solution to reduce the risk for inflammation in patients with skin of color. Increased inflammation can lead to PIH and increase the risk for keloids in this patient population. Some patients will experience PIH after a surgical procedure regardless of the sutures used to repair the closure; however, one of our goals with patients with skin of color undergoing MMS is to reduce the inflammatory risk that could lead to PIH to ensure optimal aesthetic outcomes.

A middle-aged African woman with darker skin and a history of developing PIH after trauma to the skin presented to our clinic for MMS of a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans on the upper abdomen. We used a simple running suture with 4-0 nylon to close the surgical wound. We avoided fast-absorbing gut sutures because they have high tissue reactivity1,4; use of sutures with low tissue reactivity, such as nylon and polypropylene, decreases the risk for inflammation without compromising alignment of wound edges and overall cosmesis of the repair. Prolene also is cost-effective and presents a decreased risk for wound dehiscence.5 After cauterizing the wound, we placed multiple synthetic absorbable sutures first to close the wound. We then did a double-running suture of nonabsorbable monofilament suture to reapproximate the epidermal edges with minimal tension. We placed 2 sets of running stitches to minimize the risk for dehiscence along the scar.

The patient was required to return for removal of the nonabsorbable sutures; this postoperative visit was covered by health insurance at no additional cost to the patient. In comparison, long-term repeat visits to treat PIH with a laser or chemical peel would have been more costly. Given that treatment of PIH is considered cosmetic, laser treatment would have been priced at several hundred dollars per session at our institution, and the patient would likely have had a copay for a pretreatment lightening cream such as hydroquinone. Our patient had a favorable cosmetic outcome and reported no or minimal evidence of PIH months after the procedure.

Patients should be instructed to apply petrolatum twice daily, use sun-protective clothing, and cover sutures to minimize exposure to the sun and prevent crusting of the wound. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can be proactively treated postoperatively with topical hydroquinone, which was not needed in our patient.

Practice Implications

Although some studies suggest that there are no cosmetic differences between absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures, the effect of suture type in patients with skin of color undergoing MMS often is unreported or is not studied.6,7 The high reactivity and cutaneous inflammation associated with absorbable gut sutures are important considerations in this patient population.

In patients with skin of color undergoing MMS, we use nonabsorbable epidermal sutures such as nylon and Prolene because of their low reactivity and association with favorable aesthetic outcomes. Nonabsorbable sutures can be safely used in patients of all ages who are undergoing MMS under local anesthesia.

An exception would be the use of the absorbable suture Monocryl (J&J MedTech) in patients with skin of color who need a running subcuticular wound closure because it has low tissue reactivity and maintains high tensile strength. Monocryl has been shown to create less-reactive scars, which decreases the risk for keloids.8,9

More clinical studies are needed to assess the increased susceptibility to PIH in patients with skin of color when using absorbable gut sutures.

Practice Gap

Proper suture selection is imperative for appropriate wound healing to minimize the risk for infection and inflammation and to reduce scarring. In Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), suture selection should be given high consideration in patients with skin of color.1 Using the right type of suture and wound closure technique can lead to favorable aesthetic outcomes by preventing postoperative postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and keloids. Data on the choice of suture material in patients with skin of color are limited.

Suture selection depends on a variety of factors including but not limited to the location of the wound on the body, risk for infection, cost, availability, and the personal preference and experience of the MMS surgeon. During the COVID-19 pandemic, suturepreference among dermatologic surgeons shifted to fast-absorbing gut sutures,2 offering alternatives to synthetic monofilament polypropylene and nylon sutures. Absorbable sutures reduced the need for in-person follow-up visits without increasing the incidence of postoperative complications.

Despite these benefits, research suggests that natural absorbable gut sutures induce cutaneous inflammation and should be avoided in patients with skin of color.1,3,4 Nonabsorbable sutures are less reactive, reducing PIH after MMS in patients with skin of color.

Tools and Technique

Use of nonabsorbable stitches is a practical solution to reduce the risk for inflammation in patients with skin of color. Increased inflammation can lead to PIH and increase the risk for keloids in this patient population. Some patients will experience PIH after a surgical procedure regardless of the sutures used to repair the closure; however, one of our goals with patients with skin of color undergoing MMS is to reduce the inflammatory risk that could lead to PIH to ensure optimal aesthetic outcomes.

A middle-aged African woman with darker skin and a history of developing PIH after trauma to the skin presented to our clinic for MMS of a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans on the upper abdomen. We used a simple running suture with 4-0 nylon to close the surgical wound. We avoided fast-absorbing gut sutures because they have high tissue reactivity1,4; use of sutures with low tissue reactivity, such as nylon and polypropylene, decreases the risk for inflammation without compromising alignment of wound edges and overall cosmesis of the repair. Prolene also is cost-effective and presents a decreased risk for wound dehiscence.5 After cauterizing the wound, we placed multiple synthetic absorbable sutures first to close the wound. We then did a double-running suture of nonabsorbable monofilament suture to reapproximate the epidermal edges with minimal tension. We placed 2 sets of running stitches to minimize the risk for dehiscence along the scar.

The patient was required to return for removal of the nonabsorbable sutures; this postoperative visit was covered by health insurance at no additional cost to the patient. In comparison, long-term repeat visits to treat PIH with a laser or chemical peel would have been more costly. Given that treatment of PIH is considered cosmetic, laser treatment would have been priced at several hundred dollars per session at our institution, and the patient would likely have had a copay for a pretreatment lightening cream such as hydroquinone. Our patient had a favorable cosmetic outcome and reported no or minimal evidence of PIH months after the procedure.

Patients should be instructed to apply petrolatum twice daily, use sun-protective clothing, and cover sutures to minimize exposure to the sun and prevent crusting of the wound. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can be proactively treated postoperatively with topical hydroquinone, which was not needed in our patient.

Practice Implications

Although some studies suggest that there are no cosmetic differences between absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures, the effect of suture type in patients with skin of color undergoing MMS often is unreported or is not studied.6,7 The high reactivity and cutaneous inflammation associated with absorbable gut sutures are important considerations in this patient population.

In patients with skin of color undergoing MMS, we use nonabsorbable epidermal sutures such as nylon and Prolene because of their low reactivity and association with favorable aesthetic outcomes. Nonabsorbable sutures can be safely used in patients of all ages who are undergoing MMS under local anesthesia.

An exception would be the use of the absorbable suture Monocryl (J&J MedTech) in patients with skin of color who need a running subcuticular wound closure because it has low tissue reactivity and maintains high tensile strength. Monocryl has been shown to create less-reactive scars, which decreases the risk for keloids.8,9

More clinical studies are needed to assess the increased susceptibility to PIH in patients with skin of color when using absorbable gut sutures.

- Williams R, Ciocon D. Mohs micrographic surgery in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:536-541. doi:10.36849/JDD.6469

- Gallop J, Andrasik W, Lucas J. Successful use of percutaneous dissolvable sutures during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:34-38. doi:10.1177/12034754221143083

- Byrne M, Aly A. The surgical suture. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(suppl 2):S67-S72. doi:10.1093/asj/sjz036

- Koppa M, House R, Tobin V, et al. Suture material choice can increase risk of hypersensitivity in hand trauma patients. Eur J Plast Surg. 2023;46:239-243. doi:10.1007/s00238-022-01986-7

- Pandey S, Singh M, Singh K, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing non-absorbable polypropylene (Prolene®) and delayed absorbable polyglactin 910 (Vicryl®) suture material in mass closure of vertical laparotomy wounds. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:306-310. doi:10.1007/s12262-012-0492-x

- Parell GJ, Becker GD. Comparison of absorbable with nonabsorbable sutures in closure of facial skin wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003;5:488-490. doi:10.1001/archfaci.5.6.488

- Kim J, Singh Maan H, Cool AJ, et al. Fast absorbing gut suture versus cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in the epidermal closure of linear repairs following Mohs micrographic surgery. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:24-29.

- Niessen FB, Spauwen PH, Kon M. The role of suture material in hypertrophic scar formation: Monocryl vs. Vicryl-Rapide. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:254-260. doi:10.1097/00000637-199709000-00006

- Fosko SW, Heap D. Surgical pearl: an economical means of skin closure with absorbable suture. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 pt 1):248-250. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70084-2

- Williams R, Ciocon D. Mohs micrographic surgery in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:536-541. doi:10.36849/JDD.6469

- Gallop J, Andrasik W, Lucas J. Successful use of percutaneous dissolvable sutures during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:34-38. doi:10.1177/12034754221143083

- Byrne M, Aly A. The surgical suture. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(suppl 2):S67-S72. doi:10.1093/asj/sjz036

- Koppa M, House R, Tobin V, et al. Suture material choice can increase risk of hypersensitivity in hand trauma patients. Eur J Plast Surg. 2023;46:239-243. doi:10.1007/s00238-022-01986-7

- Pandey S, Singh M, Singh K, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing non-absorbable polypropylene (Prolene®) and delayed absorbable polyglactin 910 (Vicryl®) suture material in mass closure of vertical laparotomy wounds. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:306-310. doi:10.1007/s12262-012-0492-x

- Parell GJ, Becker GD. Comparison of absorbable with nonabsorbable sutures in closure of facial skin wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003;5:488-490. doi:10.1001/archfaci.5.6.488

- Kim J, Singh Maan H, Cool AJ, et al. Fast absorbing gut suture versus cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in the epidermal closure of linear repairs following Mohs micrographic surgery. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:24-29.

- Niessen FB, Spauwen PH, Kon M. The role of suture material in hypertrophic scar formation: Monocryl vs. Vicryl-Rapide. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:254-260. doi:10.1097/00000637-199709000-00006

- Fosko SW, Heap D. Surgical pearl: an economical means of skin closure with absorbable suture. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 pt 1):248-250. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70084-2

Melasma

THE COMPARISON

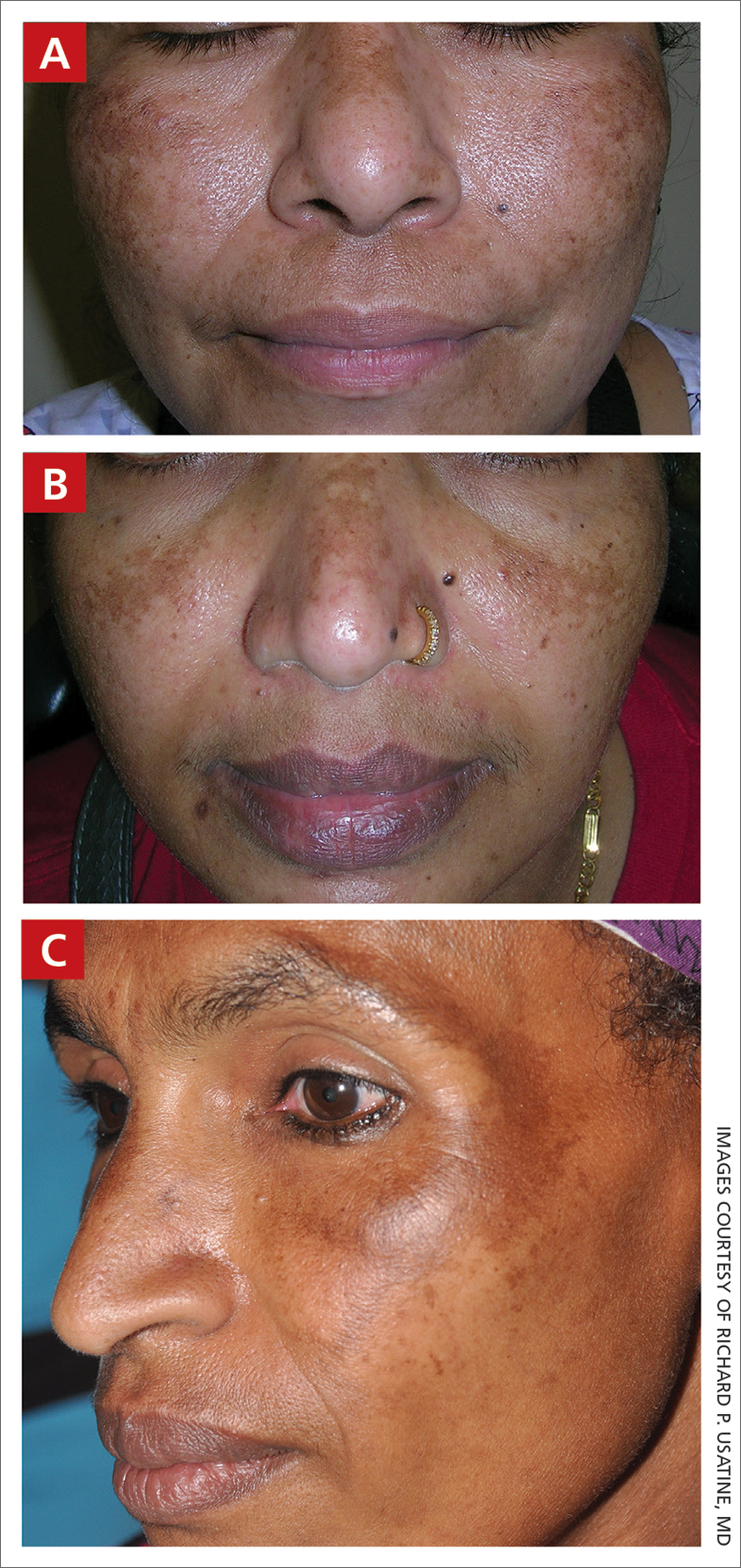

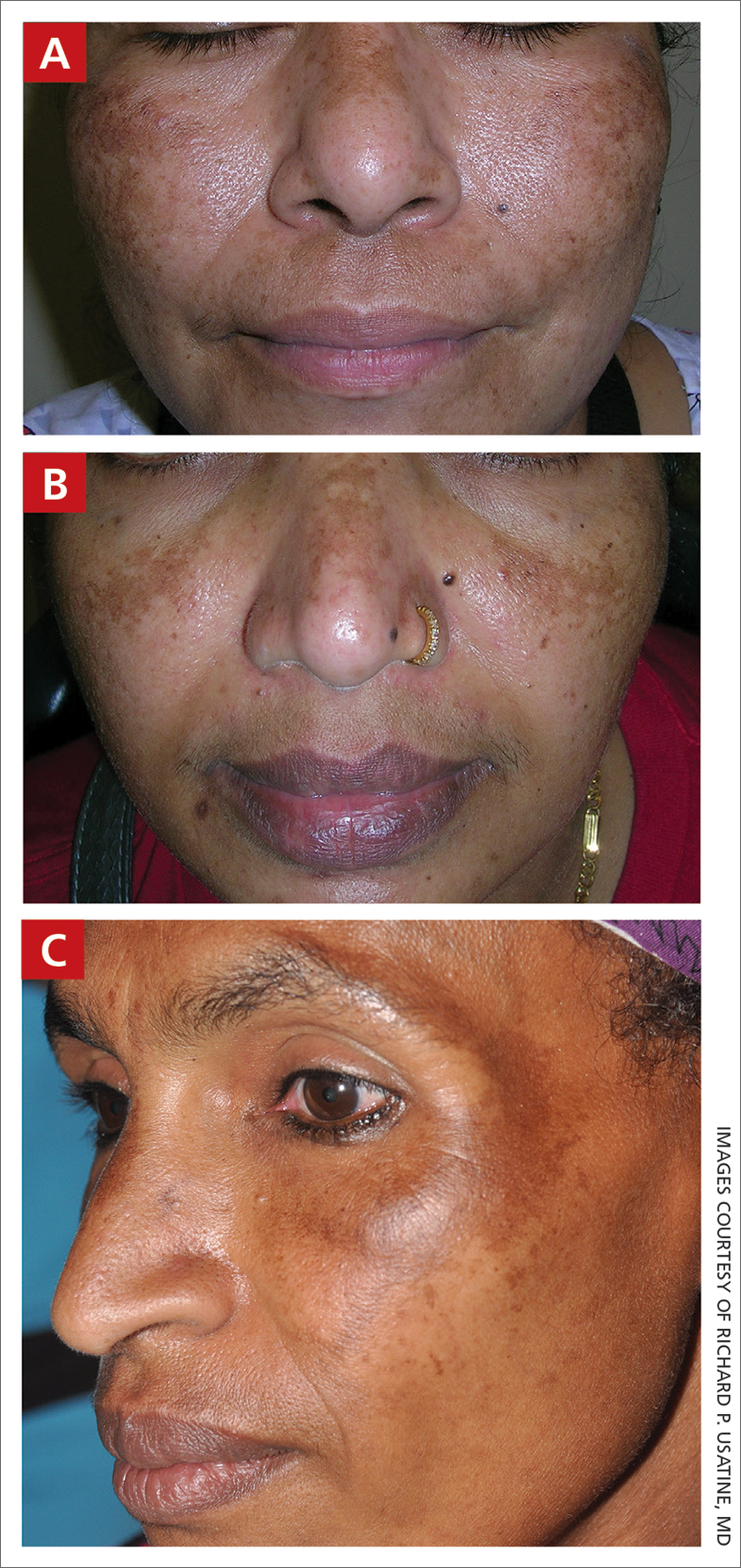

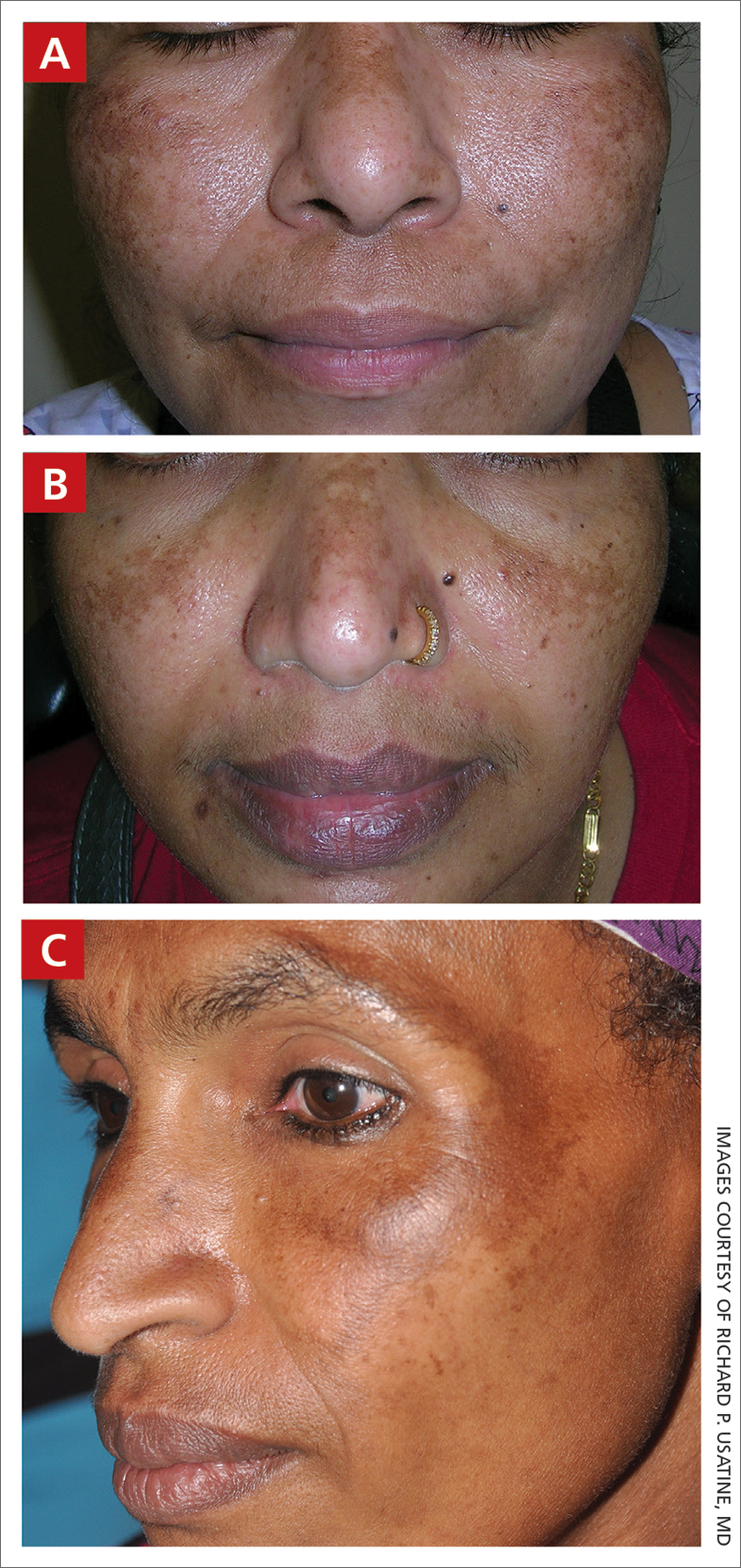

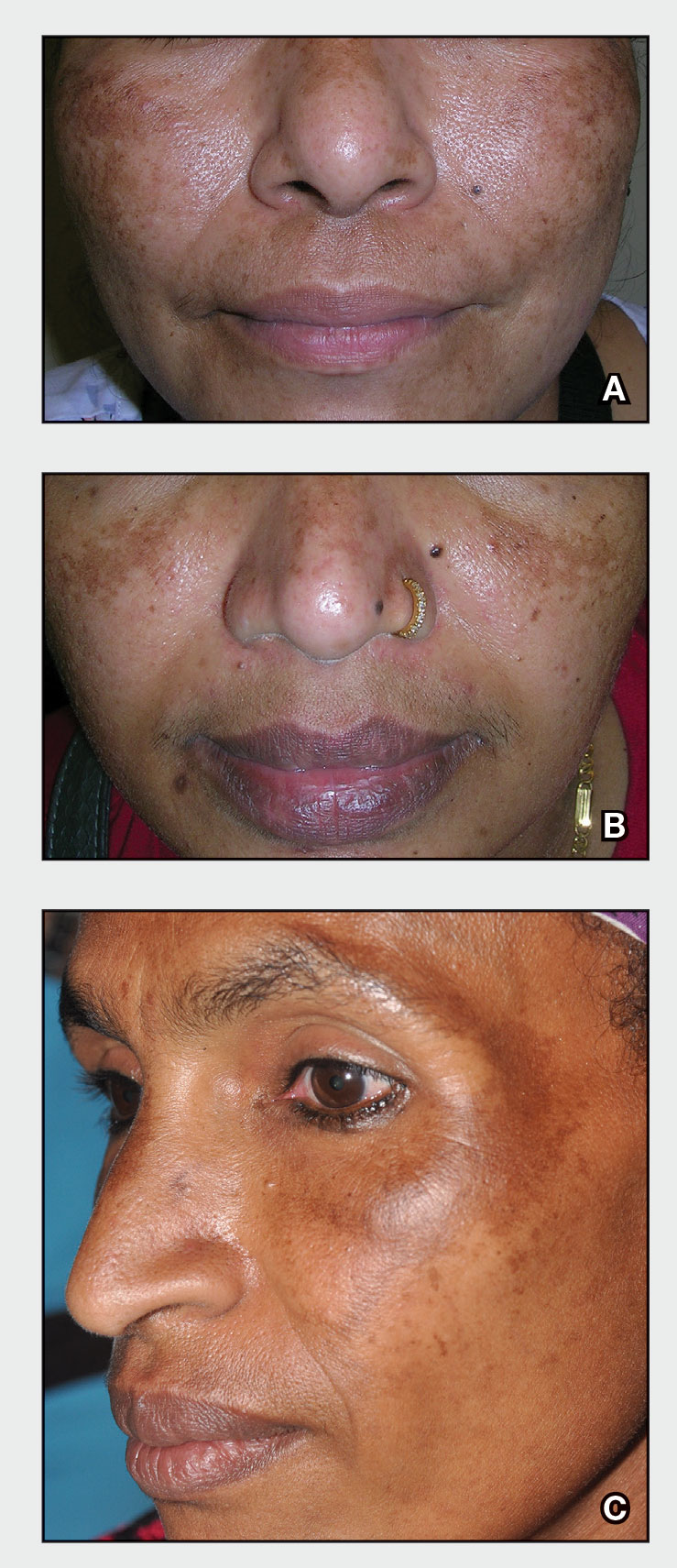

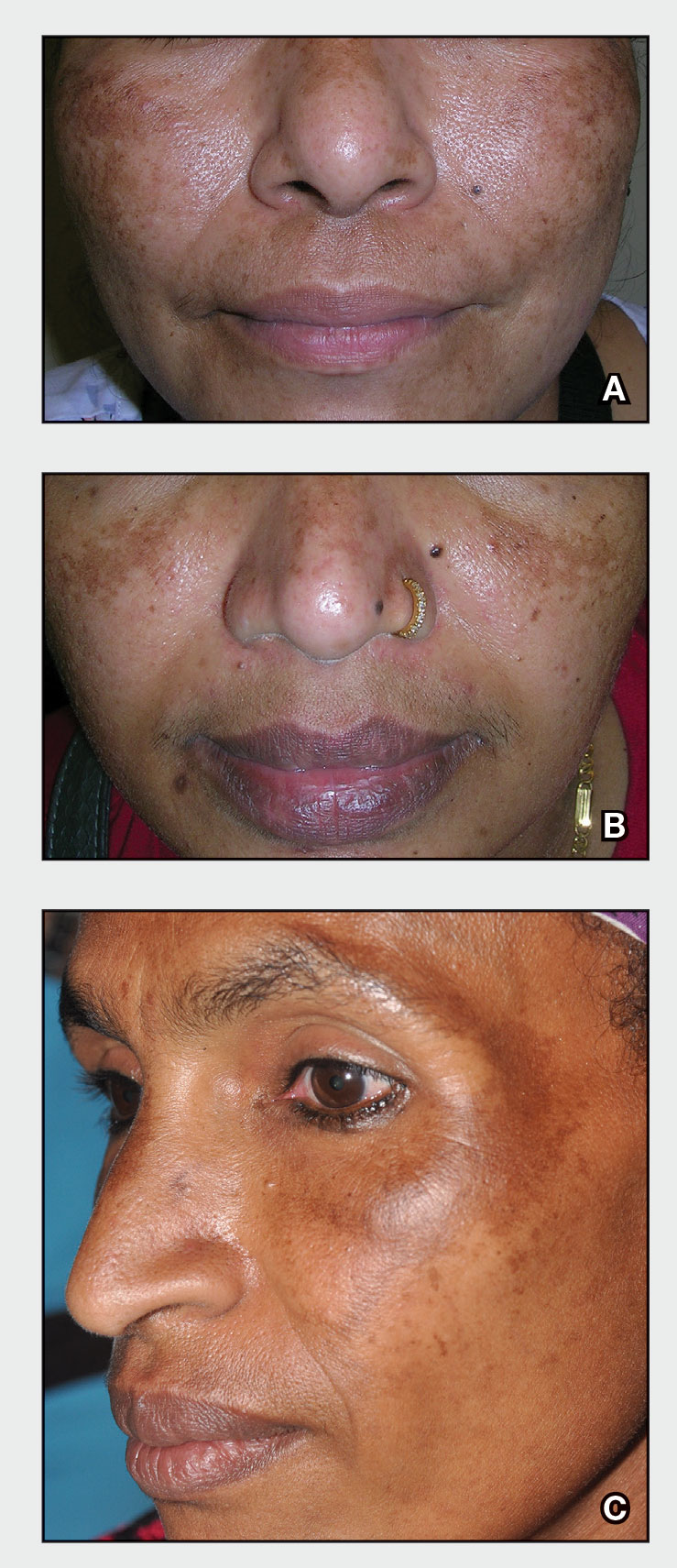

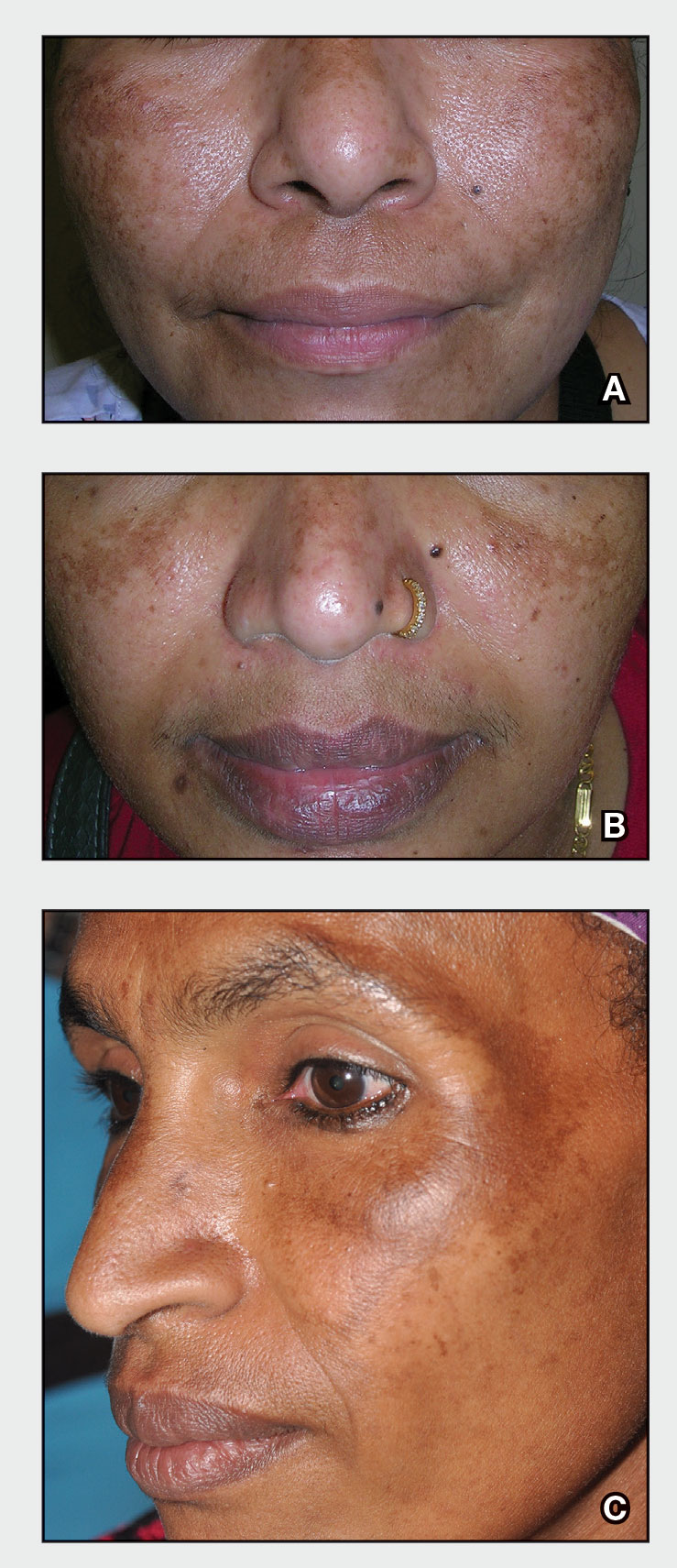

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women ages 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

- Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

- Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

- Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

- First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

- Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or a-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

- Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or secondline topical therapy.

- Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots, and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

- Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

- Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and self-esteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out of pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

1. Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

2. Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

3. Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

4. Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

5. Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

6. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

7. Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(3). doi:10.1111/dth.12465

8. Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

9. Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

10. Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

11. Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

12. Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

13. Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone/tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women ages 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

- Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

- Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

- Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

- First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

- Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or a-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

- Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or secondline topical therapy.

- Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots, and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

- Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

- Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and self-esteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out of pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women ages 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

- Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

- Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

- Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

- First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

- Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or a-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

- Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or secondline topical therapy.

- Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots, and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

- Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

- Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and self-esteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out of pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

1. Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

2. Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

3. Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

4. Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

5. Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

6. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

7. Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(3). doi:10.1111/dth.12465

8. Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

9. Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

10. Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

11. Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

12. Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

13. Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone/tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

1. Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

2. Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

3. Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

4. Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

5. Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

6. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

7. Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(3). doi:10.1111/dth.12465

8. Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

9. Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

10. Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

11. Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

12. Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

13. Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone/tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

Melasma

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

The Power of a Multidisciplinary Tumor Board: Managing Unresectable and/or High-Risk Skin Cancers

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Improved Workup and Diagnosis

One of the values of a tumor board is that it allows for patient data to be collected and assembled in a way that tells a story. The specialist from each field can then discuss and weigh the benefits and risks for each diagnostic test that should be performed for the workup in each patient. Physicians who refer their patients to the tumor board use their recommendations to both confirm the diagnosis and shift their treatment plans, depending on the information presented during the meeting.1 There may be a change in the tumor type, decision to refer for surgery, cancer staging, and list of viable options, especially after reviewing pathology and imaging.2 The discussion of the treatment plan may consider not only surgical considerations but also the patient’s quality of life. At times, noninvasive interventions are more appropriate and align with the patient’s goals of care. In addition, during the tumor board clinic there may be new tumors that are identified and biopsied, providing increased diagnosis and surveillance for patients who may have a higher risk for developing skin cancer.

Education for Residents and Providers

The multidisciplinary tumor board not only helps patients but also educates both residents and providers on the evidence-based therapeutic management of high-risk tumors.2 Research literature on cutaneous oncology is dynamic, and the weekly tumor board meetings help providers stay informed about the best and most effective treatments for their patients.3 In addition to the attending specialists, participants of the tumor board also may include residents, medical students, medical assistance staff, nurses, physician assistants, and fellows. Furthermore, the recommendations given by the tumor board serve to educate both the patient and the provider who referred them to the tumor board. Although we have access to excellent dermatology textbooks as residents, the most impactful educational experience is seeing the patients in tumor board clinic and participating in the immensely educational discussions at the weekly conferences. Through this experience, I have learned that treatment plans should be personalized to the patient. There are many factors to take into consideration when deciphering what the best course of treatment will be for a patient. Sometimes the best option is Mohs micrographic surgery, while other times it may be scheduling several sessions of palliative radiation oncology. Treatment depends on the individual patient and their condition.

Coordination of Care

During a week that I was on call, I was consulted to biopsy a patient with a giant hemorrhagic basal cell carcinoma that caused substantial cheek and nose distortion as well as anemia secondary to acute blood loss. The patient not only did not have a dermatologist but also did not have a primary care physician given he had not had contact with the health care system in more than 30 years. The reason for him not seeking care was multifactorial, but the approach to his care became multidisciplinary. We sought to connect him with the right providers to help him in any way that we could. We presented him at our multidisciplinary tumor board and started him on sonedigib, a medication that binds to and inhibits the smoothened protein.4 Through the tumor board, we were able to establish sustained contact with the patient. The tumor board created effective communication between providers to get him the referrals that he needed for dermatology, pathology, radiation oncology, hematology/oncology, and otolaryngology. The discussions centered around being cognizant of the patient’s apprehension with the health care system as well as providing medical and surgical treatment that would help his quality of life. We built a consensus on what the best plan was for the patient and his family. This consensus would have been more difficult had it not been for the combined specialties of the tumor board. In general, studies have shown that weekly tumor boards have resulted in decreased mortality rates for patients with advanced cancers.5

Final Thoughts

The multidisciplinary tumor board is a powerful resource for hospitals and the greater medical community. At these weekly conferences you realize there may still be hope that begins at the line where your expertise ends. It represents a team of providers who compassionately refuse to give up on patients when they are the last refuge.

- Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:E895.

- El Saghir NS, Charara RN, Kreidieh FY, et al. Global practice and efficiency of multidisciplinary tumor boards: results of an American Society of Clinical Oncology international survey. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1:57-64.

- Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, et al. Tumor board conferences for multidisciplinary skin cancer management: a survey of US cancer centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1209-1215.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1944-1956.

- Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:E267-E278.

Multidisciplinary tumor boards are composed of providers from many fields who deliver coordinated care for patients with unresectable and high-risk skin cancers. Providers who comprise the tumor board often are radiation oncologists, hematologists/oncologists, general surgeons, dermatologists, dermatologic surgeons, and pathologists. The benefit of having a tumor board is that each patient is evaluated simultaneously by a group of physicians from various specialties who bring diverse perspectives that will contribute to the overall treatment plan. The cases often encompass high-risk tumors including unresectable basal cell carcinomas or invasive melanomas. By combining knowledge from each specialty in a team approach, the tumor board can effectively and holistically develop a care plan for each patient.

For the tumor board at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island), we often prepare a presentation with comprehensive details about the patient and tumor. During the presentation, we also propose a treatment plan prior to describing each patient at the weekly conference and amend the plans during the discussion. Tumor boards also provide a consulting role to the community and hospital providers in which patients are being referred by their primary provider and are seeking a second opinion or guidance.

In many ways, the tumor board is a multidisciplinary approach for patient advocacy in the form of treatment. These physicians meet on a regular basis to check on the patient’s progress and continually reevaluate how to have discussions about the patient’s care. There are many reasons why it is important to refer patients to a multidisciplinary tumor board.