User login

Rural Residency Curricula: Potential Target for Improved Access to Care?

To the Editor:

There is an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice in the United States, leading to growing problems with rural access to care. The provision of rural clinical experiences and telehealth in dermatology residency training might increase the likelihood of trainees establishing a rural practice.

In 2017, the American Academy of Dermatology released an updated statement supporting direct patient access to board-certified dermatologists in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with skin disease.1 Twenty percent of the US population lives in a rural and medically underserved location, yet these areas remain largely underserved, in part because of an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice.2-4 Successful approaches to improving rural access to dermatology care are poorly defined in the literature.

Several variables have been shown to influence a young physician’s decision to establish a clinical practice in geographically isolated areas, including rural upbringing, longitudinal rural clinical experiences during medical training, and family influences.5 Location of residency training is an additional variable that impacts practice location, though migration following dermatology residency is a complex phenomenon. However, training location does not guarantee retention of dermatology graduates in any particular geographic area.6 Practice incentives and stipends might encourage rural dermatology practice, yet these programs are underfunded. Last, telemedicine in dermatology (including teledermatology and teledermoscopy), though not always an ideal substitute for a live visit, can improve access to care in geographically isolated or underserved areas in general.7-9

Focused recruitment of medical students interested in rural dermatology practice to accredited dermatology residency programs aligned with this goal represents another approach to improve geographic diversity in the field of dermatology. Online access to this information would be useful for both applicants and their mentors.

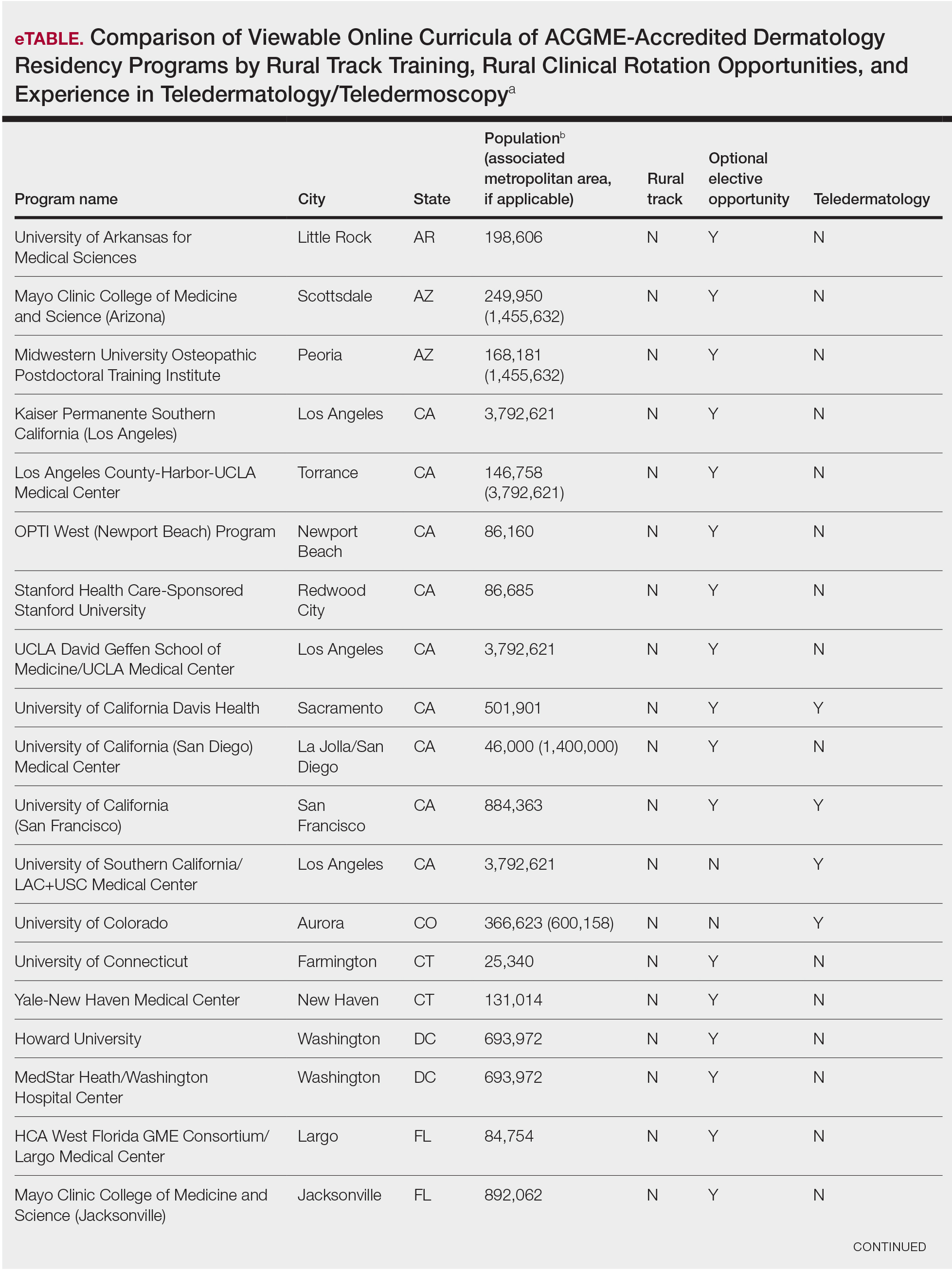

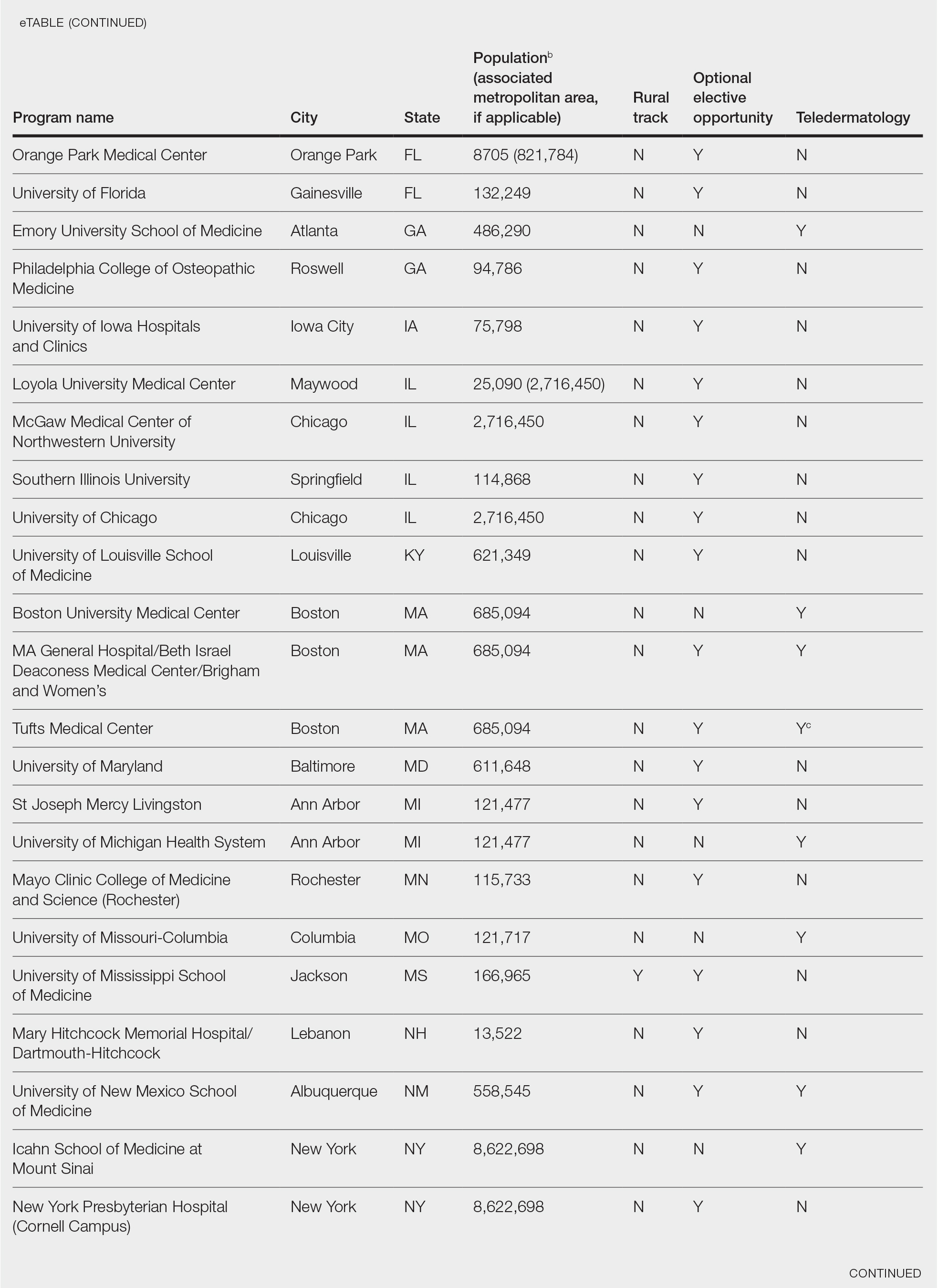

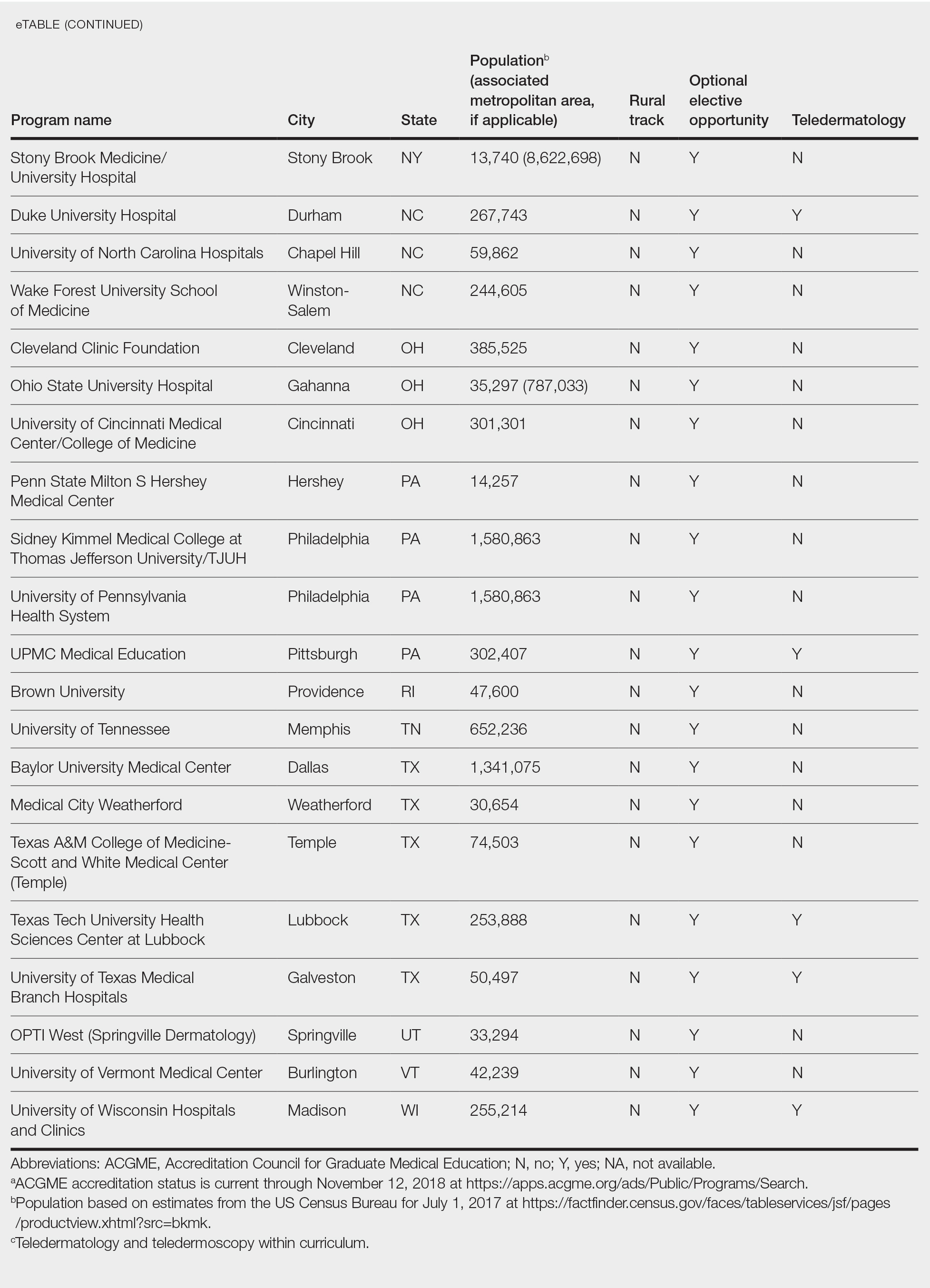

We assessed viewable online curricula related to rural dermatology and telemedicine experiences at all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited residency programs. Telemedicine experiences at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health systems also were assessed.

Methods

This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota)(IRB #STUDY00004915) because no human subjects were involved. Online curricula of all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States and Puerto Rico were reviewed from November to December 2018. The following information was recorded: specialized “rural-track” training; optional elective time in rural settings; teledermatology training; and teledermoscopy training.

Additionally, population density at each program’s primary location was determined using US Census Bureau data and with consideration to communities contained within particular Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)(eTable). Data were obtained from the VHA system to assess teledermatology services at VHA locations affiliated with residency programs.

Results

Of 154 dermatology residency programs identified in the United States and Puerto Rico, 142 were accredited at the time of data collection. Fifteen (10%) were based in communities of 50,000 individuals or fewer that were not near a large metropolitan area. One program (<1%) offered a specific rural track. Fifty-six programs (39%) cited optional rotations or clinical electives, or both, that could be utilized for a rural experience. Eighteen (12%) offered teledermatology experiences and 1 (<1%) offered teledermoscopy during training. Fifty-three programs (37%) offered a rotation at a VHA hospital that had an active teledermatology service.

Comment

Program websites are a free and easily accessible means of acquiring relevant information. The paucity of readily available data on rural dermatology and teledermatology opportunities is unfortunate and a detriment to dermatology residency applicants interested in rural practice, which may result in a missed opportunity to foster a true passion for rural medicine. A brief comment on a website can be impactful, leading to a postgraduate year 4 dermatology elective rotation at a prospective fellowship training site or a rural dermatology experience.

The paucity of dermatologists working directly in rural areas has led to development of teledermatology initiatives to reach deeply into underserved regions. One of the largest providers of teledermatology is the VHA, which standardized its teledermatology efforts in 2012 and provides remarkable educational opportunities for dermatology residents. However, many residency program and VHA websites provide no information about the participation of dermatology residents in the provision of teledermatology services.

A limitation of this study is that it is based on online published curricula. Dermatology residency programs with excellent rural curricula that are not published online might exist.

Residency program directors with an interest in geographic diversity are encouraged to provide rural and teledermatology opportunities and to update these offerings on their websites, which is a simple modifiable strategy that can impact the rural dermatology care gap by recruiting students interested in filling this role. These efforts should be studied to determine whether this strategy impacts resident selection as well as whether focused rural and telemedicine exposure during training increases the likelihood of establishing a rural dermatology practice in the future.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on access to specialty care and direct access to dermatologic care. Revised May 20, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://server.aad.org/forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Access%20to%20Specialty%20Care%20and%20Direct%20Access%20to%20Dermatologic%20Care.pdf

- Dill MJ, Salsberg ES. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections Through 2025. Center for Workforce Studies, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC); November 2008. Accessed December 13, 2020. http://innovationlabs.com/pa_future/1/background_docs/AAMC%20Complexities%20of%20physician%20demand,%202008.pdf

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1265-1271.

- Landow SM, Oh DH, Weinstock MA. Teledermatology within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002-2014. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:769-773.

- Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PloS One. 2011;6:e28687.

- Lewis H, Becevic M, Myers D, et al. Dermatology ECHO—an innovative solution to address limited access to dermatology expertise. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18:4415.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2012:148:650-651.

To the Editor:

There is an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice in the United States, leading to growing problems with rural access to care. The provision of rural clinical experiences and telehealth in dermatology residency training might increase the likelihood of trainees establishing a rural practice.

In 2017, the American Academy of Dermatology released an updated statement supporting direct patient access to board-certified dermatologists in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with skin disease.1 Twenty percent of the US population lives in a rural and medically underserved location, yet these areas remain largely underserved, in part because of an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice.2-4 Successful approaches to improving rural access to dermatology care are poorly defined in the literature.

Several variables have been shown to influence a young physician’s decision to establish a clinical practice in geographically isolated areas, including rural upbringing, longitudinal rural clinical experiences during medical training, and family influences.5 Location of residency training is an additional variable that impacts practice location, though migration following dermatology residency is a complex phenomenon. However, training location does not guarantee retention of dermatology graduates in any particular geographic area.6 Practice incentives and stipends might encourage rural dermatology practice, yet these programs are underfunded. Last, telemedicine in dermatology (including teledermatology and teledermoscopy), though not always an ideal substitute for a live visit, can improve access to care in geographically isolated or underserved areas in general.7-9

Focused recruitment of medical students interested in rural dermatology practice to accredited dermatology residency programs aligned with this goal represents another approach to improve geographic diversity in the field of dermatology. Online access to this information would be useful for both applicants and their mentors.

We assessed viewable online curricula related to rural dermatology and telemedicine experiences at all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited residency programs. Telemedicine experiences at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health systems also were assessed.

Methods

This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota)(IRB #STUDY00004915) because no human subjects were involved. Online curricula of all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States and Puerto Rico were reviewed from November to December 2018. The following information was recorded: specialized “rural-track” training; optional elective time in rural settings; teledermatology training; and teledermoscopy training.

Additionally, population density at each program’s primary location was determined using US Census Bureau data and with consideration to communities contained within particular Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)(eTable). Data were obtained from the VHA system to assess teledermatology services at VHA locations affiliated with residency programs.

Results

Of 154 dermatology residency programs identified in the United States and Puerto Rico, 142 were accredited at the time of data collection. Fifteen (10%) were based in communities of 50,000 individuals or fewer that were not near a large metropolitan area. One program (<1%) offered a specific rural track. Fifty-six programs (39%) cited optional rotations or clinical electives, or both, that could be utilized for a rural experience. Eighteen (12%) offered teledermatology experiences and 1 (<1%) offered teledermoscopy during training. Fifty-three programs (37%) offered a rotation at a VHA hospital that had an active teledermatology service.

Comment

Program websites are a free and easily accessible means of acquiring relevant information. The paucity of readily available data on rural dermatology and teledermatology opportunities is unfortunate and a detriment to dermatology residency applicants interested in rural practice, which may result in a missed opportunity to foster a true passion for rural medicine. A brief comment on a website can be impactful, leading to a postgraduate year 4 dermatology elective rotation at a prospective fellowship training site or a rural dermatology experience.

The paucity of dermatologists working directly in rural areas has led to development of teledermatology initiatives to reach deeply into underserved regions. One of the largest providers of teledermatology is the VHA, which standardized its teledermatology efforts in 2012 and provides remarkable educational opportunities for dermatology residents. However, many residency program and VHA websites provide no information about the participation of dermatology residents in the provision of teledermatology services.

A limitation of this study is that it is based on online published curricula. Dermatology residency programs with excellent rural curricula that are not published online might exist.

Residency program directors with an interest in geographic diversity are encouraged to provide rural and teledermatology opportunities and to update these offerings on their websites, which is a simple modifiable strategy that can impact the rural dermatology care gap by recruiting students interested in filling this role. These efforts should be studied to determine whether this strategy impacts resident selection as well as whether focused rural and telemedicine exposure during training increases the likelihood of establishing a rural dermatology practice in the future.

To the Editor:

There is an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice in the United States, leading to growing problems with rural access to care. The provision of rural clinical experiences and telehealth in dermatology residency training might increase the likelihood of trainees establishing a rural practice.

In 2017, the American Academy of Dermatology released an updated statement supporting direct patient access to board-certified dermatologists in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with skin disease.1 Twenty percent of the US population lives in a rural and medically underserved location, yet these areas remain largely underserved, in part because of an irrefutable trend toward urban dermatology practice.2-4 Successful approaches to improving rural access to dermatology care are poorly defined in the literature.

Several variables have been shown to influence a young physician’s decision to establish a clinical practice in geographically isolated areas, including rural upbringing, longitudinal rural clinical experiences during medical training, and family influences.5 Location of residency training is an additional variable that impacts practice location, though migration following dermatology residency is a complex phenomenon. However, training location does not guarantee retention of dermatology graduates in any particular geographic area.6 Practice incentives and stipends might encourage rural dermatology practice, yet these programs are underfunded. Last, telemedicine in dermatology (including teledermatology and teledermoscopy), though not always an ideal substitute for a live visit, can improve access to care in geographically isolated or underserved areas in general.7-9

Focused recruitment of medical students interested in rural dermatology practice to accredited dermatology residency programs aligned with this goal represents another approach to improve geographic diversity in the field of dermatology. Online access to this information would be useful for both applicants and their mentors.

We assessed viewable online curricula related to rural dermatology and telemedicine experiences at all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited residency programs. Telemedicine experiences at Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health systems also were assessed.

Methods

This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota)(IRB #STUDY00004915) because no human subjects were involved. Online curricula of all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs in the United States and Puerto Rico were reviewed from November to December 2018. The following information was recorded: specialized “rural-track” training; optional elective time in rural settings; teledermatology training; and teledermoscopy training.

Additionally, population density at each program’s primary location was determined using US Census Bureau data and with consideration to communities contained within particular Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)(eTable). Data were obtained from the VHA system to assess teledermatology services at VHA locations affiliated with residency programs.

Results

Of 154 dermatology residency programs identified in the United States and Puerto Rico, 142 were accredited at the time of data collection. Fifteen (10%) were based in communities of 50,000 individuals or fewer that were not near a large metropolitan area. One program (<1%) offered a specific rural track. Fifty-six programs (39%) cited optional rotations or clinical electives, or both, that could be utilized for a rural experience. Eighteen (12%) offered teledermatology experiences and 1 (<1%) offered teledermoscopy during training. Fifty-three programs (37%) offered a rotation at a VHA hospital that had an active teledermatology service.

Comment

Program websites are a free and easily accessible means of acquiring relevant information. The paucity of readily available data on rural dermatology and teledermatology opportunities is unfortunate and a detriment to dermatology residency applicants interested in rural practice, which may result in a missed opportunity to foster a true passion for rural medicine. A brief comment on a website can be impactful, leading to a postgraduate year 4 dermatology elective rotation at a prospective fellowship training site or a rural dermatology experience.

The paucity of dermatologists working directly in rural areas has led to development of teledermatology initiatives to reach deeply into underserved regions. One of the largest providers of teledermatology is the VHA, which standardized its teledermatology efforts in 2012 and provides remarkable educational opportunities for dermatology residents. However, many residency program and VHA websites provide no information about the participation of dermatology residents in the provision of teledermatology services.

A limitation of this study is that it is based on online published curricula. Dermatology residency programs with excellent rural curricula that are not published online might exist.

Residency program directors with an interest in geographic diversity are encouraged to provide rural and teledermatology opportunities and to update these offerings on their websites, which is a simple modifiable strategy that can impact the rural dermatology care gap by recruiting students interested in filling this role. These efforts should be studied to determine whether this strategy impacts resident selection as well as whether focused rural and telemedicine exposure during training increases the likelihood of establishing a rural dermatology practice in the future.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on access to specialty care and direct access to dermatologic care. Revised May 20, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://server.aad.org/forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Access%20to%20Specialty%20Care%20and%20Direct%20Access%20to%20Dermatologic%20Care.pdf

- Dill MJ, Salsberg ES. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections Through 2025. Center for Workforce Studies, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC); November 2008. Accessed December 13, 2020. http://innovationlabs.com/pa_future/1/background_docs/AAMC%20Complexities%20of%20physician%20demand,%202008.pdf

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1265-1271.

- Landow SM, Oh DH, Weinstock MA. Teledermatology within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002-2014. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:769-773.

- Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PloS One. 2011;6:e28687.

- Lewis H, Becevic M, Myers D, et al. Dermatology ECHO—an innovative solution to address limited access to dermatology expertise. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18:4415.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2012:148:650-651.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on access to specialty care and direct access to dermatologic care. Revised May 20, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2020. https://server.aad.org/forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Access%20to%20Specialty%20Care%20and%20Direct%20Access%20to%20Dermatologic%20Care.pdf

- Dill MJ, Salsberg ES. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections Through 2025. Center for Workforce Studies, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC); November 2008. Accessed December 13, 2020. http://innovationlabs.com/pa_future/1/background_docs/AAMC%20Complexities%20of%20physician%20demand,%202008.pdf

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1265-1271.

- Landow SM, Oh DH, Weinstock MA. Teledermatology within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002-2014. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:769-773.

- Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L, et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PloS One. 2011;6:e28687.

- Lewis H, Becevic M, Myers D, et al. Dermatology ECHO—an innovative solution to address limited access to dermatology expertise. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18:4415.

- Edison KE, Dyer JA, Whited JD, et al. Practice gaps. the barriers and the promise of teledermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2012:148:650-651.

Practice Points

- Access to dermatologic care in rural areas is a growing problem.

- Dermatology residency programs can influence medical students and resident dermatologists to provide care in rural and geographically isolated areas.

- Presenting detailed curricula that impact access to care on residency program websites could attract applicants with these career goals.

Chronic, nonhealing leg ulcer

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

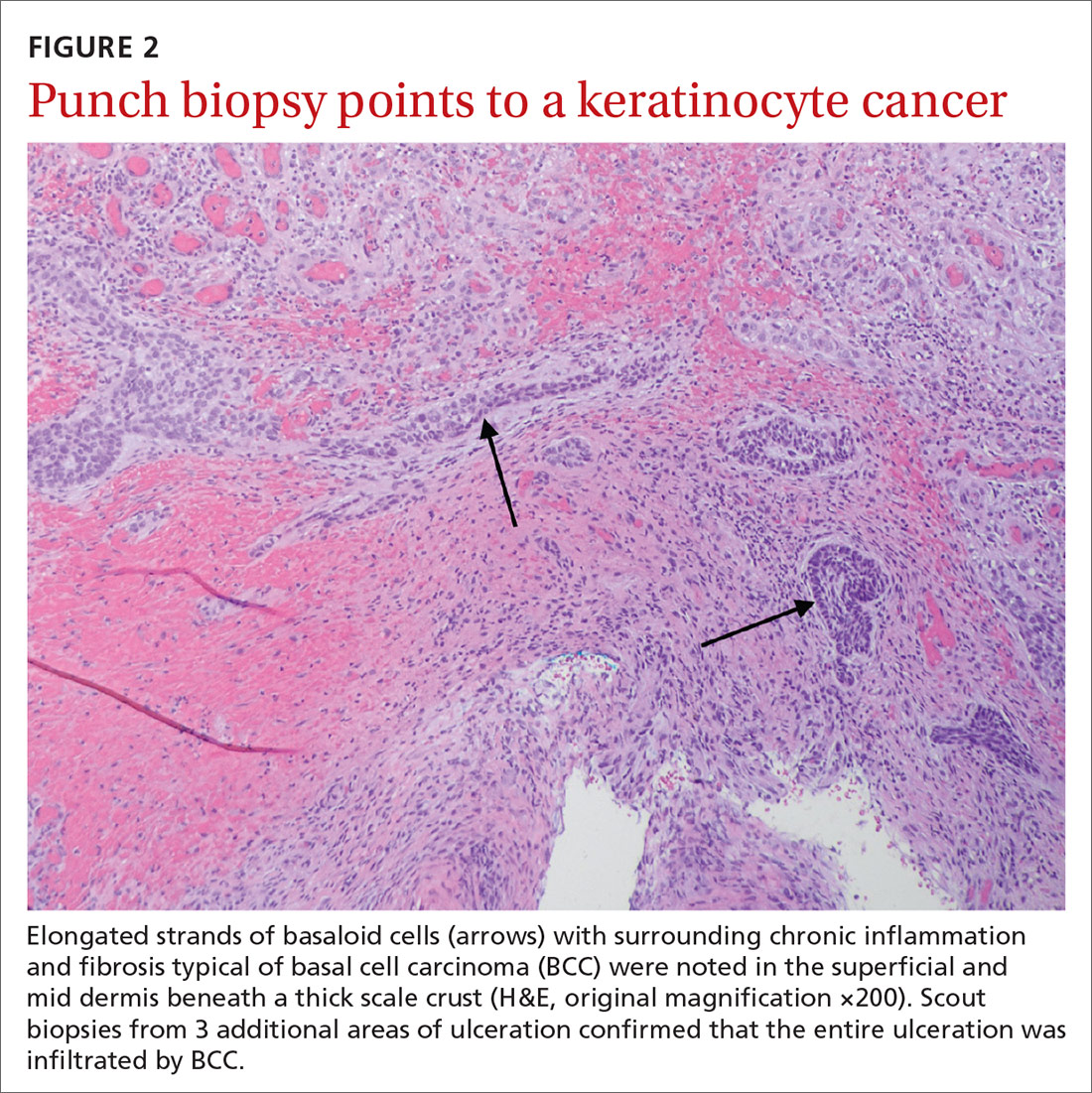

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; crastodave@gmail.com

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; crastodave@gmail.com

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; crastodave@gmail.com

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.