User login

Papular Reticulated Rash

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

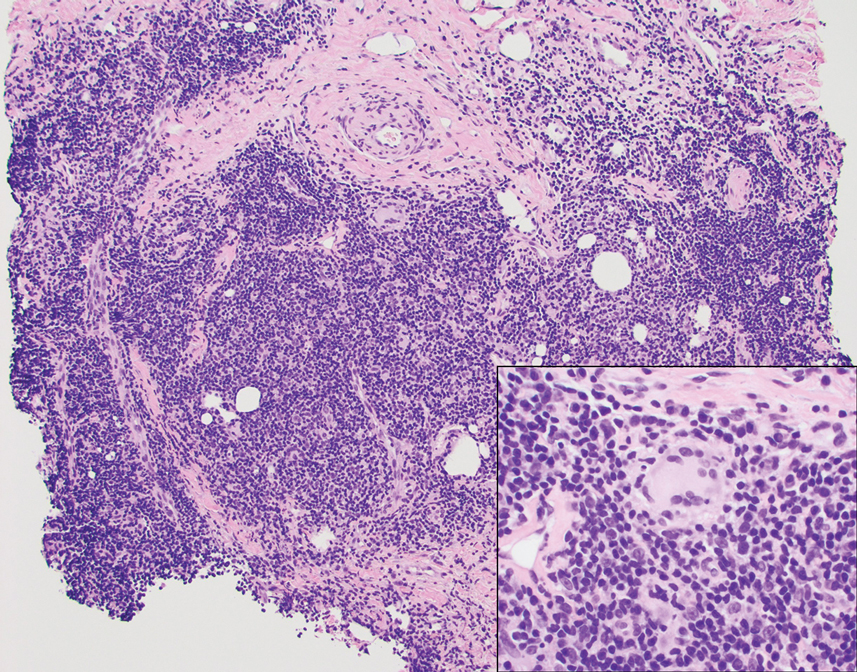

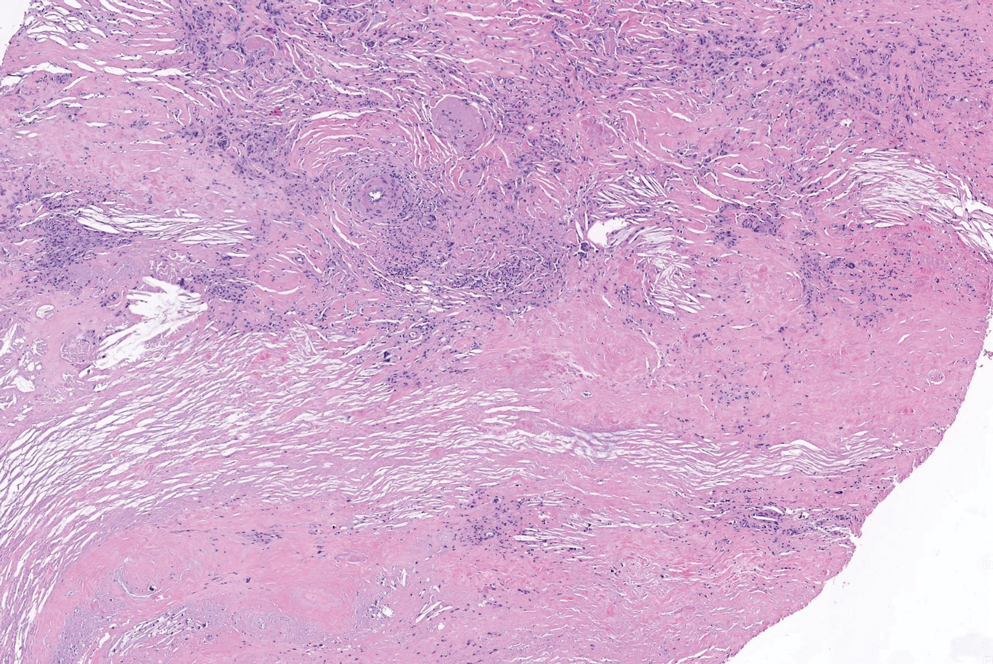

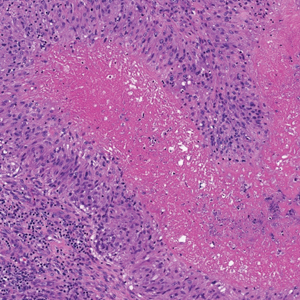

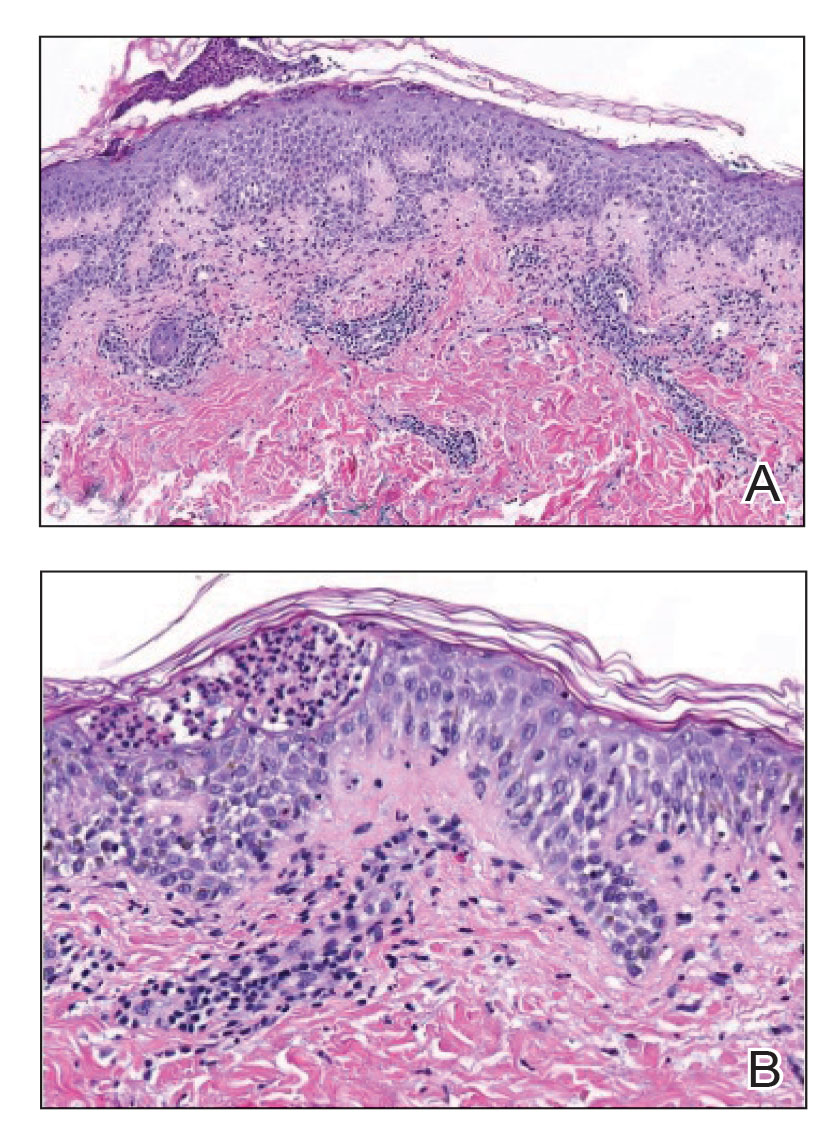

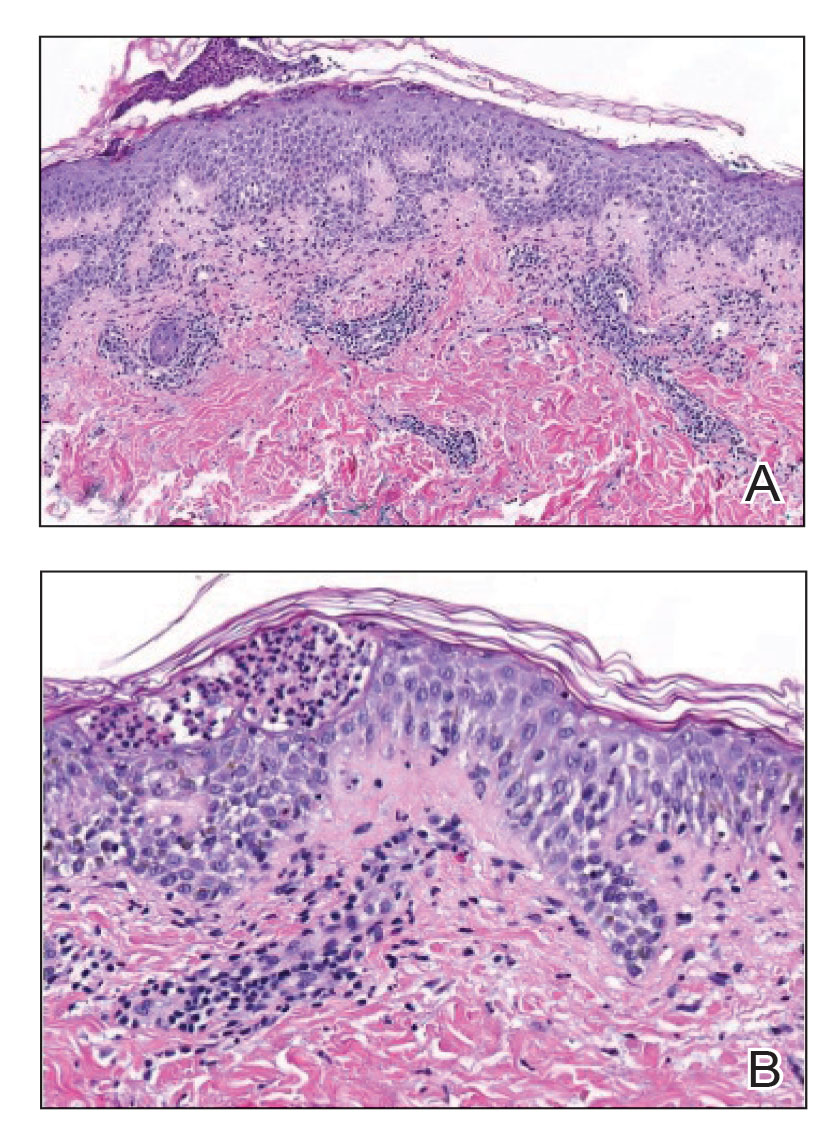

Histopathology of the punch biopsy revealed subcorneal collections of neutrophils flanked by a spongiotic epidermis with neutrophil and eosinophil exocytosis. Rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes were identified at the dermoepidermal junction, and grampositive bacterial organisms were seen in a follicular infundibulum with purulent inflammation. The dermis demonstrated a mildly dense superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and eosinophils (Figure).

Given the combination of clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa (PP) was rendered and a urinalysis was ordered, which confirmed ketonuria. The patient was started on minocycline 100 mg twice daily and was advised to reintroduce carbohydrates into her diet. Resolution of the inflammatory component of the rash was achieved at 3-week follow-up, with residual reticulated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare, albeit globally underrecognized, inflammatory dermatosis characterized by pruritic, symmetric, erythematous papules and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and rarely the arms and forehead that subsequently involute, leaving reticular postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.1 Prurigo pigmentosa is predominant in females (2.6:1 ratio). The mean age at presentation is 24.4 years, and it most commonly has been documented among populations in Asian countries, though it is unclear if a genetic predilection exists, as reports of PP are increasing globally with improved clinical awareness.1,2

The etiology of PP remains unknown; however, associations are well documented between PP and a ketogenic state secondary to uncontrolled diabetes, a low-carbohydrate diet, anorexia nervosa, or bariatric surgery.3 It is theorized that high serum ketones lead to perivascular ketone deposition, which induces neutrophil migration and chemotaxis,4 as substantiated by evidence of rash resolution with correction of the ketogenic state and improvement after administration of tetracyclines, a drug class known for neutrophil chemotaxis inhibition.5 Improvement of PP via these treatment mechanisms suggests that ketone bodies may play a role in the pathogenesis of PP.

Interestingly, Kafle et al6 reported that patients with PP commonly have bacterial colonies and associated inflammatory sequelae at the level of the hair follicles, which suggests that follicular involvement plays a role in the pathogenesis of PP. These findings are consistent with our patient’s histopathology consisting of gram-positive organisms and purulent inflammation at the infundibulum. The histopathologic features of PP are stage specific.1 Early stages are characterized by a superficial perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils that then spread to dermal papillae. Neutrophils then quickly sweep through the epidermis, causing spongiosis, ballooning, necrotic keratocytes, and consequent surface epithelium abscess formation. Over time, the dermal infiltrate assumes a lichenoid pattern as eosinophils and lymphocytes invade and predominate over neutrophils. Eventually, melanophages appear in the dermis as the epidermis undergoes hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and hyperpigmentation.1 The histologic differential diagnosis for PP is broad and varies based on the stage-specific progression of clinical and histopathologic findings.

Similar to PP, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has a female predominance and resolves with subsequent dyspigmentation; however, it initially is characterized by annular plaques with central clearing or papulosquamous lesions restricted to sun-exposed skin. Photosensitivity is a prominent feature, and roughly 50% of patients meet diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.7 Histopathology shows interface changes with increased dermal mucin and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Papular pityriasis rosea can present as a pruritic papular rash on the back and chest; however, it most commonly is associated with a herald patch and typically follows a flulike prodrome.8 Biopsy reveals mounds of parakeratosis with mild spongiosis, perivascular inflammation, and extravasated erythrocytes.

Galli-Galli disease can present as a pruritic rash with follicular papules under the breasts and other flexural areas but histopathologically shows elongated rete ridges with dermal melanosis and acantholysis.9

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly presents in the third decade of life and can manifest as painful, pruritic, vesicular lesions on erythematous skin distributed on the back, neck, and inframammary region, as seen in our case; however, it is histopathologically associated with widespread epidermal acantholysis unlike the findings seen in our patient.10

First-line treatment of PP includes antibiotics such as minocycline, doxycycline, and dapsone due to their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis. In patients with nutritional deficiencies or ketosis, reintroduction of carbohydrates alone has been effective.5,11

Prurigo pigmentosa is an underrecognized inflammatory dermatosis with a complex stage-dependent clinicopathologic presentation. Clinicians should be aware of the etiologic and histopathologic patterns of this unique dermatosis. Rash presentation in the context of a low-carbohydrate diet should prompt biopsy as well as treatment with antibiotics and dietary reintroduction of carbohydrates.

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- de Sousa Vargas TJ, Abreu Raposo CM, Lima RB, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: report of 3 cases from Brazil and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:267-274. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000643

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79. doi:10.1016/J .JDIN.2021.03.003

- Beutler BD, Cohen PR, Lee RA. Prurigo pigmentosa: literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:533-543. doi:10.1007/S40257-015-0154-4

- Chiam LYT, Goh BK, Lim KS, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a report of two cases that responded to minocycline. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2230.2009.03253.X

- Kafle SU, Swe SM, Hsiao PF, et al. Folliculitis in prurigo pigmentosa: a proposed pathogenesis based on clinical and pathological observation. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:20-27. doi:10.1111/CUP.12829

- Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263. doi:10.1016/J .AUTREV.2004.10.00

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:201-211. doi:10.2174/15733963166662 00923161330

- Sprecher E, Indelman M, Khamaysi Z, et al. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:572-574. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.2006.07703.X

- Burge SM. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:275-282. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1992.TB00658

- Lu L-Y, Chen C-B. Keto rash: ketoacidosis-induced prurigo pigmentosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.019

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

Histopathology of the punch biopsy revealed subcorneal collections of neutrophils flanked by a spongiotic epidermis with neutrophil and eosinophil exocytosis. Rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes were identified at the dermoepidermal junction, and grampositive bacterial organisms were seen in a follicular infundibulum with purulent inflammation. The dermis demonstrated a mildly dense superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and eosinophils (Figure).

Given the combination of clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa (PP) was rendered and a urinalysis was ordered, which confirmed ketonuria. The patient was started on minocycline 100 mg twice daily and was advised to reintroduce carbohydrates into her diet. Resolution of the inflammatory component of the rash was achieved at 3-week follow-up, with residual reticulated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare, albeit globally underrecognized, inflammatory dermatosis characterized by pruritic, symmetric, erythematous papules and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and rarely the arms and forehead that subsequently involute, leaving reticular postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.1 Prurigo pigmentosa is predominant in females (2.6:1 ratio). The mean age at presentation is 24.4 years, and it most commonly has been documented among populations in Asian countries, though it is unclear if a genetic predilection exists, as reports of PP are increasing globally with improved clinical awareness.1,2

The etiology of PP remains unknown; however, associations are well documented between PP and a ketogenic state secondary to uncontrolled diabetes, a low-carbohydrate diet, anorexia nervosa, or bariatric surgery.3 It is theorized that high serum ketones lead to perivascular ketone deposition, which induces neutrophil migration and chemotaxis,4 as substantiated by evidence of rash resolution with correction of the ketogenic state and improvement after administration of tetracyclines, a drug class known for neutrophil chemotaxis inhibition.5 Improvement of PP via these treatment mechanisms suggests that ketone bodies may play a role in the pathogenesis of PP.

Interestingly, Kafle et al6 reported that patients with PP commonly have bacterial colonies and associated inflammatory sequelae at the level of the hair follicles, which suggests that follicular involvement plays a role in the pathogenesis of PP. These findings are consistent with our patient’s histopathology consisting of gram-positive organisms and purulent inflammation at the infundibulum. The histopathologic features of PP are stage specific.1 Early stages are characterized by a superficial perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils that then spread to dermal papillae. Neutrophils then quickly sweep through the epidermis, causing spongiosis, ballooning, necrotic keratocytes, and consequent surface epithelium abscess formation. Over time, the dermal infiltrate assumes a lichenoid pattern as eosinophils and lymphocytes invade and predominate over neutrophils. Eventually, melanophages appear in the dermis as the epidermis undergoes hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and hyperpigmentation.1 The histologic differential diagnosis for PP is broad and varies based on the stage-specific progression of clinical and histopathologic findings.

Similar to PP, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has a female predominance and resolves with subsequent dyspigmentation; however, it initially is characterized by annular plaques with central clearing or papulosquamous lesions restricted to sun-exposed skin. Photosensitivity is a prominent feature, and roughly 50% of patients meet diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.7 Histopathology shows interface changes with increased dermal mucin and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Papular pityriasis rosea can present as a pruritic papular rash on the back and chest; however, it most commonly is associated with a herald patch and typically follows a flulike prodrome.8 Biopsy reveals mounds of parakeratosis with mild spongiosis, perivascular inflammation, and extravasated erythrocytes.

Galli-Galli disease can present as a pruritic rash with follicular papules under the breasts and other flexural areas but histopathologically shows elongated rete ridges with dermal melanosis and acantholysis.9

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly presents in the third decade of life and can manifest as painful, pruritic, vesicular lesions on erythematous skin distributed on the back, neck, and inframammary region, as seen in our case; however, it is histopathologically associated with widespread epidermal acantholysis unlike the findings seen in our patient.10

First-line treatment of PP includes antibiotics such as minocycline, doxycycline, and dapsone due to their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis. In patients with nutritional deficiencies or ketosis, reintroduction of carbohydrates alone has been effective.5,11

Prurigo pigmentosa is an underrecognized inflammatory dermatosis with a complex stage-dependent clinicopathologic presentation. Clinicians should be aware of the etiologic and histopathologic patterns of this unique dermatosis. Rash presentation in the context of a low-carbohydrate diet should prompt biopsy as well as treatment with antibiotics and dietary reintroduction of carbohydrates.

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

Histopathology of the punch biopsy revealed subcorneal collections of neutrophils flanked by a spongiotic epidermis with neutrophil and eosinophil exocytosis. Rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes were identified at the dermoepidermal junction, and grampositive bacterial organisms were seen in a follicular infundibulum with purulent inflammation. The dermis demonstrated a mildly dense superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and eosinophils (Figure).

Given the combination of clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa (PP) was rendered and a urinalysis was ordered, which confirmed ketonuria. The patient was started on minocycline 100 mg twice daily and was advised to reintroduce carbohydrates into her diet. Resolution of the inflammatory component of the rash was achieved at 3-week follow-up, with residual reticulated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare, albeit globally underrecognized, inflammatory dermatosis characterized by pruritic, symmetric, erythematous papules and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and rarely the arms and forehead that subsequently involute, leaving reticular postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.1 Prurigo pigmentosa is predominant in females (2.6:1 ratio). The mean age at presentation is 24.4 years, and it most commonly has been documented among populations in Asian countries, though it is unclear if a genetic predilection exists, as reports of PP are increasing globally with improved clinical awareness.1,2

The etiology of PP remains unknown; however, associations are well documented between PP and a ketogenic state secondary to uncontrolled diabetes, a low-carbohydrate diet, anorexia nervosa, or bariatric surgery.3 It is theorized that high serum ketones lead to perivascular ketone deposition, which induces neutrophil migration and chemotaxis,4 as substantiated by evidence of rash resolution with correction of the ketogenic state and improvement after administration of tetracyclines, a drug class known for neutrophil chemotaxis inhibition.5 Improvement of PP via these treatment mechanisms suggests that ketone bodies may play a role in the pathogenesis of PP.

Interestingly, Kafle et al6 reported that patients with PP commonly have bacterial colonies and associated inflammatory sequelae at the level of the hair follicles, which suggests that follicular involvement plays a role in the pathogenesis of PP. These findings are consistent with our patient’s histopathology consisting of gram-positive organisms and purulent inflammation at the infundibulum. The histopathologic features of PP are stage specific.1 Early stages are characterized by a superficial perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils that then spread to dermal papillae. Neutrophils then quickly sweep through the epidermis, causing spongiosis, ballooning, necrotic keratocytes, and consequent surface epithelium abscess formation. Over time, the dermal infiltrate assumes a lichenoid pattern as eosinophils and lymphocytes invade and predominate over neutrophils. Eventually, melanophages appear in the dermis as the epidermis undergoes hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and hyperpigmentation.1 The histologic differential diagnosis for PP is broad and varies based on the stage-specific progression of clinical and histopathologic findings.

Similar to PP, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has a female predominance and resolves with subsequent dyspigmentation; however, it initially is characterized by annular plaques with central clearing or papulosquamous lesions restricted to sun-exposed skin. Photosensitivity is a prominent feature, and roughly 50% of patients meet diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.7 Histopathology shows interface changes with increased dermal mucin and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Papular pityriasis rosea can present as a pruritic papular rash on the back and chest; however, it most commonly is associated with a herald patch and typically follows a flulike prodrome.8 Biopsy reveals mounds of parakeratosis with mild spongiosis, perivascular inflammation, and extravasated erythrocytes.

Galli-Galli disease can present as a pruritic rash with follicular papules under the breasts and other flexural areas but histopathologically shows elongated rete ridges with dermal melanosis and acantholysis.9

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly presents in the third decade of life and can manifest as painful, pruritic, vesicular lesions on erythematous skin distributed on the back, neck, and inframammary region, as seen in our case; however, it is histopathologically associated with widespread epidermal acantholysis unlike the findings seen in our patient.10

First-line treatment of PP includes antibiotics such as minocycline, doxycycline, and dapsone due to their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis. In patients with nutritional deficiencies or ketosis, reintroduction of carbohydrates alone has been effective.5,11

Prurigo pigmentosa is an underrecognized inflammatory dermatosis with a complex stage-dependent clinicopathologic presentation. Clinicians should be aware of the etiologic and histopathologic patterns of this unique dermatosis. Rash presentation in the context of a low-carbohydrate diet should prompt biopsy as well as treatment with antibiotics and dietary reintroduction of carbohydrates.

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- de Sousa Vargas TJ, Abreu Raposo CM, Lima RB, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: report of 3 cases from Brazil and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:267-274. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000643

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79. doi:10.1016/J .JDIN.2021.03.003

- Beutler BD, Cohen PR, Lee RA. Prurigo pigmentosa: literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:533-543. doi:10.1007/S40257-015-0154-4

- Chiam LYT, Goh BK, Lim KS, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a report of two cases that responded to minocycline. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2230.2009.03253.X

- Kafle SU, Swe SM, Hsiao PF, et al. Folliculitis in prurigo pigmentosa: a proposed pathogenesis based on clinical and pathological observation. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:20-27. doi:10.1111/CUP.12829

- Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263. doi:10.1016/J .AUTREV.2004.10.00

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:201-211. doi:10.2174/15733963166662 00923161330

- Sprecher E, Indelman M, Khamaysi Z, et al. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:572-574. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.2006.07703.X

- Burge SM. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:275-282. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1992.TB00658

- Lu L-Y, Chen C-B. Keto rash: ketoacidosis-induced prurigo pigmentosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.019

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- de Sousa Vargas TJ, Abreu Raposo CM, Lima RB, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: report of 3 cases from Brazil and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:267-274. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000643

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79. doi:10.1016/J .JDIN.2021.03.003

- Beutler BD, Cohen PR, Lee RA. Prurigo pigmentosa: literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:533-543. doi:10.1007/S40257-015-0154-4

- Chiam LYT, Goh BK, Lim KS, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a report of two cases that responded to minocycline. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2230.2009.03253.X

- Kafle SU, Swe SM, Hsiao PF, et al. Folliculitis in prurigo pigmentosa: a proposed pathogenesis based on clinical and pathological observation. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:20-27. doi:10.1111/CUP.12829

- Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263. doi:10.1016/J .AUTREV.2004.10.00

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:201-211. doi:10.2174/15733963166662 00923161330

- Sprecher E, Indelman M, Khamaysi Z, et al. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:572-574. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.2006.07703.X

- Burge SM. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:275-282. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1992.TB00658

- Lu L-Y, Chen C-B. Keto rash: ketoacidosis-induced prurigo pigmentosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.019

An otherwise healthy 22-year-old woman presented with a painful eruption with burning and pruritus that had been slowly worsening as it spread over the last 4 weeks. The rash first appeared on the lower chest and inframammary folds (top) and spread to the upper chest, neck, back (bottom), arms, and lower face. Physical examination revealed multiple illdefined, erythematous papules, patches, and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and upper abdomen. Individual lesions coalesced into plaques that displayed a reticular configuration. There were no lesions in the axillae. The patient had been following a low-carbohydrate diet for 4 months. A punch biopsy was performed.

Erythematous Papules on the Ears

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

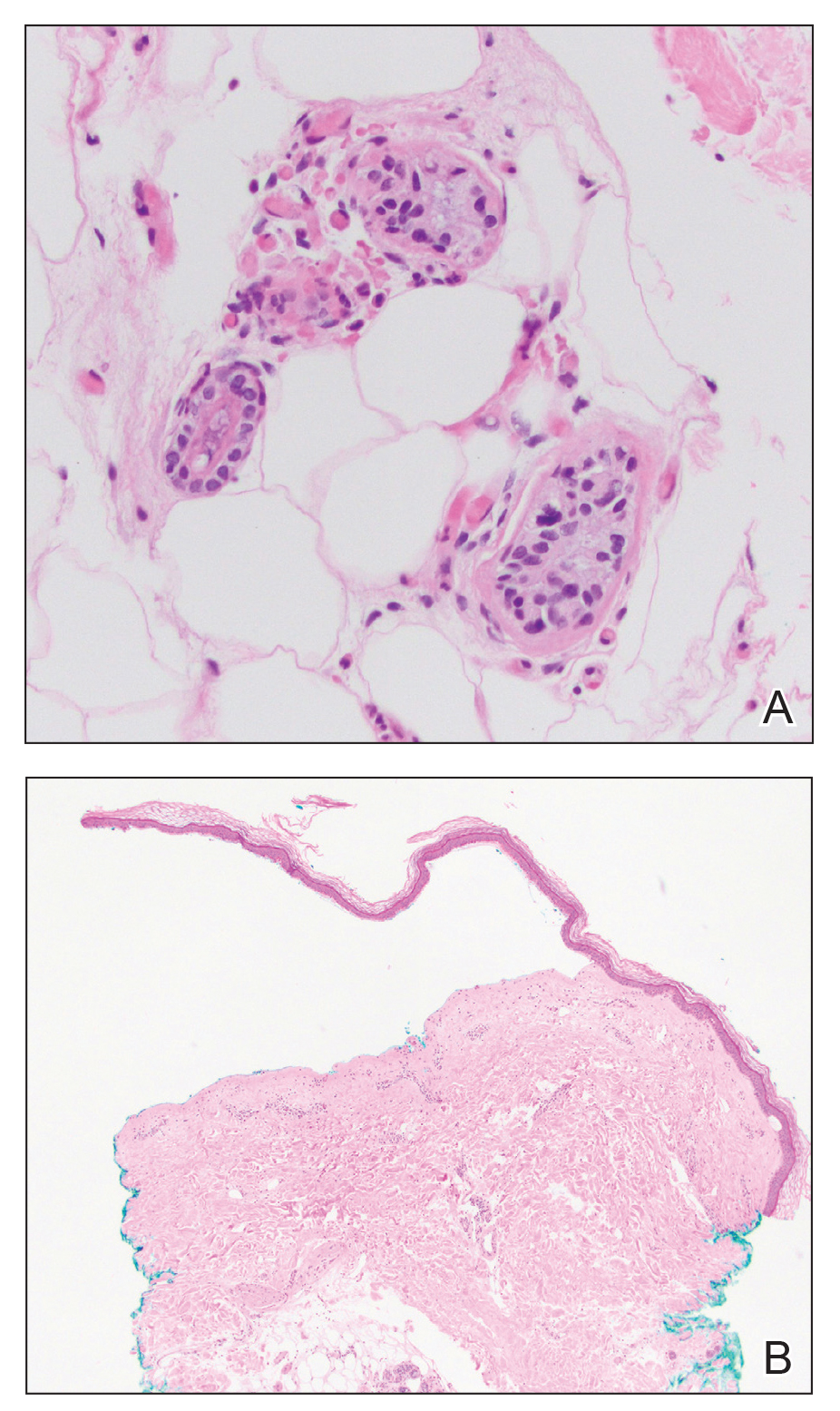

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

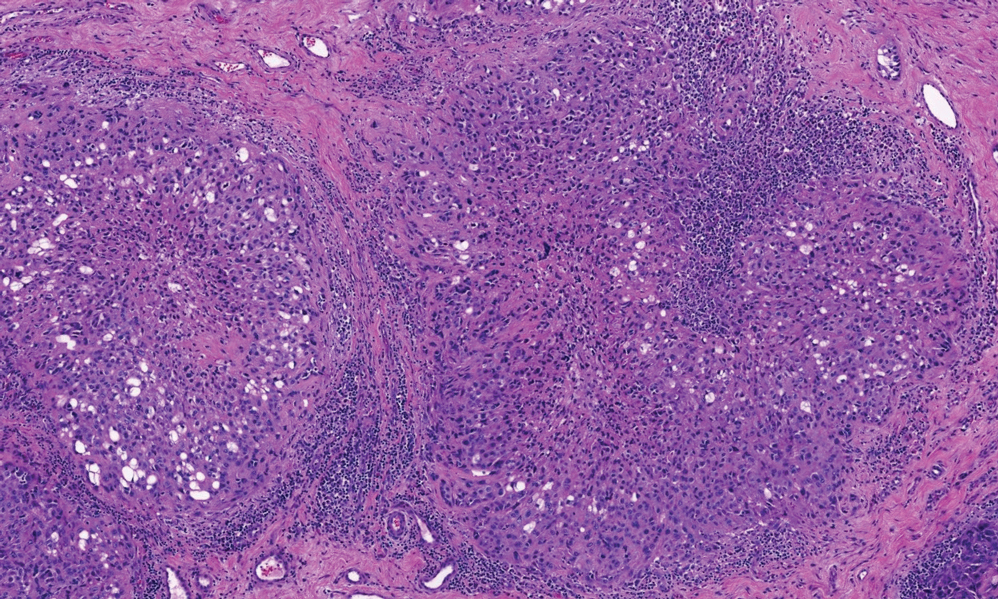

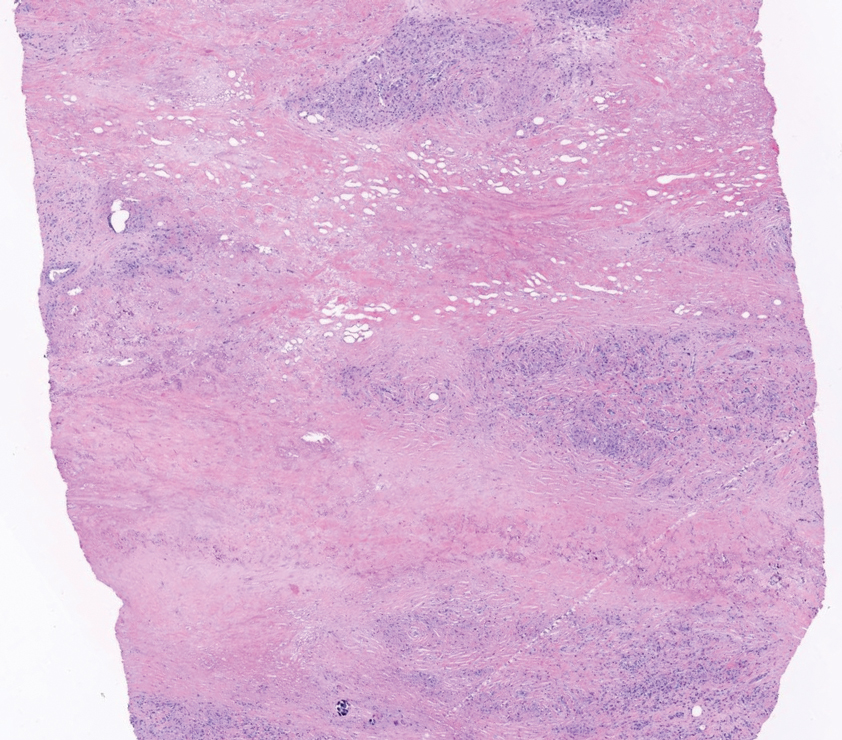

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

A 53-year-old man with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with pain and redness of the lobules of both ears of 9 months’ duration. He had no known allergies and took no medications. He lived in suburban Virginia and had not recently traveled outside of the region. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous and edematous nodules on the lobules of both ears (top). There was no evidence of arthritis or neurologic deficits. A punch biopsy was performed (bottom).

Ulcerating Nodule on the Foot

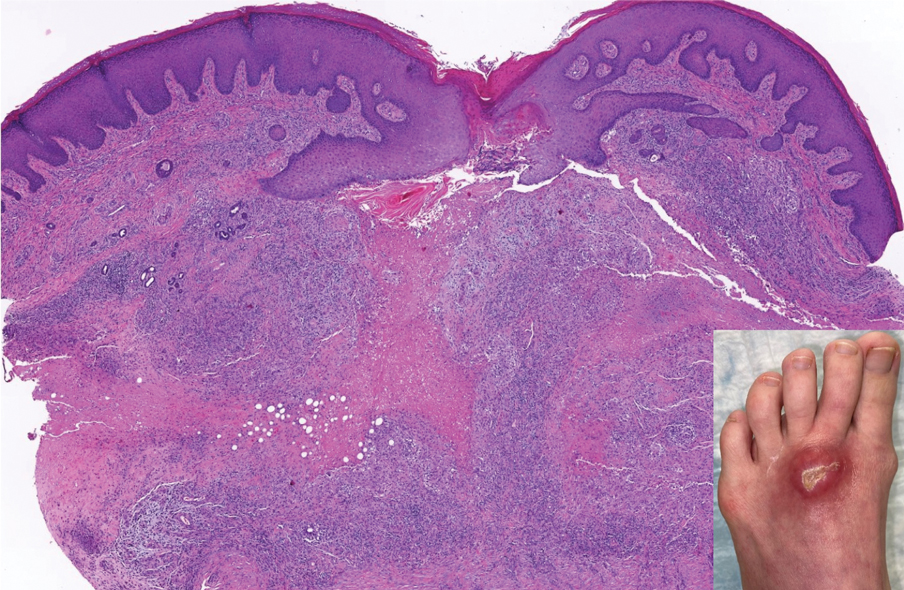

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

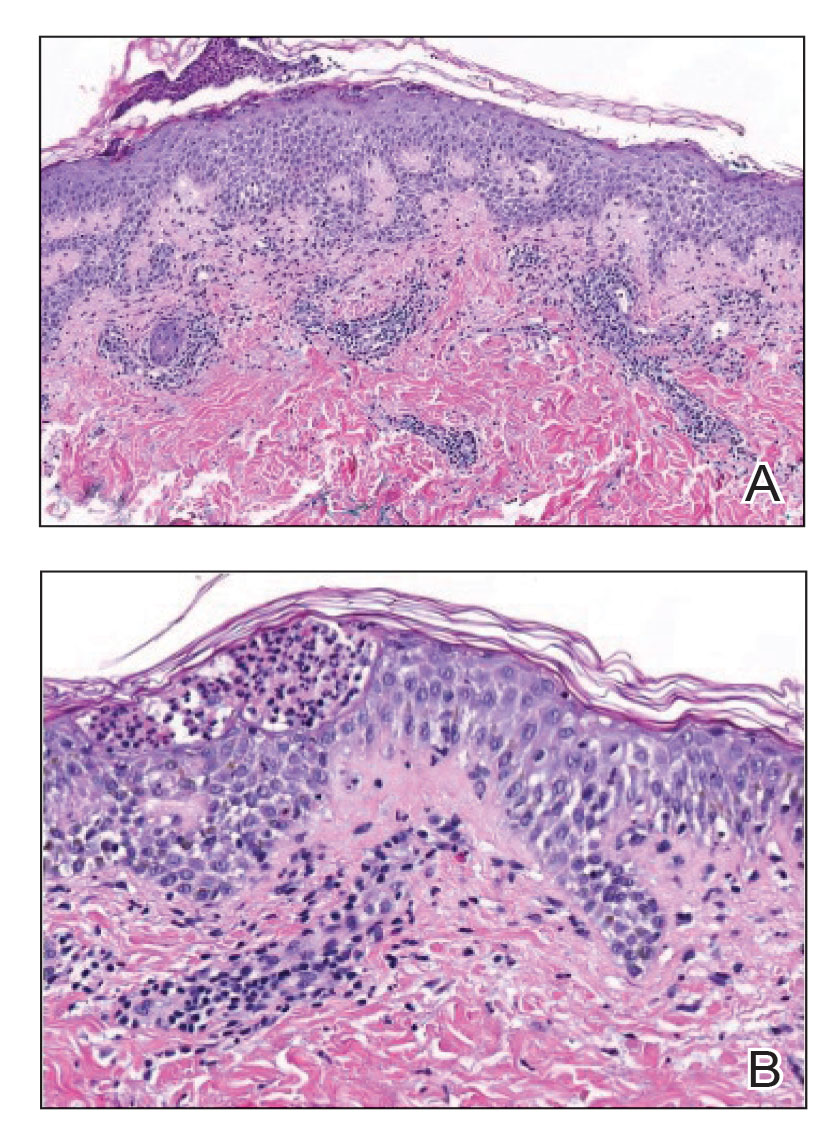

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

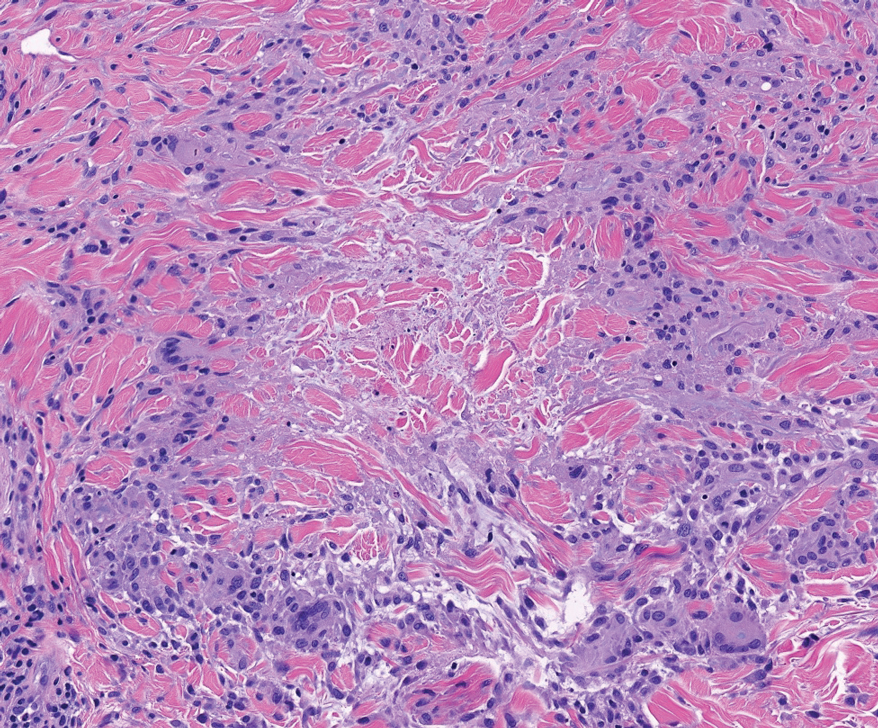

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

A 59-year-old woman with a history of joint pain presented with a foot nodule that developed over the course of 2 years. Physical examination revealed a firm, mobile, mildly tender, 3-cm, deep red nodule on the dorsal aspect of the left foot (top [inset]) with an overlying central epidermal defect and thick keratinaceous debris. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Empiric treatments with oral antibiotics and intralesional corticosteroids were unsuccessful. Incisional biopsy was performed for histologic review, and tissue culture studies were negative.

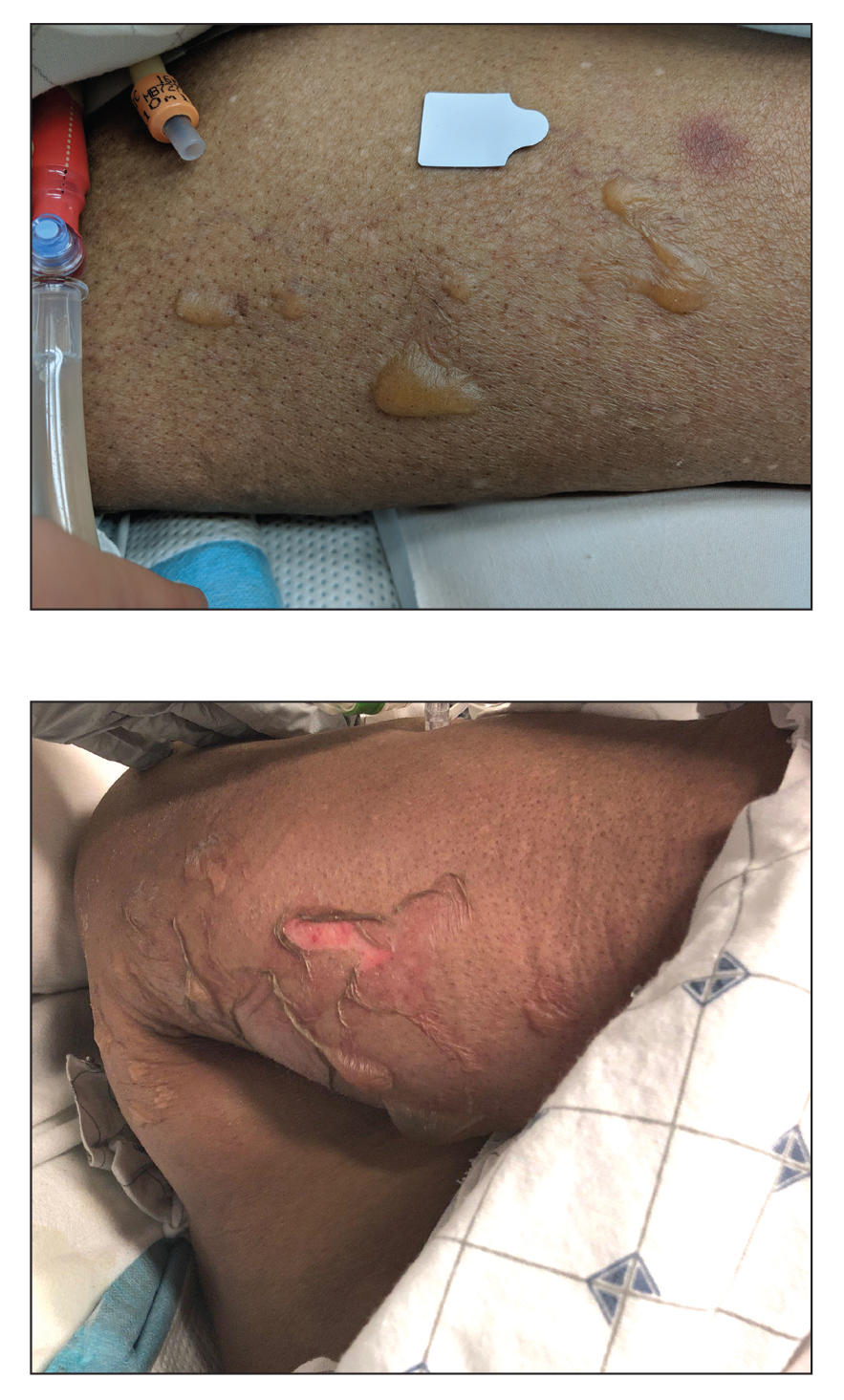

Blisters in a Comatose Elderly Woman

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

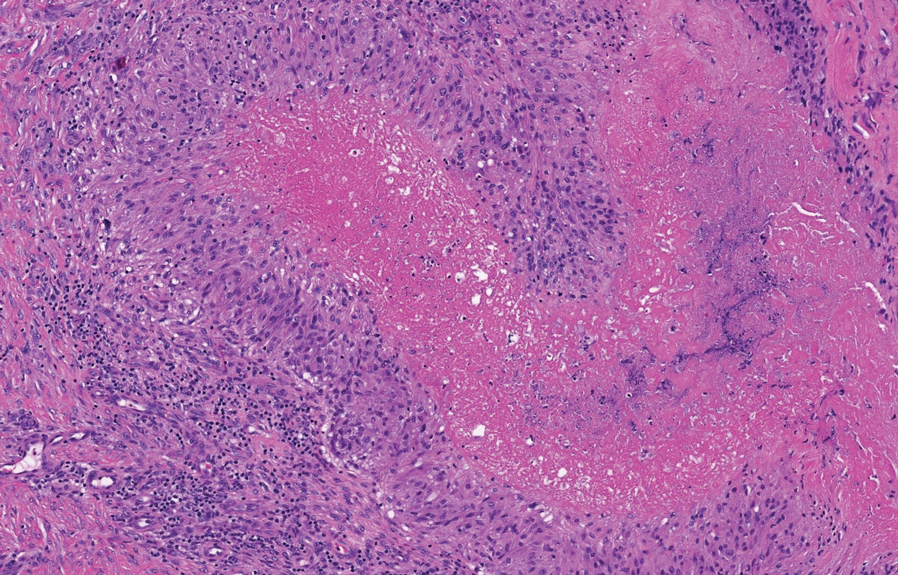

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.