User login

Characterizing Hospitalist Practice and Perceptions of Critical Care Delivery

Despite calls for board-certified intensivist physicians to lead critical care delivery,1-3 the intensivist shortage in the United States continues to worsen,4 with projected shortfalls of 22% by 2020 and 35% by 2030.5 Many hospitals currently have inadequate or no board-certified intensivist support.6 The intensivist shortage has necessitated the development of alternative intensive care unit (ICU) staffing models, including engagement in telemedicine,7 the utilization of advanced practice providers,8 and dependence on hospitalists9 to deliver critical care services to ICU patients. Presently, research does not clearly show consistent differences in clinical outcomes based on the training of the clinical provider, although optimized teamwork and team rounds in the ICU do seem to be associated with improved outcomes.10-12

In its 2016 annual survey of hospital medicine (HM) leaders, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) documented that most HM groups care for ICU patients, with up to 80% of hospitalist groups in some regions delivering critical care.13 In many United States hospitals, hospitalists serve as the primary if not lone physician providers of critical care.6,14 HM, with its team-based approach and on-site presence, shares many of the key attributes and values that define high-functioning critical care teams, and many hospitalists likely capably deliver some critical care services.9 However, hospitalists are also a highly heterogeneous work force with varied exposure to and comfort with critical care medicine, making it difficult to generalize hospitalists’ scope of practice in the ICU.

Because hospitalists render a significant amount of critical care in the United States, we surveyed practicing hospitalists to understand their demographics and practice roles in the ICU setting and to ascertain how they are supported when doing so. Additionally, we sought to identify mismatches between the ICU services that hospitalists provide and what they feel prepared and supported to deliver. Finally, we attempted to elucidate how hospitalists who practice in the ICU might respond to novel educational offerings targeted to mitigate cognitive or procedural gaps.

METHODS

We developed and deployed a survey to address the aforementioned questions. The survey content was developed iteratively by the Critical Care Task Force of SHM’s Education Committee and subsequently approved by SHM’s Education Committee and Board of Directors. Members of the Critical Care Task Force include critical care physicians and hospitalists. The survey included 25 items (supplemental Appendix A). Seventeen questions addressed the demographics and practice roles of hospitalists in the ICU, 5 addressed cognitive and procedural practice gaps, and 3 addressed how hospitalists would respond to educational opportunities in critical care. We used conditional formatting to ensure that only respondents who deliver ICU care could answer questions related to ICU practice. The survey was delivered by using an online survey platform (Survey Monkey, San Mateo, CA).

The survey was deployed in 3 phases from March to October of 2016. Initially, we distributed a pilot survey to professional contacts of the Critical Care Task Force to solicit feedback and refine the survey’s format and content. These contacts were largely academic hospitalists from our local institutions. We then distributed the survey to hospitalists via professional networks with instructions to forward the link to interested hospitalists. Finally, we distributed the survey to approximately 4000 hospitalists randomly selected from SHM’s national listserv of approximately 12,000 hospitalists. Respondents could enter a drawing for a monetary prize upon completion of the survey.

None of the survey questions changed during the 3 phases of survey deployment, and the data reported herein were compiled from all 3 phases of the survey deployment. Frequency tables were created using Tableau (version 10.0; Tableau Software, Seattle, WA). Comparisons between categorical questions were made by using χ2 and Fischer exact tests to calculate P values for associations by using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Associations with P values below .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Objective 1: Demographics and Practice Role

Four hundred and twenty-five hospitalists responded to the survey. The first 2 phases (pilot survey and distribution via professional networks) generated 101 responses, and the third phase (via SHM’s listserv) generated an additional 324 responses. As the survey was anonymous, we could not determine which hospitals or geographic regions were represented. Three hundred and twenty-five of the 425 hospitalists who completed the survey (77%) reported that they delivered care in the ICU. Of these 325 hospitalists, 45 served only as consultants, while the remaining 280 (66% of the total sample) served as the primary attending physician in the ICU. Among these primary providers of care in the ICU, 60 (21%) practiced in rural settings and 220 (79%) practiced in nonrural settings (Figure 1).

The demographics of our respondents were similar to those of the SHM annual survey,13 in which 66% of respondents delivered ICU care. Forty-one percent of our respondents worked in critical access or small community hospitals, 24% in academic medical centers, and 34% in large community centers with an academic affiliation. The SHM annual survey cohort included more physicians from nonteaching hospitals (58.7%) and fewer from academic medical centers (14.8%).13

Hospitalists’ presence in the ICU varied by practice setting (Table 1).

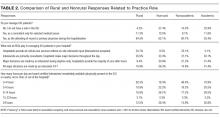

Hospitalists were significantly more prevalent in rural ICUs than in nonrural settings (96% vs 73%; Table 2).

We found similar results when comparing academic hospitalists (those working in an academic medical center or academic-affiliated hospital) with nonacademic hospitalists (those working in critical access or small community centers). Specifically, hospitalists in nonacademic settings were significantly more prevalent in ICUs (90% vs 67%; Table 2), more likely to serve as the primary attending (81% vs 55%), and more likely to deliver all critical care services (64% vs 25%). Sixty-four percent of respondents from nonacademic settings reported that hospitalists manage all or most ICU patients in their hospital as opposed to 25% for academic respondents (χ2P value for association <.001). Intensivist availability was also significantly lower in nonacademic ICUs (Table 2).

We also sought to determine whether the ability to transfer critically ill patients to higher levels of care effectively mitigated shortfalls in intensivist staffing. When restricted to hospitalists who served as primary providers for ICU patients, 28% of all respondents and 51% of rural hospitalists reported transferring patients to a higher level of care.

Sixty-seven percent of hospitalists who served as primary physicians for ICU patients in any setting reported at least moderate difficulty arranging transfers to higher levels of care.

Objective 2: Identifying the Practice Gap

Hospitalists’ perceptions of practicing critical care beyond their skill level and without sufficient board-certified intensivist support varied by both practice location and practice type (Table 3).

There were similar discrepancies between academic and nonacademic respondents. Forty-two percent of respondents practicing in nonacademic settings reported being expected to practice beyond their scope at least some of the time, and 18% reported that intensivist support was never sufficient. This contrasts with academic hospitalists, of whom 35% reported feeling expected to practice outside their scope, and less than 4% reported the available support from intensivists was never sufficient. For comparisons of academic and nonacademic respondents, only perceptions of sufficient board-certified intensivist support reached statistical significance (Table 3).

The role of intensivists in making management decisions and the strategy for ventilator management decisions correlated significantly with perception of intensivist support (P < .001) but not with the perception of practicing beyond one’s scope. The number of ventilated patients did not correlate significantly with either perception of intensivist support or of being expected to practice beyond scope.

Difficulty transferring patients to a higher level of care was the only attribute that significantly correlated with hospitalists’ perceptions of having to practice beyond their skill level (P < .05; Table 3). Difficulty of transfer was also significantly associated with perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001). Total hours of intensivist coverage, intensivist role in decision making, and ventilator management arrangements also correlated significantly with the perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001 for all; Table 3).

Objective 3: Assessing Interest in Critical Care Education

More than 85% of respondents indicated interest in obtaining additional critical care training and some form of certification short of fellowship training. Preferred modes of content delivery included courses or precourses at national meetings, academies, or online modules. Hospitalists in smaller communities indicated preference for online resources.

DISCUSSION

This survey of a large national cohort of hospitalists from diverse practice settings validates previous studies suggesting that hospitalists deliver critical care services, most notably in community and rural hospitals.13 A substantial subset of our respondents represented rural practice settings, which allowed us to compare rural and nonrural hospitalists as well as those practicing in academic and nonacademic settings. In assessing both the objective services that hospitalists provided as well as their subjective perceptions of how they practiced, we could correlate factors associated with the sense of practicing beyond one’s skill or feeling inadequately supported by board-certified intensivists.

More than a third of responding hospitalists who practiced in the ICU reported that they practiced beyond their self-perceived skill level, and almost three-fourths indicated that they practiced without consistent or adequate board-certified intensivist support. Rural and nonacademic hospitalists were far more likely to report delivering critical care beyond their comfort level and having insufficient board-certified intensivist support.

Calls for board-certified intensivists to deliver critical care to all critically ill patients do not reflect the reality in many American hospitals and, either by intent or by default, hospitalists have become the major and often sole providers of critical care services in many hospitals without robust intensivist support. We suspect that this phenomenon has been consistently underreported in the literature because academic hospitalists generally do not practice critical care.15

Many potential solutions to the intensivist shortage have been explored. Prior efforts in the United States have focused largely on care standardization and the recruitment of more trainees into existing critical care training pathways.16 Other countries have created multidisciplinary critical care training pathways that delink critical care from specific subspecialty training programs.17 Another potential solution to ensure that critically ill patients receive care from board-certified intensivists is to regionalize critical care such that the sickest patients are consistently transferred to referral centers with robust intensivist staffing.1,18 While such an approach has been effectively implemented for trauma patients7, it has yet to materialize on a systemic basis for other critically ill cohorts. Moreover, our data suggest that hospitalists who attempt to transfer patients to higher levels of critical care find doing so burdensome and difficult.

Our surveyed hospitalists overwhelmingly expressed interest in augmenting their critical care skills and knowledge. However, most existing critical care educational offerings are not optimized for hospitalists, either focusing on very specific skills or knowledge (eg, procedural techniques or point-of-care ultrasound) or providing entry-level or very foundational education. None of these offerings provide comprehensive, structured training schemas for hospitalists who need to evolve beyond basic critical care skills to manage critically ill patients competently and consistently for extended periods of time.

Our study has several limitations. First, we estimate that about 10% of invited participants responded to this survey, but as respondents could forward the survey via professional networks, this is only an estimate. It is possible but unlikely that some respondents could have completed the survey more than once. Second, because our analysis identified only associations, we cannot infer causality for any of our findings. Third, the questionnaire was not designed to capture the acuity threshold at which point each respondent would prefer to transfer their patients into an ICU setting or to another institution for assistance in critical care management. We recognize that definitions and perceptions of patient acuity vary markedly from one hospital to the next, and a patient who can be comfortably managed in a floor setting in one hospital may require ICU care in a smaller or less well-resourced hospital. Practice patterns relating to acuity thresholds could have a substantial impact both on critical care patient volumes and on provider perceptions and, as such, warrant further study.

Finally, as respondents participated voluntarily, our sample may have overrepresented hospitalists who practice or are interested in critical care, thereby overestimating the scope of the problem and hospitalists’ interest in nonfellowship critical care training and certification. However, this seems unlikely given that, relative to SHM’s annual survey, we overrepresented hospitalists from academic and large community medical centers who generally provide less critical care than other hospitalists.13 Provided that roughly 85% of the estimated 50,000 American hospitalists practice outside of academic medical centers,13 perhaps as many as 37,000 hospitalists regularly deliver care to critically ill patients in ICUs. In light of the evolving intensivist shortage,4,5 this number seems likely to continue to grow. Whatever biases may exist in our sample, it is evident that a substantial number of ICU patients are managed by hospitalists who feel unprepared and undersupported to perform the task.

Without a massive and sustained increase in the number of board-certified intensivists or a systemic national plan to regionalize critical care delivery, hospitalists will continue to practice critical care, frequently with inadequate knowledge, skills, or intensivist support. Fortunately, these same hospitalists appear to be highly interested in augmenting their skills to care for their critically ill patients. The HM and critical care communities must rise to this challenge and help these providers deliver safe, appropriate, and high-quality care to their critically ill patients.

Disclosure

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, receives funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and Society of Hospital Medicine honoraria.

Society of Hospital Medicine Resources

1. Barnato AE, Kahn JM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Prioritizing the organization and management of intensive care services in the United States: the PrOMIS Conference. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1003-1011. PubMed

2. The Leapfrog Group. Factsheet: ICU Physician Staffing. Leapfrog Hospital Survey. Washington, DC: The Leapfrog Group; 2016.

3. Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, Raoof S, Marciniuk DD, Gutterman DD. First, do no harm: less training not equal quality care. Am J Crit Care. Jul 2012;21(4):227-230. PubMed

4. Krell K. Critical care workforce. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1350-1353. PubMed

5. Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, White A, Popovich J, Jr. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284(21):2762-2770. PubMed

6. Hyzy RC, Flanders SA, Pronovost PJ, et al. Characteristics of intensive care units in Michigan: not an open and closed case. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):4-9. PubMed

7. Kahn JM, Cicero BD, Wallace DJ, Iwashyna TJ. Adoption of ICU telemedicine in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):362-368. PubMed

8. Kleinpell RM, Ely EW, Grabenkort R. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2888-2897. PubMed

9. Heisler M. Hospitalists and intensivists: partners in caring for the critically ill--the time has come. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):1-3. PubMed

10. Checkley W, Martin GS, Brown SM, et al. Structure, process, and annual ICU mortality across 69 centers: United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group Critical Illness Outcomes Study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):344-356. PubMed

11. Wise KR, Akopov VA, Williams BR, Jr., Ido MS, Leeper KV, Jr., Dressler DD. Hospitalists and intensivists in the medical ICU: a prospective observational study comparing mortality and length of stay between two staffing models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):183-189. PubMed

12. Yoo EJ, Edwards JD, Dean ML, Dudley RA. Multidisciplinary Critical Care and Intensivist Staffing: Results of a Statewide Survey and Association With Mortality. J Intensive Care Med. 2016;31(5):325-332. PubMed

13. Society of Hospital Medicine. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2016.

14. Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1952-1956. PubMed

15. Weled BJ, Adzhigirey LA, Hodgman TM, et al. Critical Care Delivery: The Importance of Process of Care and ICU Structure to Improved Outcomes: An Update From the American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force on Models of Critical Care. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(7):1520-1525. PubMed

16. Kelley MA, Angus D, Chalfin DB, et al. The critical care crisis in the United States: a report from the profession. Chest. 2004;125(4):1514-1517. PubMed

17. Bion JF, Ramsay G, Roussos C, Burchardi H. Intensive care training and specialty status in Europe: international comparisons. Task Force on Educational issues of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(4);372-377. PubMed

18. Kahn JM, Branas CC, Schwab CW, Asch DA. Regionalization of medical critical care: what can we learn from the trauma experience? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(11):3085-3088. PubMed

Despite calls for board-certified intensivist physicians to lead critical care delivery,1-3 the intensivist shortage in the United States continues to worsen,4 with projected shortfalls of 22% by 2020 and 35% by 2030.5 Many hospitals currently have inadequate or no board-certified intensivist support.6 The intensivist shortage has necessitated the development of alternative intensive care unit (ICU) staffing models, including engagement in telemedicine,7 the utilization of advanced practice providers,8 and dependence on hospitalists9 to deliver critical care services to ICU patients. Presently, research does not clearly show consistent differences in clinical outcomes based on the training of the clinical provider, although optimized teamwork and team rounds in the ICU do seem to be associated with improved outcomes.10-12

In its 2016 annual survey of hospital medicine (HM) leaders, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) documented that most HM groups care for ICU patients, with up to 80% of hospitalist groups in some regions delivering critical care.13 In many United States hospitals, hospitalists serve as the primary if not lone physician providers of critical care.6,14 HM, with its team-based approach and on-site presence, shares many of the key attributes and values that define high-functioning critical care teams, and many hospitalists likely capably deliver some critical care services.9 However, hospitalists are also a highly heterogeneous work force with varied exposure to and comfort with critical care medicine, making it difficult to generalize hospitalists’ scope of practice in the ICU.

Because hospitalists render a significant amount of critical care in the United States, we surveyed practicing hospitalists to understand their demographics and practice roles in the ICU setting and to ascertain how they are supported when doing so. Additionally, we sought to identify mismatches between the ICU services that hospitalists provide and what they feel prepared and supported to deliver. Finally, we attempted to elucidate how hospitalists who practice in the ICU might respond to novel educational offerings targeted to mitigate cognitive or procedural gaps.

METHODS

We developed and deployed a survey to address the aforementioned questions. The survey content was developed iteratively by the Critical Care Task Force of SHM’s Education Committee and subsequently approved by SHM’s Education Committee and Board of Directors. Members of the Critical Care Task Force include critical care physicians and hospitalists. The survey included 25 items (supplemental Appendix A). Seventeen questions addressed the demographics and practice roles of hospitalists in the ICU, 5 addressed cognitive and procedural practice gaps, and 3 addressed how hospitalists would respond to educational opportunities in critical care. We used conditional formatting to ensure that only respondents who deliver ICU care could answer questions related to ICU practice. The survey was delivered by using an online survey platform (Survey Monkey, San Mateo, CA).

The survey was deployed in 3 phases from March to October of 2016. Initially, we distributed a pilot survey to professional contacts of the Critical Care Task Force to solicit feedback and refine the survey’s format and content. These contacts were largely academic hospitalists from our local institutions. We then distributed the survey to hospitalists via professional networks with instructions to forward the link to interested hospitalists. Finally, we distributed the survey to approximately 4000 hospitalists randomly selected from SHM’s national listserv of approximately 12,000 hospitalists. Respondents could enter a drawing for a monetary prize upon completion of the survey.

None of the survey questions changed during the 3 phases of survey deployment, and the data reported herein were compiled from all 3 phases of the survey deployment. Frequency tables were created using Tableau (version 10.0; Tableau Software, Seattle, WA). Comparisons between categorical questions were made by using χ2 and Fischer exact tests to calculate P values for associations by using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Associations with P values below .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Objective 1: Demographics and Practice Role

Four hundred and twenty-five hospitalists responded to the survey. The first 2 phases (pilot survey and distribution via professional networks) generated 101 responses, and the third phase (via SHM’s listserv) generated an additional 324 responses. As the survey was anonymous, we could not determine which hospitals or geographic regions were represented. Three hundred and twenty-five of the 425 hospitalists who completed the survey (77%) reported that they delivered care in the ICU. Of these 325 hospitalists, 45 served only as consultants, while the remaining 280 (66% of the total sample) served as the primary attending physician in the ICU. Among these primary providers of care in the ICU, 60 (21%) practiced in rural settings and 220 (79%) practiced in nonrural settings (Figure 1).

The demographics of our respondents were similar to those of the SHM annual survey,13 in which 66% of respondents delivered ICU care. Forty-one percent of our respondents worked in critical access or small community hospitals, 24% in academic medical centers, and 34% in large community centers with an academic affiliation. The SHM annual survey cohort included more physicians from nonteaching hospitals (58.7%) and fewer from academic medical centers (14.8%).13

Hospitalists’ presence in the ICU varied by practice setting (Table 1).

Hospitalists were significantly more prevalent in rural ICUs than in nonrural settings (96% vs 73%; Table 2).

We found similar results when comparing academic hospitalists (those working in an academic medical center or academic-affiliated hospital) with nonacademic hospitalists (those working in critical access or small community centers). Specifically, hospitalists in nonacademic settings were significantly more prevalent in ICUs (90% vs 67%; Table 2), more likely to serve as the primary attending (81% vs 55%), and more likely to deliver all critical care services (64% vs 25%). Sixty-four percent of respondents from nonacademic settings reported that hospitalists manage all or most ICU patients in their hospital as opposed to 25% for academic respondents (χ2P value for association <.001). Intensivist availability was also significantly lower in nonacademic ICUs (Table 2).

We also sought to determine whether the ability to transfer critically ill patients to higher levels of care effectively mitigated shortfalls in intensivist staffing. When restricted to hospitalists who served as primary providers for ICU patients, 28% of all respondents and 51% of rural hospitalists reported transferring patients to a higher level of care.

Sixty-seven percent of hospitalists who served as primary physicians for ICU patients in any setting reported at least moderate difficulty arranging transfers to higher levels of care.

Objective 2: Identifying the Practice Gap

Hospitalists’ perceptions of practicing critical care beyond their skill level and without sufficient board-certified intensivist support varied by both practice location and practice type (Table 3).

There were similar discrepancies between academic and nonacademic respondents. Forty-two percent of respondents practicing in nonacademic settings reported being expected to practice beyond their scope at least some of the time, and 18% reported that intensivist support was never sufficient. This contrasts with academic hospitalists, of whom 35% reported feeling expected to practice outside their scope, and less than 4% reported the available support from intensivists was never sufficient. For comparisons of academic and nonacademic respondents, only perceptions of sufficient board-certified intensivist support reached statistical significance (Table 3).

The role of intensivists in making management decisions and the strategy for ventilator management decisions correlated significantly with perception of intensivist support (P < .001) but not with the perception of practicing beyond one’s scope. The number of ventilated patients did not correlate significantly with either perception of intensivist support or of being expected to practice beyond scope.

Difficulty transferring patients to a higher level of care was the only attribute that significantly correlated with hospitalists’ perceptions of having to practice beyond their skill level (P < .05; Table 3). Difficulty of transfer was also significantly associated with perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001). Total hours of intensivist coverage, intensivist role in decision making, and ventilator management arrangements also correlated significantly with the perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001 for all; Table 3).

Objective 3: Assessing Interest in Critical Care Education

More than 85% of respondents indicated interest in obtaining additional critical care training and some form of certification short of fellowship training. Preferred modes of content delivery included courses or precourses at national meetings, academies, or online modules. Hospitalists in smaller communities indicated preference for online resources.

DISCUSSION

This survey of a large national cohort of hospitalists from diverse practice settings validates previous studies suggesting that hospitalists deliver critical care services, most notably in community and rural hospitals.13 A substantial subset of our respondents represented rural practice settings, which allowed us to compare rural and nonrural hospitalists as well as those practicing in academic and nonacademic settings. In assessing both the objective services that hospitalists provided as well as their subjective perceptions of how they practiced, we could correlate factors associated with the sense of practicing beyond one’s skill or feeling inadequately supported by board-certified intensivists.

More than a third of responding hospitalists who practiced in the ICU reported that they practiced beyond their self-perceived skill level, and almost three-fourths indicated that they practiced without consistent or adequate board-certified intensivist support. Rural and nonacademic hospitalists were far more likely to report delivering critical care beyond their comfort level and having insufficient board-certified intensivist support.

Calls for board-certified intensivists to deliver critical care to all critically ill patients do not reflect the reality in many American hospitals and, either by intent or by default, hospitalists have become the major and often sole providers of critical care services in many hospitals without robust intensivist support. We suspect that this phenomenon has been consistently underreported in the literature because academic hospitalists generally do not practice critical care.15

Many potential solutions to the intensivist shortage have been explored. Prior efforts in the United States have focused largely on care standardization and the recruitment of more trainees into existing critical care training pathways.16 Other countries have created multidisciplinary critical care training pathways that delink critical care from specific subspecialty training programs.17 Another potential solution to ensure that critically ill patients receive care from board-certified intensivists is to regionalize critical care such that the sickest patients are consistently transferred to referral centers with robust intensivist staffing.1,18 While such an approach has been effectively implemented for trauma patients7, it has yet to materialize on a systemic basis for other critically ill cohorts. Moreover, our data suggest that hospitalists who attempt to transfer patients to higher levels of critical care find doing so burdensome and difficult.

Our surveyed hospitalists overwhelmingly expressed interest in augmenting their critical care skills and knowledge. However, most existing critical care educational offerings are not optimized for hospitalists, either focusing on very specific skills or knowledge (eg, procedural techniques or point-of-care ultrasound) or providing entry-level or very foundational education. None of these offerings provide comprehensive, structured training schemas for hospitalists who need to evolve beyond basic critical care skills to manage critically ill patients competently and consistently for extended periods of time.

Our study has several limitations. First, we estimate that about 10% of invited participants responded to this survey, but as respondents could forward the survey via professional networks, this is only an estimate. It is possible but unlikely that some respondents could have completed the survey more than once. Second, because our analysis identified only associations, we cannot infer causality for any of our findings. Third, the questionnaire was not designed to capture the acuity threshold at which point each respondent would prefer to transfer their patients into an ICU setting or to another institution for assistance in critical care management. We recognize that definitions and perceptions of patient acuity vary markedly from one hospital to the next, and a patient who can be comfortably managed in a floor setting in one hospital may require ICU care in a smaller or less well-resourced hospital. Practice patterns relating to acuity thresholds could have a substantial impact both on critical care patient volumes and on provider perceptions and, as such, warrant further study.

Finally, as respondents participated voluntarily, our sample may have overrepresented hospitalists who practice or are interested in critical care, thereby overestimating the scope of the problem and hospitalists’ interest in nonfellowship critical care training and certification. However, this seems unlikely given that, relative to SHM’s annual survey, we overrepresented hospitalists from academic and large community medical centers who generally provide less critical care than other hospitalists.13 Provided that roughly 85% of the estimated 50,000 American hospitalists practice outside of academic medical centers,13 perhaps as many as 37,000 hospitalists regularly deliver care to critically ill patients in ICUs. In light of the evolving intensivist shortage,4,5 this number seems likely to continue to grow. Whatever biases may exist in our sample, it is evident that a substantial number of ICU patients are managed by hospitalists who feel unprepared and undersupported to perform the task.

Without a massive and sustained increase in the number of board-certified intensivists or a systemic national plan to regionalize critical care delivery, hospitalists will continue to practice critical care, frequently with inadequate knowledge, skills, or intensivist support. Fortunately, these same hospitalists appear to be highly interested in augmenting their skills to care for their critically ill patients. The HM and critical care communities must rise to this challenge and help these providers deliver safe, appropriate, and high-quality care to their critically ill patients.

Disclosure

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, receives funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and Society of Hospital Medicine honoraria.

Society of Hospital Medicine Resources

Despite calls for board-certified intensivist physicians to lead critical care delivery,1-3 the intensivist shortage in the United States continues to worsen,4 with projected shortfalls of 22% by 2020 and 35% by 2030.5 Many hospitals currently have inadequate or no board-certified intensivist support.6 The intensivist shortage has necessitated the development of alternative intensive care unit (ICU) staffing models, including engagement in telemedicine,7 the utilization of advanced practice providers,8 and dependence on hospitalists9 to deliver critical care services to ICU patients. Presently, research does not clearly show consistent differences in clinical outcomes based on the training of the clinical provider, although optimized teamwork and team rounds in the ICU do seem to be associated with improved outcomes.10-12

In its 2016 annual survey of hospital medicine (HM) leaders, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) documented that most HM groups care for ICU patients, with up to 80% of hospitalist groups in some regions delivering critical care.13 In many United States hospitals, hospitalists serve as the primary if not lone physician providers of critical care.6,14 HM, with its team-based approach and on-site presence, shares many of the key attributes and values that define high-functioning critical care teams, and many hospitalists likely capably deliver some critical care services.9 However, hospitalists are also a highly heterogeneous work force with varied exposure to and comfort with critical care medicine, making it difficult to generalize hospitalists’ scope of practice in the ICU.

Because hospitalists render a significant amount of critical care in the United States, we surveyed practicing hospitalists to understand their demographics and practice roles in the ICU setting and to ascertain how they are supported when doing so. Additionally, we sought to identify mismatches between the ICU services that hospitalists provide and what they feel prepared and supported to deliver. Finally, we attempted to elucidate how hospitalists who practice in the ICU might respond to novel educational offerings targeted to mitigate cognitive or procedural gaps.

METHODS

We developed and deployed a survey to address the aforementioned questions. The survey content was developed iteratively by the Critical Care Task Force of SHM’s Education Committee and subsequently approved by SHM’s Education Committee and Board of Directors. Members of the Critical Care Task Force include critical care physicians and hospitalists. The survey included 25 items (supplemental Appendix A). Seventeen questions addressed the demographics and practice roles of hospitalists in the ICU, 5 addressed cognitive and procedural practice gaps, and 3 addressed how hospitalists would respond to educational opportunities in critical care. We used conditional formatting to ensure that only respondents who deliver ICU care could answer questions related to ICU practice. The survey was delivered by using an online survey platform (Survey Monkey, San Mateo, CA).

The survey was deployed in 3 phases from March to October of 2016. Initially, we distributed a pilot survey to professional contacts of the Critical Care Task Force to solicit feedback and refine the survey’s format and content. These contacts were largely academic hospitalists from our local institutions. We then distributed the survey to hospitalists via professional networks with instructions to forward the link to interested hospitalists. Finally, we distributed the survey to approximately 4000 hospitalists randomly selected from SHM’s national listserv of approximately 12,000 hospitalists. Respondents could enter a drawing for a monetary prize upon completion of the survey.

None of the survey questions changed during the 3 phases of survey deployment, and the data reported herein were compiled from all 3 phases of the survey deployment. Frequency tables were created using Tableau (version 10.0; Tableau Software, Seattle, WA). Comparisons between categorical questions were made by using χ2 and Fischer exact tests to calculate P values for associations by using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Associations with P values below .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Objective 1: Demographics and Practice Role

Four hundred and twenty-five hospitalists responded to the survey. The first 2 phases (pilot survey and distribution via professional networks) generated 101 responses, and the third phase (via SHM’s listserv) generated an additional 324 responses. As the survey was anonymous, we could not determine which hospitals or geographic regions were represented. Three hundred and twenty-five of the 425 hospitalists who completed the survey (77%) reported that they delivered care in the ICU. Of these 325 hospitalists, 45 served only as consultants, while the remaining 280 (66% of the total sample) served as the primary attending physician in the ICU. Among these primary providers of care in the ICU, 60 (21%) practiced in rural settings and 220 (79%) practiced in nonrural settings (Figure 1).

The demographics of our respondents were similar to those of the SHM annual survey,13 in which 66% of respondents delivered ICU care. Forty-one percent of our respondents worked in critical access or small community hospitals, 24% in academic medical centers, and 34% in large community centers with an academic affiliation. The SHM annual survey cohort included more physicians from nonteaching hospitals (58.7%) and fewer from academic medical centers (14.8%).13

Hospitalists’ presence in the ICU varied by practice setting (Table 1).

Hospitalists were significantly more prevalent in rural ICUs than in nonrural settings (96% vs 73%; Table 2).

We found similar results when comparing academic hospitalists (those working in an academic medical center or academic-affiliated hospital) with nonacademic hospitalists (those working in critical access or small community centers). Specifically, hospitalists in nonacademic settings were significantly more prevalent in ICUs (90% vs 67%; Table 2), more likely to serve as the primary attending (81% vs 55%), and more likely to deliver all critical care services (64% vs 25%). Sixty-four percent of respondents from nonacademic settings reported that hospitalists manage all or most ICU patients in their hospital as opposed to 25% for academic respondents (χ2P value for association <.001). Intensivist availability was also significantly lower in nonacademic ICUs (Table 2).

We also sought to determine whether the ability to transfer critically ill patients to higher levels of care effectively mitigated shortfalls in intensivist staffing. When restricted to hospitalists who served as primary providers for ICU patients, 28% of all respondents and 51% of rural hospitalists reported transferring patients to a higher level of care.

Sixty-seven percent of hospitalists who served as primary physicians for ICU patients in any setting reported at least moderate difficulty arranging transfers to higher levels of care.

Objective 2: Identifying the Practice Gap

Hospitalists’ perceptions of practicing critical care beyond their skill level and without sufficient board-certified intensivist support varied by both practice location and practice type (Table 3).

There were similar discrepancies between academic and nonacademic respondents. Forty-two percent of respondents practicing in nonacademic settings reported being expected to practice beyond their scope at least some of the time, and 18% reported that intensivist support was never sufficient. This contrasts with academic hospitalists, of whom 35% reported feeling expected to practice outside their scope, and less than 4% reported the available support from intensivists was never sufficient. For comparisons of academic and nonacademic respondents, only perceptions of sufficient board-certified intensivist support reached statistical significance (Table 3).

The role of intensivists in making management decisions and the strategy for ventilator management decisions correlated significantly with perception of intensivist support (P < .001) but not with the perception of practicing beyond one’s scope. The number of ventilated patients did not correlate significantly with either perception of intensivist support or of being expected to practice beyond scope.

Difficulty transferring patients to a higher level of care was the only attribute that significantly correlated with hospitalists’ perceptions of having to practice beyond their skill level (P < .05; Table 3). Difficulty of transfer was also significantly associated with perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001). Total hours of intensivist coverage, intensivist role in decision making, and ventilator management arrangements also correlated significantly with the perceived adequacy of board-certified intensivist support (P < .001 for all; Table 3).

Objective 3: Assessing Interest in Critical Care Education

More than 85% of respondents indicated interest in obtaining additional critical care training and some form of certification short of fellowship training. Preferred modes of content delivery included courses or precourses at national meetings, academies, or online modules. Hospitalists in smaller communities indicated preference for online resources.

DISCUSSION

This survey of a large national cohort of hospitalists from diverse practice settings validates previous studies suggesting that hospitalists deliver critical care services, most notably in community and rural hospitals.13 A substantial subset of our respondents represented rural practice settings, which allowed us to compare rural and nonrural hospitalists as well as those practicing in academic and nonacademic settings. In assessing both the objective services that hospitalists provided as well as their subjective perceptions of how they practiced, we could correlate factors associated with the sense of practicing beyond one’s skill or feeling inadequately supported by board-certified intensivists.

More than a third of responding hospitalists who practiced in the ICU reported that they practiced beyond their self-perceived skill level, and almost three-fourths indicated that they practiced without consistent or adequate board-certified intensivist support. Rural and nonacademic hospitalists were far more likely to report delivering critical care beyond their comfort level and having insufficient board-certified intensivist support.

Calls for board-certified intensivists to deliver critical care to all critically ill patients do not reflect the reality in many American hospitals and, either by intent or by default, hospitalists have become the major and often sole providers of critical care services in many hospitals without robust intensivist support. We suspect that this phenomenon has been consistently underreported in the literature because academic hospitalists generally do not practice critical care.15

Many potential solutions to the intensivist shortage have been explored. Prior efforts in the United States have focused largely on care standardization and the recruitment of more trainees into existing critical care training pathways.16 Other countries have created multidisciplinary critical care training pathways that delink critical care from specific subspecialty training programs.17 Another potential solution to ensure that critically ill patients receive care from board-certified intensivists is to regionalize critical care such that the sickest patients are consistently transferred to referral centers with robust intensivist staffing.1,18 While such an approach has been effectively implemented for trauma patients7, it has yet to materialize on a systemic basis for other critically ill cohorts. Moreover, our data suggest that hospitalists who attempt to transfer patients to higher levels of critical care find doing so burdensome and difficult.

Our surveyed hospitalists overwhelmingly expressed interest in augmenting their critical care skills and knowledge. However, most existing critical care educational offerings are not optimized for hospitalists, either focusing on very specific skills or knowledge (eg, procedural techniques or point-of-care ultrasound) or providing entry-level or very foundational education. None of these offerings provide comprehensive, structured training schemas for hospitalists who need to evolve beyond basic critical care skills to manage critically ill patients competently and consistently for extended periods of time.

Our study has several limitations. First, we estimate that about 10% of invited participants responded to this survey, but as respondents could forward the survey via professional networks, this is only an estimate. It is possible but unlikely that some respondents could have completed the survey more than once. Second, because our analysis identified only associations, we cannot infer causality for any of our findings. Third, the questionnaire was not designed to capture the acuity threshold at which point each respondent would prefer to transfer their patients into an ICU setting or to another institution for assistance in critical care management. We recognize that definitions and perceptions of patient acuity vary markedly from one hospital to the next, and a patient who can be comfortably managed in a floor setting in one hospital may require ICU care in a smaller or less well-resourced hospital. Practice patterns relating to acuity thresholds could have a substantial impact both on critical care patient volumes and on provider perceptions and, as such, warrant further study.

Finally, as respondents participated voluntarily, our sample may have overrepresented hospitalists who practice or are interested in critical care, thereby overestimating the scope of the problem and hospitalists’ interest in nonfellowship critical care training and certification. However, this seems unlikely given that, relative to SHM’s annual survey, we overrepresented hospitalists from academic and large community medical centers who generally provide less critical care than other hospitalists.13 Provided that roughly 85% of the estimated 50,000 American hospitalists practice outside of academic medical centers,13 perhaps as many as 37,000 hospitalists regularly deliver care to critically ill patients in ICUs. In light of the evolving intensivist shortage,4,5 this number seems likely to continue to grow. Whatever biases may exist in our sample, it is evident that a substantial number of ICU patients are managed by hospitalists who feel unprepared and undersupported to perform the task.

Without a massive and sustained increase in the number of board-certified intensivists or a systemic national plan to regionalize critical care delivery, hospitalists will continue to practice critical care, frequently with inadequate knowledge, skills, or intensivist support. Fortunately, these same hospitalists appear to be highly interested in augmenting their skills to care for their critically ill patients. The HM and critical care communities must rise to this challenge and help these providers deliver safe, appropriate, and high-quality care to their critically ill patients.

Disclosure

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, receives funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and Society of Hospital Medicine honoraria.

Society of Hospital Medicine Resources

1. Barnato AE, Kahn JM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Prioritizing the organization and management of intensive care services in the United States: the PrOMIS Conference. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1003-1011. PubMed

2. The Leapfrog Group. Factsheet: ICU Physician Staffing. Leapfrog Hospital Survey. Washington, DC: The Leapfrog Group; 2016.

3. Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, Raoof S, Marciniuk DD, Gutterman DD. First, do no harm: less training not equal quality care. Am J Crit Care. Jul 2012;21(4):227-230. PubMed

4. Krell K. Critical care workforce. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1350-1353. PubMed

5. Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, White A, Popovich J, Jr. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284(21):2762-2770. PubMed

6. Hyzy RC, Flanders SA, Pronovost PJ, et al. Characteristics of intensive care units in Michigan: not an open and closed case. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):4-9. PubMed

7. Kahn JM, Cicero BD, Wallace DJ, Iwashyna TJ. Adoption of ICU telemedicine in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):362-368. PubMed

8. Kleinpell RM, Ely EW, Grabenkort R. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2888-2897. PubMed

9. Heisler M. Hospitalists and intensivists: partners in caring for the critically ill--the time has come. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):1-3. PubMed

10. Checkley W, Martin GS, Brown SM, et al. Structure, process, and annual ICU mortality across 69 centers: United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group Critical Illness Outcomes Study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):344-356. PubMed

11. Wise KR, Akopov VA, Williams BR, Jr., Ido MS, Leeper KV, Jr., Dressler DD. Hospitalists and intensivists in the medical ICU: a prospective observational study comparing mortality and length of stay between two staffing models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):183-189. PubMed

12. Yoo EJ, Edwards JD, Dean ML, Dudley RA. Multidisciplinary Critical Care and Intensivist Staffing: Results of a Statewide Survey and Association With Mortality. J Intensive Care Med. 2016;31(5):325-332. PubMed

13. Society of Hospital Medicine. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2016.

14. Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1952-1956. PubMed

15. Weled BJ, Adzhigirey LA, Hodgman TM, et al. Critical Care Delivery: The Importance of Process of Care and ICU Structure to Improved Outcomes: An Update From the American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force on Models of Critical Care. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(7):1520-1525. PubMed

16. Kelley MA, Angus D, Chalfin DB, et al. The critical care crisis in the United States: a report from the profession. Chest. 2004;125(4):1514-1517. PubMed

17. Bion JF, Ramsay G, Roussos C, Burchardi H. Intensive care training and specialty status in Europe: international comparisons. Task Force on Educational issues of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(4);372-377. PubMed

18. Kahn JM, Branas CC, Schwab CW, Asch DA. Regionalization of medical critical care: what can we learn from the trauma experience? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(11):3085-3088. PubMed

1. Barnato AE, Kahn JM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Prioritizing the organization and management of intensive care services in the United States: the PrOMIS Conference. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1003-1011. PubMed

2. The Leapfrog Group. Factsheet: ICU Physician Staffing. Leapfrog Hospital Survey. Washington, DC: The Leapfrog Group; 2016.

3. Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, Raoof S, Marciniuk DD, Gutterman DD. First, do no harm: less training not equal quality care. Am J Crit Care. Jul 2012;21(4):227-230. PubMed

4. Krell K. Critical care workforce. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1350-1353. PubMed

5. Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, White A, Popovich J, Jr. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284(21):2762-2770. PubMed

6. Hyzy RC, Flanders SA, Pronovost PJ, et al. Characteristics of intensive care units in Michigan: not an open and closed case. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):4-9. PubMed

7. Kahn JM, Cicero BD, Wallace DJ, Iwashyna TJ. Adoption of ICU telemedicine in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):362-368. PubMed

8. Kleinpell RM, Ely EW, Grabenkort R. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2888-2897. PubMed

9. Heisler M. Hospitalists and intensivists: partners in caring for the critically ill--the time has come. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):1-3. PubMed

10. Checkley W, Martin GS, Brown SM, et al. Structure, process, and annual ICU mortality across 69 centers: United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group Critical Illness Outcomes Study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):344-356. PubMed

11. Wise KR, Akopov VA, Williams BR, Jr., Ido MS, Leeper KV, Jr., Dressler DD. Hospitalists and intensivists in the medical ICU: a prospective observational study comparing mortality and length of stay between two staffing models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):183-189. PubMed

12. Yoo EJ, Edwards JD, Dean ML, Dudley RA. Multidisciplinary Critical Care and Intensivist Staffing: Results of a Statewide Survey and Association With Mortality. J Intensive Care Med. 2016;31(5):325-332. PubMed

13. Society of Hospital Medicine. 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2016.

14. Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1952-1956. PubMed

15. Weled BJ, Adzhigirey LA, Hodgman TM, et al. Critical Care Delivery: The Importance of Process of Care and ICU Structure to Improved Outcomes: An Update From the American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force on Models of Critical Care. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(7):1520-1525. PubMed

16. Kelley MA, Angus D, Chalfin DB, et al. The critical care crisis in the United States: a report from the profession. Chest. 2004;125(4):1514-1517. PubMed

17. Bion JF, Ramsay G, Roussos C, Burchardi H. Intensive care training and specialty status in Europe: international comparisons. Task Force on Educational issues of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(4);372-377. PubMed

18. Kahn JM, Branas CC, Schwab CW, Asch DA. Regionalization of medical critical care: what can we learn from the trauma experience? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(11):3085-3088. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Progress on Reducing Readmissions

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP)[1] contained within the Affordable Care Act focused national and local attention on hospital resources and efforts to reduce hospital readmissions. Driven by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' (CMS) desire to pay for value instead of volume, the response of hospitals and health systems appears to be yielding change across the United States.[2] A number of recent publications in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) exemplify the keen interest in reducing readmissions, while providing guidance regarding interventions and where we might target future research. Evidence from an exemplary systematic review of the pediatric literature confirms some experience in adults regarding effective interventionsall studies were multifacetedand highlights the importance of identifying a single healthcare provider or centrally coordinated hub to assume responsibility for extended care transition and follow‐up.[3] Notably, studies of pediatric patients and their families document the effectiveness of enhanced inpatient education and engagement while in the hospital.[3] Unfortunately, a study among adults at a top‐ranked academic institution indicates poor communication among nurses and physicians regarding patient discharge education.[4] Efforts to improve nursephysician communication by redesigning the hospitalist model of care delivery at a Veterans Affairs (VA) institution appeared to enhance perceptions of communication among the care team members and reduced length of stay, but disappointingly there was no reduction in readmission rates.[5] Studies such as this are essential in identifying which specific interventions may actually change outcomes such as readmission rates.

In 1984, a diminutive elderly woman provocatively squawked Where's the beef?, launching a highly successful advertising campaign for Wendy's hamburger chain.[6] This catchphrase may aptly describe Bradley and colleague's survey study of the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalization (STAAR) and Hospital‐to‐Home (H2H) campaigns.[7] Auerbach and colleagues eloquently stated in a 2007 New England Journal of Medicine perspective[8] how they had witnessed recent initiatives that emphasize dissemination of innovative but unproven strategies, an approach that runs counter to the principle of following the evidence[9] in selecting interventions that meet quality and safety goals.[10] I firmly agree with this assessment, and 6 years later believe we should be more thoughtful about potentially repeating implementation of unproven strategies.

Do we know if the interventions recommended by H2H and STAAR are what hospital care teams should be attempting? Even the authors mention that definitive evidence on their effectiveness is lacking. The H2H and STAAR programs certainly encourage some theoretically laudable activitiesmedication reconciliation by nurses, alerting outpatient physicians within 48 hours of patient discharge, and providing skilled nursing facilities the direct contact number of the inpatient treating physician for patients transferred. However, do these efforts actually improve patient outcomes? Before embarking on state or national campaigns to improve care, we should consider carefully what are the best evidence‐based interventions. Remarkably, some prior evidence indicates that direct communication between the hospital‐based physician and primary care provider (PCP) may not actually impact patient outcomes.[11] Newer research published in JHM confirms my belief that the PCP needs to be engaged by hospitalists during a hospitalization. Lindquist's research group at Northwestern nicely demonstrated how communication between a patient's PCP and the admitting hospitalist, complemented by contact between the PCP and patient within 24 hours postdischarge, reduced the probability of a medication discrepancy by 70%.[12] Although no evaluation of the effect on readmissions was reported, this study may provide information on causality related to the importance of PCP involvement in the care of hospitalized patients.

Numerous publications now document research on successfully implemented programs that lowered hospital readmissions, and are cited by CMS as evidence‐based interventions.[13] Projects Re‐Engineered Discharge (RED)[14] and Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions[15] target the hospital discharge process, and both appear to lower hospital readmission rates. The Care Transitions Intervention (CTI),[16] Transitional Care Model (TCM),[17] and the Guided Care model[18] all leverage nurse practitioners or nurses to protect elderly patients during what can be a perilous care transition from hospital to home. CTI and TCM have been further validated in effectiveness studies.[19, 20] Two recent systematic reviews provide further insight into the complexity of efforts to reduce 30‐day rehospitalizations, but unfortunately do not reveal a desired silver bullet. The first focused exclusively on interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization, and concluded that no single intervention was successful alone, but identified interventions bridging the hospital‐to‐home transition (eg, CTI), and a bundle of interventions such as Project RED as showing efficacy.[21] The second review more broadly sought to evaluate the effectiveness of hospital‐initiated strategies to prevent postdischarge adverse events (AEs) such as readmissions and emergency department visits,[22] stating Because of scant evidence, no conclusions could be reached on methods to prevent postdischarge AEs. The researchers' sobering conclusion stated that strategies to improve patient safety at hospital discharge remain unclear.

With rising federal penalties for higher‐than‐expected readmission rates, many hospital leaders eagerly join collaboratives aiming to reduce hospital readmissions. H2H appears to be among the largest, reporting >600 hospital participants, and STAAR has been active since 2009, with a recently published qualitative study identifying gaps in evidence for effective interventions, and deficits in quality improvement capabilities among some organizations as implementation challenges.[23] Notably, the survey by Bradley and colleagues documented that just half of the hospitals had a quality improvement (QI) team focused on reducing readmissions. Although laudable in their goals, H2H and STAAR may represent expensive commitments of staff and time to efforts that may not improve outcomes. Importantly, recently published research evaluating QI studies showed concerning results among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted at 6 Glasgow hospitals evaluated supported self‐management (home visits by nurses and thorough education) by patients with moderate to severe COPD, but documented no changes in hospitalization or mortality.[24]Another RCT at 20 sites evaluated a comprehensive care management program to prevent hospitalizations among 960 VA patients with COPD.[25] It had to be stopped early due to elevated all‐cause mortality in the intervention group, and there was no difference in hospitalization rates.

Moving forward, QI efforts to reduce hospital readmissions should utilize proven interventions unless they are part of a rigorous trial. The emerging field of implementation science (the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence‐based practices into routine practice, and hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services[26]) needs to be applied to additional research in this area.[27] Another consideration would be for CMS and funders such as the Commonwealth Foundation or The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to encourage and fund merging of current initiatives to move away from competition and provide clarity to community hospitals. Regardless, such collaboration should still undertake formal evaluation to discern best approaches to implementation. I applaud the authors for recognizing that Input from hospitalists who are often critical links among inpatient and outpatient care and between patients and their families is strongly needed to ensure hospitals focus on what strategies are most effective for successful transitions from hospital to home. Yet, I wonder why neither of the large STAAR and H2H initiatives actively partnered with hospitalists and their specialty society (Society of Hospital Medicine) directly in the leadership of these initiatives? On the other hand, why not ask medical societies engaged in delivery of primary care (eg, American Academy for Family Practice, American College of Physicians, or Society of General Internal Medicine), especially to elderly patients (American Geriatric Society), to contribute directly? Involvement on an advisory board is likely not sufficient. Prior efforts document the willingness of these organizations to collaborate and achieve consensus on principles for transitions of care.[28] As powerfully articulated 6 years ago, [W]e must pursue the solutions to quality and safety problems in a way that does not blind us to harms, squander scarce resources, or delude us about the effectiveness of our efforts.[8]

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Dr. Williams is principal investigator for Project BOOST (

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare‐Fee‐for‐service‐Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions‐Reduction‐Program.html. Accessed December 30, 2013.

- , , , , , . Medicare readmission rates showed meaningful decline in 2012. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(2):E1–E12.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review [published online ahead of print December 20, 2013]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2134.

- , , . Communicating discharge instructions to patients: a survey of nurse, intern, and hospitalist practices. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:36–41.

- , , , et al. An academic hospitalist model to improve healthcare work communication and learner education: results from a quasi‐experimental study at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:702–710.

- Wikipedia website. Where's the beef? Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Where's_the_beef%3F. Accessed November 4, 2013.

- , , , , , . Quality collaboratives and campaigns to reduce readmissions: what strategies are hospitals using? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):601–608.

- , , . The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608–613.

- , , , . Accidental deaths, saved lives, and improved quality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(13):1405–1409.

- , , . Clinical Improvement Action Guide. Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 1998.

- , , , et al. Association of communication between hospital‐based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24(3):381–386.

- , , , , . Primary care physician communication a hospital discharge reduces medication discrepancies. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:672–677.

- Centers for Medicare 150(3):178–187.

- , , , et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421–427.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , , et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow‐up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620.

- , , , et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster‐randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):460–466.

- , , , et al. Effectiveness and cost of a transitional care program for heart failure: a prospective study with concurrent controls. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1238–1243.

- , , , , , . The care transitions intervention: translating from efficacy to effectiveness. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1232–1237.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , , , . Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):433–440.

- , , , , , . Turning readmission reduction policies into results: some lessons from a multistate initiative to reduce readmissions. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(4):255–260.

- , , , et al. Glasgow supported self‐management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;344:e1060.

- , , , et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Int Med. 2012;156(10):673–683.

- , . Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1:1.

- , . Moving comparative effectiveness research into practice: implementation science and the role of academic medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(10):1901–1905.

- , , , et al.; American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Transitions of care consensus policy statement American College of Physicians‐Society of General Internal Medicine‐Society of Hospital Medicine‐American Geriatrics Society‐American College of Emergency Physicians‐Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24(8):971–976.

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP)[1] contained within the Affordable Care Act focused national and local attention on hospital resources and efforts to reduce hospital readmissions. Driven by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' (CMS) desire to pay for value instead of volume, the response of hospitals and health systems appears to be yielding change across the United States.[2] A number of recent publications in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) exemplify the keen interest in reducing readmissions, while providing guidance regarding interventions and where we might target future research. Evidence from an exemplary systematic review of the pediatric literature confirms some experience in adults regarding effective interventionsall studies were multifacetedand highlights the importance of identifying a single healthcare provider or centrally coordinated hub to assume responsibility for extended care transition and follow‐up.[3] Notably, studies of pediatric patients and their families document the effectiveness of enhanced inpatient education and engagement while in the hospital.[3] Unfortunately, a study among adults at a top‐ranked academic institution indicates poor communication among nurses and physicians regarding patient discharge education.[4] Efforts to improve nursephysician communication by redesigning the hospitalist model of care delivery at a Veterans Affairs (VA) institution appeared to enhance perceptions of communication among the care team members and reduced length of stay, but disappointingly there was no reduction in readmission rates.[5] Studies such as this are essential in identifying which specific interventions may actually change outcomes such as readmission rates.

In 1984, a diminutive elderly woman provocatively squawked Where's the beef?, launching a highly successful advertising campaign for Wendy's hamburger chain.[6] This catchphrase may aptly describe Bradley and colleague's survey study of the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalization (STAAR) and Hospital‐to‐Home (H2H) campaigns.[7] Auerbach and colleagues eloquently stated in a 2007 New England Journal of Medicine perspective[8] how they had witnessed recent initiatives that emphasize dissemination of innovative but unproven strategies, an approach that runs counter to the principle of following the evidence[9] in selecting interventions that meet quality and safety goals.[10] I firmly agree with this assessment, and 6 years later believe we should be more thoughtful about potentially repeating implementation of unproven strategies.

Do we know if the interventions recommended by H2H and STAAR are what hospital care teams should be attempting? Even the authors mention that definitive evidence on their effectiveness is lacking. The H2H and STAAR programs certainly encourage some theoretically laudable activitiesmedication reconciliation by nurses, alerting outpatient physicians within 48 hours of patient discharge, and providing skilled nursing facilities the direct contact number of the inpatient treating physician for patients transferred. However, do these efforts actually improve patient outcomes? Before embarking on state or national campaigns to improve care, we should consider carefully what are the best evidence‐based interventions. Remarkably, some prior evidence indicates that direct communication between the hospital‐based physician and primary care provider (PCP) may not actually impact patient outcomes.[11] Newer research published in JHM confirms my belief that the PCP needs to be engaged by hospitalists during a hospitalization. Lindquist's research group at Northwestern nicely demonstrated how communication between a patient's PCP and the admitting hospitalist, complemented by contact between the PCP and patient within 24 hours postdischarge, reduced the probability of a medication discrepancy by 70%.[12] Although no evaluation of the effect on readmissions was reported, this study may provide information on causality related to the importance of PCP involvement in the care of hospitalized patients.

Numerous publications now document research on successfully implemented programs that lowered hospital readmissions, and are cited by CMS as evidence‐based interventions.[13] Projects Re‐Engineered Discharge (RED)[14] and Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions[15] target the hospital discharge process, and both appear to lower hospital readmission rates. The Care Transitions Intervention (CTI),[16] Transitional Care Model (TCM),[17] and the Guided Care model[18] all leverage nurse practitioners or nurses to protect elderly patients during what can be a perilous care transition from hospital to home. CTI and TCM have been further validated in effectiveness studies.[19, 20] Two recent systematic reviews provide further insight into the complexity of efforts to reduce 30‐day rehospitalizations, but unfortunately do not reveal a desired silver bullet. The first focused exclusively on interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization, and concluded that no single intervention was successful alone, but identified interventions bridging the hospital‐to‐home transition (eg, CTI), and a bundle of interventions such as Project RED as showing efficacy.[21] The second review more broadly sought to evaluate the effectiveness of hospital‐initiated strategies to prevent postdischarge adverse events (AEs) such as readmissions and emergency department visits,[22] stating Because of scant evidence, no conclusions could be reached on methods to prevent postdischarge AEs. The researchers' sobering conclusion stated that strategies to improve patient safety at hospital discharge remain unclear.

With rising federal penalties for higher‐than‐expected readmission rates, many hospital leaders eagerly join collaboratives aiming to reduce hospital readmissions. H2H appears to be among the largest, reporting >600 hospital participants, and STAAR has been active since 2009, with a recently published qualitative study identifying gaps in evidence for effective interventions, and deficits in quality improvement capabilities among some organizations as implementation challenges.[23] Notably, the survey by Bradley and colleagues documented that just half of the hospitals had a quality improvement (QI) team focused on reducing readmissions. Although laudable in their goals, H2H and STAAR may represent expensive commitments of staff and time to efforts that may not improve outcomes. Importantly, recently published research evaluating QI studies showed concerning results among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted at 6 Glasgow hospitals evaluated supported self‐management (home visits by nurses and thorough education) by patients with moderate to severe COPD, but documented no changes in hospitalization or mortality.[24]Another RCT at 20 sites evaluated a comprehensive care management program to prevent hospitalizations among 960 VA patients with COPD.[25] It had to be stopped early due to elevated all‐cause mortality in the intervention group, and there was no difference in hospitalization rates.