User login

Numeracy, Health Literacy, Cognition, and 30-Day Readmissions among Patients with Heart Failure

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

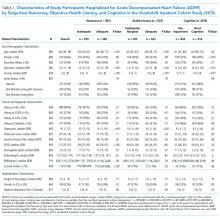

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Discharge Preparedness and Readmission

In recent years, US hospitals have focused on decreasing readmission rates, incented by reimbursement penalties to hospitals having excessive readmissions.[1] Gaps in the quality of care provided during transitions likely contribute to preventable readmissions.[2] One compelling quality assessment in this setting is measuring patients' discharge preparedness, using key dimensions such as understanding their instructions for medication use and follow‐up. Patient‐reported preparedness for discharge may also be useful to identify risk of readmission.

Several patient‐reported measures of preparedness for discharge exist, and herein we describe 2 measures of interest. First, the Brief‐PREPARED (B‐PREPARED) measure was derived from the longer PREPARED instrument (Prescriptions, Ready to re‐enter community, Education, Placement, Assurance of safety, Realistic expectations, Empowerment, Directed to appropriate services), which reflects the patient's perceived needs at discharge. In previous research, the B‐PREPARED measure predicted emergency department (ED) visits for patients who had been recently hospitalized and had a high risk for readmission.[3] Second, the Care Transitions Measure‐3 (CTM‐3) was developed by Coleman et al. as a patient‐reported measure to discriminate between patients who were more likely to have an ED visit or readmission from those who did not. CTM‐3 has also been used to evaluate hospitals' level of care coordination and for public reporting purposes.[4, 5, 6] It has been endorsed by the National Quality Forum and incorporated into the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey provided to samples of recently hospitalized US patients.[7] However, recent evidence from an inpatient cohort of cardiovascular patients suggests the CTM‐3 overinflates care transition scores compared to the longer 15‐item CTM. In that cohort, the CTM‐3 could not differentiate between patients who did or did not have repeat ED visits or readmission.[8] Thus far, the B‐PREPARED and CTM‐3 measures have not been compared to one another directly.

In addition to the development of patient‐reported measures, hospitals increasingly employ administrative algorithms to predict likelihood of readmission.[9] A commonly used measure is the LACE index (Length of stay, Acuity, Comorbidity, and Emergency department use).[10] The LACE index predicted readmission and death within 30 days of discharge in a large cohort in Canada. In 2 retrospective studies of recently hospitalized patients in the United States, the LACE index's ability to discriminate between patients readmitted or not ranged from slightly better than chance to moderate (C statistic 0.56‐0.77).[11, 12]

It is unknown whether adding patient‐reported preparedness measures to commonly used readmission prediction scores increases the ability to predict readmission risk. We sought to determine whether the B‐PREPARED and CTM‐3 measures were predictive of readmission or death, as compared to the LACE index, in a large cohort of cardiovascular patients. In addition, we sought to determine the additional predictive and discriminative ability gained from administering the B‐PREPARED and CTM‐3 measures, while adjusting for the LACE index and other clinical factors. We hypothesized that: (1) higher preparedness scores on both measures would predict lower risk of readmission or death in a cohort of patients hospitalized with cardiac diagnoses; and (2) because it provides more specific and actionable information, the B‐PREPARED would discriminate readmission more accurately than CTM‐3, after controlling for clinical factors.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Hospital. The purpose of VICS is to investigate the impact of patient and social factors on postdischarge health outcomes such as quality of life, unplanned hospital utilization, and mortality. The rationale and design of VICS are detailed elsewhere.[13] Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow‐up phone calls were conducted within 2 to 9 days and at approximately 30 and 90 days postdischarge. During the first follow‐up call conducted by research assistants, we collected preparedness for discharge data utilizing the 2 measures described below. After the 90‐day phone call, we collected healthcare utilization since the index admission. The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

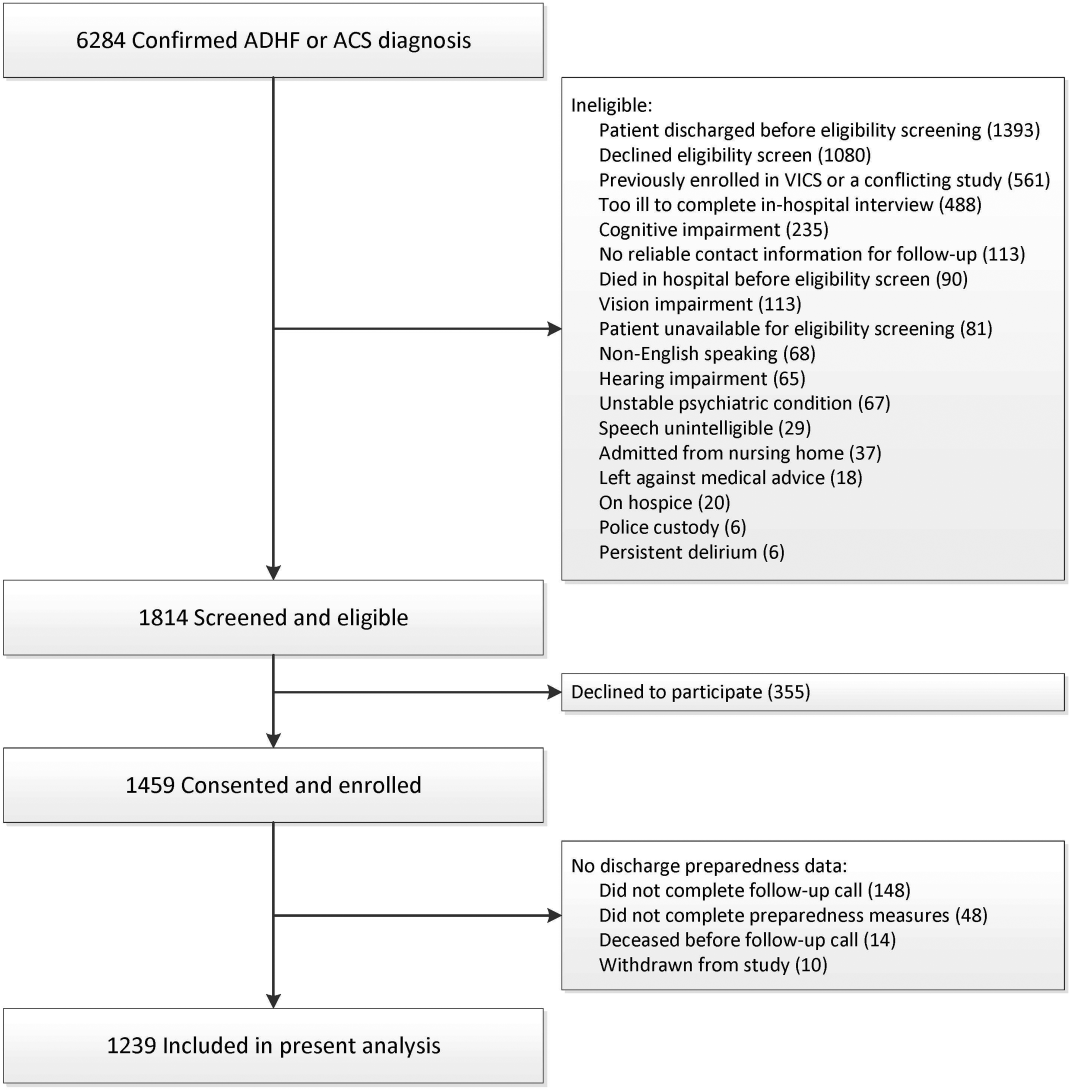

Patients

Eligibility screening shortly after admission identified patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) and/or an intermediate or high likelihood of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) per a physician's review of the clinical record. Exclusion criteria included: age <18 years, non‐English speaker, unstable psychiatric illness, delirium, low likelihood of follow‐up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. To be included in these analyses, patients must have completed the preparedness for discharge measurements during the first follow‐up call. Patients who died before discharge or before completing the follow‐up call were excluded.

Preparedness for Discharge Measures (Patient‐Reported Data)

Preparedness for discharge was assessed using the 11‐item B‐PREPARED and the 3‐item CTM‐3.

The B‐PREPARED measures how prepared patients felt leaving the hospital with regard to: self‐care information for medications and activity, equipment/community services needed, and confidence in managing one's health after hospitalization. The B‐PREPARED measure has good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's = 0.76) and has been validated in patients of varying age within a week of discharge. Preparedness is the sum of responses to all 11 questions, with a range of 0 to 22. Higher scores reflect increased preparedness for discharge.[3]

The CTM‐3 asks patients to rate how well their preferences were considered regarding transitional needs, as well as their understanding of postdischarge self‐management and the purpose of their medications, each on a 4‐point response scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). The sum of the 3 responses quantifies the patient's perception of the quality of the care transition at discharge (Cronbach's = 0.86,[14] 0.92 in a cohort similar to ours[8]). Scores range from 3 to 12, with higher score indicating more preparedness. Then, the sum is transformed to a 0 to 100 scale.[15]

Clinical Readmission Risk Measures (Medical Record Data)

The LACE index, published by Van Walraven et al.,[10] takes into account 4 categories of clinical data: length of hospital stay, acuity of event, comorbidities, and ED visits in the prior 6 months. More specifically, a diagnostic code‐based, modified version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index was used to calculate the comorbidity score. These clinical criteria were obtained from an administrative database and weighted according to the methods used by Van Walraven et al. An overall score was calculated on a scale of 0 to 19, with higher scores indicating higher risk of readmission or death within 30 days.

From medical records, we also collected patients' demographic data including age, race, and gender, and diagnosis of ACS, ADHF, or both at hospital admission.

Outcome Measures

Healthcare utilization data were obtained from the index hospital as well as outside facilities. The electronic medical records from Vanderbilt University Hospital provided information about healthcare utilization at Vanderbilt 90 days after initial discharge. We also used Vanderbilt records to see if patients were transferred to Vanderbilt from other hospitals or if patients visited other hospitals before or after enrollment. We supplemented this with patient self‐report during the follow‐up telephone calls (at 30 and 90 days after initial discharge) so that any additional ED and hospital visits could be captured. Mortality data were collected from medical records, Social Security data, and family reports. The main outcome was time to first unplanned hospital readmission or death within 30 and 90 days of discharge.

Analysis

To describe our sample, we summarized categorical variables with percentages and continuous variables with percentiles. To test for evidence of unadjusted covariate‐outcome relationships, we used Pearson 2 and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for categorical and continuous covariates, respectively.

For the primary analyses we used Cox proportional hazard models to examine the independent associations between the prespecified predictors for patient‐reported preparedness and time to first unplanned readmission or death within 30 and 90 days of discharge. For each outcome (30‐ and 90‐day readmission or death), we fit marginal models separately for each of the B‐PREPARED, CTM‐3, and LACE scores. We then fit multivariable models that used both preparedness measures as well as age, gender, race, and diagnosis (ADHF and/or ACS), variables available to clinicians when patients are admitted. When fitting the multivariable models, we did not find strong evidence of nonlinear effects; therefore, only linear effects are reported. To facilitate comparison of effects, we scaled continuous variables by their interquartile range (IQR). The associated, exponentiated regression parameter estimates may therefore be interpreted as hazard ratios for readmission or death per IQR change in each predictor. In addition to parameter estimation, we computed the C index to evaluate capacity for the model to discriminate those who were and were not readmitted or died. All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

From the cohort of 1239 patients (Figure 1), 64%, 28%, and 7% of patients were hospitalized with ACS, ADHF, or both, respectively (Table 1). Nearly 45% of patients were female, 83% were white, and the median age was 61 years (IQR 5269). The median length of stay was 3 days (IQR 25). The median preparedness scores were high for both B‐PREPARED (21, IQR 1822) and CTM‐3 (77.8, IQR 66.7100). A total of 211 (17%) and 380 (31%) were readmitted or died within 30 and 90 days, respectively. The completion rate for the postdischarge phone calls was 88%.

| Death or Readmission Within 30 Days | Death or Readmission Within 90 Days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Readmitted, N = 1028 | Death/Readmitted, N = 211 | P Value | Not Readmitted, N = 859 | Death/Readmitted, N = 380 | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Gender, male | 55.8% (574) | 53.1% (112) | 0.463* | 56.3% (484) | 53.2% (202) | 0.298* |

| Female | 44.2% (454) | 46.9% (99) | 43.7% (375) | 46.8% (178) | ||

| Race, white | 83.9% (860) | 80.6% (170) | 0.237* | 86.0% (737) | 77.3% (293) | <0.001* |

| Race, nonwhite | 16.1% (165) | 19.4% (41) | 14.0% (120) | 22.7% (86) | ||

| Diagnosis ACS | 68.0% (699) | 46.4% (98) | <0.001* | 72.9% (626) | 45.0% (171) | <0.001* |

| ADHF | 24.8% (255) | 46.0% (97) | 20.3% (174) | 46.8% (178) | ||

| Both | 7.2% (74) | 7.6% (16) | 6.9% (59) | 8.2% (31) | ||

| Age | 39.4:52:61:68:80 | 37.5:53.5:62:70:82 | 0.301 | 40:52:61:68:80 | 38:52:61 :70:82 | 0.651 |

| LOS | 1:2:3:5:10 | 1:3: 4:7.5:17 | <0.001 | 1:2:3:5:9 | 1:3:4:7:15 | <0.001 |

| CTM‐3 | 55.6:66.7: 77.8:100:100 | 55.6:66.7:77.8:100 :100 | 0.305 | 55.6:66.7:88.9:100:100 | 55.6:66.7:77.8:100 :100 | 0.080 |

| B‐PREPARED | 12:18:21:22.:22 | 10:17:20:22:22 | 0.066 | 12:18:21:22:22 | 10:17:20 :22:22 | 0.030 |

| LACE | 1:4: 7:10 :14 | 3.5:7:10:13:17 | <0.001 | 1:4:6: 9:14 | 3:7:10:13:16 | <0.001 |

B‐PREPARED and CTM‐3 were moderately correlated with one another (Spearman's = 0.40, P < 0.001). In bivariate analyses (Table 1), the association between B‐PREPARED and readmission or death was significant at 90 days (P = 0.030) but not 30 days. The CTM‐3 showed no significant association with readmission or death at either time point. The LACE score was significantly associated with rates of readmission at 30 and 90 days (P < 0.001).

Outcomes Within 30 Days of Discharge

When examining readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, simple unadjusted models 2 and 3 showed that the B‐PREPARED and LACE scores, respectively, were each significantly associated with time to first readmission or death (Table 2). Specifically, a 4‐point increase in the B‐PREPARED score was associated with a 16% decrease in the hazard of readmission or death (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.84, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.72 to 0.97). A 5‐point increase in the LACE score was associated with a 100% increase in the hazard of readmission or death (HR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.72 to 2.32). In the multivariable model with both preparedness scores and diagnosis (model 4), the B‐PREPARED score (HR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.70 to 0.97) was significantly associated with time to first readmission or death. In the full 30‐day model including B‐PREPARED, CTM‐3, LACE, age, gender, race, and diagnosis (model 5), only the LACE score (HR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.54 to 2.18) was independently associated with time to readmission or death. Finally, the CTM‐3 did not predict 30‐day readmission or death in any of the models tested.

| Models | HR (95% CI)* | P Value | C Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 1. CTM (per 10‐point change) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 0.257 | 0.523 |

| 2. B‐PREPARED (per 4‐point change) | 0.84 (0.72 to 0.97) | 0.017 | 0.537 |

| 3. LACE (per 5‐point change) | 2.00 (1.72 to 2.32) | <0.001 | 0.679 |

| 4. CTM (per 10‐point change) | 1.00 (0.92 to 1.10) | 0.935 | 0.620 |

| B‐PREPARED (per 4‐point change) | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.97) | 0.019 | |

| ADHF only (vs ACS only) | 2.46 (1.86 to 3.26) | <0.001 | |

| ADHF and ACS (vs ACS only) | 1.42 (0.84 to 2.42) | 0.191 | |

| 5. CTM (per 10‐point change) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.11) | 0.722 | 0.692 |

| B‐PREPARED (per 4 point change) | 0.87 (0.74 to 1.03) | 0.106 | |

| LACE (per 5‐point change) | 1.83 (1.54 to 2.18) | <0.001 | |

| ADHF only (vs ACS only) | 1.51 (1.10 to 2.08) | 0.010 | |

| ADHF and ACS (vs ACS only) | 0.90 (0.52 to 1.55) | 0.690 | |

| Age (per 10‐year change) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.14) | 0.669 | |

| Female (vs male) | 1.11 (0.85 to 1.46) | 0.438 | |

| Nonwhite (vs white) | 0.92 (0.64 to 1.30) | 0.624 | |

Outcomes Within 90 Days of Discharge

At 90 days after discharge, again the separate unadjusted models 2 and 3 demonstrated that the B‐PREPARED and LACE scores, respectively, were each significantly associated with time to first readmission or death, whereas the CTM‐3 model only showed marginal significance (Table 3). In the multivariable model with both preparedness scores and diagnosis (model 4), results were similar to 30 days as the B‐PREPARED score was significantly associated with time to first readmission or death. Lastly, in the full model (model 5) at 90 days, again the LACE score was significantly associated with time to first readmission or death. In addition, B‐PREPARED scores were associated with a significant decrease in risk of readmission or death (HR = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.78 to 1.00); CTM‐3 scores were not independently associated with outcomes.

| Model | HR (95% CI)* | P Value | C Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 1. CTM (per 10‐point change) | 0.94 (0.89 to 1.00) | 0.051 | 0.526 |

| 2. B‐PREPARED (per 4‐point change) | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.94) | 0.002 | 0.533 |

| 3. LACE (per 5‐point change) | 2.03 (1.82 to 2.27) | <0.001 | 0.683 |

| 4. CTM (per 10‐point change) | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 0.759 | 0.640 |

| B‐PREPARED (per 4‐point change) | 0.83 (0.74 to 0.94) | 0.003 | |

| ADHF only (vs ACS only) | 2.88 (2.33 to 3.56) | <0.001 | |

| ADHF and ACS (vs ACS only) | 1.62 (1.11 to 2.38) | 0.013 | |

| 5. CTM (per 10‐point change) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) | 0.932 | 0.698 |

| B‐PREPARED (per 4‐point change) | 0.88 (0.78 to 1.00) | 0.043 | |

| LACE (per 5‐point change) | 1.76 (1.55 to 2.00) | <0.001 | |

| ADHF only (vs ACS only) | 1.76 (1.39 to 2.24) | <0.001 | |

| ADHF and ACS (vs ACS only) | 1.00 (0.67 to 1.50) | 0.980 | |

| Age (per 10‐year change) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.09) | 0.894 | |

| Female (vs male) | 1.10 (0.90 to 1.35) | 0.341 | |

| Nonwhite (vs white) | 1.14 (0.89 to 1.47) | 0.288 | |

Tables 2 and 3 also display the C indices, or the discriminative ability of the models to differentiate whether or not a patient was readmitted or died. The range of the C index is 0.5 to 1, where values closer to 0.5 indicate random predictions and values closer to 1 indicate perfect prediction. At 30 days, the individual C indices for B‐PREPARED and CTM‐3 were only slightly better than chance (0.54 and 0.52, respectively) in their discriminative abilities. However, the C indices for the LACE score alone (0.68) and the multivariable model (0.69) including all 3 measures (ie, B‐PREPARED, CTM‐3, LACE), and clinical and demographic variables, had higher utility in discriminating patients who were readmitted/died or not. The 90‐day C indices were comparable in magnitude to those at 30 days.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

In this cohort of patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disease, we compared 2 patient‐reported measures of preparedness for discharge, their association with time to death or readmission at 30 and 90 days, and their ability to discriminate patients who were or were not readmitted or died. Higher preparedness as measured by higher B‐PREPARED scores was associated with lower risk of readmission or death at 30 and 90 days after discharge in unadjusted models, and at 90 days in adjusted models. CTM‐3 was not associated with the outcome in any analyses. Lastly, the individual preparedness measures were not as strongly associated with readmission or death compared to the LACE readmission index alone.

How do our findings relate to the measurement of care transition quality? We consider 2 scenarios. First, if hospitals utilize the LACE index to predict readmission, then neither self‐reported measure of preparedness adds meaningfully to its predictive ability. However, hospital management may still find the B‐PREPARED and CTM‐3 useful as a means to direct care transition quality‐improvement efforts. These measures can instruct hospitals as to what areas their patients express the greatest difficulty or lack of preparedness and closely attend to patient needs with appropriate resources. Furthermore, the patient's perception of being prepared for discharge may be different than their actual preparedness. Their perceived preparedness may be affected by cognitive impairment, dissatisfaction with medical care, depression, lower health‐related quality of life, and lower educational attainment as demonstrated by Lau et al.[16] If a patient's perception of preparedness were low, it would behoove the clinician to investigate these other issues and address those that are mutable. Additionally, perceived preparedness may not correlate with the patient's understanding of their medical conditions, so it is imperative that clinicians provide prospective guidance about their probable postdischarge trajectory. If hospitals are not utilizing the LACE index, then perhaps using the B‐PREPARED, but not the CTM‐3, may be beneficial for predicting readmission.

How do our results fit with evidence from prior studies, and what do they mean in the context of care transitions quality? First, in the psychometric evaluation of the B‐PREPARED measure in a cohort of recently hospitalized patients, the mean score was 17.3, lower than the median of 21 in our cohort.[3] Numerous studies have utilized the CTM‐3 and the longer‐version CTM‐15. Though we cannot make a direct comparison, the median in our cohort (77.8) was on par with the means from other studies, which ranged from 63 to 82.[5, 17, 18, 19] Several studies also note ceiling effects with clusters of scores at the upper end of the scale, as did we. We conjecture that our cohort's preparedness scores may be higher because our institution has made concerted efforts to improve the discharge education for cardiovascular patients.

In a comparable patient population, the TRACE‐CORE (Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education) study is a cohort of more than 2200 patients with ACS who were administered the CTM‐15 within 1 month of discharge.[8] In that study, the median CTM‐15 score was 66.6, which is lower than our cohort. With regard to the predictive ability of the CTM‐3, they note that CTM‐3 scores did not differentiate between patients who were or were not readmitted or had emergency department visits. Our results support their concern that the CTM‐15 and by extension the CTM‐3, though adopted widely as part of HCAHPS, may not have sufficient ability to discriminate differences in patient outcomes or the quality of care transitions.

More recently, patient‐reported preparedness for discharge was assessed in a prospective cohort in Canada.[16] Lau et al. administered a single‐item measure of readiness at the time of discharge to general medicine patients, and found that lower readiness scores were also not associated with readmission or death at 30 days, when adjusted for the LACE index as we did.