User login

Impact of patient-centered discharge tools: A systematic review

Patient-centered care, defined by the Institute of Medicine as “health care that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care,” has been recognized as an important factor in improving care transitions after discharge from the hospital.1 Previous efforts to improve the discharge process for hospitalized patients and reduce avoidable readmissions have focused on improving systems surrounding the patient, such as by increasing the availability of outpatient follow-up or standardizing communication between the inpatient and outpatient care teams.1,2 In fact, successful programs such as Project BOOST and the Care Transitions Interventions™ provide healthcare institutions with a “bundle” of evidence-based transitional care guidelines for discharge: they provide postdischarge transition coaches, assistance with medication self-management, timely follow-up tips, and improved patient records in order to improve postdischarge outcomes.3,4 Successful interventions, however, may not provide more services, but also engage the patient in their own care.5,6 The impact of engaging the patient in his or her own care by providing patient-friendly discharge instructions alone, however, is unknown.

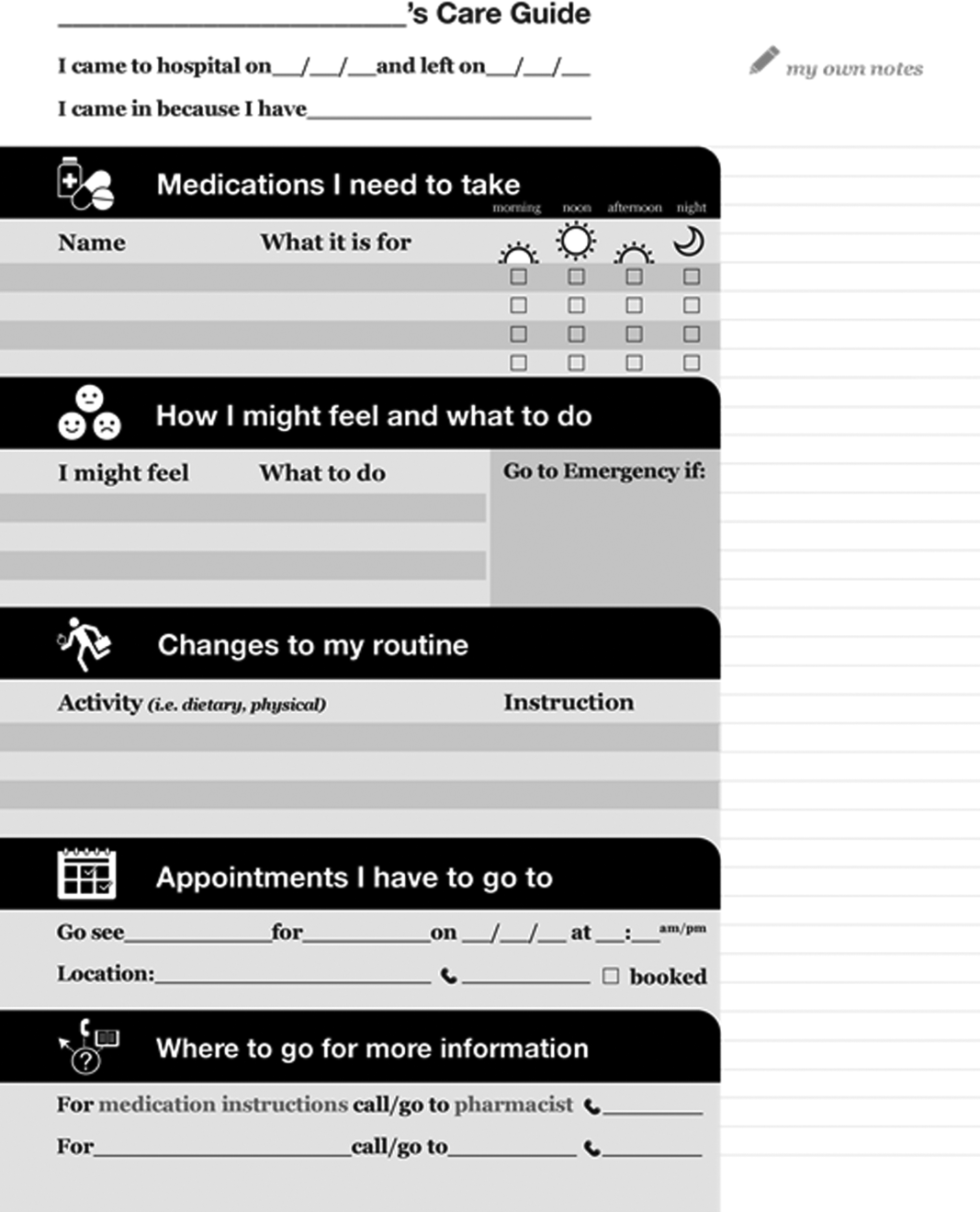

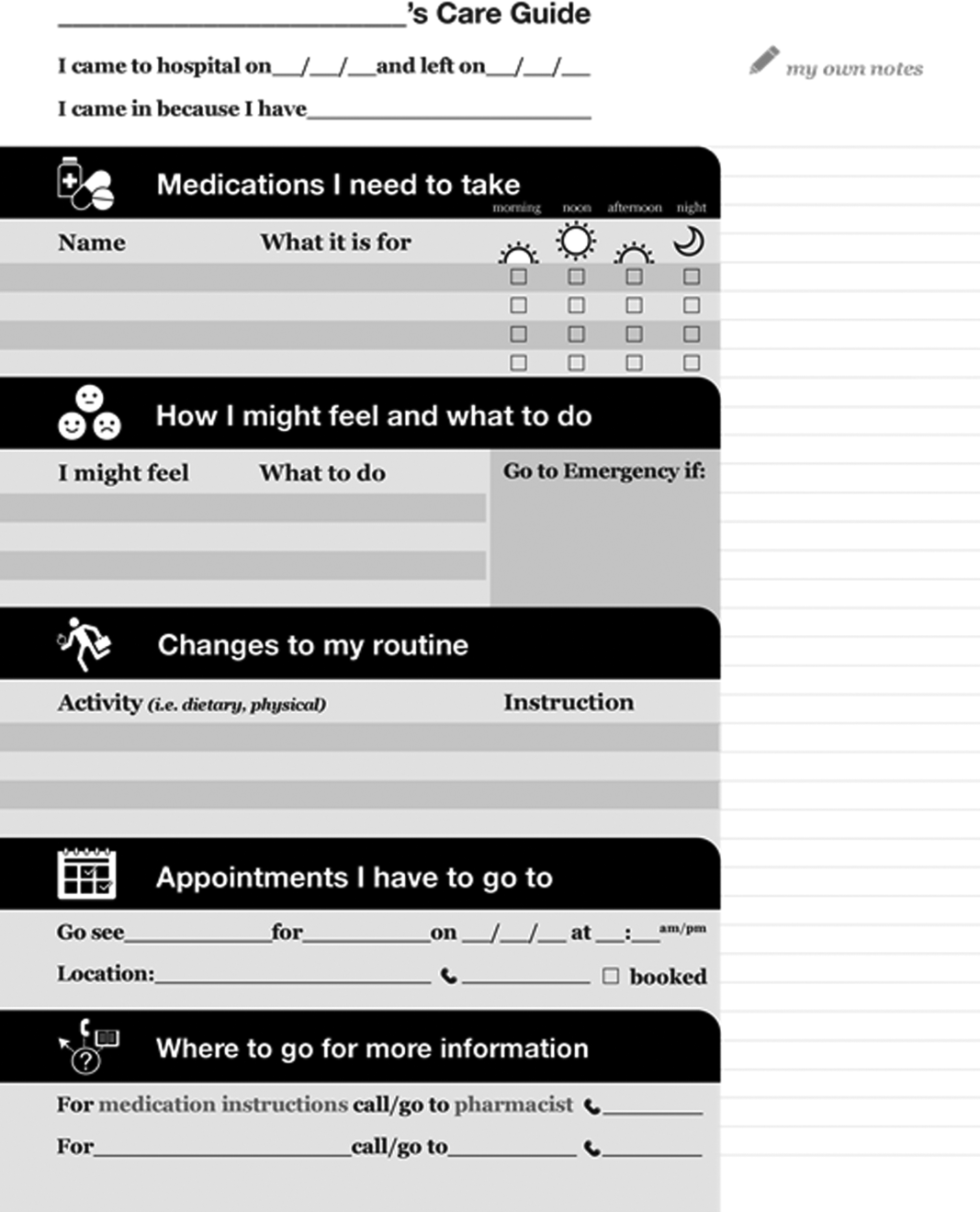

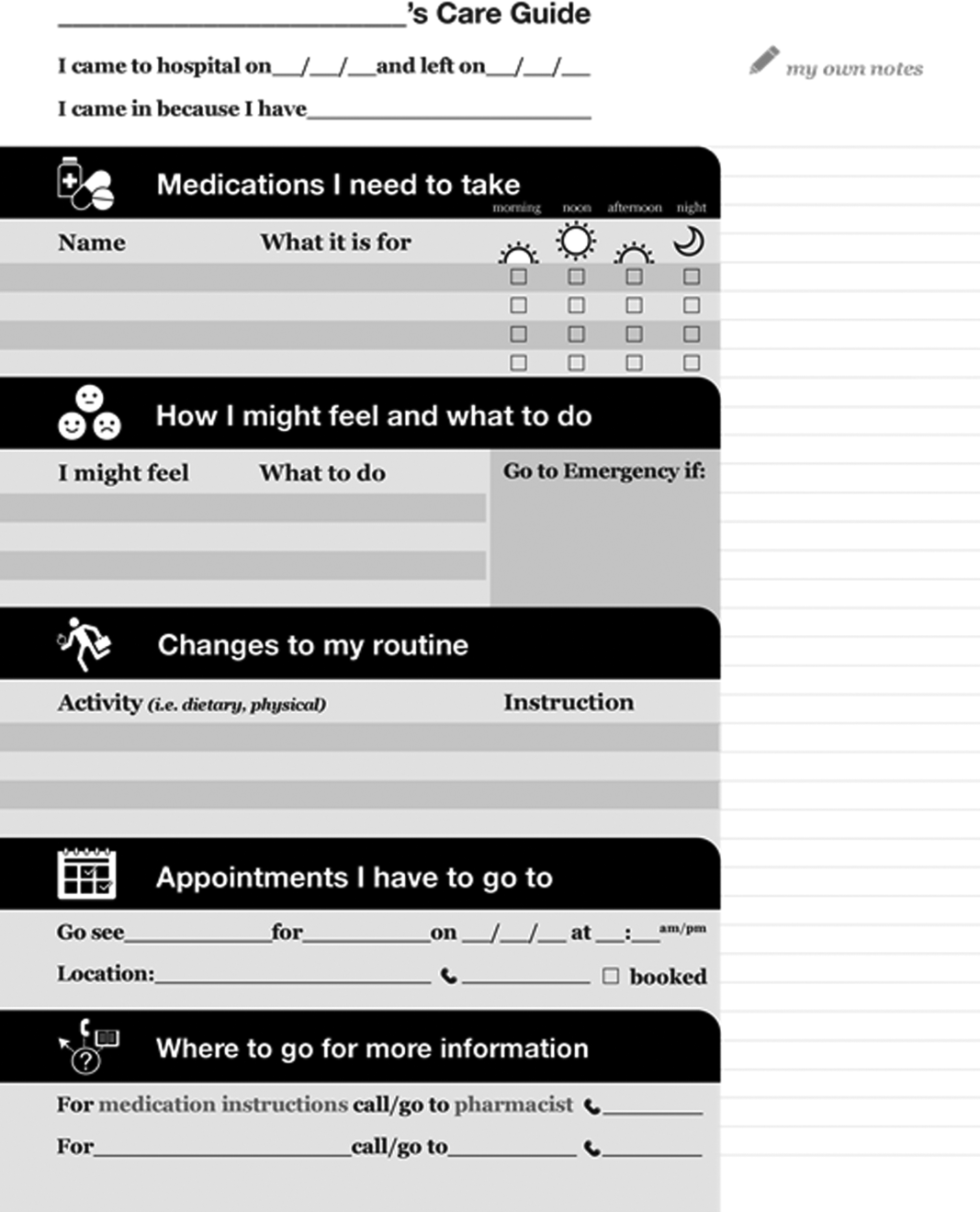

A patient-centered discharge may use tools that were designed with patients, or may involve engaging patients in an interactive process of reviewing discharge instructions and empowering them to manage aspects of their own care after leaving the hospital. This endeavour may lead to more effective use of discharge instructions and reduce the need for additional or more intensive (and costly) interventions. For example, a patient-centered discharge tool could include an educational intervention that uses the “teach-back” method, in which patients are asked to restate in their own words what they thought they heard, or in which staff use additional media or a visual design tool meant to enhance comprehension of discharge instructions.6,7 Visual aids and the use of larger fonts are particularly useful design elements for improving comprehension among non-English speakers and patients with low health literacy, who tend to have poorer recall of instructions.8-10 What may constitute essential design elements to include in a discharge instruction tool, however, is not clear.

Moreover, whether the use of discharge tools with a specific focus on patient engagement may improve postdischarge outcomes is not known. Particularly, the ability of patient-centered discharge tools to improve outcomes beyond comprehension such as self-management, adherence to discharge instructions, a reduction in unplanned visits, and a reduction in mortality has not been studied systematically. The objective of this systematic review was to review the literature on discharge instruction tools with a focus on patient engagement and their impact among hospitalized patients.

METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Statement was followed as a guideline for reporting throughout this review.11

Data Sources

A literature search was undertaken using the following databases from January 1994 or their inception date to May 2014: Medline, Embase, SIGLE, HTA, Bioethics, ASSIA, Psych Lit, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EconLit, ERIC, and BioMed Central. We also searched relevant design-focused journals such as Design Issues, Journal of Design Research, Information Design Journal, Innovation, Design Studies, and International Journal of Design, as well as reference lists from studies obtained by electronic searching. The following key words and combination of key words were used with the assistance of a medical librarian: patient discharge, patient-centered discharge, patient-centered design, design thinking, user based design, patient education, discharge summary, education. Additional search terms were added when identified from relevant articles (Appendix).

Inclusion Criteria

We included all English-language studies with patients admitted to the hospital irrespective of age, sex, or medical condition, which included a control group or time period and which measured patient outcomes within 3 months of discharge. The 3-month period after discharge is often cited as a time when outcomes could reasonably be associated with an intervention at discharge.2

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that did not have clear implementation of a patient-centered tool, a control group, or those whose tool was used in the emergency department or as an outpatient were excluded. Studies that included postdischarge tools such as home visits or telephone calls were excluded unless independent effects of the predischarge interventions were measured. Studies with outcomes reported after 3 months were excluded unless outcomes before 3 months were also clearly noted.

All searches were entered into Endnote and duplicates were removed. A 2-stage inclusion process was used. Titles and abstracts of articles were first screened for meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria by 1 reviewer. A second reviewer independently checked a 10% random sample of all the abstracts that met the initial screening criteria. If the agreement to exclude studies was less than 95%, criteria were reviewed before checking the rest of the 90% sample. In the second stage, 2 independent reviewers examined paper copies of the full articles selected in the first stage. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion or a third reviewer if no agreement could be reached.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

The following information was extracted from the full reference: type of study, population studied, control group or time period, tool used, and outcomes measured. Based on the National Health Care Quality report’s priorities and goals on patient and/or family engagement during transitions of care, educational tools were further described based on method of teaching, involvement of the care team, involvement of the patient in the design or delivery of the tool, and/or the use of visual aids.12 All primary outcomes were classified according to 3 categories: improved knowledge/comprehension, patient experience (patient satisfaction, self-management/efficacy such as functional status, both physical and mental), and health outcomes (unscheduled visits or readmissions, adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up, and mortality).

No quantitative pooling of results or meta-analysis was done given the variability and heterogeneity of studies reviewed. However, following guidelines for Effect Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Risk of Bias criteria,13 studies that had a higher risk of bias such as uncontrolled before-after studies or studies with only 1 intervention or control site (historical controls, eg) were excluded from the final review because of the difficulties in attributing causation. Only primary outcomes were reported in order to minimize type II errors.

RESULTS

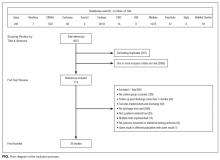

Our search revealed a total of 3699 studies after duplicates had been removed (Figure). A total of 714 references were included after initial review by title and abstract and 30 studies after full-text review. Agreement on a 10% random sample of all abstracts and full text was 79% (k=0.58) and 86% (k=0.72), respectively. Discussion was needed for fewer than 100 references, and agreement was subsequently reached for 100%.

There were 22 randomized controlled trials and 8 nonrandomized studies (5 nonrandomized controlled trials and 3 controlled before-after studies). Most of these studies were conducted in the United States (13/30 studies), followed by other European countries (5 studies), and the United Kingdom (4 studies). A large number of studies were conducted among patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors (10 studies), followed by postsurgical patients such as coronary artery bypass graft surgery or orthopaedic surgery (5 studies). Five of 30 studies were conducted among individuals older than 65 years. Most studies excluded patients who did not speak English or the country’s official language; only 3 studies included patients with limited literacy, patients who spoke other languages, or caregivers if the patients could not communicate.

Most studies tested the impact of educational discharge interventions (28 of 30 studies) (Table 1). Quite often, it was a member of the research team who carried out the patient education. Only 3 studies involved multiple members of the care team in designing or reviewing the discharge tool with the patient. Almost half (12 studies) targeted multiple aspects of postdischarge care, including medications and side effects, signs and symptoms to consider, plans for follow-up, dietary restrictions, and/or exercise modifications. Many (19 studies) provided education using one-on-one teaching in association with a discharge tool, accompanied by a written handout (13 studies), audiotape (2 studies), or video (3 studies). While 13 studies had patients involved in creating what content was discussed and 14 studies had patients involved in the delivery of the tool, only 6 studies had patients involved in both design and delivery of the tool. Nine studies also used visual aids such as pictures, larger font, or use of a tool enhanced for patients with language barriers or limited health literacy.

Among all 30 studies included, 16 studies tested the impact of their tool on comprehension postdischarge, with 10 studies demonstrating an improvement among patients who had received the tool (Table 2). Five studies evaluated healthcare utilization outcomes such as readmission, length of stay, or physician visits after discharge and 2 studies found improvements. Twelve studies also studied the impact on adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up instructions postdischarge. However, only 4 of these 12 studies showed a positive impact. Only 2 studies tested the impact on a patient’s ability to self-manage once at home, and both studies reported positive statistical outcomes. Few studies measured patient experience (such as patient satisfaction or improvement in self-efficacy) or mortality postdischarge.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

Our systematic review found 30 studies that engaged patients during the design or the delivery of a discharge instruction tool and that tested the effect of the tool on postdischarge outcomes.6-10,14–38 Our review suggests that there is sufficient evidence that patient-centered discharge tools improve comprehension. However, evidence is currently insufficient to determine if patient-centered tools improve adherence with discharge instructions. Moreover, though limited studies show promising results, more studies are needed to determine if patient engagement improves self-efficacy and healthcare utilization after discharge.

A major limitation of current studies is the variability in the level of patient engagement in tool design or delivery. Patients were involved in the design mostly through targeted development of a discharge management plan and the delivery by encouraging them to ask questions. Few studies involved patients in the design of the tool such that patients were responsible for coming up with content that was of interest to them. The few that did, often with the additional use of video media, demonstrated significant outcomes. Only a minority of studies used an interactive process to assess understanding such as “teach-back” or maximize patient comprehension such as visual aids. Even fewer studies engaged patients in both developing the discharge tool and providing discharge instructions.

Several previous studies have demonstrated that most complications after discharge are the result of ineffective communication, which can be exacerbated by lack of fluency in English or by limited health literacy.2,39-43 As a result, poor understanding of discharge instructions by patients and their caregivers can create an important care gap.44 Therefore, the use of patient-centered tools to engage patients at discharge in their own care is needed. How to engage patients consistently and effectively is perhaps less evident, as demonstrated in this review of the literature in which different levels of patient engagement were found. Many of the tools tested placed attention on patient education, sometimes in the context of bundled care along with home visits or follow-up, all of which can require extensive resources and time. Providing patients with information that the patients themselves state is of value may be the easiest refinement to a discharge educational tool, although this was surprisingly uncommon.6,9,10,17,23,33,37 Only 2 studies were found that engaged patients in the initial stage of design of the discharge tool, by incorporating information of interest to them.23,32 For example, a study testing the impact of a computer-generated written education package on poststroke outcomes designed the information by asking patients to identify which topics they would like to receive information about (along with the amount of information and font size).23 Secondly, although most of the discharge tools reviewed included the use of one-on-one teaching and the use of media such as patient handouts, these tools were often used in such a way that patients were passive recipients. In fact, studies that used additional video media that incorporated personalized content were the most likely to demonstrate positive outcomes.17,34 The next level of patient engagement may therefore be to involve the patient as an interactive partner when delivering the tool in order to empower patients to self-care. For example, 1 study designed a structured education program by first assessing lifestyle risk factors related to hypertension that were modifiable along with preconceived notions through open-ended questions during a one-on-one interview.37 Patients were subsequently educated on any knowledge deficits regarding the management of their lifestyle. Another level of patient engagement may be to use visual aids during discussions, as a well-known complement to verbal instructions.45,46 For example, in a controlled study that randomized a ward of elderly patients with 4 or more prescriptions to predischarge counseling, the counseling session aimed to review reasons for their prescriptions along with corresponding side effects, doses, and dosage times with the help of a medicine reminder card. Other uses of visual aid tools identified in our review included the use of pictograms or illustrations or, at minimum, attention to font size.7,8,16,29,33,35 In the absence of a visual aid, asking the patient to repeat or demonstrate what was just communicated can be used to assess the amount of information retained.18,33

An important result discovered in our review of the literature was also the lack of studies that tested the impact of discharge tools on usability of discharge information once at home. Conducting an evaluation of the benefits to patients after discharge can help objectify vague outcomes like health gains or qualify benefits in patient’s views. This might also explain why many studies with documented patient engagement at the time of discharge were able to demonstrate improvements in comprehension but not adherence to instructions. Although patients and caregivers may understand the information, this comprehension does not necessarily mean they will find the information useful or adhere to it once at home. For example, in 1 study, patients discharged with at least 1 medication were randomized to a structured discharge interview during which the treatment plan was reviewed verbally and questions clarified along with a visually enhanced treatment card.26 Although knowledge of medications increased, no effect was found on adherence at 1 week postdischarge. However, use of the treatment card at home was not assessed. Similarly, another study tested the effect of an individualized video of exercises and failed to find a difference in patient adherence at 4 weeks.28 The authors suggested that the lack of benefit may have been because patients were not using the video once at home. This is in contrast to 2 studies that involved patients in their own care by requiring them to request their medication as part of a self-medication tool predischarge.16,30 Patients were engaged in the process such that increasing independence was given to patients based on their demonstration of understanding and adherence to their treatment while still in the hospital, a learning tool that can be applied once at home. Feeling knowledgeable and involved, as others have suggested, may be the intermediary outcomes that led to improved adherence.47 It is also possible that adherence to discharge instructions may vary based on complexity of the information provided, such that instructions focusing solely on medication use may require less patient engagement than discharge instructions that include information on medications, diet, exercise modifications, and follow-up.48

Our review has a few limitations. Previous systematic reviews have demonstrated that bundled discharge interventions that include patient-centered education have a positive effect on outcomes postdischarge.2,5 However, we sought to describe and study the individual and distinct impact of patient engagement in the creation and delivery of discharge tools on outcomes postdischarge. We hoped that this may provide others with key information regarding elements of patient engagement that were particularly useful when designing a new discharge tool. The variability of the studies we identified, however, made it difficult to ascertain what level of patient engagement is required to observe improvements in health outcomes. It is also possible that a higher level of patient engagement may have been used but not described in the studies we reviewed. As only primary outcomes were included, we may have underestimated the effect of patient-centered discharge tools on outcomes that were reported as secondary outcomes. As we were interested in reviewing as many studies of patient-centered discharge tools as possible, we did not assess the quality of the studies and cannot comment on the role of bias in these studies. However, we excluded studies with study designs known to have the highest risk of bias. Lastly, we also cannot comment on whether patient-centered tools may have an effect on outcomes more than 3 months after a hospital discharge. However, several studies included in this review suggest a sustained effect beyond this time period.8,25,32,37

Patient-centered discharge tools in which patients were engaged in the design or the delivery were found to improve comprehension of but not adherence with discharge instructions. The perceived lack of improved adherence may be due to a lack of studies that measured the usefulness and utilization of information for patients once at home. There was also substantial variability in the extent of patient involvement in designing the style and content of information provided to patients at discharge, as well as the extent of patient engagement when receiving discharge instructions. Future studies would benefit from detailing the level of patient engagement needed in designing and delivery of discharge tools. This information may lead to the discovery of barriers and facilitators to utilization of discharge information once at home and lead to a better understanding of the patient’s journey from hospital to home and onwards.

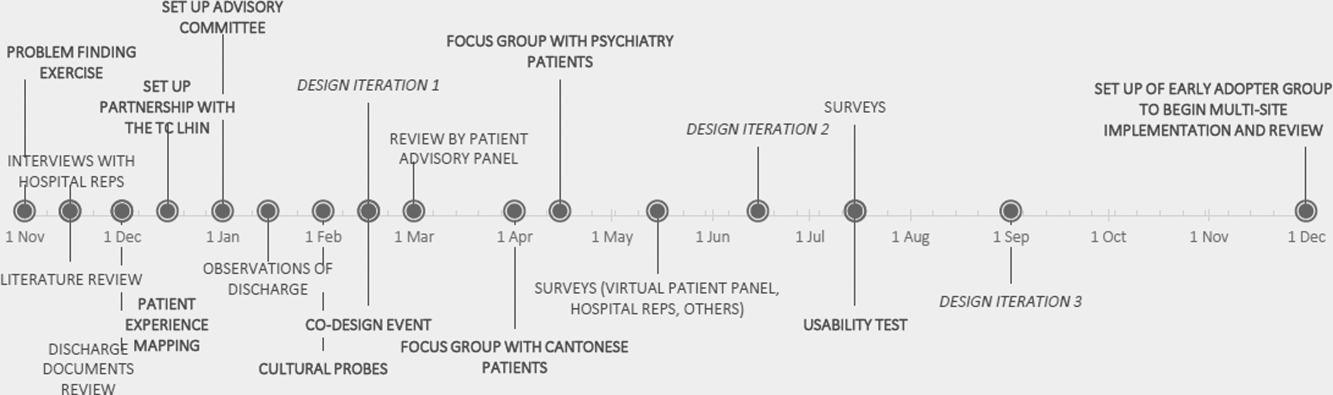

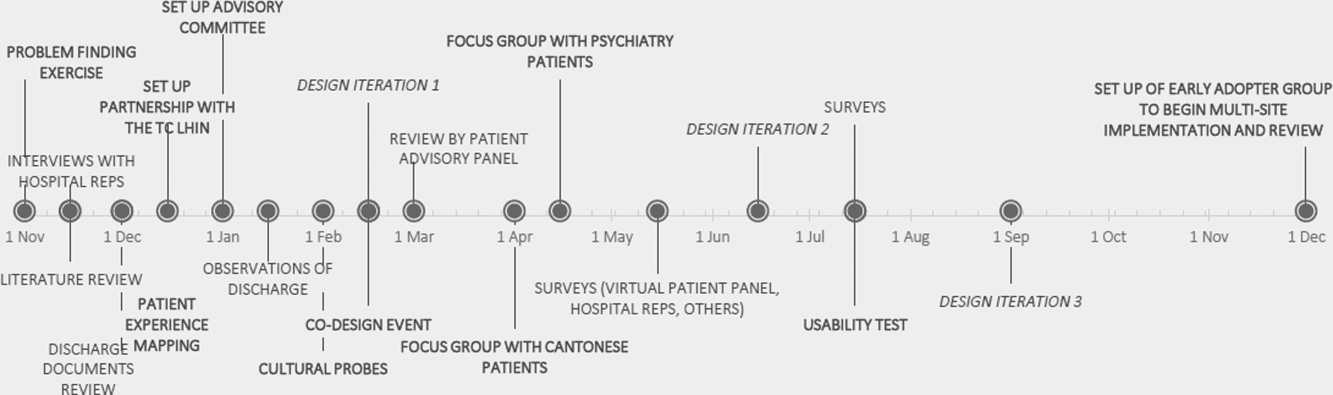

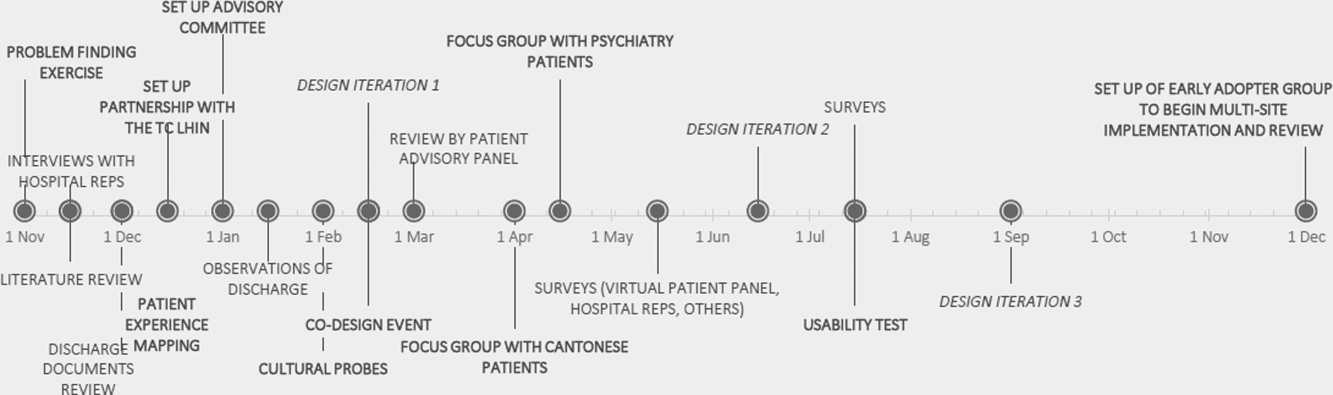

C.M.B. and this work were funded by a CIHR Canadian Patient Safety Institute Chair in Patient Safety and Continuity of Care. Funding was provided to cover fees to obtain articles from the Donald J. Matthews Complex Care Fund of the University Health Network in Toronto, Canada. The Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network provided funding for the design and implementation of a patient-oriented discharge summary. None of the funding or supportive agencies were involved in the design or conduct of the present study, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Hurtad

2. Mistiaen P, Francke AL, Poot E. Interventions aimed at reducing problems in adult patients discharged from hospital to home: a systematic meta-review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:47. PubMed

3. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822-1828. PubMed

4. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. PubMed

5. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. PubMed

6. Osman LM, Calder C, Godden DJ, et al. A randomised trial of self-management planning for adult patients admitted to hospital with acute asthma. Thorax. 2002;57(10):869-874. PubMed

7. Cordasco KM, Asch SM, Bell DS, et al. A low-literacy medication education tool for safety-net hospital patients. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6 suppl 1):S209-S216. PubMed

8. Morice AH, Wrench C. The role of the asthma nurse in treatment compliance and self-management following hospital admission. Resp Med. 2001;95(11):851-856. PubMed

9. Haerem JW, Ronning EJ, Leidal R. Home access to hospital discharge information on audiotape reduces sick leave and readmissions in patients with first-time myocardial infarction. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2000;34(2):219-222. PubMed

10. Legrain S, Tubach F, Bonnet-Zamponi D, et al. A new multimodal geriatric discharge-planning intervention to prevent emergency visits and rehospitalizations of older adults: the optimization of medication in AGEd multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2017-2028. PubMed

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-269. PubMed

12. Partnership NP. National Priorities and Goals: Aligning Our Efforts to Transform America’s Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2008.

13. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC-specific resources for review authors. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2013. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors. Accessed December 21, 2016.

14. Manning DM, O’Meara JG, Williams AR, et al. 3D: a tool for medication discharge education. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):71-76. PubMed

15. Perera KY, Ranasinghe P, Adikari AM, et al. Medium of language in discharge summaries: would the use of native language improve patients’ knowledge of their illness and medications? J Health Commun. 2012;17(2):141-148. PubMed

16. Lowe CJ, Raynor DK, Courtney EA, et al. Effects of self medication programme on knowledge of drugs and compliance with treatment in elderly patients. BMJ. 1995;310(6989):1229-1231. PubMed

17. Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Tarazi RY. Effects of a videotape information intervention at discharge on diet and exercise compliance after coronary bypass surgery. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1999;19(3):170-177. PubMed

18. Al-Rashed SA, Wright DJ, Roebuck N, et al. The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counseling to elderly patients prior to discharge. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(6):657-664. PubMed

19. Drenth-van Maanen AC, Wilting I, Jansen PA, et al. Effect of a discharge medication intervention on the incidence and nature of medication discrepancies in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):456-458. PubMed

20. Eshah NF. Predischarge education improves adherence to a healthy lifestyle among Jordanian patients with acute coronary syndrome. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):273-279. PubMed

21. Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Arnold JM, Zhang Y,et al. Pilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary educational intervention in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150(5):982. PubMed

22. Ho SM, Heh SS, Jevitt CM, et al. Effectiveness of a discharge education program in reducing the severity of postpartum depression: a randomized controlled evaluation study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(1):68-71. PubMed

23. Hoffmann T, McKenna K, Worrall L, et al. Randomised trial of a computer-generated tailored written education package for patients following stroke. Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):280-286. PubMed

24. Jenkins HM, Blank V, Miller K, et al. A randomized single-blind evaluation of a discharge teaching book for pediatric patients with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17(1):49-61. PubMed

25. Kommuri NV, Johnson ML, Koelling TM. Relationship between improvements in heart failure patient disease specific knowledge and clinical events as part of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(2):233-238. PubMed

26. Louis-Simonet M, Kossovsky MP, Sarasin FP, et al. Effects of a structured patient-centered discharge interview on patients’ knowledge about their medications. Am J Med. 2004;117(8):563-568. PubMed

27. Lucas KS. Outcomes evaluation of a pharmacist discharge medication teaching service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1998;55(24 suppl 4):S32-S35. PubMed

28. Lysack C, Dama M, Neufeld S, et al. A compliance and satisfaction with home exercise: a comparison of computer-assisted video instruction and routine rehabilitation practice. J Allied Health. 2005;34(2):76-82. PubMed

29. Moore SM. The effects of a discharge information intervention on recovery outcomes following coronary artery bypass surgery. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996;33(2):181-189. PubMed

30. Pereles L, Romonko L, Murzyn T, et al. Evaluation of a self-medication program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(2):161-165. PubMed

31. Reynolds MA. Postoperative pain management discharge teaching in a rural population. Pain Manag Nurs. 2009;10(2):76-84. PubMed

32. Sabariego C, Barrera AE, Neubert S, et al. Evaluation of an ICF-based patient education programme for stroke patients: a randomized, single-blinded, controlled, multicentre trial of the effects on self-efficacy, life satisfaction and functioning. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(4):707-728. PubMed

33. Shieh SJ, Chen HL, Liu FC, et al. The effectiveness of structured discharge education on maternal confidence, caring knowledge and growth of premature newborns. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(23-24):3307-3313. PubMed

34. Steinberg TG, Diercks MJ, Millspaugh J. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a videotape for discharge teaching of organ transplant recipients. J Transpl Coord. 1996;6(2):59-63. PubMed

35. Whitby M, McLaws ML, Doidge S, et al. Post-discharge surgical site surveillance: does patient education improve reliability of diagnosis? J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(3):237-242. PubMed

36. Williford SL, Johnson DF. Impact of pharmacist counseling on medication knowledge and compliance. Mil Med. 1995;160(11):561–564. PubMed

37. Zernike W, Henderson A. Evaluating the effectiveness of two teaching strategies for patients diagnosed with hypertension. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7(1):37–44. PubMed

38. Press VG, Arora V, Constantine KL, et al. Forget me not: a randomized trial of the durability of hospital-based education on inhalers for patients with COPD or asthma [abstract]. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1 suppl):S102.

39. Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887–894. PubMed

40. McCarthy DM, Waite KR, Curtis LM, et al. What did the doctor say? Health literacy and recall of medical instructions. Med Care. 2012;50(4):277–282. PubMed

41. Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, et al. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1855–1862. PubMed

42. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, et al. Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 3):312–324. PubMed

43. Karliner LS, Auerbach A, Nápoles A, et al. Language barriers and understanding of hospital discharge instructions. Med Care. 2012;50(4):283–289. PubMed

44. Enhancing the Continuum of Care. Report of the Avoidable Hospitalization Advisory Panel. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/baker_2011/baker_2011.pdf. Published November 2011. Accessed December 22, 2016.

45. Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, et al. Better transitions: improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Front Health Serv Manage. 2009;25(3):11–32. PubMed

46. Schillinger D, Machtinger EL, Wang F, et al. Language, literacy, and communication regarding medication in an anticoagulation clinic: a comparison of verbal vs. visual assessment. J Health Commun. 2006;11(7):651–664. PubMed

47. Epstein RM, Street RL, Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. PubMed

48. Albrecht JS, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hirshon JM, et al. Hospital discharge instructions: comprehension and compliance among older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1491–1498. PubMed

Patient-centered care, defined by the Institute of Medicine as “health care that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care,” has been recognized as an important factor in improving care transitions after discharge from the hospital.1 Previous efforts to improve the discharge process for hospitalized patients and reduce avoidable readmissions have focused on improving systems surrounding the patient, such as by increasing the availability of outpatient follow-up or standardizing communication between the inpatient and outpatient care teams.1,2 In fact, successful programs such as Project BOOST and the Care Transitions Interventions™ provide healthcare institutions with a “bundle” of evidence-based transitional care guidelines for discharge: they provide postdischarge transition coaches, assistance with medication self-management, timely follow-up tips, and improved patient records in order to improve postdischarge outcomes.3,4 Successful interventions, however, may not provide more services, but also engage the patient in their own care.5,6 The impact of engaging the patient in his or her own care by providing patient-friendly discharge instructions alone, however, is unknown.

A patient-centered discharge may use tools that were designed with patients, or may involve engaging patients in an interactive process of reviewing discharge instructions and empowering them to manage aspects of their own care after leaving the hospital. This endeavour may lead to more effective use of discharge instructions and reduce the need for additional or more intensive (and costly) interventions. For example, a patient-centered discharge tool could include an educational intervention that uses the “teach-back” method, in which patients are asked to restate in their own words what they thought they heard, or in which staff use additional media or a visual design tool meant to enhance comprehension of discharge instructions.6,7 Visual aids and the use of larger fonts are particularly useful design elements for improving comprehension among non-English speakers and patients with low health literacy, who tend to have poorer recall of instructions.8-10 What may constitute essential design elements to include in a discharge instruction tool, however, is not clear.

Moreover, whether the use of discharge tools with a specific focus on patient engagement may improve postdischarge outcomes is not known. Particularly, the ability of patient-centered discharge tools to improve outcomes beyond comprehension such as self-management, adherence to discharge instructions, a reduction in unplanned visits, and a reduction in mortality has not been studied systematically. The objective of this systematic review was to review the literature on discharge instruction tools with a focus on patient engagement and their impact among hospitalized patients.

METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Statement was followed as a guideline for reporting throughout this review.11

Data Sources

A literature search was undertaken using the following databases from January 1994 or their inception date to May 2014: Medline, Embase, SIGLE, HTA, Bioethics, ASSIA, Psych Lit, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EconLit, ERIC, and BioMed Central. We also searched relevant design-focused journals such as Design Issues, Journal of Design Research, Information Design Journal, Innovation, Design Studies, and International Journal of Design, as well as reference lists from studies obtained by electronic searching. The following key words and combination of key words were used with the assistance of a medical librarian: patient discharge, patient-centered discharge, patient-centered design, design thinking, user based design, patient education, discharge summary, education. Additional search terms were added when identified from relevant articles (Appendix).

Inclusion Criteria

We included all English-language studies with patients admitted to the hospital irrespective of age, sex, or medical condition, which included a control group or time period and which measured patient outcomes within 3 months of discharge. The 3-month period after discharge is often cited as a time when outcomes could reasonably be associated with an intervention at discharge.2

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that did not have clear implementation of a patient-centered tool, a control group, or those whose tool was used in the emergency department or as an outpatient were excluded. Studies that included postdischarge tools such as home visits or telephone calls were excluded unless independent effects of the predischarge interventions were measured. Studies with outcomes reported after 3 months were excluded unless outcomes before 3 months were also clearly noted.

All searches were entered into Endnote and duplicates were removed. A 2-stage inclusion process was used. Titles and abstracts of articles were first screened for meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria by 1 reviewer. A second reviewer independently checked a 10% random sample of all the abstracts that met the initial screening criteria. If the agreement to exclude studies was less than 95%, criteria were reviewed before checking the rest of the 90% sample. In the second stage, 2 independent reviewers examined paper copies of the full articles selected in the first stage. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion or a third reviewer if no agreement could be reached.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

The following information was extracted from the full reference: type of study, population studied, control group or time period, tool used, and outcomes measured. Based on the National Health Care Quality report’s priorities and goals on patient and/or family engagement during transitions of care, educational tools were further described based on method of teaching, involvement of the care team, involvement of the patient in the design or delivery of the tool, and/or the use of visual aids.12 All primary outcomes were classified according to 3 categories: improved knowledge/comprehension, patient experience (patient satisfaction, self-management/efficacy such as functional status, both physical and mental), and health outcomes (unscheduled visits or readmissions, adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up, and mortality).

No quantitative pooling of results or meta-analysis was done given the variability and heterogeneity of studies reviewed. However, following guidelines for Effect Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Risk of Bias criteria,13 studies that had a higher risk of bias such as uncontrolled before-after studies or studies with only 1 intervention or control site (historical controls, eg) were excluded from the final review because of the difficulties in attributing causation. Only primary outcomes were reported in order to minimize type II errors.

RESULTS

Our search revealed a total of 3699 studies after duplicates had been removed (Figure). A total of 714 references were included after initial review by title and abstract and 30 studies after full-text review. Agreement on a 10% random sample of all abstracts and full text was 79% (k=0.58) and 86% (k=0.72), respectively. Discussion was needed for fewer than 100 references, and agreement was subsequently reached for 100%.

There were 22 randomized controlled trials and 8 nonrandomized studies (5 nonrandomized controlled trials and 3 controlled before-after studies). Most of these studies were conducted in the United States (13/30 studies), followed by other European countries (5 studies), and the United Kingdom (4 studies). A large number of studies were conducted among patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors (10 studies), followed by postsurgical patients such as coronary artery bypass graft surgery or orthopaedic surgery (5 studies). Five of 30 studies were conducted among individuals older than 65 years. Most studies excluded patients who did not speak English or the country’s official language; only 3 studies included patients with limited literacy, patients who spoke other languages, or caregivers if the patients could not communicate.

Most studies tested the impact of educational discharge interventions (28 of 30 studies) (Table 1). Quite often, it was a member of the research team who carried out the patient education. Only 3 studies involved multiple members of the care team in designing or reviewing the discharge tool with the patient. Almost half (12 studies) targeted multiple aspects of postdischarge care, including medications and side effects, signs and symptoms to consider, plans for follow-up, dietary restrictions, and/or exercise modifications. Many (19 studies) provided education using one-on-one teaching in association with a discharge tool, accompanied by a written handout (13 studies), audiotape (2 studies), or video (3 studies). While 13 studies had patients involved in creating what content was discussed and 14 studies had patients involved in the delivery of the tool, only 6 studies had patients involved in both design and delivery of the tool. Nine studies also used visual aids such as pictures, larger font, or use of a tool enhanced for patients with language barriers or limited health literacy.

Among all 30 studies included, 16 studies tested the impact of their tool on comprehension postdischarge, with 10 studies demonstrating an improvement among patients who had received the tool (Table 2). Five studies evaluated healthcare utilization outcomes such as readmission, length of stay, or physician visits after discharge and 2 studies found improvements. Twelve studies also studied the impact on adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up instructions postdischarge. However, only 4 of these 12 studies showed a positive impact. Only 2 studies tested the impact on a patient’s ability to self-manage once at home, and both studies reported positive statistical outcomes. Few studies measured patient experience (such as patient satisfaction or improvement in self-efficacy) or mortality postdischarge.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

Our systematic review found 30 studies that engaged patients during the design or the delivery of a discharge instruction tool and that tested the effect of the tool on postdischarge outcomes.6-10,14–38 Our review suggests that there is sufficient evidence that patient-centered discharge tools improve comprehension. However, evidence is currently insufficient to determine if patient-centered tools improve adherence with discharge instructions. Moreover, though limited studies show promising results, more studies are needed to determine if patient engagement improves self-efficacy and healthcare utilization after discharge.

A major limitation of current studies is the variability in the level of patient engagement in tool design or delivery. Patients were involved in the design mostly through targeted development of a discharge management plan and the delivery by encouraging them to ask questions. Few studies involved patients in the design of the tool such that patients were responsible for coming up with content that was of interest to them. The few that did, often with the additional use of video media, demonstrated significant outcomes. Only a minority of studies used an interactive process to assess understanding such as “teach-back” or maximize patient comprehension such as visual aids. Even fewer studies engaged patients in both developing the discharge tool and providing discharge instructions.

Several previous studies have demonstrated that most complications after discharge are the result of ineffective communication, which can be exacerbated by lack of fluency in English or by limited health literacy.2,39-43 As a result, poor understanding of discharge instructions by patients and their caregivers can create an important care gap.44 Therefore, the use of patient-centered tools to engage patients at discharge in their own care is needed. How to engage patients consistently and effectively is perhaps less evident, as demonstrated in this review of the literature in which different levels of patient engagement were found. Many of the tools tested placed attention on patient education, sometimes in the context of bundled care along with home visits or follow-up, all of which can require extensive resources and time. Providing patients with information that the patients themselves state is of value may be the easiest refinement to a discharge educational tool, although this was surprisingly uncommon.6,9,10,17,23,33,37 Only 2 studies were found that engaged patients in the initial stage of design of the discharge tool, by incorporating information of interest to them.23,32 For example, a study testing the impact of a computer-generated written education package on poststroke outcomes designed the information by asking patients to identify which topics they would like to receive information about (along with the amount of information and font size).23 Secondly, although most of the discharge tools reviewed included the use of one-on-one teaching and the use of media such as patient handouts, these tools were often used in such a way that patients were passive recipients. In fact, studies that used additional video media that incorporated personalized content were the most likely to demonstrate positive outcomes.17,34 The next level of patient engagement may therefore be to involve the patient as an interactive partner when delivering the tool in order to empower patients to self-care. For example, 1 study designed a structured education program by first assessing lifestyle risk factors related to hypertension that were modifiable along with preconceived notions through open-ended questions during a one-on-one interview.37 Patients were subsequently educated on any knowledge deficits regarding the management of their lifestyle. Another level of patient engagement may be to use visual aids during discussions, as a well-known complement to verbal instructions.45,46 For example, in a controlled study that randomized a ward of elderly patients with 4 or more prescriptions to predischarge counseling, the counseling session aimed to review reasons for their prescriptions along with corresponding side effects, doses, and dosage times with the help of a medicine reminder card. Other uses of visual aid tools identified in our review included the use of pictograms or illustrations or, at minimum, attention to font size.7,8,16,29,33,35 In the absence of a visual aid, asking the patient to repeat or demonstrate what was just communicated can be used to assess the amount of information retained.18,33

An important result discovered in our review of the literature was also the lack of studies that tested the impact of discharge tools on usability of discharge information once at home. Conducting an evaluation of the benefits to patients after discharge can help objectify vague outcomes like health gains or qualify benefits in patient’s views. This might also explain why many studies with documented patient engagement at the time of discharge were able to demonstrate improvements in comprehension but not adherence to instructions. Although patients and caregivers may understand the information, this comprehension does not necessarily mean they will find the information useful or adhere to it once at home. For example, in 1 study, patients discharged with at least 1 medication were randomized to a structured discharge interview during which the treatment plan was reviewed verbally and questions clarified along with a visually enhanced treatment card.26 Although knowledge of medications increased, no effect was found on adherence at 1 week postdischarge. However, use of the treatment card at home was not assessed. Similarly, another study tested the effect of an individualized video of exercises and failed to find a difference in patient adherence at 4 weeks.28 The authors suggested that the lack of benefit may have been because patients were not using the video once at home. This is in contrast to 2 studies that involved patients in their own care by requiring them to request their medication as part of a self-medication tool predischarge.16,30 Patients were engaged in the process such that increasing independence was given to patients based on their demonstration of understanding and adherence to their treatment while still in the hospital, a learning tool that can be applied once at home. Feeling knowledgeable and involved, as others have suggested, may be the intermediary outcomes that led to improved adherence.47 It is also possible that adherence to discharge instructions may vary based on complexity of the information provided, such that instructions focusing solely on medication use may require less patient engagement than discharge instructions that include information on medications, diet, exercise modifications, and follow-up.48

Our review has a few limitations. Previous systematic reviews have demonstrated that bundled discharge interventions that include patient-centered education have a positive effect on outcomes postdischarge.2,5 However, we sought to describe and study the individual and distinct impact of patient engagement in the creation and delivery of discharge tools on outcomes postdischarge. We hoped that this may provide others with key information regarding elements of patient engagement that were particularly useful when designing a new discharge tool. The variability of the studies we identified, however, made it difficult to ascertain what level of patient engagement is required to observe improvements in health outcomes. It is also possible that a higher level of patient engagement may have been used but not described in the studies we reviewed. As only primary outcomes were included, we may have underestimated the effect of patient-centered discharge tools on outcomes that were reported as secondary outcomes. As we were interested in reviewing as many studies of patient-centered discharge tools as possible, we did not assess the quality of the studies and cannot comment on the role of bias in these studies. However, we excluded studies with study designs known to have the highest risk of bias. Lastly, we also cannot comment on whether patient-centered tools may have an effect on outcomes more than 3 months after a hospital discharge. However, several studies included in this review suggest a sustained effect beyond this time period.8,25,32,37

Patient-centered discharge tools in which patients were engaged in the design or the delivery were found to improve comprehension of but not adherence with discharge instructions. The perceived lack of improved adherence may be due to a lack of studies that measured the usefulness and utilization of information for patients once at home. There was also substantial variability in the extent of patient involvement in designing the style and content of information provided to patients at discharge, as well as the extent of patient engagement when receiving discharge instructions. Future studies would benefit from detailing the level of patient engagement needed in designing and delivery of discharge tools. This information may lead to the discovery of barriers and facilitators to utilization of discharge information once at home and lead to a better understanding of the patient’s journey from hospital to home and onwards.

C.M.B. and this work were funded by a CIHR Canadian Patient Safety Institute Chair in Patient Safety and Continuity of Care. Funding was provided to cover fees to obtain articles from the Donald J. Matthews Complex Care Fund of the University Health Network in Toronto, Canada. The Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network provided funding for the design and implementation of a patient-oriented discharge summary. None of the funding or supportive agencies were involved in the design or conduct of the present study, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Patient-centered care, defined by the Institute of Medicine as “health care that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care,” has been recognized as an important factor in improving care transitions after discharge from the hospital.1 Previous efforts to improve the discharge process for hospitalized patients and reduce avoidable readmissions have focused on improving systems surrounding the patient, such as by increasing the availability of outpatient follow-up or standardizing communication between the inpatient and outpatient care teams.1,2 In fact, successful programs such as Project BOOST and the Care Transitions Interventions™ provide healthcare institutions with a “bundle” of evidence-based transitional care guidelines for discharge: they provide postdischarge transition coaches, assistance with medication self-management, timely follow-up tips, and improved patient records in order to improve postdischarge outcomes.3,4 Successful interventions, however, may not provide more services, but also engage the patient in their own care.5,6 The impact of engaging the patient in his or her own care by providing patient-friendly discharge instructions alone, however, is unknown.

A patient-centered discharge may use tools that were designed with patients, or may involve engaging patients in an interactive process of reviewing discharge instructions and empowering them to manage aspects of their own care after leaving the hospital. This endeavour may lead to more effective use of discharge instructions and reduce the need for additional or more intensive (and costly) interventions. For example, a patient-centered discharge tool could include an educational intervention that uses the “teach-back” method, in which patients are asked to restate in their own words what they thought they heard, or in which staff use additional media or a visual design tool meant to enhance comprehension of discharge instructions.6,7 Visual aids and the use of larger fonts are particularly useful design elements for improving comprehension among non-English speakers and patients with low health literacy, who tend to have poorer recall of instructions.8-10 What may constitute essential design elements to include in a discharge instruction tool, however, is not clear.

Moreover, whether the use of discharge tools with a specific focus on patient engagement may improve postdischarge outcomes is not known. Particularly, the ability of patient-centered discharge tools to improve outcomes beyond comprehension such as self-management, adherence to discharge instructions, a reduction in unplanned visits, and a reduction in mortality has not been studied systematically. The objective of this systematic review was to review the literature on discharge instruction tools with a focus on patient engagement and their impact among hospitalized patients.

METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Statement was followed as a guideline for reporting throughout this review.11

Data Sources

A literature search was undertaken using the following databases from January 1994 or their inception date to May 2014: Medline, Embase, SIGLE, HTA, Bioethics, ASSIA, Psych Lit, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EconLit, ERIC, and BioMed Central. We also searched relevant design-focused journals such as Design Issues, Journal of Design Research, Information Design Journal, Innovation, Design Studies, and International Journal of Design, as well as reference lists from studies obtained by electronic searching. The following key words and combination of key words were used with the assistance of a medical librarian: patient discharge, patient-centered discharge, patient-centered design, design thinking, user based design, patient education, discharge summary, education. Additional search terms were added when identified from relevant articles (Appendix).

Inclusion Criteria

We included all English-language studies with patients admitted to the hospital irrespective of age, sex, or medical condition, which included a control group or time period and which measured patient outcomes within 3 months of discharge. The 3-month period after discharge is often cited as a time when outcomes could reasonably be associated with an intervention at discharge.2

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that did not have clear implementation of a patient-centered tool, a control group, or those whose tool was used in the emergency department or as an outpatient were excluded. Studies that included postdischarge tools such as home visits or telephone calls were excluded unless independent effects of the predischarge interventions were measured. Studies with outcomes reported after 3 months were excluded unless outcomes before 3 months were also clearly noted.

All searches were entered into Endnote and duplicates were removed. A 2-stage inclusion process was used. Titles and abstracts of articles were first screened for meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria by 1 reviewer. A second reviewer independently checked a 10% random sample of all the abstracts that met the initial screening criteria. If the agreement to exclude studies was less than 95%, criteria were reviewed before checking the rest of the 90% sample. In the second stage, 2 independent reviewers examined paper copies of the full articles selected in the first stage. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion or a third reviewer if no agreement could be reached.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

The following information was extracted from the full reference: type of study, population studied, control group or time period, tool used, and outcomes measured. Based on the National Health Care Quality report’s priorities and goals on patient and/or family engagement during transitions of care, educational tools were further described based on method of teaching, involvement of the care team, involvement of the patient in the design or delivery of the tool, and/or the use of visual aids.12 All primary outcomes were classified according to 3 categories: improved knowledge/comprehension, patient experience (patient satisfaction, self-management/efficacy such as functional status, both physical and mental), and health outcomes (unscheduled visits or readmissions, adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up, and mortality).

No quantitative pooling of results or meta-analysis was done given the variability and heterogeneity of studies reviewed. However, following guidelines for Effect Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Risk of Bias criteria,13 studies that had a higher risk of bias such as uncontrolled before-after studies or studies with only 1 intervention or control site (historical controls, eg) were excluded from the final review because of the difficulties in attributing causation. Only primary outcomes were reported in order to minimize type II errors.

RESULTS

Our search revealed a total of 3699 studies after duplicates had been removed (Figure). A total of 714 references were included after initial review by title and abstract and 30 studies after full-text review. Agreement on a 10% random sample of all abstracts and full text was 79% (k=0.58) and 86% (k=0.72), respectively. Discussion was needed for fewer than 100 references, and agreement was subsequently reached for 100%.

There were 22 randomized controlled trials and 8 nonrandomized studies (5 nonrandomized controlled trials and 3 controlled before-after studies). Most of these studies were conducted in the United States (13/30 studies), followed by other European countries (5 studies), and the United Kingdom (4 studies). A large number of studies were conducted among patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors (10 studies), followed by postsurgical patients such as coronary artery bypass graft surgery or orthopaedic surgery (5 studies). Five of 30 studies were conducted among individuals older than 65 years. Most studies excluded patients who did not speak English or the country’s official language; only 3 studies included patients with limited literacy, patients who spoke other languages, or caregivers if the patients could not communicate.

Most studies tested the impact of educational discharge interventions (28 of 30 studies) (Table 1). Quite often, it was a member of the research team who carried out the patient education. Only 3 studies involved multiple members of the care team in designing or reviewing the discharge tool with the patient. Almost half (12 studies) targeted multiple aspects of postdischarge care, including medications and side effects, signs and symptoms to consider, plans for follow-up, dietary restrictions, and/or exercise modifications. Many (19 studies) provided education using one-on-one teaching in association with a discharge tool, accompanied by a written handout (13 studies), audiotape (2 studies), or video (3 studies). While 13 studies had patients involved in creating what content was discussed and 14 studies had patients involved in the delivery of the tool, only 6 studies had patients involved in both design and delivery of the tool. Nine studies also used visual aids such as pictures, larger font, or use of a tool enhanced for patients with language barriers or limited health literacy.

Among all 30 studies included, 16 studies tested the impact of their tool on comprehension postdischarge, with 10 studies demonstrating an improvement among patients who had received the tool (Table 2). Five studies evaluated healthcare utilization outcomes such as readmission, length of stay, or physician visits after discharge and 2 studies found improvements. Twelve studies also studied the impact on adherence with medications, diet, exercise, or follow-up instructions postdischarge. However, only 4 of these 12 studies showed a positive impact. Only 2 studies tested the impact on a patient’s ability to self-manage once at home, and both studies reported positive statistical outcomes. Few studies measured patient experience (such as patient satisfaction or improvement in self-efficacy) or mortality postdischarge.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

Our systematic review found 30 studies that engaged patients during the design or the delivery of a discharge instruction tool and that tested the effect of the tool on postdischarge outcomes.6-10,14–38 Our review suggests that there is sufficient evidence that patient-centered discharge tools improve comprehension. However, evidence is currently insufficient to determine if patient-centered tools improve adherence with discharge instructions. Moreover, though limited studies show promising results, more studies are needed to determine if patient engagement improves self-efficacy and healthcare utilization after discharge.

A major limitation of current studies is the variability in the level of patient engagement in tool design or delivery. Patients were involved in the design mostly through targeted development of a discharge management plan and the delivery by encouraging them to ask questions. Few studies involved patients in the design of the tool such that patients were responsible for coming up with content that was of interest to them. The few that did, often with the additional use of video media, demonstrated significant outcomes. Only a minority of studies used an interactive process to assess understanding such as “teach-back” or maximize patient comprehension such as visual aids. Even fewer studies engaged patients in both developing the discharge tool and providing discharge instructions.

Several previous studies have demonstrated that most complications after discharge are the result of ineffective communication, which can be exacerbated by lack of fluency in English or by limited health literacy.2,39-43 As a result, poor understanding of discharge instructions by patients and their caregivers can create an important care gap.44 Therefore, the use of patient-centered tools to engage patients at discharge in their own care is needed. How to engage patients consistently and effectively is perhaps less evident, as demonstrated in this review of the literature in which different levels of patient engagement were found. Many of the tools tested placed attention on patient education, sometimes in the context of bundled care along with home visits or follow-up, all of which can require extensive resources and time. Providing patients with information that the patients themselves state is of value may be the easiest refinement to a discharge educational tool, although this was surprisingly uncommon.6,9,10,17,23,33,37 Only 2 studies were found that engaged patients in the initial stage of design of the discharge tool, by incorporating information of interest to them.23,32 For example, a study testing the impact of a computer-generated written education package on poststroke outcomes designed the information by asking patients to identify which topics they would like to receive information about (along with the amount of information and font size).23 Secondly, although most of the discharge tools reviewed included the use of one-on-one teaching and the use of media such as patient handouts, these tools were often used in such a way that patients were passive recipients. In fact, studies that used additional video media that incorporated personalized content were the most likely to demonstrate positive outcomes.17,34 The next level of patient engagement may therefore be to involve the patient as an interactive partner when delivering the tool in order to empower patients to self-care. For example, 1 study designed a structured education program by first assessing lifestyle risk factors related to hypertension that were modifiable along with preconceived notions through open-ended questions during a one-on-one interview.37 Patients were subsequently educated on any knowledge deficits regarding the management of their lifestyle. Another level of patient engagement may be to use visual aids during discussions, as a well-known complement to verbal instructions.45,46 For example, in a controlled study that randomized a ward of elderly patients with 4 or more prescriptions to predischarge counseling, the counseling session aimed to review reasons for their prescriptions along with corresponding side effects, doses, and dosage times with the help of a medicine reminder card. Other uses of visual aid tools identified in our review included the use of pictograms or illustrations or, at minimum, attention to font size.7,8,16,29,33,35 In the absence of a visual aid, asking the patient to repeat or demonstrate what was just communicated can be used to assess the amount of information retained.18,33

An important result discovered in our review of the literature was also the lack of studies that tested the impact of discharge tools on usability of discharge information once at home. Conducting an evaluation of the benefits to patients after discharge can help objectify vague outcomes like health gains or qualify benefits in patient’s views. This might also explain why many studies with documented patient engagement at the time of discharge were able to demonstrate improvements in comprehension but not adherence to instructions. Although patients and caregivers may understand the information, this comprehension does not necessarily mean they will find the information useful or adhere to it once at home. For example, in 1 study, patients discharged with at least 1 medication were randomized to a structured discharge interview during which the treatment plan was reviewed verbally and questions clarified along with a visually enhanced treatment card.26 Although knowledge of medications increased, no effect was found on adherence at 1 week postdischarge. However, use of the treatment card at home was not assessed. Similarly, another study tested the effect of an individualized video of exercises and failed to find a difference in patient adherence at 4 weeks.28 The authors suggested that the lack of benefit may have been because patients were not using the video once at home. This is in contrast to 2 studies that involved patients in their own care by requiring them to request their medication as part of a self-medication tool predischarge.16,30 Patients were engaged in the process such that increasing independence was given to patients based on their demonstration of understanding and adherence to their treatment while still in the hospital, a learning tool that can be applied once at home. Feeling knowledgeable and involved, as others have suggested, may be the intermediary outcomes that led to improved adherence.47 It is also possible that adherence to discharge instructions may vary based on complexity of the information provided, such that instructions focusing solely on medication use may require less patient engagement than discharge instructions that include information on medications, diet, exercise modifications, and follow-up.48

Our review has a few limitations. Previous systematic reviews have demonstrated that bundled discharge interventions that include patient-centered education have a positive effect on outcomes postdischarge.2,5 However, we sought to describe and study the individual and distinct impact of patient engagement in the creation and delivery of discharge tools on outcomes postdischarge. We hoped that this may provide others with key information regarding elements of patient engagement that were particularly useful when designing a new discharge tool. The variability of the studies we identified, however, made it difficult to ascertain what level of patient engagement is required to observe improvements in health outcomes. It is also possible that a higher level of patient engagement may have been used but not described in the studies we reviewed. As only primary outcomes were included, we may have underestimated the effect of patient-centered discharge tools on outcomes that were reported as secondary outcomes. As we were interested in reviewing as many studies of patient-centered discharge tools as possible, we did not assess the quality of the studies and cannot comment on the role of bias in these studies. However, we excluded studies with study designs known to have the highest risk of bias. Lastly, we also cannot comment on whether patient-centered tools may have an effect on outcomes more than 3 months after a hospital discharge. However, several studies included in this review suggest a sustained effect beyond this time period.8,25,32,37

Patient-centered discharge tools in which patients were engaged in the design or the delivery were found to improve comprehension of but not adherence with discharge instructions. The perceived lack of improved adherence may be due to a lack of studies that measured the usefulness and utilization of information for patients once at home. There was also substantial variability in the extent of patient involvement in designing the style and content of information provided to patients at discharge, as well as the extent of patient engagement when receiving discharge instructions. Future studies would benefit from detailing the level of patient engagement needed in designing and delivery of discharge tools. This information may lead to the discovery of barriers and facilitators to utilization of discharge information once at home and lead to a better understanding of the patient’s journey from hospital to home and onwards.

C.M.B. and this work were funded by a CIHR Canadian Patient Safety Institute Chair in Patient Safety and Continuity of Care. Funding was provided to cover fees to obtain articles from the Donald J. Matthews Complex Care Fund of the University Health Network in Toronto, Canada. The Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network provided funding for the design and implementation of a patient-oriented discharge summary. None of the funding or supportive agencies were involved in the design or conduct of the present study, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Hurtad

2. Mistiaen P, Francke AL, Poot E. Interventions aimed at reducing problems in adult patients discharged from hospital to home: a systematic meta-review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:47. PubMed

3. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822-1828. PubMed

4. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. PubMed

5. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. PubMed

6. Osman LM, Calder C, Godden DJ, et al. A randomised trial of self-management planning for adult patients admitted to hospital with acute asthma. Thorax. 2002;57(10):869-874. PubMed

7. Cordasco KM, Asch SM, Bell DS, et al. A low-literacy medication education tool for safety-net hospital patients. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6 suppl 1):S209-S216. PubMed

8. Morice AH, Wrench C. The role of the asthma nurse in treatment compliance and self-management following hospital admission. Resp Med. 2001;95(11):851-856. PubMed

9. Haerem JW, Ronning EJ, Leidal R. Home access to hospital discharge information on audiotape reduces sick leave and readmissions in patients with first-time myocardial infarction. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2000;34(2):219-222. PubMed

10. Legrain S, Tubach F, Bonnet-Zamponi D, et al. A new multimodal geriatric discharge-planning intervention to prevent emergency visits and rehospitalizations of older adults: the optimization of medication in AGEd multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2017-2028. PubMed

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-269. PubMed

12. Partnership NP. National Priorities and Goals: Aligning Our Efforts to Transform America’s Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2008.

13. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC-specific resources for review authors. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2013. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors. Accessed December 21, 2016.

14. Manning DM, O’Meara JG, Williams AR, et al. 3D: a tool for medication discharge education. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):71-76. PubMed

15. Perera KY, Ranasinghe P, Adikari AM, et al. Medium of language in discharge summaries: would the use of native language improve patients’ knowledge of their illness and medications? J Health Commun. 2012;17(2):141-148. PubMed

16. Lowe CJ, Raynor DK, Courtney EA, et al. Effects of self medication programme on knowledge of drugs and compliance with treatment in elderly patients. BMJ. 1995;310(6989):1229-1231. PubMed

17. Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Tarazi RY. Effects of a videotape information intervention at discharge on diet and exercise compliance after coronary bypass surgery. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1999;19(3):170-177. PubMed

18. Al-Rashed SA, Wright DJ, Roebuck N, et al. The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counseling to elderly patients prior to discharge. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(6):657-664. PubMed

19. Drenth-van Maanen AC, Wilting I, Jansen PA, et al. Effect of a discharge medication intervention on the incidence and nature of medication discrepancies in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):456-458. PubMed

20. Eshah NF. Predischarge education improves adherence to a healthy lifestyle among Jordanian patients with acute coronary syndrome. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):273-279. PubMed

21. Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Arnold JM, Zhang Y,et al. Pilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary educational intervention in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150(5):982. PubMed

22. Ho SM, Heh SS, Jevitt CM, et al. Effectiveness of a discharge education program in reducing the severity of postpartum depression: a randomized controlled evaluation study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(1):68-71. PubMed

23. Hoffmann T, McKenna K, Worrall L, et al. Randomised trial of a computer-generated tailored written education package for patients following stroke. Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):280-286. PubMed

24. Jenkins HM, Blank V, Miller K, et al. A randomized single-blind evaluation of a discharge teaching book for pediatric patients with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17(1):49-61. PubMed

25. Kommuri NV, Johnson ML, Koelling TM. Relationship between improvements in heart failure patient disease specific knowledge and clinical events as part of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(2):233-238. PubMed

26. Louis-Simonet M, Kossovsky MP, Sarasin FP, et al. Effects of a structured patient-centered discharge interview on patients’ knowledge about their medications. Am J Med. 2004;117(8):563-568. PubMed

27. Lucas KS. Outcomes evaluation of a pharmacist discharge medication teaching service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1998;55(24 suppl 4):S32-S35. PubMed

28. Lysack C, Dama M, Neufeld S, et al. A compliance and satisfaction with home exercise: a comparison of computer-assisted video instruction and routine rehabilitation practice. J Allied Health. 2005;34(2):76-82. PubMed

29. Moore SM. The effects of a discharge information intervention on recovery outcomes following coronary artery bypass surgery. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996;33(2):181-189. PubMed

30. Pereles L, Romonko L, Murzyn T, et al. Evaluation of a self-medication program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(2):161-165. PubMed

31. Reynolds MA. Postoperative pain management discharge teaching in a rural population. Pain Manag Nurs. 2009;10(2):76-84. PubMed

32. Sabariego C, Barrera AE, Neubert S, et al. Evaluation of an ICF-based patient education programme for stroke patients: a randomized, single-blinded, controlled, multicentre trial of the effects on self-efficacy, life satisfaction and functioning. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(4):707-728. PubMed

33. Shieh SJ, Chen HL, Liu FC, et al. The effectiveness of structured discharge education on maternal confidence, caring knowledge and growth of premature newborns. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(23-24):3307-3313. PubMed

34. Steinberg TG, Diercks MJ, Millspaugh J. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a videotape for discharge teaching of organ transplant recipients. J Transpl Coord. 1996;6(2):59-63. PubMed

35. Whitby M, McLaws ML, Doidge S, et al. Post-discharge surgical site surveillance: does patient education improve reliability of diagnosis? J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(3):237-242. PubMed

36. Williford SL, Johnson DF. Impact of pharmacist counseling on medication knowledge and compliance. Mil Med. 1995;160(11):561–564. PubMed

37. Zernike W, Henderson A. Evaluating the effectiveness of two teaching strategies for patients diagnosed with hypertension. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7(1):37–44. PubMed

38. Press VG, Arora V, Constantine KL, et al. Forget me not: a randomized trial of the durability of hospital-based education on inhalers for patients with COPD or asthma [abstract]. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1 suppl):S102.

39. Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887–894. PubMed

40. McCarthy DM, Waite KR, Curtis LM, et al. What did the doctor say? Health literacy and recall of medical instructions. Med Care. 2012;50(4):277–282. PubMed

41. Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, et al. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1855–1862. PubMed

42. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, et al. Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 3):312–324. PubMed

43. Karliner LS, Auerbach A, Nápoles A, et al. Language barriers and understanding of hospital discharge instructions. Med Care. 2012;50(4):283–289. PubMed

44. Enhancing the Continuum of Care. Report of the Avoidable Hospitalization Advisory Panel. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/baker_2011/baker_2011.pdf. Published November 2011. Accessed December 22, 2016.

45. Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, et al. Better transitions: improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Front Health Serv Manage. 2009;25(3):11–32. PubMed

46. Schillinger D, Machtinger EL, Wang F, et al. Language, literacy, and communication regarding medication in an anticoagulation clinic: a comparison of verbal vs. visual assessment. J Health Commun. 2006;11(7):651–664. PubMed

47. Epstein RM, Street RL, Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. PubMed

48. Albrecht JS, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hirshon JM, et al. Hospital discharge instructions: comprehension and compliance among older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1491–1498. PubMed

1. Hurtad