User login

Rural Residency Curricula: Potential Target for Improved Access to Care?

To the Editor:

There is an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice in the United States, leading to growing problems with rural access to care. The provision of rural clinical experiences and telehealth in dermatology residency training might increase the likelihood of trainees establishing a rural practice.

In 2017, the American Academy of Dermatology released an updated statement supporting direct patient access to board-certified dermatologists in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with skin disease.1 Twenty percent of the US population lives in a rural and medically underserved location, yet these areas remain largely underserved, in part because of an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice.2-4 Successful approaches to improving rural access to dermatology care are poorly defined in the literature.

Several variables have been shown to influence a young physician’s decision to establish a clinical practice in geographically isolated areas, including rural upbringing, longitudinal rural clinical experiences during medical training, and family influences.5 Location of residency training is an additional variable that impacts practice location, though migration following dermatology residency is a complex phenomenon. However, training location does not guarantee retention of dermatology graduates in any particular geographic area.6 Practice incentives and stipends might encourage rural dermatology practice, yet these programs are underfunded. Last, telemedicine in dermatology (including teledermatology and teledermoscopy), though not always an ideal substitute for a live visit, can improve access to care in geographically isolated or underserved areas in general.7-9

Focused recruitment of medical students interested in rural dermatology practice to accredited dermatology residency programs aligned with this goal represents another approach to improve geographic diversity in the field of dermatology. Online access to this information would be useful for both applicants and their mentors.

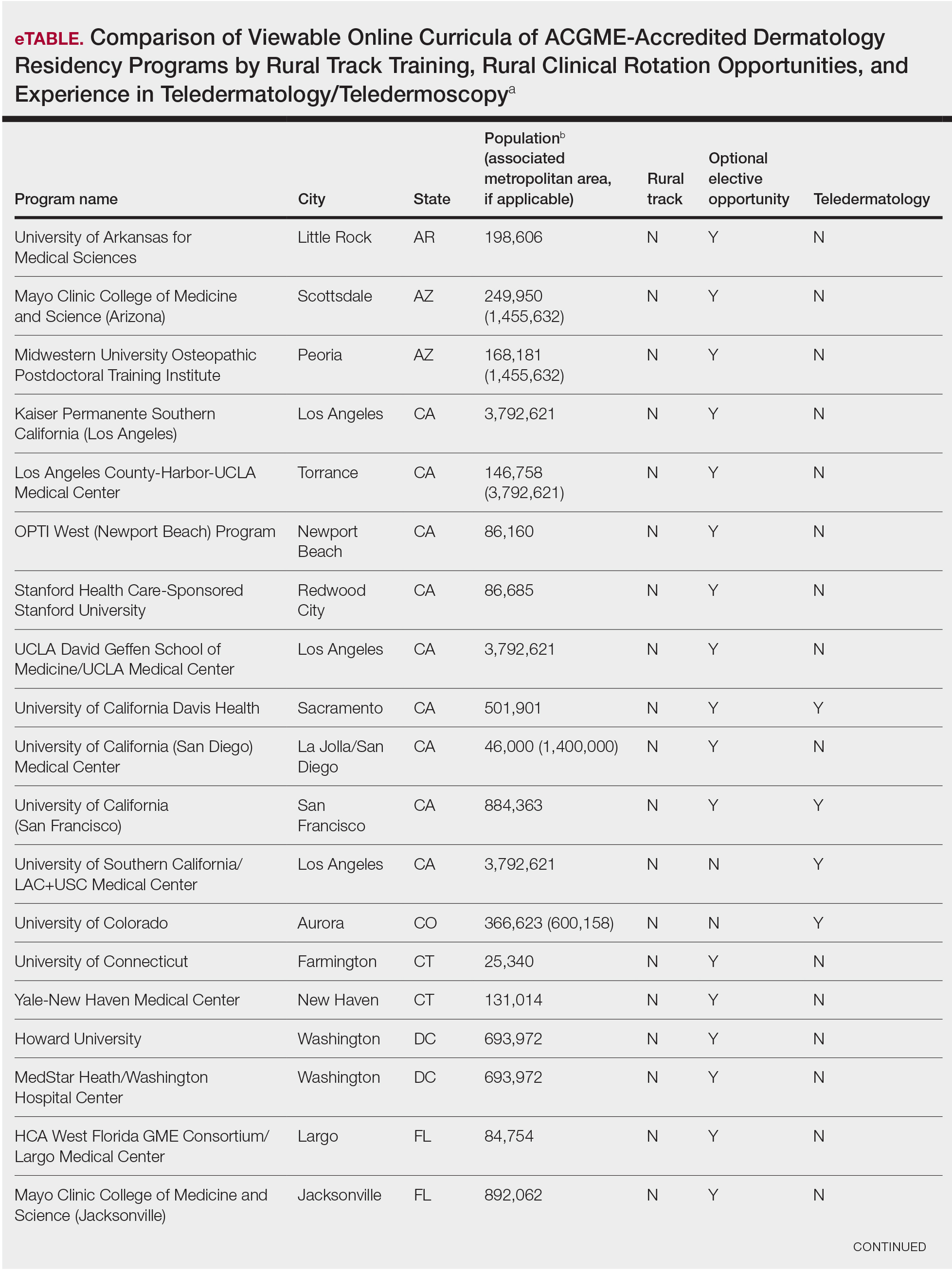

We assessed viewable online curricula related to rural dermatology and telemedicine experiences at all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited residency programs. Telemedicine experiences at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health systems also were assessed.

Methods

This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota)(IRB #STUDY00004915) because no human subjects were involved. Online curricula of all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States and Puerto Rico were reviewed from November to December 2018. The following information was recorded: specialized “rural-track” training; optional elective time in rural settings; teledermatology training; and teledermoscopy training.

Additionally, population density at each program’s primary location was determined using US Census Bureau data and with consideration to communities contained within particular Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)(eTable). Data were obtained from the VHA system to assess teledermatology services at VHA locations affiliated with residency programs.

Results

Of 154 dermatology residency programs identified in the United States and Puerto Rico, 142 were accredited at the time of data collection. Fifteen (10%) were based in communities of 50,000 individuals or fewer that were not near a large metropolitan area. One program (<1%) offered a specific rural track. Fifty-six programs (39%) cited optional rotations or clinical electives, or both, that could be utilized for a rural experience. Eighteen (12%) offered teledermatology experiences and 1 (<1%) offered teledermoscopy during training. Fifty-three programs (37%) offered a rotation at a VHA hospital that had an active teledermatology service.

Comment

Program websites are a free and easily accessible means of acquiring relevant information. The paucity of readily available data on rural dermatology and teledermatology opportunities is unfortunate and a detriment to dermatology residency applicants interested in rural practice, which may result in a missed opportunity to foster a true passion for rural medicine. A brief comment on a website can be impactful, leading to a postgraduate year 4 dermatology elective rotation at a prospective fellowship training site or a rural dermatology experience.

The paucity of dermatologists working directly in rural areas has led to development of teledermatology initiatives to reach deeply into underserved regions. One of the largest providers of teledermatology is the VHA, which standardized its teledermatology efforts in 2012 and provides remarkable educational opportunities for dermatology residents. However, many residency program and VHA websites provide no information about the participation of dermatology residents in the provision of teledermatology services.

A limitation of this study is that it is based on online published curricula. Dermatology residency programs with excellent rural curricula that are not published online might exist.

Residency program directors with an interest in geographic diversity are encouraged to provide rural and teledermatology opportunities and to update these offerings on their websites, which is a simple modifiable strategy that can impact the rural dermatology care gap by recruiting students interested in filling this role. These efforts should be studied to determine whether this strategy impacts resident selection as well as whether focused rural and telemedicine exposure during training increases the likelihood of establishing a rural dermatology practice in the future.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on access to specialty care and direct access to dermatologic care. Revised May 20, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://server.aad.org/forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Access%20to%20Specialty%20Care%20and%20Direct%20Access%20to%20Dermatologic%20Care.pdf

- Dill MJ, Salsberg ES. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections Through 2025. Center for Workforce Studies, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC); November 2008. Accessed December 13, 2020. http://innovationlabs.com/pa_future/1/background_docs/AAMC%20Complexities%20of%20physician%20demand,%202008.pdf

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1265-1271.

- Landow SM, Oh DH, Weinstock MA. Teledermatology within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002-2014. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:769-773.

- Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PloS One. 2011;6:e28687.

- Lewis H, Becevic M, Myers D, et al. Dermatology ECHO—an innovative solution to address limited access to dermatology expertise. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18:4415.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2012:148:650-651.

To the Editor:

There is an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice in the United States, leading to growing problems with rural access to care. The provision of rural clinical experiences and telehealth in dermatology residency training might increase the likelihood of trainees establishing a rural practice.

In 2017, the American Academy of Dermatology released an updated statement supporting direct patient access to board-certified dermatologists in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with skin disease.1 Twenty percent of the US population lives in a rural and medically underserved location, yet these areas remain largely underserved, in part because of an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice.2-4 Successful approaches to improving rural access to dermatology care are poorly defined in the literature.

Several variables have been shown to influence a young physician’s decision to establish a clinical practice in geographically isolated areas, including rural upbringing, longitudinal rural clinical experiences during medical training, and family influences.5 Location of residency training is an additional variable that impacts practice location, though migration following dermatology residency is a complex phenomenon. However, training location does not guarantee retention of dermatology graduates in any particular geographic area.6 Practice incentives and stipends might encourage rural dermatology practice, yet these programs are underfunded. Last, telemedicine in dermatology (including teledermatology and teledermoscopy), though not always an ideal substitute for a live visit, can improve access to care in geographically isolated or underserved areas in general.7-9

Focused recruitment of medical students interested in rural dermatology practice to accredited dermatology residency programs aligned with this goal represents another approach to improve geographic diversity in the field of dermatology. Online access to this information would be useful for both applicants and their mentors.

We assessed viewable online curricula related to rural dermatology and telemedicine experiences at all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited residency programs. Telemedicine experiences at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health systems also were assessed.

Methods

This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota)(IRB #STUDY00004915) because no human subjects were involved. Online curricula of all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States and Puerto Rico were reviewed from November to December 2018. The following information was recorded: specialized “rural-track” training; optional elective time in rural settings; teledermatology training; and teledermoscopy training.

Additionally, population density at each program’s primary location was determined using US Census Bureau data and with consideration to communities contained within particular Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)(eTable). Data were obtained from the VHA system to assess teledermatology services at VHA locations affiliated with residency programs.

Results

Of 154 dermatology residency programs identified in the United States and Puerto Rico, 142 were accredited at the time of data collection. Fifteen (10%) were based in communities of 50,000 individuals or fewer that were not near a large metropolitan area. One program (<1%) offered a specific rural track. Fifty-six programs (39%) cited optional rotations or clinical electives, or both, that could be utilized for a rural experience. Eighteen (12%) offered teledermatology experiences and 1 (<1%) offered teledermoscopy during training. Fifty-three programs (37%) offered a rotation at a VHA hospital that had an active teledermatology service.

Comment

Program websites are a free and easily accessible means of acquiring relevant information. The paucity of readily available data on rural dermatology and teledermatology opportunities is unfortunate and a detriment to dermatology residency applicants interested in rural practice, which may result in a missed opportunity to foster a true passion for rural medicine. A brief comment on a website can be impactful, leading to a postgraduate year 4 dermatology elective rotation at a prospective fellowship training site or a rural dermatology experience.

The paucity of dermatologists working directly in rural areas has led to development of teledermatology initiatives to reach deeply into underserved regions. One of the largest providers of teledermatology is the VHA, which standardized its teledermatology efforts in 2012 and provides remarkable educational opportunities for dermatology residents. However, many residency program and VHA websites provide no information about the participation of dermatology residents in the provision of teledermatology services.

A limitation of this study is that it is based on online published curricula. Dermatology residency programs with excellent rural curricula that are not published online might exist.

Residency program directors with an interest in geographic diversity are encouraged to provide rural and teledermatology opportunities and to update these offerings on their websites, which is a simple modifiable strategy that can impact the rural dermatology care gap by recruiting students interested in filling this role. These efforts should be studied to determine whether this strategy impacts resident selection as well as whether focused rural and telemedicine exposure during training increases the likelihood of establishing a rural dermatology practice in the future.

To the Editor:

There is an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice in the United States, leading to growing problems with rural access to care. The provision of rural clinical experiences and telehealth in dermatology residency training might increase the likelihood of trainees establishing a rural practice.

In 2017, the American Academy of Dermatology released an updated statement supporting direct patient access to board-certified dermatologists in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with skin disease.1 Twenty percent of the US population lives in a rural and medically underserved location, yet these areas remain largely underserved, in part because of an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice.2-4 Successful approaches to improving rural access to dermatology care are poorly defined in the literature.

Several variables have been shown to influence a young physician’s decision to establish a clinical practice in geographically isolated areas, including rural upbringing, longitudinal rural clinical experiences during medical training, and family influences.5 Location of residency training is an additional variable that impacts practice location, though migration following dermatology residency is a complex phenomenon. However, training location does not guarantee retention of dermatology graduates in any particular geographic area.6 Practice incentives and stipends might encourage rural dermatology practice, yet these programs are underfunded. Last, telemedicine in dermatology (including teledermatology and teledermoscopy), though not always an ideal substitute for a live visit, can improve access to care in geographically isolated or underserved areas in general.7-9

Focused recruitment of medical students interested in rural dermatology practice to accredited dermatology residency programs aligned with this goal represents another approach to improve geographic diversity in the field of dermatology. Online access to this information would be useful for both applicants and their mentors.

We assessed viewable online curricula related to rural dermatology and telemedicine experiences at all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited residency programs. Telemedicine experiences at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health systems also were assessed.

Methods

This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota)(IRB #STUDY00004915) because no human subjects were involved. Online curricula of all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States and Puerto Rico were reviewed from November to December 2018. The following information was recorded: specialized “rural-track” training; optional elective time in rural settings; teledermatology training; and teledermoscopy training.

Additionally, population density at each program’s primary location was determined using US Census Bureau data and with consideration to communities contained within particular Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)(eTable). Data were obtained from the VHA system to assess teledermatology services at VHA locations affiliated with residency programs.

Results

Of 154 dermatology residency programs identified in the United States and Puerto Rico, 142 were accredited at the time of data collection. Fifteen (10%) were based in communities of 50,000 individuals or fewer that were not near a large metropolitan area. One program (<1%) offered a specific rural track. Fifty-six programs (39%) cited optional rotations or clinical electives, or both, that could be utilized for a rural experience. Eighteen (12%) offered teledermatology experiences and 1 (<1%) offered teledermoscopy during training. Fifty-three programs (37%) offered a rotation at a VHA hospital that had an active teledermatology service.

Comment

Program websites are a free and easily accessible means of acquiring relevant information. The paucity of readily available data on rural dermatology and teledermatology opportunities is unfortunate and a detriment to dermatology residency applicants interested in rural practice, which may result in a missed opportunity to foster a true passion for rural medicine. A brief comment on a website can be impactful, leading to a postgraduate year 4 dermatology elective rotation at a prospective fellowship training site or a rural dermatology experience.

The paucity of dermatologists working directly in rural areas has led to development of teledermatology initiatives to reach deeply into underserved regions. One of the largest providers of teledermatology is the VHA, which standardized its teledermatology efforts in 2012 and provides remarkable educational opportunities for dermatology residents. However, many residency program and VHA websites provide no information about the participation of dermatology residents in the provision of teledermatology services.

A limitation of this study is that it is based on online published curricula. Dermatology residency programs with excellent rural curricula that are not published online might exist.

Residency program directors with an interest in geographic diversity are encouraged to provide rural and teledermatology opportunities and to update these offerings on their websites, which is a simple modifiable strategy that can impact the rural dermatology care gap by recruiting students interested in filling this role. These efforts should be studied to determine whether this strategy impacts resident selection as well as whether focused rural and telemedicine exposure during training increases the likelihood of establishing a rural dermatology practice in the future.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on access to specialty care and direct access to dermatologic care. Revised May 20, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://server.aad.org/forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Access%20to%20Specialty%20Care%20and%20Direct%20Access%20to%20Dermatologic%20Care.pdf

- Dill MJ, Salsberg ES. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections Through 2025. Center for Workforce Studies, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC); November 2008. Accessed December 13, 2020. http://innovationlabs.com/pa_future/1/background_docs/AAMC%20Complexities%20of%20physician%20demand,%202008.pdf

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1265-1271.

- Landow SM, Oh DH, Weinstock MA. Teledermatology within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002-2014. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:769-773.

- Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PloS One. 2011;6:e28687.

- Lewis H, Becevic M, Myers D, et al. Dermatology ECHO—an innovative solution to address limited access to dermatology expertise. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18:4415.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2012:148:650-651.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on access to specialty care and direct access to dermatologic care. Revised May 20, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://server.aad.org/forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Access%20to%20Specialty%20Care%20and%20Direct%20Access%20to%20Dermatologic%20Care.pdf

- Dill MJ, Salsberg ES. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections Through 2025. Center for Workforce Studies, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC); November 2008. Accessed December 13, 2020. http://innovationlabs.com/pa_future/1/background_docs/AAMC%20Complexities%20of%20physician%20demand,%202008.pdf

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1265-1271.

- Landow SM, Oh DH, Weinstock MA. Teledermatology within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002-2014. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:769-773.

- Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PloS One. 2011;6:e28687.

- Lewis H, Becevic M, Myers D, et al. Dermatology ECHO—an innovative solution to address limited access to dermatology expertise. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18:4415.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2012:148:650-651.

Practice Points

- Access to dermatologic care in rural areas is a growing problem.

- Dermatology residency programs can influence medical students and resident dermatologists to provide care in rural and geographically isolated areas.

- Presenting detailed curricula that impact access to care on residency program websites could attract applicants with these career goals.

Erythematous Plaques and Nodules on the Abdomen and Groin

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

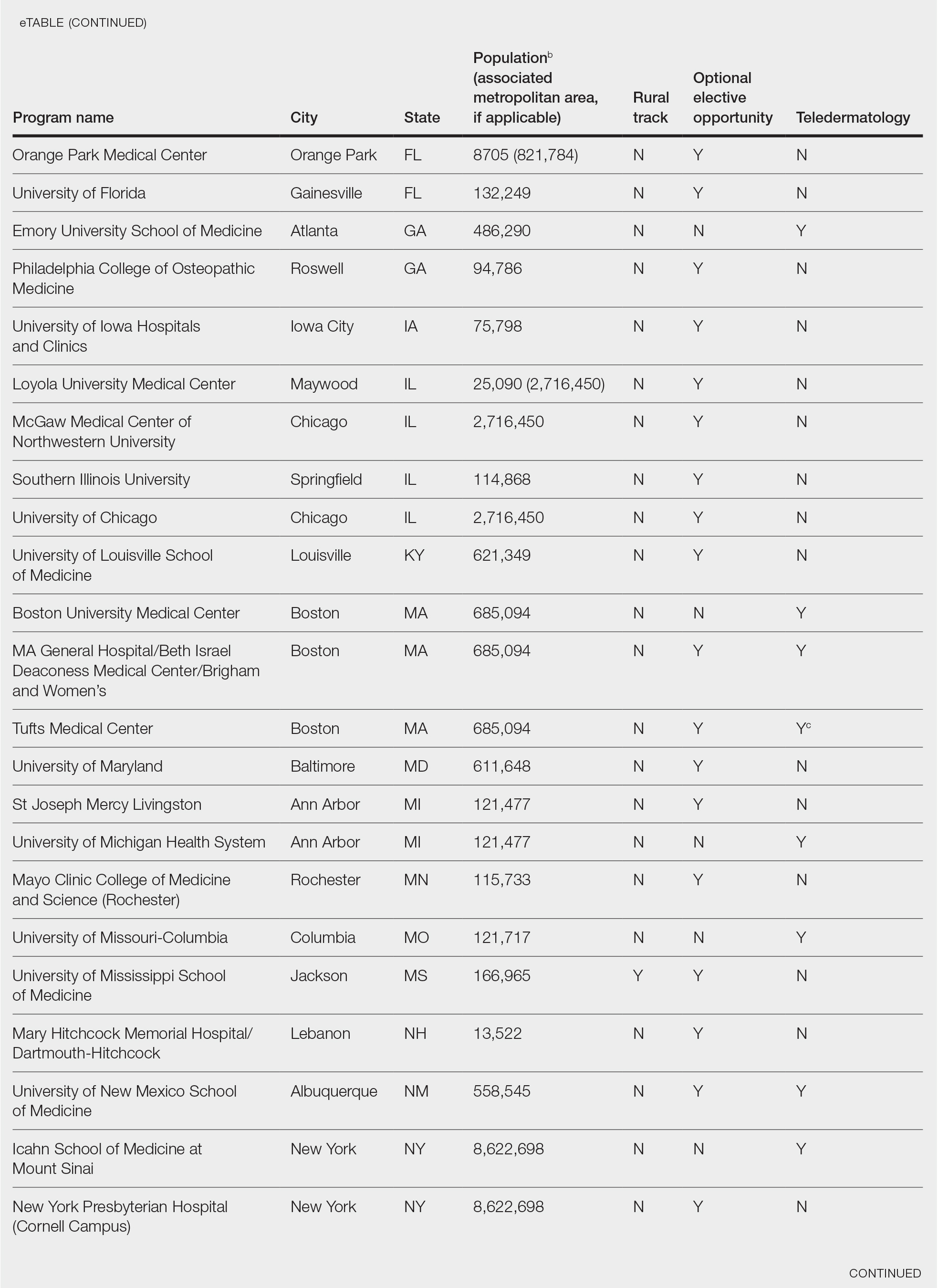

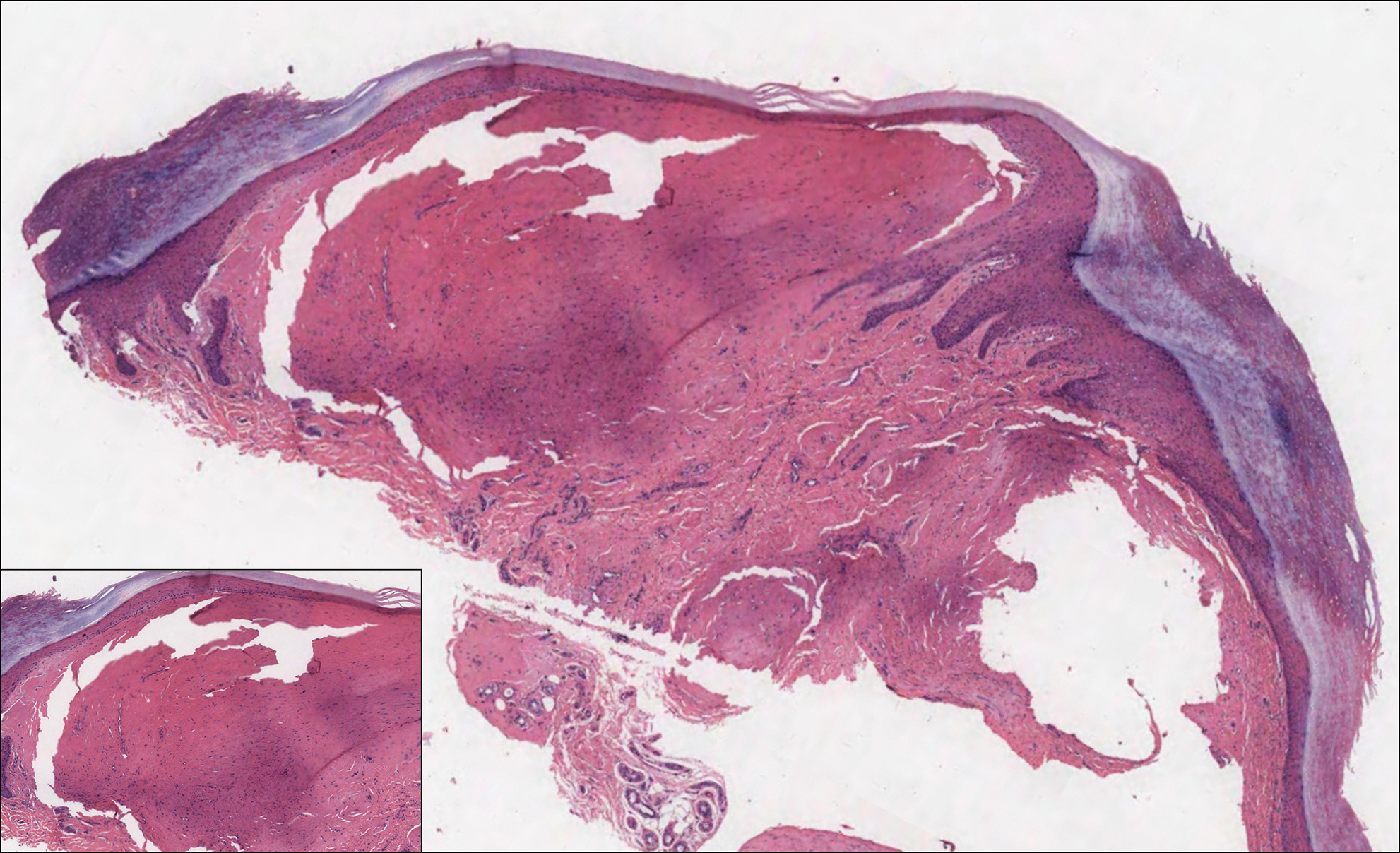

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

An 82-year-old man presented with acute abdominal pain and distension as well as an abdominal rash of 4 months' duration that was expanding despite treatment with topical miconazole. He had a history of melanoma and bladder cancer treated with cystoprostatectomy. He previously was diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. Physical examination revealed a large, well-demarcated, erythematous, smooth plaque covering the entire abdomen, scrotum, penis, inguinal folds, and bilateral upper thighs, with several satellite plaques and firm nodules clustered around the umbilicus. An 8-mm punch biopsy of a periumbilical nodule was performed.

Progressive and Translucent Plaques on the Soles

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Macroglobulinosis

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma that produces a circulating monoclonal IgM. Incidence in the United States is 1500 patients annually, most commonly men in their 70s.1 The disease process is largely indolent, with early symptoms consisting of generalized weakness, weight loss, and fatigue. Signs of lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia may emerge as the disease progresses. Diagnostic criteria include bone marrow biopsy with plasmacytoid/plasmacellular infiltrate; IgM monoclonal gammopathy; and end-organ damage, which may include cutaneous manifestations.2

Cutaneous findings in Waldenström macroglobulinemia are nonspecific and secondary to the disease's hematologic manifestations, presenting as livedo reticularis, purpura, and mucosal bleeding.3 True cutaneous involvement of the disease is rare and was first described in 1978 by Tichenor.4 Specific cutaneous lesions have 2 separate clinical presentations: (1) a primary cutaneous infiltrate of lymphoplasmacytic cells, and (2) deposition of IgM in the dermis.5 Although the primary infiltrate of neoplastic cells appears as erythematous firm papules or plaques on the face and trunk, similar to other manifestations of leukemia cutis, deposition of IgM presents as translucent papules and plaques and is located more distally, particularly on the extensor extremities.6 These depositional plaques are not pruritic but may be tender if located over sites of pressure, as seen with the plantar presentation in our patient.

Histologically, cutaneous macroglobulinosis demonstrates IgM deposition in perieccrine, perivascular, or intravascular tissue that is periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive.7 Staining with Congo red and Alcian blue is negative. In our case, biopsy showed a nodular deposition of hypocellular globular material that stained brightly with PAS and PAS diastase. With Masson trichome stain, intensity of staining diminished, suggesting that the deposition was not composed of collagen; rather, this deposition appeared to consist of IgM storage papules on immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). Further workup revealed borderline pancytopenia and elevated globulins with a monoclonal peak on serum protein electrophoresis, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous macroglobulinosis secondary to Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous, macroglobulinosis, macroglobulinemia, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia, and macroglobulinemia cutis revealed a total of 19 cases of cutaneous macroglobulinosis (including this case). The average age of presentation in these cases is 60 years (range, 29-83 years) with a predisposition for men (68% [13/19]). The development of cutaneous macroglobulinosis primarily has been noted following diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia (53% [10/19]), with some cases prior to diagnosis (37% [7/19]) or at the time of diagnosis (11% [2/19]). The presence of cutaneous lesions does not correlate with prognosis of the underlying malignancy.5,8,9

Systemic treatment of the underlying macroglobulinemia has been suggested for symptomatic cases of cutaneous macroglobulinosis.3 Prior therapy has consisted primarily of chlorambucil; however, treatment with rituximab, occasionally in conjunction with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, recently has been reported.10 Because of the symptomatic nature of our patient's lesions, she was referred to the oncology department and started on rituximab therapy. The lesions improved with therapy and have remained stable following treatment.

The differential diagnosis for tender pink papules and plaques on the arms and legs includes tophaceous gout, plantar fibromatosis, erythropoietic protoporphyria, and acral fibrokeratoma.

Gouty tophi commonly accumulate as painful, edematous, yellow to whitish nodules and tumors with erythema, often overlying joints or extensor surfaces. Histopathologic examination after formalin fixation shows needle-shaped clefts within feathery amorphous pink areas surrounded by granuloma (Figure 2).11 Yellow, needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals can be viewed under polarized microscopy in alcohol-fixed samples.

Plantar fibromatosis (Ledderhose disease) is a benign proliferation of the plantar aponeurosis linked to alcohol use; liver disease; and notably epilepsy,12 a component of our patient's medical history. Large nodules appear grossly on the plantar feet and may progress to contractures in more advanced lesions. Biopsy reveals bland hyperproliferation of fibroblasts in a background of fascial fibrous tissue (Figure 3).12 Clinically, this diagnosis is part of the differential diagnosis of plantar nodules but appears histologically different than cutaneous macroglobulinosis because there are no hyaline deposits in plantar fibromatosis.

Erythropoietic protoporphyria is a rare disorder that primarily arises due to a congenital deficiency in the ferrochelatase enzyme involved in heme biosynthesis. Erythropoietic protoporphyria is the most common porphyria among children and typically presents in infancy or early childhood as a painful photosensitivity with ensuing cutaneous manifestations and possible hepatobiliary disease. Edema and severe burning pain can be noted within minutes of sun exposure in a dose-response relationship.13 Histologic findings of erythropoietic protoporphyria differ based on acute or chronic skin changes. Acute lesions exhibit a predominantly neutrophilic interstitial dermal infiltrate with vacuoles and intercellular edema. Chronic changes include the accumulation of a PAS-positive, amorphous, hyalinelike substance, similar to the microscopic findings of cutaneous macroglobulinosis (Figure 4).13

An acral fibrokeratoma is a benign fibroepithelial tumor that clinically appears as a flesh-colored or slightly erythematous exophytic nodule that most commonly is found on the fingers or toes. Thought to arise from trauma to the affected area, it is histologically characterized by interwoven collagenous bundles with overlying epidermal hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and deep thickened rete ridges14 (Figure 5). Although multiple acral fibrokeratomas have been reported (similar to presentations of prurigo nodularis),15 they more commonly appear as solitary lesions as opposed to the numerous translucent papules seen in our patient.

- Camp BJ, Magro CM. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:962-970.

- Dimopoulos MA, Alexanian R. Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Blood. 1994;83:1452-1459.

- D'Acunto C, Nigrisoli E, Liardo EV, et al. Painful plantar nodules: a specific manifestation of cutaneous macroglobulinosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E251-E252.

- Tichenor RE. Macroglobulinemia cutis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:280-281.

- Gressier L, Hotz C, Lelièvre JD, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: a report of 2 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:165-169.

- Spicknall KE, Dubas LE, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis with monotypic plasma cells: a specific manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:442-444.

- Lüftl M, Sauter-Jenne B, Gramatzki M, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis deposits in a patient with IgM paraproteinemia/incipient Waldenström macroglobulinemia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:1000-1003.

- Mascaro JM, Montserrat E, Estrach T, et al. Specific cutaneous manifestations of Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:217-222.

- Hanke CW, Steck WD, Bergfeld WF, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:575-577.

- Oshio-Yoshii A, Fujimoto N, Shiba Y, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: successful treatment with rituximab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E30-E31.

- Gupta A, Rai S, Sinha R, et al. Tophi as an initial manifestation of gout. J Cytol. 2009;26:165-166.

- Carroll P, Henshaw RM, Garwood C, et al. Plantar fibromatosis: pathophysiology, surgical and nonsurgical therapies: an evidence-based review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018;11:168-176.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Boffeli TJ, Abben KW. Acral fibrokeratoma of the foot treated with excision and trap door flap closure: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53:449-452.

- Reed RJ. Multiple acral fibrokeratomas (a variant of prurigo nodularis). discussion of classification of acral fibrous nodules and of histogenesis of acral fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:287-297.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Macroglobulinosis

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma that produces a circulating monoclonal IgM. Incidence in the United States is 1500 patients annually, most commonly men in their 70s.1 The disease process is largely indolent, with early symptoms consisting of generalized weakness, weight loss, and fatigue. Signs of lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia may emerge as the disease progresses. Diagnostic criteria include bone marrow biopsy with plasmacytoid/plasmacellular infiltrate; IgM monoclonal gammopathy; and end-organ damage, which may include cutaneous manifestations.2

Cutaneous findings in Waldenström macroglobulinemia are nonspecific and secondary to the disease's hematologic manifestations, presenting as livedo reticularis, purpura, and mucosal bleeding.3 True cutaneous involvement of the disease is rare and was first described in 1978 by Tichenor.4 Specific cutaneous lesions have 2 separate clinical presentations: (1) a primary cutaneous infiltrate of lymphoplasmacytic cells, and (2) deposition of IgM in the dermis.5 Although the primary infiltrate of neoplastic cells appears as erythematous firm papules or plaques on the face and trunk, similar to other manifestations of leukemia cutis, deposition of IgM presents as translucent papules and plaques and is located more distally, particularly on the extensor extremities.6 These depositional plaques are not pruritic but may be tender if located over sites of pressure, as seen with the plantar presentation in our patient.

Histologically, cutaneous macroglobulinosis demonstrates IgM deposition in perieccrine, perivascular, or intravascular tissue that is periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive.7 Staining with Congo red and Alcian blue is negative. In our case, biopsy showed a nodular deposition of hypocellular globular material that stained brightly with PAS and PAS diastase. With Masson trichome stain, intensity of staining diminished, suggesting that the deposition was not composed of collagen; rather, this deposition appeared to consist of IgM storage papules on immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). Further workup revealed borderline pancytopenia and elevated globulins with a monoclonal peak on serum protein electrophoresis, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous macroglobulinosis secondary to Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous, macroglobulinosis, macroglobulinemia, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia, and macroglobulinemia cutis revealed a total of 19 cases of cutaneous macroglobulinosis (including this case). The average age of presentation in these cases is 60 years (range, 29-83 years) with a predisposition for men (68% [13/19]). The development of cutaneous macroglobulinosis primarily has been noted following diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia (53% [10/19]), with some cases prior to diagnosis (37% [7/19]) or at the time of diagnosis (11% [2/19]). The presence of cutaneous lesions does not correlate with prognosis of the underlying malignancy.5,8,9

Systemic treatment of the underlying macroglobulinemia has been suggested for symptomatic cases of cutaneous macroglobulinosis.3 Prior therapy has consisted primarily of chlorambucil; however, treatment with rituximab, occasionally in conjunction with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, recently has been reported.10 Because of the symptomatic nature of our patient's lesions, she was referred to the oncology department and started on rituximab therapy. The lesions improved with therapy and have remained stable following treatment.

The differential diagnosis for tender pink papules and plaques on the arms and legs includes tophaceous gout, plantar fibromatosis, erythropoietic protoporphyria, and acral fibrokeratoma.

Gouty tophi commonly accumulate as painful, edematous, yellow to whitish nodules and tumors with erythema, often overlying joints or extensor surfaces. Histopathologic examination after formalin fixation shows needle-shaped clefts within feathery amorphous pink areas surrounded by granuloma (Figure 2).11 Yellow, needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals can be viewed under polarized microscopy in alcohol-fixed samples.

Plantar fibromatosis (Ledderhose disease) is a benign proliferation of the plantar aponeurosis linked to alcohol use; liver disease; and notably epilepsy,12 a component of our patient's medical history. Large nodules appear grossly on the plantar feet and may progress to contractures in more advanced lesions. Biopsy reveals bland hyperproliferation of fibroblasts in a background of fascial fibrous tissue (Figure 3).12 Clinically, this diagnosis is part of the differential diagnosis of plantar nodules but appears histologically different than cutaneous macroglobulinosis because there are no hyaline deposits in plantar fibromatosis.

Erythropoietic protoporphyria is a rare disorder that primarily arises due to a congenital deficiency in the ferrochelatase enzyme involved in heme biosynthesis. Erythropoietic protoporphyria is the most common porphyria among children and typically presents in infancy or early childhood as a painful photosensitivity with ensuing cutaneous manifestations and possible hepatobiliary disease. Edema and severe burning pain can be noted within minutes of sun exposure in a dose-response relationship.13 Histologic findings of erythropoietic protoporphyria differ based on acute or chronic skin changes. Acute lesions exhibit a predominantly neutrophilic interstitial dermal infiltrate with vacuoles and intercellular edema. Chronic changes include the accumulation of a PAS-positive, amorphous, hyalinelike substance, similar to the microscopic findings of cutaneous macroglobulinosis (Figure 4).13

An acral fibrokeratoma is a benign fibroepithelial tumor that clinically appears as a flesh-colored or slightly erythematous exophytic nodule that most commonly is found on the fingers or toes. Thought to arise from trauma to the affected area, it is histologically characterized by interwoven collagenous bundles with overlying epidermal hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and deep thickened rete ridges14 (Figure 5). Although multiple acral fibrokeratomas have been reported (similar to presentations of prurigo nodularis),15 they more commonly appear as solitary lesions as opposed to the numerous translucent papules seen in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Macroglobulinosis

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma that produces a circulating monoclonal IgM. Incidence in the United States is 1500 patients annually, most commonly men in their 70s.1 The disease process is largely indolent, with early symptoms consisting of generalized weakness, weight loss, and fatigue. Signs of lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia may emerge as the disease progresses. Diagnostic criteria include bone marrow biopsy with plasmacytoid/plasmacellular infiltrate; IgM monoclonal gammopathy; and end-organ damage, which may include cutaneous manifestations.2

Cutaneous findings in Waldenström macroglobulinemia are nonspecific and secondary to the disease's hematologic manifestations, presenting as livedo reticularis, purpura, and mucosal bleeding.3 True cutaneous involvement of the disease is rare and was first described in 1978 by Tichenor.4 Specific cutaneous lesions have 2 separate clinical presentations: (1) a primary cutaneous infiltrate of lymphoplasmacytic cells, and (2) deposition of IgM in the dermis.5 Although the primary infiltrate of neoplastic cells appears as erythematous firm papules or plaques on the face and trunk, similar to other manifestations of leukemia cutis, deposition of IgM presents as translucent papules and plaques and is located more distally, particularly on the extensor extremities.6 These depositional plaques are not pruritic but may be tender if located over sites of pressure, as seen with the plantar presentation in our patient.

Histologically, cutaneous macroglobulinosis demonstrates IgM deposition in perieccrine, perivascular, or intravascular tissue that is periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive.7 Staining with Congo red and Alcian blue is negative. In our case, biopsy showed a nodular deposition of hypocellular globular material that stained brightly with PAS and PAS diastase. With Masson trichome stain, intensity of staining diminished, suggesting that the deposition was not composed of collagen; rather, this deposition appeared to consist of IgM storage papules on immunohistochemistry (Figure 1). Further workup revealed borderline pancytopenia and elevated globulins with a monoclonal peak on serum protein electrophoresis, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous macroglobulinosis secondary to Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous, macroglobulinosis, macroglobulinemia, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia, and macroglobulinemia cutis revealed a total of 19 cases of cutaneous macroglobulinosis (including this case). The average age of presentation in these cases is 60 years (range, 29-83 years) with a predisposition for men (68% [13/19]). The development of cutaneous macroglobulinosis primarily has been noted following diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia (53% [10/19]), with some cases prior to diagnosis (37% [7/19]) or at the time of diagnosis (11% [2/19]). The presence of cutaneous lesions does not correlate with prognosis of the underlying malignancy.5,8,9

Systemic treatment of the underlying macroglobulinemia has been suggested for symptomatic cases of cutaneous macroglobulinosis.3 Prior therapy has consisted primarily of chlorambucil; however, treatment with rituximab, occasionally in conjunction with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, recently has been reported.10 Because of the symptomatic nature of our patient's lesions, she was referred to the oncology department and started on rituximab therapy. The lesions improved with therapy and have remained stable following treatment.

The differential diagnosis for tender pink papules and plaques on the arms and legs includes tophaceous gout, plantar fibromatosis, erythropoietic protoporphyria, and acral fibrokeratoma.

Gouty tophi commonly accumulate as painful, edematous, yellow to whitish nodules and tumors with erythema, often overlying joints or extensor surfaces. Histopathologic examination after formalin fixation shows needle-shaped clefts within feathery amorphous pink areas surrounded by granuloma (Figure 2).11 Yellow, needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals can be viewed under polarized microscopy in alcohol-fixed samples.

Plantar fibromatosis (Ledderhose disease) is a benign proliferation of the plantar aponeurosis linked to alcohol use; liver disease; and notably epilepsy,12 a component of our patient's medical history. Large nodules appear grossly on the plantar feet and may progress to contractures in more advanced lesions. Biopsy reveals bland hyperproliferation of fibroblasts in a background of fascial fibrous tissue (Figure 3).12 Clinically, this diagnosis is part of the differential diagnosis of plantar nodules but appears histologically different than cutaneous macroglobulinosis because there are no hyaline deposits in plantar fibromatosis.

Erythropoietic protoporphyria is a rare disorder that primarily arises due to a congenital deficiency in the ferrochelatase enzyme involved in heme biosynthesis. Erythropoietic protoporphyria is the most common porphyria among children and typically presents in infancy or early childhood as a painful photosensitivity with ensuing cutaneous manifestations and possible hepatobiliary disease. Edema and severe burning pain can be noted within minutes of sun exposure in a dose-response relationship.13 Histologic findings of erythropoietic protoporphyria differ based on acute or chronic skin changes. Acute lesions exhibit a predominantly neutrophilic interstitial dermal infiltrate with vacuoles and intercellular edema. Chronic changes include the accumulation of a PAS-positive, amorphous, hyalinelike substance, similar to the microscopic findings of cutaneous macroglobulinosis (Figure 4).13

An acral fibrokeratoma is a benign fibroepithelial tumor that clinically appears as a flesh-colored or slightly erythematous exophytic nodule that most commonly is found on the fingers or toes. Thought to arise from trauma to the affected area, it is histologically characterized by interwoven collagenous bundles with overlying epidermal hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and deep thickened rete ridges14 (Figure 5). Although multiple acral fibrokeratomas have been reported (similar to presentations of prurigo nodularis),15 they more commonly appear as solitary lesions as opposed to the numerous translucent papules seen in our patient.

- Camp BJ, Magro CM. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:962-970.

- Dimopoulos MA, Alexanian R. Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Blood. 1994;83:1452-1459.

- D'Acunto C, Nigrisoli E, Liardo EV, et al. Painful plantar nodules: a specific manifestation of cutaneous macroglobulinosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E251-E252.

- Tichenor RE. Macroglobulinemia cutis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:280-281.

- Gressier L, Hotz C, Lelièvre JD, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: a report of 2 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:165-169.

- Spicknall KE, Dubas LE, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis with monotypic plasma cells: a specific manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:442-444.

- Lüftl M, Sauter-Jenne B, Gramatzki M, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis deposits in a patient with IgM paraproteinemia/incipient Waldenström macroglobulinemia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:1000-1003.

- Mascaro JM, Montserrat E, Estrach T, et al. Specific cutaneous manifestations of Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:217-222.

- Hanke CW, Steck WD, Bergfeld WF, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:575-577.

- Oshio-Yoshii A, Fujimoto N, Shiba Y, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: successful treatment with rituximab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E30-E31.

- Gupta A, Rai S, Sinha R, et al. Tophi as an initial manifestation of gout. J Cytol. 2009;26:165-166.

- Carroll P, Henshaw RM, Garwood C, et al. Plantar fibromatosis: pathophysiology, surgical and nonsurgical therapies: an evidence-based review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018;11:168-176.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Boffeli TJ, Abben KW. Acral fibrokeratoma of the foot treated with excision and trap door flap closure: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53:449-452.

- Reed RJ. Multiple acral fibrokeratomas (a variant of prurigo nodularis). discussion of classification of acral fibrous nodules and of histogenesis of acral fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:287-297.

- Camp BJ, Magro CM. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:962-970.

- Dimopoulos MA, Alexanian R. Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Blood. 1994;83:1452-1459.

- D'Acunto C, Nigrisoli E, Liardo EV, et al. Painful plantar nodules: a specific manifestation of cutaneous macroglobulinosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E251-E252.

- Tichenor RE. Macroglobulinemia cutis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:280-281.

- Gressier L, Hotz C, Lelièvre JD, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: a report of 2 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:165-169.

- Spicknall KE, Dubas LE, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis with monotypic plasma cells: a specific manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:442-444.

- Lüftl M, Sauter-Jenne B, Gramatzki M, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis deposits in a patient with IgM paraproteinemia/incipient Waldenström macroglobulinemia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:1000-1003.

- Mascaro JM, Montserrat E, Estrach T, et al. Specific cutaneous manifestations of Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:217-222.

- Hanke CW, Steck WD, Bergfeld WF, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:575-577.

- Oshio-Yoshii A, Fujimoto N, Shiba Y, et al. Cutaneous macroglobulinosis: successful treatment with rituximab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E30-E31.

- Gupta A, Rai S, Sinha R, et al. Tophi as an initial manifestation of gout. J Cytol. 2009;26:165-166.

- Carroll P, Henshaw RM, Garwood C, et al. Plantar fibromatosis: pathophysiology, surgical and nonsurgical therapies: an evidence-based review. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018;11:168-176.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Boffeli TJ, Abben KW. Acral fibrokeratoma of the foot treated with excision and trap door flap closure: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53:449-452.

- Reed RJ. Multiple acral fibrokeratomas (a variant of prurigo nodularis). discussion of classification of acral fibrous nodules and of histogenesis of acral fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:287-297.

A 64-year-old woman with a medical history of Waldenström macroglobulinemia, multiple sclerosis, and epilepsy presented with slowly growing papules on the plantar feet of 21 months' duration. She was diagnosed with Waldenström macroglobulinemia incidentally on routine blood work 3 years prior and declined treatment because she was asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed a total of 20 firm, variably sized, light pink to purple, partially translucent and telangiectatic papules and plaques bilaterally on the plantar feet. A plaque from the right sole was biopsied.