User login

Risk of Cancer-Associated Thrombosis and Bleeding in Veterans With Malignancy Who Are Receiving Direct Oral Anticoagulants (FULL)

Patients with cancer are at an increased risk of both venous thromboembolism (VTE) and bleeding complications. Risk factors for development of cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) include indwelling lines, antineoplastic therapies, lack of mobility, and physical/chemical damage from the tumor.1 Venous thromboembolism may manifest as either deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). Cancer-associated thrombosis can lead to significant mortality in patients with cancer and may increase health care costs for additional medications and hospitalizations.

Zullig and colleagues estimated that 46,666 veterans received cancer care from the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) health care system in 2010. This number equates to about 3% of all patients with cancer in the US who receive at least some of their health care from the VA health care system.2 In addition to cancer care, these veterans receive treatment for various comorbid conditions. One such condition that is of concern in a prothrombotic state is atrial fibrillation (AF). For this condition, patients often require anticoagulation therapy with aspirin, warfarin, or one of the recently approved direct oral anticoagulant agents (DOACs), depending on risk factors.

Background

Due to their ease of administration, limited monitoring requirements, and proven safety and efficacy in patients with AF requiring anticoagulation, the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology recently switched their recommendations for rivaroxaban and dabigatran for oral stroke prevention to a class 1/level B recommendation.3

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends treatment with DOACs over warfarin therapy for acute VTE in patients without cancer; however, the ACCP prefers low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) over the DOACs for treatment of CAT.4 Recently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) updated its guidelines for the treatment of cancer-associated thromboembolic disease to recommend 2 of the DOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban) for treatment of acute VTE over warfarin. These guidelines also recommend LMWH over DOACs for treatment of acute VTE in patients with cancer.5 These NCCN recommendations are largely based on prespecified subgroup meta-analyses of the DOACs compared with those of LMWH or warfarin in the cancer population.

In addition to stroke prevention in patients with AF, DOACs have additional FDA-approved indications, including treatment of acute VTE, prevention of recurrent VTE, and postoperative VTE treatment and prophylaxis. Due to a lack of head-to-head, randomized controlled trials comparing LMWH with DOACs in patients with cancer, these agents have not found their formal place in the treatment or prevention of CAT. Several meta-analyses have suggested similar efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with cancer compared with those of LMWH.6-8 These meta-analysis studies largely looked at subpopulations and compared the outcomes with those of the landmark CLOT (Randomized Comparison of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer Investigators) and CATCH (Comparison of Acute Treatments in Cancer Hemostasis) trials.9,10

As it is still unclear whether the DOACs are effective and safe for treatment/prevention of CAT, some confusion remains regarding the best management of these at-risk patients. In patients with cancer on DOAC therapy for an approved indication, it is assumed that the therapeutic benefit seen in approved indications would translate to treatment and prevention of CAT. This study aims to determine the incidence of VTE and rates of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (CRNMB) in veterans with cancer who received a DOAC.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center chart review was approved by the local institutional review board and research safety committee. A search within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse identified patients who had an active prescription for one of the DOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban) along with an ICD 9 or ICD 10 code corresponding to a malignancy.

Patients were included in the final analysis if they were aged 18 to 89 years at time of DOAC receipt, undergoing active treatment for malignancy, had evidence of a history of malignancy (either diagnostic or charted evidence of previous treatment), or received cancer-related surgery within 30 days of DOAC prescription with curative intent. Patients were excluded from the final analysis if they did not receive a DOAC prescription or have any clear evidence of malignancy documented in the medical chart.

Patients’ charts were evaluated for the following clinical endpoints: patient age, height (cm), weight (kg), type of malignancy, type of treatment for malignancy, serum creatinine (SCr), creatinine clearance (CrCl) calculated with the Cockcroft-Gault equation using actual body weight, serum hemoglobin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, indication for DOAC, type of VTE, presence of a prior VTE, and diagnostic test performed for VTE. Major bleeding and CRNMB criteria were based on the definitions provided by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH).11 All laboratory values and demographic information were gathered at the time of initial DOAC prescription.

The primary endpoint for this study was incidence of VTE. The secondary endpoints included major bleeding and CRNMB. All data collection and statistical analysis were done using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Redmond, WA). Comparisons of data between trials were done using the chi-squared calculation.

Results

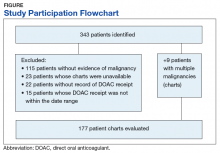

From initial FDA approval of dabigatran (first DOAC on the market) on October 15, 2012, to January 1, 2017, there were 343 patients who met initial inclusion criteria. Of those, 115 did not have any clear evidence of malignancy, 22 did not have any records of DOAC receipt, 15 did not receive a DOAC within the date range, and 23 patients’ charts were unavailable.

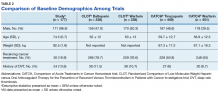

The majority of the patients were males (96.6%), with an average age of 74.5 years. The average weight of all patients was 92.5 kg, with an average SCr of 1.1 mg/dL. This equated to an average CrCl of 85.5 mL/min based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation using actual bodyweight. Of the 177 patients evaluated, 30 (16.9%) were receiving active cancer treatment at time of DOAC initiation.

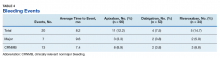

Two (1.1%) patients developed a VTE while receiving a DOAC.

Among the 177 evaluable patients in this study, there were 7 patients (4%) who developed a major bleed and 13 patients (7.3%) who developed a clinically relevant nonmajor bleed according to the definitions provided by ISTH.11

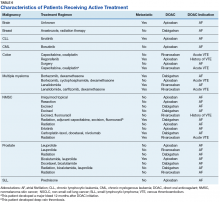

As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients were actively receiving treatment during DOAC administration. Most of the documented cases of malignancy were either a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) or prostate cancer. The most common method of treatment was surgical resection for both malignancies. Of the 30 patients who received active malignancy treatment while on a DOAC, there were 4 patients with multiple myeloma, 6 patients with NMSC, 4 patients with colon cancer, 1 patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), 1 patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), 1 patient with small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL), 4 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 1 patient with unspecified brain cancer, and 1 patient with breast cancer. The various characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 6.

Discussion

The CLOT and CATCH trials were chosen as historic comparators. Although the active treatment interventions and comparator arms were not similar between the patients included in this study and the CLOT and CATCH trials, the authors felt the comparison was appropriate as these trials were designed specifically for patients with malignancy. Additionally, these trials sought to assess rates of VTE formation and bleeding in the patient with malignancies—outcomes that aligned with this study. Alternative trials for comparison are the subgroup analyses of patients with malignancies in the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials.12-14 Although these trials were designed to stratify patients based on presence of malignancy, they were not powered to account for increased risk of VTE in patients with malignancies.

There are multiple risk factors that increase the risk of CAT. Khoranna and colleagues identified primary stomach, pancreas, brain, lung, lymphoma, gynecologic, bladder, testicular, and renal carcinomas as a high risk of VTE formation.15 Additionally, Khoranna and colleagues noted that elderly patients and patients actively receiving treatment are at an increased risk of VTE formation.15 The low rate of VTE formation (1.1%) in the patients in this study may be due to the low risk for VTE formation. As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients (16.9%) in this study were receiving active treatment.

Additionally, there were only 42 patients (23.7%) who had a high-risk malignancy. The increased age of the patient population (74.5 years old) in this study is one risk factor that could largely skew the risks of VTE formation in the patient population. In addition to age, the average body mass index (BMI) of this study’s patient population (30 kg/m2) may further increase risk of VTE. Although Khoranna and colleagues identified a BMI of 35 kg/m2 as the cutoff for increased risk of CAT, the increased risk based on a BMI of 30 kg/m2 cannot be ignored in the patients in this study.15

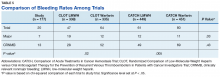

Another risk inherent in the treatment of patients with cancer is pancytopenia, which may lead to increased risks of bleeding and infection. When patients are exposed to an anticoagulant agent in the setting of decreased platelets and hemoglobin (from treatment or disease process), the risk for major bleeds and CRNMB are increased drastically. In this patient population, the combined rate of bleeding (11.3%) was relatively decreased compared with that of the CLOT (16.5% for all bleeding events) and CATCH (15.7% for all bleeding events) trials.9,10

Compared with the oncology subgroup analysis of the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials, the differences are more noticeable. The AMPLIFY trial reported a 1.1% incidence of bleeding in patients with cancer on apixaban, whereas the RE-COVER trial did not report bleeding rates, and the EINSTEIN trial reported a 14% incidence of bleeding in all patients with cancer on rivaroxaban for VTE treatment.12-14 This study found a bleeding incidence of 12.2% with apixaban, 5.7% with dabigatran, and 14.7% with rivaroxaban. In this trial the incidence of bleeding with rivaroxaban were similar; however, the incidence of bleeding with apixaban was markedly higher. There is no obvious explanation for this, as the dosing of apixaban was appropriate in all patients in this trial except for one. There was no documented bleed in this patient’s medical chart.

A meta-analysis conducted by Vedovati and colleagues identified 6 studies in which patients with cancer received either a DOAC (with or without a heparin product) or vitamin K antagonist.16 That analysis found a nonsignificant reduction in VTE recurrence (odds ratio [OR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31-1.1), major bleeding (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.41-1.44), and CRNMB (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.62-1.18).16 The meta-analysis adds to the growing body of evidence in support of both safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with cancer. Although the Vedovati and colleagues study does not directly compare rates between 2 treatment groups, the findings of similar rates of VTE recurrence, major bleed, and CRNMB are consistent with the current study. Despite differing patient characteristics, the meta-analysis by Vedovati and colleagues supports the ongoing use of DOACs in patients with malignancy, as does the current study.16

Limitations

Although it seems that apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban are effective in reducing the risk of VTE in veterans with malignancy, there are some inherent weaknesses in the current study. Most notably is the choice of comparator trials. The authors’ believe that the CLOT and CATCH trials were the most appropriate based on similarities in population and outcomes. Considering the CLOT and CATCH trials compared LMWH to coumarin products for treatment of VTE, future studies should compare use of these agents with DOACs in the cancer population. In addition, the study did not include outcomes that would adequately assess risks of VTE and bleeding formation. This information would have been beneficial to more effectively categorize this study’s patient population based on risks of each of its predetermined outcomes. Understanding safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients at various risks would help practitioners to choose more appropriate agents in practice. Last, this study did not assess the incidence of stroke in study patients. This is important because the DOACs were used mostly for stroke prevention in AF and atrial flutter. The increased risk of VTE in patients with cancer cannot directly correlate to risk of stroke with a comorbid cardiac condition, but the hypercoagulable state cannot be ignored in these patients.

Conclusion

This study provided some preliminary evidence for the safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with cancer. The low incidence of VTE formation and similar rates of bleeding among other clinical trials indicate that DOACs are safe alternatives to currently recommended anticoagulation medication in patients with cancer.

1. Motykie GD, Zebala LP, Caprini JA, et al. A guide to venous thromboembolism risk factor assessment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2000;9(3):253-262.

2. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891.

3. January CT, Wann S, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071-2104.

4. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease. Version 1.2018. https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/vte.pdf. Updated March 22, 2018. Accessed April 9, 2018.

6. Brunetti ND, Gesuete E, De Gennaro L, et al. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants compared to vitamin K inhibitors and low molecular weight heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:214-221.

7. Posch F, Konigsbrügge O, Zielinski C, Pabinger I, Ay C. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136(3):582-589.

8. van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middledorp S, Büller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood. 2014;124(12):1968-1975.

9. Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al; Randomized Comparison of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer (CLOT) Investigators. Low molecular weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-153.

10. Lee AY, Kamphuisen PW, Meyer G, et al; CATCH Investigators. Tinzaparin vs warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in patients with active cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(7):677-686.

11. Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation. Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):2119-2126.

12. Agnelli G, Büller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the AMPLIFY trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(12):2187-2191.

13. Schulman S, Goldhaber SZ, Kearon C, et al. Treatment with dabigatran or warfarin in patients with venous thromboembolism and cancer. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(1):150-157.

14. Prins MH, Lensing AW, Brighton TA, et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PF): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2014;1(1):e37-e46.

15. Khoranna AA, Connolly GC. Assessing risk of venous thromboembolism in the patient with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):4839-4847.

16. Vedovati MC, Germini F, Agnelli G, Becattini C. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with VTE and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2015;147(2):475-483.

Patients with cancer are at an increased risk of both venous thromboembolism (VTE) and bleeding complications. Risk factors for development of cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) include indwelling lines, antineoplastic therapies, lack of mobility, and physical/chemical damage from the tumor.1 Venous thromboembolism may manifest as either deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). Cancer-associated thrombosis can lead to significant mortality in patients with cancer and may increase health care costs for additional medications and hospitalizations.

Zullig and colleagues estimated that 46,666 veterans received cancer care from the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) health care system in 2010. This number equates to about 3% of all patients with cancer in the US who receive at least some of their health care from the VA health care system.2 In addition to cancer care, these veterans receive treatment for various comorbid conditions. One such condition that is of concern in a prothrombotic state is atrial fibrillation (AF). For this condition, patients often require anticoagulation therapy with aspirin, warfarin, or one of the recently approved direct oral anticoagulant agents (DOACs), depending on risk factors.

Background

Due to their ease of administration, limited monitoring requirements, and proven safety and efficacy in patients with AF requiring anticoagulation, the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology recently switched their recommendations for rivaroxaban and dabigatran for oral stroke prevention to a class 1/level B recommendation.3

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends treatment with DOACs over warfarin therapy for acute VTE in patients without cancer; however, the ACCP prefers low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) over the DOACs for treatment of CAT.4 Recently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) updated its guidelines for the treatment of cancer-associated thromboembolic disease to recommend 2 of the DOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban) for treatment of acute VTE over warfarin. These guidelines also recommend LMWH over DOACs for treatment of acute VTE in patients with cancer.5 These NCCN recommendations are largely based on prespecified subgroup meta-analyses of the DOACs compared with those of LMWH or warfarin in the cancer population.

In addition to stroke prevention in patients with AF, DOACs have additional FDA-approved indications, including treatment of acute VTE, prevention of recurrent VTE, and postoperative VTE treatment and prophylaxis. Due to a lack of head-to-head, randomized controlled trials comparing LMWH with DOACs in patients with cancer, these agents have not found their formal place in the treatment or prevention of CAT. Several meta-analyses have suggested similar efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with cancer compared with those of LMWH.6-8 These meta-analysis studies largely looked at subpopulations and compared the outcomes with those of the landmark CLOT (Randomized Comparison of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer Investigators) and CATCH (Comparison of Acute Treatments in Cancer Hemostasis) trials.9,10

As it is still unclear whether the DOACs are effective and safe for treatment/prevention of CAT, some confusion remains regarding the best management of these at-risk patients. In patients with cancer on DOAC therapy for an approved indication, it is assumed that the therapeutic benefit seen in approved indications would translate to treatment and prevention of CAT. This study aims to determine the incidence of VTE and rates of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (CRNMB) in veterans with cancer who received a DOAC.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center chart review was approved by the local institutional review board and research safety committee. A search within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse identified patients who had an active prescription for one of the DOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban) along with an ICD 9 or ICD 10 code corresponding to a malignancy.

Patients were included in the final analysis if they were aged 18 to 89 years at time of DOAC receipt, undergoing active treatment for malignancy, had evidence of a history of malignancy (either diagnostic or charted evidence of previous treatment), or received cancer-related surgery within 30 days of DOAC prescription with curative intent. Patients were excluded from the final analysis if they did not receive a DOAC prescription or have any clear evidence of malignancy documented in the medical chart.

Patients’ charts were evaluated for the following clinical endpoints: patient age, height (cm), weight (kg), type of malignancy, type of treatment for malignancy, serum creatinine (SCr), creatinine clearance (CrCl) calculated with the Cockcroft-Gault equation using actual body weight, serum hemoglobin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, indication for DOAC, type of VTE, presence of a prior VTE, and diagnostic test performed for VTE. Major bleeding and CRNMB criteria were based on the definitions provided by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH).11 All laboratory values and demographic information were gathered at the time of initial DOAC prescription.

The primary endpoint for this study was incidence of VTE. The secondary endpoints included major bleeding and CRNMB. All data collection and statistical analysis were done using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Redmond, WA). Comparisons of data between trials were done using the chi-squared calculation.

Results

From initial FDA approval of dabigatran (first DOAC on the market) on October 15, 2012, to January 1, 2017, there were 343 patients who met initial inclusion criteria. Of those, 115 did not have any clear evidence of malignancy, 22 did not have any records of DOAC receipt, 15 did not receive a DOAC within the date range, and 23 patients’ charts were unavailable.

The majority of the patients were males (96.6%), with an average age of 74.5 years. The average weight of all patients was 92.5 kg, with an average SCr of 1.1 mg/dL. This equated to an average CrCl of 85.5 mL/min based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation using actual bodyweight. Of the 177 patients evaluated, 30 (16.9%) were receiving active cancer treatment at time of DOAC initiation.

Two (1.1%) patients developed a VTE while receiving a DOAC.

Among the 177 evaluable patients in this study, there were 7 patients (4%) who developed a major bleed and 13 patients (7.3%) who developed a clinically relevant nonmajor bleed according to the definitions provided by ISTH.11

As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients were actively receiving treatment during DOAC administration. Most of the documented cases of malignancy were either a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) or prostate cancer. The most common method of treatment was surgical resection for both malignancies. Of the 30 patients who received active malignancy treatment while on a DOAC, there were 4 patients with multiple myeloma, 6 patients with NMSC, 4 patients with colon cancer, 1 patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), 1 patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), 1 patient with small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL), 4 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 1 patient with unspecified brain cancer, and 1 patient with breast cancer. The various characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 6.

Discussion

The CLOT and CATCH trials were chosen as historic comparators. Although the active treatment interventions and comparator arms were not similar between the patients included in this study and the CLOT and CATCH trials, the authors felt the comparison was appropriate as these trials were designed specifically for patients with malignancy. Additionally, these trials sought to assess rates of VTE formation and bleeding in the patient with malignancies—outcomes that aligned with this study. Alternative trials for comparison are the subgroup analyses of patients with malignancies in the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials.12-14 Although these trials were designed to stratify patients based on presence of malignancy, they were not powered to account for increased risk of VTE in patients with malignancies.

There are multiple risk factors that increase the risk of CAT. Khoranna and colleagues identified primary stomach, pancreas, brain, lung, lymphoma, gynecologic, bladder, testicular, and renal carcinomas as a high risk of VTE formation.15 Additionally, Khoranna and colleagues noted that elderly patients and patients actively receiving treatment are at an increased risk of VTE formation.15 The low rate of VTE formation (1.1%) in the patients in this study may be due to the low risk for VTE formation. As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients (16.9%) in this study were receiving active treatment.

Additionally, there were only 42 patients (23.7%) who had a high-risk malignancy. The increased age of the patient population (74.5 years old) in this study is one risk factor that could largely skew the risks of VTE formation in the patient population. In addition to age, the average body mass index (BMI) of this study’s patient population (30 kg/m2) may further increase risk of VTE. Although Khoranna and colleagues identified a BMI of 35 kg/m2 as the cutoff for increased risk of CAT, the increased risk based on a BMI of 30 kg/m2 cannot be ignored in the patients in this study.15

Another risk inherent in the treatment of patients with cancer is pancytopenia, which may lead to increased risks of bleeding and infection. When patients are exposed to an anticoagulant agent in the setting of decreased platelets and hemoglobin (from treatment or disease process), the risk for major bleeds and CRNMB are increased drastically. In this patient population, the combined rate of bleeding (11.3%) was relatively decreased compared with that of the CLOT (16.5% for all bleeding events) and CATCH (15.7% for all bleeding events) trials.9,10

Compared with the oncology subgroup analysis of the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials, the differences are more noticeable. The AMPLIFY trial reported a 1.1% incidence of bleeding in patients with cancer on apixaban, whereas the RE-COVER trial did not report bleeding rates, and the EINSTEIN trial reported a 14% incidence of bleeding in all patients with cancer on rivaroxaban for VTE treatment.12-14 This study found a bleeding incidence of 12.2% with apixaban, 5.7% with dabigatran, and 14.7% with rivaroxaban. In this trial the incidence of bleeding with rivaroxaban were similar; however, the incidence of bleeding with apixaban was markedly higher. There is no obvious explanation for this, as the dosing of apixaban was appropriate in all patients in this trial except for one. There was no documented bleed in this patient’s medical chart.

A meta-analysis conducted by Vedovati and colleagues identified 6 studies in which patients with cancer received either a DOAC (with or without a heparin product) or vitamin K antagonist.16 That analysis found a nonsignificant reduction in VTE recurrence (odds ratio [OR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31-1.1), major bleeding (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.41-1.44), and CRNMB (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.62-1.18).16 The meta-analysis adds to the growing body of evidence in support of both safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with cancer. Although the Vedovati and colleagues study does not directly compare rates between 2 treatment groups, the findings of similar rates of VTE recurrence, major bleed, and CRNMB are consistent with the current study. Despite differing patient characteristics, the meta-analysis by Vedovati and colleagues supports the ongoing use of DOACs in patients with malignancy, as does the current study.16

Limitations

Although it seems that apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban are effective in reducing the risk of VTE in veterans with malignancy, there are some inherent weaknesses in the current study. Most notably is the choice of comparator trials. The authors’ believe that the CLOT and CATCH trials were the most appropriate based on similarities in population and outcomes. Considering the CLOT and CATCH trials compared LMWH to coumarin products for treatment of VTE, future studies should compare use of these agents with DOACs in the cancer population. In addition, the study did not include outcomes that would adequately assess risks of VTE and bleeding formation. This information would have been beneficial to more effectively categorize this study’s patient population based on risks of each of its predetermined outcomes. Understanding safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients at various risks would help practitioners to choose more appropriate agents in practice. Last, this study did not assess the incidence of stroke in study patients. This is important because the DOACs were used mostly for stroke prevention in AF and atrial flutter. The increased risk of VTE in patients with cancer cannot directly correlate to risk of stroke with a comorbid cardiac condition, but the hypercoagulable state cannot be ignored in these patients.

Conclusion

This study provided some preliminary evidence for the safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with cancer. The low incidence of VTE formation and similar rates of bleeding among other clinical trials indicate that DOACs are safe alternatives to currently recommended anticoagulation medication in patients with cancer.

Patients with cancer are at an increased risk of both venous thromboembolism (VTE) and bleeding complications. Risk factors for development of cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) include indwelling lines, antineoplastic therapies, lack of mobility, and physical/chemical damage from the tumor.1 Venous thromboembolism may manifest as either deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). Cancer-associated thrombosis can lead to significant mortality in patients with cancer and may increase health care costs for additional medications and hospitalizations.

Zullig and colleagues estimated that 46,666 veterans received cancer care from the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) health care system in 2010. This number equates to about 3% of all patients with cancer in the US who receive at least some of their health care from the VA health care system.2 In addition to cancer care, these veterans receive treatment for various comorbid conditions. One such condition that is of concern in a prothrombotic state is atrial fibrillation (AF). For this condition, patients often require anticoagulation therapy with aspirin, warfarin, or one of the recently approved direct oral anticoagulant agents (DOACs), depending on risk factors.

Background

Due to their ease of administration, limited monitoring requirements, and proven safety and efficacy in patients with AF requiring anticoagulation, the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology recently switched their recommendations for rivaroxaban and dabigatran for oral stroke prevention to a class 1/level B recommendation.3

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends treatment with DOACs over warfarin therapy for acute VTE in patients without cancer; however, the ACCP prefers low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) over the DOACs for treatment of CAT.4 Recently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) updated its guidelines for the treatment of cancer-associated thromboembolic disease to recommend 2 of the DOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban) for treatment of acute VTE over warfarin. These guidelines also recommend LMWH over DOACs for treatment of acute VTE in patients with cancer.5 These NCCN recommendations are largely based on prespecified subgroup meta-analyses of the DOACs compared with those of LMWH or warfarin in the cancer population.

In addition to stroke prevention in patients with AF, DOACs have additional FDA-approved indications, including treatment of acute VTE, prevention of recurrent VTE, and postoperative VTE treatment and prophylaxis. Due to a lack of head-to-head, randomized controlled trials comparing LMWH with DOACs in patients with cancer, these agents have not found their formal place in the treatment or prevention of CAT. Several meta-analyses have suggested similar efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with cancer compared with those of LMWH.6-8 These meta-analysis studies largely looked at subpopulations and compared the outcomes with those of the landmark CLOT (Randomized Comparison of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer Investigators) and CATCH (Comparison of Acute Treatments in Cancer Hemostasis) trials.9,10

As it is still unclear whether the DOACs are effective and safe for treatment/prevention of CAT, some confusion remains regarding the best management of these at-risk patients. In patients with cancer on DOAC therapy for an approved indication, it is assumed that the therapeutic benefit seen in approved indications would translate to treatment and prevention of CAT. This study aims to determine the incidence of VTE and rates of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (CRNMB) in veterans with cancer who received a DOAC.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center chart review was approved by the local institutional review board and research safety committee. A search within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse identified patients who had an active prescription for one of the DOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban) along with an ICD 9 or ICD 10 code corresponding to a malignancy.

Patients were included in the final analysis if they were aged 18 to 89 years at time of DOAC receipt, undergoing active treatment for malignancy, had evidence of a history of malignancy (either diagnostic or charted evidence of previous treatment), or received cancer-related surgery within 30 days of DOAC prescription with curative intent. Patients were excluded from the final analysis if they did not receive a DOAC prescription or have any clear evidence of malignancy documented in the medical chart.

Patients’ charts were evaluated for the following clinical endpoints: patient age, height (cm), weight (kg), type of malignancy, type of treatment for malignancy, serum creatinine (SCr), creatinine clearance (CrCl) calculated with the Cockcroft-Gault equation using actual body weight, serum hemoglobin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, indication for DOAC, type of VTE, presence of a prior VTE, and diagnostic test performed for VTE. Major bleeding and CRNMB criteria were based on the definitions provided by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH).11 All laboratory values and demographic information were gathered at the time of initial DOAC prescription.

The primary endpoint for this study was incidence of VTE. The secondary endpoints included major bleeding and CRNMB. All data collection and statistical analysis were done using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Redmond, WA). Comparisons of data between trials were done using the chi-squared calculation.

Results

From initial FDA approval of dabigatran (first DOAC on the market) on October 15, 2012, to January 1, 2017, there were 343 patients who met initial inclusion criteria. Of those, 115 did not have any clear evidence of malignancy, 22 did not have any records of DOAC receipt, 15 did not receive a DOAC within the date range, and 23 patients’ charts were unavailable.

The majority of the patients were males (96.6%), with an average age of 74.5 years. The average weight of all patients was 92.5 kg, with an average SCr of 1.1 mg/dL. This equated to an average CrCl of 85.5 mL/min based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation using actual bodyweight. Of the 177 patients evaluated, 30 (16.9%) were receiving active cancer treatment at time of DOAC initiation.

Two (1.1%) patients developed a VTE while receiving a DOAC.

Among the 177 evaluable patients in this study, there were 7 patients (4%) who developed a major bleed and 13 patients (7.3%) who developed a clinically relevant nonmajor bleed according to the definitions provided by ISTH.11

As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients were actively receiving treatment during DOAC administration. Most of the documented cases of malignancy were either a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) or prostate cancer. The most common method of treatment was surgical resection for both malignancies. Of the 30 patients who received active malignancy treatment while on a DOAC, there were 4 patients with multiple myeloma, 6 patients with NMSC, 4 patients with colon cancer, 1 patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), 1 patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), 1 patient with small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL), 4 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 1 patient with unspecified brain cancer, and 1 patient with breast cancer. The various characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 6.

Discussion

The CLOT and CATCH trials were chosen as historic comparators. Although the active treatment interventions and comparator arms were not similar between the patients included in this study and the CLOT and CATCH trials, the authors felt the comparison was appropriate as these trials were designed specifically for patients with malignancy. Additionally, these trials sought to assess rates of VTE formation and bleeding in the patient with malignancies—outcomes that aligned with this study. Alternative trials for comparison are the subgroup analyses of patients with malignancies in the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials.12-14 Although these trials were designed to stratify patients based on presence of malignancy, they were not powered to account for increased risk of VTE in patients with malignancies.

There are multiple risk factors that increase the risk of CAT. Khoranna and colleagues identified primary stomach, pancreas, brain, lung, lymphoma, gynecologic, bladder, testicular, and renal carcinomas as a high risk of VTE formation.15 Additionally, Khoranna and colleagues noted that elderly patients and patients actively receiving treatment are at an increased risk of VTE formation.15 The low rate of VTE formation (1.1%) in the patients in this study may be due to the low risk for VTE formation. As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients (16.9%) in this study were receiving active treatment.

Additionally, there were only 42 patients (23.7%) who had a high-risk malignancy. The increased age of the patient population (74.5 years old) in this study is one risk factor that could largely skew the risks of VTE formation in the patient population. In addition to age, the average body mass index (BMI) of this study’s patient population (30 kg/m2) may further increase risk of VTE. Although Khoranna and colleagues identified a BMI of 35 kg/m2 as the cutoff for increased risk of CAT, the increased risk based on a BMI of 30 kg/m2 cannot be ignored in the patients in this study.15

Another risk inherent in the treatment of patients with cancer is pancytopenia, which may lead to increased risks of bleeding and infection. When patients are exposed to an anticoagulant agent in the setting of decreased platelets and hemoglobin (from treatment or disease process), the risk for major bleeds and CRNMB are increased drastically. In this patient population, the combined rate of bleeding (11.3%) was relatively decreased compared with that of the CLOT (16.5% for all bleeding events) and CATCH (15.7% for all bleeding events) trials.9,10

Compared with the oncology subgroup analysis of the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials, the differences are more noticeable. The AMPLIFY trial reported a 1.1% incidence of bleeding in patients with cancer on apixaban, whereas the RE-COVER trial did not report bleeding rates, and the EINSTEIN trial reported a 14% incidence of bleeding in all patients with cancer on rivaroxaban for VTE treatment.12-14 This study found a bleeding incidence of 12.2% with apixaban, 5.7% with dabigatran, and 14.7% with rivaroxaban. In this trial the incidence of bleeding with rivaroxaban were similar; however, the incidence of bleeding with apixaban was markedly higher. There is no obvious explanation for this, as the dosing of apixaban was appropriate in all patients in this trial except for one. There was no documented bleed in this patient’s medical chart.

A meta-analysis conducted by Vedovati and colleagues identified 6 studies in which patients with cancer received either a DOAC (with or without a heparin product) or vitamin K antagonist.16 That analysis found a nonsignificant reduction in VTE recurrence (odds ratio [OR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31-1.1), major bleeding (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.41-1.44), and CRNMB (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.62-1.18).16 The meta-analysis adds to the growing body of evidence in support of both safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with cancer. Although the Vedovati and colleagues study does not directly compare rates between 2 treatment groups, the findings of similar rates of VTE recurrence, major bleed, and CRNMB are consistent with the current study. Despite differing patient characteristics, the meta-analysis by Vedovati and colleagues supports the ongoing use of DOACs in patients with malignancy, as does the current study.16

Limitations

Although it seems that apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban are effective in reducing the risk of VTE in veterans with malignancy, there are some inherent weaknesses in the current study. Most notably is the choice of comparator trials. The authors’ believe that the CLOT and CATCH trials were the most appropriate based on similarities in population and outcomes. Considering the CLOT and CATCH trials compared LMWH to coumarin products for treatment of VTE, future studies should compare use of these agents with DOACs in the cancer population. In addition, the study did not include outcomes that would adequately assess risks of VTE and bleeding formation. This information would have been beneficial to more effectively categorize this study’s patient population based on risks of each of its predetermined outcomes. Understanding safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients at various risks would help practitioners to choose more appropriate agents in practice. Last, this study did not assess the incidence of stroke in study patients. This is important because the DOACs were used mostly for stroke prevention in AF and atrial flutter. The increased risk of VTE in patients with cancer cannot directly correlate to risk of stroke with a comorbid cardiac condition, but the hypercoagulable state cannot be ignored in these patients.

Conclusion

This study provided some preliminary evidence for the safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with cancer. The low incidence of VTE formation and similar rates of bleeding among other clinical trials indicate that DOACs are safe alternatives to currently recommended anticoagulation medication in patients with cancer.

1. Motykie GD, Zebala LP, Caprini JA, et al. A guide to venous thromboembolism risk factor assessment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2000;9(3):253-262.

2. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891.

3. January CT, Wann S, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071-2104.

4. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease. Version 1.2018. https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/vte.pdf. Updated March 22, 2018. Accessed April 9, 2018.

6. Brunetti ND, Gesuete E, De Gennaro L, et al. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants compared to vitamin K inhibitors and low molecular weight heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:214-221.

7. Posch F, Konigsbrügge O, Zielinski C, Pabinger I, Ay C. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136(3):582-589.

8. van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middledorp S, Büller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood. 2014;124(12):1968-1975.

9. Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al; Randomized Comparison of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer (CLOT) Investigators. Low molecular weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-153.

10. Lee AY, Kamphuisen PW, Meyer G, et al; CATCH Investigators. Tinzaparin vs warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in patients with active cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(7):677-686.

11. Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation. Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):2119-2126.

12. Agnelli G, Büller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the AMPLIFY trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(12):2187-2191.

13. Schulman S, Goldhaber SZ, Kearon C, et al. Treatment with dabigatran or warfarin in patients with venous thromboembolism and cancer. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(1):150-157.

14. Prins MH, Lensing AW, Brighton TA, et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PF): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2014;1(1):e37-e46.

15. Khoranna AA, Connolly GC. Assessing risk of venous thromboembolism in the patient with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):4839-4847.

16. Vedovati MC, Germini F, Agnelli G, Becattini C. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with VTE and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2015;147(2):475-483.

1. Motykie GD, Zebala LP, Caprini JA, et al. A guide to venous thromboembolism risk factor assessment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2000;9(3):253-262.

2. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891.

3. January CT, Wann S, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071-2104.

4. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease. Version 1.2018. https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/vte.pdf. Updated March 22, 2018. Accessed April 9, 2018.

6. Brunetti ND, Gesuete E, De Gennaro L, et al. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants compared to vitamin K inhibitors and low molecular weight heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;230:214-221.

7. Posch F, Konigsbrügge O, Zielinski C, Pabinger I, Ay C. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136(3):582-589.

8. van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middledorp S, Büller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood. 2014;124(12):1968-1975.

9. Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al; Randomized Comparison of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer (CLOT) Investigators. Low molecular weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-153.

10. Lee AY, Kamphuisen PW, Meyer G, et al; CATCH Investigators. Tinzaparin vs warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in patients with active cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(7):677-686.

11. Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation. Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):2119-2126.

12. Agnelli G, Büller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the AMPLIFY trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(12):2187-2191.

13. Schulman S, Goldhaber SZ, Kearon C, et al. Treatment with dabigatran or warfarin in patients with venous thromboembolism and cancer. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(1):150-157.

14. Prins MH, Lensing AW, Brighton TA, et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PF): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol. 2014;1(1):e37-e46.

15. Khoranna AA, Connolly GC. Assessing risk of venous thromboembolism in the patient with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):4839-4847.

16. Vedovati MC, Germini F, Agnelli G, Becattini C. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with VTE and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2015;147(2):475-483.