User login

Geriatrics update 2018: Challenges in mental health, mobility, and postdischarge care

Unfortunately, recent research has not unveiled a breakthrough for preventing or treating cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease. But several studies from the last 2 years are helping to drive the field of geriatrics forward, providing evidence of what does and does not help a variety of issues specific to the elderly.

Based on a search of the 2017 and 2018 literature, this article presents new evidence on preventing and treating cognitive impairment, managing dementia-associated behavioral disturbances and delirium, preventing falls, and improving inpatient mobility and posthospital care transitions.

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT, DEMENTIA: STILL NO SILVER BULLET

With the exception of oral anticoagulation treatment for atrial fibrillation, there is little evidence that pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic interventions slow the onset or progression of Alzheimer disease.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

Home occupational therapy. A 2-year home-based occupational therapy intervention1 showed no evidence of slowing functional decline in patients with Alzheimer disease. The randomized controlled trial involving 180 participants consisted of monthly sessions of an intensive, well-established collaborative-care management model that included fall prevention and other safety strategies, personalized training in activities of daily living, exercise, and education. Outcome measures for activities of daily living did not differ significantly between the treatment and control groups.1

Physical activity. Whether physical activity interventions slow cognitive decline and prevent dementia in cognitively intact adults was examined in a systematic review of 32 trials.2 Most of the trials followed patients for 6 months; a few stretched for 1 or 2 years.

Evidence was insufficient to prove cognitive benefit for short-term, single-component or multicomponent physical activity interventions. However, a multidomain physical activity intervention that also included dietary modifications and cognitive training did show a delay in cognitive decline, but only “low-strength” evidence.2

Nutritional supplements. The antioxidants vitamin E and selenium were studied for their possible cognitive benefit in the double-blind randomized Prevention of Alzheimer Disease by Vitamin E and Selenium trial3 in 3,786 asymptomatic men ages 60 and older. Neither supplement was found to prevent dementia over a 7-year follow-up period.

A review of 38 trials4 evaluated the effects on cognition of omega-3 fatty acids, soy, ginkgo biloba, B vitamins, vitamin D plus calcium, vitamin C, beta-carotene, and multi-ingredient supplements. It found insufficient evidence to recommend any over-the-counter supplement for cognitive protection in adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment.

Pharmacologic treatments

Testosterone supplementation. The Testosterone Trials tested the effects of testosterone gel vs placebo for 1 year on 493 men over age 65 with low testosterone (< 275 ng/mL) and with subjective memory complaints and objective memory performance deficits. Treatment was not associated with improved memory or other cognitive functions compared with placebo.5

Antiamyloid drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in nearly 2,000 patients evaluated verubecestat, an oral beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme-1 inhibitor that reduces the amyloid-beta level in cerebrospinal fluid.6

Verubecestat did not reduce cognitive or functional decline in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease, while adverse events including rashes, falls, injuries, sleep disturbances, suicidal ideation, weight loss, and hair color change were more common in the treatment groups. The trial was terminated early because of futility at 50 months.

And in a placebo-controlled trial of solanezumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the amyloid beta peptide, no benefit was demonstrated at 80 weeks in more than 2,000 patients with Alzheimer disease.7

Multiple common agents. A well-conducted systematic review8 of 51 trials of at least a 6-month duration did not support the use of antihypertensive agents, diabetes medications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, hormones, or lipid-lowering drugs for cognitive protection for people with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment.

However, some studies found reassuring evidence that standard therapies for other conditions do not worsen cognitive decline and are protective for atrial fibrillation.8

Proton-pump inhibitors. Concern exists for a potential link between dementia risk and proton-pump inhibitors, which are widely used to treat acid-related gastrointestinal disorders.9

A prospective population-based cohort study10 of nearly 3,500 people ages 65 and older without baseline dementia screened participants for dementia every 2 years over a mean period of 7.5 years and provided further evaluation for those who screened positive. Use of proton-pump inhibitors was not found to be associated with dementia risk, even with high cumulative exposure.

Results from this study do not support avoiding proton-pump inhibitors out of concern for dementia risk, although long-term use is associated with other safety concerns.

Oral anticoagulation. The increased risk of dementia with atrial fibrillation is well documented.11

A retrospective study12 based on a Swedish health registry and using more than 444,000 patients covering more than 1.5 million years at risk found that oral anticoagulant treatment at baseline conferred a 29% lower risk of dementia in an intention-to-treat analysis and a 48% lower risk in on-treatment analysis compared with no oral anticoagulation therapy. No difference was found between new oral anticoagulants and warfarin.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is not associated with cognitive decline

For patients with severe aortic stenosis who are not surgical candidates, transcatheter aortic valve implantation is superior to standard medical therapy,13 but there are concerns of neurologic and cognitive changes after the procedure.14 A meta-analysis of 18 studies assessing cognitive performance in more than 1,000 patients (average age ≥ 80) after undergoing the procedure for severe aortic stenosis found no significant cognitive performance changes from baseline perioperatively or 3 or 6 months later.15

TREATING DEMENTIA-ASSOCIATED BEHAVIORAL DISTURBANCES

Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms often accompany dementia, but no drugs have yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to address them in this population. Nonpharmacologic interventions are recommended as first-line therapy.

Antipsychotics are not recommended

Antipsychotics are often prescribed,16 although they are associated with metabolic syndrome17 and increased risks of stroke and death.18 The FDA has issued black box warnings against using antipsychotics for behavioral management in patients with dementia. Further, the American Geriatrics Society and the American Psychiatric Association do not endorse using them as initial therapy for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.16,19

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services partnered with nursing homes to improve the quality of care for patients with dementia, with results measured as the rate of prescribing antipsychotic medications. Although the use of psychotropic medications declined after initiating the partnership, the use of mood stabilizers increased, possibly as a substitute for antipsychotics.20

Dextromethorphan-quinidine use is up, despite modest evidence of benefit

A consumer news report in 2017 stated that the use of dextromethorphan-quinidine in long-term care facilities increased by nearly 400% between 2012 and 2016.21

Evidence for its benefits comes from a 10-week, phase 2, randomized controlled trial conducted at 42 US study sites with 194 patients with probable Alzheimer disease. Compared with the placebo group, the active treatment group had mildly reduced agitation but an increased risk of falls, dizziness, and diarrhea. However, rates of adverse effects were low, and the authors concluded that treatment was generally well tolerated.22

Pimavanserin: No long-term benefit for psychosis

In a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 181 patients with possible or probable Alzheimer disease and psychotic symptoms, pimavanserin was associated with improved symptoms as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home Version psychosis score at 6 weeks, but no difference was found compared with placebo at 12 weeks. The treatment group had more adverse events, including agitation, aggression, peripheral edema, anxiety, and symptoms of dementia, although the differences were not statistically significant.23

DELIRIUM: AVOID ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Delirium is common in hospitalized older adults, especially those who have baseline cognitive or functional impairment and are exposed to precipitating factors such as treatment with anticholinergic or narcotic medications, infection, surgery, or admission to an intensive care unit.24

Delirium at discharge predicts poor outcomes

In a prospective study of 152 hospitalized patients with delirium, those who either did not recover from delirium or had only partially recovered at discharge were more likely to visit the emergency department, be rehospitalized, or die during the subsequent 3 months than those who had fully recovered from delirium at discharge.25

Multicomponent, patient-centered approach can help

A randomized trial in 377 patients in Taiwan evaluated the use of a modified Hospital Elder Life Program, consisting of 3 protocols focused on orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization. Patients were at least 65 years old and undergoing elective abdominal surgery with expected length of hospital stay longer than 6 days. The program, administered daily during hospitalization, significantly lowered postoperative delirium by 56% and hospital stay by 2 days compared with usual care.26

Prophylactic haloperidol does not improve outcomes

In a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, van den Boogaard et al studied prophylactic intravenous haloperidol in nearly 1,800 critically ill patients at high risk of delirium.27 Haloperidol did not improve survival at 28 days compared with placebo. For secondary outcomes, including delirium incidence, delirium-free and coma-free days, duration of mechanical ventilation, and hospital and intensive care department length of stay, treatment was not found to differ statistically from placebo.

Antipsychotics may worsen delirium

A double-blind, parallel-arm, dose-titrated randomized trial, conducted at 11 Australian hospices or hospitals with palliative care services, administered oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo to 247 patients with life-limiting illness and delirium. Both treatment groups had higher delirium symptom scores than the placebo group.28

In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies found no benefit of antipsychotic medications for preventing or treating delirium in hospitalized adults.29

Antipsychotics are often continued indefinitely

A retrospective chart review at a US academic health system found30 that among 487 patients with a new antipsychotic medication prescribed during hospitalization, 147 (30.2%) were discharged on an antipsychotic. Of these, 121 (82.3%) had a diagnosis of delirium. Only 15 (12.4%) had discharge summaries that included instructions for discontinuing the drug.

Another US health system retrospectively reviewed antipsychotic use and found31 that out of 260 patients who were newly exposed to an antipsychotic drug during hospitalization, 146 (56.2%) were discharged on an antipsychotic drug, and 65% of these patients were still on the drug at the time of the next hospital admission.

EXERCISE, EXERCISE, EXERCISE

Exercise recommended, but not vitamin D, to prevent falls

In 2018, the US Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendations for preventing falls in community-dwelling older adults.32 Based on the findings of several trials, the task force recommends exercise interventions for adults age 65 and older who are at increased risk for falls. Gait, balance, and functional training were studied in 17 trials, resistance training in 13, flexibility in 8, endurance training in 5, and tai chi in 3, with 5 studies including general physical activity. Exercise interventions most commonly took place for 3 sessions per week for 12 months (range 2–42 months).

The task force also recommends against vitamin D supplementation for fall prevention in community-dwelling adults age 65 or older who are not known to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency.

Early mobilization helps inpatients

Hospitalized older adults usually spend most of their time in bed. Forty-five previously ambulatory patients (age ≥ 65 without dementia or delirium) in a Veterans Affairs hospital were monitored with wireless accelerometers and were found to spend, on average, 83% of the measured hospital stay in bed. Standing or walking time ranged from 0.2% to 21%, with a median of only 3% (43 minutes a day).33

Since falls with injury became a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services nonreimbursable hospital-acquired condition, tension has arisen between promoting mobility and preventing falls.34 Two studies evaluating the adoption of mobility-restricting approaches such as bed-alarms, “fall-alert” signs, supervision of patients in the bathroom, and ensuring patients’ walking aids are within reach, did not find a significant reduction in falls or fall-related injuries.35,36

A clinically significant loss of community mobility is common after hospitalization in older adults.37 Older adults who developed mobility impairment during hospitalization had a higher risk of death in a large, retrospective study.38 A large Canadian multisite intervention trial39 that promoted early mobilization in older patients who were admitted to general medical wards resulted in increased mobilization and significantly shorter hospital stays.

POSTHOSPITAL CARE NEEDS IMPROVEMENT

After hospitalization, older adults who have difficulty with activities of daily living or complex medical needs often require continued care.

About 20% of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the United States are discharged to skilled nursing facilities.40 This is often a stressful transition, and most people have little guidance on selecting a facility and simply choose one based on its proximity to home.41

A program of frequent visits by hospital-employed physicians and advanced practice professionals at skilled nursing facilities resulted in a significantly lower 30-day readmission rate compared with nonparticipating skilled nursing facilities in the same geographic area.42

Home healthcare is recommended after hospital discharge at a rapidly increasing rate. Overall referral rates increased from 8.6% to 14.1% between 2001 and 2012, and from 14.3% to 24.0% for patients with heart failure.43 A qualitative study of home healthcare nurses found a need for improved care coordination between home healthcare agencies and discharging hospitals, including defining accountability for orders and enhancing communication.44

- Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Schmid AA, et al. Targeting functional decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(3):164–171. doi:10.7326/M16-0830

- Brasure M, Desai P, Davila H, et al. Physical activity interventions in preventing cognitive decline and Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):30–38. doi:10.7326/M17-1528

- Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Caban-Holt A, et al. Association of antioxidant supplement use and dementia in the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease by Vitamin E and Selenium Trial (PREADViSE). JAMA Neurol 2017; 74(5):567–573. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5778

- Butler M, Nelson VA, Davila H, et al. Over-the-counter supplement interventions to prevent cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):52–62. doi:10.7326/M17-1530

- Resnick SM, Matsumoto AM, Stephens-Shields AJ, et al. Testosterone treatment and cognitive function in older men with low testosterone and age-associated memory impairment. JAMA 2017; 317(7):717–727. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.21044

- Egan MF, Kost J, Tariot PN, et al. Randomized trial of verubecestat for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(18):1691–1703. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1706441

- Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, et al. Trial of solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(4):321–330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1705971

- Fink HA, Jutkowitz E, McCarten JR, et al. Pharmacologic interventions to prevent cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):39–51. doi:10.7326/M17-1529

- Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73(4):410–416. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791

- Gray SL, Walker RL, Dublin S, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and dementia risk: prospective population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(2):247–253. doi:10.1111/jgs.15073

- de Bruijn RF, Heeringa J, Wolters FJ, et al. Association between atrial fibrillation and dementia in the general population. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72(11):1288–1294. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2161

- Friberg L, Rosenqvist M. Less dementia with oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(6):453–460. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx579

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(17):1597–1607. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008232

- Haussig S, Mangner N, Dwyer MG, et al. Effect of a cerebral protection device on brain lesions following transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the CLEAN-TAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 316(6):592–601. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10302

- Khan MM, Herrmann N, Gallagher D, et al. Cognitive outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(2):254–262. doi:10.1111/jgs.15123

- Choosing Wisely; ABIM Foundation. American Geriatrics Society: ten things physicians and patients should question. www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Lieberman JA 3rd. Metabolic changes associated with antipsychotic use. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 6(suppl 2):8–13. pmid:16001095

- Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005; 294(15):1934–1943. doi:10.1001/jama.294.15.1934

- Choosing Wisely; ABIM Foundation. American Psychiatric Association: five things physicians and patients should question. www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-psychiatric-association. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Kales HC. Association of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to improve dementia care with the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropics in long-term care in the United States from 2009 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(5):640–647. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0379

- CNN. The little red pill being pushed on the elderly. www.cnn.com/2017/10/12/health/nuedexta-nursing-homes-invs/index.html. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Cummings JL, Lyketsos CG, Peskind ER, et al. Effect of dextromethorphan-quinidine on agitation in patients with Alzheimer disease dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314(12):1242–1254. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10214

- Ballard C, Banister C, Khan Z, et al; ADP Investigators. Evaluation of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with Alzheimer’s disease psychosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17(3):213–222. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30039-5

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(11):1157–1165. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052321

- Cole MG, McCusker J, Bailey R, et al. Partial and no recovery from delirium after hospital discharge predict increased adverse events. Age Ageing 2017; 46(1):90–95. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw153

- Chen CC, Li HC, Liang JT, et al. Effect of a modified hospital elder life program on delirium and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2017; 152(9):827–834. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1083

- van den Boogaard M, Slooter AJC, Brüggemann RJM, et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018; 319(7):680–690. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0160

- Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(1):34–42. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7491

- Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye SK, Needham DM. Antipsychotic medication for prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64(4):705–714. doi:10.1111/jgs.14076

- Johnson KG, Fashoyin A, Madden-Fuentes R, Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP, Yanamadala M. Discharge plans for geriatric inpatients with delirium: a plan to stop antipsychotics? J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(10):2278–2281. doi:10.1111/jgs.15026

- Loh KP, Ramdass S, Garb JL, et al. Long-term outcomes of elders discharged on antipsychotics. J Hosp Med 2016; 11(8):550–555. doi:10.1002/jhm.2585

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement. JAMA 2018; 319(16):1696–1704. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3097

- Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(9):1660–1665. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

- Growdon ME, Shorr RI, Inouye SK. The tension between promoting mobility and preventing falls in the hospital. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(6):759–760. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0840

- Barker AL, Morello RT, Wolfe R, et al. 6-PACK programme to decrease fall injuries in acute hospitals: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2016; 352:h6781. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6781

- Shorr RI, Chandler AM, Mion LC, et al. Effects of an intervention to increase bed alarm use to prevent falls in hospitalized patients: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(10):692–699. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00005

- Loyd C, Beasley TM, Miltner RS, Clark D, King B, Brown CJ. Trajectories of community mobility recovery after hospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(7):1399–1403. doi:10.1111/jgs.15397

- Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden Activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med 2017; 12(6):396–401. doi:10.12788/jhm.2748

- Liu B, Moore JE, Almaawiy U, et al; MOVE ON Collaboration. Outcomes of mobilisation of vulnerable elders in Ontario (MOVE ON): a multisite interrupted time series evaluation of an implementation intervention to increase patient mobilisation. Age Ageing 2018; 47(1):112–119. doi:10.1093/ageing/afx128

- Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission 2016. www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/march-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Mor V. Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: individual and family perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(11):2459–2465. doi:10.1111/jgs.14988

- Kim LD, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg MB. Impact of a connected care model on 30-day readmission rates from skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med 2017; 12(4):238–244. doi:10.12788/jhm.2710

- Jones CD, Ginde AA, Burke RE, Wald HL, Masoudi FA, Boxer RS. Increasing home healthcare referrals upon discharge from U.S. hospitals: 2001-2012. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(6):1265–1266. doi:10.1111/jgs.13467

- Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the dots”: a qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients. J Gen Intern Med 2017; 32(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4104-0

Unfortunately, recent research has not unveiled a breakthrough for preventing or treating cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease. But several studies from the last 2 years are helping to drive the field of geriatrics forward, providing evidence of what does and does not help a variety of issues specific to the elderly.

Based on a search of the 2017 and 2018 literature, this article presents new evidence on preventing and treating cognitive impairment, managing dementia-associated behavioral disturbances and delirium, preventing falls, and improving inpatient mobility and posthospital care transitions.

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT, DEMENTIA: STILL NO SILVER BULLET

With the exception of oral anticoagulation treatment for atrial fibrillation, there is little evidence that pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic interventions slow the onset or progression of Alzheimer disease.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

Home occupational therapy. A 2-year home-based occupational therapy intervention1 showed no evidence of slowing functional decline in patients with Alzheimer disease. The randomized controlled trial involving 180 participants consisted of monthly sessions of an intensive, well-established collaborative-care management model that included fall prevention and other safety strategies, personalized training in activities of daily living, exercise, and education. Outcome measures for activities of daily living did not differ significantly between the treatment and control groups.1

Physical activity. Whether physical activity interventions slow cognitive decline and prevent dementia in cognitively intact adults was examined in a systematic review of 32 trials.2 Most of the trials followed patients for 6 months; a few stretched for 1 or 2 years.

Evidence was insufficient to prove cognitive benefit for short-term, single-component or multicomponent physical activity interventions. However, a multidomain physical activity intervention that also included dietary modifications and cognitive training did show a delay in cognitive decline, but only “low-strength” evidence.2

Nutritional supplements. The antioxidants vitamin E and selenium were studied for their possible cognitive benefit in the double-blind randomized Prevention of Alzheimer Disease by Vitamin E and Selenium trial3 in 3,786 asymptomatic men ages 60 and older. Neither supplement was found to prevent dementia over a 7-year follow-up period.

A review of 38 trials4 evaluated the effects on cognition of omega-3 fatty acids, soy, ginkgo biloba, B vitamins, vitamin D plus calcium, vitamin C, beta-carotene, and multi-ingredient supplements. It found insufficient evidence to recommend any over-the-counter supplement for cognitive protection in adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment.

Pharmacologic treatments

Testosterone supplementation. The Testosterone Trials tested the effects of testosterone gel vs placebo for 1 year on 493 men over age 65 with low testosterone (< 275 ng/mL) and with subjective memory complaints and objective memory performance deficits. Treatment was not associated with improved memory or other cognitive functions compared with placebo.5

Antiamyloid drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in nearly 2,000 patients evaluated verubecestat, an oral beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme-1 inhibitor that reduces the amyloid-beta level in cerebrospinal fluid.6

Verubecestat did not reduce cognitive or functional decline in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease, while adverse events including rashes, falls, injuries, sleep disturbances, suicidal ideation, weight loss, and hair color change were more common in the treatment groups. The trial was terminated early because of futility at 50 months.

And in a placebo-controlled trial of solanezumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the amyloid beta peptide, no benefit was demonstrated at 80 weeks in more than 2,000 patients with Alzheimer disease.7

Multiple common agents. A well-conducted systematic review8 of 51 trials of at least a 6-month duration did not support the use of antihypertensive agents, diabetes medications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, hormones, or lipid-lowering drugs for cognitive protection for people with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment.

However, some studies found reassuring evidence that standard therapies for other conditions do not worsen cognitive decline and are protective for atrial fibrillation.8

Proton-pump inhibitors. Concern exists for a potential link between dementia risk and proton-pump inhibitors, which are widely used to treat acid-related gastrointestinal disorders.9

A prospective population-based cohort study10 of nearly 3,500 people ages 65 and older without baseline dementia screened participants for dementia every 2 years over a mean period of 7.5 years and provided further evaluation for those who screened positive. Use of proton-pump inhibitors was not found to be associated with dementia risk, even with high cumulative exposure.

Results from this study do not support avoiding proton-pump inhibitors out of concern for dementia risk, although long-term use is associated with other safety concerns.

Oral anticoagulation. The increased risk of dementia with atrial fibrillation is well documented.11

A retrospective study12 based on a Swedish health registry and using more than 444,000 patients covering more than 1.5 million years at risk found that oral anticoagulant treatment at baseline conferred a 29% lower risk of dementia in an intention-to-treat analysis and a 48% lower risk in on-treatment analysis compared with no oral anticoagulation therapy. No difference was found between new oral anticoagulants and warfarin.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is not associated with cognitive decline

For patients with severe aortic stenosis who are not surgical candidates, transcatheter aortic valve implantation is superior to standard medical therapy,13 but there are concerns of neurologic and cognitive changes after the procedure.14 A meta-analysis of 18 studies assessing cognitive performance in more than 1,000 patients (average age ≥ 80) after undergoing the procedure for severe aortic stenosis found no significant cognitive performance changes from baseline perioperatively or 3 or 6 months later.15

TREATING DEMENTIA-ASSOCIATED BEHAVIORAL DISTURBANCES

Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms often accompany dementia, but no drugs have yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to address them in this population. Nonpharmacologic interventions are recommended as first-line therapy.

Antipsychotics are not recommended

Antipsychotics are often prescribed,16 although they are associated with metabolic syndrome17 and increased risks of stroke and death.18 The FDA has issued black box warnings against using antipsychotics for behavioral management in patients with dementia. Further, the American Geriatrics Society and the American Psychiatric Association do not endorse using them as initial therapy for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.16,19

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services partnered with nursing homes to improve the quality of care for patients with dementia, with results measured as the rate of prescribing antipsychotic medications. Although the use of psychotropic medications declined after initiating the partnership, the use of mood stabilizers increased, possibly as a substitute for antipsychotics.20

Dextromethorphan-quinidine use is up, despite modest evidence of benefit

A consumer news report in 2017 stated that the use of dextromethorphan-quinidine in long-term care facilities increased by nearly 400% between 2012 and 2016.21

Evidence for its benefits comes from a 10-week, phase 2, randomized controlled trial conducted at 42 US study sites with 194 patients with probable Alzheimer disease. Compared with the placebo group, the active treatment group had mildly reduced agitation but an increased risk of falls, dizziness, and diarrhea. However, rates of adverse effects were low, and the authors concluded that treatment was generally well tolerated.22

Pimavanserin: No long-term benefit for psychosis

In a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 181 patients with possible or probable Alzheimer disease and psychotic symptoms, pimavanserin was associated with improved symptoms as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home Version psychosis score at 6 weeks, but no difference was found compared with placebo at 12 weeks. The treatment group had more adverse events, including agitation, aggression, peripheral edema, anxiety, and symptoms of dementia, although the differences were not statistically significant.23

DELIRIUM: AVOID ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Delirium is common in hospitalized older adults, especially those who have baseline cognitive or functional impairment and are exposed to precipitating factors such as treatment with anticholinergic or narcotic medications, infection, surgery, or admission to an intensive care unit.24

Delirium at discharge predicts poor outcomes

In a prospective study of 152 hospitalized patients with delirium, those who either did not recover from delirium or had only partially recovered at discharge were more likely to visit the emergency department, be rehospitalized, or die during the subsequent 3 months than those who had fully recovered from delirium at discharge.25

Multicomponent, patient-centered approach can help

A randomized trial in 377 patients in Taiwan evaluated the use of a modified Hospital Elder Life Program, consisting of 3 protocols focused on orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization. Patients were at least 65 years old and undergoing elective abdominal surgery with expected length of hospital stay longer than 6 days. The program, administered daily during hospitalization, significantly lowered postoperative delirium by 56% and hospital stay by 2 days compared with usual care.26

Prophylactic haloperidol does not improve outcomes

In a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, van den Boogaard et al studied prophylactic intravenous haloperidol in nearly 1,800 critically ill patients at high risk of delirium.27 Haloperidol did not improve survival at 28 days compared with placebo. For secondary outcomes, including delirium incidence, delirium-free and coma-free days, duration of mechanical ventilation, and hospital and intensive care department length of stay, treatment was not found to differ statistically from placebo.

Antipsychotics may worsen delirium

A double-blind, parallel-arm, dose-titrated randomized trial, conducted at 11 Australian hospices or hospitals with palliative care services, administered oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo to 247 patients with life-limiting illness and delirium. Both treatment groups had higher delirium symptom scores than the placebo group.28

In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies found no benefit of antipsychotic medications for preventing or treating delirium in hospitalized adults.29

Antipsychotics are often continued indefinitely

A retrospective chart review at a US academic health system found30 that among 487 patients with a new antipsychotic medication prescribed during hospitalization, 147 (30.2%) were discharged on an antipsychotic. Of these, 121 (82.3%) had a diagnosis of delirium. Only 15 (12.4%) had discharge summaries that included instructions for discontinuing the drug.

Another US health system retrospectively reviewed antipsychotic use and found31 that out of 260 patients who were newly exposed to an antipsychotic drug during hospitalization, 146 (56.2%) were discharged on an antipsychotic drug, and 65% of these patients were still on the drug at the time of the next hospital admission.

EXERCISE, EXERCISE, EXERCISE

Exercise recommended, but not vitamin D, to prevent falls

In 2018, the US Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendations for preventing falls in community-dwelling older adults.32 Based on the findings of several trials, the task force recommends exercise interventions for adults age 65 and older who are at increased risk for falls. Gait, balance, and functional training were studied in 17 trials, resistance training in 13, flexibility in 8, endurance training in 5, and tai chi in 3, with 5 studies including general physical activity. Exercise interventions most commonly took place for 3 sessions per week for 12 months (range 2–42 months).

The task force also recommends against vitamin D supplementation for fall prevention in community-dwelling adults age 65 or older who are not known to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency.

Early mobilization helps inpatients

Hospitalized older adults usually spend most of their time in bed. Forty-five previously ambulatory patients (age ≥ 65 without dementia or delirium) in a Veterans Affairs hospital were monitored with wireless accelerometers and were found to spend, on average, 83% of the measured hospital stay in bed. Standing or walking time ranged from 0.2% to 21%, with a median of only 3% (43 minutes a day).33

Since falls with injury became a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services nonreimbursable hospital-acquired condition, tension has arisen between promoting mobility and preventing falls.34 Two studies evaluating the adoption of mobility-restricting approaches such as bed-alarms, “fall-alert” signs, supervision of patients in the bathroom, and ensuring patients’ walking aids are within reach, did not find a significant reduction in falls or fall-related injuries.35,36

A clinically significant loss of community mobility is common after hospitalization in older adults.37 Older adults who developed mobility impairment during hospitalization had a higher risk of death in a large, retrospective study.38 A large Canadian multisite intervention trial39 that promoted early mobilization in older patients who were admitted to general medical wards resulted in increased mobilization and significantly shorter hospital stays.

POSTHOSPITAL CARE NEEDS IMPROVEMENT

After hospitalization, older adults who have difficulty with activities of daily living or complex medical needs often require continued care.

About 20% of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the United States are discharged to skilled nursing facilities.40 This is often a stressful transition, and most people have little guidance on selecting a facility and simply choose one based on its proximity to home.41

A program of frequent visits by hospital-employed physicians and advanced practice professionals at skilled nursing facilities resulted in a significantly lower 30-day readmission rate compared with nonparticipating skilled nursing facilities in the same geographic area.42

Home healthcare is recommended after hospital discharge at a rapidly increasing rate. Overall referral rates increased from 8.6% to 14.1% between 2001 and 2012, and from 14.3% to 24.0% for patients with heart failure.43 A qualitative study of home healthcare nurses found a need for improved care coordination between home healthcare agencies and discharging hospitals, including defining accountability for orders and enhancing communication.44

Unfortunately, recent research has not unveiled a breakthrough for preventing or treating cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease. But several studies from the last 2 years are helping to drive the field of geriatrics forward, providing evidence of what does and does not help a variety of issues specific to the elderly.

Based on a search of the 2017 and 2018 literature, this article presents new evidence on preventing and treating cognitive impairment, managing dementia-associated behavioral disturbances and delirium, preventing falls, and improving inpatient mobility and posthospital care transitions.

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT, DEMENTIA: STILL NO SILVER BULLET

With the exception of oral anticoagulation treatment for atrial fibrillation, there is little evidence that pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic interventions slow the onset or progression of Alzheimer disease.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

Home occupational therapy. A 2-year home-based occupational therapy intervention1 showed no evidence of slowing functional decline in patients with Alzheimer disease. The randomized controlled trial involving 180 participants consisted of monthly sessions of an intensive, well-established collaborative-care management model that included fall prevention and other safety strategies, personalized training in activities of daily living, exercise, and education. Outcome measures for activities of daily living did not differ significantly between the treatment and control groups.1

Physical activity. Whether physical activity interventions slow cognitive decline and prevent dementia in cognitively intact adults was examined in a systematic review of 32 trials.2 Most of the trials followed patients for 6 months; a few stretched for 1 or 2 years.

Evidence was insufficient to prove cognitive benefit for short-term, single-component or multicomponent physical activity interventions. However, a multidomain physical activity intervention that also included dietary modifications and cognitive training did show a delay in cognitive decline, but only “low-strength” evidence.2

Nutritional supplements. The antioxidants vitamin E and selenium were studied for their possible cognitive benefit in the double-blind randomized Prevention of Alzheimer Disease by Vitamin E and Selenium trial3 in 3,786 asymptomatic men ages 60 and older. Neither supplement was found to prevent dementia over a 7-year follow-up period.

A review of 38 trials4 evaluated the effects on cognition of omega-3 fatty acids, soy, ginkgo biloba, B vitamins, vitamin D plus calcium, vitamin C, beta-carotene, and multi-ingredient supplements. It found insufficient evidence to recommend any over-the-counter supplement for cognitive protection in adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment.

Pharmacologic treatments

Testosterone supplementation. The Testosterone Trials tested the effects of testosterone gel vs placebo for 1 year on 493 men over age 65 with low testosterone (< 275 ng/mL) and with subjective memory complaints and objective memory performance deficits. Treatment was not associated with improved memory or other cognitive functions compared with placebo.5

Antiamyloid drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in nearly 2,000 patients evaluated verubecestat, an oral beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme-1 inhibitor that reduces the amyloid-beta level in cerebrospinal fluid.6

Verubecestat did not reduce cognitive or functional decline in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease, while adverse events including rashes, falls, injuries, sleep disturbances, suicidal ideation, weight loss, and hair color change were more common in the treatment groups. The trial was terminated early because of futility at 50 months.

And in a placebo-controlled trial of solanezumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the amyloid beta peptide, no benefit was demonstrated at 80 weeks in more than 2,000 patients with Alzheimer disease.7

Multiple common agents. A well-conducted systematic review8 of 51 trials of at least a 6-month duration did not support the use of antihypertensive agents, diabetes medications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, hormones, or lipid-lowering drugs for cognitive protection for people with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment.

However, some studies found reassuring evidence that standard therapies for other conditions do not worsen cognitive decline and are protective for atrial fibrillation.8

Proton-pump inhibitors. Concern exists for a potential link between dementia risk and proton-pump inhibitors, which are widely used to treat acid-related gastrointestinal disorders.9

A prospective population-based cohort study10 of nearly 3,500 people ages 65 and older without baseline dementia screened participants for dementia every 2 years over a mean period of 7.5 years and provided further evaluation for those who screened positive. Use of proton-pump inhibitors was not found to be associated with dementia risk, even with high cumulative exposure.

Results from this study do not support avoiding proton-pump inhibitors out of concern for dementia risk, although long-term use is associated with other safety concerns.

Oral anticoagulation. The increased risk of dementia with atrial fibrillation is well documented.11

A retrospective study12 based on a Swedish health registry and using more than 444,000 patients covering more than 1.5 million years at risk found that oral anticoagulant treatment at baseline conferred a 29% lower risk of dementia in an intention-to-treat analysis and a 48% lower risk in on-treatment analysis compared with no oral anticoagulation therapy. No difference was found between new oral anticoagulants and warfarin.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is not associated with cognitive decline

For patients with severe aortic stenosis who are not surgical candidates, transcatheter aortic valve implantation is superior to standard medical therapy,13 but there are concerns of neurologic and cognitive changes after the procedure.14 A meta-analysis of 18 studies assessing cognitive performance in more than 1,000 patients (average age ≥ 80) after undergoing the procedure for severe aortic stenosis found no significant cognitive performance changes from baseline perioperatively or 3 or 6 months later.15

TREATING DEMENTIA-ASSOCIATED BEHAVIORAL DISTURBANCES

Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms often accompany dementia, but no drugs have yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to address them in this population. Nonpharmacologic interventions are recommended as first-line therapy.

Antipsychotics are not recommended

Antipsychotics are often prescribed,16 although they are associated with metabolic syndrome17 and increased risks of stroke and death.18 The FDA has issued black box warnings against using antipsychotics for behavioral management in patients with dementia. Further, the American Geriatrics Society and the American Psychiatric Association do not endorse using them as initial therapy for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.16,19

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services partnered with nursing homes to improve the quality of care for patients with dementia, with results measured as the rate of prescribing antipsychotic medications. Although the use of psychotropic medications declined after initiating the partnership, the use of mood stabilizers increased, possibly as a substitute for antipsychotics.20

Dextromethorphan-quinidine use is up, despite modest evidence of benefit

A consumer news report in 2017 stated that the use of dextromethorphan-quinidine in long-term care facilities increased by nearly 400% between 2012 and 2016.21

Evidence for its benefits comes from a 10-week, phase 2, randomized controlled trial conducted at 42 US study sites with 194 patients with probable Alzheimer disease. Compared with the placebo group, the active treatment group had mildly reduced agitation but an increased risk of falls, dizziness, and diarrhea. However, rates of adverse effects were low, and the authors concluded that treatment was generally well tolerated.22

Pimavanserin: No long-term benefit for psychosis

In a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 181 patients with possible or probable Alzheimer disease and psychotic symptoms, pimavanserin was associated with improved symptoms as measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home Version psychosis score at 6 weeks, but no difference was found compared with placebo at 12 weeks. The treatment group had more adverse events, including agitation, aggression, peripheral edema, anxiety, and symptoms of dementia, although the differences were not statistically significant.23

DELIRIUM: AVOID ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Delirium is common in hospitalized older adults, especially those who have baseline cognitive or functional impairment and are exposed to precipitating factors such as treatment with anticholinergic or narcotic medications, infection, surgery, or admission to an intensive care unit.24

Delirium at discharge predicts poor outcomes

In a prospective study of 152 hospitalized patients with delirium, those who either did not recover from delirium or had only partially recovered at discharge were more likely to visit the emergency department, be rehospitalized, or die during the subsequent 3 months than those who had fully recovered from delirium at discharge.25

Multicomponent, patient-centered approach can help

A randomized trial in 377 patients in Taiwan evaluated the use of a modified Hospital Elder Life Program, consisting of 3 protocols focused on orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization. Patients were at least 65 years old and undergoing elective abdominal surgery with expected length of hospital stay longer than 6 days. The program, administered daily during hospitalization, significantly lowered postoperative delirium by 56% and hospital stay by 2 days compared with usual care.26

Prophylactic haloperidol does not improve outcomes

In a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, van den Boogaard et al studied prophylactic intravenous haloperidol in nearly 1,800 critically ill patients at high risk of delirium.27 Haloperidol did not improve survival at 28 days compared with placebo. For secondary outcomes, including delirium incidence, delirium-free and coma-free days, duration of mechanical ventilation, and hospital and intensive care department length of stay, treatment was not found to differ statistically from placebo.

Antipsychotics may worsen delirium

A double-blind, parallel-arm, dose-titrated randomized trial, conducted at 11 Australian hospices or hospitals with palliative care services, administered oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo to 247 patients with life-limiting illness and delirium. Both treatment groups had higher delirium symptom scores than the placebo group.28

In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies found no benefit of antipsychotic medications for preventing or treating delirium in hospitalized adults.29

Antipsychotics are often continued indefinitely

A retrospective chart review at a US academic health system found30 that among 487 patients with a new antipsychotic medication prescribed during hospitalization, 147 (30.2%) were discharged on an antipsychotic. Of these, 121 (82.3%) had a diagnosis of delirium. Only 15 (12.4%) had discharge summaries that included instructions for discontinuing the drug.

Another US health system retrospectively reviewed antipsychotic use and found31 that out of 260 patients who were newly exposed to an antipsychotic drug during hospitalization, 146 (56.2%) were discharged on an antipsychotic drug, and 65% of these patients were still on the drug at the time of the next hospital admission.

EXERCISE, EXERCISE, EXERCISE

Exercise recommended, but not vitamin D, to prevent falls

In 2018, the US Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendations for preventing falls in community-dwelling older adults.32 Based on the findings of several trials, the task force recommends exercise interventions for adults age 65 and older who are at increased risk for falls. Gait, balance, and functional training were studied in 17 trials, resistance training in 13, flexibility in 8, endurance training in 5, and tai chi in 3, with 5 studies including general physical activity. Exercise interventions most commonly took place for 3 sessions per week for 12 months (range 2–42 months).

The task force also recommends against vitamin D supplementation for fall prevention in community-dwelling adults age 65 or older who are not known to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency.

Early mobilization helps inpatients

Hospitalized older adults usually spend most of their time in bed. Forty-five previously ambulatory patients (age ≥ 65 without dementia or delirium) in a Veterans Affairs hospital were monitored with wireless accelerometers and were found to spend, on average, 83% of the measured hospital stay in bed. Standing or walking time ranged from 0.2% to 21%, with a median of only 3% (43 minutes a day).33

Since falls with injury became a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services nonreimbursable hospital-acquired condition, tension has arisen between promoting mobility and preventing falls.34 Two studies evaluating the adoption of mobility-restricting approaches such as bed-alarms, “fall-alert” signs, supervision of patients in the bathroom, and ensuring patients’ walking aids are within reach, did not find a significant reduction in falls or fall-related injuries.35,36

A clinically significant loss of community mobility is common after hospitalization in older adults.37 Older adults who developed mobility impairment during hospitalization had a higher risk of death in a large, retrospective study.38 A large Canadian multisite intervention trial39 that promoted early mobilization in older patients who were admitted to general medical wards resulted in increased mobilization and significantly shorter hospital stays.

POSTHOSPITAL CARE NEEDS IMPROVEMENT

After hospitalization, older adults who have difficulty with activities of daily living or complex medical needs often require continued care.

About 20% of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the United States are discharged to skilled nursing facilities.40 This is often a stressful transition, and most people have little guidance on selecting a facility and simply choose one based on its proximity to home.41

A program of frequent visits by hospital-employed physicians and advanced practice professionals at skilled nursing facilities resulted in a significantly lower 30-day readmission rate compared with nonparticipating skilled nursing facilities in the same geographic area.42

Home healthcare is recommended after hospital discharge at a rapidly increasing rate. Overall referral rates increased from 8.6% to 14.1% between 2001 and 2012, and from 14.3% to 24.0% for patients with heart failure.43 A qualitative study of home healthcare nurses found a need for improved care coordination between home healthcare agencies and discharging hospitals, including defining accountability for orders and enhancing communication.44

- Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Schmid AA, et al. Targeting functional decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(3):164–171. doi:10.7326/M16-0830

- Brasure M, Desai P, Davila H, et al. Physical activity interventions in preventing cognitive decline and Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):30–38. doi:10.7326/M17-1528

- Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Caban-Holt A, et al. Association of antioxidant supplement use and dementia in the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease by Vitamin E and Selenium Trial (PREADViSE). JAMA Neurol 2017; 74(5):567–573. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5778

- Butler M, Nelson VA, Davila H, et al. Over-the-counter supplement interventions to prevent cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):52–62. doi:10.7326/M17-1530

- Resnick SM, Matsumoto AM, Stephens-Shields AJ, et al. Testosterone treatment and cognitive function in older men with low testosterone and age-associated memory impairment. JAMA 2017; 317(7):717–727. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.21044

- Egan MF, Kost J, Tariot PN, et al. Randomized trial of verubecestat for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(18):1691–1703. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1706441

- Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, et al. Trial of solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(4):321–330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1705971

- Fink HA, Jutkowitz E, McCarten JR, et al. Pharmacologic interventions to prevent cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):39–51. doi:10.7326/M17-1529

- Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73(4):410–416. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791

- Gray SL, Walker RL, Dublin S, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and dementia risk: prospective population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(2):247–253. doi:10.1111/jgs.15073

- de Bruijn RF, Heeringa J, Wolters FJ, et al. Association between atrial fibrillation and dementia in the general population. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72(11):1288–1294. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2161

- Friberg L, Rosenqvist M. Less dementia with oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(6):453–460. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx579

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(17):1597–1607. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008232

- Haussig S, Mangner N, Dwyer MG, et al. Effect of a cerebral protection device on brain lesions following transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the CLEAN-TAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 316(6):592–601. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10302

- Khan MM, Herrmann N, Gallagher D, et al. Cognitive outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(2):254–262. doi:10.1111/jgs.15123

- Choosing Wisely; ABIM Foundation. American Geriatrics Society: ten things physicians and patients should question. www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Lieberman JA 3rd. Metabolic changes associated with antipsychotic use. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 6(suppl 2):8–13. pmid:16001095

- Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005; 294(15):1934–1943. doi:10.1001/jama.294.15.1934

- Choosing Wisely; ABIM Foundation. American Psychiatric Association: five things physicians and patients should question. www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-psychiatric-association. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Kales HC. Association of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to improve dementia care with the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropics in long-term care in the United States from 2009 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(5):640–647. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0379

- CNN. The little red pill being pushed on the elderly. www.cnn.com/2017/10/12/health/nuedexta-nursing-homes-invs/index.html. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Cummings JL, Lyketsos CG, Peskind ER, et al. Effect of dextromethorphan-quinidine on agitation in patients with Alzheimer disease dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314(12):1242–1254. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10214

- Ballard C, Banister C, Khan Z, et al; ADP Investigators. Evaluation of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with Alzheimer’s disease psychosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17(3):213–222. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30039-5

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(11):1157–1165. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052321

- Cole MG, McCusker J, Bailey R, et al. Partial and no recovery from delirium after hospital discharge predict increased adverse events. Age Ageing 2017; 46(1):90–95. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw153

- Chen CC, Li HC, Liang JT, et al. Effect of a modified hospital elder life program on delirium and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2017; 152(9):827–834. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1083

- van den Boogaard M, Slooter AJC, Brüggemann RJM, et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018; 319(7):680–690. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0160

- Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(1):34–42. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7491

- Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye SK, Needham DM. Antipsychotic medication for prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64(4):705–714. doi:10.1111/jgs.14076

- Johnson KG, Fashoyin A, Madden-Fuentes R, Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP, Yanamadala M. Discharge plans for geriatric inpatients with delirium: a plan to stop antipsychotics? J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(10):2278–2281. doi:10.1111/jgs.15026

- Loh KP, Ramdass S, Garb JL, et al. Long-term outcomes of elders discharged on antipsychotics. J Hosp Med 2016; 11(8):550–555. doi:10.1002/jhm.2585

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement. JAMA 2018; 319(16):1696–1704. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3097

- Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(9):1660–1665. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

- Growdon ME, Shorr RI, Inouye SK. The tension between promoting mobility and preventing falls in the hospital. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(6):759–760. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0840

- Barker AL, Morello RT, Wolfe R, et al. 6-PACK programme to decrease fall injuries in acute hospitals: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2016; 352:h6781. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6781

- Shorr RI, Chandler AM, Mion LC, et al. Effects of an intervention to increase bed alarm use to prevent falls in hospitalized patients: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(10):692–699. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00005

- Loyd C, Beasley TM, Miltner RS, Clark D, King B, Brown CJ. Trajectories of community mobility recovery after hospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(7):1399–1403. doi:10.1111/jgs.15397

- Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden Activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med 2017; 12(6):396–401. doi:10.12788/jhm.2748

- Liu B, Moore JE, Almaawiy U, et al; MOVE ON Collaboration. Outcomes of mobilisation of vulnerable elders in Ontario (MOVE ON): a multisite interrupted time series evaluation of an implementation intervention to increase patient mobilisation. Age Ageing 2018; 47(1):112–119. doi:10.1093/ageing/afx128

- Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission 2016. www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/march-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Mor V. Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: individual and family perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(11):2459–2465. doi:10.1111/jgs.14988

- Kim LD, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg MB. Impact of a connected care model on 30-day readmission rates from skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med 2017; 12(4):238–244. doi:10.12788/jhm.2710

- Jones CD, Ginde AA, Burke RE, Wald HL, Masoudi FA, Boxer RS. Increasing home healthcare referrals upon discharge from U.S. hospitals: 2001-2012. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(6):1265–1266. doi:10.1111/jgs.13467

- Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the dots”: a qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients. J Gen Intern Med 2017; 32(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4104-0

- Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Schmid AA, et al. Targeting functional decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(3):164–171. doi:10.7326/M16-0830

- Brasure M, Desai P, Davila H, et al. Physical activity interventions in preventing cognitive decline and Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):30–38. doi:10.7326/M17-1528

- Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Caban-Holt A, et al. Association of antioxidant supplement use and dementia in the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease by Vitamin E and Selenium Trial (PREADViSE). JAMA Neurol 2017; 74(5):567–573. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5778

- Butler M, Nelson VA, Davila H, et al. Over-the-counter supplement interventions to prevent cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):52–62. doi:10.7326/M17-1530

- Resnick SM, Matsumoto AM, Stephens-Shields AJ, et al. Testosterone treatment and cognitive function in older men with low testosterone and age-associated memory impairment. JAMA 2017; 317(7):717–727. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.21044

- Egan MF, Kost J, Tariot PN, et al. Randomized trial of verubecestat for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(18):1691–1703. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1706441

- Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, et al. Trial of solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(4):321–330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1705971

- Fink HA, Jutkowitz E, McCarten JR, et al. Pharmacologic interventions to prevent cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(1):39–51. doi:10.7326/M17-1529

- Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73(4):410–416. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791

- Gray SL, Walker RL, Dublin S, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and dementia risk: prospective population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(2):247–253. doi:10.1111/jgs.15073

- de Bruijn RF, Heeringa J, Wolters FJ, et al. Association between atrial fibrillation and dementia in the general population. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72(11):1288–1294. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2161

- Friberg L, Rosenqvist M. Less dementia with oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(6):453–460. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx579

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(17):1597–1607. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008232

- Haussig S, Mangner N, Dwyer MG, et al. Effect of a cerebral protection device on brain lesions following transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the CLEAN-TAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 316(6):592–601. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10302

- Khan MM, Herrmann N, Gallagher D, et al. Cognitive outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(2):254–262. doi:10.1111/jgs.15123

- Choosing Wisely; ABIM Foundation. American Geriatrics Society: ten things physicians and patients should question. www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Lieberman JA 3rd. Metabolic changes associated with antipsychotic use. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 6(suppl 2):8–13. pmid:16001095

- Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005; 294(15):1934–1943. doi:10.1001/jama.294.15.1934

- Choosing Wisely; ABIM Foundation. American Psychiatric Association: five things physicians and patients should question. www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-psychiatric-association. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Kales HC. Association of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to improve dementia care with the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropics in long-term care in the United States from 2009 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(5):640–647. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0379

- CNN. The little red pill being pushed on the elderly. www.cnn.com/2017/10/12/health/nuedexta-nursing-homes-invs/index.html. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Cummings JL, Lyketsos CG, Peskind ER, et al. Effect of dextromethorphan-quinidine on agitation in patients with Alzheimer disease dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314(12):1242–1254. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10214

- Ballard C, Banister C, Khan Z, et al; ADP Investigators. Evaluation of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with Alzheimer’s disease psychosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17(3):213–222. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30039-5

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(11):1157–1165. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052321

- Cole MG, McCusker J, Bailey R, et al. Partial and no recovery from delirium after hospital discharge predict increased adverse events. Age Ageing 2017; 46(1):90–95. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw153

- Chen CC, Li HC, Liang JT, et al. Effect of a modified hospital elder life program on delirium and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2017; 152(9):827–834. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1083

- van den Boogaard M, Slooter AJC, Brüggemann RJM, et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018; 319(7):680–690. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0160

- Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(1):34–42. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7491

- Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye SK, Needham DM. Antipsychotic medication for prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64(4):705–714. doi:10.1111/jgs.14076

- Johnson KG, Fashoyin A, Madden-Fuentes R, Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP, Yanamadala M. Discharge plans for geriatric inpatients with delirium: a plan to stop antipsychotics? J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(10):2278–2281. doi:10.1111/jgs.15026

- Loh KP, Ramdass S, Garb JL, et al. Long-term outcomes of elders discharged on antipsychotics. J Hosp Med 2016; 11(8):550–555. doi:10.1002/jhm.2585

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement. JAMA 2018; 319(16):1696–1704. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3097

- Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(9):1660–1665. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

- Growdon ME, Shorr RI, Inouye SK. The tension between promoting mobility and preventing falls in the hospital. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177(6):759–760. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0840

- Barker AL, Morello RT, Wolfe R, et al. 6-PACK programme to decrease fall injuries in acute hospitals: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2016; 352:h6781. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6781

- Shorr RI, Chandler AM, Mion LC, et al. Effects of an intervention to increase bed alarm use to prevent falls in hospitalized patients: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(10):692–699. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00005

- Loyd C, Beasley TM, Miltner RS, Clark D, King B, Brown CJ. Trajectories of community mobility recovery after hospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66(7):1399–1403. doi:10.1111/jgs.15397

- Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden Activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med 2017; 12(6):396–401. doi:10.12788/jhm.2748

- Liu B, Moore JE, Almaawiy U, et al; MOVE ON Collaboration. Outcomes of mobilisation of vulnerable elders in Ontario (MOVE ON): a multisite interrupted time series evaluation of an implementation intervention to increase patient mobilisation. Age Ageing 2018; 47(1):112–119. doi:10.1093/ageing/afx128

- Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission 2016. www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/march-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Mor V. Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: individual and family perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(11):2459–2465. doi:10.1111/jgs.14988

- Kim LD, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg MB. Impact of a connected care model on 30-day readmission rates from skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med 2017; 12(4):238–244. doi:10.12788/jhm.2710

- Jones CD, Ginde AA, Burke RE, Wald HL, Masoudi FA, Boxer RS. Increasing home healthcare referrals upon discharge from U.S. hospitals: 2001-2012. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(6):1265–1266. doi:10.1111/jgs.13467

- Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the dots”: a qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients. J Gen Intern Med 2017; 32(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4104-0

KEY POINTS

- Oral anticoagulant treatment for atrial fibrillation helps preserve cognitive function.

- Antipsychotics are not recommended as initial therapy for dementia-associated behavioral disturbances or for hospitalization-induced delirium.

- A multicomponent inpatient program can help prevent postoperative delirium in hospitalized patients.

- The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends exercise to prevent falls.

- Early mobility should be encouraged for hospitalized patients.

- Better continuity of care between hospitals and skilled nursing facilities can reduce hospital readmission rates.

Alzheimer dementia: Starting, stopping drug therapy

Alzheimer disease is the most common form of dementia. In 2016, an estimated 5.2 million Americans age 65 and older had Alzheimer disease. The prevalence is projected to increase to 13.8 million by 2050, including 7 million people age 85 and older.1

Although no cure for dementia exists, several cognition-enhancing drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat the symptoms of Alzheimer dementia. The purpose of these drugs is to stabilize cognitive and functional status, with a secondary benefit of potentially reducing behavioral problems associated with dementia.

CURRENTLY APPROVED DRUGS

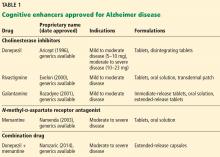

Two classes of drugs are approved to treat Alzheimer disease: cholinesterase inhibitors and an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist (Table 1).

Cholinesterase inhibitors

The cholinesterase inhibitors act by reversibly binding and inactivating acetylcholinesterase, consequently increasing the time the neurotransmitter acetylcholine remains in the synaptic cleft. The 3 FDA-approved cholinesterase inhibitors are donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine. Tacrine, the first approved cholinesterase inhibitor, was removed from the US market after reports of severe hepatic toxicity.2

The clinical efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in improving cognitive function has been shown in several randomized controlled trials.3–10 However, benefits were generally modest, and some trials used questionable methodology, leading experts to challenge the overall efficacy of these agents.

All 3 drugs are approved for mild to moderate Alzheimer disease (stages 4–6 on the Global Deterioration Scale; Table 2)11,12; only donepezil is approved for severe Alzheimer disease. Rivastigmine has an added indication for treating mild to moderate dementia associated with Parkinson disease. Cholinesterase inhibitors are often used off-label to treat other forms of dementia such as vascular dementia, mixed dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies.13

NMDA receptor antagonist

Memantine, currently the only FDA-approved NMDA receptor antagonist, acts by reducing neuronal calcium ion influx and its associated excitation and toxicity. Memantine is approved for moderate to severe Alzheimer disease.

Combination therapy

Often, these 2 classes of medications are prescribed in combination. In a randomized controlled trial that added memantine to stable doses of donepezil, patients had significantly better clinical response on combination therapy than on cholinesterase inhibitor monotherapy.14